Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Infant and Child Mortality

Uploaded by

IndRa KaBhuomCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Infant and Child Mortality

Uploaded by

IndRa KaBhuomCopyright:

Available Formats

INFANT AND CHILD MORTALITY 8

Macleod W. Mwale

This chapter reports on levels, trends, and differentials in infant and child mortality based on

the 2004 MDHS. The information on infant and child mortality is relevant to evaluating the pro-

gress of health programmes and in monitoring the current demographic situation. In addition, the

data can be used to identify subgroups of the population that have high mortality risks.

The data for the calculation of mortality rates are collected in the reproduction section of the

Women’s Questionnaire. The section begins with aggregate questions about the total number of

sons and daughters who live with the mother, the number who live elsewhere, and the number who

have died. Then a detailed birth history is administered. For each live birth, information is obtained

on the child’s name, date of birth, sex, whether the birth was single or multiple, and survivorship

status. For living children, information about his or her age at last birthday and whether the child

resides with his or her mother is obtained. For children who had died, the respondent is asked to

provide the age at death.

8.1 DEFINITIONS

The mortality rates presented in this report are defined as follows:

Neonatal mortality (NN): the probability of dying within the first month of life

Postneonatal mortality PNN): the difference between infant and neonatal mortality

Infant mortality (1q0): the probability of dying before the first birthday

Child mortality (4q1): the probability of dying between the first and the fifth

birthday

Under-five mortality (5q0): the probability of dying between birth and the

fifth birthday

All rates are expressed per 1,000 live births, except for child mortality, which is expressed per

1,000 children surviving to 12 months of age.

Population censuses and demographic surveys are the major sources of mortality data in Ma-

lawi, as in most developing countries. Vital registration is another potential source of mortality data.

In Malawi, however, the vital registration data are incomplete in coverage and unrepresentative of

the population. Mortality data from the Health Management Information System (HMIS) is not a

suitable basis for the calculation of mortality rates from a population perspective because the system

is facility-based and does not include data on deaths that occur outside the facilities. Given these cir-

cumstances, birth history data from surveys provide the most reliable estimates of infant and child

mortality for Malawi.

Infant and Child Mortality | 123

8.2 METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The DHS surveys estimate mortality rates for specific time periods preceding the survey,

typically five-year periods, i.e., 0-4 years, 5-9 years, and so on. The estimates are based on births and

infant and child deaths reported by women age 15-49 as of the interview date. Inherent in this

methodology are possible biases arising from incomplete and possibly unrepresentative data.

Since only surviving women age 15-49 are interviewed, no data are available for the children

of women who have died. In this case, mortality estimates will be biased if the mortality experience

of children born to surviving and nonsurviving women differs. Of course, any method of estimating

childhood mortality rates that relies on retrospective reporting of events by mothers is susceptible to

bias from this source. The higher the level of adult female mortality and the longer ago the time pe-

riods for which mortality is estimated, the greater is the potential for bias.

Another methodological constraint arises from the fact that women older than age 49 at the

time of the survey are not interviewed and thus cannot contribute information on the exposure and

deaths of their children for periods preceding the survey. This censoring of information and the re-

sulting potential for bias becomes more severe as mortality estimates are made for time periods more

distant prior to the survey. To reduce the effect of these methodological limitations, estimation of

infant and child mortality in this report is restricted to the period 15 years prior to the survey.

8.3 ASSESSMENT OF DATA QUALITY

Potential data collection problems include misreporting dates of birth, misreporting age at

death, and underreporting of events. It is possible to test the birth history data collected in the 2004

MDHS for these kinds of errors. The testing involves checking the internal consistency of the col-

lected data, essentially determining if the data conform to expected patterns.

8.3.1 Misreporting Dates of Birth

The 2004 MDHS Women’s Questionnaire includes two sections on maternal and child

health, in which data are collected on antenatal, delivery, and postnatal care of the mother for recent

births and on many health and nutrition issues for these children (see Chapters 9 and 10). These sec-

tions of the questionnaire must be administered for each birth which occurs after some cut-off date,

typically set to January of the fifth calendar year prior to a survey. In the case of the 2004 MDHS,

the cut-off date was January 1999.

Interviewers in DHS surveys can lessen their workload by recording births that actually occur

after the cut-off date as occurring before that date. This type of birth transference occurs in many

DHS surveys. In the case of the 2004 MDHS, the occurrence of birth transference can be detected

by inspecting the reported number of births in each calendar year before and after the cut-off date

for the health sections. Appendix Table C.4 shows the relevant data. Substantial misreporting of

dates of birth is evident in terms of the calendar year pattern of reported events: 1,575 total births

for 1999 and 2,143 births for 1998 (an increase of 36 percent). Misreporting of dates of birth for

nonsurviving children is even more severe: 233 for 1999 and 424 for 1998 (an increase of 82 per-

cent).

In terms of mortality analysis, what is important is the extent to which this birth transference

distorts the time period in which child deaths occur. To the extent that birth transference results in a

124 | Infant and Child Mortality

shortfall of deaths in the five-year period prior to the survey, the time trend of mortality estimates

will be distorted; mortality rates for the most recent five years before the survey will tend to be un-

derestimated, while the estimates for the earlier five-year period will tend be overestimated. This is

1

the case with the MDHS 2004.

