Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fundamentals of Valuation: Chapter One: Introduction

Uploaded by

Ahmed Reda0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views16 pagesThe valuation process involves 5 steps: 1) Understanding the business through industry and competitive analysis and financial statements. 2) Forecasting company performance through sales, earnings, and financial forecasts. 3) Selecting appropriate valuation models like present value or relative models. 4) Converting forecasts into a valuation using the model while considering sensitivity analysis and adjustments. 5) Applying the valuation conclusion for investment recommendations, transactions, or strategic investments. Understanding the business provides context for forecasting performance to determine a company or security's intrinsic value.

Original Description:

Original Title

Ch 1 P2

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe valuation process involves 5 steps: 1) Understanding the business through industry and competitive analysis and financial statements. 2) Forecasting company performance through sales, earnings, and financial forecasts. 3) Selecting appropriate valuation models like present value or relative models. 4) Converting forecasts into a valuation using the model while considering sensitivity analysis and adjustments. 5) Applying the valuation conclusion for investment recommendations, transactions, or strategic investments. Understanding the business provides context for forecasting performance to determine a company or security's intrinsic value.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views16 pagesFundamentals of Valuation: Chapter One: Introduction

Uploaded by

Ahmed RedaThe valuation process involves 5 steps: 1) Understanding the business through industry and competitive analysis and financial statements. 2) Forecasting company performance through sales, earnings, and financial forecasts. 3) Selecting appropriate valuation models like present value or relative models. 4) Converting forecasts into a valuation using the model while considering sensitivity analysis and adjustments. 5) Applying the valuation conclusion for investment recommendations, transactions, or strategic investments. Understanding the business provides context for forecasting performance to determine a company or security's intrinsic value.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 16

Fundamentals of Valuation

Chapter One: Introduction

The Valuation Process

In general, the valuation process involves the following five steps:

1. Understanding the business. Industry and competitive analysis, together with an

analysis of financial statements and other company disclosures, provides a basis for

forecasting company performance.

2. Forecasting company performance. Forecasts of sales, earnings, dividends, and

financial position (pro forma analysis) provide the inputs for most valuation models.

3. Selecting the appropriate valuation model. Depending on the characteristics of the

company and the context of valuation, some valuation models may be more

appropriate than others.

4. Converting forecasts to a valuation. Beyond mechanically obtaining the “output” of

valuation models, estimating value involves judgment.

5. Applying the valuation conclusions. Depending on the purpose, an analyst may use

the

valuation conclusions to make an investment recommendation about a particular stock,

provide an opinion about the price of a transaction, or evaluate the economic merits of a

potential strategic investment.

Understanding the Business

To forecast a company’s financial performance as a basis for determining the value

of an investment in the company or its securities, it is helpful to understand the

economic and industry contexts in which the company operates, the company’s

strategy, and the company’s previous financial performance. Industry and

competitive analysis, together with an analysis of the company’s financial reports,

provides a basis for forecasting performance.

Industry and Competitive Analysis

Because similar economic and technological factors typically affect all companies in

an industry, industry knowledge helps analysts understand the basic characteristics

of the markets served by a company and the economics of the company. An airline

industry analyst will know that labour costs and jet fuel costs are the two largest

expenses of airlines, and that in many markets airlines have difficulty passing

through higher fuel prices by raising ticket prices.

Understanding the Business

Analysts should try to understand industry structure—the industry’s

underlying economic and technical characteristics—and the trends affecting

that structure. Basic economic factors—supply and demand—provide a

fundamental framework for understanding an industry.

Porter’s (1985, 1998, 2008) five forces characterizing industry structure are

summarized below with an explanation of how that force could positively

affect inherent industry profitability. For each force, the opposite situation

would negatively affect inherent industry profitability.

i. Intra-industry rivalry. Lower rivalry among industry participants—for

example, in a faster growing industry with relatively few competitors and/or

good brand identification— enhances inherent industry profitability.

ii. New entrants. Relatively high costs to enter an industry (or other entry

barriers, such as government policies) result in fewer new participants and

less competition, thus enhancing inherent industry profitability.

