Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Consonant Clusters in Chinese

Uploaded by

Tom TraddlesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Consonant Clusters in Chinese

Uploaded by

Tom TraddlesCopyright:

Available Formats

Encyclopedia of Chinese Language and Linguistics

Volume 1

A–Dǎi

For use by the Author only | © 2017 Koninklijke Brill NV

General Editor

Rint Sybesma

(Leiden University)

Associate Editors

Wolfgang Behr

(University of Zurich)

Yueguo Gu

(Chinese Academy of Social Sciences)

Zev Handel

(University of Washington)

C.-T. James Huang

(Harvard University)

James Myers

(National Chung Cheng University)

For use by the Author only | © 2017 Koninklijke Brill NV

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF

CHINESE LANGUAGE

AND LINGUISTICS

Volume 1

A–Dǎi

General Editor

Rint Sybesma

Associate Editors

Wolfgang Behr

Yueguo Gu

Zev Handel

C.-T. James Huang

James Myers

LEIDEN • BOSTON

2017

For use by the Author only | © 2017 Koninklijke Brill NV

Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface.

ISBN 978-90-04-18643-9 (hardback, set)

ISBN 978-90-04-26227-0 (hardback, vol. 1)

ISBN 978-90-04-26223-2 (hardback, vol. 2)

ISBN 978-90-04-26224-9 (hardback, vol. 3)

ISBN 978-90-04-26225-6 (hardback, vol. 4)

ISBN 978-90-04-26226-3 (hardback, vol. 5)

Copyright 2017 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhofff, Global Oriental and Hotei Publishing.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or

otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for

internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid

directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA.

Fees are subject to change.

This book is printed on acid-free paper and produced in a sustainable manner.

For use by the Author only | © 2017 Koninklijke Brill NV

665 Consonant Clusters

Harbsmeier, Christoph, Aspects of Classical Chinese (OC). The debate about their existence and

Syntax, London: Curzon Press, 1981. inventory runs through the modern history of

Haspelmath, Martin and Ekkehard König, “Conces-

sive Conditionals in the Languages of Europe”, in:

Chinese historical phonology and remains the

Johan van der Auwera and Dónall P. Ó Baoill, eds., most thorny and interesting aspect of the fijield.

Adverbial Constructions in the Languages of Europe, In recent reconstruction systems of OC, rhymes

Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1998, 563–640. (=rimes) are mostly identical (given notational

Jacques, Guillaume, “The Character 維·惟·唯 ywij and

diffferences), while initials difffer in a wide vari-

the Reconstruction of the 脂 Zhi and 微 Wei Series”,

Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale 29/2, 2000, ety of ways, between clusters and singletons

205–222. and especially between diffferent cluster types

König, Ekkehard, “Concessive Connectives and Con- (see Table 1). A reliable reconstruction of OC is

cessive Sentences. Crosslinguistic Regularities and immensely valuable in diffferent fijields of study,

Pragmatic Principles”, in: J. Hawkins, ed., Explain-

ing Language Universals, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, from ancient Chinese textual interpretation to

1988, 145–166. the identifijication of Eurasian proper names in

König, Ekkehard, “Concessive Clauses”, in: R.E. Asher, Chinese-language historical sources, let alone for

ed., The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, an understanding of the history of the Chinese

Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1994, 679–681.

Legge, James, The Ch’un Ts’ew with the Tso Chuen, language and for the reconstruction of Proto-

vol. V of The Chinese Classics, Taipei: SMC Publish- Sino-Tibetan and other language families. Yet

ing, 2000. largely because of uncertainty about the nature

Lǐ Mèngshēng 李梦生, Zuǒzhuàn yì zhù 左传译注 of consonant clusters, OC reconstructions are

[Zuǒzhuàn with translation and commentary],

Shànghǎi 上海: Shànghǎi gǔjí 上海古籍出版社, not yet reliable enough to serve these purposes.

1998. Reconstructions of → Middle Chinese (MC)

Lǐ Yàn 李艳, “Shǐjì liáncí xìtǒng yánjiū 史记连词系统 have no consonant clusters, nor do most con-

研究” [Study on the system of conjunctions in the temporary Chinese dialects (→ Syllable Struc-

Shǐjì], dissertation, Jílín dàxué 吉林大学, 2012.

Pulleyblank, Edwin G., Outline of Classical Chinese

ture). Exceptions are always shown to be

Grammar, Vancouver: UBC Press, 1995. secondary: Píngdìng 平定 (a → Jìn 晋 dialect, Xú

Wèi Hǎiyàn 魏海艳, “Jīnwén Shàngshū fùjù yánjiū 今 1981; Wáng Hóngjūn 1994) /˓tsɭɤŋ/ ‘today’ comes

文尚书复句研究” [Study on complex sentences in from rhotacization (→ érhuà 兒化) (cognate to

the new text version of the Book of Documents], MA

Běijīng Mandarin jīnr 今兒); for Qīngyī Miáo 青

thesis, Yángzhōu dàxué 扬州大学, 2010.

Yáng Bójùn 杨伯峻 and Hé Lèshì 何乐士, Gǔ Hànyǔ 衣苗 Chinese (a → Xiāng 湘 dialect, Lǐ Lán 2004),

yǔfǎ jí qí fāzhǎn 古汉语语法及其发展 [Ancient /ʿklu/ ‘early’ in the Fúróng 芙蓉 variety corre-

Chinese grammar and its development], revised sponds to afffricate /ʿtlu/, /ʿtsu/ in other varieties

edition, Běijīng 北京: Yǔwén 语文出版社, 2001. (cognate to Standard Mandarin zǎo 早). In con-

Zhāng Yùjīn 张玉金, Chūtǔ Zhànguó wénxiàn xūcí

yánjiū 出土战国文献虚词研究 [Survey of function trast, other Sino-Tibetan languages often show a

words in Warring States excavated texts], Běijīng richer syllable structure, like Khroskyabs (rGyal-

北京: Rénmín 人民出版社, 2011. rongic) /ʁɴzbrɑ˥˥/ ‘dare’ or Classical Tibetan

Zhōu Huìjuān 周会娟, “Hánfēizǐ yǒubiāo fùjù yánjiū bsgrigs ‘arrange, fijix (past stem)’. Although Proto-

韩非子有标复句研究” [Study on marked complex

sentences in Hánfēizǐ], Xīnjiāng dàxué 新疆大学, Sino-Tibetan is yet to be reconstructed in detail,

2009. it clearly had consonant clusters like *sn-: Zbu

Rgyalrong (→ rGyalrongic) /kə-snɑz˥˨/ ‘seven’

Lukáš Zádrapa corresponds to Burmese khu.n̥ ac and Kinnauri

(Bodic) /stiʃ/; Zbu Rgyalrong /tə-sɲəv˥˨/ ‘nasal

mucus’ to Burmese n̥ ap, Kinnauri /stəmti/ and

Consonant Clusters Tibetan snabs. As the Sino-Tibetan origin of Chi-

nese is hardly in doubt (→ Genetic Position of

1. Int roduct io n Chinese), some linguistic system ancestral to

MC must have once had consonant clusters.

