Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Journal of Communication Inquiry: Book Review: Myths For The Masses

Journal of Communication Inquiry: Book Review: Myths For The Masses

Uploaded by

MondoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Communication Inquiry: Book Review: Myths For The Masses

Journal of Communication Inquiry: Book Review: Myths For The Masses

Uploaded by

MondoCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Communication Inquiry http://jci.sagepub.

com/

Book Review: Myths for the Masses

Mark Andrejevic

Journal of Communication Inquiry 2005 29: 277

DOI: 10.1177/0196859905275479

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://jci.sagepub.com/content/29/3/277

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Published in Association with The Iowa Center for Communication Study

Additional services and information for Journal of Communication Inquiry can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://jci.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://jci.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://jci.sagepub.com/content/29/3/277.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Jun 10, 2005

What is This?

Downloaded from jci.sagepub.com at Claremont Colleges Library on October 25, 2014

Journal REVIEWS

10.1177/0196859905275479

BOOK of Communication Inquiry

Myths for the Masses, by Hanno Hardt. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004, 153

pp., ISBN 0-631-23621-X (hardcover).

More than a year after the United States made its controversial decision to invade

Iraq and divest it of its elusive weapons of mass destruction, the nation’s two most

prominent political newspapers of record, the New York Times and Washington Post,

publicly apologized for their shoddy coverage during the build-up to war. The admit-

tedly flawed reporting and the papers’ public hand wringing received little attention,

far less than had been given to two other media botches: the fabricated feature stories

of Times reporter Jayson Blair and famed news anchor Dan Rather’s failed attempt to

break a story critical of President Bush’s National Guard Service. Amid all the hoopla

surrounding the Rather scandal, moreover, the core question as to whether Bush

shirked his duties or received special treatment remained ignored and unanswered. In

the era of the hyperconcentrated entertainment industrial complex, it seems even the

coverage of the coverage is flawed: The emphasis remains on mistakes that are sensa-

tional but trivial. What better time, in short, for a polemic on the fate and failings of the

mass media?

Hanno Hardt’s Myths for the Masses, part of Blackwell’s Manifestos series, pro-

vides a theoretically rich salvo from the academic world, offering a wide-ranging con-

sideration of the shortcomings and largely unredeemed democratic potential of the

mass media in the contemporary climate of conglomeration and hypercommercialism.

The format, a 141-page, two-part essay, allows Hardt the freedom to cover a range of

issues and to bring the breadth of his theoretical and historical knowledge to bear on

the current state of an industry that facilitates “the production of consent and compli-

ance” (p. 28) rather than individual autonomy and democratic participation. The book

is not a densely argued tome, but rather a loose and rangy but tactical overview that, in

keeping with the spirit of the manifesto, relies on Hardt’s impressive command of the

tradition of mass communication research and social theory to ponder the past, pres-

ent, and potential future of the industry and the society it serves. The result is a medi-

tation on a career’s worth of reading in the field, and beyond, that draws on authors

ranging from Dewey and Lippmann to Lacan and Debord.

Hardt, whose approach is carefully but relentlessly dialectic, hews close to the sen-

sibility of the manifesto, which, as Janet Lyon (1999) puts it, “is the form that exposes

the broken promises of modernity” (p. 3). Thus, Hardt touches on the sore points of

a media industry that has failed to live up to the promise of facilitating democratic par-

ticipation, slavishly serves the interests of economic and political elites, and has pre-

sided over and participated in the displacement of public deliberation by sensation-

alized spin, leveling the distinction between citizenship and consumption. Early on in

the book, he traces the coordinates of the structural transformation described by

Habermas: Mass media that got their start as tools in the service of revolutionary and

Journal of Communication Inquiry 29:3 (July 2005): 277-280

DOI: 10.1177/0196859905275479

© 2005 Sage Publications

277

Downloaded from jci.sagepub.com at Claremont Colleges Library on October 25, 2014

