Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pediatric Advanced Life Support Provider Manual (PDFDrive)

Uploaded by

will0%(1)0% found this document useful (1 vote)

213 views286 pagesPALS Manual from 2012

Original Title

Pediatric Advanced Life Support Provider Manual ( PDFDrive )

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentPALS Manual from 2012

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0%(1)0% found this document useful (1 vote)

213 views286 pagesPediatric Advanced Life Support Provider Manual (PDFDrive)

Uploaded by

willPALS Manual from 2012

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 286

a

=. American Neen nan

a t Heart POR Curiae i.

a CSET (a

Pediatric

Advanced Life Support

ev har

as gee

a

é

a

Ltr

Pediatric

American

Heart

Associations

Advanced Life Support

PROVIDER MANUAL

Editors

Leon Chameides, MD, Conient Consultant

Ficardo A, Samson, MD, Associete Science Editor

Stephen M. Schesnaydor, MD, Associate Science Ealtor

Mary Fran Hazinski, PN, MSN, Senior Science Editor

‘Senior Managing Editor

Jennifer Asheraft, RN, BSN

Special Contributors

Mare D. Berg, MO

efirey M, Berman, MD

Laure Goniey, BS, RAT, ACP, NPS

Allen Fi. de Gaen, MD

‘Aaron Donoghue, MD, MSCE

Melinda L. Fiedor Hamiton, MID, MSc

Monica €. Kleinman, MD

‘Mary Ann Mctiel, MA, NREMT-P

Brenda Schoolfeld, PALS Writer

Cindy Tuttle, BN, BSN

‘Salle Young, PharmD, BOPS, Pharmacotherapy Editor

© 2011 Amarcan Heart Association

ISBN 076-0-67403-527-1

Printed in the United States ot America

Fst American Heart Associaton Priving Octobor 2011

10987654321

Pediatric Subcommittee 2010-2011

Mare D. Berg, MD, Chair

Monica E. Kloinman, MD, Immediate Past Chair, 2007-2009

ina L. Atkins, MD

Kathleen Brown, MD.

‘Adam Cheng, MD

Leura Conley, BS, RAT, ROP, NPS.

‘Allan R. de Caen, MD

Aaron Donoghue, MD, MSCE

Melinda L. Fiedor Hamiton, MD. MSC

Ericka L. Fink, MD

Eugene B. Freid, MO

Cheryl K. Gooden, MD

Sharon E Mace, MD

Bradley S. Marino, MD, MPP, MSCE

Feylon Meeks, RN, BSN, MS, MSN, EMT, PhD

Jeffrey M. Perlman, MB, ChE

Lester Proctor, MD

Faiga A. Qureshi, MD

Kennith Hans Sartoretl, MD

Wendy Simon, MA

Mark A. Terry, MPA, NREMT-P

Avoxis Topjan, MD

Else W. van der Jagt, MD, MPH

Parti

Course Overview

Course Objectives

Cognitive Course Objectives

Psychomotor Course Objectives

Course Description

BLS Competency Testing

Skills Stations

PALS Core Case Discussions and

‘Simulations

PALS Core Case Testing Stations

Written Exam

Precourse Preparation

Precourse Self-Assessment

BLS Skills

ECG Rhythm identification

Basic Pharmacology

Practical Application of Knowledge

to Clinical Scenarios

Course Materials

PALS Provider Manual

PALS Student Website

Course Completion Requirements

Suggested Reading List

6862088 8m NNN A GS

aooe ee

Part 2

Systematic Approach to the

Seriously Hl or Injured Child

Overview

Rapid Intervention to Prevent

Cardiac Arrest

Learning Objectives

Preparation for the Course

PALS Systematic Approach Algorithm

Initial Impression

Evaluate-Identify-Intervene

Evaluate

Identity

Intervene

Continuous Sequence

Determine If Problem Is

Life Threatening

Primary Assessment

Airway

Breathing

Circulation

Disability

Exposure

Life-Threatening Problems

Interventions

Secondary Assessment

Focused History

Focused Physical Examination

Diagnostic Tests

Arterial Blood Gas

Venous Blood Gas

Hemoglobin Concentration

Central Venous Oxygen Saturation

Arterial Lactate

Central Venous Pressure Monitoring

Invasive Arterial Pressure Monitoring

Chest X-Ray

Electrocaraiogram

Echocardiogram

Peak Expiratory Flow Rate

‘Suggested Reading List

Part 3

Effective Resuscitation

Team Dynamics

Overview

Learning Objectives

Preparation for the Course

Roles of the Team Leader and

Team Members

Role of the Team Leader

Role of the Team Member

Elements of Effective Resuscitation

‘Team Dynamics

Closed-Loop Communication

Clear Messages

Clear Roles and Responsibilities

Knowing Limitations

Knowledge Sharing

SBRBSRRB

8

BBBBBEBBSY

Se eee 8

Constructive Intervention

Reevaluation and Summarizing

Mutual Respect

Suggested Reading List

Part 4

Recognition of Respiratory

Distress and Failure

Overview

Learning Objectives

Preparation for the Course

Fundamental Issues Associated With

Respiratory Problems

Impairment of Oxygenation and

Ventilation in Respiratory Problems

Physiology of Respiratory Disease

Identification of Respiratory

Problems by Severity

Respiratory Distress

Respiratory Failure

Identification of Respiratory

Problems by Type

Upper Airway Obstruction

Lower Airway Obstruction

Lung Tissue Disease

Disordered Contro! of Breathing

Summary: Recognition of

Respiratory Problems Flowcharts

Suggested Reading List

Part 5

Management of Respiratory

Distress and Failure

Overview

Learning Objectives

Preparation for the Course

Initial Management of Respiratory

Distress and Failure

Principles of Targeted Management

Management of Upper

Airway Obstruction

General Management of Upper

Airway Obstruction

Specific Management of Upper

Airway Obstruction by Etiology

Management of Lower Airway

Obstruction

General Management of Lower

Airway Obstruction

Specific Management of Lower

Airway Obstruction by Etiology

Management of Lung Tissue Disease

Goneral Management of Lung

Tissue Disease

Specific Management of Lung

Tissue Disease by Etiology

dered

Management of

Control of Breathing

General Management of Disordered

Control of Breathing

Specific Management of Disordered

Control of Breathing by Etiology

‘Summary: Management of

Respiratory Emergencies Flowchart

Suggested Reading List

Resources for Management of

Respiratory Emergencies

Bag-Mask Ventilation

Overview

Preparation for the Course

How to Select and Prepare the

Equipment

49

50

50

ot

52

82

55

87

87

59

61

6

61

61

61

How to Test the Device

How to Position the Child

How to Perform Bag-Mask Ventilation

How to Deliver Effective Ventilation

Endotracheal Intubation

Potential Indications

Preparation for Endotracheal

Intubation

Part 6

Recognition of Shock

Overview

Learning Objectives

Preparation for the Course

Definition of Shook

Pathophysiology of Shock

‘Components of Tissue

Oxygen Delivery

Stroke Volume

Compensatory Mechanisms

Effect on Blood Pressure

Identification of Shock by Severity

(Effect on Blood Pressure)

Compensated Shock

Hypotensive Shock

Identification of Shock by Type

Hypovolemic Shock

Distributive Shock

Cardiogenic Shock

Obstructive Shock

Recognition of Shock Flowchart

Suggested Reading List

838

70

nm

Rn

2

Part 7

Management of Shock

Overview

Learning Objectives

Preparation for the Course

Goals of Shock Management

Warning Signs

Fundamentals of Shock

Management

Optimizing Oxygen Content of

the Blood

Improving Volume and Distribution

of Cardiac Output

Reducing Oxygen Demand

Correcting Metabolic Derangements

Therapeutic End Points

General Management of Shock

Components of General

Management

Summary: initial Management

Principles

Fluid Therapy

‘sotonic Crystalloid Solutions

Colloid Solutions

Crystalloid vs Colloid

Rate and Volume of Fluid

Administration

Rapid Fluid Delivery

Frequent Reassessment During

Fluid Resuscitation

Indication for Blood Products

Complications of Rapid

Administration of Blood Products

Glucose

Glucose Monitoring

Diagnosis of Hypoglycemia

Management of Hypoglycemia

Management According to.

