Professional Documents

Culture Documents

IMF - Capital Account Convertibility

Uploaded by

Nasrin LubnaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

IMF - Capital Account Convertibility

Uploaded by

Nasrin LubnaCopyright:

Available Formats

III

Capital Account Convertibility

T he importance of international capital movements

has long been recognized. First, international cap-

ital movements provide vital support to the multilat-

although restrictions remain on the underlying trans-

actions with regard to foreign investments in some

sectors and for some types of instruments. The liber-

eral trading system. This support comes not only in alization of foreign exchange markets has gone hand

the form of short-term trade finance, but also in the in hand with domestic financial market liberalization,

transfer of financial resources from countries with including increasingly indirect instruments of mone-

current account surpluses to ones with current account tary control. By the end of 1994, all industrial country

deficits. Second, capital movements play a critical currencies became convertible for capital transfers, as

role in economic development. The impact in aug- Iceland removed remaining restrictions. It had long

menting domestic savings is most obvious when the been thought that liberalizing capital required a strong

capital is transferred in the form of foreign direct in- external position, and a number of developing coun-

vestment, although by seeking the highest rates of tries with structurally strong balance of payments po-

risk-adjusted return, portfolio investment also has po- sitions had for some decades eliminated exchange

tentially significant benefits for economic growth. controls on capital movements. In recent years, a

The impact of capital movements on monetary and ex- number of countries with hitherto weak balance of

change policies is also well recognized. payments have also fully eliminated the controls in the

context of comprehensive stabilization and liberaliza-

tion programs. Nevertheless, the majority of develop-

Global Trends Toward Decontrol of ing countries continue to restrict outflows of capital,

Capital Movements usually with the aim of preserving scarce domestic

savings by reducing capital flight.

Capital convertibility in this paper focuses on free-

dom from restrictions or taxes imposed directly on Industrial Countries—Convertibility

foreign exchange transactions in a way analogous to Nearly Completed

Article VIII, but on both inward and outward capital

transfers. Under this approach, the following could be The end of the 1970s marked a turning point in in-

considered as exchange restrictions that apply to cap- dustrial countries' use of exchange controls on capital

ital movements and that would give rise to exchange movements, with the suspension of all exchange con-

controls on capital account or discriminatory currency trols in 1979 by the United Kingdom and the disman-

practices as related to capital transfers: tling of restrictions on capital movements in Japan be-

ginning in 1980.17 Australia dismantled most controls

• Specific restrictions or requirements for approval to in 1983 and New Zealand in 1985. In 1986, the

purchase foreign exchange for the purpose of ac- Netherlands removed its remaining restrictions, and

quiring assets abroad; France, by removing the devise titre market for resi-

• Limits on the amount of foreign exchange that can dents' acquisition of securities abroad, achieved,

be transferred for the purposes of investment along with Denmark, virtually full liberalization by

abroad; 1989. Italy eliminated its compulsory deposit require-

• Requirements, authorizations, or restrictions on the ment, which discouraged various forms of investment

repatriation of capital or foreign exchange holdings; abroad by residents; Austria and Ireland removed a

and substantial number of restrictions; and Sweden and

• Multiple currency practices that apply to the pur- Norway liberalized exchange controls in 1989 and

chase or surrender of foreign exchange related to

capital transfers.

As normally defined, the concept of capital convert- 17

During the 1980s, only Finland, France, Norway, and Spain felt

ibility does not cover prudential requirements or mar- it necessary to suspend temporarily the freedom of capital move-

ket standards. ments under the codes of liberalization of capital movements of the

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Virtually all industrial countries have ended ex- For a detailed discussion see Liberalization of Capital Movements

change controls on international capital movements, and Financial Services (Paris: OECD, 1990).

11

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

Ill CAPITAL ACCOUNT CONVERTIBILITY

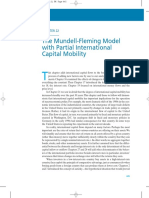

Chart 2. Capital Controls in Industrial turn abolished in May 1994. Iceland abolished all ex-

and Developing Countries1 change controls on long-term capital movements at the

(Number of measures) beginning of 1994 and abolished all such controls on

short-term movements by the end of 1994.

Apart from exchange controls, industrial countries

Industrial Countries have applied extensive controls to underlying capital

transactions. The most restricted operation has been

the admission of foreign securities on the domestic

capital market, often reflecting concerns about the ab-

sorptive capacity of the domestic financial markets.

Foreign bank credits and loans (both inflows and out-

flows) unrelated to international trade have also been

more heavily restricted than other types of capital

movements, possibly because of concerns that such

flows were short term. However, commercial credits

related to international trade have generally enjoyed a

high degree of freedom. While foreign direct invest-

ment inflows were generally treated liberally, many

countries screened such flows from the point of view

of ownership and industrial structure and in some cases

limited the areas of economic activity or the flows in

Developing Countries the context of bilateral investment treaties. Foreign in-

vestments in real estate and the buying and selling of

securities tended to be treated more restrictively than

foreign direct investment inflows, for reasons that

sometimes included concerns for investor protection.

