Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Amblyopia Risk Factors in Newborns With Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction

Uploaded by

Syaiful UlumOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Amblyopia Risk Factors in Newborns With Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction

Uploaded by

Syaiful UlumCopyright:

Available Formats

Amblyopia Risk Factors in Newborns With

Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction

Aldo Vagge, MD, PhD; Claudia Tulumello, MD; Marco Pellegrini, MD; Marco Di Maita, MD;

Michele Iester, MD, PhD; Carlo Enrico Traverso, MD

ABSTRACT isometropia might develop later on, all patients with

Purpose: To investigate the presence of amblyopia risk CNLDO should be monitored for amblyopia.

factors in newborns with congenital nasolacrimal duct

obstruction (CNLDO) and age-matched healthy control [J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2020;57(1):39-43.]

subjects.

Methods: This retrospective case-control study involved INTRODUCTION

newborns aged 30 to 60 days with CNLDO and age- Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction

matched healthy control subjects. Amblyopia risk factors (CNLDO) is one of the ophthalmic conditions most

were identified in accordance with the American Asso- commonly encountered by pediatric ophthalmolo-

ciation for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus Vision gists,1,2 occurring in 5% to 15% of full-term new-

Screening Committee recommendations. The prevalence borns.3,4 CNLDO is characterized by unilateral or

of amblyopia risk factors was compared in newborns with bilateral epiphora and/or intermittent mucopurulent

CNLDO and age-matched healthy control subjects, new- discharge that in approximately 90% of patients re-

borns with unilateral and bilateral CNLDO, and the affect- solves spontaneously in the first 12 to 18 months

ed eye and fellow eye of newborns with unilateral CNLDO. of life.5 Although CNLDO is considered a benign

condition, several authors have reported a possible as-

Results: Amblyopia risk factors were found in 18 pa- sociation between CNLDO and amblyopia risk fac-

tients (11.9%) with CNLDO and 19 control subjects tors.6-15 In particular, hyperopia and anisometropia

(8.7%) (P = .314). Eyes with CNLDO showed a signifi- have been observed to be associated with same-sided

cantly lower spherical equivalent compared to control unilateral CNLDO. This condition may predispose

eyes (2.01 ± 1.21 vs 2.79 ± 1.14 diopters, P < .001). No affected children to develop clinical amblyopia.8

difference in amblyopia risk factors was found in eyes However, as far as we know, no previous study has

with unilateral and bilateral CNLDO (11.5% vs 12.1%; P extensively investigated these aspects in newborns.

= .908) or in eyes with unilateral CNLDO and fellow eyes The aim of this study was to compare amblyopia risk

(9.8% vs 12.3%; P = .540). factors in (1) newborns with CNLDO and age-matched

healthy control subjects, (2) newborns with unilateral

Conclusions: CNLDO does not seem to be associated and bilateral CNLDO, and (3) the affected eye and fel-

with amblyopia risk factors in newborns. Because an- low eye of newborns with unilateral CNLDO.

From University Eye Clinic of Genoa, Policlinico San Martino (AV, MD, MI, CET) and the School of Medicine and Pharmacy (CT), Department of

Neuroscience, Rehabilitation, Ophthalmology, Genetics, Maternal and Child Health, University of Genova, Genova, Italy; IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San

Martino, Genova, Italy (AV, MI, CET); and the Ophthalmology Unit, S. Orsola-Malpighi University Hospital, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy (MP).

Submitted: July 11, 2019; Accepted: November 5, 2019

The authors have no financial or proprietary interest in the materials presented herein.

Correspondence: Aldo Vagge, MD, PhD, University Eye Clinic of Genoa, Department of Neuroscience, Rehabilitation, Ophthalmology, Genetics, Maternal

and Child Health, University of Genoa, IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Viale Benedetto XV, 5, 16132 Genova, Italy. E-mail: aldo.vagge@unige.it

doi:10.3928/01913913-20191111-01

Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology & Strabismus • Vol. 57, No. 1, 2020 39

