Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Instagram Use Is Linked To Increased Symptoms of o

Uploaded by

Alexandru CulceaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Instagram Use Is Linked To Increased Symptoms of o

Uploaded by

Alexandru CulceaCopyright:

Available Formats

Eat Weight Disord (2017) 22:277–284

DOI 10.1007/s40519-017-0364-2

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Instagram use is linked to increased symptoms of orthorexia

nervosa

Pixie G. Turner1 · Carmen E. Lefevre2

Received: 22 November 2016 / Accepted: 21 January 2017 / Published online: 1 March 2017

© The Author(s) 2017. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com

Abstract among the study population was 49%, which is signifi-

Purpose Social media use is ever increasing amongst cantly higher than the general population (<1%).

young adults and has previously been shown to have nega- Conclusions Our results suggest that the healthy eating

tive effects on body image, depression, social comparison, community on Instagram has a high prevalence of ortho-

and disordered eating. One eating disorder of interest in rexia symptoms, with higher Instagram use being linked to

this context is orthorexia nervosa, an obsession with eat- increased symptoms. These findings highlight the implica-

ing healthily. High orthorexia nervosa prevalence has been tions social media can have on psychological wellbeing,

found in populations who take an active interest in their and the influence social media ‘celebrities’ may have over

health and body and is frequently comorbid with anorexia hundreds of thousands of individuals. These results may

nervosa. Here, we investigate links between social media also have clinical implications for eating disorder develop-

use, in particularly Instagram and orthorexia nervosa ment and recovery.

symptoms.

Methods We conducted an online survey of social Keywords Orthorexia nervosa · Eating disorder · Social

media users (N = 680) following health food accounts. media · Instagram

We assessed their social media use, eating behaviours,

and orthorexia nervosa symptoms using the ORTO-15

inventory. Introduction

Results Higher Instagram use was associated with a

greater tendency towards orthorexia nervosa, with no other Social media use is constantly increasing, with now 90%

social media channel having this effect. In exploratory of UK young adults (aged 16–34 years) accessing social

analyses Twitter showed a small positive association with media platforms [1]. As such it is important to better under-

orthorexia symptoms. BMI and age had no association with stand the effects that social media use may have on mental

orthorexia nervosa. The prevalence of orthorexia nervosa wellbeing. One example is the social media based healthy

eating community, which has recently grown in popularity

This article is part of the topical collection on Orthorexia

[2]. While overall this movement has been positive, with

nervosa. members striving to eat more fruits and vegetables and

fewer processed foods, there is a growing concern around

* Carmen E. Lefevre it triggering negative behaviours and eating disorders [3].

c.lefevre@ucl.ac.uk

One eating disorder of interest in this context is orthorexia

Pixie G. Turner nervosa (ON), an obsession with eating healthily [4]. Pre-

pixie‑t@hotmail.co.uk

vious work around similar disorders suggests that social

1

Division of Medicine, UCL, London WC1E 6BT, UK media use may contribute to an ‘echo-chamber’ effect,

2 where users perceive their values and world-views to be

Centre for Behaviour Change, Department

of Clinical, Education and Health Psychology, UCL, more common than they actually are, due to selectively

London WC1E 7HB, UK viewing contributions of other, similarly minded people

13

Vol.:(0123456789)

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

278 Eat Weight Disord (2017) 22:277–284

[5]. In light of this effect, here we investigated whether symptoms in an experimental study when compared to

time spent on social media is associated with symptoms of control participants who viewed neutral websites [17].

ON. We focus on Instagram, as it is most prevalent in the More frequent Instagram use has been directly associ-

healthy-eating movement [3] but also assess other social ated with greater levels of depressive symptoms, and fol-

media channels in an exploratory analysis. lowing a greater number of strangers is associated with

Instagram, launched in 2010, is an online social net- greater levels of negative social comparison [18]. An

working service that is currently used by 53% of Ameri- analysis of the #fitspiration tag on Instagram, a tag used

can young adults (aged 18–29 years) with internet access to denote images intended to inspire people to become fit

[6]. The platform enables users to post pictures and videos and healthy, found that the majority of images of women

to their profiles, add a caption, use hashtags (# symbol) showed a thin and toned body type with objectifying ele-

to describe the photos, and tag other users (@ symbol). ments, which could have negative effects on body image

Users can follow any number of accounts and view a steady and self-esteem [19]. Moreover, researchers have pointed

stream of content posted by the users they follow where out the key role of social comparison in body image dis-

they can “like” or “comment” on posts. Instagram suggests turbance [20]. However, image-based platforms such as

new accounts to follow based on the content that the user is Instagram have also been shown to confer a significant

already exposed to. Posts are dominated by the content of decrease in self-reported loneliness to users, whereas

the images rather than any captions or comments. In June text-based platforms such as Twitter do not [21]. Taken

2016 Instagram had 500 million registered users worldwide together, while there is some evidence for negative links

[7], making it the third biggest social media platform after between social media use and mental health, the picture

Facebook and Tumblr. A US poll showed the average user is far from clear and social media may indeed also have

spends 21.2 min on Instagram each day, with the 18–29 age positive or protective qualities in certain circumstances.

group spending the most time at 30 min [8]. Recently there has been much media coverage on the

The hashtag #food is one of the top 25 most popular role of social media, particularly Instagram, in the ‘healthy

hashtags on Instagram.1 A more detailed analysis of Insta- eating movement’ in the UK [2, 22], despite a lack of cur-

gram photo content found it to be one of eight popular cat- rent academic literature on the subject. Pioneers of this

egories along with self-portraits (or “selfies”), friends, movement have a powerful social media presence, particu-

activities, captioned photos, gadgets, fashion, and pets [9], larly on Instagram, reaching and influencing hundreds of

suggesting the importance of Instagram for the sharing of thousands of people, despite often having no formal train-

food-related content. Healthy food posts tend to receive ing in health sciences or nutrition. Because Instagram is

more support from users than less healthy images [10], an image-based platform, users may be more likely to fol-

indicating a positive attitude towards healthy foods and low advice or imitate the diets of Instagram ‘celebrities’ as

healthy eating. Research also suggests that social media is they feel a more personal connection than they would on

used to inform actual food choices, with 54% of consumers a text-based platform. Although often not based on scien-

using social media to discover and share food experiences, tific evidence, individuals are encouraged to cut out vari-

and 42% using social media to seek advice about food [11]. ous food groups from their diets, potentially leading to an

Documentation, surveillance, and creativity have all been unbalanced diet and deficiencies. Moreover, this advice

identified as motivations for Instagram use [12, 13], which may encourage psychological problems around food, and in

corresponds well with the sharing of food images—both as some cases, lead to eating disorders such as anorexia ner-

a food diary (documentation/creativity) and searching for vosa (AN) [3] or ON.

recipes and inspiration (surveillance). Orthorexia nervosa is defined as an unhealthy obses-

Instagram and social media more broadly have been sion with eating healthy food. The term is derived from

associated with mental health problems. For example, the Greek “orthos,” meaning “correct”, and was coined

social media use has been associated with higher lev- by Steven Bratman [4]. Despite not appearing in the Diag-

els of depression in young adults [14], as well as eat- nostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)

ing disorders and related behaviours [15]. For example, [23], ON has sparked a body of research. The proposed

adolescents who view health and fitness-related content diagnostic criteria for ON [24] include obsessive focus on

on social media are more likely to have an eating disor- healthy eating, food anxiety, and dietary restrictions, with

der [15]. In patients with AN, extensive Facebook use these behaviours causing clinical impairments. There is

is associated with greater levels of symptoms [16], and some overlap between ON, AN and obsessive compulsive

viewing pro-anorexia websites worsened psychological disorder (OCD) [25]. Both AN and ON share traits of per-

fectionism, cognitive rigidity, and guilt over food transgres-

sions, while OCD and ON share intrusive thoughts and

1

https://top-hashtags.com/instagram/. ritualised food preparation. However, while AN patients are

13

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Eat Weight Disord (2017) 22:277–284 279

preoccupied with the quantity of food, ON patients are pre- newsletter. Data were collected from 713 participants (23

occupied with the quality of food. males, 686 females, 4 other/prefer not to say. Mean age

Orthorexia symptoms are associated with healthy life- 24.96 ± 8.17 years). Non-female participants (N = 27) and

style choices such as eating more fruit and vegetables, eat- participants for whom an ORTO-15 score could not be cal-

ing less white cereals, shopping in health food stores, exer- culated due to missing data (N = 6) were excluded from the

cise, and reduced alcohol consumption [26]. But ON is also main analysis. We decided to concentrate on female partici-

associated with significant dietary restrictions, malnutri- pants as the N recruited for men was too low to provide

tion, and social isolation [27], although there is no appar- adequate power for statistical analyses.

ent association with BMI [26, 28]. Currently the ORTO-15 The final sample thus consisted of 680 females, age

questionnaire [29] is used to determine the presence of ON. 18–75 years (mean = 24.70 ± 7.87) with an average healthy

Higher prevalence has been found in yoga instructors [30], BMI (mean = 22.14 ± 3.89). 44.6% of participants lived in

dieticians, [31], nutrition students [32], and exercise sci- UK, 26.7% in the US, with the remainder living in an addi-

ence students [33] compared to the general population. The tional 40 countries. All participants gave their informed

prevalence of ON in the general population was recently consent before starting the questionnaire and the study was

estimated to be less than 1% [34]. approved by the UCL ethics committee.

There are several reasons as to why ON does not cur-

rently appear in the DSM. For example, Varga et al. point Survey

out that there are psychometric limitations to the ORTO-

15 questionnaire, such as issues with internal consistency, Our online survey was developed using Qualtrics (http://

lack of standardisation, and cultural variation [24, 26, 35]. www.qualtrics.com). The questions we asked are detailed

Furthermore, the high cut-off score may lead to false posi- in the following.

tives [36], arguably rendering the questionnaire unsuitable

as a diagnostic tool. In addition, questions have been raised Social media use

as to whether ON can simply be described as a subtype of

another disorder, such as AN, OCD, or Avoidant/Restric- Participants were asked “Which social media channels do

tive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) [37]. However, Dunn you use?” and could select multiple responses out of: Insta-

and Bratman [24] make a compelling argument that there gram, Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Google+, Tumblr, and

is sufficient evidence to suggest ON is a distinct condition. LinkedIn. These are all content-based social media chan-

Currently the relationship between ON and social media nels which have a ‘newsfeed’, and where other users can be

use is unclear, although links between social media use and added/followed. While Instagram and Pinterest are mainly

AN have been reported. Taken together, the reported nega- image-based, Facebook, Twitter, Google+, and LinkedIn

tive effects of social media on psychological wellbeing, the focus on text entries, with Tumblr having elements of

role of Instagram in food sharing and negative social com- both. Next, participants were asked about the amount of

parison, and the popularity of the healthy eating movement time spent on each channel they use: (1) “How often do

on Instagram suggests that there may be a positive relation- you access [channel]?” with multiple-choice answers of

ship between ON and use of social media, and that Insta- “Less than once per month, 1–3 times per month, once a

gram may play a key role in the development and mainte- week, 2–3 times per week, 4–5 times per week, once a day,

nance of disordered eating patterns. Accordingly, here we several times per day”, and (2) “On a typical day where

assess whether there is a link between Instagram use and you access [channel], how much time do you spend on it

symptoms of ON. in total?” with multiple-choice answers of “Less than 15,

15–30, 31–60, 60+ min”. In addition, participants who

indicated using Instagram were asked to rank-order Hu

Methods and materials et al. [9] eight popular content types for the frequency with

which they typically appear on their feed.

Participants

Dietary choices

Participants were recruited via not-paid-for advertisements

on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter, as well as the blog Participants were asked which of 19 food types they

“Plantbased Pixie”2 and the “Heath Bloggers Community” included in their diet: red meat, white meat, processed

meat, fish, dairy products, eggs, fruit, vegetables, whole-

grains, refined grains, refined sugars, wheat, gluten, salt,

2

http://www.plantbased-pixie.com/my-survey-health-habits-on- oils, beans and pulses, processed/prepared foods, alcohol,

social-media/. and nightshades. Participants were also asked which label

13

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

280 Eat Weight Disord (2017) 22:277–284

Table 1 Demographic information for participants

Demographics Participants (mean ± SD)

Age 24.70 ± 7.87

BMI 22.14 ± 3.89

Number of food items eaten (out of n = 19) 11.88 ± 3.67

Number of social media channels (out of n = 7) 3.55 ± 1.25

ORTO-15 score 34.33 ± 4.04

Participants (%)

Diet 28.4% vegan, 24.7% omnivore, 12.2% vegetarian, 34.7%

other

Country of residence 44.6% UK, 26.7% US, remaining from 40 other countries

Ethnicity 85.0% Caucasian, 6.0% Asian, 3.8% Hispanic, 5.2% other

Table 2 Prevalence of social Instagram Facebook Twitter Pinterest Google+ Tumblr LinkedIn

media use, by % use of each

channel, % visiting daily, and % using this channel 94.5% 88.1% 41.0% 54.9% 12.3% 20.7% 29.0%

median time spent on each

% users visiting daily 95.0% 88.9% 56.7% 24.5% 31.8% 25.0% 7.7%

channel

Median time users 15–30 min 15–30 min <15 min 15–30 min <15 min 15–30 min <15 min

spend on this channel

per day

best described their diet: omnivore, vegetarian, vegan, pes- media time was converted into a score of approximate min-

catarian, paleo, plant-based, high-carb low-fat, raw vegan, utes per week spent on each channel (following [38]).

other. Height was converted to meters and weight to kg to cal-

culate BMI. Only a small percentage of data was missing

Orthorexia nervosa measure (3.82%), most of which was height and weight data.

Analyses were performed in Microsoft Excel 2016 and

The ORTO-15 questionnaire [29] was used to assess for SPSS Version 24. Because data on social media use was

orthorexic symptoms. ORTO-15 is a multiple-choice ques- non-parametric, Spearman’s rank order correlations were

tionnaire consisting of 15 items with 4-point Likert-scale used to determine relationships between ORTO-15 score

response options. A score of 1 is assigned to behaviours and social media use. Data on ORTO-15 scores was nor-

that most reflect orthorexic symptoms, with a score of 4 mally distributed, therefore, Pearson product-moment cor-

assigned to the most normal behaviours, meaning lower relations were used to determine relationships between

scores indicate higher levels of ON symptoms. ORTO-15 scores and the variables age and BMI. Post-hoc

analysis used Spearman’s rank order correlations to deter-

mine the relationship between ORTO-15 scores and both

Demographics number of food types and number of social media channels.

Participants were asked their age (years), sex (male, female,

other/prefer not to say), ethnicity, country of residence, Results

height (cm or feet/inches), and weight (kg or lbs).

Sample characteristics

Assessment and analysis

For a summary of demographic sample characteristics see

An ORTO-15 score was calculated for each participant. We Table 1. All but one participant used at least one social

used two cut-off scores due to disagreement in the literature media channel (range = 0–7; mean = 3.55 ± 1.25), with

over the appropriate cut-off point: less than 40 (following Instagram being the most popular and Google+ the least

[28]), and less than 35 (following [35]). Participants’ social popular (Table 2). 80% of participants who used Instagram

13

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Eat Weight Disord (2017) 22:277–284 281

Fig. 1 The negative relation- 50

ship between time spent on

Instagram and ORTO-15 score

45

40

ORTO-15 score

35

30

25

20

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400 450

Time spent on Instagram (mins/week)

Table 3 Correlations between Instagram Facebook Twitter Pinterest Google+ Tumblr LinkedIn

time spent on each social media

channel and ORTO-15 score ORTO-15 −0.10** 0.04 0.12* −0.06 0.15 0.10 −0.04

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

ranked food as 1st or 2nd most frequent image category To assess the robustness of the correlation between

appearing on their Instagram feed. ORTO-15 and Instagram use when controlling for poten-

28.4% of participants reported following a vegan diet, tially confounding demographic variables, we addition-

24.7% an omnivorous diet, and the remainder either a veg- ally conducted linear regression analysis with ORTO-15

etarian, pescatarian, paleo, plant-based, high-carb low fat, score as the outcome measure and Instagram use, age,

raw vegan, or other diet. The mean number of food types BMI, ethnicity (dummy coded as white/non-white), and

eaten was 11.88 ± 3.67 of a possible 19. country of residence (dummy coded as UK/non-UK) as

The prevalence of ON in our sample was 90.6% with a the predictor variables. The overall model was signifi-

cut-off score of <40, or 49.0% with a cut-off score of <35. cant [F(5,648) = 9.58, p < 0.001)] with Instagram use (β

This did not change amongst the sub-sample of Instagram = −0.12, p = 0.003) and country of residence (β = 0.23,

users (N = 669; 90.4% <40, or 49.3% <35). p < 0.001) being significant predictors. The remaining vari-

ables were not significant (all p > 0.22).

Inferential Results

No relationship was found between ORTO-15 scores and Discussion

number of food types eaten (r = −0.01; p = 0.87), num-

ber of social media channels used (r < 0.01; p = 0.99), age This study investigated the relationship between social

(r = −0.06; p = 0.13), or BMI (r = −0.03; p = 0.47). There media use and ON. We found a significant relationship

were also no significant differences in ORTO-15 score between symptoms of ON as measured by the ORTO-15

between diet types as determined by one-way ANOVA test and Instagram use, with higher Instagram use being

[F(5,674) = 0.705, p = 0.620]. We, therefore, did not control associated with a greater tendency towards ON. No other

for these variables in our correlational analyses. social media channels were found to have this effect,

As predicted, there was a negative correlation between although Twitter seemed to have a small protective associa-

ORTO-15 score and Instagram use (r = −0.10; p = 0.01) tion. While the effect size was small, the large population

(Fig. 1). No significant relationship was found between of social media users, now over 500 million on Instagram

ORTO-15 score and other social media use (Table 3), alone, means that this is a meaningful effect at population

except Twitter which showed a small positive correlation level.

(r = 0.12, p = 0.04). There are several factors that likely contribute to the

association between Instagram use and ON symptoms:

13

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

282 Eat Weight Disord (2017) 22:277–284

First, the image-focused nature of Instagram, which plays The relationship between Instagram use and ON symp-

to the picture-superiority effect—whereby images are more toms reported here has potential clinical implications, as

likely to be remembered than words [39]—and makes Ins- there are overlaps between ON and AN [25], and ON has

tagram ideal for sharing food images. Second, social media been found to be a frequent comorbidity with both AN

allows for and encourages selective exposure, as users and bulimia nervosa [40]. In fact, ON symptoms have

choose which accounts they wish to follow, and so are then been found to worsen following treatment for other eating

continually exposed to the type of content these accounts disorders, suggesting that ON may be a compromise by

produce. This limited exposure in turn may lead to users which patients continue to exercise control over food and

believing a behaviour is more prevalent or normal than is their body, although to a lesser degree than in AN. This

actually the case, and may lead to perceived social pres- is consistent with the finding that ON and BMI are not

sures to conform to such behaviours. Moreover, problem- related [26, 28]. A lack of relationship between ON and

atic behaviours may be continuously reinforced through type of diet further suggests that orthorexic behaviour is

image exposure and personal interactions on the platform. not limited to eliminating specific food groups.

Third, there is likely a prevalence of eminence-based prac-

tice by which users with a large following may be perceived

as authorities, allowing healthy eating ‘celebrities’ to influ- Limitations and further research

ence large numbers of individuals by giving their followers

a constant and curated feed of images portraying a certain Participants were recruited through convenient non-

diet or behaviour. Overall, these factors may explain why random sampling, with the majority coming from the

Instagram, an image-based social media, has been the plat- author’s Instagram account (83%), which is not represent-

form of choice for the healthy eating community [3]. ative of the general population. In addition, the research

Although only Instagram was predicted to have an asso- title (Health habits on social media) may have attracted

ciation with ON, exploratory analysis into other social individuals with an interest in health. Furthermore, BMI

media channels showed that Twitter had a positive associa- was calculated from self-report rather than measured,

tion with ON symptoms. While purely exploratory, this is accordingly, we cannot rule out error and deliberate miss-

an interesting result that future work should seek to repli- reporting. Finally, we did not assess whether some par-

cate. If correct, we speculate that this effect may be linked ticipants followed a strict diet for medical reasons. While

to the text-focused and strictly character-limited nature of this is unlikely to affect the overall results, its omission

twitter, which does not compliment a food-focused commu- may have introduced unnecessary noise.

nity as well as an image-based platform such as Instagram. Because a large proportion of our study sample used

We believe this is the first study investigating a link more than one social media channel, we cannot exclude

between social media and ON, and it contributes to the the possibility of interactions between these channels.

growing body of literature on ON and its causes. The While this was not the focus of the current study, consid-

high prevalence of ON in the current study population is ering over half of online-active adults use more than one

reflected in previous studies, where higher prevalence was social media channel [6], such interactions may present

found in yoga instructors (86%) [30], dieticians (41.9%) an interesting avenue for future research. Future research

[31], nutrition students (35.9%) [32], exercise science stu- may wish to further address these open questions. In the

dents (84.5%) [33], and patients recovering from AN or current study, we cannot establish a causal relationship

bulimia nervosa (58%) [40] compared to the general popu- between Instagram use and ON symptoms due to the cor-

lation (<1%) [29, 34]. These are all populations who take relational nature of our study, and future research may

an active interest in their health and body, in the same way wish to assess possible causal link between these vari-

that the healthy eating community on Instagram might be. ables as well as possibly test intervention strategies for

When using the higher cut-off <40, the prevalence of ON alleviating negative effects of Instagram use.

in the current study population was higher than any other

previously studied population, and occurred despite par-

ticipants spending no more time on Instagram per day, on

average, than the general population (15–30 vs. 21.2 min Conclusion

[8]). Even when using the lower cut-off <35, which may be

more specific, the prevalence was still considerably higher The current findings suggest that within the study popula-

than the general population. It is possible that we tapped tion, higher Instagram use was associated with stronger

a sub-group of Instagram users who are using it predomi- orthorexic symptoms. No other social media channel had

nantly for food-related enquiries and who prescribe to the this effect, although Twitter had a small positive associa-

‘healthy eating movement’. tion. Age, BMI, number of social media channels, and

13

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Eat Weight Disord (2017) 22:277–284 283

type of diet had no effect on orthorexia nervosa symp- 12. Lee E, Lee J-A, Moon JH, Sung Y (2015) Pictures speak louder

toms. Overall, these findings provide an initial indica- than words: Motivations for using Instagram. Cyberpsychol

Behav Soc Netw 18(9):552–556

tion of the role that modern social media may play in the 13. Sheldon P, Bryant K (2016) Instagram: Motives for its use and

onset and progression of eating disorders. relationship to narcissism and contextual age. Comput Hum

Behav 58:89–97

Compliance with ethical standards 14. Sidani JE, Shensa A, Radovic A, Miller E, Colditz JB, Hoff-

man BL, Giles LM, Primack BA (2016) Association between

Conflict of interest Pixie Turner declares she has no conflict of in- social media use and depression among US young adults.

terest. Carmen Lefevre declares she has no conflict of interest. Depress Anxiety 33(4):323–331

15. Carrotte ER, Vella AM, Lim MS (2015) Predictors of “lik-

Ethical approval All procedures performed in studies involving ing” three types of health and fitness-related content on social

human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of media: a cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res 17(8)

the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 16. Mabe AG, Forney KJ, Keel PK (2014) Do you “like” my

Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical photo? Facebook use maintains eating disorder risk. Int J Eat

standards. The study was approved by the UCL ethics committee. Disord 47(5):516–523

17. Bardone-Cone AM, Cass KM (2007) What does viewing a

pro-anorexia website do? An experimental examination of

Informed consent All participants gave their informed consent website exposure and moderating effects. Int J Eat Disord

before starting the questionnaire. 40(6):537–548

18. Lup K, Trub L, Rosenthal L (2015) Instagram# Instasad?:

exploring associations among Instagram use, depressive symp-

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the toms, negative social comparison, and strangers followed.

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http:// Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 18(5):247–252

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted 19. Tiggemann M, Zaccardo M (2016) ‘Strong is the new skinny’:

use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give A content analysis of# fitspiration images on Instagram. J Health

appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a Psychol:1359105316639436

link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were 20. Morrison TG, Kalin R, Morrison MA (2004) Body-image evalu-

made. ation and body-image investment among adolescents: A test

of sociocultural and social comparison theories. Adolescence

39(155):571

21. Pittman M, Reich B (2016) Social media and loneliness: Why an

Instagram picture may be worth more than a thousand Twitter

References words. Comput Hum Behav 62:155–167

22. Rainey S (2016) How TV’s new queens of healthy eating are

1. Ofcom (2015) Communications Market Report 2015. Ofcom serving up hogwash: Collagen soup. Eggs that are ‘astrologically

2. Freeman H (2015) Green is the new black: the unstoppable rise harvested’ and why the Hemsley sisters don’t have a shred of

of the healthy-eating guru. Guardian expertise between them. Daily Mail

3. Marsh S, Campbell D (2016) Clean eating trend can be danger- 23. American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statisti-

ous for young people, experts warn. Guardian cal manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiat-

4. Bratman S, Knight D (2000) Health food junkies: orthorexia ner- ric Pub

vosa–overcoming the obsession with healthful eating. Broadway, 24. Dunn TM, Bratman S (2016) On orthorexia nervosa: A review

New York of the literature and proposed diagnostic criteria. Eat Behav

5. Salathé M, Khandelwal S (2011) Assessing vaccination senti- 21:11–17

ments with online social media: implications for infectious dis- 25. Koven NS, Abry AW (2015) The clinical basis of orthorexia ner-

ease dynamics and control. PLoS Comput Biol 7(10):e1002199 vosa: emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatric Disease & Treat-

6. Duggan M, Ellison NB, Lampe C, Lenhart A, Madden M (2015) ment 11

Social media update 2014. Pew Research Center 9 26. Varga M, Thege BK, Dukay-Szabó S, Túry F, van Furth EF

7. Instagram Blog (2016) Instagram today: 500 mil- (2014) When eating healthy is not healthy: orthorexia nervosa

lion Windows to the world. http://blog.instagram.com/ and its measurement with the ORTO-15 in Hungary. BMC Psy-

post/146255204757/160621-news. 2016 chiatry 14(1):1

8. Cowen and Company (2014) Younger users spend more daily 27. Moroze RM, Dunn TM, Holland JC, Yager J, Weintraub P

time on social networks. http://www.emarketer.com/Arti- (2015) Microthinking about micronutrients: a case of transi-

cle/Younger-Users-Spend-More-Daily-Time-on-Social-Net- tion from obsessions about healthy eating to near-fatal “ortho-

works/1011592. 2016 rexia nervosa” and proposed diagnostic criteria. Psychosomatics

9. Hu Y, Manikonda L, Kambhampati S (2014) What we Insta- 56(4):397–403

gram: a first analysis of Instagram photo content and user types. 28. Arusoğlu G, Kabakci E, Köksal G, Merdol TK (2008) Ortho-

In: ICWSM rexia nervosa and adaptaon of ORTO-11 into Turkish. Turk J

10. Sharma SS, De Choudhury M (2015) Measuring and character- Psychiatry 19(3):283–291

izing nutritional information of food and ingestion content in ins- 29. Donini L, Marsili D, Graziani M, Imbriale M, Cannella C (2005)

tagram. In: Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Orthorexia nervosa: validation of a diagnosis questionnaire. Eat

World Wide Web, 2015. ACM, pp 115–116 Weight Disord-Stud Anorex Bulim Obes 10(2):e28–e32

11. The Hartman Group (2012) Clicks and cravings: the impact of 30. Valera JH, Ruiz PA, Valdespino BR, Visioli F (2014) Preva-

social technology on food culture. http://www.unitedfreshshow. lence of orthorexia nervosa among ashtanga yoga practition-

org/files/clicks_and_craving.june_lee.pdf. Accessed August ers: a pilot study. Eat Weight Disord-Stud Anorex Bulim Obes

2016 19(4):469–472

13

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

284 Eat Weight Disord (2017) 22:277–284

31. Asil E, Sürücüoğlu MS (2015) Orthorexia nervosa in Turkish 36. Ramacciotti C, Perrone P, Coli E, Burgalassi A, Conversano C,

dietitians. Ecol Food Nutr 54(4):303–313 Massimetti G, Dell’Osso L (2011) Orthorexia nervosa in the

32. Bo S, Zoccali R, Ponzo V, Soldati L, De Carli L, Benso A, Fea general population: a preliminary screening using a self-adminis-

E, Rainoldi A, Durazzo M, Fassino S (2014) University courses, tered questionnaire (ORTO-15). Eat Weight Disord-Stud Anorex

eating problems and muscle dysmorphia: are there any associa- Bulim Obes 16(2):e127–e130

tions? J Transl Med 12(1):1 37. Kummer A, Dias F, Teixeira A (2008) On the concept of ortho-

33. Malmborg J, Bremander A, Olsson MC, Bergman S (2017)

rexia nervosa. Scand J Med Sci Sports 18(3):395–396

Health status, physical activity, and orthorexia nervosa: A com- 38. Hughes DJ, Rowe M, Batey M, Lee A (2012) A tale of two sites:

parison between exercise science students and business students. Twitter vs. Facebook and the personality predictors of social

Appetite 109:137–143 media usage. Comput Hum Behav 28(2):561–569

34. Dunn TM, Gibbs J, Whitney N, Starosta A (2016) Prevalence of 39. Childers TL, Houston MJ (1984) Conditions for a picture-superi-

orthorexia nervosa is less than 1%: data from a US sample. Eat ority effect on consumer memory. J Consum Res 11(2):643–654

Weight Disord-Stud Anorex Bulim Obes:1–8 40. Segura-Garcia C, Ramacciotti C, Rania M, Aloi M, Caroleo

35. Missbach B, Dunn TM, König JS (2016) We need new tools to M, Bruni A, Gazzarrini D, Sinopoli F, De Fazio P (2015) The

assess Orthorexia Nervosa. A commentary on “Prevalence of prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among eating disorder patients

Orthorexia Nervosa among College Students Based on Brat- after treatment. Eat Weight Disord-Stud Anorex Bulim Obes

man’s Test and Associated Tendencies”. Appetite 108:521 20(2):161–166

13

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Terms and Conditions

Springer Nature journal content, brought to you courtesy of Springer Nature Customer Service Center GmbH (“Springer Nature”).

Springer Nature supports a reasonable amount of sharing of research papers by authors, subscribers and authorised users (“Users”), for small-

scale personal, non-commercial use provided that all copyright, trade and service marks and other proprietary notices are maintained. By

accessing, sharing, receiving or otherwise using the Springer Nature journal content you agree to these terms of use (“Terms”). For these

purposes, Springer Nature considers academic use (by researchers and students) to be non-commercial.

These Terms are supplementary and will apply in addition to any applicable website terms and conditions, a relevant site licence or a personal

subscription. These Terms will prevail over any conflict or ambiguity with regards to the relevant terms, a site licence or a personal subscription

(to the extent of the conflict or ambiguity only). For Creative Commons-licensed articles, the terms of the Creative Commons license used will

apply.

We collect and use personal data to provide access to the Springer Nature journal content. We may also use these personal data internally within

ResearchGate and Springer Nature and as agreed share it, in an anonymised way, for purposes of tracking, analysis and reporting. We will not

otherwise disclose your personal data outside the ResearchGate or the Springer Nature group of companies unless we have your permission as

detailed in the Privacy Policy.

While Users may use the Springer Nature journal content for small scale, personal non-commercial use, it is important to note that Users may

not:

1. use such content for the purpose of providing other users with access on a regular or large scale basis or as a means to circumvent access

control;

2. use such content where to do so would be considered a criminal or statutory offence in any jurisdiction, or gives rise to civil liability, or is

otherwise unlawful;

3. falsely or misleadingly imply or suggest endorsement, approval , sponsorship, or association unless explicitly agreed to by Springer Nature in

writing;

4. use bots or other automated methods to access the content or redirect messages

5. override any security feature or exclusionary protocol; or

6. share the content in order to create substitute for Springer Nature products or services or a systematic database of Springer Nature journal

content.

In line with the restriction against commercial use, Springer Nature does not permit the creation of a product or service that creates revenue,

royalties, rent or income from our content or its inclusion as part of a paid for service or for other commercial gain. Springer Nature journal

content cannot be used for inter-library loans and librarians may not upload Springer Nature journal content on a large scale into their, or any

other, institutional repository.

These terms of use are reviewed regularly and may be amended at any time. Springer Nature is not obligated to publish any information or

content on this website and may remove it or features or functionality at our sole discretion, at any time with or without notice. Springer Nature

may revoke this licence to you at any time and remove access to any copies of the Springer Nature journal content which have been saved.

To the fullest extent permitted by law, Springer Nature makes no warranties, representations or guarantees to Users, either express or implied

with respect to the Springer nature journal content and all parties disclaim and waive any implied warranties or warranties imposed by law,

including merchantability or fitness for any particular purpose.

Please note that these rights do not automatically extend to content, data or other material published by Springer Nature that may be licensed

from third parties.

If you would like to use or distribute our Springer Nature journal content to a wider audience or on a regular basis or in any other manner not

expressly permitted by these Terms, please contact Springer Nature at

onlineservice@springernature.com

You might also like

- Integral Nutritional Guide: The Encyclopedia of the Ideas about NutritionFrom EverandIntegral Nutritional Guide: The Encyclopedia of the Ideas about NutritionNo ratings yet

- Cyber 2017 0375 PDFDocument9 pagesCyber 2017 0375 PDFMarcos D'Paula Psicólogo e Assistente SocialNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 15 04687Document13 pagesNutrients 15 04687Hellen MoreiraNo ratings yet

- Nur340 Eating Disorders and Social MediaDocument8 pagesNur340 Eating Disorders and Social Mediaapi-449016971No ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument6 pagesAnnotated BibliographyTatiana StilloNo ratings yet

- Young People's Experiences of Engaging With Fitspiration On Instagram: Gendered PerspectiveDocument16 pagesYoung People's Experiences of Engaging With Fitspiration On Instagram: Gendered PerspectiveakNo ratings yet

- XSocial Media, Thin Ideal, Body Dissatisfaction and Disordered Eating Attitudes An Exploratory AnalysisDocument16 pagesXSocial Media, Thin Ideal, Body Dissatisfaction and Disordered Eating Attitudes An Exploratory AnalysisMaría De Guadalupe ToralesNo ratings yet

- Research Methods Final Proposal 1Document18 pagesResearch Methods Final Proposal 1api-523816461No ratings yet

- Research Essay 1 1 2Document13 pagesResearch Essay 1 1 2api-548943490No ratings yet

- The Effect of Social Media Use On Orthorexia Nervosa A Sample From TurkeyDocument7 pagesThe Effect of Social Media Use On Orthorexia Nervosa A Sample From TurkeyferidecelebiNo ratings yet

- Sidani Et Al, 2016Document16 pagesSidani Et Al, 2016DeepaNo ratings yet

- HuntMarxLipsonYoung2018 NoMoreFOMODocument19 pagesHuntMarxLipsonYoung2018 NoMoreFOMORussell Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- The Role of Social Media Among College StudentsDocument3 pagesThe Role of Social Media Among College StudentsTherese Melchie SantuyoNo ratings yet

- Social Media Affinity and Eating HabitsDocument2 pagesSocial Media Affinity and Eating HabitsKrimson BomedianoNo ratings yet

- Millennials'Document40 pagesMillennials'tiyapnNo ratings yet

- Essay 1.editedDocument6 pagesEssay 1.editedSonia SohniNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Mental Health and Social Media1Document6 pagesRelationship Between Mental Health and Social Media1Meshack MateNo ratings yet

- Environmental Research and Public Health: International Journal ofDocument14 pagesEnvironmental Research and Public Health: International Journal ofMaría De Guadalupe ToralesNo ratings yet

- Revised Amanda Eldridge Final Draft Project 1 1Document8 pagesRevised Amanda Eldridge Final Draft Project 1 1api-665994210No ratings yet

- Nutrients: College Students and Eating Habits: A Study Using An Ecological Model For Healthy BehaviorDocument16 pagesNutrients: College Students and Eating Habits: A Study Using An Ecological Model For Healthy BehaviorAthira VipinNo ratings yet

- Social Media Is A Leading Cause For Eating DisordersDocument12 pagesSocial Media Is A Leading Cause For Eating Disordersrashmithakjn4No ratings yet

- Research - Food WordDocument16 pagesResearch - Food WordMansha SukhijaNo ratings yet

- Reardon (2016) - The Role of Persuasion in Health Promotion and Disease Prevention-2-18Document17 pagesReardon (2016) - The Role of Persuasion in Health Promotion and Disease Prevention-2-18gabrielherreracespedes2No ratings yet

- Social Media Addiction Among Adolescents With Special Reference To Facebook AddictionDocument5 pagesSocial Media Addiction Among Adolescents With Special Reference To Facebook AddictionmediakaNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Social Media On Mental HealthDocument2 pagesThe Effects of Social Media On Mental HealthAlisa OletičNo ratings yet

- Essay 2 Draft 1 1Document9 pagesEssay 2 Draft 1 1api-643387955No ratings yet

- 003 - Behavioural ScienceDocument8 pages003 - Behavioural ScienceAustin Sams UdehNo ratings yet

- Edited ResearchDocument11 pagesEdited ResearchAl LinaresNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 19 11133 v2Document21 pagesIjerph 19 11133 v2Ali ZunairaNo ratings yet

- Background: Adolescents' Use of Social Media, Which Has Increased Considerably in TheDocument3 pagesBackground: Adolescents' Use of Social Media, Which Has Increased Considerably in TheShamaica SurigaoNo ratings yet

- Photoshopping The Selfie Self Photo Editing and Photo EditDocument9 pagesPhotoshopping The Selfie Self Photo Editing and Photo EditDesiré Abrante RodríguezNo ratings yet

- FoodAddictionandObesityDocument10 pagesFoodAddictionandObesityLaura CasadoNo ratings yet

- Research Social AnxietyDocument1 pageResearch Social Anxietycotoc gNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 To 3 3PSYC GANDocument40 pagesChapter 1 To 3 3PSYC GANmorla holaNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 07 05424Document4 pagesNutrients 07 05424Aniket VermaNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Its BackgroundDocument23 pagesThe Problem and Its BackgroundAlthea ʚĩɞNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography Negative Effect of Social MediaDocument6 pagesAnnotated Bibliography Negative Effect of Social MedialukmaanNo ratings yet

- Enc Project 1Document7 pagesEnc Project 1api-708966327No ratings yet

- Social MediaDocument9 pagesSocial MediaMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Social Media Addiction and Psychological EffectDocument8 pagesSocial Media Addiction and Psychological Effectakinleyesanmi42No ratings yet

- MY Article - 21045 - IJPSSDocument15 pagesMY Article - 21045 - IJPSSSwethaNo ratings yet

- Social Media and Its Relationship With Mood, Self-Esteem and Paranoia in PsychosisDocument13 pagesSocial Media and Its Relationship With Mood, Self-Esteem and Paranoia in PsychosisDiego BolívarNo ratings yet

- Zhang Et Al 2017Document15 pagesZhang Et Al 2017Mahmoud Abdelfatah MahgoubNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesLiterature Reviewapi-558391610No ratings yet

- Research Proposal: Topic NameDocument15 pagesResearch Proposal: Topic Namestudents libraryNo ratings yet

- Popular Media Article Evaluation Project - EditedDocument4 pagesPopular Media Article Evaluation Project - EditedJuliana ChesireNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument5 pagesAnnotated BibliographyZack RognerNo ratings yet

- Adolescent Obesity and Social Networks: Volume 6: No. 3 JULY 2009Document8 pagesAdolescent Obesity and Social Networks: Volume 6: No. 3 JULY 2009Martha Patricia López PimentelNo ratings yet

- TitleDocument2 pagesTitlewong bryanNo ratings yet

- 523 Qualitative PaperDocument16 pages523 Qualitative Paperapi-293223028No ratings yet

- Association Between Social Media Exposure To Food and Beverages With Nutrient Intake of Female AdolescentsDocument8 pagesAssociation Between Social Media Exposure To Food and Beverages With Nutrient Intake of Female AdolescentsPuttryNo ratings yet

- Heather M. MacleanDocument8 pagesHeather M. MacleanAndriy TretyakNo ratings yet

- The Pursuit of Wellness Social Media, Body Image and Eating DisordersDocument8 pagesThe Pursuit of Wellness Social Media, Body Image and Eating DisordersasterisbaNo ratings yet

- Vague BookingDocument9 pagesVague BookingAdriana MeloNo ratings yet

- SNS NowDocument2 pagesSNS NowTirade RuefulNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Association Between Social Media Use and Depression Among U.S. Young AdultsDocument9 pagesResearch Article: Association Between Social Media Use and Depression Among U.S. Young AdultsAisyah IzzatiNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument14 pagesResearch Paperapi-545898677No ratings yet

- Dr. Maria D. Pastrana National High School: The Effect of Exposure To Food in Social NetworksDocument8 pagesDr. Maria D. Pastrana National High School: The Effect of Exposure To Food in Social NetworksAbelle Paula MalusayNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Eng 105 Shannon FinalDocument9 pagesResearch Paper Eng 105 Shannon Finalapi-318646783No ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Orthorexia Nervosa AnxietDocument8 pagesThe Relationship Between Orthorexia Nervosa AnxietAlexandru CulceaNo ratings yet

- Kantar Modern Marketing Dilemmas 2023Document55 pagesKantar Modern Marketing Dilemmas 2023Alexandru CulceaNo ratings yet