A few industrial countries temporarily intensified re-

strictions on cross-border capital movements in 1992.

In an effort to avert devaluations of their currencies

within the exchange rate mechanism (ERM) of the Eu-

ropean Monetary System (EMS), Ireland and Portugal

temporarily imposed or intensified direct controls over

short-term (speculative) capital flows. However, these

controls were not generally considered to have been ef-

fective in reducing short-term speculative pressures

and were rescinded by the end of 1992.

Source: IMF, AREAER (various issues). A broader concern is that capital controls are not

1These trends do not purport to indicate the economic significance only ineffective in controlling short-term speculative

of the measures taken over the period; however, they provide an flows—the main rationale for Article VI in the origi-

overall sense of whether member countries are taking more or less re-

strictive measures.

nal drafting of the IMF's Articles of Agreement—but

that they may discourage longer-term portfolio and di-

rect investment flows. The impact of capital account

1990. In March 1990, Belgium and Luxembourg abol- liberalization on the capital accounts of nine industrial

ished the two-tier exchange rate system that they had countries has been reviewed (Australia, Denmark,

operated jointly since 1951. Since 1985, industrial France, Italy, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway,

countries have implemented only a few measures Sweden, and United Kingdom). All of these countries

tightening controls on capital (Chart 2). recorded larger net foreign direct investment outflows

During 1991-94, those industrial countries that con- either in the year of the liberalization of capital con-

tinued to maintain exchange controls on capital move- trols or in subsequent years. In France, Italy, and the

ments moved to eliminate them. Extensive liberaliza- Netherlands, the larger foreign direct investment out-

tions were undertaken by Austria in 1991, by Finland flows were more than offset by larger portfolio and

in 1991-92, and by Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Norway, other capital inflows.

Portugal, Spain, and Sweden in 1992 and 1993. Ireland

and Portugal had eliminated all exchange control re-

Emerging Convertibility in Developing Countries

strictions by the beginning of 1993. In March 1993,

Greece eliminated controls on various capital transac- As a result of the liberalizations by industrial coun-

tions, leaving only restrictions on loans and deposit ac- tries, the issue of capital account convertibility now

counts of less than one year's maturity; these were in affects almost exclusively developing countries.

12

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

Global Trends Toward Decontrol of Capital Movements

Countries such as the Middle East oil exporting coun- A common manifestation of exchange controls is

tries and the offshore financial centers of Hong Kong the requirement to repatriate foreign exchange earn-

and Singapore have maintained liberal capital accounts ings. Such requirements were in force at the end of

for many years. Indonesia eliminated its capital con- 1993 in 128 IMF member countries, of which 38 have

trols in 1970, and a number of small island economies assumed the obligations of Article VIII. In 106 of the

and those countries that use the U.S. dollar, such as 128 countries, the repatriated proceeds, subject to full

Liberia and Panama, have also maintained liberal ex- or partial requirements, had to be surrendered to the

change controls on capital movements. However, in central bank or sold to domestic commercial banks

most developing countries, outward capital move- within a specified period. However, significant liber-

ments have remained tightly controlled until relatively alization of surrender requirements occurred during

recently. Progress toward currency convertibility may 1990-93. Surrender requirements were either abol-

have been slower in developing countries because of ished or their ratios reduced significantly in 41 coun-

the more acute shortages of domestic savings and the tries, while on only 13 occasions did countries intro-

greater perceived risk of capital flight, particularly in duce surrender requirements or tighten existing

countries with below-market interest rates and gener- requirements. Several of the countries that introduced

ally unsound macro policies. The more recent progress surrender requirements during 1990-93 were former

reflected the adoption of more realistic exchange rates republics of the Soviet Union that had acceded to

by this group of countries since the early 1980s and the membership in the IMF and introduced their own

development of more market-based instruments of currencies.

monetary policy. The relationship to the exchange rate Among the reforming centrally planned economies

is a close one because exchange controls have typically and some other developing countries, there has been a

been used in attempts to maintain an exchange rate that practice of allowing residents to hold foreign ex-

was viewed as overvalued by the market. change locally and exchange it freely for domestic

In countries not considering a general liberalization currency—so-called internal convertibility. For exam-

of capital controls, greater emphasis was given in the ple, Bulgaria, the former Czech and Slovak Federal

aftermath of the debt crisis to liberalizing foreign direct Republic (nonenterprise holdings), Hungary, Poland,

investment inflows.18 To foster the investment flows, and Romania, as well as most countries of the former

the World Bank's Multilateral Investment Guarantee Soviet Union followed such policies. By providing