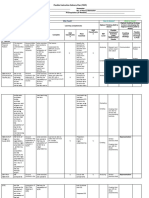

TABLE 1

Characteristics of Patients With CNLDO and Control Subjects

Characteristic CNLDO Group (n = 151) Control Group (n = 218) P

Female gender, n (%) 88 (58) 131 (60) .727

Age (days) 44.4 ± 9.0 45.8 ± 9.6 .310

Birth weight (g) 3,185.1 ± 515.6 3,145.1 ± 484.9 .448

Gestational age (wks) 38.5 ± 2.1 38.7 ± 1.8 .196

CNLDO = congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction

PATIENTS AND METHODS 1 mm in size was considered a nonrefractive ambly-

A chart review of consecutive patients aged 30 opia risk factor.

to 60 days examined at the University Eye Clinic of

Genova, Policlinico San Martino, Department of Statistical Analysis

Neuroscience, Rehabilitation, Ophthalmology, Ge- The SPSS statistical software (SPSS, Inc., Chi-

netics, Maternal and Child Health, Genova, Italy, for cago, IL) was used for data analysis. The chi-square

CNLDO was conducted. The study itself was per- or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categori-

formed in accordance with the tenets of the Declara- cal variables between patients with CNLDO and

tion of Helsinki. Institutional review board approval control subjects, eyes with unilateral and bilateral

was obtained. As is standard practice in our clinic, all CNLDO, and affected and fellow eyes of patients

records reviewed for this study documented a detailed with bilateral CNLDO. Continuous variables were

anterior segment evaluation, a complete cycloplegic expressed as means ± standard deviation. An inde-

refraction, red reflex test, and fundus examination pendent samples t test was used to compare con-

performed 30 minutes following the instillation of tinuous variables between patients with CNLDO

one to two drops of a pediatric “combo drop” of trop- and control subjects and eyes with unilateral and

icamide 1% and phenylephrine 2.5%. The diagnosis bilateral CNLDO. A paired-samples t test was used

of CNLDO was made clinically, based on the pres- to compare continuous variables between affected

ence of epiphora, discharge, and presence of reflux and fellow eyes of patients with bilateral CNLDO.

with digital pressure over the nasolacrimal sac. At the A P value of less than .05 was considered significant.

examiner’s discretion, CNLDO was confirmed with

the dye disappearance test. Only first-encounter re- RESULTS

cords were used. Exclusion criteria for this study were Medical records of 151 consecutive patients with

eyes with any findings that could cause excess tearing, a diagnosis of CNLDO (mean age: 44.4 ± 9.0 days)

such as trichiasis. were compared with those of 218 healthy control

Data were collected regarding patient demo- subjects (mean age: 45.8 ± 9.6 days). Demographic

graphics, including age, gender, birth weight, ges- and clinical characteristics of the study population are

tational age, laterality of CNLDO, and other oph- reported in Table 1. No significant differences were

thalmologic diagnoses. CNLDO was classified into found in age, gender, birth weight, and gestational

unilateral and bilateral. Amblyopia risk factors were age between the two groups (all P > .05). CNLDO

identified in accordance with the American Associa- was unilateral in 122 patients (80.8%) and bilateral

tion for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus in the remaining 29 patients (19.2%).

(AAPOS) Vision Screening Committee recommen- The amblyopia risk factors observed in patients

dations.15 In particular, guidelines for detection of with CNLDO and control subjects are reported

amblyopia risk factors in toddlers were followed. in Table 2. Overall, 18 patients with CNLDO

The recommended target refractive magnitude for (11.9%) and 19 control subjects (8.7%) had ambly-

detection was astigmatism of greater than 2.00 di- opia risk factors, and the difference was not statisti-

opters (D), hyperopia of greater than 4.50 D, myo- cally significant (P = .314). In particular, no signifi-

pia of greater than 3.50 D, and anisometropia of cant differences were found between the two groups

greater than 2.50 D. Any media opacity greater than in astigmatism of greater than 2.00 D (P = .403),

40 Copyright © SLACK Incorporated

TABLE 2

Amblyopia Risk Factors in Patients With CNLDO and Control Subjects

Amblyopia Risk Factor CNLDO Group (n = 151) Control Group (n = 218) P

Astigmatism > 2.00 D, n (%) 3 (2.0) 2 (0.9) .403

Hyperopia > 4.50 D, n (%) 10 (6.6) 15 (6.8) .923

Myopia > 3.50 D, n (%) 1 (0.7) 1 (0.5) 1.000

Anisometropia > 2.50 D, n (%) 3 (2.0) 1 (0.5) .309

Media opacity > 1 mm, n (%) 2 (1.3) 1 (0.5) .570

CNLDO = congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction; D = diopters

