Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Review of Silent Urns: Romanticism, Hellenism, Modernity

Uploaded by

mercedesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Review of Silent Urns: Romanticism, Hellenism, Modernity

Uploaded by

mercedesCopyright:

Available Formats

Review

Reviewed Work(s): Silent Urns: Romanticism, Hellenism, Modernity by David Ferris

Review by: Jennifer Wallace

Source: Modern Philology , Vol. 101, No. 4 (May 2004), pp. 630-633

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/423647

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Modern Philology

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.115 on Wed, 15 Feb 2023 18:19:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

630 MODERN PHILOLOGY

and the law courts. His close readings are uniformly interesting and

complex, and, taken together, they represent a new and illuminating

contribution to the history of the novel as well as to the field of law

and literature.

Kieran Dolin

University of Western Australia

Silent Urns: Romanticism, Hellenism, Modernity. David Ferris. Stan-

ford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2000. Pp. xix+247.

“We are always talking of the Greeks and Romans—they never said

anything of us,” quipped William Hazlitt in 1816. 1 In a way, of course,

he was right. The work of the younger generation of Romantic writ-

ers was dominated by contemporary images of ancient Greece—

drawn from travel narratives, recently acquired sculpture collections,

or newly translated classical texts—which silenced their subject matter

and erased the historical context of its depictions. William Haygarth’s

picture of nineteenth-century travelers admiring the Athenian acrop-

olis in an empty landscape stripped of modern inhabitants (Greece

[1814]) is a typical example. But, in another sense, Hazlitt was wrong,

given the complexity of the relationship between antiquity and mo-

dernity in the early nineteenth century. The way that the Romantics

constructed the ancient Greeks in their imaginations actually often

served to silence them (take a look at Henry Fuseli’s striking sketch

The Artist in Despair over the Magnitude of Ancient Fragments [ca. 1770–

80]) and they either internalized their own idealizations or struggled

self-consciously to resist the prevailing philhellene ideology. “The

Greeks,” in other words, as reimagined in the late eighteenth century,

could respond to the legacy of the Romantics.

David Ferris confronts the complicity between classical antiquity and

early nineteenth-century Romanticism in no uncertain terms. He main-

tains that historians have been guilty either of idealizing ancient Greece

and emphasizing its beauty or of mercilessly debunking its mystique

and eschewing its aesthetic in favor of a politicized or historicized

picture. Instead, he argues, critics should explore the historical pro-

cesses by which the aesthetic account of Greece came to predominate

in the late eighteenth century and thus reach an understanding of the

1. William Hazlitt, review of Lectures on Dramatic Literature, by Friedrich von Schlegel,

in Selected Writings, ed. Duncan Wu, 9 vols. (London: Pickering and Chatto, 1998), 1:279.

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.115 on Wed, 15 Feb 2023 18:19:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Book Reviews 631

connections between aesthetics and history in our culture today. This

argument holds implications for new historicist criticism, which seeks

to replace aesthetics with history, and Ferris engages pugnaciously with

the work of Jerome McGann, Marjorie Levinson, and others through-

out the book.

At the heart of the Romantic hellenic movement, Ferris places the

work of Johann Winckelmann. He argues that in History of Ancient Art

(1764), Winckelmann drew on the Greek example to make a wider

claim about the function of the aesthetic in the history of any culture.

Winckelmann’s writing about Greece thus becomes crucially impor-

tant not just for the study of Hellenism, but also for our understand-

ing of Romantic culture and modernity: “It is more profitable to read

Winckelmann’s History of Ancient Art as the production of a sense of

history for modernity, a sense articulated through a system that takes

the name of Greece” (p. 23). The hallmarks of Winckelmann’s aes-

thetics for Ferris are, not surprisingly, familiar Romantic terms: fail-

ure, inimitability, fragmentation. The “failure” of modern writers to

imitate the Greeks, to turn art objects into words, to describe ade-

quately missing works of Greek art becomes itself aestheticized, so that

modern historical consciousness is the product of ahistorical idealiza-

tion. This argument leads to some tortuous, paradoxical tongue-and-

mind twisters: “The History of Ancient Art is an account of how the

failure of a concept of the aesthetic becomes the sign of what the con-

cept failed to account for” (p. 34).