Agency (MIGA) was formally constituted in April residents with the opportunity to hold and invest in

1988.19 On a bilateral level, the U.S. Government had foreign currencies through the local banking systems,

announced in late 1981 that it would negotiate bilateral these policies may have helped to limit capital flight,

investment treaties (BITs) focused solely on invest- although they also complicated monetary manage-

ment. Unlike the previous bilateral treaties, which had ment. In addition, experiences in other countries with

established rights and obligations of nationals and deposit accounts denominated in foreign currency

companies, the BIT establishes rights and obligations have revealed the exposure risks of the implicit ex-

with respect to specific forms of investment.20 change rate guarantees for depositors and banks, and

18

in some cases, for central banks.21

The IMF and the World Bank, mainly through the work of the

Development Committee, have emphasized this aspect in recent

More recently, in the wake of the debt crisis and

documents. See Determinants and Systemic Consequences of Inter- after experiencing substantial capital flight, develop-

national Capital Flows, IMF Occasional Paper No. 77 (Washing- ing countries appear to have shifted toward liberaliza-

ton: IMF, 1991); Development Committee, Development Issues: tion of their capital accounts. Many countries have

Presentations to the 46th Meeting of the Development Committee, liberalized exchange controls on capital movements

Development Committee Series No. 31 (Washington: World Bank,

1993); "Development Committee Communique" and "Group of 24 and controls that directly affect the underlying capital

Communique," IMF Survey, May 17, 1993; and G.P. Pfeffermann transactions and have implemented relatively few

and A. Madarassy, Trends in Private Investment in Developing tightening measures. The major developments during

Countries, 1993: Statistics for 1970-91, IFC Discussion Paper 1991-93 are as follows:

No. 16 (Washington: World Bank, December 1992).

19

By the end of MIGA's first full financial year of operations, 69 • Eleven developing countries—Argentina, Costa

preliminary applications for guarantee covering potential direct in- Rica, El Salvador, The Gambia, Grenada, Honduras,

vestments in 24 member developing countries and a broad range of

sectors were registered with MIGA. In 1992-93, MIGA facilitated

Jamaica, Peru, Philippines, Trinidad and Tobago, and

almost $2 billion in direct investment flows. Given the long-term Turkey—extensively liberalized their exchange con-

nature of most direct investment, MIGA typically provides guaran- trols on capital movements, mostly in the context of

tees for 15 years. measures aimed at strengthening a weak external

20

The prototype treaty reflects six principles of a liberal invest- position. As a result of these and earlier changes made

ment regime, including free transfers of foreign exchange for all

capital and all returns on an investment; full convertibility is to in similar circumstances, Argentina, Costa Rica,

apply to any investments covered by a BIT. As of July 7, 1993, 24 El Salvador, Grenada, Guyana, Indonesia, Jamaica,

countries had signed BITs with the United States, including 10

countries from Eastern Europe or the former Soviet Union, of

21

which 13 have come into force. See Section IV.

13

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

Ill CAPITAL ACCOUNT CONVERTIBILITY

Paraguay, Peru, and Trinidad and Tobago now have taken as part of a program of macroeconomic stabi-

full currency convertibility.22 lization or structural adjustment. In five of the coun-

• Twenty-three developing countries liberalized con- tries, these programs were supported by an IMF

trols on foreign direct investment inflows, and two arrangement that included debt reschedulings. In

developing countries (Jamaica and Korea) also liber- some cases, the capital account liberalizations were

alized their controls on foreign direct investment part of a broader normalization of external financial

outflows. relations.

• Twelve developing countries relaxed controls on Second, in all but one of the countries, the extensive

long-term, and three on short-term, portfolio inflows. liberalization of the capital account was in the context

In most cases, the liberalization granted foreigners of a floating or managed floating exchange rate. The

freedom to invest in local securities or increased resi- one country that pegged its exchange rate, Argentina,

dents' freedom to borrow abroad under exchange con- depreciated its exchange rate at the time that it liber-

trol regulations. In addition to the 11 developing coun- alized its capital.

tries that significantly liberalized exchange controls, Third, extensive liberalization of the capital account

another 5—Brazil, Colombia, Israel, Mali, and Mauri- either occurred simultaneously with liberalization of

tius—eased or eliminated exchange controls on short- interest rates and movement to indirect instruments of

and long-term portfolio outflows. monetary control—in the case of Guyana and

• None of the developing countries reported an in- Paraguay—or followed a broader liberalization of the

tensification of restrictions on portfolio or direct in- domestic financial system, including freeing interest

vestment outflows, and only three developing coun- rates, eliminating credit controls, and introducing in-

tries intensified controls on inflows—Brazil on direct instruments.24 However, in no case was cur-

foreign investments in real estate, Malaysia on resi- rency convertibility introduced without concurrent or

dents' foreign borrowing, and Chile on short-term earlier moves toward market interest rates.

