Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly-2014-Billings-38-58

Uploaded by

syed tanveerCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly-2014-Billings-38-58

Uploaded by

syed tanveerCopyright:

Available Formats

514416

research-article2014

JMQXXX10.1177/1077699013514416Journalism & Mass Communication QuarterlyBillings et al.

Agenda Setting and Sports

Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly

2014, Vol. 91(1) 38–58

(Re)Calling London: The © 2014 AEJMC

Reprints and permissions:

Gender Frame Agenda within sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1077699013514416

NBC’s Primetime Broadcast jmcq.sagepub.com

of the 2012 Olympiad

Andrew C. Billings1, James R. Angelini2,

Paul J. MacArthur3, Kimberly Bissell1,

and Lauren R. Smith4

Abstract

All sixty-nine hours of National Broadcasting Company’s (NBC) 2012 primetime

Summer Olympic telecast were analyzed, revealing significant gender trends. For the

first time in any scholarly study of NBC’s coverage of the games, women athletes

received the majority of the clock-time and on-air mentions. However, dialogues

surrounding the attributions of success and failure of athletes, as well as depictions of

physicality and personality, contained some divergences by gender.

Keywords

framing, communication theory, broadcast, content analysis, television, gender

In an age where most televised sports are still a “boy’s club,”1 the Olympics are a rela-

tive anomaly, featuring a plethora of women athletes competing in virtually all of the

same sports as men. While ESPN’s SportsCenter offers women’s sports just 1.4% of

the time,2 the 2012 London Olympic Games consisted of an overall athletic population

that was 44% women.3 Sixteen years after National Broadcasting Company (NBC)

dubbed the Atlanta Summer Games as the Olympics of the women,4 signs of women’s

1University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, USA

2University of Delaware, Newark, DE, USA

3Utica College, Utica, NY, USA

4Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA

Corresponding Author:

Andrew C. Billings, University of Alabama, P.O. Box 870152, Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35487, USA.

Email: acbillings@ua.edu

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

Billings et al. 39

progress continued to percolate surrounding the Olympic Games: every competing

national team had at least one woman member with the new inclusions of Saudi

Arabia, Qatar, and Brunei;5 both the United States and Canadian teams had slightly

more women athletes than men.6 Thus, a potential paradox exists as critics have found

gender differences in the production7 and description8 of women’s sporting events,

while signs of increased participation could be viewed as progress for women in

sports.

One decade after Bernstein queried whether it was “time for a victory lap,”9 the

Olympic telecast remains the pinnacle of analyses of gender treatment in mediated

sports.10 While part of the reason can be traced to the increased population of women

athletes and the relative notion that people will watch the games regardless of an ath-

lete’s gender as long as their home nation is competitive,11 another reason for the

intense focus on gender in the Olympics arises from the incredible magnitude of media

permeation. The 2012 London Summer Games had a global reach of approximately

3.6 billion unique viewers spread across 220 territories and countries.12 In the United

States, NBCUniversal offered 5,535 hours of Olympic coverage in a variety of media

formats.13 The London games set a U.S. viewership record, with 217 million Americans

watching some portion of NBCUniversal’s coverage.14 The most important compo-

nent of NBCUniversal’s Olympic coverage, the NBC broadcast network’s primetime

telecast, averaged 31.1 million viewers15 and generated more than 80% of the com-

pany’s Olympic ad revenue.16

Thus, the Olympics are an important media event for the analysis of mediated gen-

der issues17 because of the large viewership, the increased participation of both men

and women athletes, and the potential to influence wide swaths of populations. Such

influence should not be understated, as “history is not always written by the winners,

it is also written by those with the television rights.”18

This study will analyze the crown jewel of the largest sports media event in history:

the NBC broadcast network primetime telecast of the 2012 Olympic Games. Through

the examination of clock-time, overall salience, and attributed descriptors to and about

men and women athletes, insights can be offered regarding the role of gender in the

ultimate case of media saturation.

Related Literature

Whether women have reached participatory equality in the Olympic Games remains a

question for debate, but there is no question substantial progress has been made since

the Modern Olympic Games were introduced in 1896. Women were not allowed to

compete in the 1896 games, and though women participated in the 1900 Paris games,19

Pierre de Coubertin never embraced female participation in the Olympics. Decades

after women had gained entrance to the games, de Coubertin stated, “The only real

Olympic hero . . . is the individual adult male. Therefore, no women or team sports.”20

While fewer than two-dozen women competed in 1900,21 the 2012 games featured a

panoply of women athletes from a variety of backgrounds and nations.

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

40 Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 91(1)

Social identity theory22 references how people associate or disassociate with vari-

ous groups, particularly how their presumed interests and degree of appropriateness

within and among various groups result in self-made partitions of social classification.

Activities with traditionally masculine participation, such as sports, often forge men as

a tacitly defined in-group, with women developing a cognitive set of cues that results

in seeing sports as an out-group activity. While sport remains a masculine domain,23

the Olympics remain the outlier, offering compelling avenues for the exploration of

social identity-based communicative investigations. Put succinctly, it may be the case

that while women continue to feel “outsider” status24 within broadly defined sport,

they may feel much more of an inclusive sense specifically within Olympic-based

sport,25 at least partially because of the personalized, episodic nature in which the

Olympics are rendered.

When combined with media content-oriented notions of framing,26 one must query

the degree to which men and women Olympians and Olympic sports are offered by

NBC’s broadcast in terms of selection, emphasis, and exclusion.27 Given the potential

gap between sport participation and sport media exposure,28 such gendered differences

will be reviewed in regard to (1) clock-time/exposure differences, (2) salience devia-

tions, and (3) athletic depictions (regarding success and failure as well as physicality

and personality).

Gendered Clock-Time in the Olympic Telecast

Considerable work has focused on the amount of coverage devoted to men and women

athletes in sports in general. These tend to result in findings in which women’s sports

are either diminished to single-digit media exposure percentages29 or relegated to

ancillary networks or websites, such as ESPNW.30 Within NBC’s Olympic broadcast,

however, results have been quite different. Without question, the Olympics feature the

greatest spotlight for women athletes of any American sports media product. Remaining

questions surround issues of equality and degree of coverage.

Two postulates consistent throughout prior research are that (1) the Summer

Olympic broadcast features women athletes and sports at a significantly higher rate

than the Winter Olympic correlate and (2) the Summer Olympic broadcast still consis-

tently shows a higher proportion of men athletes than women athletes. Winter Olympic

analyses31 found that men athletes were shown more than women by a nearly two-to-

one ratio when excluding pairs competitions. Meanwhile, the Summer Olympic analy-

ses have resulted in much closer margins, albeit still privileging men’s competitions

over women’s. In 1996, NBC promoted women athletes the majority of the time, yet

favored men’s athletics by a relatively slim 53% to 47% margin.32 Subsequent analy-

ses of the Summer Olympics33 have shown these same margins that appear small, yet

are nonetheless statistically significant when taken over the course of a seventeen-

night broadcast, still existed in the most recent Summer Olympic analyses34 as NBC’s

coverage consisted of 54.2% men’s athletics and 45.8% women’s athletics in the 2008

games. Clock-time disparities favoring men in the Summer Olympics have also been

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

Billings et al. 41

detected in other studies.35 While London’s Olympic Games represent the highest rate

of women’s athletic participation to date, the consistent significant differences found

in prior studies result in the following clock-time hypothesis:

H1: Women athletes will receive less overall clock-time than men athletes in

NBC’s primetime broadcast of the 2012 London Olympics.

Gendered Salience in the Olympic Telecast

Another measure of Olympic media gender equity pertains to the salience of NBC’s

coverage, traditionally unpacked as the number of times each athlete’s name is spoken

within the telecast and operationalized as a “mention.”36 Such analyses tended to hew

along similar gender proportional lines to that of clock-time, finding that the majority

of the mentions in the primetime Olympic broadcast are of men athletes, while an even

greater proportion of the most-mentioned athletes—typically around two-thirds—are

men.37 As such, two additional hypotheses were postulated based on the composite of

these findings:

H2: The majority of the top-twenty most-mentioned athletes in NBC’s primetime

broadcast will be men.

H3: The majority of athlete name mentions in NBC’s primetime broadcast will be

of men.

In addition, the mentions within the telecast will also include analysis of the men-

tions within pre-produced spots for both (1) athlete profiles (within the telecast) and

(2) network promotion of the Olympics (embedded within the commercial break). As

such, two research questions are formulated to examine those differences:

RQ1: Will the network promos aired during NBC’s primetime Olympic broadcasts

contain more mentions of men or women athletes?

RQ2: Will the athlete profiles aired during NBC’s primetime Olympic broadcasts

contain more mentions of men or women athletes?

