Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Special Education Teacher Preparation in

Uploaded by

ximena oyarzoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Special Education Teacher Preparation in

Uploaded by

ximena oyarzoCopyright:

Available Formats

Special Education Teacher Preparation in Classroom

Management: Implications for Students With Emotional

and Behavioral Disorders

Regina M. Oliver and Daniel J. Reschly

Peabody College of Vanderbilt University

ABSTRACT: Special education teachers’ skills with classroom organization and behavior

management affect the emergence and persistence of behavior problems as well as the success of

inclusive practice for students with emotional and behavioral disorders (EBD). Adequate special

education teacher preparation and strong classroom organization and behavior management skills

are critical for teachers of students with EBD. Little research has been conducted to determine the

extent to which special education teacher preparation programs provide teachers with adequate

instruction on classroom organization and behavior management techniques. Course syllabi from 26

special education teacher preparation programs were reviewed. Results indicate a highly variable

emphasis on classroom organization and management between programs. Programs tended to

emphasize reactive procedures. Only 27% (n 5 7) of the university programs had an entire course

devoted to classroom management. The remaining 73% (n 5 19) of university programs had content

related to behavior management dispersed within various courses. Limitations and implications for

special education teacher preparation and inclusive practices are discussed.

& The education of students with emotional 2008). Children who perform low academi-

and behavioral disorders (EBD) continues to be cally are at greater risk for behavioral problems

a great challenge, due in large part to the because inappropriate behavior typically re-

complex nature of the disorder (Reddy & sults in escape from difficult academic tasks. A

Richardson, 2006; Reid, Gonzalez, Nordness, cycle of negative reinforcement is created for

Trout, & Epstein, 2004). Children and adoles- both the teacher and the student in which the

cents with EBD exhibit a range of chronic student is reinforced because the demand has

problems that interfere with learning that been removed and the teacher is reinforced

include both externalizing behaviors (e.g., because the student and disruptive behavior

classroom disruptions, aggression) and inter- have been removed from the classroom. In

nalizing behavior (e.g., anxiety, social with- fact, children with behavioral problems have

drawal; Kaufman, 2005). Academic deficits been shown to receive fewer instructional

are also pervasive for students with EBD. In a opportunities (Gunter, Denny, Jack, Shores, &

meta-analysis of the academic abilities of Nelson, 1993). Because of the behavioral

students with special needs, Reid and col- excesses exhibited by students with EBD,

leagues (2004) found that students with EBD teacher skills in classroom organization and

had significant deficits in academic achieve- behavior management are necessary to ad-

ment across academic subjects and settings. dress these challenging behaviors, attenuate

Although it is unclear whether academic academic deficits, and support successful

difficulties precede behavioral problems or if inclusion efforts.

behavioral issues create academic difficulties, Teachers often find it more challenging to

researchers currently believe that there is a meet the instructional demands of the class-

reciprocal influence of both (Kauffman, 2005; room without the expertise and competency to

Sutherland, Lewis-Palmer, Stichter, & Morgan, address disruptive student behavior (Emmer &

188 / May 2010 Behavioral Disorders, 35 (3), 188–199

Stough, 2001). Poor classroom management numbers of students with significant behavior

typically leads to less instruction and worse problems are integrated into the general

student outcomes (Cameron, Connor, Morrison, education environment due to the highly

& Jewkes, 2008; Tooke, 1997). In fact, a study qualified teacher provisions and inclusive

by Espin and Yell (1994) examined teacher practices mandates of No Child Left Behind

behavior and categorized teachers as effective (Reschly, Smartt, Oliver, & Holdheide, 2007).

or ineffective based on their observations. The Special education teachers play a critical role

authors identified an inability to manage the in the successful inclusion of these students in

classroom environment with corresponding three ways. First, special education teachers

high rates of discipline problems and low rates can work with general education teachers on

of teacher responses to those problems as the establishing effective classroom management

main reasons teachers were rated as ineffective plans to prevent the worsening of behavioral

(Espin & Yell, 1994). Unfortunately, students problems for students at risk for EBD. Second,

with EBD are at higher risk for not receiving special education teachers can provide a

adequate instruction due to the disruptive supportive behavioral environment for stu-

behaviors typically exhibited by these students dents already in self-contained settings to

(Gunter et al., 1993). Well-designed and imple- teach important prosocial behavior and skills

mented classroom management systems might necessary to function in general education

allow teachers the opportunity to increase settings. Finally, special educators are increas-

instruction for students with EBD. ingly taking the role of co-teachers to support

Beyond the issue of adequate instructional the successful inclusion of students with

opportunities, early intervention and treatment significant behavior concerns.

for students with EBD are essential to prevent

more serious maladaptive behaviors (Greer-

Chase, Rhodes, & Kellam, 2002; Kauffman,

Teacher Preparation

2005). The progression and malleability of Inadequate general and special education

maladaptive behaviors are affected by class- teacher preparation hinders inclusion efforts.

room management practices of teachers in the Specifically, the inclusion of students with

early grades. Aggressive students in aggressive, challenging behavior or EBD in regular educa-

disruptive classroom environments are more tion classrooms is affected by teachers’ abilities

likely to be aggressive in later grades (Greer- to handle the disruptive behaviors typically

Chase et al., 2002; Kellam, Ling, Merisca, exhibited by these students (Gunter et al.,

Hendricks Brown, & Ialongo, 1998; Kellam, 1993). General education teachers who feel

Mayer, Rebok, & Hawkins, 1998). The long- inadequately prepared to effectively manage

term effect of classroom management practices classrooms, or who report a low ability to

on aggressive student behavior was examined address challenging behaviors, are also (a) less

in a randomized controlled study conducted in willing to implement individualized behavior

a large urban school district (Greer-Chase et support plans and reinforcement strategies, (b)

al., 2002; Kellam, Ling, et al., 1998; Kellam, vary reinforcement schedules, and (c) docu-

Mayer, et al., 1998). A relatively simple ment student progress for systematic evaluation

procedure, the Good Behavior Game (Barrish, (Baker, 2005). Consequently, behavior support

Saunders, & Wolf, 1969), was taught to plans designed to ameliorate the challenging

teachers in one afternoon of continuing behaviors exhibited by students with EBD in

education with a half-day follow-up a few general education settings often fail, leading to

months later. Rates of disruptive and aggres- placement in more segregated settings. Special

sive behaviors declined significantly in the educators can support general education teach-

experimental classrooms while student en- ers with effective classroom management plans

gagement increased, and the decreased rates and behavior management skills to provide

of aggressive behaviors for boys persisted adequate behavior support for students with

through sixth grade. This research highlights challenging behaviors in general education

the importance of effective classroom man- settings, thus reducing the amount of time

agement practices and the need for teachers to students are placed in self-contained settings.

be adequately prepared in this area. Adequate special education teacher prep-

Adequate preparation in effective class- aration and strong classroom organization and

room management is increasingly necessary behavior management skills are critical for

for special education teachers as greater students with EBD who spend most of their

Behavioral Disorders, 35 (3), 188–199 May 2010 / 189

time in segregated settings (Landrum, Tankers- praise; (d) provided quick, prompt responses

ley, & Kauffman, 2003; Oliver & Reschly, to inappropriate behavior before behaviors

