Professional Documents

Culture Documents

EHenry Deficienciesinauditingrptciia.2008.2.2

Uploaded by

Vincent ChuaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

EHenry Deficienciesinauditingrptciia.2008.2.2

Uploaded by

Vincent ChuaCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/247875111

Deficiencies in Auditing Related-Party Transactions: Insights from AAERs

Article in Current Issues in Auditing · December 2008

DOI: 10.2308/ciia.2008.2.2.A10

CITATIONS READS

40 1,242

4 authors, including:

Elaine Henry Brad Reed

Stevens Institute of Technology Southern Illinois University Edwardsville

72 PUBLICATIONS 1,714 CITATIONS 26 PUBLICATIONS 334 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Elizabeth A. Gordon

Temple University

39 PUBLICATIONS 1,277 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Quantitative Modeling of Unstructured Financial Information View project

Revenue Recognition and Sales Return Issues at Medicis Corporation View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Elaine Henry on 25 May 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Current Issues in Auditing American Accounting Association

Volume 2, Issue 2

2008

Pages A10–A16

Deficiencies in Auditing Related-Party

Transactions: Insights from AAERs

Timothy J. Louwers, Elaine Henry, Brad J. Reed, and Elizabeth A. Gordon

SUMMARY: After several high-profile frauds involving related-party transactions, regulators

have raised questions as to whether current auditing standards remain appropriate. In this

study, we examine 43 SEC enforcement actions against auditors related to the examination

of related-party transactions. We conclude that the audit failures in these fraud cases were

more the result of a lack of auditor professional skepticism and due professional care than

any deficiency in current auditing standards. In other words, revised auditing standards

would likely not have prevented these auditing failures, raising questions about the need

for auditing standard revision for related-party transactions at this time. Despite this finding,

we conclude with some suggestions to improve the auditing of related-party transactions,

such as including the discussion of related-party transaction abuse during SAS No. 99

mandated fraud awareness “brainstorming” sessions. 关DOI: 10.2308/ciia.2008.2.2.A10兴

INTRODUCTION

In the wake of several recent accounting frauds involving related-party transactions 共e.g.,

Adelphia, Enron, and Tyco兲, regulators have raised questions as to whether current auditing

standards remain appropriate. For example, the Chief Auditor of the Public Company Accounting

Oversight Board 共PCAOB兲 identified related-party transactions as an upcoming project for the

PCAOB 共PCAOB 2006兲. Given that related-party transactions are quite common1 and financial

statement frauds are quite rare,2 the incidence of frauds perpetrated with related-party transac-

tions is exceedingly rare.3 Henry et al. 共2007兲 examine 83 financial statement frauds that involved

related-party transactions and conclude that, while related-party transactions provide company

management with opportunities to commit fraud, their importance in a financial statement audit

should be considered in the context of management’s motivation and rationalization. The wide

variety of contexts in which related-party transactions occur suggests that, barring the presence of

Timothy J. Louwers is a Professor at James Madison University, Elaine Henry is an Assistant Professor at the University of

Miami, Brad J. Reed is an Associate Professor at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, and Elizabeth A. Gordon is an

Associate Professor at Temple University.

1

Gordon et al. 共2004兲 report that 80 percent of 112 companies studied in a pre-Sarbanes-Oxley period 共2000–2001兲 disclosed at

least one related-party transaction; similarly, a business press article reports that, in a post-Sarbanes-Oxley period 共2002–2003兲,

75 percent of the 400 largest U.S. companies disclosed one or more related-party transactions 共Emshwiller 2003兲.

2

Lev 共2003, 40兲 reports there were only about 100 federal class action lawsuits alleging accounting improprieties annually 共study

period 1996 to 2001兲, compared to the universe of over 15,000 companies listed on U.S. exchanges, and notes that “Overall, the

direct, case-specific evidence on the extent of earnings manipulation from fraud litigation, earnings restatements and SEC

enforcement actions suggest that such occurrences are relatively few in normal years.”

3

Other evidence 共e.g., Shapiro 1984; Bonner et al. 1998; SEC 2003兲 suggests that most frauds do not involve related-party

transactions. For example, an SEC 共2003兲 study of enforcement actions involving reporting violations during the period July 31,

1997 to July 30, 2002 found that only 23 共10 percent兲 of 227 enforcement cases involved failure to disclose related-party

transactions.

Submitted: 1 March 2008

Accepted: 14 April 2008

Published: 27 August 2008

Louwers, Henry, Reed, and Gordon A11

other fraud risk factors, related-party transactions may not warrant excessive additional audit

attention. While Henry et al. 共2007兲 focus on corporate frauds involving related-party transactions,

our focus is on audit failures4 involving related-party transactions. Specifically, we examine 43

SEC Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Releases 共AAERs兲, occurring from 1983 to 2006,

which detail SEC actions against external auditors for audit failures related to the examination of

related-party transactions.