278 Journal of Communication Inquiry

emancipatory interests were all too quickly enlisted to provide propaganda for the new

status quo and economic elites. The promise of the Great Society defaults to propa-

ganda for the “ownership society.” At the same time, Hardt is not willing to give up on

the media. To surrender their potential would be to ignore the power of the unfulfilled

promise that continues to sustain them. Indeed, it would be to undermine the efficacy

of the manifesto form itself, which, as Lyon suggests, “promulgates the very dis-

courses it critiques: it makes itself intelligible to the dominant order through a logic

that presumes the efficacy of modern democratic ideals” (p. 3). Why bother publishing

a manifesto in a commercial media market, unless such ideals retain their purchase

even if, or perhaps in part because, they remain so aggressively unfulfilled? For Hardt,

the mass media remain multisided phenomena even if they seem to have landed with

the avaricious and shallow side face up. There are, he suggests, potentials lurking

beneath the surface: “mass communication appear as a force for integration, positively

through assimilation into a common culture and negatively through hegemonic prac-

tices of incorporation” (p. 14).

The first part of the book traces the historical role of the mass media in facilitating

and then thwarting the process of deliberation and the promise of democratic partici-

pation. The dialectic of individuality and community has, under the pressure of capi-

tal, developed exactly the wrong way according to Hardt: The homogenization of indi-

vidual desire channeled through the mechanism of the market is accompanied by the

demolition of commonality through “mobility, heterogeneity, and centralization”

(p. 43). In the wake of the decline of traditional social relations, the promise of the

mass media to reinvent community on a broader, more decentralized scale defaulted to

the promotion of “consumption as a routinized form of participation in the (commer-

cial) life of society” (p. 44).

Hardt outlines the history of the marketplace of ideas’ assimilation to the market-

ing of ideology and the default of the public interest to whatever catches the public’s

attention. He blames the American ideology of technological progress and an un-

fettered faith in privatization, commercialization, and the marketplace model of

democracy. The result he describes is a free press only in the sense of “Pepsi Free”:

mass produced, saccharine, and without substance: “There is no free press—or free-

dom of expression—in a society of captive audiences, where mass communication

turns into an ideologically predetermined performance for the purpose of commercial

gain rather than public enlightenment” (p. 51). The indictment is severe but, unfortu-

nately, deserved, especially with respect to U.S. television news outlets, which gen-

erate pyrotechnic entertainment, but disturbingly little in the way of investigative,

thoughtful news coverage. Instead of repeating Hardt’s charges, however, it is perhaps

useful to judge media performance by its results. Consider, for example, the fact noted

by the Christian Science Monitor that saturation news coverage of the September 11

attacks and the subsequent U.S. response seemed to reduce the level of popular knowl-

edge with time. Shortly after the attacks, polls indicated that only 3% of those asked

who was behind the attacks mentioned Iraq. A year later, more than 44% of those

polled thought that either most or some of the hijackers were Iraqi. The media’s failure

to subject administration claims to critical scrutiny, based just as assuredly on market-

ing concerns as an unreflective form of patriotism, had taken its toll.

Downloaded from jci.sagepub.com at Claremont Colleges Library on October 25, 2014

BOOK REVIEWS 279

Hardt’s program for critical communication studies—to be undertaken in the inter-

est of reform—is twofold: to subject the mass communication studies tradition itself to

critical scrutiny and to connect theoretical claims “with the specifics of everyday expe-

riences” (p. 69). In an era in which the promise of participation has been assimilated to

the forms of monitoring and data gathering made possible by the advent of interactive

electronic media, Hardt calls for a critical approach that cuts through the marketing

rhetoric to “clarify notions of participation, access, and control of the means of mass

communication while insisting on freedom of the press as a universal right rather than

a particular property right” (p. 73). And here, perhaps, is what distinguishes media

manifestos on the left from those of the right: the attempt to locate failures not in the

personal biases and political concerns of media workers, but in the limitations

imposed by the commercial structure of the mass media: “Intellectual freedom is never

the issue as long as journalists or other creative workers remain subservient to media

ownership, while the latter insist on being identified with democratic practices and the

idea of press freedom” (p. 78). Freedom of the press, in such an account, might better

be identified as freedom from the strictures of commercial ownership.

