Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hayek

Uploaded by

Annayah UsmanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hayek

Uploaded by

Annayah UsmanCopyright:

Available Formats

Hayek on Spontaneous Order and Constitutional Design

Author(s): Scott A. Boykin

Source: The Independent Review , Summer 2010, Vol. 15, No. 1 (Summer 2010), pp. 19-34

Published by: Independent Institute

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24562263

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Independent Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

The Independent Review

This content downloaded from

205.164.157.187 on Sun, 12 Mar 2023 14:09:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek on Spontaneous

Order and Constitutional

Design

Scott Α. boykin

to praise the market, reject socialism, and argue that moral traditions are the

Friedrich A.of evolution.

products HayekLess isunderstood

wellis theknown

relationship for

between his

Hayek'suse

idea of the concept of spontaneous order

of spontaneous order and his constitutionalism. His work here differs from the school

of constitutional political economy, which proposes structures to limit governmental

power chosen by self-interested persons (see, for example, Buchanan and Tullock

1962). In Hayek's view, the mechanics of the separation of powers will limit interven

tion in market and cultural competition only where the evolved opinion in a society

regarding justice demands limited government. Deliberate constitutional design can

place opinion in a position to curtail intervention and leave room for competitive social

processes, but constitutional planning is no substitute for evolved beliefs that limit

government's authority. Although constitutional design can facilitate and take advan

tage of spontaneous order, cultural evolution, which is a type of generation of sponta

neous order, ultimately determines the constraints on public power.

Hayek's political thought rests on the concept of spontaneous order: unplanned

social order generated by goal-directed individual action. He uses this concept to

offer accounts of market competition and cultural evolution, and he argues that these

self-organizing social phenomena are useful because they transmit more information

than can be conveyed through conscious design. The concept of spontaneous order is

Scott A. Boykin practices law in Birmingham, Alabama.

The Independent Review, v. 15, ». 1, Summer 2010, ISSN 1086-1653, Copyright© 2010, pp. 19-34.

19

This content downloaded from

205.164.157.187 on Sun, 12 Mar 2023 14:09:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

20 ♦ SCOTT Α. BOYKIN

also the basis of his liberal political theory, in which individual free

value. Hayek's work has received increased attention in recent years,

tional writings have not received much critical notice, which is u

this element of his thought illuminates the relationship he establ

taneous order and conscious design.

He outlines an ideal constitution that features a version of the sep

intended both to grant political primacy to evolved cultural rul

influence of groups that demand state interference with competitiv

For more than two centuries, liberal constitutionalists have champio

of powers as a means of constraining self-interested political activity

freedom, and although Hayek is at one with this tradition on the wo

tion of powers, he also contends that cultural rules that restrict pub

requisite to preserving limited government. Because culture is, in Ha

product of spontaneous evolution, the rules that restrain power a

invisible hand. The visible hand of constitutional design should place

position to govern egoistic political action, so Hayek's separation

nates particular interests to such rules. His scheme suggests that cul

favor limited government because, if they do not, the separation of po

to prevent intrusions on individual liberty. Liberalism and cultural e

closely associated in his political thought; his writings indicate that i

not demand limited government, structural constraints on power will

The Market, Evolution, and Liberalism

Hayek argues that spontaneous order promotes cooperation without c

by enabling individuals to coordinate their actions through the impe

of market prices and cultural rules. Because spontaneous order is

individuals' decisions, it is end independent; that is, it aims toward n

outcome. Instead, it generates abstract signals that provide informat

use in pursuing their aims. Such signals reduce the quantity of concre

individuals must collect to coordinate their plans with those of other

in prices, which convey information concerning the demand for and

and services, or in evolved rules, which give rise to rational expe

conduct, spontaneous order enables individuals to act on inform

explicitly possess (Hayek 1973, 17-39). Because no one can know

determine prices or evolved rules, no one is in a position to plan econ

cultural change using as much information as is transmitted through

tion and cultural evolution. Public officials cannot determine the outcomes of eco

nomic activity without inhibiting the flow of information; a society's cultural traditions

contain elements that cannot be articulated by anyone or productively tinkered with by

government. Hayek rejects "constructivism," which is the assumption that "since man

has himself created the institutions of society and civilization, he must also be able to

THE INDEPENDENT REVIEW

This content downloaded from

205.164.157.187 on Sun, 12 Mar 2023 14:09:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek on Spontaneous Order and constitutional Design ♦ 21

alter them at will so as to satisfy his desires or wishes" (1

economy nor its culture can be effectively planned.

The spontaneous order of the market takes advantage of t

edge" in a society, coordinating the actions of persons w

information (Hayek 1948, 50). Most of the data used in th

the particular circumstances of time and place" that requi

for its efficient use (1948, 80). Market prices condense co

abstract, flexible form that can be rapidly transmitted. The

communication more efficient and puts resources to th

result, individuals are more productive than under any altern

ment (Hayek 1976, 115-20).

The natural selection of cultural rules is another instance

Hayek contends that cultural evolution proceeds through a gr

which rules conducing to productivity spread at the expense

A group that observes better-adapted rules can support a

practices displace other practices as it grows and as mem

adopt these more effective behaviors. Culture is reproduced p

tion because much of the information that the culture's rules contain is "tacit knowl

edge" not readily transmissible through overt instruction (Hayek 1979, 153-69).

Cultural evolution tends toward increasing group size, and its zenith is the "extended

order": a system of cooperative interaction that in its scope and complexity far exceeds

the capabilities of conscious direction (Hayek 1988, 6).

Although the market process and cultural evolution are distinct processes, they

are closely related. Hayek expects rules that support market practices to supersede

those that underpin premarket arrangements because intergroup competition in the

production of wealth drives evolution forward. Hence, cultural practices that pro

mote the division of labor, contract, and private property should emerge through

group competition. The emergence of private property and competitive markets

brings about the establishment and gradual enlargement of the individual liberty that

characterizes life in the extended order. Traditions that support personal freedom are

thus the products of cultural evolution (Hayek 1988, 29-47).

The legal framework appropriate to the extended order conforms to the "rule of

law," which Hayek describes as a "meta-legal doctrine or a political ideal" (1960,

206). The rule of law requires that laws take the form of general rules that are

universally applied (1960, 208-9). General rules, according to Hayek, can establish a

competitive arena in which individuals may pursue their private aims. Commands or

policies that deviate from the form of general rules are necessary to determine the

outcomes of economic activity, so socialist planning and market intervention intended

to decide the results of competition will violate the rule of law (Hayek 1976,123-29).

