Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Calle, Guillermo Maestro de La, Et Al2017

Uploaded by

priya panaleOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Calle, Guillermo Maestro de La, Et Al2017

Uploaded by

priya panaleCopyright:

Available Formats

RESEARCH PAPER

Long-term comparative and prospective

cohort study of renal function in patients

with HIV infection treated with tenofovir

disoproxil fumarate

Guillermo Maestro de la Calle1, Federico Pulido1, Matilde Sánchez-Conde2,

Juan Carlos López Bernaldo de Quirós3

1

Department of HIV Infection, 12 de Octubre University Hospital, Madrid, Spain

2

Internal Medicine Service, Ramón y Cajal University Hospital, Madrid, Spain

3

Department of HIV Infection, Gregorio Marañón University Hospital, Madrid, Spain

Abstract

Introduction: Evidence regarding long-term evolution of renal function in patients with human immu

nodeficiency virus (HIV) infection treated with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) is scarce and often

retrospective.

Material and methods: We carried out an observational prospective cohort study. Patients with

serum creatinine lower than 1.2 mg/dl and an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) higher

than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 were included between January 2001 and December 2005. The primary

outcome was the onset of a clinically relevant decrease in renal function (CRDRF) defined as

an eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73m2 in two consecutive measures or < 50 ml/min/1.73 m2 in any measure.

Secondary objectives were to identify risk factors for the emergence of CRDRF and renal recovery

after TDF discontinuation.

Results: Seventy patients receiving TDF and 58 controls were included. After a median follow-up

of 7.6 years, 10 patients in the TDF group and none in the control group developed CRDRF (p = 0.005).

The incidence rate of CRDRF was 2.2 cases per 100 treated patients per year (CI 95%: 0.85-3.62).

Risk factors for CRDRF onset were higher baseline age (HR = 1.1, CI 95%: 1.05-1.18; p = 0.001), ar-

terial hypertension (HR = 24.8, CI 95%: 3.3-185.6; p = 0.002) and lower baseline eGFR (HR = 0.93,

CI 95%: 0.89-0.97; p = 0.002). After 36 months from TDF discontinuation in CRDRF cases, seven pa-

tients achieved renal recovery (eGFR > 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 in ≥ 2 consecutive measures, with six months

between each measure).

Conclusions: Long-term use of TDF in the treatment of HIV infection is associated with a higher

incidence of a clinically relevant decrease in renal function which may be only partially reversible.

HIV AIDS Rev 2017; 16, 2: 77-83

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5114/hivar.2017.66859

Key words: HIV, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, kidney disease, long-term effects.

Address for correspondence: Dr. Guillermo Maestro de la Calle, Article history:

Department of HIV Infection, 12 de Octubre University Hospital, Received: 23.10.2016

Avenida de Córdoba S/N, 28041 Madrid, Spain, Received in revised form: 15.11.2016

phone: +34620823653, e-mail: gmaestro@gmail.com Accepted: 03.01.2017

Available online: 29.03.2017

HIV & AIDS Review 2017/Volume 16/Number 2

78 Guillermo Maestro de la Calle, Federico Pulido, Matilde Sánchez-Conde, Juan Carlos López Bernaldo de Quirós

Introduction consultations. Patient recruitment was made in one of these

ten consultations. Data collection and patient follow-up was

The risk of both acute kidney injury and chronic renal finished in June 2013, with a median follow-up of 7.6 years

disease is increased in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (IQR 4.1 to 9.0) after baseline visit.

patients compared with the general population [1]. After

the introduction of highly active antiretroviral treatment

Participants

(HAART), arterial hypertension, diabetes, atherosclerosis and

drug toxicity are gaining relevance in the HIV patient as risk Seventy patients initiated TDF as part of their ART, all

factors for the development of kidney disease. of which were offered to collaborate and gave oral consent to

Since tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) approval participate in the study. Fifty-eight controls initiating a non-

in 2000, there is growing evidence of its relationship with TDF containing regimen were recruited and matched with

nephrotoxicity. The drug is mainly excreted in the kidney the TDF group for age, sex, serum creatinine, height and

through its filtration in the glomerulus and active tubular weight. Antiretroviral treatment regimens were composed ac-

secretion. It is postulated that TDF-related kidney damage cording to the Spanish ART guidelines during the recruiting

could be favoured either by means of disruption of the func- period [18]. Inclusion criteria for participating and data anal-

tion of tubular proteins (mainly anion transporter protein 1 ysis were age > 18 years, baseline serum creatinine < 1.2 mg/dl

and drug resistant protein 4) [2, 3] or as a result of mito- and a eGFR > 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (MDRD-4) and at least

chondrial toxicity secondary to intracellular accumulation two follow-up visits with plasma HIV load < 50 copies/ml

of the molecule [4]. Kidney damage with tubular dysfunction (whenever this threshold was achieved). Patients were fol-

has been related with TDF use, even without a decrease in lowed in the ambulatory setting according to an established

the estimated glomerular filtration rate [5]. schedule of visits to the HIV hospital unit.

In a large meta-analysis including clinical trials and co-

hort studies addressed to study renal safety of TDF, only Variables and other data

a slight significant difference was observed in patients treat- measurements

ed with TDF as compared with other ART regimens or pla-

cebo (–3.90 ml/min; CI 95% [–5.66, –2.14]) after a median The main outcome was the CRDRF related with TDF use,

follow-up of 60 weeks [6]. Moreover, large clinical trials with and was defined as the presence of eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2

long follow-up periods of more than 144 weeks in naïve pa- in two consecutive measures with at least 3 months between

tients have shown a renal safety profile of ART containing each measure, or < 50 ml/min/1.73 m2 (MDRD-4) in any

TDF, either similar to other ART without it, or with small measure, when no other attributed cause was evident. The for-

significant declines in the estimated glomerular filtration mer eGFR threshold was used since it is correlated with higher

rate (eGFR) of clinical implications difficult to ascertain [7- morbidity and mortality [19], and the latter because of clini-

9]. Observational studies with longer follow-up periods sug- cal concern about a potential abrupt eGFR decline. Secondary

gest a more deleterious effect on the renal function, and point outcomes were the identification of risk factors for the devel-

that TDF is associated with a higher incidence of chronic opment of CRDRF, the reversibility of CRDRF related to TDF

kidney disease [10-17]. Overall, these results have shown use, and analysis of the diagnostic performance of renal pa-

either a modest or absent decline in renal function associat- rameters as diagnostic tools for early identification of CRDRF.

ed with TDF use after short follow-up periods of months or Renal recovery after TDF discontinuation was defined as

very few years, while studies with longer follow-up periods eGFR > 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 in 2 or more consecutive mea-

suggest a more relevant decrease in renal function [13-17]. sures, with six months between each measure.

