Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Saleem Et Al, 2017

Uploaded by

MUHAMMAD SIDQI FAHMI 10 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

12 views5 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

12 views5 pagesSaleem Et Al, 2017

Uploaded by

MUHAMMAD SIDQI FAHMI 1Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

Original Article

Taiwan J Ophthalmol 2017;8:31‑35

Access this article online

Quick Response Code:

Anisometropia and refractive status

in children with unilateral congenital

nasolacrimal duct obstruction

Adnan Aslam Saleem, Sorath Noorani Siddiqui, Umair Wakeel, Muhammad Asif

Website:

www.e‑tjo.org

Abstract:

DOI:

10.4103/tjo.tjo_77_17 OBJECTIVE: The objective of the study was to evaluate the refractive status and thereby assess

anisometropia in children with unilateral congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction (CNLDO).

STUDY DESIGN: This study design was a descriptive cross‑sectional study.

PLACE AND DURATION: this study was conducted at the Department of Pediatric Ophthalmology

and Strabismology, Al‑Shifa Trust Eye Hospital, Rawalpindi; from August 2013 to July 2014.

METHODOLOGY: This study assessed consecutive children with unilateral CNLDO. Cycloplegic

refraction on all children with CNLDO was performed followed by appropriate intervention. Refractive

errors of the affected and normal eyes were compared.

RESULTS: One hundred and twenty‑four children with a mean age of 29.69 ± 21.12 months (range,

2 months to 8 years) were studied. Based on spherical equivalent (SE), hypermetropia was more

common in the affected eyes (P < 0.001). Anisometropia of >1.5 diopters (D) was present in

n = 17 (13.7%). Interocular difference was significant for spherical error and SE (P < 0.001) but not

cylindrical errors.

CONCLUSION: Unilateral CNLDO is associated with statistically significant anisometropia, especially

anisohypermetropia which has amblyogenic potential. It is vital to perform cycloplegic refraction

routinely and counsel parents regarding prognosis and regular follow‑ups.

Keywords:

Anisometropia, congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction, refractive, status

Introduction becomes persistent and/or once the child is

older than 1 year of age. Our previous study

C ongenital nasolacrimal duct

obstructions (CNLDO) are one of

the most common cases seen in pediatric

on outcome of primary intubation in CNLDO

showed success in 92% children <2 years of

age and 90% in children between 2 and

ophthalmology clinics. CNLDO occurs 3 years of age.[3]

in 5%–15% of full‑term newborns.[1] It is

characterized by epiphora and intermittent NLDO has usually been considered a

discharge. It is usually unilateral or benign condition that does not influence

asymmetric and is mainly due to a persistent visual development. It is indefinite what

Pediatric Ophthalmology membrane at the level of Hasner valve. part, if any; persistent tearing has on

and Strabismus, Al‑Shifa Approximately, 90% experience spontaneous visual development, refractive status,

Trust Eye Hospital, resolution before the age of 1 year. It becomes and amblyopia. A number of authors

Rawalpindi, Pakistan

symptomatic in merely 5%–6% of infants.[2] have recently described a relationship

Address for Intervention is usually done when CNLDO between CNLDO and the development

correspondence: of amblyopia and strabismus secondary

Dr. Adnan Aslam Saleem, to anisometropia. [4‑7] The major visual

Al‑Shifa Trust This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed

concern in CNLDO is the presence of

Eye Hospital, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-

Rawalpindi, Pakistan. NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows

E‑mail: doctoradnansaleem others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non- How to cite this article: Saleem AA, Siddiqui SN,

@gmail.com commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the Wakeel U, Asif M. Anisometropia and refractive status

new creations are licensed under the identical terms. in children with unilateral congenital nasolacrimal duct

Submission: 12-03-2017 obstruction. Taiwan J Ophthalmol 2018;8:31-5.

Accepted: 07‑08‑2017 For reprints contact: reprints@medknow.com

© 2018 Taiwan J Ophthalmol | Published by Wolters Kluwer ‑ Medknow 31

significant anisometropia during vital period of visual Results

development in these infants. The objective of this

current study was to describe the type, frequency of One hundred and twenty‑four patients (n = 124) were

refractive error, and the severity of anisometropia in a included in this study with a mean age (in months) and

successive series of children diagnosed with unilateral standard deviation of 29.69 ± 21.12. The minimum age

CNLDO. was 2 months and maximum 96 months. The number

of male patients was 76 (61.3%) and female patients

Methodology were 48 (38.7%). The left eye was affected in 72 (58.1%)

patients and right eye was affected in 52 (41.93%).

