Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Topic Outline of Doctrine of State Immunity On Suits - Dano Charrise PDF

Uploaded by

Charrise DanoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Topic Outline of Doctrine of State Immunity On Suits - Dano Charrise PDF

Uploaded by

Charrise DanoCopyright:

Available Formats

DANO, CHARRISE B. JD 1.

5A

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1 - 9AM - 12NN

Immunity from Suit

The principle enshrined in Section 3, Article XVI of the Constitution which provides that the

“State may not be sued without its consent” reflects nothing less than a recognition of the

sovereign character of the State and an express affirmation of the unwritten rule effectively

insulating it from the jurisdiction of courts. It is based on the very essence of sovereignty.

(Department of Agriculture v. NLRC, 227 SCRA 693[1993])

A sovereign is exempt from suit, not because of any formal conception or obsolete theory,

but on the logical and practical ground that there can be no legal right as against the

authority that makes the law on which the right depends.

(Republic v. Sandoval, 220 SCRA 124 [1993])

It also rests on reasons of public policy—that public service would be hindered, and the

public endangered, if the sovereign authority could be subjected to lawsuits at the instance

of every citizen and consequently controlled in the uses and dispositions of the means

required for the proper administration of the government.

(The Holy See v. Rosario Jr., 228 SCRA 524 [1994])

The doctrine of sovereign immunity from suit may be invoked by any foreign state when it is

sued in the country just as the Philippines may invoke sovereign immunity from suit filed in

a foreign country, and except when it waives it, the suit will fail.

The doctrine, which says, “the state may not be sued without its consent” is clear that the

State may be sued, with its consent, either expressly or impliedly. Express consent may be

made through a general law or a special law.

The Philippine government consents, through Republic Act (RA) 3083, to be sued upon any

money claim involving liability arising from contract, expressly or implied, which could serve

as a basis of civil action between private parties.

Implied consent, on the other hand, arises when the State itself commences litigation, thus

opening itself to a counterclaim, or when it enters into a contract in its proprietary capacity

but not in its sovereign or governmental capacity. In this situation, the government is

deemed to have descended to the level of the other contracting party and to have divested

itself of its sovereign immunity.

(Republic v. Sandiganbayan, 204 SCRA 212 [1991])

When the state itself commences litigation, irrespective of whether or not it is in its

proprietary or non-governmental capacity, it waives its immunity from suit.

(Traders Royal Bank v. IAC, 192 SCRA 305 [1990])

A State may be said to have descended to the level of an individual and can thus be deemed

to have tacitly given its consent only when it enters into a business contract. It does not

apply where the contract relates to the exercise of its sovereign functions. In other words,

the test is not the conclusion of a contract by the state but by the legal nature of the act.

Thus, it has been held that there is no waiver of state immunity where the contract is a

necessary incident of its prime government function.

(Philippine National Railways v. IAC, 217 SCRA 401 [1993])

By engaging in a particular business through a governmental agency or corporation, the

state divests itself of its sovereign character and makes itself amenable to suit, for in the

conduct of such business, there can be no one law for the sovereign and another for the

subject, and both should stand upon equally before the law.

The doctrine of state immunity from suit is also applicable to complaints filed against

officials of the state for acts performed by them in the discharge of their duties. A public

officer who is sued in connection with the performance of his duties may properly invoke

the doctrine, when the suit is on its face against a government officer but the case is such

that ultimate liability will belong not to the officer but to the government.

(United States of America v. Reyes, 219 SCRA 192 [1993])

The rule is that if the judgment against such official will require the state itself to perform an

affirmative act to satisfy the same, such as the appropriation of the amount needed to pay

the damages awarded against him, the suit must be regarded as against the state itself

although it has not been formally impleaded .

In short, there can be no execution of judgment against government funds or properties.

The claim should be presented for payment with the Commission on Audit.