The primary objective of this study was to assess the in- For secondary outcomes (e.g. eGFR recovery), the Chron-

cidence of a clinically relevant decrease in renal function ic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation

(CRDRF) in patients treated with TDF as compared with (CKD-EPI) was used to estimate the GFR as these outcomes

controls. Secondary objectives were the evaluation of risk were retrospectively analysed and this equation has more

factors for the development of CRDRF and the reversibility recently become the standard measurement for renal func-

of eGFR decline after cessation of TDF in patients that expe- tion in subjects with eGFR > 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 [20] and has

rienced CRDRF. been validated in the HIV population [21]. Serum creatinine

measure was performed with standardized tests (Creatinine

Jaffé Gen 2, Roche) in every visit, and so height and weight

Material and methods were measured, in order to identify potential confounders

of serum creatinine levels. Calculation of serum creatinine

Study design and setting

and eGFR (CKD-EPI) variation over time was performed

We conducted a prospective cohort study in which pa- subtracting their baseline data from follow-up measures. Fre-

tients were recruited between January 2002 and December quency of data registration was at month 3, 6, 9 12, then every

2005 from Gregorio Marañón Hospital, a tertiary care uni- 6 months until month 72, and then every 12 months.

versity hospital located in Madrid (Spain) in which about Other data such as age, sex, arterial hypertension, diabetes,

2,500 patients with HIV infection are followed in 10 different dyslipidemia, tobacco use, HCV and HBV status (positive serol-

HIV & AIDS Review 2017/Volume 16/Number 2

Long-term renal function in HIV-patients treated with TDF 79

ogy for HCV, and positive HBs-antigen for HBV), date of HIV ard ratios (HR) were subsequently adjusted in a multivar-

diagnosis, way of HIV transmission, plasma nadir HIV load and iate model by stepwise backward regression with variables

CD4+ lymphocytes, previous AIDS-defining events, and ART that proved to be significant in the univariate model. We

components, and potentially nephrotoxic drugs were registered. established a cut-off p-value for Type I error of 0.05 to state

significant differences. Data were analysed with IBM SPSS

statistics software version 20 for Mac Os X.

Statistical analysis Diagnostic performance of renal function parameters to

Quantitative variables were described with mean or me- predict the emergence of CRDRF was studied with ROC curves.

dian with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) or interquartile Creatinine levels at months 3, 12 and 30 were chosen since no

range (IQR). When comparing quantitative variables, Stu- CRDRF events were registered at these time points. In month

dent’s t-test or Mann Whitney U-test were used according 12 and 30, one and two patients, respectively, had already de-

to the normal or non-normal distribution of the variables. veloped CRDRF, and were managed by using their penultimate

Qualitative variables were described by their percentage, and serum creatinine for estimating ROC curves in these months.

compared with Χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test when necessary.

Differences between groups in terms of the survival curves

Results

of CRDRF were analysed with the Kaplan-Meier method,

and log-rank test. Univariate Cox regression was used to Of the 128 patients involved in the study, 70 received

identify risk factors for the development of CRDRF, and haz- TDF as part of their ART regimen (TDF group) and 58 re-

Table 1. Baseline characteristics*

Factor Control group (n = 58) TDF group (n = 70)

Age (years) 40.9 (36.4-47.1) 39.9 (36.7-44.5)

Males 43 (74.1) 56 (80.0)

Hypertension 3 (5.2) 6 (8.6)

Diabetes 9 (15.5) 11 (15.7)

Current smoker 18 (31.0) 31 (44.3)

Dyslipidemia 2 (3.4) 5 (7.1)

Weight (kg) 69.0 (59.0-78.0) 65.0 (58.2-72.0)

BMI (kg/m2) 23.7 (21.3-26.0) 23.0 (21.1-24.7)

HCV infection 18 (31.0) 32 (45.7)

HBV †

2 (3.4) 21 (30.0)

IDU transmission of HIV 21 (36.2) 33 (47.1)

Tinfection HIV (years)† 5.0 (1.7-11.0) 9.8 (4.6-13.2)

Naïve patient† 19 (32.8) 9 (12.9)

Tprevious ART (months)† 31.2 (0.0-71.3) 81.6 (26.6-109.9)

Previous AIDS defining event 14 (24.1) 20 (28.6)

Peripheral blood CD4+ lymphocytes (cells/mL) 345.1M (292.1-398.1) 372.1M (316.9-427.2)

Nadir CD4+ 187.6M (154.7-220.4) 182.1M (148.7-215.6)

CD4+ < 200 cells/ml 13 (22.4) 17 (24.3)

CD4+ < 100 cells/ml 7 (12.1) 4 (5.7)

Plasma HIV viral load (copies/ml) 5.022 (49. 71.719] 1.930 [49. 42.208]

< 50 copies/ml 26 (44.8) 28 (40.0)

≥ 100 000 copies/ml 11 (19.0) 11 (15.7)

Creatinine (mg/dl) 0.9 (0.8-1.0) 0.9 (0.7-1.0)

eGFR with MDRD (ml/min/1.73 m2) 91.1 (81.9-104.9) 92.7 (82.7-106.3)

eGFR with CKD-EPI (ml/min/1.73 m2) 101.7 (93.0-109.9) 106.9 (92.4-111.7)

*Values in square brackets are the 95% confidence interval (or the interquartile range) preceded by the mean (or median). Values in parentheses are the

percentage preceded by the number of patients

M

– mean value (normal distribution), †Significant differences were found with p value < 0.05

BMI – body mass index, HBV – hepatitis B infection, HCV – hepatitis C infection, IDU – intravenous drug user, eGFR – estimated glomerular filtration rate,

Tinfection HIV – time of infection of HIV from diagnosis, TTAR previous – time of TAR in treatment experienced patients