The study includes children with unilateral CNLDO who The highest hypermetropic refractive error was +6 D

presented to our institute from August 1, 2013 to July 31, and highest myopic error was −5.50 D. Discharge was

2014. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics present in 19 cases (15.3%) whereas 105 (84.7%)

Review Board of Pakistan Institute of Ophthalmology. patients presented with epiphora. The current study

A written informed consent was attained from all shows that the highest number of patients (n = 75)

parents/guardians before enrollment. with unilateral CNLDO presented in the first 2 years

of life (0–24 months). Three children were under

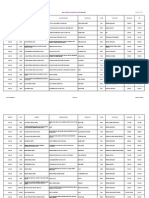

Inclusion criteria were epiphora and/or discharge 6 months of age (2, 4, and 6 months). Figure 1 shows

from birth which did not respond to nasolacrimal duct the distribution of patients according to different age

massage, till 1 year and up to 6 months of age when there groups.

was mucopurulent discharge. Children with unilateral

involvement from the start were only studied. If the The largest interocular difference in sphere was

child had a previously confirmed diagnosis of CNLDO 3 D, cylinder was 1 D, and SE was 2.5 D. Based on

since birth; we included them in our study, no matter at SE, hypermetropia was more common in affected

what age they presented. Exclusion criteria consisted of eyes whereas myopia was more prevailing in the

any ocular deformity which could influence refractive fellow eyes [Table 1]. Anisometropia (spherical or

status for instance ptosis, strabismus, media opacities, cylindrical >1.5 D) was present in 17 cases (13.7%).

glaucoma, or keratopathy. Syndromic children with

CNLDO and craniosynostosis were excluded from the A Wilcoxon signed‑rank test revealed a statistically

study. Children who had a history of surgery were also significant difference between spheres of affected

excluded from the study. eyes (median = 0.75, IQR = 1.50) and fellow

eyes (median = 0.5, IQR = 1), z = −4.643, P < 0.001.

Cycloplegic refraction was done with 1% cyclopentolate There was also a statistically significant difference

drops, instilled in the conjunctival sac three times, between SEs of affected eyes (median = 0.63, IQR = 1.25)

spaced out at 5, 15, and 30 min on the day of and fellow eyes (median = 0.5, IQR = 1), z = −3.831,

presentation; refraction was performed 30 min after P < 0.001; and axis of affected eyes (median = 0,

last drop by means of streak retinoscopy. Children who IQR = 0) and fellow eyes (median = 0, IQR = 75),

did not achieve cycloplegia with 1% cyclopentolate z = −0.760, P = 0.448. However, no statistically significant

were excluded from the study. No cycloplegic difference was observed between the cylinder of affected

refraction was done under EUA. Uncooperative eyes (median = 0, IQR = 0) and fellow eyes (median = 0,

children were sedated with chloral hydrate syrup IQR = 0), z = −1.892, P > 0.05 [Table 2].

after pediatric consultation. In most cases owing to

the epiphora and discharge, it was impossible to mask

70%

the examiner/optometrist. Complete anterior and

60.50%

posterior segment examinations were done by senior 60%

pediatric ophthalmologist.

50%

All the data were analyzed using SPSS (Statistical 40%

Package for the Social Science, IBM, USA) version 17.

30%

Descriptive statistics are presented as percentages, 23.40%

frequencies, median, and interquartile range (IQR). 20%

13.70%

The continuous data were tested for normality using 10%

Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. As the continuous data 2.40%

were nonparametric, the Wilcoxon signed‑rank test was 0%

0-2 Years 3-4 Years 5-6 Years 7-8 Years

employed to compare the sphere, cylinder, axis, and

spherical equivalent (SE) of the affected and fellow eyes. Figure 1: Age distribution of children with unilateral congenital nasolacrimal duct

P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. obstruction with corresponding frequencies

32 Taiwan J Ophthalmol - Volume 8, Issue 1, January-March 2018

Discussion The prevalence is even higher in medically underserved

populations with reported rate as high as 22.7%.[14]

CNLDO has been at the hub of recent debate on its

proposed relationship with anisometropia, strabismus, Anisometropia disturbs binocularity causing reduced

and amblyopia. No cause‑effect relationship linking stereoacuity; hence, its management is more complex

CNLDO and anisometropia has been studied and compared to strabismal and deprivational amblyopia.

