Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Case Digest of BAYAN MUNA vs. ALBERTO ROMULO

Uploaded by

KukuruuOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Case Digest of BAYAN MUNA vs. ALBERTO ROMULO

Uploaded by

KukuruuCopyright:

Available Formats

BAYAN MUNA vs.

ALBERTO ROMULO

FACTS

This petition for certiorari, mandamus and prohibition under Rule 65 assails and seeks

to nullify the Non-Surrender Agreement concluded by and between the Republic of the

Philippines (RP) and the United States of America (USA).

Petitioner Bayan Muna is a duly registered party-list group established to represent the

marginalized sectors of society. Respondent Blas F. Ople, now deceased, was the Secretary of

Foreign Affairs during the period material to this case. Respondent Alberto Romulo was

impleaded in his capacity as then Executive Secretary. Via Exchange of Notes No. BFO-028-

03dated May 13, 2003 (E/N BFO-028-03, hereinafter), the RP, represented by then DFA

Secretary Ople, agreed with and accepted the US proposals embodied under the US Embassy

Note adverted to and put in effect the Agreement with the US government.|||

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, the power to exercise its jurisdiction over

persons for the most serious crimes of international concern x x x and shall be complementary

to the national criminal jurisdictions. In 2000, the RP, through Charge d’Affaires Enrique A.

Manalo, signed the Rome Statute which, by its terms, is “subject to ratification, acceptance or

approval” by the signatory states.

RP-US Non-Surrender Agreement, aims to protect what it refers to and defines as "persons"

of the RP and US from frivolous and harassment suits that might be brought against them in

international tribunals.

The Agreement pertinently provides as follows:

1. For purposes of this Agreement, "persons" are current or former Government

officials, employees (including contractors), or military personnel or nationals of

one Party.

2. Persons of one-Party present in the territory of the other shall not, absent the

express consent of the first Party, DIESHT

a. be surrendered or transferred by any means to any international tribunal

for any purpose, unless such tribunal has been established by the UN

Security Council, or

b. be surrendered or transferred by any means to any other entity or third

country, or expelled to a third country, for the purpose of surrender to or

transfer to any international tribunal, unless such tribunal has been

established by the UN Security Council.

3. When the [US] extradites, surrenders, or otherwise transfers a person of the

Philippines to a third country, the [US] will not agree to the surrender or transfer

of that person by the third country to any international tribunal, unless such

tribunal has been established by the UN Security Council, absent the express

consent of the Government of the Republic of the Philippines [GRP].

4. When the [GRP] extradites, surrenders, or otherwise transfers a person of the

[USA] to a third country, the [GRP] will not agree to the surrender or transfer of

that person by the third country to any international tribunal, unless such tribunal

has been established by the UN Security C ouncil, absent the express consent

of the Government of the [US].

5. This Agreement shall remain in force until one year after the date on which one

party notifies the other of its intent to terminate the Agreement. The provisions

of this Agreement shall continue to apply with respect to any act occurring, or

any allegation arising, before the effective date of termination

ISSUE

1. Whether the exchange of notes, valid, binding and effective without the concurrence by

at least two-thirds (2/3) of all the members of the senate

2. WON the signing of RP in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court pending

ratification will be in conflict with the RP-US Non-Surrender Agreement;

RULING

Under international law, there is no difference between treaties and executive

agreements in terms of their binding effects on the contracting states concerned, as

long as the negotiating functionaries have remained within their powers. Neither, on the

domestic sphere, can one be held valid if it violates the Constitution.

One of these is the doctrine of incorporation, as expressed in Section 2, Article II of the

Constitution, wherein the Philippines adopts the generally accepted principles of international

law and international jurisprudence as part of the law of the land and adheres to the policy of

peace, cooperation, and amity with all nations. An exchange of notes falls "into the category

of inter-governmental agreements," which is an internationally accepted form of international

agreement. The United Nations Treaty Collections (Treaty Reference Guide) defines the term

as follows:

An "exchange of notes" is a record of a routine agreement, that has many

similarities with the private law contract. The agreement consists of the exchange of two

documents, each of the parties being in the possession of the one signed by the representative

of the other. Under the usual procedure, the accepting State repeats the text of the offering

State to record its assent. The signatories of the letters may be government Ministers,

diplomats or departmental heads. The technique of exchange of notes is frequently resorted

to, either because of its speedy procedure, or, sometimes, to avoid the process of legislative

approval.