HIV & AIDS Review 2017/Volume 16/Number 2

80 Guillermo Maestro de la Calle, Federico Pulido, Matilde Sánchez-Conde, Juan Carlos López Bernaldo de Quirós

Table 2. Baseline antiretroviral regimens* ceived an ART regimen without it (control group). Every

patient was included in the statistical analysis, even those

Control group (n = 58) TDF group (n = 70)

who were lost in follow-up (5% in the TDF group vs. 10%

NRTI 68 (97.1) 57 (98.3) in the control group, p = 0.32). There were no significant dif-

3TC

†

54 (93.1) 44 (62.9) ferences in most of the baseline demographic data (Table 1),

d4T 6 (10.3) 7 (10.0) but we found significant differences in terms of the presence

AZT

†

11 (19.0) 4 (5.7) of chronic HBV infection (30% TDF group vs. 3.4% control

group, p = 0.0001), time from HIV infection diagnosis (9.8

ABC 11 (19.0) 9 (12.9)

years in the TDF group vs. 5.0 years in the control group,

ddI

†

38 (65.5) 16 (22.9) p = 0.01), number of ART naïve patients (12.9% TDF group

NNRTI† 43 (89.6) 29 (41.4) vs. 32.8% control group, p = 0.007) and time from first ART

EFV

†

19 (32.8) 12 (17.1) in previously treated patients (81.6 years in the TDF group

vs. 31.2 years in the control group, p = 0.0001). In terms

NVP 24 (41.4) 17 (24.3)

of the ART regimens (Table 2), most patients received two nu-

PI †

14 (24.1) 44 (62.8) cleoside analogue reverse-transcriptase inhibitors as the back-

LPV

†

10 (17.2) 35 (50.0) bone of their ART regime. TDF group patients received more

ATV 1 (1.7) 3 (4.3) protease inhibitors than the control group (62.8% vs. 24.1%;

FPV 0 (0) 4 (5.7)

p = 0.001), mainly due to the use of boosted lopinavir (50.0%

TDF group vs. 17.2% control group, p = 0.0001).

NFV 2 (3.4) 1 (1.4)

After a median follow-up of 7.6 years (IQR 4.1 to 9.0),

TPV 0 (0) 1 (1.4) 10 patients in the TDF group developed CRDRF and none

APV 1 (1.7) 0 (0) in the control group (p = 0.005, log rank; Figure 1). There

T20 0 (0) 1 (0.4) were no significant differences in follow-up times (TDF 7.7

*Values in parentheses are the percentage preceded by the number of patients

years (IQR 3.3 to 8.9) versus control 6.1 years (IQR 4.1 to 8.3),

†Significant differences were found with p value < 0.05 p = 0.44. The cumulative incidence of CRDRF in the TDF

NNRTI – non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, NRTI – nucleoside group was 14.3 cases per 100 treated patients, and the inci-

reverse transcriptase inhibitor (two NRTI as part of the treatment regimen),

dence rate was 2.2 cases per 100 treated patients per year (95%

PI – protease inhibitor

CI: 0.85 to 3.62). Loss of follow-up or death took place in

10.9% of the patients (9 and 5 patients, respectively), without

Control group significant differences between groups. There were no signifi-

1.0 cant differences in terms of censored causes between TDF and

control groups in terms of mortality (6.7% vs. 1.7%; p = 0.37),

p = 0.005

loss of follow-up (5.0% vs. 10.3%; p = 0.32), and initiation

0.8 of other nephrotoxic treatments (3.3% vs. 1.7%; p = 1.0).

Survival proportion free of event

Significant differences were identified in patients censored

TDF group because of changes in the ART regimen (stopping TDF for

0.6

other reason in the TDF group in 35.0% vs. initiation of TDF

in the control group in 67.2%, p = 0.001).

0.4 Baseline characteristics were studied as potential risk fac-

tors for the development of CRDRF in the TDF group us-

ing univariate Cox regression model. Higher basal age (HR

0.2 1.1 for each year, 95% CI: 1.05 to 1.18, p = 0.001), the pres-

ence of arterial hypertension (HR 8.3, 95% CI: 2.1 to 33.3,

p = 0.003), lower GFR estimated with CKD-EPI equation

0.0

(HR 0.93 for each ml/min/1.73 m2 CKE-EPI, 95% CI: 0.89

0 2 4 6 8 10 to 0.97, p = 0.002), treatment with atazanavir (HR = 7.6,

Time (years) 95% CI: 1.5-36.9, p = 0.01) and intravenous drug (HR = 0.12,

95% CI: 0.01 to 0.95, p = 0.04) were all identified as signifi-

No. at risk cant. In the multivariate model including all significant vari-

Control 58 53 44 29 17 4

TDF 70 59 47 42 29 5

ables of the univariate model, only age, hypertension and

baseline eGFR preserved statistical significance, and only in

the case of hypertension the HR was modified (HR = 24.8;

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier curves for clinically relevant decrease in

95% CI: 3.3-185.6, p = 0.002).

renal function (CRDRF). Cumulative event rates for the CRDRF The incidence of CRDRF took a bimodal pattern over

in tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and control groups time, with two peaks of incidence. The first one clustered

during the overall study period. Vertical lines show censored CRDRF cases in the first 4 years of follow-up, and the second

patients one that showed up after the 8th year until the end of follow-up

HIV & AIDS Review 2017/Volume 16/Number 2

Long-term renal function in HIV-patients treated with TDF 81

1.0

30

eGFR variation with respect to baseline

Month 30

20 Month 12

values (ml/min/1.73 m2)

0.8

10

0

0.6

Month 3

Sensitivity

–10

–20 0.4

–30

3 6 9 12 18 24 30 36 42 48 54 60 72 84 96 108 120

Months 0.2

Defined by a cutoff value of –12%, yields

No. Patients

a sensibility of 70% and a specificity of 89%

Control 58 58 53 49 43 34 25 19 7

TDF 70 68 62 57 49 47 41 39 13 0.0

0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0

Figure 2. Variation of the estimated glomerular filtration rate Specificity

(eGFR) (CKD-EPI equation) with respect to baseline values Figure 3. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves us-

over time. A dotted line represents the tenofovir disoproxil fu- ing the percent variation of estimated glomerular filtration

marate (TDF) group (patients who developed DRF excluded), rate (eGFR) (CKD-EPI equation) with respect to baseline val-

while a solid line represents the control group. A vertical line ues. Best AUC was found at month 30 (0.85, 95% CI: 0.67-1.0)

represents the 95% confidence intervals around mean values.