the precise method by which CNLDO might cause Studies demonstrate that the most important factors in

refractive error, anisometropia, and amblyopia is treatment results are age and depth of amblyopia that

indistinct. The proper focusing of images on the retina are directly related to the degree of anisometropia.[15]

early in life is vital for emmetropization. CNLDO rarely Therefore, as the child gets older management becomes

if ever results in complete visual obstruction. Besides, more complex and time consuming, particularly

early unilateral visual deprivation has been linked in hypermetropic anisometropes in whom a less

with myopia not hypermetropia. [8] It is postulated encouraging treatment results are seen, in contrast to

that accumulation of discharge, excessive tears, and myopes. Based on our results, we believe that it is vital

antibiotic ointments may result in the deformation to check refractive status of children with CNLDO to

of retinal images. This image disparity may lead to a assess visually significant anisometropia at an early age

lack of appropriate emmetropization, and as a result, to prevent these children from amblyopia and visual

the repeated finding of anisometropia in the affected morbidity.

eye. It is also proposed that this anisometropia is

refractory. However, recent studies reveal that this is First Chalmers and later Ellis questioned the relationship

not necessarily true.[9] between CNLDO and visual maturation. Chalmers

found anisometropia in 3.8%, in eyes with CNLDO; all

The significance of anisometropia as a source of their participants were hypermetropic in the affected

amblyopia is well documented. Donahue suggests that eye.[16] Ellis found no appreciable increased incidence

1 D of anisometropia can be considered as clinically of amblyopia (1.6%) in a large series of 2249 patients

significant anisometropia.[10] The American Association with nasolacrimal duct obstruction (NLDO) compared

for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus guidelines with controls. They also found no correlation between

state that anisometropia (spherical or cylindrical) refractive error and NLDO, including no significant

>1.5 D is an amblyopic risk factor.[11] Nevertheless, due

increase in the incidence of anisometropia.[17]

to individual physiologic variability’s, amblyopia can

even be seen with milder degree of anisometropia. The Our prevalence of anisometropia (>1.5 D) in NLDO

prevalence of anisometropia in the general pediatric patients of 13.7% is approximately thrice that of the

population ranges from 2.3% to 3.4%, based on literature general population. It is also higher than reported

review.[12] Amblyopia has been reported to occur in studies on this subject matter.[4‑6,16‑19] Similarly, a study

approximately 1.6%–3.6% of the normal population.[13]

of around 1200 CNLDO patients found twice the rate of

anisometropia in the unilateral CNLDO patients (7.6%)

Table 1: Type of refractive error, frequencies, and

comparison with fellow eye

compared with bilateral NLDO patients (3.6%) that

Affected eyes, Fellow eyes,

the rate of anisometropia and amblyopia are greater in

n (%) n (%) NLDO patients.[4]

Emmetropia 20 (16.1) 22 (17.7)

Myopia 1 (0.8) 6 (4.8) Matta and Silbert reviewed 375 patients with CNLDO

Hypermetropia 80 (64.5) 61 (49.2) and reported that 22% of the children with CNLDO had

Simple myopic astigmatism 1 (0.8) 1 (0.8) amblyopia risk factors.[5] Piotrowski et al. described a

Compound myopic astigmatism 4 (3.2) 2 (1.6) high prevalence (9.8%) of anisometropia with or without

Simple hyperopic astigmatism 4 (3.2) 8 (6.5) amblyopia in an 8‑year consecutive case series which

Compound hyperopic astigmatism 5 (4.0) 15 (12.1) included 305 children with CNLDO.[6] Furthermore,

Mixed astigmatism 9 (7.2) 9 (7.2) Eshraghi et al. studied 433 cases with CNLDO that

Total 124 124 underwent probing. They reported that 5.5% had

Table 2: Median interquartile ranges of affected and fellow eyes

n Median of affected eyes (IQR) Median of fellow eyes (IQR) Z P

Sphere (D) 124 0.75 (1.5) 0.5 (1.00) −4.64 <0.001

Cylinder (D) 0.00 (0.00) 0.00 (0.00) −1.89 0.059

Axis (°) 0.00 (0.00) 0.00 (75) −0.76 0.448

Spherical equivalent (D) 0.63 (1.25) 0.5 (1.00) −3.83 <0.001

IQR=Interquartile range

Taiwan J Ophthalmol - Volume 8, Issue 1, January-March 2018 33

anisometropia and 9.46% had amblyopia risk factors. facts may support the benefit of early intervention in

