Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Simile of The Cave

Uploaded by

BERMUNDOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Simile of The Cave

Uploaded by

BERMUNDCopyright:

Available Formats

This leads up to the famous simile of the cave or den.

According to which, those who are destitute of

philosophy may be compared to prisoners in a cave who are only able to look in one direction because

they are bound and who have the fire behind them and the wall in front. Between them and the wall,

there is nothing; all that they see are shadows of themselves and of objects behind them casted on the

wall by the light of the fire. Inevitably, they regard these shadows as real and have no notion of the

objects to which they are due. (Prince 2000). At last, a man succeeds in escaping from the cave to the

light of the sun; for the first time, he sees real things, and becomes aware that he had hitherto been

deceived by shadows. He is the sort of philosopher who is fit to become a guardian; he will fell it is his

duty to those who were formerly his fellow prisoners to go down again into the cave, instruct them as to

the sun of truth and show them the way up.

However, he will have difficulty in persuading them, because coming out of the sunlight, he will see

shadows clearly than they do and will seem to them stupider than before his escape.

Plato seeks to explain the difference between clear intellectual vision and the confused vision of sense

perception by an analogy from the sense of sight. Sight, he says, differs from the other senses, since it

requires not only the eye and the object, but also light. We clearly see objects on which the sun shines;

in twilight, we see confusedly; and in pitch-darkness, not at all. Now the world of ideas is what we see

when the sun illumines the object; while the world of passing things is a confused twilight world. The

eye is compared to the soul, and the sun, as the source of light to truth or goodness. (Mitchell 2011)

You might also like

- DLL For Contemporary Philippine Arts From The RegionDocument3 pagesDLL For Contemporary Philippine Arts From The RegionMIMOYOU79% (63)

- BEEA HandbookDocument20 pagesBEEA HandbookLeopold Laset100% (1)

- Activity Sheets DISSDocument10 pagesActivity Sheets DISSKath Tan Alcantara74% (34)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Plato - Allegory of The CaveDocument6 pagesPlato - Allegory of The CaveNhat Minh67% (3)

- CHED Scholarship Application Form 2020Document1 pageCHED Scholarship Application Form 2020PRC Board84% (429)

- CHED Scholarship Application Form 2020Document1 pageCHED Scholarship Application Form 2020PRC Board84% (429)

- Basic Education Exit Assessment (BEEA) For Grade 12Document20 pagesBasic Education Exit Assessment (BEEA) For Grade 12BERMUND100% (1)

- 11 Intro To Philo As v1.0Document21 pages11 Intro To Philo As v1.0jerielseguido-187% (15)

- Plato Theory of IdeasDocument2 pagesPlato Theory of IdeasTorica NorayNo ratings yet

- Plato Theory of IdeasDocument2 pagesPlato Theory of IdeasTorica NorayNo ratings yet

- Document 4Document4 pagesDocument 4tanvir.iu.iceNo ratings yet

- Plato'S Allegory of The Cave ScriptDocument1 pagePlato'S Allegory of The Cave Scriptlayag classNo ratings yet

- Human Beings: (Glaucon:) I SeeDocument6 pagesHuman Beings: (Glaucon:) I SeeJean Chel Perez JavierNo ratings yet

- Human Beings: (Glaucon:) I SeeDocument6 pagesHuman Beings: (Glaucon:) I SeeJean Chel Perez JavierNo ratings yet

- Allegory of The Cave and Idols of The MindDocument8 pagesAllegory of The Cave and Idols of The MindNosaj Ozidlareg100% (2)

- Diagram Representing The Allegory of The CaveDocument1 pageDiagram Representing The Allegory of The CaveAnonymous VTyRp43jNo ratings yet

- IV The Problem of Reality: IV.1 Am I A Prisoner in A Cave?Document12 pagesIV The Problem of Reality: IV.1 Am I A Prisoner in A Cave?Javier Hernández IglesiasNo ratings yet

- Allegory of The CaveDocument2 pagesAllegory of The CaveCarlos TuazonNo ratings yet

- By What Values Shall I Live in The WorldDocument1 pageBy What Values Shall I Live in The WorldErose0% (1)