Gender Descriptions in the Olympic Telecast

Perhaps the largest body of research related to gender and sport focuses on the lan-

guage frequently employed within mediated renderings.38 Scholars such as Blinde,

Greendorfer, and Shenker see media coverage of women as a broader reflection of

gender ideology,39 while others have regarded women’s mediated sports as being

opportunities to “add sex and stir.”40 Gendered linguistic differences within mediated

sport have been found in a multitude of nations41 and, indeed, throughout history.42

These linguistic differences in more recent Olympic telecasts have not been deemed

as blatant as many of the biased renderings outside the Olympics43 or of Olympics

from decades ago.44 Twenty-first-century studies of gender attributions in the Summer

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

42 Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 91(1)

Olympics, however, have revealed linguistic differences between men and women

athletes.45 Markula may capture the sentiment within the aggregate of international

Olympic media, noting that “while women receive increased coverage during the

major events like the Olympic Games . . . women’s sport is ideologically controlled by

trivializing women’s performances.”46 NBC’s telecast, however, has been less likely

to trivialize performances by gender than describe them in demonstrably different

ways.47

Studies of depictions of men and women athletes48 within the Summer Games have

found that the majority of commentary focuses upon attributions of success and failure

of each athletic performance. Recent studies reveal that while attributions have signifi-

cantly differed by the gender of athlete, such differences have not proven to be consis-

tent over the course of a series of Olympic telecasts. For instance, the 2004 telecast

contained an increased tendency for male athletes to have their successes attributed to

courage, while women were more likely to have their successes credited to courage in

the 2006 and 2010 telecasts.49 Similarly, the last Summer Olympic investigation50

found men athletes were ascribed more comments about their strength resulting in

athletic success—a finding revealed in past analyses,51 yet not in others.52 Thus,

authors have concluded that such inconsistency of taxonomical findings are important

and should be subject to subsequent longitudinal research, yet “should be classified as

gender differences rather than stereotypes.”53 As such, the final two hypotheses for

this study have been constructed around the notion of difference more than the pres-

ence of bias or stereotyping:

H4: NBC employees will employ different performance taxonomies when describ-

ing the athletic successes and failures of female athletes than when describing male

athletes.

H5: NBC employees will employ different personality and physicality taxonomies

when describing the external factors surrounding female athletes than when sur-

rounding male athletes.

Method

The full sixty-nine broadcast hours of NBC’s Olympic primetime coverage were uti-

lized during the seventeen nights of the 2012 Summer Olympics (July 27-August 12),

representing 100% of NBC’s scheduled primetime coverage (which often aired until

12 a.m. EDT). Only comments spoken by network-employed individuals were ana-

lyzed for descriptors and mentions of athlete names because this dialogue can be

largely scripted and supervised by NBC editors and producers, a process consistent

with studies of sports media framing, as producers impact what is shown while

announcers shape the dialogue arising from these airtime decisions.54 Those network

employees included host commentators (Bob Costas), on-site reporters (e.g., Andrea

Kremer, Heather Cox), special assignment reporters (e.g., Mary Carillo, Ryan

Seacrest), color commentators (e.g., Ato Boldon, Cynthia Potter), and all play-by-play

announcers for both individual and team sports (e.g., Dan Hicks, Elfi Schlegel).

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

Billings et al. 43

Three methods of coding were applied to each hour of Olympic coverage. The first

method of coding pertained to the amount of time devoted to men’s and women’s

sports. To calculate this, a single researcher (incorporating DVD recorder timers) mea-

sured and entered (to the millisecond) the total amount of time devoted to each event,

making distinctions between men, women, and mixed gender sports. Any time spent

at the actual athletic site, on a profile about an athlete of that sport, or host commentary

about a specific sport was recorded (including two NBC specials, one on swimmer

Michael Phelps, the other on the twentieth anniversary of men’s basketball’s Dream

Team).

The second type of coding looked at the commentator’s actual use of the athletes’

names. Twelve coders watched each evening’s broadcast and logged/counted every

mention of every athlete by any employee of NBC.

For the third method related to athletic descriptors, the unit of analysis was the

descriptor (defined as any adjective, adjectival phrase, adverb, or adverbial phrase)

used by a network-employed individual, and all hours were coded for (1) the athlete’s

sport (2) the gender of the athlete (man or woman), (3) the ethnicity of the athlete

(Asian, black, Hispanic, Middle Eastern, white, or other), (4) the nationality of the

athlete (American or non-American), (5) the gender of the announcer (man or woman),

and (6) the specific word-for-word descriptive phrase. Then, the descriptors were clas-

sified using the Billings and Eastman taxonomy,55 which divides commentary into

three recognizable categories: (1) attributions of success/failure (i.e., descriptions of

the immediately viewable athletic performance), (2) depictions of personality/physi-

cality (i.e., descriptions of external variables of athletes not directly attributable to the

viewed athletic performance), and (3) neutral (i.e., comments that do not describe the

athletic performance or depict the personality and/or physicality of the athlete—

largely factual play-by-play dialogue). In all, sixteen classification categories were

implemented for the analysis, encompassing comments pertaining to (1) concentration

(i.e., “she has been the portrait of concentration the past few moments”), (2) strength-

based athletic skill (i.e., “nowhere near enough power”), (3) talent/ability-based ath-

letic skills (i.e., “she nailed her turn”), (4) composure (i.e., “feeling the pressure”), (5)

commitment (i.e., “one of the hardest working gymnasts out there”), (6) courage (i.e.,

“showed a bit of guts there”), (7) experience (i.e., “didn’t medal in Beijing”), (8) intel-

ligence (i.e., “very crafty”), (9) athletic consonance (i.e., “tough break”), (10) outgo-

ing/extroverted (i.e., “effervescent”), (11) modest/introverted (i.e., “quiet young

lady”), (12) emotional (i.e., “so amped”), (13) attractiveness (i.e., “comes in with a

more mature look”), (14) size/parts of body (i.e., “the tallest blocker in the competi-

tion”), (15) background (i.e., “is a big Justin Beiber fan”), and (16) other. Using

Cohen’s formula,56 a second researcher coded 20% of the database and reliabilities

were determined for the following variables: (1) the gender of the athlete (κ = 1.00),

(2) the ethnicity of the athlete (κ = .98), (3) the nationality of the athlete (κ = 1.00), (4)

the gender of the announcer (κ = 1.00), (5) the word-for-word descriptor or descriptive

phrase (κ = .83), and (6) the name of the sport being discussed (κ = 1.00). Overall

inter-coder reliability using Cohen’s kappa exceeded 96% when combining all

categories.

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

44 Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 91(1)

Once all data were analyzed and tables created, chi-square analysis was employed

to determine significant differences between groups by using the percentage of overall

comments as expected frequencies. For example, because 44.7% of all attributions for

success were about men athletes, it was expected that roughly the same proportion

(44.7%) of comments about concentration, skill, composure, commitment, attractive-

ness, and so on should be established as expected frequencies for men athletes, and

that significant deviations would be substantially more meaningful than employing .50

as an expected frequency for each individual category. For the clock-time table, how-

ever, .50 was inserted as the expected frequency as clock-time measures raw exposure,

whereas the descriptor differences are contingent on how much exposure each athlete

and sport receives.

Results

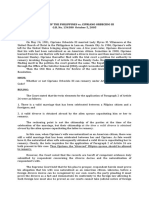

Content analysis of NBC’s 2012 London Olympic telecast resulted in just less

than forty-five total hours of coverage. H1 predicted that women athletes would

receive less overall clock-time than men athletes in the primetime telecast of the

London Games. Table 1 reports how this coverage was divided by both sport and

gender.

As outlined in Table 1, thirty-two total sports were included in NBC’s seventeen

days of coverage of the Games; however, only seven received an hour or more of total

coverage within the total composite. As Table 1 shows, women received 54.8% of the

primetime coverage compared with 45.2% of the coverage devoted to men, a signifi-

cant difference (χ2 = 1453.87, df = 1, p < .001). Within the seven sports that received

more than one hour of airtime, collectively accounting for more than 96.9% of NBC’s

airtime, women received more primetime airtime in beach volleyball (χ2 = 9663.74,

df = 1, p < .001), diving (χ2= 5.32, df =1, p < .05), gymnastics (χ2 = 3634.11, df = 1,

p < .001), and volleyball (χ2 = 1371.15, df = 1, p < .001). Conversely, men’s sports

received greater airtime in cycling (χ2 = 891.09, df = 1, p < .001), swimming (χ2 =

895.67, df = 1, p < .001), and track and field (χ2 = 504.33 df = 1, p < .001). Consequently,

H1 was not supported.

H2 predicted that the majority of the top-twenty most-mentioned athletes in the

primetime broadcast would be men. Table 2 reports the names of the top-twenty most-

mentioned athletes in the London Games.

