Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Seminar 6 Полещук Елена

Seminar 6 Полещук Елена

Uploaded by

Елена Полещук0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

30 views11 pagesThe document summarizes key aspects of adjectives. It discusses:

1) Semantic and morphological features of adjectives, including how they express properties and relate to nouns or verbs.

2) Classification of adjectives, including semantic categories like qualitative vs. relative, and syntactic categories like attributive vs. predicative.

3) Formation of degrees of comparison, including synthetic, analytic, and suppletive forms.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe document summarizes key aspects of adjectives. It discusses:

1) Semantic and morphological features of adjectives, including how they express properties and relate to nouns or verbs.

2) Classification of adjectives, including semantic categories like qualitative vs. relative, and syntactic categories like attributive vs. predicative.

3) Formation of degrees of comparison, including synthetic, analytic, and suppletive forms.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

30 views11 pagesSeminar 6 Полещук Елена

Seminar 6 Полещук Елена

Uploaded by

Елена ПолещукThe document summarizes key aspects of adjectives. It discusses:

1) Semantic and morphological features of adjectives, including how they express properties and relate to nouns or verbs.

2) Classification of adjectives, including semantic categories like qualitative vs. relative, and syntactic categories like attributive vs. predicative.

3) Formation of degrees of comparison, including synthetic, analytic, and suppletive forms.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 11

Seminar 6

1. General outline of the adjective.

1. Semantic features. The adjective expresses the property of an entity. Typically,

adjectives denote states, usually permanent states, although there are also adjectives

that can denote temporary states. Adjectives are characteristically stative, but many of

them can be seen as dynamic. The stative property of an entity is a property that

cannot be conceived as a developing process, and the dynamic property of an entity is

a property that is conceived as active, or as a developing process. E.g.: Mary is

thoughtful. vs. Mary is being thoughtful today.

Mary is very thoughtful today (unemphatic). vs. Mary is being thoughtful today

(emphatic).

2. Morphological features. Adjectives are related either to nouns or verbs. Suffixes

changing nouns to adjectives are: - (i)al (essential), -ar (familiar), -ary (ordinary) or –

ery (quarterly), -ed (unemployed), -en (sudden), -esque (arabesque), -ful (wonderful),

-ic(al) (critical), -ish (childish), -istic (realistic), -less (poweless), -like (childlike), -ly

(early), -ous (dangerous), -ward (inward), -wide (worldwide), -y (busy). Suffixes

changing verbs to adjectives are: -able (variable) or –ible (irresistible), -ent

(excellent) or –ant (pleasant), -ed (faded), -ing (interesting), -ive (impressive), -

(at)ory (mandatory).

3. Syntactic features. In the sentence, the adjective performs the functions of an

attribute (an adjunct) and a predicative. The more typical function is that of an

attribute since the function of a predicative can also be performed by other parts of

speech.

Adjectives can sometimes be postpositive, that is, they can sometimes follow the item

they modify. Adjectives can often function as heads of noun phrases. They do not

inflect for number and for the genitive case and must take a definite determiner.

An adjective can function as a verbless clause (E.g. Anxious, he dialed the

number).

2. Classification of adjectives.

Semantic classification. All the adjectives are traditionally divided into two large

subclasses: qualitative and relative. Relative adjectives express such properties of a

substance as are determined by the direct relation of the substance to some other

substance. E.g. mathematics — mathematical precision; history — a historical event.

Qualitative adjectives, as different from relative ones, denote various qualities of

substances which admit of a quantitative estimation, i.e. of establishing their

correlative quantitative measure. The measure of a quality can be estimated as high or

low, sufficient or insufficient, optimal or excessive.