Having set the terms for his notion of Hellenism through an analysis

of Winckelmann, Ferris proceeds to a reading of seminal poems by

John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Friedrich Hölderlin. Keats’s “On

First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” (1817) is read as an oscillation

between “looking” and “breathing” or, by extension, between respond-

ing to the visual legacy of Greece and substituting that with reading

texts, with history. This oscillation, Ferris argues convincingly, leads to

a disorientation that parallels the dislocation of translation or the

“swimming” into view of a new planet: “Antiquity, rather than being

the return of what is old, is presented by Keats as the arrival of the

not yet known, the new, the modern” (p. 74). Ferris’s interpretation

of Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound (1820) revolves around his reading of

Prometheus’s attempted revocation of his curse. In that moment, Pro-

metheus proves that judgment is always caught up in history and that

to attempt to free Greece from its past in fact binds the modern writer

to Hellenic ideology: “To be so unbound is to be bound to the myth

of Prometheus” (p. 157).

The difficulty with Ferris’s book is its emphasis on Winckelmann and

other German writers—Friedrich Schelling, Immanuel Kant, G. W. F.

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.115 on Wed, 15 Feb 2023 18:19:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

632 MODERN PHILOLOGY

Hegel—for a reading of British Romantic Hellenism. It is not clear how

well Keats or even the better-read Shelley knew the work of Winckel-

mann, much less the other writers. Mary Shelley records in her jour-

nal that Shelley read a French translation of History of Ancient Art in

late December 1818 and early January 1819, but there is no record of

him actually reading Schelling or Hegel or other Winckelmann texts.

At the time Keats and Shelley were writing, only Winckelmann’s Re-

flections on the Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks had been translated

into English (by Fuseli in 1765); the History of Ancient Art was not trans-

lated into English until 1850. While his work did filter through into

cultural discourse through indirect means—through Fuseli, through the

translation of Friedrich von Schlegel’s lectures on tragedy—it was off-

set by many other, more concrete versions of the Hellenic aesthetic

reaching Britain. Martin Aske is probably correct when he argues that

the “systematic deviancy” of Keats’s poems “confirm[s] the radical ex-

tent to which they begin to question some of the assumptions of

Winckelmann’s Hellenism” (Keats and Hellenism [Cambridge Univer-

sity Press, 1985], p. 6). Ferris admits at one point that “none of these

poets can be easily fitted within the Hellenism so frequently associated

with Winckelmann” (p. 86). It would have been good, therefore, to

have had a serious discussion of just why Winckelmann did not take

off in Britain as he did, for example, in France. Why was History of An-

cient Art not translated? Who was reading him and who was not?

Probably because German writers dominate Ferris’s notions of Hel-

lenism, his book is very abstract. Repeatedly, he tries to abstract state-

ments or facts still further. Rather than citing the discoveries at

Pompeii and Herculaneum as decisive in the development of Helle-

nism, Ferris prefers “the reconfiguring of the aesthetic as a source of

historical knowledge” (p. 2). And he wants to move away from the

historical or geographical particularity of Greece: “The significance

of Hellenism does not lie in its occurrence as a historical phenome-

non but rather in its establishment of a concept of culture that went

by the name of Greece” (p. 17). British Romantic Hellenism, how-

ever, was caught in a tension between the abstract and the concrete,

between the timeless idea of Greece and its contemporary historical

specificity. Events like the arrival of the Elgin Marbles or the outbreak

of the Greek War of Independence demanded a reassessment of more

abstract ideas of antiquity and modernity and gave the new celebra-

tion of the aesthetic a topical, political urgency.

If Silent Urns provokes a new edition of Winckelmann in English, it

will have done a good service. At present, if students wish to read

him, they can turn only to David Irwin’s good but abridged selection

of Winckelmann’s writing (Winckelmann: Writings on Art [London:

Phaidon, 1972], out of print). A new translation of Winckelmann, with

One Line Long

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.115 on Wed, 15 Feb 2023 18:19:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Book Reviews 633

a historically sensitive survey of his impact and influence on European

Romanticism, would be most welcome.

Jennifer Wallace

Peterhouse, Cambridge University

Amnesiac Selves: Nostalgia, Forgetting, and British Fiction, 1810–1870.

Nicholas Dames. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Pp. x+298.