capital inflows.23 Fourth, extensive liberalization of current account

• Ten developing countries liberalized commercial transactions occurred either before the liberalization

banks' operations in foreign exchange. Measures in- of the capital account or at the same time. In the cases

cluded liberalization of banks' operations in foreign of Argentina, Jamaica, and the Philippines, the capital

currencies (Algeria, Dominican Republic, Jordan, Sri account liberalizations followed a number of years of

Lanka, Tunisia, and Turkey), forward exchange trans- reforms to eliminate multiple exchange rates and re-

actions (India and Korea), and relaxation of surrender strictions on current transactions. In Costa Rica,

requirements (Chile and Jamaica). Six countries— El Salvador, Paraguay, Peru, and Trinidad and Tobago,

Brazil, The Gambia, Indonesia, Paraguay, Philippines, current and capital account transactions were liberal-

and Solomon Islands—tightened controls on banks' ized virtually simultaneously.

foreign exchange operations. In all cases, the tighten- Fifth, in all cases the liberalizations were accompa-

ing applied to banks' open foreign currency positions nied by a strengthening of the overall balance of pay-

and therefore appears to have been implemented pri- ments. In many, the balance of payments had begun to

marily as a prudential measure rather than as an ex- improve prior to the liberalizations, owing to the im-

change control. pact of stabilization measures and exchange rate ad-

• Twenty-five developing countries liberalized ex- justment that had preceded capital liberalization.

change controls on resident domestic operations in for- Rather than weakening the macroeconomic adjust-

eign currency. One country, Honduras, simplified ex- ment, the elimination of capital controls appears to

change arrangements that applied to capital transfers. have helped sustain it. The impact of the liberalization

on private capital flows varied from country to coun-

A preliminary review of developing country experi- try. Total private inflows increased in Argentina, Costa

ences with extensive liberalization of their capital ac- Rica, Guyana, Indonesia, Jamaica, Paraguay, Peru,

counts suggests a number of common features. and Venezuela owing in part to increased domestic in-

First, in all the cases, the extensive liberalization terest rates. In those countries where data are avail-

measures affecting the capital account were under- able, both foreign direct investment and portfolio in-

flows recorded improvement. In about half of the

22

A number of other countries have free or liberal capital sys- cases, the exchange rate appreciated as the net private

tems, mainly those with structurally strong balance of payments capital account improved, raising issues for competi-

positions. Venezuela has very recently reintroduced limitations on

convertibility, and Mauritius has reportedly introduced capital

tiveness of domestic industry and the current account

convertibility. of the balance of payments.

23

While there is some evidence that capital inflows in Chile

slackened temporarily following the introduction of the controls,

24

evasion of the controls also began quickly; see S. Schadler, M. Interest rates in Indonesia and Venezuela were subject to regu-

Carkovic, A. Bennet, and R. Kahn, Recent Experiences with Surges lation at the time of the full exchange system liberalization although

in Capital Inflows, IMF Occasional Paper No. 108 (Washington: interest rates had already been adjusted to market-determined

IMF, 1993). levels.

14

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

Evolution of the IMF's Policies on Capital Account Convertibility

Evolution of the IMF's Policies on Capital dures governing capital movements have been estab-

Account Convertibility: A Brief History lished in other forums, including by the OECD,27 and

regional economic and monetary arrangements (such

The main arguments for controlling capital move- as the European Union (EU).28 However, the obliga-

ments have included (1) that capital controls can im- tions established in these forums apply to only part of

prove welfare by increasing the volume of domestic the IMF's membership, mainly industrial countries.

investment and local tax revenue; (2) that the liberal- Article VI, Section 3 of the IMF's Articles of Agree-

ization of the capital account should be sequenced rel- ment provides that "members may exercise such con-

atively late in the reform process to allow for the elim- trols as necessary to regulate international capital

ination of distortions in the goods markets and the movements, but no member may exercise these con-

development of the necessary supporting institutional trols in a manner which will restrict payments for cur-

arrangements, including indirect monetary controls; rent transactions. . . ." Article VI, Section 1 provides

(3) that additional freedom would be provided to do- that the IMF may request a country that is using its

mestic interest rate and exchange rate policy through general resources to impose controls to prevent these

capital controls; and (4) that controls on capital move- resources from being used to meet large or sustained

ments can help protect a country's reserves and im- outflows of capital.