They also found more anisometropia in failed probing CNLDO. However, further studies with larger sample

cases and theorized that structural abnormality may have size longer follow‑up time are required to establish

a role in anisometropia.[18] this effect. A cohort, visual status documentation and

longer follow‑up are required to answer the relationship

Bagheri et al. evaluated refractive state in children with between CNLDO and amblyopia. The cross‑sectional

unilateral CNLDO; they reported that, in children aged nature of this study limits us to draw any conclusions

4 years and older, the interocular difference between on the relationship between CNLDO and amblyopia.

spherical error and SE was considerable as compared

to children younger than 4 years.[19] Contrary to this, Conclusion

our study found no significant association between

the age (in months) of the patients and the interocular Unilateral CNLDO is a risk factor for anisometropia,

difference in sphere, cylinder, and SE of affected and particularly hypermetropic anisometropia with

nonaffected eyes. We also observed that difference amblyogenic potential. Keeping in view that CNLDO is a

between the affected and fellow eyes was significant common presentation in pediatric ophthalmology clinics,

in terms of spherical refractive error and SE and that we recommend that all children with CNLDO should

hypermetropia was more common in the eye with be regularly followed, even after the obstruction has

CNLDO. These findings suggest that when unilateral anatomically and functionally resolved. These children

CNLDO becomes chronic, the likelihood and severity should undergo cycloplegic refraction on each visit and

of hypermetropia increases, which as detailed, is a risk should be monitored for the development of amblyopia

factor for amblyopia. This finding is clinically significant, and other ocular abnormalities.

as management and prognosis of amblyopia becomes

intricate in older children. Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Recently, Pyi Son studied 244 cases and found that early

and spontaneous resolution of CNLDO is more likely to Conflicts of interest

have a higher (not lower) rate of anisometropia compared The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests

to spontaneous or surgical resolution.[20] They proposed of this paper.

that the eye with CNLDO proceeds to emmetropization

differently than the unaffected eye. Early resolution References

can hinder the process of emmetropization in the

affected eye, making it lag behind the normal eye in 1. American Academy of Ophthalmology Basic and Clinical Science

achieving emmetropization. These findings negate Course Subcommittee. Basic and Clinical Science Course. Sec. 6.

the fact that anisometropia in CNLDO is transient and Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus; 2015‑2016.

refractory. Further studies need to be done to determine 2. Schnall BM. Pediatric nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Curr Opin

Ophthalmol 2013;24:421‑4.

the timing of resolution of CNLDO and its effect on

3. Memon MN, Siddiqui SN, Arshad M, Altaf S. Nasolacrimal duct

the development of anisometropic amblyopia. In our obstruction in children: Outcome of primary intubation. J Pak

study, we did not determine whether anisometropia Med Assoc 2012;62:1329‑32.

persisted or not after surgical intervention or in later life. 4. Kipp MA, Kipp MA Jr., Struthers W. Anisometropia and amblyopia

Nonetheless, Simon reported that even after CNLDO in nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J AAPOS 2013;17:235‑8.

has improved, anisometropic hypermetropia is a regular 5. Matta NS, Silbert DI. High prevalence of amblyopia risk factors in

preverbal children with nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J AAPOS

finding in patients with a history of unilateral CNLDO.[7] 2011;15:350‑2.

Our results also show a high rate of anisometropia which 6. Piotrowski JT, Diehl NN, Mohney BG. Neonatal dacryostenosis as

concomitantly has amblyogenic effect. a risk factor for anisometropia. Arch Ophthalmol 2010;128:1166‑9.

7. Simon JW, Ngo Y, Ahn E, Khachikian S. Anisometropic amblyopia

Studies mention that emmetropia is achievable in and nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J Pediatr Ophthalmol

anisometropes with appropriate management. [21] Strabismus 2009;46:182‑3.

8. Weiss AH. Unilateral high myopia: Optical components,

However, the precise cause why studies find high associated factors, and visual outcomes. Br J Ophthalmol

prevalence of anisometropia in subjects even after 2003;87:1025‑31.

CNLDO has resolved is still contentious. Nevertheless, 9. Ozgur OR, Sayman IB, Oral Y, Akmaz B. Prevalence of amblyopia

the results endorse the fact that patients of CNLDO in children undergoing nasolacrimal duct irrigation and probing.

should be regularly reviewed for refractory status. Indian J Ophthalmol 2013;61:698‑700.

