Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1146 Voicemail Messages

Uploaded by

Deyvered MTOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1146 Voicemail Messages

Uploaded by

Deyvered MTCopyright:

Available Formats

#1146

Fastfax www.acainternational.org/fastfax

_____________________________________________________________________________

Last Updated on May 3, 2011– Added new case law (see footnotes 19, 36-41).

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Leaving Voice Mail Messages for Consumers

The practice of leaving voice mail messages for consumers while attempting to collect a debt is an

important collection method. The legal consequence of leaving messages, however, has received

significant attention from courts across the country in recent years.

Much of the debate surrounding the issue of leaving messages on consumers’ answering machines relates

to an inherent contradiction in the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA), which requires debt

collectors to disclose certain information in any communication with a consumer in an attempt to collect

a debt, and prohibits debt collectors from disclosing information regarding a debt to third parties.

The general court consensus holds leaving a voice message on a consumer’s answering machine for the

purpose of attempting to collect a debt is a “communication” under the Act. As a result, pursuant to §§

806(6) and 807(11), the debt collector must provide meaningful disclosure of its identity and leave the

mini-Miranda disclosure in voice messages left for consumers.

At the same time, however, several courts have ruled stating the mini-Miranda disclosure on a

consumer’s answering machine could cause a third-party disclosure in violation of § 805(b) if someone

other than the consumer listens to the message. These decisions create significant ambiguity about how

debt collectors can continue to use messages as an effective collection tool while complying with the

seemingly contradictory requirements under §§ 805(b), 806(6), and 807(11) of the FDCPA.

A prudent collector who chooses to continue communicating with consumers via voice mail messages

must look to relevant court decisions to determine what constitutes a compliant communication. The

following Fastfax discusses this issue and provides a suggested voice mail message that collectors may

choose to use.

Voice Mails to Consumers are “Communications” under the FDCPA

In the past, it was a standard practice for debt collectors to leave a message on a consumer’s answering

machine that requested a return call from the consumer without disclosing the call was from a debt

collector. This was done to protect the consumer’s privacy and avoid the possibility of the message being

overheard by a third party, which arguably violates the FDCPA’s prohibition on third-party disclosure

under § 805(b).1 Debt collectors assumed a message such as the one discussed above did not qualify as a

“communication” because such a message conveyed no information about the debt.

However, because the FDCPA defines “communication” as “the conveying of information regarding a

debt directly or indirectly to any person through any medium,”2 a voice mail left for a consumer may be a

communication. In support of this assertion, federal courts around the nation have been addressing this

issue, most notably stemming from Foti v. NCO Fin. Sys., Inc.3 In Foti, the court held the mini-Miranda

and meaningful disclosure requirements extend to prerecorded and live messages left on a consumer’s

answering system for the purpose of attempting to collect a debt.

© 2011 ACA International. All Rights Reserved. Page 1 of 11

Specifically in Foti, because the collector’s prerecorded message was left with the consumer after the

initial validation notice was sent, the court determined the message was a subsequent communication.

Section 807(11) requires a debt collector to disclose in communications subsequent to the initial

communication with a consumer that the communication is from a debt collector. Numerous courts have

held the disclosure requirement is satisfied if the debt collector states, "this is a communication from a

debt collector" or if the name of the debt collection agency (as stated in the written or oral

communication) makes clear the communication is from a debt collector. Such information was not

disclosed to the consumer in Foti.

Because the disclosure was lacking, the court asserted a consumer would need to recall she previously

received mail from a debt collection agency in order to recognize the call was from a debt collector. The

court found placing such a burden on the consumer was unreasonable.4 Thus, the court determined the

prerecorded message failed to comply with the requirements of §§ 806(6) and 807(11) of the FDCPA.

Numerous courts have subsequently concurred with Foti concluding a voice mail is a “communication”

under the FDCPA and as a result, such a communication must provide meaningful disclosure of the

caller’s identity (§ 806(6)) and include the mini-Miranda disclosure (§ 807(11)).5 Similarly, a number of

courts have found violations of § 807(11) when the caller did not identify himself as a debt collector in

messages left on a consumer’s voice messaging system, including courts in California, Florida, Georgia,

Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York, Pennsylvania and other federal jurisdictions.6

Additionally, even if a court was to determine a voice mail is not considered a communication under the

FDCPA, there may still be a violation under § 806(6) when a collector fails to provide meaningful

disclosure. Unlike § 807(11), § 806(6) does not use the term communication, but rather refers only to a

debt collector’s “conduct,” including “the placement of telephone calls without meaningful disclosure of

the caller’s identity.7 Therefore, a voice mail would not even necessarily need to be a communication to

support a claim for a violation of § 806(6).

Contradictory Opinions

As noted, the underlying theory behind the aforementioned decisions is a message left for a consumer

regarding the collection of a debt, whether the message simply requests the consumer return a phone call

or otherwise, is a communication under § 803(2) because the message conveys information regarding a

debt “directly or indirectly.” To date, only one court case in the Western District of Oklahoma, Biggs v.

Credit Collections, Inc., has concluded a message is not a communication under the Act where the

message did not convey any information regarding a debt.8

At least one court has explicitly rejected the interpretation adopted in Biggs, stating the decision failed to

recognize the legislative intent of the FDCPA.9 As previously demonstrated, the greater weight of court

authority holds a voice mail is a communication under § 803(2).

One district court in California, however, determined subsequent voice mail messages may not require

the § 807(11) disclosure if the consumer knew the identity of the caller.10 In Reed v. Global Acceptance

Credit Co., the collector’s voice messages in question provided the name of the collector, the name of the

collection agency, the consumer’s account number, and requested a return phone call. The full mini-

Miranda was already provided to the consumer in the initial communication (collection letter).

The court held the facts of the case suggested a least sophisticated consumer would know the message

was from a debt collector because its company name suggested it was a collector. Additionally, the

totality of the circumstances and prior communications, including the fact the debt collector provided the

consumer with verification of the debt, suggested the consumer would know the nature and identity of

the caller in such voice messages.

© 2011 ACA International. All Rights Reserved. Page 2 of 11

Further, the court noted the Ninth Circuit previously held where the consumer already knows the identity

of the debt collector, follow-up notices from the collector are not communications and do not require

compliance with § 807(11) so long as they are not false or misleading.11Accordingly, the court found

factual issues remained as to whether the debt collector failed to adequately disclose the communication

was from a debt collector, and denied the consumer’s motion for summary judgment.