prove its balance of payments. There have been a The approach to convertibility in the IMF's Arti-

number of counterarguments, the most important of cles—that capital movements could legitimately be

which is that the flows may tend to be destabilizing restricted, whereas current international payments

rather than stabilizing. The empirical outcome sug- should be free—can be traced to the Keynes and

gests that industrial countries have judged the macro- White plans for the creation of the IMF. In Keynes's

economic efficiency costs of the controls to exceed the view, in the context of the system of fixed but ad-

benefits, while in developing countries the main expe- justable exchange rates that was envisaged, countries

rience has been the problem of enforcing the controls, had to be able to protect themselves against short-

although recent liberalizations by these countries have term, speculative capital flight and transitory foreign

also questioned the optimality of the controls.25 Under inflows that reflected, in part, concerns about mone-

the Bretton Woods system, controls were seen to make tary independence.29 However, the intention was not

it more difficult for market participants to test the au- to interfere with legitimate long-term international in-

thorities' resolve to defend an exchange rate parity. vestment. Although there is no distinction in the Arti-

However, the advent of floating exchange rates and the cles of Agreement between short-term, speculative

rapid integration of capital markets have shifted the capital flows and productive investment flows, the

balance of costs and benefits away from the controls. language in Article I, by seeking to eliminate foreign

The IMF's Articles of Agreement do not extend the

institution's jurisdiction to exchange transactions and 27

Following a 1989 amendment, the OECD codes generally

transfers related to the large body of international cap- apply to all underlying capital transactions. Prior to that amend-

ital movements, and, as a result, members have been ment, most short-term capital movements, except for commercial

free to restrict capital transfers.26 Rules and proce- credits and loans, were excluded from the codes. The codes were

broadened to cover practically all types of capital movements, but

they do not extend the obligations of members to all types of ex-

25

P. Quirk, "Capital Account Convertibility: A New Model for change transactions related to capital movements. For example,

Developing Countries," in Frameworks for Monetary Stability, ed. taxes on transfers, multiple currency practices applicable to capital

by T. Baliño and C. Cottarelli (Washington: IMF, 1994); DJ. transactions, and advance deposit requirements are not covered by

Mathieson and L. Rojas-Suarez, Liberalization of the Capital Ac- the codes. The OECD membership includes all countries classified

count: Experiences and Issues, IMF Occasional Paper No. 103 by the IMF as industrial countries as well as Turkey.

28

(Washington: IMF, 1993); N.U. Haque and P. Montiel, "Capital Proposals to liberalize capital movements within the EU were

Mobility in Developing Countries—Some Empirical Tests," IMF first expressed in a 1983 initiative on financial integration. This was

Working Paper No. 90/117 (Washington: IMF, 1990); H. Faruqee, followed by a 1987 directive liberalizing certain long-term capital

"Dynamic Capital Mobility in Pacific Basin Developing Countries: transactions and security market transactions between members.

Estimates and Policy Implications," Staff Papers, International The list covered long-term credits relating to commercial transac-

Monetary Fund, Vol. 39 (September 1992); J.E. Greene and tions and the acquisition in the capital market of one member state

P. Isard, Currency Convertibility and the Transformation of Cen- of securities issued by a company in another member state. Shortly

trally Planned Economies, IMF Occasional Paper No. 81 (Wash- thereafter, the EU considered the elimination of all remaining cap-

ington: IMF, 1991); M. Dooley, "Country-Specific Risk Premiums, ital controls as part of a plan to establish a European financial com-

Capital Flight and Net Investment Income Payments in Selective mon market by 1992 in the context of a single market in which

Developing Countries" (unpublished; Washington: IMF, 1986); M. goods, services, capital, and individuals move freely. The condi-

Deppler and M. Williamson, "Capital Flight: Concepts, Measure- tions for such a market included not only elimination of capital con-

ment, and Issues," Staff Studies for the World Economic Outlook trols, but also harmonization of bank supervision rules and taxes on

(Washington: IMF, 1987), pp. 39-58. capital yields.

26 29

See M. Guitian, "Capital Account Liberalization: Bringing J.M. Keynes, "Proposals for an International Clearing Union,"

Policy in Line with Reality," in Capital Controls, Exchange Rates, British Government White Paper Cmd. 6437, April 1943. For a dis-

and Monetary Policy in the World Economy, ed. by S. Edwards cussion of this paper, see J.K. Horsefield (ed.), The International

(Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming, Monetary Fund, 1945-1965: Twenty Years of Internation Monetary

1995). Cooperation, Vol. 3, Documents (Washington: IMF, 1969).