Consonant clusters like *pr-, *sn- and *-ks are However, some scholars reconstruct consonant

postulated by various scholars for → Old Chinese clusters within OC, while others consider that

For use by the Author only | © 2017 Koninklijke Brill NV

Consonant Clusters 666

the syllable structure of OC had already been a phono-semantic compound, with lí 貍 *liIII

reduced to something essentially identical to ‘a kind of wild cat’ functioning as a phonetic ele-

that of modern Chinese. ment. To a speaker of Middle or later Chinese, it

Influential recent systems of reconstructed is hard to understand how *liIII could indicate

OC include those of → Li Fang-kuei (1971, 1976) the pronunciation of *mɛjII.

later revised by Gong (1990, 1993, 1994, 2005), We can conjecture that the two words had

→ Wáng Lì (1958, 1987) later revised by Guō more similar pronunciations during the forma-

(2010), → Starostin (1989), Zhèngzhāng (2003, tive centuries of the Chinese script. This does

2013), and Pān (2000), Baxter (1992), Schuessler seem to be the case for the vowels: both words

(2009), and Baxter and Sagart (2014). All contain are attested in the Book of Odes, where they

consonant clusters, except Wáng Lì’s system, transitively rhyme with each other. This reflects

which remains to this day the version taught to a general principle formulated by Duàn Yùcái

mainland Chinese undergraduates. 段玉裁, in his Liùshū Yīnjūnbiǎo 六書音均表

In this article, we will mostly use the Baxter- (1776), as tóngshēng bì tóngbù 同聲必同部 ‘char-

Sagart system to illustrate recent OC reconstruc- acters sharing a phonetic element must be in the

tions. Chinese words are transcribed in MC, with same (OC) rhyming category’. Modern recon-

added asterisks, using Baxter’s MC transcription, structions of OC have *-ə for both words.

which we adapt into IPA and annotate with As for the initials, we could propose MC *m-

MC division (→ děng 等) numbers (see below) in mái 霾 as originating in a consonant cluster

in roman-numeral subscript to facilitate discus- *ml- that later simplifijied to *m-. A character like

sion. The presence of these subscript numbers lí 貍 pronounced OC *lə would be judged good

enables MC reconstructed forms to be readily enough by literate speakers of OC as phonetic

distinguished from OC reconstructed forms. element to write *mlə. We have now a hypoth-

esis where an OC initial cluster *ml- explains a

2. Fin al Clust e rs i n Ol d C h i nese graphic connection between MC *m- and *l-, a

connection seen also in other sets of words writ-

We briefly discuss fijinal clusters before confijin- ten with the same phonetic element; such sets

ing the scope of the remainder of this article are called → xiéshēng 諧聲 series. (See Table 1

to initial clusters. Following a hypothesis fijirst for diffferent modern reconstructions for mái 霾).

propounded by → André-Georges Haudricourt This line of thinking underlies early hypoth-

(1954a, 1954b), it is generally accepted that MC eses that postulate initial consonant clusters in

tonal distinctions come from lost codas: shǎng OC, starting with Gabelentz (1881), who conjec-

上 (*-X) < *-ʔ, qù 去 (*-H) < *-s (→ Tonogen- tured a *kl- to explain the particularly common

esis). This hypothesis entails OC *-Nʔ and *-Ns MC *k-/*l- connection. Maspero (1920) and Karl-

for syllables with a nasal coda in MC. Scholars gren (1923) in Europe, as well as Lín (1924) and

also reconstruct *-ks, *-(N)ʔs > *-H; *-ps, *-ts > Chén (1937) in China all argued for initial clus-

*-jH to explain, among other things, derived qù- ters in OC to account for a range of phenomena

toned forms, reconstructed with an OC sufffijix *-s centered on xiéshēng connections.

with several functions: wù 惡 *uHI < *ʔˤas < OC The most influential among early proponents

*ʔˤak-s ‘hate (v.)’, cf. è 惡 *akI < OC *ʔˤak ‘bad’; of OC initial clusters was → Bernhard Karlgren,

nèi 內 *nwʌjHI < *nˤuts < OC *nˤ[u]p-s ‘inside’, who, in his later works, notably Grammata Serica

cf. nà 內 (later 納) *nʌpI < OC *nˤ[u]p ‘bring in’. Recensa (1957), reconstructed 19 initial clusters

like *kl-, *xm-, *sn-, and *kʰs-, corresponding to

3. Re const ruct ing I ni ti a l C l u ster s various xiéshēng connection patterns. Karlgren’s

Us ing xié sh ē n g approach, probably influenced by Maspero

(1920, 1930), can be termed “consonant stacking”:

Consider the character mái 霾 *mɛjII ‘dust he reconstructed OC *AB- for a xiéshēng connec-

storm’. In → Shuōwén jiězì 說文解字, a 2nd- tion between MC onsets *A- and *B-. A xiéshēng

century character dictionary, it is analyzed as connection is explained as either (1) OC *AB- >

For use by the Author only | © 2017 Koninklijke Brill NV

667 Consonant Clusters

MC *A-, OC *B- > MC *B-, or (2) OC *AB- > MC OC clusters was made by Yakhontov (1960), who

*B-, OC *A- > MC *A-. noticed that, in a xiéshēng series containing MC

A theory explaining patterns of xiéshēng con- *l- and a non-lateral initial *C-, *C- frequently

nections with clusters is actually a bundle of occur in Division-II syllables, while *l- often cor-

three theories: a proto-phonology of OC, a the- relates with Division I. For example, the pho-

ory of cluster simplifijication between OC and netic element jiān 監 *kæmII ‘inspect’ occurs in

MC, and a theory on the workings of the Chinese jiàn 鑑 *kæmHII ‘mirror’, lán 藍 *lamI ‘indigo’

script. Karlgren reconstructed only *AB- clusters and làn 濫 *lamHI ‘excess’. Moreover, læmII is

with rising sonority (*bl-, *sn- and *kʰs-, but not not a possible MC syllable. Accordingly, Yakhon-

*lb- or *skʰ); most of his OC *AB- clusters simpli- tov reconstructed OC *Cl- clusters as the origin

fijied to *A- in MC, except for *bl-, *ɡl- > MC *l-. of Division II vocalism: MC *kæmII < OC *klam.