However, in actual speech the described principle of distinction is not strictly

observed. Substances can possess qualities that are incompatible with the idea of

degrees of comparison. So adjectives denoting these qualities and incapable of

forming degrees of comparison still belong to the qualitative subclass (extinct,

immobile, deaf, final, fixed, etc.) On the other hand, some relative adjectives can

form degrees of comparison. Prof. Blokh suggests that all the adjective functions may

be grammatically divided into "evaluative" and "specificative". One and the same

adjective, irrespective of its being "relative" or "qualitative", can be used either in the

evaluative function or in the specificative function. For instance, the adjective good is

basically qualitative. On the other hand, when employed as a grading term in

teaching, so together with the grading terms bad, satisfactory, excellent, it acquires

the said specificative value; in other words, it becomes a specificative, not an

evaluative unit in the grammatical sense. Conversely, the adjective wooden is

basically relative, but when used in the broader meaning "expressionless" or

"awkward" it acquires an evaluative force and can presuppose a greater or lesser

degree ("amount") of the denoted properly in the corresponding referent.

Adjectives that characterize the referent of the noun directly are termed inherent,

those that do not are termed non-inherent. E.g.: a fresh leaf of tea– the leaf of tea is

fresh

Most adjectives are inherent, and it is especially uncommon for dynamic adjectives to

be other than inherent.

Syntactic classification. From a syntactic point of view, adjectives can be divided into

three groups:

1) adjectives which can be used attributively and predicatively (a healthy man – the

man is healthy);

2) adjectives which can be used attributively only (a complete idiot – *the idiot is

complete);

3) adjectives which can be used predicatively only (*a loath man – the man is loath to

agree with it).

Attributive adjectives constitute two groups: 1) intensifying;

2) restrictive, or particularizing (limiter adjectives).

Intensifying adjectives constitute two groups: 1) emphasizers;

2) amplifiers.

Emphasizers have a heightening effect on the noun (clear, definite, outright, plain,

pure, real, sheer, sure, true); amplifiers scale upwards from an assumed norm

(complete, great, firm, absolute, close, perfect, extreme, entire, total, utter).

Restrictive adjectives restrict the noun to a particular member of the class (chief,

exact, main, particular, precise, principal, sole, specific). They particularize the

reference of the noun.

3. The category of adjectival comparison.

The category of comparison is constituted by the opposition of three forms of the

adjective: the positive, the comparative, and the superlative.

There are three ways of forming degrees of comparison: synthetic, analytic, and

suppletive.

The synthetic way of forming degrees of comparison is by the inflections -er, -est; the

analytic way, by placing more and most before the adjective. The synthetic way is

generally used with monosyllabic adjectives and dissyllabic adjectives ending in -y, -

ow, -er, -le and those which have the stress on the last syllable. However, in the

dissyllabic group we can observe radical changes: adjectives formerly taking -er and -

est are tending to go over to more and most , e.g. more common, most common; more

cloudy, most cloudy; more fussy, most fussy; more cruel, most cruel; more quiet,

most quiet; more clever, most clever; more profound, most profound; more simple,

most simple; more pleasant, most pleasant.

All this goes to show that English comparison is getting more and more analytic. As

already pointed out, the third way of forming degrees of comparison is by the use of

suppletive forms: good _ better, best; bad _ worse, worst; far _farther/further,

farthest/furthest; little _ less, least; much/many _ more, most.

4.Specific nature of adjectives of participial origin.

Another major subclass of adjectives can also be formally distinguished by endings,

this time by -ed or -ing endings:

-ed form: computerized, determined, excited, misunderstood, renowned, self-centred,

talented, unknown;

-ing form: annoying, exasperating, frightening, gratifying, misleading, thrilling, time-

consuming, worrying;

Adjectives with -ed or -ing endings are known as participal adjectives, because they

have the same endings as verb participles (he was training for the Olympics, he had

trained for the Olympics). In some cases there is a verb which corresponds to these

adjectives (to annoy, to computerize, to excite, etc), while in others there is no

corresponding verb (to renown, to self-centre, to talent). Like other adjectives,

participial adjectives can usually be modified by very, extremely, or less (very

determined, extremely self-centred, less frightening, etc). They can also take more

and most to form comparatives and superlatives (annoying, more annoying, most

annoying). Finally, most participial adjectives can be used both attributively and

predicatively:

Attributive Predicative

That's an interesting film That film is intresting

That was an exciting trip That trip was exciting

He's an experienced teacher That teacher is experienced

Many participial adjectives, which have no corresponding verb, are formed by

combining a noun with a participle:

alcohol-based chemicals;

battle-hardened soldiers;

drug-induced coma;

energy-saving devices;

fact-finding mission;

purpose-built accommodation.

