Professional Documents

Culture Documents

43895141

Uploaded by

シャルマrohxnCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

43895141

Uploaded by

シャルマrohxnCopyright:

Available Formats

Karl Marx, "Global Theorist"

Author(s): Aijaz Ahmad

Source: Dialectical Anthropology , June 2015, Vol. 39, No. 2 (June 2015), pp. 199-209

Published by: Springer

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43895141

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Dialectical

Anthropology

This content downloaded from

106.213.85.62 on Tue, 31 Jan 2023 10:58:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Dialect Anthropol (2015) 39:199-209

DOI 1 0. 1 007/s 1 0624-0 15-9382-5 CrossMark

Karl Marx, "Global Theorist"

Aijaz Ahmad1

Published online: 7 May 2015

© Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2015

Invitation to participate in a discussion of Kevin B. Anderson's distinguished

contribution to Marx studies is a great pleasure. His prose is refreshingly lucid and

free of jargon, and his arguments rest on a rare combination of extensive research,

nuanced theoretical grasp and close textual analysis. His previous publications, his

continuing work on the yet unpublished notebooks from Marx's last years, as well

as some remarks in the book itself suggest that he has been engaged with this project

for well over a decade, perhaps closer to two. The book is thus a product of patient,

formidable scholarship. My agreements with him are so extensive that the following

comments shall be more in the nature of clarifying certain positions and adding my

own arguments to his.

A statement of Anderson's essential objective comes early:

"I argue for a move toward a twenty-first century notion of Marx as a global

theorist whose social critique included notions of capital and class that were

open and broad enough to encompass the particularities of nationalism, race,

and ethnicity, as well as the varieties of human social and historical

development, from Europe to Asia and from the Americas to Africa. Thus, I

will be presenting Marx as a much more multilinear theorist of history and

society than is generally supposed... (p. 6)"

I doubt that this characterization of Marx "as a global theorist" is a particularly

"twenty-first century notion." What follows in the rest of the sentence is, however,

salutary, essential and much closer to how Marx has been seen for a long time

among those Asian Marxists who have been organically linked to anti-colonial and

socialist movements. The charge of Marx's Eurocentricity was manufactured

Kl Aijaz Ahmad

1 New Delhi, India

Ô Springer

This content downloaded from

106.213.85.62 on Tue, 31 Jan 2023 10:58:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

200 A. Ahmad

mainly in Ang

precincts, afte

Atlantic.

Four virtues stand out in Anderson's book right away. First, he examines

Marx's writings from late 1840s up to the very end of his days - the Manifesto

onwards, so to speak - deftly sidestepping issues of Early and Late Marx,

Epistemological Breaks, etc., and tracing continuity as well as reorientation in

Marx's thought at various points. Second, even as one whose intellectual

affiliations are clear even from the fact of his dedicating the book to Raya

Dunayevskaya ("my intellectual mentor") and to Lawrence Krader, he avoids

equally shrewdly the theological disputes over Marx's materialism versus

humanism; the humanist concern remains grounded, dialectically, in concerns

about material life and social relations of production. Third, and in keeping with

the kind of writer Marx was, Anderson accords great importance to Marx's

journalism, correspondence, and the whole chaos and scattered brilliance of the

late notebooks, published and yet unpublished - without neglecting the central

texts of the great "Economics": the Grundrisse and Capital. Fourth, Anderson is

on firm ground in insisting on the central importance of the French edition of

Capital Volume 1, as the last version of the volume prepared under Marx's own

supervision and one in which he made numerous additions and corrections, of style

as well as substance.

At its core, Marx at the Margins is largely a work of great synthesis. Various

collections of Marx's writings on India were published in the Soviet Union as well

as India, and those writings - hence a whole range of Marx's views on Indian

history and social structure, on colonialism and anti-colonialism, nationalism, etc. -

have been discussed among Indian Marxists of various persuasions almost ad

infinitum . The latest and in my view the most definitive edition of those writings was

published in Delhi in 2006, which Anderson duly acknowledges.1 The writings of

Marx and Engels on Ireland were likewise distributed and studied very widely, in

Ireland and beyond; it has been understood quite clearly that Marx thought of the

Irish question as a colonial question, an agrarian question and a national question

simultaneously. Various other collections of that kind - on Colonialism, the Eastern

Question etc. - were issued from Moscow and were read avidly, often reprinted in

one form or another, across the Tricontinent and in socialist and/or communist

parties more generally. I have myself edited a slim volume in which selections from

their writings on India and Ireland are published together with writings on Germany

and Poland, along with more general writings and letters on these questions, with

the assertion that, as I put it in the introduction, "our understanding of these

questions would be very much richer if we do not detach their thinking on nations

and national movements in Europe from their thinking on colony and nation in the

Asian context."2 I had also argued that Marx "(a) tended to view various

Iqbal Husain (ed), Karl Marx on India, with Introduction by Irfan Habib and Appreciation by Prabhat

Patnaik, Tulika Books, New Delhi, 2006.