- From Darkness to Light: Getting out of Plato’s Cave and Becoming ConsciousFrom EverandFrom Darkness to Light: Getting out of Plato’s Cave and Becoming ConsciousNo ratings yet

- Script For My AssignmentDocument2 pagesScript For My AssignmentKarylle Mish GellicaNo ratings yet

- Allegory of The CaveDocument6 pagesAllegory of The CaveGnosticLuciferNo ratings yet

- Allegory of CaveDocument18 pagesAllegory of CaveShaira DelmonteNo ratings yet

- Allegory of The Cave - WikipediaDocument48 pagesAllegory of The Cave - WikipediaJeary RoxaNo ratings yet

- The Allegory of The Cave Setting The Scene: The Cave and The Fire The CaveDocument6 pagesThe Allegory of The Cave Setting The Scene: The Cave and The Fire The CaveGeorge TumbaliNo ratings yet

- Allegory of The Cave - WikipediaDocument45 pagesAllegory of The Cave - WikipediaJoseph Daniel MoungangNo ratings yet

- Reflection PaperDocument1 pageReflection PaperChristine SaliganNo ratings yet

- Allegory of The Cave ThesisDocument4 pagesAllegory of The Cave Thesisdebrapereaalbuquerque100% (2)

- Allegory of The Cave - WikipediaDocument47 pagesAllegory of The Cave - Wikipediaskand100% (1)

- Plato's Allegory of The CaveDocument2 pagesPlato's Allegory of The CaveAubdool IntiazNo ratings yet

- The Cave ExplainedDocument2 pagesThe Cave Explainedapi-258902544No ratings yet

- Plato The Allegory of The CaveDocument6 pagesPlato The Allegory of The CaveLance David TanNo ratings yet

- Book VII of The Republic by PlatoDocument5 pagesBook VII of The Republic by PlatoKiarana FleischerNo ratings yet

- Allegory of The CaveDocument4 pagesAllegory of The CaveAmi TyNo ratings yet

- Description of The Cave: PlatoDocument16 pagesDescription of The Cave: PlatoMark DanielNo ratings yet

- RepublicDocument10 pagesRepublicghada kamalNo ratings yet

- Plato's Allegory of The CaveDocument5 pagesPlato's Allegory of The CaveMarianne NolascoNo ratings yet

- Book VII of The RepublicDocument4 pagesBook VII of The RepublicJames Lee JuniorNo ratings yet

- Plato's CaveDocument1 pagePlato's CaveKc GraceNo ratings yet

- Allegory of The Cave AnalysisDocument4 pagesAllegory of The Cave AnalysismimNo ratings yet

- Yes, He Said.: That Is CertainDocument4 pagesYes, He Said.: That Is Certainمدرس اختبار ارامكوNo ratings yet

- Plato's Philosophy of RealityDocument2 pagesPlato's Philosophy of RealityMian Umair NaqshNo ratings yet

- Plato - Meaning of The Allegory of The CaveDocument4 pagesPlato - Meaning of The Allegory of The CaveelsonNo ratings yet

- Allegory of CaveDocument1 pageAllegory of CaveTondonba ElangbamNo ratings yet

- WORLD I - Plato, AristotleDocument13 pagesWORLD I - Plato, AristotleizhelNo ratings yet

- An Allegorical Writing Is The Type of Writing Having Two Levels of MeaningsDocument2 pagesAn Allegorical Writing Is The Type of Writing Having Two Levels of Meaningsnamo5No ratings yet

- The Allegory of The CaveDocument5 pagesThe Allegory of The CaveAli HarrietaNo ratings yet

- Tale of A Dramatic Exit From The Cave Is The Source of True UnderstandingDocument2 pagesTale of A Dramatic Exit From The Cave Is The Source of True UnderstandingIldjohn CarrilloNo ratings yet

- The Allegory of The CaveDocument11 pagesThe Allegory of The Caveenoc4444No ratings yet

- Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange As An Illusion To Plato's Mimetic ImaginationDocument12 pagesStanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange As An Illusion To Plato's Mimetic ImaginationMike WangenNo ratings yet

