Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Martinez 2021

Uploaded by

Radu CiprianOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Martinez 2021

Uploaded by

Radu CiprianCopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Dovepress

open access to scientific and medical research

Open Access Full Text Article

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 85.9.38.210 on 13-May-2021

Budesonide/Glycopyrrolate/Formoterol Fumarate

Metered Dose Inhaler Improves Exacerbation

Outcomes in Patients with COPD without

a Recent Exacerbation History: A Subgroup

Analysis of KRONOS

This article was published in the following Dove Press journal:

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

For personal use only.

1 Purpose: In the Phase III, 24-week KRONOS study (NCT02497001), triple therapy with

Fernando J Martinez

Gary T Ferguson 2 budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate metered dose inhaler (BGF MDI) reduced exacer

Eric Bourne 3 bation rates versus glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate (GFF) MDI in patients with moderate-to-

Shaila Ballal 4 very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and no requirement for a history of

exacerbations. We report a post hoc analysis investigating whether the benefits observed were

Patrick Darken 5

driven by patients with ≥1 exacerbation in the 12 months prior to the study.

Magnus Aurivillius 6

Patients and Methods: Patients received BGF MDI 320/18/9.6 µg, GFF MDI 18/9.6 µg,

Paul Dorinsky 3

budesonide/formoterol fumarate (BFF) MDI 320/9.6 µg, or budesonide/formoterol fumarate

Colin Reisner 4 dry powder inhaler (BUD/FORM DPI) 400/12 µg twice-daily. Post hoc analyses were

1

Joan and Sanford I. Weill Department of conducted on exacerbation and lung function results from patients with and without

Medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine,

a documented exacerbation in the 12 months prior to the study.

New York, NY, USA; 2Pulmonary

Research Institute of Southeast Michigan, Results: Overall, 74% (1411/1896) of the modified-intent-to-treat (mITT) population had no

Farmington Hills, MI, USA; 3AstraZeneca, moderate/severe exacerbations in the 12 months prior to the study. BGF MDI reduced

Durham, NC, USA; 4AstraZeneca,

Morristown, NJ, USA; 5AstraZeneca,

exacerbation rates versus GFF MDI in the prior (58%; unadjusted p=0.0003) and no prior

Wilmington, DE, USA; 6AstraZeneca, (48%; unadjusted p=0.0001) exacerbations subgroups. The magnitude of reduction in exacer

Gothenburg, Sweden bation rates was generally similar within subgroups for BGF MDI versus BFF MDI and

BUD/FORM DPI. In the prior exacerbations subgroup, risk during treatment for time to first

exacerbation was lower with BGF MDI versus GFF MDI (p=0.0022) and BFF MDI

(p=0.0110); excluding the first 30 days of data yielded similar results. The magnitude of

reduction in exacerbation rates for BGF MDI compared with GFF MDI increased with

eosinophil count.

Conclusion: In patients with or without a history of exacerbations in the 12 months prior to

the study, BGF MDI reduced exacerbation rates versus GFF MDI, suggesting results

observed in the overall population were not driven by the small subgroup with a prior history

of exacerbations.

Keywords: fixed-dose combination, COPD, exacerbations of COPD

Correspondence: Fernando J Martinez

Joan and Sanford I. Weill Department of

Introduction

Medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine, Bronchodilator therapy with long-acting β2-agonists (LABA) and/or long-acting

New York, NY 10065, USA muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) is the mainstay of treatment for chronic obstruc

Tel +1 646 962 2748

Email fjm2003@med.cornell.edu tive pulmonary disease (COPD).1 However, for patients who develop further

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2021:16 179–189 179

DovePress © 2021 Martinez et al. This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.

http://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S286087

php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). By accessing the

work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For

permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms (https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php).

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Martinez et al Dovepress

exacerbations of COPD, despite dual combination therapy, After randomization, patients received BGF MDI 320/18/

use of triple combination therapy with an inhaled corticos 9.6 µg (ICS/LAMA/LABA triple therapy), glycopyrrolate/

teroid (ICS), LAMA, and LABA is recommended.1 formoterol fumarate (GFF) MDI 18/9.6 μg (LAMA/LABA

Importantly, real-world evidence has demonstrated that dual therapy), or budesonide/formoterol fumarate (BFF) MDI

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 85.9.38.210 on 13-May-2021

ICS are often prescribed inappropriately, for example, in 320/9.6 μg (ICS/LABA dual therapy) all delivered via an

patients with less severe disease without a known or estab Aerosphere™ inhaler, or open-label budesonide/formoterol

lished exacerbation risk.2,3 To date, most studies of triple fumarate dry powder inhaler (BUD/FORM DPI) 400/12 μg

versus dual fixed-dose therapies have been performed in (Symbicort® Turbuhaler®; ICS/LABA), as two inhalations,

patient populations with high exacerbation risk.4–9 twice daily for 24 weeks. The doses of glycopyrrolate and

The Phase III KRONOS study (NCT02497001) formoterol fumarate are equivalent to 14.4 μg glycopyrronium

enrolled symptomatic patients (COPD Assessment Test and 10 μg formoterol fumarate dihydrate. Doses are the sum of

[CAT] score ≥10) with moderate-to-very-severe COPD two inhalations and represent half of the total daily dose.

without any requirement for experiencing an exacerbation All participants provided written informed consent and

independent ethics committee/institutional review board

in the previous year, which was the case for the majority

approvals were obtained prior to the start of the study.

of patients randomized.10 The KRONOS study evaluated

Details of individual independent ethics committees and

the efficacy and safety of the fixed-dose combination ICS/

institutional review boards are provided in the

LAMA/LABA budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol

Supplemental Appendix. The studies were conducted in

For personal use only.

fumarate metered dose inhaler (BGF MDI), administered

accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the

via an Aerosphere™ inhaler, and reported benefits on lung

International Conference on Harmonisation/Good Clinical

function and exacerbation rates versus dual therapies

Practice and applicable regulatory requirements.

(LAMA/LABA and ICS/LABA) in these patients.10

Given the high proportion of patients with no prior

Assessments

exacerbations enrolled in the study, we undertook a post

The primary endpoints of FEV1 area under the curve from 0

hoc analysis to investigate whether or not the exacerbation to 4 h (AUC0–4) over 24 weeks (BGF MDI vs BFF MDI and

benefit in the overall population of the KRONOS study BGF MDI vs BUD/FORM DPI) and change from baseline

was driven by the small subset of patients included in the in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 over 24 weeks (BGF MDI

study reporting ≥1 exacerbation in the year prior to the vs GFF MDI and BFF MDI vs BUD/FORM DPI [non-

study, or was also true for patients with no prior inferiority]) have been reported previously.10 Secondary

exacerbations. endpoints, including the rate of moderate/severe COPD

exacerbations, have also been reported.10 In this manuscript,

Methods lung function endpoints and rate of exacerbations during the

KRONOS study were analyzed post hoc for data from the

Study Design

two subgroups of patients with and without a documented

KRONOS (NCT02497001) was a 24-week, double-blind,

exacerbation in the year prior to the study.

parallel-group randomized controlled study and the design

At each visit from randomization onwards (0, 4, 8, 12,

has been previously described.10 Eligible patients were

16, 20, and 24) spirometry was conducted, as previously

40–80 years of age, with a smoking history of ≥10 pack-

reported, and occurrences of COPD exacerbations, medi

years (current or former smokers), a confirmed diagnosis

cation changes, and adverse events (AEs) were recorded in

of moderate-to-very severe COPD, as defined by a post- an electronic case report form by study personnel.10

bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) of Criteria for identifying and reporting exacerbations have