2007). Special education teachers are respon- escalated; and (e) were consistent with conse-

sible for teaching students adequate behavior- quences to both appropriate and inappropriate

al, social, and academic skills to be successful behavior.

in inclusive settings. However, research indi- Experimental studies have also examined

cates that teachers of students with EBD may classroom management approaches as a col-

not be adequately prepared, have less experi- lection of specific components. Reductions in

ence, and receive less education (Billingsley, disruptive behavior have been found with

Fall, & Williams, 2006; Katsiyannis, Zhang, & packaged interventions using antecedent strat-

Conroy, 2003). In a national longitudinal egies (e.g., posting of rules, teacher movement,

survey regarding the education of students precision requests), reinforcement strategies

with emotional disturbance, only 25% to 33% (e.g., token economy, mystery motivator),

of students in the sample had teachers who and consequence strategies to respond to

reported receiving at least 8 hr of in-service inappropriate behavior (e.g., response cost;

training regarding issues related to working Di Martini-Scully, Bray, & Kehle, 2000; Kehle,

with students with disabilities (Wagner, Friend, Bray, Theodore, Jenson, & Clark, 2000). This

Bursuck, Kutash, Duchnowski, et al., 2006). classroom management package of strategies

Moreover, only 22.9%, 30%, and 13.1% of has also been used to decrease disruptive

elementary, middle, and high school general behavior for students with EBD (Musser, Bray,

education teachers, respectively, strongly Kehle, & Jenson, 2001).

agreed that they had been given adequate In their review of the research on class-

training (Wagner, Friend, et al., 2006). Based room management, Emmer and Stough (2001)

on these data, it appears that many classroom found that teachers who effectively managed

teachers, in regular and special education their classrooms focused on prevention rather

classrooms, believe they are insufficiently than reactive approaches and explicitly taught

prepared to handle challenging behavior. This desirable student behaviors. Preventive class-

has implications for policy makers and teacher room management practices consist of (a)

preparation programs alike because of the structuring the physical environment to ac-

legal requirements regarding inclusion in the commodate traffic patterns and minimize

least restrictive educational environment and distractions as well as structuring instructional

access to the general education curriculum. time and transitions, (b) establishing a few

positively stated behavioral expectations that

Classroom Management Practices are linked to the schoolwide plan, (c) identi-

fying rules that provide behavioral examples of

The various components of typical class- the expectations, (d) establishing routines for

room management approaches have been classroom tasks such as turning in homework,

documented in the literature through observa- (e) planning to actively teach the rules and

tion studies of effective teachers and experi- routines, (f) establishing procedures to rein-

mental studies, although very few experimen- force appropriate behavior, (g) using effective

tal control studies have examined classroom procedures to reduce and respond to inappro-

management specifically (Oliver, 2009). Early priate behavior, and (h) collecting data to

studies collecting observational data on effec- monitor student behavior and modify the

tive teachers found specific practices that classroom management plan as needed (Em-

established effective classroom management. mer & Stough, 2001; Kerr & Nelson, 2002;

In a series of studies, Anderson and colleagues Lewis & Sugai, 1999; Martella, Nelson, &

(Anderson & Evertson, 1978; Anderson, Ev- Marchand-Martella, 2003).

ertson, & Emmer, 1979) identified five factors One systematic best evidence review was

that were associated with better classroom conducted to identify evidence-based practic-

managers. Teachers were identified as effec- es in classroom management in an attempt to

tive classroom managers if they (a) had clear inform research and practice (Simonsen, Fair-

expectations about behavior and communicat- banks, Briesch, Myers, & Sugai, 2008). Re-

ed them clearly; (b) explicitly taught classroom searchers in this study initially reviewed 10

rules and routines using examples and non- classroom management texts to identify typical

examples; (c) acknowledged students for ap- topics described within texts and systematical-

propriate behavior using behavior-specific ly searched to identify experimental studies

190 / May 2010 Behavioral Disorders, 35 (3), 188–199

that addressed these topics. The researchers education (IHEs) that included both academic

used criteria for evidence-based similar to the and behavior. For the purposes of this study,

What Works Clearinghouse criteria to evaluate only classroom management data are reported.

the evidence of each practice (Simonsen et al., The sample of course syllabi was obtained

2008). Results of the evaluation of 81 studies from a large Midwestern state. The state

identified 20 general practices that met the recently updated its special education licen-

criteria for evidence based. These 20 general sure requirements by removing specific en-

practices fell into five broad categories: (a) dorsements for licensure (e.g., Learning Dis-

maximize structure and predictability; (b) post, abilities, LD, Seriously Emotionally Disturbed,

teach, review, and provide feedback on SED) and moving to a cross-categorical license

expectations; (c) actively engage students in in an effort to improve integration of students

observable ways; (d) use a continuum of with disabilities in the general education

strategies to acknowledge appropriate behav- curriculum. Based on the state board of

ior; and (e) use a continuum of strategies to education’s desire to evaluate all special

respond to inappropriate behavior (Simonsen education teacher preparation programs across

et al., 2008). A range of two to six practices the state, permission and authority to solicit

were classified under each broad category, course syllabi were obtained from the state

and the empirical studies supporting each board of education. A letter from the state

practice ranged from three to eight studies associate superintendent and director of spe-

per practice. ‘‘Responding to inappropriate cial education was then sent to the deans of

behavior’’ had the highest amount of empirical the College of Education at all 31 public and

studies, whereas ‘‘maximizing structure and private IHEs. These 31 IHEs comprised the

predictability’’ had the fewest (Simonsen et al., entire population of special education teacher

2008). Logically, teachers should receive preparation programs located in the state. The

adequate training on these skills prior to their IHEs represented in the sample were a mixture

first day of teaching. However, to date, little of public and private universities, including

research has been conducted to determine to large R1 universities. Each dean was asked to

what extent special education teacher prepa- submit a copy of each course syllabus that was

ration programs provide instruction and super- required as part of the licensing requirement

vised practice in these areas. for special education teacher certification at

The purpose of the current study was to their IHE. If necessary, a follow-up letter was

examine special education teacher preparation sent encouraging submission of course syllabi

in classroom organization and behavior man- followed by additional reminder e-mails.

agement. A review of course syllabi from 26 Course syllabi from 26 IHEs were ob-

special education teacher preparation programs tained, for an overall response rate of 83.9%.

was conducted to determine if the critical Each course syllabus was reviewed for content

features of classroom organization and behav- related to classroom management. If a sylla-

ior management were included in their courses bus had any content that could be rated on the

of study. An Innovation Configuration (IC) map measurement instrument used in this study, it

(Hall & Hord, 2001) was developed based on a was included in the sample. The rationale for

review of the classroom management literature rating any course containing content that

and applied to course syllabi to answer the could be scored on the IC was based on the

following questions: (a) Do special education fact that not every IHE had an entire course

teacher preparation programs provide adequate devoted to classroom management but rather

training in classroom organization and behavior

content dispersed throughout courses. A sample

management? and (b) Which components of

of 135 course syllabi was identified and used for

classroom organization and behavior manage-

this review. Syllabi were identified as either

ment are taught more intensely in special

courses on classroom management (n 5 7) or

education teacher preparation?

courses containing content related to classroom

organization and behavior management (n 5

Method 128). This sample included courses specific to

individualized behavior management. Syllabi

Sample that did not contain content related to classroom

organization or behavior management were

Data collected for this study were part of a excluded from this review (e.g., a course

larger evaluation of institutions of higher syllabus related only to reading).