We used keyword searches of AAERs on Lexis-Nexis to first locate frauds involving related-

party transactions and then examined the AAERs for mention of the public accounting firm con-

ducting the audit. We also include 12 cases identified in Beasley et al. 共2001兲 in which the alleged

audit deficiencies included failure to recognize or disclose related-party transactions. While we

found a total of 49 audit failures, six involved audit failures not involving the examination of

related-party transactions, resulting in a final sample size of 43.

Current auditing standards for the examination of related party-transactions specify a three-

step process that involves sequentially 共1兲 identifying related parties, 共2兲 examining related-party

transactions 共e.g., ascertaining business purpose兲, and 共3兲 ensuring proper disclosure of the

transactions. Challenges exist at each stage 共AICPA 2001兲. First, related parties and transactions

warranting examination may be difficult to identify because of the wide variety of parties and types

of transactions and the fact that some transactions may not be given accounting recognition 共e.g.,

receipt of free services from a related party兲. Second, examination of related-party transactions

can be complex, especially when the transactions involve difficult-to-value assets. In both cases,

auditors must often rely on management representations for information supporting identification

and valuation of related-party transactions. A third issue relates to the sequential process of the

audit procedures; if related parties are not identified, then the related-party transactions can

neither be examined nor disclosed.

Beasley et al. 共2001兲 report that failure to recognize and/or disclose key related parties was

one of the top ten audit deficiencies in a sample of 45 SEC enforcement actions between 1987

and 1997. In this study, we focus on audit failures that involve related-party transactions. The

motivation for our analysis is first to identify at which stage—identification, examination, or

disclosure—the audit failure occurred. Second, we aim to assess whether prescribed procedures5

appear to have been appropriately applied but audit failure resulted from some apparent defi-

ciency 共or omission兲 in the standards’ specification of necessary procedures, or, alternatively,

whether audit failure resulted from an apparent deficient application of the prescribed procedures.

We examined each enforcement action to identify the stage at which the audit failure occurred

and the circumstances surrounding the failure.6 Surprisingly, while the step of identifying related-

party transactions would seem to be the most difficult step in the process, we find that relatively

few audits 共six cases兲 appear to have failed at the identification stage 共see Table 1兲. Instead, we

find that the most common 共29 cases兲 alleged audit deficiency with respect to the related-party

4

Professional standards 共SAS No. 107, AICPA 2006兲 clarify the auditor’s responsibility: “In performing the audit, the auditor is

concerned with matters that, either individually or in the aggregate, could be material to the financial statements. The auditor’s

responsibility is to plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance that material misstatements, whether caused by

errors or fraud, are detected” 共AU 312.03兲. Thus, Kadous 共2000, 327兲 defines audit failure as an auditor issuing “an unqualified

opinion on financial statements that are subsequently found to have been materially misstated.”

5

We use the term “procedures” to refer to the audit “procedures that should be considered by the auditor when he is performing

an audit of financial statements in accordance with generally accepted auditing standards to identify related-party relationships

and transactions and to satisfy himself concerning the required financial statement accounting and disclosure” 共SAS No. 45.01,

AICPA 1983兲.

6

Two members of the author team have significant audit experience and a third has internal audit experience. The classification

process was straightforward and no differences among classifications were noted.

Current Issues in Auditing Volume 2, Issue 2, 2008

American Accounting Association

Louwers, Henry, Reed, and Gordon A12

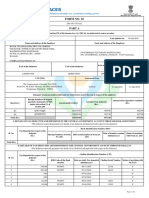

TABLE 1

Analysis of Audit Failures by Auditor Size

Stage of Audit Failure Big 4 Non-Big 4 Firm Sole Practitioner Total

Identification of related-party transaction 0 3 3 6

Examination of related-party transaction 1 22 6 29

Disclosure of related-party transaction 4 4 0 8

Total 5 29 9 43

transaction involved inadequate examination of the transaction 共e.g., ascertaining its business

purpose兲. The remainder 共eight cases兲 involved failures related to inadequate disclosure. Thus, 86

percent 共37 of the 43 cases兲 of the audit failures occurred after the related parties had been

identified.

Table 1 provides a breakdown of AAERs by audit firm size. Table 1 classifies audit firm size

into three categories: Big 4 firms,7 non-Big 4 firms, and sole practitioners. Five of the 43 共12

percent兲 cases involve a Big 4 firm, 29 共67 percent兲 cases involve a non-Big 4 firm, and 9 共21

percent兲 involve sole practitioners. There are two interesting points to be noted from Table 1. First,

of the five cases that involve Big 4 firms, four involve failure at the disclosure stage. While Big 4

firms account for only 12 percent of the total cases, Big 4 firms account for 50 percent of the

disclosure stage failures. Second, compared to Beasley et al. 共1999, 37, Table 16兲, which found

that 65 percent of the auditors in their broader sample of AAERs were non-Big 4 auditors, we find

88 percent of our sample are non-Big 4 auditors. Although these small samples do not lend

themselves to rigorous statistical analysis, audit failures in AAERs involving related-party trans-

actions appear to be more likely to involve smaller audit firms than are audit failures in AAERs in

general. The following sections document comments from SEC enforcement actions from which

we identified the point at which the auditing of related-party transactions were found to be defi-

cient.