25–80% predicted, and were symptomatic (CAT score been published previously.10

≥10) despite treatment with ≥2 inhaled maintenance thera Exacerbations were categorized as: moderate (led to

pies for at least 6 weeks before screening. A current diag treatment with systemic corticosteroids, antibiotics, or

nosis of asthma was exclusionary. Patients were not both, for ≥3 days, or ≥1 depot injectable dose of corticos

required to have an exacerbation in the previous 12 teroids); or severe (led to hospital admission or a visit to

months. A COPD exacerbation was defined by modified a healthcare facility, eg an emergency department, that

Anthonisen criteria11 or physician justification.10 lasted ≥24 hours, or COPD-related death). Exacerbations

180 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2021:16

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress Martinez et al

with start and end dates that were ≤7 days apart were age 65.5 years; 72.8% male; 69.9% used ICS at screen

considered one event and assigned the maximum severity ing). The remaining 25.6% (485/1896) had at least one

between the two events. A clinically consistent definition documented moderate/severe exacerbation in the

of pneumonia was implemented to standardize the diag previous year (mean age 64.2 years; 66.6% male; 77.3%

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 85.9.38.210 on 13-May-2021

nosis of pneumonia.10 An independent clinical endpoint used ICS at screening), and 5.6% (107/1896) of patients

committee reviewed all AEs reported as pneumonia or that had a severe exacerbation(s) in the previous year.

potentially met criteria for major adverse cardiovascular

events, and additionally evaluated cause-specific mortality. Moderate/Severe Exacerbations

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were also In patients without an exacerbation in the previous year,

evaluated. the adjusted annualized rate of moderate/severe exacer

bations (number of events) was 0.41 (n=85), 0.80

(n=147), 0.42 (n=42), and 0.47 (n=47) for BGF MDI,

Statistical Analyses

GFF MDI, BFF MDI, and BUD/FORM DPI, respec

Post hoc analyses of lung function and exacerbation rates

tively (Table 2). In those with prior exacerbations, the

during the KRONOS study were conducted on data from the

adjusted annualized rate of moderate/severe exacerba

two subgroups of patients with and without an exacerbation

tions (number of events) was 0.63 (n=47), 1.50 (n=81),

within 12 months preceding the study. Efficacy analyses were

1.05 (n=32), and 0.84 (n=30) for BGF MDI, GFF MDI,

conducted in the modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population

BFF MDI, and BUD/FORM DPI, respectively

(all data obtained before discontinuation from treatment from

For personal use only.

(Table 2).

randomized patients receiving any dose of the study drug)

BGF MDI reduced the rate of moderate/severe exacer

using an efficacy estimand. Exacerbation rates were analyzed

bations versus GFF MDI by 48% in the no prior exacer

using negative binomial regression. Time at risk of experien

bations subgroup (unadjusted p=0.0001) and in the prior

cing an exacerbation was an offset variable in the model.

exacerbations subgroup by 58% (unadjusted p=0.0003)

Treatment comparisons were adjusted for baseline post-

(Table 2 and Figure 1). Moderate/severe exacerbation

bronchodilator percent predicted FEV1, baseline eosinophil

rates for BGF MDI versus BFF MDI and BGF MDI versus

count, country, ICS use at screening, and exacerbation history

BUD/FORM DPI were generally similar within subgroups

(for the overall population). Model-adjusted rates and rate

(Table 2 and Figure 1). There was also a numerical reduc

ratios were calculated. Time during an exacerbation, or in

tion in the rate of moderate/severe exacerbations with BGF

the 7 days following an exacerbation, was not included in

MDI versus GFF MDI in the subgroup of patients in the

the calculation of time at risk.

no prior exacerbations subgroup who did not receive prior

The change from baseline in morning pre-dose trough

ICS, though the sample size of this post hoc analysis was

FEV1 and FEV1 AUC0–4 over 24 weeks were analyzed

too small to allow definitive conclusions to be made

using linear models with repeated measures. The models

(Table S1).

included treatment, visit, treatment by visit interaction, and

In the prior exacerbations subgroup, for time to first

ICS use at screening as categorical covariates, and base

moderate/severe COPD exacerbation, the risk during treat

line FEV1, percent reversibility to salbutamol, and baseline

ment with BGF MDI was lower versus GFF MDI (49%;

eosinophil counts as continuous covariates. Analyses pre

unadjusted p=0.0022) and versus BFF MDI (48%; unad

sented were not included under the Type I error control

justed p=0.0110) (Table 2).

plan for the study, and therefore the p-values reported

Based on the results for BGF MDI versus GFF MDI,

within the results are unadjusted. Patients in the safety

the number needed to treat (NNT) [95% CI] for 1 year to

population are those who received at least one dose of

prevent one additional moderate/severe COPD exacerba

the study treatment.

tion was 3 [2, 6] in the no prior exacerbations subgroup

and 2 [1, 3] in the prior exacerbations subgroup. For

Results comparison, in the overall KRONOS population, NNT

Patient Demographics [95% CI] for 1 year to prevent one additional moderate/

In total, 74.4% (1411/1896) of patients in the KRONOS severe COPD exacerbation was 3 [2, 4].

mITT population had no documented moderate/severe The impact of corticosteroid therapy was noted across

exacerbations in the previous 12 months (Table 1; mean all budesonide-containing preparations as a function of

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2021:16 181

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Martinez et al Dovepress

Table 1 Patient Demographics and Characteristics by Reported History of Exacerbations

BGF MDI GFF MDI BFF MDI BUD/FORM DPI

320/18/9.6 µg 18/9.6 µg 320/9.6 µg 400/12 µg

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 85.9.38.210 on 13-May-2021

Patient exacerbation No prior Prior No prior Prior No prior Prior No prior Prior

history (n=469) (n=170) (n=473) (n=152) (n=235) (n=79) (n=234) (n=84)

Mean age, years (range) 65.4 (42−80) 63.5 (40–80) 65.3 (42–80) 64.6 (46–80) 65.8 (48–80) 63.5 (46–78) 66.1 (45–80) 65.4 (46–79)

Male, % 73 70 70 64 75 59 75 71

Race, %

Asian 42 52 44 49 45 47 44 46

Black 4 3 7 4 4 8 5 2

White 54 45 49 47 51 46 51 51

Current smokers, % 41 36 42 38 37 35 40 35

ICS use at screening, % 71 76 70 76 69 78 67 81

Blood eosinophil count

<150 cells per mm3, % 48 53 47 44 44 61 50 46

≥150 cells per mm3, % 52 47 53 56 56 39 50 54

Post-bronchodilator FEV1, 51 49 51 49 51 48 51 50

For personal use only.

mean % predicted

Notes: The following races, n (%), were recorded in the no-exacerbation subgroup only: Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, 1 (0.2) in the GFF MDI 18/9.6 µg

treatment group; American Indian or Alaska Native, 1 (0.2) in the BGF MDI 320/18/9.6 µg treatment group.