8.3.2 Misreporting Age at Death

Misreporting age at death can distort the age pattern of mortality. Of particular concern is

the rounding of reported ages at death so that some deaths which actually occur in late infancy are

reported as deaths at one year of age. This type of misreporting would tend to underestimate infant

mortality rates and overestimate child mortality rates. To avoid this problem, interviewers in DHS

surveys are instructed to collect age-at-death data in terms of months of age for children that die af-

ter the first month of life but before two years of age. If a respondent reports the age at death as age

one, the interviewer must probe to determine the number of months that the child lived, being par-

ticularly careful to determine if the child died before or after the first birthday. This procedure of

data collection is designed to minimise the misreporting of age at death and, if digit preference oc-

curs in reported ages at death, it will be obvious from a frequency distribution of deaths by age in

months.

Appendix Table C.6 shows reported deaths by age at death in months (0 through 23 months

of age) and the number of deaths reported as occurring at age one year.2 For the 15-year period im-

mediately preceding the 2004 MDHS, the number of deaths reported at one year of age (422) ex-

ceeds the total number reported at 12 through 23 months of age (403), indicating that interviewers

did not follow standard DHS procedures and making it impossible to assess age at death misreport-

ing by inspection of the distribution of deaths by months of age.

However, the possibility of misreporting late infant deaths as deaths at one year of age can be

indirectly assessed by comparison of the pattern of mortality between the first and the fifth birthday

from the three DHS surveys conducted in Malawi (1992, 2000, and 2004). In each of the three sur-

veys, the age pattern of mortality is similar, with infant mortality rates exceeding child mortality rates

by between 10 and 24 percent. The absence of a significant change in the age pattern of mortality

over the three surveys suggests that, relative to the earlier surveys, substantial age at death misreport-

ing did not occur in the 2004 MDHS.

8.3.3 Underreporting of Deceased Children

Underreporting of the births of deceased children (and their subsequent deaths) is always a

concern when collecting birth histories of women. The women may not wish to report such sad

events, and interviewers may fail to record some of these events for the five-year period preceding the

survey in order to avoid asking questions contained in the maternal and child health sections of the

questionnaire.

When there is underreporting of births of deceased children, it is usually most pronounced

in early infancy. If there is severe underreporting of neonatal deaths, the result would be an unusu-

1

The extent to which the time trend of mortality is distorted by birth transference could be investigated by more detailed

analysis.

2

The number of deaths at one year of age should be minimal in DHS surveys because of the DHS procedure of probing

to determine age at deaths in months when a respondent initially reports one year as the age at death.

Infant and Child Mortality | 125

ally low ratio of neonatal deaths to all infant deaths. Appendix Table C.6 indicates that the percent-

age of neonatal deaths relative to all infant deaths was lower in the five-year period immediately pre-

ceding the survey (39 percent) than in the periods 5-9 years (43 percent) and 10-14 years preceding

the survey (42 percent). These differences are not great, but the pattern is consistent with the under-

reporting of deceased children in the five-year period immediately preceding the survey. This is espe-

cially curious since the low ratio occurs in a time period of falling infant mortality, when neonatal

mortality is expected to be a greater component of infant mortality.

The assessment of data quality has found that standard DHS procedures were not followed

in the collection of age-at-death data; that birth dates were misreported (especially in the case of

non-surviving children), resulting in the transference of births out of the five-year period immedi-

ately preceding the survey; and that the ratio of neonatal to infant mortality is unexpectedly lower

for the five-years preceding the survey than for earlier time periods. For these reasons the mortality

estimates from the 2004 MDHS must be interpreted with caution.

8.4 LEVELS AND TRENDS OF EARLY CHILDHOOD MORTALITY

Table 8.1 presents estimates of childhood mortality for three five-year periods preceding the

survey. For the most recent five-year period, corresponding approximately to 2000-2004, the infant

mortality rate was 76 per 1,000 live births, and child mortality was 62 per 1,000, resulting in an

overall under-five mortality rate of 133 per 1,000 live births.

During the 15-year period preceding the survey, the estimates indicate that under-five mor-

tality has declined by 30 percent (from 190 deaths per 1,000 to 133 per 1,000). Infant mortality de-

clined by 27 percent (from 104 per 1,000 to 76 per 1,000). Neonatal mortality, however, declined

by 36 percent (from 42 per 1,000 to 27 per 1,000).

Table 8.1 Early childhood mortality rates

Neonatal, postneonatal, infant, child, and under-five mortality rates for five-year periods preceding the

survey, Malawi 2004

Years Approximate Neonatal Postneonatal Infant Child Under-five

preceding calendar mortality mortality mortality mortality mortality

the survey period (NN)1 (PNN) (1q0) (4q1) (5q0)

0-4 2000-2004 27 49 76 62 133

5-9 1995-1999 49 64 112 84 187

10-14 1990-1994 42 62 104 96 190

1

Computed as the difference between the infant and neonatal mortality rates

The fact that the largest age-specific decline in mortality occurs in the neonatal period is in-

consistent with the pattern of decline usually observed in developing countries. The usual pattern is

greater decline in postneonatal mortality and child mortality than in neonatal mortality, because

some of the causes of neonatal mortality (preterm delivery, injury at delivery, and congenital mal-

formations) are the last to be alleviated in a developing country. Thus it is possible that births ending

in neonatal deaths were underreported for the period immediately preceding the survey, as is sug-

gested in the data quality assessment in Section 8.3.3.

126 | Infant and Child Mortality

There are many causes of childhood mortality in the developing world, and their impact var-

ies from one country to another. Similarly, increases and decreases in mortality for different age

groups from infancy through early childhood can be a result of many factors. A detailed analysis of

these factors is beyond the scope of this report, however, looking at the three MDHS surveys (1992,

2000, and 2004), it is apparent there has been little change in the factors typically associated with

deceases in neonatal mortality. Among women giving birth in the five years preceding each survey,

the percentage receiving antenatal care from a doctor or nurse/midwife was about the same (90, 91

and 93 percent, respectively), the percentage receiving tetanus toxoid during pregnancy was un-

changed (85 percent in all three surveys), and the proportion of deliveries assisted by a doctor or

nurse/midwife changed little (55, 56, and 57 percent) (see Chapter 9).