Failures to Identify Related Parties and Related-Party Transactions

In six cases, five of which are described below, the audits appear to have failed at the point of

identification; in other words, related parties existed that the auditors failed to identify 共despite

readily available information兲.8

• International Teledata: The auditors knew shares had been issued 共the issuance was

footnoted in the financial statements兲, but they failed to sufficiently review the board

minutes and failed to make inquiries to determine to whom the shares had been is-

sued. Had they performed these basic procedures, the auditors would have discovered

that 共in addition to not being authorized by the board兲 most of the stock issued “went to

related parties in exchange for inadequate consideration.”

• Pacific Waste: Although the auditors claimed that management had represented that

there were no related-party transactions, the SEC’s action noted that there were at

7

The term “Big 4” refers collectively not only to the current Big 4 firms 共Deloitte, Ernst & Young, KPMG, and Pricewaterhouse-

Coopers兲, but also to those firms’ predecessors known as the Big 6 and Big 8 firms over the time period examined. Arthur

Andersen was also part of the Big 6/Big 8.

8

All quotes are taken from AAERs retrieved from Lexis-Nexis.

Current Issues in Auditing Volume 2, Issue 2, 2008

American Accounting Association

Louwers, Henry, Reed, and Gordon A13

least five documents in the auditors’ files showing that the company’s president was

also an officer, director, and controlling shareholder of the investee-company used to

perpetrate the financial statement fraud.

• Softpoint and Pantheon: The auditor used the Softpoint’s fax machine and a fax num-

ber provided by the client for confirmations. Similarly, in the case of Pantheon, the

auditor used the fax number provided by the client even though the SEC action notes

the number differed from that shown in the banking directory located in the audit files.

The inference is that had the auditors independently verified the fax numbers provided,

they would have 共a兲 identified fictitious sales to three companies owned by Softpoint’s

president and chairman and 共b兲 identified the forged notes that had been purchased

with private funding from Pantheon’s top executives, respectively.

• Tri-Comp Sensors: The auditors knew loans existed, but did not think they were

related-party transactions. However, the SEC action cites various red flags that should

have indicated the transactions were with related parties, such as: “共1兲 the loan was a

large isolated transaction made immediately upon the closing of Sensors’ initial public

offering and constituting almost a quarter of the net offering proceeds; 共2兲 no interest

was paid on the loan; and 共3兲 there was no written agreement or record documenting

the loan terms or purpose.”

Inadequate Examinations of Related-Party Transactions

We classify enforcement actions against auditors as an audit failure at the examination stage

if it is stated in the enforcement action that the auditors either knew of, or it can be inferred from

the case details that the auditors should have known about, the related-party transaction. Of the

43 enforcement actions against the auditors, 29 involve auditors’ examinations of the related-party

transactions. Brief summaries and representative examples follow.

• Two examples illustrate situations in which identification of the related-party transac-

tions was unavoidable; however, the auditor did not perform any audit procedures on

the related-party transactions. In the case of Atratech, the top executive instructed the

independent auditor to “recast the book entries for transactions between two subsid-

iaries from ‘related-party receivables’ to ‘accounts receivables’ as part of concealing

the relationship.” In the case of Novaferon, the SEC noted that the company’s “finances

were not separable from the finances of four other entities which were under common

control with Novaferon.” The SEC’s action also noted the company “maintained virtu-

ally no normal business or accounting records susceptible of audit. The company’s

books consisted primarily of a check register.”

• PNF Industries illustrates a case where the auditor performed some testing of the

related-party transaction, but the testing lacked rigor. While the auditors of PNF Indus-

tries had identified and questioned payments to a related party, they were given ficti-

tious supporting records, including fabricated board meeting minutes. The records,

however, contained numerous inconsistencies proving that they were fictitious, includ-

ing references to information that was not known until months after the date on the

records. The SEC action stated: “Because this was a material related-party transaction

involving … a convicted felon, 关the auditors兴 should have closely scrutinized the evi-

dence supporting 关the individual’s兴 expenses. Nevertheless, 关the auditor兴 failed to re-

view the evidence obtained and therefore failed to consider whether the minutes had

been fabricated.”

