Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Adult Primary Central Nervous System Vasculitis2012

Uploaded by

Nicolas RodriguezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Adult Primary Central Nervous System Vasculitis2012

Uploaded by

Nicolas RodriguezCopyright:

Available Formats

Seminar

Adult primary central nervous system vasculitis

Carlo Salvarani, Robert D Brown Jr, Gene G Hunder

Primary CNS vasculitis is an uncommon disorder of unknown cause that is restricted to brain and spinal cord. The Lancet 2012; 380: 767–77

median age of onset is 50 years. The neurological manifestations are diverse, but generally consist of headache, Published Online

altered cognition, focal weakness, or stroke. Serological markers of inflammation are usually normal. Cerebrospinal May 9, 2012

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

fluid is abnormal in about 80–90% of patients. Diagnosis is unlikely in the presence of a normal MRI of the brain.

S0140-6736(12)60069-5

Biopsy of CNS tissue showing vasculitis is the only definitive test; however, angiography has often been used for

Unit of Rheumatology,

diagnosis even though it has only moderate sensitivity and specificity. The size of the affected vessels varies and Department of Internal

determines outcome and response to treatment. Early recognition is important because treatment with corticosteroids Medicine, Azienda Ospedaliera

with or without cytotoxic drugs can often prevent serious outcomes. The differential diagnosis includes reversible ASMN, Istituto di Ricovero e

Cura a Carattere Scientifico,

cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes and secondary cerebral vasculitis.

Reggio Emilia, Italy

(C Salvarani MD);

Introduction patients without histological verification but with a Department of Neurology

Primary CNS vasculitis is an uncommon and poorly high-probability angiogram, an abnormal MRI, and (Prof R D Brown Jr MD),

and College of Medicine

understood vasculitis restricted to brain and spinal cord. cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis consistent with pri-

(Prof G G Hunder MD), Mayo

Recognition of this disorder as a distinct nosological mary CNS vasculitis. Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

entity dates back to the mid-1950s when Cravioto Advances in neuroimaging techniques used to study Correspondence to:

and Feigin1 described several cases of non-infectious the wall of intracranial blood vessels could improve Dr Carlo Salvarani, Unit of

granulomatous angiitis associated with the nervous detection of inflammation and therefore the validity Rheumatology, Department of

Internal Medicine, Azienda

system.2 Since then, primary CNS vasculitis has been of the criteria.19 Angiographic changes that are highly

Ospedaliera ASMN, Istituto di

referred to as granulomatous angiitis of the CNS,3,4 suggestive of vasculitis are alternating areas of smooth- Ricovero e Cura a Carattere

or more specifically, non-infectious5 or idiopathic6 gran- wall narrowing and dilatation of cerebral arteries or Scientifico, 42123 Reggio Emilia,

ulomatous angiitis of the CNS, and giant-cell arteritis of arterial occlusions affecting many cerebral vessels in the Italy

salvarani.carlo@asmn.re.it

the CNS,7 isolated angiitis of the CNS,8 primary angiitis absence of proximal vessel atherosclerosis or other recog-

of the CNS,9 and benign angiopathy of the CNS.10 nised abnormalities.15 One abnormality in several arteries

Outcome in early reports was frequently fatal, and or several abnormalities in one artery is less consistent

diagnosis was often made at autopsy.1–3,5,7,11 By contrast, in with primary CNS vasculitis.

later studies outcomes were more favourable, and biopsy Because of the invasive nature of CNS biopsy, angi-

and angiography were used for diagnosis.8,9,12 Primary ography is often used to verify diagnosis in patients with

CNS vasculitis needs to be differentiated from disorders compatible clinical findings. However, the accuracy of

that closely resemble it so that appropriate treatment can angiography is uncertain because angiographic changes

be provided.10,13 typical of vasculitis can also be seen in non-vasculitic

disorders.12,20 Furthermore, in pathologically documented

Diagnostic criteria cases, cerebral angiography might be normal, suggesting

Calabrese and Mallek9 proposed criteria for diagnosis of that vascular abnormalities can occur in arteries smaller

primary CNS vasculitis on the basis of clinical experience than the resolution of angiography.4,6,21

and evidence from published work. Diagnosis is made if Cerebral and meningeal biopsy is the gold standard

all three of the following criteria are met: history or for diagnosis of primary CNS vasculitis.12,22–24 The risk is

clinical findings of an acquired neurological deficit of low when skilled surgeons do the biopsy (1% risk of

unknown origin after a thorough initial basic assessment; neurological sequelae). A positive biopsy sample verifies

cerebral angiogram with classic features of vasculitis, or the presence of vasculitis, and excludes mimickers.

a CNS biopsy sample showing vasculitis; and no evidence

of systemic vasculitis or any other disorder to which the

angiographic or pathological features could be secondary. Search strategy and selection criteria

These criteria were also adopted for childhood primary We searched the Cochrane Library, Medline, and Embase

CNS vasculitis, and although they have never been with the search terms “vasculitis”, “angiitis”, or

validated for use in children or adults, they have been “angiopathy” in combination with the terms “central

widely used in clinical practice and research.14 However, nervous system”, “cerebral”, or “intracranial”. We selected

the use of angiography as a gold standard for diagnosis articles mostly in English from the past 5 years, without

has limitations. Overall, the sensitivity of angiography excluding older articles that we thought were highly

varies between 40% and 90%,6,15–17 and cerebral angiograms relevant to this Seminar. We searched the reference lists of

have a specificity as low as 30%.16 To prevent misdiagnosis, articles identified by this search and selected those that we

Birnbaum and Hellmann18 proposed that diagnostic judged relevant. We included some reviews providing

certainty could be classed as definite for patients with insightful overviews on primary CNS vasculitis.

biopsy-proven cerebral vasculitis, and probable for

www.thelancet.com Vol 380 August 25, 2012 767

Seminar

The diagnostic histopathological feature is transmural incidence information available. Primary CNS vasculitis

vascular inflammation of leptomeningeal or paren- occurs at the same frequency in men as in women.15,25 The

chymal vessels. median age at diagnosis is about 50 years, and 50% of

An optimum biopsy should consist of samples of dura, patients were between 37 and 59 years of age at diagnosis.

leptomeninges, cortex, and white matter. Vasculitis affects Long-term survival is reduced in primary CNS vasculitis.15

arteries in a segmental way, therefore a negative biopsy Increased mortality has been linked to cerebral infarctions

does not exclude diagnosis. Evidence suggests that biopsy and large-vessel associations, whereas a lower mortality

has low sensitivity for diagnosis of primary CNS vascu- rate has been seen in patients with MRI gadolinium

litis. Two studies reported sensitivities of 53% and 63%, enhancement of cerebral lesions or the meninges.

respectively.16,23 Biopsy of a radiographically abnormal

area is preferable to random sampling of the non- Pathophysiology

dominant frontal lobe or temporal tip. Miller and The cause and pathogenesis of primary CNS vasculitis

colleagues23 showed that 78% of targeted biopsies were are unknown. Infectious agents have been proposed as

diagnostic, whereas none of the untargeted biopsies triggers because of the well known association of cerebral

showed vasculitis. Inclusion of leptomeninges might vasculitis with infections—in particular varicella zoster

increase the diagnostic yield when primary CNS vasculitis virus (VZV).26 In fact, a wide array of infectious agents

is suspected. Stereotactic guidance can be used for deeper have been linked to vasculitis of CNS (panel).

lesions but is usually unnecessary for frequently biopsied, Inoculation of turkeys intravenously with Mycoplasma

more superficial lesions. gallisepticum induced cerebral vasculitis similar to primary

CNS vasculitis,27 and in two cases of primary CNS vascu-

Epidemiology litis diagnosed at autopsy, electronmicroscopy showed

In the Mayo Clinic series,15 the incidence of primary CNS structures resembling mycoplasma organisms within

vasculitis in Olmsted County, MI, USA, was estimated to giant cells in the wall of affected cerebral arteries.28

be 2·4 cases per 1 000 000 person-years, which is the only The nature of inflammatory infiltrate has rarely been

studied in primary CNS vasculitis. Immunohistochemical

staining of a biopsy sample showed predominant

Panel: Causes of secondary CNS vasculitis infiltration by CD45R0+ T cells in and around small

Viral infections cerebral vessels.29 These findings implicate memory

Varicella zoster virus, HIV, hepatitis C virus, cytomegalovirus, T cells in the pathogenesis of vasculitis, suggesting

parvovirus B19 that primary CNS vasculitis can result from an

antigen-specific immune response occurring in the

Bacterial infections wall of cerebral arteries. Although the triggers of the

Treponema pallidum, Borrelia burgdorferi, Mycobacterium inflammatory process are unknown, specific activation by

tuberculosis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae , Bartonella henselae, pathogen-derived antigens might be crucial in initiation

Rickettsia spp of vasculitis in CNS. In terms of effector molecules,

Fungal infections matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), particularly MMP-9,

Aspergillosis, mucormycosis, coccidioidomycosis, candidosis seem to be pivotal in animal models of vasculitis.30 These

molecules can contribute to vessel wall damage and

Parasitic infections might represent possible therapeutic targets.