8.5 SOCIOECONOMIC DIFFERENTIALS IN CHILDHOOD MORTALITY

The 2004 MDHS data allows the estimation of mortality levels by socioeconomic indicators

(Table 8.2). A ten-year period (approximately 1995-2004) is used to calculate the mortality esti-

mates in order to reduce the sampling variability for the subclasses of the indicators.

Urban mortality rates are generally lower than rural rates; the under-five mortality rate is 116

per 1,000 in urban areas compared to 164 per 1,000 in rural areas. Comparing the three regions, the

Northern Region has lower under-five mortality (120 per 1,000 live births), than either the Central

(162 per 1,000) or the Southern Regions (164 per 1,000). Similarly, the infant mortality rate is low-

est in the Northern Region (82 per 1,000), compared with either the Central Region (90 per 1,000)

or the Southern Regions (98 per 1,000). These regional differences in mortality were also observed

in the 1992 MDHS and the 2000 MDHS.

Table 8.2 also presents childhood mortality rates for 10 oversampled districts. Under-five

mortality is lowest in Mzimba (112 per 1,000) and Machinga (130 per 1,000) and is highest in Mu-

lanje (221 per 1,000), Kasungu (192 per 1,000), and Thyolo (187 per 1,000). For infant mortality,

the lowest rates are found in Lilongwe (73 per 1,000) and Machinga (78 per 1,000), while the high-

est rates are also observed in Mulanje (145 per 1,000), Thyolo (119 per 1,000), and Kasungu (117

per 1,000).

The 2004 MDHS shows the same relationship between mother’s education and child sur-

vival as the 2000 MDHS. For every age interval, higher levels of education are generally strongly as-

sociated with lower mortality risks. The same is true for the wealth index.

Infant and Child Mortality | 127

Table 8.2 Early childhood mortality rates by background characteristics

Neonatal, postneonatal, infant, child, and under-five mortality rates for the 10-year period

preceding the survey, by background characteristic, Malawi 2004

Neonatal Postneonatal Infant Child Under-five

Background mortality mortality mortality mortality mortality

characteristic (NN) (PNN)1 (1q0) (4q1) (5q0)

Residence

Urban 22 38 60 60 116

Rural 39 59 98 74 164

Region

Northern 39 44 82 41 120

Central 34 56 90 80 162

Southern 39 59 98 73 164

District

Blantyre 46 43 90 69 153

Kasungu 56 61 117 85 192

Machinga 33 45 78 57 130

Mangochi 45 59 104 70 167

Mzimba 38 41 80 36 112

Salima 25 59 84 76 154

Thyolo 43 76 119 77 187

Zomba 31 53 84 66 144

Lilongwe 21 52 73 78 145

Mulanje 55 89 145 89 221

Other districts 36 55 91 74 158

Education

No education 36 65 101 89 181

Primary 1-4 39 61 101 77 170

Primary 5-8 38 46 85 59 139

Secondary+ 25 38 63 25 86

Wealth quintile

Lowest 36 73 109 83 183

Second 41 58 100 79 171

Middle 40 55 95 82 168

Fourth 36 54 89 62 146

Highest 29 37 66 49 111

1

Computed as the difference between the infant and neonatal mortality rates

8.6 BIODEMOGRAPHIC DIFFERENTIALS IN CHILDHOOD MORTALITY

This section looks at the association between biodemographic factors and childhood mortal-

ity levels (Table 8.3). With the exception of the mother’s perception of birth size, mortality rates are

presented for the ten-year period preceding the survey.

As is the case in most populations, male children are more likely to die before reaching the

age of five (166 per 1,000 live births) than female children (149 per 1,000).

The mother’s age at birth is also associated with a child’s chances of survival. Children born

to younger mothers (under 20 years of age) and older mothers (40 years and older) have higher mor-

128 | Infant and Child Mortality

tality than children born to mothers in the middle reproductive years (ages 20-39). Children of

mothers under age of 20 are especially vulnerable, particularly in the first month of life. Neonatal

mortality is 56 deaths per 1,000 among children of teenage mothers, compared with 29 per 1,000

among children of women age 20-29.

There is a strong association between the length of the preceding birth interval and mortal-

ity. Under-five mortality of children born following a short birth interval (less than two years) is 67

percent greater than for children born after an interval of 2 years and 162 percent greater than for

children born after an interval of 4 years. This relative mortality disadvantage of children born after a

short birth interval is even more pronounced during the neonatal period.

In the 2004 MDHS, mothers were also asked their perception of the size of their child at

birth for births occurring in the five years preceding the survey. The findings indicate children per-

ceived by their mothers to be small or very small were much more likely to die in the first year of life

(121 per 1,000 live births) than those perceived as average or large in size (65 per 1,000 live births).