A district court in Florida recently addressed whether a collector who leaves a voice mail on a

consumer’s answering machine without disclosing the call was an attempt to collect a debt was in

violation of the FDCPA when the call was a mere return phone call after the consumer attempted to

contact the agency.12 The court did not affirmatively determine whether the call was in violation of the

FDCPA, as there was a factual dispute as to the collector’s motives in leaving the voice mail.13 The court

stated if the call was a true return phone call, the debt collector’s voice mail would not be a

communication under the FDCPA. However, if the call was an attempt to entice the consumer to call

back the agency as an attempt to collect a debt, the voice mail would be deemed a communication in

violation of the FDCPA by failing to provide the proper disclosure.14

To add another wrinkle to the analysis of voice mail messages, a different district court in Florida found

a message that did not provide the mini-Miranda disclosure but stated an alias for the individual

collector’s name and disclosed the name of the agency did not violate the FDCPA. Significantly, the

message disclosed the name of the collection agency which included the words “Collection Bureau.”15

The court observed the messages used an alias for the name of the individual collector, but also disclosed

the call was from a “Collection Bureau,” and also referred to a file number. The court noted the

beginning of the message instructed the recipient to cease listening to the call if he or she was not the

consumer named in the message. The court found the use of the alias by the collector did not violate

§ 806(6) because the message also disclosed the call was from a “Collection Bureau.” Likewise, the court

noted an unsophisticated consumer would not be misled as to the purpose of the call when the caller’s

name includes the term “Collection Bureau,” the message refers to a file number and the beginning of the

message also instructs the caller to disconnect if the recipient is not the consumer named in the message.

Looking at the contents of the massage as a whole, the court determined the message did not violate §§

806(6) and 807(11) because the disclosure of the business name that included the words “Collection

Bureau” in the context of the entire message was sufficient to inform the call’s recipient that the caller

was a debt collector.

Third-Party Disclosure

Because the general court consensus is that meaningful disclosure and the mini-Miranda must be

provided in a voice mail communication, the main concern in leaving messages for the purpose of

attempting to collect a debt is the risk of a potential third-party disclosure. After all, how could a

collector comply with §§ 806(6) and 807(11) when leaving a voice mail without the added risk of third-

party disclosure? Collectors defending cases similar to Foti have advanced this argument, stating

providing the notice required under § 807(11) could result in a third-party disclosure, a violation of §

805(b) of the FDCPA, if the message was heard by someone other than the consumer.

One district court in California noted this argument may carry weight in some circumstances, but the

argument was not applicable in the instant case because the consumer lived alone.16 Similarly, a

Minnesota district court held such an argument was not applicable at the current stage in the proceedings

as the location where the messages were left was unknown.17 Yet another court declined to address the

third-party disclosure issue, but noted the risk of third-party disclosure is more remote when leaving

messages on the consumer’s phone than when a collector discloses information about a debt on the face

of an envelope or postcard.18 However, collectors should be aware the FDCPA does not protect

© 2011 ACA International. All Rights Reserved. Page 3 of 11

consumers from only deliberate or intentional disclosures to third parties; rather, it protects consumers

from inadvertent disclosures as well.19

Other courts have determined a violation of § 805(b) may occur when a message containing the mini-

Miranda disclosure is heard by a third party. In one case, the collector left a message for the consumer on

the consumer’s assistant’s voice mail which included the mini-Miranda disclosure.20 The court held the

voice message in question constituted a “communication” under the FDCPA to a third party that was “in

connection with the collection of any debt.”21 The court denied the collector’s motion for summary

judgment, holding the facts demonstrated the voice message violated § 805(b) of the FDCPA.22 With this

holding, the court demonstrated the risk of providing the § 807(11) disclosure when such messages are

heard by a third party.

A decision from the Southern District of Florida considered the potential contradiction between leaving

the mini-Miranda disclosure and preventing third-party disclosure under the FDCPA. In Berg v. Merchs.

Ass'n Collection Div., Inc.,23 the court denied the debt collector's motion to dismiss for failure to state a

claim, holding that providing the mini-Miranda disclosure in a voice message may violate the third-party

disclosure prohibitions of the FDCPA when the message is heard by a third party. In this case, the

collector left the consumer a voice message which contained the mini-Miranda disclosure. The consumer

subsequently brought suit against the collector for a violation of § 805(b) of the FDCPA.

The collector argued § 805(b) did not apply to a voice message left at the consumer's home because the

collector was not communicating with a third party and a forewarning was included in the message that

directed anyone other than the consumer to disconnect. The court disagreed, finding the warning

included in the message did not necessarily remove the message from the statutory restriction on third-

party communications.

The Berg court determined a collector may violate § 805(b) if he leaves a message for a consumer when

he is aware the message may be heard by others. The court noted the forewarning to disconnect could

perhaps dissuade other persons from listening to the message, but nothing in the message would alert the

consumer to disconnect if he were listening to it in the presence of others. The court also found "prior

consent of the consumer given directly to the debt collector" is not provided if a third party, or the

consumer in the presence of a third party, continued to listen to the message in spite of the warning.

Therefore, the court found the consumer stated a claim under § 805(b) and denied the collector's motion

to dismiss.

The court noted its ruling would make it difficult for a collector to comply with §§ 805(b), 806(6), and

807(11) when leaving a message on a consumer's voice mail. However, the court found no reason that a

collector is entitled to use voice messages, and noted a collector has other methods to reach consumers

including postal mail, in-person contact, and speaking directly via telephone.

Another court specifically rejected the collector’s third-party disclosure argument, asserting the only

reason the agency found itself in that predicament was because of the method it chose to use to collect

debts (i.e., leaving pre-recorded messages), not because of any contradictory provisions of the FDCPA.24

Similarly, an Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals case noted “the [FDCPA] does not guarantee a debt

collector the right to leave answering machine messages.”25

Messages with Live Third Parties

In a New York district court case, a consumer alleged a violation of § 806(6) when the debt collector

failed to disclose his identity when leaving a message with the consumer’s receptionist.26 The court

rejected this claim noting calls that reached the consumer’s receptionist would not require the disclosure

© 2011 ACA International. All Rights Reserved. Page 4 of 11

of the caller’s identity because that would require the debt collector to violate § 805(b), which prohibits

the disclosure of information concerning a debt to third parties.

In making its ruling, the court conceded other courts had ruled messages left on a consumer’s answering

machine at home would require the disclosure of the identity of the caller, but this was because the risk

of third-party disclosure in such situations was outweighed by the requirement to disclose the identity of

the caller. The court noted this situation was different because the calls were not placed to the

consumer’s home where the risk of a third-party disclosure was limited. Rather, the calls were placed to

the consumer’s receptionist, making the possibility of a third-party disclosure not a mere risk, but a

certainty.