Abbreviations: BFF, budesonide/formoterol fumarate; BGF, budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate; BUD/FORM DPI, budesonide/formoterol fumarate dry

powder inhaler; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; GFF, glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; MDI, metered dose inhaler.

baseline eosinophil count, both in patients with exacerba Severe Exacerbations

tions in the year prior (Figure 2A) and in those without While not reported previously for the overall popula

prior exacerbations (Figure 2B). Rates of moderate/severe tion, the adjusted annualized rate of severe exacerba

exacerbations were lower for BGF MDI versus GFF MDI tions [number of events] was 0.047 [n=17], 0.131

in both prior and no prior exacerbations subgroups. [n=40], 0.055 [n=9], and 0.068 [n=12] for BGF MDI,

To assess the impact of acute ICS withdrawal on the GFF MDI, BFF MDI, and BUD/FORM DPI, respec

findings, we conducted analyses of exacerbations exclud tively. BGF MDI reduced the rate of severe exacerba

ing the first 30 days of data. When the first 30 days of data tions versus GFF MDI by 64% (unadjusted p=0.0026).

were excluded for patients with ICS use in the 30 days In patients without exacerbations in the

before screening, the moderate/severe exacerbation rate previous year, the adjusted annualized rate of severe

ratio was similar to the complete dataset for the overall exacerbations [number of events] was 0.046 [n=12],

population for BGF MDI versus GFF MDI (0.43 [0.31, 0.108 [n=26], 0.043 [n=6], and 0.046 [n=6] for BGF

0.60] versus 0.48 [0.37, 0.64], respectively; unadjusted MDI, GFF MDI, BFF MDI, and BUD/FORM DPI,

p<0.0001 for both) (Table S2 and Figure S1); moderate/ respectively. BGF MDI reduced the rate of severe

severe exacerbation rates for BGF MDI versus BFF MDI exacerbations versus GFF MDI by 58% (unadjusted

or BUD/FORM DPI were generally similar to the com p=0.0316) (Table 2).

plete dataset. When excluding the first 30 days in the Since only 5, 14, 3, and 6 severe exacerbations were

complete prior exacerbation population, for time to first reported for BGF MDI, GFF MDI, BFF MDI, and BUD/

moderate/severe COPD exacerbation, the risk during treat FORM DPI, respectively, in the prior exacerbations sub

ment with BGF MDI was lower versus GFF MDI (unad group, the event numbers were too small to conduct

justed p=0.0201) and versus BFF MDI (unadjusted meaningful analyses for severe exacerbations in this

p=0.0193) (Table S3,10 Figure S2). subgroup.

182 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2021:16

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress Martinez et al

Table 2 Exacerbation Outcomes by Reported History of Exacerbations in the Previous 12 Months (Efficacy Estimand, mITT

Population)

BGF MDI GFF MDI BFF MDI BUD/FORM DPI

320/18/9.6 μg 18/9.6 μg 320/9.6 μg 400/12 μg

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 85.9.38.210 on 13-May-2021

Overall population

Patients, N N=639 N=625 N=314 N=318

Rate of moderate/severe COPD exacerbations

Number of events, n 132 228 74 77

Adjusted annualized rate (SE) 0.46 (0.05) 0.95 (0.09) 0.56 (0.08) 0.55 (0.08)

Rate ratio, BGF MDI vs comparator (95% CI) – 0.48 (0.37, 0.64) 0.82 (0.58, 1.17) 0.83 (0.59, 1.18)

p-value – <0.0001 0.2792 0.3120

Time to first moderate/severe COPD exacerbation

Number of patients with exacerbations, n (%) 108 (16.9) 157 (25.1) 65 (20.7) 61 (19.2)

Hazard ratio, BGF MDI vs comparator (95% CI) – 0.59 (0.46, 0.76) 0.75 (0.55, 1.02) 0.85 (0.62, 1.17)

Cox regression p-value – <0.0001 0.0635 0.3225

Log rank p-value – 0.0001 0.0281 0.0832

Rate of severe COPD exacerbations

For personal use only.

Number of events, n 17 40 9 12

Adjusted annualized rate (SE) 0.047 (0.01) 0.131 (0.03) 0.055 (0.02) 0.068 (0.02)

Rate ratio, BGF MDI vs comparator (95% CI) – 0.36 (0.18, 0.70) 0.85 (0.34, 2.13) 0.69 (0.29, 1.61)

p-value – 0.0026 0.7363 0.3861

No prior exacerbations

Patients, N N=469 N=473 N=235 N=234

Rate of moderate/severe COPD exacerbations

Number of events, n 85 147 42 47

Adjusted annualized rate (SE) 0.41 (0.06) 0.80 (0.09) 0.42 (0.08) 0.47 (0.09)

Rate ratio, BGF MDI vs comparator (95% CI) – 0.52 (0.37, 0.72) 0.98 (0.63, 1.54) 0.88 (0.57, 1.36)

p-value – 0.0001 0.9384 0.5710

Time to first moderate/severe COPD exacerbation

Number of patients with exacerbations, n (%) 72 (15.4) 105 (22.2) 38 (16.2) 37 (15.8)

Hazard ratio, BGF MDI vs comparator (95% CI) – 0.64 (0.47, 0.86) 0.92 (0.62, 1.36) 0.93 (0.62, 1.38)

Cox regression p-value – 0.0032 0.6643 0.7105

Log rank p-value – 0.0041 0.3829 0.4415

Rate of severe COPD exacerbations

Number of events, n 12 26 6 6

Adjusted annualized rate (SE) 0.046 (0.02) 0.108 (0.03) 0.043 (0.02) 0.046 (0.02)

Rate ratio, BGF MDI vs comparator (95% CI) – 0.42 (0.19, 0.93) 1.05 (0.36, 3.11) 0.99 (0.33, 2.92)

p-value – 0.0316 0.9279 0.9817

Prior exacerbations

Patients, N N=170 N=152 N=79 N=84

Rate of moderate/severe COPD exacerbations

Number of events, n 47 81 32 30

Adjusted annualized rate (SE) 0.63 (0.12) 1.50 (0.24) 1.05 (0.25) 0.84 (0.20)

(Continued)

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2021:16 183

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Martinez et al Dovepress

Table 2 (Continued).

BGF MDI GFF MDI BFF MDI BUD/FORM DPI

320/18/9.6 μg 18/9.6 μg 320/9.6 μg 400/12 μg

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 85.9.38.210 on 13-May-2021

Rate ratio, BGF MDI vs comparator (95% CI) – 0.42 (0.26, 0.67) 0.60 (0.34, 1.08) 0.75 (0.42, 1.35)

p-value – 0.0003 0.0892 0.3423

Time to first moderate/severe COPD exacerbation

Number of patients with exacerbations, n (%) 36 (21.2) 52 (34.2) 27 (34.2) 24 (28.6)

Hazard ratio, BGF MDI vs comparator (95% CI) – 0.51 (0.33, 0.79) 0.52 (0.32, 0.86) 0.71 (0.42, 1.20)

Cox regression p-value – 0.0022 0.0110 0.2019

Log rank p-value – 0.0031 0.0052 0.0434

Rate of severe COPD exacerbations

Number of events, n 5 14 3 6

Adjusted annualized rate (SE) * * * *

Notes: Treatments are compared adjusting for baseline post-bronchodilator percent predicted FEV1 and baseline eosinophil count as continuous covariates and country and

inhaled corticosteroid use at screening (yes/no) as categorical covariates using negative binomial regression. *As the number of events is low, this precludes analysis for this group.

Abbreviations: BFF, budesonide/formoterol fumarate; BGF, budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate; BUD/FORM DPI, budesonide/formoterol fumarate dry

powder inhaler; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GFF, glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate; MDI, metered dose inhaler; mITT,

modified intent-to-treat; SE, standard error.

For personal use only.

Lung Function comparable. The incidence of confirmed pneumonia was

BGF MDI improved lung function versus BFF MDI over low in both subgroups (Table 3).10

24 weeks in patients with no prior exacerbation history

(unadjusted p<0.001), and versus BUD/FORM DPI in Discussion

both the no prior and prior exacerbation history popula This subgroup analysis from the 24-week KRONOS

tions (unadjusted p=0.0003 and p<0.0001, respectively). study demonstrated that BGF MDI reduced the rate

Analyses for both subgroups can be found in the supple of moderate/severe COPD exacerbations versus GFF

mentary information section (Table S4, Figure S3). MDI in the subgroup with no history of moderate/

severe exacerbations in the previous year. This sug

Safety gests that the exacerbation reduction in KRONOS was

The TEAE profiles of the subgroups with and without an not driven by the subset of patients with a prior his

exacerbation in the previous 12 months were generally tory of exacerbations. Importantly, the effect of ICS

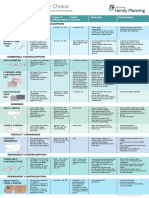

Figure 1 Treatment comparisons for rate of moderate/severe exacerbations by reported exacerbation history (mITT population; efficacy estimand).