As shown in Table 2, while H2 predicted that there would be more male athletes on

the most-mentioned list, the opposite occurred. Fourteen of the top-twenty most-

mentioned athletes were female, with beach volleyballer Misty May-Treanor receiv-

ing the most mentions (591) as compared with the male athlete receiving the highest

number of mentions, Michael Phelps (559). Kerri Walsh Jennings received the third-

highest number of mentions (539) and then the number of mentions for any athlete

dropped by 241 (Ryan Lochte, 298). Thus, H2 was also not supported, as women

athletes represented the majority of athletes on the most-mentioned list.

H3 predicted that the majority of the athlete name mentions in the primetime broad-

cast would be of men. Table 3 reports the mentions by gender and NBC source.

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

Billings et al. 45

Table 1. Clock-Time by Gender in the 2012 London Summer Olympics.

Eventa,b Men Women Mixed/pairs Total χ2 df p

Archery 0:0:12 0:00:00 — 0:00:12 12.00 1 .001

Badminton 0:0:02 0:00:00 0:00:00 0:00:02

Basketball 0:25:15 0:01:31 — 0:26:46 1262.63 1 .001

Beach volleyball 0:22:11 3:39:28 — 4:01:39 9663.74 1 .001

Boxing 0:00:04 0:00:05 — 0:00:09

Canoe/kayak 0:00:00 0:00:00 — 0:00:00

Cycling 0:46:52 0:16:15 — 1:03:07 891.09 1 .001

Diving 2:38:38 2:43:59 — 5:22:37 5.32 1 .02

Equestrian — — 0:01:31 0:01:31

Fencing 0:00:01 0:00:03 — 0:00:04

Field hockey 0:00:00 0:00:06 — 0:00:06

Gymnastics 3:40:44 6:57:20 — 10:38:04 3634.11 1 .001

Handball 0:00:05 0:00:00 — 0:00:05

Judo 0:00:00 0:00:00 — 0:00:00

Modern pentathlon 0:00:00 0:00:00 — 0:00:00

Rhythmic gymnastics 0:00:00 0:00:06 — 0:00:06

Rowing 0:00:07 0:15:08 — 0:15:15 887.21 1 .001

Sailing 0:00:00 0:00:00 — 0:00:00

Shooting 0:00:00 0:01:15 — 0:01:15 75.00 1 .001

Soccer 0:01:06 0:15:36 — 0:16:42 755.39 1 .001

Swimming 5:37:19 4:04:09 — 9:41:28 895.67 1 .001

Synchronized swimming 0:00:00 0:00:05 — 0:00:05

Table tennis 0:00:00 0:00:00 — 0:00:00

Taekwondo 0:00:00 0:00:00 — 0:00:00

Tennis 0:03:39 0:02:15 0:00:00 0:05:54 19.93 1 .001

Track and field 5:35:13 4:24:14 — 9:59:27 504.33 1 .001

Trampoline 0:06:50 0:00:02 — 0:06:52 404.04 1 .001

Triathlon 0:00:09 0:00:59 — 0:01:08 36.76 1 .001

Volleyball 0:25:48 1:13:25 — 1:39:13 1371.15 1 .001

Water polo 0:00:13 0:02:05 — 0:02:18 90.90 1 .001

Weightlifting 0:00:45 0:00:06 — 0:00:51 29.82 1 .001

Wrestling 0:00:49 0:00:00 — 0:00:49 49.00 1 .001

Total 19:46:02 23:58:12 0:01:31 43:45:45 1453.87 1 .001

Overall percentage 45.2 54.8 0.06

When excluding mixed 45.2 54.8

aAt the time of the 2012 London Summer Olympics, there are no men’s events in the disciplines of Rhythmic

Gymnastics and Synchronized Swimming.

bMixed doubles events were held for the disciplines of Badminton and Tennis, though no primetime coverage was

devoted to these events. Equestrian is competed as a mixed gender discipline.

As shown in Table 3, male athletes received 5,793 total mentions (340 per prime-

time broadcast), whereas female athletes received 6,659 total mentions (392 per pri-

metime broadcast), a significant difference (χ2 = 60.23, df = 1, p < .05). Significant

differences, however, were offered by source with the host (Bob Costas) more likely

to mention male athletes (χ2 = 4.64, df = 1, p < .05) and female reporters more likely

to mention female athletes (χ2 = 11.61, df = 1, p < .001). Thus, H3 was also not sup-

ported, as women athletes were highlighted significantly more than men athletes

within the seventeen days of coverage.

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

46 Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 91(1)

Table 2. Top-Twenty Most-Mentioned Athletes in the 2012 Olympics.

Name Sport Gender Mentions

1. Misty May-Treanor Beach volleyball F 591

2. Michael Phelps Swimming M 559

3. Kerri Walsh Jennings Beach volleyball F 539

4. Ryan Lochte Swimming M 298

5. Usain Bolt Track and field M 244

6. Missy Franklin Swimming F 234

7. Gabby Douglas Gymnastics F 193

8. Aly Raisman Gymnastics F 169

9. Allyson Felix Track and field F 131

10. Tom Daley Diving M 128

11. Jordyn Wieber Gymnastics F 125

12. Allison Schmitt Swimming F 123

13. Yohan Blake Track and field M 108

14. Rebecca Soni Swimming F 102

15. Sanya Richards-Ross Track and field F 101

16. Jen Kessy Beach volleyball F 100

17. Carmelita Jeter Track and field F 99

18. Xue Chen Beach volleyball F 95

19. Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce Track and field F 89

20. Danell Leyva Gymnastics M 88

Table 3. Sources and Distribution of Mentions of Athletes by Name in the 2012 Olympics.

Reporters

n per % per

Source n night night Host M F Profiles Promos

Gender/ethnicity/nationality

Male 5,793 340.8 46.5 335a 4,863 163b 394c 38

Female 6,659 391.7 53.5 326a 5,753 291b 250c 39

Total 12,452 732.5 100.0 661 10,616 454 644 77

aχ2 = 4.64, df = 1, p < .05.

bχ2 = 11.61, df = 1, p < .001.

cχ2 = 78.55, df = 1, p < .001.

RQ1 queried whether differences with mentions would be found in pre-produced

profiles. Significant differences favoring male athletes were found within profiles

(χ2 = 78.55, df = 1, p < .001).

RQ2 queried whether these differences would be found in promotional spots.

The largest degree of gender equivalency existed in this area, as female athletes had

one more single promotional spot mention than male athletes, a non-significant

difference.

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

Billings et al. 47

Table 4. Descriptive Analysis of Success/Failure by Gender.

Gender

Ratio of success to

Success Failure failure

Men Women Men Women Men Women

Concentration 13 18 4 11 3.3 1.6

Athletic strength 45 70 3 9 15.0 7.8

Athletic skill 1,650 2,097 487 630 3.4 3.3

Composure 48 77 23a 47a 2.1 1.6

Commitment 24 24 7 5 3.4 4.8

Courage 18 31 2 6 9.0 5.2

Experience 821b 849b 79 78 10.4 10.9

Intelligence 33 55 6 4 5.5 13.8

Consonance 149c 230c 43 35 3.5 6.6

Total 2,801 3,451 654 825 4.3 4.2

aχ2 = 3.97, df = 1, p < .05.

bχ2 = 13.51, df = 1, p < .001.

cχ2 = 4.43, df = 1, p < .05.

H4 predicted that NBC employees would employ different performance taxono-

mies when describing the athletic successes and failures of male and female athletes.

Table 4 highlights the frequencies in each taxonomical category, with significant dif-

ferences noted.

Before delving into the findings of Table 4, it is important to note that these find-

ings should be considered in the context of proportionality, which influences expected

frequencies. Thus, women had more total mentions (likely the result of 9.6% more

airtime) and expected frequencies were adjusted to reflect the balance of the overall

descriptor database. Once that was accounted for, men were more likely to be depicted

as succeeding because of experience (χ2 = 3.97, df = 1, p < .05), while women were

more like to have their successes attributed to consonance (χ2 = 4.43, df = 1, p < .05).

Regarding athletic failures, the one statistically significant difference resided in the

women’s category, as they were more likely to have their failures attributed to lack of

composure (χ2 = 3.97, df = 1, p < .05). In sum, the majority of the categories did not

yield significant differences, yet these three significant attributions provide some sup-

port for H4.

H5 predicted that NBC employees would use different personality/physicality tax-

onomies when describing the external factors surrounding male and female athletes.

As Table 5 highlights, men and women were described in demonstrably different

manners in three main external characteristics. Women athletes received increased

frequencies of comments about their emotions (χ2 = 17.76, df = 1, p < .001) and appear-

ance (χ2 = 6.41, df = 1, p = .02) than men. Conversely, the one area in which men

received proportionally more comments than women was in the area of the

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

48 Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 91(1)

Table 5. Descriptive Analysis of Personality/Physicality Descriptors by Gender.