In the book’s second essay, Hardt narrows his focus to the implications of mass

media for a conception of self in contemporary society, exploring the ways in which

they assimilate the “very idea of communication” to “a form of participation as con-

sumption” (p. 93) and perform the ideological work of personalizing, and thus de-

contextualizing, social problems. As in the case of most polemics, not a pejorative

term within the context of a manifesto, the book is short on concrete examples and

explications. The goal is not to build a case for a comprehensive interpretation of con-

temporary media practice so much as it is to diagnose the intersecting communication

pathologies of an ailing society. The one example he does invoke is that of the Septem-

ber 11 attacks, to which, he argues, TV response was frustratingly inadequate:

Reduced to a mere marker of a historical event, television was blinded by its

inherent inability to absorb and reproduce its totality, physically and emotion-

ally, reducing the attempt to convey the horror of the moment to the repetitive

presentation of spectacular images. (p. 131)

This repetition, he suggests, served as a compulsive deferral of meaning—the com-

pensatory and masking gesture of a news apparatus unable and unwilling to help citi-

zens make sense of an increasingly interdependent world. It is tempting to push the

insight one step further: repetition served as an agonizing stimulus that forestalled crit-

ical reflection while channeling a sense of benumbed outrage that came to pass for

clarity of purpose. In response to another automatically repeated observation—the

claim that the attacks “changed everything”—Hardt’s diagnosis suggests that on the

contrary, very little has changed when it comes to the ability of the mass media to serve

the interests of a democratic society during the most crucial of times. This perhaps

explains the urgency of Hardt’s manifesto and of its resuscitation of a call for a “com-

mitment to mass communication as a mode of public participation” (p. 89) rather than

as a purveyor of spectacle.

For those who have followed Hardt’s thoughtful and rigorous contributions to the

field, Myths for the Masses serves as both a rallying cry and think piece: a free-form

Downloaded from jci.sagepub.com at Claremont Colleges Library on October 25, 2014

280 Journal of Communication Inquiry

essay composed of reflections, observation, and analysis informed by a career’s worth

of close engagement with mass communication theory and history. Although his

assessment is not overly encouraging, the adoption of a manifesto format allows him

to unfold his critique against the background of the unfulfilled potential of an increas-

ingly powerful industry and the field of study it has both inspired and frustrated. The

result is a book that, in keeping with the critical tradition described by Lyon (1999),

“exposes the broken promises of modernity” (p. 3), but, at the same time, refuses to

give up on them.

Mark Andrejevic

University of Iowa

Reference

Lyon, J. (1999). Manifestoes: Provocations of the modern. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Downloaded from jci.sagepub.com at Claremont Colleges Library on October 25, 2014

You might also like

- Subliminal Seduction Public DeceptionDocument15 pagesSubliminal Seduction Public DeceptionBryan Paul Tumlad100% (1)

- Dragon AgeDocument2 pagesDragon Agegnob67No ratings yet

- Nietzsche, Artaud, and The Madman in Beckett's EndgameDocument9 pagesNietzsche, Artaud, and The Madman in Beckett's EndgamehorbgorblerNo ratings yet

- Dependency & Modernization TheoryDocument5 pagesDependency & Modernization TheoryMia SamNo ratings yet

- Theorizing CommunicationDocument296 pagesTheorizing Communicationcaracola1No ratings yet

- Ellet Joseph WaggonerDocument134 pagesEllet Joseph WaggonersifundochibiNo ratings yet

- Belly Up BookDocument20 pagesBelly Up BookY09 Zhao Jian (Louis) LEE0% (1)

- Profession Tax Challan - MaharashtraDocument1 pageProfession Tax Challan - MaharashtraPaymaster Services80% (5)

- Hall Ticket PDFDocument2 pagesHall Ticket PDFSachin KumarNo ratings yet

- Henry Jenkins Media Studies PDFDocument206 pagesHenry Jenkins Media Studies PDFFilozotaNo ratings yet