Behavioral Disorders, 35 (3), 188–199 May 2010 / 191

Measurement with descriptors and examples to guide appli-

cation of the criteria to course syllabi. For

Course syllabi review was used as the instance, under the essential component Ac-

primary data collection method for two pri- tive Supervision and Student Engagement were

mary reasons. First, course syllabi are used the examples teacher scans, moves in unpre-

widely as important indicators of program dictable ways, and monitors student behavior;

quality in accreditation, teacher licensing, teacher uses more positive to negative teacher-

and research (Steiner & Rozen, 2004; Walsh, student interactions; teacher provides high

Glaser, Wilcox, 2006). Second, course syllabi rates of opportunities for students to respond;

are almost always prepared in higher educa- and teacher uses multiple observable ways to

tion coursework, easily accessed, and an engage students (e.g., response cards, peer

efficient reflection of course content and tutoring). The content validity of the classroom

experiences. Although course syllabi may not organization and behavior management rubric

contain all information related to actual is based on a review of research and practice

content and experiences, it is a relatively (e.g., Simonsen et al., 2008). The essential

strong indicator of the scope and sequence of components developed were (a) structured

a university course. environment, (b) active supervision and stu-

dent engagement, (c) schoolwide behavioral

Instrument expectations, (d) classroom rules, (e) classroom

routines, (f) encouragement of appropriate

The authors developed a rubric based on behavior, and (g) behavior reduction strategies.

the format of an IC (Hall & Hord, 2001) to

Bulleted items accompanied each component

measure the degree to which the essential

to provide further detail regarding the definition

components of classroom management are

of each component (e.g., group contingencies).

represented in coursework required for certifi-

The second dimension used in the rubric

cation. Innovation Configurations have been

was the degree of implementation. In the top

used for at least 30 years in the development

row, several levels of implementation were

and implementation of educational innova-

defined, ranging from the lowest level of

tions (Hall & Hord, 2001; Hall, Loucks,

implementation to the highest level. Increasing

Rutherford, & Newton, 1975; Hord, Ruther-

levels of implementation were assigned pro-

ford, Huling-Austin, & Hall, 1987; Roy &

gressively higher scores from 0 to 4. Each level

Hord, 2004). These tools were originally

developed by experts in a national research required evidence of implementation from

center studying educational change and are lower levels plus requirements for that level.

used in the Concerns Based Adoption Model Descriptors used were (0) no evidence that the

(Hall & Hord, 2001) as a professional devel- component is included in the course syllabi, (1)

opment tool. They have also been used for syllabi mentioned the component, (2) required

program evaluation (Roy & Hord, 2004). readings and tests and/or quizzes, (3) required

An IC identifies and describes the major assignments or projects for application and

components of a practice or innovation. With finally the highest level of implementation,

ICs, innovations are assessed along a contin- and (4) teaching application with feedback.

uum of configurations, ranging from nonuse to Scores to represent different levels of

ideal implementation practice. An instrument implementation were created on an ordinal

parallel to an IC was developed to describe the scale in which a higher score indicated a more

range of implementation of teacher prepara- thorough implementation of an IC component.

tion coursework related to classroom organi- These scale points cannot, however, be

zation and behavior management at various interpreted as if the intervals between the

levels of implementation. In this case, imple- scores are equal. That is, the difference

mentation refers to whether the critical com- between 1 and 2 cannot be assumed to be

ponents are being taught with supervised the same amount as the difference between 3

experience as evidenced by course syllabi. and 4. Furthermore, a score of 4 indicates more

The classroom organization and manage- thorough implementation than a score of 2, but

ment rubric was constructed in a table listing it cannot be interpreted as twice as much of

essential components and degree of imple- some quality as a score of 2. A copy of the

mentation. Essential components of classroom Classroom Organization and Behavior Manage-

organization and behavior management were ment IC (Oliver & Reschly, 2007) can be

listed in the rows of the far left column, along obtained from the primary author upon request.

192 / May 2010 Behavioral Disorders, 35 (3), 188–199

Course Syllabi Rating ments, were determined for reliability by the

following formula:

Researchers were trained on the use of the

IC over a 2-week period of time. The research Total IC components exact points

assistant had 11 years of experience in the field Total IC components exact pointszmisses

of education working for a state department of |100%

education. The first author was a doctoral

student in special education at the time of the Exact agreements occurred when both

study with 6 years of experience in education raters awarded the same number of points for

as well as the primary developer of the IC. a specific IC component. The exact agree-

Prior to the syllabi review, two raters indepen- ments were totaled for each IC component and

dently scored a small sample of course syllabi placed in the numerator of the above formula.

and discussed the scoring criteria until 100% The exact agreements plus the misses were

agreement was reached. Once researchers totaled and entered as the denominator.

were trained, the IC was used to rate each Adjacent number agreements were also

course syllabus related to classroom organiza- studied. An adjacent number agreement oc-

tion and behavior management. curred if the two raters independently rated an

Each course syllabus from all universities IC component within 1 point. For example, on

was rated for each component of the IC; the classroom rules component of the IC, an

however, the analysis of the results was at adjacent number agreement occurred if the

the university syllabi level rather than individ- two independent ratings were within 1 point of

ual course level. Therefore, a final score on each other. In a second analysis, adjacent

each IC component was given to each agreements were totaled and entered in the

university based on the highest rating that numerator. In the second analysis, the denom-

was obtained. For example, a university might inator was composed of the adjacent agree-

have several courses related to behavior, and ments plus the misses (2 or more points apart).

each syllabus was rated on the IC component Exact agreement and adjacent agreement

‘‘structured environment.’’ Individual course reliability results were 86% and 97%, respec-

syllabus scores may have ranged from 0 to 3, tively. These reliability scores are sufficient for

but the university would receive a final score the purposes of this research.

of 3 for that IC component based on the

highest individual course syllabus score re-

ceived. Results are reported at the university Results

level of analysis. The rationale for a university-

level score relates to the unit of analysis in the The syllabi scores on the classroom

research question. That is, the state department organization and behavior management IC

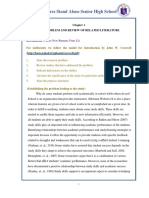

of education and the researchers desired to were highly variable (see Table 1). Only 27%

evaluate each IHE in terms of how they were (n 5 7) of the university special education

preparing individuals enrolled in special edu- programs had an entire course devoted to

cation teacher preparation programs on class- classroom management. The remaining 73%

room management content and supervised (n 5 19) of university programs had content

practice. If the purpose of the study had been related to behavior management dispersed

to develop improvement plans for IHEs, a within various courses or had courses specific

within-university analysis would have been a to individual behavior management interven-

more appropriate analysis. tions. The highest component ratings obtained

were for the behavior reduction strategies

Interrater Reliability component, in which 96% (n 5 25) of the

university programs received scores of either 3

From the total 135 course syllabi that (thorough coverage in class) or 4 (teaching

covered classroom management, 25% (n 5 application with feedback). Second to behav-

31) were randomly selected by researchers to ior reduction strategies, 58% (n 5 15) of

be evaluated for interrater reliability. Two university programs scored either 3 or 4 on

raters independently scored the same syllabi the IC component for encouragement of

at separate points in time. The secondary rater appropriate behavior. A breakdown of each

scored the syllabi in the opposite order as the IC component by the percentage of universi-

primary rater to control for observer drift. Two ties scoring 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 is provided in

methods, exact agreement and adjacent agree- Figure 1.