It is fairly clear from the foregoing disquisition that E/N BFO-028-03––be it viewed as the

Non-Surrender Agreement itself, or as an integral instrument of acceptance thereof or as

consent to be bound––is a recognized mode of concluding a legally binding international

written contract among nations.

Senate Concurrence Not Required

Article 2 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties defines a treaty as “an

international agreement concluded between states in written form and governed by international

law, whether embodied in a single instrument or in two or more related instruments and whatever

its particular designation.”32 International agreements may be in the form of treaties that require

legislative concurrence after executive ratification; or executive agreements that are similar to

treaties, except that they do not require legislative concurrence and are usually less formal and

deal with a narrower range of subject matters than treaties.33

Under international law, there is no difference between treaties and executive agreements in

terms of their binding effects on the contracting states concerned,34 as long as the negotiating

functionaries have remained within their powers.35 Neither, on the domestic sphere, can one be

held valid if it violates the Constitution.36 Authorities are, however, agreed that one is distinct

from another for accepted reasons apart from the concurrence-requirement aspect.37 As has

been observed by US constitutional scholars, a treaty has greater “dignity” than an executive

agreement, because its constitutional efficacy is beyond doubt, a treaty having behind it the

authority of the President, the Senate, and the people

LEGAL BASIS:

RA No. 6426 guarantees a clear right to the depositors and demands an exacting

obligation from banks to maintain the absolute confidentiality of the foreign currency deposits.

The failure of a bank to fulfill its obligation under the law subjects the bank and its officials to

criminal liability under Section 10 of RA No. 6426, and its authority to accept new foreign

currency deposits may be revoked or suspended by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas under

Section 87 of the Manual of Regulations on Foreign Exchange Transactions. More than this,

the banks failure in its obligation given media coverage and the non-legal slant it can give gives

rise to a real danger that the banks reputation may suffer. In a very bad situation, the effect

goes beyond the banks reputation and can adversely affect the economy.

The only exception provided by the law is when there is a written permission by the

depositor. Jurisprudence declares that there is only a single exception to the secrecy of foreign

currency deposits, that is, disclosure is allowed only upon the written permission of the

depositor. This single excepting circumstance, however, does not obtain in the present case;

hence, the banks petition.

RA No. 6426, by its plain terms, is clear that all foreign currency deposits are considered

to be absolutely confidential. The law expressly refers to deposits not to the identity, nationality,

or residence of the depositors. Thus, to claim that the depositors must be considered is

misplaced. Also, to so claim is to read into the clear words of the law exemptions that its literal

wording does not support. To so claim may even amount to judicial legislation.

You might also like

- RP-US Non-Surrender Agreement UpheldDocument3 pagesRP-US Non-Surrender Agreement UpheldTasneem C BalindongNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna v. RomuloDocument6 pagesBayan Muna v. RomuloBill MarNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna Vs RomuloDocument7 pagesBayan Muna Vs RomuloRose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- ICC – RP-US Non-Surrender Pact UpheldDocument29 pagesICC – RP-US Non-Surrender Pact UpheldReyshanne Joy B MarquezNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna Vs Romulo G. R. No. 159618, February 01, 2011 FactsDocument27 pagesBayan Muna Vs Romulo G. R. No. 159618, February 01, 2011 FactsReyshanne Joy B MarquezNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna vs Romulo: RP-US Non-Surrender Agreement UpheldDocument14 pagesBayan Muna vs Romulo: RP-US Non-Surrender Agreement UpheldReyshanne Joy B MarquezNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna vs Romulo: RP-US Non-Surrender Agreement UpheldDocument17 pagesBayan Muna vs Romulo: RP-US Non-Surrender Agreement UpheldReyshanne Joy B MarquezNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna vs Romulo: RP-US Non-Surrender Agreement UpheldDocument25 pagesBayan Muna vs Romulo: RP-US Non-Surrender Agreement UpheldReyshanne Joy B MarquezNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna Vs Romulo G. R. No. 159618, February 01, 2011 FactsDocument13 pagesBayan Muna Vs Romulo G. R. No. 159618, February 01, 2011 FactsReyshanne Joy B MarquezNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna Vs Romulo G. R. No. 159618, February 01, 2011 FactsDocument8 pagesBayan Muna Vs Romulo G. R. No. 159618, February 01, 2011 FactsReyshanne Joy B MarquezNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna vs Romulo: RP-US Non-Surrender Agreement UpheldDocument5 pagesBayan Muna vs Romulo: RP-US Non-Surrender Agreement UpheldReyshanne Joy B MarquezNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna Vs Romulo G. R. No. 159618, February 01, 2011 FactsDocument23 pagesBayan Muna Vs Romulo G. R. No. 159618, February 01, 2011 FactsReyshanne Joy B MarquezNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna vs Romulo Agreement ValidityDocument13 pagesBayan Muna vs Romulo Agreement ValidityEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Case DIEgestDocument14 pagesCase DIEgestJustine SalcedoNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna v. RomuloDocument46 pagesBayan Muna v. RomuloArahbellsNo ratings yet