The rule of law is central to Hayek's liberalism. The state's power is limited when it

can apply only general rules to individuals and has no authority to issue commands to

private persons. Within the bounds of general rules, individuals can choose and pursue

volume 15, Number 1, Summer2010

This content downloaded from

205.164.157.187 on Sun, 12 Mar 2023 14:09:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

22 ♦ SCOTT Α. BOYKIN

their private goals and possess a liberty limited only by others'

Hayek, liberal equality means equality before the law, not material equ

recognizes no standard of justice determined by the pattern of in

Where force and fraud are prohibited, property is protected, and cont

liberal justice is served. Liberalism, then, demands limited gove

restricts the power of popular majorities in a democracy (Hayek 1

Interest-Group Politics and Spontaneous Or

Hayek sees interest-group politics as a threat to liberal government a

order. When a democratic institution is concerned with the politi

economic benefits to groups, group advantage becomes the basis

the rule of law is likely to be violated. Political parties become co

groups, and these alliances provide the legislative majorities by w

gain privileges that impose costs on the public (Hayek 1979, 5-19

interferes with market competition on behalf of favored groups, spo

destroyed. Intervention distorts prices and misallocates resources, an

precipitate further state direction to coordinate economic activ

Because economic competition among groups is the mechanism of

extensive state control of the economy can lead to the desuetude and

the evolved practices that gave rise to the extended order and tha

population (1979, 170-73). The level of living and even the v

substantial segment of that population may eventually be thre

control replaces the market (Hayek 1988, 7).

Hayek argues that a legislature empowered to violate the rule

exploitative benefits to interest groups. If the institution that make

distribute favors through the design of policy, it will abuse its lawma

serving special interests. He contends that contemporary legislative i

become preoccupied with policy formulation to the detriment of

necessary for spontaneous order because framing policy offers leg

ties to acquire political support by awarding privileges to interest

power to design policy and the power to enact general rules are

legislative body, the former activity will gain the upper hand, and u

ernment will be the result (Hayek 1979,15-25).

Hayek's Ideal Constitution

Opinion over Politics

Hayek presents an "ideal constitution" to show how the separation

most effectively limit the influence of interest groups (1979, 10

rationale of his proposal bears a resemblance to David Hume's in

The Independent Review

This content downloaded from

205.164.157.187 on Sun, 12 Mar 2023 14:09:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek on Spontaneous Order and Constitutional Design ♦ 23

Commonwealth," which is significant because Hayek invokes

own evolutionism and anticonstructivism (Hayek 1967).

suggest that any country with a firmly established const

replace its constitution by a new one drawn up on the lin

This cautionary note follows from his anticonstructivism

"[A]n established government has an infinite advantage, by t

its being established; the bulk of mankind being governed by

and never attributing authority to any thing that has no

antiquity" (1985, 512).

Hayek proposes that his constitutional model serves to illu

between general rules and commands and indicates the for

serving a free society (1979, 107-9). This proposal is main

although it is plain that Hayek, like Hume, intends to indicat

tions might be improved "by such gende alterations and inno

too great a disturbance to society" (Hume 1985, 514).1 Bu

practical applications for his plan, and in doing so he is fo

Hume argues that part of the value of developing an idea

opportunity might be afforded of reducing the theory to pr

tion of some old government, or by the combination of m

some distant part of the world" (1985, 513). Hayek likew

formed democracies might profit from his scheme as a mean

to place great power in public hands. He also proposes tha

organizations might benefit from his model in constructing

limited functions in an effective manner. His ideal, then, is n

intended as a guide in designing actual political institutions.

Hayek's ideal constitution does not enumerate substant

power: "a constitution is essentially a superstructure erected

of existing conceptions of justice but not to articulate t

existence of a system of rules of just conduct and merely

their regular enforcement" (1979, 38). His constitution's p

formal. It represents the metalegal doctrine of the rule

clause" defines the standards to which all law must conform,

it to accommodate both types of spontaneous order (1979

a fixed set of rules, so it makes room for the evolution o

legislation satisfying the basic clause will be in the form requ

the market. There is a place for design in spontaneous order,

the level of constitution making, the purpose of design is to

support the spontaneous processes of evolution and market co

1. This passage is part of the motto of the chapter in which Hayek presen

105).

Volume 15, number 1, Summer 2010

This content downloaded from

205.164.157.187 on Sun, 12 Mar 2023 14:09:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

24 ♦ SCOTT Α. ΒΟΥΚΙΝ

task, deliberate constitutional design is facially consistent with

taneous social order.

Hayek proposes that the distinction between laws and commands be embodied

in a bicameral legislature. An upper chamber, the "Legislative Assembly," enacts the

law that regulates individual conduct and the scope of government, and a lower

chamber, the "Governmental Assembly," formulates public policy. The Legislative

Assembly frames rules of conduct that must meet the rule-of-law standard. These

rules govern behavior and specify individual rights. In establishing rights, laws

enacted by the Legislative Assembly circumscribe the Governmental Assembly's

authority over public policy. Hayek sees this arrangement as a twist on the traditional

doctrine of the separation of powers that would more effectively limit the growth of

government than does the doctrine found, for instance, in the U.S. Constitution

(1979,109-20).

Hayek argues that the Legislative Assembly should be elected in such a way that

its membership reflects traditional ideas of just conduct and the Governmental

Assembly's mode of election should make it responsive to the preferences of diverse

social groups. He wants to exclude professional politicians from the Legislative

Assembly, so he bars from membership those individuals who have been in political

parties and the Governmental Assembly (1979, 111-14). He suggests that members

of the Legislative Assembly should be "elected at a relatively mature age for fairly long

periods, such as fifteen years, so that they would not have to be concerned about

being re-elected" (1979, 113).2 Voters can elect representatives to the Legislative

Assembly only once and only when the voters themselves too have reached a mature

age. Hayek adds that "only people who have already proved themselves in the

ordinary business of life" should be members of the Legislative Assembly, and

he remarks that "it could be expected that such a position would come to be regarded

by each age class as a sort of prize to be awarded to the most highly respected of their

contemporaries" (1979, 113-14). He clearly hopes that members of the Legislative

Assembly will be steeped in market practices and the cultural rules of the extended

order, but in any case middle-age voters are to elect their peers to the Legislative

Assembly to represent their generation's conceptions of justice.

Hayek proposes the establishment of "political clubs" to aid the recruitment of

candidates for election to the Legislative Assembly. These clubs would be organized

according to age groups, discuss questions of political importance, and be publicly

funded. He views the clubs as educational institutions meant to teach individuals

citizenship, leadership, and the predominant values of their peers. They would thus

provide a learning environment for future members of the Legislative Assembly as

well as their electors (1979,117-19).

