Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Practice: A Practical Guide To Endodontic Access Cavity Preparation in Molar Teeth

Uploaded by

ivanna parralesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Practice: A Practical Guide To Endodontic Access Cavity Preparation in Molar Teeth

Uploaded by

ivanna parralesCopyright:

Available Formats

IN BRIEF

PRACTICE

• Emphasises the anatomy of molar teeth in relation to endodontic treatment.

• Discusses the assessment of teeth prior to commencing endodontic treatment. VERIFIABLE

• Describes common problems encountered when preparing access cavities and how to CPD PAPER

overcome them.

A practical guide to endodontic access cavity

preparation in molar teeth

S. Patel1 and J. Rhodes2

The main objective of access cavity preparation is to identify the root canal entrances for subsequent preparation and

obturation of the root canal system. Access cavity preparation can be one of the most challenging and frustrating aspects

of endodontic treatment, but it is the key to successful treatment. Inadequate access cavity preparation may result in dif-

ficulty locating or negotiating the root canals. This may result in inadequate cleaning, shaping and filling of the root canal

system. It may also contribute to instrument separation and aberrations of canal shape. These factors may ultimately lead

to failure of treatment. Good access cavity design and preparation is therefore imperative for quality endodontic treat-

ment, prevention of iatrogenic problems, and prevention of endodontic failure (Fig. 1).

The aim of this paper is to present a sim- • Pre-treatment assessment A pre-operative periapical radiograph

ple guide to preparing access cavities • Preparation of the tooth for of the tooth taken with a beam-aim-

in molar teeth, and how to identify and endodontic treatment ing device to ensure no image distor-

avoid potential complications. • Removal of the roof of the pulp tion should be studied, along with any

The ‘ideal’ access cavity frequently chamber and coronal pulp tissue relevant bitewing radiographs. In some

described in endodontic textbooks • Creating straight line access. instances it may be helpful to take addi-

usually show easily identifiable canal tional angled periapical radiographs to

entrances at the base of a large pulp Pre-treatment assessment

floor (Fig. 2). In the past, access cavities The likelihood of gaining adequate

tended to be standardised depending on access for endodontic treatment should

tooth type, however with modern endo- be determined during treatment plan-

dontic techniques, a dental operating ning. If access to the tooth is difficult

microscope and loupes providing mag- treatment may be compromised. This

nification and better illumination, an is likely to be even more relevant with

access cavity is now mostly dictated by complex re-treatment procedures. Once

the individual pulp chamber morphol- accessibility has been confirmed, it is

ogy of the tooth being treated. necessary to mentally visualise the loca-

Access cavity preparation may be tion of the pulp chamber. The angulation

divided into four stages: and any rotation of the tooth or coro-

nal restoration in relation to the roots

should be assessed as this will have a

Specialist Endodontist, 45 Wimpole Street, London,

1*

W1G 8SB; 2Specialist Endodontist, 15 Penn Hill Avenue,

bearing on the design of the access cav-

Parkstone, Poole, Dorset, BH14 9LU ity. The position of the cemento-enamel

*Correspondence to: Dr Shanon Patel junction and furcation should also be

Email: shanonpatel@hotmail.com

noted as these landmarks help indi-

Refereed Paper cate the location of the level of the pulp Fig. 1 Good access cavity design results in

Accepted 16 October 2006

floor and the probable position of the identification and subsequent disinfection and

DOI: 10.1038/bdj.2007.682

©

British Dental Journal 2007; 203: 133-140 canal entrances. obturation of the entire root canal system

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 203 NO. 3 AUG 11 2007 133

© 2007 Nature Publishing Group

PRACTICE

a b

Fig. 2 Access cavity of a lower first molar;

note the three canal orifices are connected

by developmental (dark) lines. These lines are Figs 5a-c (a) Top to bottom, standard probe,

sometimes referred to as the ‘dentine map’ a DG16 endodontic explorer and a long shank

small spooned excavator. (b) Operating dental

microscope with an observer-scope for the

dental assistant (Global Surgical Corporation,

St. Louis, USA). (c) Loupes with a fibre optic

light source (Global Surgical Corporation,

St. Louis, USA)

a

separate the different roots which may root canal entrances being more chal-

otherwise be superimposed over each lenging (Fig. 4).

other. From these radiographs the posi-

tion, size, depth and shape of the pulp Preparation of the tooth for

chamber, position of the pulp horns, endodontic treatment

number of roots and the degree of cur- A front surface mirror, DG16 endodon-

vature can be assessed. tic probe, long shank small excavator,

Careful assessment of pre-treatment magnification and good illumination

radiographs may indicate potential are essential for endodontic treatment

challenges to canal identification. Large (Figs 5a-c).

b pulp spaces and obviously patent canal Caries and failing restorations must

entrances may be common in younger be completely removed prior to prepar-

Figs 3a-b (a) Lower first molar with signifi- patients, but as teeth age, secondary den- ing the access cavity. If at the pre-treat-

cantly reduced pulp chamber height, pulp tine is laid down resulting in a reduction ment assessment stage there is any doubt

calcifications and signs of canal sclerosis;

this tooth will be more challenging to access. in the pulp chamber volume, and size of regarding the restorability of the tooth,