- Development Communication A Historical and Conceptual Overview PDFDocument21 pagesDevelopment Communication A Historical and Conceptual Overview PDFgrossuNo ratings yet

- Fake News - Definition PDFDocument12 pagesFake News - Definition PDFVic CajuraoNo ratings yet

- Fraser Nancy Rethinking The Public SphereDocument26 pagesFraser Nancy Rethinking The Public SphereDavidNo ratings yet

- Air Bag Launching SystemsDocument7 pagesAir Bag Launching SystemsJhon GreigNo ratings yet

- Al-Futuhat Al-Makkiyah The Preprints ofDocument1 pageAl-Futuhat Al-Makkiyah The Preprints ofabd al-shakurNo ratings yet

- Rhetoric, Culture, and Mass CommunicationDocument93 pagesRhetoric, Culture, and Mass Communicationrws_sdsuNo ratings yet

- Media and Left: Savaş ÇobanDocument26 pagesMedia and Left: Savaş ÇobanHarmain SaeedNo ratings yet

- 205 GRCM PP 1-33Document32 pages205 GRCM PP 1-33loveyourself200315No ratings yet

- Can Democracy Survive in The Post-Factual Age?: A Return To The Lippmann-Dewey Debate About The Politics of NewsDocument40 pagesCan Democracy Survive in The Post-Factual Age?: A Return To The Lippmann-Dewey Debate About The Politics of Newsbybee7207No ratings yet

- Can Democracy Survive in The Post-Factual Age?: A Return To The Lippmann-Dewey Debate About The Politics of NewsDocument40 pagesCan Democracy Survive in The Post-Factual Age?: A Return To The Lippmann-Dewey Debate About The Politics of Newsbybee7207No ratings yet

- Todd GuittlinDocument50 pagesTodd GuittlinJoanaNo ratings yet

- Facets of The Public SphereDocument25 pagesFacets of The Public SphereAndrea PérezNo ratings yet

- Leitura SilverstonemediationDocument38 pagesLeitura SilverstonemediationGustavo CardosoNo ratings yet

- The Media Its Reach Influence Reading Summary Copy 1Document5 pagesThe Media Its Reach Influence Reading Summary Copy 1koukiabattouyNo ratings yet

- Final Focus Draft 1Document24 pagesFinal Focus Draft 1api-667544558No ratings yet

- Downey2003 New Media, Counter Publicity and The Public SphereDocument19 pagesDowney2003 New Media, Counter Publicity and The Public SphereCicilia SinabaribaNo ratings yet

- 1.2 Call For PapersDocument8 pages1.2 Call For PapersPriyanka SinhaNo ratings yet

- Schiller, Theorizing CommunicationDocument296 pagesSchiller, Theorizing Communicationmaite.osorioNo ratings yet

- What Is Happening To News - Jack FullerDocument10 pagesWhat Is Happening To News - Jack FullerKarla Mancini GarridoNo ratings yet

- Libfile REPOSITORY Content Couldry, N Digital Storytelling, Media Research Couldry Digital Storytelling Media Research 2013Document37 pagesLibfile REPOSITORY Content Couldry, N Digital Storytelling, Media Research Couldry Digital Storytelling Media Research 2013feepivaNo ratings yet

- KomunikasiDocument28 pagesKomunikasimetha foraNo ratings yet

- The Just Use of Propaganda Ethical Criteria For Counter Hegemonic Communication StrategiesDocument23 pagesThe Just Use of Propaganda Ethical Criteria For Counter Hegemonic Communication StrategiesManish pandeyNo ratings yet

- Review of The Myth of The Liberal MediaDocument14 pagesReview of The Myth of The Liberal MediaMichael Drew Prior100% (1)

- Me y Rowitz 1997Document13 pagesMe y Rowitz 1997IvanNo ratings yet

- MECO1001 Assignment OneDocument6 pagesMECO1001 Assignment OneMichellee DangNo ratings yet

- Shaw Agenda-Setting and Mass Communication Theory PDFDocument11 pagesShaw Agenda-Setting and Mass Communication Theory PDFAlberto CastanedaNo ratings yet