A xiéshēng series with *AB- can include words OC *lam stayed MC *lamI, whence the absence

with both *A- and *B-. of læmII.

Consonant stacking was the fijirst system- Yakhontov’s *Cl- is revised to *Cr- in later

atic method in the reconstruction of OC ini- treatments. With important contributions by

tial clusters. Perceived as synonymous with the Pulleyblank (1962) and Li Fang-Kuei (1970),

hypothesis of initial clusters in OC, Karlgren’s scholars gradually converged on a set of hypoth-

methodology invited widespread criticism, eses, collectively dubbed the *-r- hypothesis:

especially among Chinese scholars, starting with

epigrapher Táng (1937, 1949:35–46). Accord- 1. Division II syllables, unlike Division I or IV,

ing to Wáng Lì’s influential criticism (1958:68, come from OC *Cr-: compare bái 白 *bækII

1987:32–34), Karlgren cherry-picked his xiéshēng < *bˤrak ‘white’ and bó 泊 *bakI < *[b]ˤak

patterns. If Karlgren had applied his reconstruc- ‘calm’;

tion method consistently, the OC onset system 2. For the controversial → chóngniǔ rhymes,

would be full of bizarre stacked clusters like Division IIIb syllables (chóngniǔ sānděng

*ɕŋ- or *kʰȶʰ- and would lose all phonological 重紐三等) had OC *-r-, while Division IIIa

systematicity. (chóngniǔ sìděng 重紐四等) did not: com-

In general, there was a widespread sentiment pare mì 密 *mitIIIb < *mri[t] ‘dense’ and mì 蜜

that xiéshēng was too shaky a ground on which *mjitIIIa < *mit ‘honey’; and

to base the existence of clusters. This view was 3. MC retroflex initials, non-existent in Divi-

upended by the *-r- hypothesis, to be discussed sions I and IV, come from *T(S)r- clusters:

in Section 4, which demonstrated the reliability zhī 知 *ʈieIII < *tre ‘know’, zhāi 齋 *tʂɛjII <

of xiéshēng evidence through corroboration by *tsˤr[ə]j ‘purify oneself ’.

a wealth of other evidence. Apart from *Cr-

clusters, *sC- clusters are now also reconstructed The reconstruction of OC *-r- proved a unify-

by most scholars, and will be discussed in Sec- ing element that gave a parsimonious expla-

tion 5. nation for a range of phenomena in Chinese

historical phonology. The hypothesis is also sup-

4. * Cr- Clust e r s ported by Sino-Tibetan cognates: bā 八 *pɛtII <

*pˤret ‘eight’ and bǎi 百 *pækII < *pˤrak ‘hun-

MC *l- has xiéshēng connections with a wide dred’ to Tibetan brgyad and brgya respectively

variety of onsets, for which Karlgren recon- (both from earlier *brj- as per Li Fang-Kuei’s law:

structed *Cl- clusters. Every rhyme in the MC Tibetan rgy- < *rj-), pí 羆 *pieIIIb < *praj ‘brown

phonological system belongs to a → division bear’ to Zbu Rgyalrong /prɑʔ˥˥/, shī 蝨 *ʂitIII <

(děng): I, II, III(a/b) or IV, a distinction whose *srik ‘louse’ to Japhug Rgyalrong /zrɯɣ/, and by

nature remains controversial today but which Wanderwörter of Greater Southeast Asia, nota-

most scholars believe was related to vowel qual- bly jiāng 江 *kæwŋII < *kˤroŋ ‘river, Yangtze’

ity and medial glides (→ Traditional Chinese to Thai คลอง /kʰlɔɔŋ˧˧/ ‘canal’ and Thổ (Vietic)

Phonology). The fijirst defijinite breakthrough on /kʰrɔŋ¹/ ‘river’. Finally, it is supported by regular

For use by the Author only | © 2017 Koninklijke Brill NV

Consonant Clusters 668

alternations that suggest a causative infijix *<r>, The reconstruction of voiceless sonorants

cf. zhì 至 *tɕijHIII < *ti[t]-s ‘to arrive’ and zhì 致 as above permitted clusters of the *sN- type

*ʈijHIII < *t<r>i[t]-s ‘to send’, between chū 出 to instead be postulated, following Li Fang-

*tɕʰwitIII < *t-kʰut ‘to go out’ and chù 黜 ʈʰwitIII kuei (1971, 1976), for the xiéshēng connections

< *t-kʰ<r>ut ‘to expel’. between MC s- and N-. This is what we fijind in

An important hypothesis that started with most recent reconstruction systems. The word

Coblin (1986) suggests that coronal *T(S)r- clus- sāng 喪 *saŋI ‘mourning’, written with máng 亡

ters reconstructed in (3), rare in other Sino- *miaŋIII ‘flee, die’ as the phonetic component,

Tibetan languages, should be revised to *rT(S)-. is reconstructed with the cluster *sm-, which

For example, zhuàng 撞 ɖæwŋHII, *N-tˤroŋ-s simplifijied to MC s-. Likewise for xī 西 *sejIV

‘strike’ in the Baxter-Sagart system, would < *s-nˤər ‘west’, cf. nǎi 迺 *nəjXI ‘then’; xiè 褻

be revised to *r-N-tˤoŋ-s and compared with *sietIII < *s-ŋet ‘garment next to the body’, cf. yì

Tibetan rdung < *rⁿd- ‘strike, pound’. 槷 *ŋetIV ‘pole’; sì 賜 *sieHIII < *s-lek-s ‘bestow’,

Apart from *Cr-, many scholars have also cf. yì 易 *jeHIII < *lek-s ‘easy’. As predicted by

reconstructed *Cl-, where *-l- disappeared in the *-r- hypothesis, *sr- gave MC ʂ-: shǐ 使 *ʂiXIII