Current Issues in Auditing Volume 2, Issue 2, 2008

American Accounting Association

Louwers, Henry, Reed, and Gordon A14

• The cases of Great American and Itex illustrate audit inadequacies with respect to

valuing assets obtained in related-party transactions. The auditor of Great American

was cited for having inappropriately relied on management’s representations about the

values of a fictitious patent and a race horse, both acquired from officers of the com-

pany. The company reported a value of $225,000 for patents that did not exist and a

value of $1.1 million for a race horse which “had total lifetime race earnings of $1,000,

earned stud fees of less than $1,000, and been recently purchased by the persons who

contracted to sell it to Great American for only $5,000.” The Itex audit failure occurred

despite a number of red flags about both the transactions and the asset appraisals,

including the fact that “certain significant transactions occurred at or near the end of

fiscal periods, involved unusual purchases, sales, and repurchases of assets within a

short period of time, and a series of transactions involving an offshore entity whose

sole address was a post office box in Belize, Central America.”

• Illustrations of audit failures involving receivables from related parties include MCA

Financial and General Tech. For MCA Financial, had the auditors reviewed the financial

statements of the related party, they would have concluded the receivables could not

be repaid from the related party’s cash flow. Additionally, to assess whether the receiv-

ables could be repaid by liquidating the underlying collateral 共most of which had been

acquired from MCA兲, the auditors relied on “estimated fair market values provided by

management” and also on “property appraisals performed by the brother-in-law of

MCA’s CEO while employed by a company that the auditors listed as an MCA

subsidiary.”9 With respect to General Tech’s audit deficiencies, the SEC’s action noted

that all of the company’s “accounts receivables appeared on computer-generated aged

receivable listings, except for the receivables for five related parties that were simply

handwritten in at the bottom of those computer listings; despite the manner in which

those five were recorded, 关the兴 audit staff did not perform any audit work with respect to

them.”

Improper Disclosures of Related-Party Transactions

Of the 43 enforcement actions against auditors, we identify eight cases that we classify as

failures at the step of ensuring adequate disclosure. In each of the eight cases, there appears to

be little doubt about the auditor’s identification of the related-party transaction, and given the

details provided, little likelihood that the auditor failed to examine the transactions. Two represen-

tative examples follow.

• In the audit of Madera, the SEC action states the auditors were aware of consulting

agreements with officers and directors, but failed to insist that management disclose

them in the footnotes to the financial statements. The transactions were identified as

related-party transactions in the audit plan, copies of the consulting agreements were

in the audit files, and the auditors were aware that the company had issued stock to the

consultants. The most incriminating evidence, however, was the fact that the audit

manager noted in his review notes on Madera’s Form 10-K to “disclose consulting fees

as related-party transactions.”

• The SEC’s action against Adelphia’s auditors highlighted numerous disclosure defi-

ciencies. First, Adelphia was jointly and severally liable for co-borrowings with a related

9

The auditors had specifically noted in the workpapers that this appraiser was a “Related Entity.”

Current Issues in Auditing Volume 2, Issue 2, 2008

American Accounting Association

Louwers, Henry, Reed, and Gordon A15

party 共the Rigas family兲 and thus should have reported the liability. The SEC action

notes that during the audit, the company’s auditor “repeatedly proposed disclosure of

the full amount of the Co-Borrowing debt. 关The auditing firm兴 inserted more explicit

disclosure, including the amount of Rigas Co-Borrowing debt, in at least six drafts of

Adelphia’s 2000 Form 10-K. But when Adelphia’s management resisted, 关the auditing

firm兴 abandoned its attempts to make the disclosure more accurate.” A second disclo-

sure deficiency was the improper netting of related-party receivables and payables.

Adelphia netted $1.351 billion related-party receivables against $1.348 billion related-

party payables to show only $3 million net receivables on its balance sheet; the netting

practice concealed the extent of related-party transactions between the company and

the Rigas family and was characterized by the SEC as “a fraudulent device used to

conceal its liabilities.” The SEC action against the auditor states that “Adelphia was

required both by GAAP and by Commission regulations to report related-party trans-

actions with the Rigas Entities in a gross presentation.” A third disclosure deficiency

was broader. The SEC action against the auditors noted that Adelphia and the related-

party companies shared a cash management system 共CMS兲 and “the general ledger

recorded the thousands of intercompany transactions among and between Adelphia

subsidiaries and Rigas Entities. A review of bank statements would have shown that

cash receipts for both public and private entities were deposited into Adelphia’s First

Union CMS account and that disbursements on behalf of public and private entities

were paid from that same account.” However, the required disclosure of related-party

transactions was inadequate.