TABLE 3

Amblyopia Risk Factors in Eyes With Unilateral and Bilateral CNLDO

Amblyopia Risk Factor Unilateral CNLDO (n = 122) Bilateral CNLDO (n = 58) P

Astigmatism > 2.00 D, n (%) 3 (2.5) 0 (7.4) .552

Hyperopia > 4.50 D, n (%) 8 (6.6) 4 (6.6) .932

Myopia > 3.50 D, n (%) 1 (0.8) 0 (0.8) 1.000

Anisometropia > 2.50 D, n (%) 2 (2.0) 2 (0.5) .595

Media opacity > 1 mm, n (%) 1 (0.8) 1 (0.8) .542

CNLDO = congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction; D = diopters

TABLE 4

Amblyopia Risk Factors in Eyes With Unilateral CNLDO and Fellow Eyes

Amblyopia Risk Factor Unilateral CNLDO (n = 122) Fellow Eyes (n = 122) P

Astigmatism > 2.00 D, n (%) 3 (2.5) 9 (7.4) .136

Hyperopia > 4.50 D, n (%) 8 (6.6) 8 (6.6) 1.000

Myopia > 3.50 D, n (%) 1 (0.8) 1 (0.8) 1.000

Media opacity > 1 mm, n (%) 1 (0.8) 1 (0.8) 1.000

CNLDO = congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction; D = diopters

hyperopia of greater than 4.50 D (P = .923), myo- 2.00 D (P = .552), hyperopia of greater than 4.50 D

pia of greater than 3.50 D (P = 1.000), anisometro- (P = .932), myopia of greater than 3.50 D (P = 1.000),

pia of greater than 2.50 D (P = .309), and media anisometropia of greater than 2.50 D (P = .595), and

opacity of greater than 1 mm (P = .570). Eyes with media opacity of greater than 1 mm (P = .542). No

CNLDO showed a significantly lower spherical significant difference between the two groups was

equivalent compared to control eyes (2.01 ± 1.21 vs found for spherical equivalent (2.04 ± 1.24 vs 1.96 ±

2.79 ± 1.14 D, P < .001). Conversely, no significant 1.06, P = .674) and astigmatism (0.25 ± 0.53 vs 0.18

difference in astigmatism between the two groups ± 0.37, P = .403).

was found (0.23 ± 0.50 vs 0.23 ± 0.47 D, P = .919). The amblyopia risk factors observed in eyes

The amblyopia risk factors observed in eyes with with unilateral CNLDO and fellow eyes are re-

unilateral and bilateral CNLDO are reported in Table ported in Table 4. In the 122 patients with bilateral

3. Overall, 14 eyes (11.5%) of patients with unilateral CNLDO, 12 of the affected eyes (9.8%) had ambly-

CNLDO and 7 eyes (12.1%) of patients with bilateral opia risk factors compared to 15 of the unaffected

CNLDO had amblyopia risk factors (P = .908). In eyes (12.3%) (P = .540). No significant differences

particular, no significant differences were found be- were found between the two eyes in astigmatism of

tween the two groups in astigmatism of greater than greater than 2.00 D (P = .136), hyperopia of greater

Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology & Strabismus • Vol. 57, No. 1, 2020 41

than 4.50 (P = 1.00), myopia of greater than 3.50 D esis, because no relationship between CNLDO and

(P = 1.00), and media opacity of greater than 1 mm anisometropia or hyperopia was found in newborns.

(P = 1.00). No significant difference was found be- Furthermore, eyes with CNLDO were slightly less

tween the two groups for spherical equivalent (2.03 hyperopic compared to control eyes. Interpreting

± 1.24 vs 2.00 ± 1.23, P = .213) and astigmatism such an observation is not certain and requires fur-

(0.25 ± 0.53 vs 0.25 ± 0.53, P = .319). ther investigation to be confirmed.