Notes: Data presented as rate ratio (95% CI); *p≤0.0001; #p=0.0003. Eosinophil data are baseline counts in cells per mm3 across treatment groups.

Abbreviations: BFF, budesonide/formoterol fumarate; BGF, budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate; BUD/FORM DPI, budesonide/formoterol fumarate dry

powder inhaler; CI, confidence interval; GFF, glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate; MDI, metered dose inhaler; mITT, modified intent-to-treat.

184 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2021:16

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress Martinez et al

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 85.9.38.210 on 13-May-2021

For personal use only.

Figure 2 Rate of moderate/severe exacerbations for patients reporting (A) a prior exacerbation and (B) no prior exacerbations as a function of baseline eosinophil and

treatment group (mITT population, efficacy estimand). Generalized additive model plot. Banded areas represent 95% CIs.

Abbreviations: BFF, budesonide/formoterol fumarate; BGF, budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate; BUD/FORM DPI, budesonide/formoterol fumarate dry

powder inhaler; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GFF, glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate; MDI, metered dose inhaler; mITT,

modified intent-to-treat.

treatment on exacerbation rates was seen in patients Unlike many other randomized controlled studies of

with a higher blood eosinophil count regardless of triple therapy versus dual therapies in patients with symp

exacerbation history. The observed treatment effects tomatic COPD,4,5,8,9 KRONOS enrolled patients with no

on lung function, regardless of exacerbation history, requirement for an exacerbation in the previous year.10

are to be expected.1 Therefore, we were able to conduct a sub-analysis to

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2021:16 185

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Martinez et al Dovepress

Table 3 Comparison of TEAEs for No Prior Exacerbations and Prior Exacerbations Subgroups (Safety Population)

BGF MDI GFF MDI BFF MDI BUD/FORM DPI

320/18/9.6 μg 18/9.6 μg 320/9.6 μg 400/12 μg

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 85.9.38.210 on 13-May-2021

Patient exacerbation No prior Prior No prior Prior No prior Prior No prior Prior

History (n=469) (n=170) (n=473) (n=152) (n=235) (n=79) (n=234) (n=84)

Patients with at least one TEAE, n (%) 283 (60.3) 105 (61.8) 288 (60.9) 96 (63.2) 125 (53.2) 50 (63.3) 129 (55.1) 54 (64.3)

Patients with drug-related TEAEs,† n (%) 81 (17.3) 31 (18.2) 66 (14.0) 25 (16.4) 30 (12.8) 18 (22.8) 30 (12.8) 10 (11.9)

Patients with serious TEAEs, n (%) 39 (8.3) 16 (9.4) 49 (10.4) 19 (12.5) 16 (6.8) 5 (6.3) 18 (7.7) 11 (13.1)

Patients with drug-related serious TEAEs,† n (%) 5 (1.1) 2 (1.2) 8 (1.7) 4 (2.6) 1 (0.4) 2 (2.5) 5 (2.1) 1 (1.2)

Patients with TEAEs leading to early discontinuation, n (%) 26 (5.5) 4 (2.4) 26 (5.5) 4 (2.6) 7 (3.0) 4 (5.1) 8 (3.4) 3 (3.6)

Deaths (all causes), n (%) 6 (1.3) 0 1 (0.2) 2 (1.3) 2 (0.9) 0 1 (0.4) 0

Patients with confirmed major adverse CV event,* n (%) 2 (0.4) 0 2 (0.4) 1 (0.7) 1 (0.4) 1 (1.3) 2 (0.9) 0

Patients with confirmed pneumonia,** n (%) 7 (1.5) 5 (2.9) 6 (1.3) 4 (2.6) 5 (2.1) 1 (1.3) 2 (0.9) 2 (2.4)

10 †

Notes: *Confirmed by clinical endpoint committee. **Confirmed by chest imaging, antibiotic treatment and at least two symptoms. Possibly, probably, or definitely

related, in the opinion of the investigator.

Abbreviations: BFF, budesonide/formoterol fumarate; BGF, budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate; BUD/FORM DPI, budesonide/formoterol fumarate dry

powder inhaler; CV, cardiovascular; GFF, glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate; MDI, metered dose inhaler; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

examine the effect of triple therapy in patients who were when not receiving an ICS during the study (adjusted annual

symptomatic, despite being on two or more inhaled main ized rate for GFF MDI = 0.80, versus 0.41, 0.42, and 0.47 for

For personal use only.

tenance therapies, but had no documented history of BGF MDI, BFF MDI, and BUD/FORM DPI, respectively).

exacerbations in the year prior to the study. The analyses This subgroup also experienced severe exacerbations during

revealed that the effect of BGF MDI on exacerbation rates the study, although overall numbers were low. It is possible

versus LAMA/LABA was consistent in those with and that exacerbation risk was unmasked in those patients no

without prior exacerbations. In addition, the NNT for longer receiving ICS (more than 70% of these patients were

1 year to prevent one additional moderate/severe COPD receiving ICS prior to the study). Exacerbation characteris

exacerbation in BGF MDI versus GFF MDI was similar in tics and exacerbation risk can fluctuate over time and can

both subgroups (no prior history: 3; prior history: 2). affect treatment decisions for individual patients. For exam

While other triple therapy studies included patients with ple, in the 3-year SPIROMICS study, exacerbation incidence

differing exacerbation risks (eg 1 versus 2 or more), with frequently varied from year to year.13 Therefore, it is possible

the exception of the FULFIL study,7,12 none included that patients on ICS had experienced exacerbations prior to

patients with no prior exacerbations.4,5,8,9 The 24-week the 12-month period when exacerbation history was

FULFIL study was conducted in symptomatic patients collected.

with moderate-to-very severe COPD and showed that Regarding prior ICS use, the rate ratio for BGF MDI

annual moderate/severe exacerbation rates were improved versus GFF MDI exacerbation rates was similar to that of

by triple therapy versus ICS/LABA regardless of a history the overall population in the subgroup of patients with ICS

of exacerbations (0/1 moderate exacerbations, ≥2 moder use in the 30 days before screening. Moreover, the results

ate exacerbations, or ≥1 severe exacerbation).12 for moderate/severe exacerbations were similar when the

Approximately one third of patients in the FULFIL study first 30 days of data were excluded. Taken together, this

had no documented history of moderate/severe exacerba supports the view that the findings are not driven by acute

tions in the previous year.7 ICS withdrawal. Furthermore, when the first 30 days of

ICS-containing regimens are not generally recommended data were excluded from the prior exacerbations subgroup

for symptomatic patients who do not report exacerbations.1 analysis, results for exacerbation risk and time to moder

However, in the current analysis, BGF MDI reduced moder ate/severe exacerbation were similar to the complete

ate/severe and severe exacerbation rates versus LAMA/ dataset.