Type of Shock

Management of Hypovolemic Shock

‘Management of Distributive Shock

‘Management of Septic Shock

Management of Anaphylactic Shock

Management of Neurogenic Shock

Management of Cardiogenic Shock

‘Management of Obstructive Shock

Management of Shock Flowchart

Suggested Reading List

Resources for Management of

Circulatory Emergencies 109

Intraosseous Access 109

Sites for 10 Access 109

Contraindications 109

Procedure (Proximal Tibia) 109

After IO Insertion

Color-Coded Length-Based

Resuscitation Tape

Part 8

Recognition and Management

of Bradycardia

Overview

Learning Objectives

Preparation for the Course

Definitions

Recognition of Bradycardia

Signs and Symptoms of Bradycardia

ECG Characteristics of Bradycardia

Types of Bradyarrhythmias

Management: Pediatric Bradycardia ‘Summary of Emergency

With a Pulse and Poor Perfusion Interventions 499

Algorithm 117 Pediatric Tachycardia With a Pulse

Identify and Treat Underlying and Adequate Perfusion Algorithm 134

Cause (Box 1) 118 Initial Management (Box 1) 135

Reassess (Bax?) in Evaluate QRS Duration (Box 2) 135

i Adequate Respiration and

Perfusion (Box 4a) 118 et con of ari § 195

ip apscycatei rel CespRCAY Treat Cause of SVT (Boxes 7 and 8) 135

‘Compromise Persist: Perform Wide QRS, Possible VT vs SVT

CPR (Box 3) 118 (Boxes 9, 10, and 17) 135

Reassess Rhythm (Box 4) 119 Pharmacologic Conversion vs

‘Administer Medications (Box 5) 119 Eleven! ee a ° iad

Pediatric Tachycardia With a Pulse

Consider Cardiac Pacing (60x 5) 118 snd Poor Perfusion Algorithm ‘se

Treat Underlying Causes (Box 5) 120 Initial Management (Box 1) 4138

Pulseless Arrest (Box 6) 170) Evaluate QRS Duration (Box 2) 138

Suagested Reacing List 10 Treat Cause of ST (Box 6) 138

Treatment of SVT (Boxes 7 and 8) 198

Part 9 Wide QRS, Possible VT (Box9) 139

Recognition and Management Suggested Reading List 139

of Tachycardia 121

Overview 4

‘ Part 10

Learning Objecti 121

4 SERNOE Recognition and Management

Preparation for the Course 121 Of Cardiac Arrest ia

Tachyarrhythmias ‘21 Otervion 14

Recognition of Tachyarrhythmias 121 earring Objectives 1

Sinsand Symptoms 1 Preparation for the Course 142

Effect on Cardiac Outout 121 Definition of Cardiac Arrest 142

Classification of Tachycardia and Pathiaya te carcasa’nireat: sao

Tachyarthythmias 122 ihepih

Management of Tachyarrhythmias 126 Hypoxia om ne aes ve

ie 142,

Initial Management Questions 126 Sudden Cardiac Arrest

Fh ; Causes of Cardiac Arrest 149

Initial Management Priorities 126

; Recognition of Cardiopulmonary

Emergency interventions 126 oe tae

Recognition of Cardiac Arrest

Arrest Rhythms

Management of Cardiac Arrest

High-Quality CPR

Monitoring for CPR Quality

Pediatric Advanced Life Support in

Cardiac Arrest

Pediatric Cardiac Arrest Algorithm

Pediatric Cardiac Arrest: Special

Circumsiances

Social and Ethical Issues in

Resuscitation

Family Presence During

Resuscitation

Terminating Resuscitative Efforts

“Do Not Attempt Resuscitation” or

“Allow Natural Death” Orders

Predictors of Outcome After

Cardiac Arrest

Factors That Influence Outcome

Postresuscitation Management

Suggested Reading List

Part 11

Postresuscitation Management 171

Overview 471

Learning Objectives

Preparation for the Course

Postresuscitation Management

Primary Goals

Systematic Approach

Respiratory System

Management Priorities

General Recommendations

Cardiovascular System

Management Prioritios

General Recommendations

PALS Postresuscitation Treatment

of Shock

‘Administration of Maintenance Fluids

Neurologic System

‘Management Priorities

General Recommendations

Renal System

Management Priorities

General Recommendations

Gastrointestinal System

Management Priorities

General Recommendations

Hematologic System

‘Management Priorities

General Recommendations

Postresuscitation Transport

Coordination With Receiving Facility

Advance Preparation for Transport

Infectious Disease Considerations

Immediate Preparation Before

Transport

Communication Between Referring

and Receiving Healthcare Providers

Communication Among Facilities

and With Other Healthcare Providers

Communication With the Family

Posttransport Documentation and

Follow-up

Mode of Transport and Transport

Team Composition

Transport Triage

Suggested Reading List

Part 12 Terbutaline 21 |

Pharmacology 199 Vasopressin 202

Overview 199 |

Preparation for the Course 198 aul

Pharmacology pees : a

‘Silonosine noo BLS Competency Testing 238

‘Alburnin nen ats Skis Testing Sheets ao

easel = inal fie Child BLS With “|

" a ;cuer itl

Alprostadil (Prostegiendin E; (PGE) 203 AED Skills Testing Sheet 234 |

‘Amiodarone: a0 7- and 2-Rescuer Child BLS |

Atropine 205 With AED Skills Testing Criteria |

Calcium Chioride 207 and Descriotars x

ipassineannacons Ba Jeg 2-Rescuer Infant BLS Skiis

Dextrose’ (Giana) m0. 1- and 2-Rescuer Infant BLS Skill

Diphenhydramine 210 Testing Criteria and Descriptors. 237

Dobutamine 211 Skills Station Competency

Depitnie 212 Checklists 230

Epinephrine a Management of Respiratory

' Emergencies Skills Station

Etomidate 215 Competency Checkiist 239

Furosemide 216 Rhythm Disturbances/Electrical

Hydrocortisone 27 Therapy Skills Station

Competency Checkiist 240

Inamrinone (Amrinone) 210

‘ ; Vascular Access Skills Station

Ipratropium Bromide ae Competency Checklist 240

Ddecaine 2m: Rhythm Recognition Review 2a

Magnesium Sulfate aan Learning Station Competency

Methylprednisolone 222 Checklists 246

Milrinone 220 Respiratory Learning Station

iiSnene a Competency Checkists 216

Shock Learning Station

Niregyoain 8 Competency Checklists 250

Nitroprusside : ;

prussi , Cardiac Learning Station

(Sealant Nireprassiag 28 Competency Checklists 254

Norepinephrine 227 PALS Systematic Approach

Oxygen 228 = Summary 258

Procainamide 229 Index 261

Sodium Bicarbonate 230

Course Overview

Course Objectives

‘The Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) Provider

Course is designed for healthcare providers who initiate

‘and direct basic through advanced life support. Course

‘concepts are designed to be used throughout the stabil

zation and transport phases for both in-hospital and out-

‘of-hospital pediatric emergencies. n this course you wil

‘enhance your skils in the evaiuation and management of

an infant or child with respiratory compromise, circulatory

compromise, or cardiac arrest.

During the course you will actively participate in a series of

simulated core cases. These simulations are designed to

reinioxce Important concepts, including

* Identification and treatment of problems that place the

child at risk for cardiac arest

+ Application of a systematic approach to pediatric

assessment

** Use of the “evaluate-identiy-intervene” sequence

** Use of PALS algorithms and flowcharts

‘+ Demonstration of effective resuscitation team dynamics

Cognitive Course Objectives

Upon successful completion ofthis course, you should be

able 10 do the following, independently, when presented

with a scenario of aeriticaly il or injured pedietic patent:

+ Describe the timaly recognition and interventions,

required to prevent respiratory and cardiac arrest in any

pediatric patient

* Describe the systematic approach to pediatric assess~

ment by using the intial impression, primary and sec-

ondary assessments, and diagnostic tests

* Describe priorities and specific interventions for

infants and children with respiratory and/or circulatory

‘emergencies

* Explain the importance of elfective team dynamics,

including individual roles and responsibilities, during a

peciatric resuscitation

* Describe the key elements of postresuscitation

management

Psychomotor Course Objectives

Upon successful completion of this course, you should be

‘able to do the following, independently, when presented

with a scenario of a criticaly il or injured pediatric patient:

+ Perform effective, high-quality cardiopulmonary resus-

citation (CPR) when appropriate

« Perform effective respiratory management within your

scope of practice

+ Select and apply appropriate cardiorespiratory

‘monitoring

* Select and admi

ister the appropriate medications and

electrical therapies when presented with an arshythmia

scenario

rapid vascular access to administer fluid and

‘+ Demonstrate affective commurication and team dynam-

cs both as a team member and as a team leader

Pa) The goal of the PALS Provider Course is to improve the quality of care provided to

ee aie seriously il or injured children, resulting in improved outcomes

Course Description

‘To help you achieve these objectives the PALS Provider

Course includes

+ Basic life support (BLS) competency testing

Skils stations.