2 Aijaz Ahmad (ed). Karl Marx & Fredrick Engels, On the National and Colonial Questions: Selected

Writings, LeftWord, Delhi, 2001.

Springer

This content downloaded from

106.213.85.62 on Tue, 31 Jan 2023 10:58:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Karl Marx, "Global Theorist" 201

geographical areas of the world,

common world history and (b

reappears in altered form in bet

render intelligible a shared huma

different historical contexts." I

political militants in India, mainl

only with my own, which a p

generally been understood about

Anglo-American zones.

Anderson is a scholar of integr

Habib in the case of India for ins

to all the manuscripts of the not

kept his focus in Chapter Six ("L

Societies") largely on publishe

selections from the Ethnologic

Shanin's Late Marx and the Russ

that it brings together into pro

arguments that have been availab

examined in an integrated frame

read him on the American Civ

Germany may not be aware of t

Russian Commune and analogo

together,adds more research and

The Marx Anderson presents is

Asian Marxists more generally bu

aftermath of the cultural tur

"orientalism-in-reverse." How so?

One way of grasping this oddity is that in the Asian countries, the very first

encounters with Marx's writings occurred during the earlier half of the twentieth

century in quite specific circumstances, The broadest context was that of the impact

of the Bolshevik Revolution on anti-colonial movements, whether in the fully

colonized formations such as those of India and Vietnam or in such semi-colonies as

China and Iran, so that Marxism was seen - and lived - from the beginning as much

more a practical politics, and a revolutionary desire, than as research object. These

were predominantly agrarian societies with very rudimentary development of

capitalist economy but far-reaching transformations in structures of law and state

authority under colonial pressure. Primary ("primitive") accumulation was not a

matter of the past only but an ongoing process, with the difference that the final

accumulation was taking place not within the national territory but in the colonizing

metropolis. The Marxist left in Asian countries that was involved in anti-colonial

and socialist mass politics was immersed in the agrarian question sociologically as

well as politically: social structures and property relations in the agrarian economy,

the question of transition (Mao's "New Democracy" for instance), role of the

peasantry in a "socialist" revolution, the question of the worker-peasant alliance

and the relationship of such an alliance with anti-colonial nationalist politics as a

whole. In Asia, typically, great importance was given to Marx's writings on

Springer

This content downloaded from

106.213.85.62 on Tue, 31 Jan 2023 10:58:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

202 A. Ahmad

colonialism,

diverse as I

anti-colonia

capitalist fo

of that kin

precursor of

India, China

movements,

conditioned

This exten

presuppositi

ways even a

have vanishe

great intere

communal p

or India but

shortly befo

were everyw

to lay the fo

but also beca

responsive t

great ravage

property ha

insists, corr

outside the

kind of life

even among

social solidar

of mere theoretical inference. Those memories and what remains of those value

systems are very much at stake in very many forms of contemporary politics, from

the Left as well as the Radical Right. Latin America's movements of the indigenous

as much as Liberation Theology's particular ways of reading the Bible are two

examples of how a postcapitalist vision invokes memories and value systems of the

long precapitalist past. Conversely, the Radical Right, whether of the Christian or of

the Islamist vintage, also invokes those same values - of solidarity, collectivity,

community, family - holding out the promise of redemption to individuals and

groups reeling under alienations and insecurities of the capitalist world.

In India at least, the country I know best and one that comes up frequently in

Anderson's fine-grained book, our homegrown Marxism has until recently displayed

certain notable features. Leaving aside the question of the political orientations of

the more recent subalternist/postcolonialist tendencies, hardly any Indian Marxist

has taken seriously the idea that Marx was some sort of Eurocentric, racist admirer

of European colonialism; his outright, extensive denunciations of colonial practices

and colonial scholarship of his time have always been much too well known. As

heirs to India's own anti-colonial nationalism, many in the Indian Left are quite

aware of the fact that even within the colonial period, anti-caste reform movements