Gender

Men Women

Outgoing/extroverted 27 24

Modest/introverted 4 11

Emotional 82a 156a

Attractiveness 2b 12b

Size/parts of body 68 87

Background 2,164 2,417

Other/neutral 1,395c 1,330c

Total 3,742 4,037

aχ2 = 17.76, df = 1, p < .001.

bχ2 = 6.41, df = 1, p = .02.

cχ2 = 10.41, df = 1, p = .005.

unclassifiable, labeled “other/neutral” (χ2 = 10.41, df = 1, p = .005). Given that 44.4%

of the categories yielded differences by gender, H5 was partially supported.

Discussion

Forty years after the passage of Title IX—the 1972 education amendment that prohib-

its educational institutions that receive federal financial assistance from discriminating

based on gender—the seventeen-night NBC network primetime Olympic broadcast

proved to be an historic chapter in televised sports. As scholars began compiling com-

plete content analysis data of U.S.-based broadcast network primetime Olympic tele-

casts with the 1994 games, NBC’s 2012 Olympic telecast marks (1) the first time

women received more overall clock-time than men, (2) the first time women tallied

more appearances than men in the most-mentioned athletes category, and (3) the first

time women athletes received more overall mentions than male athletes.57 When

viewed through Gitlin’s observation that media frames are “persistent patterns of cog-

nition, interpretation, and presentation of selection, emphasis, and exclusion,”58 it is

clear that NBC’s persistent emphasis on male athletes within its primetime Olympic

broadcast was broken in 2012.

NBC’s increased focus on women’s sports may be partly credited to the success of

the U.S. Women’s Olympic team, which was a dominant force at the 2012 games.

Team USA women won more medals than American men (63% of the U.S. gold and

55.7% of all U.S. medals). In fact, with the exceptions of the People’s Republic of

China, Great Britain, and the Russian Federation—U.S. women Olympians claimed

more medals than any country’s combined male and female total.59 Indeed, if, as

Tuchman suggests, “The news frame organizes everyday reality and the news frame is

part and parcel of everyday reality . . .”60 NBC’s primetime broadcast could be seen as

both presenting and reflecting Team USA women’s dominance. That, however, would

oversimplify NBC’s primetime broadcast presentation.

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

Billings et al. 49

NBC’s increased attention to women athletes was not the result of the network

devoting significant primetime coverage to a variety of sports in which U.S. women

were successful. Rather, the imbalance between women’s and men’s airtime appears

to be largely because of the network’s focus on women’s gymnastics and women’s

beach volleyball. In both sports, women received more than three hours of additional

coverage when compared with their male counterparts. For instance, in the case of

beach volleyball, the U.S. team of Misty May-Treanor and Kerri Walsh Jennings

received a combined 1,130 mentions, representing more than the overall gender gap of

866 mentions favoring women athletes in the composite analysis.

Gymnastics and beach volleyball, however, carry their own gender baggage.

Gymnastics has been dubbed a sex-appropriate sport for women,61 and some studies of

college students have revealed they perceived it to be a feminine sport.62 The sexual-

ized nature of beach volleyball, where women are often wearing tight-fitting bikinis,

has been criticized by some,63 and praised by others, with the mayor of London, Boris

Johnson, commenting, “there are semi-naked women playing beach volleyball . . .

glistening like wet otters . . .”64

NBC’s increased attention to these two women’s sports would seemingly comport

with Davis and Tuggle’s finding that “for female athletes to receive media coverage,

they must be involved in socially acceptable individual sports and/or sports that high-

light body type.”65 Certainly this theory would apply to gymnastics and beach volley-

ball. Yet, it is also worth noting that American men earned only one medal in

gymnastics and did not even qualify to compete in three of the six individual event

finals in gymnastics. American men earned zero beach volleyball medals. Meanwhile,

American women collected five medals in gymnastics (including a Team USA medal)

and the gold and silver in beach volleyball, where Misty May-Treanor and Kerri Walsh

Jennings won their third consecutive gold medal and remained undefeated in Olympic

competition. Thus, the heavy emphasis on women in these two sports may not be the

result of one single gender-based factor, but rather a collection of factors that include

the sport’s overall appeal to viewers, the gender appropriateness of the sport, the gen-

der-based predicted success of U.S. athletes in the sport, pre-Olympic Games public-

ity, celebrity, and overall Team USA performance.66 Collectively these factors may

provide insight into both television programmers’ decisions and the audience’s desires

to consume the television product.

The end game for NBCUniversal is, of course, ratings. The company’s attempt to

recoup its $1.18 billion spent on 2012 Olympic rights fees results in the network’s

cherry-picking the most desirable sports for its primetime network broadcast. As

Angelini and Billings observed, NBC devoted more than 90% of its primetime air to

five summer sports in 2008: beach volleyball, diving, gymnastics, swimming, and

track and field. This was replicated by the network in 2012.67 When agenda-setting

theory,68 which builds on Cohen’s assertion that the media “may not be successful

much of the time in telling people what to think, but (they are) stunningly successful

in telling their (audience) what to think about,”69 is employed, NBC’s emphasis on

these sports sets a primetime agenda focused on five sports at the expense of dozens

of others.

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

50 Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 91(1)

McCombs and Reynolds state that “the New York Times frequently plays an intra-

media agenda-setting role because appearance on the front page of the Times can

legitimize a topic as newsworthy.”70 Likewise, the power of NBC’s primetime broad-

cast as an intermedia agenda setter seems beyond question. With average audiences

that outstrip the other three major broadcast networks combined, NBC’s primetime

Olympic broadcast has taken competitors in non-mainstream sports and made them

into household names. While Michael Phelps’s record setting feats during the past two

Summer Games would have garnered significant attention in other media without

NBC pushing the gas pedal, the stars of May-Treanor, Walsh Jennings, and Gabby

Douglas would likely have been significantly dimmer had their performances been

relegated to NBC’s ancillary networks outside of primetime.

Outside of the five major sports, NBC’s programming decisions when viewed

through a gendered lens provide some interesting, if sometimes cloudy, insights into the

network’s strategy. Women’s soccer received significantly more airtime than men’s

soccer, but this can be attributed to USA Women’s Soccer winning gold and the celeb-

rity of the team, which had just lost the World Cup Final to Japan in 2011. Meanwhile,

USA men’s soccer failed to medal. News value was likely the main factor in the net-

work’s decision to favor men’s basketball over women’s. While both Team USA men

and women won gold, the men’s team received more coverage as it was a more salient

story. The National Basketball Association (NBA) players competing for Team USA

are international celebrities and the 2012 games marked the twentieth anniversary of

the legendary original Dream Team that transformed international basketball.

In these contexts, such news judgments seem reasonable. Yet, the explanations for

gender-based airtime differences in other sports do not seem as self-evident. Men’s

cycling received triple the airtime of women’s cycling, yet American men failed to

medal, while American women bagged four cycling medals. Meanwhile, in the first

time boxing has featured an Olympic women’s division, American women clinched

two medals, while American men secured four medals in wrestling. Yet, combined,

these two sports received less than one-minute of primetime coverage. Another curios-

ity would the case of Kim Rhode, an American shooter who earned a medal in her fifth

Olympiad in a row. Rhode’s gold-medal skeet shooting performance saw her become

the first woman to win three gold medals in shooting while tying a world record when

she hit 99 out of 100 clays. Such an historic performance by an athlete who has been

competing in the Olympics since 1998 would seem worthy of more than passing pri-

metime attention. Women’s shooting, however, received just seventy-five seconds of

primetime air, compared with zero for men. Though that time was exclusively devoted

to Rhode, the relatively meager primetime coverage relegated her to a tie for 412th on

the most-mentioned athletes list. Other sports where Americans medaled, such as judo

and taekwondo received no primetime coverage.

Durham notes that

decoding frames as historical records with an understanding of their ideological premises

is necessary to understand whose particular meanings are included in a generalized

version of history, whose are not, and on whose terms they are either included or

excluded.71

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

Billings et al. 51

To that end, in the United States, the primetime Olympic broadcast is controlled by

a multi-billion dollar media organization that has historically aimed its telecast toward

a female audience. The network has determined that combat sports, such as boxing, do

not appeal to female audiences.72 This gender-based programming agenda, however,

results in minimizing the accomplishments of many successful athletes on the most-

watched Olympic broadcast in favor of the competitors in five major sports. The

exclusion frame employed by the network creates true haves and have-nots among

Olympic competitors, regardless if they are male or female, American or

non-American.