Regarding the requirements of §§ 805(b) and 806(6), the court stated:

[Sections 805(b) and 806(6)] can be harmonized by (1) recognizing that the meaningful

disclosure requirements of [§ 806(6)] only apply when the telephone calls being placed are

made directly to the consumer or some other party with whom the consumer has consented to

allow the debt collector to communicate, and (2) that debt collectors, who, in attempting to

reach a [consumer], instead speak with a [consumer's] receptionist or some other third-party,

may not make a meaningful disclosure of identity to this third-party without running afoul of

the privacy-protective provisions of the FDCPA.

This case lends support for the position a message left when directly reaching a third party that does not

reveal the identity of the caller does not violate § 806(6), because a collector must instead comply with

the requirements of § 805(b).

Messages Attempting to Acquire Location Information

Other case law suggests messages that comply with § 804 of the Act and are left for the purpose of

obtaining or confirming location information may be exempt from the meaningful disclosure requirement

under § 806(6).27

In a Southern District of Florida case, the debt collector left messages with a non-consumer that did not

comply with the §§ 806(6) and 807(11) disclosure requirements. In the messages at issue, the caller

identified himself, explained he was looking for a specific consumer and requested a message be relayed

to the consumer.

The court found the individual had no standing to bring a claim under § 807(11) because the

requirements under § 807(11) only apply to consumers.28 The court noted, unlike § 807(11), § 806(6)

does not require the individual alleging a violation to be a consumer. Rather, the court found a non-

consumer can bring a claim under § 806(6) of the Act because § 806 refers to “any person” vs. a

consumer.29

However, this was not the end of the courts’ analysis of § 806(6). The court noted § 806(6) provides an

explicit exemption for calls that conform to the requirements of § 804, the section of the Act related to

the acquisition of location information.30 The court explained § 804 requires, in part, any debt collector

communicating with any person other than the consumer for the purpose of acquiring location

information about the consumer to identify himself, state he is confirming or correcting location

information concerning the consumer, and, only if expressly requested, identify his employer.31

The court found in the calls at issue, the caller identified himself and explained he was looking for a

specific consumer and requested a message be relayed to the consumer. The court found the content of

the messages complied with § 804 and the individual filing the suit did not allege he requested the

© 2011 ACA International. All Rights Reserved. Page 5 of 11

caller’s employer information nor did the messages disclose that a consumer owed a debt. Based on the

content of the messages, the court found the debt collector did not violate § 806(6) because the messages

fell under the exemption to § 806(6) for calls subject to § 804.32

Potential for Class Action Litigation

Third-party disclosure violations in the context of leaving messages are less likely to bring rise to class

action suits than messages which fail to leave the affirmative disclosures required under §§ 806(6) and

807(11).33 This is because a third-party disclosure only happens in the instance the message is actually

overheard by a third party, and therefore is unlikely to form the basis for class action liability.

Conversely, messages which fail to comply with §§ 806(6) and 807(11) potentially violate the Act in

every instance such a message is left, thus bringing about a greater chance for class action liability.

Request for Advisory Opinions

In 2005, ACA submitted a Petition for an FTC Advisory Opinion requesting clarification of two

provisions of the FDCPA: (1) under § 806(6), must a debt collector identify a corporate name in order to

meaningfully disclose the caller’s identity; and (2) when leaving a message for a consumer is the

collector required to provide the mini-Miranda disclosure under § 807(11).

The FTC denied ACA’s request, stating that because, at that time, a number of federal courts had ruled

consistently on the questions raised, the Commission would not grant the request to issue an advisory

opinion.

The letter from the FTC stated “[b]ased on these decisions, there is clear court precedent for the

proposition that a debt collector leaving a voice mail message must reveal the name of this employer,

even if the name indicates that the message involves a debt.”34

The FTC further concluded courts have addressed whether a debt collector must provide the mini-

Miranda disclosure when leaving messages for consumers, stating “[t]he decisions are uniform in

concluding that a collector failing to do so violates Section 807(11).”35

Although the letter failed to provide definitive clarification, it bolsters the viewpoint that to comply with

the FDCPA, a debt collector must state the name of her employer and provide the mini-Miranda when

leaving messages in accordance with §§ 806(6) and § 807(11) when attempting to collect a debt. The

letter did not address how a collector would comply with this requirement without simultaneously

violating § 805(b).

State Advisory Opinion

An ACA member filed a request for an advisory opinion in Maine with regards to Foti and similar

decisions. Maine’s Director of the Consumer Credit Regulation Office provided a written response on

June 20, 2006. The response stated, in pertinent part,

Although I share with others the concern about disclosing information to third parties, on

balance I believe that the importance of the "I am a debt collector" disclosure outweighs

those concerns. Keep in mind that a spouse is already considered the same as the

[consumer] in terms of [third] party communications… In addition, if a parent authorizes

others in a household to listen to telephone answering machine messages, that

authorization can be considered akin to permitting others to open and read one's mail.

Although this response is broad and may not account for all living situations, it may be inferred that the

state suggests the mini-Miranda should be provided in voice messages left for the consumer in an attempt

to collect a debt.

© 2011 ACA International. All Rights Reserved. Page 6 of 11

Refraining From Leaving a Message

Due to conflicting case law, some agencies are attempting to mitigate risk by ceasing to leave messages

on consumer’s answering machines. Refraining from leaving a message on a consumer’s answering

machine may be one of the best ways to mitigate risk, however a conflict exists regarding whether

hanging up without leaving a message on a consumer’s answering machine is considered a

communication under the FDCPA when the collector’s number shows up on a consumer’s caller ID.

One case held calling a consumer and hanging up without leaving a message is not a violation of the

FDCPA.36 In the case, the consumer alleged the debt collector violated the FDCPA by calling the

plaintiff repeatedly and hanging up without leaving a message on the consumer’s answering machine. 37

Although no message was left, the consumer was aware the debt collector was calling because the

collection agency’s number appeared on her caller ID.38

The court held the debt collector was not in violation of the FDCPA for failing to leave the consumer a

message.39 The court reasoned a number of courts have held a debt collector does not have a right to

leave a message, thus there can be no requirement that a message be left for a consumer.40 The court

further concluded the debt collector’s actions were not unfair or unconscionable because the consumer

intentionally refused to answer any calls from the debt collector and the debt collector simply chose not

to leave a message for the consumer.41

ACA’s Recommended Voice Mail Message

The analysis and holdings of these cases, combined with the lack of guidance provided by the FTC

regarding what should be disclosed in a voice mail message, presents a dilemma for the debt collection

industry.

The most prudent course of action for the collection industry would be to cease leaving messages for

consumers until full clarification is provided under law. A debt collector cannot be sued under any theory

if he does not communicate with the consumer. The next most prudent course of action is to leave

messages that provide both the mini-Miranda and meaningful disclosure, and include language to

simultaneously prevent the risk of a third-party disclosure.