MC without trace. The word gè 各 *kakI ‘each’ < *s-rəʔ ‘send’, cf. lì 吏 *liHIII < *[r]əʔ-s ‘offfijicer’.

in the same xiéshēng category as 落 lakI ‘fall’ is OC *s-stop clusters likely existed, by a typo-

reconstructed by Zhèngzhāng (2003) as *klaːɡ in logical argument that *s-sonorant clusters imply

contrast to gé 格 *kækII ‘go to’ < *kraːɡ. *s-stop clusters (Goad 2011). However, compet-

ing hypotheses typically reconstruct *s-stop

5. * s C- Clust e rs clusters in a more limited scope:

Two diffferent hypotheses reconstruct *s-sonorant 1. In his 1958 talk, Bodman fijirst mentioned the

clusters in OC for diffferent lexical sets. possibility of a metathesis, or rather afffrica-

The fijirst hypothesis postulates *s-sonorant tion, MC *ts- < OC *st-. This proposition was

clusters for the voiceless element in the xiéshēng later elaborated in Pulleyblank (1962) and

connections *m-/*x(w)- (měi 每 *mwəjXI ‘every’ Bodman (1969), where they are extended to

and huǐ 悔 *xwəjXI ‘regret’), *ŋ-/*x- (yí 儀 *ŋieIIIb other stops: OC *sk-, *sp- are also recon-

‘ceremony’ and xī 犧 *xieIIIb ‘sacrifijicial animal’), structed for MC *ts-;

*n-/*th- (nán 難 *nanI ‘difffijicult’ and tān 灘 *thanI 2. A competing hypothesis, fijirst proposed in Li

‘foreshore’). In earlier studies (Maspero 1920, Fang-kuei (1971), had OC *sk-, *st- simplifying

1930, Karlgren 1957), these are reconstructed by to *s-; and

consonant stacking, as *mx- (later *xm-), *xŋ- 3. Baxter and Sagart (2014) reconstructed a frica-

and *thn-. Yakhontov (1960) proposed that the tivizing efffect for *s-, with OC *sts- > MC *s-,

prenasal element in Karlgren’s *xm-, *thn- and OC *st- > *stɕ- > MC *ɕ-.

*xŋ- should be unifijied into an archiphoneme,

which comes from a common earlier *s-. Recent reconstructions agree on some clus-

On the other hand, Li Fang-kuei (1935) and ters and difffer on others (see Table 1 for some

Tung (1948) analyzed the *m-/*x(w)- connection examples). This difffijiculty of reconstructing

in terms of a voiceless sonorant *m̥ - > *x(w)-. *s-stop clusters can be understood by analogy

Pulleyblank (1962) extended their proposals and to Tibetan, where Old Tibetan *s-sonorant clus-

reconstructed not only *m̥ -, *n̥ - and *ŋ̥-, but also ters show distinctive modern reflexes in most

*l̥- (*r̥- in later reconstructions), for the xiéshēng modern dialects, while *s-stop clusters are dis-

connections *th-/*l-: tǐ 體 *thejXIV < *r̥ˤijʔ ‘body’ tinguished from other cluster or simplex initials

and lǐ 禮 *lejXIV < *rˤijʔ ‘rites’, as well as *θ- only under specifijic phonological environments,

(*l̥- in later reconstructions) for *th-/*j-: tōu 偷 and only in some dialects.

*thuwI < *l̥ˤo ‘steal’ and yú 俞 *juIII < *lo ‘yes’. The prefijix /s-/ is a common causativizer in

Recent reconstructions mostly prefer the voice- other Sino-Tibetan languages, so a transitivizing

less sonorant treatment. function is reconstructed for OC *s- in many

For use by the Author only | © 2017 Koninklijke Brill NV

669 Consonant Clusters

systems. The Baxter-Sagart system, for example, cognates for systematic comparison. Usually

has shì 示 *ʑijHIII < *s-dʑijs < *s-gijʔ-s ‘show’ only one or two genuine cognates can be found

derived from shì 視 *dʑijHIII < *gijʔ-s ‘look, see’. corresponding to any given proposed OC cluster.

As a result, conflicting hypotheses can often all

6. M e t h odologi ca l Ad va nces a nd be justifijied by the careful selection of one or two

Fut ure Dire cti ons Tibetan comparanda. Broadening comparison to

lesser-known Sino-Tibetan languages that pre-

Xiéshēng still forms the primary justifijication of serve consonant clusters is one avenue for future

many clusters in recent reconstructions of OC. research that remains promising.

As is shown by Zhèngzhāng’s (2003:121) reassess- Compared to Sino-Tibetan cognates, Chinese

ment of Wáng Lì’s criticism, the treatment of loanwords in Bái, Hmong-Mien, Kra-Dai and

xiéshēng evidence in recent reconstructions has Austroasiatic are often more reliably identifijied

made good progress since Karlgren’s time. More and contain features that predate MC. Also, it

systematic proto-phonologies, inspired by Old is agreed that → Mǐn 閩 dialects of Chinese do

Tibetan or Austroasiatic languages, achieved a not descend from MC and preserve some OC

better coverage of xiéshēng patterns. Karlgren’s features. One highly convincing hypothesis in

hypothesis that *AB- almost always simplifijies Baxter and Sagart (2014:163–165) combines evi-

into *A- is replaced by less simplistic models. dence from Mǐn and loans in Southeast Asian

However, an upper limit exists to the amount of languages. Proto-Mǐn is reconstructed by

phonetic information that can be mined from Norman (1973, 1974) with voiceless sonorants

xiéshēng. One problem is a lack of agreed-upon such as *lh- and *nh-. Chinese loans in other

constraints: scholars have a great degree of free- languages often have a stop prefijix in cognate

dom both in the choice of xiéshēng connections words: for example, liù 六 *liuwkIII ‘six’ (Proto-

to explain by clustering and in the cluster recon- Mǐn *lh-) is borrowed as Proto-Hmong-Mien

structions themselves. As an extreme exam- *kruk (Ratlifff 2010) and Proto-Tai *krokD (Pitta-

ple, scholars who work in Wáng Lì’s tradition yaporn 2009); ròu 肉 *ɲuwkIII ‘meat’ (Proto-Mǐn

regard all cases of *k-/*l- connections as excep- *nh-) is borrowed as /kɲuk⁷/ in Pong (Vietic).

tional (Sūn 2005). Hence, hypotheses that inte- Words with Proto-Mǐn voiceless sonorants are

grate xiéshēng with other sources of evidence therefore reconstructed by Baxter and Sagart as

achieve a better explanatory power than those sonorants with preinitials: *k.ruk (distinguished

relying on xiéshēng interpretation alone like from *kruk), *k.nuk.