Hayek's scheme also features a "Constitutional Court" with the power of judi

cial review. It can invalidate policies of the Governmental Assembly that violate rules

2. Hayek considers forty-five years of age appropriate.

The Independent Review

This content downloaded from

205.164.157.187 on Sun, 12 Mar 2023 14:09:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek on Spontaneous Order and Constitutional design ♦ 25

enacted by the Legislative Assembly, and it can nullify ac

contravene the basic clause of the constitution. Members o

by a body composed of retired members of the Legislativ

Because the court is selected by retired members of the Legis

are likely to change more slowly than those of the upper cha

the long run, the court's rulings will change in accordance

represented in the Legislative Assembly.

A Mixed Constitution

Hayek's constitution is, in a loose sense, a mixed constitution. He suggests that "in

choosing somebody most likely to look after their particular interests effectively and

in choosing persons whom they can trust to uphold justice impartially the people

would probably elect very different persons: effectiveness in the first kind of task

demands qualities very different from the probity, wisdom, and judgment that are of

prime importance in the second" (1979,112).

Members of the Legislative Assembly should not be professional politicians, but

rather individuals who have been elected for the qualities they have demonstrated in the

conduct of their private lives. Hayek argues that the upper chamber's mode of election,

in which middle-age voters select "'the most successful member of the class,' would

come nearer to producing the ideal of the political theorists, a senate of the wise, than

any system yet tried" (1978,103). The upper chamber is to comprise a natural aristoc

racy. His mixed constitution differs from the traditional formula, which balances social

classes. Instead, it balances the desires of organized interest groups, which attempt to

influence the lower chamber, against the public interest in justice, which is represented

in the upper chamber. In his mixed constitution, conceptions of justice expressed in law

by the upper chamber constrain the pursuit of personal interests in the lower. This

arrangement reflects a "hierarchy of rules" in which principles of justice have priority.

Hayek sees constitutionalism as the establishment of such a hierarchy (1960,178).

The separation of powers does not work without checks and balances because

one element of government will tend to dominate the whole. Mixed government

is one means of establishing the necessary checks (Gwyn 1965, 24-27; Vile 1967,

119-41). Hayek considers the public interest to consist in the application of a

society's system of evolved rules and the additional legislative rules enacted to support

spontaneous order (1976, 1-30). The procedures for electing the Legislative Assem

bly aim to ensure that those who delimit the state's authority are imbued with

traditional conceptions of justice. Members of the upper chamber are to be individ

uals who have most internalized their society's traditional rules, which represent the

public interest. The possession of this quality is what makes them a natural aristocracy,

and in this qualified sense Hayek's constitution is a mixed one.

Norman Barry (1979,190-94) and Ronald Hamowy (1982) have quite reason

ably brought into question the feasibility of Hayek's functional differentiation of the

Volume 15, Number 1, Summer 2010

This content downloaded from

205.164.157.187 on Sun, 12 Mar 2023 14:09:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

26 ♦ SCOTT Α. BOYKIN

two chambers, but the practicability of the constitution's structu

interesting as the sociological reasoning behind it. The Legislative

above politics. Members have no party, must never have had on

fifteen-year terms that they begin at a mature age. They may be

through the participatory apparatus of clubs and are to be tho

admired by their peers. They are Hayek's natural aristocracy: an aris

tional virtue. Their preeminence in the legislative process is in

interest-group pressure for measures contrary to the public good. Th

is likely to be composed of professional politicians who must con

tion and therefore pander to special interests, so here the struggle f

advantage takes place. Whereas the upper chamber represents traditi

justice, and its mode of election slows the pace of change, the low

sents special and party interests and is elected in a manner mean

responsive to popular demands. Special-interest politics in the lower

within the bounds of justice by the upper chamber's natural aristocr

Opinion and the Separation of Powers

Hayek intends to show how the separation of powers can best l

control that government exercises over individual conduct, leavin

the spontaneous social processes of the market and cultural evolution

can be restrained by principles of justice that are the products of cu

and Hayek's ideal constitution is designed to place evolved belie

limits of public authority in a position to control policymaking.

placing at the head of the legislative process individuals recognize

best exemplifying their generation's conceptions of justice. The prin

government are thus grounded in culture, but it is clear that the ext

powers of government are restricted depends on how demanding tho

Cultural evolution generates a people's "sense of justice," whic

inant opinion in a society concerning what kinds of conduct are

contrasts "opinion," which reflects this sense of justice, with "will,"

the means chosen to realize particular states of affairs. Because t

contains abstract ideas about right and wrong conduct, opinion

general rules. Opinion constrains the exercise of will. In private

narrows the range of acceptable means for pursuing goals; in publ

the scope of state action. The form of opinion, or general rules

restraint. Another limitation issues from the substance of opinion

tradict the society's sense of justice will be eliminated under a well-o

tion (Hayek 1978, 81-94). The political function of opinion is

structure of Hayek's bicameral legislature in that the upper chamber

ion and the lower chamber represents will (1979, 104). The uppe

mines what types of private and state actions are acceptable, and

The independent review

This content downloaded from

205.164.157.187 on Sun, 12 Mar 2023 14:09:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek on Spontaneous Order and Constitutional design ♦ 27

decides what goals shall be pursued subject to these rest

limited by the opinion on justice found in the upper cham

Law, Opinion, and Liberty

Critics have interpreted Hayek as arguing that the rule of la

the individual rights necessary to liberalism. The consensus a

this argument is a weakness of his political theory because gen

individual's choices as to create a nonliheral society (Gray

however, express reservations concerning the efficacy of gen

personal freedom. He admits that "even rules which are perfe

might still be serious and unnecessary restrictions of individu

to fortify the rule of law by adding that only "actions toward

to regulation (1973,101). He recognizes that there is no ob

ing which actions are "other regarding," and he concedes tha

guarantee of liberal law. He suggests, for example, that if

society will be punished for the sins of a few, sin becomes an

(1973, 101). The classes of actions that come within the

culturally defined, and culture may produce distinctly illibera

The range of actions considered other regarding must

individual freedom, and this condition extends to econom

"The law evidently cannot prohibit all actions which may

harm knowingly caused to others is even essential for the pr

ous order: the law does not prohibit the setting up of a ne

done in the expectation that it will lead to the failure of

market competition and sin are culturally defined as other-r

qualified rule of law can permit illiberal intrusions on individ

his critics' assertions, however, he does not believe that the r

of liberal rights, but rather that although "[this principle] le

enforcement of oppressive rules . .. [it] seems to be as effect

ing coercion as mankind has yet discovered" (1967, 350).