- BAYAN MUNA VS. ROMULO: RP-US NON-SURRENDER PACT UPHELDDocument5 pagesBAYAN MUNA VS. ROMULO: RP-US NON-SURRENDER PACT UPHELDMa Gabriellen Quijada-TabuñagNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna vs. RomuloDocument5 pagesBayan Muna vs. RomuloSKSUNo ratings yet

- SIL Chap 1-4Document31 pagesSIL Chap 1-4Nicky Jonna Parumog PitallanoNo ratings yet

- Bayanmuna Vs RomuloDocument8 pagesBayanmuna Vs RomuloReth GuevarraNo ratings yet

- HR Cases 2Document6 pagesHR Cases 2Mary Kristin Joy GuirhemNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna vs Romulo - Analyzing the legality of the RP-US Non-Surrender AgreementDocument100 pagesBayan Muna vs Romulo - Analyzing the legality of the RP-US Non-Surrender AgreementAnne Ausente BerjaNo ratings yet

- Romulo CaseDocument7 pagesRomulo CasevalnusNo ratings yet

- Philippine Law Case Digests - Bayan Muna vs. Romulo - GR No. 159618 Case DigestDocument5 pagesPhilippine Law Case Digests - Bayan Muna vs. Romulo - GR No. 159618 Case DigestMoonNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna V RomuloDocument4 pagesBayan Muna V Romuloamun dinNo ratings yet

- Bayan V RomuloDocument46 pagesBayan V Romulobarrystarr1No ratings yet

- Bayan Muna vs. RomuloDocument5 pagesBayan Muna vs. RomuloCarlota Nicolas VillaromanNo ratings yet

- Bayan Vs RomDocument5 pagesBayan Vs RomRenz GuiangNo ratings yet

- PIL Case DigestDocument12 pagesPIL Case DigestkazekyohNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Laws (Compilation)Document18 pagesConflict of Laws (Compilation)Louie SalazarNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna Vs RomuloDocument11 pagesBayan Muna Vs RomuloJohn Carlo DizonNo ratings yet

- Case Digest - Bayan Muna Vs RomuloDocument5 pagesCase Digest - Bayan Muna Vs RomuloJan Michael Jay CuevasNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna V RomuloDocument14 pagesBayan Muna V RomuloLorelei B RecuencoNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 159618 Bayan Muna V RomuloDocument1 pageG.R. No. 159618 Bayan Muna V RomuloEirlys VerlorenNo ratings yet

- Bayan V RomuloDocument23 pagesBayan V RomuloShugen CoballesNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna vs Romulo AgreementDocument2 pagesBayan Muna vs Romulo Agreementxyrakrezel100% (1)

- WHO Vs Aquino Case Digest: FactsDocument12 pagesWHO Vs Aquino Case Digest: FactsAlelie BatinoNo ratings yet

- PIL Digested CasesDocument7 pagesPIL Digested CasesAnonymous tFBz4SNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna v. Alberto Romulo, G.R. No. 159618, Feb. 1, 2011, J. VELASCO, JRDocument2 pagesBayan Muna v. Alberto Romulo, G.R. No. 159618, Feb. 1, 2011, J. VELASCO, JRAntonio Reyes IVNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna v. RomuloDocument46 pagesBayan Muna v. RomuloJean Monique Oabel-TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna v. RomuloDocument56 pagesBayan Muna v. Romuloann laguardiaNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 SIDocument7 pagesAssignment 1 SIandalchiara4No ratings yet