15

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

Ill CAPITAL ACCOUNT CONVERTIBILITY

exchange restrictions that hamper the growth of world Gold notes that, although Article VI, Section 3 per-

trade, may have been intended to suggest that the re- mitting members to exercise control over capital

strictions to be eliminated were not only those that ap- movements was not modified at the time of the second

plied directly to payments in respect of current inter- amendment of the Articles of Agreement, it has to be

national transactions, but also those that inhibited the read in conjunction with the amendment to Article IV,

flow of productive capital.30 Section 1, particularly Section (iii), calling for mem-

White's plan31 viewed exchange controls as an un- bers to avoid manipulating exchange rates. The IMF's

desirable form of interference with trade and capital policies with regard to surveillance over exchange

flows but noted that at times it may be in the best in- rates were amended consistent with the revisions to

terests of a country to impose restrictions on move- the Articles of Agreement on members' exchange rate

ments of capital and goods. "The task . . . is not to pro- policies, The policies established included the princi-

hibit instruments of control but to develop those ple of looking into capital movements in the exercise

measures of control... as will be most effective in ob- of surveillance over exchange rates.33

taining the objectives of world-wide sustained pros-

perity." The background to these views was elaborated

in the U.S. Treasury's commentary.32 33

"The Fund shall consider the following developments as among

those which might include the need for discussion with a member:

30

J. Gold, International Capital Movements Under the Law of the (iii) (b) the introduction or substantial modification for balance

International Monetary Fund, IMF Pamphlet Series No. 21 (Wash- of payments purposes of restrictions on, or incentives

ington: IMF, 1977). for, the inflow or outflow of capital;

31

H.D. White, "Preliminary Draft Proposal for a United Nations (iv) the pursuit, for balance of payments purposes, of monetary

Stabilization Fund and a Bank for Reconstruction and Development and other domestic financial policies that provide abnormal

of the United and Associated Nations" (Mimeo; April 1942). For a encouragement or discouragement to capital flows; and

discussion of this paper, see J.K. Horsefield (ed.), International (v) behavior of the exchange rate that appears to be unrelated

Monetary Fund, 1945-1965. to underlying economic and financial conditions including

32

United States, Department of the Treasury, The Bretton Woods factors affecting competitiveness and long-term capital

Proposals: Questions and Answers on the Fund and the Bank" movements."

(Washington: U.S. Treasury, 1944). Selected Decisions (Washington: IMF, 1993).

16

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

You might also like

- Colonel Bogey March: Kenneth J Alford (Frederick Joseph Ricketts) Arr. by M A SeatonDocument18 pagesColonel Bogey March: Kenneth J Alford (Frederick Joseph Ricketts) Arr. by M A SeatonDaedulunNo ratings yet

- Bayero University, Kano Bayero Business School: A. Course DescriptionDocument56 pagesBayero University, Kano Bayero Business School: A. Course DescriptionMoses AhmedNo ratings yet

- Heilmann, Ann - New Woman Fiction, Women Writing First-Wave Feminism PDFDocument240 pagesHeilmann, Ann - New Woman Fiction, Women Writing First-Wave Feminism PDFIsabella Giordano0% (1)

- Krishna Menon - DisarmamentDocument139 pagesKrishna Menon - DisarmamentEnuga S. Reddy100% (2)

- Exercises On Accounting RatiosDocument7 pagesExercises On Accounting RatiosDiannaNo ratings yet

- BR100 Application Configurations FinancialsDocument58 pagesBR100 Application Configurations FinancialsjaleelmohamedfNo ratings yet

- Template For RTI For TEP PDFDocument2 pagesTemplate For RTI For TEP PDFBharat KaushalNo ratings yet

- Business A Level Revision Notes Series A PDFDocument30 pagesBusiness A Level Revision Notes Series A PDFruvimbo shoniwaNo ratings yet

- Treasury Management Module CDocument58 pagesTreasury Management Module CAbhinav KumarNo ratings yet

- Accounting Cycle 6Document49 pagesAccounting Cycle 6buuh abdi100% (1)

- UN Procurement Practitioner's Handbook-version27Feb2020Document215 pagesUN Procurement Practitioner's Handbook-version27Feb2020Saurabh KumarNo ratings yet

- People V MalansingDocument18 pagesPeople V MalansingFidel Rico NiniNo ratings yet

- Libéralisation Du Compte CapitalDocument4 pagesLibéralisation Du Compte Capitalelyka.paintingNo ratings yet

- Dre Been: What Are Type of Facili. Es Offered by Housing Finance Companies. What Are Some ofDocument10 pagesDre Been: What Are Type of Facili. Es Offered by Housing Finance Companies. What Are Some oframdayal kumawatNo ratings yet

- GlobalizationDocument5 pagesGlobalizationPreeti KumariNo ratings yet

- Financial Globalization: Dr. J.D. Han King's College, UWODocument26 pagesFinancial Globalization: Dr. J.D. Han King's College, UWONazmul H. PalashNo ratings yet

- Many Shades of GreenbackDocument1 pageMany Shades of GreenbacknaikNo ratings yet

- Ib Cia 3Document3 pagesIb Cia 3Kiran RajNo ratings yet

- Master of Business Administration - 4 Sem International Financial Management MF0015Document8 pagesMaster of Business Administration - 4 Sem International Financial Management MF0015777priyankaNo ratings yet