Understanding the Business

iii. Substitutes. When few potential substitutes exist and/or the cost to switch to

a substitute is high, industry participants are less constrained in raising prices,

thus enhancing inherent industry profitability.

iv. Supplier power. When many suppliers of the inputs needed by industry

participants exist, suppliers have limited power to raise prices and thus would

not represent inherent downward pressure on industry profitability.

v. Buyer power. When many customers for an industry’s product exist, customers

have limited power to negotiate lower prices and thus would not represent

inherent downward pressure on industry profitability.

Understanding the Business

What is the company’s relative competitive position within its

industry, and what is its competitive strategy?

The level and trend of the company’s market share indicate its

relative competitive position within an industry. In general, a

company’s value is higher to the extent that it can create and sustain

an advantage relative to its competition. Porter identifies three

generic corporate strategies for achieving above-average

performance:

i. Cost leadership: being the lowest-cost producer while offering

products comparable to those of other companies, so that products

can be priced at or near the industry average;

Understanding the Business

ii. Differentiation: offering unique products or services

along some dimensions that are widely valued by buyers

so that the company can command premium prices; and

iii. Focus: seeking a competitive advantage within a target

segment or segments of the industry, based on either cost

leadership (cost focus) or differentiation (differentiation

focus).

Understanding the Business

Analysis of Financial Reports

The aspects of a financial report that are most relevant

for evaluating a company’s success in implementing

strategic choices vary across companies and industries.

For established companies, financial ratio analysis is

useful. Individual drivers of profitability for merchandising

and manufacturing companies can be evaluated against

the company’s stated strategic objectives.

Understanding the Business

Sources of Information

An important perspective on industry and competition is sometimes

provided by companies themselves in regulator-mandated disclosures,

regulatory filings, company press releases, investor relations

materials, and contacts with analysts. Analysts can compare the

information provided directly by companies to their own independent

research.

Company-provided sources of information in addition to regulatory

filings include press releases and investor relations materials. The

press releases of most relevance to analysts are the the ones that

companies issue to announce their periodic earnings.

Understanding the Business

Considerations in Using Accounting Information

In evaluating a company’s historical performance and developing

forecasts of future performance, analysts typically rely heavily on

companies’ accounting information and financial disclosures.

Companies’ reported results vary in their persistence, that is,

sustainability.

In addition, the information that companies disclose can vary

substantially with respect to the accuracy of reported accounting

results as reflections of economic performance and the detail in which

results are disclosed.

Forecasting Company Performance

The second step in the valuation process—forecasting company performance—

can be viewed from two perspectives: the economic environment in which the

company operates and the company’s own operating and financial

characteristics.

Companies do business within larger contexts of particular industries, national

economies, and world trade. Viewing a company within those larger contexts,

a top-down forecasting approach moves from international and national

macroeconomic forecasts to industry forecasts and then to individual

company and asset forecasts.

Selecting the Appropriate Valuation

Model

Detailed descriptions of the valuation models are presented in later readings.

Absolute valuation models and relative valuation models are the two broad types

of valuation models that incorporate a going-concern assumption. Here, we

describe absolute and relative valuation models in general terms and discuss a

number of issues in model selection.

In practice, an analyst may use a variety of models to estimate the value of a

company or its common stock.

absolute Valuation Models

An absolute valuation model is a model that specifies an asset’s intrinsic value.

Such models are used to produce an estimate of value that can be compared with

the asset’s market price.

The most important type of absolute equity valuation models are present value

models.

Selecting the Appropriate Valuation

Model

Relative Valuation Models

Relative valuation models constitute the second broad type of going-concern

valuation models. A relative valuation model estimates an asset’s value

relative to that of another asset. The idea underlying relative valuation is

that similar assets should sell at similar prices, and relative valuation is

typically implemented using price multiples (ratios of stock price to a

fundamental such as cash flow per share) or enterprise multiples (ratios of

the total value of common stock and debt net of cash and short-term

investments to certain of a company’s operating assets to a fundamental such

as operating earnings).

Converting Forecasts to a Valuation

Converting forecasts to valuation involves more than inputting the forecast

amounts to a model to obtain an estimate of the value of a company or its

securities. Two important aspects of converting forecasts to valuation are

sensitivity analysis and situational adjustments.

Sensitivity analysis is an analysis to determine how changes in an assumed

input would affect the outcome. Some sensitivity analyses are common to

most valuations. For example, a sensitivity analysis can be used to assess how

a change in assumptions about a company’s future growth—for example,

decomposed by sales growth forecasts and margin forecasts—and/or a change

in discount rates would affect the estimated value.

Situational adjustments may be required to incorporate the valuation impact

of specific issues. Three such issues that could affect value estimates are

control premiums, lack of marketability discounts, and illiquidity discounts.

Applying the Valuation Conclusion

As noted earlier, the purposes of valuation and the intended consumer of the

valuation vary:

• Analysts associated with investment firms’ brokerage operations are perhaps

the most visible group of analysts offering valuation judgments—their research

reports are widely distributed to current and prospective retail and institutional

brokerage clients.

Analysts who work at brokerage firms are known as sell-side analysts

(because brokerage firms sell investments and services to institutions such as

investment management firms).

In investment management firms, trusts and bank trust departments, and

similar institutions, an analyst may report valuation judgments to a portfolio

manager or to an investment committee as input to an investment decision.

Such analysts are widely known as buy-side analysts.

Thank You

You might also like

- Financial Statement Analysis: Business Strategy & Competitive AdvantageFrom EverandFinancial Statement Analysis: Business Strategy & Competitive AdvantageRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Chapter 07 Futures and OptiDocument68 pagesChapter 07 Futures and OptiLia100% (1)

- Fundamental Analysis Black BookDocument46 pagesFundamental Analysis Black Bookwagha25% (4)

- Michael Porter's Value Chain: Unlock your company's competitive advantageFrom EverandMichael Porter's Value Chain: Unlock your company's competitive advantageRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- CFA RC Equity Research Report EssentialsDocument3 pagesCFA RC Equity Research Report EssentialsSahil GoyalNo ratings yet

- KKR Overview and Organizational SummaryDocument73 pagesKKR Overview and Organizational SummaryRavi Chaurasia100% (3)

- Fundamental vs Technical Analysis Key DifferencesDocument12 pagesFundamental vs Technical Analysis Key DifferencesShakti ShuklaNo ratings yet

- ListDocument8 pagesListLuis RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Monetary EconomicsDocument14 pagesMonetary EconomicsMarco Antonio Tumiri López0% (3)

- Commercial Account FormDocument19 pagesCommercial Account FormSimonNo ratings yet

- Financial Statement Analysis, Balance Sheet, Income Statement, Retained Earnings StatementDocument51 pagesFinancial Statement Analysis, Balance Sheet, Income Statement, Retained Earnings StatementMara LacsamanaNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Analysis of ICICI BankDocument79 pagesFundamental Analysis of ICICI BanksantumandalNo ratings yet

- Unit 3Document21 pagesUnit 3InduSaran AttadaNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Analysis Principles, Types, and How To Use It $$$$$Document8 pagesFundamental Analysis Principles, Types, and How To Use It $$$$$ACC200 MNo ratings yet

- Company AnalysisDocument84 pagesCompany AnalysisShantnu SoodNo ratings yet

- Fundamental AnalysisDocument7 pagesFundamental AnalysisJyothi Kruthi PanduriNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Analysis Black BookDocument50 pagesFundamental Analysis Black Bookwagha100% (1)

- IUJ Math Aptitude Test - Sample 4Document7 pagesIUJ Math Aptitude Test - Sample 4Tigist TayeNo ratings yet

- Business ValuationDocument16 pagesBusiness Valuationsangya01No ratings yet

- RHB Account Terms and ConditionsDocument29 pagesRHB Account Terms and ConditionsLeong Liang TingNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Analysis of TATA MOTORSDocument4 pagesFundamental Analysis of TATA MOTORSNikher Verma100% (1)

- Fundamental Analysis: Stock Trading Analysis/IndicatorsDocument5 pagesFundamental Analysis: Stock Trading Analysis/IndicatorsAngie LeeNo ratings yet

- Equity Research - An Investment Advisory Service (Fundamental Analysis Approach)Document5 pagesEquity Research - An Investment Advisory Service (Fundamental Analysis Approach)rockyrrNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Analysis of ICICI BankDocument70 pagesFundamental Analysis of ICICI BankAnonymous TduRDX9JMh0% (1)

- WEALTH MANAGEMENT PROJECTDocument24 pagesWEALTH MANAGEMENT PROJECTshrishtiNo ratings yet

- Chapter Five Security Analysis and ValuationDocument66 pagesChapter Five Security Analysis and ValuationKume MezgebuNo ratings yet

- Strategy Consulting GuideDocument13 pagesStrategy Consulting Guideujjwal sethNo ratings yet

- Strategy and Consulting Domain: Gd-Pi Preparation CompendiumDocument13 pagesStrategy and Consulting Domain: Gd-Pi Preparation Compendiumujjwal sethNo ratings yet

- Equity ValuationDocument17 pagesEquity ValuationAadesh MunotNo ratings yet

- Business Valuation: Economic ConditionsDocument10 pagesBusiness Valuation: Economic ConditionscuteheenaNo ratings yet

- We TubeDocument38 pagesWe TubeGaurav ChikhalikarNo ratings yet

- Valuation of BusinessDocument9 pagesValuation of BusinessShiv SharmaNo ratings yet

- SAPM - Security AnalysisDocument7 pagesSAPM - Security AnalysisTyson Texeira100% (1)

- Fundamental of ValuationDocument39 pagesFundamental of Valuationkristeen1211No ratings yet

- Business ValuationDocument5 pagesBusiness ValuationPulkitAgrawalNo ratings yet

- What Is Vertical IntegrationDocument5 pagesWhat Is Vertical IntegrationNyadroh Clement MchammondsNo ratings yet

- RC Equity Research Report Essentials CFA InstituteDocument3 pagesRC Equity Research Report Essentials CFA InstitutetheakjNo ratings yet

- Reading 24 - Equity Valuation - Applications and ProcessesDocument5 pagesReading 24 - Equity Valuation - Applications and ProcessesJuan MatiasNo ratings yet

- Reviewer FMDocument8 pagesReviewer FMTHRISHIA ANN SOLIVANo ratings yet

- Fundamental AnalysisDocument4 pagesFundamental Analysisgabby209No ratings yet

- Fundamental Analysis of FMCG Companies. (New)Document67 pagesFundamental Analysis of FMCG Companies. (New)AKKI REDDYNo ratings yet

- Comparative IT Company ValuationDocument5 pagesComparative IT Company ValuationVarsha BhatiaNo ratings yet

- BBA5 Fundamental Analysis of Investment ManagementDocument7 pagesBBA5 Fundamental Analysis of Investment Managementgorang GehaniNo ratings yet

- Strategy - Chapter 3: Can A Firm Develop Strategies That Influence Industry Structure in Order To Moderate Competition?Document8 pagesStrategy - Chapter 3: Can A Firm Develop Strategies That Influence Industry Structure in Order To Moderate Competition?Tang WillyNo ratings yet

- Fundamental AnalysisDocument6 pagesFundamental Analysisumasahithi91No ratings yet

- Executive SummaryDocument63 pagesExecutive SummarymaisamNo ratings yet

- Strategy Is A Pattern of Activities That Seeks To Achieve The Objectives ofDocument5 pagesStrategy Is A Pattern of Activities That Seeks To Achieve The Objectives ofPriya NairNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Analysis 12Document5 pagesFundamental Analysis 12Pranay KolarkarNo ratings yet

- Product Management Unit IIIDocument32 pagesProduct Management Unit IIIKevinNo ratings yet

- MDI GDPI Prep - StrategyDocument10 pagesMDI GDPI Prep - StrategyDevavrat SinghNo ratings yet

- Presented by - Snibdhatambe, 11 Shreeti Daddha, 09 (Bvimsr)Document39 pagesPresented by - Snibdhatambe, 11 Shreeti Daddha, 09 (Bvimsr)Daddha ShreetiNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Analysis - WikipediaDocument21 pagesFundamental Analysis - WikipediaNaman JindalNo ratings yet

- The Industry AnalysisDocument6 pagesThe Industry AnalysisNicoleNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management Concepts ExplainedDocument9 pagesStrategic Management Concepts ExplainedAnil KumarNo ratings yet

- What Is Fundamental AnalysisDocument13 pagesWhat Is Fundamental AnalysisvishnucnkNo ratings yet

- Fundamental AnalysisDocument8 pagesFundamental AnalysisNiño Rey LopezNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Comparable Companies AnalysisDocument46 pagesChapter 6 Comparable Companies AnalysisLAMOUCHI RIMNo ratings yet

- AbcdDocument3 pagesAbcdAshwin NairNo ratings yet

- Marketing Management AssignmentDocument32 pagesMarketing Management Assignmentwerksew tsegayeNo ratings yet