Near the end of Price and Prejudice (1813), Elizabeth Bennet gives Darcy

a playful lesson about how to look back on the rocky history of their

courtship. “You must learn something of my philosophy,” she coun-

sels; “Think only of the past as its remembrance gives you pleasure.” 1

In Amnesiac Selves: Nostalgia, Forgetting, and British Fiction, 1810–1870,

Nicholas Dames argues that something like this ethos lies at the heart

of the British nineteenth-century novel. From Jane Austen to the mid-

Victorians, Dames finds an overwhelming preference for controlled

recollection or even forgetting, a mode equally distant from the free-

wheeling mnemonic associations of Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy

(1760–67) and the cascading remembrances of James Joyce or Marcel

Proust. More than the novels that precede and follow it, Dames con-

tends, British fiction from 1810 through the 1860s emphasizes and

produces a mind-set focused on an edited and useful rather than an

unwieldy or traumatic past. Often reading novels in tandem with

schools of nineteenth-century psychological theory, Dames delineates

versions of this amnesiac orientation from Austen’s comedies to Wilkie

Collins’s sensation fiction, tracing it not only in characters such as

Elizabeth Bennet but more critically in the very shapes of nineteenth-

century narrative.

In a splendid opening chapter, “Austen’s Nostalgics,” Dames inves-

tigates the transformations of “nostalgia” from late eighteenth-century

medicine, in which it denoted a diseased homesickness powerful

enough to prove fatal, to Austen’s novels, which turn it into something

like modern nostalgia, a gentle, vague sense of the past, “at once a

form of memory . . . and a form of forgetting, for it dispenses with

the vividness that the past had previously held” (p. 23). Identifying

Marianne Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility (1811) as suffering from

the older, pathologized nostalgia, Dames analyzes her illness and the

1. Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice (1813; reprint, Oxford and New York: Oxford

University Press, 1990), p. 326.

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.115 on Wed, 15 Feb 2023 18:19:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Ours Once More: Folklore, Ideology, and the Making of Modern GreeceFrom EverandOurs Once More: Folklore, Ideology, and the Making of Modern GreeceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Hellenism Unbound Some Thoughts On The TDocument20 pagesHellenism Unbound Some Thoughts On The Tmariza petropoulouNo ratings yet

- Download Romanticism Hellenism And The Philosophy Of Nature 1St Ed Edition William S Davis all chapterDocument67 pagesDownload Romanticism Hellenism And The Philosophy Of Nature 1St Ed Edition William S Davis all chaptermeghan.irvine455100% (6)

- Nektaria Klapaki Modern Greek LiteratureDocument16 pagesNektaria Klapaki Modern Greek LiteratureEve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- Romanticism, Hellenism, Philosophy Nature: and The OFDocument164 pagesRomanticism, Hellenism, Philosophy Nature: and The OFPerched Above100% (2)

- Clare Foster and Helen Roche: University of Cambridge, UKDocument4 pagesClare Foster and Helen Roche: University of Cambridge, UKRodrigo MoraesNo ratings yet

- Fowler - Formation of Genres in The Renaissance and AfterDocument17 pagesFowler - Formation of Genres in The Renaissance and AfterHans Peter Wieser100% (1)

- A Journey Through Times and Cultures? Ancient Greek Forms in American Nineteenth-Century Architecture: An Archaeological ViewDocument32 pagesA Journey Through Times and Cultures? Ancient Greek Forms in American Nineteenth-Century Architecture: An Archaeological ViewindraNo ratings yet

- Ancient Greece's Influence on Western CivilizationDocument11 pagesAncient Greece's Influence on Western CivilizationIvan MarjanovicNo ratings yet

- Damrosch 2003 - What Is World LiteratureDocument7 pagesDamrosch 2003 - What Is World LiteratureblablismoNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of The Study of The Hellenistic Period - VadanDocument10 pagesThe Evolution of The Study of The Hellenistic Period - VadanGabriel Gómez FrancoNo ratings yet

- Elements of Euclid, Who Lived in Alexandria, Represented, in Its Thirteen Books and 500Document7 pagesElements of Euclid, Who Lived in Alexandria, Represented, in Its Thirteen Books and 500Димитър ФидановNo ratings yet

- Beyond The Acropolis: Rethinking NeohellenismDocument33 pagesBeyond The Acropolis: Rethinking Neohellenismathan tziorNo ratings yet

- Greeks on Greekness: Viewing the Greek Past under the Roman EmpireFrom EverandGreeks on Greekness: Viewing the Greek Past under the Roman EmpireDavid KonstanNo ratings yet

- The Golden and the Brazen World: Papers in Literature and History, 1650-1800From EverandThe Golden and the Brazen World: Papers in Literature and History, 1650-1800No ratings yet

- Cartledge - The Greeks and AnthropologyDocument13 pagesCartledge - The Greeks and AnthropologyGracoNo ratings yet