(b) The canals in this upper first molar tooth the root canal lumen. This often results the existing restoration should be com-

appear to be completely sclerosed in the loss of helpful anatomical land- pletely removed to confirm that there

marks and changes in the shape of the is sufficient tooth substance remaining

pulp chamber which will be unique to (Figs 6a-e). Removal of existing resto-

each tooth. rations may also reveal hairline cracks

The dimensions of the pulp chamber on one or more axial walls which could

and location of the root canal entrances influence the endodontic prognosis and

will also be influenced by the amount the design of the future post-endodontic

and position of tertiary dentine depos- restoration (Fig. 7).

ited as a specific response to caries, mic- Unsupported cusps should be removed

roleakage and tooth surface loss over or protected by placing an orthodontic

the course of a tooth’s life (Figs 3a-b). band around the tooth to prevent cusp

These insults on the pulp may have a fracture during and immediately after

dramatic effect on the size and shape of treatment. In some cases, following

the pulp chamber. Canal entrances may dismantling of the coronal restoration,

also become obstructed by pulp stones it may be necessary to place a provi-

Fig. 4 Pulp calcifications obscuring the and other dystrophic calcifications, sional restoration to fi rstly aid rubber

canal orifices

resulting in the identification of the dam placement, and secondly create

134 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 203 NO. 3 AUG 11 2007

© 2007 Nature Publishing Group

PRACTICE

a

Fig. 7 Removing the entire restoration reveals a

crack (red arrow) and caries in the mesial box

d a

b

b

Figs 6a-e (a) WamKey (Dentsply Maillefer

Instruments, Ballaigues, Switzerland) can be

used to atraumatically and quickly remove

crowns, (b) a slot is prepared on the buccal

aspect just below the fit surface of the occlu-

sal aspect of this metal-ceramic crown. (c) Figs 8 a-b (a) left to right, #2 round diamond

The WamKey is inserted into the access hole bur, tungsten carbide fissure bur, Endo Z bur,

and rotated, (d) the crown comes off in one Axxcess bur and #2 tungsten carbide round

piece. (e) The existing restoration is removed bur, the last two burs (SybronEndo, Orange,

to reveal an unrestorable tooth. If the tooth CA, USA) have a longer shank and allow better

had been restorable the existing crown may vision when used with magnification. (b) Close

c have been used as a temporary crown up of the non-end cutting Endo-Z bur (Dentsply

Maillefer Instruments, Ballaigues, Switzerland)

a reservoir for irrigant solution in the carbide bur to reduce the likelihood of ledges/lips are present.

access cavity. porcelain fracture (Fig. 8). It is always Careful inspection of the pulp cham-

wise to warn the patient that the crown ber floor of molar teeth will reveal subtle

Removal of the roof of the pulp chamber may be irreversibly damaged and may changes in the colour of the dentine which

and coronal pulp tissue need replacement following endodon- aid identification of the canal entrances

The roof of the pulp chamber should be tic treatment. Once the roof of the pulp (Fig. 2). Dark developmental lines may be

penetrated through the central portion of chamber has been breached, the bur will identified linking canal entrances and the

the crown, at a point where the roof and suddenly drop into the pulp chamber location of an undetected canal entrance

floor of the pulp chamber are at the wid- space (Figs 9a-d). may be indicated by tracking along the

est; this commonly occurs at the point To prevent damage to the floor of the developmental line. The canal entrance

where the pulp horn relating to the larg- pulp chamber a non end-cutting bur (for will appear as a small area of white

est canal is situated (for example, palatal example, Endo-Z bur [Dentsply Maillefer opaque dentine against a background

root in maxillary molars and distal canal Instruments, Ballaigues, Switzerland]) of yellow/grey secondary dentine. The

of mandibular molars). Tungsten carbide is then used to remove the entire roof tiny canal entrance will feel sticky when

burs are ideal for cutting through metal; of the pulp chamber. The walls of the probed with a DG16 endodontic probe.

however, a diamond bur should be used access cavity should be probed to ensure

to map out the access in porcelain fused that the roof of the pulp chamber has Creating straight line access

to metal crowns before using a tungsten been completely removed, ie no dentine Once the canal entrance(s) have been

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 203 NO. 3 AUG 11 2007 135

© 2007 Nature Publishing Group

PRACTICE

a c

b d

Figs 9 a-d (a, b) The roof of the pulp chamber has been penetrated using a tungsten carbide bur;

(c) an ‘Endo-Z’ bur has been used to completely remove the roof of the pulp chamber. (d) All canals

readily identifiable

identified it may be necessary to refi ne/ the tooth. Even when the canals have

modify the shape of the access cavity been located another challenge may be

to allow endodontic files to have unim- their negotiation.

peded (straight line) access into the A well-positioned mouth prop and a

coronal-third of the root canal. children’s fast handpiece which has a

Straight line access will reduce the smaller head will significantly improve

likelihood of iatrogenic problems such access and treatment. Standard length b

as zips, elbows and ledges being cre- friction grip burs may also be short-

ated by large (and therefore inflexible) ened with a tungsten carbide bur by 3-

stainless steel files as they attempt to 4 mm and used in combination with a

straighten in curved canals, and will children’s head handpiece to give even

also allow easier insertion of rotary greater access (Fig. 12). Reducing the

instruments during preparation (Figs height of the buccal cusp tips by 2-3 mm

10a-c). Straight line access is essential prior to accessing the pulp chamber will

when using nickel-titanium instruments. increase the inter-cuspal distance and

Although these instruments are very improve the visibility and accessibility.

flexible, poor straight line access may

result in the files’ distortion and even- Full coverage restorations

tual separation due to cyclic fatigue It is not uncommon for molar teeth c

(Fig. 11). requiring endodontic treatment to be

already restored with crowns. Without Figs 10 a-c (a) Inadequate straight line access

resulting in the tip of the file attempting to

COMMON PROBLEMS adequate magnification and illumina- straighten itself (red arrow). (b) Refining the

Limited access tion the access cavity will be nothing shape of the access cavity results in unim-

Limited mouth opening and/or an more than a black hole. Subtle colour peded, straight line access into the root canal.

(c) The mesio-buccal corner of the access

unfavourably positioned tooth may changes of the dentine on the floor of cavity has been modified (red arrow) to ensure

result in difficulty to correctly align the pulp chamber and other anatomi- straight line access into the mesiobuccal canal

the handpiece along the long axis of cal signs indicating the position of the of this lower molar

136 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 203 NO. 3 AUG 11 2007

© 2007 Nature Publishing Group

PRACTICE

Fig. 11 Separation of a nickel-titanium rotary

instrument due to inadequate straight line

access of the mesio-buccal in the upper left

first molar

a c

Figs 13 a-c (a) The crown on this upper right

molar masks the true position of the tooth,

upon removing the crown the actual position

of the tooth becomes evident. (b) Failure to

remove the crown would have most probably

led to failure to locate all the root canals and

perforation. (c) Post-obturation radiograph

Fig. 12 The handpiece (KaVo 637 Bellatorque,

KaVo Dental GmbH, Biberach, Germany) on

the left has a smaller head, when used with a

shortened bur it makes accessing molar teeth

easier on patients with restricted opening

canal entrances will be difficult to iden- b

tify. This may further be complicated by

the crown masking the orientation of

the tooth (Figs 13 a-c). If the canals can- progressively flatter which results in the to confirm that the access cavity is being

not be identified it may be necessary to canals entrances becoming narrower prepared in the correct direction and

remove the crown. Removing the crown and thus harder to locate (Fig. 14). secondly to assess how much dentine has

will also reduce the likelihood of remov- Tertiary dentine overlying the canal been removed. If necessary rubber dam

ing sound dentine unnecessarily and entrances may be differentiated from should not be applied until the canal(s)

also reduce the chances of perforation. physiological secondary dentine by its have been identified to ensure that access

whiter/opaque appearance compared cavity preparation is following the long

Calcifications within the pulp chamber to the yellow/grey colour of secondary axis of the root(s), and also reduce the

The cumulative effects of ageing and dentine. Long shank burs or ultrasonic likelihood of perforating the pulpal floor.

the consequences of restorative den- tips should be used with a gentle brush Once the canal entrance(s) have been

tistry reduce the pulp chamber volume stroke action to remove tertiary dentine. located, rubber dam should be applied.

due to the deposition of secondary den- Pulp stones and calcifications are best Once a canal has been identified with

tine. Localised deposition of tertiary removed with small long shank excava- a DG16 probe, a small file (size 06 or

dentine as a specific response to car- tors or ultrasonic endodontic tips (Figs 08) with lubricant (for example Glyde®)

ies, microleakage and tooth surface 15a-b). Once the canal entrance has been [Dentsply Maillefer Instruments, Bal-

loss will also reduce the volume of the exposed it will feel sticky when probed laigues, Switzerland]) should gently

pulp chamber. The natural dome shape with a DG16 probe. be used in a watch winding action to

of the pulp chamber floor will become Often it is prudent to take a radiograph negotiate the canal entrance. It may be

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 203 NO. 3 AUG 11 2007 137

© 2007 Nature Publishing Group

PRACTICE

a

a

Fig. 14 The deposition of tertiary dentine has

resulted in the pulp floor and roof becoming

closer. The mesial canals project distally in the b

coronal aspect of the tooth (red arrow). Den-

tine will need to be removed in order achieve b

straight line access (blue arrow)

Figs 15 a-b (a) Left to right, a BUC 1 ultra-

sonic endodontic tip (SyronEndo, Orange, CA,

necessary to precurve small fi les to USA), Standard #4 rose head bur and long

negotiate the canal. Various manufactur- shank #4 rose head bur. The ultrasonic tip and

ers have specifically designed hand fi les the long shank bur are ideal for removing small

amounts of dentine from the floor of the pulp

to aid negotiation of sclerosed canals. chamber. (b) Ultrasonic endodontic tip in use

Rigid ‘C-Pilot’ files (VDW Endodontic

Synergy, Munich, Germany) have a cut-

c

ting tip and are ideal to gently negotiate slightly to the buccal of the mesio-lin-

sclerosed canals as they are less likely gual cusp tip. The mesial canals com- Figs 16 a-c (a) Size 08 ‘C-Pilot’ file (top), and

a size 10 Senseus Profinder stainless steel files

to distort or buckle compared to regular monly curve distally, this may result in for negotiating sclerosed canals (bottom). (b)

stainless steel files (Fig. 16). If the canal the mesio-buccal canal being challeng- White opaque tertiary dentine indicates canal

is completely sclerosed for several mil- ing to identify and negotiate as the canal orifice (red arrow) (c) #08 C-Pilot file is used

to gently negotiate the canal. Irrigating with

limetres apical to the pulp floor, instru- follows a mesial course coronally and sodium hypochlorite and ethylene diamine-

ments should be advanced gradually then changes to a distal direction half to tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) will aid canal penetra-

and a confirmatory radiograph taken to two-thirds of the way down the canal. tion and negotiation

ascertain the orientation of the instru- Approximately 5% of mandibular

ment within the canal. molar teeth have three mesial canals, rarely necessary to extend the access

the third mesial (middle mesial) canal is distally beyond the midline as the angu-

MANDIBULAR MOLAR TEETH usually located between the mesio-buc- lation of the distal root allows straight

First molars cal and mesio-lingual canals (Figs 18a- line access.

Mandibular molar teeth usually have d). This middle mesial canal is usually Approximately 5% of molar teeth have

two roots in which there are commonly located along the developmental groove a third (disto-lingual) root. As well as

three or four root canals. The mesial between the mesio-buccal and mesio- being evident on a pre-operative radi-

root almost always has two mesial lingual canals. ograph, careful widening (bucco-lin-

canals (mesio-buccal and mesio-lingual) The distal canal(s) are located just dis- gually) of the distal canal may reveal a

linked by a developmental groove. tal of the buccal developmental groove; second distal canal entrance.

Approximately 60% of distal roots the canal entrance is usually oval in

have only one canal, and the remain- shape if there is only one canal present. Second molars

ing 40% have two canals (disto-buccal If two canals are present then the canal The anatomy of second molar teeth var-

and disto-lingual). entrances tend to be rounder and are usu- ies more than that of first molars, and

The canals are more readily accessible ally connected by an isthmus. As with the incidence of two distal canals in

when the access cavity outline is rec- the mesial canals they tend to be located second mandibular molar teeth is less

tangular or trapezoid, depending on the an equal distance away from the mesio- than in first molars. The pulp chamber

number of canals present (Figs 17 a-b). distal mid-line of the tooth. The distal volume and canal entrances are smaller

The mesio-buccal canal entrance is usu- canal entrances tend to be much closer than in fi rst molars.

ally located under the mesio-buccal cusp together than the mesial canal entrances, In a small proportion of mandibular

tip, and the mesio-lingual canal will be and once prepared may be confluent. It is second molar teeth the roots may be

138 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 203 NO. 3 AUG 11 2007

© 2007 Nature Publishing Group

PRACTICE

fused resulting in one main C-shaped

canal (in cross section) once preparation

has been completed.

MAXILLARY TEETH

First molars

Maxillary molar teeth usually have

three roots, with three or four canals.

The palatal and disto-buccal roots each

have one canal. Approximately 90% and

45% of maxillary first and second molar

teeth respectively have two mesio-buc-

cal canals (MB1 and MB2) in the mesio- a

buccal root.

The access cavity should be rhom-

boidal in outline, and positioned in the

mesial two-thirds of the tooth. The pala-

tal canal entrance is the largest canal

and is located in the middle of the pala-

tal half of the tooth and is usually the

easiest canal to locate due to its size

and position. The palatal canal usu-

ally curves buccally in its apical-third,

often resulting in the estimated working

length determined from the pre-opera-

tive radiograph being shorter than the

true length as determined with an apex

locator. The disto-buccal canal has a b

round canal entrance and is usually the

shortest and straightest of the canals. It Figs 17 a-b (a) Access cavity and radiograph of a lower first molar tooth three canal orifices, note

that the mesio-buccal and mesio-lingual canals are found approximately the same distance from

is located just distal to the buccal groove the midline (mesial to distal) of the tooth (yellow line). (b) Access cavity and radiograph of a lower

and slightly more palatal than the first molar with four root canals, note that the buccal and lingual canals can be found on either

mesio-buccal(s). side of the mesial to distal mid-line (yellow line) of the tooth. If an imaginary line is joined between

the buccal and lingual canal entrances (yellow dots) it will intersect the mesial-to-distal mid-line

The mesio-buccal root is flatter (mesio- at right angles. The distal canal orifices are closer to the midline than their mesial counterparts

distally) resulting in the mesio-buccal

canal entrances being ribbon-shaped.