Springer

This content downloaded from

106.213.85.62 on Tue, 31 Jan 2023 10:58:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Karl Marx, "Global Theorist" 203

of the modem type have an olde

deed, if there is a persistent kern

of Buddhism to modernday socia

opposition to the obnoxious cr

fruitfully inherit a tradition rid

Logically, therefore, no Indian M

abusive language Marx used about

propertied classes which sanction

If I have any partial reservation

in relation to India, it is that

"Eurocentricity" (he seems to fin

1853 on India, and then less and

"progressive" expectations from

described as the anachronisms an

in considering the positive poten

village, Anderson does not engage

caste not just as an ideological su

labor for the majority of the pop

within the village community. I

arguments on this score and only

issue of caste, for instance, Amb

supervised the writing of the In

correct in arguing that the Ind

determinism - was at least as cru

also believed, correctly, that Ind

prior destruction of the caste sy

society was so deeply structured

never be truly destroyed while th

He also thought that the traditio

system gets played out, and he

sentimentalization of the Indian

India Marx took into account fac

who has read Ambedkar on the m

Marx's language about tradition

agreement between the two.

As for the "progressive" role

immediately. Marx was far less s

liberals of the nineteenth cent

intelligentsia of the same period

with a historically informed c

modern Indian intellectuals, led b

father of Indian Modernism," exp

introduce far-reaching reforms

guage, "Western civilization" i

immolation, child marriage and p

English language as a window

Springer

This content downloaded from

106.213.85.62 on Tue, 31 Jan 2023 10:58:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

204 A. Ahmad

sciences as w

Rationalism

anti-caste lea

later expect

nationalist le

Ambedkar, t

caste nation

Independence

destruction o

quite refused

system that

Hinduism alt

Anderson is

view, howev

between M

colonialism,

mode of pro

he is said to

large. Howev

The largest

production."

systems of p

were quite un

in the Grund

with the ca

preeminent p

Over roughl

Commune, M

event, most

Anderson cal

scale of the

purposes disa

"Asiatic mod

Like many o

varying degr

data, but nev

altogether.

which is uns

the 1840s, in

writings, m

correspondi

production,

succession of

is it to Asia

what comes

"vegetative,

Ô Springer

This content downloaded from

106.213.85.62 on Tue, 31 Jan 2023 10:58:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Karl Marx, "Global Theorist" 205

Persia, but also Russia, Algeria,

Others" in the postcolonialist fa

system" is sometimes off-hande

even though he was perfectly awa

magisterial levels of state forma

nature of the caste system that

places as the "despotic" characte

what Marx calls "the Asiatic m

device which t helped him think

the materials proved to be too c

mode of production, distinct in

thinking about the problems at h

issue of "the communal."

Debates on these issues have been immense and I claim no special authority in

the matter. I do find very intriguing Samir Amin's schema which postulates a

multiplicity of tributary forms in precapitalist societies in which the exploitative

collection of tribute from the direct producers was universal but the form it took -

property and production relations, nature of political authority etc. - was always

distinctive, corresponding to time, place and the type of production involved

(agrarianate zones and the arid ones, temperate zones and the tropical ones,

variations in fertility of soil, demographic density, etc., even inside the so-called

Asiatic). Amin then goes on to argue that feudalism was one of these tributary

forms, specific to large parts of Europe and possibly Japan but by no means a

historical phase of precapitalist economy universally. I don't entirely subscribe to

all that Amin says on the matter but I do think that one of the merits of this

approach, among others, is that it has no interest in the bipolarity of Europe and

non-Europe. We too can then abandon the heuristic device of "the Asiatic mode of

production" and get down to the serious business of a historical sociology that can

in deed start documenting "multilinearity" in that very much larger part of the

world that is not Europe.

What is very much more important in Marx's own writing, more important than

the matter of the "Asiatic" is his immersion in the issue of "the communal" -

communal property, communal labor and the sort of society that arose on that basis.

And the question for him: now that the modern form of the "communal" - the Paris

Commune - has been beaten back in the short run, is it possible to think of those

communal forms in pre- and non-capitalist countries, in "non-Europe," serving as a

basis of revolutionary transformations there? That question is explosive. It

repudiates the idea that socialism can come only after capitalism has realized all

its potentialities, and for societies that are not already yoked to capitalism, it affirms

the possibility of bypassing the capitalist phase altogether. I concur with Anderson's

four submissions on this question. One that after all the hesitations and the drafting

and re-drafting of his answer to the question, he did affirm that such a transition was

not only possible but also desirable. Second, however, Marx did emphasize that the

communal form was only one form of property in societies where it had persisted

and the appropriate transformations would have to occur in other forms of property

and social organization to sustain that basis on the national level (all-Russia level,