- The Glory That Was Greece: a survey of Hellenic culture and civilisationFrom EverandThe Glory That Was Greece: a survey of Hellenic culture and civilisationNo ratings yet

- WB Fuchs EssayDocument25 pagesWB Fuchs EssaygolightNo ratings yet

- Postcolonial Translation FinalDocument12 pagesPostcolonial Translation FinalprplpltpsNo ratings yet

- AHR Briant PDFDocument2 pagesAHR Briant PDFKostas VlassopoulosNo ratings yet

- Anna Tabaki : D'études Du Sud-Est Européen, Nos 28-29/1998-1999, Special Issue, in P A R T I C U L A R TheDocument16 pagesAnna Tabaki : D'études Du Sud-Est Européen, Nos 28-29/1998-1999, Special Issue, in P A R T I C U L A R ThenikolettaNo ratings yet

- Greece As The Uncanny For ModernityDocument22 pagesGreece As The Uncanny For ModernityparadoyleytraNo ratings yet

- Artemis LeontisDocument30 pagesArtemis LeontisGiwrgosKalogirouNo ratings yet

- Klimt Ancient GreeceDocument18 pagesKlimt Ancient GreeceAna CancelaNo ratings yet

- 2001 - Nickolas Pappas - Philhellenism and Greek PhilosophyDocument9 pages2001 - Nickolas Pappas - Philhellenism and Greek PhilosophyAlice SilvaNo ratings yet

- Black Athena The Afroasiatic Roots of CLDocument4 pagesBlack Athena The Afroasiatic Roots of CLCan CeylanNo ratings yet

- Studies in HeliodorusFrom EverandStudies in HeliodorusRichard HunterNo ratings yet

- Greek Art and Lit in Marx PDFDocument27 pagesGreek Art and Lit in Marx PDFJacob LundquistNo ratings yet

- J ctt46mz0k 7Document17 pagesJ ctt46mz0k 7Owen HoNo ratings yet

- Greek Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesGreek Literature Revieworlfgcvkg100% (1)

- Helen Nort. Sophrosyne - Self-Knowledge and Self-Restraint in Greek Literature PDFDocument421 pagesHelen Nort. Sophrosyne - Self-Knowledge and Self-Restraint in Greek Literature PDFYemdihan Uçak67% (3)

- A Roomful of Mirrors PDFDocument46 pagesA Roomful of Mirrors PDFproklosNo ratings yet

- Cultural Refinement/ Social Class: 19.08.2015 AntiquarianismDocument11 pagesCultural Refinement/ Social Class: 19.08.2015 AntiquarianismRoberto SalazarNo ratings yet

- Heyj45 12307Document111 pagesHeyj45 12307Sandra RamirezNo ratings yet

- Greek Literature History and Characteristics in DetailDocument6 pagesGreek Literature History and Characteristics in DetailMy SiteNo ratings yet

- Persistence of Folly: On the Origins of German Dramatic LiteratureFrom EverandPersistence of Folly: On the Origins of German Dramatic LiteratureNo ratings yet

- Roman Greece Renaissance CapturedDocument2 pagesRoman Greece Renaissance CapturedLucas LopezNo ratings yet

- Damian Valdez (Auth.) - German Philhellenism - The Pathos of The Historical Imagination From Winckelmann To Goethe-Palgrave Macmillan US (2014)Document262 pagesDamian Valdez (Auth.) - German Philhellenism - The Pathos of The Historical Imagination From Winckelmann To Goethe-Palgrave Macmillan US (2014)Eric E. Ríos Minor100% (1)

- Art Among The Ruins by Frank Kermode - The New York Review of BooksDocument15 pagesArt Among The Ruins by Frank Kermode - The New York Review of BooksrenonimoNo ratings yet

- Goddess Names May 2014Document114 pagesGoddess Names May 2014Romel ElihordeNo ratings yet

- IJCRT2008076Document5 pagesIJCRT2008076Farhad AliNo ratings yet

- 263-285. 9. For An End To Discursive CrisisDocument24 pages263-285. 9. For An End To Discursive CrisisBaha ZaferNo ratings yet

- 235 481 1 SM PDFDocument20 pages235 481 1 SM PDFOrhun KevenNo ratings yet

- Allen, W. - The Epyllion - TAPhA 71 (1940)Document27 pagesAllen, W. - The Epyllion - TAPhA 71 (1940)rojaminervaNo ratings yet