This rule is, however, subject to exception, such as when the official is sued in his personal

or private capacity for acts done with malice or in bad faith, or when the official does

unauthorized or illegal acts or goes beyond the scope of his authority, or commits a crime,

in which case, the principle of state immunity from suit does not apply and the official

concerned may be held personally liable therefor.

(Lansang v. CA, 326 SCRA 259 [2000])

The rule does not apply where the public official is charged in his official capacity for acts

that are unlawful and injurious to the rights of others. Public officials are not exempt, in

their personal capacity, from liability arising from acts committed in bad faith.

For the doctrine of state immunity cannot be used as an instrument for perpetrating an

injustice. High position in the government does not confer a license to persecute or

recklessly injure another (Shauf v. Court of Appeals, 191 SCRA 713 [1990]).

For a public official may be made to account in his personal capacity for acts contrary to law

and injurious to the rights of the complainant, because illegal or unauthorized acts of

officers are not acts of the state (Begosa v. Phil. Veterans Adm, 32 SCRA 466 [1970]).

You might also like

- Doctrine of StateDocument3 pagesDoctrine of StateElmer UrmatamNo ratings yet

- State ImmunityDocument43 pagesState ImmunityRheyz Pierce A. CampilanNo ratings yet

- State Immunity From Suit:: A Basic GuideDocument16 pagesState Immunity From Suit:: A Basic GuideJezen Esther PatiNo ratings yet

- State Immunity From SuitDocument18 pagesState Immunity From SuitNufa AlyhaNo ratings yet

- State Immunity From SuitDocument18 pagesState Immunity From SuitGlo Allen Cruz100% (2)

- State Immunity From Suit:: A Basic GuideDocument17 pagesState Immunity From Suit:: A Basic GuideYet Barreda BasbasNo ratings yet

- Immunity From SuitDocument4 pagesImmunity From SuitBon Hart100% (1)

- Immunity From SuitsDocument4 pagesImmunity From Suitsferosiac0% (1)

- 2023 Political LawDocument18 pages2023 Political LawAiza Cabenian100% (1)

- Constitutional Law 1 File No 2Document22 pagesConstitutional Law 1 File No 2Seit DyNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of State Immunity From SuitDocument7 pagesDoctrine of State Immunity From SuitHeehyo Song100% (1)

- USA V. GUINTO (1990) Doctrine of State ImmunityDocument3 pagesUSA V. GUINTO (1990) Doctrine of State ImmunityFlorencio Saministrado Jr.No ratings yet

- Doctrine of State ImmunityDocument5 pagesDoctrine of State ImmunityMeah BrusolaNo ratings yet

- State Immunity and ExceptionsDocument5 pagesState Immunity and ExceptionsLENNY ANN ESTOPINNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4: The Doctrine of State Immunity BasisDocument2 pagesChapter 4: The Doctrine of State Immunity Basisthea mae patricioNo ratings yet

- State Immunity Doctrine ExplainedDocument24 pagesState Immunity Doctrine ExplainedOjo San JuanNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law 1 - File No. 2Document22 pagesConstitutional Law 1 - File No. 2priam gabriel d salidaga78% (9)

- Department of Agriculture Vs NLRC GR No. 104269 Nov 11, 1993Document6 pagesDepartment of Agriculture Vs NLRC GR No. 104269 Nov 11, 1993Lourd CellNo ratings yet

- Arigo vs. Swift - Pil TopicDocument6 pagesArigo vs. Swift - Pil TopicMay Ann BorlonganNo ratings yet

- MODULE 3 REVIEWER: STATE IMMUNITY FROM SUITDocument3 pagesMODULE 3 REVIEWER: STATE IMMUNITY FROM SUITFritzie G. PuctiyaoNo ratings yet

- Department of Agriculture Vs NLRC GR No. 104269 Nov 11, 1993Document6 pagesDepartment of Agriculture Vs NLRC GR No. 104269 Nov 11, 1993Lourd CellNo ratings yet