10. Donahue SP. Relationship between anisometropia, patient age and

Furthermore, as some studies state that, in older

the development of amblyopia. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;142:132‑40.

participants, the interocular difference becomes more 11. Donahue SP, Arnold RW, Ruben JB, AAPOS Vision Screening

significant compared to younger children, this places Committee. Preschool vision screening: What should we be

them at high risk for developing amblyopia.[6,18‑20] These detecting and how should we report it? Uniform guidelines for

34 Taiwan J Ophthalmol - Volume 8, Issue 1, January-March 2018

reporting results of preschool vision screening studies. J AAPOS Orthopt J 1996;53:29‑30.

2003;7:314‑6. 17. Ellis JD, MacEwen CJ, Young JD. Can congenital nasolacrimal

12. Borchert M, Tarczy‑Hornoch K, Cotter SA, Liu N, Azen SP, duct obstruction interfere with visual development? A cohort

Varma R, et al. Anisometropia in hispanic and African American case control study. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1998;35:81‑5.

infants and young children the Multi‑Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease 18. Eshraghi B, Akbari MR, Fard MA, Shahsanaei A, Assari R,

Study. Ophthalmology 2010;117:148‑53.e1. Mirmohammadsadeghi A. The prevalence of amblyogenic

13. Simons K. Amblyopia characterization, treatment, and factors in children with persistent congenital nasolacrimal duct

prophylaxis. Surv Ophthalmol 2005;50:123‑66. obstruction. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2014;252:1847‑52.

14. Soori H, Ali JM, Nasrin R. Prevalence and cause of low vision 19. Bagheri A, Safapoor S, Yazdani S, Yaseri M. Refractive state in

and blindness in Tehran Province, Iran. J Pak Med Assoc children with unilateral congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction.

2011;61:544‑9. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2012;7:310‑5.

15. Caputo R, Frosini R, De Libero C, Campa L, Magro EF, Secci J, et al. 20. Pyi Son MK, Hodge DO, Mohney BG. Timing of congenital

Factors influencing severity of and recovery from anisometropic dacryostenosis resolution and the development of anisometropia.

amblyopia. Strabismus 2007;15:209‑14. Br J Ophthalmol 2014;98:1112‑5.

16. Chalmers RJ, Griffiths PG. Is congenital nasolacrimal duct 21. Atilla H, Kaya E, Erkam N. Emmetropization in anisometropic

obstruction a risk factor for the development of amblyopia? Br amblyopia. Strabismus 2009;17:16‑9.

Taiwan J Ophthalmol - Volume 8, Issue 1, January-March 2018 35

You might also like

- Lifeguarding ManualDocument405 pagesLifeguarding Manualmegan100% (3)

- Cranial Nerve AssessmentDocument17 pagesCranial Nerve AssessmentMahendran Jayaraman100% (1)

- Marieb Ch11aDocument23 pagesMarieb Ch11aapi-229554503No ratings yet

- Nurse CertificationsDocument1 pageNurse CertificationsmirandasheaNo ratings yet

- AXA Insurnace NetworkDocument241 pagesAXA Insurnace NetworkMuhammad SiddiuqiNo ratings yet

- Death CertificateDocument3 pagesDeath CertificateAllen Peter WeixlerNo ratings yet

- EMQs For Dentistry - 3rd Ed. 2016 PDFDocument455 pagesEMQs For Dentistry - 3rd Ed. 2016 PDFWasiAliMemon100% (1)

- Clinical Management Review 2023-2024: Volume 2: USMLE Step 3 and COMLEX-USA Level 3From EverandClinical Management Review 2023-2024: Volume 2: USMLE Step 3 and COMLEX-USA Level 3No ratings yet

- Physio Uhs Solved Past Papers 2nd YearDocument126 pagesPhysio Uhs Solved Past Papers 2nd YearMudassar Roomi100% (3)

- CH 5.1 - Vaccine Saftey ForwardDocument24 pagesCH 5.1 - Vaccine Saftey Forwardtolerancelost607100% (4)

- SRNA Orientation ChecklistDocument40 pagesSRNA Orientation Checklistihtisham1No ratings yet

- HaraShiatsu Self HealingDocument3 pagesHaraShiatsu Self HealingAWEDIOHEADNo ratings yet