For those who choose to continue leaving messages for consumers, ACA offers the following

recommended message. ACA does not warrant its legality or your liability should you choose to use it.

The proposed message is as follows:

This is a message for Mary Smith. If we have reached the wrong number for this person,

please call us at [phone #1] to remove your phone number. If you are not Mary Smith,

please hang up. If you are Mary Smith, please continue to listen to this message.

[PAUSE]

Ms. Smith, you should not listen to this message so that other people can hear it as it

contains personal and private information. [PAUSE]

This is Bob Jones from ABC Collection Agency. This is an attempt to collect a debt by a

debt collector. Any information obtained will be used for that purpose. Please contact me

about an important business matter at [phone #2].

Please note, the telephone number [phone #1] provided in the first paragraph of the sample message

should connect to a separate telephone number that goes straight to a voice mail. Such a telephone

number is issued for the purpose of allowing an individual that is not the consumer to remove his

© 2011 ACA International. All Rights Reserved. Page 7 of 11

telephone number from the collector’s records. The voice mail message should not disclose the existence

of a debt. A suggested message for this call-back number is:

If we have reached the wrong party, please leave us the phone number called and the

name left on the message. Please leave the date and time of the message and we will

update our records.

The telephone number [phone #2] provided in the last paragraph of the sample language should allow the

consumer to reach the debt collector placing the call.

The message provided above is merely the result of balancing risks and the limited options available to

debt collectors when leaving a message is imperative to successful collections. The message intends to

comply with the affirmative requirements of §§ 806(6) and 807(11), while providing language intended

to eliminate the possibility of third-party disclosure. Subsequent communications could use the same

language or omit the phrase “any information obtained will be used for that purpose.” In light of Berg,

language is included to decrease the risk of third-party disclosure, especially if someone other than the

consumer begins to listen to the message, and also if the consumer is listening to the message in the

presence of others.

Some collection agencies have raised concern that if they disclose the voice message is from a debt

collector, consumers will never return their phone calls. While this may prove to be true, many agencies

believe seasoned consumers already know when a voice mail message is from a debt collector even

without the disclosure statement. Providing additional detail about the purpose of the call may actually

encourage a consumer to call back. Only time will tell if the disclosure of a debt collector’s identity in a

phone message will impact the return call rate.

At this time, ACA does not have a fail-safe course of action for collectors. Please consult with

independent legal counsel as you decide whether, and if so, how you will adjust your operations

and compliance programs to comply with Foti and similar decisions. Policies and procedures

should be put into place to provide the reasoning why a debt collector elects to leave a message in a

particular way.

Establishing a Bona Fide Error Defense

Under § 813(c) of the FDCPA, a debt collector’s liability for an FDCPA violation can be absolved if, “it

shows by a preponderance of the evidence the violation was not intentional and resulted from a bona fide

error notwithstanding the maintenance of procedures reasonably adapted to avoid any such error.” 42 A

bona fide error defense is likely to be rejected if adequate procedures are not in place to safeguard

against FDCPA violations.

Due to the tension between providing meaningful disclosure and avoiding a third-party disclosure

violation, debt collectors who continue to leave messages may benefit from maintaining procedures that

delineate why a disclosure is given. The procedures put into place should establish a defense for third-

party disclosure. The following case law examines the issue of the bona fide error defense in the context

of leaving messages.

Two district court cases in the Eleventh Circuit essentially held the bona fide error defense was not

available for collectors who chose to omit the mini-Miranda disclosure in voice mail messages to

consumers. In both Valencia v. The Affiliated Group, Inc.43 and Edwards v. Niagara Credit Solutions,

Inc.,44 the consumer alleged the debt collectors violated the FDCPA by failing to include the mini-

Miranda in voice mail messages. In both cases the collectors asserted they were entitled to the bona fide

© 2011 ACA International. All Rights Reserved. Page 8 of 11

error defense because it was company policy for debt collectors to avoid identifying themselves because

the FDCPA prohibits third-party disclosure.

Both courts found the debt collectors did not adequately demonstrate their failure to make the required

disclosures was the result of a bona fide error. In particular, the debt collectors were required to show

they had procedures “reasonably adapted” to avoid the specific error at issue. The debt collectors’

procedures were adapted to protect against third-party disclosure under § 805(b) but did not address the

collectors’ failure to leave the required disclosures. The courts held the debt collector may not rely on

procedures meant to avoid violating one section of the FDCPA to shield it from liability for violating

other sections.

Importantly, the Edwards decision was recently affirmed by the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals. 45 The

court found debt collectors cannot assert the bona fide error defense when the debt collector intentionally

violates § 807(11) in every message it left in order to avoid the risk of violating § 805(b). The court also

held debt collectors must comply with the FDCPA’s disclosure requirements in voice mail messages

attempting to collect a debt from a consumer notwithstanding the Act’s prohibition on third-party

disclosure. As such, the court found the debt collector failed to meet the requirements of the bona fide

error defense.

However, in Niven v. Nat’l Action Fin. Servs., Inc.,46 the consumer demonstrated the debt collector

violated the FDCPA by including the mini-Miranda on a voice mail message left on the consumer’s

assistant’s voice mail. Despite the violation, the debt collector claimed it had procedures in place

reasonably adapted to prevent the violation. Specifically, the debt collector (1) had a policy of

prohibiting collectors from disclosing debts to third parties; (2) provided training to new hires including a

specific discussion of the prohibition; (3) had a collection manual that advised debt collectors to not state

a consumer owes a debt; (4) required new employees to sign a form acknowledging that they may only

leave a name and number in telephone messages; and (5) provided employees four compliance seminars

per year. The court found these procedures may be sufficient to avoid the error of disclosing a debt to a

third party. Accordingly, the consumer’s motion for summary judgment was denied.

Based on the holding in Niven, a bona fide error defense for third-party disclosure violations may be

easier to establish as the consumer would likely have to demonstrate the debt collector intended the

message to be heard by a third party. As at least one court has noted, “[t]he FDCPA was intended to

protect against deliberate disclosures to third parties as a method of embarrassing the consumer... not to

protect against the risk of an inadvertent disclosure that could occur if another person unintentionally

overheard the messages left on [the consumer’s] answering machine.”47

Therefore, to help avoid and thwart FDCPA lawsuits, debt collectors should have safeguarding

procedures in place, which are strictly followed, well documented, and regularly reviewed for reliability.

For more information on establishing a bona fide error defense, see ACA Fastfax #1129, Bona Fide

Error: Adequate Procedures.