- No.2-DOCTRINE OF STATE IMMUNITYDocument17 pagesNo.2-DOCTRINE OF STATE IMMUNITYrejine mondragonNo ratings yet

- Seatwork - Consti Law1 - State ImmunityDocument2 pagesSeatwork - Consti Law1 - State Immunitytequila0443No ratings yet

- Session 3 - State Immunity From SuitDocument64 pagesSession 3 - State Immunity From SuitRon Ico RamosNo ratings yet

- No.4-SEPARATION OF POWERSDocument17 pagesNo.4-SEPARATION OF POWERSrejine mondragonNo ratings yet

- Suability DOA Vs NLRCDocument4 pagesSuability DOA Vs NLRCVon Ember Mc MariusNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of State ImmunityDocument1 pageDoctrine of State Immunitylady_erzaNo ratings yet

- No.5-DELEGATION OF POWERSDocument20 pagesNo.5-DELEGATION OF POWERSrejine mondragonNo ratings yet

- 26 Jusmag Philippines vs. NLRCDocument2 pages26 Jusmag Philippines vs. NLRCMavic Morales100% (3)

- 2017 SC Cases-Political LawDocument86 pages2017 SC Cases-Political LawMatthew Witt100% (1)

- In Summary - Chapter 4: The Doctrine of State Immunity: Political Law September 23, 2017Document23 pagesIn Summary - Chapter 4: The Doctrine of State Immunity: Political Law September 23, 2017Ghatz CondaNo ratings yet

- Digest Const ImmunityDocument25 pagesDigest Const ImmunitySapphireNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 - Doctrine of State ImmunityDocument2 pagesChapter 4 - Doctrine of State ImmunityAaron Te100% (4)

- Wylie Vs RarangDocument12 pagesWylie Vs Raranglovekimsohyun89No ratings yet

- Philippine Agila Satellite Vs Trinidad LichaucoDocument3 pagesPhilippine Agila Satellite Vs Trinidad LichaucoJoshua L. De JesusNo ratings yet

- Immunity From Suit 1 1Document22 pagesImmunity From Suit 1 1HGNo ratings yet

- Module 2 Doctrine of Non-Suability of StateDocument7 pagesModule 2 Doctrine of Non-Suability of StateJulius Carmona GregoNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of State ImmunityDocument2 pagesDoctrine of State ImmunityJae Kkim BefinosaNo ratings yet

- State Immunity from Suit Doctrine ExplainedDocument5 pagesState Immunity from Suit Doctrine ExplainedAIL REGINE REY MABIDANo ratings yet

- Doctrine of State ImmunityDocument8 pagesDoctrine of State ImmunitySesshy TaishoNo ratings yet

- State Immunity Notes: Key Cases on Sovereign ImmunityDocument34 pagesState Immunity Notes: Key Cases on Sovereign ImmunityBo Dist50% (2)

- Suit Against The StateDocument4 pagesSuit Against The Stateunbeatable38100% (1)

- Sovereign Immunity Protects State in Labor DisputeDocument3 pagesSovereign Immunity Protects State in Labor DisputeAngelo Raphael B. DelmundoNo ratings yet

- Political Law 082422 2nd DiscussionDocument7 pagesPolitical Law 082422 2nd DiscussionHafisah PangarunganNo ratings yet

- Political Law Constitutional Law General Considerations State ImmunityDocument2 pagesPolitical Law Constitutional Law General Considerations State ImmunityCastillo Anunciacion IsabelNo ratings yet

- DOA Vs NLRCDocument2 pagesDOA Vs NLRCDura Lex Sed LexNo ratings yet

- Doh v. Phil. Pharmawealth, IncDocument2 pagesDoh v. Phil. Pharmawealth, Incgherold benitezNo ratings yet

- Dept. of Agriculture v. NLRC PDFDocument8 pagesDept. of Agriculture v. NLRC PDFcarla_cariaga_2No ratings yet