- Atresia BilierDocument11 pagesAtresia BilierLaura ChandraNo ratings yet

- Results of Nasolacrimal Duct Probing in Children Between 9-48 MonthsDocument1 pageResults of Nasolacrimal Duct Probing in Children Between 9-48 MonthsSuraz AleyNo ratings yet

- Zedan, 2017Document5 pagesZedan, 2017Muhammad Sidqi FahmiNo ratings yet

- Amblyopia Risk Factors in Newborns With Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct ObstructionDocument5 pagesAmblyopia Risk Factors in Newborns With Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct ObstructionSyaiful UlumNo ratings yet

- Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction (CNLDO) - A ReviewDocument11 pagesCongenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction (CNLDO) - A ReviewLovely PoppyNo ratings yet

- Jurnal MataDocument8 pagesJurnal MatamarinarizkiNo ratings yet

- Results of Surgery For Congenital Esotropia: Original ResearchDocument6 pagesResults of Surgery For Congenital Esotropia: Original ResearchkarenafiafiNo ratings yet

- Resiko Jatuh GlaukomaDocument5 pagesResiko Jatuh GlaukomayohanaNo ratings yet

- Ocular Manifestations in Down's SyndromeDocument4 pagesOcular Manifestations in Down's SyndromeSayoki ghosgNo ratings yet

- Effect of Cycloplegia On The Refractive Status of Children The Shandong Children Eye StudyDocument10 pagesEffect of Cycloplegia On The Refractive Status of Children The Shandong Children Eye StudyRuby KhanNo ratings yet

- Rajavi 2015Document7 pagesRajavi 2015Sherry CkyNo ratings yet

- Demography and Etiology of Congenital Cataract in A Tertiary Eye Centre of Kathmandu, NepalDocument8 pagesDemography and Etiology of Congenital Cataract in A Tertiary Eye Centre of Kathmandu, NepalasfwegereNo ratings yet

- Javed and Kashif Split PDF 1674305144401Document4 pagesJaved and Kashif Split PDF 1674305144401criticseyeNo ratings yet

- Eye Infections PDFDocument10 pagesEye Infections PDFDara Agusti MaulidyaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Characteristics of Juvenile-Onset Open Angle GlaucomaDocument7 pagesClinical Characteristics of Juvenile-Onset Open Angle GlaucomaRasha Mounir Abdel-Kader El-TanamlyNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Optic Neuritis 2016 PDFDocument7 pagesPediatric Optic Neuritis 2016 PDFangelia beanddaNo ratings yet

- Associations of Anisometropia With Unilateral Amblyopia, Interocular Acuity Difference, and Stereoacuity in PreschoolersDocument9 pagesAssociations of Anisometropia With Unilateral Amblyopia, Interocular Acuity Difference, and Stereoacuity in PreschoolersCalvin NugrahaNo ratings yet

- Congenital Glaucoma Epidemiological Clinical and Therapeutic Aspects About 414 EyesDocument5 pagesCongenital Glaucoma Epidemiological Clinical and Therapeutic Aspects About 414 Eyessiti rumaisaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Dr. Graecia Bungaran BruDocument15 pagesJurnal Dr. Graecia Bungaran BrudinimaslomanNo ratings yet

- Steriod Cataract PDFDocument4 pagesSteriod Cataract PDFLisa IskandarNo ratings yet

- Validation of Guidelines For Undercorrection of Intraocular Lens Power in ChildrenDocument6 pagesValidation of Guidelines For Undercorrection of Intraocular Lens Power in ChildrenDesta FransiscaNo ratings yet

- Incidence of Amblyopia in The Menoufia University Outpatient ClinicDocument7 pagesIncidence of Amblyopia in The Menoufia University Outpatient ClinicfatmadianaNo ratings yet

- Intraocular Lenses and Clinical Treatment in Paediatric CataractDocument5 pagesIntraocular Lenses and Clinical Treatment in Paediatric CataractLinna LetoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1091853116304438 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S1091853116304438 MainMarcella PolittonNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Visual Outcome Following Surgical Treatment of Cataracts in ChildrenDocument9 pagesFactors Affecting Visual Outcome Following Surgical Treatment of Cataracts in ChildrenriyanNo ratings yet

- Journal 3Document6 pagesJournal 3riskab123No ratings yet

- Retinopathy of Prematurity Like Retinopathy in Full-Term InfantsDocument9 pagesRetinopathy of Prematurity Like Retinopathy in Full-Term InfantsReza SatriaNo ratings yet