*+ Core case discussions and simulations

+ Core case testing stations

* Auritten exam

BLS Competency Testing

You must pass 2 BLS tests to receive an American Heart

‘Association (AHA) PALS Provider course completion card

Se ee

Pass 1- and 2-Rescuer Child BLS With AED Skills Test

+ Pass 1- and 2-Rescuer Infant BLS Skills Test

‘The PALS Provider Course does not include detalied

instruction on how to perform basic CPR or how to use an

automated external defibilator (AED). You must know this

in advance. Consider taking a BLS for Healthcare Providers

Course if necessary. Before taking the PALS Course, review

the student BLS practice sheets and BLS skills testing

sheets in the Appendix. Also see Table 1: Summary of Key

BLS Components for Adults, Chiléren, and Infants and the

Padiatric Cardiac Arrest Algorithm in Part 10: “Recognition

and Management of Cardiac Arrest.”

Skills Stations

The course includes the foliowing skils stations:

‘+ Management of Respiratory Emergencies

‘+ Rhythm Disturbances/Electrical Therapy

* Vascular Accoss

During the skills stations you will have an opportunity to

practice specific skils and thon demonstrate competency.

Below is a brief description of each station. During the

course you will use the skills stations competency chack-

lists while practicing the skills. Your instructor wil evaluate

your skills based on the criteria specified in these check-

lists. See the Appendix for the sills station chockiste,

which list detailed steps for performing each skil.

Management of Respir

Skills Station

tory Emergencies

In the Management of Respiratory Emergencies Skils

Station you will need to demonstrate your understanding of

oxygen (0,) delivery systems and airway adjuncts. You will

have an opportunity to practice and demonstrate compe-

tency in airway management skils. including

* Insertion of an oropharyngeal airway (OPA)

+ Effective bag-mask ventilation

‘+ OPA and endotracheal (ET) tube suctioning

‘+ Confirmation of advancad airway device placement by

‘hysical examination and an exhaled carbon dioxice

(CO,) detector device

* Securing tho ET tube

{itis within your scope of practice, you may be asked io

demonstrate advanced airway skills, including corect inser

tion of an ET tube.

Rhythm Disturbances/Electrical Therapy

Skills Station

In the Rhythm Disturbances/Electrical Therapy Skills Station

you will have an opportunity to practice and demonstrate

‘competency in rhythm identfication and operation of a car-

iac monitor and manual defibrillator. Skills include

* Correct placement of electrocardiographic (ECG) leads

* Correct paddle/electrode pad selection and placement!

positioning

* Identification of rhythms that require defibrillation

* Identification of rhythme that roquire synchronized

cardioversion

* Operation of a cardiac monitor

* Sale performance of manual defibrillation and synchro:

rized cardioversion

Vascular Access Skills Station

In the Vascular Access Skils Station you will have an

‘opportunity to practice and demonstrate competency in

intreosseous (IO) access and other related skills. In this

skills station you will

* Insert an IO needle

+ Summarize how to confirm that the needle has entered

the marrow cavity

+ Summariza/demonstrate the method of giving an intra-

venous ('V)A0 bolus

+ Use a color-coded length-based resuscitation tape to

calculate correct drug doses

PALS Core Case Discussions and

Simulations

In the learning statiors you wil actively participate in a vari-

‘ety of learning activities, including

+ Core case discussions using a systematic approach for

evaluation and decision making

+ Cote case simulations

{n the learning stations you will apply your knowledge and

practice essential skits both individually and as part of a

team, This course emphasizes effective team skills as a

vital part of the resuscitative effort. You will receive train:

ing in effective team behavior and have the opportunity to

practice as a team member and a team leader.

PALS Core Case Testing Stations

At the end of the course you will participate as a team

leader in 2 core case testing stations to validate your

achiavement of the course objectives. You will be per-

mitted to use the PALS pocket reference card and the

2010 Handbook of Emergency Cardiovascular Care tor

Healthcare Providers, These SmUlated clinical scenarios will

test the following:

* Ability to evaluate and identity specttic medical prob-

lems covered in the course

+ Recognition and management of respiratory and shook

emergencies

+ Interpretation of core arthythmias and management

using appropriate medications and electrical therapy

* Performance as an effective team leader

‘A major emphasis of this evaluation will be your ability to

direct the integration of BLS and PALS skils by your team

members according to their scope of practice. Review

Part 2: “Effective Resuscitation Team Dynamics” before

‘the course.

Written Exam

‘The writen exam evaluates your mastery of the cognitive

objectives. The written exam is closed-book; no resources

or aids are perritted. You must score 84% or higher on the

written oxam.

Precourse Preparation

“To successtully pass the PALS Provider Course, you must

prepare before the course. Do the following:

+ Takeo the Precourse Self-Assessment

+ Make sure you are proficiant in BLS skils.

+ Practice identifying and interpreting core ECG rhythms,

+ Study basic pharmacology and know when to use

which drug.

+ Practice applying your knowledge to ctnical scenarios.

Precourse Self-Assessment

Se neil:

6 eae

Se see

eee

Serer meee

ear

BLS Skills

‘Strong BLS skills are the foundation of advanced life sup-

port. Everyone involved in the care of pediatric patients

‘must be able to perform high-quality CPR, Without high-

quality CPR, PALS interventions will fail. For this reason,

each student must pass the 1- and 2-Rescuer Child BLS

With AED and 1- and 2-Rescuer Infant BLS Skill Tests in

the PALS Provider Course. Make sure that you are proficient

in BLS skils before attending the course.

‘See the section "BLS Competency Testing” in the Appendix:

{or testing requirements and resources.

ECG Rhythm Identification

‘You must be able to identify and interpret the following core

‘hytbms during case simulations and core case tests:

= Normal sinus rhythm

Sinus bradycardia

Sinus tachycardia

Supraventricular tachycardia

* Ventricular tachycarcia

* Ventricular fioitation

+ Asystole

‘The ECG rhythm identifcation section of the Precourse

‘Self-Assessment will help you evaluate your ability to

identify these core rhythms and other common pediatric

arrhythmias. if you have difficulty with pediatric rhythm

identiication, improve your knowledoe by studying the sec-

tion “Rhythm Recognition Review” in the Appendix. The

AHA also offers self-directed online courses on rhythm ree-

cognition. These courses can be found at OnlineAHA.org.

Basic Pharmacology

‘You must know basic information about drugs used in

the PALS algorithms and flowcharts. Basic pharmacology

information includes the indications, contraindication, and

methods of administration. You will need to know when to

use which drug based on the clinical situation.

‘Tho pharmacology section of the Precourse Self-

Assessment will help you evaluate and enhance your

knowledge of mecications used in the course. If you

have difficulty with this section of the Precourse Self-

Assessment, improve your knowledge by studying

the PALS Provider Manual and the 2010 Handbook of

Emergency Cardiovascular Care for Healthcare Providers.

Practical Application of Knowledge to

Clinical Scenarios

‘The practical application section of the Precourse Self

Assessment wil help you evaluate your ability to apply your

kaowledge when presented with 2 clinical scenaro, You wil

need to make decisions based on

+ Tho PALS Systematic Approach Aigorthm and the

evaluate-identify-niervene sequence

+ identication of core rhythers

+ Knowledge of core medications

+ Knowledge of PALS flowcharts and algorithms

Be sure that you understand the PALS Systematic

PALS Student Website, and 2010 Handbook of Emergency

Cardiovascular Care for Healtncare Providers.

Course Materials

Tho PALS Provider Course matotials consist of the PALS

Provider Manual and supplementary material on the PALS.

Student Webstte

PALS Provider Manual

The PALS Provider Manual contains material that you will

use before, during, and after the course. It contains impor-

tant information that you need 10 know to effectively par=

ticipate in the course, so please read and study the manual

before the course. This important material includes con-

cepts of pediatric evaluation and the recognition and man-

‘agement of respiratory, shock, and carciac emergencies.

‘Some students may already know much of this information;

others may need extensive study before the course.

‘Approach Algorithm and the evaluate-identity-intervene

sequence, Review the core rhythms and medications. Be

familar with the PALS algorithms and flowcharts so that

you can apply them to clinical scenarios. Note that the

PALS Course Goes not teach the details of each algorithm.

Sources of information are the PALS Provider Manua,

The manual is organzed into the following parts:

fea Gok eee ee

Course Overviow What you need to know before the course, how to prepare for the course,

and what to expect during the course

The PALS systematic approach, intial impression, evaluate-identity-inter-

vene sequence, including the primary assessment, secondary assessment,

and diagnostic tests

‘Systematic Approach to the

Seriously Ill or Injured Child

Effective Resuscitation Team

Dynamics

Recognition of Respiratory

Distress and Failure

Roles of team leader and team members; how to effectively communicate

as a team leader or team member

Basic concepts of respiratory cistross and failure; how to identity respica-

tory problems according to type and severity

Management of Respiratory Intervention options for respiratory problems and emergencies

Distress and Failure

Recognition of Shock Basic concepts of shock; shock identification according to type and

severity

Management of Shock

Recognition and Management of

Bradycardia

Intervention options for shock according to etiology

Clinical and ECG characteristics of bradyarthythmias; medical and electri-

cal therapies

Recognition and Management of

Tachycardia

Clinical and ECG characteristics of tachyarihythmias; medical and electr-

cal thorapios |

‘Signs of cardiac arrest and terminal cardiac rhythms; resuscitation and

electrical therapy

Recognition and Management of

Cardiac Arrest

Postresuscitation Management —_| Postresuscitation evaluation and management; postresuecitation traneport

Pharmacology

Appendix

Details about common medications used in pediatric emergencias

Checklists for BLS competency testing, skit stations competencies, and

core case simulations; a brief rhythm recognition review

Throughout the PALS Provider Manual you will find specitic information in the following types of boxes:

‘Type of Box

Coe td

Cee

Remember to take this manual with you to the course.

PALS Student Website

mation about basic PALS concepts,

Eg

rg

‘The Precourse Self-Assessment isa vital part of your preparation for the course. Feedback from this assessment will help

yu identfy gaps in your knowledge so that you can target specific material to study.

eed

eee

eta a

Pe led

the Course

+ Pharmacology

Course Completion Requirements

To successfully complote the PALS Provider Course and

obtain your course completion card, you must do the

folowing:

* Actively participate in, practice, and complete all skills

stations and learning statons

+ Pass the 1- and 2-Rescuer Child BLS With AED and

1 and 2-Reaouer Infant BLS Skills Tests

+ Pass a virtton exam with a minimum score of 84%

+ Pass 2 PALS core caso tests as a team leador

Suggested Reading List

Donoghue A, Nishisaki A, ution R, Hales A, Boulet J

Relitilty end validity of a scoring instrument for clinical

performance during Podiatric Advanced Life Support simu-

lation seenaros. Resuscitation. 2010;81:331-896,

‘Basic information that every PALS provider should know

Important core concepts that are key to caring for critically ill or injured children,

‘An important evaluation or an immediate lifesaving intervention

‘Advanced information that you can use to increase your knowledge but that is not

required for successful course participation

@ Go to the PALS Student Website to access the Precourse Self-Assessment, Here you will also find additional infor-

‘The URL for the PALS Student Website is

www.heart.orgiecestudent

‘To enter the webstte, you will need the access code found at the bottom of page it in

the front of your PALS Provider Manual.

‘The Precourse Self-Assessment has 3 parts:

+ ECG rhythm identiication

* Practical application

Complete these assessments before the course to identify gaps in and improve your

knowledge. Print out your certificate of completion and take it with you to the course.

Hunt EA, Vera K, Diener-West M, Haggerty JA, Nelson

KL, Shatfner DH, Pronovost Pu. Delays and errors in car

diopulmonary resuscitation and defibrillation by pediat-

ric residents during simulated cardiopuimenary arrests.

Resuscitation. 2009;80:819-625.

Niles D, Sutton RM, Donoghue A, Kalsi MS, Roberts K,

Boyle L, Nishisaki A, Arbogast KB, Helfaer M, Nadkami V.

“Rolling Refreshers”: a novel approach to maintain CPR psy-

chomotor skill competence. Resuscitation. 2009:80:909-912,

Roy KM, Miler MP, Schmit K, Sagy M, Pediatric residents

‘experience a significant dectine in their response capabii-

ties to simulated life-threatening events as their training

frequency in cardiopulmonary resuscitation decreases

[pupisned online ahead of print October 1, 2010]. Peotatr

Crit Care Med. doi 10.1097/PCC.0b0198318113a0d

Sutton RM, Niles D, Meaney PA. Aplenc R. French 8.

Abella BS, Lengetti EL, Berg RA, Helfaer MA, Nadkarn)

\V. "Booster" training: evaluation of instructor-led bedside

cardiopulmonary resuscitation skill training end automated

corrective feedback to improve cardiopulmonary resuscita-

tion compliance of Pediatric Basic Life Support providers

‘during simulated cardiac arrest (oublished online ahead

Of print July 8, 2010), Pediatr Crit Care Med. doi10.1097/

PCC.0b013e818 1691271

Systematic Approach to the

Seriously Ill or Injured Child

Overview

‘The PALS provider should use a systematic approach when

Caring fora seriously i or injured child, The purpose of this

crganized approac isto enable you to quickly recognize

signs of respiratory distress, respiratory failure, and shock

and inmediatoly provide lifesaving intorventions. If not

appropriately treated, children with respiratory failure and

shock can quickly develop cardiopuimonayy failure and

even cardiac arest (Figure 1).

Rapid Intervention to Prevent

Cardiac Arrest

In infants and children, most cardiac arrests result from pro-

gressive respiratory failure, shock, or both. Less commonly,

Pediatric cardiac arrests can occur without warning (ie, with

‘sudden collapse) secondary to an arrhythmia (ventricutar

fibrilation (VF or ventricular tachycardia [VT).

‘Once cardiac arest occurs, even with optimal resuscitation

cfforts, the outcome is generally poor. In the out-of-hospital

setting only 4% to 13% of children who experience cardiac

arrest survive to hospital discharge. The outcome is better

{or children who experience carclac arrest in the hospital,

although oniy about 33% of those children survive to hos

pital discharge. For this reason itis important to learn the

concepts prasentod in the PALS Provider Course so that

Rapid, systematic intervention for seriously ill or injured infants and children is Key to

preventing progression to cardiac arrest. Such rapid intervention can save lives.

you can identity signs of respiratory feilure and shock and.

rapidly intervono to prevent progression to cardiac arrest.

Learning Objectives

‘After completing this Part you should be able to

* Discuss the evaluate-identiy-intervene sequence

‘+ Explain the purpose and components of the initial

improssion

'* Describe the ABCDE components of the primary

assessment

* Interpret the clinical findings during the primary

‘assessment

* Evaluate respiratory or circulatory problems by using

the ABCDE mode! in the primary assessment

+ Describe the components of the secondary

assessment

* List diagnostic and laboratory tests used to identify

respiratory and circulatory problems

Preparation for the Course

‘You rieed to know all of the concepts presented in this Part

to be able to identify respiratory or circulatory problems

‘and target appropriate managomont in case simulations.

‘The ongoing process of evaluate-identfy-intervene is a core

‘component of systematic evaluation and care of a seriously

i oF injured child,

Precipitating Problems

Respiratory Circulatory Sudden

Cardiac Arrest

(Arrhythmia)

Figure 1. Pathways to pediatic cardiac arest. Note that respiratory problems may progress to respiratory falure wth or witout signs of resp=

ratory distess, Pespratory failure without respiratory dstiess ozcurs when the chld falls to maintain an open alway oF adoquate respiratory afort

and is typically associated with a decreased Iavelo! consciousness. Sudden cardiac arrestin chieren is less common than in aduls and typically

resus from arhythmias such as VF or VT. Ouring sports activities, sudden cavdlac arest ean occur in children with underlying cardige problems

‘hat may oF may not have bean previously recogrized.

Se een a a oe Red

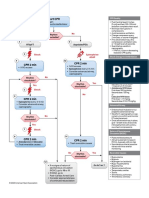

ALS Systematic Approach Algorithm

‘The PALS Systematic Approach Algorithm (Figure 2) outlines the approach to cating for a critically il or injured child.