LABA in the subgroup of patients without a prior exacerba The reasons for prescribing an ICS prior to the

tion. In seeking an explanation for the findings, we note that KRONOS study were not captured and, as real-world

model-estimated rates of moderate/severe exacerbations studies show, ICS are commonly prescribed over a wide

showed that patients without a prior exacerbation in the spectrum of COPD phenotypes.14–18 This suggests that

previous 12 months had a substantial exacerbation rate a more careful assessment of exacerbation histories,

186 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2021:16

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress Martinez et al

analysis of blood eosinophil count, and details on why ICS exacerbations, is further evidence of the importance of

were prescribed may need to be part of future studies. exacerbation prevention in the overall management of

In the KRONOS study, the contribution of ICS in BGF COPD.29–31

MDI was demonstrated by the magnitude of risk reduction Within the current study, most patients were receiving

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 85.9.38.210 on 13-May-2021

relative to GFF MDI in a population where the majority of an ICS; therefore, the generalizability of results could be

patients had no prior exacerbations in the previous year.10 limited. Also, the potential for under-reporting exacerba

The 52-week WISDOM study suggested ICS can be tions cannot be excluded. Therefore, better characteriza

removed in many patients with a prior exacerbation history tion of exacerbation risk, based on expanded,

based on eosinophil levels. However, WISDOM was documented, prior exacerbation history (eg over 2

a randomized withdrawal study, in which approximately years), including information on prior ICS treatment

30% of patients were not receiving an ICS-containing and rationale, could allow clarification of these findings

treatment prior to the study, and all patients received triple in future studies.

therapy in the 6-week run-in before ICS withdrawal.19

These factors could have influenced the low exacerbation Conclusions

rates observed when ICS was withdrawn. The FLAME This subgroup analysis of the KRONOS study showed the

study also suggested that ICS can be removed in many benefits of BGF MDI in reducing moderate/severe and

patients with a prior exacerbation history.20 However, the severe exacerbation rates relative to GFF MDI, even

exclusion of patients with eosinophil levels >600 cells/µL among COPD patients with no history of exacerbations

For personal use only.

may have contributed to these results.21 It should be in the prior year. These findings suggest that benefits on

acknowledged that in FLAME the benefits of LAMA/ exacerbation rates observed in the KRONOS study in

LABA compared with ICS/LABA were greater in those symptomatic patients with moderate-to-very severe

with eosinophils <150 cells/µL than at higher levels where COPD were not driven by the patient subgroup with

rate ratios approached unity.21 Furthermore, the study was a history of prior exacerbations.

not designed to investigate the benefit of adding ICS to

LAMA/LABA.20 Abbreviations

In this post hoc analysis of the KRONOS study, the AE, adverse event; AUC0–4, area under curve from 0 to 4

benefits of BGF MDI relative to GFF MDI on rates of hours; BFF, budesonide/formoterol fumarate; BGF, budeso

moderate/severe exacerbation increased as eosinophil nide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate; BUD/FORM DPI,

counts increased, regardless of prior exacerbation history. budesonide/formoterol fumarate dry powder inhaler; CAT,

These results were similar to those observed for the overall COPD Assessment Test; CI, confidence interval; COPD,

population.10 The relationship between eosinophil count chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CV, cardiovascular;

and ICS treatment benefit has been previously FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; GFF, glycopyrrolate/

documented22–24 and is supported by the Global formoterol fumarate; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; LABA,

Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2020 long-acting β2-agonists; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic

recommendations,1 indicating the potential of using eosi antagonists; LSM, least-squares mean; MDI, metered dose

nophil counts as key biomarkers to inform future treatment inhaler; mITT, modified intent-to-treat; SE, standard error;

guidelines. Given the suggested benefits of a triple regi TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

men in KRONOS over both dual therapies, the role of dual

therapy in preventing exacerbations in COPD may be Data Sharing Statement

questioned. The data sets used and analyzed during the current study

Preventing exacerbations is a priority as exacerbations will be available on reasonable request in accordance with

are associated with lung function decline, morbidity, and AstraZeneca’s data sharing policy described at https://astra

mortality in COPD.25 A single exacerbation may be asso zenecagrouptrials.pharmacm.com/ST/Submission/

ciated with a significant decline in lung function26 and Disclosure.

patients experiencing frequent exacerbations are likely to

be at the greatest risk for lung function decline over Acknowledgments

time.27,28 Finally, the increased mortality risk associated The authors thank all the patients and their families, and

with COPD exacerbations, particularly severe COPD the team of investigators, research nurses, and operations

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2021:16 187

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Martinez et al Dovepress

staff involved in this study. The abstract of this paper was

presented in part at the ACCP/CHEST 2019 Congress as References

an oral presentation. The oral presentation’s abstract was 1. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. 2020 Report.

Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of

published in a supplement of the CHEST journal: CHEST

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 85.9.38.210 on 13-May-2021

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; 2020. Available from: https://

2019;156(4):A2276-2277; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest. goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/GOLD-2020-REPORT-

2019.08.309 ver1.0wms.pdf. Accessed January 28, 2020.

2. Price D, Miravitlles M, Pavord I, et al. First maintenance therapy for

COPD in the UK between 2009 and 2012: a retrospective database

Author Contributions analysis. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2016;26(1):16061.

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revis doi:10.1038/npjpcrm.2016.61

3. Wei YF, Kuo PH, Tsai YH, et al. Factors associated with the pre

ing the article, have agreed on the journal to which the scription of inhaled corticosteroids in GOLD group A and B patients

article will be submitted, gave final approval of the version with C. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10(10):1951–1956.

doi:10.2147/COPD.S88114

to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects

4. Papi A, Vestbo J, Fabbri L, et al. Extrafine inhaled triple therapy

of the work. versus dual bronchodilator therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease (TRIBUTE): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised con

trolled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10125):1076–1084. doi:10.1016/

Funding S0140-6736(18)30206-X

This study was supported by AstraZeneca. The funders of 5. Singh D, Papi A, Corradi M, et al. Single inhaler triple therapy versus

the study had a role in the study design, data analysis, data inhaled corticosteroid plus long-acting β2-agonist therapy for chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease (TRILOGY): a double-blind, parallel

interpretation, and writing of the report. Medical writing group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388

For personal use only.

support, under the direction of the authors, was provided (10048):963–973. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31354-X

6. Vestbo J, Papi A, Corradi M, et al. Single inhaler extrafine triple

by Audrey Gillies, MPhys, CMC Connect, McCann Health

therapy versus long-acting muscarinic antagonist therapy for chronic

Medical Communications Ltd, funded by AstraZeneca in obstructive pulmonary disease (TRINITY): a double-blind, parallel

accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389

(10082):1919–1929. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30188-5

guidelines.32 7. Lipson DA, Barnacle H, Birk R, et al. FULFIL trial: once-daily triple

therapy for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am

Disclosure J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(4):438–446. doi:10.1164/

rccm.201703-0449OC

FJM reports grants from AstraZeneca during the conduct of 8. Lipson DA, Barnhart F, Brealey N, et al. Once-daily single-inhaler

the study; personal fees and non-financial support from triple versus dual therapy in patients with COPD. N Engl J Med.

2018;378(18):1671–1680. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1713901

AbbVie, Afferent Pharmaceuticals Inc/Merck, Bayer,

9. Rabe KF, Martinez FJ, Ferguson GT, et al. Triple inhaled therapy at

Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, two glucocorticoid doses in moderate-to-very-severe COPD. N Engl

Chiesi, CSL Behring, DevPro, Gala, Genentech, Gilead, J Med. 2020;383(1):35–48. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1916046

10. Ferguson GT, Rabe KF, Martinez FJ, et al. Triple therapy with

GlaxoSmithKline, IQVIA, Nitto, Novartis, Promedior/ budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate with co-suspension

Roche, ProterrixBio, Raziel, Patara/Respivant, Sanofi/ delivery technology versus dual therapies in chronic obstructive

Regeneron, Sunovion, Teva, TwoXAR, Veracyte, Verona, pulmonary disease (KRONOS): a double-blind, parallel-group, multi

centre, Phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med.