Behavioral Disorders, 35 (3), 188–199 May 2010 / 193

TABLE 1

Percentages of 26 University Programs Meeting Classroom Management Essential Components

IC Component 0 1 2 3 4

Structured environment 54 8 8 19 12

Active supervision and student engagement 65 12 8 4 12

Schoolwide behavioral expectations 62 4 15 8 12

Classroom rules 42 0 19 27 12

Classroom routines 50 8 0 23 19

Encouragement of appropriate behavior 19 12 12 31 27

Behavior reduction strategies 0 0 4 31 65

Note. Values are rounded percentages of universities scoring at each Innovation Configuration (IC) level. 0 5 no evidence, 1 5

syllabi mentioned component, 2 5 required readings and/or test and/or quizzes, 3 5 required assignments or projects for

application, 4 5 teaching application with feedback.

Results indicated that universities provided The emphasis on behavior reduction

less preparation in other components of the IC, strategies and encouragement of appropriate

particularly structured environment, active behavior found in the course syllabi reviewed

supervision and student engagement, school- may very likely meet significant needs of many

wide behavioral expectations, and classroom students with EBD in inclusive settings. Scores

routines. More than half of the universities’ indicate that special education teacher prepa-

scores indicated no evidence of these compo- ration programs are providing content on

nents in their course syllabi. Surprisingly, the reactive, behavior reduction procedures and

classroom rules component of the IC was some supervised experience. However, further

notably underrepresented in course syllabi as emphasis on preventive strategies such as

well; more than 42% (n 5 11) of university schoolwide positive behavior supports and

programs had no courses in which the topic of classroom rules and routines likely would

establishing classroom rules was mentioned in enhance successful integration of students with

any syllabus. Considering the fundamental EBD by teaching appropriate behavior and

importance of preventive strategies such as preventing disruptive behavior. Coursework

establishing behavioral expectations and rules, should contain content in these areas as well

these results are sources of significant concern. as supervised experience.

Figuer 1. Percentages of 26 University Programs Scoring 0 to 4 for Each IC Component.

194 / May 2010 Behavioral Disorders, 35 (3), 188–199

Discussion prepared to meet the behavioral needs of

diverse learners. The most surprising result in

Effective classroom organization and be- this study, however, was that only 7 of the 26

havior management are essential skills for any universities had an entire course devoted to

teacher, particularly teachers of students with classroom management. The majority of IHEs

EBD and other behavioral challenges (Gunter in this sample provided some level of class-

& Denny, 1996). In general, observations in room organization and behavior management

applied, special education classroom settings throughout coursework, although the level of

indicate poor classroom practices occurring detail and quantity varied.

and a lack of teacher skills in establishing Whether a concentrated course with su-

environments that support the needs of stu- pervised practice is a superior training ap-

dents with behavioral challenges (Gunter et proach to interspersing classroom manage-

al., 1993). The purpose of the current study ment content throughout a number of courses

was to examine one state’s preparation of is unknown. Although it is unclear what

special education teachers in the area of method of teaching classroom management

classroom management to establish if this lack strategies provides adequate teacher prepara-

of observed effective classroom procedures is tion for implementation and maintenance, it is

related to teacher preparation in the area of interesting to note that other instructional

classroom management. Previous research on topics (e.g., reading) often have at least one

classroom management indicates that effective course devoted to the topic in preservice

managers use preventive procedures such as teacher preparation (Smartt & Reschly, 2007).

clear and consistent classroom rules and Which approach is most effective for teaching

routines, structured environment, and active classroom management strategies is probably

supervision and student engagement (Ander- an empirical question. What is clear is that in

son & Evertson, 1978; Espin & Yell, 1994; comparison with other preservice content, the

Simonsen et al., 2008). coverage of classroom management practices

To determine the level of preparation for seems woefully inadequate. If these results

special educators, an IC was developed and from one large state are indicative of special

used to evaluate course syllabi to determine education teacher preparation across the

the extent of classroom management content country in general, much needs to be done

and supervised practice represented in course- to provide special education teachers with

work required for special education teacher classroom management knowledge and skills

licensure. Course syllabi were rated based on necessary to establish contexts that support the

the degree of implementation of essential academic and behavioral needs of all students

classroom management components from no with behavioral challenges.

evidence to the highest level of implementa-

tion including supervised practice. The results Recommendations for Future Research

suggest a conspicuous absence of comprehen-

sive, classroom management procedures in One area of future research is the exam-

course syllabi. More specifically, the majority ination of preventive classroom management

of attention in course syllabi was placed on strategies for special education teachers. Al-

reactive procedures to reduce inappropriate though there has been significant observation-

behavior with little attention given to preven- al research on effective classroom manage-

tion strategies. These findings mirror field ment and single-subject research on individ-

observations in which primary classroom ualized strategies for changing behavior,

management has placed a heavy reliance on there does not appear to be research-based

punitive, reactive procedures (Shores, Gunter, consensus in the field regarding what needs to

& Jack, 1993). be taught for universal classroom management

Given the role of disordered behavior in procedures (Oliver, 2009). More research has

identifying students for special education, one been done and more is known about the use of

would expect that special educators would individualized approaches for students with

have a higher degree of preparation and behavioral concerns, for example, functional

training on classroom organization and behav- behavioral assessments. Future research should

ior management. The results from the sample experimentally examine universal classroom

of universities in this study suggest special management approaches to establish what

education teachers may not be adequately practices are necessary to provide the maxi-

Behavioral Disorders, 35 (3), 188–199 May 2010 / 195

mum benefit and therefore what should be barriers to the inclusion of students with EBD

taught in special education teacher preparation and other disabilities in general education

programs. settings. Teachers who are insufficiently pre-

Another area for future research is to pared in preventive classroom management

determine the appropriate approach for pre- practices may lean toward the use of more

paring preservice teachers to be highly skilled reactive procedures. The use of reactive

and fluent with classroom organization and procedures such as time-out and removal from

behavior management principles prior to their the classroom excludes students from general

first day of teaching. Research should deter- education and access to the general education

mine whether classroom organization and curriculum. Moreover, students may be placed

behavior management are taught most effec- in more restrictive settings due to insufficient

tively in sections throughout the curriculum, in management in the regular education class-

one concentrated course, or a combination of room. Special education teachers who are

the two. Teacher reports (Baker, 2005; Siebert, inadequately prepared hinder inclusion efforts

2005) indicate inadequate preparation in the because students with EBD do not learn the

area, but what is not known is the appropriate skills necessary to be successful in general

amount of content knowledge, practice, and education settings.