Cysticercosis Finally, the link between primary CNS vasculitis

Systemic vasculitides and cerebral amyloid angiopathy is noteworthy.31 The

Wegener’s granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss syndrome, Behçet’s inflammatory reaction to the presence of amyloid β varies

disease, polyarteritis nodosa, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, from little or no inflammation, to perivascular infil-

Kawasaki disease, giant-cell arteritis, Takayasu’s arteritis trates, and to granulomatous vasculitis. The inflam-

matory response to vascular amyloid reported in a

Connective tissue diseases transgenic mouse model of cerebral amyloid angiopathy

Systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, accords with a role for amyloid deposition as a trigger of

SjÖgren’s syndrome, dermatomyositis, mixed connective vascular inflammation.32 Eng and colleagues33 showed

tissue disease that there was a substantial over-representation of the

Miscellaneous APOE ε4/ε4 genotype in patients with inflammation

Antiphospholipid antibodies syndrome, Hodgkin’s and related to cerebral amyloid angiopathy, raising the

non-Hodgkin lymphomas, neurosarcoidosis, inflammatory possibility that the ε4 isoform of apolipoprotein E might

bowel disease, graft-versus-host disease, bacterial play a part in the progression of inflammation to

endocarditis, acute bacterial meningitis, drug-induced CNS cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Elucidation of the molecu-

vasculitis (cocaine, amphetamine, ephedrine, lar basis of inflammation in cerebral amyloid angiopathy

phenylpropanolamine) might identify new targets for treatment of this subset

of patients.

768 www.thelancet.com Vol 380 August 25, 2012

Seminar

Histopathology symptoms. Headache, the most common symptom, can

Primary CNS vasculitis is a vasculitis histologically be generalised or localised, it often slowly worsens, can

affecting small and medium-sized leptomeningeal and spontaneously remit for periods, and varies in severity.

parenchymal arterial vessels. Three main histopatho- Cognitive impairment is also often insidious in onset,

logical patterns are seen:23,34 granulomatous, lymphocytic, and is the second most frequent manifestation. Focal

and necrotising vasculitis. Granulomatous vasculitis is

the most common (58%), showing vasculocentric mono- A

nuclear inflammation and well formed granulomas with

multinucleated cells (figure 1A). β4 amyloid deposition is

seen in almost 50% of biopsy specimens with this pattern

(figure 1B), but is rarely noted in specimens with non- 100 μm

granulomatous primary CNS vasculitis. Lymphocytic

Amyloid

vasculitis is the second most common pattern (28%).

Lymphocytic inflammation predominates, with occa-

sional presence of plasma cells and vessel destruction

(figure 1C). Lymphocytic vasculitis is typically reported in Ischaemic

neurons

children with angiography-negative primary CNS Epithelioid

vasculitis.30 Necrotising vasculitis is the least common 20 μm histocytes 20 μm

pattern (14%) and is characterised by transmural fibrinoid

necrosis similar to that seen in polyarteritis nodosa B

(figure 1D). This process is associated with intracranial

haemorrhage. Occasionally, necrotising and granulo-

matous vasculitis can coexist. Vasculitis can also affect

spinal cord.35 These histological patterns are not closely

linked to specific clinical manifestations, treatment

response, and outcomes. Histological patterns seem to

remain stable over time, suggesting that they do not

represent different phases of the disease. 50 μm 50 μm βA4

Clinical manifestations 20 μm

C

Clinical manifestations at diagnosis are non-specific, and

many symptoms are usually present (table 1).12,15,25 The

onset of disease can be acute, but it is more frequently

insidious and slowly progressive. Diagnosis is made in

75% of patients within 6 months of the onset of

Figure 1: Histopathological features of primary CNS vasculitis

(A) Granulomatous pattern of primary CNS vasculitis. Left-hand image shows

transmural inflammation of a leptomeningeal artery with prominent

mononuclear (bracket) and granulomatous (arrow) adventitial inflammation, and

focal fibrin thrombus formation (asterisk; haematoxylin and eosin [H&E] stain).

20 μm

Inset picture on right shows noticeable thickening and luminal obliteration of

several leptomeningeal vessels (H&E stain). The right-hand image shows focal

collections of epithelioid histiocytes arranged in granuloma-like aggregates.

20 μm 20 μm

Where the lumen is preserved, the vessel wall is thickened by an amorphous D

eosinophilic material (amyloid). Ischaemic neurons can be seen in the adjacent

parenchyma (H&E stain). (B) Granulomatous pattern with amyloid angiopathy in

primary CNS vasculitis. Left-hand image shows destructive vasculitis with well

formed granulomas in leptomeningeal vessels (arrows) and wall thickening with

eosinophilic material (asterisk; H&E stain). The right-hand image shows amyloid-β

deposits in all vessels (immunoperoxidase stain for βA4 amyloid).

(C) Lymphocytic pattern of primary CNS vasculitis. Left-hand and right-hand

images show substantial thickening and luminal obliteration (asterisks mark

lumen remnant) of several leptomeningeal vessels. The infiltrate is predominated

by lymphocytes, but has few histiocytes and granulocytes. Granuloma-like

features are not seen (H&E stain). (D) Necrotising pattern of primary CNS

vasculitis. Left-hand image shows a small leptomeningeal artery with transmural

acute inflammation (H&E stain). Right-hand image shows segmental transmural

fibrinoid necrosis (asterisk), which displays as red-staining material in the vessel

wall (Masson’s trichrome). Haemorrhage and acute infarction are evident in the

underlying cortical parenchyma (right-hand image, bottom).

www.thelancet.com Vol 380 August 25, 2012 769

Seminar

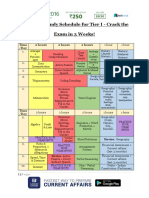

All patients Patients Patients

Special subsets

(n=101) diagnosed diagnosed by Several subsets of primary CNS vasculitis have been

by biopsy angiography identified that can differ in terms of prognosis and

(n=31) (n=70) optimum management. Spinal cord abnormalities are

Headache 64 (63%) 16 (52%) 48 (69%) implicated in about 5% of patients but are rarely

Altered cognition 50 (50%) 22 (71%) 28 (40%) the only manifestation.35 The thoracic cord is predomin-

Hemiparesis 44 (44%) 6 (19%) 38 (54%) antly affected. Careful medical assessment should be

Persistent neurological 40 (40%) 8 (26%) 32 (46%) undertaken to verify diagnosis of primary CNS vasculitis

deficit or stroke and to exclude other disorders associated with acute or

Aphasia 28 (28%) 11 (36%) 17 (24%) subacute transverse myelitis.