- Bayan Muna vs. RomuloDocument21 pagesBayan Muna vs. RomuloDANICA FLORESNo ratings yet

- BAYAN MUNA V. ROMULO G.R. No. 159618Document21 pagesBAYAN MUNA V. ROMULO G.R. No. 159618salemNo ratings yet

- GR No. 159618: Bayan Muna Vs RomuloDocument13 pagesGR No. 159618: Bayan Muna Vs RomuloteepeeNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna Vs RomuloDocument40 pagesBayan Muna Vs RomuloHannah ValerioNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna Vs Romulo 641 SCRA 244 (2011)Document45 pagesBayan Muna Vs Romulo 641 SCRA 244 (2011)FranzMordenoNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna As Represented by Rep Satur Ocampo Et Al Vs Alberto Romulo in His Capacity As Executive Secretary Et AlDocument58 pagesBayan Muna As Represented by Rep Satur Ocampo Et Al Vs Alberto Romulo in His Capacity As Executive Secretary Et AlShannin MaeNo ratings yet

- Constitutionality of RP-US Non-Surrender AgreementDocument15 pagesConstitutionality of RP-US Non-Surrender AgreementJoshua Buenaobra CapispisanNo ratings yet

- Philippines Upholds Non-Surrender Agreement with USDocument3 pagesPhilippines Upholds Non-Surrender Agreement with USKarinNo ratings yet

- RP-US Non-Surrender Agreement challengedDocument37 pagesRP-US Non-Surrender Agreement challengedRea Jane B. MalcampoNo ratings yet

- Bayanmuna V RomuloDocument27 pagesBayanmuna V RomuloDorothy PuguonNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna v. Romulo and Ople ruling upholds US-PH non-surrender pactDocument2 pagesBayan Muna v. Romulo and Ople ruling upholds US-PH non-surrender pactJimboy Fernandez100% (2)

- Bayan Muna v. RomuloDocument17 pagesBayan Muna v. RomuloQueen PañoNo ratings yet

- BAYAN MUNA V Romulo - Section 21Document3 pagesBAYAN MUNA V Romulo - Section 21Kiana AbellaNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna Vs RomuloDocument2 pagesBayan Muna Vs RomuloGladys CubiasNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna Vs Romulo 641 Scra 244Document61 pagesBayan Muna Vs Romulo 641 Scra 244Ronald Alasa-as AtigNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna v. Alberto Romulo G.R. No. 159618, February 1, 2011Document34 pagesBayan Muna v. Alberto Romulo G.R. No. 159618, February 1, 2011Mark Joseph ManaligodNo ratings yet

- Bayan Muna v. RomuloDocument44 pagesBayan Muna v. RomuloChriscelle Ann PimentelNo ratings yet

- Consular convention Between the People's Republic of China and The United States of AmericaFrom EverandConsular convention Between the People's Republic of China and The United States of AmericaNo ratings yet

- Law School Survival Guide: Outlines and Case Summaries for Torts, Civil Procedure, Property, Contracts & Sales, Evidence, Constitutional Law, Criminal Law, Constitutional Criminal Procedure: Law School Survival GuidesFrom EverandLaw School Survival Guide: Outlines and Case Summaries for Torts, Civil Procedure, Property, Contracts & Sales, Evidence, Constitutional Law, Criminal Law, Constitutional Criminal Procedure: Law School Survival GuidesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Case Digest of The Corfu Channel CaseDocument4 pagesCase Digest of The Corfu Channel CaseKukuruuNo ratings yet

- Jus Cogens Norms ExplainedDocument20 pagesJus Cogens Norms ExplainedKukuruuNo ratings yet

- Samplexxxx MTPILDocument2 pagesSamplexxxx MTPILKukuruuNo ratings yet

- Case Digest Barcelona Traction Public International LawDocument2 pagesCase Digest Barcelona Traction Public International LawKukuruuNo ratings yet

- Philippine sovereignty and international agreementsDocument25 pagesPhilippine sovereignty and international agreementsKukuruuNo ratings yet

- Jus Cogens Norms ExplainedDocument20 pagesJus Cogens Norms ExplainedKukuruuNo ratings yet

- Jus Cogens Norms ExplainedDocument20 pagesJus Cogens Norms ExplainedKukuruuNo ratings yet