Another possibility is that watering and mu-

DISCUSSION copurulent discharge in eyes with CNLDO might

The possible relationship between CNLDO cause the development of anisometropia and am-

and amblyopia has been increasingly studied. Sev- blyopia.8,12 The rapid phase of emmetropization

eral studies evaluated the presence of amblyopia risk takes place between 3 and 9 months of age, mainly

factors in patients with CNLDO, reporting a preva- because of an increase in axial length.18 This age is

lence ranging from 9.5% to 35%.6,9-14 In addition, a also associated with peak symptoms of CNLDO.

significantly higher incidence of anisometropia with Therefore, blurring of vision caused by CNLDO

higher hyperopia was observed in eyes with unilater- may interfere with the visual feedback guiding em-

al CNLDO compared to fellow eyes.7,11,14 Similarly, metropization, resulting in increased incidence of

a higher rate of anisometropia was reported in eyes anisometropia. This may explain why newborns

with unilateral compared to bilateral CNLDO.8,13 with CNLDO showed a similar incidence of am-

However, other studies did not identify any signifi- blyopia risk factors as healthy control subjects in

cant difference in the incidence of amblyopia be- this study, whereas other studies including older

tween eyes with CNLDO and control eyes,16 and children reported a higher risk of amblyopia risk

between eyes with unilateral CNLDO and fellow factors associated with CNLDO. The hypothesis is

eyes.17 This heterogeneity may depend on differenc- further supported by the results of Bagheri et al.,7

es in inclusion criteria, sample sizes, and definitions who documented that increasing age in patients

of anisometropia or amblyopia. with CNLDO is associated with a higher prevalence

In the current study, we evaluated the pres- and severity of anisometropia.

ence of amblyopia risk factors in newborns with This study has some limitations that should

CNLDO. Patients with CNLDO and healthy con- be taken into account. First, amblyopia risk fac-

trol subjects showed no significant difference in tors were identified using AAPOS recommenda-

amblyopia risk factors. In addition, no significant tions, which are designed for children older than 12

differences in amblyopia risk factors were observed months. However, no recognized criteria for infants

in eyes with unilateral and bilateral CNLDO or in exist. In addition, due to the cross-sectional design

eyes with unilateral CNLDO and fellow eyes. These of the study, we could not determine the develop-

results are in agreement with those of Ellis et al.,16 ment of anisometropia and/or amblyopia at an older

who found no relationship between CNLDO and age and the possible effect of CNLDO treatment on

amblyopia in a large cohort of 4,792 children. How- visual development. Finally, newborns are known

ever, in contrast to Ellis et al., our study included to display a wide range of refractive errors, and this

only newborns aged 30 to 60 days. To the best of may have reduced the power of the study to detect

our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the significant differences. Further larger studies are re-

association between CNLDO and amblyopia in this quired to confirm our results.

age group. This may explain the discrepancies with CNLDO does not seem to be associated with

other studies, which documented an increased risk amblyopia risk factors in newborns. However, an-

of amblyopia in older children with CNLDO.6-15 isometropia might develop later. Careful follow-up

The mechanism by which patients with and monitoring for amblyopia are recommended

CNLDO might develop anisometropia and am- for all patients with CNLDO.

blyopia is still unknown. One hypothesis is that

a congenital abnormality of the orbit may lead to REFERENCES

1. Guerry D III, Kendig EL Jr. Congenital impatency of the nasolac-

both an impaired canalization of the nasolacrimal rimal duct. Arch Ophthalmol. 1948;39(2):193-204. doi:10.1001/

duct and a reduced axial length of the globe.12 The archopht.1948.00900020198006

results of this study are in contrast with this hypoth- 2. Kamal S, Ali MJ, Gauba V. Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruc-

42 Copyright © SLACK Incorporated

tion. In: Ali MJ, ed. Principles and Practice of Lacrimal Surgery, 2nd dren with persistent congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Graefes

ed. Singapore: Springer; 2018:117-132. doi:10.1007/978-981-10- Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;252(11):1847-1852. doi:10.1007/

5442-6_14 s00417-014-2643-1

3. Sevel D. Development and congenital abnormalities of the nasolacri- 12. Ramkumar VA, Agarkar S, Mukherjee B. Nasolacrimal duct obstruc-

mal apparatus. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1981;18(5):13-19. tion: does it really increase the risk of amblyopia in children? Indian J

4. MacEwen CJ, Young JD. Epiphora during the first year of life. Eye Ophthalmol. 2016;64(7):496-499. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.190101

(Lond). 1991;5(Pt 5):596-600. doi:10.1038/eye.1991.103 13. Siddiqui SN, Mansoor H, Asif M, Wakeel U, Saleem AA. Compari-

5. Vagge A, Ferro Desideri L, Nucci P, et al. Congenital nasolacrimal son of anisometropia and refractive status in children with unilateral

duct obstruction (CNLDO): a review. Diseases. 2018;6(4):E96. and bilateral congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J Pediatr Oph-

doi:10.3390/diseases6040096 thalmol Strabismus. 2016;53(3):168-172. doi:10.3928/01913913-

6. Matta NS, Silbert DI. High prevalence of amblyopia risk factors in 20160405-06

preverbal children with nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J AAPOS. 14. Badakere A, Veeravalli TN, Iram S, Naik MN, Ali MJ. Unilateral

2011;15(4):350-352. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2011.05.007 congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction and amblyopia risk fac-

7. Bagheri A, Safapoor S, Yazdani S, Yaseri M. Refractive state in chil- tors. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:1255-1257. doi:10.2147/OPTH.

dren with unilateral congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J Oph- S171029

thalmic Vis Res. 2012;7(4):310-315. 15. Donahue SP, Arnold RW, Ruben JB; AAPOS Vision Screening

8. Kipp MA, Kipp MA Jr, Struthers W. Anisometropia and amblyopia Committee. Preschool vision screening: what should we be detecting

in nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J AAPOS. 2013;17(3):235-238. and how should we report it? Uniform guidelines for reporting results

doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.11.022 of preschool vision screening studies. J AAPOS. 2003;7(5):314-316.

9. Ozgur OR, Sayman IB, Oral Y, Akmaz B. Prevalence of amblyopia doi:10.1016/S1091-8531(03)00182-4

in children undergoing nasolacrimal duct irrigation and probing. 16. Ellis JD, MacEwen CJ, Young JD. Can congenital nasolacrimal duct

Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013;61(12):698-700. doi:10.4103/0301- obstruction interfere with visual development? A cohort case control

4738.124737 study. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1998;35(2):81-85.

10. Kim JW, Lee H, Chang M, Park M, Lee TS, Baek S. Amblyopia 17. AlHammad F, Al Tamimi E, Yassin S, et al. Unilateral congenital na-

risk factors in infants with congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruc- solacrimal duct obstruction, is it an amblyogenic factor? Middle East

tion. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24(4):1123-1125. doi:10.1097/ Afr J Ophthalmol. 2018;25(3-4):156-160.

SCS.0b013e3182902b3d 18. Flitcroft DI. Emmetropisation and the aetiology of refractive errors.

11. Eshraghi B, Akbari MR, Fard MA, Shahsanaei A, Assari R, Mirmo- Eye (Lond). 2014;28(2):169-179. doi:10.1038/eye.2013.276

hammadsadeghi A. The prevalence of amblyogenic factors in chil-

Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology & Strabismus • Vol. 57, No. 1, 2020 43

You might also like

- Symbolic InteractionismDocument36 pagesSymbolic InteractionismAJ BanaagNo ratings yet

- USMLE Step 3 Lecture Notes 2021-2022: Pediatrics, Obstetrics/Gynecology, Surgery, Epidemiology/Biostatistics, Patient SafetyFrom EverandUSMLE Step 3 Lecture Notes 2021-2022: Pediatrics, Obstetrics/Gynecology, Surgery, Epidemiology/Biostatistics, Patient SafetyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Science Meaning and Evolution 1.347155043Document116 pagesScience Meaning and Evolution 1.347155043mprussoNo ratings yet

- Lethal in Disguise - The Health Consequences of Crowd-Control WeaponsDocument53 pagesLethal in Disguise - The Health Consequences of Crowd-Control Weapons972 Magazine100% (1)

- Test DuncanDocument9 pagesTest DuncanCodrutaNo ratings yet

- Fidp FabmDocument5 pagesFidp FabmEve Intapaya100% (1)

- Personal StatementDocument2 pagesPersonal StatementniangNo ratings yet

- Saleem Et Al, 2017Document5 pagesSaleem Et Al, 2017MUHAMMAD SIDQI FAHMI 1No ratings yet

- Steriod Cataract PDFDocument4 pagesSteriod Cataract PDFLisa IskandarNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma American Journal of OphtalmologyDocument7 pagesGlaucoma American Journal of OphtalmologyListya NormalitaNo ratings yet

- Resiko Jatuh GlaukomaDocument5 pagesResiko Jatuh GlaukomayohanaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Characteristics of Juvenile-Onset Open Angle GlaucomaDocument7 pagesClinical Characteristics of Juvenile-Onset Open Angle GlaucomaRasha Mounir Abdel-Kader El-TanamlyNo ratings yet

- Journal 3Document6 pagesJournal 3riskab123No ratings yet

- Pediatric Optic Neuritis 2016 PDFDocument7 pagesPediatric Optic Neuritis 2016 PDFangelia beanddaNo ratings yet

- Mangione Et Al-2011-Ultrasound in Obstetrics & GynecologyDocument6 pagesMangione Et Al-2011-Ultrasound in Obstetrics & GynecologyAnggita Rizki KusumaNo ratings yet

- Orbital Cellulitis in A Pediatric Population - Experience From A Tertiary CenterDocument3 pagesOrbital Cellulitis in A Pediatric Population - Experience From A Tertiary CenterMuthu V RanNo ratings yet

- Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction - Epidemiology and Risk FactorsDocument6 pagesCongenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction - Epidemiology and Risk FactorsLovely PoppyNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Risk Factors of Thyroid-Associated Ophthalmopathy Among IndiansDocument4 pagesPrevalence and Risk Factors of Thyroid-Associated Ophthalmopathy Among IndiansLastry WardaniNo ratings yet

- Children CataractDocument15 pagesChildren CataractMerlose PlaceNo ratings yet

- Natural History and Outcome of Optic Pathway Gliomas in ChildrenDocument7 pagesNatural History and Outcome of Optic Pathway Gliomas in ChildrenCamilo Benavides BurbanoNo ratings yet

- Relationship of Dissociated Vertical Deviation and The Timing of Initial Surgery For Congenital EsotropiaDocument4 pagesRelationship of Dissociated Vertical Deviation and The Timing of Initial Surgery For Congenital EsotropiaMacarena AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Behcet DiseaseDocument6 pagesBehcet DiseasejbahalkehNo ratings yet

- Genetic Disease Is A Common Cause of Bilateral Childhood Cataract in DenmarkDocument10 pagesGenetic Disease Is A Common Cause of Bilateral Childhood Cataract in DenmarkEvy Alvionita YurnaNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Retinal Breaks in Patients With Symptom of FloatersDocument6 pagesRisk Factors For Retinal Breaks in Patients With Symptom of FloatersaldiansyahraufNo ratings yet

- Blau Int ReviewDocument9 pagesBlau Int ReviewAslıhan Yılmaz ÇebiNo ratings yet

- Khi Tri 2012Document6 pagesKhi Tri 2012Achmad Ageng SeloNo ratings yet

- PIIS0161642020306825Document7 pagesPIIS0161642020306825shofidhiaaaNo ratings yet

- Visual Loss in Uveitis of ChildhoodDocument29 pagesVisual Loss in Uveitis of ChildhoodRizky AgustriaNo ratings yet

- Jogh 12 12003Document10 pagesJogh 12 12003mzpc8rpf78No ratings yet

- Garin 2015Document9 pagesGarin 2015Thya84No ratings yet

- Uveitis in Children and Adolescents: Extended ReportDocument5 pagesUveitis in Children and Adolescents: Extended ReportSelfima PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Javed and Kashif Split PDF 1674305144401Document4 pagesJaved and Kashif Split PDF 1674305144401criticseyeNo ratings yet

- Re Oke Et  Al. Adjustable Suture Technique IDocument1 pageRe Oke Et  Al. Adjustable Suture Technique IYN Eyin VelinNo ratings yet

- An Objective Approach To DED Severity Sullivan Et Al IOVS 12-2010Document6 pagesAn Objective Approach To DED Severity Sullivan Et Al IOVS 12-2010Meyva HannaNo ratings yet

- Progression of Myopia in Teenagers and Adults: A Nationwide Longitudinal Study of A Prevalent CohortDocument6 pagesProgression of Myopia in Teenagers and Adults: A Nationwide Longitudinal Study of A Prevalent Cohortfarras fairuzzakiahNo ratings yet

- Aes 04 9Document6 pagesAes 04 9Ignasius HansNo ratings yet

- Efficacy and Safety of A Soft Contact Lens To Control MyopiaprogressionDocument8 pagesEfficacy and Safety of A Soft Contact Lens To Control MyopiaprogressionAmandaNo ratings yet