In terms of salience, the importance of Michael Phelps in the 2012 broadcast should

not be overlooked. While Phelps received the second most mentions, behind Misty

May-Treanor, he was a central figure in the Olympic broadcast. His quest to break the

record for most medals ever won by an Olympian was highlighted extensively by

NBC over the course of several evenings. After he set the new record at twenty-two

medals, NBC made Phelps the subject of an hour-long primetime profile. The volume

of mentions May-Treanor and Walsh Jennings received was largely the result of the

back and forth nature of beach volleyball games that typically causes the athletes’

names to be mentioned more often during competition than swimmers. Thus, it would

be an error to interpret the exaggerated mentions for May-Treanor and Walsh Jennings

as meaning they were a more important story for the network than Phelps, who was,

by far, the most emphasized athlete in the telecast.

Noting the differences between framing and bias, Tankard observed that framing

“is a more sophisticated concept. It goes beyond notions of pro or con, favorable or

unfavorable, negative or positive. Framing adds the possibilities of additional, more

complex emotional responses and also adds a cognitive dimension . . .”73 When viewed

through this theoretical lens, the network’s gender-based descriptions require a

nuanced historical analysis. Of the twenty-five categories examined for attributions of

success, failure and personality/physicality descriptors, significant gender-based dif-

ferences appeared in only six (24%). Going back to 1994, this study marks the fourth

time that men have been more likely to have their success credited more to experience.

It marks the first time that women have been more likely to have their success credited

to consonance, which previously had been more likely credited to men in the 2004 and

2008 games. This also marks the first time women have been more likely to have their

failure attributed to a lack of composure. Thus, the attributions of failure and success

continue not to be divided cleanly by gender.

In the area of personality/physicality descriptors, the increased comments for men

in the other/neutral category is also a first, but the meaning behind this finding is dif-

ficult to determine, as, by their very nature, the comments are not easily categorized.

Two stereotypes, however, seemed to emerge, as female athletes were more likely to

be described as emotional and received significantly more comments about their

attractiveness. In the former area, there is not enough data to suggest the increased

comments toward women’s emotions are a network trend. From 1994 to 2010,

Olympic women were only more likely to receive comments about their emotions

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

52 Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 91(1)

once, during the 2010 games.74 Whether this recent increased attention to women’s

emotions is a short-term aberration or the beginning of a long-term trend is something

that will require further study. It is certainly possible that female competitors were

more likely to wear their emotions on their sleeve in the 2012 games, and thus their

emotions may have been more apparent on the surface than men’s. At the same time,

emotional displays by male and female athletes as well as spectators was a point of

discussion in media outlets as the 2012 Olympics were dubbed “the crying games.”75

The increased comments about women’s attractiveness during the 2012 games also

require closer examination. Women were more likely to receive comments about their

attractiveness during the 1994, 1996, and 1998 games.76 This finding, however, was

not replicated during the six Olympic telecasts from 2000 to 2010. While this tendency

on the part of network announcers has reemerged, its importance should not be over-

stated. The small overall number of comments about athlete attractiveness—fourteen

overall, which accounts for less than 0.09% of the descriptor database—indicates this

descriptor was not an important point of emphasis by network announcers. There was,

on average, less than one comment about athlete attractiveness per night. Compared

with three Olympiads from 1994 to 1998, where athlete attractiveness descriptors, on

average, accounted for 5.03% of the descriptor database,77 NBC’s comments about

this attribute were infinitesimal in 2012. Thus, this may not be a reemergence of ste-

reotypical descriptions of women by network announcers but, perhaps, a statistical

anomaly.

When the network commentary from the 2012 games is put into a longitudinal

context, it becomes evident that if there are clear consistent dialogic gender biases on

the part of the network announcers, they have not been detected in the studies that have

been conducted dating back to the 1994 games. No specific dialogic gendered differ-

ence appears in more than four of the ten games studied, and the most recent appear-

ance of one of the most prevalent differences (comments about women’s attractiveness)

is too minute to conclude it has much importance.

Tankard notes that “framing recognizes the ability of a text—or a media presenta-

tion—to define a situation, define the issues, and to set the terms of debate.”78 How

NBC defines the Olympic experience and the athletes who participate in the Games

remains an area that requires continued investigation. Future studies should be con-

ducted to determine if any gender-based dialogic trends develop, if women’s domi-

nance in clock-time and mentions is the beginning of trend or an aberration, and

whether NBC expands its coverage to a broader range of sports that could impact

overall trendlines.

Conclusion

The first woman to record an Olympic victory was Kyniska of Sparta, who did so in

396 and 392 BC. At the time, owners, not riders, were declared the victors in chariot

races and the team Kyniska funded won. She did not physically compete nor attend the

Games, as women were barred from the festivities. As Kyle notes,

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

Billings et al. 53

She had no major impact on the regulations and operation of the Ancient Olympics. Her

anomalous success did not alter the enduring ban on women at the games . . . Kyniska’s

chariot racing was not intended to liberate the games, empower female athletes, or force

discourse about gender roles in sport . . . (King) Agesilaus used his sister to show that

Olympic chariot victories were won by wealth and not by manly excellence.

In essence, her role was political: a way for her brother to shame his enemies by

“emasculating the Olympic chariot race.”79

Conversely, Olympic Swimming Gold Medalist, Donna de Varona, has asserted

that “(Title IX) not only transformed sport but our culture.”80 It could be argued that

Title IX has not only transformed women’s sport, but also “the biggest show on televi-

sion.”81 Over the past forty years, women’s sports participation has grown exponen-

tially in the United States. Popular women’s sports like the Federation Internationale

de Football Association (FIFA) Women’s World Cup made athletes like Brandi

Chastain mainstream celebrities, while increased focus on women’s college sports

such as the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s (NCAA) March Madness did

the same for players like Baylor’s Brittney Griner. Such women’s megasporting events

have proven to draw high ratings; the 2011 Women’s World Cup final between the

United States and Japan more than tripled the viewership of hockey’s Stanley Cup

final, while rivaling other major events such as the Daytona 500 and NBA Finals.82

Such a transformation would have been unforeseeable in 1972, when women’s athlet-

ics was relegated to individual/paired sports such as tennis or figure skating.

For years, NBC employees have claimed that the primetime broadcast focuses on

the best stories, regardless of gender.83 Opining that if women continued to make up a

large portion of the Olympic television audience and women won a large portion of

Team USA’s medals, NBC’s Tom Hammond said that the primetime network cover-

age would reflect those facts. “Television is a reactive medium,” he said. “We give the

people more of what they want to see than what they ought to see.”84 In 2012, NBC

reacted by presenting a network primetime Olympic broadcast that, for the first time,

favored women over men in three significant areas: clock-time, overall mentions, and

Top-Twenty mentions.

During the 2012 games, NBC believed women provided the most compelling sto-

ries for the primetime broadcast and followed through its programming. This was in

no small part because of the success of Team USA women. NBC has a long history of

highlighting successful American athletes in its primetime Olympic broadcasts and

the 2012 telecast appears to be no exception. As noted earlier, however, the success of

American athletes is one of many components impacting NBC Olympic programming

decisions. This did not result in gender parity, but rather a significant tilt in coverage

toward female athletes. Indeed, true gender parity on the NBC primetime broadcast

may be something that can only happen by accident. The unpredictable nature of the

games, and the ratings-based need to tell the stories that are most salient to the general

public, will always result in early and last-minute programming decisions that may

favor a particular gender. Nonetheless, at least for the moment, NBC cannot be criti-

cized for presenting a primetime Olympic broadcast that marginalizes women athletes

in favor of men.

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

54 Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 91(1)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Alexis March for her assistance with coding and Sal Tuzzeo at

Nielsen for his assistance clarifying some Nielsen data.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship,

and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of

this article.

Notes

1. Terry Adams and C. A. Tuggle, “ESPN’s SportsCenter and Coverage of Women’s

Athletics: It’s a Boy’s Club,” Mass Communication and Society 7 (2, 2004): 237-48.

2. Michael Messner and Cheryl Cooky, Gender in Televised Sports: News and Highlight Shows

(Los Angeles: University of Southern California, Center for Feminist Research, 2010).

3. David Segal, “Britain Takes a Final Bow,” New York Times, August 12, 2012, http://www.

nytimes.com/2012/08/13/sports/olympics/a-memorable-and-musical-olympic-closing-

ceremony.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0.

4. Andrew C. Billings, Olympic Media: Inside the Biggest Show on Television (London:

Routledge, 2008).

5. R. Scott-Elliott, “Every Olympic Nation Will Field Women as Saudi Arabia Caves,” in The

London-Independent, July 13, 2012, p. 10.

6. The Associated Press, “More Women than Men on U.S. Team,” New York Times, July

12, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/11/sports/olympics/more-women-than-men-

on-us-team.html?_r=0.