When participial adjectives are used predicatively, it may sometimes be difficult to

distinguish between adjectival and verbal uses:

[1] the workers are striking. In the absence of any further context, the grammatical

status of striking is indeterminate here. The following expansions illustrate possible

adjectival [1a] and verbal [1b] readings of [1]: [1a] the workers are very striking in

their new uniforms (=`impressive', `conspicuous') [1b] the workers are striking

outside the factory gates (=`on strike')

Adjectival

This film is terrifying

Your comments are alarming

The defendant's answers were misleading

Verbal

This film is terrifying the children

Your comments are alarming the people

The defendant's answers were misleading the jury

Discriminating between adjectival and verbal constructions is sometimes facilitated

by the presence of additional context, such as by-agent phrases or adjective

complements. However, when none of these indicators is present, grammatical

indeterminacy remains. With -ed and -ing participial forms, there is no grammatical

indeterminacy if there is no corresponding verb. For example, in the job was time-

consuming, and the allegations were unfounded, the participial forms are adjectives.

Similarly, the problem does not arise if the main verb is not be. For example, the

participial forms in this book seems boring, and he remained offended are all

adjectives. E.g.: John was depressed/John felt depressed.

5. Patterns of combinability of adjectives.

Adjectives are combined with several parts of speech.

1) They may combine with nouns, which they may premodify or postmodify: a black

dress, a chivalrous gentleman, the delegates present. If there are several premodifying

adjectives to one headword they have definite positional assignments. Generally

descriptive adjectives precede the limiting ones, as in a naughty little boy, a beautiful

French girl, but il there are several of each type, adjectives of different meanings

stand like, for example, a large black and white hunting dog, a small pale green oval

seed.

This order of words is of course not absolutely fixed, since many adjectives may be

either descriptive or limiting, depending on the context. The adjectives are not

separated by commas, unless they belong to the same type: a nice little old man.

However, if there is more than one adjective of the same type they are separated by

commas: nasty, irritable, selfish man (all three belong to the type of ‘judgement or

general characterization’).

In several noun-phrases of French origin (mostly legal or quasilegal) the adjective is

postpositional. Examples: attorney general heir apparent time immemorial body

politic Queen Regnant Lords Spiritual (Temporal).

These noun-phrases are very similar to compounds and some of them are spelt as a

compound, with a hyphen (knight-errant, postmaster-general). The plural ending is

attached either to the first element, or to the second: Examples: court-martials

postmaster-general, courts-martial postmasters-general.

Postmodification may be due to the structural complexity of postmodifiers (the

children easiest to teach, the climate peculiar to this country), or to the presence of

only or all in preposition (the only actor suitable, the only person visible, all the

money available).

2) Beside their usual function, that of modifying nouns, adjectives may be combined

with other words in the sentence. They may be modified by adverbials of degree, like

very, quite, that, rather, most, a lot, a sort of, a bit, enough, totally, perfectly, so... as:

very long, a bit lazy, sort of naive, far enough, a little bit tired, a most beautiful

picture, not so foolish as that, she is not that crazy.

The adverb very can combine only with adjectives denoting the gradable properties.

Thus it is possible to say very tired (tiredness may be of different degree), but it is

impossible to say very unknown, very ceaseless, very unique, as these adjectives do

not allow of gradation. With the adverb too the indefinite article is placed between

the adjective and the head-noun. With the adverb rather the article is placed after it:

E.g.: This is too difficult a problem to solve at once. This is rather a complicated

matter.

3. Predicative adjectives are combined with the link verbs to be, to seem, to appear, to

look, to turn, or notional verbs in a double predicate:

E.g.: He looks tired. She does not seem so crazy as before. She is quite healthy. She

felt faint. If sounded rather fussy. The food tasted good. The flowers smell sweet.

6. Syntactic functions of adjectives.

Syntactically adjectives may function both as 1) attributes and 2) predicatives, i.e.

parts of the predicate. Here are the examples of the attributive use: She returned in

the early morning. After careful consideration, we accepted the offer. Trying to

conceal her embarrassment she turned away her red face.