Care must be taken to prevent the mesio-

buccal canals being over prepared mesio-

distally. The MB1 is located just palatal

to the mesio-buccal cusp tip.

The MB2 can be challenging to locate

and ideally should be identified once the

fi rst three canals have been prepared. It

is usually located within 2 mm of the a c

MB1, between the MB1 entrance and

the palatal canal entrance. The canal

entrance is usually covered with a ridge

of dentine which has to be removed

before the MB2 can be identified. Ultra-

sonic tips and/or small rose head burs

(LN Burs) are ideal to gently remove

this ridge of dentine covering the MB2

canal entrance. The MB2 opening will b

feel sticky when probed with a DG16

(Figs 19 a-e).

Figs 18 a-d (a) Middle mesial canal on the

The MB2 and to a lesser extent the MB1 developmental groove between the mesio-

may be challenging to instruments as buccal and mesio-lingual canals, (b) #06 file

they are commonly curved. Small sized is used to negotiate the middle mesial canal,

(c) post-obturation of three mesial and two d

files are required to initially negotiate distal canals, (d) post-obturation radiograph

these narrow and tortuous canals. Below

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 203 NO. 3 AUG 11 2007 139

© 2007 Nature Publishing Group

PRACTICE

a d

Fig. 20 The canal orifices in upper second

molar teeth tend to be closer together

an operator to identify the root canals

entrances in molar teeth, however noth-

ing can substitute the experience and

knowledge gleaned from practice both in

a clinical environment and on extracted

teeth. Successful access cavity prepara-

tion relies on a sound knowledge of the

b internal and external anatomy of teeth.

The importance of gaining straight

line endodontic access cannot be over-

emphasised. Ultimately poor access

e cavity design could lead to inadequate

cleaning, shaping and obturation com-

promising successful outcome.

Thank you to Oxford University Press for Figs

10 a-b, which are taken from Principles of endo-

dontics by Michael Manogue, Shanon Patel and

Richard Walker, 2005. Thanks also to Dr B. S.

c Chong for his help and advice in the preparation

of this article.

Figs 19 a-e (a) Three root canals have been identified and prepared in this maxillary first molar,

the second mesio-buccal (MB2) canal is usually located within 2 mm of the first mesio-buc- Further reading

cal, between this canal and the palatal canal. (b) A BUC 1 ultrasonic endodontic tip is ideal to 1. Kulid J C, Peters D D. Incidence and configuration

remove the lip of dentine that may be covering this fourth root canal orifice, it may also be of canal systems in the mesiobuccal root of maxil-

used to make a 1-2 mm deep trough between the first mesio-canal and palatal canal exposing lary first and second molars. J Endod 1990; 16:

311-317.

the entrance of the second mesio-buccal canal. (c) An 06 sized file is ideal to explore the canal,

2. Manning S A. Root canal anatomy of mandibular

note that the canal is entered from the distal aspect. (d) All four canals ready to be obturated, second molars. Part II C shaped canals. Int Endod J

(f) post treatment radiograph 1990; 23: 40-45.

3. Pineda F, Kuttler Y. Mesiodistal and buccolingual

roentgenograhic investigation of 7,275 root

canals. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol

the canal entrance it is not uncommon all three or four root canal entrances Endod 1972; 33: 101-110.

for the MB2 to follow a mesial direction lying along the same line between the 4. Pitt Ford T R, Torabinejad M, McKendry D J et al.

Use of mineral trioxide aggregate for repair of

which changes to a distal direction half mesio-buccal and palatal canals. The furcal perforations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol

way down the canal. floor of the access cavity is also more Oral Radiol Endod 1995; 79: 756-762.

5. Skidmore A E, Bjorndal A M. Root canal anatomy

domed-shaped. of the human mandibular first molar. Oral Surg

Second molars Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1971; 32:

The roots of second molars tend to be CONCLUSION 778-784.

6. Stropko J J. Canal morphology of maxillary molars:

closer or even fused together, hence the The use of magnification, illumina- clinical observations of canal configurations. J

canal entrances in second molar teeth tion and specialised items of equipment Endod 1999; 25: 446-450.

7. Yoshioka T, Kobayashi C, Suda H. Detection rate of

tend to be located more closely to each (for example, ultrasonic endodontic root canal entrances with a microscope. J Endod

other (Fig. 20). It is not usual to fi nd tips) greatly improves the ability of 2002; 28: 452-453.