He sees the rule of law as a necessary but not a sufficient

society. Liberalism requires the substantive condition of a

well as the formal condition of the rule of law. Hayek's ideal

to give cultural rules primacy in a society's political affair

justice must contain specific sentiments to preserve liber

argues that

liberty, to work well, requires not merely the existence of strong moral

convictions but also the acceptance of particular moral views. By this I do

not mean that within certain limits utilitarian considerations will contribute

to alter moral views on particular issues. ... I am concerned rather with

Volume 15, Number 1, Summer 2010

This content downloaded from

205.164.157.187 on Sun, 12 Mar 2023 14:09:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

28 ♦ SCOTT Α. ΒΟΥΚΙΝ

some more general conceptions which seem to me an essential c

free society and without which it cannot survive. The two cruc

to me the belief in individual responsibility and the approval as

arrangement by which material rewards are made to correspond

which a person's particular services have to his fellows. (1973

liberalism relies on these beliefs' being widely held; competition an

presuppose individual responsibility, and the acceptance of m

is necessary to avert demands for intervention to redistribute

Madison, Hayek argues that social diversity presents a useful barrie

of majority support for oppressive measures, but he also h

cultural consensus that restricts the state's authority is essentia

(1979,17-19). Constitutional design and political tradition are im

the absence of structural or traditional restraints on the exercis

bargaining will generate intervention. For Hayek, however, libe

only certain political practices, but also a cultural inclination towar

A cultural disposition favoring liberalism will also include suppo

law. Public authority can be limited by "the existence of a stat

commands implicit obedience to the legislator so long as he com

general rule, but refuses obedience when he orders particular

Opinion, however, can also support unlimited government. "Tha

opinion in this sense is no less true of the powers of an absolute di

any other authority. As dictators themselves have known best at all

powerful dictatorship crumbles if the support of opinion is withdr

As Hume, whom Hayek is clearly following here, stated, it i

that government is founded; and this maxim extends to the mo

military governments, as well as the most free and most popul

means that coercion is not sufficient to control an uncooperativ

nitely, so a supportive opinion is necessary for any regime's long-t

follows Hume this far, but he goes beyond Hume by assigning a

role to opinion. Hayek is concerned not only with the sources of po

also with the means of preserving liberalism. The function of his c

chamber is to articulate cultural rules and defend the rule of law

which it limits government turns on the opinion it represents. In H

opinion is requisite to liberal government.

Hayek's ideal constitution illustrates the significance of opinion

Assembly and Constitutional Court are responsible for defining

authority. The Legislative Assembly is an elective institution, and i

appoint the court. Hayek recognizes that "judicial review is not

to change," and his plan ensures that each generation's view of justi

be reflected in both the upper chamber and the court, so the q

these bodies enact or uphold will depend on the opinion they r

THE INDEPENDENT REVIEW

This content downloaded from

205.164.157.187 on Sun, 12 Mar 2023 14:09:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek on Spontaneous Order and constitutional design ♦ 29

If opinion does not demand that legislation conform to the r

wants oppressive general rules, nothing can preserve liber

the lower chamber, interest groups and electoral competi

sure for market intervention and deprivations of liberty, so

state power hangs on the opinion represented in the Leg

Constitutional Court.

The rule of law and constitutional practice or structure are necessary but not

jointly sufficient conditions for a liberal politics. A body of opinion that demands

limited government is an additional necessary condition for the persistence of liberal

ism over the long run. Liberalism thus has both formal and substantive requirements,

and in the absence of either, it will falter.

Illustrations and Some Difficulties

Hayek does not mean to offer his ideal as a replacement for all constitutions; if

opinion supports a nonideal constitution that effectively limits political power, there

is no reason to replace it. He does, however, suggest two practical applications for

which his constitution might be employed: newly formed democracies and interna

tional political institutions. The difficulties these applications present stem from the

importance Hayek places on a liberal sense of justice. In either case, a consensus

favoring liberal political principles is necessary if his plan is to be applied successfully.

Hayek's anticonstructivism leads to the conclusion that there is a disconcerting

unpredictability in the prospects for liberalism because liberalism depends on a partic

ular cultural inclination whose existence no one can control.

New Democracies

Hayek suggests that a new democracy "without a tradition even remotely similar to

the ideal of the Rule of Law" might profit from using his scheme as a guide in

constitutional design (1979,108). A basic clause that explicitly states the rule-of-law

standard is essential here because "the particular institutions which for a time worked

tolerably well in the West presuppose the tacit acceptance of certain other principles

which were in some measure observed there but which, where they are not yet

recognized, must be made as much a part of the written constitution as the rest"

(1979,108).

It is arguable that this proposition conflicts with Hayek's anticonstructivism.

One might wish that a new democracy observe the rule of law, but if the people do

not believe in the value of a Hayekian basic clause, that clause will be a dead letter

3. The long run is Hayek's definite perspective. An abiding concern with the long-term effects of moral

and political practices forms the background of his thought. See his disdainful words on John Maynard

Keynes's remark that "in the long run we are all dead" in Hayek 1988, 57.

Volume 15, Number 1, Summer 2010

This content downloaded from

205.164.157.187 on Sun, 12 Mar 2023 14:09:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

30 ♦ SCOTT Α. BOYKIN

before long. It would be constructivistic, in his sense, to assume

design will provide what cultural evolution has not.

However, a new democracy's deliberate adoption of the rul

run counter to Hayek's evolutionary theory, which holds that

transmitted by imitation and that practices proven successful in a

up by others. Hayek expressly contends that developing states

imitate the market rules evolved in the industrialized countri

anticonstructivism leads him to expect that such progressive chang

succeed where it is shaped by the experiences of the society i

Concerning the prospects for German liberal democracy in 1945

there is to be any lasting change in the moral and political do

Germany, it must come from within" (1992, 227-28).

Even if a constitution is imposed from without, the opinion nee

must be available if it is to endure, and opinion will grow in it

constitutional thought is consistent with his anticonstructivism

believe that liberalism can be imposed on a society by a paper const

that liberal political practices depend on culture. His ideal const

opinion that favors the rule of law and limited government to sust

If the new democracy lacks this kind of opinion, contrary views wi

the upper chamber, and liberal safeguards will break down. In t

thing depends on opinion. The political implications of Hayek's

seem relevant as one considers the chances for liberalism in light of

democratization.