- Gum Brecht 1985Document14 pagesGum Brecht 1985Federico Asiss GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Harvard University's Department of Classics Explores the Latin Epyllion GenreDocument15 pagesHarvard University's Department of Classics Explores the Latin Epyllion GenrerojaminervaNo ratings yet

- Laonikos Chalkokondyles' HellenismDocument30 pagesLaonikos Chalkokondyles' HellenismAslihan AkisikNo ratings yet

- Laonikos Chalkokondyles' HellenismDocument30 pagesLaonikos Chalkokondyles' HellenismScott KennedyNo ratings yet

- For Frank Ankersmit, On The Occasion of His RetirementDocument10 pagesFor Frank Ankersmit, On The Occasion of His RetirementGustavo SandovalNo ratings yet

- Jeffrey M. Duban The Lesbian Lyre Reclaiming Sappho For The 21st Century 832pp. Clairview Books. 25. 978 1 905570 79 9Document1 pageJeffrey M. Duban The Lesbian Lyre Reclaiming Sappho For The 21st Century 832pp. Clairview Books. 25. 978 1 905570 79 9classicistNo ratings yet

- De Baecque. The Allegorical Image of France, 1750-1800Document34 pagesDe Baecque. The Allegorical Image of France, 1750-1800Luciano VernazzaNo ratings yet

- Rezension Jas ElsnerDocument5 pagesRezension Jas ElsnercatalinNo ratings yet

- Barbara Carnevali and Gianni Paganini EdDocument7 pagesBarbara Carnevali and Gianni Paganini EdcocoNo ratings yet

- Zzzzizoizoizoizoizoizoizoizoizoiz PDFDocument441 pagesZzzzizoizoizoizoizoizoizoizoizoiz PDFramón adrián ponce testino100% (1)

- MGSO Vol 1 (2015)Document22 pagesMGSO Vol 1 (2015)Sasha PozelliNo ratings yet

- Susan Stephens - Seeing DoubleDocument317 pagesSusan Stephens - Seeing DoubleMladen Toković100% (1)

- Greek Sculpture: A Collection of 16 Pictures of Greek Marbles (Illustrated)From EverandGreek Sculpture: A Collection of 16 Pictures of Greek Marbles (Illustrated)No ratings yet

- Colloquium AbstractsDocument9 pagesColloquium AbstractsΝότης ΤουφεξήςNo ratings yet

- The Examining of Hellenism and Effects oDocument7 pagesThe Examining of Hellenism and Effects omercedesNo ratings yet

- First and Last Romantics ExploredDocument9 pagesFirst and Last Romantics ExploredmercedesNo ratings yet

- Bloom. Coleridge - The Anxiety of InfluenceDocument7 pagesBloom. Coleridge - The Anxiety of InfluencemercedesNo ratings yet

- Liam O'Flaherty's short stories explore Irish identityDocument3 pagesLiam O'Flaherty's short stories explore Irish identitymercedesNo ratings yet

- Critical Background Frank O'ConnorDocument4 pagesCritical Background Frank O'ConnormercedesNo ratings yet

- Critical Background W.B. YEATSDocument7 pagesCritical Background W.B. YEATSmercedesNo ratings yet

- Critical Background Mary LavinDocument3 pagesCritical Background Mary LavinmercedesNo ratings yet

- George Moore's "Home SicknessDocument2 pagesGeorge Moore's "Home SicknessmercedesNo ratings yet

- Sample Pec/Exam: Literatura Norteamericana Ii.1: Desde 1900 Hasta 1945Document4 pagesSample Pec/Exam: Literatura Norteamericana Ii.1: Desde 1900 Hasta 1945mercedesNo ratings yet

- Cyprian Norwid and the History of Greece: An Analysis of the Poet's Engagement with Classical AntiquityDocument274 pagesCyprian Norwid and the History of Greece: An Analysis of the Poet's Engagement with Classical AntiquitymercedesNo ratings yet

- InfoDocument2 pagesInfomercedesNo ratings yet

- ReadingsDocument1 pageReadingsmercedesNo ratings yet

- Letitia Landon and Romantic HellenismDocument6 pagesLetitia Landon and Romantic HellenismmercedesNo ratings yet

- Mock Exam Trad2021 30 MayoDocument2 pagesMock Exam Trad2021 30 MayomercedesNo ratings yet