7. Kimberly L. Bissell and Andrea M. Duke, “Bump, Set, Spike: An Analysis of Commentary

and Camera Angles of Women’s Beach Volleyball during the 2004 Summer Olympics,”

Journal of Promotion Management 13 (1-2, 2007): 35-53; Jennifer D. Greer, Marie

Hardin, and Casey Homan, “‘Naturally’ Less Exciting? Visual Production of Men’s and

Women’s Track and Field Coverage during the 2004 Olympics,” Journal of Broadcasting

& Electronic Media 53 (2, 2009): 173-89.

8. Edward Ted M. Kian, Michael Mondello, and John Vincent, “ESPN? The Women’s

Sports Network? A Content Analysis of Internet Coverage of March Madness,” Journal of

Broadcasting & Electronic Media 53 (3, 2009): 477-95.

9. Alina Bernstein, “Is It Time for a Victory Lap? Changes in the Media Coverage of Women

in Sport,” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 37 (3-4, 2002): 415-28.

10. Greer, Hardin, and Homan, “‘Naturally’ Less Exciting?”; Kelly K. Davis and Charles

A. Tuggle, “A Gender Analysis of NBC’s Coverage of the 2008 Summer Olympics,”

Electronic News 6 (2, 2012): 51-66.

11. James R. Angelini, Andrew C. Billings, and Paul J. MacArthur, “The Nationalistic

Revolution Will Be Televised: The 2010 Vancouver Olympic Games on NBC,”

International Journal of Sport Communication 5 (2, 2012): 193-209.

12. International Olympic Committee, “Marketing Report London 2012,” 2012, http://www.

olympic.org/Documents/IOC_Marketing/London_2012/LR_IOC_MarketingReport_

medium_res1.pdf.

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

Billings et al. 55

13. Richard Deitsch, “The Olympic Television Guide,” The Olympic Television Guide, July

26, 2012.

14. Amy Chozick, “NBC Unpacks Trove of Data from Olympics,” New York Times, September

26, 2012, p. B3.

15. International Olympic Committee, “Factsheet: Women in the Olympic Movement,” 2012,

http://www.olympic.org/Documents/Reference_documents_Factsheets/Women_in_

Olympic_Movement.pdf.

16. Michael Hiestand, “NBC: ‘We Took a Big Bold Swing’ with Digital Coverage,” USA

Today, August 12, 2012, http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/sports/columnist/hiestand-tv/

story/2012-08-12/NBC-London-Olympics/57015258/1.

17. See, for example, Maurice Roche, “Mega-events and Media Culture: Sport and the

Olympics,” in Critical Readings: Sport Culture and the Media, ed. David Rowe

(Maidenhead, Berkshire, UK: Open University Press, 2004), 165-81.

18. Andrew C. Billings, Chelsea L. Brown, James H. Crout, Kristen E. McKenna, Bethany

A. Rice, Mary E. Timanus, and Jonathan Zeigler, “The Games through the NBC Lens:

Gender, Ethnic, and National Equity in the 2006 Torino Winter Olympics,” Journal of

Broadcasting & Electronic Media 52 (2, 2008): 215-30.

19. International Olympic Committee, “Factsheet: Women in the Olympic Movement.”

20. Yves-Pierre Boulonge, “Pierre De Coubertin and Women’s Sport,” Olympic Review 26

(31, 2003): 23-24.

21. International Olympic Committee, “Factsheet: Women in the Olympic Movement.”

22. Henri Tajfel and John C. Turner, “The Social Identity Theory of Inter-group Behavior,” in

Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 2nd ed., ed. Stephen Worchel and William G. Austin

(Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1985), 7-24.

23. Pamela J. Creedon, Women, Media and Sport: Challenging Gender Values (Thousand

Oaks, CA: SAGE, 1994); Marie Hardin and Jennifer D. Greer, “The Influence of Gender-

Role Socialization, Media Use and Sports Participation on Perceptions of Sex-appropriate

Sports,” The Journal of Sport Behavior 32 (2, 2009): 207-226.

24. See, for example, Todd W. Crosset, Outsiders in the Clubhouse: The World of Women’s

Professional Golf (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995).

25. See, for example, Marie Hardin, Scott Simpson, Erin Whiteside, and Kim Garris, “The

‘Gender War’ in U Sport: Winners and Losers in News Coverage of Title IX,” Mass

Communication and Society 9 (4, 2007): 429-46.

26. Erving Goffman, Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience (NY:

Harper & Row, 1974).

27. Todd Gitlin, The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media in the Making & Unmaking of the

New Left (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980).

28. See, for example, Ronald Bishop, “Missing in Action: Feature Coverage of Women’s

Sports in Sports Illustrated,” Journal of Sport & Social Issues 27 (2, 2003): 184-94.

29. See, for example, Messner and Cooky, Gender in Televised Sports; Jean O’Reilly and

Susan K. Cahn, Women and Sports in the United States (Boston: Northeastern University

Press, 2007).

30. Thomas P. Oates, “Representing the Audience: The Gendered Politics of Sport Media,”

Feminist Media Studies 12 (4, 2012): 603-607.

31. James R. Angelini, Paul J. MacArthur, and Andrew C. Billings, “What’s the Gendered

Story?” Vancouver’s Primetime Olympic Glory on NBC 56 (2, 2012): 261-79; Andrew C.

Billings and Susan T. Eastman, “Framing Identities: Gender, Ethnic, and National Parity

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

56 Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 91(1)

in Network Announcing of the 2002 Winter Olympics,” Journal of Communication 53 (4,

2003): 369-86.

32. See, for example, Billings, Olympic Media.

33. Andrew C. Billings and James R. Angelini, “Packaging the Games for Viewer Consumption:

Gender, Ethnicity, and Nationality in NBC’s Coverage of the 2004 Summer Olympics,”

Communication Quarterly 55 (1, 2007): 95-111.

34. Andrew C. Billings, James R. Angelini, and Andrea H. Duke, “Gendered Profiles of

Olympic History: Sportscaster Dialogue in the 2008 Beijing Olympics,” Journal of

Broadcasting & Electronic Media 54 (1, 2010): 9-23.

35. See, for example, Charles A. Tuggle, Suzanne Huffman, and Dana S. Rosengard,

“A Descriptive Analysis of NBC’s Coverage of the 2000 Summer Olympics,” Mass

Communication and Society 5 (3, 2002): 361-75; Charles A. Tuggle, Suzanne Huffman,

and Dana S. Rosengard, “A Descriptive Analysis of NBC’s Coverage of the 2004 Summer

Olympics,” Journal of Sports Media 2 (1, 2007): 53-75; Charles A. Tuggle and Anne

Owen, “A Descriptive Analysis of NBC’s Coverage of the Centennial Olympics: The

‘Games of the Woman’?” Journal of Sport & Social Issues 23 (2, 1999): 171-83.

36. Angelini, MacArthur, and Billings, “What’s the Gendered Story?”

37. Billings, Olympic Media.

38. Lindsey Meân, “Identity and Discursive Practice: Doing Gender on the Football Pitch,”

Discourse & Society 12 (6, 2001): 789-815.

39. Elaine M. Blinde, Susan L. Greendorfer, and Rebecca J. Shenker, “Differential Media

Coverage of Men’s and Women’s Intercollegiate Basketball: Reflection of Gender

Ideology,” Journal of Sport & Social Issues 15 (2, 1991): 98-114.

40. Angela Burroughs, Liz Ashburn, and Leonie Seebohm, “‘Add Sex and Stir’: Homophobic

Coverage of Women’s Cricket in Australia,” Journal of Sport & Social Issues 19 (3, 1995):

266-84.

41. See, for example, Gerd Von der Lippe, “Media Image Sport, Gender and National Identities

in Five European Countries,” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 37 (3-4,

2002): 371-95.

42. Jennifer Hargreaves, Sporting Females: Critical Issues in the History and Sociology of

Women’s Sports (London: Routledge, 1994).

43. Christy Halbert and Melissa Latimer, “‘Battling’ Gendered Language: An Analysis of

the Language Used by Sports Commentators in a Televised Coed Tennis Competition,”

Sociology of Sport Journal 11 (3, 1994): 298-308.

44. Catriona T. Higgs, Karen H. Weiller, and Scott B. Martin, “Gender Bias in the 1996

Olympic Games: A Comparative Analysis,” Journal of Sport & Social Issues 27 (1, 2003):

52-64.

45. Billings and Angelini, “Packaging the Games for Viewer Consumption.”

46. Pirkko Markula, Olympic Women and the Media: International Perspectives (NY: Palgrave

Macmillan, 2009), 6.

47. Angelini, MacArthur, and Billings, “What’s the Gendered Story?”

48. Billings and Eastman, “Framing Identities.”

49. Billings, Olympic Media; Angelini, MacArthur, and Billings, “What’s the Gendered

Story?”