* indicates that statistically significant differences were found

with p < 0.05 and ** with p < 0.01 eGFR of 88.9 ml/min/1.73 m2 (IQR: 83.2 to 97.6). Only

a higher time of TDF exposure was a predictor of renal recov-

ery in the univariate and multivariate Cox’s regression model

(Figure 1). This suggested the presence of two types of sce- (HR 1.03 per month of exposure; 95% CI: 1.002-1.05; p = 0.03).

narios for the presentation of CRDRF, an early presentation Finally, we studied the diagnostic performance of the vari-

group and a delayed one. In the early presentation group (first ation of creatinine and the eGFR (as well as their percentage)

43.2 months), patients had a lower basal renal functional re- in months 3, 12 and 30 as early diagnostic tools of CRDRF

serve (baseline eGFR with CKD-EPI equation, 80.6 ± 9.2 vs. onset in patients who received TDF as part of their ART.

92.9 ± 6.3 ml/min/1.73 m2, p = 0.016) and tended to be older When choosing the cut-off value, a higher specificity value

(54.5 ± 21.2 vs. 44.1 ± 10 years, p = 0.27), and with a high- prevailed over higher sensitivity values. We found the per-

er prevalence of arterial hypertension (40% vs. 20%, p = 1.0), centage of eGFR variation in month 30 to have the best di-

than in the delayed presentation group. agnostic performance, with an area under the curve of 0.85

The evolution of the eGFR over time was significantly (95% CI: 0.67-1.0), with a cut-off point in –12% that offers

different between groups after the patients who experienced a sensibility of 70% and a specificity of 89% (Figure 3).

the CRDRF were excluded from the comparison (Figure 2).

In month 48, patients in the TDF group (patients who had Discussion

experienced the CRDRF excluded) experienced a progressive

decline in their eGFR as compared with the control group In this cohort study the use of TDF in the treatment

(median variation 0.00 IQR –10.86 to 0.00 in the TDF group of HIV infection was related with a higher incidence

versus +4.92 IQR –5.08 to +12.23 ml/min/1.73 m2 in the con- of CRDRF. An older age, arterial hypertension and lower

trol group; p = 0.007). Thereafter, we found significant dif- baseline eGFR were significant risk factors for the devel-

ferences in eGFR variations between groups in almost every opment of this event. Even when patients who developed

month and these differences became greater over time. As an CRDRF were excluded from the analysis, TDF group pa-

example, in month 84, the median eGFR variation was 0.00 tients experienced significant decreases in their eGFR com-

ml/min/1.73 m2 (IQR –7.58 to +5.46) in the TDF group versus pared with the control group in almost every month after

+11.51 (IQR +5.01 to +17.53) in the control group (p = 0.001). 4 years of treatment. Following TDF discontinuation, most

After TDF discontinuation because of CRDRF, we of the patients achieved an eGFR higher than 60 ml/min/

studied the reversibility of renal function. After 36 months 1.73 m2 (CKE-EPI).

of follow-up, seven of these patients achieved a renal recov- Overall both groups had similar baseline characteristics.

ery. The median time to renal recovery was 18 months. None However, an important limitation of the study is a prescrip-

of the patients returned to his baseline eGFR, and after the end tion bias by which patients that received TDF had more co-

of follow-up the median eGFR was 68.3 ml/min/1.73 m2 morbidities. This phenomenon can be explained by the guide-

(IQR: 60.4 to 79.2), compared with their median baseline line recommendations during the recruitment period, which

HIV & AIDS Review 2017/Volume 16/Number 2

82 Guillermo Maestro de la Calle, Federico Pulido, Matilde Sánchez-Conde, Juan Carlos López Bernaldo de Quirós

recommended TDF in the setting of rescue therapy instead the multivariate model. Other more specific factors related

of a component of ART for treating naïve patients, which in other studies with TDF nephrotoxicity, such as concomi-

has been recommended in more recent guidelines [18]. In tant use of protease inhibitors, were not found to be signifi-

this sense, the TDF group had a significantly higher time cant risk factors but sample size limits our ability to draw any

from HIV infection diagnosis, fewer ART naïve patients conclusions in this regard.

and longer times from first ART, which makes a more frag- When TDF was discontinued because of CRDRF de-

ile population more susceptible to renal disease. Moreover, velopment most patients achieved a sustained eGFR over

this bias could explain another significant limitation of our 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (CKD-EPI) after 3 years’ follow-up, but

work, which is the higher prevalence of boosted protease none of them achieved their baseline eGFR. Previously pub-

inhibitor (PI) as part of the ART regimen in TDF group pa- lished works in regard to renal recovery after TDF discon-

tients. Boosted PIs have been related to a higher incidence tinuation are often retrospective, heterogeneous, and have

of kidney disease in many observational studies [10, 22], studied this phenomenon when TDF was stopped because

although data from clinical trials suggest a reasonable renal the development of kidney damage [25, 26] or irrespec-

safety profile [23]. In our study, the use of PIs did not show tively of the cause of TDF cessation [27]. In these studies

any significant relationship with CRDRF so its role as a poten- most patients experience an improvement in their eGFR

tial confounder in our study might be limited. (61.4-68.9%) and recovery of baseline (or predicted) eGFR

A remarkable strength of this study is the long follow-up was common (42-61.4%). On the other hand, shorter median

period in comparison with clinical trials and other prospec- time of 4 months to achieve eGFR over 60 ml/min/1.73 m2

tive cohort studies published to date [6, 7, 10, 24]. Of inter- has been described [26], as compared with 13 months [25]

est, the median time to CRDRF event was 3.6 years, which is or 18 months in our study. These differences with our find-

much longer than most follow-up periods in other studies. ings might be due to the interruption of TDF when other

This may have made it possible for our study to detect this variables were taken into account (e.g. proteinuria, hypo-

progressive event despite a limited sample size by identifying phosphatemia) or with different criteria because of the ret-

late events. It is remarkable that a bimodal history of pro- rospective characteristics of these studies.

gression to CRDRF was observed with kidney injury events Recent IDSA guidelines have been the first to strongly

being clustered in the first four years and after the eighth recommend the use of the percentage of eGFR decline from

year of TDF treatment. This is a novel finding and it suggests baseline (> 25%) with eGFR (< 60 ml/min/1.73 m2) to sub-

that patients with more baseline risk factors for kidney inju- stitute alternative drugs for TDF, although with a low level

ry emergence (e.g., age, hypertension, lower baseline eGFR) of evidence [28]. In our study, the best diagnostic perfor-

may progress to CRDRF in the first years of treatment, while mance of CRDRF using eGFR or creatinine was obtained

in the healthier counterparts kidney injury may only be- with the percentage of variation of eGFR from baseline

come apparent after several years of TDF exposure. (CKD-EPI) at month 30. While we set a lower value of –12%

While most previously published works with shorter fol- as the optimal cut-off point, this value has to be taken into ac-

low-up periods have found little variation of the eGFR relat- count as regards an intention to anticipate the CRDRF event.

ed to TDF use [6], some observational studies with longer Phase II and III trials comparing the new formulation

follow-up periods have found CRDRF related with TDF use tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (TAF) with TDF have found

[13-17]. It is worth mentioning some considerations about significantly higher declines in the eGFR in the TDF group af-

these studies. Some of them have been conducted in specif- ter short drug exposure periods (median < 70 weeks) [29-31].

ic populations such as African population [16], among pa- Further data will be needed about the renal safety profile

tients with low body weight [15], or treatment-naïve patients of TAF in the long term.

[17], and others have used the Cockcroft-Gault equation to

estimate the creatinine clearance [13], which can result in

Conclusions

an overestimate of the creatinine clearance. These situa-

tions might explain why our study shows a higher incidence Our findings suggest that long-term use of TDF is as-

of chronic kidney disease related to TDF use in the long sociated with a bimodal onset (early and late) of a clinically

term. Due to our scarce sample size, subtle but significant relevant decrease in renal function, which is only partially

eGFR variations were only observed after four years of treat- reversible in the majority of patients. A progressive decline

ment (patients with CRDRF excluded from the analysis), in the eGFR irrespective of the onset of CRDRF was ob-

and were similar in their magnitude with previously pub- served. Patients at higher risk to develop CRDRF are those

lished observational works [6, 10]. who are older, with arterial hypertension and with lower

Risk factors for TDF related kidney damage are not baseline eGFR.

clearly established. Observational studies suggest that older

age and lower baseline eGFR are risk factors, all of which are

well-known risk factors for progression to chronic kidney

Conflict of interest

disease in the general population, with arterial hypertension The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest

not being so clearly related [10, 12, 14]. We only found these with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication

three risk factors as significant predictors of CRDRF onset in of this article.

HIV & AIDS Review 2017/Volume 16/Number 2

Long-term renal function in HIV-patients treated with TDF 83

References kidney outcomes. A collaborative meta-analysis of general and

high-risk population cohorts. Kidney Int 2011; 80: 93-104.

1. Wyatt CM, Winston JA, Malvestutto CD, et al. Chronic kidney dis- 20. Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Greene T, et al. Comparative performance

ease in HIV infection: an urban epidemic. AIDS 2007; 21: 2101-2103. of the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) and the Mod-

2. Miller DS. Nucleoside phosphonate interactions with multiple or- ification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study equations for es-

ganic anion transporters in renal proximal tubule. J Pharmacol Exp timating GFR levels above 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Am J Kidney Dis

Ther 2001; 299: 567-574. 2010; 56: 486-495.

3. Weiss J, Theile D, Ketabi-Kiyanvash N, et al. Inhibition of MRP1/ 21. Gagneux-Brunon A, Delanaye P, Maillard N, et al. Performance

ABCC1, MRP2/ABCC2, and MRP3/ABCC3 by nucleoside, nucle- of creatinine and cystatin C-based glomerular filtration rate esti-

otide, and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Drug mating equations in a European HIV-positive cohort. AIDS 2013;

Metab Dispos 2007; 35: 340-344. 27: 1573-1581.

4. Cote HC, Magil AB, Harris M, et al. Exploring mitochondrial neph- 22. Zimmermann AE, Pizzoferrato T, Bedford J, et al. Tenofovir-asso-

rotoxicity as a potential mechanism of kidney dysfunction among ciated acute and chronic kidney disease: a case of multiple drug

HIV-infected patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Antivir interactions. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42: 283-290.

Ther 2006; 11: 79-86. 23. Pulido F, Fiorante S. Clinical data II. Clinical experience of teno-

5. Labarga P, Barreiro P, Martin-Carbonero L, et al. Kidney tubular fovir DF in combination with protease inhibitors. Enferm Infecc

abnormalities in the absence of impaired glomerular function in Microbiol Clin 2008; 26 Suppl 8: 13-18.

HIV patients treated with tenofovir. AIDS 2009; 23: 689-696. 24. Walmsley SL, Antela A, Clumeck N, et al. Dolutegravir plus abaca-

6. Cooper RD, Wiebe N, Smith N, et al. Systematic review and meta- vir-lamivudine for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med

analysis: renal safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in HIV-infect- 2013; 369: 1807-1818.

ed patients. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 51: 496-505. 25. Wever K, van Agtmael MA, Carr A. Incomplete reversibility

7. Campbell TB, Smeaton LM, Kumarasamy N, et al. Efficacy and safety of tenofovir-related renal toxicity in HIV-infected men. J Acquir

of three antiretroviral regimens for initial treatment of HIV-1: a ran- Immune Defic Syndr 2010; 55: 78-81.

domized clinical trial in diverse multinational settings. PLoS Med 26. Bonjoch A, Echeverria P, Perez-Alvarez N, et al. High rate of re-

2012; 9: e1001290. versibility of renal damage in a cohort of HIV-infected patients

8. Arribas JR, Pozniak AL, Gallant JE, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fu- receiving tenofovir-containing antiretroviral therapy. Antiviral Res

marate, emtricitabine, and efavirenz compared with zidovudine/ 2012; 96: 65-69.

lamivudine and efavirenz in treatment-naive patients: 144-week 27. Jose S, Hamzah L, Campbell LJ, et al. Incomplete reversibility of es-

analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008; 47: 74-78. timated glomerular filtration rate decline following tenofovir diso-

9. Gallant JE, Staszewski S, Pozniak AL, et al. Efficacy and safety of teno- proxil fumarate exposure. J Infect Dis 2014; 210: 363-373.

fovir DF vs stavudine in combination therapy in antiretroviral-naive 28. Lucas GM, Ross MJ, Stock PG, et al. Clinical practice guideline for

patients: a 3-year randomized trial. JAMA 2004; 292: 191-201. the management of chronic kidney disease in patients infected with

10. Ryom L, Mocroft A, Kirk O, et al. Association between antiretro- HIV: 2014 update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infec-

viral exposure and renal impairment among HIV-positive persons tious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59: e96-

with normal baseline renal function: the D:A:D study. J Infect Dis 138.