Zambon; and grants from National Institutes of Health, out 2018;6(10):747–758. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30327-8

side of the submitted work. GTF reports grants, personal 11. Anthonisen NR, Manfreda J, Warren CP, Hershfield ES, Harding GK,

Nelson NA. Antibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic obstruc

fees, and non-financial support from AstraZeneca during

tive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106(2):196–204.

the conduct of the study; grants, personal fees, and non- doi:10.7326/0003-4819-106-2-196

financial support from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, 12. Halpin DMG, Birk R, Brealey N, et al. Single-inhaler triple therapy in

symptomatic COPD patients: FULFIL subgroup analyses. ERJ Open

Novartis, and Sunovion; grants and personal fees from Res. 2018;4(2):00119–2017. doi:10.1183/23120541.00119-2017

Theravance; and personal fees from Circassia, Galderma, 13. Han MK, Quibrera PM, Carretta EE, et al. Frequency of exacerba

GlaxoSmithKline, Innoviva, Mylan, Orpheris, Sanofi, Teva, tions in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an

analysis of the SPIROMICS cohort. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5

and Verona, grants from Altavant and Knopp, outside of the (8):619–626. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30207-2

submitted work. PDa, MA, and PDo are employees of 14. Ding B, Small M, Holmgren U. A cross-sectional survey of current

treatment and symptom burden of patients with COPD consulting for

AstraZeneca and hold stock and/or stock options in the

routine care according to GOLD 2014 classifications. Int J Chron

company. SB is a former employee of AstraZeneca. EB and Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:1527–1537. doi:10.2147/COPD.S133793

CR are former employees of AstraZeneca and hold stock 15. Brusselle G, Price D, Gruffydd-Jones K, et al. The inevitable drift to

triple therapy in COPD: an analysis of prescribing pathways in the

and/or stock options in the company. The authors report no UK. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2207–2217.

other conflicts of interest in this work. doi:10.2147/COPD.S91694

188 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2021:16

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress Martinez et al

16. Savran O, Godtfredsen N, Sørensen T, Jensen C, Ulrik CS. COPD 25. Anzueto A. Impact of exacerbations on COPD. Eur Respir Rev.

patients prescribed inhaled corticosteroid in general practice: based 2010;19(116):113–118. doi:10.1183/09059180.00002610

on disease characteristics according to guidelines? Chron Respir Dis. 26. Halpin DMG, Decramer M, Celli BR, Mueller A, Metzdorf N,

2019;16:1479973119867949. doi:10.1177/1479973119867949 Tashkin DP. Effect of a single exacerbation on decline in lung func

17. Graf J, Jörres RA, Lucke T, Nowak D, Vogelmeier CF, Ficker JH. tion in COPD. Respir Med. 2017;128:85–91. doi:10.1016/j.

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 85.9.38.210 on 13-May-2021

Medical Treatment of COPD: an analysis of guideline-adherent pre rmed.2017.04.013

scribing in a large national cohort (COSYCONET). Dtsch Arztebl Int. 27. Donaldson GC, Seemungal TAR, Bhowmik A, Wedzicha JA.

2018;155(37):599–605. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2018.0599 Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function

18. Lane DC, Stemkowski S, Stanford RH, Tao Z. Initiation of triple decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2002;57

therapy with multiple inhalers in chronic obstructive pulmonary dis (10):847–852. doi:10.1136/thorax.57.10.847

ease: an analysis of treatment patterns from a U.S. retrospective 28. Dransfield MT, Kunisaki KM, Strand MJ, et al. Acute exacerbations

database study. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24 and lung function loss in smokers with and without chronic obstruc

(11):1165–1172. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2018.24.11.1165 tive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195

19. Magnussen H, Disse B, Rodriguez-Roisin R, et al. Withdrawal of (3):324–330. doi:10.1164/rccm.201605-1014OC

inhaled glucocorticoids and exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 29. Soler-Cataluña JJ, Martínez-García MA, Román Sánchez P,

2014;371(14):1285–1294. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1407154 Salcedo E, Navarro M, Ochando R. Severe acute exacerbations and

20. Wedzicha JA, Banerji D, Chapman KR, et al. Indacaterol- mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

glycopyrronium versus salmeterol-fluticasone for COPD. N Engl

Thorax. 2005;60(11):925–931. doi:10.1136/thx.2005.040527

J Med. 2016;374(23):2222–2234. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1516385 30. Rothnie KJ, Müllerová H, Smeeth L, Quint JK. Natural history of

21. Roche N, Chapman KR, Vogelmeier CF, et al. Blood eosinophils and

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations in a general

response to maintenance chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treat

practice-based population with chronic obstructive pulmonary

ment. Data from the FLAME trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.

disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(4):464–471.

2017;195(9):1189–1197. doi:10.1164/rccm.201701-0193OC

doi:10.1164/rccm.201710-2029OC

22. Siddiqui SH, Guasconi A, Vestbo J, et al. Blood eosinophils:

31. Suissa S, Dell’Aniello S, Ernst P. Long-term natural history of

a biomarker of response to extrafine beclomethasone/formoterol in

For personal use only.

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: severe exacerbations and

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.

mortality. Thorax. 2012;67(11):957–963. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-

2015;192(4):523–525. doi:10.1164/rccm.201502-0235LE

23. Pascoe S, Barnes N, Brusselle G, et al. Blood eosinophils and 2011-201518

treatment response with triple and dual combination therapy in 32. Battisti WP, Wager E, Baltzer L, et al. Good publication practice for

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: analysis of the IMPACT communicating company-sponsored medical research: GPP3. Ann

trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(9):745–756. doi:10.1016/S2213- Intern Med. 2015;163(6):461–464. doi:10.7326/M15-0288

2600(19)30190-0

24. Pascoe S, Locantore N, Dransfield MT, Barnes NC, Pavord ID. Blood

eosinophil counts, exacerbations, and response to the addition of

inhaled fluticasone furoate to vilanterol in patients with chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease: a secondary analysis of data from

two parallel randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med.

2015;3(6):435–442. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00106-X

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Dovepress

Publish your work in this journal

The International Journal of COPD is an international, peer-reviewed protocols. This journal is indexed on PubMed Central, MedLine

journal of therapeutics and pharmacology focusing on concise rapid and CAS. The manuscript management system is completely online

reporting of clinical studies and reviews in COPD. Special focus is and includes a very quick and fair peer-review system, which is

given to the pathophysiological processes underlying the disease, inter all easy to use. Visit http://www.dovepress.com/testimonials.php to

vention programs, patient focused education, and self management read real quotes from published authors.

Submit your manuscript here: https://www.dovepress.com/international-journal-of-chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-journal

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2021:16 189

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

You might also like

- Telerehab in Covid and CopdDocument13 pagesTelerehab in Covid and CopdNelson LoboNo ratings yet

- Copd 263031 Pulmonary Rehabilitation in A Post Covid 19 World TelerehabDocument13 pagesCopd 263031 Pulmonary Rehabilitation in A Post Covid 19 World TelerehabGe NavNo ratings yet

- COPDDocument9 pagesCOPDAndre ErlisNo ratings yet

- Copd 16 79Document11 pagesCopd 16 79Karina UtariNo ratings yet

- Are Pulmonologists Well Aware of Planning Safe Air Travel For Patients With COPD? The SAFCOP StudyDocument6 pagesAre Pulmonologists Well Aware of Planning Safe Air Travel For Patients With COPD? The SAFCOP Studynoviaac077No ratings yet

- Copd Misuse of Inhaler Devices in Clinical PracticeDocument9 pagesCopd Misuse of Inhaler Devices in Clinical PracticeAshif AnsariNo ratings yet

- Ohar 2016Document13 pagesOhar 2016lasinah272No ratings yet

- External Validation of The PUMA COPD Diagnostic Questionnaire in A General Practice Sample and The PLATINO Study PopulationDocument11 pagesExternal Validation of The PUMA COPD Diagnostic Questionnaire in A General Practice Sample and The PLATINO Study PopulationrahelNo ratings yet

- GOLD 2021 Strategy Report: Implications For Asthma-COPD OverlapDocument7 pagesGOLD 2021 Strategy Report: Implications For Asthma-COPD OverlapIan HuangNo ratings yet

- Copd 300569 Effects of Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation StretchDocument9 pagesCopd 300569 Effects of Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation StretchYusuf WildanNo ratings yet