Transient ischaemic attack 28 (28%) 5 (16%) 23 (33%) Angiography-negative, biopsy-positive primary CNS

Ataxia 19 (19%) 5 (16%) 14 (20%) vasculitis is a subset in which only very small arteries or

Seizure 16 (16%) 2 (7%) 14 (20%) arterioles are affected—ie, those that are smaller than the

Visual symptom (any kind) 42 (42%) 9 (29%) 33 (47%) resolution of angiography.20 Such patients often present

Visual field defect 21 (21%) 5 (16%) 16 (23%) with cognitive dysfunction, have greatly raised concen-

Diplopia (persistent or 16 (16%) 5 (16%) 11 (16%) trations of CSF protein, have meningeal or parenchymal

transient) enhancing lesions on MRI, respond favourably to

Blurred vision or decreased 11 (11%) 0 (0%) 11 (16%) treatment, and have a good outcome.

visual acuity

Another subset of primary CNS vasculitis is charac-

Monocular visual symptoms 1 (1%) 0 (0%) 1 (1%)

terised by prominent leptomeningeal enhancement on

or amaurosis fugax

MRI.38 These patients have acute clinical onset and

Papilloedema 5 (5%) 2 (7%) 3 (4%)

frequently present with cognitive dysfunction, whereas

Intracranial haemorrhage 8 (8%) 2 (7%) 6 (9%)

magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and cerebral

Amnestic syndrome 9 (9%) 4 (13%) 5 (7%)

angiography are often negative. CNS biopsy samples

Paraparesis or quadriparesis 7 (7%) 4 (13%) 3 (4%)

show granulomatous vascular inflammation. Most

Parkinsonism or 1 (1%) 0 (0%) 1 (1%)

extrapyramidal sign

patients respond to glucocorticoids (alone or combined

Prominent constitutional 9 (9%) 4 (13%) 5 (7%)

with immunosuppressive agents), go on to attain a

symptom normal MRI, and have an overall favourable course.

Fever 9 (9%) 4 (13%) 5 (7%) About a quarter of patients with biopsy-positive pri-

Nausea or vomiting 25 (25%) 6 (19%) 19 (27%) mary CNS vasculitis have evidence of cerebral amyloid

Vertigo or dizziness 9 (9%) 3 (10%) 6 (9%) angiopathy.31 Brain biopsy samples show a granulo-

Dysarthria 15 (15%) 2 (7%) 13 (19%) matous histopathological pattern plus vascular deposits

Unilateral numbness 13 (13%) 0 (0%) 13 (19%) of amyloid β. Patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy

are older than those with primary CNS vasculitis without

Data are number (%). Reproduced from Salvarani and colleagues,15 by permission amyloid deposits, but typically younger than those with

of John Wiley & Sons.

cerebral amyloid angiopathy with no inflammation. They

Table 1: Clinical manifestations at presentation have a high frequency of cognitive dysfunction and

enhancing meningeal lesions on MRI, but usually have

a monophasic disease course and good response to

neurological manifestations with or without distinct immunosuppressive treatment.

cerebral infarction are present in many patients. Other Rapidly progressive primary CNS vasculitis represents

features such as ataxia, seizure, and intracerebral the most ominous subset of this vasculitis, and often has

haemorrhage are less frequent. By contrast with other a fatal outcome. Typically, many bilateral large cerebral

systemic vasculitides, constitutional symptoms such as vessel lesions are seen on angiography, along with several

fever and weight loss are uncommon. bilateral cerebral infarctions. The predominant histo-

Some reports have suggested that patients with primary pathological pattern is granulomatous or necrotising.

CNS vasculitis diagnosed on the basis of abnormal The response to conventional immunosuppressive treat-

angiography alone have a more benign course than do ment is poor.39

those diagnosed by biopsy.10,36 However, in other series, About 4% of patients with primary CNS vasculitis

the clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients present with a solitary tumour-like mass lesion.40 An

diagnosed by biopsy and angiography were similar association with cerebral amyloid angiopathy has been

(table 1).15 Furthermore, others have described a pro- reported in 29% of these patients. Excision of the lesion

gressive course in patients diagnosed by angiography has been curative in some. In others, aggressive

alone.37 The inclusion of patients who are clinically immunosuppressive therapy has resulted in a favourable

suggestive of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syn- outcome, obviating the need for surgery.

drome diagnosed on the basis of angiography alone with Intracranial haemorrhage is a presenting feature in

a benign course might account for these differences.13 11–12% of patients.25,41 Intracerebral haemorrhage is

770 www.thelancet.com Vol 380 August 25, 2012

Seminar

the most common, followed by subarachnoid haem-

A

orrhage. Compared with patients without intracranial

haemorrhage, those with it are less likely to have

altered cognition, a persistent neurological deficit,

or MRI evidence of cerebral infarctions during the

disease course. Necrotising vasculitis is the predominant

histopathological pattern of biopsy specimens.

Laboratory findings, electroencephalography,

and imaging

Results of blood tests in patients with primary CNS

vasculitis are usually normal, and consist of tests for

acute-phase reactants, antinuclear antibodies, anti-

neutrophil cytoplasm antibodies, and antiphospholipid

antibodies.15,25

CSF analysis is abnormal in 80–90% of patients.15

Changes consist of a mildly increased leucocyte

count and total protein concentration. Patients with B

angiography-negative primary CNS vasculitis often have

greatly raised protein concentrations.20 CSF analysis

should be composed of appropriate stains, cultures, sero-

logical and molecular tests, and flow cytometry studies to

exclude infection or malignancy. Most patients have

mild, non-specific electroencephalographic findings.

Cerebral angiography supports diagnosis of primary

CNS vasculitis when biopsy is not undertaken or is

negative despite other indicative clinical and laboratory

evidence.15,25 Suggestive angiographic findings are alter-

nating segments of stenosis with normal or dilated

intervening segments, and arterial occlusions (figure 2).

Other abnormalities are delayed arterial emptying and

anastomotic channels.42 Microaneurysms are rarely seen. C D

Vasculitic lesions usually affect several arteries bilaterally.

In many cases, both large arteries (internal carotid and

intracranial vertebral arteries, basilar artery, and their

primary branches) and smaller arteries are affected.

A limit of angiography is its low specificity. Angio-

graphic findings compatible with vasculitis might be

encountered in several non-vasculitic disorders such as

vasospasm, CNS infection, cerebral arterial emboli, and

atherosclerosis.6,43 Two studies have compared the sensi-

tivity of angiography for detection of vasculitis with the Figure 2: Imaging of patients with primary CNS vasculitis

sensitivity of biopsy. In the Mayo Clinic series,15 43% of (A) Cerebral angiogram shows alternating stenosis and dilatation of the distal

middle cerebral artery (arrows) and the anterior cerebral artery (arrowheads).

angiograms undertaken at diagnosis in patients with

(B) Magnetic resonance angiography of the brain shows a short-segment

histologically proven primary CNS vasculitis were diag- stenosis of the anterior cerebral artery (green arrow) and stenosis of the distal

nostic for vasculitis, whereas in a retrospective review middle cerebral artery (white arrow). (C) Fluid attenuation inversion recovery

only 27% revealed vasculitis.6 Inflammatory changes of (FLAIR)-weighted MRI shows a large abnormality within the right cerebral

hemisphere consistent with ischaemia (arrowheads). (D) MRI shows diffuse,

brain arteries smaller than the resolution of angiography

asymmetric, nodular, and linear leptomeningeal enhancement, with dura only

might partly account for false-negative results.20 How- slightly affected.

ever, despite these limitations, cerebral angiography is

the radiological gold standard for identification of

primary CNS vasculitis. Diagnosis should not be based posterior circulation and distal vessels.15,44 Therefore, in

on positive angiography alone, and angiography results patients with abnormal MRI but normal MRA in the

should always be interpreted in conjunction with clinical, context of strongly suggestive clinical history, cerebral

laboratory, and MRI findings. angiography should be done. Additionally, MRA can

MRA is less invasive than is angiography (figure 2), but overestimate the severity of stenoses at points of vessel

it is less sensitive in detection of lesions associated with branching or vascular occlusions.

www.thelancet.com Vol 380 August 25, 2012 771

Seminar

Primary CNS vasculitis is unlikely if MRI is normal. screening of cerebral artery stenosis or occlusion,55 might

Several studies have reported a sensitivity of MRI close be useful to diagnose and monitor primary CNS vasculitis.

to 100%.16,45 However, patients with primary CNS

vasculitis and normal MRI have been reported.15,43,46 Differential diagnosis

Abnormal MRI findings are non-specific and are cortical Primary CNS vasculitis should be differentiated from

and subcortical infarction, parenchymal and lepto- other similar disorders to avoid therapeutic and prog-

meningeal enhancement, intracranial haemorrhage, nostic errors. The most common mimicker of primary

tumour-like mass lesions, and areas of increased signal CNS vasculitis is reversible cerebral vasoconstriction

intensity on fluid attenuation inversion recovery syndrome.