CONCLUSIONS

A combination of factors makes the examination of related-party transactions difficult. Unco-

operative 共or deceptive兲 clients make the task even more daunting. Numerous SEC enforcement

actions—against corporate executives, though not against their auditors—cite specific instances

in which management concealed information from its auditors. For example, in an action against

executives of Enron Broadband Services 共EBS兲 for a sham monetization transaction designed to

inflate earnings by $111 million, the SEC complaint alleges the executives “intentionally misled

Enron’s auditor 关Arthur Andersen兴 about the true character of the 关transaction兴 because they

believed that Andersen would not approve of the transaction or allow EBS to record any revenues

had Andersen known the truth.” As another example, the SEC’s complaint against Rite Aid’s top

executives states they provided their auditors with management representation letters containing

numerous false statements, including, “Related-party transactions have been properly recorded

or disclosed in the financial statements.”

Despite these challenges, our study identifies relatively few 共less than 50 in total兲 SEC en-

forcement actions against auditors for negligent identification, examination, or disclosure of

related-party transactions. With respect to the failure to identify related parties, although there

may be other unidentified contributory factors at work, it appears that the auditors may have

identified the related parties had they maintained their professional skepticism. Similarly, failure to

maintain professional skepticism appears to underlie auditors’ willingness to accept management

representations that identified related-party transactions had legitimate business purposes or that

assets acquired were properly valued. Finally, in the cases involving failures to adequately dis-

close related-party transactions, auditors appear to have acquiesced to management’s requests

to conceal 共or obfuscate the appropriate disclosure of兲 related-party transactions. Our review of

Current Issues in Auditing Volume 2, Issue 2, 2008

American Accounting Association

Louwers, Henry, Reed, and Gordon A16

these actions suggests the audit failures were more the result of a lack of professional skepticism

and due professional care rather than a failure of the audit procedures themselves.

Despite the fact that our examination does not reveal particular additions or modifications that

would improve procedures as currently prescribed for use in auditing related-party transactions,

these cases do offer some insights that might contribute to improved audit practices. Primarily,

audit teams should discuss the potential for related-party transaction abuse during their fraud

awareness “brainstorming” sessions required by SAS No. 99 共AICPA 2002兲. These discussions

among audit team members could include example AAERs such as the ones described above. In

addition, the AICPA publishes a “Related-Party Transactions Toolkit” 共AICPA 2001兲 that provides

more specific guidance, checklists, confirmation templates, and other tools that may assist the

audit team. Most importantly, as illustrated by these AAERs, the importance of maintaining pro-

fessional skepticism and exercising due professional care can never be overemphasized.

REFERENCES

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants 共AICPA兲. 1983. Omnibus Statement on Auditing Standards—1983.

Statement on Auditing Standards No. 45. New York, NY: AICPA.

——–. 2001. Accounting and Auditing for Related-Party Transactions: A Toolkit for Accountants and Auditors. New

York, NY: AICPA.

——–. 2002. Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit. Statement on Auditing Standards No. 99. New

York, NY: AICPA.

——–. 2006. Audit Risk and Materiality in Conducting an Audit. Statement on Auditing Standards No. 107. New York,

NY: AICPA.

Beasley, M. S., J. V. Carcello, and D. R. Hermanson. 1999. Fraudulent Financial Reporting: 1987–1997: An Analysis

of U.S. Public Companies. New York, NY: Committee of Sponsoring Organizations.

——–, ——–, and ——–. 2001. Top 10 audit deficiencies: SEC sanctions. Journal of Accountancy 191 共4兲: 63–67.

Bonner, S., Z-V. Palmrose, and S. Young. 1998. Fraud type and auditor litigation: An analysis of SEC Accounting and

Auditing Enforcement Releases. The Accounting Review 73 共October兲: 503–532.

Emshwiller, J. 2003. Business ties: Many companies report transactions with top officers. Wall Street Journal共De-

cember 29兲: A1.

Gordon, E. A., E. Henry, and D. Palia. 2004. Related party transactions and corporate governance. Advances in

Financial Economics 9: 1–28.

Henry, E., E. Gordon, B. Reed, and T. Louwers. 2007. The role of related-party transactions in fraudulent financial

reporting. Working paper, University of Miami.

Kadous, K. 2000. The effects of audit quality and consequence severity on juror evaluations of auditor responsibility

for plaintiff losses. The Accounting Review 75 共3兲: 327–341.

Lev, B. 2003. Corporate earnings: Fact and fiction. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 17 共2兲: 27–50.

Public Company Accounting Oversight Board 共PCAOB兲. 2006. Prepared Statement By Chief Auditor Thomas Ray on

2007 Standards-Setting Priorities. Standing Advisory Group Meeting. October 5. Available at: http://pcaobus.org/

standards/standing_advisory_group/meetings/2006/10-05/standards_setting.pdf.

Securities and Exchange Commission 共SEC兲. 2003. Report Pursuant to Section 704 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of

2002. Washington, D.C.: SEC. Available at: http://www.sec.gov/news/studies/sox704report.pdf.

Shapiro, S. 1984. Wayward Capitalists: Targets of the Securities and Exchange Commission. New Haven, CT and

London, U.K.: Yale University Press.