support that is optimal to prepare teachers to Second, inadequate teacher preparation

address the behavioral challenges of today’s may also act as a barrier to the prevention of

classrooms. A greater understanding of how to behavioral disorders. Young children with

adequately prepare teachers will likely ame- aggressive, disruptive behaviors, particularly

liorate some of the issues around teacher boys, will remain disruptive and aggressive in

retention and persistence in the field. later grades without preventive classroom

Future research should also investigate management procedures (Greer-Chase et al.,

the preparation of general education teachers 2002; Kellam, Ling, et al., 1998; Kellam,

in classroom organization and behavior man- Mayer, et al., 1998; van Lier, Muthen, van

agement and how this training intersects with der Sar & Grijnen, 2004). Effective classroom

or parallels what special educators are being organization and behavior management can

taught. Prevention of more serious behavior prevent the progression of maladaptive behav-

concerns begins in the early grades when iors that place children at risk for EBD.

students are still involved and participating in Insufficient teacher preparation in classroom

general education. Therefore, general educa- management is a barrier to the prevention of

tion teachers play a significant role in these behavioral disorders.

preventive efforts, and special education Finally, inadequate teacher preparation

teachers have the opportunity to work with hinders successful early intervention and

general education teachers in these efforts. response-to-intervention (RTI) efforts in gen-

Special education teachers who take part in eral education. Inclusive in the conceptuali-

prereferral teams can identify weaknesses in zation of a three-tier system of support is the

universal classroom management in the gen- assumption of strong core programs at Tier I,

eral education context, thereby preventing including classroom organization and behav-

improperly diagnosed students as behavioral ior management. If classroom behavior is

disordered. A greater understanding of wheth- ineffectively managed, indicating a weak

er general and special educators are being core program, it is more likely that larger

trained with prevention of behavioral disor- percentages of students will be identified

ders as a focus of universal classroom inaccurately and referred for additional sup-

management procedures is necessary to en- port. Moreover, the success of Tier II inter-

hance prevention efforts and inclusive prac- ventions will likely be hindered by poorly

tices. managed classroom environments that in-

clude high rates of off-task behavior and less

Implications for Inclusive Practices and instructional time. Effective classroom man-

Special Education Teacher Preparation agement is an essential part of successful

early intervention and RTI systems of support.

Inadequate special education teacher Comprehensive teacher preparation in all

preparation in classroom organization and components of classroom organization and

behavior management presents several signif- behavior management therefore is required at

icant barriers. These results indicate possible the preservice level.

196 / May 2010 Behavioral Disorders, 35 (3), 188–199

Limitations dicates both inadequate preservice teacher

preparation and potential barriers to inclusive

There are several limitations to these educational practices. This has implications for

findings. First, the content validity of the school leadership and teacher preparation

components of the classroom organization programs alike.

and behavior management IC used to rate

course syllabi has not been directly validated

through research with the IC but rather is REFERENCES

Anderson, L. M., & Evertson, C. M. (1978). Class-

based on other supporting research of each

room organization at the beginning of school:

component. A second limitation is what Two case studies. Austin, TX: Research and

information can be obtained about special Development Center for Teacher Education.

education teacher preparation from a review (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No.

of course syllabi alone. Course syllabi are a ED166193)

valid representation of what is taught in Anderson, L. M., Evertson, C. M., & Emmer, E. T.

teacher preparation programs only to the (1979). Dimensions in classroom management

extent that the syllabi information is accurate derived from recent research. Austin, TX:

and the content, learning activities, and Research and Development Center for Teacher

Education. (ERIC Document Reproduction Ser-

experiences are actually implemented in the

vice No. ED166193)

course as described. Third, although the large

Baker, P. H. (2005). Managing student behavior:

percentage of programs participating in this How ready are teachers to meet the challenge?

research represents a large proportion in the American Secondary Education, 33, 51–64.

state, the generalizability of these results is Barrish, H., Saunders, M., & Wolf, M. (1969). Good

limited to the IHEs with special education behavior game: Effects of individual contingen-

teacher preparation programs participating in cies for group consequences on disruptive

this evaluation and the degree to which the behavior in a classroom. Journal of Applied

syllabi submitted were the actual syllabi used Behavior Analysis, 2, 119–124.

in courses. Finally, the course syllabi re- Billingsley, B. S., Fall, A. M., & Williams, T. O.

(2006). Who is teaching students with emotional

viewed were only for required courses for

and behavioral disorders? A profile and com-

the special education license, so it is unclear parison to other special educators. Behavioral

how well classroom organization and behav- Disorders, 31, 252–264.

ior management components are implement- Cameron, C. E., Connor, C. M., Morrison, F. J., &

ed in the preparation of general education Jewkes, A. M. (2008). Effects of classroom

teachers. Although it appeared that many organization on letter-word reading in first grade.

courses were required in both general educa- Journal of School Psychology, 46, 173–192.

tion and special education requirements, Di Martini-Scully, D., Bray, M. A., & Kehle, T. J.

required courses for general education were (2000). A packaged intervention to reduce

not studied directly. disruptive behaviors in general education stu-

dents. Psychology in the Schools, 37, 149–156.

Elementary and Secondary Education Act (No Child

Left Behind) of 2002, Pub. L. No. 107, 115 Stat.

Conclusion 14 (2002).

Emmer, E. T., & Stough, L. M. (2001). Classroom

As schools struggle to meet significant

management: A critical part of educational

requirements of inclusive practices for students

psychology, with implications for teacher edu-

with EBD and the educational and behavioral cation. Educational Psychologist, 36, 103–112.

needs of all students, the adequate preservice Espin, C. A., & Yell, M. L. (1994). Critical indicators

preparation of teachers becomes critical. of effective teaching for preservice teachers:

Federal law embraces teacher quality as a Relationships between teaching behaviors and

critical factor in improving achievement, ratings of effectiveness. Teacher Education and

prevention of learning and behavioral disor- Special Education, 17, 154–169.

ders, and attaining broad outcomes such as Greer-Chase, M., Rhodes, W. A., & Kellam, S. G.

school completion and positive early adult (2002). Why the prevention of aggressive

disruptive behaviors in middle school must

participation in education and careers (Ele-

begin in elementary school. The Clearing

mentary and Secondary Education Act, 2002; House, 5, 242–245.

IDEA Individuals with Disabilities Education Gunter, P., & Denny, R. (1996). Research issues and

Act, 2004, 2006). Examination of special needs regarding teacher use of classroom

education teacher preparation programs in management strategies. Behavioral Disorders,

classroom organization and management in- 22, 15–20.

Behavioral Disorders, 35 (3), 188–199 May 2010 / 197

Gunter, P. L., Denny, R. K., Jack, S. L., Shores, R. E., individualized social learning approach. Boston,

& Nelson, C. M. (1993). Aversive stimuli in MA: Allyn & Bacon.

academic interactions between students with Musser, E. H., Bray, M. A., Kehle, T. J., & Jenson, W.

serious emotional disturbance and their teach- R. (2001). Reducing disruptive behaviors in

ers. Behavioral Disorders, 18, 265–274. students with serious emotional disturbance.

Hall, G. E., & Hord, S. M. (2001). Implementing School Psychology Review, 30, 294–304.

change: Principles, patterns and potholes. Need- Oliver, R. M. (2009). The effects of teachers’

ham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. universal classroom management practices on

Hall, G. E., Loucks, S. F., Rutherford, W. L., & behavior: A meta-analysis. Unpublished manu-

Newton, B. W. (1975). Levels of use of the script.

innovation: A framework for analyzing innova- Oliver, R. M., & Reschly, D. J. (2007, December).

tion adoption. Journal of Teacher Education, 26, NCCTQ connections paper. Improving out-

52–56. comes in general and special education: Teach-

Hord, S., Rutherford, W., Huling-Austin, L., & Hall, er preparation and professional development in

G. (1987). Taking charge of change. Alexandria, effective classroom management. Washington,

VA: ASCD. DC: National Comprehensive Center for Teach-

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement er Quality.

Act 20 U.S.C. 1400 et seq. 34 C.F.R. 300 (2004, Reddy, L. A., & Richardson, F. D. (2006). School-

2006). based prevention and intervention programs for

Katsiyannis, A., Zhang, D., & Conroy, M. A. (2003). children with emotional disturbance. Education

Availability of special education teachers: and Treatment of Children, 29, 379–404.

Trends and issues. Remedial and Special Edu- Reid, R., Gonzalez, J. E., Nordness, P. D., Trout, A.,

cation, 24, 246–251. & Epstein, M. H. (2004). A meta-analysis of the

Kauffman, J. M. (2005). Characteristics of emotional academic status of students with emotional/

and behavioral disorders of children and youth behavioral disturbance. Journal of Special Edu-

(8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson cation, 38, 130–143.

Education. Reschly, D., Smartt, S., Oliver, R., & Holdheide, L.

Kehle, T. J., Bray, M. A., Theodore, L. A., Jenson, W. (2007). Innovation configurations to improve the

R., & Clark, E. (2000). A multi-component availability of highly qualified teachers for

intervention designed to reduce disruptive class- students with disabilities and at-risk character-

room behavior. Psychology in the Schools, 37, istics. Washington, DC: National Comprehen-

475–481. sive Center for Teacher Quality.

Kellam, S., Ling, X., Merisca, R., Hendricks Brown, Roy, P., & Hord, S. M. (2004). Innovation configu-

C., & Ialongo, N. (1998). The effect of the level rations chart a measured course toward change.

of aggression in the first grade classroom on the Journal of Staff Development, 25, 54–58.

course and malleability of aggressive behavior Shores, R. E., Gunter, P. L., & Jack, S. L. (1993).

into middle school. Development and Psycho- Classroom management strategies: Are they

pathology, 10, 165–185. setting events for coercion? Behavioral Disor-

Kellam, S. G., Mayer, L. S., Rebok, G. W., & ders, 18, 92–102.

Hawkins, W. E. (1998). The effects of improving Siebert, C. J. (2005). Promoting preservice teacher’s

achievement on aggressive behavior and im- success in classroom management by leveraging

proving aggressive behavior on achievement a local union’s resources: A professional devel-

through two prevention interventions: An inves- opment school initiative. Education, 125,

tigation of causal paths. In B. Dohrenwend (Ed.), 385–392.

Adversity, stress, and psychpathology (pp. 486– Simonsen, B., Fairbanks, S., Briesch, A., Myers, D., &

505). New York: Oxford Press. Sugai, G. (2008). Evidence-based practices in

Kerr, M. M., & Nelson, C. M. (2002). Strategies for classroom management: Considerations for re-

addressing behavior problems in the classroom search to practice. Education and Treatment of

(5th ed.). Columbus, OH: Merrill Prentice Hall. Children, 31, 351–380.

Landrum, T. J., Tankersley, M., & Kauffman, J. M. Smartt, S. M., & Reschly, D. J. (2007). Barriers to the

(2003). What’s special about special education preparation of highly qualified teachers in

for students with emotional and behavioral reading (TQ Research and Policy Brief). Wash-

disorders? Journal of Special Education, 37, ington, DC: National Comprehensive Center for

148–156. Teacher Quality.

Lewis, T. J., & Sugai, G. (1999). Effective behavior Steiner, D. M., & Rozen, S. D. (2004). Preparing

support: A systems approach to proactive tomorrow’s teachers: An analysis of syllabi from

schoolwide management. Focus on Exceptional a sample of America’s schools of education. In

Children, 31, 1–24. F. M. Hess, A. J. Rotherham, & K. Walsh (Eds.),

Martella, R. C., Nelson, J. R., & Marchand-Martella, A qualified teacher in every classroom? Apprais-

N. E. (2003). Managing disruptive behaviors in ing old answers and new ideas (pp. 119–

the schools: A schoolwide, classroom, and 148). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

198 / May 2010 Behavioral Disorders, 35 (3), 188–199

Sutherland, K. S., Lewis-Palmer, T., Stichter, J., & learning. Washington, DC: National Council on

Morgan, P. L. (2008). Examining the influence Teacher Quality.

of teacher behavior and classroom context

on the behavioral and academic outcomes

for students with emotional and behavioral AUTHORS’ NOTE

disorders. Journal of Special Education, 41,

223–233. Preparation of this article was funded in part

Tooke, J. (1997). Middle school math teachers: What by the National Comprehensive Center for

do they need from preservice programs? The

Teacher Quality (S283B050051). The opinions

Clearing House, 71, 51–52.

expressed in this article are those of the

van Lier, P. A. C., Muthén, B. O., van der Sar, R. M.,

& Crijnen, A. A. M. (2004). Preventing disrup- authors and do not necessarily reflect those

tive behavior in elementary schoolchildren: of the funding agency.

Impact of a universal classroom-based interven-

tion. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychol- Address correspondence to Regina M. Oliver,

ogy, 72, 467–478. Peabody #228, 230 Appleton Place, Nash-

Wagner, M., Friend, M., Bursuck, W., Kutash, K., ville, TN 37203-5721; E-mail: regina.m.

Duchnowski, A., Sumi, W., & Epstein, M. oliver@vanderbilt.edu.

(2006). Educating students with emotional dis-

turbances: A national perspective on school

programs and services. Journal of Emotional and

Behavioral Disorders, 14, 12–30.

MANUSCRIPT

Walsh, K., Glaser, D. R., & Wilcox, D. D. (2006).

What education schools aren’t teaching about Initial Acceptance: 3/28/08

reading and what elementary teachers aren’t Final Acceptance: 2/27/09

Behavioral Disorders, 35 (3), 188–199 May 2010 / 199

You might also like

- Effects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsFrom EverandEffects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsNo ratings yet

- Co-Teching EBD Students 92008)Document6 pagesCo-Teching EBD Students 92008)Duane Conrad100% (1)

- 14-02-2020-1581685429-7-Ijhrm-1. Ijhrm - Classroom Management and Its Implications On LeadershipDocument15 pages14-02-2020-1581685429-7-Ijhrm-1. Ijhrm - Classroom Management and Its Implications On Leadershipiaset123No ratings yet

- Aa Body Chapter PPDocument37 pagesAa Body Chapter PPsung_kei_pinNo ratings yet

- Attitudes of Teachers Towards Inclusive Education-5-6Document2 pagesAttitudes of Teachers Towards Inclusive Education-5-6German Andres Diaz DiazNo ratings yet

- Attitudes of Teachers Towards Inclusive Education-5-8Document4 pagesAttitudes of Teachers Towards Inclusive Education-5-8German Andres Diaz DiazNo ratings yet