(FLAIR) or T2-weighted images.15,43,45,47,48 Infarctions are In 2007, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome

the most common lesions, and are usually multiple and was proposed as a collective name for various disorders

bilateral, affecting both the cortex and subcortical that are characterised by brain vasoconstriction rather

regions (figure 2). Prominent leptomeningeal enhance- than by vasculitis13 (ie, Call-Fleming syndrome, post-

ment might suggest a favourable prognosis38 (figure 2). partum angiopathy, migrainous vasospasm, drug-

Both intracerebral and subarachnoid haemorrhage have induced cerebral vasculopathy, and, probably, benign

been described.25,41 angiopathy of the CNS10,36). Reversible cerebral vaso-

Multiple, bilateral supratentorial foci of hyperintensity constriction syndrome presents with sudden severe

on FLAIR and T2-weighted sequences associated most headache (thunderclap), with or without seizures and

frequently with white matter are often seen.15,47 However, focal neurological deficits. Angiography shows constric-

these abnormalities are not specific and are associated tions of cerebral arteries that resolve spontaneously

with other disorders.49 By contrast, vessel wall thicken- within 1–3 months. This disorder affects mainly women

ing and intramural enhancement of large arteries with a mean age of around 45 years. About 60% of

are specific to primary CNS vasculitis.50 Occasionally, patients develop the syndrome in the post-partum period

enhancement can be very noticeable and extend into the or after exposure to vasoactive substances.56 The major

adjacent leptomeningeal tissue (perivascular enhance- complications of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction

ment).43,51,52 Fat-suppressed T1-weighted images are syndrome are localised subarachnoid haemorrhage

especially sensitive for vessel-wall enhancement.53 The (22%) over the sulci and, less frequently, ischaemic or

role of other MRI sequences, such as diffusion-weighted haemorrhagic stroke. To make a diagnosis, evidence of

imaging and perfusion-weighted imaging, in the multifocal segmental cerebral artery vasoconstriction on

detection of vasculitic lesions needs to be defined.54 cerebral angiography or MRA has to be seen, with

High-resolution 3-Tesla contrast-enhanced MRI might complete or almost complete resolution on repeat

be able to differentiate enhancement patterns of intra- examination within 12 weeks of onset. Because reversible

cranial atherosclerotic plaques (eccentric), inflam- cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome can closely mimic

mation (concentric), and other wall abnormalities.19 primary CNS vasculitis, differentiation is crucial since

However, the sensitivity and specificity of this technique immunosuppressive therapy (beyond a short course of

remain to be established. prednisone) is not warranted for syndromes caused by

With respect to other imaging techniques, CT is less vasoconstriction (table 2).

sensitive than is MRI in assessment of lesions of cerebral Common causes of secondary CNS vasculitis are

vasculitis, apart from cerebral haemorrhage. Transcranial infection, systemic vasculitis, connective tissue diseases,

colour-coded sonography, sometimes used for the and miscellaneous disorders (panel). These disorders

PCNSV RCVS

Precipitating factor None Post-partum onset or onset after exposure to vasoactive substances

Onset More insidious, progressive course Acute onset followed by a monophasic course

Headaches Chronic and progressive Acute, thunderclap type

CSF findings Abnormal (leucocytosis and high total protein concentration) Normal to near normal

MRI Abnormal in almost all patients Normal in 70% of patients

Angiography Possibly normal; otherwise, diffuse abnormalities are often Always abnormal, strings of beads appearance of cerebral arteries;

indistinguishable from RCVS; irregular and asymmetrical arterial abnormalities reversible within 6–12 weeks

stenoses or multiple occlusions are more suggestive of PCNSV;

abnormalities might be irreversible

Cerebral biopsy Vasculitis No vasculitic changes

Drug treatment Prednisone with or without cytotoxic agents Nimodipine

PCNSV=primary CNS vasculitis. RCVS=reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. CSF=cerebrospinal fluid.

Table 2: Characteristics of primary CNS vasculitis and reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome

772 www.thelancet.com Vol 380 August 25, 2012

Seminar

should be carefully excluded before primary CNS Wegener’s granulomatosis71 and in only 4% with Churg-

vasculitis is diagnosed. Pathogens can induce CNS Strauss syndrome.73 These patients usually also have

vasculitis through many mechanisms, such as direct evidence of active disease elsewhere.

endothelial invasion and damage. However, in most Neurological symptoms arise in 5·3–14·3% of patients

patients, vasculitis is thought to be mainly the result of with Behçet’s disease, and split the disease into two

the immune response triggered by an invading agent. groups.75 In the parenchymal group, meningoencephalitis

VZV vasculitis causes stroke secondary to viral infection predominantly affecting the brainstem occurs, whereas

of both large and small cerebral arteries.26 Rarely, unifocal in non-parenchymal neurological Behçet’s disease,

vasculitis can follow ophthalmic-distribution zoster in thrombosis within the dural venous sinuses is seen. The

elderly adults or chickenpox in children, and affects large most prominent histopathological feature of neurological

arteries of the anterior or posterior circulation. By Behçet’s disease is the presence of perivascular infil-

contrast, multifocal vasculitis usually affects branches of tration of T lymphocytes and monocytes.81

large or small cerebral arteries, mostly in immuno- With respect to the role of connective tissue diseases,

compromised patients. Diagnosis is based on a history of primary CNS vasculitis is rare in patients with neuro-

recent VZV infection followed by neurological mani- psychiatric lupus, occurring in fewer than 7%.82–84

festations, and is verified by the detection of antiVZV Secondary cerebral vasculitis in rheumatoid arthritis is a

IgG antibody in CSF. Tests for VZV DNA in CSF are rare complication of longstanding, nodular, erosive, and

often negative. seropositive rheumatoid arthritis.85 Clinical CNS mani-

Cerebral vasculitis has been reported with HIV festations are rare in Sjögren’s syndrome (about 5% of

infection, often in association with concomitant infection unselected patients).86 CNS biopsy specimens show

or lymphoproliferative disease of CNS. However, in a few vasculitis in a few patients, but a more typical finding is

patients, CNS vasculitis can occur in the absence of other perivascular mononuclear infiltration, which can extend

detectable diseases, suggesting a direct pathogenic role into the surrounding brain parenchyma.87 Secondary

for HIV.57 Treatment is glucocorticoid therapy. CNS vasculitis has also been described in dermato-

In the meningovascular form of neurosyphilis, myositis and mixed connective tissue disease.88,89 Angio-

vasculitis is believed to result from direct spirochaetal graphic abnormalities suggestive of cerebral vasculitis

invasion of vascular endothelial cells. The most have occasionally been seen in patients with anti-

common presentation is an ischaemic stroke in a young phospholipid antibodies and ischaemic cerebrovascular

adult.58,59 The middle cerebral artery is most often events.90 However, thrombotic vasculopathy rather than

affected, followed by basilar artery. Diagnosis of true vasculitis is the mechanism underlying angiographic

neurosyphilis is verified with positive results from the changes in such patients.

fluorescent treponemal antibody with absorption test Primary CNS vasculitis has been associated with

and CSF venereal disease research laboratory test lymphoma, particularly Hodgkin’s disease, and rarely

together with evidence of CSF pleocytosis and raised with non-Hodgkin lymphoma.91,92 Additionally, intra-

concentrations of CSF protein. vascular lymphoma characterised by the proliferation of

Other infectious agents have been linked to vasculitis clonal lymphocytes within small vessels with little to no

of CNS, such as hepatitis C virus,60 parvovirus B19,61 association with the organ parenchyma can affect the

cytomegalovirus,62 Mycoplasma pneumoniae,63 Borrelia CNS and resemble cerebral vasculitis.93 Angiographic

burgdorferi,64 Mycobacterium tuberculosis,65 Bartonella spp,66 changes suggestive of arteritis have occasionally been

and Rickettsia spp.67 Fungal infections (aspergillosis, reported in neurosarcoidosis; however, histological

mucormycosis, coccidioidomycosis, and candidosis) and changes characteristic of vasculitis in the CNS are

subarachnoid cysticercosis have also been implicated in uncommon in this disorder.94 Secondary CNS vasculitis

some cases.68–70 has also been described in patients with inflammatory

CNS vasculitis might stem from systemic vasculitides, bowel disease and graft-versus-host disease.95,96

such as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)- In bacterial endocarditis, valvular emboli can produce

associated vasculitis and Behçet’s disease, and less cerebrovascular occlusions and a vasculitic pattern on

often from polyarteritis nodosa, Henoch-Schönlein cerebral angiography. The differentiation from primary

purpura, Kawasaki disease, giant-cell arteritis, and CNS vasculitis is very important because the treatment