- 2021 - Gómez AntúnezDocument13 pages2021 - Gómez AntúnezCarlosSorianNo ratings yet

- Extrafine Triple Therapy Delays Copd Clinically Important Deterioration Vs Ics/Laba, Lama, or Laba/LamaDocument16 pagesExtrafine Triple Therapy Delays Copd Clinically Important Deterioration Vs Ics/Laba, Lama, or Laba/LamatriNo ratings yet

- Martinez Garcia2017Document11 pagesMartinez Garcia2017Constantin PopescuNo ratings yet

- Price Et Al., International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2022Document16 pagesPrice Et Al., International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2022Radu CiprianNo ratings yet

- Beclomethasone/formoterol Versus Budesonide/formoterol Combination Therapy in AsthmaDocument8 pagesBeclomethasone/formoterol Versus Budesonide/formoterol Combination Therapy in AsthmalalaNo ratings yet

- Copd 291807 Association Between Thyroid Function and Acute Exacerbation FixDocument7 pagesCopd 291807 Association Between Thyroid Function and Acute Exacerbation FixMarshall ThompsonNo ratings yet

- Jbcxfjsrydt 7689 Yoyfdtuyiouyugchfjyupihcvhgjuyoi YgcmhluipyghvjkiDocument12 pagesJbcxfjsrydt 7689 Yoyfdtuyiouyugchfjyupihcvhgjuyoi YgcmhluipyghvjkiyovanNo ratings yet

- Copd 224735 Impact of Peak Oxygen Pulse On Patients With Chronic ObstrucDocument9 pagesCopd 224735 Impact of Peak Oxygen Pulse On Patients With Chronic ObstrucaninnaNo ratings yet

- Hand Grip Endurance Test Relates To Clinical State and Prognosis in COPD Patients Better Than 6-Minute Walk Test DistanceDocument7 pagesHand Grip Endurance Test Relates To Clinical State and Prognosis in COPD Patients Better Than 6-Minute Walk Test DistanceDiana Laura MtzNo ratings yet

- Adherence-Inhaled-Therapy-In-Copd & PneumoconiosisDocument10 pagesAdherence-Inhaled-Therapy-In-Copd & PneumoconiosissukiyantoNo ratings yet

- Step Up and Step Down Treatment Approaches For COPD A Holistic ViewDocument12 pagesStep Up and Step Down Treatment Approaches For COPD A Holistic ViewcastillojessNo ratings yet

- Evaluación Manual Del DiafragmaDocument8 pagesEvaluación Manual Del DiafragmaSilvia Victoria SavaroNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Tiotropium Once Daily, Formoterol Twice Daily and Both Combined Once Daily in Patients With COPDDocument9 pagesComparison of Tiotropium Once Daily, Formoterol Twice Daily and Both Combined Once Daily in Patients With COPDArezoo JamNo ratings yet

- COPD 70257 How Do Copd Comorbidities Affect Icu Outcomes 101714Document10 pagesCOPD 70257 How Do Copd Comorbidities Affect Icu Outcomes 101714Ilham Akbar SuryaNo ratings yet

- The Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome - Do We Really Need Another Syndrome in The Already Complex Matrix of Airway Disease?Document10 pagesThe Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome - Do We Really Need Another Syndrome in The Already Complex Matrix of Airway Disease?HoracioNo ratings yet

- Copd 10 1787Document14 pagesCopd 10 1787YOBEL NATHANIELNo ratings yet

- Tribute TrialDocument9 pagesTribute TrialMr. LNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of COPD: A Case Study: RespiratoryDocument4 pagesDiagnosis and Management of COPD: A Case Study: RespiratoryUssy TsnnnNo ratings yet

- Nejme 2305752Document2 pagesNejme 23057525fqkqkcdhtNo ratings yet

- 2018 JMKH - Rediscovery of Old Drugs The Forgotten Case of Dermorphin For Postoperative Pain and PalliationDocument5 pages2018 JMKH - Rediscovery of Old Drugs The Forgotten Case of Dermorphin For Postoperative Pain and PalliationBruna RossiNo ratings yet

- β-Blockers for the prevention of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (βLOCK COPD) : a randomised controlled study protocolDocument10 pagesβ-Blockers for the prevention of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (βLOCK COPD) : a randomised controlled study protocolAnonymous SdnoIOtjNo ratings yet

- 10 2147@cpaa S269156 PDFDocument7 pages10 2147@cpaa S269156 PDFMarco Antonio Tarazona MoyaNo ratings yet

- Withdrawal of Inhaled GlucocorticoidsDocument10 pagesWithdrawal of Inhaled GlucocorticoidsAndi MarwansyahNo ratings yet

- COPD 22896 A Pilot Study of The Impact of High Frequency Chest Wall Osc 121311Document7 pagesCOPD 22896 A Pilot Study of The Impact of High Frequency Chest Wall Osc 121311farahNo ratings yet

- Usmani 2021 AerosphereDocument12 pagesUsmani 2021 AerosphereRadu CiprianNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of COPD A Case StudyDocument4 pagesDiagnosis and Management of COPD A Case StudyZairenee QuizanaNo ratings yet

- COPD 365771 New Perspectives On Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseDocument10 pagesCOPD 365771 New Perspectives On Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseDi LaNo ratings yet

- 2015 Article 218Document14 pages2015 Article 218Fi NoNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Safety of Tiotropiumolodaterol Respimat® in Patients With Moderate-To-Very Severe COPD and Renal Impairment in The TONADO® StudiesDocument13 pagesLong-Term Safety of Tiotropiumolodaterol Respimat® in Patients With Moderate-To-Very Severe COPD and Renal Impairment in The TONADO® StudiesyuliaNo ratings yet

- 2010 - Cazzola - Roflumilast in COPD-Evidence From Large TrialsDocument9 pages2010 - Cazzola - Roflumilast in COPD-Evidence From Large TrialsTulus JavaNo ratings yet

- JAnaesthClinPharmacol371114-28986 000449Document5 pagesJAnaesthClinPharmacol371114-28986 000449Ferdy RahadiyanNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Acebrophylline Vs Sustained Release Theophylline in Pati...Document4 pagesThe Effect of Acebrophylline Vs Sustained Release Theophylline in Pati...Agencia FaroNo ratings yet

- Jama Ekstrm 2022 Oi 220121 1677095970.30024Document11 pagesJama Ekstrm 2022 Oi 220121 1677095970.30024zyz6639No ratings yet

- Cost Effectiveness of Single Inhaler Extrafine Beclometasone Di - 2022 - RespiraDocument8 pagesCost Effectiveness of Single Inhaler Extrafine Beclometasone Di - 2022 - RespiraFernando SarmientoNo ratings yet

- Copd 12 907Document16 pagesCopd 12 907Rafael IslasNo ratings yet

- Copd 11 535Document8 pagesCopd 11 535Rasangi Sumudu Clare SuraweeraNo ratings yet

- B2 AgonistDocument18 pagesB2 AgonistrudiNo ratings yet

- Recent Advances in Chronotherapy For The Management of AsthmaDocument11 pagesRecent Advances in Chronotherapy For The Management of AsthmaPut R MikatiNo ratings yet

- Articulo Farmacologia PulmonarDocument9 pagesArticulo Farmacologia PulmonarKatherin MoralesNo ratings yet

- Recent Insights Into The Management of Pleural InfDocument15 pagesRecent Insights Into The Management of Pleural InfstellacharlesNo ratings yet

- Terapia Triple para EPOCDocument14 pagesTerapia Triple para EPOCSebastian Cebrian GuerreroNo ratings yet

- Endobronchial Valves For Severe EmphysemaDocument7 pagesEndobronchial Valves For Severe EmphysemairfanNo ratings yet