- SFM Forex Highlighted ModuleDocument26 pagesSFM Forex Highlighted ModuleGautam aroraNo ratings yet

- Globalization of Financial MarketsDocument6 pagesGlobalization of Financial MarketsAlinaasirNo ratings yet

- (FinMan) M7 - PPT Presentation 1Document49 pages(FinMan) M7 - PPT Presentation 1christian ReyesNo ratings yet

- Capital Account ConvertibilityDocument2 pagesCapital Account Convertibilitydebajit84No ratings yet

- Managing Foreign Debt and Liquidity: India's Experience: Payments Chaired by DR C Rangarajan. The Committee RecommendedDocument6 pagesManaging Foreign Debt and Liquidity: India's Experience: Payments Chaired by DR C Rangarajan. The Committee RecommendedSaurav SinghNo ratings yet

- Globalisation and The Indian Economy: Globalisation: A Process Associated With Increasing OpennessDocument3 pagesGlobalisation and The Indian Economy: Globalisation: A Process Associated With Increasing OpennessBISWAJEETNo ratings yet

- Exchange Rate and Capital Account Management For Developing CountriesDocument10 pagesExchange Rate and Capital Account Management For Developing CountriesJace BezzitNo ratings yet

- Capital Account Convertibility in Bangladesh v2Document32 pagesCapital Account Convertibility in Bangladesh v2Nahid HawkNo ratings yet

- 07 Chapter-2 PDFDocument35 pages07 Chapter-2 PDFkartikeya gulatiNo ratings yet

- RBI Speech On Capital Account ConvertibilityDocument12 pagesRBI Speech On Capital Account Convertibilitynisha vermaNo ratings yet

- Swaps 1Document25 pagesSwaps 1Leetika SharmaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2Document3 pagesLesson 2JuNo ratings yet

- International Finance: ObjectivesDocument32 pagesInternational Finance: ObjectivesNithyananda PatelNo ratings yet

- Benefits of The International Capital Market: Unit 5 SectionDocument4 pagesBenefits of The International Capital Market: Unit 5 SectionBabamu Kalmoni JaatoNo ratings yet

- Fixed To FloatDocument4 pagesFixed To FloatDaniela RicoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS AND TRADEDocument5 pagesChapter 10 INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS AND TRADEgian reyesNo ratings yet

- Week 9 SlidesDocument71 pagesWeek 9 SlidesHazardNo ratings yet

- International FinanceDocument207 pagesInternational FinanceAnitha Girigoudru50% (2)

- Financial GlobalizationDocument10 pagesFinancial GlobalizationAlie Lee GeolagaNo ratings yet

- GlobalizationDocument7 pagesGlobalizationNAITIK SHAHNo ratings yet

- Additional Learning Material GFEBDocument6 pagesAdditional Learning Material GFEBcharlenealvarez59No ratings yet

- C F E R: Ontext OF Oreign Xchange EgulationsDocument10 pagesC F E R: Ontext OF Oreign Xchange EgulationsrahluvNo ratings yet

- 1st Lecture - Introduction To International Finance-1Document42 pages1st Lecture - Introduction To International Finance-1HassaniNo ratings yet

- The Mundell-Fleming Model With Partial International Capital MobilityDocument22 pagesThe Mundell-Fleming Model With Partial International Capital MobilityHenok FikaduNo ratings yet

- Lec01 MncsDocument49 pagesLec01 MncsMuhammad Saqib AtaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 International Financial MarketsDocument29 pagesChapter 9 International Financial MarketsShivani SharmaNo ratings yet

- 022 Article A003 enDocument4 pages022 Article A003 enPratyush KumarNo ratings yet

- Currency Markets-2Document24 pagesCurrency Markets-2Nandini JaganNo ratings yet

- Contemporary World Module 1-2Document3 pagesContemporary World Module 1-2MARLO BARINGNo ratings yet

- Foreign Investment & Capital Flows: Unit HighlightsDocument20 pagesForeign Investment & Capital Flows: Unit HighlightsBivas MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- If GFCDocument70 pagesIf GFCBatool DarukhanawallaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To International FinanceDocument15 pagesIntroduction To International FinanceShivarajkumar JayaprakashNo ratings yet

- ch001Document36 pagesch001isuru anjanaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 & 4Document3 pagesChapter 3 & 4Rhea Lourel Nalam SalapaNo ratings yet

- Topic 1 - The Global EconomyDocument8 pagesTopic 1 - The Global EconomyedufocusedglobalNo ratings yet

- The Role of Free Zones in International StrategyDocument9 pagesThe Role of Free Zones in International StrategyErfanNo ratings yet

- Developing Countries and The Global Financial System: C H A P T e RDocument17 pagesDeveloping Countries and The Global Financial System: C H A P T e RAsniNo ratings yet