Karlgren’s. A renewal of interest in OC morphological pro-

Other sources of evidence that have been used cesses (Sagart 1999, Jīn 2006, Schuessler 2007 are

include: Sino-Tibetan comparanda, Chinese some recent examples) has profoundly changed

loanwords in languages of Mainland Southeast the nature of OC reconstruction. Reconstructed

Asia, daughter languages apart from MC, and afffijixes like *-s, *<r> and *s- mutually support

reconstructed Chinese morphology. They are hypotheses concerning clusters *-Cs, *Cr- and

used to corroborate hypotheses suggested by *sC-. To take a recent example, the debate

xiéshēng evidence, but also permit the discovery between the two hypotheses involving *sC- clus-

of clusters invisible from xiéshēng evidence. ters mentioned before (Mei 2012, Sagart and

Scholars like Karlgren (1923:31) and Wáng Baxter 2012) crucially involves the nature and

Lì (1987:19) hoped that (Greater) Sino-Tibetan regularity of the morphological processes that

comparison could settle problems concerning are integrated with these hypotheses.

Chinese clusters. But the Sino-Tibetan → genetic

position of Chinese actually plays a limited role 7. C o n c lus i o n

in recent constructions (Gong 1990 being a nota-

ble exception). The usual approach privileges Disagreements about the reconstruction of OC

one language, Old Tibetan, as the object of com- clusters are apparent from Table 1, which pro-

parison, but this approach does not yield enough vides reconstructions in six diffferent systems.

For use by the Author only | © 2017 Koninklijke Brill NV

Consonant Clusters 670

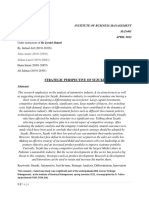

Table 1. Comparison of OC reconstructions

Character and MC Karlgren Wáng Li Fang- Zhèng- Pān Baxter-Sagart

reconstruction Lì kuei zhāng

lí 貍 *liIII ‘kind of wild cat’ *li̯əg *lĭə [*ljəg] *p·rɯ *[g]rɯ *p.rə

mái 霾 *mɛjII ‘dust storm’ *mlɛg *meə [*mrəg] *mrɯː *mgrɯɯ *mˤrə

héi 黑 *xəkI ‘black’ *χmək *xə̆ k *hmək *hmlɯːg *m̥ hɯɯg *m̥ ˤək

mò 墨 *məkI ‘ink’ *mək *mə̆ k *mək *mlɯːg *mɯɯg *C.mˤək

xū 戌 *switIII ‘eleventh [*si̯wĕt] *sĭwə̆ t [*smit] *smid *smig *s.mi[t]

earthly branch’

miè 滅 *mjietIIIa ‘destroy’ *mi̯at *mĭăt *mjiat *med *med *[m]et

jiàng 匠 *dziaŋHIII *dzʿi̯aŋ *dzĭɑŋ [*dzjaŋh] *sbaŋs *sbaŋs *s.baŋ-s

‘craftsman’

zào 造 *tshauHI ‘go to’ *tsʿôg *tsʿəu *skhəgwh *skʰuːgs *skhuugs *(mə)-tsʰˤuʔ-s

jiǔ 酒 *tsiuwXIII ‘liquor’ *tsi̯ôg *tsĭəu *tsjəgwx *ʔsluʔ *skluʔ *tsuʔ

jīng 莖 *ɣɛŋII ‘stalk’ *gʿěng *ɣeŋ [*griŋ] *greːŋ *greeŋ *m-k-lˤ<r>eŋ

Note: Brackets mark extrapolated forms. For Wáng Lì, Pān, and Baxter-Sagart, forms are not taken

from their respective monographs, but books or online resources with a more exhaustive cover-

age. Karlgren = Karlgren (1957), Wáng Lì = Guō (2010), Li Fang-Kuei = Li (1970, 1971), Zhèngzhāng

= Zhèngzhāng (2013), Pān = Dōngfāng Yǔyánxué (2015), http://www.eastling.org/oc/oldage.aspx,

Baxter-Sagart = Baxter and Sagart (2014), Version 1.1, http://ocbaxtersagart.lsait.lsa.umich.edu/.

Despite the inherent difffijiculty of reconstructing Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology,

OC initial consonants given methodological and Academia Sinica 39, 1969, 327–345.

Chén Dúxiù 陳獨秀, “Zhōngguó gǔdài yǒu fùshēngmǔ

evidential constraints, there is reason to hope shuō 中國古代有複聲母說” [On the existence of

that improved understanding of OC morphol- complex initials in Ancient China], Dōngfāng zázhì

ogy and judicious use of comparative data from 東方雜誌, 1937, 20–21.

Southeast Asian and Sino-Tibetan languages Coblin, South, A Sinologist’s Handlist of Sino-Tibetan

Lexical Comparisons, Monumenta Serica Mono-

will drive signifijicant improvements in future

graph Series XVIII, Nettetal: Steyler, 1986.

research into the reconstruction of OC and its Gabelentz, Georg von der, Chinesische Grammatik,

consonant clusters. mit Ausschluss des niederen Stils und der heutigen

Umgangssprache [Chinese grammar, excluding the

Bibliography low style and the contemporary spoken language],

Leipzig: Weigel, 1881.

Goad, Heather, “The Representation of sC Clusters”,

Primary Sources

in: Marc van Oostendorp, Colin Ewen, Elizabeth

Duàn Yùcái 段玉裁, Liùshū yīnjūnbiǎo 六書音均 Hume and Keren Rice, eds., The Blackwell Compan-

表, Fùshùn Guānxiè 富順官廨, 1776, reprinted in ion to Phonology, Oxford: Blackwell, 2011, 898–923.

Shuōwén Jiězì zhù 說文解字注, Jīngyùnlóu 經韻 Gong Hwang-cherng 龔煌城, “Cóng Hànzàngyǔ de

樓, 1815. bǐjiào kàn Shànggǔ Hànyǔ ruògān shēngmǔ de

nǐcè 從漢藏語的比較看上古漢語若干聲母的擬

References 測”, [Reconstruction of some initials in Archaic

Chinese from the viewpoint of comparative Sino-

Baxter, William H., A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonol- Tibetan], Xīzàng yánjiū lùnwénjí 西藏研究論文集

ogy, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1992. 3, 1990, 1–18.