Current Issues in Auditing Volume 2, Issue 2, 2008

American Accounting Association

View publication stats

You might also like

- Corporate Security Organizational Structure, Cost of Services and Staffing Benchmark: Research ReportFrom EverandCorporate Security Organizational Structure, Cost of Services and Staffing Benchmark: Research ReportNo ratings yet

- Auditing Peecher, Schwartz, Solomon 2007Document23 pagesAuditing Peecher, Schwartz, Solomon 2007dittaNo ratings yet

- Drivers of Audit Failures A Comparative DiscourseDocument6 pagesDrivers of Audit Failures A Comparative DiscourseInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance and Accounting Scandals: Anup Agrawal and Sahiba Chadha University of AlabamaDocument42 pagesCorporate Governance and Accounting Scandals: Anup Agrawal and Sahiba Chadha University of AlabamaRafay HasnainNo ratings yet

- Impact Code of Ethics To IaDocument25 pagesImpact Code of Ethics To Iahafizie07No ratings yet

- Plumlee & Yohn - 2010 - An Analysis of The Underlying Causes of Attributed To RestatementsDocument25 pagesPlumlee & Yohn - 2010 - An Analysis of The Underlying Causes of Attributed To Restatementsall_xthegreatNo ratings yet

- Related Party Transactions in Corporate Governance PDFDocument60 pagesRelated Party Transactions in Corporate Governance PDFfauziahNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document57 pagesChapter 3Marco RegunayanNo ratings yet

- The Auditor's Going-Concern Opinion Decision: January 2007Document14 pagesThe Auditor's Going-Concern Opinion Decision: January 2007Nguyễn Thị Thanh TâmNo ratings yet

- ContentServer 7 PSDocument27 pagesContentServer 7 PSmuhromNo ratings yet

- The Role of Related Party Transactions in Fraudulent Financial ReportingDocument47 pagesThe Role of Related Party Transactions in Fraudulent Financial ReportingShamsulfahmi ShamsudinNo ratings yet

- CG PDFDocument23 pagesCG PDFZulfaneri PutraNo ratings yet

- What Auditors Do The Scope of AuditDocument11 pagesWhat Auditors Do The Scope of AuditAylan AminNo ratings yet

- Mark - Beasley@ncsu - Edu Jcarcell@utk - Edu: WWW - Sec.gov/enforce - HTMDocument7 pagesMark - Beasley@ncsu - Edu Jcarcell@utk - Edu: WWW - Sec.gov/enforce - HTMRengeline LucasNo ratings yet

- Audit Reporting For Going Concern PDFDocument33 pagesAudit Reporting For Going Concern PDFclarensia100% (1)

- Financial Statement Frauds and Auditor Sanctions An Analysis of Enforcement Actions in ChinaDocument15 pagesFinancial Statement Frauds and Auditor Sanctions An Analysis of Enforcement Actions in ChinaIchbinleo100% (2)

- Honesty and Business Ethics in The Accounting Profession: August 1979Document12 pagesHonesty and Business Ethics in The Accounting Profession: August 1979sizzunsNo ratings yet

- Chapters SummaryDocument13 pagesChapters SummarymorrisNo ratings yet

- Advances in Accounting: Hsihui Chang, L.C. Jennifer Ho, Zenghui Liu, Bo OuyangDocument16 pagesAdvances in Accounting: Hsihui Chang, L.C. Jennifer Ho, Zenghui Liu, Bo OuyangRusli RusliNo ratings yet

- Data-Driven Auditing: A Predictive Modeling Approach To Fraud Detection and ClassificationDocument19 pagesData-Driven Auditing: A Predictive Modeling Approach To Fraud Detection and ClassificationNitin SinghNo ratings yet

- Ky 20211017234614Document23 pagesKy 20211017234614Nguyen Quang PhuongNo ratings yet

- Unit Two: Auditing Profession and GAASDocument90 pagesUnit Two: Auditing Profession and GAASeferemNo ratings yet

- C9ay1 HsijbDocument15 pagesC9ay1 HsijbEyob FirstNo ratings yet

- DefondDocument17 pagesDefondLaksmi Mahendrati DwiharjaNo ratings yet

- Are Non-Audit Fees Associated With Restated Financial Statements? Initial Empirical EvidenceDocument14 pagesAre Non-Audit Fees Associated With Restated Financial Statements? Initial Empirical Evidenceahmed sharkasNo ratings yet

- What Factors Drive Low Accounting Quality? An Analysis of Firms Subject To Adverse Rulings by The Financial Reporting Review PanelDocument50 pagesWhat Factors Drive Low Accounting Quality? An Analysis of Firms Subject To Adverse Rulings by The Financial Reporting Review Panelshaafici aliNo ratings yet

- Audit Expectation GapDocument17 pagesAudit Expectation GapWong Bw50% (2)