International Organizations

Hayek's ideal international political organization would establish collective security

and develop a system of international law prohibiting aggression. It would, in addi

tion, establish global free trade, removing all obstacles to the free movement of labor,

capital, goods, and services. Hayek views free trade as a prerequisite of an effective

global security arrangement because it will create a harmony of interests among states,

thus eliminating economic sources of political conflict. International economic policy

should meet the rule-of-law standard, so policies aimed at promoting the interests of

particular states or groups would be disqualified. Many interventionist policies would

become irrational. States could not, for example, increase the prices of domestic

goods by buying surplus stock. Heavy regulation, moreover, would place domestic

producers at a disadvantage in international competition, and high taxes would

inhibit productive investment and induce a free labor force to move elsewhere (Hayek

1944, 219-40; 1948, 255-72).

Hayek acknowledges that this proposal is a visionary scheme (1944, 237). The

international organization he outlines would work only if most of the world's popu

lation adopted liberal values. National governments would have to open their markets

The Independent Review

This content downloaded from

205.164.157.187 on Sun, 12 Mar 2023 14:09:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek on Spontaneous Order and constitutional design ♦ 31

to universal competition and severely reduce domestic i

policy change would require a supportive opinion to remai

constitution is used as a guide in constructing the internatio

mind, the emergence and persistence of a liberal world s

opinion its institutions represent. In international as well as

ism depends on opinion.

Preserving Liberalism in the Extende

Apart from the challenges presented by Hayek's proposed ap

the reproduction of a liberal sense of justice raises anothe

suggests that even where a liberal tradition exists, spont

undermine the belief system on which liberalism depen

source of intervention in the advanced industrial states is th

of the population of the Western World grow up as memb

and thus as strangers to those rules of the market which

society possible. To them the market economy is largely inco

never practised the rules on which it rests, and its results se

immoral. They often see in it merely an arbitrary struc

sinister power" (1979,165).

His point is reminiscent of Joseph Schumpeter's contenti

destroy itself in spite of its economic accomplishments becau

hostile to the market (1950,121-63). The emergence of lar

development brought on by the needs of the extended or

changes inimical to capitalism. Note that these changes, favo

to employment in large organizations, might be accounted fo

increase group productivity and therefore fit well into H

evolution. In other words, there is no guarantee that a li

reproduce itself, and the market's spontaneous order may

tural changes that threaten to annihilate the market itself.

Government versus Spontaneous Or

The foregoing considerations suggest that under Hayek's a

order is in fact quite fragile and that its persistence depends

This conclusion points toward a more fundamental probl

tional theory: it underscores the notion that the governmen

rules is inconsistent with his theory of social evolution.

The rule of law in Hayek's thought pertains only to the f

the law. The formality of his rule-of-law criteria is necessar

thought because he intends to leave the law open to evolv

tion between spontaneously evolved change and constructi

volume 15, Number 1, Summer

This content downloaded from

205.164.157.187 on Sun, 12 Mar 2023 14:09:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

32 ♦ SCOTT Α. BOYKIN

withstand scrutiny when one attempts to apply the contrast to a spe

or decision (Sandefur 2009). As Timothy Sandefur argues, what m

person as the application of an evolved rule may just as readily ap

constructivist intervention. The production and implementation o

petitive processes that differ entirely from the group competit

Hayek's evolutionary social theory. Group competition in politics

from and in conflict with spontaneous social evolution. This fact is v

to Hayek's constitutional theory because although he seeks to est

tual framework for a liberal political order, his reliance on spon

social rules prevents him from doing so.

Hayek supposes that evolved social rules possess efficiency pr

they have proved effective, with regard to group survival, in compe

rules. But the competitive landscape is changed where governmen

rules. Once government enforcement privileges some rules, the

those rules is such that they have a decisive advantage over altern

the governmentally enforced rules have inherently greater surv

because the cost of violating them makes the alternatives less advant

The sanctions that attend violations of the law are what ultimately s

the law and loyalty to government (Higgs 2005). Thus, the surv

obedience to law and government differ from the benefits that Haye

supposes evolved rules to bestow on the groups that follow them in c

alternative rules. Government enforcement of certain rules neces

group competition on which Hayek's evolutionary social theory de

To illustrate the problem, consider, for example, Sunday Blue

may prohibit a business from selling alcoholic beverages on Sunda

opinion opposes the practice. Persons who would like to sell alcoh

Sundays and their potential patrons are prohibited from testing the

alternative social rules because the governmentally enforced rule pre

doing so. The states in the United States, for example, possess t

which is the power to legislate for the health, welfare, and morals of

is regarded as a "substantial governmental interest."4 The breadth of

is expansive and consistent with Hayek's rule-of-law criteria.

Hayek's legislative bodies are fatally at odds with the idea o

evolved moral rules. He intends the upper chamber to reflect evol

society it governs, which means that it will reflect the views of the

group and give that group the power to enforce its opinion on a

that group effectively governs, and its governance renders the

abstraction and a symbol without substance. Law is made and int

who have the power to do so, and for this reason the law tends t

4. See, for example, Posadas de PR. Assocs. v. Tourism Co., 478 U.S. 328, 341 (19

tion of advertising for casino gambling against First Amendment challenge.

The independent review

This content downloaded from

205.164.157.187 on Sun, 12 Mar 2023 14:09:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek on Spontaneous Order and Constitutional design ♦ 33

power relations in a society (Hasnas 1995). Enforcement

must interfere with the free competition among groups

rules on which Hayek's social theory rests. Government

do not mesh smoothly with Hayek's evolutionary social theo

liberal constitutional scheme to accommodate spontane

mately self-contradictory.

Conclusion

Conscious design, in Hayek's view, can go only a short way toward establishing a

maintaining a liberal constitution. Cultural rules that support economic and civ

liberty are the products of evolution, and the preservation of liberal governme

depends on the political primacy of such rules. Traditions that restrain public power

emerge through economic competition among groups; evolution, rather than co

scious planning, is the source of a liberal culture. Constitutional design can prov

the institutions through which liberal traditions are expressed in law and limit t

state's power, but an ideal constitution is not itself a mouthpiece for political values.

A society's political values are the product of a spontaneous order, and a w

designed constitution accommodates evolving traditions without seeking to shap

cultural change. The only value the ideal constitution contains is a formal one:

rule of law. Beyond this, a constitution should be neutral concerning values. A societ

speaks through its constitution, but the constitution does not speak for society.