Conclusion

Agencies subject to the FDCPA that leave a voice mail message when attempting to collect a debt must

include meaningful disclosure of the caller’s identity and state the call is from a debt collector to avoid

violating §§ 806(6) and 807(11) of the FDCPA. Procedures should be put in place to establish a bona fide

error defense for third-party disclosures, should such allegations arise. Any message provided should be

based on a risk analysis, and the ACA recommended voice mail message may aid members in

compliance.

© 2011 ACA International. All Rights Reserved. Page 9 of 11

ACA encourages its members to consult with independent legal counsel when determining whether to

continue to leave voice mail messages, and if so, what policies and procedures should be implemented to

ensure the member’s messages are in compliance with the FDCPA.

ACA International, P.O. Box 390106, Minneapolis, MN 55439-0106

Phone (952) 926-6547 Fax (952) 926-1624 E-mail compliance@acainternational.org

Web http://www.acainternational.org

© 2011 ACA International. All Rights Reserved.

This information is for the use of ACA International members only. Any distribution, reproduction, copying or sale

of this material or the contents hereof without consent is expressly prohibited.

This information is not to be construed as legal advice. Legal advice must be tailored to the specific circumstances

of each case. Every effort has been made to assure that this information is up-to-date as of the date of publication. It

is not intended to be a full and exhaustive explanation of the law in any area. This information is not intended as

legal advice and may not be used as legal advice. It should not be used to replace the advice of your own legal

counsel.

1

15 U.S.C. § 1692c(b) (2006) [§ 805(b)].

2

15 U.S.C. § 1692a(2) (2006) [§ 803(2)].

3

Foti v. NCO Fin. Sys., Inc., 424 F. Supp. 2d 643 (S.D.N.Y. 2006).

4

Id. at 669.

5

Inman v. NCO Fin. Sys., Inc., Civ. A. No. 08-5866, 2009 WL 3415281 (E.D. Pa. Oct. 21, 2009); Niven v. Nat’l

Action Fin. Servs., Inc., No. 8:07-CV-1326-T-27TBM, 2008 WL 4190961, *2 (M.D. Fla. Sept. 10, 2008); Ramirez

v. Apex Fin. Mgmt., LLC, 567 F. Supp. 2d 1035 (N.D. Ill. 2008); Baker v. Allstate Fin. Servs., Inc., 554 F. Supp. 2d

945, 952 (D. Minn. 2008); Edwards v. Niagara Credit Solutions, Inc., 586 F. Supp. 2d 1346, 1359 (N.D. Ga. Nov.

13, 2008); Costa v. Nat’l Action Fin. Servs., No. CIV. S-05-2084 FCD/KJM, 2007 WL 4526510 (E.D. Cal. Dec. 19,

2007); Masciarelli v. Richard J. Boudreau & Assocs., 529 F. Supp. 2d 183 (D. Mass. 2007).

6

Ostrander v. Accelerated Receivables, No. 07-CV-827C, 2009 WL 909646 (W.D.N.Y. Mar. 31, 2009);

Edwards v. Niagara Credit Solutions, Inc., 586 F. Supp. 2d 1346 (N.D. Ga. 2008); Valencia v. Affiliated Group, Inc,

No. 07-61381-CIV, 2008 WL 4372895 (S.D. Fla. Sept. 2008); Masciarelli v. Richard J. Boudreau & Assocs., 529 F.

Supp. 2d 183 (D. Mass. 2007); Costa v. Nat’l Action Fin. Servs., No. CIV. S-05-2084 FCD/KJM, 2007 WL

4526510 (E.D. Cal. Dec. 19, 2007); Leyes v. Corporate Collection Servs., Inc., No. 03 Civ. 8491(DAB), 2007 WL

1225547 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 18, 2006); Belin v. Litton Loan Servicing, LP, No. 8:06-cv-760-T-24 EAJ, 2006 WL

1992410 (M.D. Fla. July 14, 2006). See also Joseph v. J.J. MacIntyre Cos., L.L.C., 281 F. Supp. 2d 1156 (N.D. Cal.

2003); Hosseinzadeh v. M.R.S. Assocs., Inc., 387 F. Supp. 2d 1104 (C.D. Cal. 2005).

7

15 U.S.C. § 1692d(6) (2006) [§ 806(6)]. See also Mark v. J.C. Christensen & Assocs., Inc., Civ. No. 09-100

ADM/SRN, 2009 WL 2407700, at *2 (D. Minn. Aug. 4, 2009); Leyse v. Corporate Collection Servs., Inc., No. 03

Civ. 8491, 2006 WL 2708451, at *4 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 18, 2006); Muir v. Navy Fed. Credit Union, 529 F. 3d 1100,

1106 (D.C. Cir. 2008).

8

Biggs v. Credit Collections, Inc., No. CIV-07-0053-F, 2007 WL 4034997, at *4 (W.D. Okla. Nov. 15, 2007).

9

Ramirez v. Apex Fin. Mgmt., LLC, 567 F. Supp. 2d 1035, 1041-42 (N.D. Ill. 2008).

10

Reed v. Global Acceptance Credit Co., No. C-08-01826 RMW, 2008 WL 3330165 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 12, 2008).

11

Id. (citing Pressley v. Capital Credit & Collection Serv., 760 F.2d 922, 925 (9th Cir. 1985)).

12

Chalik v. Westport Recovery Corp., No. 09-60819-CIV, 2009 WL 5191422 (S.D. Fla. Oct. 30, 2009).

13

Id. at *4.

14

Id.

15

Beeders v. Gulf Coast Collection Bureau, Inc., No. 8:89-CV-00458-T-AEP, (MD Fla. Jan. 12, 1011).

16

Costa v. Nat’l Action Fin. Servs., No. CIV. S-05-2084 FCD/KJM, 2007 WL 4526510 (E.D. Cal. Dec. 19, 2007).

17

Baker v. Allstate Fin. Servs., Inc., No. 07-cv-2579 (JNE/JJG), 2008 WL 2042622 (D. Minn. May 3, 2008).

18

Joseph v. J.J. MacIntyre Cos., L.L.C., 281 F. Supp. 2d 1156 (N.D. Cal. 2003).

19

Zortman v. J.C. Christensen & Assoc., Inc., No. 10-3086 (JNE/FLN), 2011 WL 1576475 (D. Minn. Apr. 26,

2011).

© 2011 ACA International. All Rights Reserved. Page 10 of 11

20

Niven v. Nat’l Action Fin. Servs., Inc., No. 8:07-CV-1326-T-27TBM, 2008 WL 4190961, *1 (M.D. Fla. Sept. 10,

2008).

21

Id. at *2.

22

Id.

23

Berg v. Merchs. Ass'n Collection Div., Inc., No. 08-60660-CIV-DIMITROULEAS (S.D. Fla. Oct. 31, 2008).