50. Billings, Angelini, and Duke, “Gendered Profiles of Olympic History.”

51. Billings, Olympic Media.

52. Angelini, MacArthur, and Billings, “What’s the Gendered Story?”

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

Billings et al. 57

53. Angelini, MacArthur, and Billings, “What’s the Gendered Story?” 274.

54. See, for example, Andrew C. Billings, “From Diving Boards to Pole Vaults: Gendered

Athlete Portrayals in the ‘Big Four’ Sports at the 2004 Athens Summer Olympics,”

Southern Communication Journal 72 (4, 2007): 329-44.

55. Billings and Eastman, “Framing Identities.”

56. Jacob Cohen, “A Coefficient for Agreement of Nominal Scales,” Educational and

Psychological Measurement 20 (1, 1960): 37-46.

57. For 1994-2010 data, see Angelini, MacArthur, and Billings, “What’s the Gendered Story?”;

Billings and Angelini, “Packaging the Games for Viewer Consumption”; Billings, Angelini,

and Duke, “Gendered Profiles of Olympic History”; Billings et al., “The Games through

the NBC Lens”; Billings and Eastman, “Framing Identities,” 200; Susan T. Eastman and

Andrew C. Billings, “Gender Parity in the Olympics: Hyping Women Athletes, Favoring

Men Athletes,” Journal of Sport & Social Issues 23 (2, 1999): 140-70.

58. Gitlin, The Whole World Is Watching.

59. Rodger Sherman, “Team USA Medal Count: Women Lead the Way in London,” SBNation.com,

August 13, 2012, http://www.sbnation.com/london-olympics-2012/2012/8/13/3239276/medal-

count-olympics-women-team-usa; “London 2012,” Medal Count—Olympic Medal Standings—

Official Results, http://www.sbnation.com/london-olympics-2012/2012/8/13/3239276/

medal-count-olympics-women-team-usa.

60. Gaye Tuchman, Making News: A Study in the Construction of Reality (NY: The Free Press,

1980).

61. Mary J. Kane, “Media Coverage of the Female Athlete before, during, and after Title IX:

Sports Illustrated Revisited,” Journal of Sport Management 2 (2, 1988): 87-99.

62. Kathleen A. Csizma, Arno F. Wittig, and Terry K. Schurr, “Sport Stereotypes and Gender,”

Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology 10 (1, 1988): 62-74; Nathalie Koivula, “Perceived

Characteristics of Sports Categorized as Gender-Neutral, Feminine and Masculine,”

Journal of Sport Behavior 24 (4, 2001): 377-93.

63. See, for example, Bissell and Duke, “Bump, Set, Spike”; John Clarke, “Despite Protests

and New Bikini Rules, Olympic Beach Volleyball Gets Full Exposure,” Forbes, July 29,

2012, : http://www.forbes.com/sites/johnclarke/2012/07/29/despite-protests-and-new-

bikini-rules-olympic-beach-volleyball-gets-full-exposure/; Laura Williamson, “Beach

Volleyball? It’s Fun and Flesh (and There’s Lots of It!),” MailOnline, July 29, 2012, http://

www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/olympics/article-2180705/London-2012-Olympics-Beach-

volleyball.html#axzz2KRziG2IC.

64. Lyle Brennan, “‘There Are Semi-naked Women Playing Beach Volleyball Glistening Like

Wet Otters’: Boris Johnson (Who Else?) Enthuses about Olympic Event at Horse Guards

Parade,” MailOnline, July 30, 2012, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2181124/

Boris-Johnson-Olympics-There-semi-naked-women-playing-beach-volleyball-glistening-

like-wet-otters.html#ixzz2KX6tXDMG.

65. Davis and Tuggle, “A Gender Analysis of NBC’s Coverage.”

66. See, for example, Angelini, MacArthur, and Billings, “What’s the Gendered Story?”

67. James R. Angelini and Andrew C. Billings, “An Agenda That Sets the Frames: Gender,

Language, and NBC’s Americanized Olympic Telecast,” Journal of Language and Social

Psychology 29 (3, 2010): 363-85.

68. Maxwell E. McCombs and Donald L. Shaw, “The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass

Media,” The Public Opinion Quarterly 36 (2, 1972): 176-87.

69. Bernard C. Cohen, The Press and Foreign Policy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press, 1963).

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

58 Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 91(1)

70. Maxwell McCombs and Amy Reynolds, “How the News Shapes Our Civic Agenda,” in

Media Effects, 3rd ed., ed. Jennings Bryant and Mary B. Oliver (NY: Routledge, 2008),

1-16, 12.

71. Frank D. Durham, “Breaching Powerful Boundaries: A Postmodern Critique of Framing,”

in Framing Public Life, ed. Stephen D. Reese, Oscar H. Gandy, and August E. Grant

(Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2001), 123-35.

72. See, for example, Billings, Olympic Media.

73. James W. Tankard, “The Empirical Approach to the Study of Media Framing,” in Framing

Public Life, ed. Stephen D. Reese, Oscar H. Gandy, and August E. Grant (Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum, 2001), 95-106, 96.

74. See, for example, Angelini, MacArthur, and Billings, “What’s the Gendered Story?”

75. Peter McKay, “Hankies Ready, It’s the Crying Games . . . and Emotions Are Being

Manipulated in the Name of Entertainment,” MailOnline, August 6, 2012, http://www.

dailymail.co.uk/debate/article-2184127/Olympics-2012-Hankies-ready-Crying-Games-.

html#axzz2KPp3aiOq.

76. Eastman and Billings, “Gender Parity in the Olympics.”

77. Eastman and Billings, “Gender Parity in the Olympics.”

78. Tankard, “The Empirical Approach to the Study of Media Framing,” 97.

79. Donald G. Kyle, “‘The Only Woman in All Greece’: Kyniska, Agesilaus, Alcibiades and

Olympia,” Journal of Sport History 30 (2, 2003): 183-204.

80. Alexander Wolff (2012, Aug. 13). Run the world, girls. Sports Illustrated, 40-45, http://

sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1204381/index.htm.

81. Billings, Olympic Media.

82. Nielsen Research, “Women’s World Cup Final Draws 13.5 Million Viewers in U.S.”

Nielsen, http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/newswire/2011/womens-world-cup-final-draws-

13-5-million-viewers-in-us.html.

83. Billings, Olympic Media.

84. Billings, Olympic Media, 72.

Downloaded from jmq.sagepub.com by guest on March 21, 2016

You might also like

- The History and Politics of Sport-For-Development Activists, Ideologues and Reformers by Simon C. Darnell, Russell Field, Bruce KiddDocument338 pagesThe History and Politics of Sport-For-Development Activists, Ideologues and Reformers by Simon C. Darnell, Russell Field, Bruce KiddPhalis MainaNo ratings yet

- Kane Et Al 2013 Exploring Elite Female Athletes Interpretations of Sport Media Images A Window Into The Construction ofDocument30 pagesKane Et Al 2013 Exploring Elite Female Athletes Interpretations of Sport Media Images A Window Into The Construction ofYAHYA ELSOULYNo ratings yet

- No Slam Dunk: Gender, Sport and the Unevenness of Social ChangeFrom EverandNo Slam Dunk: Gender, Sport and the Unevenness of Social ChangeNo ratings yet

- Social Media Highlights Sexism in Olympics CoverageDocument4 pagesSocial Media Highlights Sexism in Olympics CoverageLean AquinoNo ratings yet

- Olympic Legacy DissertationDocument8 pagesOlympic Legacy DissertationBestCustomPapersSingapore100% (1)

- Kicking Center: Gender and the Selling of Women's Professional SoccerFrom EverandKicking Center: Gender and the Selling of Women's Professional SoccerRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- School-Based Assessment in a Caribbean Public ExaminationFrom EverandSchool-Based Assessment in a Caribbean Public ExaminationNo ratings yet

- Sport in the Black Atlantic: Cricket, Canada and the Caribbean diasporaFrom EverandSport in the Black Atlantic: Cricket, Canada and the Caribbean diasporaNo ratings yet

- Gender Inequality in SportsDocument16 pagesGender Inequality in Sportsapi-436368658No ratings yet

- Activism and the Olympics: Dissent at the Games in Vancouver and LondonFrom EverandActivism and the Olympics: Dissent at the Games in Vancouver and LondonNo ratings yet

- Popular Mechanics Why a Curveball Curves: New & Improved Edition: The Incredible Science of SportsFrom EverandPopular Mechanics Why a Curveball Curves: New & Improved Edition: The Incredible Science of SportsNo ratings yet

- Safe Enough?: A History of Nuclear Power and Accident RiskFrom EverandSafe Enough?: A History of Nuclear Power and Accident RiskNo ratings yet