Springer

This content downloaded from

106.213.85.62 on Tue, 31 Jan 2023 10:58:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

206 A. Ahmad

for instance)

was itself no

the transitio

bypassing of

combined, ei

capitalist cou

interpretatio

that Marx di

bypassing th

revolution in

view in 191

combine wit

in the more

Russia to ma

For our own

in Latin Ame

challenging c

eventually

spawned - an

multiplicity

As for enthu

Marx makes

as, at once ,

have to conc

column and t

bad side of it

That is the f

good side of

gradually. F

intertwined

leap beyond

Does the sam

colonial conq

Marx speaks

goes so far i

tool of histo

the transitio

the barbarit

work there:

I should hav

1844 (hencef

text in which

as the centra

dialectic wa

dialectic as it

Anderson fo

Springer

This content downloaded from

106.213.85.62 on Tue, 31 Jan 2023 10:58:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Karl Marx, "Global Theorist" 207

issue in Marxist theory, a pos

surprising that he takes the Man

largely ignores the philosophical

before the Manifesto, Marx's sw

very humanity of human beings

intrinsically, a text of high p

conceptualized in one way, polem

be construed as boundless enthusi

passages from the much more

polemical but philosophically prof

the young Marx well before that

The idea that Marx was some ad

not hold that view but, in my

Roughly the same is true, I belie

on the matter does gain in nua

however, that even in his writing

colonialism far outweigh any hop

is subjected to an unconditiona

colonialism.

Was it really all that reactionary in 1853 to imagine that colonialism may, for all

its depredations, have some positive potentialities to it? This question has been

partially addressed earlier, in comments on how modern intellectuals in 19th

century India and how anti-caste leaders who came somewhat later viewed this

question. I shall soon come to the specifics of what Marx actually wrote. Let me

preface that with two remarks. One, it is chastening to recall that Hegel actually

welcomed the arrival of Napoleon in Jena (History on Horseback, as it were) which

is of course not how Fichte viewed the matter. In other words, there is at least the

possibility that what is foreign may actually be more progressive than the

indigenous at a particular historical juncture, so that, in our own context, opposition

to colonialism and imperialism ought not become a mere anti-Westernism, in the

manner of, say, the Islamist Right. Second, the unity of opposites is not all that there

is to the dialectic but it is an important moment of it, and to speak of unity is not to

speak of equivalence; one side of the opposites may be dominant, the other

emergent, or whatever. A discrepant unity is still a unity of sorts. With these

provisos in hand, let us turn to the letter of Marx's writings:

In the very first of his oft-quoted essay of June 1853, "The British Rule in India"

we read: "...the misery inflicted by the British on Hindustan is of an essentially

different and infinitely more intensive kind than all Hindustan had to suffer before"

and "England has broken down the entire framework of Indian society, without any

symptoms of reconstitution yet appearing." Then: "This loss of his old world, with

no gain of a new one, imparts a particular kind of melancholy to the present misery

of the Hindu, and separates Hindustan, ruled by Britain, from all his traditions, and

from the whole of its past history." Later in this short essay, Marx speaks of "the

deterioration of an agriculture which is not capable of being conducted on the

British principle of free competition" and then, after lyrical descriptions of India's

massive cotton exports to Europe and consequently the great prosperity of the

^ Springer

This content downloaded from

106.213.85.62 on Tue, 31 Jan 2023 10:58:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

208 A. Ahmad

Indian artisa

who eventu

backing up h

despatch of

hybrid of la

which the Br

"not capable

Marx goes to

establishing.

One could go on but the point is that if the earliest of the 1853 despatches take

this view, it is hard to see just how Marx could be seen as an enthusiast of

colonialism even at that stage. Eventually, that characterization rests on famous

formulations of the following kind:

England has to fulfil a double mission in India: one destructive, the other

regenerating - the annihilation of old Asiatic society, and the laying of the

material foundations of Western society in Asia.

That is actually somewhat similar to what Hegel thought a Napoleonic

occupation of Germany - the injection of French revolutionary milieu into his

own moribund homeland - might accomplish. Unlike Marx, however, Hegel's

sanguine hopes were not tempered with awareness of Napoleonic imperialism's

"vile interests" in Germany: the reactionary side of the agents of progress.

The other formulation of Marx that has come in for much ridicule runs as

follows:

England, it is true, in causing a social revolution in Hindustan, was actuated

only by the vilest interests, and was stupid in her manner of enforcing them.