- ReadingsDocument1 pageReadingsmercedesNo ratings yet

- Frater+Acher The+Egyptian+SorcererDocument39 pagesFrater+Acher The+Egyptian+SorcererJoshua Coverstone100% (1)

- Module 1 - Language, Literature and Non-Literary TextsDocument12 pagesModule 1 - Language, Literature and Non-Literary TextsJessabel FerrerasNo ratings yet

- Lagos JSS English Schemes of WorkDocument23 pagesLagos JSS English Schemes of Workfaith100% (2)

- Sandhya Prarthana (Pampakuda)Document13 pagesSandhya Prarthana (Pampakuda)Jobin50% (20)

- Critical Essay of Bone Gap - Danielle HrinowichDocument2 pagesCritical Essay of Bone Gap - Danielle Hrinowichapi-548084784No ratings yet

- CLC 12 - Capstone Draft Proposal WorksheetDocument2 pagesCLC 12 - Capstone Draft Proposal Worksheetapi-634225400No ratings yet

- The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe - JournalsDocument6 pagesThe Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe - JournalsAmy FaustinosNo ratings yet

- Types of EssayDocument18 pagesTypes of EssayAnggun NtlyaNo ratings yet

- Poetry Essay StructureDocument7 pagesPoetry Essay StructuredstqduwhdNo ratings yet

- Decolonising The Indian MindDocument13 pagesDecolonising The Indian MindPremNo ratings yet

- Best summary, themes and quotes from booksDocument4 pagesBest summary, themes and quotes from booksAmritendu MaitiNo ratings yet

- R.K.Narayan ThemesDocument17 pagesR.K.Narayan ThemesabinayaNo ratings yet

- Ficto Criticism King1991Document18 pagesFicto Criticism King1991zlidjukaNo ratings yet

- RT AmHorror2010 Key TestDocument5 pagesRT AmHorror2010 Key TestЕгор ДьяченкоNo ratings yet

- Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Anthony Dunne & FionaDocument5 pagesSpeculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Anthony Dunne & FionaFi Lipe FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Siddha Kunjika Stotram in EnglishDocument6 pagesSiddha Kunjika Stotram in EnglishPartha Pratim Baruah100% (1)

- Vision and Blurriness: A Postcolonial Study of Uzma Aslam Khan's Novel The Geometry of GodDocument6 pagesVision and Blurriness: A Postcolonial Study of Uzma Aslam Khan's Novel The Geometry of GodQasim AliNo ratings yet

- Table of Specifications Tos TemplateDocument2 pagesTable of Specifications Tos TemplateAdria Vina GabaynoNo ratings yet

- Dokumen - Tips Biag Ni Lam Ag Reaction Paper Lit 1Document1 pageDokumen - Tips Biag Ni Lam Ag Reaction Paper Lit 1Leolyn Grospe Aquino100% (1)

- 4 APA 7th EDITIONDocument46 pages4 APA 7th EDITIONKerby Oner OlilaNo ratings yet

- John Steinbeck - The Harvest GypsiesDocument37 pagesJohn Steinbeck - The Harvest Gypsiespbsneedtoknow69% (32)

- Independent Novel Project GuideDocument16 pagesIndependent Novel Project GuideThe2WhoCouldNo ratings yet

- Representative TextDocument4 pagesRepresentative TextJohn Aldrin LimpiadaNo ratings yet

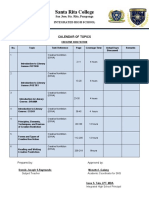

- Santa Rita College: San Jose, Sta. Rita, Pampanga Integrated High SchoolDocument2 pagesSanta Rita College: San Jose, Sta. Rita, Pampanga Integrated High SchoolricoliwanagNo ratings yet

- Not Waving But DrowningDocument10 pagesNot Waving But DrowningDavid AntwiNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of Matter and Spirit in The Poetry of Theodore RoethkeDocument125 pagesThe Evolution of Matter and Spirit in The Poetry of Theodore RoethkejakeNo ratings yet

- Chapter One:: Introduction and Theoretical BackgroundDocument24 pagesChapter One:: Introduction and Theoretical BackgroundCandido SantosNo ratings yet

- Superhero and Villain Tables V 02Document1 pageSuperhero and Villain Tables V 02Tyler LavilleNo ratings yet

- The Age of Johnson or SensibilityDocument1 pageThe Age of Johnson or SensibilitySandy Alice67% (6)

- Of Studies by Francis BaconDocument3 pagesOf Studies by Francis Baconclarence manegdegNo ratings yet