There are few certainties in a world driven by competition. Hayek's ideal consti

tution provides a social arena in which individuals and groups may compete, but

accordingly supplies little assurance of the cultural and hence the political future. Hi

constitutional thought suggests that democratic liberalism requires for its persistenc

a cultural disposition favoring limited government. His evolutionary theory presents

the outline of a process through which liberal rules might emerge, but it does n

predict that these rules will persist indefinitely, and he recognizes that liberalism m

contain self-destructive tendencies. These problems underscore that government nec

essarily interferes with the spontaneous social processes on which Hayek's evolut

ary social theory depends. His message is that constitutional mechanics, thoug

important, are inadequate to sustain limited government and that liberalism ul

mately depends on circumstances over which we have no control.

References

Barry, Norman P. 1979. Hayek's Social and. Economic Philosophy. London: MacMillan.

Buchanan, James M., and Gordon Tullock. 1962. The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundat

of Constitutional Democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Gray, John. 1986. Hayek on Liberty. 2d ed. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Volume 15, number l, Summer 2010

This content downloaded from

205.164.157.187 on Sun, 12 Mar 2023 14:09:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

34 ♦ SCOTT Α. BOYKIN

Gwyn, W. Β. 1965. The Meaning of the Separation of Powers. Tulane Studi

New Orleans: Tulane University.

Hamowy, Ronald. The Hayekian Model of Government in an Open Socie

tarian Studies 6 (spring 1982): 137-43.

Hasnas, John. 1995. The Myth of the Rule of Law. Wisconsin Law Revi

Hayek, F. A. 1944. The Road to Serfdom. Chicago: University of Chicago

. 1948. Individualism and Economic Order. Chicago: University of

. 1960. The Constitution of Liberty. Chicago: University of Chicago

. 1967. The Legal and Political Philosophy of David Hume. In Stud

Politics, and Economics, 106-21. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

. 1973. Rules and Order. Vol. 1 of Law, Legislation, and Liberty. C

of Chicago Press.

. 1976. The Mirage of Social Justice. Vol. 2 of Law, Legislation, and

University of Chicago Press.

. 1978. New Studies in Philosophy, Politics, Economics, and the

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

. 1979. The Political Order of a Free People. Vol. 3 of Law, Legisla

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

. 1988. The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism. Vol. 1 of The C

F. A. Hayek. Edited by W. W. Bardey III. Chicago: University of Chica

. 1992. The Fortunes of Liberalism. Vol. 4 of The Collected Works of

by Peter G. Klein. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Higgs, Robert. 2005. Fear: The Foundation of Every Government's Po

Review 10, no. 3 (winter 2005): 447-66.

Hume, David. 1985. Essays: Moral, Political, and Literary. Edited by Eu

napolis, Ind.: Liberty Fund.

Sandefur, Timothy. 2009. Some Problems with Spontaneous Order. Ind

no. 1 (summer 2009): 5-25.

Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1950. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. N

and Row.

Vile, M. J. C. 1967. Constitutionalism and the Separation of Powers. O

University Press.

The Independent Review

This content downloaded from

205.164.157.187 on Sun, 12 Mar 2023 14:09:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Taylorism, Progressivism, and Rule by ExpertsDocument6 pagesTaylorism, Progressivism, and Rule by Expertsglendalough_manNo ratings yet

- Model-16S 181 - 1316.055.200Document53 pagesModel-16S 181 - 1316.055.200Cute little mochiNo ratings yet

- 6a. Cash BudgetDocument4 pages6a. Cash BudgetMadiha JamalNo ratings yet

- Problem Areas in Legal Ethics TamondongDocument5 pagesProblem Areas in Legal Ethics TamondongSirGen EscalladoNo ratings yet

- Tr45 Oaths and SwearingDocument8 pagesTr45 Oaths and SwearingWendell RicardoNo ratings yet

- Law and Spontaneous Order Hayek's Contribution To Legal TheoryDocument18 pagesLaw and Spontaneous Order Hayek's Contribution To Legal TheoryAmmianus MarcellinusNo ratings yet

- SMEs (Students Guide)Document11 pagesSMEs (Students Guide)Erica CaliuagNo ratings yet

- Buchanan (1986) - Cultural Evolution and Institutional ReformDocument13 pagesBuchanan (1986) - Cultural Evolution and Institutional ReformMatej GregarekNo ratings yet

- Industries of Lahore and IsbDocument7 pagesIndustries of Lahore and IsbOmer Nadeem100% (1)

- Markets As PoliticsDocument19 pagesMarkets As PoliticsRodolfo BatistaNo ratings yet

- TEUBNER. Reflexive LawDocument48 pagesTEUBNER. Reflexive LawMercedes BarbieriNo ratings yet

- Teubner. Societal Constitutionalism. SSRN-id3804094Document47 pagesTeubner. Societal Constitutionalism. SSRN-id3804094Jaime C. Ubilla FuenzalidaNo ratings yet

- Office of The Ombudsman - Mayor VergaraDocument9 pagesOffice of The Ombudsman - Mayor Vergaragulp_burp100% (2)

- Hayek On Nomocracy and Teleocracy: A Critical Assessment: Chor-Yung CheungDocument10 pagesHayek On Nomocracy and Teleocracy: A Critical Assessment: Chor-Yung CheungSotiris KNo ratings yet

- Social Justice and The Formal Principle of Freedom, O. Nikolić and I. CvejićDocument15 pagesSocial Justice and The Formal Principle of Freedom, O. Nikolić and I. CvejićOlgaNo ratings yet

- This Essay Critically Examines Friedrich HayekDocument4 pagesThis Essay Critically Examines Friedrich Hayekarathy23010441017No ratings yet

- Judicial Authority and The Struggle For An Indonesian RechtsstaatDocument36 pagesJudicial Authority and The Struggle For An Indonesian Rechtsstaatalicia pandoraNo ratings yet

- Hobbes On Private Property Freedom and OrderDocument14 pagesHobbes On Private Property Freedom and OrderYunus Emre GÜNGÖRNo ratings yet

- Wiley, Royal Institute of International Affairs International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-)Document17 pagesWiley, Royal Institute of International Affairs International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-)ibrahim kurnazNo ratings yet

- James S. Coleman - Constructed Organization. First PrinciplesDocument18 pagesJames S. Coleman - Constructed Organization. First PrinciplesJorgeA GNNo ratings yet

- Bowles RetrospectivesFriedrichHayek 2017Document17 pagesBowles RetrospectivesFriedrichHayek 2017Bernardo PrietoNo ratings yet

- Hayekian Theory of Social JusticeDocument24 pagesHayekian Theory of Social JusticeROHAN SHELKENo ratings yet

- Institutions and Political Networks (II.3.2) CH IDocument13 pagesInstitutions and Political Networks (II.3.2) CH Iimaneamani993No ratings yet