But that is not the question. The question is, can mankind fulfil its destiny

without a fundamental revolution in the social state of Asia? If not, whatever

may have been the crimes of England she was the unconscious tool of history

in bring about that revolution.

Marx follows the latter formulation with a quotation from Goethe. As is well

known, that passage, followed by that particular quotation from Goethe, brought

forth much ire from Edward Said, and Anderson's commentary on that misplaced

ire (pp. 17-21) is erudite, delicious and irrefutable. Let me add just a couple of

points.

Once Marx has clarified that England "was actuated only by the vilest interests,"

it becomes very difficult to argue that he was in any meaningful sense an enthusiast

of colonialism even in 1853. Moreover, Anderson quite rightly commends Marx for

holding a universalist idea of human liberation: social revolution in Asia has to be

intrinsically a part of humanity's overall quest for freedom. Could colonialism bring

about this "social revolution?" Marx spelled out his basic position in a despatch

published in August that year:

All the English bourgeoisie may be forced to do will neither emancipate nor

materially mend the social conditions of the masses of the people, depending

Ô Springer

This content downloaded from

106.213.85.62 on Tue, 31 Jan 2023 10:58:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Karl Marx, "Global Theorist" 209

not only on the development

appropriation by the people.... Th

elements of society scattered am

Great Britain itself the new ruli

industrial proletariat, or till the

enough to throw off the English

Whatever good British colonialism

neither "emancipate" the Indian

revolution consists, in India as mu

the productive powers" but, cen

Quoting this same passage in a boo

Three things about this judgem

influential Indian reformer of the

Ahmed Khan to the founders of

clear-cut a position on the issu

himself was to spend the years du

British Army. Second, every

developed after 1919, from the G

only the most obscurantist, would

the idea that colonial capitalism d

India, some of which need very m

some interest to us here that Ma

context but of "the Hindus" (by w

country) in the context of India.

European revolution had been das

three things in the short run: a

revolution in India, and the brea

I see no reason to change my mind

"the English yoke" did become s

particular sense: in addition to affir

he immediately called "a nation

position was more advanced than th

kind. Gandhi never condemned the

caste system, often justified caste

issue of Untouchability as a particu

by contrast, the caste system was at

ferocious hierarchy in the social r

moreover, that was given religious

A number of unfortunate rhetor

mental positions on some of the k

held by luminaries of India's own

the 20th century. Expecting more

pauperized life in nineteenth ce

Postcolonialist pressure on this iss

Ô Springer

This content downloaded from

106.213.85.62 on Tue, 31 Jan 2023 10:58:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Marx at the Margins: On Nationalism, Ethnicity, and Non-Western SocietiesFrom EverandMarx at the Margins: On Nationalism, Ethnicity, and Non-Western SocietiesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- 251-262. 8. Social Context and The Failure of TheoryDocument13 pages251-262. 8. Social Context and The Failure of TheoryBaha ZaferNo ratings yet

- MARXIST LITERARY CRITICISM: WHAT IT IS NOTDocument9 pagesMARXIST LITERARY CRITICISM: WHAT IT IS NOTSukriti GudiyaNo ratings yet

- Marx's Eurocentrism. Postcolonial Studies and Marx ScholarshipDocument27 pagesMarx's Eurocentrism. Postcolonial Studies and Marx ScholarshipTelmaNo ratings yet

- Marx's Engagement with Darwin's Evolutionary TheoryDocument10 pagesMarx's Engagement with Darwin's Evolutionary TheoryAli AziziNo ratings yet

- Marx & History: From Primitive Society to the Communist FutureFrom EverandMarx & History: From Primitive Society to the Communist FutureNo ratings yet

- Anderson Book Review Marx at The Margins Healy 20101106Document4 pagesAnderson Book Review Marx at The Margins Healy 20101106David Flores MagónNo ratings yet

- Marxism and Modernism: An Historical Study of Lukacs, Brecht, Benjamin, and AdornoFrom EverandMarxism and Modernism: An Historical Study of Lukacs, Brecht, Benjamin, and AdornoRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (4)

- Sayer, Derek and Philip Corrigan - Revolution Against The State, The Context and Significance of Marx's Later WritingsDocument18 pagesSayer, Derek and Philip Corrigan - Revolution Against The State, The Context and Significance of Marx's Later WritingsMaks imilijanNo ratings yet