24

Leyes v. Corporate Collection Servs., Inc., No. 03 Civ. 8491(DAB), 2007 WL 1225547 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 18,

2006).

25

Edwards v. Niagara Credit Solutions, Inc., 584 F.3d 1350, 1353 (11th Cir. 2009).

26

Fashakin v. Nextel Commc’n, No. 05-CV-3080 (RRM), 2009 WL 790350 (E.D.N.Y. Mar. 25, 2009).

27

Sclafani v. BC Servs., Inc., No. 10-61360-CIV, 2010 WL 4116471, at *4 (S.D. Fla. Oct. 18, 2010). See also 15

U.S.C. § 1692b (2006) [§ 804].

28

Sclafani v. BC Servs., Inc., No. 10-61360-CIV, 2010 WL 4116471, at *2 (S.D. Fla. Oct. 18, 2010).

29

Sclafani v. BC Servs., Inc., No. 10-61360-CIV, 2010 WL 4116471, at *3 (S.D. Fla. Oct. 18, 2010).

30

Sclafani v. BC Servs., Inc., No. 10-61360-CIV, 2010 WL 4116471, at *4 (S.D. Fla. Oct. 18, 2010).

31

Sclafani v. BC Servs., Inc., No. 10-61360-CIV, 2010 WL 4116471, at *4 (S.D. Fla. Oct. 18, 2010).

32

Sclafani v. BC Servs., Inc., No. 10-61360-CIV, 2010 WL 4116471, at *4 (S.D. Fla. Oct. 18, 2010).

33

Drossin v. Nat’l Action Fin. Serv., Inc., 255 F.R.D. 608, 618 (S.D. Fla. 2009).

34

Hosseinzadeh v. M.R.S. Assocs., Inc., 387 F. Supp. 2d 1104 (C.D. Cal. 2005); Joseph v. J.J. MacIntyre Cos.,

L.L.C., 281 F. Supp. 2d 1156 (N.D. Cal. 2003); and Wright v. Credit Bureau of Georgia, Inc., 548 F. Supp. 591, on

consideration on other grounds, 555 F. Supp. 1005 (N.D. Ga. 1982).

35

Foti v. NCO Fin. Sys., Inc., 424 F. Supp. 2d 643 (S.D.N.Y. 2006); Hosseinzadeh v. M.R.S. Assocs., Inc., 387 F.

Supp. 2d 1104 (C.D. Cal. 2005). See also Chlanda v. Wymard, 1995 U.S. Dist. Lexis 14394,*32 n.16 (S.D. Ohio

1995) (voice mail message requesting that the consumer pay a credit card debt violated § 807(11) because it did not

include that provision’s notice).

36

Carman v. CBE Grp., Inc., No. 09-2538-JAR, 2011 WL 1102842 (D. Kan. Mar. 23, 2011).

37

Id. at * 3.

38

Id. at * 4.

39

Id. at * 7.

40

Id. at * 7.

41

Id. at * 8.

42

15 U.S.C. § 1692k(c) (2006) [§ 813(c)].

43

Valencia v. The Affiliated Group, Inc., No. 07-61381-CIV, 2008 WL 4372895 (S.D. Fla. Sept. 24, 2008).

44

Edwards v. Niagara Credit Solutions, Inc., 586 F. Supp. 2d 1346 (N.D. Ga. Nov. 13, 2008) aff’d by Edwards v.

Niagara Credit Solutions, Inc., 584 F.3d 1350, 1353 (11th Cir. 2009).

45

Edwards v. Niagara Credit Solutions, Inc., 584 F.3d 1350, 1353 (11th Cir. 2009).

46

Niven v. Nat’l Action Fin. Servs., Inc., No. 8:07-cv-1326-T-27TBM, 2008 WL 4190961 (M.D. Fla. Sept. 10,

2008).

47

Mark v. J.C. Christensen & Assocs., Inc., Civ. No. 09-100 ADM/SRN, 2009 WL 2407700, at *5 (D. Minn. Aug.

4, 2009).

© 2011 ACA International. All Rights Reserved. Page 11 of 11

You might also like

- How to Get Rid of Your Unwanted Debt: A Litigation Attorney Representing Homeowners, Credit Card Holders & OthersFrom EverandHow to Get Rid of Your Unwanted Debt: A Litigation Attorney Representing Homeowners, Credit Card Holders & OthersRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Defense of Collection Cases Edelman, (2007)Document43 pagesDefense of Collection Cases Edelman, (2007)Jillian Sheridan100% (2)

- Debt CollectorsDocument6 pagesDebt CollectorsGinger Unwilling100% (1)

- Fair Debt Collection ICLEDocument24 pagesFair Debt Collection ICLEPWOODSLAWNo ratings yet

- The Role of Validation and Communication in The Debt Collection Process Elwin GriffithDocument43 pagesThe Role of Validation and Communication in The Debt Collection Process Elwin GriffithJillian Sheridan100% (3)

- Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (ELI Highlights)Document27 pagesFair Debt Collection Practices Act (ELI Highlights)ExtortionLetterInfo.com60% (5)

- Appendices To Substantive Defenses To Consumer Debt Collection Suits TDocument59 pagesAppendices To Substantive Defenses To Consumer Debt Collection Suits Tdbush2778No ratings yet

- Tender of Payment LawDocument23 pagesTender of Payment Lawmo100% (4)

- DEFENSE OF COLLECTION CASES: ENSURING PROPER PLAINTIFF AND COMPLIANCEDocument40 pagesDEFENSE OF COLLECTION CASES: ENSURING PROPER PLAINTIFF AND COMPLIANCEjsquitieri100% (1)

- NCLC Digital Library - Eleventh Circuit Issues Must-Read FCRA DecisionDocument4 pagesNCLC Digital Library - Eleventh Circuit Issues Must-Read FCRA DecisionCK in DCNo ratings yet

- Collection Defense Feb 2010Document67 pagesCollection Defense Feb 2010Brad Warner100% (1)

- Cases - FDCPA Dan BenhamDocument4 pagesCases - FDCPA Dan BenhamTitle IV-D Man with a plan50% (2)

- Fair Debt Collection Practices ActDocument14 pagesFair Debt Collection Practices ActEzekiel Kobina100% (1)

- Demolition Agenda: How Trump Tried to Dismantle American Government, and What Biden Needs to Do to Save ItFrom EverandDemolition Agenda: How Trump Tried to Dismantle American Government, and What Biden Needs to Do to Save ItNo ratings yet

- Letter From FTC Regarding Validation of DebtDocument1 pageLetter From FTC Regarding Validation of DebtwicholacayoNo ratings yet

- TaxonomyDocument56 pagesTaxonomyKrezia Mae SolomonNo ratings yet

- Motion to Dismiss OppositionDocument17 pagesMotion to Dismiss OppositionTaipan KinlockNo ratings yet