Takayasu’s arteritis.71–80 CNS symptoms have been differs.97 A vasculitic pattern on vascular imaging has

described in 7–11% of patients with Wegener’s also been reported in patients with acute bacterial

granulomatosis71,72 and 1–8% of patients with Churg- meningitis.98

Strauss syndrome.73,74 In ANCA-associated vasculitis, Although most cases of drug-induced cerebral

CNS manifestations might be caused by vasculitis vasculitis identified by cerebral angiography alone are

affecting the brain, but also by granulomata, uncon- caused by vasospasm and should be regarded as part of

trolled hypertension, sepsis, and coagulation disorders. reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, histo-

However, radiographically verified vasculitis of CNS is logically documented cases of drug-associated CNS

rare, and occurs in fewer than 2% of patients with vasculitis have infrequently been described.99

www.thelancet.com Vol 380 August 25, 2012 773

Seminar

Treatment and course one patient with a rapidly progressive course, and long-

No randomised clinical trials of medical management in term etanercept (50 mg/week) stopped relapse and led to

primary CNS vasculitis exist; therefore, treatment for the discontinuation of prednisone in the second patient.103

primary CNS vasculitis has been derived from therapeutic Anti-CD20 therapy with rituximab has been used

strategies used in other vasculitides, from anecdotal successfully in refractory Wegener’s granulomatosis with

reports, and from cohort studies. Earliest reports CNS features, suggesting a possible therapeutic role for

suggested a poor outlook with fatal outcome in most this drug in primary CNS vasculitis.105

patients, and transient or doubtful effectiveness of All patients should receive prophylactic treatment

glucocorticoids.4,12,100 Studies, including those by Cupps for osteoporosis and prophylaxis against Pneumocystis

and colleagues,8 reported the effectiveness of cyclo- jirovecii infection (co-trimoxazole [trimethoprim 80 mg

phosphamide in combination with corticosteroids.8,101 and sulfamethoxazole 400 mg, per day]).

Since these early reports, cohort studies have described Evidence that all patients with primary CNS vasculitis

a more favourable course of primary CNS vasculitis. In a do not need the same therapy is emerging (appendix).

cohort study of 101 patients, glucocorticoids alone or in Those with several bilaterally affected large vessels, rapidly

combination with cyclophosphamide achieved a favour- progressive disease, and many recurrent cerebral infarc-

able response in most patients.15 Response rates were tions39 should be started promptly on aggressive therapy,

similar (81%) in both treatment groups with improvement although those with progressive disease usually have a

of Rankin scale scores over time. Glucocorticoid therapy poor response to therapy with a fatal outcome. By contrast,

should be started as soon as primary CNS vasculitis is patients with affected small vessels, characterised by

diagnosed. We recommend an initial dose of prednisone prominent leptomeningeal enhancement on MRI or by

of 1 mg/kg per day (or equivalent) as a single or divided negative cerebral angiogram and a positive brain biopsy,

dose. If a patient does not respond promptly, cyclo- typically have a rapid response to treatment with a

phosphamide should be started. favourable neurological outcome.21,38 These patients can

In an approach to reduce the toxic effects of drugs, a thus be given, at least initially, glucocorticoids alone,

3–6 month course of oral cyclophosphamide (2 mg/kg although immunosuppressive agents can be added should

per day) might also be beneficial to induce remission in clinical history, changes to brain or spinal cord MRI

primary CNS vasculitis because it has proved effective in abnormalities, or worsening of spinal fluid examination

See Online for appendix other vasculitides102 (appendix). Intravenous pulses of results suggest persistent disease activity and insufficient

cyclophosphamide (0·75 g/m² per month for 6 months) response to therapy. Patients with primary CNS vasculitis

are probably safer than is daily oral therapy, although with cerebral amyloid angiopathy might also respond to

whether the two regimens differ in terms of effectiveness glucocorticoids alone,31 but often cyclophosphamide has to

is unclear. Infection, cancer (in particular transitional be added to obtain an adequate response. In patients with

cell carcinoma of the bladder), and infertility are the primary CNS vasculitis presenting as a tumour-like mass

most serious toxic effects of cyclophosphamide.102 lesion, aggressive immunosuppressive therapy is associ-

Subsequently, consideration of a low-risk immuno- ated with improved outcomes compared with gluco-

suppressant such as azathioprine (1–2 mg/kg daily), corticoids alone.40 Relapses and recurrences were recorded

methotrexate (20–25 mg/week), or mycophenolate in only 26% of patients in the Mayo Clinic series.15 Patients

mofetil (1–2 g daily) for maintenance of remission is with relapsing disease needed therapy for longer than did

advised. However, little direct evidence exists for the those with non-relapsing disease, but otherwise had

effectiveness of these drugs. A treatment course of outcomes similar to those without relapses.

12–18 months is adequate in most patients.15 Thus, although there have been no controlled thera-

In patients with severe or progressive primary CNS peutic trials, treatment seems to be associated with a

vasculitis that is life-threatening, high-dose intravenous favourable outcome in most patients. In the Mayo Clinic

methylprednisolone (1000 mg daily for 3 days) and series most patients with low disability at diagnosis

cyclophosphamide can be used immediately after continued to have low disability at last follow-up, and

diagnosis, although no evidence exists that methyl- most of the 22 patients with severe disability at diagnosis

prednisolone pulses are more effective than oral had less disability at follow-up.15 These data emphasise

prednisone.15 Repeated pulses of intravenous methyl- the need for early diagnosis, since prompt treatment

prednisolone can also be given for disease flares. Tumour frequently leads to a favourable outcome.

necrosis factor α (TNFα) blockers and mycophenolate Serial MRI and MRA (4–6 weeks after the beginning of

mofetil (2 g daily) can successfully treat patients with treatment, then every 3–4 months during the first year of

primary CNS vasculitis that is resistant to glucocorti- treatment, or when a new neurological deficit arises),

coids and immunosuppressants.103,104 However, only two and repeat careful neurological examinations, are useful

reported patients given TNF blockade for primary CNS to monitor disease course. In patients with stable

vasculitis exist, given to both as adjunctive treatment. imaging but worsening clinical symptoms, repeat spinal

Infliximab (5 mg/kg) seemed to rapidly and effectively fluid examination and repeat angiography might be

improve the neurological status and MRI abnormalities of necessary. For those patients without biopsy verification

774 www.thelancet.com Vol 380 August 25, 2012

Seminar

at the time of initial diagnosis who have worsening 5 Newman W, Wolf A. Non-infectious granulomatous angiitis involving

symptoms despite immunosuppressive therapy, a brain the central nervous system. Trans Am Neurol Assoc 1952; 56: 114–17.

6 Vollmer TL, Guarnaccia J, Harrington W, Pacia SV, Petroff OAF.

biopsy should be considered. Idiopathic granulomatous angiitis of the central nervous system:

Treatment of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syn- diagnostic challenges. Arch Neurol 1993; 50: 925–30.

drome needs a detailed patient history of intake of 7 McCormick HM, Neubuerger KT. Giant-cell arteritis involving

small meningeal and intracerebral vessels. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol

vasoactive substances, with prompt cessation of any 1958; 17: 471–78.

potentially offending agent. In the absence of randomised 8 Cupps TR, Moore PM, Fauci AS. Isolated angiitis of the central

trials, empirical treatment is oral nimodipine (60 mg nervous system. Prospective diagnostic and therapeutic experience.

Am J Med 1983; 74: 97–105.

every 4–8 h for 4–12 weeks), started as soon as the typical

9 Calabrese LH, Mallek JA. Primary angiitis of the central nervous

angiographic pattern is noted. The effectiveness of a short- system. Report of 8 new cases, review of the literature, and proposal

term course of high-dose glucocorticoids is unclear.13,56 for diagnostic criteria. Medicine (Baltimore) 1988; 67: 20–39.