Table 8.3 Early childhood mortality rates by demographic characteristics

Neonatal, postneonatal, infant, child, and under-five mortality rates for the 10-year

period preceding the survey, by demographic characteristics, Malawi 2004

Neonatal Postneonatal Infant Child Under-five

Demographic mortality mortality mortality mortality mortality

characteristic (NN) (PNN)1 (1q0) (4q1) (5q0)

Child's sex

Male 42 55 97 76 166

Female 32 56 88 67 149

Mother's age at birth

<20 56 66 121 78 190

20-29 29 53 82 72 148

30-39 34 54 88 63 145

40-49 48 44 92 76 161

Birth order

1 47 61 108 72 172

2-3 33 53 87 71 151

4-6 26 52 78 69 141

7+ 51 63 114 80 185

Previous birth interval2

<2 years 62 92 154 112 249

2 years 31 54 85 70 149

3 years 22 34 56 57 110

4+ years 20 35 55 43 95

Birth size3

Small/very small 52 69 121 na na

Average or larger 21 44 65 na na

na = Not applicable

1

Computed as the difference between the infant and neonatal mortality rates

2

Excludes first-order births

3

Rates for the five-year period before the survey

Infant and Child Mortality | 129

8.7 CHILDHOOD MORTALITY BY WOMEN’S STATUS

The ability to access information, make decisions, and act effectively in their own interest, or

the interest of those who depend on them, are essential aspects of women’s empowerment. If

women, the primary caretakers of children, are empowered, the health and survival of their infants is

likely to be enhanced. Table 8.4 shows infant and child mortality rates in relation to women’s status

as measured by three empowerment indicators: participation in household decisionmaking, attitude

towards a woman being able to refuse to have sex with her husband, and attitude towards wife beat-

ing.

There is no consistent relationship between levels of mortality and the first two empower-

ment indicators: participation in household decisionmaking and number of reasons justifying a

woman’s refusal to have sex with her husband. However, there does appear to be a relationship in

the case of attitude towards wife beating. For example, among women reporting fewer reasons justi-

fying wife beating (i.e., more empowered women) under-five mortality is lower (approximately 150

per 1,000) than among women reporting more reasons justifying wife beating (approximately 180

per 1,000).

Table 8.4 Early childhood mortality rates by women's status

Neonatal, postneonatal, infant, child, and under-five mortality rates for the 10-year period preced-

ing the survey, by women's status indicators, Malawi 2004

Neonatal Postneonatal Infant Child Under-five

Women's status mortality mortality mortality mortality mortality

indicators (NN) (PNN)1 (1q0) (4q1) (5q0)

Number of decisions in which

woman has final say2

0 38 51 89 75 158

1-2 36 59 95 79 166

3-4 37 48 85 58 138

5 38 61 99 68 160

Number of reasons to refuse

sex with husband

0 28 57 85 79 157

1-2 33 61 94 75 162

3-4 39 54 93 70 157

Number of reasons wife beat-

ing is justified

0 36 56 92 71 156

1-2 39 49 89 66 149

3-4 37 69 106 78 176

5 37 61 98 95 184

1

Computed as the difference between the infant and neonatal mortality rates

2

Either by herself or jointly with others

130 | Infant and Child Mortality

8.8 PERINATAL MORTALITY

The 2004 MDHS survey also asked Table 8.5 Perinatal mortality

women to report on their pregnancy losses in Number of stillbirths and early neonatal deaths, and the perinatal mortal-

the five-year period preceding the survey and ity rate (per 1,000 pregnancies) for the five-year period preceding the

survey, by background characteristics, Malawi 2004

the gestational age of each lost pregnancy. In

Number of Number of

this report, perinatal deaths include pregnancy Number early Perinatal pregnancies of

losses occurring after seven completed months Background of neonatal mortality 7+ months

characteristic stillbirths1 deaths2 rate3 duration

of gestation (stillbirths) and deaths to live Mother's age at

births less than seven days old (early neonatal birth

<20 45 63 48 2,249

deaths). The perinatal mortality rate is the sum 20-29 73 91 28 5,963

30-39 39 42 35 2,293

of the number of stillbirths and early neonatal 40-49 11 8 (43) 434

deaths divided by the number of pregnancies Previous pregnancy

interval

reaching seven months’ gestation. The causes in months

of stillbirths and early neonatal deaths overlap, First pregnancy 51 62 46 2,465

<15 7 12 (47) 390

and examining just one or the other can un- 15-26 38 53 45 2,028

27-38 33 36 24 2,902

derstate the true level of mortality around de- 39+ 38 42 25 3,155

livery. For this reason, stillbirths and early Residence

Urban 9 13 15 1,434

neonatal mortality are combined and examined Rural 159 191 37 9,505

together. Region

Northern 24 31 40 1,369

Central 72 75 32 4,566

Table 8.5 shows the number of still- Southern 72 99 34 5,005

births, the number of early neonatal deaths, District

Blantyre 7 12 26 731

and the perinatal mortality rates for the five- Kasungu 10 15 48 536

year period preceding the survey by back- Machinga 7 11 39 447

Mangochi 12 15 42 648

ground characteristics. The perinatal mortality Mzimba 10 16 39 686

Salima 4 4 25 316

rate is 34 per 1,000. This is lower than the rate Thyolo 7 12 33 582

Zomba 7 14 39 552

measured in the 2000 MDHS (46 per 1,000). Lilongwe 12 11 15 1,501

Mulanje 7 16 50 444

Other districts 84 78 36 4,498

By demographic characteristics, there is

Education

a clear pattern of elevated perinatal mortality No education 48 46 32 2,951

Primary 1-4 63 59 39 3,165

among women younger than 20 and 40 and Secondary 5-8 47 79 34 3,685

older. First pregnancies and pregnancies with a Secondary + 9 20 26 1,136

short preceding interpregnancy interval are Wealth quintile

Lowest 28 23 24 2,127

also at an elevated risk of perinatal mortality. Second 59 52 45 2,485

Middle 31 56 35 2,477

First pregnancies and pregnancies with an in- Fourth 25 47 34 2,116

Highest 26 26 30 1,735

terpregnancy interval of less than 27 months

Total 168 204 34 10,939

have a perinatal risk of approximate 46 per

1,000, as opposed to a risk of approximately Note: Rates in parentheses are based on 250-499 pregnancies

1

Stillbirths are fetal deaths in pregnancies lasting seven or more months.

25 per 1,000 when the interpregnancy interval 2

Early neonatal deaths are deaths at age 0-6 days among live-born chil-

dren.

is 27 months or longer. 3

The sum of the number of stillbirths and early neonatal deaths dvided

by the number of pregnancies of seven or more months’ duration.

Differences in perinatal mortality by

urban-rural residence are substantial. The urban perinatal mortality rate (15 per 1,000) is less than

half that of the rural rate (37 per 1,000). Differences by district range from 15 per 1,000 (Lilongwe)

to 40 per 1,000 (Mulange). Differences by region and mother’s characteristics are much less pro-

nounced.

Infant and Child Mortality | 131

8.9 HIGH-RISK FERTILITY BEHAVIOUR

Numerous studies have demonstrated a strong relationship between a woman’s pattern of

fertility and her children’s survival. Table 8.6 shows the distribution of children born in the five

years preceding the survey (approximately calendar years 2000-2004) by category of increased risk of

dying due to the woman’s fertility behaviour, i.e., in terms of being relatively young or relatively old

at the time of birth (less than age 18 or age 35 or older), having a high birth order (birth order 4 or

higher), or having a short preceding birth interval (less than 24 months).

Column one of Table 8.6 Table 8.6 High-risk fertility behaviour

shows the percentage of births during Percent distribution of children born in the five years preceding the survey by

the five years before the survey that fall category of elevated risk of mortality and the risk ratio, and percent distribution

of currently married women by category of risk if they were to conceive a child

into various risk categories. More than at the time of the survey, Malawi 2004

half of all births (53 percent) fall into a

Births in the 5 years Percentage of

single or multiple high-risk category, preceding the survey currently

with 16 percent falling into a multiple Percentage Risk married

Risk category of births ratio women1

high-risk category.

Not in any high-risk category 30.0 1.00 25.1a

The risk ratios for categories of Unavoidable risk category

First order births between ages

births in the last five years are pre- 18 and 34 years 16.8 1.21 6.0

sented in column two: the risk ratio is Single high-risk category

the ratio of the proportion dead among Mother's age <18 7.2 1.76 0.9

Mother's age >34 0.3 (0.94) 2.1

live births in a specific high-risk cate- Birth interval <24 months 5.3 1.49 12.9

gory to the proportion dead among Birth order >3 24.1 0.97 17.9

births not in any high-risk category. Subtotal 36.9 1.20 33.9

Multiple high-risk category

Two points merit comment. First, in Age <18 & birth interval

Malawi, high birth order as a single- <24 months2 0.4 3.45 0.4

Age >34 & birth interval

risk factor is not associated with higher <24 months 0.0 na 0.0

mortality risk. The only single high- Age >34 & birth order >3 10.1 0.90 16.9

Age >34 & birth interval

risk factors leading to heightened mor- <24 months & birth order >3 1.2 2.95 4.8

tality risk are young age at birth and Birth interval <24 months and

birth order >3 4.5 2.12 13.0

short birth interval. Second, short birth

Subtotal 16.2 1.46 35.0

interval coupled with another high-risk

In any avoidable high-risk

factor always results in a risk ratio in category 53.2 1.28 68.9

excess of 2.0. This latter finding under- Total 100.0 na 100.0

scores the need to reduce, through Number of births 10,773 na 8,312

greater use of contraception, the num- Note: Risk ratio is the ratio of the proportion dead among births in a specific

ber of closely spaced births in Malawi. high-risk category to the proportion dead among births not in any high-risk

category.

Figures in parentheses are based on 25-49 unweighted cases.

Column three of Table 8.6 in- na = Not applicable

1

Women are assigned to risk categories according to the status they would

dicates the potential for high-risk have at the birth of a child if they were to conceive at the time of the survey:

births among currently married, non- current age less than 17 years and 3 months or older than 34 years and 2

months, latest birth less than 15 months ago, or latest birth being of order 3 or

sterilised women at the time of the sur- higher.

vey. The table shows the distribution 2

a

Includes the category age <18 and birth order >3

Includes sterilised women

of risk categories into which a birth

would fall if all of these women con-

ceived at the time of the survey. Thirty-five percent of married women have the potential to give

birth to a child that falls into a multiple high-risk category.

132 | Infant and Child Mortality

You might also like

- Infant and Child Mortality Rates Decline in PhilippinesDocument10 pagesInfant and Child Mortality Rates Decline in PhilippinesIrwin FajaritoNo ratings yet

- Infant Mortality in Modern EgyptDocument10 pagesInfant Mortality in Modern Egypttrevisani-andreaNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Related Mortality in The United States,.11Document8 pagesPregnancy Related Mortality in The United States,.11melisaberlianNo ratings yet

- Miscarriage in India: A Population-Based Study: Tervals, Because It Was Not Possible From The Data Set ToDocument3 pagesMiscarriage in India: A Population-Based Study: Tervals, Because It Was Not Possible From The Data Set ToMutianaUmminyaKhanzaNo ratings yet

- Motherhood in Childhood The Untold Story Supplementary Material - ENDocument71 pagesMotherhood in Childhood The Untold Story Supplementary Material - ENWalter MendozaNo ratings yet

- Perinatal Mortality HUKMDocument8 pagesPerinatal Mortality HUKMMuvenn KannanNo ratings yet

- HCI VS2004Report PDFDocument152 pagesHCI VS2004Report PDFjc75aNo ratings yet

- Fatality Child ABuse and Its Relation To CMRDocument10 pagesFatality Child ABuse and Its Relation To CMRGemoSatnovanNo ratings yet

- Maternal Mortality Ratio - Trends in The Vital Registration DataDocument4 pagesMaternal Mortality Ratio - Trends in The Vital Registration DataadskvcdsNo ratings yet

- Declining Child Mortality in Northern Malawi Despite High Rates of Infection With The HIVDocument18 pagesDeclining Child Mortality in Northern Malawi Despite High Rates of Infection With The HIVFeronika TerokNo ratings yet

- 0102 311X CSP 30 s1 0182 PDFDocument10 pages0102 311X CSP 30 s1 0182 PDFAna Gabriela ResendeNo ratings yet

- Katherine J Gold Sheila M Marcus: Table 1Document4 pagesKatherine J Gold Sheila M Marcus: Table 1angelie21No ratings yet

- NeonatalDocument5 pagesNeonatalRia Iea OhorellaNo ratings yet

- Medical Jurisprudence ProjectDocument11 pagesMedical Jurisprudence ProjectUtkarshini VermaNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Birth Defects and Risk-Factor Analysis From A Population-Based Survey in Inner Mongolia, ChinaDocument6 pagesPrevalence of Birth Defects and Risk-Factor Analysis From A Population-Based Survey in Inner Mongolia, ChinaAndiTiwsNo ratings yet

- Module 3 ReviDocument35 pagesModule 3 ReviJohn Van Dave TaturoNo ratings yet

- Arsyad: Kedua: Perbedaan Yang KetigaDocument12 pagesArsyad: Kedua: Perbedaan Yang KetigaSidik PurwantoNo ratings yet

- Professional Analytical ReportDocument5 pagesProfessional Analytical Reportstrwberi8No ratings yet

- Health 634 e Portfolio 3 Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesHealth 634 e Portfolio 3 Literature Reviewapi-370740412No ratings yet

- Bayesian Analysis of Infant Mortality in Oyo State, NigeriaDocument6 pagesBayesian Analysis of Infant Mortality in Oyo State, NigeriaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Jurnal IKKOMDocument10 pagesJurnal IKKOMJelnathleeNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Infant Mortality RateDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On Infant Mortality Rateaflsjfmwh100% (1)

- La Edad de La Mujer Como Factor de Riesgo de Mortalidad Materna, Fetal, Neonatal e InfantilDocument7 pagesLa Edad de La Mujer Como Factor de Riesgo de Mortalidad Materna, Fetal, Neonatal e InfantilRAMIRO YUJRANo ratings yet

- Unintended Pregnancy in The United States: Incidence and Disparities, 2006Document23 pagesUnintended Pregnancy in The United States: Incidence and Disparities, 2006Mokhamad AuliaNo ratings yet

- Women's Health-What's New Worldwide: International Guidelines, Patents and TrialsDocument3 pagesWomen's Health-What's New Worldwide: International Guidelines, Patents and TrialsGladstone AsadNo ratings yet

- Khan 2020 Ic 200031Document3 pagesKhan 2020 Ic 200031Lezard DomiNo ratings yet

- Under-Reporting of Gravidity in A Rural Malawian PopulationDocument3 pagesUnder-Reporting of Gravidity in A Rural Malawian PopulationMisirihNo ratings yet

- HHS Public AccessDocument18 pagesHHS Public AccessNur HikmaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal ObgynDocument10 pagesJurnal ObgynUgi RahulNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Mortality in Ethiopia: Trends and Determinants: Researcharticle Open AccessDocument14 pagesNeonatal Mortality in Ethiopia: Trends and Determinants: Researcharticle Open AccessrahmaNo ratings yet

- Limos - JournalDocument2 pagesLimos - JournalClaire LimosNo ratings yet

- Yang Honein 2006 Birth Defects Research Part A Clinical and Molecular TeratologyDocument8 pagesYang Honein 2006 Birth Defects Research Part A Clinical and Molecular TeratologyLívia MészárosNo ratings yet

- Human Sexuality and Adolescence: Public HealthDocument2 pagesHuman Sexuality and Adolescence: Public HealthpipitingesNo ratings yet

- Philippine Government Policies On Maternal, Newborn and Child Health and NutritionDocument20 pagesPhilippine Government Policies On Maternal, Newborn and Child Health and Nutritioncarlos-tulali-1309100% (33)

- Ali F. Abdlhasan Department of Pediatric Nursing, University Ahi Evran Student ID:201217154 Dr. Professor HİLAL SEKİ ÖZDocument9 pagesAli F. Abdlhasan Department of Pediatric Nursing, University Ahi Evran Student ID:201217154 Dr. Professor HİLAL SEKİ ÖZAli FalihNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Characteristics of Children With Cerebral Palsy in EuropeDocument8 pagesPrevalence and Characteristics of Children With Cerebral Palsy in EuropeFachry MuhammadNo ratings yet

- The Worldwide Incidence of Preterm Birth: A Systematic Review of Maternal Mortality and MorbidityDocument8 pagesThe Worldwide Incidence of Preterm Birth: A Systematic Review of Maternal Mortality and MorbidityAnalia ZeinNo ratings yet

- Asfr TF MacDocument4 pagesAsfr TF Mactimson segunNo ratings yet

- Maternal Death ReviewsDocument4 pagesMaternal Death ReviewsJosephine AikpitanyiNo ratings yet

