Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Wilson2002 - Student Participation and School Culture: A Secondary School Case Study

Uploaded by

Alice ChenOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Wilson2002 - Student Participation and School Culture: A Secondary School Case Study

Uploaded by

Alice ChenCopyright:

Available Formats

Student participation and school

culture: A secondary school

case study Steve Wilson

University of Western Sydney

his paper reports the findings of a single-site case study investigating the

T nature of student participation in a coeducational comprehensive govern-

ment high school situated in the western suburbs of Sydney. The purpose of

the study was to understand the relationship between student participation and cul-

tural dimensions in the school, particularly those dimensions which acted to

enhance or inhibit student participation. The study used qualitative methodologies

and the author was a single researcher with prolonged engagement in the research

site. Fieldwork was conducted over 25 months within an emergent research design.

The research identified 24 cultural dimensions in the school which impacted upon

student participation. The majority of these were found to have an inhibiting impact

on student participation; 8 were found to have an enhancing impact.

Rationale and conceptual framework

Research generally indicates that students are still poor participants in secondary

schooling. Despite this, student participation in schooling is critical to meeting

student needs because quality educational outcomes are best achieved by harness-

ing student motivation through participation (Boomer, Lester, Onore, & Cook,

1992; Broadfoot, 1991; Glasser, 1990; Nixon, 1996). Holdsworth (1996) suggests

that educators need to understand how student participation can be fostered in

schools.

In this study, distinction was made between forms of participation that are

tokenistic and those that are 'meaningful'. The concept of meaningful partici-

pation has its roots in the writings of Habermas (1972, 1990, 1993) and others

(Kemmis, Cole, & Suggett, 1983; Roberts, 1991; Young, 1990) who endorse

emancipatory processes of communicative action in which all stakeholders have a

voice. Meaningful forms of participation have meaning for the participant, and

contrast with disengaging forms of student participation often employed in schools

(Holdsworth, 1988). Forms of participation which have such meaning have been

labelled 'active' participation (Holdsworth, 1997), 'authentic' participation

(Cumming, 1994; Soliman, 1987), and 'deep' participation (Wilson, 2000). These

forms of participation are about students being active, taken seriously, listened to,

and doing work of consequence. The notion of student voice is fundamental to

Australian Journal ofEducation, Vol. 46, No. I, 2002, 79-102 79

deep participation. If students are to be accepted as partrcipants in and prac-

titioners of education (Holdsworth, 1996; Kelley, 1993; Kemmis et al., 1983), it is

clear that student 'voice' becomes a critical factor in allowing students to par-

ticipate (Farrell, Peguero, Lindsey, & White, 1988; Young, 1990). Students can

exercise participation in a variety of contexts within schools, most notably through

their learning experiences, through involvement in formal school govern-

ance processes, and through student governance and other student-operated

organisations within schools (Holdsworth, 1988).

Nature of the research site

Barracks High School (a pseudonym for the research site) is a state high school that

had 840 students at the time of the research. It is situated adjacent to a thriving

central business district in one of Sydney's most rapidly growing satellite cities.

The school is relatively old, having celebrated 120 years of continuous education

on the site. The school made much of its history, maintaining archival records and

an active ex-students association. The make-up of the student population was mul-

ticultural with only 10 per cent of students having Anglo-Saxon origins. The

remainder represented some 60 different ethnic and religious groups.

At the beginning of the study, Barracks High had a newly appointed princi-

pal. He felt that the school had a strong ethos of pastoral care, a justified emphasis

on multiculturalism, a traditional 1960s curriculum which needed modernising,

almost non-existent management structures which required re-structuring, and an

out-of-date perspective on student participation. The study began during a period

of quite significant change as the school sought to tackle these issues under the new

principal's leadership. The school context was relatively turbulent during this

period. This research was conducted at the invitation of the new principal, and

after agreement by staff

Research methods

The research was conducted over a 25-month period with a total of78 days spent

in the school. Data collection methods included many in-depth interviews, par-

ticipant observations documented through the writing of field notes and field

journals, and the collection of many documents and school artefacts (Merriam,

1988). These methods helped to uncover the multiple realities which existed in the

site among the various stakeholder groups (students, teachers, executive teachers,

senior executive teachers and non-teaching members of staff), and allowed the

nature of school cultural practices and their impact on student participation to be

identified. A particularly interesting method used in the study involved sets of

interviews conducted separately with students and teachers as 'hermeneutic circles'

(Guba & Lincoln, 1989). Consolidated summaries from these interviews, using the

power of participant voices as text, were disseminated throughout the school dur-

ing the research and resulted in much interest and comment on student and teacher

ideas. This provided further valuable data. Data analysis involved the development

of grounded theory based upon systematic coding of data through constant

80 Australian Journal ofEducation

comparison (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). This identified a number of key themes or

stories in the school, some of which related to school image, reputation and

traditions, teacher and student views oflearning, school decision making and lead-

ership, the nature of student organisations in the school, and notions of school

change and development. These issues were constant, of concern to staff and

students, and provided rich data over the life of the study.

Cultural context: Broad themes

Research findings identified five broad sets of data categories, each indicating

a key cultural theme within Barracks High School which impacted on student

participation.

Development of school ethos

The principal and teachers felt the need to develop the school's ethos because

Barracks was situated near a number of older state and private schools. Barracks felt

the need to compete with these schools by building a comparable school image

and ethos. The symbols chosen to underpin this ethos were the school's multicul-

tural nature, its school uniform, strong discipline, and its history. Students and

teachers generally supported these directions, though some conflict resulted as

teachers and students felt that efforts to enforce the wearing of school uniform

were overdone.

School governance and decision making

School governance and decision making comprised an important theme in relation

to student participation. A range of school management groups were accessible to

teachers (though not to students); however these groups were not empowered to

make decisions. Teachers began to see management groups as forums for discus-

sion rather than action, and believed that power lay outside of them. Teachers felt

disempowered. They perceived that, although the decision-making style of the

principal was outwardly democratic, in reality it was consistently directive.

These feelings were also held by some executive teachers, and caused cynicism,

withdrawal, low morale and lack of motivation.

Student Representative Council

The Student Representative Council (SRC) at Barracks contained many talented

students but was ultimately a frustrating experience for its members. The SRC was

not integrated into school decision-making processes and was not valued enough

by the principal, teachers or other students. It did not have the level of support it

needed to help it identify and work towards its goals. Despite a rhetoric of partici-

pation in Barracks High, in reality SRC members were expected to work within

the confines of school expectations, upholding the traditional and confining

orientations of school ethos. Even low-level student initiatives put forward by the

SRC, including requests for school dances, non-uniform days and changes to the

school uniform, were ultimately deemed unacceptable because they were

perceived to threaten the desired image of the school.

Student participation and school culture 81

Place of student voice

Student constructions of schooling comprised views and theories touching on

many areas of school life, including teaching methods, relationships with teachers,

bullying and teasing, safety in school, and the wearing of school uniform. Students

often developed theories about school that were insightful and efficacious (see

Wilson, 1998), and many students had quality ideas that would allow them to par-

ticipate meaningfully in school development and decision making. However,

despite the power of their ideas, most student voices went unrecognised and had

no access to forums for discussion or decision making.