- DDDT 221437 Ketamine and Depression A Narrative ReviewDocument17 pagesDDDT 221437 Ketamine and Depression A Narrative ReviewMatias AguileraNo ratings yet

- 1304 FullDocument9 pages1304 Fullemilija.kostadinovNo ratings yet

- A Case Report of Primary Spontaneous PneumothoraxDocument1 pageA Case Report of Primary Spontaneous PneumothoraxAGNES TRIANA BASJANo ratings yet

- Klein Weigel2016Document8 pagesKlein Weigel2016Husni mubarakNo ratings yet

- Adverse Reactions in Leprosy Patients Who Underwent Dapsone Multidrug Therapy: A Retrospective StudyDocument6 pagesAdverse Reactions in Leprosy Patients Who Underwent Dapsone Multidrug Therapy: A Retrospective StudyTheva CharaanNo ratings yet

- Researcharticle Open Access: Yanmei Bi, Yushan Ma, Juan Ni and Lan WuDocument10 pagesResearcharticle Open Access: Yanmei Bi, Yushan Ma, Juan Ni and Lan WuRichard PhoNo ratings yet

- 2019 Article 892Document10 pages2019 Article 892Richard PhoNo ratings yet

- Usmani 2021 AerosphereDocument12 pagesUsmani 2021 AerosphereRadu CiprianNo ratings yet

- Webster 2010 Horizons-AmiDocument1 pageWebster 2010 Horizons-AmiRadu CiprianNo ratings yet

- Ferguson 2018 Co-SuspensieDocument8 pagesFerguson 2018 Co-SuspensieRadu CiprianNo ratings yet

- Ethos 2020Document14 pagesEthos 2020Radu CiprianNo ratings yet

- Stone Champion PH PDFDocument10 pagesStone Champion PH PDFRadu CiprianNo ratings yet

- Singh 2015 PDFDocument83 pagesSingh 2015 PDFRadu CiprianNo ratings yet

- Dargaville 2021Document10 pagesDargaville 2021Radu CiprianNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Pulmonology 2021, Dell'ortoDocument8 pagesPediatric Pulmonology 2021, Dell'ortoRadu CiprianNo ratings yet

- Canadian Guidelines 2021Document7 pagesCanadian Guidelines 2021Radu CiprianNo ratings yet

- Price Et Al., International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2022Document16 pagesPrice Et Al., International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2022Radu CiprianNo ratings yet

- Gunther H., Elsevier, Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Properties Important For ICSDocument9 pagesGunther H., Elsevier, Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Properties Important For ICSRadu CiprianNo ratings yet

- Abdullah A. K., Et Al, 2007, J. Asthma, Evidence-Based Selection of Inhaled Corticosteroid For Treatment of Chronic AsthmaDocument13 pagesAbdullah A. K., Et Al, 2007, J. Asthma, Evidence-Based Selection of Inhaled Corticosteroid For Treatment of Chronic AsthmaRadu CiprianNo ratings yet

- Veterinary Neurologic Rehabilitation The Rationale For ADocument9 pagesVeterinary Neurologic Rehabilitation The Rationale For ACarolina Vargas VélezNo ratings yet

- Health Assessment in Nursing Weber 5th Edition Test BankDocument9 pagesHealth Assessment in Nursing Weber 5th Edition Test BankSpencerMoorenbds100% (35)

- Clinical Guidelines For The Use of Granulocyte TransfusionsDocument13 pagesClinical Guidelines For The Use of Granulocyte Transfusionssm19790% (1)

- Romano Et Al-2024-Cochrane Database of Systematic ReviewsDocument111 pagesRomano Et Al-2024-Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviewsaraujoaoh07No ratings yet

- NCP JaundiceDocument3 pagesNCP Jaundiceanilobaid84% (25)

- Immunology of Transplant RejectionDocument8 pagesImmunology of Transplant Rejectionxplaind100% (1)

- Finkel 2017Document11 pagesFinkel 2017akshayajainaNo ratings yet

- Domain 2 Public Health AnnotationsDocument9 pagesDomain 2 Public Health AnnotationsjkdanielesNo ratings yet

- Contraception Options in New ZealandDocument2 pagesContraception Options in New ZealandStuff NewsroomNo ratings yet

- Marijuana: Aron H. Lichtman Professor Department of Pharmacology and ToxicologyDocument67 pagesMarijuana: Aron H. Lichtman Professor Department of Pharmacology and Toxicologyunknown racerx50No ratings yet

- Chapter One Assessment of Patient and FamilyDocument49 pagesChapter One Assessment of Patient and FamilyEnoch OseiNo ratings yet

- Practice Nurseled Proactive Care For Chronic Depression in Primary Care A Randomised Controlled TrialDocument7 pagesPractice Nurseled Proactive Care For Chronic Depression in Primary Care A Randomised Controlled TrialIndah SundariNo ratings yet

- PatellofemuralDocument216 pagesPatellofemuralandrei_costea100% (2)

- Class 12 Physical Education Chapter 1 Planning in Sports Question/AnswerDocument7 pagesClass 12 Physical Education Chapter 1 Planning in Sports Question/AnswerPihoo MohanNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Using MMSDocument6 pagesFundamentals of Using MMSJoe100% (1)

- Acute CervicitisDocument9 pagesAcute CervicitisVicobeingoNo ratings yet

- PReS 2022 Final Programme Vscreen2Document88 pagesPReS 2022 Final Programme Vscreen2Mike KrikNo ratings yet

- Monaco Treatment Planning Enhances Departmental EfficienciesDocument9 pagesMonaco Treatment Planning Enhances Departmental Efficienciesricky rdnNo ratings yet

- Autolog Medtronic User ManualDocument34 pagesAutolog Medtronic User Manual111No ratings yet

- To Hospitals & Hospital PhrmacyDocument27 pagesTo Hospitals & Hospital PhrmacyBvayNo ratings yet

- Public Health Situation Analysis Myanmar Sear WhoDocument29 pagesPublic Health Situation Analysis Myanmar Sear Wholinwaiaung500No ratings yet

- Nursing Process OUTPUTDocument5 pagesNursing Process OUTPUTfima_njNo ratings yet

- How To Critically Appraise A PaperDocument6 pagesHow To Critically Appraise A PaperAmbar RahmanNo ratings yet

- 0312 Antibody IdDocument18 pages0312 Antibody IdKen WayNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Blunt TraumaDocument10 pagesPediatric Blunt TraumaBernard100% (1)

- Depression FactsDocument5 pagesDepression FactsStargazerNo ratings yet

- Hiatus Hernia - Chinese Herbs, Chinese Medicine, AcupunctureDocument6 pagesHiatus Hernia - Chinese Herbs, Chinese Medicine, AcupunctureCarlCordNo ratings yet

- M104 - ExamDocument8 pagesM104 - ExamChrystal Anne Flores CorderoNo ratings yet

- Postpartum Abdominal PainDocument4 pagesPostpartum Abdominal PainPinto ModakNo ratings yet

- Udder & TeatDocument23 pagesUdder & TeatAdarshBijapurNo ratings yet

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)From EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (404)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (82)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (34)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (46)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (170)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Twentysomething Treatment: A Revolutionary Remedy for an Uncertain AgeFrom EverandThe Twentysomething Treatment: A Revolutionary Remedy for an Uncertain AgeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Manipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesFrom EverandManipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1412)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (44)

- Summary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (8)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- How to ADHD: The Ultimate Guide and Strategies for Productivity and Well-BeingFrom EverandHow to ADHD: The Ultimate Guide and Strategies for Productivity and Well-BeingRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (2)

- To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceFrom EverandTo Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (51)

- Self-Care for Autistic People: 100+ Ways to Recharge, De-Stress, and Unmask!From EverandSelf-Care for Autistic People: 100+ Ways to Recharge, De-Stress, and Unmask!Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsFrom EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsFrom EverandCritical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (39)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeFrom EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (254)