Baxter, William H. and Laurent Sagart, Old Chinese: Gong Hwang-cherng 龔煌城, “Cóng Hàn, Zàng yǔ

A New Reconstruction, Oxford: Oxford University de bǐjiào kàn Hànyǔ shànggǔyīn liúyīn yùnwěi

Press, 2014. de nǐcè 從漢、藏語的比較看漢語上古音流音韻

Bodman, Nicholas, “Tibetan Sdud “Folds of a Gar- 尾的擬測” [Reconstruction of liquid codas in Old

ment”, the Character 卒, and the *St-Hypothesis”, Chinese from the viewpoint of comparative Sino-

For use by the Author only | © 2017 Koninklijke Brill NV

671 Consonant Clusters

Tibetan], Xīzàng yánjiū lùnwénjí 西藏研究論文集 zhōunián jìniàn lùnwénjí 總統蔣公逝世週年紀念

4, 1993, 1–18. 論文集 [Memorial volume to President Chiang

Gong, Hwang-cherng, “The First Palatalization of Kai-shek], Taipei 台北: Academia Sinica 中央研

Velars in Late Old Chinese”, in: Matthew Y. Chen 究院, 1976.

and Ovid J. L. Tzeng, eds., In Honor of William Lǐ Lán 李蓝, Húnán Chéngbù Qīngyī Miáorén huà

S-Y. Wang: Interdisciplinary Studies on Language 湖南城部的青衣苗人话 [Qīngyī Miáo Chinese

and Language Change, Taipei: Pyramid Press, 1994, of Chéngbù, Húnán Province], Běijīng 北京:

131–142. Zhōngguó shèhuìkēxué 中国社会科学出版社,

Gong Hwang-cherng 龔煌城, “Lǐ Fāngguì xiānshēng 2004.

de shànggǔyīn xìtǒng 李方桂先生的上古音系 Lín Yǔtáng 林語堂, “Gǔ yǒu fùfǔyīn shuō 古有複輔音

統” [The phonological system of Old Chinese as 說” [On the existence of consonant clusters in older

reconstructed by Fang-kuei Li], in: Pang-Hsin Ting Chinese], Chénbào liùzhōunián jìniàn zēngkān 晨

丁邦新 and Anne O. Yue 余靄芹, eds., Hànyǔshǐ 報六週年紀念增刊, 1924, 206–216.

yánjiū: jìniàn Lǐ Fāngguì xiānshēng bǎinián Maspero, Henri, “Le dialecte de Tchang-ngan sous

mí ngdàn lùnwénjí (Yǔyán jì yǔyánxué zhuānkān les T’ang” [The Chang’an dialect during the Tang

wàibiān zhī’èr) 漢語史研究:紀念李方桂先生 Period], Bulletin de l’Ecole française d’Extrême-

百年冥誕論文集 (語言暨語言學專刊外編之二) Orient 20, 1920, 1–124.

[Essays in Chinese historical linguistics: Festschrift Maspero, Henri, “Préfijixes et dérivation en chinois

in memory of professor Fang-Kuei Li on his cen- archaïque” [Prefijixes and derivations in Archaic

tennial birthday (Language and Linguistics Mono- Chinese], Mémoires de la Société de Linguistique de

graph Series Number W-2)], Taipei 台北: Institute Paris 23/5, 1930, 313–327.

of Linguistics, Academia Sinica 中央研究院語言 Mei, Tsu-lin, “The Causative *s- and Nominalizing

學研究所, Seattle: University of Washington, 2005, *-s in Old Chinese and Related Matters in Proto-

57–93. Sino-Tibetan”, Language and Linguistics 13/1, 2012,

Guō Xīliáng 郭锡良, Hànzì gǔyīn shǒucè (zēngdìngběn) 1–28.

汉字古音手册(增订本) [A handbook of histor- Norman, Jerry, “Tonal Development in Min”, Journal

ical pronunciation of Chinese characters (revised of Chinese Linguistics 1/2, 1973, 222–238.

and expanded version)], Běijīng 北京: Shāngwù Norman, Jerry, “The Initials of Proto-Min”, Journal of

商务印书馆, 2010. Chinese Linguistics 2/1, 1974, 27–36.

Haudricourt, André-Georges, “De l’origine des tons en Pān Wùyún 潘悟云, Hànyǔ lìshǐ yīnyùnxué 汉语历

vietnamien” [The origin of tones in Vietnamese], 史音韵学 [Historical phonology of Chinese],

Journal Asiatique 242, 1954a, 69–82. Shànghǎi 上海: Shànghǎi jiàoyù 上海教育出版社,

Haudricourt, André-Georges, “Comment reconstruire 2000.

le chinois archaïque” [How to reconstruct Archaic Pittayaporn, Pittayawat, “The Phonology of Proto-

Chinese], Word 10/2–3, 1954b, 351–364. Tai”, dissertation, Cornell University, 2009.

Jīn Lǐxīn 金理新, Shànggǔ Hànyǔ xíngtài yánjiū 上古 Pulleyblank, Edwin, “The Consonantal System of Old

汉语形态研究 [A study of Old Chinese morphol- Chinese”, Asia Major 9/58, 1962, 58–144, 206–265.

ogy], Héféi 合肥: Huángshān 黄山书社, 2006. Pulleyblank, Edwin, “Review: The Roman Empire

Karlgren, Bernhard, Analytic Dictionary of Chinese and as Known to Han China”, Journal of the American

Sino-Japanese, Paris: Geuthner, 1923. Oriental Society 119/1, 1999, 71–79.

Karlgren, Bernhard, “Compendium of Phonetics Ratlifff, Martha, Hmong-Mien Language History,

in Ancient and Archaic Chinese”, Bulletin of the Canberra: Pacifijic Linguistics, 2010.

Musuem of Far Eastern Antiquities 26, 1954, 211–367. Sagart, Laurent, The Roots of Old Chinese, Philadel-

Karlgren, Bernhard, Grammatica Serica Recensa, phia: John Benjamins, 1999.

Stockholm: Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, Sagart, Laurent and William H. Baxter, “Reconstruct-

1957. ing the *s- Prefijix in Old Chinese”, Language and

Li Fang-kuei, “Archaic Chinese *-i̯wəng, *-i̯wək, and Linguistics 13/1, 2012, 29–59.