Approaches to teaching and learning

Classroom-related learning activities provide the greatest opportunity for the great-

est number of students to engage in participation in school, yet teaching at

Barracks High was generally found to be 'traditional', textbook centred and

didactic. Barracks was more concerned with curriculum development processes,

especially the implementation of a 'semesterised' curriculum, than with teaching

and learning practices in classrooms. Few executive teachers, even those at the

faculty head level, saw it as their role to lead changes in classroom practice, despite

teaching and learning being identified as focus areas in school planning documents.

Despite student voices during the research clearly pointing to the nature of

'good' and questionable teaching practices at Barracks, teachers were reluctant to

change and there was a lack of urgency among school leaders to accept teaching

and learning as the core business of the school.

Cultural dimensions influencing student participation

Data analysis resulted in the identification of the broad cultural themes outlined

above, the sub-components of which were coded and given substance through

processes of grounded theory data analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). From this

process of coding were identified sets of cultural phenomena (ultimately labelled

'dimensions') which were found to be significant influences on student partici-

pation. These dimensions were able to be grouped into four distinct clusters of

cultural dimensions at Barracks pertinent to student participation. One cluster

comprised three dimensions which were found to be fundamental and pervasive

cultural dimensions in the school. These were labelled 'primary' dimensions. A

second cluster was labelled 'socio-political' dimensions. These relate to external

social and political pressures on the school and to internal dimensions concerned

with decision-making structures and ways in which individuals were positioned in

terms of power and autonomy. A third cluster of dimensions was labelled 'cur-

ricular' dimensions. These describe conditions and processes which influence

curriculum development and classroom teaching. A final group was labelled

'personal-participant' dimensions, and describes dimensions relating to the beliefs

and attitudes of participants at Barracks-most prominently, students, teachers and

executive teachers.

82 Australian Journal ofEducation

Each of these clusters of dimensions influenced student participation in a way

that was neither simple, nor linear. The relationships between cultural influences

on student participation at Barracks are best regarded as an ecological phenom-

enon. This ecology was complex and was beyond the resources of the study to

engage fully. Its components are therefore presented in this paper as a matrix which

outlines dimensions as distinct rather than inter-related entities.

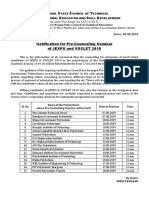

Figure 1 presents the matrix containing each of the cultural dimensions

identified at Barracks High and the relationship each had to student participation.

These dimensions were found to either enhance or inhibit student participation, and

were named according to the properties they were found to exhibit during formal

data analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). There were 24 cultural dimensions identi-

fied at Barracks that related to student participation. For every dimension that

enhanced participation, there were two that acted as inhibitors. It is not possible

in this paper to give a detailed treatment of each of these dimensions and the way

they influenced student participation in the school. However a brief overview of

each is provided below.

Dimensions which Dimensions which

ENHANCED INHIBITED

student participation student participation

Primary dimensions • paradigm boundedness

• fragmentation

• rhetorical ambiguity

SOcio-political dimensions • seeking out empathetic power • being under the microscope

• scaffolding • non-pedagogical orientations to

leadership

• sink or swim

• going cap in hand

• deflecting agendas

• learned helplessness

Curricular dimensions • student theorising • primacy of institutional values

• curriculum as the province of

the professional

• spoonfeeding

Personal-participant • celebratory perspectives of • dismissing student participation

dimensions youth • distrust of participant maturity

• desire for equity • tuning out

• desire for meaning • withdrawal

• wanting partnerships

• wanting in

Figure I Cultural dimensions at Barracks High and their relationship to

student participation

Student participation and school culture 83

Primary dimensions

Each of the three primary dimensions identified in the study acted to inhibit rather

than enhance student participation within Barracks. 'Paradigm boundedness'

relates to literature which suggests that secondary schools generally conform to a

model of schooling which emphasises the study of academic subjects, meritocratic

structures and processes, and didactic teaching methods (Connell, 1994; Edwards,

1995; Hargreaves & Earl, 1994), and in which student constructions are generally

unacknowledged or undervalued (Kemmis et al., 1983). At Barracks High, there

was a general acceptance of this paradigm, evident in both teacher and student

comments and teacher practices, and in the school's emphasis on its history and

looking backward to its past to define its present. Despite rhetoric in the school

about student futures and student centred activities, an unproblematic accep-

tance of the traditional paradigm positioned students in traditional roles where

they had little opportunity to define the school and were expected simply to

'fit in'. Paradigm boundedness was an inhibiting cultural dimension for student

participation.

The term 'fragmentation' is common in the literature and identifies phenom-

ena in secondary schools including fragmentation of the curriculum (Hargreaves,

1994; Hargreaves & Earl, 1994; Stodolsky, 1993) and fragmentation caused by

departmental structures leading to teacher separation and isolation (Eisner, 1988;

Stodolsky, 1993). Fragmentation existed at Barracks as a lack of organisational

cohesion and communication leading to fragmented understandings and courses of

action among school stakeholders. It existed in school governance, leadership, and

in school approaches to teaching and learning where few teachers were aware of

the teaching and learning practices of their colleagues. Fragmentation inhibited

student participation because school policies relating to participation were able to

be ignored due to fragmented leadership and accountability processes.

'Rhetorical ambiguity' relates to literature which identifies a tension between

the ideas espoused by practitioners (their espoused theories), and their actions,

which are often at odds with their espoused theories (Argyris, 1993; Argyris &

Schon, 1996). A feature of the Barracks High culture was the extent to which

words, both spoken and written, were attributed a subtext where outwardly

intended meanings were not necessarily those accepted by participants. This

dimension has been labelled 'rhetorical ambiguity', and is defined as the prepared-

ness of participants to say, or expect and accept others saying, sentiments that were

not intended to be believed or acted upon in practice. At Barracks it was a

primary dimension, stemming from the principal's espoused belief that 'image is

reality', but evidenced in a variety of ways in school life. This dimension was

rhetorical in the sense that much written documentation and statements emanat-

ing from Barracks were regarded as being for 'show', for an external audience that

had to be convinced that the school and its participants were functioning at an

expected level. Teachers indicated that many of the sentiments in school policies

were there to satisfy accountability requirements and convince external authorities

that acceptable change was occurring. Barracks's Student participation policy was

an example of a document seemingly developed for show. If the cutting-edge

84 Australian Journal ofEducation

sentiments expressed in this policy had been taken at all seriously, student partici-

pation would have been very different at Barracks High. Rhetorical ambiguity was

a powerful, inhibiting dimension for student participation, resulting in a lack of

action by teachers and students (especially on the SRC) on initiatives which would

have increased student participation. Not knowing what was to be believed or

taken seriously, teachers and students were often not committed in their efforts in

what they saw as token projects.

Socio-political dimensions

Socio-political dimensions relate to external social and political pressures, and to

internal political or power relations in the school, that were found to be important

influences on student participation. Six of the eight socio-political dimensions

acted to inhibit student participation.