- Compiled Classroom Management Employed Practice Elementary - Docx - 1Document82 pagesCompiled Classroom Management Employed Practice Elementary - Docx - 1arden jayawonNo ratings yet

- JournalDocument16 pagesJournalAye Pyae SoneNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Its BackgroundDocument17 pagesThe Problem and Its BackgroundAriane JimenezNo ratings yet

- Issues & Challenges - IEDocument11 pagesIssues & Challenges - IEYUVANo ratings yet

- Fadipe Chapter 1-3Document26 pagesFadipe Chapter 1-3Atoba AbiodunNo ratings yet

- Effective Classroom ManagementDocument24 pagesEffective Classroom ManagementAmbrosious100% (1)

- Ed 3Document10 pagesEd 3api-297150429No ratings yet

- Action ResearchDocument17 pagesAction ResearchRae Jean BolañosNo ratings yet

- McGuireetal 2023Document23 pagesMcGuireetal 2023Zainab RamzanNo ratings yet

- Pre-service Teachers’ Beliefs About Effective Behaviour ManagementDocument13 pagesPre-service Teachers’ Beliefs About Effective Behaviour ManagementmarlazmarNo ratings yet

- Classroom Management FundamentalsDocument23 pagesClassroom Management FundamentalsWan Amir Iskandar IsmadiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 and 2 ARDocument12 pagesChapter 1 and 2 ARkimahmin1No ratings yet

- Managing Student Behavior in The Middle Grades Using Class Wide Function Related Intervention Teams'Article1Document16 pagesManaging Student Behavior in The Middle Grades Using Class Wide Function Related Intervention Teams'Article1Justin BrownNo ratings yet

- JP 02 2 095 11 068 Jeloudar S Y TTDocument8 pagesJP 02 2 095 11 068 Jeloudar S Y TTDavid TingNo ratings yet

- Impact of Classroom Management Strategies on Acade (1)Document12 pagesImpact of Classroom Management Strategies on Acade (1)rcorteza84No ratings yet

- The Challenging Behaviors Faced by The Preschool Teachers in Their ClassroomDocument26 pagesThe Challenging Behaviors Faced by The Preschool Teachers in Their ClassroomEDDIE LYN SEVILLANONo ratings yet

- ED616822Document39 pagesED616822Aphro ChuNo ratings yet

- Body Jam PDFDocument76 pagesBody Jam PDFNathaniel AngueNo ratings yet

- Examining Educators Views of Classroom Management and Instructional Strategies School Site Capacity For Supporting Students Behavioral NeedsDocument12 pagesExamining Educators Views of Classroom Management and Instructional Strategies School Site Capacity For Supporting Students Behavioral NeedsMeliha UygunNo ratings yet

- Complete 2Document31 pagesComplete 2Claire LagartoNo ratings yet

- Bahrami - Self-Efficacy Skills of Kindergarten & First Grade TeachersDocument16 pagesBahrami - Self-Efficacy Skills of Kindergarten & First Grade TeachersEleanor Marie BahramiNo ratings yet

- Classroom Management Practices of TeacheDocument59 pagesClassroom Management Practices of TeacheJorge Andrei Fuertes100% (1)

- DEFEND-1Document49 pagesDEFEND-1Nelgine Navarro BeljanoNo ratings yet

- Classroom Behaviour Management Strategies MSDocument19 pagesClassroom Behaviour Management Strategies MSSofía Rodríguez HidalgoNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Students' Science PerformanceDocument20 pagesFactors Affecting Students' Science PerformanceHA MesNo ratings yet

- Novice Teachers Training and Support NeeDocument13 pagesNovice Teachers Training and Support Neezgr2yhf7wpNo ratings yet

- Action Research Student BehaviorDocument14 pagesAction Research Student Behaviormarvin pedrosaNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Immersion Program To Students Communication Skills and BehaviorDocument22 pagesThe Impact of Immersion Program To Students Communication Skills and Behaviorroseannquinanola16No ratings yet

- Classroom Study for Learners with Special Needs <40Document11 pagesClassroom Study for Learners with Special Needs <40gelma furing lizalizaNo ratings yet

- How Students Behave and Teachers' StrategiesDocument13 pagesHow Students Behave and Teachers' StrategiesAngelo ViloNo ratings yet

- Good Versus Bad Teaching - NichollsDocument29 pagesGood Versus Bad Teaching - Nichollsapi-300172472No ratings yet

- TEFL 8.classroom ManagementDocument5 pagesTEFL 8.classroom ManagementHadil BelbagraNo ratings yet

- TO-BE-PRINT-AutosavedDocument54 pagesTO-BE-PRINT-AutosavedNelgine Navarro BeljanoNo ratings yet

- Perceptions of Prospective Teachers About Factors Influencing Classroom ManagementDocument16 pagesPerceptions of Prospective Teachers About Factors Influencing Classroom ManagementMuhammad Azam GujjarNo ratings yet

- EDSE 2712 - Group Assignment - 3Document18 pagesEDSE 2712 - Group Assignment - 3Patrius KerrNo ratings yet

- J Sbspro 2009 01 218Document11 pagesJ Sbspro 2009 01 218helena ribeiroNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Perceived Student Effort On Teacher Impressions of Students With Learning DifficultiesDocument7 pagesThe Effect of Perceived Student Effort On Teacher Impressions of Students With Learning DifficultiesSteven JiménezNo ratings yet

- Strategies For Success Evidence Based Instructional Practices For Students With Emotional and Behavioral DisordersDocument9 pagesStrategies For Success Evidence Based Instructional Practices For Students With Emotional and Behavioral Disordersapi-550243992No ratings yet

- Workshop 5 - CL Hdpsy Cmu 19 40Document34 pagesWorkshop 5 - CL Hdpsy Cmu 19 40Nithya ShineyNo ratings yet

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument10 pagesReview of Related LiteratureCleo LexveraNo ratings yet

- Misbehavior - Chapter 1 5Document58 pagesMisbehavior - Chapter 1 5Lovely Joy RinsulatNo ratings yet

- Teacher Attitudes and Student Motivation in Science LearningDocument79 pagesTeacher Attitudes and Student Motivation in Science LearningReynato AlpuertoNo ratings yet

- Strategies For Managing - AdhdDocument15 pagesStrategies For Managing - AdhdEspíritu Ciudadano100% (2)

- How PreparedDocument10 pagesHow Preparedsamaneh cheginiNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Need-Supportive Teacher Behavior On The Motivation of Students With Congenital DeafblindnessDocument14 pagesThe Influence of Need-Supportive Teacher Behavior On The Motivation of Students With Congenital DeafblindnessjohnNo ratings yet

- Classroom management techniquesDocument53 pagesClassroom management techniquesIbtisam ButtNo ratings yet

- Correlation of Classroom Management Styles, Learning Motivation and Pupils' Academic AchievementDocument15 pagesCorrelation of Classroom Management Styles, Learning Motivation and Pupils' Academic AchievementPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Effect of Classroom Management Skills As A Parameter of Personality Development Module On Teacher Effectiveness of Teacher Trainees in Relation To Internal Locus of ControlDocument4 pagesEffect of Classroom Management Skills As A Parameter of Personality Development Module On Teacher Effectiveness of Teacher Trainees in Relation To Internal Locus of ControlSherylChavezDelosReyesNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Study Skills and Academic PerformanceDocument15 pagesRelationship Between Study Skills and Academic PerformanceSophia VirayNo ratings yet

- Teachers Classroom Management PracticesDocument10 pagesTeachers Classroom Management PracticesRegistrar Moises PadillaNo ratings yet

- Research JonieDocument5 pagesResearch JonieMeow MarNo ratings yet

- Receiving Teachers Teaching Efficacy and Performance in A Secondary SchoolDocument7 pagesReceiving Teachers Teaching Efficacy and Performance in A Secondary SchoolPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Teacher Efficacy Managing Preschool Behavior ChallengesDocument12 pagesTeacher Efficacy Managing Preschool Behavior ChallengesAnonymous TLQn9SoRRbNo ratings yet

- Basic School Teachers' Personality Type As Determinant of Classroom Management in Lagos State, NigeriaDocument6 pagesBasic School Teachers' Personality Type As Determinant of Classroom Management in Lagos State, NigeriaJournal of Education and LearningNo ratings yet

- Classroom Observation and Mathematics Education ResearchDocument27 pagesClassroom Observation and Mathematics Education ResearchAzis IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Teacher Education For The Changing Demographics of SchoolingDocument237 pagesTeacher Education For The Changing Demographics of Schoolingximena oyarzo100% (1)

- Collaborative Teaching ResearchDocument6 pagesCollaborative Teaching Researchximena oyarzoNo ratings yet

- Validation of The Index For Inclusion QuestionnaireDocument13 pagesValidation of The Index For Inclusion QuestionnaireCatarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- Teacher Education For Inclusion Changing Paradigms... - (Chapter 10 Preparing Teachers To Work With Parents and Families of Lea... )Document9 pagesTeacher Education For Inclusion Changing Paradigms... - (Chapter 10 Preparing Teachers To Work With Parents and Families of Lea... )ximena oyarzoNo ratings yet

- Scorgie, 2010, Teacher Education For Inclusion Changing Paradigms... - (Chapter 9 Fostering Empathy and Understanding A Longitudinal Case Stud... )Document9 pagesScorgie, 2010, Teacher Education For Inclusion Changing Paradigms... - (Chapter 9 Fostering Empathy and Understanding A Longitudinal Case Stud... )ximena oyarzoNo ratings yet

- Aacte NCLD RecommendationDocument32 pagesAacte NCLD Recommendationmarin_m_o3084No ratings yet

- EJ926862Document20 pagesEJ926862ximena oyarzoNo ratings yet

- Teachers Prepared for Inclusive Education in IndiaDocument10 pagesTeachers Prepared for Inclusive Education in Indiaximena oyarzoNo ratings yet

- Preparing Teachers To Work in Schools FoDocument2 pagesPreparing Teachers To Work in Schools Foximena oyarzoNo ratings yet

- Franke (2007). Mathematics Teaching and Classroom PracticeDocument33 pagesFranke (2007). Mathematics Teaching and Classroom PracticeAgustina Salinas HerreraNo ratings yet

- ED 250 Reflection on Teaching RolesDocument2 pagesED 250 Reflection on Teaching Rolesmalisha chandNo ratings yet

- Episode 1 2 3Document69 pagesEpisode 1 2 3JASMINE CEDE�ONo ratings yet

- The End of 'Chalk and Talk' PDFDocument4 pagesThe End of 'Chalk and Talk' PDFchew shally100% (1)

- The Real World: Lived Experiences of Student Nurses During Clinical PracticeDocument10 pagesThe Real World: Lived Experiences of Student Nurses During Clinical PracticeFrildah Vongula VongulahNo ratings yet

- The Role of Information Technology in EducationDocument20 pagesThe Role of Information Technology in EducationHwee Kiat Ng100% (19)

- Application Form For Special ProgramsDocument5 pagesApplication Form For Special ProgramsRonnie Francisco Tejano100% (1)

- Inclusive Education in India: A Paradigm Shift in Roles, Responsibilities and Competencies of Regular School TeachersDocument16 pagesInclusive Education in India: A Paradigm Shift in Roles, Responsibilities and Competencies of Regular School TeachersPhilip James LopezNo ratings yet

- 01 IntroDocument20 pages01 Introwan_hakimi_1No ratings yet

- Chapter 7Document15 pagesChapter 7api-294209774No ratings yet

- The Best ESL Shortcut - 6 Short StoriesDocument12 pagesThe Best ESL Shortcut - 6 Short StoriesRNageswariNo ratings yet

- Lead Teacher Job DescriptionDocument3 pagesLead Teacher Job Descriptionapi-490916133No ratings yet

- Edtpa Task 2 AssignmentDocument3 pagesEdtpa Task 2 Assignmentapi-500185788No ratings yet

- Possible Questions For InterviewDocument3 pagesPossible Questions For InterviewJerald Realizan LorioNo ratings yet

- Sharpening Classroom SkillsDocument12 pagesSharpening Classroom SkillsZiaurrehman Abbasi75% (8)

- 150 TextosDocument17 pages150 TextosgersonpexeNo ratings yet

- Reviews After A Visit To Pea English Center in Binh ThoDocument2 pagesReviews After A Visit To Pea English Center in Binh ThoThơ Nguyễn Thị NhãNo ratings yet

- Teach by Actions Rather than Words: A Teacher's HandbookDocument38 pagesTeach by Actions Rather than Words: A Teacher's HandbookIbrahima SakhoNo ratings yet

- An EnrichmentDocument26 pagesAn EnrichmentReem EL HawaryNo ratings yet

- Speaking and ListeningDocument54 pagesSpeaking and Listeningdwi100% (6)

- Closing The Achievement Gap With Curriculum Enrichment and DifferentiationDocument30 pagesClosing The Achievement Gap With Curriculum Enrichment and DifferentiationSANDRA MENXUEIRONo ratings yet

- Tourette Syndrome Educational Based-InterventionsDocument24 pagesTourette Syndrome Educational Based-InterventionsThelma Lizeth Cárdenas Macías100% (1)

- WORKSHOP OF ENGLISH TEACHERS- EAST JAVA PROGRAMDocument5 pagesWORKSHOP OF ENGLISH TEACHERS- EAST JAVA PROGRAMSumarawati SumNo ratings yet

- Discussionquestions PortfolioDocument7 pagesDiscussionquestions Portfolioapi-315537808No ratings yet

- Brigada Eskwela Clean-Up ReportDocument5 pagesBrigada Eskwela Clean-Up ReportRichie Macasarte100% (1)

- PlickersDocument6 pagesPlickersapi-384339971No ratings yet

- Group 3 PRDocument16 pagesGroup 3 PRkamina ayatoNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2 Edu 300005 2Document11 pagesAssignment 2 Edu 300005 2smvvpadmaNo ratings yet

- Culturally Safe Classroom Context PDFDocument2 pagesCulturally Safe Classroom Context PDFdcleveland1706No ratings yet

- Classroom Management Plan Madison L. Meehan University of Nevada Las VegasDocument32 pagesClassroom Management Plan Madison L. Meehan University of Nevada Las Vegasapi-291513867No ratings yet