2013; 207: 1359-1369. 29. Sax PE, Wohl D, Yin MT, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide versus teno-

11. Monteagudo-Chu MO, Chang MH, Fung HB, et al. Renal toxic- fovir disoproxil fumarate, coformulated with elvitegravir, cobici-

ity of long-term therapy with tenofovir in HIV-infected patients. stat, and emtricitabine, for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: two

J Pharm Pract 2012; 25: 552-559. randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trials. Lancet

12. Madeddu G, Bonfanti P, De Socio GV, et al. Tenofovir renal safe- 2015; 385: 2606-2615.

ty in HIV-infected patients: results from the SCOLTA Project. 30. Mills A, Crofoot G Jr, McDonald C, et al. Tenofovir Alafenamide

Biomed Pharmacother 2008; 62: 6-11. vs. Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate in the First Protease Inhibi-

13. Mocroft A, Lundgren JD, Ross M, et al. Cumulative and current tor-based Single Tablet Regimen for Initial HIV-1 Therapy: A Ran-

exposure to potentially nephrotoxic antiretrovirals and develop- domized Phase 2 Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 69:

ment of chronic kidney disease in HIV-positive individuals with 439-445.

a normal baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate: a prospec- 31. Sax PE, Zolopa A, Brar I, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide vs. tenofo-

tive international cohort study. Lancet HIV 2016; 3: e23-32. vir disoproxil fumarate in single tablet regimens for initial HIV-1

14. Zhao Y, Zhang M, Shi CX, et al. Renal Function in Chinese therapy: a randomized phase 2 study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr

HIV-Positive Individuals following Initiation of Antiretroviral 2014; 67: 52-58.

Therapy. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0135462.

15. Nishijima T, Kawasaki Y, Tanaka N, et al. Long-term exposure to

tenofovir continuously decrease renal function in HIV-1-infected

patients with low body weight: results from 10 years of follow-up.

AIDS 2014; 28: 1903-1910.

16. Mulenga L, Musonda P, Mwango A, et al. Effect of baseline renal

function on tenofovir-containing antiretroviral therapy outcomes

in Zambia. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58: 1473-1480.

17. Scherzer R, Estrella M, Li Y, et al. Association of tenofovir exposure

with kidney disease risk in HIV infection. AIDS 2012; 26: 867-875.

18. Rubio R, Berenguer J, Miro JM, et al. Recommendations

of the Spanish AIDS Study Group (GESIDA) and the National

Aids Plan (PNS) for antiretroviral treatment in adult patients with

human immunodeficiency virus infection in 2002. Enferm Infecc

Microbiol Clin 2002; 20: 244-303.

19. Gansevoort RT, Matsushita K, van der Velde M, et al. Lower es-

timated GFR and higher albuminuria are associated with adverse

HIV & AIDS Review 2017/Volume 16/Number 2

You might also like

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 8: UrologyFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 8: UrologyRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Decision Analytics and Optimization in Disease Prevention and TreatmentFrom EverandDecision Analytics and Optimization in Disease Prevention and TreatmentNan KongNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument10 pagesResearch ArticleAmeldaNo ratings yet

- Gfac 227Document8 pagesGfac 227Cristina Adriana PopaNo ratings yet

- 1.CKD and Its Health Related Factor A Case Control StudyDocument7 pages1.CKD and Its Health Related Factor A Case Control StudyBobby PrayogoNo ratings yet

- Cyclophosphamide Versus Mycophenolate Versus Rituximab in Lupus Nephritis Remission InductionDocument8 pagesCyclophosphamide Versus Mycophenolate Versus Rituximab in Lupus Nephritis Remission InductionVh TRNo ratings yet

- Contoh Jurnal Meta AnalisisDocument17 pagesContoh Jurnal Meta AnalisisMia Audina Miyanoshita100% (1)

- Egfr Text OnlyDocument12 pagesEgfr Text OnlyGreenThumbNo ratings yet

- Apc 2016 0286Document8 pagesApc 2016 0286Friska RamadayantiNo ratings yet

- 25rakshitha EtalDocument8 pages25rakshitha EtaleditorijmrhsNo ratings yet

- Nej Mo A 2024816Document20 pagesNej Mo A 2024816Ahmad Mutta'inNo ratings yet

- Kaewput 2020Document11 pagesKaewput 2020MarcelliaNo ratings yet

- Dapa-Ckd 2020 NejmDocument11 pagesDapa-Ckd 2020 NejmInês MendonçaNo ratings yet

- 2011 - Denicola (Jurnal)Document9 pages2011 - Denicola (Jurnal)Riana HandayaniNo ratings yet

- Analisa Drug Related Problem (DRPS) Pada Pasien Gagal Ginjal Kronik Stadium Akhir Yang Menjalani Hemodialisa Di Rsud 45 KuninganDocument14 pagesAnalisa Drug Related Problem (DRPS) Pada Pasien Gagal Ginjal Kronik Stadium Akhir Yang Menjalani Hemodialisa Di Rsud 45 KuninganlintangNo ratings yet

- Traa 144Document9 pagesTraa 144RashifNo ratings yet

- SurvivalDocument7 pagesSurvivalFuad HadiNo ratings yet

- Nejmoa 2024816Document11 pagesNejmoa 2024816Cessar OrnlsNo ratings yet

- 2023, 13 Sept-Dr. I Gede Yasa - Effect of Residual Kidney Function and Dialysis Adequacy On Chronic Pruritus in Dialysis PatientsDocument11 pages2023, 13 Sept-Dr. I Gede Yasa - Effect of Residual Kidney Function and Dialysis Adequacy On Chronic Pruritus in Dialysis PatientsYuyun RasulongNo ratings yet