Sometimes adjectives used attributively may occur in postposition, i.e. after the noun

they describe: This is the only possible answer. — This is the only answer possible.

In some cases the postpositional use of adjectives is obligatory: I'll do everything

possible to help you.When used predicatively, adjectives are combined with link-

verbs: be, feel, get, grow, look, seem, smell, taste, turn. For instance: I was early for

work today. When driving he is always careful. They feel nervous. He looked happy.

Honey tastes sweet. She turned red with embarrassment.Such adjectives as long,

high, wide, deep, etc. find themselves in predicative position together with nouns

denoting periods of time and units for measuring height, length and so on. For

example: The garden is 20 meters long and 15 meters wide. The well is 25 meters

deep.

The most frequently recurrent link-verb is the verb to be which enters a considerable

number of set expressions of adjective + preposition type: be ready for/with, be fond

of, be late for, be jealous of, be happy about, be afraid of, be frightened of, be

dependent on, be persistent in, be grateful to/for, be angry with, be certain about/of,

be suspicious of, etc. The predicative function of the adjectival collocations is often

supported by their synonymous verbal counterparts be fond of— love, be grateful

to/for — thank, be suspicious of— suspect of.

The predicative function may be performed by double comparative forms of

adjectives in the elliptical (or predicatively incomplete sentences with missing verbal

elements): The more expensive the hotel, the better the service. (The more expensive

the hotel is...) The warmer the weather the better I feel.

Adjectives with the a- prefix like afire, afloat, agape, ajar, akin, etc. usually function

predicatively: The house was aflame. The company somehow managed to keep

afloat. The problem facing him is akin to that of ours. However, in some rare cases,

they may be used attributively: He got down to work afire with enthusiasm.

7. Peculiarities of substantivised adjectives.

Substantivized adjectives have acquired some or all of the characteristics of the noun,

but their adjectival origin is still generally felt.

Substantivized adjectives are divided into wholly substantivized and partially

substantivized adjectives. Wholly substantivized adjectives have all the

characteristics of nouns, namely the plural form, the genitive case; they are associated

with articles, i. e. they have become nouns: a native, the natives, a native's hut. Some

wholly substantivized adjectives have only the plural form: eatables, valuables,

ancients, sweets, greens.

Partially substantivized adjectives acquire only some of the characteristics of the

noun; they are used with the definite article. Partially substantivized adjectives denote

a whole class: the rich, the poor; the unemployed. They may also denote abstract

notions: the good, the evil, the beautiful, the singular, the plural, the future, the

present, the past.

Substantivized adjectives denoting nationalities fall under wholly and partially

substantivized adjectives. Wholly substantivized adjectives are: a Russian —

Russians, a German — Germans. Partially substantivized adjectives are: the English,

the French, the Chinese.

8. Morphological composition of numerals.

The Cardinals

Among the cardinals there are simple, derived, and compound words. The cardinals

from one to twelve, hundred, thousand, million are simple words; those from thirteen

to nineteen are derived from the corresponding simple ones by means of the suffix -

teen; the cardinals denoting fens are derived from the corresponding simple ones by

means of the suffix -ty.

The cardinals from twenty-one to twenty-nine, from thirty-one to thirty-nine, etc. and

those over hundred are compounds. In cardinals consisting of tens and units the two

words are hyphenated: 21 - twenty-one, 35 - thirty-five, 72 - seventy-two, etc.

In cardinals including hundreds and thousands the words denoting units and tens are

joined to those denoting hundreds, thousands, by means of the conjunction and: 103 -

one hundred and three, 225 - two hundred and twenty-five, 3038 - three thousand and

thirty-eight, 9651 - nine thousand six hundred and fifty-one.

The words for common fractions are also composite. They are formed from cardinals

denoting the numerator and substantivized ordinals denoting the denominator. If the

numerator is a numeral higher than one, the ordinal in the denominator takes the

plural form. The numerator and denominator may be joined by means of a hyphen or

without it: 1/3 - one-third (one third), 2/7 - two-sevenths (two sevenths), etc.

In mixed numbers, the numerals denoting fractions are joined to the numerals

denoting integers (whole numbers) by means of the conjunction and: 3 1/5 - three and

one-fifth, 20 3/8 - twenty and three-eighths.