140 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 203 NO. 3 AUG 11 2007

© 2007 Nature Publishing Group

You might also like

- A Practical Guide To Endodontic Access Cavity Preparation in Molar TeethDocument8 pagesA Practical Guide To Endodontic Access Cavity Preparation in Molar TeethAlireza RaieNo ratings yet

- A Practical Guide To Endodontic Access Cavity PrepDocument19 pagesA Practical Guide To Endodontic Access Cavity PrepRajeev GargNo ratings yet

- Borkar 2015Document6 pagesBorkar 2015Jing XueNo ratings yet

- Articol PivotDocument7 pagesArticol PivotDragos CiongaruNo ratings yet

- Endodontic Access Preparation The Tools For SuccessDocument9 pagesEndodontic Access Preparation The Tools For SuccessAna YUNo ratings yet

- Endodontic Surgery: Verifiable CPD PaperDocument10 pagesEndodontic Surgery: Verifiable CPD PaperSoal KoasNo ratings yet

- Access Cavity Part 2Document73 pagesAccess Cavity Part 2mrbyy619No ratings yet

- Intricate Internal Anatomy of Teeth and Its Clinical Significance in Endodontics - A ReviewDocument10 pagesIntricate Internal Anatomy of Teeth and Its Clinical Significance in Endodontics - A ReviewManjeevNo ratings yet

- FulltextDocument5 pagesFulltextaulia zahroNo ratings yet

- 107 Nonsurgical Endodontic Therapy of A Dens InvaginatusDocument3 pages107 Nonsurgical Endodontic Therapy of A Dens InvaginatusAurelian DentistNo ratings yet

- Guided Endodontic Access in A Maxillary Molar Using A Dynamic Navigation SystemDocument5 pagesGuided Endodontic Access in A Maxillary Molar Using A Dynamic Navigation SystemAlex KesumaNo ratings yet

- Endodontic Treatment of Curved Root Canal Systems PDFDocument3 pagesEndodontic Treatment of Curved Root Canal Systems PDFRăican AlexandruNo ratings yet

- Enhanced Retention of A Maxillofacial Prosthetic Obturator Using Precision Attachments: Two Case ReportsDocument6 pagesEnhanced Retention of A Maxillofacial Prosthetic Obturator Using Precision Attachments: Two Case ReportsAmalorNo ratings yet

- Restoring Proximal Caries Lesions Conservatively With Tunnel RestorationsDocument8 pagesRestoring Proximal Caries Lesions Conservatively With Tunnel RestorationsyesikaichaaNo ratings yet

- Rotational Path Removable Partial Denture DesignDocument7 pagesRotational Path Removable Partial Denture DesignNapatsorn RakpakwanNo ratings yet

- Endodontic Treatment of Mandibular Second Molar With Diversed Root Canal AnatomyDocument3 pagesEndodontic Treatment of Mandibular Second Molar With Diversed Root Canal AnatomyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Access Procedures:: Breaking and Entering Safely and EffectivelyDocument4 pagesAccess Procedures:: Breaking and Entering Safely and EffectivelyKalpanaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Case Reports - 2023 - Vyver - Apexification of Dens Evaginatus in A Mandibular Premolar A Case ReportDocument6 pagesClinical Case Reports - 2023 - Vyver - Apexification of Dens Evaginatus in A Mandibular Premolar A Case ReportIqra KhanNo ratings yet

- Jurnal KasusDocument4 pagesJurnal KasusDena SeptianiNo ratings yet

- Guided Endodontics for Complex Molar Cases with Calcified CanalsDocument7 pagesGuided Endodontics for Complex Molar Cases with Calcified CanalsJulia PimentelNo ratings yet

- Access Cavity PreparationDocument7 pagesAccess Cavity Preparationnorma paulina carcausto lipaNo ratings yet

- 116 Guidelines For Access CavityDocument8 pages116 Guidelines For Access CavityYodha AdityaNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Radiograph in Endodontics PDFDocument6 pagesPreoperative Radiograph in Endodontics PDFZain AlnahamNo ratings yet

- EMI. Khademi, ClarkDocument11 pagesEMI. Khademi, ClarkMaGe IsTeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 27Document115 pagesChapter 27dorin_1992No ratings yet

- Endodontic Treatment of Mandibular Premolars With Complex Anatomy Case SeriesDocument5 pagesEndodontic Treatment of Mandibular Premolars With Complex Anatomy Case SeriesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Maxillary Second Molar With Four Roots and Five Canals: SciencedirectDocument5 pagesMaxillary Second Molar With Four Roots and Five Canals: SciencedirectKanish AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Root Perforations: Aetiology, Management Strategies and Outcomes. The Hole TruthDocument10 pagesRoot Perforations: Aetiology, Management Strategies and Outcomes. The Hole TruthGladis Aprilla RizkiNo ratings yet

- Case Report EndodonticsDocument49 pagesCase Report EndodonticsFrancis PrathyushaNo ratings yet

- Asalaam Alekkum: DR Gaurav Garg, Lecturer College of Dentistry, Al Zulfi, MUDocument57 pagesAsalaam Alekkum: DR Gaurav Garg, Lecturer College of Dentistry, Al Zulfi, MUMaGe IsTeNo ratings yet