- Dapa CKDDocument11 pagesDapa CKDCarlos Andres Tejeda PerezNo ratings yet

- Kocyigit 2012Document8 pagesKocyigit 2012Rengganis PutriNo ratings yet

- Junral FarmakoepidDocument13 pagesJunral FarmakoepidAsyaNo ratings yet

- JDR2019 7825804Document9 pagesJDR2019 7825804Anonymous Xc7NwZzoNo ratings yet

- Lec - S32 Injuria RenalDocument8 pagesLec - S32 Injuria RenalEvelyn EstradaNo ratings yet

- Global Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease - A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument19 pagesGlobal Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease - A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisAngel ViolaNo ratings yet

- Combination Therapy of Rituximab and Mycophenolate Mofetil in Childhood Lupus NephritisDocument6 pagesCombination Therapy of Rituximab and Mycophenolate Mofetil in Childhood Lupus NephritisrifkyramadhanNo ratings yet

- Vesconi 2009Document14 pagesVesconi 2009Nguyễn Đức LongNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Fibrinogen: A Marker in Predicting Diabetic Foot Ulcer SeverityDocument6 pagesResearch Article: Fibrinogen: A Marker in Predicting Diabetic Foot Ulcer SeverityAlbarr YusufNo ratings yet

- Erc e HtaDocument10 pagesErc e HtamiguelalmenarezNo ratings yet

- Research Study JournalDocument27 pagesResearch Study JournalHyacinth A RotaNo ratings yet

- COHORT - TB MenigealDocument11 pagesCOHORT - TB MenigealYA MAAPNo ratings yet

- Tenofovir Associated Renal Toxicity in A Cohort of Hiv Infected Individuals in Goa - January - 2020 - 1577784624 - 0401138Document3 pagesTenofovir Associated Renal Toxicity in A Cohort of Hiv Infected Individuals in Goa - January - 2020 - 1577784624 - 0401138rfrdefNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease CKD in Type 2 Diabetes Mellituspatients Startindia Study 2155 6156 1000722Document5 pagesPrevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease CKD in Type 2 Diabetes Mellituspatients Startindia Study 2155 6156 1000722Manish SharmaNo ratings yet

- 【DAPA-CKD FSGS】Safety and efficacy of dapagliflozin in patients with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis a prespecified analysis of the DAPA-CKDDocument10 pages【DAPA-CKD FSGS】Safety and efficacy of dapagliflozin in patients with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis a prespecified analysis of the DAPA-CKD陈诗哲No ratings yet

- Impact of Hypertension On Type 2 Diabetes in Mysore Population of South IndiaDocument10 pagesImpact of Hypertension On Type 2 Diabetes in Mysore Population of South Indiagaluh putriNo ratings yet

- Gfad 118Document10 pagesGfad 118pepegiovannyNo ratings yet

- Real World Experiences Pirfenidone and Nintedanib Are Effective and Well Tolerated Treatments For Idiopathic Pulmonary FibrosisDocument12 pagesReal World Experiences Pirfenidone and Nintedanib Are Effective and Well Tolerated Treatments For Idiopathic Pulmonary FibrosismaleticjNo ratings yet

- Global Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease - A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument18 pagesGlobal Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease - A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisMellya RizkiNo ratings yet

- A Prospective Observational Study of Dengue Fever With Thrombocytopenia With Reference To TreatmentDocument6 pagesA Prospective Observational Study of Dengue Fever With Thrombocytopenia With Reference To Treatment-Tony Santoso Putra-No ratings yet

- Renal IdntDocument7 pagesRenal IdntdonsuniNo ratings yet

- Self-Management Interventions For Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument13 pagesSelf-Management Interventions For Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisKikimariaNo ratings yet

- Serum Uric Acid and Chronic Kidney Disease The Role of HypertensionDocument8 pagesSerum Uric Acid and Chronic Kidney Disease The Role of HypertensionAdam Adachi SanNo ratings yet

- Adalimumab Added To A Treat-To-target With MTX and I-Art Triamcinolone in Early RADocument10 pagesAdalimumab Added To A Treat-To-target With MTX and I-Art Triamcinolone in Early RAElenaChiriacovaNo ratings yet

- Baca IniDocument9 pagesBaca IniRahmi Annisa MaharaniNo ratings yet

- 1677 5538 Ibju 42 04 0694Document10 pages1677 5538 Ibju 42 04 0694Lucas VibiamNo ratings yet

- IJCRT2108180Document6 pagesIJCRT2108180Anchana KsNo ratings yet

- Ebp 1748-5908-8-88Document9 pagesEbp 1748-5908-8-88Maria ImakulataNo ratings yet

- Nefrectomia OFF Clamp Vs ON ClampDocument7 pagesNefrectomia OFF Clamp Vs ON Clampfelipe laraNo ratings yet

- A Prospective Cohort Study of Rituximab in The Treatment of Refractory Nephrotic SyndromeDocument10 pagesA Prospective Cohort Study of Rituximab in The Treatment of Refractory Nephrotic SyndromeMuh Deriyatmiko BastamanNo ratings yet

- Rapid Drug Susceptibility Testing and Treatment Outcomes For Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis in PeruDocument9 pagesRapid Drug Susceptibility Testing and Treatment Outcomes For Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis in Perucarlos castañon reyesNo ratings yet

- Use of Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter 2 Inhibitors and Risk of Serious Renal Events - Scandinavian Cohort Study - The BMJDocument11 pagesUse of Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter 2 Inhibitors and Risk of Serious Renal Events - Scandinavian Cohort Study - The BMJLauren ReckNo ratings yet

- Research Article: TNF-Alpha Levels in Tears: A Novel Biomarker To Assess The Degree of Diabetic RetinopathyDocument7 pagesResearch Article: TNF-Alpha Levels in Tears: A Novel Biomarker To Assess The Degree of Diabetic RetinopathytiaraleshaNo ratings yet

- 521 25 974 2 10 20180513Document7 pages521 25 974 2 10 20180513Lailatuz ZakiyahNo ratings yet

- 521 25 974 2 10 20180513Document7 pages521 25 974 2 10 20180513Lailatuz ZakiyahNo ratings yet

- 521 25 974 2 10 20180513Document7 pages521 25 974 2 10 20180513Lailatuz ZakiyahNo ratings yet

- 2 AnemiaDocument13 pages2 AnemiasalwaNo ratings yet

- Pone 0100831Document9 pagesPone 0100831ChensoNo ratings yet

- Management of Patients Suspected of Having Dengue FeverDocument6 pagesManagement of Patients Suspected of Having Dengue FeverRam Kripal MishraNo ratings yet