- Revisiting Marx’s Critique of Liberalism: Rethinking Justice, Legality and RightsFrom EverandRevisiting Marx’s Critique of Liberalism: Rethinking Justice, Legality and RightsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Works of Marx and EngelsDocument53 pagesThe Works of Marx and EngelsSubproleNo ratings yet

- Karl Marx on Society and Social Change: With Selections by Friedrich EngelsFrom EverandKarl Marx on Society and Social Change: With Selections by Friedrich EngelsNo ratings yet

- 1 Introduction: Marx, Ethics and Ethical MarxismDocument39 pages1 Introduction: Marx, Ethics and Ethical MarxismbaclayonNo ratings yet

- The Phenomenology of The Anti-Spirit": Adorno's Marxism As Critical TheoryDocument8 pagesThe Phenomenology of The Anti-Spirit": Adorno's Marxism As Critical TheoryEsparzaNo ratings yet

- Marcello Musto - A Reappraisal of Marx's Ethnological Notebooks - Family, Gender, Individual Vs State and Colonialism PDFDocument13 pagesMarcello Musto - A Reappraisal of Marx's Ethnological Notebooks - Family, Gender, Individual Vs State and Colonialism PDFSuresh ChavhanNo ratings yet

- 2 Marxist HistoriographyDocument16 pages2 Marxist Historiographyshiv161No ratings yet

- Eagleton Critica AndersonDocument12 pagesEagleton Critica AndersonGerman CanoNo ratings yet

- Download Karl Marxs Realist Critique Of Capitalism Freedom Alienation And Socialism Paul Raekstad full chapterDocument77 pagesDownload Karl Marxs Realist Critique Of Capitalism Freedom Alienation And Socialism Paul Raekstad full chapterdoug.norman377100% (4)

- Adamson, Walter L. 1981 'Marx's Four Histories - An Approach To His Intellectual Development ' History & Theory, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Dec., Pp. 379 - 402)Document25 pagesAdamson, Walter L. 1981 'Marx's Four Histories - An Approach To His Intellectual Development ' History & Theory, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Dec., Pp. 379 - 402)voxpop88No ratings yet

- Marx's Life, Works, and Legacy ExploredDocument8 pagesMarx's Life, Works, and Legacy ExploredDiego MartínezNo ratings yet

- Marx On Emancipation & Socialist Goals: Retrieving Marx For The FutureDocument266 pagesMarx On Emancipation & Socialist Goals: Retrieving Marx For The FutureromulolelisNo ratings yet

- Marxist Literary Criticism Before Georg Lukacs: January 2016Document5 pagesMarxist Literary Criticism Before Georg Lukacs: January 2016MbongeniNo ratings yet

- NorthDocument17 pagesNorthHamza MughalNo ratings yet

- Marx's Later Writings on Revolution Against the StateDocument19 pagesMarx's Later Writings on Revolution Against the StatedavidsaloNo ratings yet

- The Marxist Criticism of Literature, 1947Document29 pagesThe Marxist Criticism of Literature, 1947Lezan MohammedNo ratings yet

- Marxist Literary Criticism ExploredDocument29 pagesMarxist Literary Criticism ExploredRaja riazur rehmanNo ratings yet

- D D KosambiDocument10 pagesD D KosambiMini DevanNo ratings yet

- Rediscovering LeninDocument212 pagesRediscovering Leninkayraadam913No ratings yet

- Dic MarxDocument230 pagesDic Marxhaoying zhangNo ratings yet

- George C Comninel Alienation and Emancipation in The Work of Karl Marx PDFDocument358 pagesGeorge C Comninel Alienation and Emancipation in The Work of Karl Marx PDFalexandrospatramanisNo ratings yet

- Marxism, Ethics and Politics - The Work of Alasdair MacIntyre (Marx, Engels, and Marxisms) (PDFDrive)Document234 pagesMarxism, Ethics and Politics - The Work of Alasdair MacIntyre (Marx, Engels, and Marxisms) (PDFDrive)Papiya Bairagi100% (1)

- Literary Critical ApproachesDocument18 pagesLiterary Critical ApproachesLloyd LagadNo ratings yet

- 'Orientalism' As Traveling TheoryDocument27 pages'Orientalism' As Traveling Theorypallavi desaiNo ratings yet

- Irfan HabibDocument8 pagesIrfan HabibShoaib DaniyalNo ratings yet

- Informe de Procesador de TextosDocument12 pagesInforme de Procesador de TextosBelen Ramirez CastroNo ratings yet

- Popularity of Marxist School of Thought in African Literature: A Critique.Document7 pagesPopularity of Marxist School of Thought in African Literature: A Critique.IJCIRAS Research PublicationNo ratings yet

- Kosambi Marxism and Indian HistoryDocument4 pagesKosambi Marxism and Indian Historyroopeshkappy9315No ratings yet

- Cultural Materialism in The Selected Short StoriesDocument5 pagesCultural Materialism in The Selected Short StoriesKristian Jane ELLADORANo ratings yet

- Marxisms: Ideologies and Revolution ExplainedDocument20 pagesMarxisms: Ideologies and Revolution ExplainedSurya Voler BeneNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Ideology in Marxist Literary Criticism: Lutfi Hamadi, (PHD)Document15 pagesThe Concept of Ideology in Marxist Literary Criticism: Lutfi Hamadi, (PHD)ERFIN SUGIONONo ratings yet

- Marxist Literary Theory Concept of IdeologyDocument15 pagesMarxist Literary Theory Concept of IdeologyShubhadip AichNo ratings yet

- The Symbolic Construction of Reality: The Legacy of Ernst CassirerFrom EverandThe Symbolic Construction of Reality: The Legacy of Ernst CassirerNo ratings yet

- Marxism and LiteratureDocument4 pagesMarxism and LiteratureCACI PROINTERNo ratings yet

- Beyond Pure Reason: Ferdinand de Saussure's Philosophy of Language and Its Early Romantic AntecedentsDocument12 pagesBeyond Pure Reason: Ferdinand de Saussure's Philosophy of Language and Its Early Romantic AntecedentsColumbia University PressNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Marxist PhilosophyDocument47 pagesAnalysis of Marxist PhilosophyMaryClaireAgpasaRealNo ratings yet

- University of Chicago Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To American Journal of SociologyDocument3 pagesUniversity of Chicago Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To American Journal of SociologyKacper FabianowiczNo ratings yet

- Narrative Fragmentation in Jean Toomer's CaneDocument10 pagesNarrative Fragmentation in Jean Toomer's Caneacie600100% (1)

- Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference - New EditionFrom EverandProvincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference - New EditionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (30)

- The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic SocietiesFrom EverandThe Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic SocietiesNo ratings yet

- Marx's View of Human FreedomDocument12 pagesMarx's View of Human FreedomJoana OlivaNo ratings yet

- Sem IV - Critical Theories - General TopicsDocument24 pagesSem IV - Critical Theories - General TopicsHarshraj SalvitthalNo ratings yet

- Dissertation On Karl MarxDocument8 pagesDissertation On Karl MarxPayToWriteMyPaperCanada100% (1)

- Cuet PG 24 - CP - Paper 1-With Ans KeyDocument15 pagesCuet PG 24 - CP - Paper 1-With Ans KeyarghabijaliNo ratings yet

- By - Team Examvat: Cuet PG 2024Document27 pagesBy - Team Examvat: Cuet PG 2024シャルマrohxnNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Strategic CommunicationDocument16 pagesInternational Journal of Strategic CommunicationシャルマrohxnNo ratings yet

- Gebhardt 2023 Post Truth Populism and The Simulation of Parrhesia A Feminist Critique of Truth Telling After HannahDocument14 pagesGebhardt 2023 Post Truth Populism and The Simulation of Parrhesia A Feminist Critique of Truth Telling After HannahシャルマrohxnNo ratings yet

- Book Review: Shaj Mohan and Divya Dwivedi, Gandhi and Philosophy: On Theoretical ISBN 978-93-88414-43-2Document3 pagesBook Review: Shaj Mohan and Divya Dwivedi, Gandhi and Philosophy: On Theoretical ISBN 978-93-88414-43-2シャルマrohxnNo ratings yet

- Zizek Discusses Lacanian Theory, the Post-Political, and His Controversial ViewsDocument22 pagesZizek Discusses Lacanian Theory, the Post-Political, and His Controversial ViewsシャルマrohxnNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 106.213.85.62 On Tue, 31 Jan 2023 10:57:21 UTCDocument14 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 106.213.85.62 On Tue, 31 Jan 2023 10:57:21 UTCシャルマrohxnNo ratings yet

- Ijsl 2017 0019Document19 pagesIjsl 2017 0019シャルマrohxnNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Topic Introduction - Rohan SharmaDocument1 pageDissertation Topic Introduction - Rohan SharmaシャルマrohxnNo ratings yet