- Sociology of CommunicationDocument18 pagesSociology of CommunicationJimena GalindezNo ratings yet

- How Propaganda Works in Modern SocietyDocument13 pagesHow Propaganda Works in Modern SocietyKevin SuryaNo ratings yet

- Fraser - Rethinking The Public SphereDocument26 pagesFraser - Rethinking The Public SpherePat PowerNo ratings yet

- Book Review Bourdieu and The Journalistic Field PDFDocument4 pagesBook Review Bourdieu and The Journalistic Field PDFAdi SulhardiNo ratings yet

- GitlinDocument50 pagesGitlinMariana SousaNo ratings yet

- Review of Mcquail'S Mass Communication Theory (6Th Ed.) : July 2014Document10 pagesReview of Mcquail'S Mass Communication Theory (6Th Ed.) : July 2014iusti iNo ratings yet

- 【blumer】沟通与民主:超越的危机和内在的发酵Document8 pages【blumer】沟通与民主:超越的危机和内在的发酵yi linNo ratings yet

- Jack FullerDocument9 pagesJack FullerLAURA OLIVOSNo ratings yet

- Challenging The Social Media Moral Panic: Preserving Free Expression Under HypertransparencyDocument16 pagesChallenging The Social Media Moral Panic: Preserving Free Expression Under HypertransparencyCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- 33 Problems With Media in One ChartDocument3 pages33 Problems With Media in One ChartMichael GDNo ratings yet

- 2014HybridMediaSystem TerbaruDocument4 pages2014HybridMediaSystem TerbaruPriyatna YudhaNo ratings yet

- Spreadable Media ReviewDocument3 pagesSpreadable Media ReviewTomas GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Reading Report EDITEDDocument3 pagesReading Report EDITEDeleanorattewell24No ratings yet

- Rethinking The SpectacleDocument20 pagesRethinking The SpectacleDENISE MAYE LUCERONo ratings yet

- Review and Critics of The Book: Manufacturing Consent: The Political-Economy of Mass MediaDocument17 pagesReview and Critics of The Book: Manufacturing Consent: The Political-Economy of Mass MediaAshutosh DohareyNo ratings yet

- Fraser RethinkingPublicSphere 1990Document26 pagesFraser RethinkingPublicSphere 1990dunkfor4No ratings yet

- Triple Contingency The Theoretical ProblDocument26 pagesTriple Contingency The Theoretical ProblCamilo Andrés FajardoNo ratings yet

- Media Serves The Interests of The StateDocument8 pagesMedia Serves The Interests of The StateSana BasheerNo ratings yet

- POLS20026 Take Home ExamDocument7 pagesPOLS20026 Take Home ExamGlynn AaronNo ratings yet

- WP 3Document7 pagesWP 3api-360683492No ratings yet

- Aethetics of NewsDocument11 pagesAethetics of NewsShawn AlexanderNo ratings yet

- Digital Public SphereDocument9 pagesDigital Public SphereLeslie KimNo ratings yet

- Osborn Peter Andrew 1997-2Document207 pagesOsborn Peter Andrew 1997-2pwdtx007No ratings yet

- Audience Perception and Influence - Marxism ApproachDocument4 pagesAudience Perception and Influence - Marxism ApproachShook AfNo ratings yet

- The Contemporary World Module 2 Lesson 1Document8 pagesThe Contemporary World Module 2 Lesson 1Aaron TitularNo ratings yet

- A Semiotic Analysis of Anti-Communism Political Cartoons, With Reference To Propaganda Model of Chomsky and HermanDocument12 pagesA Semiotic Analysis of Anti-Communism Political Cartoons, With Reference To Propaganda Model of Chomsky and HermanBint E HawaNo ratings yet

- Media and The Left Edited by Savaş ÇobanDocument198 pagesMedia and The Left Edited by Savaş ÇobanEvan Jack100% (1)

- WP 3Document7 pagesWP 3api-360683492No ratings yet

- Who Says What To Whom On TwitterDocument10 pagesWho Says What To Whom On TwitterAntonio Martínez VelázquezNo ratings yet