Inhibiting dimensions

Being under the microscope This describes perceptions by teachers that they were

under observation from outside the school; that they were subject to external

expectations that impacted on their work yet they could not control. The litera-

ture indicates it is common for teachers to feel under these kinds of pressures from

parents (Dellar, 1992; GECD, 1989), bureaucracies (Dinham, 1995; Larson, 1992;

Raebeck, 1992) and media (Raethel, 1997a, 1997b), resulting in confusion and

ambiguity concerning the role schools and teachers are expected to play. At

Barracks, feelings of being under the microscope were identified by participants as

pressure from media interest in events involving gangs and fights, and in the need

to prepare students effectively for examinations so that public expectations of

acceptable Higher School Certificate (HSC) exam results could be met. Teachers

seemed to be continuously aware of the need to be accountable to these external

forces. Being under the microscope caused teachers to develop an 'accountability

mentality' where they continually weighed up the consequences of their actions in

terms of possible public perceptions. A significant example was a teacher who,

when a media report linked a lack of student note making with poor HSC results,

stopped using student discussion as a teaching methodology and began having

students write more notes. Being under the microscope related negatively to stu-

dent participation because it made teachers conservative in the decisions they took,

and unlikely to take risks and experiment in their teaching approaches with students.

Non-pedagogical orientations to leadership Some literature points to school principals

becoming alienated from their staff by placing administrative concerns before

pedagogical considerations (Ball & Bowe, 1992; Seay & Blase, 1992), leading to

staff disenchantment with change and decreasing teacher motivation (Fraatz, 1987;

Hargreaves, 1992). This study identified a widespread non-pedagogical orientation

to leadership among the majority of the school executive, although it was not

directly related to the principal. Few school leaders at Barracks took the oppor-

tunity to lead other teachers in pedagogical practice. Leadership perspectives were

focused on other areas. The principal saw his main responsibility as working to

'sell' the school, develop its physical environment, emphasise its history, and

Student participation and school culture 85

encourage major public events such as historical celebrations. A succession of

deputy principals focused primarily on the development of a 'semesterised' cur-

riculum structure rather than pedagogy, and these curriculum initiatives did not

translate into pedagogical reforms. Faculty heads saw their role as managerial:

maintaining faculty programs, managing resources and making sure school and

systemic policies were adhered to by staff. The development of teaching and learn-

ing was seen as something that would be nice to engage in if there were time, but

faculty meetings were usually spent on managerial issues and disseminating infor-

mation from executive meetings. Few people consequently took responsibility for

developing more active approaches to teaching which may have led to improved

student classroom participation.

Sink orswim Sink or swim describes the tendency ofsome participants at Barracks

to expect students to demonstrate competence without being taught the necessary

skills. This was apparent at a number of levels, and in each case constituted an

inhibiting dimension for student participation. The most obvious level was in the

SRC, where it was common for teachers to expect students to succeed on their

own (swim), without help or training from staff. If students were not capable of

autonomous success, they were allowed to fail (sink), and as a result were often

considered disinterested in the SRC or not capable of success. Perceived failures of

the SRC to succeed in their projects (planning camps, raising money for charities,

running meetings effectively) tended to reinforce a view among some teachers that

students were not interested in, or capable of, accepting responsibility.

Going cap in hand School leaders often adopt hierarchical decision-making struc-

tures in which they are vested with significant power (Cohen & Harrison, 1982),

often sponsor those initiatives with which they are personally comfortable (Fullan,

1991), and act as significant 'blockers' of initiatives with which they do not agree

(Cohen & Harrison, 1982; Smylie & Brownlee-Conyers, 1992). At Barracks,

going cap in hand related to the principal's leadership style. Teachers and SRC

members had to seek out the principal's personal approval for many courses of

action, despite the rhetoric of participation which the principal employed. This led

to feelings of disempowerment and disinterest among teachers and SRC members

and a lack of agency, commitment and innovative behaviour. Going cap in hand

was an inhibiting dimension for both student and teacher participation at Barracks

which related strongly to another socio-political. dimension of the Barracks

context, 'learned helplessness'.

Dfjlecting agendas This was a dimension related to going cap in hand, and to

literature which shows principals are able to be effective 'blocking' agents in schools

(Cohen & Harrison, 1982; Smylie & Brownlee-Conyers, 1992). Both the principal

and the teacher adviser of the SRC engaged in deflecting agendas, to the detriment

of student participation. SRC proposals to have school dances, camps, changes to

the girls' uniform and non-uniform days were each rejected or stalled on grounds

of safety or because they did not fit with the desired image for the school. Students

became frustrated with these tactics because they were usually encouraged to put

submissions to school leaders, often with a lot of work and energy behind them,

86 Australian Journal ofEducation

only to have them rejected at the end of the process. Students often minimised or

terminated their participation in the SRC as a result.

Learned helplessness Learned helplessness was a socio-political dimension that

relates to literature on micropolitics in schools which indicates that teachers can

become fatalistic about change and lack initiative as a result (Fullan, 1991; Roberts

& Blase, 1993; Seay & Blase, 1992). Participants at Barracks expressed their help-

lessness by displaying a lack of initiative, interest, motivation and action. Although

most were keen and willing in relation to those aspects of their work they felt they

could control, they also developed a view that it was pointless trying to influence

events in the wider arena. This helplessness was not a trait that necessarily resided

within individuals: it was a result of a school culture in which individuals learned

that it was difficult to influence events. At Barracks learned helplessness con-

tributed to a form of stasis where no one in authority felt they had enough power

to influence events and so little of substance occurred. This closely reflects research

by Cohen and Harrison (1982), which found that competing but fragmented

power relationships among teachers could lead to a vacuum in decision making in

secondary schools. Consequently, in this study, those teachers and school leaders

who were theoretically disposed to improving student participation in the class-

room did not act to do so. Learned helplessness was also a potent force within the

SRC at Barracks and inhibited student participation through the SRC. Lacking

encouragement, students found it difficult to complete projects, which resulted in

a lack of confidence among the SRC and having to wait to be told what they were

allowed to do.

Enhancing dimensions

Two socio-political dimensions were identified as enhancing of student partici-

pation: seeking out empathetic power and scaffolding. The former was initiated by

students, the latter by teachers.

Seeking out empathetic power Seeking out empathetic power describes the political

activity, adopted by some students at Barracks, of circumventing political impedi-

ments by identifying staff members they felt were sympathetic to their cause and

had the power to help them achieve their goals. Examples of students seeking out

empathetic power were unusual because it required a level of confidence that most

students did not seem to have, but they included SRC members by-passing the

SRC coordinator for advice, and students enlisting the help of a deputy principal

who would support their projects. Seeking out empathetic power provided an

important enhancing dimension for student participation at Barracks. It initiated

students into political processes of persuasion that were usually denied them and

was an important act of participation in itself It also allowed students to apply pres-

sure to teachers and caused teachers to reflect on the issue of student participation

and their personal responses to it. The few discussions about student partici-

pation were usually held between, or initiated by, adults. Seeking out empathetic

power provided students with an opportunity to begin the dialogue from their

perspective.

Student panicipation and school culture 87

Scaffolding At Barracks, when meaningful student participation did occur, it did

so that with the support of a teacher who provided structured and targeted sup-

port to students so that they could participate. The act of providing structured

forms of support is defined as 'scaffolding', drawing from constructs developed by

Vygotsky (1978) and Bruner (1986) in relation to cognitive growth. Scaffolding

was an important dimension of the Barracks context that acted to enhance student

participation. Scaffolding was critical to student participation at Barracks because

other cultural dimensions such as paradigm boundedness and learned helplessness

had helped to create passive students unused to taking initiative or achieving suc-

cess. Without scaffolding, student projects were often marked by poor planning,

poor team work, a lack of goal clarification and poor success rates. Scaffolding

helped students to develop the skills to overcome these obstacles.