- Bowles and Gintis - SOCIAL CAPITAL AND COMMUNITY GOVERNANCEDocument19 pagesBowles and Gintis - SOCIAL CAPITAL AND COMMUNITY GOVERNANCEbintemporaryNo ratings yet

- Distinction Between Private and Public by ClaireDocument26 pagesDistinction Between Private and Public by Clairechandana MuraliNo ratings yet

- Reinventing Social ContractDocument10 pagesReinventing Social ContractAydogan KutluNo ratings yet

- Sassen RepositioningCitizenshipEmergent 2003Document27 pagesSassen RepositioningCitizenshipEmergent 2003Let VeNo ratings yet

- New German Critique: New German Critique and Duke University Press Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve andDocument13 pagesNew German Critique: New German Critique and Duke University Press Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve andNicolas SantoroNo ratings yet

- Law and Spontaneous Order Hayek's Contribution To Legal TheoryDocument18 pagesLaw and Spontaneous Order Hayek's Contribution To Legal TheoryAmmianus MarcellinusNo ratings yet

- Feldman Public Interest Litigation and Constitutional Theory in Comparative PerspectiveDocument30 pagesFeldman Public Interest Litigation and Constitutional Theory in Comparative PerspectiveKiharanjugunaNo ratings yet

- Vallier HayekianSocialJustice 2019Document11 pagesVallier HayekianSocialJustice 2019arathy23010441017No ratings yet

- SOCI1001A L03 Sociological Perspective IIDocument22 pagesSOCI1001A L03 Sociological Perspective II塵海No ratings yet

- Haunss2020 NewcleavagesintheknowledgesocietyDocument21 pagesHaunss2020 NewcleavagesintheknowledgesocietyGia Bảo TrầnNo ratings yet

- Loughlin ConstitutionalTheoryDocument21 pagesLoughlin ConstitutionalTheoryGaming GodNo ratings yet

- Pol Soc AssignmentDocument6 pagesPol Soc Assignmentziatiger47No ratings yet

- Political Economy of Govt Intervention and Free MarketDocument7 pagesPolitical Economy of Govt Intervention and Free MarketSargun MehramNo ratings yet

- Ryan Sinha CPL 1059Document13 pagesRyan Sinha CPL 1059Ryan SinhaNo ratings yet

- A New Elite Framework For Political Sociology - Elite ParadigmDocument35 pagesA New Elite Framework For Political Sociology - Elite Paradigm3 14No ratings yet

- 2017 JEP (Hayek)Document16 pages2017 JEP (Hayek)Angel T.R 225No ratings yet

- Patriarchy and Historical Materialism, FarrellyDocument22 pagesPatriarchy and Historical Materialism, FarrellymahudNo ratings yet

- Juris EcoDocument22 pagesJuris EcoBello FolakemiNo ratings yet

- Akturk 2002 Market Liberalism and Social Protection Hayek Durkheim Polanyi in Theoretical PerspectiveDocument17 pagesAkturk 2002 Market Liberalism and Social Protection Hayek Durkheim Polanyi in Theoretical PerspectiveSociedade Sem HinoNo ratings yet

- The Dependent City External Influences Upon Local ControlDocument31 pagesThe Dependent City External Influences Upon Local ControlMaria CorreaNo ratings yet

- Fligstein (1996)Document19 pagesFligstein (1996)Kishore KumarNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad The Pakistan Development ReviewDocument23 pagesPakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad The Pakistan Development ReviewAli AwanNo ratings yet

- 10th Week Critical Appraisal - Mariana LemosDocument2 pages10th Week Critical Appraisal - Mariana LemosMarianaNo ratings yet

- AcknowledgementDocument19 pagesAcknowledgementShawn HazlewoodNo ratings yet

- Socialist Investment Dynamic Planning and The Politics of Human NeedDocument13 pagesSocialist Investment Dynamic Planning and The Politics of Human NeedRbe Batu HanNo ratings yet

- Fiscalite de Lentreprise ResumeDocument35 pagesFiscalite de Lentreprise ResumeOmar EljattiouiNo ratings yet

- Freeman ReasonAgreementSocial 1990Document37 pagesFreeman ReasonAgreementSocial 1990yt zhouNo ratings yet

- SIBU620-Week 8-Michael DoyleDocument32 pagesSIBU620-Week 8-Michael DoyleOsman ŞentürkNo ratings yet

- Waligorski Democracy 1990Document26 pagesWaligorski Democracy 1990Oluwasola OlaleyeNo ratings yet

- The Political Economy of Oligarchy and The Reorganization of Power in IndonesiaDocument24 pagesThe Political Economy of Oligarchy and The Reorganization of Power in IndonesiaAhmad ShalahuddinNo ratings yet

- Hayek Critique PDFDocument22 pagesHayek Critique PDFGuilherme HenriqueNo ratings yet

- Hossein, R - Legitimacy, Religion and Nationalism in The Middle East - 1990Document24 pagesHossein, R - Legitimacy, Religion and Nationalism in The Middle East - 1990Tristan Ayela-BeardmoreNo ratings yet

- FLIGSTEIN - Markets As PoliticsDocument19 pagesFLIGSTEIN - Markets As PoliticsdavebsbNo ratings yet

- American Sociological AssociationDocument19 pagesAmerican Sociological AssociationMariane DuarteNo ratings yet

- Peter Gabel and Paul Harris RLSC 11.3Document44 pagesPeter Gabel and Paul Harris RLSC 11.3khizar ahmadNo ratings yet

- La Teoria de La Justicia de John RawlsDocument45 pagesLa Teoria de La Justicia de John RawlsRodrigo Andres Fernandez PolancoNo ratings yet

- Hayek Critique PDFDocument22 pagesHayek Critique PDFGabriel Andreas LFNo ratings yet

- Rethinking IndependenceDocument7 pagesRethinking IndependenceAlex GNo ratings yet

- D EmilioDocument18 pagesD EmilioCHRISTIAN MATUSNo ratings yet

- The Social Consequences of Common Law RulesDocument36 pagesThe Social Consequences of Common Law RulesEliãn ReisNo ratings yet

- Theresa Marie B. Presto Bs Arch 4BDocument5 pagesTheresa Marie B. Presto Bs Arch 4BExia QuinagonNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 140.203.230.47 On Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTCDocument35 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 140.203.230.47 On Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTCPaul LynchNo ratings yet

- Natural Order and Postmodernism in Economic ThoughtDocument24 pagesNatural Order and Postmodernism in Economic ThoughtZdravko JovanovicNo ratings yet