- Hertz PicciottoDelwiche 2008HLDocument7 pagesHertz PicciottoDelwiche 2008HLAnna RalphNo ratings yet

- CDC Report On Infant Mortality RatesDocument8 pagesCDC Report On Infant Mortality RatesEmma KoryntaNo ratings yet

- 4million NeonatalDocument13 pages4million NeonatalsylvetriNo ratings yet

- HCI VS2003Report PDFDocument152 pagesHCI VS2003Report PDFjc75aNo ratings yet

- Accuracy of reported ages in 2008-09 Kenya Demographic and Health SurveyDocument3 pagesAccuracy of reported ages in 2008-09 Kenya Demographic and Health SurveyFatima SarwarNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Effect of Birth and Death Registration On Health Service Delivery (A Case of Tolon District of Ghana)Document10 pagesEvaluation of The Effect of Birth and Death Registration On Health Service Delivery (A Case of Tolon District of Ghana)Igbani VictoryNo ratings yet

- 0039 0162 PDFDocument124 pages0039 0162 PDFAnamaria JurcaNo ratings yet

- Induced Abortion and Risks That May Impact AdolescentsDocument29 pagesInduced Abortion and Risks That May Impact AdolescentsMichael RezaNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Estimating Maternal Mortality Level in Rural Northern Nigeria by The Sisterhood MethodDocument6 pagesResearch Article: Estimating Maternal Mortality Level in Rural Northern Nigeria by The Sisterhood MethodFhasya Aditya PutraNo ratings yet

- Why Aren't There More Maternal Deaths? A Decomposition AnalysisDocument8 pagesWhy Aren't There More Maternal Deaths? A Decomposition AnalysisFuturesGroup1No ratings yet

- Multiparity FinalDocument4 pagesMultiparity FinalUkwuma Michael ChijiokeNo ratings yet

- Health & Early Marriages in Rural MalawiDocument5 pagesHealth & Early Marriages in Rural MalawiCridoc DocumentationNo ratings yet

- Nursing Research PaperDocument19 pagesNursing Research Paperapi-401771498No ratings yet

- NICHD calculator predicts outcomes for extremely preterm infantsDocument5 pagesNICHD calculator predicts outcomes for extremely preterm infantsMarce FloresNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Cesarean Delivery Rate and Maternal and Neonatal MortalityDocument8 pagesRelationship Between Cesarean Delivery Rate and Maternal and Neonatal MortalityJenny YenNo ratings yet

- PLOSMedicine Article Plme 08 08 OestergaardDocument14 pagesPLOSMedicine Article Plme 08 08 OestergaarddibosaurioNo ratings yet

- Sids BabyDocument7 pagesSids Babyreski ulpayaniNo ratings yet

- Early Prediction of Preterm Birth For Singleton, Twin, and Triplet PregnanciesDocument6 pagesEarly Prediction of Preterm Birth For Singleton, Twin, and Triplet PregnanciesNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Contraception for the Medically Challenging PatientFrom EverandContraception for the Medically Challenging PatientRebecca H. AllenNo ratings yet

- Childhood Obesity: Causes and Consequences, Prevention and Management.From EverandChildhood Obesity: Causes and Consequences, Prevention and Management.No ratings yet

- Pregnancy Tests Explained (2Nd Edition): Current Trends of Antenatal TestsFrom EverandPregnancy Tests Explained (2Nd Edition): Current Trends of Antenatal TestsNo ratings yet

- Article Ejbps Volume 3 December Issue 12 1480826682Document4 pagesArticle Ejbps Volume 3 December Issue 12 1480826682kelompok5No ratings yet

- DR - Indra GunawanDocument1 pageDR - Indra GunawanIndRa KaBhuomNo ratings yet

- Program MagisterDocument1 pageProgram MagisterIndRa KaBhuomNo ratings yet

- The Management and Outcomes of Placenta AccretaDocument11 pagesThe Management and Outcomes of Placenta AccretaIndRa KaBhuomNo ratings yet

- Surgical Treatment of Cesarean Scar Ectopic PregnancyDocument7 pagesSurgical Treatment of Cesarean Scar Ectopic PregnancyIndRa KaBhuomNo ratings yet

- Unreported Births and Deaths, A Severe ObstacleDocument8 pagesUnreported Births and Deaths, A Severe ObstacleIndRa KaBhuomNo ratings yet

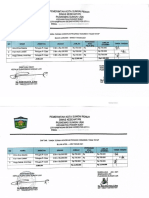

- Honorium JKN 2021 - Compressed-1Document4 pagesHonorium JKN 2021 - Compressed-1IndRa KaBhuomNo ratings yet

- Honorium WindiDocument4 pagesHonorium WindiIndRa KaBhuomNo ratings yet

- Social Network in Contraceptive DecisionDocument11 pagesSocial Network in Contraceptive DecisionIndRa KaBhuomNo ratings yet

- Rundown AclsDocument4 pagesRundown AclsIndRa KaBhuomNo ratings yet

- Document From Indra Gunawan-1Document1 pageDocument From Indra Gunawan-1IndRa KaBhuomNo ratings yet

- JADWAL DOKTER JAGADocument3 pagesJADWAL DOKTER JAGAIndRa KaBhuomNo ratings yet

- Otitis Media Acute Antimicrobial Prescribing PDF 1837750121413Document23 pagesOtitis Media Acute Antimicrobial Prescribing PDF 1837750121413IndRa KaBhuomNo ratings yet

- WS Emergency Echo SYMCARD 2022Document33 pagesWS Emergency Echo SYMCARD 2022IndRa KaBhuomNo ratings yet