- Reviewer Compre 1Document30 pagesReviewer Compre 1Dexter AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Efficient Market Hypothesis AssingmentDocument5 pagesEfficient Market Hypothesis AssingmentJohn P ReddenNo ratings yet

- Porter's Five Forces That Shape IndustryDocument8 pagesPorter's Five Forces That Shape IndustryLaong laanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5Document9 pagesChapter 5NadineNo ratings yet

- What Is 'Fundamental Analysis': Intrinsic Value Macroeconomic Factors Current PriceDocument9 pagesWhat Is 'Fundamental Analysis': Intrinsic Value Macroeconomic Factors Current Pricedhwani100% (1)

- Financial Statement Analysis Study Resource for CIMA & ACCA Students: CIMA Study ResourcesFrom EverandFinancial Statement Analysis Study Resource for CIMA & ACCA Students: CIMA Study ResourcesNo ratings yet

- The Pros and Cons of GrexitDocument4 pagesThe Pros and Cons of GrexitTanay ChitreNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1636Document30 pagesChapter 1636MJ39No ratings yet

- Snapshot Ed General Presentation DisclosuresDocument20 pagesSnapshot Ed General Presentation DisclosuresAsad MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Assigment Financial ManagementDocument5 pagesAssigment Financial ManagementMuhammad A IsmaielNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Evolution and Fundamental of BusinessDocument211 pagesChapter 1 Evolution and Fundamental of BusinessDr. Nidhi KumariNo ratings yet

- Booking 1062381456Document2 pagesBooking 1062381456Deni SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Intermediate Accounting IFRS Edition: Kieso, Weygandt, WarfieldDocument20 pagesIntermediate Accounting IFRS Edition: Kieso, Weygandt, Warfielddystopian au.No ratings yet

- Musharaka Accounting AgendaDocument32 pagesMusharaka Accounting AgendamohamedNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Textbook NotesDocument16 pagesChapter 1 Textbook NotesAhmed SohailNo ratings yet

- 22 2Q Earning Release of LGEDocument18 pages22 2Q Earning Release of LGEThảo VũNo ratings yet

- Circular No. 102-2012-TT-BTC - Per-Diem For Overseas Business Trip - ENGDocument20 pagesCircular No. 102-2012-TT-BTC - Per-Diem For Overseas Business Trip - ENGLê Đình ChinhNo ratings yet

- Mobile Services: Your Account Summary This Month'S ChargesDocument2 pagesMobile Services: Your Account Summary This Month'S ChargesShahidNo ratings yet

- Makalah Bahasa Inggris-1Document8 pagesMakalah Bahasa Inggris-1NajwaNo ratings yet

- Acct Statement - XX6419 - 08112022Document26 pagesAcct Statement - XX6419 - 08112022AartiNo ratings yet

- Investing in Fixed Income SecuritiesDocument16 pagesInvesting in Fixed Income Securitiescao cao100% (1)

- Account Management Agreement - Agreed Form 18mar11-1Document17 pagesAccount Management Agreement - Agreed Form 18mar11-1UltimanoticiasNo ratings yet

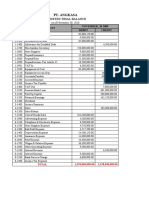

- Kerja Kelompok PT Angkasa BDocument28 pagesKerja Kelompok PT Angkasa BElisa EndrianiiNo ratings yet

- Gov't Assistance, Subsidies, & Impacts on BusinessDocument12 pagesGov't Assistance, Subsidies, & Impacts on BusinessHassaan UmerNo ratings yet

- Pro Forma Balance Sheet Template: Company NameDocument5 pagesPro Forma Balance Sheet Template: Company NamePhương ĐinhNo ratings yet

- Accounts - Module 2 Books and Trial BalanceDocument18 pagesAccounts - Module 2 Books and Trial Balance9986212378No ratings yet

- IS Milan New Student Fees 23 24Document1 pageIS Milan New Student Fees 23 24Bharani DhanasekarNo ratings yet

- Cigicon 2015 BrochureDocument2 pagesCigicon 2015 Brochuredrjas007No ratings yet

- Financial Management Test 1 - DistanceDocument2 pagesFinancial Management Test 1 - DistancePdoneeverNo ratings yet