- BR J Ophthalmol 2005 BenEzra 444 8Document6 pagesBR J Ophthalmol 2005 BenEzra 444 8Gemilang KhusnurrokhmanNo ratings yet

- Factores de Riesgo EstrabismoDocument11 pagesFactores de Riesgo Estrabismoana maria carrillo nietoNo ratings yet

- Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients With Glaucoma in A Tertiary Eye Facility in GhanaDocument6 pagesDemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients With Glaucoma in A Tertiary Eye Facility in GhanaAldhi Putra PradanaNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Automated Preschool Vision Screening: A 10-Year, Evidence-Based UpdateDocument5 pagesGuidelines For Automated Preschool Vision Screening: A 10-Year, Evidence-Based UpdateSyarifah Thalita NabillaNo ratings yet

- Intracranial Tumors: An Ophthalmic Perspective: DR M Hemanandini, DR P Sumathi, DR P A KochamiDocument3 pagesIntracranial Tumors: An Ophthalmic Perspective: DR M Hemanandini, DR P Sumathi, DR P A Kochamiwolfang2001No ratings yet

- Risk Factor Analysis FOR Long-Term Unfavorable Ocular Outcomes in Children Treated FOR RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITYDocument7 pagesRisk Factor Analysis FOR Long-Term Unfavorable Ocular Outcomes in Children Treated FOR RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITYSalma HamdyNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Visual and Anatomic Results in Treated ROP-JUZ 11-10-22Document24 pagesLong-Term Visual and Anatomic Results in Treated ROP-JUZ 11-10-22areaNo ratings yet

- TSWJ2012 109624 PDFDocument6 pagesTSWJ2012 109624 PDFErika CordeiroNo ratings yet

- Congenital Glaucoma Epidemiological Clinical and Therapeutic Aspects About 414 EyesDocument5 pagesCongenital Glaucoma Epidemiological Clinical and Therapeutic Aspects About 414 Eyessiti rumaisaNo ratings yet

- Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction (CNLDO) - A ReviewDocument11 pagesCongenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction (CNLDO) - A ReviewLovely PoppyNo ratings yet

- Characteristics and Outcome of Patients With Ganglioneuroblastoma, Nodular Subtype: A Report From The INRG ProjectDocument7 pagesCharacteristics and Outcome of Patients With Ganglioneuroblastoma, Nodular Subtype: A Report From The INRG ProjectWahyudhy SajaNo ratings yet

- Neutrophil-To-Lymphocyte Ratio in Pediatric Acute AppendicitisDocument10 pagesNeutrophil-To-Lymphocyte Ratio in Pediatric Acute AppendicitisAnonymous S0MyRHNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Glaukoma 3Document9 pagesJurnal Glaukoma 3Ahmad Fathul AdzmiNo ratings yet

- Role of Flicker Perimetry in Predicting Onset of Late-Stage Age-Related Macular DegenerationDocument10 pagesRole of Flicker Perimetry in Predicting Onset of Late-Stage Age-Related Macular DegenerationHarold Estiven MarinNo ratings yet

- Pterygium in Indonesia: Prevalence, Severity and Risk FactorsDocument6 pagesPterygium in Indonesia: Prevalence, Severity and Risk FactorsAndi Prajanita AlisyahbanaNo ratings yet

- Pan Et Al-2012-Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics PDFDocument14 pagesPan Et Al-2012-Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics PDFputriripalNo ratings yet

- Perilongo 1997Document7 pagesPerilongo 1997Gustav RSRNo ratings yet

- PARS Reader's Digest - May 2013Document10 pagesPARS Reader's Digest - May 2013info8673No ratings yet

- 38 145 1 PBDocument6 pages38 145 1 PBChaya RaghuNo ratings yet

- AygunDocument5 pagesAygunotheasNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Geographical Variations: Section 1 Glaucoma in The WorldDocument10 pagesPrevalence and Geographical Variations: Section 1 Glaucoma in The WorldGuessNo ratings yet

- Acute Isolated Sphenoid Sinusitis in Children - 2021 - International Journal ofDocument8 pagesAcute Isolated Sphenoid Sinusitis in Children - 2021 - International Journal ofHung Son TaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of The Reliability of 17 Celiac DiseaseDocument9 pagesComparison of The Reliability of 17 Celiac Diseasesiddhi divekarNo ratings yet