- Appendices To Substantive Defenses To Consumer Debt Collection Suits TDocument59 pagesAppendices To Substantive Defenses To Consumer Debt Collection Suits TCairo Anubiss100% (2)

- Avoiding Workplace Discrimination: A Guide for Employers and EmployeesFrom EverandAvoiding Workplace Discrimination: A Guide for Employers and EmployeesNo ratings yet

- The 10 Most Inspiring Quotes of Charles F HaanelDocument21 pagesThe 10 Most Inspiring Quotes of Charles F HaanelKallisti Publishing Inc - "The Books You Need to Succeed"100% (2)

- Inventory Valiuation Raw QueryDocument4 pagesInventory Valiuation Raw Querysatyanarayana NVSNo ratings yet

- Black Veil BridesDocument2 pagesBlack Veil BridesElyza MiradonaNo ratings yet

- Chas Beaman v. Mountain America Federal Credit UnionDocument16 pagesChas Beaman v. Mountain America Federal Credit UnionAnonymous WCaY6r100% (1)

- PRM Vol1 SystemsDocument1,050 pagesPRM Vol1 SystemsPepe BondiaNo ratings yet

- Kontodiakos V Experian Information Solutions Vaedce-23-00459 0001.0Document21 pagesKontodiakos V Experian Information Solutions Vaedce-23-00459 0001.0Sam OrlandoNo ratings yet

- Training Report PRASADDocument32 pagesTraining Report PRASADshekharazad_suman85% (13)

- Aimt ProspectusDocument40 pagesAimt ProspectusdustydiamondNo ratings yet

- Credit Collection CMP TDocument13 pagesCredit Collection CMP TEmpresarioNo ratings yet

- Fellig Reizes Stellar Recovery Inc Class Action Complaint FDCPA TCPADocument19 pagesFellig Reizes Stellar Recovery Inc Class Action Complaint FDCPA TCPAghostgripNo ratings yet

- Trans Union LLC v. Federal Trade Commission, 536 U.S. 915 (2002)Document3 pagesTrans Union LLC v. Federal Trade Commission, 536 U.S. 915 (2002)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 5Document46 pagesJurnal 5Firman HidayatullahNo ratings yet

- HNKCMPTDocument11 pagesHNKCMPTBennet KelleyNo ratings yet

- Banking FinalDocument6 pagesBanking FinalAtwooki RogersNo ratings yet

- Encarnacion V FCOADocument11 pagesEncarnacion V FCOAcloudedtitlesNo ratings yet

- Kim V A Place For Mom ComplaintDocument18 pagesKim V A Place For Mom ComplaintseniorhousingforumNo ratings yet

- Federal Communications Commission DA 12-154Document9 pagesFederal Communications Commission DA 12-154Mark ReinhardtNo ratings yet

- Lorna A. Matthiesen, An Individual v. Banc One Mortgage Corporation, A Delaware Corporation, 173 F.3d 1242, 10th Cir. (1999)Document8 pagesLorna A. Matthiesen, An Individual v. Banc One Mortgage Corporation, A Delaware Corporation, 173 F.3d 1242, 10th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Papa Murphy's Text Spam LawsuitDocument11 pagesPapa Murphy's Text Spam Lawsuitronjackson445No ratings yet

- Inviertal Financial Managers, S.A. v. Bank of America, N.A., 11th Cir. (2015)Document9 pagesInviertal Financial Managers, S.A. v. Bank of America, N.A., 11th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Final Signed Comments To FCCDocument33 pagesFinal Signed Comments To FCCrobertharding22No ratings yet

- DoddFrankNews NOV2015Document11 pagesDoddFrankNews NOV2015WARWICKJNo ratings yet

- Joseph L. Portwood and Betty Portwood, Individuals, Trading and Doing Business As The Portwood Company v. The Federal Trade Commission, 418 F.2d 419, 10th Cir. (1969)Document8 pagesJoseph L. Portwood and Betty Portwood, Individuals, Trading and Doing Business As The Portwood Company v. The Federal Trade Commission, 418 F.2d 419, 10th Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument20 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Opinion Upholding Your Right Sue CreditorsDocument6 pagesOpinion Upholding Your Right Sue CreditorsThomas LoughlinNo ratings yet

- Lee Donaldson v. Informatica Corporation, 3rd Cir. (2011)Document7 pagesLee Donaldson v. Informatica Corporation, 3rd Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- PR Telephone Company v. Advanced Cellular, 483 F.3d 7, 1st Cir. (2007)Document7 pagesPR Telephone Company v. Advanced Cellular, 483 F.3d 7, 1st Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- CFPB Compliance Bulletin 2017-01 Date: SubjectDocument6 pagesCFPB Compliance Bulletin 2017-01 Date: SubjectIBG FinanceNo ratings yet

- Match - ComplaintDocument26 pagesMatch - ComplaintTechCrunchNo ratings yet

- Class Action ComplaintDocument18 pagesClass Action ComplaintSamuel RichardsonNo ratings yet

- Everett Houck v. Local Federal Savings and Loan, Inc., A Corporation, 996 F.2d 311, 10th Cir. (1993)Document7 pagesEverett Houck v. Local Federal Savings and Loan, Inc., A Corporation, 996 F.2d 311, 10th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NOT PrecedentialDocument20 pagesNOT PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- CMJ/CU Et Al Cramming CommentsDocument6 pagesCMJ/CU Et Al Cramming CommentsMAG-NetNo ratings yet

- 120510advisoryopinionholderrule PDFDocument5 pages120510advisoryopinionholderrule PDFMark ReinhardtNo ratings yet

- Elizabeth Brown, On Behalf of Herself and All Others Similarly Situated, Formerly Known As Elizabeth Schenck v. Card Service Center Cardholder Management Services, 464 F.3d 450, 3rd Cir. (2006)Document8 pagesElizabeth Brown, On Behalf of Herself and All Others Similarly Situated, Formerly Known As Elizabeth Schenck v. Card Service Center Cardholder Management Services, 464 F.3d 450, 3rd Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Federal Agency Lawsuit Against Fifth Third Bank: "By any standard of decency, Fifth Third’s conduct is unconscionable. By statute, it is abusive."Document10 pagesFederal Agency Lawsuit Against Fifth Third Bank: "By any standard of decency, Fifth Third’s conduct is unconscionable. By statute, it is abusive."Herman Legal Group, LLCNo ratings yet

- Polotan vs. CADocument5 pagesPolotan vs. CAKatrina Quinto PetilNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument13 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Martin V Cellco Partnership TCPA FDCPA Complaint IllinoisDocument30 pagesMartin V Cellco Partnership TCPA FDCPA Complaint IllinoisghostgripNo ratings yet