- 128385-1993-Department of Agriculture v. National Labor20160322-9941-N9xdh7Document8 pages128385-1993-Department of Agriculture v. National Labor20160322-9941-N9xdh7Ariel MolinaNo ratings yet

- Compilation of Case Digests For Consti 2 (Execution Copy)Document259 pagesCompilation of Case Digests For Consti 2 (Execution Copy)DMRNo ratings yet

- In Re Raul GonzalesDocument5 pagesIn Re Raul Gonzalesmau_cajipe100% (1)

- Da Vs NLRCDocument1 pageDa Vs NLRCEmma Ruby Aguilar-ApradoNo ratings yet

- Article Xvi General ProvisionsDocument45 pagesArticle Xvi General Provisions'Bernan Esguerra BumatayNo ratings yet

- State ImmunityDocument4 pagesState Immunityarlynndumlao9No ratings yet

- Article XviDocument4 pagesArticle XviALBERT JOHN ZAMARNo ratings yet

- G2 State-Immunity-OutlineDocument3 pagesG2 State-Immunity-OutlineRhona De JuanNo ratings yet

- 13 128385-1993-Department - of - Agriculture - v. - National - Labor20181114-5466-1anm1pg PDFDocument8 pages13 128385-1993-Department - of - Agriculture - v. - National - Labor20181114-5466-1anm1pg PDFJM CamposNo ratings yet

- Asian Transmission Corporation vs. CADocument1 pageAsian Transmission Corporation vs. CACharrise DanoNo ratings yet

- Capitol vs. MerisDocument1 pageCapitol vs. MerisCharrise DanoNo ratings yet

- ANFLO MANAGEMENT & INVESTMENT CORP vs. BolanioDocument1 pageANFLO MANAGEMENT & INVESTMENT CORP vs. BolanioCharrise DanoNo ratings yet

- ZAMBRANO v. PHILIPPINE CARPET MANU. CORPDocument1 pageZAMBRANO v. PHILIPPINE CARPET MANU. CORPCharrise DanoNo ratings yet

- Catotocan vs. Lourdes School of QCDocument1 pageCatotocan vs. Lourdes School of QCCharrise DanoNo ratings yet

- NTN Bearings CatDocument105 pagesNTN Bearings CatlowelowelNo ratings yet

- Godin V London InsuranceDocument10 pagesGodin V London InsurancePranav TanwarNo ratings yet

- 6) Case Digest of Wildvalley Shipping LTDDocument2 pages6) Case Digest of Wildvalley Shipping LTDKhing Guitarte100% (2)

- Radio Communications of The Philippines Vs National Telecommunications CommissionDocument1 pageRadio Communications of The Philippines Vs National Telecommunications CommissionMae Clare D. BendoNo ratings yet

- A.C. No. 4545, February 05, 2014 - Carlito Ang, Complainant, V. Atty. James Joseph Gupana, Respondent. - February 2014 - Philippine Supreme Court Jurisprudence - Chanrobles Virtual Law LibraryDocument7 pagesA.C. No. 4545, February 05, 2014 - Carlito Ang, Complainant, V. Atty. James Joseph Gupana, Respondent. - February 2014 - Philippine Supreme Court Jurisprudence - Chanrobles Virtual Law LibraryFritch GamNo ratings yet

- Montinola Vs PALDocument5 pagesMontinola Vs PALMary Genelle CleofasNo ratings yet

- Tanada vs. Tuvera Case DigestDocument2 pagesTanada vs. Tuvera Case DigestMay Elaine Belgado50% (2)

- Lorenzo Lim vs. Dela RosaDocument1 pageLorenzo Lim vs. Dela RosamoesmilesNo ratings yet

- GI 2020 - RespondentDocument20 pagesGI 2020 - Respondentsimran yadavNo ratings yet

- ObliCon Workshop Questions AnsweredDocument11 pagesObliCon Workshop Questions AnsweredAnonymous abx5ZiifyNo ratings yet