- Study of Vision Screening in School Children Between 5 and 15 YearsDocument16 pagesStudy of Vision Screening in School Children Between 5 and 15 YearsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Blindness in Patients With Uveitis: Original ResearchDocument4 pagesPrevalence of Blindness in Patients With Uveitis: Original ResearchMuhammad RaflirNo ratings yet

- 10 1111@aos 13964 PDFDocument9 pages10 1111@aos 13964 PDFPutra TridiyogaNo ratings yet

- Empiema en NiñosDocument5 pagesEmpiema en NiñosMarbel CreusNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1091853116304438 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S1091853116304438 MainMarcella PolittonNo ratings yet

- Endoscopy in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel DiseaseFrom EverandEndoscopy in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel DiseaseLuigi Dall'OglioNo ratings yet

- A Discourse Analysis On PrefacesDocument13 pagesA Discourse Analysis On PrefacesvietanhpsNo ratings yet

- Law Mantra: India's Citizens' Charter: Tracing Its Success and FailureDocument6 pagesLaw Mantra: India's Citizens' Charter: Tracing Its Success and FailureLAW MANTRA100% (1)

- Rubric For The Search of Outstanding.Document10 pagesRubric For The Search of Outstanding.Manuelito MontoyaNo ratings yet

- Oil Seed Report FinalDocument77 pagesOil Seed Report FinalSelamNo ratings yet

- Se Lab CD ItDocument11 pagesSe Lab CD ItAnanthoja ManiKantaNo ratings yet

- High School Social Studies ImpDocument34 pagesHigh School Social Studies Impmharielle CaztherNo ratings yet

- Process Capability (CP, CPK) and Process Performance (PP, PPK) - What Is The Difference?Document7 pagesProcess Capability (CP, CPK) and Process Performance (PP, PPK) - What Is The Difference?Thirukumaran RNo ratings yet

- Cybercrime Techniques in Online Banking: September 2022Document19 pagesCybercrime Techniques in Online Banking: September 2022Jonas MeierNo ratings yet

- Reviewer For Clinical PsychDocument21 pagesReviewer For Clinical PsychValerie FallerNo ratings yet

- Week 7 Processing and Displaying Data SBoufousDocument50 pagesWeek 7 Processing and Displaying Data SBoufousKelvin YuenNo ratings yet

- RPS Quantitative ResearchDocument3 pagesRPS Quantitative ResearchrahmaNo ratings yet

- International Financial MGMT U1Document77 pagesInternational Financial MGMT U1Kai KeatNo ratings yet

- Performance Based Design of Structures (PBDS-2019) : ParticipationDocument2 pagesPerformance Based Design of Structures (PBDS-2019) : ParticipationSagar GowdaNo ratings yet

- ResearchproposalDocument7 pagesResearchproposalAidie MendozaNo ratings yet

- Measures of Central Tendency: (Mean, Mode and Median - Exercises)Document61 pagesMeasures of Central Tendency: (Mean, Mode and Median - Exercises)M Pavan KumarNo ratings yet

- English Language Preschool: Kementerian Pendidikan MalaysiaDocument33 pagesEnglish Language Preschool: Kementerian Pendidikan MalaysiatasbihkacaNo ratings yet

- Stats Chapter 8 Hypoth TestingDocument24 pagesStats Chapter 8 Hypoth TestingMadison HartfieldNo ratings yet

- Yu Ye PDFDocument40 pagesYu Ye PDFPrajitha Jinachandran T KNo ratings yet

- Patient Health Education Seminar Powerpoint TemplateDocument11 pagesPatient Health Education Seminar Powerpoint TemplateHarshal SabaneNo ratings yet

- Job Evaluation and Job Analysis Are Two Approaches That Are Often Used To Identify Relevant Criteria For Recruitment and Selection in An OrganizationDocument17 pagesJob Evaluation and Job Analysis Are Two Approaches That Are Often Used To Identify Relevant Criteria For Recruitment and Selection in An Organizationsilas gundaNo ratings yet

- University of Zimbabwe: G E N E T I C SDocument49 pagesUniversity of Zimbabwe: G E N E T I C SKhufaziera KharuddinNo ratings yet

- PHA100 Portable Hydrocarbon Analyzer1Document2 pagesPHA100 Portable Hydrocarbon Analyzer1HansSuarezCuevaNo ratings yet

- Research AnalystDocument3 pagesResearch AnalystSakile Toni YungaiNo ratings yet