- Autoimmune Inner Ear Disease in A Melanoma Patient Treated With PembrolizumabDocument6 pagesAutoimmune Inner Ear Disease in A Melanoma Patient Treated With PembrolizumabIndRa KaBhuomNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S167229301730034X MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S167229301730034X MainIndRa KaBhuomNo ratings yet

- FessDocument4 pagesFessIndRa KaBhuomNo ratings yet

- Visual Working Memory Span in Adults With 2017 World Journal of OtorhinolarDocument7 pagesVisual Working Memory Span in Adults With 2017 World Journal of OtorhinolarIndRa KaBhuomNo ratings yet

- WJM 4 91Document9 pagesWJM 4 91IndRa KaBhuomNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12Document9 pagesChapter 12Charlie AbagonNo ratings yet

- Maternity Pediatric Nursing 3rd Ricci Test BankDocument8 pagesMaternity Pediatric Nursing 3rd Ricci Test Banksonyaaaq0% (1)

- Deficient Fluid Volume (Isotonic) : Anxiety FearDocument2 pagesDeficient Fluid Volume (Isotonic) : Anxiety FearVincent Paul SantosNo ratings yet

- Benign Breast DiseaseDocument26 pagesBenign Breast DiseaseMedicine 0786No ratings yet

- Inheritance 4 6 3Document21 pagesInheritance 4 6 3Aftab AhmedNo ratings yet

- EDU550 - CHILD BIRTH TYPESDocument16 pagesEDU550 - CHILD BIRTH TYPESसंजेश सुधेश शर्माNo ratings yet

- Nfhs-6 Interviewer's ManualDocument178 pagesNfhs-6 Interviewer's ManualDisability Rights AllianceNo ratings yet

- 33873-Article Text-121761-1-10-20170831Document6 pages33873-Article Text-121761-1-10-20170831AnggaNo ratings yet

- Save The Girl Child - Essay - Important IndiaDocument8 pagesSave The Girl Child - Essay - Important IndiaAnonymous 1b3ih8zg9100% (1)

- Brittany Carter Final EnglishDocument11 pagesBrittany Carter Final Englishapi-582411411No ratings yet

- Nursing Test Series Questions & AnswersDocument24 pagesNursing Test Series Questions & AnswersDr-Sanjay SinghaniaNo ratings yet

- Progress NoteDocument3 pagesProgress NoteHaji JawaroNo ratings yet

- MAA Directed By: Sarjun KMDocument27 pagesMAA Directed By: Sarjun KMJan ArthanNo ratings yet

- Spontaneous Abortion: DR - Renu SinghDocument38 pagesSpontaneous Abortion: DR - Renu SinghRosalyn Marie SugayNo ratings yet

- Expert Review Details How Aspirin Prevents PreeclampsiaDocument12 pagesExpert Review Details How Aspirin Prevents PreeclampsiaranggaNo ratings yet

- VTE in Pregnancy 2021 by DR AmanuelDocument43 pagesVTE in Pregnancy 2021 by DR AmanuelAmanuel We/gebriel100% (1)

- FERTILIZATION TO FOETAL DEVELOPMENTDocument39 pagesFERTILIZATION TO FOETAL DEVELOPMENTeryna sofeaNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Maternal Hypergalactia: Invited ReviewDocument3 pagesTreatment of Maternal Hypergalactia: Invited ReviewMaria ChristodoulouNo ratings yet

- Bladder AnatomuDocument1 pageBladder AnatomuCarlotta ranalliNo ratings yet

- NFHS-5 Interviewer Manual - EngDocument182 pagesNFHS-5 Interviewer Manual - EngDisability Rights AllianceNo ratings yet

- Sexuality: by Walter LastDocument21 pagesSexuality: by Walter LastSarah JadeNo ratings yet

- Diabetes IN Pregnancy: Presenter: DR Leong Yuh Yang (MD Ukm) Supervisor: DR Noraza AzmeeraDocument45 pagesDiabetes IN Pregnancy: Presenter: DR Leong Yuh Yang (MD Ukm) Supervisor: DR Noraza AzmeeraLeong YuhyangNo ratings yet

- Gestational Diabetes - On Broadening The DiagnosisDocument2 pagesGestational Diabetes - On Broadening The DiagnosisWillians ReyesNo ratings yet

- Aipmnh Annual Work Plan 2012 Indonesian PDFDocument67 pagesAipmnh Annual Work Plan 2012 Indonesian PDFsalmanNo ratings yet

- TEENAGE PREGNANCY DefenseDocument15 pagesTEENAGE PREGNANCY DefenseNash CasunggayNo ratings yet

- Full Download Test Bank For Maternal Child Nursing 5th Edition by Mckinney For 29 99 PDF Full ChapterDocument36 pagesFull Download Test Bank For Maternal Child Nursing 5th Edition by Mckinney For 29 99 PDF Full Chaptertrigraph.loupingtaygv100% (19)

- Cornell Student Assembly Resolution Opposing Texas Heartbeat ActDocument3 pagesCornell Student Assembly Resolution Opposing Texas Heartbeat ActThe College FixNo ratings yet

- Prelim ncm105Document4 pagesPrelim ncm105klirt carayoNo ratings yet

- Sudden Unexplained Early Neonatal Death or CollapsDocument7 pagesSudden Unexplained Early Neonatal Death or CollapsMaria Alejandra ForeroNo ratings yet

- Putting Abortion Pills Into Women's Hands: Realizing The Full Potential of Medical AbortionDocument4 pagesPutting Abortion Pills Into Women's Hands: Realizing The Full Potential of Medical AbortionFake_Me_No ratings yet