- Sport, Physical Culture, and the Moving Body: Materialisms, Technologies, EcologiesFrom EverandSport, Physical Culture, and the Moving Body: Materialisms, Technologies, EcologiesNo ratings yet

- Discourse Women Sport Less ExcitingDocument18 pagesDiscourse Women Sport Less ExcitingBlythe TomNo ratings yet

- Genero y RIODocument14 pagesGenero y RIOalejandrozuranoclementeNo ratings yet

- Sports Business Unplugged: Leadership Challenges from the World of SportsFrom EverandSports Business Unplugged: Leadership Challenges from the World of SportsNo ratings yet

- (Kevin Young, Kevin Wamsley) Global OlympicsDocument339 pages(Kevin Young, Kevin Wamsley) Global Olympicsnotes.dhmosiografia.authNo ratings yet

- The Palgrave Handbook of Paralympic Studies 1St Edition Ian Brittain Ebook Full ChapterDocument51 pagesThe Palgrave Handbook of Paralympic Studies 1St Edition Ian Brittain Ebook Full Chapterbernard.gross738100% (11)

- Population Dynamics: Proceedings of a Symposium Conducted by the Mathematics Research Center The University of Wisconsin, Madison June 19–21, 1972From EverandPopulation Dynamics: Proceedings of a Symposium Conducted by the Mathematics Research Center The University of Wisconsin, Madison June 19–21, 1972T. N. E. GrevilleNo ratings yet

- Olimpismo: The Olympic Movement in the Making of Latin America and the CaribbeanFrom EverandOlimpismo: The Olympic Movement in the Making of Latin America and the CaribbeanNo ratings yet

- Disrupting Science: Social Movements, American Scientists, and the Politics of the Military, 1945-1975From EverandDisrupting Science: Social Movements, American Scientists, and the Politics of the Military, 1945-1975No ratings yet

- What's the Score?: 25 Years of Teaching Women's Sports HistoryFrom EverandWhat's the Score?: 25 Years of Teaching Women's Sports HistoryNo ratings yet

- The Anthropology of Sport and Human Movement: A Biocultural PerspectiveFrom EverandThe Anthropology of Sport and Human Movement: A Biocultural PerspectiveRobert R. SandsNo ratings yet

- The Impact of The Media On Gender Inequality Within Sport: SciencedirectDocument13 pagesThe Impact of The Media On Gender Inequality Within Sport: Sciencedirecthira khalid kareemNo ratings yet

- 20 Năm Nghiên Cứu Truyền Thông OlympicDocument12 pages20 Năm Nghiên Cứu Truyền Thông OlympicThịnh HuỳnhNo ratings yet

- Overexposed: Capturing A Secret Side of Sports PhotographyDocument15 pagesOverexposed: Capturing A Secret Side of Sports PhotographyMohanad BraziNo ratings yet

- The Topography of Wellness: How Health and Disease Shaped the American LandscapeFrom EverandThe Topography of Wellness: How Health and Disease Shaped the American LandscapeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 18 98Document89 pages18 98Heraa22No ratings yet

- Life Atomic: A History of Radioisotopes in Science and MedicineFrom EverandLife Atomic: A History of Radioisotopes in Science and MedicineNo ratings yet

- Changing the Game: Title IX, Gender, and College AthleticsFrom EverandChanging the Game: Title IX, Gender, and College AthleticsNo ratings yet

- Human Body Composition: Approaches and ApplicationsFrom EverandHuman Body Composition: Approaches and ApplicationsNo ratings yet

- Weedon Et Al. (2016) Where's All The Good Sports JournalismDocument29 pagesWeedon Et Al. (2016) Where's All The Good Sports JournalismRMADVNo ratings yet

- Masculinities, Gender Relations, and SportDocument346 pagesMasculinities, Gender Relations, and SportMordecai HPNo ratings yet

- Journal of Sport History: Book Review Book ReviewsDocument2 pagesJournal of Sport History: Book Review Book Reviewsleishroaster0No ratings yet

- Reclaiming the Game: College Sports and Educational ValuesFrom EverandReclaiming the Game: College Sports and Educational ValuesRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- Time in Television Narrative: Exploring Temporality in Twenty-First-Century ProgrammingFrom EverandTime in Television Narrative: Exploring Temporality in Twenty-First-Century ProgrammingNo ratings yet

- The Invention of Martial Arts Popular Culture Between Asia and America Bowman Full ChapterDocument67 pagesThe Invention of Martial Arts Popular Culture Between Asia and America Bowman Full Chapterrussell.bohannon521100% (19)

- Women Scientists in America: Forging a New World since 1972From EverandWomen Scientists in America: Forging a New World since 1972No ratings yet

- Previewpdf (1) RFFRFRDocument54 pagesPreviewpdf (1) RFFRFRCarlos A. Lima S.No ratings yet

- THE USA VS. THE WORLD - AN ANALYTICAl NARRATIVE OF AMERICAN, WORLD, AND OLYMPIC WEIGHTLIFTING RESULTS, 1970-1992 PDFDocument28 pagesTHE USA VS. THE WORLD - AN ANALYTICAl NARRATIVE OF AMERICAN, WORLD, AND OLYMPIC WEIGHTLIFTING RESULTS, 1970-1992 PDFSean Drew100% (2)

- The Palgrave Handbook of Globalization and Sport Joseph Maguire Ebook Full ChapterDocument51 pagesThe Palgrave Handbook of Globalization and Sport Joseph Maguire Ebook Full Chapterbettye.whilden308100% (11)

- The Digital World of Sport: The Impact of Emerging Media on Sports News, Information and JournalismFrom EverandThe Digital World of Sport: The Impact of Emerging Media on Sports News, Information and JournalismNo ratings yet

- Moving Boarders: Skateboarding and the Changing Landscape of Urban Youth SportsFrom EverandMoving Boarders: Skateboarding and the Changing Landscape of Urban Youth SportsNo ratings yet

- Dose of Jogging and Long-Term Mortality: The Copenhagen City Heart StudyDocument9 pagesDose of Jogging and Long-Term Mortality: The Copenhagen City Heart StudyCharles SeekNo ratings yet

- Representation of Women in The Mountain Biking Media - DissertationDocument49 pagesRepresentation of Women in The Mountain Biking Media - Dissertationlauren1224No ratings yet

- More than Cricket and Football: International Sport and the Challenge of CelebrityFrom EverandMore than Cricket and Football: International Sport and the Challenge of CelebrityNo ratings yet

- Discipline and Indulgence: College Football, Media, and the American Way of Life during the Cold WarFrom EverandDiscipline and Indulgence: College Football, Media, and the American Way of Life during the Cold WarNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument2 pagesContent Serversyed tanveerNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument10 pagesContent Serversyed tanveerNo ratings yet

- Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly-2014-Beam-59-77Document19 pagesJournalism & Mass Communication Quarterly-2014-Beam-59-77syed tanveerNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument2 pagesContent Serversyed tanveerNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2211695815000021 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S2211695815000021 Mainsyed tanveerNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2211695815000045 MainDocument2 pages1 s2.0 S2211695815000045 Mainsyed tanveerNo ratings yet

- Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 2014 Yanich 159 76Document18 pagesJournalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 2014 Yanich 159 76syed tanveerNo ratings yet

- Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 2014 Kim 139 58Document20 pagesJournalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 2014 Kim 139 58syed tanveerNo ratings yet

- Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 2014 Watson 5 16Document12 pagesJournalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 2014 Watson 5 16syed tanveerNo ratings yet

- Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 2014 Denham 17 37Document21 pagesJournalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 2014 Denham 17 37syed tanveerNo ratings yet

- Medication Instructions Prior To SurgeryDocument11 pagesMedication Instructions Prior To Surgeryhohj100% (1)

- Kosem SultanDocument2 pagesKosem SultanAmaliaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Financial Management: Topic 1Document85 pagesIntroduction To Financial Management: Topic 1靳雪娇No ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document13 pagesChapter 1Jerard AnciroNo ratings yet

- The Holy See: Benedict XviDocument4 pagesThe Holy See: Benedict XviAbel AtwiineNo ratings yet

- Liquid Holdup in Large-Diameter Horizontal Multiphase PipelinesDocument8 pagesLiquid Holdup in Large-Diameter Horizontal Multiphase PipelinessaifoaNo ratings yet

- Bottoms y Sparks - Legitimacy - and - Imprisonment - Revisited PDFDocument29 pagesBottoms y Sparks - Legitimacy - and - Imprisonment - Revisited PDFrossana gaunaNo ratings yet

- Sampling Strategies For Heterogeneous WastesDocument18 pagesSampling Strategies For Heterogeneous Wastesmohammed karasnehNo ratings yet