- Paediatric Cataracts Clinical and Experimental Advances in Congenital andDocument17 pagesPaediatric Cataracts Clinical and Experimental Advances in Congenital andCahyo GuntoroNo ratings yet

- Study of Vision Screening in School Children Between 5 and 15 YearsDocument16 pagesStudy of Vision Screening in School Children Between 5 and 15 YearsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmologic Manifestations and Retinal Findings in Children With Down SyndromeDocument6 pagesOphthalmologic Manifestations and Retinal Findings in Children With Down SyndromeMuhammad Imam NoorNo ratings yet

- Original Article: Sijuwola OO, Adeyemo AA, and Adeosun AADocument3 pagesOriginal Article: Sijuwola OO, Adeyemo AA, and Adeosun AAmawarmelatiNo ratings yet

- Atropine Treatment 1Document7 pagesAtropine Treatment 1Chris ChowNo ratings yet

- 11 4 Hughes FitzGeraldDocument3 pages11 4 Hughes FitzGeraldellafinarsihNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Blindness in Patients With Uveitis: Original ResearchDocument4 pagesPrevalence of Blindness in Patients With Uveitis: Original ResearchMuhammad RaflirNo ratings yet

- 10 1111@aos 14081Document6 pages10 1111@aos 14081Evy Alvionita YurnaNo ratings yet

- Change in Vision Disorders Among Hong Kong Preschoolers in 10 YearsDocument6 pagesChange in Vision Disorders Among Hong Kong Preschoolers in 10 YearsMacarena AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Association of Asthenopia and Convergence Insufficiency in Children With Refractive Error-A Hospital Based StudyDocument6 pagesAssociation of Asthenopia and Convergence Insufficiency in Children With Refractive Error-A Hospital Based StudySilvia RNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Glaucoma PDFDocument8 pagesPediatric Glaucoma PDFDr.Nalini PavuluriNo ratings yet

- Ebri 2007Document7 pagesEbri 2007Phillip NyambaloNo ratings yet

- Nicoline MataDocument5 pagesNicoline MataLissaberti AmaliahNo ratings yet

- MR 180 EditedDocument6 pagesMR 180 EditedfatmadianaNo ratings yet

- Relationship of Dissociated Vertical Deviation and The Timing of Initial Surgery For Congenital EsotropiaDocument4 pagesRelationship of Dissociated Vertical Deviation and The Timing of Initial Surgery For Congenital EsotropiaMacarena AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma After Congenital Cataract SurgeryDocument6 pagesGlaucoma After Congenital Cataract SurgerySamawi RamudNo ratings yet

- Efficacy and Safety of A Soft Contact Lens To Control MyopiaprogressionDocument8 pagesEfficacy and Safety of A Soft Contact Lens To Control MyopiaprogressionAmandaNo ratings yet

- Visual Impairment and Blindness in Ocular Toxoplasmosis CasesDocument3 pagesVisual Impairment and Blindness in Ocular Toxoplasmosis CasesFernandio GibranNo ratings yet

- Clinical Presentation and Microbial Analyses of Contact Lens Keratitis An Epidemiologic StudyDocument4 pagesClinical Presentation and Microbial Analyses of Contact Lens Keratitis An Epidemiologic StudyFi NoNo ratings yet

- Contact Lenses in Pediatrics CLIPStudyDocument7 pagesContact Lenses in Pediatrics CLIPStudyLorena MendozaNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Amblyopia in Primary School Children in Qassim Province, Kingdom of Saudi ArabiaDocument7 pagesPrevalence of Amblyopia in Primary School Children in Qassim Province, Kingdom of Saudi ArabiaSyarifah Thalita NabillaNo ratings yet

- Samuelov 2018Document5 pagesSamuelov 2018SALMA HANINANo ratings yet

- Childhood Glaucoma: An Overview: Parul Singh, Yogesh Kumar, Manoj Tyagi, Krishna Kuldeep, Parmeshwari Das SharmaDocument7 pagesChildhood Glaucoma: An Overview: Parul Singh, Yogesh Kumar, Manoj Tyagi, Krishna Kuldeep, Parmeshwari Das SharmaResa_G1A110068No ratings yet

- Intracranial Tumors: An Ophthalmic Perspective: DR M Hemanandini, DR P Sumathi, DR P A KochamiDocument3 pagesIntracranial Tumors: An Ophthalmic Perspective: DR M Hemanandini, DR P Sumathi, DR P A Kochamiwolfang2001No ratings yet