- Papacharissi-Virtual Sphere 2.0Document16 pagesPapacharissi-Virtual Sphere 2.0Marlo Israel AbsiNo ratings yet

- Powers of the Mind: Mental and Manual Labor in the Contemporary Political CrisisFrom EverandPowers of the Mind: Mental and Manual Labor in the Contemporary Political CrisisNo ratings yet

- Class 7 The Delhi Sultans (Question Bank)Document3 pagesClass 7 The Delhi Sultans (Question Bank)Rajeev VazhakkatNo ratings yet

- CE 437 - PDF 02 - Intro 02 - Steel - (Design of Steel Structure)Document13 pagesCE 437 - PDF 02 - Intro 02 - Steel - (Design of Steel Structure)Md Mufazzel Hossain ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Philconsa Vs EnriquezDocument3 pagesPhilconsa Vs Enriquezmarvinkho1978No ratings yet

- Identification, Storage, and Handling of Geosynthetic Rolls: Standard Guide ForDocument2 pagesIdentification, Storage, and Handling of Geosynthetic Rolls: Standard Guide ForN GANESAMOORTHYNo ratings yet

- A00 Upcwpr0040 UbDocument89 pagesA00 Upcwpr0040 UbRhoteram VikkuNo ratings yet

- 1863 Le Marchands Fortune TellerDocument204 pages1863 Le Marchands Fortune TellerMichael MaleedyNo ratings yet

- A Review of The Immoral Traffic Prevention Act, 1986 - Final EditDocument7 pagesA Review of The Immoral Traffic Prevention Act, 1986 - Final EditAmit SinghNo ratings yet

- Assigment HTML & PHP CNA PDFDocument61 pagesAssigment HTML & PHP CNA PDFSourav NayakNo ratings yet

- 1 - Steve Lockwood - Leanhealthcarep2i PPTX PDFDocument33 pages1 - Steve Lockwood - Leanhealthcarep2i PPTX PDFEmerson Rodrigo YuraNo ratings yet

- Managerial Economics Quiz 1Document5 pagesManagerial Economics Quiz 1edrianclydeNo ratings yet

- Hefei University Final Presentation PDFDocument27 pagesHefei University Final Presentation PDFBishal B.K.No ratings yet

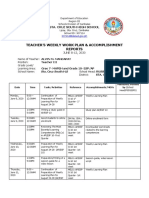

- Teacher'S Weekly Work Plan & Accomplishment Reports: Sta. Cruz South High SchoolDocument2 pagesTeacher'S Weekly Work Plan & Accomplishment Reports: Sta. Cruz South High SchoolAlvin Mas MandapatNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Economic ActivitiesDocument3 pagesUnit 2 Economic Activitiesnotkingit68No ratings yet

- 21ST Century Literature Week1Document13 pages21ST Century Literature Week1Justine Mae AlveroNo ratings yet

- Criminal Jurisdiction in EthiopiaDocument47 pagesCriminal Jurisdiction in EthiopiaBooruuNo ratings yet

- Experiment 8 Universal MotorDocument9 pagesExperiment 8 Universal MotorJ Arnold SamsonNo ratings yet

- Activity 6 (Harvesting)Document17 pagesActivity 6 (Harvesting)Arnel SisonNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Student Learning 1 - Different Types of AssessmentDocument5 pagesAssessment of Student Learning 1 - Different Types of AssessmentRuby Corazon EdizaNo ratings yet

- IP BBA Mock 2Document12 pagesIP BBA Mock 2kalrajanvi55No ratings yet

- Journal Pre-Proof: Finance Research LettersDocument18 pagesJournal Pre-Proof: Finance Research LettersAshraf KhanNo ratings yet

- Pentatonix A Christmas SpectacularDocument1 pagePentatonix A Christmas SpectacularHorváth EndreNo ratings yet

- Carta Del Departamento Del Trabajo Estatal Al FederalDocument3 pagesCarta Del Departamento Del Trabajo Estatal Al FederalEl Nuevo DíaNo ratings yet