- Process Mining of Event Logs in Internal AuditingDocument31 pagesProcess Mining of Event Logs in Internal Auditinghoangnguyen7xNo ratings yet

- Kohlbeck2017 Are Related Party Transactions Red FlagsDocument40 pagesKohlbeck2017 Are Related Party Transactions Red Flagskelas cNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2Document20 pagesLecture 2FiruzaNo ratings yet

- Thomson - Risk Rating The Audit UniverseDocument10 pagesThomson - Risk Rating The Audit UniversepradanyNo ratings yet

- Fraud and ForensikDocument8 pagesFraud and ForensikNia NuristiyantiNo ratings yet

- Case 1.1 ENRONDocument3 pagesCase 1.1 ENRONSheren VerenNo ratings yet

- A Survey of Governance Disclosures Among U.S. Firms: Lori Holder-Webb Jeffrey Cohen Leda Nath David WoodDocument21 pagesA Survey of Governance Disclosures Among U.S. Firms: Lori Holder-Webb Jeffrey Cohen Leda Nath David Woodsajid gulNo ratings yet

- Firm Urn NBN Si Doc-Hrqml0niDocument15 pagesFirm Urn NBN Si Doc-Hrqml0nielikaNo ratings yet

- Salehi - 2011 - Audit Expectation Gap - Concept, Nature and TraceDocument17 pagesSalehi - 2011 - Audit Expectation Gap - Concept, Nature and TracethoritruongNo ratings yet

- 16 Oaijse Ethical Issues of Financial ReportingDocument5 pages16 Oaijse Ethical Issues of Financial ReportingRam PrakashNo ratings yet

- The Role of Auditors With Their Clients and Third PartiesDocument45 pagesThe Role of Auditors With Their Clients and Third PartiesInamul HaqueNo ratings yet

- The ValuntaryDocument29 pagesThe ValuntarylovebilaNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance and Accounting Scan PDFDocument36 pagesCorporate Governance and Accounting Scan PDFabdallah ibraheemNo ratings yet

- SeekingmisconductDocument61 pagesSeekingmisconductconrade chenNo ratings yet

- Financial Statement Fraud Control Audit Testing and Internal Auditing Expectation GapDocument7 pagesFinancial Statement Fraud Control Audit Testing and Internal Auditing Expectation GapRia MeilanNo ratings yet

- Raising The Bar On CGIDocument56 pagesRaising The Bar On CGISarfraz AliNo ratings yet

- This Download For The Software Is Used For Educational Purposes For BA8018 Professional AuditingDocument11 pagesThis Download For The Software Is Used For Educational Purposes For BA8018 Professional Auditingreshva10No ratings yet

- Fraud Detection, Redress and Reporting by Auditors: Managerial Auditing Journal October 2010Document22 pagesFraud Detection, Redress and Reporting by Auditors: Managerial Auditing Journal October 2010Fred The FishNo ratings yet

- Corporate GovernanceDocument22 pagesCorporate GovernancesawNo ratings yet

- Auditors Gone Wild The 'Other' Problem in Public Accounting 2008 Business HorizonsDocument11 pagesAuditors Gone Wild The 'Other' Problem in Public Accounting 2008 Business HorizonsiportobelloNo ratings yet

- How Do Various Forms of Auditor Rotation Affect Audit Quality? Evidence From ChinaDocument30 pagesHow Do Various Forms of Auditor Rotation Affect Audit Quality? Evidence From ChinahalvawinNo ratings yet

- F.2. Audit Fees and Investor PerceptionDocument34 pagesF.2. Audit Fees and Investor PerceptionintanNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance An Ethical PerspectiveDocument37 pagesCorporate Governance An Ethical PerspectiveMunib HussainNo ratings yet

- Relationships Among Components of Engagement RiskDocument13 pagesRelationships Among Components of Engagement RiskMark BryanNo ratings yet

- Are Related Party Transactions Red Flags?Document52 pagesAre Related Party Transactions Red Flags?BhuwanNo ratings yet

- Christensen PDFDocument50 pagesChristensen PDFLizzy MondiaNo ratings yet

- Topic 3 The Scope of Operational AuditDocument4 pagesTopic 3 The Scope of Operational AuditPotato Commissioner100% (1)

- Khudhair - The Effect of Board Characteristics and Audit Committee Characteristics On Audit QualityDocument12 pagesKhudhair - The Effect of Board Characteristics and Audit Committee Characteristics On Audit QualityyaiyalahNo ratings yet

- Pourali (2013)Document6 pagesPourali (2013)Dhira Syenna AnindittaNo ratings yet

- Ajaer. 3. 3. 2014. 269-277Document9 pagesAjaer. 3. 3. 2014. 269-277Hermawan AndriantoNo ratings yet