- Commentary: New Class Actions Targeting Atm Operators Alleging Failure To Comply With Atm Notice RequirementsDocument4 pagesCommentary: New Class Actions Targeting Atm Operators Alleging Failure To Comply With Atm Notice RequirementsmscnqphongNo ratings yet

- Rent Bro CMP TDocument8 pagesRent Bro CMP TBennet KelleyNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument7 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Lund V Diversified Adjustment Service, Inc. (DAS) FDCPA ComplaintDocument5 pagesLund V Diversified Adjustment Service, Inc. (DAS) FDCPA ComplaintghostgripNo ratings yet

- Illinois Ex Rel. Madigan, Attorney General of Illinois v. Telemarketing Associates, Inc., 538 U.S. 600 (2003)Document21 pagesIllinois Ex Rel. Madigan, Attorney General of Illinois v. Telemarketing Associates, Inc., 538 U.S. 600 (2003)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Tender of Payment Under UCC Section 3-604: A Forgotten DefenseDocument22 pagesTender of Payment Under UCC Section 3-604: A Forgotten DefenseLyka TejadaNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument14 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 9519 TCPA ACT - Pre Recorded MessagesDocument5 pages9519 TCPA ACT - Pre Recorded MessagesDeyvered MTNo ratings yet

- StampDocument1 pageStampDeyvered MTNo ratings yet

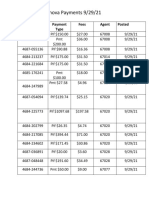

- MasterAttendance9 29Document6 pagesMasterAttendance9 29Deyvered MTNo ratings yet

- InovaPmts10 11 21Document5 pagesInovaPmts10 11 21Deyvered MTNo ratings yet

- Inova PD Pmts 2Document9 pagesInova PD Pmts 2Deyvered MTNo ratings yet

- Weekly October Bonus Report: Jairo Mendez - 67013 Jose Ledezma - 67014Document6 pagesWeekly October Bonus Report: Jairo Mendez - 67013 Jose Ledezma - 67014Deyvered MTNo ratings yet

- InvPmts9 29 21Document2 pagesInvPmts9 29 21Deyvered MTNo ratings yet

- Current Roster November 2021Document1 pageCurrent Roster November 2021Deyvered MTNo ratings yet

- Avi 10-0221 Bonus ProgramDocument1 pageAvi 10-0221 Bonus ProgramDeyvered MTNo ratings yet

- Invoice Recrutier PDFDocument2 pagesInvoice Recrutier PDFDeyvered MTNo ratings yet

- IBM Trusteer Rapport protection for Citibanamex customersDocument2 pagesIBM Trusteer Rapport protection for Citibanamex customersDeyvered MTNo ratings yet

- Inv Pmts 92821Document2 pagesInv Pmts 92821Deyvered MTNo ratings yet

- AVIAGENTROSTER110821Document1 pageAVIAGENTROSTER110821Deyvered MTNo ratings yet

- Ultra Structure of Plant Cell 1Document18 pagesUltra Structure of Plant Cell 1Kumaran JothiramNo ratings yet

- "Network Security": Alagappa UniversityDocument1 page"Network Security": Alagappa UniversityPRADEEPRAJANo ratings yet

- Far Eastern University Institute of Tourism and Hotel Management Tourism Management Program 1 Semester A.Y. 2019 - 2020Document46 pagesFar Eastern University Institute of Tourism and Hotel Management Tourism Management Program 1 Semester A.Y. 2019 - 2020Mico BolorNo ratings yet

- All About Bearing and Lubrication A Complete GuideDocument20 pagesAll About Bearing and Lubrication A Complete GuideJitu JenaNo ratings yet

- NJMC Lca FinalDocument47 pagesNJMC Lca Finalr_gelpiNo ratings yet

- (Drago) That Time I Got Reincarnated As A Slime Vol 06 (Sub Indo)Document408 pages(Drago) That Time I Got Reincarnated As A Slime Vol 06 (Sub Indo)PeppermintNo ratings yet

- Stockholm Acc A300 600 2278Document164 pagesStockholm Acc A300 600 2278tugayyoungNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Security Product Roadmap Brief All Invitations-2023 AprilDocument5 pagesMicrosoft Security Product Roadmap Brief All Invitations-2023 Apriltsai wen yenNo ratings yet

- Q3 SolutionDocument5 pagesQ3 SolutionShaina0% (1)

- Gorsey Bank Primary School: Mission Statement Mission StatementDocument17 pagesGorsey Bank Primary School: Mission Statement Mission StatementCreative BlogsNo ratings yet

- PHP Oop: Object Oriented ProgrammingDocument21 pagesPHP Oop: Object Oriented ProgrammingSeptia ni Dwi Rahma PutriNo ratings yet

- Sublime Union: A Womans Sexual Odyssey Guided by Mary Magdalene (Book Two of The Magdalene Teachings) Download Free BookDocument4 pagesSublime Union: A Womans Sexual Odyssey Guided by Mary Magdalene (Book Two of The Magdalene Teachings) Download Free Bookflavia cascarinoNo ratings yet

- Hierarchical Afaan Oromoo News Text ClassificationDocument11 pagesHierarchical Afaan Oromoo News Text ClassificationendaleNo ratings yet

- FND Global and FND Profile PDFDocument4 pagesFND Global and FND Profile PDFSaquib.MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Viennot - 1979 - Spontaneous Reasoning in Elementary DynamicsDocument18 pagesViennot - 1979 - Spontaneous Reasoning in Elementary Dynamicsjumonteiro2000No ratings yet

- 2020-Effect of Biopolymers On Permeability of Sand-Bentonite MixturesDocument10 pages2020-Effect of Biopolymers On Permeability of Sand-Bentonite MixturesSaswati DattaNo ratings yet

- Super BufferDocument41 pagesSuper Bufferurallalone100% (1)

- Detailed Lesson Plan in TechnologyDocument11 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in TechnologyReshiela OrtizNo ratings yet

- UK Journal Compares Clove & Rosemary Oil Antibacterial ActivityDocument5 pagesUK Journal Compares Clove & Rosemary Oil Antibacterial ActivityNurul Izzah Wahidul AzamNo ratings yet

- LQRDocument34 pagesLQRkemoNo ratings yet

- Aptamers in HIV Research Diagnosis and TherapyDocument11 pagesAptamers in HIV Research Diagnosis and TherapymikiNo ratings yet

- Green Tree PythonDocument1 pageGreen Tree Pythonapi-379174072No ratings yet

- Hercules Segers - Painter EtchterDocument4 pagesHercules Segers - Painter EtchterArtdataNo ratings yet