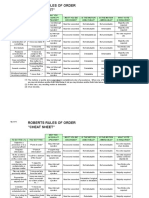

- Roberts Rules of Order "Cheat Sheet"Document2 pagesRoberts Rules of Order "Cheat Sheet"Mic DNo ratings yet

- M/S Hyder Consulting (Uk) LTD Vs Governer State of Orissa TR - Chief ... On 25 November, 2014Document26 pagesM/S Hyder Consulting (Uk) LTD Vs Governer State of Orissa TR - Chief ... On 25 November, 2014Dilip KumarNo ratings yet

- Case Digest Property Public DominionDocument18 pagesCase Digest Property Public DominionNJ GeertsNo ratings yet

- United States Bankruptcy Court For The District of Delaware: This Of: /L/, - JDocument3 pagesUnited States Bankruptcy Court For The District of Delaware: This Of: /L/, - JChapter 11 DocketsNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 161135. April 8, 2005 Swagman Hotels and Travel, Inc., Petitioners, Hon. Court of Appeals, and Neal B. Christian, RespondentsDocument12 pagesG.R. No. 161135. April 8, 2005 Swagman Hotels and Travel, Inc., Petitioners, Hon. Court of Appeals, and Neal B. Christian, RespondentszNo ratings yet

- Bar Exam Leakage and Lawyer MisconductDocument19 pagesBar Exam Leakage and Lawyer MisconductNestNo ratings yet

- 033 Manalo Vs Robles Transportation Company - Jet SiangDocument2 pages033 Manalo Vs Robles Transportation Company - Jet SiangJet SiangNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Extremadura v. Extremadura G.R. No. 211065 - June 15, 2016 FACTS: Jose, Now Deceased, Filed A Case For Quieting of Title With Recovery ofDocument1 pageHeirs of Extremadura v. Extremadura G.R. No. 211065 - June 15, 2016 FACTS: Jose, Now Deceased, Filed A Case For Quieting of Title With Recovery ofJed MacaibayNo ratings yet

- BAB2202LAW 2034 Company Law Subject Overview - 2013Document8 pagesBAB2202LAW 2034 Company Law Subject Overview - 2013Gurrajvin SinghNo ratings yet

- Rep. Colton Moore Speaker Resignation LetterDocument27 pagesRep. Colton Moore Speaker Resignation LetterColton MooreNo ratings yet

- Bolichicos NUNCA Arriesgaron Ni Un Centimo. CREDITO DE VENTAS DE PDVSADocument5 pagesBolichicos NUNCA Arriesgaron Ni Un Centimo. CREDITO DE VENTAS DE PDVSATomás LanderNo ratings yet

- RTC jurisdiction over civil & criminal casesDocument2 pagesRTC jurisdiction over civil & criminal casesERNEST ELACH ELEAZARNo ratings yet

- Chua Yung Kim V Madlis Bin Azid at Aziz & OrsDocument21 pagesChua Yung Kim V Madlis Bin Azid at Aziz & OrsAfdhallan syafiqNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 202661Document1 pageG.R. No. 202661alyNo ratings yet

- Corporate Dissolution 2nd PartDocument10 pagesCorporate Dissolution 2nd PartRaymarc Elizer AsuncionNo ratings yet

- Perotti v. Stine - Document No. 3Document18 pagesPerotti v. Stine - Document No. 3Justia.comNo ratings yet

- LHC Judgment Challenges Cancellation of Land Allotment to Displaced PersonsDocument15 pagesLHC Judgment Challenges Cancellation of Land Allotment to Displaced PersonsabbasNo ratings yet

- 09122009MAC APP No 176-2009Document22 pages09122009MAC APP No 176-2009daljitsodhiNo ratings yet

- Amended Complaint 10-11-18Document46 pagesAmended Complaint 10-11-18BM ManagementNo ratings yet

- Montcalm Publishing v. Commonwealth of VA, 4th Cir. (1999)Document10 pagesMontcalm Publishing v. Commonwealth of VA, 4th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet