Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Letters From Yorkshire LitChart

Uploaded by

Jonas LUIOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Letters From Yorkshire LitChart

Uploaded by

Jonas LUICopyright:

Available Formats

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.

com

Letters from Yorkshire

reddening would suggest how bitterly cold it must be outside,

SUMMARY the speaker’s use of a pleasant, musical term gives manual labor

a sense of beauty. It seems, then, that the speaker is envious of

In February, while planting potatoes in his garden, he saw the

their acquaintance’s ability to go “out there, in the cold, seeing

first lapwing birds return from their winter migration. He then

the seasons turning,” while the speaker sits at their computer

went inside to write to me. His knuckles reddened in the

“feeding words into a blank screen.” Rather than being able to

warmth of the indoors, happy to be out of the cold.

“plant potatoes,” or give life back to the earth, the speaker

There's nothing romantic or extraordinary about his outdoor interacts only with the virtual world of a computer. The feeling

lifestyle. It just is what it is. You're outside in the cold, watching of being “cold” and the physical act of “planting potatoes” are

the seasons change, while I'm indoors typing articles at a tangible ways to relate to the natural world that the speaker

computer screen. Is your life more real than mine because cannot experience from her house.

you're a farmer and spend more time in nature?

The speaker then wonders if their acquaintance’s life is “more

You wouldn't say that's the case, especially while doing difficult real” because he is a farmer. With this question, the speaker

winter chores like shoveling snow and breaking ice off of a makes explicit their doubt about how much life they are

water container. Still, you're the one who writes to me and tells genuinely experiencing while sitting at their computer. The

me about this world that's so different from mine, and each of modern world, it seems, creates a barrier between people and

your letters brings a piece of that natural world to me. Even at the “real” world.

night, while we're watching the same news in separate, far-

The speaker knows, however, that their own perception of

away houses, our letters to each other help us to stay in touch

agrarian life is not the same as that of their correspondent. The

across the cold distance that separates us.

speaker thinks that their acquaintance “wouldn’t” describe his

agrarian lifestyle as “more real,” especially as he completes the

THEMES unpleasant tasks of “breaking ice on a waterbutt” and “clearing

a path through snow.” The speaker recognizes that their vision

of outdoor labor is romanticized, and by acknowledging these

AGRARIAN VS. MODERN LIFE multiple perceptions of agrarian life, the poem suggests that

In Maura Dooley’s “Letters from Yorkshire,” the neither lifestyle (agrarian or modern) is “more real” than the

speaker envisions an acquaintance (a friend, relative, other.

or lover) writing letters to the speaker after working outside in Even so, to the speaker, the acquaintance’s letters contain “air”

his garden. This acquaintance’s letters seem filled with the “air and “light,” and become metaphors for the kind of experiences

and light” of the natural world, causing the speaker to wonder if the speaker cannot have. The speaker seems to crave the

the letter writer’s experience is “more real” than the speaker’s connection to nature offered by the letter writer, while also

own—which is spent indoors at a computer. This wondering on sensing that the letter-writer does not crave news of the

the speaker's part suggests a nagging anxiety about modern speaker’s day-to-day in an office. The poem implies that a

life—that is, that this life, closer to a computer screen than to connection to nature is crucial to living a fulfilled life, and that

nature, is emptier than that spent working outside with one’s this connection is something that modern life does not

hands. Yet despite highlighting nature’s importance, the poem sufficiently provide.

also recognizes the degree to which a modern office worker

might romanticize or misunderstand the reality of agrarian life. Where this theme appears in the poem:

Throughout the poem, the speaker links the physical labor of

• Lines 1-3

their correspondent to a sensory experience of nature that is

• Lines 4-13

both meaningful and desirable. The poem opens with the

speaker’s acquaintance “planting potatoes” while seeing the

first “lapwings” (a kind of bird) return from migration. Even COMMUNICATION AND CONNECTION

though it is “February” and likely uncomfortable outside, the

“Letters from Yorkshire” explores several kinds of

speaker seems to think that these are pleasurable and

communication: letter-writing, the “heartful of

worthwhile moments for the letter writer.

headlines” belonging to the speaker (implied to be a journalist,

The speaker then describes his knuckles “singing as they or some sort of writer), and the “nightly news.” Of these three

reddened in the warmth” of the indoors. While this sudden forms of communication, the poem ascribes the most

©2020 LitCharts LLC v.007 www.LitCharts.com Page 1

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com

importance to letter-writing. Although the speaker can interact in his garden. Even though the penpal is the one writing to the

with the outside world via the news and her own articles, speaker about farm life, this scene is presented from the point

neither form of communication seems as meaningful to the of view of the speaker; this is how the speaker images the

speaker as do letters. This might be because, with a letter, the penpal spends his time. Right from the get go, then, the

speaker receives a window into the life and world of another speaker's fascination with and romanticization of farm work

person whom the speaker can interact with individually. The starts to become clear.

poem thus subtly suggests that genuine connection requires a It is still wintertime ("February"), but when looking through the

sense of intimacy and reciprocation. speaker's eyes, the outdoor work seems peaceful rather than

The poem’s opening lines make the intimate power of letter cold or harsh. The penpal digs in his garden, "planting potatoes,"

writing apparent. The poem begins with the speaker looking and sees a kind of bird (called a "lapwing") return, perhaps from

through the letter-writer’s eyes as he plants potatoes and a long migration. The alliter

alliteration

ation and consonance of these

watches “lapwings” return. The speaker also ascribes a musical descriptions imbue them with a sense of musicality, elevating

quality to the act of letter writing. In the third line of the first the penpal's humble labor. Note the hard /g/ sounds of

stanza, the speaker perceives their acquaintance’s knuckles as "digg

gging," the popping /p/ and /t/ of "pplantting pottattoes." His

“singing” as he begins crafting a letter indoors. This musical act knuckles, despite being subject to the cold air and soil, are

seems more intimate and positive than the speaker’s later "singing" as they "reddened in the warmth" of the indoors.

description of “feeding words onto a blank screen.” Unlike On a literal level, this refers to the way that people's hands turn

letter-writing, the poem suggests, writing articles isn’t a two- red when coming in from the cold, due to increased blood flow.

way form of communication; instead, it is a one-way stream of "Singing" evokes the tingling warmth that accompanies this

thoughts and information. As such, the blank screen cannot reddening. And by personifying the knuckles as "singing," the

offer the same warm connection that a letter can. speaker also imbues this reddening with a subtle sense of

The poem ends with the lines “So that / at night, watching the beauty and joy. This seeming joy is likely due, in part, to the

same news in different houses, / our souls tap out messages relief of being inside, out of the cold. The knuckles might also be

across the icy miles.” Both the speaker and their correspondent "singing" in joyful anticipation to "write" about the natural

may be engaged in the nightly news in separate houses, but world they just experienced. Either way, the speaker instills the

their habit of letter writing gives them a warm, soul-level entire scene with a sense of comforting, welcoming warmth,

intimacy that transcends “icy miles.” In this closing image, letter even though the farm work itself was cold and probably

writing is portrayed as a more powerful means of unpleasant to perform. At this early stage, the speaker seems to

communication than nightly news. Even though current events set up the natural world, and farm work, more specifically, as an

are obviously important, the speaker seems much more enviable and important aspect of their penpal's life.

interested in the news of their correspondent, which is that of

agriculture and the natural world. Rather ironically, this LINES 5-8

intimate news seems to make the speaker feel more connected It’s not romance, ...

to the world than does any nightly broadcast about the state of ... a blank screen.

that world, for the letters brings “air” and “light.” These two These next lines show the speaker acknowledging the fact that

qualities ("air" and "light"—two things that every living being their idea of farm work is likely a bit romanticized—that is, that

needs to survive) underline the vital necessity of one-on-one it paints an overly rosy or idealized picture of the farmer's life.

communication for the speaker. The speaker seems to catch themselves in the act, definitively

declaring: "It's not romance, simply how things are." The

Where this theme appears in the poem: caesur

caesuraa in the middle of this line plus the strong period end-

• Lines 2-4 stop add to this speaker's sense of assuredness. This line might

• Lines 7-8 seem a bit blunt in contrast to the peaceful, warm descriptions

• Lines 11-15 of farm life in the previous stanza, but the speaker is clearly

aware that their penpal does not see his own work as

"romantic." Instead, for the penpal, farm life isn't anything

interesting or exotic; it's just "how things are," as he spends his

LINE-BY

LINE-BY-LINE

-LINE ANAL

ANALYSIS

YSIS time "in the cold," watching the "seasons turning" year after

year.

LINES 1-4

The speaker, meanwhile, is occupied by a totally different line of

In February, digging ... work, sitting at a computer and "feeding words onto a blank

... in the warmth. screen." The word "headlines" suggests that the speaker is a

The poem opens with an image of the speaker's penpal working kind of journalist, while "heartful" implies that the speaker's

©2020 LitCharts LLC v.007 www.LitCharts.com Page 2

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com

writing is important to them. At the same time, the speaker involves "breaking ice on a waterbutt" (a kind of outdoor

doesn't seem to appreciate how that writing is shared, via the container for liquid) and "clearing a path through snow," both of

lonely act of typing words onto a "blank screen." While the which are physically draining tasks. As such, the penpal himself

penpal plants tangible nourishment in the form of "potatoes," all certainly wouldn't say that his life is any more "real" than the

the speaker can "feed" are "words" onto a computer. The speaker's. The full stop caesur

caesuraa in the middle of line 11 seems

screen being "blank" reflects the fact that there isn't a tangible to put an end to the speaker's wondering, suggesting an

person receiving the speaker's "heartful of headlines." Instead, acceptance of the penpal's point of view here.

these words seem simply to be sent out into the ether, into a This dose of self-awareness makes the speaker's affection for

blank space, with the speaker unable to know how they are the outdoors seem more genuine. The speaker is able to

received. This contrasts with letter writing, which is presented acknowledge that the natural world they long for is probably

as an intimate and reciprocal form of communication in the too idealized to be real, and that while they genuinely desire a

poem. connection with nature, they also simply want what they don't

As in the first stanza, the speaker ends the second stanza with have.

enjambment

enjambment. Line 6 flows across the stanza break into line 7.

Not coincidentally, these two lines present the stark difference LINES 11-13

between the speaker and the penpal's lives: Still, it’s you ...

... into an envelope.

... seeing the seasons Even after accepting the reality that the penpal's outdoor work

turning

turning, me with my ... is a lot harder and less enjoyable than the speaker imagines it to

be, the speaker still longs for a deeper connection with nature.

The fact that the description of the penpal "seeing the seasons / Following the full stop caesur

caesuraa of line 11 ("... through snow.. Still,

turning" spills over into the line that reveals the speaker's own it's you ...") the speaker describes the necessity of experiencing

line of work ("me with my heartful of headlines") subtly the natural world vicariously through their penpal.

suggests the connection between these two people—speaker Of note here is the fact that the speaker labels this agrarian

and penpal—despite the vast difference in their circumstances. lifestyle as an "other world," a simple, but distancing phrase that

Again, their letters allow a form of deep intimacy (this will be underlines how far removed the speaker feels from nature. The

reflected again in the poem's final stanza, which describes letters the speaker receives become more than letters, and are

these two people's "souls" communicating "across the icy instead vessels of "air and light." Air and light are the building

miles"). blocks of all life, and the speaker's decision to incorporate them

LINES 9-11 here is significant on a few levels.

Is your life ... First, the penpal's letters being full of air and light suggests that

... path through snow. that the speaker does not receive much of either on their own,

and that they rely on these epistolary exchanges as a kind of life

After acknowledging the difference between the speaker's

source. To the speaker, news of the natural world is as

modern life and the penpal's agrarian one, the speaker moves

important as receiving "air and light," which may sound

deeper into introspection. The speaker wonders if their

extreme, but it puts into perspective the degree of seclusion

penpal's life is "more real" because he "dig[s] and sow[s]"—that

the speaker feels as a result of working at her computer every

is, because he is a farmer, someone who works directly with his

day.

hands and with nature. The speaker here suggests that a life

involving nature, a life that allows physical interaction with Second, "air and light" bolster the speaker's earlier doubt that

plants and the outdoors ("dig and sow"), is more fulfilling or their computer-based lifestyle is not as "real" as being in

rewarding somehow than a life tied to a computer screen. This nature. If "air and light" are required to live but are only found

question also amplifies the dissatisfaction the speaker has with in the natural world (albeit the penpal's described world), then

their computer-driven occupation, which shelters them from how could the speaker's darker, more secluded lifestyle seem

nature instead of allowing them to embrace it. The speaker as "real"? Via this description, the speaker seems to make a

ends the third stanza with this thought, the subsequent white larger claim about modern life itself, which is that it does not

space allowing the question to briefly linger in the air. have the capacity to include the natural world (or maybe even

life in general) in a meaningful or fulfilling way.

Of course, immediately after posing this question, the speaker

seems to refute it at the start of the next stanza. The speaker Again the speaker uses enjambment across stanzas here, with

acknowledges that their envy for their penpal's outdoor line 12 overflowing right across the stanza break into line 13:

lifestyle may not take into account the harsher reality of farm

work. In the next lines, the speaker clarifies that such work ... that other world

©2020 LitCharts LLC v.007 www.LitCharts.com Page 3

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com

pouring air and light ... screen.

This enjambment echoes the lines' content, evoking the

penpal's sending of that "news" to the speaker. It's as though POETIC DEVICES

that "news" is also being sent across the stanza break, which

here could represent the distance between these two "worlds." APOSTROPHE

The poem uses contains apostrophe throughout as the speaker

LINES 13-15 addresses a penpal who is not actually present. One of the most

So that ... striking instances comes in line 9, when the speaker wonders if

... the icy miles. this penpal's life is "more real" because he digs and sows—that

Up until the last stanza, the poem spends most of its time is, because he is a farmer and thus works with his hands in the

highlighting the differences between the speaker's modern natural world. Readers can tell from this question that the

lifestyle and the penpal's agrarian one. But in these final lines, speaker is dissatisfied, to some extent, with their modern

their lifestyle differences are set aside for a simple description lifestyle because it does not allow them to be in nature on a

of intimacy. The poem shows both the speaker and their penpal more regular basis.

"watching the same news in different houses." Even though The word "real" could also imply a lack of tangibility or physical

they are far apart, separated by "icy miles" during the winter, interaction in the speaker's life. Based on their descriptions of

their "souls tap out messages" (a metaphor for letter writing) their penpal's farming, the speaker seems interested in the

and they are still thinking about each other as the nightly news tangible ways he interacts with the natural world. For example,

plays. the farmer digs in his garden, "planting potatoes," and he

By ending with this image, the poem suggests that the understands the pleasure of his hands reddening with warmth

speaker's doubt about the "realness" of their modern lifestyle is after being out in the cold. The speaker's main means of

not as important as is the communication they share with their physical interaction, by contrast, is the simple act of typing

penpal. The sibilance of these lines, in turn, creates a gentle, words into a computer. The speaker likely believes their own

hushed sound that perhaps echoes the whispering of their life to be less "real" because they do not have as many different

"souls": things to touch and feel, and cannot relate to the world in as

physical a way. Instead, they are stuck in the virtual (perhaps

.... same newss in different houssess, the opposite of "physical") world of computer work.

our soulss tap out mess ssagess across

ss the iccy miless. It's also worth thinking about how apostrophe functions given

that this poem is in part about communication. The poem

With their mention of the "nightly news," these lines also ultimately suggests that intimate, reciprocal communication

perhaps echo the speaker's occupation as hinted at earlier in (such as letter writing) is more meaningful than one-way, mass

the poem. The fact that the speaker deals with "headlines" communication (such as news stories). Here, the speaker is

implies that they're a journalist, or at least someone who works asking a question to a figure who is not actually present,

in news. Given that both the speaker and the penpal are meaning the speaker's question is sent off into the world much

watching the "same news" in the end suggests that the like the speaker's "headlines" are fed "onto a blank screen." The

speaker's life is more real than it's been made out to be. poem's use of apostrophe, then, subtly bolsters the speaker's

Perhaps the speaker's work touches the farmer, connecting him sense of isolation in the modern world.

to the modern world, just as the farmer's work helps the

speaker feel more in touch with nature. Where Apostrophe appears in the poem:

All that said, despite knowing about the agrarian life of the

• Lines 6-7

speaker's penpal, there is much about him that readers still • Line 9

don't know by the poem's end. The speaker, in fact, portrays • Lines 10-15

him more as a resource for their own sustenance (especially

when he pours "air and light" into his envelopes) than as

ASSONANCE

someone engaging in a dialogue about the pros and cons of

living closer to nature. Readers do not know, for example, if this Although "Letters form Yorkshire" does not have a rh rhyme

yme

penpal has a positive impression of modern life, or if he feels scheme

scheme, it does contain several instances of assonance that add

any kind of detachment or isolation as a farmer. The question of to its musicality. In the first stanza, for example, the words

what this penpal thinks of the speaker's lifestyle is thereby left "diigging," "plantiing," "lapwiings," and "siingiing," all contain the

open, although the poem seems to suggest that a life closer to same internal short /i/ sound. Though these words are spread

nature is more fulfilling, overall, than a life spent at a computer throughout the stanza—and thus perhaps not true assonance in

©2020 LitCharts LLC v.007 www.LitCharts.com Page 4

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com

all cases—the /i/ sound repeats often enough that it still rings taking their time to describe it, slows down the pace of their

out clearly to the ear. This repetition links these words via writing to appreciate every detail, they demonstrate how

sound, all of which are associated with elements of the farmer's important it is to them. Note that these caesuras are also part

work. The speaker seems enchanted by this outdoor labor, and of examples of par

parataxis

ataxis, given that each element in these

the shared sounds here add a sense of lyricism to its phrases is as important as the next; the phrase order could be

description. In other words, the speaker's assonance in altered without any significant change in meaning ("planting

describing nature reflects the beauty that the speaker perceives potatoes, digging his garden" for instance). This creates the

in nature. sense that the speaker is simply listing off elements of the

Similar vowel sounds pervade the rest of the poem too; while farmer's life that the speaker seems to appreciate and admire,

these are often quite spaced out—and thus not really rather than building up a larger argument.

assonance—the poem is short enough that the sounds still The caesuras are also meaningful based on where they don't

bounce and echo off one another. For instance, note the many appear. Most significantly, in line 9, the speaker asks: "Is your

long /e/ sounds that reverberate across the second and third life more real because you dig and sow?" This is the only

stanzas in "see eeing," "sea

easons," "fee

eeding," "scree

een," and "rea

eal." And sentence in the poem that fits exactly onto one line. This line's

there is undeniable assonance in the poem's final two lines. lack of pause allows it to stand out from the rest of the poem,

Note the shared /ow/ sounds in "hou ouses," "ou

our," and "ou

out" and it emphasizes the sincerity with which the speaker

(further mirrored, on a visual level, by "sou ouls"), as well as the expresses doubt about the "realness" of her own modern life.

long /i/ of "iicy miiles." The line is also close to the exact middle of the poem, a formal

The poem may be written in free vverse

erse (in terms of its non- decision that perhaps shows this question to be at the center of

rhyming nature), but the quantity of repeated vowel sounds the speaker's thoughts (in addition to the poem's physical

throughout gives it a melodious feel. The repetition of these "center").

vowel sounds elevates the poem, making it feel almost like a

kind of ode to the natural world. The speaker conveys Where Caesur

Caesuraa appears in the poem:

uncertainty about the realness of their own modern life, but • Line 1: “February, digging,” “garden, planting”

seems consistently enchanted by nature and its potential to • Line 3: “me, his”

offer fulfillment. The sounds throughout the poem seem like a • Line 5: “romance, simply”

way for the speaker to reflect the beauty of nature within the • Line 6: “there, in,” “cold, seeing”

poem's language. • Line 7: “turning, me”

• Line 10: “so, breaking”

Where Assonance appears in the poem: • Line 11: “snow. Still, it’s”

• Line 13: “envelope. So”

• Line 1: “I,” “i,” “i,” “i,” “i”

• Line 14: “night, watching”

• Line 2: “i”

• Line 3: “i,” “i,” “i,” “i”

• Line 4: “e,” “e” CONSONANCE

• Line 6: “ee,” “ea” Consonance appears throughout "Letters from Yorkshire." Like

• Line 14: “i,” “i,” “ou” the previously discussed assonance

assonance, it helps imbue the poem

• Line 15: “ou,” “ou,” “i,” “i” with a musical quality that suggests a sort of reverence for the

natural world. Take the first line, with its many energetic /d/ and

CAESURA /g/ sounds in "d

digg

gging his gardden" and popping /p/ and /t/

The poem is broken up into three-line stanzas, but it's actual sounds of "pplantting pottattoes." Later, the /h/ consonance of

sentences/phrases don't always match up with that structure. "h

heartful of headlines" pushes the reader to linger on this

Instead, the speaker's thoughts frequently run over one line to phrase, an important moment in the moment that suggests

the next (enjambment

enjambment) and come to end in the middle of lines. what the speaker does for work (likely, the speaker is a

The caesur

caesuras

as in the poem add to its free-flowing quality, and journalist) and how the speaker feels about it (the speaker

also are ways for the speaker to convey meaning. seems to care, given that the group of headlines are described

as a "heartful").

For example, in the opening line—"In February,, digging his

garden,, planting potatoes,"—the speaker pauses at regular Especially prominent throughout the poem is the /s/ sound,

intervals to give added weight to each component of the technically an example of sibilance

sibilance. This sound becomes more

penpal's outdoor life. This same rhythm is echoed in line 6, prominent as the poem progresses. In the second stanza, the

which reads: "You out there,, in the cold,, seeing the seasons ..." words "romancce," "ssimply," "sseeing," and "sseasons" all draw

The speaker doesn't have regular access to the outdoors, and in attention to the /s/ sound. Later, the sound is striking in the

©2020 LitCharts LLC v.007 www.LitCharts.com Page 5

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com

poem's final line: "ssouls tap out mess

ssages across

ss the iccy miles." insight into the natural world would be possible, in which case

This imbues the line with a gentle, hushed tone, as if the this line break becomes a way of showing respect and

speaker is whispering to the farmer across the distance that appreciation for the verbal companionship the farmer provides.

separates them. The /s/ sound here thus connotes a sense of Finally, the enjambment between the fourth and fifth

intimacy and closeness. stanzas—"world / pouring"—evokes the lines' content: it's as

though that "world" filled with "air and light" is pouring itself

Where Consonance appears in the poem: right across the stanza break.

• Line 1: “d,” “gg,” “g,” “d,” “p,” “t,” “p,” “t,” “t”

• Line 3: “t,” “t,” “t” Where Enjambment appears in the poem:

• Line 5: “c,” “s” • Lines 2-3: “came / indoors”

• Line 6: “s,” “s” • Lines 3-4: “singing / as”

• Line 7: “m,” “m,” “h,” “l,” “h,” “d,” “l” • Lines 6-7: “seasons / turning”

• Line 8: “d,” “d,” “k,” “c” • Lines 7-8: “headlines / feeding”

• Line 9: “r,” “l,” “r,” “r,” “l” • Lines 11-12: “you / who”

• Line 10: “s,” “s” • Lines 12-13: “world / pouring”

• Line 11: “s,” “S”

• Line 12: “s,” “w,” “th,” “th,” “w”

• Line 13: “p,” “r,” “r,” “l,” “n,” “n,” “l,” “p”

IMAGERY

• Line 14: “s,” “s,” “s,” “s” The imagery in "Letters from Yorkshire" draws a distinction

• Line 15: “s,” “s,” “ss,” “s,” “ss,” “c,” “s” between the speaker's positive attitude towards the natural

world and their negative attitude towards their own modern

ENJAMBMENT lifestyle. In the first stanza, even though it is February and likely

cold, the speaker envisions their penpal enjoying the acts of

As mentioned in our discussion of caesur

caesuraa, the speaker in

"digging his garden, planting potatoes," and watching "the first

"Letters from Yorkshire" doesn't bother to make their thoughts

lapwings return."

conform to the poem's form. Sentences frequently spill over

from one line to the next, and often even across stanzas. In These descriptions build a sense of the farmer's daily world,

general, the many instances of enjambment bolster the poem's which is only just starting to show signs of spring life. The

free-flowing, reflective feel, and also add emphasis to phrases "reddening" of the knuckles, meanwhile, reminds readers just

and words separated by line breaks. how cold it must be outside. To the speaker, their penpal's

knuckles aren't simply relieved when they finally come indoors,

Looking at line 6, for instance, readers can see that "seasons" is

but instead are "singing ... in the warmth." "Singing" evokes the

broken off from "turning." In one reading, this definitively

tingling sensation as blood rushes back to your fingers after

separates "the seasons" from the speaker, who seems envious

being in the cold, and also has generally positive connotations.

of their penpal's ability to be "out there" in the natural world.

This imagery, then, shows that the speaker is starting to idealize

Because "seasons" is given added weight thanks to the

the farmer's life of manual labor in nature.

enjambment, it feels, for a moment, as though the speaker is

saying that they don't get to see any of the seasons in the first When they turn to their own modern life, however, the tone of

place (without even mentioning their ability to "turn"). Then the speaker's descriptions becomes more negative. In the third

again, this enjambment also allows the description of the stanza, the speaker says that their own work consists of

farmer's daily life to share a line with the description of the "feeding words onto a blank screen." These words contrast with

speaker's daily life (line 7, "turning ... headlines") —perhaps the penpal's capacity to physically relate to his surroundings

suggesting that they're not as different as they may seem, and through actions like planting potatoes in the ground or seeing

that both are equally "real." his cold knuckles turn red. Instead of growing food, the speaker

can only feed words into a repository that cannot interact with

Another notable example of enjambment occurs between lines her in the way the outside world can. Later on, although the

11 and 12: "Still, it's you / who sends me word of that other speaker acknowledges that working outdoors might be harder

world ..." Throughout the poem, the speaker seems more than the speaker thinks (in lines 10 and 11), they end the poem

concerned and interested with the world of their penpal rather by describing their penpal's letters being full of "air and light."

than the penpal himself, and yet this small instance of This ethereal image of natural elements being poured into a

enjambment suggests that the speaker does indeed care for small envelope shows how much the speaker values having

him. The break after "you," meaning the farmer, allows the word access to the outdoors, even if that access can only come in the

to hang in the air for a moment. The speaker seems to want to form of reading a letter.

underline that without the penpal, none of this wondrous

©2020 LitCharts LLC v.007 www.LitCharts.com Page 6

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com

and their acquaintance watch "the same news in different

Where Imagery appears in the poem:

houses" while their "souls tap out messages" to one another.

• Lines 1-4 Even though both individuals are watching TV, the suggestion

• Lines 7-8 that their "souls," or some interior, subconscious, part of their

• Lines 10-11 beings, are still in communication with one another implies that

• Lines 11-13 their act of letter-writing forged a deeper connection between

them. They are both separated by a significant distance ("icy

PERSONIFICATION miles"), but they feel connected by their identical evening

There is one example of personification in "Letters from routines and by knowing that the other is still in their thoughts.

Yorkshire," and it occurs in lines 3 and 4. When the speaker Word of the natural world is so meaningful to the speaker that

describes their penpal stepping indoors to "write to me," the it has helped them achieve a soul-level appreciation for the

penpal's knuckles are "singing / as they reddened in the relationship they have with their acquaintance.

warmth." Literally, this refers to the fact that his hands are

turning red as blood rushes to them after coming in from the Where Metaphor appears in the poem:

cold. But the speaker's choice of words here is significant. • Lines 11-15: “Still, it’s you / who sends me word of that

For one thing, "singing" is often associated with pleasure or joy. other world / pouring air and light into an envelope. So

Even though the penpal just spent time in cold, uncomfortable that / at night, watching the same news in different

weather, "digging his garden, planting potatoes," the penpal's houses, / our souls tap out messages across the icy

knuckles are happily "singing" after they come indoors. The miles.”

knuckles may be singing because they're glad to be warm, or

perhaps they are looking forward to working on a letter to the

speaker. But it is nevertheless clear that it is the speaker VOCABULARY

ascribing this joyful, musical quality to the penpal's daily life.

Later in the poem, the speaker acknowledges that working Lapwings (Line 2) - "Lapwings" are a kind of bird that appears

outside in the "cold," accomplishing tasks like "clearing a path in Britain (where the author of this poem, Maura Dooley, lives)

through snow" or "breaking ice on a waterbutt," may not and elsewhere across the globe.

actually be all that pleasant to perform, and that the speaker Singing (Line 3) - The penpal's knuckles are not actually

may be viewing the natural world with an idealized, "singing." Rather, this is a moment of personification that shows

romanticized perspective. In this case, the penpal's knuckles the extent to which the speaker idealizes the feeling of coming

"singing" reflects the speaker imagined idea of what working inside from the cold.

outdoors must be like rather than the penpal's reality.

Romance (Line 5) - "Romance," in this instance, refers to the

speaker's idealization of the natural world.

Where P

Personification

ersonification appears in the poem:

Heartful of headlines (Line 7) - "Heartful of headlines" likely

• Lines 3-4: “his knuckles singing / as they reddened in the refers to the speaker's occupation, which seems to be some

warmth.” form of journalism (which would involve writing a "headline").

The word "heartful" also suggests that this act of writing is dear

METAPHOR to the speaker, despite the speaker's longing to see more of the

"Letters from Yorkshire" contains several metaphors in the final natural world.

stanza. Both metaphors reflect the poem's main theme of Sow (Line 9) - "Sow" means to plant seeds.

communication between both human beings and between

Waterbutt (Line 10) - A "waterbutt" is a British term for an

people and the natural world. The first metaphor begins in line

outdoor container used for storing liquid (especially rainwater).

11. From the speaker's perspective, the acquaintance's act of

writing letters is akin to "pouring air and light into an envelope."

In other words, these letters about the natural world and an FORM, METER, & RHYME

outdoor lifestyle are so rich and evocative to the speaker, who

spends most of their time indoors, that they seem filled with FORM

the very elements they discuss. These letters provide the

"Letters from Yorkshire" is broken into five, three-line stanzas.

speaker with a glimpse into a completely different lifestyle, one

This form is steady throughout, creating a sense of measured

full of "air and light" that the speaker does not experience much

pacing. At the same time, the frequent enjambment between

thanks to their time spent working on a computer.

stanzas suggests that the speaker isn't all that interested in

Later on in that final stanza, the speaker describes how they making their thoughts adhere strictly to the poetic form in

©2020 LitCharts LLC v.007 www.LitCharts.com Page 7

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com

front of them. Altogether, the poem is both structured and ... because you dig and sow

sow?

free-flowing, declarative and contemplative. You wouldn’t say soso, breaking ice on a waterbutt,

The stanzas seem to track the progression of the speaker's clearing a path through snow

snow.

thoughts. In the first stanza, the speaker opens with peaceful

descriptions of the natural world, seeming to envy their Interestingly, this is a description of the farmer's likely

penpal's ability to spend time outdoors. In the next two stanzas, objections to the speaker's characterization of farm life. Here,

the speaker clarifies the difference between the penpal's life the poem lays out the more difficult aspects of the penpal's

and their own, as well as wonders whether or not their life is work, yet it's also one of the only moments in the poem with

less "real" because it involves being inside most of the time, any rhyme. Perhaps the speaker is attempting to add some

away from nature. In the fourth stanza, the speaker sonic beauty even to these objections. Or perhaps the repeated

acknowledges the reality that working outdoors may not be /o/ sound here is meant to feel forced or rehashed, like this is

pleasant all the time, before returning, in the fifth stanza, to some argument the speaker has heard many times before from

their affection for news of the natural world via "air and light" in the farmer.

an envelope.

METER SPEAKER

"Letters from Yorkshire" does not have a consistent,

The speaker of this poem is the recipient of the so-called

overarching meter

meter. Instead, it is written in free vverse

erse. This adds

"Letters from Yorkshire," which originate from a penpal who

to its natural, free-flowing and reflective tone. There are still

primarily works outdoors. From the poem, readers know that

some interesting metrical moments, however.

the speaker feeds "words onto a blank screen," and spends

For example, in the first line, the two activities mention follow most of their day sitting at the computer. This suggests that the

the exact same pattern of stresses, adding a sense of rhythm to speaker is probably a journalist or works in news in some way.

the line and emphasizing that these are both equally important It's also clear that the speaker feels somewhat isolated and

parts of the farmer's routine: disconnected from the natural world.

The driving force behind this poem, arguably, is the question

dig

digging his gar

garden

that appears in line 9: "Is your life more real because you dig

plant

planting pota

tatoes

and sow?" The speaker doubts that their life could be "more

real" than one that involves the natural world, and feels

As is also clear from this example, the poem makes frequent use

compelled to express a great appreciation and longing for that

of caesur

caesuraa to add a sense of deliberate rhythm and pacing to its

world throughout the poem. By the poem's end, even after the

lines in the absence of a strict meter. For instance, notice how

speaker acknowledges that working outdoors comes with its

the opening line, "In February, digging his garden, planting

own set of challenges, they deem the natural world as

potatoes," pauses at a regular interval to give equal weight to

ultimately fulfilling. Each letter they receive from their penpal is

each part of the penpal's outdoor life. This same rhythm is

full of "air and light," a suggestion that even basic news of the

echoed in line 6, which reads: "You out there, in the cold, seeing

outdoors is enough to sustain their life.

the seasons / turning ..." All of these caesuras appear within

descriptions of the penpal's farm life. The sonic effect of a

caesura is to slow down the reading experience of a set of SETTING

words or lines, and perhaps the slowing of descriptions of the

penpal's life reflects the slower pace of an outdoor, computer- The poem contains several different physical spaces. Most

free world. prominently, it consists of "that other world," which is the world

of the outdoors that is the object of the speaker's fascination.

RHYME SCHEME The speaker's penpal is seen "digging his garden, planting

"Letters from Yorkshire" does not have a consistent, potatoes," while "the first lapwings return." The poem also

overarching rhyme scheme. Instead, it is told in natural, free- mentions the speaker's indoor world, which involves sitting at a

flowing prose that reflects the speaker's contemplative tone. computer, "feeding words into a blank screen." In the final lines,

That said, it does make use of assonance to string similar vowel both the speaker and their penpal watch "the same news in

sounds together throughout the poem and add a sense of different houses," and continue to "tap out messages" to each

musicality. Take, for example, the long /ee/ sounds in "see

eeing the other via letter. In other words, they're both home watching TV

sea

easons." and writing to each other. Ultimately, the way "Letters from

There are also some subtle moments of internal rh

rhyme

yme, most Yorkshire" navigates between indoor and outdoor spaces

apparent in lines 9-11: allows it to maintain a realistic perception of both while

©2020 LitCharts LLC v.007 www.LitCharts.com Page 8

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com

highlighting how important nature can seem to someone living communicate, suggesting a hesitancy to fully engage with the

constantly in front of their computer. digital world.

CONTEXT MORE RESOUR

RESOURCES

CES

LITERARY CONTEXT EXTERNAL RESOURCES

Dooley's poem might best be thought of as falling into the • Yorkshire Farms Photogr

Photograph

aph — This photo shows the kind

current tradition of ecopoetry

ecopoetry. Rather than simply denoting of rural lifestyle made possible in Yorkshire, England, that

poems about nature, ecopoetry describes writing that relates the speaker of Dooley's poem envies. The accompanying

to the natural world in a deeper, more meaningful way. Often, photo gallery shows other photos from similar regions in

ecopoems will direct readers' attention to endangered or England and the United Kingdom.

unprotected parts of the planet, or perhaps use nature as a (https:/

(https://www

/www.trek

.trekearth.com/gallery

earth.com/gallery/Europe/

/Europe/

vehicle for communicating a particular emotion, such as love or United_Kingdom/England/North_Y

United_Kingdom/England/North_Yorkshire/L

orkshire/Lealholm/

ealholm/

loss. Other ecopoems focus on the way nature interacts with photo414349.htm)

the modern, technology-driven world, and it is this area that • Maur

Mauraa Doole

Dooley's

y's Life Story — The British Council's website

Maura Dooley's "Letters from Yorkshire" most easily fits in. offers biographical information about Dooley and her

After all, the poem is about someone who finds the natural poetry. (https:/

(https://liter

/literature.britishcouncil.org/writer/

ature.britishcouncil.org/writer/

world so fulfilling in comparison to their modern lifestyle that maur

maura-doole

a-dooley)

y)

even their penpal's epistolary descriptions of it seem full of "air

and light." • Doole

Dooley's

y's Fa

Favvorite P

Poets

oets — A transcription of a

short interview with Dooley from the Forward Arts

Other poets that have contributed to ecopoetry include Mary Foundation, in which she discusses how she became

Oliver, Gary Snyder, Forrest Gander, and perhaps most interested in poetry as well as the other poets she most

famously, W.S. Merwin. Interestingly, Merwin is famous for not admires. (http:/

(http://www

/www.forwardartsfoundation.org/wp-

.forwardartsfoundation.org/wp-

using punctuation in his poetry, a formal decision that could content/uploads/Maur

content/uploads/Maura-Doolea-Dooley-F

y-Forward-Prizes-

orward-Prizes-

suggest a willingness to let his natural imagery flow Interview

Interview.pdf)

.pdf)

unrestricted from the regulations of grammar, allowing the

reader to focus more on the images themselves. • Maur

Mauraa Doole

Dooleyy Out LLoud

oud — A YouTube video showing

Maura Dooley reading her poetry in England in 2007.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT (https:/

(https://www

/www..youtube.com/watch?v=8wfxNY4Xre4)

This poem was published in the year 2000. Computers and the

internet had both been around for quite a while at the time of

the poem's composition, and were becoming more and more a

HOW T

TO

O CITE

part of regular people's everyday lives. People could

communicate via email, get the news online, and talk to MLA

strangers in chatrooms. On the one hand, then, technology Kneisley, John. "Letters from Yorkshire." LitCharts. LitCharts LLC, 1

seemed to be having a positive affect on people's lives by Aug 2019. Web. 22 Apr 2020.

increasing productivity and allowing people to stay in touch like

never before. CHICAGO MANUAL

At the same time, people worried about over-reliance on Kneisley, John. "Letters from Yorkshire." LitCharts LLC, August 1,

computers. Technological innovations led to increasingly 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2020. https://www.litcharts.com/

sedentary lifestyles devoid of any significant interaction with poetry/maura-dooley/letters-from-yorkshire.

the natural world (especially when compared to the time before

electricity itself existed). Notably, the characters in the

poem—or, at least, the penpal—use real paper and envelopes to

©2020 LitCharts LLC v.007 www.LitCharts.com Page 9

You might also like

- LitCharts RoomsDocument10 pagesLitCharts RoomsElisee DjambaNo ratings yet

- Johnna Adams - GidionsknotDocument14 pagesJohnna Adams - GidionsknotNeal Hebert100% (4)

- Lorca, Federico Garcia - Lorca-BlackburnDocument98 pagesLorca, Federico Garcia - Lorca-Blackburnphilipglass86% (7)

- LitCharts: Nearing Forty by Derek WalcottDocument12 pagesLitCharts: Nearing Forty by Derek WalcottreyaNo ratings yet

- Critical Quotes For Goodison's Selected PoemsDocument15 pagesCritical Quotes For Goodison's Selected PoemsReina HeeramanNo ratings yet

- Pessimistic Worldview and Existential Nihilism in Philip Larkin's Poetry-TCLDocument12 pagesPessimistic Worldview and Existential Nihilism in Philip Larkin's Poetry-TCLJyotsna singh100% (1)

- Cavafy and The SeaDocument15 pagesCavafy and The SeaAphro GNo ratings yet

- Ways With Words PDFDocument10 pagesWays With Words PDFFavaz Mk100% (1)

- Lesson Plan Figures of SpeechDocument7 pagesLesson Plan Figures of SpeechLangging AgueloNo ratings yet

- Duffy - Notes by ThemeDocument7 pagesDuffy - Notes by ThemeGeorge ConnorNo ratings yet

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge Biographia LiterariaDocument26 pagesSamuel Taylor Coleridge Biographia LiterariaMuneeb Tahir SaleemiNo ratings yet

- Early Welsh Gnomic and Nature P - Nicolas Jacobs PDFDocument185 pagesEarly Welsh Gnomic and Nature P - Nicolas Jacobs PDFpbhansen100% (1)

- Art Appreciation ActivitiesDocument6 pagesArt Appreciation ActivitiesAngelica Malacay Revil83% (6)

- Greta Hawes - Myths On The Map - The Storied Landscapes of Ancient Greece-Oxford University Press (2017)Document351 pagesGreta Hawes - Myths On The Map - The Storied Landscapes of Ancient Greece-Oxford University Press (2017)윤순봉No ratings yet

- Letters From Yorkshire - Maura DooleyDocument5 pagesLetters From Yorkshire - Maura DooleydiscussndlNo ratings yet

- University of Northern Colorado Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To ConfluenciaDocument16 pagesUniversity of Northern Colorado Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To ConfluenciaJosué Durán HNo ratings yet

- Commentary On All Souls' MorningDocument3 pagesCommentary On All Souls' Morningmohamud_idilNo ratings yet

- Kang Paper #1Document8 pagesKang Paper #1Peter KangNo ratings yet

- In Your Mind by Carol Ann DuffyDocument3 pagesIn Your Mind by Carol Ann DuffyEdwardNo ratings yet

- Learning Guide: EnglishDocument5 pagesLearning Guide: EnglishMary Kristine Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Grain of SandDocument7 pagesGrain of SandParth RanaNo ratings yet

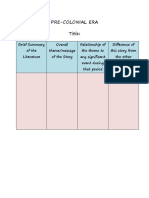

- Pre-Colonial Era TitleDocument6 pagesPre-Colonial Era Titlericky pawigNo ratings yet

- AtmosphereDocument5 pagesAtmospheredaniel,jr BALDOZNo ratings yet

- Private Ground: Jennifer YarosDocument8 pagesPrivate Ground: Jennifer YarosAlessia SEVEKENo ratings yet

- The Black Map-A New Criticism AnalysisDocument6 pagesThe Black Map-A New Criticism AnalysisxiruomaoNo ratings yet

- LitCharts Where I Come FromDocument9 pagesLitCharts Where I Come FromJudes EditsNo ratings yet

- Sukumar Rays Satpatra A Dramatic MonologDocument5 pagesSukumar Rays Satpatra A Dramatic MonologSagnik KoleyNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1696407047Document2 pagesAssignment 1696407047shashwatthegamerytNo ratings yet

- Eden Rock LitChartDocument11 pagesEden Rock LitCharth1110715No ratings yet

- After+Apple PickingDocument63 pagesAfter+Apple PickingMaría FoltrauerNo ratings yet

- Hawthorne ThescarletletterDocument250 pagesHawthorne ThescarletletterМихаица Николае ДинуNo ratings yet

- Kotobati - The Scarlet LetterDocument250 pagesKotobati - The Scarlet Letterlycee princeNo ratings yet

- Hawthorne The Scarlet LetterDocument250 pagesHawthorne The Scarlet LetterCole RobinsonNo ratings yet

- Robert Browning's My Last DuchessDocument11 pagesRobert Browning's My Last DuchessDundhuvika DebbarmaNo ratings yet

- Definition of ImageryDocument4 pagesDefinition of Imagerychris dungoNo ratings yet

- Wrongs, and Saramago's And: NamesDocument26 pagesWrongs, and Saramago's And: NamesAnastasiaNo ratings yet

- Elizabeth Winifred Brewster,: CanadianDocument4 pagesElizabeth Winifred Brewster,: CanadianVinnoDarmawanNo ratings yet

- Language and The Poet in Michael Ondaatje's "Early Morning, Kingston To Gananoque" (Aug. 2002 Scanned)Document4 pagesLanguage and The Poet in Michael Ondaatje's "Early Morning, Kingston To Gananoque" (Aug. 2002 Scanned)Patrick McEvoy-HalstonNo ratings yet

- Collective Emphasis On The Symbolic Uncertainties of The Life of The 21 Century ManDocument3 pagesCollective Emphasis On The Symbolic Uncertainties of The Life of The 21 Century ManMa. Angel SilverioNo ratings yet

- On The Grasshopper and The Cricket. Lesson - AnthologyDocument20 pagesOn The Grasshopper and The Cricket. Lesson - Anthologyfoofabasha1984No ratings yet

- On To AutumnDocument32 pagesOn To AutumnShreya RoyNo ratings yet

- Close Language Analysis EE CummingsDocument2 pagesClose Language Analysis EE CummingsJames Rodgers100% (1)

- The Darkling Thrush - Line by Line Translation From LitchartsDocument6 pagesThe Darkling Thrush - Line by Line Translation From LitchartsanuhyaextraNo ratings yet

- Symbolism in After Apple PickingDocument5 pagesSymbolism in After Apple PickingÑáZníñ NaZãbNo ratings yet

- After Apple PickingDocument7 pagesAfter Apple PickingAsifa IqbalNo ratings yet

- Reagan Logan Poetry Analysis (Q1) Prep.Document2 pagesReagan Logan Poetry Analysis (Q1) Prep.Levi LoganNo ratings yet

- 01 Sunset Song Revision GuideDocument9 pages01 Sunset Song Revision GuidenwintonNo ratings yet

- GROBE-Breath Poem Confessional-2012Document17 pagesGROBE-Breath Poem Confessional-2012Honglan HuangNo ratings yet

- Essay 2Document5 pagesEssay 2Sibi ChakaravartyNo ratings yet

- Summary of All PoemsDocument8 pagesSummary of All PoemsSrishti MalhotraNo ratings yet

- MowingDocument18 pagesMowingNoëllieNo ratings yet

- This Document Is Fully Downloaded. You MayDocument13 pagesThis Document Is Fully Downloaded. You Maylindastar16774No ratings yet

- Naturaleza, Historia y PoeticaDocument2 pagesNaturaleza, Historia y PoeticaGiulia GallinaNo ratings yet

- Thesis For After Apple PickingDocument7 pagesThesis For After Apple Pickinglisafieldswashington100% (2)

- The Character Portrayal of Muriel Spark and Their Unique ProficiencyDocument3 pagesThe Character Portrayal of Muriel Spark and Their Unique ProficiencyIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- SnowdropDocument13 pagesSnowdropsamNo ratings yet

- 07.0 PP 41 62 Tintern AbbeyDocument22 pages07.0 PP 41 62 Tintern AbbeyCatherine Kuang 匡孙咏雪No ratings yet

- Meeting at Night TpcasttDocument4 pagesMeeting at Night Tpcasttapi-417998286No ratings yet

- New Darkling ThrushDocument6 pagesNew Darkling ThrushAsadRawootNo ratings yet

- Group 3 Literary AnalysisDocument21 pagesGroup 3 Literary AnalysisYahBoiMaykelNo ratings yet

- Descriptive Essay FormatDocument1 pageDescriptive Essay FormatShen ShenNo ratings yet

- On Philip Larkins PoetryDocument10 pagesOn Philip Larkins PoetryEman AleemNo ratings yet

- Luath Kilmarnock Edition: Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect: 250th Anniversary EditionFrom EverandLuath Kilmarnock Edition: Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect: 250th Anniversary EditionNo ratings yet

- BrowningDocument3 pagesBrowningKiran AnjumNo ratings yet

- Learning Activity Sheet Teaching and Assessment of Literary Studies - MC Elt 4Document5 pagesLearning Activity Sheet Teaching and Assessment of Literary Studies - MC Elt 4Mabelle Abellano CipresNo ratings yet

- The Coming of Enkidu (Gilgamesh Epic)Document18 pagesThe Coming of Enkidu (Gilgamesh Epic)jackie0403No ratings yet

- Mangalacharan 3Document2 pagesMangalacharan 3hanaNo ratings yet

- What Are The 5 Main Literature GenresDocument3 pagesWhat Are The 5 Main Literature GenresjomaNo ratings yet

- PT-1.1-Comparative-Analysis - CATAPANGB03Document2 pagesPT-1.1-Comparative-Analysis - CATAPANGB03Rein Fiel CatapangNo ratings yet

- MCQS and PYQs On Literary CriticismDocument19 pagesMCQS and PYQs On Literary Criticismabhinavpn17No ratings yet

- Edgar Allan Poe - A DreamDocument1 pageEdgar Allan Poe - A DreamItha Shin ChanchythaNo ratings yet

- Ap18 English Literature q1 PDFDocument12 pagesAp18 English Literature q1 PDFMartin CoscolluelaNo ratings yet

- European Romantic Review: To Cite This Article: David Punter (2012) History of The Gothic: Gothic Literature 1764-1824Document9 pagesEuropean Romantic Review: To Cite This Article: David Punter (2012) History of The Gothic: Gothic Literature 1764-1824Libre Joel IanNo ratings yet

- R7. DesiderataDocument5 pagesR7. DesiderataVarsha ArunNo ratings yet

- 21 ST Century Literature From The PhilipDocument20 pages21 ST Century Literature From The PhilipAl-var A AtibingNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Phenomenal WomanDocument8 pagesResearch Paper Phenomenal WomanafeavbrpdNo ratings yet

- Name: Hajra Zahid A Comparative Analysis of Wordsworth and Mathew ArnoldDocument3 pagesName: Hajra Zahid A Comparative Analysis of Wordsworth and Mathew ArnoldBinte ZahidNo ratings yet

- Week 3Document6 pagesWeek 3Acilla Mae BongoNo ratings yet

- Anti War Literature by SnigdhaDocument31 pagesAnti War Literature by SnigdhaSuhas Sai MasettyNo ratings yet

- GR 7 May MonthhlyDocument6 pagesGR 7 May MonthhlyDinesha LakmaliNo ratings yet

- Literary Devices ThesisDocument8 pagesLiterary Devices Thesisafknbiwol100% (2)

- 3RD PT - 21ST Century LiteratureDocument5 pages3RD PT - 21ST Century LiteratureCristian Paul De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Cold WithinDocument8 pagesCold WithinRinki SahayNo ratings yet

- The Ornate Glass Palace - Popular English Poetry - Subramanian ADocument2 pagesThe Ornate Glass Palace - Popular English Poetry - Subramanian ASubramanian ANo ratings yet

- Greer Thesis PDFDocument408 pagesGreer Thesis PDFpjdfeherNo ratings yet