- PangTony Thesis2017Document81 pagesPangTony Thesis2017Alexandru CulceaNo ratings yet

- The Habitual ConsumerDocument15 pagesThe Habitual ConsumerAlexandru CulceaNo ratings yet

- Col 225891Document14 pagesCol 225891Alexandru CulceaNo ratings yet

- BonnardelPiolatLeBigot DisplaysDocument14 pagesBonnardelPiolatLeBigot DisplaysAlexandru CulceaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Indoor Color On Mood and Cognitive Performance: Building and Environment September 2007Document9 pagesEffects of Indoor Color On Mood and Cognitive Performance: Building and Environment September 2007Alexandru CulceaNo ratings yet

- (The New Library of Psychoanalysis) Rosine Jozef Perelberg - Time, Space and Phantasy-Routledge (2008)Document244 pages(The New Library of Psychoanalysis) Rosine Jozef Perelberg - Time, Space and Phantasy-Routledge (2008)Alexandru CulceaNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Color On Student EmotioDocument11 pagesThe Influence of Color On Student EmotioAlexandru CulceaNo ratings yet

- Colors and Emotions Preferences and CombinationsDocument14 pagesColors and Emotions Preferences and CombinationsAlexandru CulceaNo ratings yet

- MindfulnessandwellbeingDocument18 pagesMindfulnessandwellbeingAlexandru CulceaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan - Present ContinuousDocument3 pagesLesson Plan - Present Continuoussarah mNo ratings yet

- Boost Your Vocabulary Cam18 (PDF - Io)Document10 pagesBoost Your Vocabulary Cam18 (PDF - Io)phanthithanhtam5503No ratings yet

- Swot Analysis SlimeDocument8 pagesSwot Analysis SlimeIzzatul KamilaNo ratings yet

- High Carbs - Google SearchDocument1 pageHigh Carbs - Google SearchJenemiah GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Future-Going-To - WILL Ppt-Fun-Activities-GamesDocument14 pagesFuture-Going-To - WILL Ppt-Fun-Activities-GamesCamilo Andres Silva CedeñoNo ratings yet

- Article Millet BreadDocument21 pagesArticle Millet BreadNANGUITA EMMANUELNo ratings yet

- ...Document3 pages...credit analystNo ratings yet

- Statistics HomeworkDocument2 pagesStatistics HomeworkasdNo ratings yet

- Bài tập câu so sánh lớp 9Document2 pagesBài tập câu so sánh lớp 9Cẩm Ly NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Albuquerque Visitors GuideDocument84 pagesAlbuquerque Visitors GuideCeela McElveny100% (1)

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Mathematics 4 BaDocument7 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in Mathematics 4 BaAlezandraNo ratings yet

- N14M79 Business EconomicsDocument18 pagesN14M79 Business Economicskala1975No ratings yet

- Significance of Culture in International BusinessDocument20 pagesSignificance of Culture in International BusinessSarada kNo ratings yet

- NAME: Reneil James D. Gutierrez Section: BSIT-1C NAME: Al Francis Cortez Bake A BreadDocument11 pagesNAME: Reneil James D. Gutierrez Section: BSIT-1C NAME: Al Francis Cortez Bake A BreadAl Francis Cortez100% (1)

- Which One Is Different Why Instructions 0 PDFDocument2 pagesWhich One Is Different Why Instructions 0 PDFMarini BudiartiNo ratings yet

- Millets and Grains - Glossary in English and Hindi My Weekend Kitchen 2Document1 pageMillets and Grains - Glossary in English and Hindi My Weekend Kitchen 2Nitin AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Chopping BoardDocument8 pagesIntroduction To Chopping BoardAshraf ZhafryNo ratings yet

- Organic Aquaculture DossierDocument36 pagesOrganic Aquaculture DossierManish KumarNo ratings yet

- Rhetorical Analysis Final DraftDocument5 pagesRhetorical Analysis Final Draftapi-2391557210% (1)

- Focgb1 Ak Utest DLR 2Document1 pageFocgb1 Ak Utest DLR 2Оля ОляфкаNo ratings yet

- The Kitchen Brigade: by Auguste EscoffierDocument31 pagesThe Kitchen Brigade: by Auguste EscoffierPaaralan Ng Paclasan100% (1)

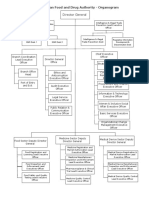

- EFDA Organogram English VersionDocument6 pagesEFDA Organogram English VersionRobsan YasinNo ratings yet

- Enabling Butanol Production From Crude Sugarcane Bagasse Hemicellulose PDFDocument6 pagesEnabling Butanol Production From Crude Sugarcane Bagasse Hemicellulose PDFDawson AbigailNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12: Picked It UpDocument20 pagesChapter 12: Picked It UpsaducsNo ratings yet

- Unit IV - Representatives Philippine Theatrical FormsDocument58 pagesUnit IV - Representatives Philippine Theatrical FormsHaydee CarpizoNo ratings yet

- The Winx: Lê Nguyễn Phạm Hải ÂU Đặng Trần Băng Nhi Nguyễn Thị Uyển NHI Phan Thúy Quyên Phan Lê Trúc QuỳnhDocument42 pagesThe Winx: Lê Nguyễn Phạm Hải ÂU Đặng Trần Băng Nhi Nguyễn Thị Uyển NHI Phan Thúy Quyên Phan Lê Trúc QuỳnhTrúc QuỳnhNo ratings yet

- Touchstone 2 Workbook (PDFDrive) - 2-5Document4 pagesTouchstone 2 Workbook (PDFDrive) - 2-5ELAINE JUDITH RODRIGUEZ CASTILLONo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan (DLP) Format: Instructional PlanningDocument2 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan (DLP) Format: Instructional PlanningIvy Talisic100% (1)

- Foodpyramid ReportDocument6 pagesFoodpyramid ReportMariane EspiñoNo ratings yet

- The Task of Passive VoiceDocument2 pagesThe Task of Passive VoiceAnnisa AnindyaNo ratings yet