- Chapters PagesDocument32 pagesChapters PagesNurul FajriyahNo ratings yet

- AOSPreprintDocument17 pagesAOSPreprintIrma HarrietNo ratings yet

- Các chỉ số ảnh hưởng chỉ số môi trường đầu tưDocument13 pagesCác chỉ số ảnh hưởng chỉ số môi trường đầu tưK59 Nguyen Dang VuNo ratings yet

- MarketWars Case StudyDocument15 pagesMarketWars Case StudyABILESH R 2227204No ratings yet

- Applied Auditing 2017 Answer Key PDFDocument340 pagesApplied Auditing 2017 Answer Key PDFcezyyyyyy50% (2)

- A Summer Training Report IN Marketing Strategies AT Pepsico India Pvt. LTDDocument8 pagesA Summer Training Report IN Marketing Strategies AT Pepsico India Pvt. LTDJaydeep KushwahaNo ratings yet

- Ducati Valuation - LPDocument11 pagesDucati Valuation - LPuygh gNo ratings yet

- Chap 13Document18 pagesChap 13N.S.RavikumarNo ratings yet

- Justdial SWOTDocument2 pagesJustdial SWOTweedemboy9393No ratings yet

- Principles of Marketing Kotler 15th Edition Solutions ManualDocument32 pagesPrinciples of Marketing Kotler 15th Edition Solutions ManualShannon Young100% (33)

- Financial Accounting Theory: Sixth William R. ScottDocument32 pagesFinancial Accounting Theory: Sixth William R. Scottanon_757820301No ratings yet

- Executive SummaryDocument56 pagesExecutive Summarybooksstrategy100% (1)

- Servuction ModelDocument5 pagesServuction Modelrajendrakumar88% (8)

- Capstone - Upgrad - Himani SoniDocument21 pagesCapstone - Upgrad - Himani Sonihimani soni100% (1)

- Jaipur National University: Dainik Bhaskar Jid Karo Duniya BadloDocument33 pagesJaipur National University: Dainik Bhaskar Jid Karo Duniya BadloAkkivjNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2: Analyzing The Business Case: Kp24103 System Analysis & DesignDocument17 pagesChapter 2: Analyzing The Business Case: Kp24103 System Analysis & DesignMae XNo ratings yet

- Ssab 2022Document187 pagesSsab 2022Megha SenNo ratings yet

- MSC PSCM Changalima, I.A 2016Document91 pagesMSC PSCM Changalima, I.A 2016Samuel Bruce RocksonNo ratings yet

- Insurance in Bangladesh AssignmentDocument24 pagesInsurance in Bangladesh AssignmentmR. sLim88% (8)

- 2023 Internal Audit Plan For The CrewDocument4 pages2023 Internal Audit Plan For The CrewLateef LasisiNo ratings yet

- World Investor NZDocument72 pagesWorld Investor NZAcorn123No ratings yet

- Form16-2018-19 Part ADocument2 pagesForm16-2018-19 Part AMANJUNATH GOWDANo ratings yet

- DayTrade Gaps SignalsDocument30 pagesDayTrade Gaps SignalsJay SagarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5Document20 pagesChapter 5Clyette Anne Flores Borja100% (1)

- Uber Case StudyDocument16 pagesUber Case StudyHaren ShylakNo ratings yet

- Lecture 9-Managing R & D ProjectsDocument15 pagesLecture 9-Managing R & D ProjectsMohammed ABDO ALBAOMNo ratings yet

- IMPACT OF AI (Artificial Intelligence) ON EMPLOYMENT: Nagarjuna V 1NH19MCA40 DR R.SrikanthDocument24 pagesIMPACT OF AI (Artificial Intelligence) ON EMPLOYMENT: Nagarjuna V 1NH19MCA40 DR R.SrikanthNagarjuna VNo ratings yet

- Tax Case StudyDocument6 pagesTax Case StudyAditi GuptaNo ratings yet

- Mahila Samman Savings Certificate 2023 - FAQsDocument3 pagesMahila Samman Savings Certificate 2023 - FAQsketanaurangabad3733No ratings yet

- HL Business Management Course Outline - FinalDocument14 pagesHL Business Management Course Outline - FinalAnthony QuanNo ratings yet

- Growth, Poverty, and Income Distribution PovertyDocument6 pagesGrowth, Poverty, and Income Distribution PovertyMija DiroNo ratings yet

- MATRIX Hervás-Oliver, J. L., Parrilli, M. D., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Sempere-Ripoll, F. (2021)Document7 pagesMATRIX Hervás-Oliver, J. L., Parrilli, M. D., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Sempere-Ripoll, F. (2021)Wan LinaNo ratings yet

- Digital India in Agriculture SiddhanthMurdeshwar NMIMS MumbaiDocument4 pagesDigital India in Agriculture SiddhanthMurdeshwar NMIMS MumbaisiddhanthNo ratings yet