- How To Make Rainbow Stuffing MacaroonsDocument4 pagesHow To Make Rainbow Stuffing MacaroonsKukuruuNo ratings yet

- How To Cook Sinigang Na Bagang Part 8Document6 pagesHow To Cook Sinigang Na Bagang Part 8KukuruuNo ratings yet

- How To Cook Adobong Diggie Part 1Document7 pagesHow To Cook Adobong Diggie Part 1KukuruuNo ratings yet

- How To Cook Sinigang Na Bagang Part 7Document7 pagesHow To Cook Sinigang Na Bagang Part 7KukuruuNo ratings yet

- Regains Sanity That Is Sufficient To Regain The Legal Capacity To Contract, Make A Will and ToDocument17 pagesRegains Sanity That Is Sufficient To Regain The Legal Capacity To Contract, Make A Will and ToKukuruuNo ratings yet

- How To Make Rainbow Stuffing MacaroonsDocument4 pagesHow To Make Rainbow Stuffing MacaroonsKukuruuNo ratings yet

- How To Make Rainbow Cloud Formation BerriesDocument4 pagesHow To Make Rainbow Cloud Formation BerriesKukuruuNo ratings yet

- How To Cook Sinigang Na Bagang Part 4Document9 pagesHow To Cook Sinigang Na Bagang Part 4KukuruuNo ratings yet

- How To Make Rainbow Bitsfood Part 1Document2 pagesHow To Make Rainbow Bitsfood Part 1KukuruuNo ratings yet

- How To Cook Sinigang Na Bagang Part 5Document6 pagesHow To Cook Sinigang Na Bagang Part 5KukuruuNo ratings yet

- How To Cook Sinigang Na Bagang Part 2Document3 pagesHow To Cook Sinigang Na Bagang Part 2KukuruuNo ratings yet

- Sinampalukang ManokDocument6 pagesSinampalukang ManokKukuruuNo ratings yet

- How To Cook Sinigang Na Bagang Part 6Document4 pagesHow To Cook Sinigang Na Bagang Part 6KukuruuNo ratings yet

- How To Cook Sinigang Na Bagang Part 1Document6 pagesHow To Cook Sinigang Na Bagang Part 1KukuruuNo ratings yet

- Pagasus Pantasi EmeruttylullyDocument14 pagesPagasus Pantasi EmeruttylullyKukuruuNo ratings yet

- Pagasus Pantasi Emeruttylully EmelatikDocument15 pagesPagasus Pantasi Emeruttylully EmelatikKukuruuNo ratings yet

- Perseus Quest Gorgon MedusaDocument14 pagesPerseus Quest Gorgon MedusaKukuruuNo ratings yet

- Pagasus Pantasi EmeruttyDocument14 pagesPagasus Pantasi EmeruttyKukuruuNo ratings yet

- Perseus' QuestDocument14 pagesPerseus' QuestKukuruuNo ratings yet

- SAMPLEX KinemeDocument3 pagesSAMPLEX KinemeKukuruuNo ratings yet

- Kinemengdemolovpt 5Document9 pagesKinemengdemolovpt 5KukuruuNo ratings yet

- Kinemengdemolovpt 4Document9 pagesKinemengdemolovpt 4KukuruuNo ratings yet

- New Search Warrants in Erica Parsons CaseDocument8 pagesNew Search Warrants in Erica Parsons CaseTrue Crime ReviewNo ratings yet

- Double Sales - First Possession in Good Faith PrevailsDocument2 pagesDouble Sales - First Possession in Good Faith PrevailsMaribel Nicole LopezNo ratings yet

- 0 - Rabara Carl Joseph - Ethics Activity 15Document2 pages0 - Rabara Carl Joseph - Ethics Activity 15Carl Joseph RabaraNo ratings yet

- A Birth Certificate Is A Negotiable InstrumentDocument5 pagesA Birth Certificate Is A Negotiable InstrumentAnonymous uAhvA5fkDF100% (16)

- Selected Bibliography of Material On The Paakantyi / Paakantji / Barkindji Language and People Held in The AIATSIS LibraryDocument41 pagesSelected Bibliography of Material On The Paakantyi / Paakantji / Barkindji Language and People Held in The AIATSIS LibraryMichael O'DwyerNo ratings yet