10 Calabrese LH, Gragg LA, Furlan AJ. Benign angiopathy: a distinct

subset of angiographically defined primary angiitis of the central

Future directions nervous system. J Rheumatol 1993; 20: 2046–50.

Our understanding of primary CNS vasculitis and the 11 Lie JT. Primary (granulomatous) angiitis of the central nervous

delineation of its range and subsets has advanced, but system: a clinicopathologic analysis of 15 new cases and a review

of the literature. Hum Pathol 1992; 23: 164–71.

we still need to clarify methods of diagnosis and opti-

12 Moore PM. Diagnosis and management of isolated angiitis of the

mum management. Biomarker and outcome investi- central nervous system. Neurology 1989; 39: 167–73.

gations might identify risk factors for an aggressive 13 Calabrese LH, Dodick DW, Schwedt TJ, Singhal AB. Narrative

course leading to treatment tailored to disease severity. review: reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes.

Ann Intern Med 2007; 146: 34–44.

Effectiveness and safety profiles of intravenous pulse 14 Benseler SM, Silverman E, Aviv RI, et al. Primary central nervous

and oral cyclophosphamide treatment, and clarification system vasculitis in children. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54: 1291–97.

of which patients need cyclophosphamide at disease 15 Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Calamia KT, et al. Primary central nervous

system vasculitis: analysis of 101 patients. Ann Neurol 2007; 62: 442–51.

onset, need to be established. Other drugs should

16 Duna GF, Calabrese LH. Limitations of invasive modalities in the

be studied as substitutes for cyclophosphamide in diagnosis of primary angiitis of the central nervous system.

selected subgroups. J Rheumatol 1995; 22: 662–67.

Because primary CNS vasculitis is uncommon, an 17 Harris KG, Tran DD, Sickels WJ, Cornell SH, Yuh WT. Diagnosing

intracranial vasculitis: the roles of MR and angiography.

international collaborative registry for primary CNS AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1994; 15: 317–30.

vasculitis would help with the development of stan- 18 Birnbaum J, Hellmann DB. Primary angiitis of the central nervous

dardised classification and diagnostic criteria, help to system. Arch Neurol 2009; 66: 704–09.

define homogeneous patient groups for randomised 19 Swartz RH, Bhuta SS, Farb RI, et al. Intracranial arterial wall

imaging using high-resolution 3-tesla contrast-enhanced MRI.

clinical trials, and might aid clinicians in differentiation Neurology 2009; 72: 627–34.

of primary CNS vasculitis from its much more common 20 Kadkhodayan Y, Alreshaid A, Moran CJ, Cross DT 3rd, Powers WJ,

mimickers. Finally, international concerted efforts could Derdeyn CP. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system at

conventional angiography. Radiology 2004; 233: 878–82.

be instrumental in the development of repositories of 21 Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Calamia KT, et al. Angiography-negative

biological specimens that are essential for translational primary central nervous system vasculitis: a syndrome involving

studies. In turn, a better understanding of the molecular small cerebral vessels. Medicine (Baltimore) 2008; 87: 264–71.

22 Parisi JE, Moore PM. The role of biopsy in vasculitis of the central

mechanisms associated with the pathogenesis of nervous system. Semin Neurol 1994; 4: 341–48.

primary CNS vasculitis should provide opportunities to 23 Miller DV, Salvarani C, Hunder GG, et al. Biopsy findings in

improve therapy. primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Am J Surg Pathol

2009; 33: 35–43.

Contributors

24 Alrawi A, Trobe JD, Blaivas M, Musch DC. Brain biopsy in primary

All authors contributed equally. angiitis of the central nervous system. Neurology 1999; 53: 858–60.

Conflicts of interest 25 Calabrese LH, Duna GF, Lie JT. Vasculitis in the central nervous

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest. system. Arthritis Rheum 1997; 40: 1189–201.

26 Nagel MA, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R, et al. The varicella zoster virus

Acknowledgments vasculopathies: clinical, CSF, imaging, and virologic features.

We thank John Huston III, Teresa J H Christianson, Neurology 2008; 70: 853–60.

Kenneth T Calamia, James F Meschia, Caterina Giannini, and 27 Thomas L, Davidson M, McCluskey RT. Studies of PPLO infection.

Dylan Miller for their collaboration in clinical studies on primary CNS I. The production of cerebral polyarteritis by Mycoplasma

vasculitis, John Huston III for providing angiographic and MRI gallisepticum in turkeys; the neurotoxic property of the mycoplasma.

documentation, and Caterina Giannini and Dylan Miller for providing J Exp Med 1966; 123: 897–912.

histopathological documentation. 28 Arthur G, Margolis G. Mycoplasma-like structures in granulomatous

References angiitis of the central nervous system. Case reports with light and

1 Cravioto H, Feigin I. Noninfectious granulomatous angiitis with electron microscopic studies. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1977; 101: 382–87.

a predilection for the nervous system. Neurology 1959; 9: 599–609. 29 Iwase T, Ojika K, Mitake S, et al. Involvement of CD45RO+

2 Harbitz F. Unknown forms of arteritis, with special reference T lymphocyte infiltration in a patient with primary angiitis of the

to their relation to syphilitic arteritis and periarteritis nodosa. central nervous system restricted to small vessels. Eur Neurol 2001;

Am J Med Sci 1922; 163: 250–72. 45: 184–85.

3 Sandhu R, Alexander WS, Hornabrook RW, Stehbens WE. 30 Williams PL, Leib SL, Kamberi P, et al. Levels of matrix

Granulomatous angiitis of the CNS. Arch Neurol 1979; 36: 433–35. metalloproteinase-9 within cerebrospinal fluid in a rabbit model

of coccidioidal meningitis and vasculitis. J Infect Dis 2002;

4 Harrison PE Jr. Granulomatous angiitis of the central nervous 186: 1692–95.

system. Case report and review. J Neurol Sci 1976; 29: 335–41.

www.thelancet.com Vol 380 August 25, 2012 775

Seminar

31 Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Calamia KT, et al. Primary central 55 Hou WH, Liu X, Duan YY, et al. Evaluation of transcranial

nervous system vasculitis: comparison of patients with and without color-coded duplex sonography for cerebral artery stenosis or

cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008; occlusion. Cerebrovasc Dis 2009; 27: 479–84.

47: 1671–77. 56 Ducros A, Bousser MG. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction

32 Winkler DT, Bondolfi L, Herzig MC, et al. Spontaneous syndrome. Pract Neurol 2009; 9: 256–67.

hemorrhagic stroke in a mouse model of cerebral amyloid 57 Melica G, Brugieres P, Lascaux AS, Levy Y, Lelièvre JD. Primary

angiopathy. J Neurosci 2001; 21: 1619–27. vasculitis of the central nervous system in patients infected with

33 Eng JA, Frosch MP, Choi K, Rebeck GW, Greenberg SM. Clinical HIV-1 in the HAART era. J Med Virol 2009; 81: 578–81.

manifestations of cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related 58 Gaa J, Weidauer S, Sitzer M, Lanfermann H, Zanella FE. Cerebral

inflammation. Ann Neurol 2004; 55: 250–56. vasculitis due to Treponema pallidum infection: MRI and MRA

34 Lie JT. Primary (granulomatous) angiitis of the central nervous findings. Eur Radiol 2004; 14: 746–47.

system: a clinicopathologic analysis of 15 new cases and a review 59 Kakumani PL, Hajj-Ali RA. A forgotten cause of central nervous

of the literature. Hum Pathol 1992; 23: 164–71. system vasculitis. J Rheumatol 2009; 36: 655.

35 Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Calamia KT, et al. Primary CNS 60 Cacoub P, Saadoun D, Limal N, Léger JM, Maisonobe T. Hepatitis C

vasculitis with spinal cord involvement. Neurology 2008; virus infection and mixed cryoglobulinaemia vasculitis: a review of

70: 2394–400. neurological complications. AIDS 2005; 19 (suppl 3): S128–34.

36 Hajj-Ali RA, Furlan A, Abou-Chebel A, Calabrese LH. Benign 61 Bilge I, Sadikoğlu B, Emre S, Sirin A, Aydin K, Tatli B. Central

angiopathy of the central nervous system: cohort of 16 patients with nervous system vasculitis secondary to parvovirus B19 infection in a

clinical course and long-term followup. Arthritis Rheum 2002; pediatric renal transplant patient. Pediatr Nephrol 2005; 20: 529–33.