- Factor D Riesgo Glaucoma AfaquiaDocument6 pagesFactor D Riesgo Glaucoma AfaquiaShirley M. Cerro RomeroNo ratings yet

- Paediatric Catarct Review ArticleDocument8 pagesPaediatric Catarct Review ArticleSana ParveenNo ratings yet

- Complications of Pediatric Cataract Surgery and Intraocular Lens ImplantationDocument4 pagesComplications of Pediatric Cataract Surgery and Intraocular Lens ImplantationnurhariNo ratings yet

- 10 1097@MD 0000000000008003Document6 pages10 1097@MD 0000000000008003asfwegereNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Malocclusion in Children With Sleep Disordered BreathingDocument4 pagesPrevalence of Malocclusion in Children With Sleep Disordered BreathingMu'taz ArmanNo ratings yet

- Guideline Vision 5Document3 pagesGuideline Vision 5Abigail PheiliaNo ratings yet

- Congenital Cataract: Morphology and Management: Sana Nadeem, Muhammad Ayub, Humaira FawadDocument5 pagesCongenital Cataract: Morphology and Management: Sana Nadeem, Muhammad Ayub, Humaira FawadSherry CkyNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Automated Preschool Vision Screening: A 10-Year, Evidence-Based UpdateDocument5 pagesGuidelines For Automated Preschool Vision Screening: A 10-Year, Evidence-Based UpdateSyarifah Thalita NabillaNo ratings yet

- Cataracts Pathophysiology and Managements: Abdulrahman Zaid AlshamraniDocument4 pagesCataracts Pathophysiology and Managements: Abdulrahman Zaid AlshamraniOcha24 TupamahuNo ratings yet

- Draft CPG Management of Atopic EczemaDocument61 pagesDraft CPG Management of Atopic EczemaVisaagan KalaithasanNo ratings yet

- The Case of Martin ThomasDocument2 pagesThe Case of Martin Thomascfournier1982No ratings yet

- Prolonged and Postterm Pregnancy: Roxane Rampersad and George A. MaconesDocument7 pagesProlonged and Postterm Pregnancy: Roxane Rampersad and George A. MaconesAphreLbecasean WaeNo ratings yet

- BC-3200 Hematology Analyzer Quick Operation Guide: Control Review / AnalysisDocument2 pagesBC-3200 Hematology Analyzer Quick Operation Guide: Control Review / AnalysisGpo OwuorNo ratings yet

- Scientific Framework of Homeopathy Evidence Based HomeopathyDocument62 pagesScientific Framework of Homeopathy Evidence Based HomeopathyIrushaNo ratings yet

- Themaddoxrodtest PDFDocument4 pagesThemaddoxrodtest PDFdechastraNo ratings yet

- Assessing Cranial NerveDocument3 pagesAssessing Cranial NerveFelwa LaguioNo ratings yet

- Evaluationofthe Injuredrunner: Eric Magrum,, Robert P. WilderDocument15 pagesEvaluationofthe Injuredrunner: Eric Magrum,, Robert P. WilderAndréia PicançoNo ratings yet

- Human Reproduction QuestionsDocument2 pagesHuman Reproduction Questionsapi-220690063No ratings yet

- Facial Nerve Palsy in Newborn PeriodDocument5 pagesFacial Nerve Palsy in Newborn PeriodjajNo ratings yet

- Lab ReportDocument5 pagesLab ReportsuniNo ratings yet

- Extreme Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes: KSM Obstetri Dan Ginekologi Rumah Sakit Umum Pusat PersahabatanDocument27 pagesExtreme Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes: KSM Obstetri Dan Ginekologi Rumah Sakit Umum Pusat Persahabatanrilla saeliputriNo ratings yet

- DegluciónDocument9 pagesDegluciónNatalia Alfaro PetzoldNo ratings yet

- Prof. Dr. Dr. Hardiono D. Pusponegoro, Spa (K) : EducationDocument48 pagesProf. Dr. Dr. Hardiono D. Pusponegoro, Spa (K) : EducationKholid DamriNo ratings yet

- LENTIGODocument4 pagesLENTIGONisaNo ratings yet

- EP 860 Owners ManualDocument6 pagesEP 860 Owners Manualimmortality2045_8419No ratings yet

- Applied PalynologyDocument2 pagesApplied PalynologySanjoy NingthoujamNo ratings yet

- Blunt Abdominal Trauma MedicationDocument8 pagesBlunt Abdominal Trauma MedicationYudis Wira PratamaNo ratings yet