*-i̯wəg”, Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philol- Schuessler, Axel, ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old

ogy 5, 1935, 65–74. Chinese, Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press,

Li Fang-kuei 李方桂, “Zhōngguó shànggǔyīn shēngmǔ 2007.

wèntí 中國上古音聲母問題” [Notes on Archaic Schuessler, Axel, Minimal Old Chinese and later Han

Chinese initials], Xiānggǎng Zhōngwén dàxué Chinese: A Companion to Grammata Serica Recensa,

Zhōngguó wénhuà yánjiūsuǒ xuébào 香港中文大 Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2009.

學中國文化研究所學報 3/2, 1970, 511–519. Starostin, Sergei, Rekonstrukcija drevnekitaiskoj

Li Fang-kuei 李方桂, “Shànggǔyīn yánjiū 上古音研 fonologičeskoj sistemy [A reconstruction of the Old

究” [Studies in Old Chinese phonology], Journal of Chinese phonological system], Moscow: Nauka,

Chinese Studies: New Series 9, 1971. 1989.

Li Fang-kuei 李方桂, “Jǐgè shànggǔ shēngmǔ wèntí Sūn Yùwén 孙玉文, “Shànggǔyīn gòunǐ de jiǎnyàn

幾個上古聲母問題” [Several problems on Old biāozhǔn wèntí 上古音构拟的检验标准问题”

Chinese initials], in: Zǒngtǒng Jiǎnggōng shìshì [On the criteria of evaluating Old Chinese recon-

For use by the Author only | © 2017 Koninklijke Brill NV

Contraction 672

structions], Yǔyánxué lùncóng 语言学论丛 31, Contraction

2005, 104–148.

Táng Lán 唐蘭, “Lùn gǔ wú fùfǔyīn fán láimǔzì gǔ

dúrú nímǔ 論古無復輔音凡來母字古讀如泥 Contraction refers to phonological processes by

母” [On the absence of consonant clusters in Old which a sequence of sounds that constitutes

Chinese. All cases of Middle Chinese *l- were one or more words is reduced or fused (Trask

pronounced *n-], Qīnghuá dàxué xuébào (zìrán 1996:92). The reduction may be accompanied

kēxué bǎn) 清華大學學報(自然科學版) 2, 1937.

Táng Lán 唐蘭, Zhōngguó yǔyīnshǐ 中國語音史 by additional changes of the sound segments;

[Chinese historical phonology], Shànghǎi 上海: these changes usually belong to the family of

Kāimíng 開明書店, 1949. lenition processes (Kuo 2010; Bauer 1988). From

Tung T’ung Ho 董同龢, “Shànggǔ yīnyùn biǎogǎo the perspective of the process itself, contrac-

上古音韵表稿” [Tentative tables of Old Chinese

phonology], Zhōngyāng yánjiūyuàn lìshǐ yǔyán tion in Chinese does not difffer notably from

yánjiūsuǒ jí kān 中央研究院歷史語言研究所集刊 contraction in other languages. In a similar way

18, 1948, 1–249. in which Latin atque ‘and also’ can be reduced

Wáng Fǔshì 王辅世 and Máo Zōngwǔ 毛宗武, to ac, → Classical Chinese zhīyú 之於 ‘this at’ can

Miáoyáoyǔ gǔyīn gòunǐ 苗瑶语古音构拟 [The

reconstruction of Proto-Miáo-Yáo], Běijīng 北京: be reduced to zhū 諸 (Mandarin character read-

Zhōngguó shèhuìkēxué 中国社会科学出版社, 1995. ings are given for convenience here; the earlier

Wáng Hóngjūn 王洪君, “Hànyǔ chángyòng de readings were, of course, quite diffferent, as will

liǎngzhǒng yǔyīngòucífǎ, cóng Píngdìng érhuà hé be clarifijied below). However, due to the mono-

Tàiyuán qiàn-l-cí tán qǐ 汉语常用的两种语音构

词法, 从平定儿化和太原嵌l词谈起” [Two com-

syllabicity of most of its morphemes (Norman

mon phonetic word formations in Chinese, the 1988:138) and the morpheme-syllabic character

case of rhotacization in the Píngdìng dialect and of its writing system (Chao 1968:102), Chinese

the l-infijixed words in the Tàiyuán dialect], Yǔyán shows specifijic characteristics regarding the per-

yánjiū 语言研究 1, 1994, 65–78.

ception of contraction. Thus, contraction is more

Wáng Lì 王力, Hànyǔ yǔyīnshǐ 汉语语音史 [The pho-

nological history of Chinese], Wáng Lì wénjí 王力 prominently perceived if it results in syllable

文集 10, Jǐnán 济南: Shāndōng jiàoyù 山东教育出 reduction, although this is not a necessary con-

版社, 1987. sequence of the process. This is also reflected in

Wáng Lì 王力, Hànyǔ yǔyīnshǐ 汉语史稿 [Towards a the literature where syllable contraction (Tseng

history of the Chinese language], revised edition,

Běijīng 北京: Kēxué 科学出版社, 1958. 2008), also called syllable fusion (Kennedy 1940),

Xú Tōngqiāng 徐通锵, “Shānxī Píngdìng fāngyán de or syllable merger (Duanmu 2000:302f), is the

‘érhuà’ hé Jìnzhōng suǒwèi de ‘qiàn-l-cí’ 山西平 most frequently discussed instance of contrac-

定方言的 ‘儿化’ 和晋中所谓的 ‘嵌l词’ ” [Ér-afffijix- tion, and fusion words (words resulting from the

ation in the Píngdìng dialect of Shānxī Province

and so called ‘l-infijixed words’ in Central Shānxī], fusion of two or more syllables) are the most

Zhōngguó yǔwén 中国语文 6, 1981, 408–415. frequently given examples. Nevertheless, there

Yakhontov, Sergei Yevgenevich, “Sočetanija soglasnyx are many cases in spoken Chinese where sound

v drevnekitajskom jazyke” [Consonant clusters sequences are reduced but no syllable reduc-

in Old Chinese], Moscow: 25th International

Congress of the Orientalists, 1960. tion occurs. Thus, Standard Chinese jìdé 記得

Zhèngzhāng Shàngfāng 郑张尚芳, Shànggǔ yīnxì ‘remember’ is often realized as [ʨi⁵¹ə¹] instead of

上古音系 [Old Chinese phonology], Shànghǎi [ʨi⁵¹tə³⁵], and xiānshēng 先生 ‘Mr.’ is often real-

上海: Shànghǎi jiàoyù 上海教育出版社, 2003. ized as [ɕiɛ̃⁵⁵əŋ³] instead of [ɕiɛn⁵⁵ʂəŋ⁵⁵] (Chung

Zhèngzhāng Shàngfāng 郑张尚芳, Shànggǔ yīnxì

(dì èr bǎn) 上古音系(第二版)[Old Chinese

2006:79). In both cases, the original number of

phonology (2nd Edition)], Shànghǎi 上海: Shànghǎi syllables is retained in the contracted forms, and

jiàoyù 上海教育出版社, 2013. there is no change in written representation.