47: 662–69. 62 Golden MP, Hammer SM, Wanke CA, Albrecht MA.

37 Woolfenden AR, Tong DC, Marks MP, Ali AO, Albers GW. Cytomegalovirus vasculitis. Case reports and review of the

Angiographically defined primary angiitis of the CNS: is it really literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1994; 73: 246–55.

benign? Neurology 1998; 51: 183–88. 63 Ovetchkine P, Brugières P, Seradj A, Reinert P, Cohen R. An 8-y-old

38 Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Calamia KT, et al. Primary central boy with acute stroke and radiological signs of cerebral vasculitis

nervous system vasculitis with prominent leptomeningeal after recent Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Scand J Infect Dis

enhancement: a subset with a benign outcome. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 34: 307–09.

2008; 58: 595–603. 64 Heinrich A, Khaw AV, Ahrens N, Kirsch M, Dressel A. Cerebral

39 Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Calamia KT, et al. Rapidly progressive vasculitis as the only manifestation of Borrelia burgdorferi infection

primary central nervous system vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) in a 17-year-old patient with basal ganglia infarction. Eur Neurol

2001; 50: 349–58. 2003; 50: 109–12.

40 Molloy ES, Singhal AB, Calabrese LH. Tumour-like mass lesion: 65 Starke JR. Tuberculosis of the central nervous system in children.

an under-recognised presentation of primary angiitis of the central Semin Pediatr Neurol 1999; 6: 318–31.

nervous system. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67: 1732–35. 66 Marra CM. Neurologic complications of Bartonella henselae

41 Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Calamia KT, et al. Primary central infection. Curr Opin Neurol 1995; 8: 164–69.

nervous system vasculitis presenting with intracranial hemorrhage. 67 Bleck TP. Central nervous system involvement in rickettsial

Arthritis Rheum 2011; 63: 3598–606. diseases. Neurol Clin 1999; 17: 801–12.

42 Ferris EJ, Levine HL. Cerebral arteritis: classification. Radiology 68 Zeller V, Lortholary O. Vasculitis secondary to fungal infections.

1983; 109: 327–41. Presse Med 2004; 33: 1385–88.

43 Alhalabi M, Moore PM. Serial angiography in isolated angiitis 69 Nagashima T, Miyanoshita A, Sakiyama Y, Ozaki Y, Stan AC,

of the central nervous system. Neurology 1994; 44: 1221–26. Nagashima K. Cerebral vasculitis in chronic mucocutaneous

44 Eleftheriou D, Cox T, Saunders D, Klein NJ, Brogan PA, Ganesan V. candidosis: autopsy case report. Neuropathology 2000; 20: 309–14.

Investigation of childhood central nervous system vasculitis: 70 Barinagarrementeria F, Cantú C. Frequency of cerebral arteritis in

magnetic resonance angiography versus catheter cerebral subarachnoid cysticercosis: an angiographic study. Stroke 1998;

angiography. Dev Med Child Neurol 2010; 52: 863–67. 29: 123–25.

45 Pomper MG, Miller TJ, Stone JH, Tidmore WC, Hellmann DB. 71 Nishino H, Rubino FA, DeRemee RA, Swanson JW, Parisi JE.

CNS vasculitis in autoimmune disease: MR imaging findings and Neurological involvement in Wegener’s granulomatosis: an analysis

correlation with angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999; of 324 consecutive patients at the Mayo Clinic. Ann Neurol 1993;

20: 75–85. 33: 4–9.

46 Wasserman BA, Stone JH, Hellmann DB, Pomper MG. Reliability 72 Ghinoi A, Zuccoli G, Pipitone N, Salvarani C. Anti-neutrophil

of normal findings on MR imaging for excluding the diagnosis of cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis involving the

vasculitis of the central nervous system. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; central nervous system: case report and review of the literature.

177: 455–59. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2010; 28: 759–66.

47 Cloft HJ, Phillips CD, Dix JE, McNulty BC, Zagardo MT, Kallmes D. 73 Sehgal M, Swanson JW, DeRemee RA, Colby TV. Neurologic

Correlation of angiography and MR imaging in cerebral vasculitis. manifestations of Churg-Strauss syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc 1995;

Acta Radiol 1999; 40: 83–87. 70: 337–41.

48 Greenan TJ, Grossman RI, Goldberg HI. Cerebral vasculitis: MR 74 Guillevin L, Cohen P, Gayraud M, Lhote F, Jarrousse B, Casassus P.

imaging and angiographic correlation. Radiology 1992; 182: 65–72. Churg-Strauss syndrome. Clinical study and long-term follow-up of

49 Bekiesińska-Figatowska M. T2-hyperintense foci on brain MR 96 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1999; 78: 26–37.

imaging. Med Sci Monit 2004; 10 (suppl 3): 80–87. 75 Al-Araji A, Kidd DP. Neuro-Behçet’s disease: epidemiology,

50 Küker W, Gaertner S, Nagele T, et al. Vessel wall contrast clinical characteristics, and management. Lancet Neurol 2009;

enhancement: a diagnostic sign of cerebral vasculitis. 8: 192–204.

Cerebrovasc Dis 2008; 26: 23–29. 76 Oran I, Memis A, Parildar M, Yunten N. Multiple intracranial

51 Shoemaker EI, Lin ZS, Rae-Grant AD, Little B. Primary angiitis aneurysms in polyarteritis nodosa: MRI and angiography.

of the central nervous system: unusual MR appearance. Neuroradiology 1999; 41: 436–39.

AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1994; 15: 331–34. 77 Gonçalves C, Ferreira G, Mota C, Vilarinho A. Cerebral vasculitis

52 Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Huston J 3rd, Hunder GG. Prominent in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. An Pediatr (Barc) 2004;

perivascular enhancement in primary central nervous system 60: 188–89 (in Spanish).

vasculitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2008; 26 (suppl 49): S111. 78 Tabarki B, Mahdhaoui A, Selmi H, Yacoub M, Essoussi AS.

53 Küker W. Cerebral vasculitis: imaging signs revisited. Kawasaki disease with predominant central nervous system

Neuroradiology 2007; 49: 471–79. involvement. Pediatr Neurol 2001; 25: 239–41.

54 White ML, Hadley WL, Zhang Y, Dogar MA. Analysis of central 79 Salvarani C, Giannini C, Miller DV, Hunder G. Giant cell arteritis:

nervous system vasculitis with diffusion-weighted imaging and Involvement of intracranial arteries. Arthritis Rheum 2006;

apparent diffusion coefficient mapping of the normal-appearing 55: 985–89.

brain. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007; 28: 933–37.

776 www.thelancet.com Vol 380 August 25, 2012

Seminar

80 Ringleb PA, Strittmatter EI, Loewer M, et al. Cerebrovascular 93 Zuckerman D, Seliem R, Hochberg E. Intravascular lymphoma:

manifestations of Takayasu arteritis in Europe. Rheumatology 2005; the oncologist’s “great imitator”. Oncologist 2006; 11: 496–502.

44: 1012–15. 94 Lawrence WP, Gammal T, Pool WH, et al. Radiological

81 Hirohata S. Histopathology of central nervous system lesions manifestations of neurosarcoidosis. Report of three cases and

in Behçet’s disease. J Neurol Sci 2008; 267: 41–47. review of the literature. Clin Radiol 1974; 25: 343–48.

82 Hanly JG, Walsh NM, Sangalang V. Brain pathology in systemic 95 Scheid R, Teich N. Neurologic manifestations of ulcerative colitis.

lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 1992; 19: 732–41. Eur J Neurol 2007; 14: 483–92.

83 Everett CM, Graves TD, Lad S, et al. Aggressive CNS lupus 96 Ma M, Barnes G, Pulliam J, Jezek D, Baumann RJ, Berger JR.

vasculitis in the absence of systemic disease activity. CNS angiitis in graft vs host disease. Neurology 2002; 59: 1994–97.

Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008; 47: 107–09. 97 Berlit P. Isolated angiitis of the CNS and bacterial endocarditis:

84 Ellis SG, Verity MA. Central nervous system involvement in similarities and differences. J Neurol 2009; 256: 792–95.

systemic lupus erythematosus: a review of neuropathologic findings 98 Katchanov J, Siebert E, Klingebiel R, Endres M. Infectious

in 57 cases, 1955–1977. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1979; 8: 212–21. vasculopathy of intracranial large- and medium-sized vessels in

85 Caballol Pons N, Montalà N, Valverde J, Brell M, Ferrer I, neurological intensive care unit: a clinico-radiological study.

Martínez-Yélamos S. Isolated cerebral vasculitis associated with Neurocrit Care 2010; 12: 369–74.

rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine 2010; 77: 361–63. 99 Calabrese LH, Duna GF. Drug-induced vasculitis.

86 Ramos-Casals M, Solans R, Rosas J, et al, for the GEMESS Study Curr Opin Rheumatol 1996; 8: 34–40.

Group. Primary Sjögren syndrome in Spain: clinical and 100 Griffin J, Price DL, Davis L, McKhann GM. Granulomatous angiitis

immunologic expression in 1010 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) of the central nervous system with aneurysms on multiple cerebral

2008; 87: 210–19. arteries. Trans Am Neurol Assoc 1973; 98: 145–48.

87 Niemelä RK, Hakala M. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome with severe 101 Fauci AS, Haynes B, Katz P. The spectrum of vasculitis: clinical,

central nervous system disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1999; 29: 4–13. pathologic, immunologic and therapeutic considerations.

88 Regan M, Haque U, Pomper M, Pardo C, Stone J. Central nervous Ann Intern Med 1978; 89: 660–76.

system vasculitis as a complication of refractory dermatomyositis. 102 Molloy ES, Langford CA. Advances in the treatment of small vessel

J Rheumatol 2001; 28: 207–11. vasculitis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2006; 32: 157–72.

89 Graf WD, Milstein JM, Sherry DD. Stroke and mixed connective 103 Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Calamia KT, et al. Efficacy of tumor

tissue disease. J Child Neurol 1993; 8: 256–59. necrosis factor alpha blockade in primary central nervous system

90 Provenzale JM, Barboriak DP, Allen NB, Ortel TL. vasculitis resistant to immunosuppressive treatment.

Antiphospholipid antibodies: findings at arteriography. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 59: 291–96.

AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998; 19: 611–16. 104 Sen ES, Leone V, Abinun M, et al. Treatment of primary angiitis

91 Rosen CL, DePalma L, Morita A. Primary angiitis of the central of the central nervous system in childhood with mycophenolate

nervous system as a first presentation in Hodgkin’s disease: a case mofetil. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010; 49: 806–11.

report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 2000; 46: 1504–08. 105 Holle JU, Gross WL. Neurological involvement in Wegener’s

92 Borenstein D, Costa M, Jannotta F, Rizzoli H. Localized isolated granulomatosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2011; 23: 7–11.

angiitis of the central nervous system associated with primary

intracerebral lymphoma. Cancer 1988; 62: 375–80.

www.thelancet.com Vol 380 August 25, 2012 777

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5806)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Victorian Alphabets, Monograms and Names For Needleworkers - From Godey's Lady's Book and Peterson's Magazine (PDFDrive)Document113 pagesVictorian Alphabets, Monograms and Names For Needleworkers - From Godey's Lady's Book and Peterson's Magazine (PDFDrive)sheidi100% (4)

- Study Notes - SOR - BaptismDocument8 pagesStudy Notes - SOR - BaptismYousef Yohanna100% (1)

- Hammer Pulse TempDocument12 pagesHammer Pulse Temppeter911cm100% (1)

- SSC CHSL Study Schedule For Tier I - Crack The Exam in 3 Weeks!Document3 pagesSSC CHSL Study Schedule For Tier I - Crack The Exam in 3 Weeks!Tushita80% (15)

- B2 Unit 4 Reading Plus LessonDocument2 pagesB2 Unit 4 Reading Plus LessonIruneNo ratings yet

- Ghost Hawk ExcerptDocument48 pagesGhost Hawk ExcerptSimon and SchusterNo ratings yet

- Nature. Association Between Clinical and Laboratory Markers and 5-Year Mortality Among Patients With Stroke. 2019Document10 pagesNature. Association Between Clinical and Laboratory Markers and 5-Year Mortality Among Patients With Stroke. 2019Nicolas RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Anemia in Young Patients With Ischaemic Stroke2015Document6 pagesAnemia in Young Patients With Ischaemic Stroke2015Nicolas RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Cancer y Stroke 2015Document7 pagesCancer y Stroke 2015Nicolas RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Struger WeberDocument6 pagesStruger WeberNicolas RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Creutzfeldt JakobDocument15 pagesCreutzfeldt JakobNicolas RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Central Pontine Myelinolysis and The Osmotic Demyelination 2021Document10 pagesCentral Pontine Myelinolysis and The Osmotic Demyelination 2021Nicolas RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Nec Exhibition BrochureDocument4 pagesNec Exhibition BrochurejppullepuNo ratings yet

- Basic Electrical Engg Kee 101Document3 pagesBasic Electrical Engg Kee 101SHIVAM BHARDWAJNo ratings yet

- Biodata Arnel For Yahweh GloryDocument2 pagesBiodata Arnel For Yahweh GloryClergyArnel A CruzNo ratings yet

- The Need For Culturally Relevant Dance EducationDocument7 pagesThe Need For Culturally Relevant Dance Educationajohnny1No ratings yet

- Tourism in India: Service Sector: Case StudyDocument16 pagesTourism in India: Service Sector: Case StudyManish Hemant DatarNo ratings yet

- FRC Team 2637, Phatnom Catz, Techbinder 2023 - 2024 CrescendoDocument17 pagesFRC Team 2637, Phatnom Catz, Techbinder 2023 - 2024 CrescendoShrey Agarwal (Drago Gaming)No ratings yet

- Chem ReviseDocument206 pagesChem ReviseAmir ArifNo ratings yet

- International Human Resource ManagementDocument24 pagesInternational Human Resource ManagementBharath ChootyNo ratings yet

- Holy Is The Lord-GDocument1 pageHoly Is The Lord-Gmolina.t4613No ratings yet

- Candi MerakDocument2 pagesCandi MerakEdi YantoNo ratings yet

- Second SundayDocument6 pagesSecond SundayAlfred LochanNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER - 7 Managing Growth and TransactionDocument25 pagesCHAPTER - 7 Managing Growth and TransactionTesfahun TegegnNo ratings yet

- CV EnglishDocument1 pageCV EnglishVijay AgrahariNo ratings yet

- Short VowelDocument3 pagesShort VowelNidzar ZulfriansyahNo ratings yet

- CHN ReportingDocument24 pagesCHN ReportingMatth N. ErejerNo ratings yet

- Ebf Rehearsal RubricDocument1 pageEbf Rehearsal Rubricapi-518770643No ratings yet

- U59cbu5f97u897fu5c71u5bb4u904au8a18-U6307u5b9au6587u8a00u7d93u5178u7cbeu7de8u53c3u8003u7b54u6848.docx - 1 10 (Document1 pageU59cbu5f97u897fu5c71u5bb4u904au8a18-U6307u5b9au6587u8a00u7d93u5178u7cbeu7de8u53c3u8003u7b54u6848.docx - 1 10 (Yo YuuiNo ratings yet

- General Rules ICT Lab Rules PE & Gym RulesDocument1 pageGeneral Rules ICT Lab Rules PE & Gym Rulestyler_froome554No ratings yet

- Friday HeatsDocument29 pagesFriday HeatsTGrasley6273No ratings yet

- PMLS 2 Unit 9Document3 pagesPMLS 2 Unit 9Elyon Jirehel AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Reading 2 - Julien Bourrelle - TranscriptDocument4 pagesReading 2 - Julien Bourrelle - TranscriptEmely BuenavistaNo ratings yet

- Clam Antivirus 0.100.0 User ManualDocument34 pagesClam Antivirus 0.100.0 User ManualJacobus SulastriNo ratings yet

- Performance APDocument29 pagesPerformance APMay Ann100% (1)

- How Does Texting Worsens Our Vocabulary & Writing Skills ?Document10 pagesHow Does Texting Worsens Our Vocabulary & Writing Skills ?Manvi GoelNo ratings yet