In decimal fractions the numerals denoting fractions are joined to those denoting

whole numbers by means of the words point or decimal: 0.5 - zero point (decimal)

five, 2.3 - two point (decimal) three, 0,5 - zero decimal five, 0,005 - zero decimal

zero zero five.

The ordinals

Among the ordinals there are also simple, derivative and compound words. The

simple ordinals are first, second and third. The derivative ordinals are derived from

the simple and derivative cardinals by means of the suffix -th: four-fourth, ten-tenth,

sixteen-sixteenth, twenty-twentieth, etc. Before the suffix -th the final у is replaced

by ie: thirty - thirtieth, etc.

The compound ordinals are formed from composite cardinals. In this case only the

last component of the compound numeral has the form of the ordinal: twenty-first,

forty-second, sixty-seventh, one hundred and first, etc.

9. Morphological characteristics of numerals.

If we speak about morphological characteristics, the numerals do not undergo any

morphological changes, that is, they do not have morphological categories. In this,

they differ from nouns with numerical meaning. Thus, the numerals ten, hundred,

thousand do not have plural forms: two hundred and fifty, four thousand people, etc.,

whereas the corresponding homonymous nouns ten, hundred, thousand to tens,

hundreds of people, thousands of birds, etc. Numerals combine mostly with nouns

and function as their attributes, usually as premodifying attributes. If a noun has

several premodifying attributes including a cardinal or an ordinal, these come first, as

in: three tiny green leaves, seven iron men, the second pale little boy, etc.

If both a cardinal and an ordinal refer to one head-noun the ordinal comes first: In

English: the first three tall girls, the second two grey dogs, etc.

Nouns premodified by ordinals are used with the definite article: The first men in the

moon, the third month, etc. When used with the indefinite article, they lose their

numerical meaning and acquire that of a pronoun (another, one more), as in English:

a second man entered.

Postmodifying numerals combine with a limited number of nouns.

Postmodifying cardinals are combinable with some nouns denoting items of certain

sets of things: pages, paragraphs, chapters, parts of books, acts and scenes of plays,

lessons in textbooks, apartments and rooms, buses or trams (means of transport),

grammatical terms, etc.;

In such cases the cardinals have a numbering meaning and thus differ semantically

from the ordinals which have an enumerating meaning. Enumeration indicates the

order of a thing in a certain succession of things, while numbering indicates a number

constantly attached to a thing either in a certain succession or in a certain set of

things. Thus, the first room (enumeration) is not necessarily room one (numbering),

etc. Compare: the first room I looked into was room five, or the second page that he

read was page twenty-three, etc. Postmodifying ordinals occur in combinations with

certain proper names, mostly those denoting the members of well-known dynasties:

King Henry VIII — King Henry the Eighth, Peter I — Peter the First, etc. As

headwords modified by other words numerals are combinable with prepositional

phrases: the first of May, one of the men, two of them, etc.

10. Patterns of combinability of numerals.

Numerals combine mostly with nouns and function as their attributes, usually as

premodifying attributes. If a noun has several premodifying attributes including a

cardinal or an ordinal, these come first, as in: three tiny green leaves, seven iron men,

the second pale little boy, etc.

The only exception is pronoun determiners, which always begin a series of attributes:

his second beautiful wife; these four rooms; her three little children; every second

day, etc.

If both a cardinal and an ordinal refer to one head-noun the ordinal comes first: the

first three tall girls, the second two grey dogs, etc.

Nouns premodified by ordinals are used with the definite article: The first men in the

moon, the third month, etc.

When used with the indefinite article, they lose their numerical meaning and acquire

that of a pronoun (another, one more), as in: a second man entered, then a third.

Postmodifying numerals combine with a limited number of nouns. Postmodifying

cardinals are combinable with some nouns denoting items of certain sets of things:

pages, paragraphs, chapters, parts of books, acts and scenes of plays, lessons in

textbooks, apartments and rooms, buses or trams (means of transport), grammatical

terms, etc.; room two hundred and three, page ten, bus four, participle one, etc.