- Self-Interest and Social Order in Classical Liberalism: The Essays of George H. SmithFrom EverandSelf-Interest and Social Order in Classical Liberalism: The Essays of George H. SmithNo ratings yet

- ML.1.Lecture.1Document54 pagesML.1.Lecture.1Annayah UsmanNo ratings yet

- mainDocument12 pagesmainAnnayah UsmanNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6Document6 pagesLecture 6Annayah UsmanNo ratings yet

- ML.1.Lecture.2Document50 pagesML.1.Lecture.2Annayah UsmanNo ratings yet

- lecture16-VCDocument42 pageslecture16-VCAnnayah UsmanNo ratings yet

- ML.1.Lecture.9 (where it actually comes from)Document31 pagesML.1.Lecture.9 (where it actually comes from)Annayah UsmanNo ratings yet

- FAQ_ How do I interpret odds ratios in logistic regression_Document6 pagesFAQ_ How do I interpret odds ratios in logistic regression_Annayah UsmanNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id2794276Document13 pagesSSRN Id2794276Annayah UsmanNo ratings yet

- Lecture 5Document5 pagesLecture 5Annayah UsmanNo ratings yet

- The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: Tapping Potential To Achieve The 2030 Agenda in PakistanDocument25 pagesThe China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: Tapping Potential To Achieve The 2030 Agenda in PakistanAnnayah UsmanNo ratings yet

- Fulltext 1010258Document13 pagesFulltext 1010258Annayah UsmanNo ratings yet

- CPEC and Pakistan: Its Economic Benefits, Energy Security and Regional Trade and Economic IntegrationDocument21 pagesCPEC and Pakistan: Its Economic Benefits, Energy Security and Regional Trade and Economic IntegrationAnnayah UsmanNo ratings yet

- The China Pakistan Economic Corridor CPEC Infrastructure Social Savings Spillovers and Economic Growth in PakistanDocument33 pagesThe China Pakistan Economic Corridor CPEC Infrastructure Social Savings Spillovers and Economic Growth in PakistanAnnayah UsmanNo ratings yet

- The Origins of Indirect Rule in India Hyderabad and The British Imperial Order PDFDocument30 pagesThe Origins of Indirect Rule in India Hyderabad and The British Imperial Order PDFAnnayah UsmanNo ratings yet

- North Vs WilliamsonDocument17 pagesNorth Vs WilliamsonAnnayah UsmanNo ratings yet

- The China Pakistan Economic Corridor and The Growth of TradeDocument28 pagesThe China Pakistan Economic Corridor and The Growth of TradeAnnayah UsmanNo ratings yet

- Business Finance AssignmentDocument14 pagesBusiness Finance AssignmentTatiana Elena CraciunNo ratings yet

- DC Lawsuit I-295 CameraDocument40 pagesDC Lawsuit I-295 CameraABC7News100% (3)

- 2.PMS Report Template GRF - 25-46a - Rev - 1.2 - PMS - Appplication - FormDocument8 pages2.PMS Report Template GRF - 25-46a - Rev - 1.2 - PMS - Appplication - Formdelal karakuNo ratings yet

- Grilles & RegistersDocument19 pagesGrilles & RegistersBelal AlrwadiehNo ratings yet

- Fernandez vs. NoveroDocument5 pagesFernandez vs. NoveroAdrianne BenignoNo ratings yet

- 26 So Ping Bun v. Court of Appeals PDFDocument5 pages26 So Ping Bun v. Court of Appeals PDFAbegail GaledoNo ratings yet

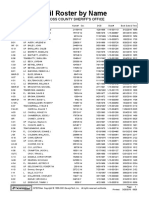

- Ross County Jail RosterDocument4 pagesRoss County Jail RosterAndy BurgoonNo ratings yet

- Feeder Vessel Companies in IndiaDocument25 pagesFeeder Vessel Companies in IndiaManoj DhumalNo ratings yet

- Deloitte Malaysia Tax Espresso (Special Edition) - 231014 - 050707Document22 pagesDeloitte Malaysia Tax Espresso (Special Edition) - 231014 - 050707steve leeNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2 - Terminal Settling VelocityDocument8 pagesLecture 2 - Terminal Settling VelocityMuhammad NaeemNo ratings yet

- Company Account Review Questions-1Document3 pagesCompany Account Review Questions-1JustineNo ratings yet

- Dato Seri Najib Razak V PP (Review) .Final @001Document32 pagesDato Seri Najib Razak V PP (Review) .Final @001sivamunusamyNo ratings yet

- Suram Ramana Reddy S/O. Rama Subba Reddy Vs The Joint Sub-Registrar - I, District Registrar Office District Court Compund, Nellore City, PSR Nellore District and OrsDocument3 pagesSuram Ramana Reddy S/O. Rama Subba Reddy Vs The Joint Sub-Registrar - I, District Registrar Office District Court Compund, Nellore City, PSR Nellore District and OrsRakshith BharadwajNo ratings yet

- Mahatma Gandhi QuotesDocument17 pagesMahatma Gandhi QuotesJaya Lakshmi ShanmugamNo ratings yet

- YFC HH Training ProgramDocument11 pagesYFC HH Training ProgramMay Angelie LopezNo ratings yet

- More Guns, Less Crime: Understanding Crime and Gun Control LawsDocument5 pagesMore Guns, Less Crime: Understanding Crime and Gun Control Lawsapi-581432219No ratings yet

- Terms and ConditionsDocument2 pagesTerms and Conditionsackyard MotoworksNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Statistics For Social Workers 8th Edition Weinbach Test Bank PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Statistics For Social Workers 8th Edition Weinbach Test Bank PDFmasonh7dswebb100% (11)

- Urdu Women's Magazines in The Early Twentieth CenturyDocument8 pagesUrdu Women's Magazines in The Early Twentieth CenturyMalem NingthoujaNo ratings yet

- SECTION 1: Identification of The Substance/mixture and of The Company/undertakingDocument10 pagesSECTION 1: Identification of The Substance/mixture and of The Company/undertakingJohnC75No ratings yet

- Remington xr1430 - xr1450 - xr1470 - Int Multi + HR - Str. 111Document128 pagesRemington xr1430 - xr1450 - xr1470 - Int Multi + HR - Str. 111SemangelafNo ratings yet

- AcFn 511-Ch II Ppt-EL-2020 Part TwoDocument67 pagesAcFn 511-Ch II Ppt-EL-2020 Part TwoSefiager MarkosNo ratings yet

- Bincy Babu (2nd Moot Court)Document15 pagesBincy Babu (2nd Moot Court)BINCY THOMAS0% (1)