Curricular dimensions

A number of curricular dimensions at Barracks influenced student participation. Of

these, the primacy of institutional values, curriculum as the province of the pro-

fessional, and spoonfeeding were found to be inhibiting dimensions for partici-

pation. A fourth dimension, student theorising, was found to be an enhancing

dimension.

Primacy of institutional values Primacy of institutional values was an important cur-

ricular dimension at Barracks where the emphasis on discipline, school uniform

and school history communicated that the values of the school stood above those

of the students and teachers, and were not negotiable. The school's values were

essentially meritocratic, emphasising success in relative and competitive terms and

drawing attention to high achievers. These values required students and teachers

to conform, to sacrifice individuality for the reputation of the school and the

benefit that school participants would derive from this reputation. These values

were not shared by significant numbers of participants, particularly students, who

saw the world with themselves more at the centre and whose values focused on

personal relevance, experience and growth. The primacy of institutional values also

inhibited classroom participation. Teachers who did share institutional values

found in this dimension a reason not to change their views of curriculum and

teaching, whereas teachers who did not share these values found conflict in the

way they perceived their roles as teachers. These teachers referred to their hesi-

tancy in using active learning approaches and group work. They were worried

about poor exam results and the responses of their more conservative peers to nois-

ier classrooms. For many teachers, the primacy of institutional values had the effect

oflimiting opportunities for students to participate in the classroom because many

teachers did not consider adopting teaching approaches which may have enhanced

participation.

Curriculum as the province if the professional Research indicates that teachers gener-

ally feel comfortable when they use transmission models of teaching in which

teachers possess privileged knowledge (Lewis, 1995; McNeil, 1988b; Young,

1990), and situations where they are in control of their work practices and matters

88 Australian Journal ofEducation

of curriculum (Blase, 1990; Fullan & Hargreaves, 1991; Lewis, 1995; Nias, 1987).

A dimension was identified at Barracks that is related to this literature, and has

been labelled 'curriculum as the province of the professional'. Curriculum as the

province of the professional describes the assumption held by numbers of par-

ticipants that those in the school best placed to understand curriculum and make

decisions about its development were teachers. Curriculum as the province of the

professional also resulted in limited opportunities in classrooms for students to help

determine the nature of content or learning experiences: there was little evidence

of student choice or negotiation in classrooms at Barracks High, although one

positive example of student negotiation arising from this study has previously been

documented (see Rabone & Wilson, 1997; Wilson, 2000).

SpoonJeeding 'Spoonfeeding' was a term used by teachers to describe the teacher

practice of giving unmotivated or under-performing students structured, unchal-

lenging classwork, characterised by students having simply to copy or learn 'right'

answers. Spoonfeeding was a reflection at Barracks of trends among teachers, also

identified in the literature, to expect less of students from culturally diverse and

economically deprived backgrounds (Beiser, Lancee, Gotowiec, Sack, & Redshirt,

1993; Cooper & Good, 1983; Meade, 1983; Tollefson, Melvin, & Thippavajjala,

1990). Many teachers felt that spoonfeeding was rife at Barracks, and attributed it

to student disinterest in academic work, poor literacy levels among students, and

student resistance to more active and rigorous learning approaches. Teachers

reasoned that, without spoonfeeding, students with low literacy levels would do

poorly in examinations, especially the School Certificate and HSC. Spoonfeeding

acted as an inhibiting dimension for student participation by providing students

with unstimulating, repetitive low-level work which deprived students of the

opportunity to engage in critical and creative thought, discussion and expression.

It positioned them ~s passive consumers of information rather than as active inter-

preters and critics, and dispossessed them of the opportunity to participate in

rigorous intellectual endeavour.

Student theorising This dimension enhanced student participation. Some literature

indicates that students in schools are capable of theorising about school practices

and contributing to school processes of curriculum change (Cumming, 1996;

Cummins, 1997; Furtwengler, 1985a; Roberts, 1991 ; Young, 1990). At Barracks,

student theories about curriculum, elicited and published through the hermen-

eutic circles, indicated that students could develop sophisticated insights into the

nature and consequences of curriculum and teaching practices (see Wilson, 1998).

Students effectively critiqued teaching practices, approaches to learning, classroom

management and assessment, and the nature of classroom environments.

Additionally they often offered their visions of better practice. Student theorising

was an enhancing dimension for student participation at Barracks, particularly

when, through teachers who were able to provide scaffolding, students were able

to present their theories. Occasionally during the study, students presented their

ideas in formal contexts, which gave them the opportunity to formalise their

ideas and express them carefully and logically. These acts in themselves were

Student participation and school culture 89

participatory, indeed emancipatory for some of those students involved, and of

significant benefit (Wilson, 1998).

Personal-participant dimensions

Personal-participant dimensions derived from the attitudes and beliefs of school

participants. Most of the enhancing dimensions for student participation were of

this type. Key inhibiting personal-participant dimensions identified were: dismiss-

ing student participation, a distrust of participant maturity, tuning out, and with-

drawal. Enhancing dimensions were: celebratory perspectives of youth, a desire for

equity, desire for meaning, wanting partnerships and wanting in.

Dismissing student participation Case reports of teacher innovation show that

effective teachers adopt strategies which enhance classroom participation by

students (for example, Daugherty, 1995; Levin, 1994; Renzulli, 1997). However

Cumming (1996) found that some teachers find it difficult to accept that students

should participate or should be given increased decision-making power. At

Barracks it was evident there was a general lack of belief among teachers that

student participation ought to be valued as a core school purpose. This was labelled

as 'dismissing student participation'. Teachers commonly perceived schooling in

traditional terms as the learning of academic content. For them, students had little

to bring to the definition or development of schooling. Teachers were the experts,

students were there to learn. Student participation was a nice idea, one which fit-

ted into the realm of rhetoric but could reasonably be forgotten in the real world

of examinations and community pressure for acceptable academic results. Even

teachers who espoused ideas compatible with student participation often failed to

pursue their implementation in the hurly-burly of daily practice. There was a

general lack of practical interest and action concerning student participation.

Distrust ifparticipant maturity The literature on student participation suggests that

students are often not considered by teachers or principals to have the capacity to

engage in meaningful forms of decision making (National Association of

Secondary School Principals, 1989; Nayano-Taylor, 1987; Spence 1993). At

Barracks, this came through strongly as a distrust of participant maturity. This dis-

trust was experienced by teachers and students alike at Barracks High, and helped

to create an atmosphere in the school which inhibited student participation.

Rather than challenging students to improve their work ethic and standards

of classroom behaviour, some teachers tended to respond to student disinterest and

management problems by narrowing down the range of classroom activities, focus-

ing on book work, and limiting interactive learning experiences. At the institu-

tional level, the school's discipline and school uniform policies and the manner

used to enforce them assumed that students could not be trusted, that coercion was

required to make students conform. Members of the SRC came to believe

they were not trusted to make decisions, and at different times felt they were not

trusted either by the principal or the SRC teacher adviser, as many of their

projects were denied or not supported.

90 Australian Journal of Education

Students, teachers, and to a lesser extent head teachers all felt this mistrust.

The outcome of this dimension for student participation was student and teacher

resentment and frustration at the way mistrust led to infrequent opportunities to

participate meaningfully in decision making and classroom activities. Feelings of

mistrust deprived many participants of opportunities to participate and accept

responsibility, helped to entrench the dimension ofleamed helplessness, and inhib-

ited student participation both in its direct effect upon students and through the

general non-participatory climate it helped to create in the school.

Tuning out Many students in secondary schools do not value the academic

agenda of schools, valuing sports (Freeston, 1993; Suitor & Reavis, 1995), other

extra-curricular activities (Nieto, 1994) and social interactions with friends over

other aspects of school life (Caimey et al., 1992; Walton & Hill, 1987).

Observations of student behaviour in classrooms indicate widespread student dis-

interest and boredom with academic work (Fullan, 1991; Nieto, 1994; Sarason,

1995; Siddle Walker, 1992). The literature also identifies similar characteristics

amongst teachers who become dissatisfied with their work and retreat into mini-

malist roles in their schools (Blase, 1990; Dinham, 1995; McNeil, 1988a; National

Board, 1993). Similar feelings about school were identified among students and

teachers at Barracks High. These were collectively labelled as the dimension of

'tuning out'. At Barracks, tuning out described the phenomenon of teachers and

students not wanting to be involved in school decision making, development or

change, or limiting their involvement to areas where they had influence. For

students, this often meant limiting their real commitment at school to subjects

where they perceived their agendas were being met, to sport, or just to maintain-

ing their social networks. Students also tuned out from their work on the SRC,

losing motivation and productivity as their agendas were deflected by those with

power. For teachers, tuning out meant ignoring school change initiatives and

focusing on their classroom teaching or a faculty responsibility. Signs of teachers

tuning out included teacher positions on school working groups remaining

unfilled, and teachers expressing that they now stayed out of school decision

making and politics. Tuning out was a significant inhibiting dimension for student

participation beyond the obvious consequence of causing students to cease their

participation in classrooms and student initiatives in the SRC. Tuning out helped

to reinforce an emerging culture of non-participation at Barracks.

Withdrawal As students and teachers in schools tune out from school life, so the

literature finds they also withdraw completely from it. Dinham's (1993) study

demonstrated that teachers can become so dissatisfied with aspects of their work

that they resign from the teaching service as a result. Literature on students in

schools deals with student alienation and finds that significant numbers of students

in secondary school are 'alienated' (Ainley & Sheret, 1992; Australian Curriculum

Studies Association, 1995), leading to non-performance or non-attendance at

school (Farrell et al., 1988; Gibson-Cline, 1996). At Barracks, a dimension was

identified among students and teachers that is related to concepts of alienation (for

example, Cormack, 1995) which has been labelled 'withdrawal'. Withdrawal was

Student participation and school culture 91

an inhibiting dimension for student participation, and describes a choice made by

some participants to cease their involvement in some or all aspects of school life.

Tuning out was a more common form of participant response to the school con-

text, but withdrawal represented a more serious response by participants who

chose this option. Students who withdrew did so by simply not attending school,

by leaving early, or by ceasing to participate in particular aspects of school life.

Often the reason for withdrawal was the failure of the school to provide them with

participatory opportunities. An example was a Year 10 male who left school to

work with the railways. He cited the reason as four years of junior education in

which teachers failed to understand his problems, capacities, or to provide an

appropriate standard of work. Like tuning out, withdrawal was an inhibiting

dimension because it added to the general malaise of non-participation at Barracks.

Celebratory perspectives oj youth A number of personal-participant dimensions were

found to enhance student participation. The most significant was celebratory

perspectives of youth. The literature identifies certain qualities that in the minds

of students determine good teachers, and usually these qualities revolve around

teachers having positive perspectives of young people (Abbott-Chapman, Hughes,

Holloway, & Wyld 1990; Disadvantaged Schools Program (DSP), 1992; Hughes,

1994). There were teachers at Barracks who placed students squarely at the centre

of their teaching. These teachers tended to listen to students, treat them equitably

and fairly, and reflect on and modify their teaching to meet student interests and

needs. These teachers were reflective, empathetic, and appeared intuitively to use

constructivist approaches to learning. Whereas other teachers may have liked

students (especially well-behaved and academically capable students), these

teachers valued young people, academic and non-academic alike. Students in turn

knew who these teachers were, enjoyed being in their classes (even if they did not

like the subject), participated and were motivated. Students could articulate why

these teachers were good teachers. The efforts of teachers who held celebratory

perspectives of youth led to improved student motivation, enthusiasm and partici-

pation. These teachers routinely provided scaffolding to students to help them

succeed in their projects inside and outside the classroom-a key example was the

leading teacher, a senior executive member who believed in the students enough

to convince the principal to let a group of students present to a full staff meeting

on teaching methods in the school. Where meaningful student participation

existed at Barracks (in the form of students discussing their own issues, being

listened to, and encouraged to make their own decisions) facilitating the process

was generally a teacher who held a celebratory perspective of young people.

Desire Jor equity The literature indicates that secondary school students would

often like to change school practices to make them more equitable. These feelings

of unfairness about the status quo and desire for change have been identified

among students in relation to reforming the relevance of academic subjects

(Cairney et al., 1992; Cumming, 1996; Nieto, 1994; Walton & Hill, 1987), teach-

ing practices (Shann, 1990), and teacher behaviours (Harris & Rudduck, 1993).

These feelings were also evident among students at Barracks High, and represent a

92 Australian Journal ofEducation

personal-participant dimension labelled as a 'desire for equity'. Desire for equity

was a key dimension for participation among students at Barracks, manifest in their

expressed need to be understood by teachers, to be treated fairly as emerging adults

and to have their points of view listened to. Desire for equity was significant

because it helped to mediate the quality of student participation and the ways

students chose to participate. It essentially acted as an enhancing dimension for

student participation. However, when other cultural dimensions such as going cap

in hand and deflecting agendas acted to block change, the desire for equity could

quickly lead to non-participation among students. At Barracks the desire for

equity appeared to be linked strongly to other personal-participant dimensions of

wanting in, tuning out and withdrawal.

Desire for meaning Secondary school students want to take subjects that are rele-

vant and meaningful for them (Farrell et al., 1988; Gibson-Cline, 1996), want to

improve their understanding of these subjects (Kempa & Orion, 1996; McNeil,

1988b), and want to participate in them through active and applied learning expe-

riences (Shepardson, 1993). Such a dimension was evident in the Barracks context

as students expressed the view that their learning needed to be meaningful if it was

to be valuable and stimulating. This dimension has been labelled as a 'desire for

meaning', and it constituted an enhancing dimension for student participation at

Barracks High.

Students desired meaning in relation to their classwork. They saw little point in

the content or learning methodologies associated with much of their classwork. It

was common for students to differentiate between theoretical and practical subjects

and to express a preference for practical subjects. Practical subjects had meaning,

either because they emphasised contemporary, useful or interesting content, were

associated with vocations or vocational skills, or because they provided active,

applied forms of learning. Practical subjects were more likely, in the minds of

students, to meet their needs. Theoretical subjects were associated with content

that was obscure, poorly explained or not readily applied to students' lives, and

teaching methods which depended almost exclusively on the reading of textbooks

and the making or copying of notes. Where students' desire for meaning was

realised, they were generally more motivated and performed better in their class-

work. However, like their desire for equity, when students' desire for meaning

remained unfulfilled students often reacted by withdrawal or tuning out.

Confronted with an unfulfilled desire for meaning in their schoolwork, many of

these students maintained minimal levels of participation in their academic work,

as testimony from teachers verified.

Wanting partnerships The literature on the secondary school context indicates that

teachers and students share many mainstream values associated with schooling,

with both wanting cohesive classroom climates (Raviv et al., 1990) where friend-

ly supportive relations exist between students and their teachers (Abbott-Chapman

et aI., 1990; Cohn & Kottkamp, 1993; Dinham, 1993, 1995; DSP, 1992; Hughes,

1994). In this study, this need was expressed powerfully by some participants and

transcended a simple sharing of values. At Barracks both students and teachers

Student participation and school culture 93

expressed a strong desire to be understood by the other group, and wished they

had the opportunity, based on improved understandings, to work with each other

for better schooling. This dimension has been labelled 'wanting partnerships' and

was an enhancing dimension for student participation.

Some teachers felt that students did not understand that they were real

people as well as teachers, whereas students wished that teachers could appreciate

things more from their perspective, understanding that they were more than

students, they were people with other lives, family pressures and part-time jobs.

Wanting partnerships was an enhancing dimension for student participation

because of its potential to provide transactions between students and teachers and

a basis for dialogue and negotiation. Wanting partnerships was something about

which students and teachers were concerned and shared views. The issues

were common ground, waiting for an opportunity to become dialogue between

students and teachers, to be negotiated into a more commonly accepted and

improved standard of relationships between them. Unfortunately at Barracks,

impeding cultural dimensions ensured that these opportunities were not realised.

None the less the feeling of wanting partnerships represented a potential lead-in

to better student teacher communication and subsequent student participation in

redefining student-teacher relationships and work practices.

Wanting in The literature indicates that students in secondary schools like having

the opportunity to be involved in schooling in ways that transcend classroom

activities and the learning of academic work (Furtwengler, 1985a, 1991; Lewis

1995). Students enjoy the responsibility provided by these opportunities and want

the power to influence school decision making (Connors & Epstein, 1994). At

Barracks, a dimension labelled 'wanting in' was identified which describes this feel-

ing among some students and teachers who wanted to have real power in the

school by being part of meaningful processes of decision making and change.

Wanting in was a strong desire to be involved in change, a belief by participants

that they had the right to participate, and a tenacity to persist in the face of diffi-

culties. Few students and teachers displayed this characteristic: in the face of other

cultural dimensions at Barracks, many students and teachers settled into relatively

non-participatory routines. The importance of wanting in for student participation

was that those few students with this strong desire provided the potential leader-

ship for student government at Barracks, taking the initiative and persuading

teachers to work for student agendas.

Framework for building student participation

Cultural dimensions at Barracks High represent a complex ecology in which the

beliefs and attitudes of individuals interacted with various structural and proced-

ural constraints in the school, and acted to inhibit participation. Teachers and

administrators did not see student participation as a priority. Added to this belief

were other general beliefs about teachers, teaching and education which existed at

Barracks-the importance of academic (as opposed to applied) work, concerns

about discipline and student appearance, and the feeling that students should fit

into the traditional paradigm of secondary schooling. These beliefs were set against

94 Australian Journal ofEducation

structural features of the school which also militated against participation-s-

the dominance of the principal in decision making, the fragmentation between

faculties and within school development structures, and the lack of leadership in

developing effective student learning.

Those dimensions which acted to enhance participation came from the realm

of participant beliefs, values and actions. None of the enhancing dimensions can

be regarded as structural: there were no entrenched processes or policies at

Barracks that promoted student participation, no common approaches that

endorsed active learning, no strategies to guarantee student decision making.

Enhancing dimensions depended upon the beliefs and agency of individuals.

Unfortunately individual students, like teachers, found the dimensions that inhib-

ited general and student participation too pervasive to overcome. This raises a

critical issue for student participation at Barracks and in other secondary schools:

the issue of how to foster individual agency in an organisational context.

A sense of agency, or autonomous action in human beings (Bandura, 1986),

triggers participation. Bandura (1986) suggested this is true of both children and

adults. When human beings achieve success through participation, their feelings of

self-efficacy rise. 'The stronger their feelings of self-efficacy', wrote Bandura

(1986), 'the more vigorous and persistent are their efforts' (p. 394). A lack of these

feelings triggers non-participation. Bandura drew similar conclusions about agency

among children and adolescents, suggesting that young people in schools often lose

motivation and agency because school 'all too often ... undermines the very sense

of personal efficacy needed for recurring self-development' (p. 416). Argyris (1993)

found it common for organisational leaders to espouse the rhetoric of participation

in organisations while engaging in behaviors which acted against participation. The

solution, suggested Argyris, was to 'create a new theory of action [which] would

facilitate learning at all levels, ... drastically reduce their organizational defensive

routines and ... build routines for effective organizational learning' (pp. 4-5). The

concept of organisational learning has application to this study. To increase agency

among their student and teacher stakeholders, schools need to construct themselves

as effective learning organisations which stress collaborative communities working

in critical, participatory and supportive relationships (Astuto & Clark, 1995;

Burkhardt, Petri, & Roody, 1995; Fullan, 1995; Hough & Paine, 1997). Such

learning communities need to be inclusive of students.

The Barracks High School culture was unique. Despite its uniqueness, there

is considerable congruence between the dimensions identified at Barracks and

those found in the literature to describe the general culture of secondary schools.

In many ways, Barracks High can be considered typical. Therefore, although the

findings of single-site case study research may often be inapplicable to other set-

tings (Lincoln & Guba, 1985), there are cases in which findings may be generalised

(Sturman, 1994) and, in this study, they can be tentatively applied to suggest a

framework for building meaningful participation in secondary schools.

At Barracks, the majority of dimensions acted to inhibit student (and indeed

teacher) participation. Any framework proposing to build participation in schools

needs to build on dimensions which enhance participation and respond to those

dimensions which act as inhibitors. By using the clusters of dimensions identified

Student panicipation and school culture 95

in this study, it is possible to conceive of a framework of principles and strategies

which would help to establish collaborative learning cultures in schools which

could facilitate meaningful student participation. This framework is outlined in

Figure 2. The framework rests on the assumption, arising from this study, that

meaningful student participation in schools depends upon creating conditions

which support participation by teachers and students alike.

The strategies outlined in Figure 2 are underpinned by a fundamental

premise, reinforced in this study, that student learning should be the core purpose

of schools and represents the most potent means of providing opportunities for

student participation. The actual learning experiences of students need to be the

central consideration of schools if participation is to be meaningful. Secondary

schools need to reflect a concern with appraising existing practices in student learn-

ing and with continuously developing new practices. This should be done with

students as participants whose voices are valued. Because school curriculum and

teaching cultures are powerful determinants of the quali ty of the school experience

for students, in an effective learning community students will have representation

at all levels where curriculum decisions are made, including faculty discussions,

inter-faculty discussions and at whole school meetings. Regular amounts of class-

room time should also be devoted to discussions of curriculum, teaching and learn-

ing issues which can involve all students (Glasser, 1990). Further strategies in

Figure 2 place students as participants in school political processes which give them

access to school decision-making forums, integrate the SRC into school decision-

making processes, allow students to select or elect their own advisers, and which

encourage students to say what they think. Schools operating as genuine pro-

moters of student participation are also likely to implement participatory

approaches to school change and development, including open and problem-based

approaches to school development (Robinson, 1993) which explicitly target

school purposes, external constraints and pressures acting on schools.

To promote environments which in turn promote meaningful participation

for young people, school leaders must manage both 'bottom-up' and 'top-down'

processes of planning, provide scaffolding so both teachers and students can

develop the confidence and skills to enable them to participate and, through clear,

understandable forward plans and communication, provide participants with an

informed basis on which to participate. In this way, participation may be accepted

by participants as a genuine opportunity to contribute their voices to school

development, and school leaders have an essential role to play in facilitating this

environment. There is evidence, in this study and in other literature (Gabella,

1995; Harris, 1994), that young people positively change their attitudes to school-

ing when supported by engaging school practices. It is important for school

leaders to model behaviours of openness and inclusion. It is also important for

teachers and other participants to enact values that communicate a caring about

and trust of students and each other. Communicating that all participants can

achieve and are capable of success is also important, and can be achieved through

strategies such as celebrating the success of student learning at every level, and

celebrating successful teaching practices.

96 Australian Journal ofEducation

Strategies for the socio-political dimension

• clear processes to encourage students to say what they think about all aspects of school life;

• student representation in all school forums and committees and on each faculty;

• student government bodies have equal status with other organisational groups and equal

access to decision making;

• student involvement in appointment or election of teacher advisers on student bodies;

• student learning experiences are the focus of all planning;

• 'open' and problem-based approaches to organisational problem solving and decision making

(Robinson, 1993);

• school ethos and underpinning values continually discussed and developed by all stakeholders,

including students;

• external constraints and pressures are identified, discussed and responded to in the context

of formal planning;

• integrated 'bottom up' and 'top down' approaches to planning and school development

processes;

• targeted scaffolding is available for teachers and students involved in school development;

• clear communication about forward plans, etc.

Strategies for the curricular dimension

• student representatives involved in all discussions about learning experiences and curriculum

in faculty meetings, whole-school meetings and committees;

• regular discussions in all classrooms about learning and learning experiences, including class-

room-based student participation in curriculum negotiation and decision making;

• provision of academic credit for student representation in school governance;

• student learning experiences are the focus of all planning;

• consistent, planned discussion about student learning occurs in faculties;

• consistent, planned discussion about student learning occurs between faculties;

• curriculum development is secondary to the development of effective learning experiences;

• use of active learning approaches including problem solving, experimentation, research, use of

non print-based resources and activities, discussion and cooperative learning;

• 'bottom-up' and 'top-down' processes of developing learning experiences and curriculum;

• scaffolding for teachers and students in techniques for promoting and valuing student voices,

including developing critical thinking and discussion skills.

Strategies for the personal-participant dimension

• school leaders model organisational and personal tenets of schools as learning organisations;

• teachers resolve to value all students as learners and to challenge them to learn;

• celebratory perspectives of youth are developed by celebrating academic achievements of the

full range of students, and by celebrating student successes achieved outside of school;

• teachers resolve to talk to students about themselves and their worlds; they look to connect

the meaning of academic work to the personal worlds of students;

• all participants encourage trust and openness in dialogue between students and other

participants; they discourage arbitrary resorts to power and status;

• encourage the belief in all participants that their ideas have value, are valued by the

organisation, and can make a difference.

Note: It is difficultfor schools to enact strategies to influence the beliefs and attitudes of participants.

Generally, experience of efficacious new approaches will encourage teachers to change their beliefs (Fullan,

1983), as will collaborative approaches of critique and dialogue within supportive groups of teachers (Nias,

1987). Such strategies are believed to be natural outcomes of the socio-political and curricular dimensions

of schools as participatory organisations.

Figure 2 A framework of principles and strategies for building participation

in secondary schools

Student participation and school culture 97

Had such principles and practices for building student participation guided

school development at Barracks High, it would probably have contributed to

increased agency and motivation among participants at Barracks, led to more

meaningful forms of participation by students and teachers, and to enhanced learn-

ing outcomes for students. It is something that should be considered and taken

seriously by secondary schools. Only by including students as meaningful partici-

pants in the learning community of their school are we likely to resolve issues of

decreasing motivation and academic performance amongst young people in the

secondary school years.

Keywords

educational environment school organisation student participation

qualitative research secondary school curriculum teaching process

References

Abbott-Chapman,]., Hughes, P., Holloway, G., & Wyld, C. (1990). Identifying the quali-

ties and characteristics of the 'effective' teacher. Hobart: University of Tasmania, Youth

Education Studies Centre.

Ainley, J. & Sheret, M. (1992). Progress through high school: A study of senior secondary school-

ing in New South Wales (ACER Research Monograph No. 43). Hawthorn, Vic:

Australian Council for Educational Research.

Argyris, C. (1993). Knowledge for action. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Argyris, C. & Schon, D. (1996). Organizational learning II. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Astuto, T.A. & Clark, D.L. (1995). Activators and impediments to learner-centred schools.

Theory into Practice, 34(4), 243-249.

Australian Curriculum Studies Association. (1995). The middle years of schooling and

student alienation: News Sheet, June 1995. [Insert, 4 pp.] Curriculum Perspectives,

15(2).

Ball, S.]. & Bowe, R. (1992). Micropolitics of radical change: Budgets, management and

control in British schools. In J. Blase (Ed.), The politics of life in schools: Power, conflict

and cooperation. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Bandura, A. (1986). Socialfoundations cifthought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-

Hall.

Beiser, M., Lancee, W., Gotowiec, A., Sack, W., & Redshirt, R. (1993). Measuring self-

perceived role competence among 1st nations and nonnative children. Canadian

Journal of Psychiatry, 38,412-419.

Blase,].]. (1990). Some negative effects of principals' control-oriented behaviour and

protective political behaviour. American Educational Research Journal, 27, 727-753.

Boomer, G., Lester, L., Onore, C., & Cook,]. (1992). Negotiating the curriculum: Educating

for the 21st century. London: Falmer Press.

Broadfoot, P. (1991). Assessment: A celebration of learning (ACSA Working Report No.1).

Canberra: Australian Curriculum Studies Association.

Bruner, ].S. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Burkhardt. G., Petri, M., & Roody, D.S. (1995). The kite: An organizational frame-

work for educational development in schools. Theory into Practice, 34(4),

272-278.

98 Australian Journal ofEducation

Cairney, T.H., Hayward-Brown, H., Craigie, D., Dinham, S., Jaffe, D., Khamis,

M., Nolan, B., Richards, J., & Wilson, S. (1992). The school and community intefacc:

A study of communication in comprehensive h~'Sh schools (3 vols.). Sydney: University of

Western Sydney, Nepean.

Cohen, D. & Harrison, M. (1982). Curriculum Action Project: A report on curriculum decision

making in Australian schools (Vol. 1). Sydney: Macquarie University.

Cohn, M.M. & Kottkamp, R.B. (1993). Teachers: The missing voice in education. Albany,

NY: SUNY Press.

Connell, R.W. (1994). Poverty and education. Harvard Educational Review, 64,125-149.

Connors, L.J. & Epstein, J.L. (1994). Taking stock: Views oj teachers, parents and students on

school, Jamily and community partnerships on high schools (Report No. 25). Baltimore,

MD: Johns Hopkins University, Center on Families, Communities, Schools and

Children's Learning.

Cooper, M.H. & Good, T.L. (1983). Pygmalion grows up. New York: Longman.

Cumming, J. (1994). Educating young adolescents: Targets and strategies for the 1990s.

Curriculum Perspectives, 14(3), 41-44.

Cumming, J. (1996). From alienation to engagement: Opportunities Jor refon« in the middle years

oj schooling (Vol. 3). Canberra: Australian Curriculum Studies Association.

Cummins, J. (1997). Cultural and linguistic diversity in education: A mainstream issue?

Educational Review, 49(2), 105-114.

Daugherty, R. (1995, April). 'It's not his project. It's ours': The importance of ownership.

Connect, No.92, pp. 12-13.

Dellar, G.B. (1992). Connections between macro and micro implementation oj educational policy:

A study oj school restructuring in Western Australia. Paper presented at the Annual

Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, April

20-24.

Dinham, S. (1993). Teachers under stress. Australian Educational Researcher, 20(3), 36-58.

Dinham, S. (1995). Time to focus on teacher satisfaction. Unicorn, 21(3), 64-75.

Disadvantaged Schools Program. (1992). The Follow-On Project, 1991-92. Sydney:

Department of School Education.

Edwards,J. (1995). Teaching thinking in schools: An overview. Unicorn, 21(1),27-36.

Eisner, E.W. (1988). The ecology of school improvement. Educational Leadership, 45(5),

24-29.

Farrell, E., Peguero, G., Lindsey, R., & White, R. (1988). Giving voice to high school

students: Pressure and boredom, ya know what I'm sayin'? American Educational

ResearchJournal, 25, 489-502.

Fraatz, J.M. (1987). The politics if reading: Power, opportunity and prospects Jor change in

America's public schools. New York: Teachers College Press.

Freeston, K.R. (1993). Quality is not a quick fix. Clearing House, 66,344-348.

Fullan, M. (1983). The meaning if educational change. New York: OISE Press Education.

Fullan, M. (1991). The new meaning if educational change. New York: Teachers College

Press.

Fullan, M. (1995). The school as a learning organization: Distant dreams. Theory into

Practice, 34(4), 230-235.

Fullan, M. & Hargreaves, A. (1991). What's worthfightingJor: Working togetherJor yourschool.

Hawthorn, Vic.: Australian Council for Educational Administration.

Furtwengler, W.J. (1985a). Implementing strategies Jor a school ifJectiveness program. Paper pre-

sented at the Annual Meeting of the American Association of School Administrators,

Dallas, Texas, March 8-11.

Student participation and school culture 99

Furtwengler, W.J. (1985b, December). Implementing strategies for a school effectiveness

program. Phi Delta Kappan, pp. 262-265.

Furtwengler, W.J. (1991). Reducing student behaviour through student involvement in school

restructuring processes. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American

Educational Research Association, Chicago, April 3-7.

Gabella, M.S. (1995). Unlearning certainty: Toward a culture of student inquiry. Theory

into Practice, 34, 236-242.

Gibson-Cline, J. (1996). Adolescence from crisis to coping: A thirteen nation study. Oxford:

Butterworth Heinemann.

Glasser, W. (1990). The quality school: Managing students without coercion. New York: Harper

Collins.

Guba, E.G. & Lincoln, Y.S. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation. Newbury Park, CA: Sage

Publications.

Habermas, J. (1972). Knowledge and human interests. London: Heinemann.

Habermas, J. (1990). Moral consciousness and communicative action (Christian Lenhardt &

Shierry Weber Nicholson, Trans.). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Habermas, J. (1993). Justification and application (Ciaran Cronin, Trans.). Cambridge: Polity

Press.

Hargreaves, A. (1992). Contrived collegiality: The micropolitics of teacher collaboration.

In J. Blase (Ed.), The politics of life in schools: Power, conflict and cooperation. Newbury

Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Hargreaves, A. (1994). Changing teacher, changing times: Teachers' work and culture in the post-

modern age. London: Cassell.

Hargreaves, A. & Earl, L. (1994). Triple transitions: Educating early adolescents in the

changing Canadian context. Curriculum Perspectives, 14(3),1-9.

Harris, K. (1994). Bridgetown High School: A vision driven middle school. Curriculum

Perspectives, 14(3), 46-48.

Holdsworth, R. (1988). Student participation projects in Australia: An anecdotal history.

In R. Slee (Ed.), Discipline and schools: A curriculum perspective. Melbourne: Macmillan.

Holdsworth, R. (1996). What do we mean by student participation? Youth Studies

Australia, 15(1),26-27.

Holdsworth, R. (1997, April). Student participation, connectedness and citizenship.

Connect, No. 104, pp. 17-21.

Hough, M. & Paine, J. (1997). Creating quality learning communities. South Melbourne:

Macmillan Education Australia.

Hughes, G. (1994). The normative dimensions of teacher/student interaction. South Pacific

Journal if Teacher Education, 22, 189-205.

Kelley, D.M. (1993). Secondary power source: High school students as participatory

researchers. American Sociologist, 24(1), 8-26.

Kemmis, S., Cole, P., & Suggett, D. (1983). Orientations to curriculum and transition: Towards

the socially critical school. Melbourne: VISE.

Kempa, R.F. & Orion, N. (1996). Students' perceptions of cooperative learning in earth

science fieldwork. Research in Science and Technological Education, 14, 33-41.

Larson, R.L. (1992). Changing schools from the inside out. Lancaster: Technomic Publishing

Co.

Levin, B. (1994). Putting students at the center. Phi Delta Kappan, 75,758-60.

Lewis, T. (1995, October-December). Power sharing means prosperity at NightcliffHigh.

Connect, No. 95-96, pp. 25-26.

Lincoln, Y.S., & Guba, E.G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

100 Australian Journal of Education

McNeil, L.M. (1988a, .January). Contradictions of control, Part 1: Administrators and

teachers. Phi Delta Kappan, pp. 333-339.

McNeil, L.M. (1988b, February). Contradictions of control, Part 2: Teachers, students and

curriculum. Phi Delta Kappan, pp. 432-439.

Meade, P. (1983). The educational experience of Sydney high school students (Report No.3).

Canberra: AGPS.

Merriam, S.B. (1988). Case study research in education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

National Association of Secondary School Principals. (1989). Student council handbook.

Reston, VA: NASSP Division of Student Activities.

National Board of Employment, Education and Training. (1993). In the middle: Schooling

for young adolescents (project Paper No.7). Canberra: AGPS.

Nayano-Taylor, L.V. (1987). "It's like being in brackets": Students' perceptions of school

committees. Bulletin of the National Clearinghouse for Youth Studies, 6(2), 2-6.

Nias, J. (1987). Seeing anew: Teachers' theories of action. Geelong: Deakin University Press.

Nieto, S. (1994). Lessons from students on creating a chance to dream. Harvard Educational

Review, 64, 392-426.

Nixon, J. (1996). Encouraging learning: Towards a theory cif the learning school. Bristol, PA:

Open University Press.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (1989). Schools and quality:

An international report. Paris: Author.