- The Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Chronic Kidney Disease (DAPA-CKD) Trial: Baseline CharacteristicsDocument12 pagesThe Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Chronic Kidney Disease (DAPA-CKD) Trial: Baseline CharacteristicsSorina ElenaNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Transoral IncisionDocument14 pagesEfficacy of Transoral IncisionResidentes CirugiaNo ratings yet

- Venter, Willem D. F., Et Al.2018Document8 pagesVenter, Willem D. F., Et Al.2018priya panaleNo ratings yet

- Debeb, Simachew Gidey, Et Al. 2021Document13 pagesDebeb, Simachew Gidey, Et Al. 2021priya panaleNo ratings yet

- Yilma2020ilma, Daniel, Et Al.2020Document11 pagesYilma2020ilma, Daniel, Et Al.2020priya panaleNo ratings yet

- Elias, Adikwu, Et Al. 2014Document15 pagesElias, Adikwu, Et Al. 2014priya panaleNo ratings yet

- Cheli, Stefania, Et Al.2021Document8 pagesCheli, Stefania, Et Al.2021priya panaleNo ratings yet

- Agbaji, Oche O., Et Al. 2019Document9 pagesAgbaji, Oche O., Et Al. 2019priya panaleNo ratings yet

- Ramamoorthy 2014Document10 pagesRamamoorthy 2014priya panaleNo ratings yet

- Abraham 2013Document15 pagesAbraham 2013priya panaleNo ratings yet

- Megan Firlotte 2020Document2 pagesMegan Firlotte 2020api-544351197No ratings yet

- Revived Bcis2 TrialDocument10 pagesRevived Bcis2 TrialSundaresan SankarNo ratings yet

- Journal Club PDADocument30 pagesJournal Club PDASnehal PatilNo ratings yet

- A Migraine Headache PresentationDocument14 pagesA Migraine Headache PresentationAbdullah Masud TanjimNo ratings yet

- Mechanical Ventilation - ModesDocument40 pagesMechanical Ventilation - ModesabdallahNo ratings yet

- ABC of Intensive CareDocument49 pagesABC of Intensive CareCurro MirallesNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis Chinese MedicineDocument215 pagesDiagnosis Chinese Medicinealejandro jeanNo ratings yet

- Oxford Handbook of Anaesthesia (Rachel Freedman, Lara Herbert Etc.)Document1,273 pagesOxford Handbook of Anaesthesia (Rachel Freedman, Lara Herbert Etc.)Liana Naamneh100% (2)

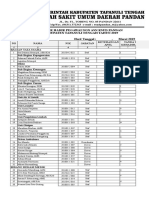

- Stok Opnmae FixDocument6 pagesStok Opnmae FixRossa patria NandaNo ratings yet

- Trikafta Combination Therapy For Cystic FibrosisDocument6 pagesTrikafta Combination Therapy For Cystic Fibrosissamarah arjumandNo ratings yet

- Name: Maulana Aditya Pratama Number: 18029Document8 pagesName: Maulana Aditya Pratama Number: 18029Widiya BudiNo ratings yet

- Reading The Brain by Caroline MarkolinDocument2 pagesReading The Brain by Caroline MarkolinCoraKiri100% (1)

- Gerson - The Little Enema BookDocument36 pagesGerson - The Little Enema BookBruno GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- Case Study 1Document4 pagesCase Study 1api-271668042No ratings yet

- 37 - Acute Rheumatic FeverDocument1 page37 - Acute Rheumatic FevernasibdinNo ratings yet

- Kim Resume PDFDocument1 pageKim Resume PDFapi-548816548No ratings yet

- The Kaohsiung J of Med Scie - 2013 - Tsai - Pyoderma Gangrenosum Intractable Leg Ulcers in Sjogren S SyndromeDocument2 pagesThe Kaohsiung J of Med Scie - 2013 - Tsai - Pyoderma Gangrenosum Intractable Leg Ulcers in Sjogren S SyndromeAsad KakarNo ratings yet

- Referensi Referat ObgynDocument10 pagesReferensi Referat ObgynFaradiba NoviandiniNo ratings yet

- The Relevance of Attachment Theory For PDocument52 pagesThe Relevance of Attachment Theory For PVeera Balaji KumarNo ratings yet

- Typhoid PerforationDocument3 pagesTyphoid PerforationSaryia JavedNo ratings yet

- Crocus Sativus L. (Saffron) in The Treatment of Premenstrual Syndrome: A Double-Blind, Randomised and Placebo-Controlled TrialDocument5 pagesCrocus Sativus L. (Saffron) in The Treatment of Premenstrual Syndrome: A Double-Blind, Randomised and Placebo-Controlled TrialhanaNo ratings yet

- Most Common Chronic Pain ConditionsDocument7 pagesMost Common Chronic Pain ConditionsNicolas RitoNo ratings yet

- Community Health Nursing I (Individual and Family) : Prepared By: Mrs. Lavinia T. Malabuyoc, MAN, R.NDocument48 pagesCommunity Health Nursing I (Individual and Family) : Prepared By: Mrs. Lavinia T. Malabuyoc, MAN, R.NLerma Pagcaliwangan100% (1)

- Organ DonationDocument44 pagesOrgan DonationKlause Kenze Kabil50% (2)

- M-i-M For DME Matrix-In-A-Matrix Technique For Deep Margin ElevationDocument5 pagesM-i-M For DME Matrix-In-A-Matrix Technique For Deep Margin Elevationfernando vicente100% (1)

- Traumatic Ulcerative Granuloma With Stromal Eosinophilia: Case ReportDocument4 pagesTraumatic Ulcerative Granuloma With Stromal Eosinophilia: Case ReportFandy MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Deterministic Malaria Transmission Model With Acquired ImmunityDocument6 pagesDeterministic Malaria Transmission Model With Acquired ImmunityAchmad Nur AlphiantoNo ratings yet

- Absen Edit 2019Document29 pagesAbsen Edit 2019Judika ThampNo ratings yet

- Slle Examination Content Guideline - March 05 PDFDocument16 pagesSlle Examination Content Guideline - March 05 PDFYahya Alkamali100% (1)

- Adam Nursing 111 Evaluation ToolDocument6 pagesAdam Nursing 111 Evaluation Toolapi-281282134No ratings yet