- Plato Republic 7Document6 pagesPlato Republic 7johnNo ratings yet

- Christmas in The MatrixDocument14 pagesChristmas in The MatrixHugh CumminsNo ratings yet

- Plato - Allegory of The CaveDocument3 pagesPlato - Allegory of The Caverourk512No ratings yet

- Lauren Zero Textual DraftDocument5 pagesLauren Zero Textual Draftapi-252395413No ratings yet

- Tale of A Dramatic Exit From The Cave Is The Source of True UnderstandingDocument3 pagesTale of A Dramatic Exit From The Cave Is The Source of True UnderstandingIldjohn CarrilloNo ratings yet

- Allegory of The Cave - PlatoDocument2 pagesAllegory of The Cave - PlatoCésar Guillermo Cruz RomeroNo ratings yet

- Plato's Allegory of The Cave - Alex Gendler - mp4Document2 pagesPlato's Allegory of The Cave - Alex Gendler - mp4jhazNo ratings yet

- Emergence of The Social Sciences: Part 1Document17 pagesEmergence of The Social Sciences: Part 1kristofferNo ratings yet

- New PlatoDocument4 pagesNew PlatoJGNo ratings yet

- Allegory of The CaveDocument5 pagesAllegory of The CaveMikiNo ratings yet

- Book ViiDocument4 pagesBook ViiDouaa KhairNo ratings yet

- Alegory of The CaveDocument4 pagesAlegory of The CaveBen LotsteinNo ratings yet

- Plato, ÆDocument22 pagesPlato, ÆLeah Sobremonte BalbadaNo ratings yet

- Plato's CaveDocument4 pagesPlato's CaveDockuNo ratings yet

- Book VII of The RepublicDocument4 pagesBook VII of The RepublicYK1988No ratings yet

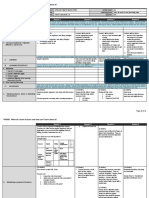

- Print MeDocument7 pagesPrint MeBERMUNDNo ratings yet

- Work Immersion Implementation Plan: Humanities and Social Sciences (HUMSS)Document2 pagesWork Immersion Implementation Plan: Humanities and Social Sciences (HUMSS)BERMUNDNo ratings yet

- TG Doing PhilosophyDocument3 pagesTG Doing PhilosophyBERMUNDNo ratings yet

- Reflection Matthew 9 Verses 18 To 26Document1 pageReflection Matthew 9 Verses 18 To 26BERMUNDNo ratings yet

- Your Certificate of CompletionDocument1 pageYour Certificate of CompletionBERMUNDNo ratings yet

- Flight, Collection, Band, Bouquet, FlockDocument2 pagesFlight, Collection, Band, Bouquet, FlockBERMUNDNo ratings yet

- Covid ReminderDocument2 pagesCovid ReminderBERMUNDNo ratings yet

- Printer and School Triage RepairDocument1 pagePrinter and School Triage RepairBERMUNDNo ratings yet

- Hermeneutical PhenomenologyDocument14 pagesHermeneutical PhenomenologyBERMUNDNo ratings yet

- Child-Friendly Schools ManualDocument244 pagesChild-Friendly Schools ManualUNICEF100% (20)

- School Response Flow Chart: Student BullyingDocument2 pagesSchool Response Flow Chart: Student BullyingBERMUNDNo ratings yet

- Role Play - Rubric 1Document1 pageRole Play - Rubric 1Siti ShalihaNo ratings yet

- SHS DLL Week 3 PDFDocument4 pagesSHS DLL Week 3 PDFEhnan J LamitaNo ratings yet

- Role Play - Rubric 1Document1 pageRole Play - Rubric 1Siti ShalihaNo ratings yet

- CAR DLL July 3 - 7, 2017 Grade 12Document3 pagesCAR DLL July 3 - 7, 2017 Grade 12Darwin Mateo SantosNo ratings yet

- Why Study Social ScienceDocument1 pageWhy Study Social ScienceBERMUNDNo ratings yet

- Trends, Networks and Critical Thinking in The 21 ST Century Culture DLPDocument24 pagesTrends, Networks and Critical Thinking in The 21 ST Century Culture DLPJodan Cayanan97% (36)