Initial Impression

‘Activate Emergency Response

18 appropriate for setting)

Goto

Pediatric Cardiac Arrest

Algorithm

‘After ROSC, begin

Evaluate-Identity-Intorvene

‘sequence (right column)

©2011 Amaroan Heat Aosocaton

Figure 2. PA.5 systematic Approach Algor,

If at any time you identify a life-threatening problam, immediately begin appropriate

Interventions. Activate emergency response as indicated in your practice setting,

Initial Impression

The initial impression (Figure 2) is your first quick “trom the

doorway” observation. Ths inital visual and aucitory obser-

provide compressions and ventilations. Proceed

‘according to the Pediatric Cardiac Arrest Algorithm.

1» If the heart rate is 260/min, begin the evaluate-

identity-intervene sequence. Be prepared to inter-

vene according to the Pediatric Cardiac Arrest |

Algorithm if needed, |

« Ifthe child is breathing adequately, proceed with the

evaluate-identify-intervene sequence. If at any time you

identify cardiac arrest, begin CPR and proceed accord-

vation of the chilo's consciousness, breathing, and color is

accomplished within seconds of encountering the child.

ees

Consciousness | Leve! of consciousnoss ing to the Pediatric Cardiac Arrest Algorithm.

(¢9, unresponsive, iritable, alert)

[resting | wreesed wacof treating, coset | Ewaluate-Identify-Intervene

cr decreased respiratory effort, or Use the evaluate-identify-intervene sequence (Figure 3)

‘abnormal sounds heard without | when caring fora seriously il or injured child. This wil helo

auscuttation you to determine the best treatment or intervention at any

———— point. From the information gathered during your evaluation,

Soler ‘Abnormal skin Color, Such a5 yaNO- | identity the child’s problom by type and severity. Intervene

Ss pelos erring with appropriate actions. Then repeat the sequence. This

process is ongoi

‘The level of consciousness may be characterized as unre- ee

sponsive, irtable, or alert. Decreased lavel of conscious-

ness may result from inadequate O, or substrate delivery or

brain trauma/dystunction. Abnormal breathing includes use

‘of accessory muscles, extra sounds of breathing, or abnor-

‘mal breathing patterns. Pale, mottied, or bluish/gray skin

color suggests poor parfusion, poor oxygenation, or both.

A flushed appearance suggests fever or the presence of

atoxin.

Use your intial impression to determine the next best stops:

« If the child is unresponsive and not breathing or only

gesping, shout for help or activate emergency response

{as appropriate for your practice setting). Check to see

if there is a pulse.

~ If there is no pulse, start CPR, beginning with chest

‘compressions. Proceed according to the Pediatric

Cardiac Arrest Algorithm. Alter return of spontane-

us circulation (FOS), begin the evaluate-identify-

intervene sequence.

~ Ifa pulse is present, provide rescue breathing.

‘=f, despite adequate oxygenation and ventilation, the

bear rate is <60/rmin with signs of poor perfusion,

Figure 3. Evaluate-derify- intervene sequence.

Always be alert to a life-threatening problem. if at any point

you identify a life-threatening problem, immediately activate

‘emergency response (or send someone to do so) while you

begin lifesaving interventions.

oa The initial impression used in this version of the PALS Provider Course is a modification

Of the Paciatric Assessment Triangle (PAT) that was used in the 2008 PALS Provider

Course.* The PAT, lke the rapid cardiooulmonary essessment (which was taught in all

Of the PALS courses before 2006),’is part of a systerratic approach to assessing an il

© injured child. These slightly different assessment approaches use many of the same

‘common terms. The goal ofall of these approaches is to help the provider quickly rec-

‘ognize a chi at risk for deterioration and prioritize actions and interventions.

tee

‘Dieckmann RD, Brownstein OR, Gausche-HillM, eds. Pediatric Education fr Prehospta!

Professionals Insttuctor Took. Sudbury. MA: American Academy of Pedi and Jones &

BBarlet Publishers; 2000. ‘Ralston M, Hazinski MF, Zarsky AL, Schexrayder SM, Klerman ME

‘eds, Peclatic Advanced Life Support Provider Manual. Dallas, TX: American Heart Assocation;

12000. Hazinski MF, Zantsky AL, Nadkarni VM, Hickey RW, Schexnayder SM, Berg RA, eds

Pediatric Advanced Life Support Prove Manual. Dalia, TX: American Heatt Asscciaton: 2002.

SC ene Ue ae Rd

Evaluate

It no ife-threatening problem is present, evaluate the child's

condition by using the clinical assessment tools described

below.

re

pinay Cea

Primary A rapid, hands-on ABCDE approach

assessment | to evaluate respiratory, cardiac, and

neurologic function; this step includes

assessment of vital signs and pulse

oximetry

Secondary —_| A focused medical history and a

assessment | focused physical exam.

Diagnostic | Laboratory, radiographic, and other

tests ‘advanced tests that help to identify

the child's physiologic condition and

diagnosis

Note: Providers should be aware of potential environmental

dangers when providing cars. In out-of-hospital settings,

always assess the scane before you evaluate the child.

Identify

Try to identify the type and severty of the chic's problem.

vid Ee

Respiratory | * Uppor airway = Respiratory

obstruction cistress

* Lower airway * Respiratory

obstruction failure

* Lung tissu disease

* Disordered control

of breathing

Circulatory | + Hypovolemic shook

‘+ Compensated

* Distributive shook | shock

*# Cardiogenic shock | * Hypotensive

shock

*# Obstructive shock

Cardiopulmonary Failure

Cardiac Arrost

The child's ciinical condition can result rom a combination

of respiratory and circulatory problems. As a seriously il or

injured child deteriorates, one problem may lead to others.

eka Ty

ROS Ca Le * Alter each intervention

Intervene Sequence Is

erates

Note that in the initial phase of your identification you may

bbe uncertain about the type or soverty of problems.

Identifying the problem will help you determine the best

initial interventions. Recognition and management are dis

cussed in deal later in this manual,

Intervene

(On the basis of your identiication of the child's problem,

intervene with appropriate actions within your scope of

practice. PALS interventions may include

‘ Positioning the child to maintain a patent airway

‘* Activating emergency response

* Staring CPR

+ Obtaining the code cart and monitor

+ Placing the child on a cardiac monitor and pulse

oximeter

«= Administering O.

‘Supporting ventilation

* Starting medications and fluids (eg, nebulizer

treatment, IV/1O fuuid bolus)

Continuous Sequence

The sequence of evaluate-identily-intervene continues

Until the chid is stable. Use this sequence belore and atter

each intervention to lack for trencs in the child's condktion.

For example, after you give O., reevaluate the chid. is the

CChid breathing a lite easier? Ave color end mental status

improving? After you give a flid bolus to a child in hypo-

volemic shock, do heart rate and perfusion improve? Is.

‘another bolus neadec? Use the evaluate-identily.intervene

‘sequence vibenever the child's condition changes.

Determine If Problem Is Life

Threatening

‘On the basis of the initial impression and throughout care,

determine ifthe child's problem is

«Lite threatering

* Not life threatening

Life-threatening probleme include absent or agorsal res

pirations, respiratory distress, cyanosis, or decreased

level of consciousness (see the section “Lite-Threatenng

Problems" later inthis Part). If the problem is life threaten-

ing, immediately begin appropriate interventions. Activate

‘emergency response as indicated in your practice setting

It the problem ss not if threatening, continue with the sys-

tematic approach.

Remember to repeat the evaluate-identify-intervene soquence until the child is stable

+ When ihe child's concition changes or deteriorates

a ‘Sometimes a child's condition may saem stable despite the presence of a lfe-threat-

ening problem, An example is @ child who has ingested a toxin but is not yet snowing

effects, Another example is a trauma victim with internal bleeding who may initially

mainiain blood pressure by increasing heart rate and systemic vascular resistance (SVF).

eee

Retry

Ie Ou cu)

Primary Assessment

A B

E c

D

‘The primary assessment uses an ABCDE model:

+ Ainway

+ Broathing

* Circulation

+ Disability

+ Exposure

‘The primary 2esessment is a hands-on evaluation of

respiratory, cardiac, and neurologic function. This assoss-

‘ment includes evaluation of vital signs and O, saturation by

pulse oximetry.

Airway

When you assess the ainay, you determine if it is patent

(open). To assess upper airway patency:

* Look for movement of the chest or abdomen

* Listen for air movement and breath sounds

Decide if the upper airway is clear, maintainable, or not

‘maintainable as described in the following table:

pe

Clear Airway is open and unobstructed for

normal breathing

Maintainable | Airway |s obstructed but can be main-

tained by simple measures (eg, head

tilt-chin It)

Not Airway is obstructed and cannot be

maintainable | maintained without advanced interven-

tions (eg, intubation)

‘The following signs suggest that the upper airway is

obstructed:

+ Increased inspiratory effort with retractions

‘+ Abnormal inspiratory sounds (snoring or high-pitched

stridor)

+ Episodes where no airway or breath sounds are pres-

‘ent despite respiratory effort (le, complete upper airway

obstruction)

If the upper airway ie obstructed, determine if you can open

land maintain the airway with simple measures or if you

need advanced interventions.

‘Simple measures to open and maintain a patent upper air-

way may include one or more of the following:

+ Allow the child to assume a position of comfort or posi-

ton the child to improve airway patency.

+ Use nead tit-chin lft or jaw thrust to open the airway.

~ Use the head tit-chin lft maneuver to open the a

‘way unless you suspect cervical spine injury. Avoid

overextending the head/neck in infants because ths

may ecclude the airway.

~ Hf you suspect cervical spine injury (eg, the chi has

head or neck injury), open the away by using a jaw

‘thrust without neck extension. If this maneuver does.

not open the airway, use a head tit-chin lift or jaw

‘trust with neck extension because opening the ai.

\way is a prio. During CPR stabilize the head and

neck manually rather than with immobikzation devicos.

I at any time you identity a life-threatening problem, immediately begin appropriate

interventions. Activate emergency response as indicated in your practice setting

— Note that the jaw thrust may be used in children

without trauma as vrell,

‘Avoid overextending the head/neck in infants because

this may occlude the airway. Suction the nose and

‘oropharynx.

Perform foreign-bedy airway obstruction (FBAO) relief

techniques if you suspect that the child has aspirated

a foreign body, has complete airway obstruction ($

tunable to make any sound), and is stil responsive,

Repeat the folowing es needed:

~ <1 year of age: Give 5 back slaps and 5 chest

thrusts

= 21 year of aga: Give abdominal thrusts

Use airway adjuncts (eg, nasopharyngeal airway [NPA]

or oropharyngeal airway [OPA)) to keep the tongue

{rom falling back and obstructing the airway.

Advanced Interventions

Advanced interventions to maintain airway patency may

include one or more of the following:

‘+ Encotracheal intubation or placement of a laryngeal

mask airway

‘+ Application of continuous positive airway pressure

(CPAP) or noninvasive ventilation

‘+ Removal ofa foreion body: this intervention may

requite drect laryngoscopy (ie, visualizing the larynx

with a laryngoscope)

* Cricothyrotomy (a needle puncture or surgical opening

through the skin and criecthyroid membrane and into’

the trachea below the vocal cords)

Breathing

Assessment of breathing includes evaluation of

* Respiratory rate

* Respiratory effort

* Chest expansion and air movement

Cred

DOO CAC

Cee ie

el

‘An airway adjunct will help to maintain an open airway, but you may stil need to use a

head tit-chin lift. Don't rely only on an adjunct alone, Assees the pati

Acconsistent respiratory rate of less than 10 or more than 60 breaths/min in a child of

any age is abnormal and suggests the presence of a potentially serious problem.

SS ee RGR ae Ee eked

* Lung and airway sounds

‘+ 0, saturation by pulee oximetry

Normal Respiratory Rate

Normal spontaneous breathing is accomplished with mini

‘mal work, resulting in quiot breathing with unlabored inspi-

ration and passive expiration. The normal respiratory rate

Inversely related to age (see Tabie 1); it is rapid in the neo-

ate and decreases as the chiki gets older.

Table 4. Normal Respiratory Rates by Age

oS Breaths/min

[event et yoo) 01080

Toddler (1 to 3 years) 24 to 40

Preschooler (4 to 5 years) 221034

School age (6 to 12 years) 180.90

| Adolescent (13 to 18 years) 121016

Respiratory rate is often best evaluated before your hands-

on assessment bacause anxiaty and agitation commonly

alter the baseline rata. Ifthe child has any condition that

causes an increase in metabolic demand (eg, excitement,

anxiety, exercise, pain, or fever), itis appropriate for the

respiratory rate to be higher than normal.

Determine the respiratory rate by counting the number of

times the chest rises in 30 seconds and multiplying by 2.

Be aware that normal sleeping intents may have irregular

(periodic) breathing with pauses lasting up to 10 or even

16 seconds. If you count the number of times the chest

rises for <30 seconds, you may estimate the respiratory

rate inaccurately. Count the respiratory rate several timas

‘as you assess and reassess the child to detect changes.

Alternatively, the respiratory rate may be displayed continu-

‘ously on a monitor.

A decrease in respiratory rate from 2 rapid to a more

“normal” rate may indicate overall improvement if itis

associated with an improved level of consciousness and

reduced signe of air hunger and work of breathing. A

decreasing or irregular respiratory rate in a chid with a

deteriorating level of consciousness, however, often indi

cates a worsening of the child's clinical condition.

Abnormal Respiratory Rate

‘Abnormal respiratory rates are classified as

+ Techypnea

+ Bradypnea

+ Apnea

Tachypnea

Tachypnea is a breathing rate that is more rapi than nor-

‘mal for age. It is often the first sign of respiratory distress in

Infants. Tachypnea also can be a physiologic (appropriate)

response to stress.

Tachypnea with respiratory distress is, by definition, associ

ated with other signs of increased respiratory effort. “Quiet

tachypnea” is the term used if tachypnea is present without

signs of increased respratory effort (e, without respiratory

distress). This often results from an attempt to maintain

near-normal blood pH by increasing the amount of air mov-

ing in and out of the lungs (ventilation) this decreases GO.

leve's in the blood and increases biood pH.

Quiet tachypnea commonly results from nonpulmonary

problems, including

* High fever

» Pan

‘+ Mild metabolic acidosis associated with dehydration or

diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA)

‘+ Sopsis (without pnaumonia)

* Congestive heart failure (early)

* Severe anemia

* Some cyanotic congenital heart defects (eg. transposi-

tion of the great arteries)

eee

See aa cd

Rega eel

Signals Impending Arrest

a7

resent:

eee ae

apnea

Bradypnea cr an irregular respiratory rate in an acutely il infant or chile is an ominous,

clinical sign and often signals impending arrest. |

‘Apnea is classified into 3 types, depending on whether inspiratory muscle activity

* In central apnea there is no respiratory effort because of an abnormality or sup

pression of the brain or spinal cord,

® In obstructive apnea there is inspiratory eftort without airflow (ie, airflow is partially

‘or completely blocked).

‘= In mtxed apnea there are poriods of obstructive apnea and periods of contral

for age, Frequontly the breathing is both slow and iregu-

lar, Possible causas are respiratory muscle fatigue. central

‘nervous system injury or infection, hypothermia, or medica-

tions that depress respiratory drive. |

Apnea

‘Apnea is the cessation of breathing for 20 seconds or ces-

sation for less than 20 seconds i accompanied by brady-

cardia, cyanosis, or pallor.

Bradypnea

Bradypnea is a breathing rate that is slower than normal

‘Agonal gasps are common in adults after sudden cerdiac

arrest and may be confused with normal breathing. Agonal

‘gasps will not produce effective oxygenation and ventilation.

Respiratory Effort

Increased respiratory effort results from conditions that

increase resistance to airflow (eg, asthma or bronchiclitis)

cr that cause the lungs to be stiffer and difficult to inflate

(e9, pnoumoria, pulmonary edema, or pleural effusion)

Nonpulmonary conditions that result in severe metabolic

acidosis (€g, DKA, sabcylate ingestion, indorn errors of

metabolism) can also cause increased respiratory rate

and effort. Signs of increased respiratory effort retlect the

child's attempt to improve oxygenation, ventilation, or both,

Use the presence or absence of these signs to assess the

severity of the condition and the urgency for intervention.

Signs of increased respiratory effort include

‘= Nasal flaring

‘+ Retractions

‘+ Head bobbing or seesaw respirations

thor signs of increased respiratory effort are prolonged

inspiratory or expiratory times, open-mouth breathing,

‘gasping, and use of accessory muscles. Grunting Is a serl-

‘ous sign and may indicate respiratory distress or respiratory

failure, (See “Grunting” later inthis Part.)

‘Systematic Approach to the Seriously Ill or Injured Child

Nasal Flaring (continued)

‘Nasal faring is dation of the nostri with each inhalation, Pe cc

‘The nostris open more widely to maximize airflow. Nasal Cre aed

flaring is most commonly observed in infants and younger

chilcron and is usually a sign of respiratory distress.

Severe (may | Supraciavicular | Retraction in the

include the ‘neck, ust above the

Retractions same retrac- collarbone

Retractions ere inward movements of the chest wallortis- | tlorsasseen [sr atermal | Retraction in the

sues, neck, oF sternum ding inspiration. Chest retractions | With mil chest, just above

are a sign that the child is trying to move air tothe turgs | tomoder- the breastbone

by using the chest muscies, but air movement is impaired ate breathing

by increased airway resistance or stif lungs. Retractions aiticury) Sternat Retraction of the

‘may occur in several areas of tho chest. The severity of the ctor foward

the spine

retractions generally corresponds with the severity of the

child's breathing difficuty.

Head Bobbing or Seesaw Respirations

“The following table describes the location of retractions Head bobbing and seesaw respirations often indicate that

‘commonly associated with each level of breathing difficulty: the child has increased risk for deterioration

+ Heed bobbing is caused by tho uso of neck muscles

Ca eee

pete (rete to assist breathing. The child lits he chin and extencs

the neck during inspiration and allows the chin to fal

‘Subcostal Ratraction of the forward during expiration. Head bobbing is most tre= |

abdomen. just quently seen in infants and can be @ sign of respiratory

Delow the rib cage falure |

+ Seesaw respirations are present when the chest |

Substernal_ | Retraction of the retracts and the abdomen expands during inspiration.

abdomen at the During expiration the movement reverses: the chest

bottom of the ‘expands and the abdomen moves inward. Soesaw

respirations usvally indicate upper airway obstruction,

Pression: They also may be observed in severe lower airway

intercostal | Retraction betweon obstruction, lung tissue disease, and disordered control

the rbe | Of breathing, Seesaw respirations are characteristic

al J Of infants and children with neuromuscular weakness.

(continued) Tis inefficient form of ventlation can cuiekly lead to

fatigue.

a etvactions accompanied by stridor or an inspiratory snoring sound suggest upper

ih airway obstruction. Retractions accompanied by expratory weezing suggest marked

ans ower airway obstruction (asthma or bronchiolitis), causing obstruction during both

Renee USE Reus

RPO cu ala

Peer ego

inspiration and expiration, Retractions accompanied by grunting or labored respira-

tions suggest lung tissue disease. Severe retractions also may be accompanied by

head bobbing or seesaw respirations,

The cause of seesaw breathing in mest children with neuromuscular disease is weak~

ness of the abdominal and chest wall muscles. Seesaw breathing Is caused by stiong

contraction of the diaphragm that dominates the weaker abdominal and chest wall

muscles. The result is retraction of the chest and expansion of the abdomen during

inspiration.

oe td

Eee

eee)

Chest Expansion and Air Movement

Evaluate magnitude of chest wall expansion and air move~

ment to assess adequacy of the chile’s tidal volume. Tidal

volume is the volume of air inspired with each breath,

Normal tidal volume is approximately 5 to 7 mL/kg of body

weight and remains fairy constant throughout Ife, Tidal

volume is difficult to measure unless a child is mechanically

ventilated, so your clinical assessment is very important,

Chest Wall Expansion

Chest expansion (chest rige) during inspiration should be

symmetric. Expansion may be subtle during spontane

‘ous quiet breathing, especially when clothing covers the

chest. But chest expansion should be readily visible when

the chest is uncovered. In normal infants the abdomen

‘may move moro than the chest. Decreased or asymmetric

cchest expansion may result from inadequate effort, ainway

obstruction, atelectasis, pneumothorax, hemothorax, pleu-

ral effusion, mucous plug, or foreign-body aspiration,

Air Movement

‘Auscuttation for air movement is critical. Listen for the

intensity of breath sounds and quality of air movement,

Particularly in the cistal lung fields. To evaluate distal ar

entry, Isten below both axillao. Because these areas are

farthest from the larger conducting airways, upper airway

Sounds are less likely to be transmitted. Typical inspiratory

‘sounds can be heard distally as soft, quiet noises ocour-

ring simultaneously with observed inspiratory effort. Normal

‘expiratory breath sounds are often short and quiets.

‘Sometimes you may not hear normal expiratory

breath sounds.

You should also auscuitate for lung and airway sounds

ver the anterior and posterior chest. Because the chest is

small and the chest wall is thin in infants or children, breath

‘sounds are readily transmittad from one side of the chest to

tne other, Breath sounds also may be transmitted from the

upper airway.

Decreased chest excursion or decreased air movement

observed during auscultation often accompanies poor

+ Stow respiratory rate

*+ Small tical volume (ie, shallow breathing, high airway resistance, stft lungs)

+ Extremely rapid respiratory rate i tidal volumes are very small)

Minute ventilation is the volume of air that moves into or out of the lungs each minute,

{tis the product of the number of breaths per minute (respiratory rate) and the volume

of each breath (ida! volume)

Minute Ventilation = Respiratory Rate x Tidal Volume

Low minute ventilation (hypoventilation) may result from

respiratory effort. In tho child with apparently normel or

increased respiratory effort, diminished distal air entry

‘Suggests airflow obstruction or lung tissue disease. If the

child's work of breathing and coughing suggest lower al-

way obstruction but no wheezes are heard, the amount and

rate of airflow may bo insufficient to cause wheezing,

Distal ir entry may be dificult to hear in the obese child.

As a result, it may be difficult to identify significant airway

abnormalities in this population

Lung and Airway Sounds

During the primary assessment, listen for lung and airway

sounds. Abnormal sounds include stridor, grunting, gur-

gling, wheezing, and crackles.

Stridor

Strider is a coarse, usually higher-pitched breathing sound

typically heard on inspiration. It also may be heard during

both inspiration and expiration. Stridor is a sign of upper

airway (extrathoracic) obstruction and may indicate that the

obstruction is critical and requires immediate intervention.

‘Thote ave many causes of stridor, such @s FBAO and infec

tion (eg, croup). Congenital airway abnormalities (eg, laryn-

omaiacia) and acquired airway abnormalities (2g, tumor

Cr cySt) also can cause stridor. Upper airway edema (eg,

allergic reaction or swelling after a medical procedure) is

‘another cause ofthis abnormal breathing sound.

Grunting

Granting is typically a short, low-pitched sound heard

uring expiration. Sometimes it can be misinterpreted as

a soft ory, Grunting occurs as the child exhales against a

partialy closed glottis. Although grunting may accompany

the response to pain or fever, infants and children often

grunt to help keep the small aways and alveolar sacs in

the lungs open. This is an attempt to optimize oxygenation

and ventilation,

Grunting is often a sign of lung tissue disease resuting

from smal airway collapse, alveolar collapse, or both.

Grunting may indicate progression of respiratory distress to

uel eon ni na Rem a Rel]

Grunting is typically a sign of severe respiratory distress or failure from jung tissue

disease. Identity and treat the cause as quickly as possible. Be prepared to quickly

intervene If the chila's condition worsens.

respiratory failure. Pulmonary conditions that cause grunt

ing include pneumonia, pulmonary contusion, and acute

respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). It may he caused by

‘cardiac conditions. such as congestive heart faiure, that

result in pulmonary edema. Grunting may be a sign of pain

resulting from abdominal pathology (eg, bowel obstruction,

porforated viscus, appendicitis, or peritonitis).

Gurgling

Gurgling is a bubbing sound heard during inspiration or

‘expiration. It results from upper airway obstruction due to

airway secretions, vomit, or blood.

Wheezing

Wheezing is a high-pitched or low-pitched whistling or sigh:

ing sound heard most often during expration. itis heard

less frequently during inspiration. This sound typically ind-

cates lower (intrathoracic) airway obstruction, especially of

the emaller aways. Common causes of wheezing aro bron:

chioitis and asthma. Isolated inspiratory wheezing suggasts

‘a foreign body or other cause of partial obstruction of the

trachea or upper airway.

Crackles

Grackies, also known as rales, are sharp, crackling inspira-

tory sounds. The sound of dry crackles can be described

as the sound made when you rub several hairs together

close to your ear. Crackles may be described as moist or

dry. Moist crackles indicate accumulation of alveolar fluid,

‘They are typically associated with lung tissue disease

(eg, pneumonia and pulmonary edema) or interstitial lang

ured

OME Ty

disease. Dry crackles are more often heard with alelectasis

(smal airway collapse) and interstitial lung disease. Noto

that you may not hear crackles despite the presence of

pulmonary edema,

Oxygen Saturation by Pulse Oximetry

Pulse oximetry is a tool to monitor the percentage of the

child's hemogiobin that is saturated with O, (Spo). The

pulse oximeter consists of a probe Inked to a monitor.