- 3 Paul Baran's Analysis of Economic Backwardness and Economic GrowthDocument43 pages3 Paul Baran's Analysis of Economic Backwardness and Economic GrowthシャルマrohxnNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Word - A Centure of PoliticsDocument164 pagesMicrosoft Word - A Centure of Politicsapi-3769828100% (3)

- Resonus - NotesDocument2 pagesResonus - NotesPushkar ANo ratings yet

- Animal Farm Board Game Answer Sheet1Document2 pagesAnimal Farm Board Game Answer Sheet1Ines Diaz100% (1)

- Kamenetsky - Folklore As Political ToolDocument16 pagesKamenetsky - Folklore As Political ToolJūratėPasakėnėNo ratings yet

- BANNUDocument871 pagesBANNUmuneeba khanNo ratings yet

- Nursery School Admission FormDocument2 pagesNursery School Admission FormLDaC ClassroomsNo ratings yet

- Anarchism and Fascism - AntagonistsDocument3 pagesAnarchism and Fascism - AntagonistsHugãoNo ratings yet

- Identifying Propaganda TechniquesDocument11 pagesIdentifying Propaganda TechniquesVanessa Santuele OcañaNo ratings yet

- Einheit 7 - Global Warfare Brain DumpDocument5 pagesEinheit 7 - Global Warfare Brain DumpScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- U5 - Activity 1 Annotated BibliographyDocument5 pagesU5 - Activity 1 Annotated Bibliographyapi-540531646100% (1)

- Pak Affairs CSS Past Paper AnalysisDocument9 pagesPak Affairs CSS Past Paper AnalysisSajadMetloNo ratings yet

- BSMT II-B Palang, Ashley Jay E. - CHAPTER 5 - SUMMATIVE ACTIVITYDocument2 pagesBSMT II-B Palang, Ashley Jay E. - CHAPTER 5 - SUMMATIVE ACTIVITYAshley jay Palang88% (8)

- Hoover Digest, 2021, No. 2, SpringDocument232 pagesHoover Digest, 2021, No. 2, SpringHoover Institution100% (5)

- Chennai Transit Map Future v1-0Document1 pageChennai Transit Map Future v1-0vijaymythgrNo ratings yet

- Wbcs Mains Hist Geo 2022-1-51Document22 pagesWbcs Mains Hist Geo 2022-1-51Debosruti BhattacharyyaNo ratings yet

- Landmark CasesDocument8 pagesLandmark CasesDarkSlumberNo ratings yet

- 10 MumbaiDocument27 pages10 MumbaiVivek PatilNo ratings yet

- K DHIVAKAR KumarDocument2 pagesK DHIVAKAR KumarDhivakar DhivakarNo ratings yet

- Rizal's First Return Home to the PhilippinesDocument52 pagesRizal's First Return Home to the PhilippinesMaria Mikaela MarcelinoNo ratings yet

- Academic PapersDocument56 pagesAcademic PapersZiah ArkenNo ratings yet

- How Chin Capital Was Moved - Chinland TodayDocument7 pagesHow Chin Capital Was Moved - Chinland TodayLTTuangNo ratings yet

- Assignment #1Document3 pagesAssignment #1Mich ElbirNo ratings yet

- Planilla Latino Petrol - Abril 2023Document10 pagesPlanilla Latino Petrol - Abril 2023María CristinaNo ratings yet

- The Relevance The Anarchism in Modern Society - Sam DolgoffDocument22 pagesThe Relevance The Anarchism in Modern Society - Sam DolgoffJune AlfredNo ratings yet

- Directory of Congressmen of The 15th CongressDocument60 pagesDirectory of Congressmen of The 15th CongressRG CruzNo ratings yet

- EDSA CarrascoDocument4 pagesEDSA CarrascoLester ManiquezNo ratings yet

- W Ork Permit Entrypass: Important: Ensure That This Approval Has Not Been Cancelled Nor ExpiredDocument1 pageW Ork Permit Entrypass: Important: Ensure That This Approval Has Not Been Cancelled Nor ExpiredFiroz Khan100% (1)

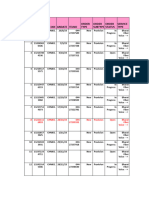

- FTTH An Pending As On 02.01.2024Document20 pagesFTTH An Pending As On 02.01.2024bhpyforeverNo ratings yet

- Kim They Armed in Self Defense Newsweek 18 May 1992Document1 pageKim They Armed in Self Defense Newsweek 18 May 1992Luiz FranciscoNo ratings yet

- The Old Siamese Conception of MonarchyDocument16 pagesThe Old Siamese Conception of Monarchysiu_thailandNo ratings yet