- 1.factors Influencing Foreign Direct Investment in Lesser Developed CountriesDocument9 pages1.factors Influencing Foreign Direct Investment in Lesser Developed CountriesAzan RasheedNo ratings yet

- Managerial Economics 2003 Visit Us at Management - UmakantDocument15 pagesManagerial Economics 2003 Visit Us at Management - Umakantwelcome2jungleNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - GlobalisationDocument53 pagesChapter 1 - GlobalisationTroll Nguyễn VănNo ratings yet

- Capital Flow Sustainability and Speculative Currency AttacksDocument4 pagesCapital Flow Sustainability and Speculative Currency AttacksAnonymous gitX9eu3pNo ratings yet

- Iberalization, Rivatization & LobalizationDocument25 pagesIberalization, Rivatization & LobalizationAnkit KhullarNo ratings yet

- Effects of Current and Capital Account ConvertibilityDocument4 pagesEffects of Current and Capital Account ConvertibilityNasrin LubnaNo ratings yet

- 1 IntroductionDocument26 pages1 IntroductionRicha ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Rohith U J - AssignmentDocument3 pagesRohith U J - AssignmentRohithNo ratings yet

- The Case Against Capital Controls: Financial Flows, Crises, and The Flip Side of The Free-Trade Argument, Cato Policy Analysis No. 403Document20 pagesThe Case Against Capital Controls: Financial Flows, Crises, and The Flip Side of The Free-Trade Argument, Cato Policy Analysis No. 403Cato Institute100% (1)

- Chapter 8 Trade and Investment PoliciesDocument3 pagesChapter 8 Trade and Investment PoliciesKristine PacalNo ratings yet

- International FinanceDocument206 pagesInternational FinanceAbigail StaffordNo ratings yet

- Globalisation: & Its EffectsDocument15 pagesGlobalisation: & Its EffectsDipanshu PathakNo ratings yet

- Quality of Domestic Financial Market and Capital InflowDocument33 pagesQuality of Domestic Financial Market and Capital InflowEvan OktavianusNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Good StandingsDocument5 pagesCertificate of Good StandingsRrichard Prieto MmallariNo ratings yet

- Representation On Behalf of The Complainants in The Sexual Harassment Case Against Ramakant Gundecha and Akhilesh GundechaDocument2 pagesRepresentation On Behalf of The Complainants in The Sexual Harassment Case Against Ramakant Gundecha and Akhilesh GundechaFirstpostNo ratings yet

- Contact List3Document7 pagesContact List3Vasu Deva GuptaNo ratings yet

- Government Response To Lori Loughlin Et Al.Document36 pagesGovernment Response To Lori Loughlin Et Al.Law&CrimeNo ratings yet

- Module 6 Part 1Document15 pagesModule 6 Part 1Sanal SamsonNo ratings yet

- System EngineeringDocument11 pagesSystem EngineeringAzure MidoriyaNo ratings yet

- Application - Form - ITM PGDM 2023 05461Document2 pagesApplication - Form - ITM PGDM 2023 05461mayank pethkarNo ratings yet

- Independent Civil ActionDocument25 pagesIndependent Civil ActionBimby Ali LimpaoNo ratings yet

- Turkish 1Document17 pagesTurkish 1Anonymous 6LcmPLfVV1No ratings yet

- RequiredDocument1 pageRequiredSalma amanyNo ratings yet

- Speech Before The Joint Session of The US Congress: Content and Contextual Analysis ofDocument15 pagesSpeech Before The Joint Session of The US Congress: Content and Contextual Analysis ofCyrus De LeonNo ratings yet

- 6 Commitment To Christ.6bd1858c2f20Document16 pages6 Commitment To Christ.6bd1858c2f20Ayaw LangNo ratings yet

- Revision QuestionsDocument3 pagesRevision QuestionsKA Mufas100% (1)

- University Malaysia Kelantan (UMK) : Course NameDocument18 pagesUniversity Malaysia Kelantan (UMK) : Course NameshobuzfeniNo ratings yet

- 1 5053319080065368338 PDFDocument114 pages1 5053319080065368338 PDFsardar bavaNo ratings yet

- AA025 Chapter AT9Document2 pagesAA025 Chapter AT9norismah isaNo ratings yet

- Senate SAFE Banking ActDocument30 pagesSenate SAFE Banking ActMarijuana MomentNo ratings yet

- Professional Deviance Doctors (LLM 211) (U 2, P 4)Document7 pagesProfessional Deviance Doctors (LLM 211) (U 2, P 4)sahil choudharyNo ratings yet

- Madunagu, Edwin (2016) Eskor Toyo and The Struggle For The Working PeoplesDocument12 pagesMadunagu, Edwin (2016) Eskor Toyo and The Struggle For The Working PeoplesNigeria Marx Library100% (1)