The probe is attached to the child's finger, toe, or earlobe.

The unit displays the calculated percentage of oxygenated

hemoglobin. Most units make an audiole sound for each

pulse beat and display the heart rate. Some models display

the quality of the pulse signal as a waveform or with bars.

Pulse oximetry can indicate low ©, saturation (hypoxemia)

before it causes cyanosis or bradycardia. Providers can

use pulse oximetry to monitor trends in O, saturation in

response to treatment. If avaiable, contiruously monitor

pulse oximetry fora child in respiratory distress or faire

during stabiization, transport, and postresuscitation care.

Caution in Interpreting Pulse Oximetry Readings

Be careful to interpret pulse oximetry readings in conjunc-

tion with your cinical assessment and other signs, such as

respiratory rate, respiratory effort, and level of conscious-

ness. A child may be In respiratory distress yet maintain

normal O, Saturation by increasing respiratory rate and

effort, especially if supplementary ©, is administered. H the

heart rate displayed by the pulse oximeter is not the same

as the heart rate determined by ECG monitoring, the O,

‘The O, saturation is the percent of {otal hemogiobin that is saturated with O,.

“This saturation dove not indicate the amount of O, delivered to the tissues. O, delivery

is the product of artarial O, content (oxygen bound to hemoglobin plus dissolved 0.)

and cardiac output.

{tis also Important to note that O; saturation does not provide information about effec-

tiveness of ventilation (CO, elimination).

‘An O, saturation (Spo,) 284% while @ child is breathing room air usually indicates that |

‘oxygenation is adequate. Consider administration of supplementary O» if the Op satu-

ration is below this value in a ori

ly ill or injured child. An Spo; of <90% in a child

receiving 100% O, is usually an indication for additional intervention.

‘saturation reading is not reliable. When the pulse oximeter

dows not detect a consistent pulse or there is an irregular

‘or poor waveform, the child may have poor distal pertusion

‘and the pulse oximeter reading may not be accuraie—check

the child and intervene as needed. The pulse oximeter may

rot be accurate if the child develops severe shock and

‘won't be accurate during cardiac arrest. As noted above,

pulse oximetry only indicates O; saturation and does not

indicate O, delivery. For example, if the child is profoundly

anemic (hemoglobin is very low), the saturation may be

100%, but ©, content in the blood and O, delivery may be

low.

The pulse oximeter does not accurately recognize met-

hemoglobin or cartvoxynemogiobin (hemoglobin bound

to carbon monoxide). If carboxyhemoglobin (from carbon

‘monoxide poisoning) is prosont, the pulco oximeter will

reflect a falsely high O, saturation. if methemoglobin con-

centrations are above 5%. the puise oximeter will read

approximately 85% regardless of the degree of methemo-

globinemia, If you suspect etther of these conditions, obtain

2 blood gas with O, saturation measurement by using a

co-oximeter.

Circulation

c

Circulation is assessed by the evaluation of

* Heart rate and rhythm

* Pulses (both peripheral anc central)

* Capitary rel time

* Skin color and temperature

+ Blood pressure

Unne output and level of consciousness also reflect

adequacy of circulation. See the Fundamental Fact box

“Assessment of Urine Output” at the end of this section,

For more information on assessing level of consciousness,

‘see the section “Disability” later in this Par.

Heart Rate and Rhythm

‘To determine heart rate, check the pulse rata, listen to the

heart, or view a monitor display of the electrocardiogram

(ECG) or pulse oximeter wavelorm. The heart rate should

‘be appropriate for the child’s age, level of activity, and clini-

cal condition (Table 2). Note that there is a wide range for

normal heart rates. For example, a child who is sleeping

‘or is athletic may have a heart rate lower than the normal

range for age.

‘Table 2. Normal Heart Rates (por Minute) by Age |

Awake Sr)

es Go ior Rate

Nowborn to | 8510205 | 140 | ato 160

months

months te2 | 1000190 | 130 | 75t0 160

years

2yearsto10 | Bto140 | 89 | 60t0.90

years |

>iyears | 6010100 | 75 | S0t090

Modifed tron Gilette PC, Garson A J, Craword F Ross B, Ziegler

V, Bucklos D. Dysthythmias. I: Adams FH, Emmanouiides GC,

Fimenschneider TA, eds. Moss’ Hear Dissese in arts, Crilcren, ana

Adolosconts 4th ed, Batimore, MD: Willams & Wiking; 1980:026-020,

‘The heart rhythm is typically regular with only small flic-

tuations in rate. When checking the heart rate, assess

for abnormalities in the monitored ECG. Cardiac rhythm

disturbances (arrhythmias) result from abnormalities in, or

incults to, the cardiac conduction system or heart tissue,

Arrhythmias also can result from shock ar hypoxia. In the

advanced life support setting, an arthythmia in a child can,

be broadly classified according to the observed heart rate

or effect on perfusion:

Coun Ceo

Slow Bradycardia

Fast Tachycardia

Absent Cardiac arrest

Bradycardia is a heart rate slower than normal for a child's

‘age. Slight bradycardia may be normal in athletic children,

uta very siow rate in a child with other symptoms is @

worrisome sign and may indicate that cardiac arrest is

imminent. Hypoxia is the most common cause of brady-

cardia in chilcren. Ifa child with bradycardia has signs of

oor partusion (decreasad responsiveness, weak peripheral

ulses, cool mottled skin), immediately support ventitation

with a bag end mask and administer supplementary O.. If

the chi with bradycercia is alert and has no signs of poor

perfusion, consider other causes of a siow heart rate, such

as heart biock or drug overdose.

Tachycardia is a resting heart rate that is faster than the

normal range for a child's age. Sinus tachycardia is a com-

‘mon, nonspecific response to a variaty of conditions. Itis

often appropriate when the child is seriously ill oF injured. To.

determine if the tachycardia is a sinus tachycardia or rep-

resents a cardiac rhythm disturbance, evaluate the child's,

history, clinical condition, and ECG.

Systematic Approach to the Seriously Ill or Injured Child

Consider the following when evaluating the heart rate and rhythm in any seriously il or

injured chité:

eae

eu cca cy

es ‘+ The child's typical heart rate and baseline rhythm

*+ The child's level of activity and clinical condition (including baseline cardiac

function)

Children with congenital heart disease may have conduction abnormalities. Consider

the child's baseline ECG when interpreting heart rate and rhythm. Chicren with poor

cardiac function are more likely to be symptomatic from arrhythmias than are children

with good cardiac function,

In healthy children the heart rate may fluctuate with the respiratory cycle, increas-

ing with inspiration and siowing down with expiration. This condition is called sinus

arrhythmia. Note if the child hs an irregular rhythm that is not related to breathing. An

iregular rhythm may indicate an underlying rhythm cisturbance, such as premature

ventricular or atrial contractions or an atrioventricular (AV) block

Fundamental Fact

Relationship of

eae Rca

Cy

For more information, see Part 8: “Recognition and

Management of Bradycardia,” Part 9: “Recognition and

Management of Tachycardia,” and Part 10: "Recognition,

‘and Management of Cardiac Arrest.”

Evaluation of pulses is critica to the assessment of sys-

temic perfusion in an ill or injured child. Palpate both cen-

tral and peripheral pulses. Central pulses are ordinarily

stronger than peripheral pulses because they are present

in vessels of larger size that are located closer to the heart.

Exeggeration of the difference in quality between central

land peripheral pulses occurs when peripheral vasocon-

striction is associated with shook. The following pulses ere

easily palpable in healthy infants and children (unless the

Child is Cbese or the ambient temperature is Cold)

Central Pulses

+ Femoral

* Brachial (in infants)

* Carotid (in older children)

+ Axillary

© Racial

* Dorsalis pedis

+ Posterior tibia)

heat

‘Weak central pulses are worrisome and indicate the need

for very rapid intervention to prevent cardiac arrest.

beat-to-beat fluctuation in pulse volume may occur in

children with arrhythmias (eg, premature atrial or ventricular

Contractions}. Fluctuation in pulse volume with the respira-

tory cycle (pulsus paradoxus) can occur in children with