Xun Gong & Yunfan Lai 1. F us i o n Wo r d s , L i g a t ur e s , a n d

P o r t ma n t e a ux

Due to the dominant role the writing system

played and plays in the history of Chinese

For use by the Author only | © 2017 Koninklijke Brill NV

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5807)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- APL Prager PDFDocument146 pagesAPL Prager PDFTom TraddlesNo ratings yet

- Mannesmann Vs VodafoneDocument17 pagesMannesmann Vs VodafoneDiana MoiseNo ratings yet

- (CD) Desmoparan vs. PeopleDocument2 pages(CD) Desmoparan vs. PeopleRaineNo ratings yet

- Report On KFCDocument24 pagesReport On KFCSäñtosh Ädhïkärï67% (3)

- RJ ThemesDocument47 pagesRJ Themesapi-249583009No ratings yet

- Hom Alg Oxford Sheet 4Document2 pagesHom Alg Oxford Sheet 4Tom TraddlesNo ratings yet

- Monads Are Trees With GraftingDocument12 pagesMonads Are Trees With GraftingTom TraddlesNo ratings yet

- Irony OdtDocument1 pageIrony OdtTom TraddlesNo ratings yet

- Gerund GerundiveDocument2 pagesGerund GerundiveTom TraddlesNo ratings yet

- New Words 1966Document4 pagesNew Words 1966Tom TraddlesNo ratings yet

- DickensworldDocument8 pagesDickensworldTom TraddlesNo ratings yet

- Oratio Obiqua ChartDocument2 pagesOratio Obiqua ChartTom TraddlesNo ratings yet

- The Law and The LadyDocument265 pagesThe Law and The LadyTom TraddlesNo ratings yet

- Programming by NumbersDocument28 pagesProgramming by NumbersTom TraddlesNo ratings yet

- Rank and NullityDocument4 pagesRank and NullityTom TraddlesNo ratings yet

- Seven Dogmas of Category TheoryDocument2 pagesSeven Dogmas of Category TheoryTom TraddlesNo ratings yet

- Category Theory DefinitionsDocument1 pageCategory Theory DefinitionsTom TraddlesNo ratings yet

- Cory Doctorow - Little BrotherDocument155 pagesCory Doctorow - Little BrotherRica Anjanette CapistranoNo ratings yet

- Bunkhouse RuleDocument1 pageBunkhouse RuleBeverly FGNo ratings yet

- 05 Completing The Accounting Cycle PROBLEMSDocument5 pages05 Completing The Accounting Cycle PROBLEMSbetlogNo ratings yet

- The Story of KeeshDocument4 pagesThe Story of KeeshEmman SanoNo ratings yet

- ITAD Ruling No. 198-00 (Rental Payments-Singapore)Document3 pagesITAD Ruling No. 198-00 (Rental Payments-Singapore)Joey SulteNo ratings yet

- SchindlerDocument120 pagesSchindlerZuresh PathNo ratings yet

- Al GhazaliDocument8 pagesAl GhazaliMajid YassineNo ratings yet

- Dr. Jeffrey Kamlet Litigation Documents 10.18Document172 pagesDr. Jeffrey Kamlet Litigation Documents 10.18Phil AmmannNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 MoodleDocument36 pagesChapter 6 MoodleMichael TheodricNo ratings yet

- IndianDocument32 pagesIndianIndian WeekenderNo ratings yet

- HRM Practices Contribute To Organizational InnovationDocument11 pagesHRM Practices Contribute To Organizational InnovationSasi PreethamNo ratings yet

- Ethics Midterm ExamDocument2 pagesEthics Midterm ExamKimberly MilanteNo ratings yet

- Community Stakeholder Engagement Within A NonDocument6 pagesCommunity Stakeholder Engagement Within A NonAmar narayanNo ratings yet

- Ebook PDF The New Lawyer Foundations of Law 1st Edition PDFDocument42 pagesEbook PDF The New Lawyer Foundations of Law 1st Edition PDFruth.humiston148100% (36)

- Buying BehaviourDocument83 pagesBuying BehaviourchandamitNo ratings yet

- SM Final Report - SuzukiDocument41 pagesSM Final Report - SuzukiHafsa AzamNo ratings yet

- YUVASREEDocument1 pageYUVASREEJeevarathnam NaiduNo ratings yet

- FE Credit - Case - Study PDFDocument6 pagesFE Credit - Case - Study PDFVarun MittalNo ratings yet

- Serious Case Review Nursery ZDocument39 pagesSerious Case Review Nursery ZLaura HenryNo ratings yet

- New LookDocument2 pagesNew Lookrosendo bonilla100% (2)

- The Water Situation in Harare ZimbabweDocument15 pagesThe Water Situation in Harare ZimbabweFrank MtetwaNo ratings yet

- Digital Bridge To The CaribDocument44 pagesDigital Bridge To The CaribUNITED NATIONS GLOBAL ALLIANCE FOR ICT AND DEVELOPMENTNo ratings yet

- Kumagai Ishii-Kuntz Eds. Family Violence Japan Life Course 2016Document190 pagesKumagai Ishii-Kuntz Eds. Family Violence Japan Life Course 2016Beatrix Zsuzsanna HandaNo ratings yet

- 4 Foreigners Who Participated in Indian Freedom Struggle - TopYaps - TopYapsDocument6 pages4 Foreigners Who Participated in Indian Freedom Struggle - TopYaps - TopYapsraghavbawaNo ratings yet

- PHILARTSDocument3 pagesPHILARTSJan Armand CortezNo ratings yet

- Comfort Women: Slave of Destiny: Maria Rosa HensonDocument5 pagesComfort Women: Slave of Destiny: Maria Rosa HensonEmmarlone96No ratings yet