- Endodontic Managementof Fourrootedpremolar JCD2013Document4 pagesEndodontic Managementof Fourrootedpremolar JCD2013Lucas PeixotoNo ratings yet

- Limitations-and-Management-of-Dynamic-Navigation-SDocument10 pagesLimitations-and-Management-of-Dynamic-Navigation-SchannadrasmaNo ratings yet

- 31 Ijss Nov cr02 - 2018Document4 pages31 Ijss Nov cr02 - 2018RAfii KerenNo ratings yet

- Adts Guidelines For Access CavityDocument9 pagesAdts Guidelines For Access CavityOmuraiNo ratings yet

- IJEDe 16 01 ScolavinoPaolone 722 3Document24 pagesIJEDe 16 01 ScolavinoPaolone 722 3Mauri EsnaNo ratings yet

- Telescopic Overdenture: A Case Report: C. S. Shruthi, R. Poojya, Swati Ram, AnupamaDocument5 pagesTelescopic Overdenture: A Case Report: C. S. Shruthi, R. Poojya, Swati Ram, AnupamaRani PutriNo ratings yet

- Endodontic Cavity PreparationDocument166 pagesEndodontic Cavity Preparationagusaranp0% (1)

- Tooth-Support Over Dentures: An Approach To Preventive ProsthodonticsDocument5 pagesTooth-Support Over Dentures: An Approach To Preventive ProsthodonticsAdvanced Research PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Oke 4Document3 pagesOke 4Maika RatriNo ratings yet

- Endodontic AccessDocument5 pagesEndodontic AccessShyambhavi SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Articulo de Endodoncia PDFDocument14 pagesArticulo de Endodoncia PDFJuan Pablo Rondon OyuelaNo ratings yet

- Endo PDFDocument91 pagesEndo PDFPolo RalfNo ratings yet

- Access Procedures: Tips for Safe and Effective Root Canal EntryDocument4 pagesAccess Procedures: Tips for Safe and Effective Root Canal EntryMonica Ioana TeodorescuNo ratings yet

- Managing Missing Mandibular PremolarsDocument4 pagesManaging Missing Mandibular PremolarsKanish AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Endoguide 5676Document5 pagesEndoguide 5676Ruchi ShahNo ratings yet

- Endodontic and Restorative Management of A Lower Molar With A Calcified Pulp Chamber.Document7 pagesEndodontic and Restorative Management of A Lower Molar With A Calcified Pulp Chamber.Nicolas SantanderNo ratings yet

- Int Endodontic J - 2022 - Clauder - Present Status and Future Directions Managing PerforationsDocument20 pagesInt Endodontic J - 2022 - Clauder - Present Status and Future Directions Managing Perforationsjorge2412No ratings yet

- A P A O F S: Ndodontic Ccess Reparation N Pening OR UccessDocument7 pagesA P A O F S: Ndodontic Ccess Reparation N Pening OR UccessHadil AltilbaniNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Joen 2020 11 002Document22 pages10 1016@j Joen 2020 11 002alondraNo ratings yet

- An Alternative Solution For A Complex Prosthodontic Problem: A Modified Andrews Fixed Dental ProsthesisDocument5 pagesAn Alternative Solution For A Complex Prosthodontic Problem: A Modified Andrews Fixed Dental ProsthesisDragos CiongaruNo ratings yet

- JIDA EndodonticsArticleDocument11 pagesJIDA EndodonticsArticleSilviu TipleaNo ratings yet

- Removal of Calcifications From Distal Canals of Mandibular Molars by A Non-Instrumentational Cleaning System: A micro-CT StudyDocument6 pagesRemoval of Calcifications From Distal Canals of Mandibular Molars by A Non-Instrumentational Cleaning System: A micro-CT StudypoojaNo ratings yet

- Tooth Morphology and Access Cavity PreparationDocument232 pagesTooth Morphology and Access Cavity Preparationusmanhameed8467% (3)

- 2013 ABGDsgDocument244 pages2013 ABGDsgteertheshNo ratings yet

- C-shaped Canal Management with Three Obturation SystemsDocument4 pagesC-shaped Canal Management with Three Obturation SystemsJot KhalsaNo ratings yet

- Access Cavity Preparations: Classi Fication and Literature Review of Traditional and Minimally Invasive Endodontic Access Cavity DesignsDocument16 pagesAccess Cavity Preparations: Classi Fication and Literature Review of Traditional and Minimally Invasive Endodontic Access Cavity DesignsAlexandra Illescas GómezNo ratings yet

- Endodontic MishapsDocument19 pagesEndodontic MishapsSayak GuptaNo ratings yet

- Restoration of Endodontically Treated TeethDocument17 pagesRestoration of Endodontically Treated TeethAfaf MagedNo ratings yet

- Class II malocclusion: The aftermath of a “perfect stormDocument15 pagesClass II malocclusion: The aftermath of a “perfect stormThuyNo ratings yet