- FormsDocument78 pagesFormsdieranadiaNo ratings yet

- DEPED PoP Form 6 Memorandum of AgreementDocument2 pagesDEPED PoP Form 6 Memorandum of Agreementyachiru121100% (1)

- Brother ATM - BenniDocument3 pagesBrother ATM - BenniFrancis CalubayanNo ratings yet

- UPAN Newsletter Volume 8 Number 10 October 2021 CorrectedDocument10 pagesUPAN Newsletter Volume 8 Number 10 October 2021 CorrectedUtah Prisoner Advocate NetworkNo ratings yet

- Personal Data Sheet FormDocument8 pagesPersonal Data Sheet Formraymond mangilitNo ratings yet

- KURUKSHETRA 2023 Rules and RegulationsDocument5 pagesKURUKSHETRA 2023 Rules and RegulationsGleeson fernandesNo ratings yet

- @csupdates Chapter 21 CIRP, Liquidation Wining Up SBECDocument29 pages@csupdates Chapter 21 CIRP, Liquidation Wining Up SBECthevinayakshuklaaNo ratings yet

- #34 SHIRLEY F. TORRES v. IMELDA PEREZ, GR No. 188225, 2012-11-28Document3 pages#34 SHIRLEY F. TORRES v. IMELDA PEREZ, GR No. 188225, 2012-11-28Denise DianeNo ratings yet

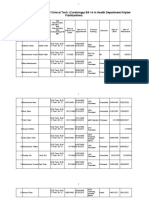

- Provincial Seniority List of Clinical Tech: (Cardiology) BS-14 in Health Department Khyber PakhtunkhwaDocument82 pagesProvincial Seniority List of Clinical Tech: (Cardiology) BS-14 in Health Department Khyber PakhtunkhwaNuman Khan33% (3)

- CL Agrawal Moot Proposition 2018Document6 pagesCL Agrawal Moot Proposition 2018Shivika Bagga0% (1)

- JB APUSH Unit 3 Topic 3.7Document9 pagesJB APUSH Unit 3 Topic 3.7Graham NicholsNo ratings yet

- Hutchinson - Nationalism and WarDocument14 pagesHutchinson - Nationalism and WarermineaboutNo ratings yet

- Al-Kafi, v. 8, Pt. 2Document0 pagesAl-Kafi, v. 8, Pt. 2pitzeleh8No ratings yet

- Imperialism IN Heart of Darkness: Made By: Ikramul HussainDocument9 pagesImperialism IN Heart of Darkness: Made By: Ikramul HussainIkramul HussainNo ratings yet

- 10 Tieng v. AlarasDocument41 pages10 Tieng v. AlarasJo Marie SantosNo ratings yet

- Armas Vs CalisterioDocument1 pageArmas Vs CalisterioRap PatajoNo ratings yet

- DND Next DM Screen ColorDocument3 pagesDND Next DM Screen ColorJosé Apolinar Díaz Gobín100% (1)

- Left 4 Dead CheatsDocument4 pagesLeft 4 Dead CheatsAl Muzammil MuhamadNo ratings yet

- Salient Features of The Representation of PeopleDocument4 pagesSalient Features of The Representation of PeoplegarimaNo ratings yet

- 06-21-10 - Notice of Voluntary DismissalDocument5 pages06-21-10 - Notice of Voluntary DismissalOrlando Tea PartyNo ratings yet

- A Grain of WheatDocument4 pagesA Grain of WheatBalkrishna Waghmare0% (1)

- Assignment of Cyber LawDocument6 pagesAssignment of Cyber LawBhartiNo ratings yet

- Stages of Japanese Imperialism 1894-1945Document15 pagesStages of Japanese Imperialism 1894-1945smrithiNo ratings yet

- DOJ: Buffett-Owned Mortgage Firm Guilty of Redlining in NCCoDocument50 pagesDOJ: Buffett-Owned Mortgage Firm Guilty of Redlining in NCCoCharlie MegginsonNo ratings yet

- Form I National Cadet Corps Senior Division/Wing Enrolment Form (See Rules 7 and 11 of NCC Act, 1948)Document4 pagesForm I National Cadet Corps Senior Division/Wing Enrolment Form (See Rules 7 and 11 of NCC Act, 1948)Vikram ChauhanNo ratings yet