- Fixed Functional ApplianceDocument71 pagesFixed Functional AppliancekpNo ratings yet

- Palatal and Facial Veneers To TreatDocument11 pagesPalatal and Facial Veneers To TreatSabrina Antonella Zeballos ClarosNo ratings yet

- Ceramic Laminate Veneers: Clinical Procedures With A Multidisciplinary ApproachDocument24 pagesCeramic Laminate Veneers: Clinical Procedures With A Multidisciplinary ApproachDaniel AtiehNo ratings yet

- The Clincal Management of Ectopically Erupting First Permanent MolarsDocument6 pagesThe Clincal Management of Ectopically Erupting First Permanent MolarsFourthMolar.comNo ratings yet

- Developing Occlusion in Primary and Mixed DentitionDocument45 pagesDeveloping Occlusion in Primary and Mixed Dentitionpriti adsulNo ratings yet

- Brochure Veraviewepocs 3D R100 2019 ENDocument16 pagesBrochure Veraviewepocs 3D R100 2019 ENJosé Daniel Campos MéndezNo ratings yet

- 120 0215 Damon QuickReferenceGuideDocument12 pages120 0215 Damon QuickReferenceGuideAna Kuper0% (1)

- Class Ii Amalgam Cavity Preparation For AmalgamDocument82 pagesClass Ii Amalgam Cavity Preparation For AmalgamVidya Sagar100% (1)

- A Case of Nasopalatine Dust Cyst: Presentation, Diagnosis and ManagementDocument4 pagesA Case of Nasopalatine Dust Cyst: Presentation, Diagnosis and ManagementKertamayaNo ratings yet

- Dietschi 2020 Interceptive Treatment of Tooth Wear - Revised Protocol For The Full Molding TrechniqueDocument24 pagesDietschi 2020 Interceptive Treatment of Tooth Wear - Revised Protocol For The Full Molding TrechniqueCherifNo ratings yet

- Davidovitch1995 PDFDocument6 pagesDavidovitch1995 PDFRahulLife'sNo ratings yet

- Orthodontic Chart: Patient Information RecordDocument8 pagesOrthodontic Chart: Patient Information Recordpunyetanghangsarap Food Delivery ServiceNo ratings yet

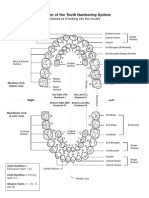

- Diagram of The Tooth Numbering SystemDocument1 pageDiagram of The Tooth Numbering Systemsaleh900No ratings yet

- ANTERIOR TEETH AND SMILE DESIGNDocument40 pagesANTERIOR TEETH AND SMILE DESIGNSahana RangarajanNo ratings yet

- Finite Element Analysis of Porcelain Veneers for Diastema ClosureDocument5 pagesFinite Element Analysis of Porcelain Veneers for Diastema ClosureMirnaLizNo ratings yet

- Brian Willison-2022 Lab Course ProjectsDocument3 pagesBrian Willison-2022 Lab Course ProjectsFabio RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Anterior Teeth Ndbe McqsDocument5 pagesAnterior Teeth Ndbe McqsParneetNo ratings yet

- B. The Overbite Achieved During TreatmentDocument60 pagesB. The Overbite Achieved During TreatmentRC Dome100% (3)

- Occlusal Equilibration: Presented By: Dr. Kelly NortonDocument36 pagesOcclusal Equilibration: Presented By: Dr. Kelly NortonLesley StephenNo ratings yet

- S4 BlankDocument117 pagesS4 BlankEun SaekNo ratings yet

- Esthetic Treatment of Altered Passve EruptionDocument19 pagesEsthetic Treatment of Altered Passve EruptiontaniaNo ratings yet

- Tooth Structure Removal Associated With Various Preparation Designs For Anterior TeethDocument7 pagesTooth Structure Removal Associated With Various Preparation Designs For Anterior TeethAlina AnechiteiNo ratings yet

- EndoPerio 003Document8 pagesEndoPerio 003kapawenkNo ratings yet

- Int Endodontic J - 2016 - Ahmed - A New System For Classifying Root and Root Canal MorphologyDocument10 pagesInt Endodontic J - 2016 - Ahmed - A New System For Classifying Root and Root Canal MorphologyRodrigo Cassana RojasNo ratings yet

- Lip Posture and Its Signi Ficance Treatment Plannin G: Indiamapoli., IndDocument20 pagesLip Posture and Its Signi Ficance Treatment Plannin G: Indiamapoli., IndYeraldin EspañaNo ratings yet

- Flat Plane OcclusionDocument22 pagesFlat Plane OcclusionDavid TaylorNo ratings yet

- 1 ManualDocument10 pages1 Manualwendyjemmy8gmailcomNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Orthodontic BracketsDocument281 pagesEvolution of Orthodontic Bracketssajida khan100% (2)

- The Relevance of Root Canal Isthmuses in Endodontic RehabilitationDocument13 pagesThe Relevance of Root Canal Isthmuses in Endodontic RehabilitationVictorNo ratings yet