Postmodifying ordinals occur in combinations with certain proper names, mostly

those denoting the members of well-known dynasties: King Henry VIII - King Henry

the Eighth, Peter I - Peter the First, etc.

As headwords modified by other words numerals are combinable with:

1) prepositional phrases: the first of May, one of the men, two of them, etc.

2) pronouns: every three days, all seven, each fifth, etc.

3) adjectives: the best three of them, the last two weeks, etc.

4) particles: just five days ago, only two, only three books, he is nearly sixty, etc.

11. Syntactic function of numerals.

Ordinal numerals are used as attributes.

"No, this is my first dance," she said.

Almost immediately the band started, and her second partner seemed to spring from

the ceiling.

... the young man opposite had long since disappeared. Now the other two got out.

(subject)

Earle Fox was only fifty-four, but he felt timeless and ancient. (predicative)

And again she saw them, but not four, more like forty laughing, sneering, jeering ...

(object)

At eight the gong sounded for supper. (Mansfield) (adverbial modifier)

Cardinals are sometimes used to denote the place of an object in a series.

... but from the corner of the street until she came to No. 26 she thought of those four

flights of stairs.

Exercises.

ex. 1 Give the forms of degrees of comparison and state whether they are formed in a

synthetic, analytical or suppletive way,

a) wet - wetter - wettest (synthetic);

merry - merrier - the merriest (synthetic);

real - more real - the most real (analytical);

far - farther - the farthest (suppletive);

b) kind-hearted - more kind-hearted - the most kind-hearted (analytical);

shy - shyer - the shyest (synthetic);

little - less - the least (suppletive);

friendly - friendlier - the friendliest (synthetic);

c) certain - more certain - the most certain (analytical);

comical - more comical - the most comical (analytical);

severe - severer - the severest (synthetic);

well-off - more well-off - the most well-off (analytical);

d) sophisticated - more sophisticated - the most sophisticated (analytical);

clumsy - clumsier - the clumsiest (synthetic);

old-fashioned - more old-fashioned - the most old-fashioned (analytical);

good-looking - more good-looking - the most good-looking (analytical).

ex. 2 Give the Russian equivalents for the English word combinations:

iron rations - сухой паёк

iron foundry (ironworks) - чугунолитейный (металлургический завод)

iron industry - металлургическая промышленность

ironware (iron mongery) - скобяной товар (железные изделия)

ferrous metal - черные металлы

ferrous oxide - оксиды железа

celestial map - небесная карта

sky-force - воздушные силы

celestial food - пища богов

sky-line - линия горизонта

skyway - эстакада

celestial navigation - астронавигация

sea-cock - морской петух

dog-fish - катран (акула)

echinus - эхинус (морской еж)

sea-boy - юнга

sea-water - морская вода

naval base - военно-морская база

"sea dog" - морской пес (бывалый моряк)

Admiralty - адмиралтейство (морское министерство)

Admiralty mile

sea-hedgehog - морской еж

starfish - морская звезда

sea-horse - морской конек

sea-dye - краситель морской воды (спасательое средство)

grass-wrack - рдестовые (вид водных растений)

sea kale - морская капуста

"old salt" - морской волк (опытный моряк, рассказчик историй)

sea-cliff - прибрежная скала

sea-cow - морская корова

sea-lane - морской маршрут

You might also like

- Morphological ProcessesDocument19 pagesMorphological ProcessesLuqman HakimNo ratings yet

- Heavy Equipment Rental in The US Industry Report 53241Document53 pagesHeavy Equipment Rental in The US Industry Report 53241paozinNo ratings yet

- Chippewa Park Master Plan ReportDocument28 pagesChippewa Park Master Plan ReportinforumdocsNo ratings yet

- Noun SuffixesDocument94 pagesNoun SuffixesEdz SoretsellaBNo ratings yet

- 14-The Expression of QualityDocument12 pages14-The Expression of QualityJccd JccdNo ratings yet

- AdjectivesDocument15 pagesAdjectivesMarija Blagojevic100% (5)

- Canal RegulatorDocument13 pagesCanal RegulatorBibhuti Bhusan Sahoo100% (1)

- Теоретическая грамматика госDocument10 pagesТеоретическая грамматика госДарья ОчманNo ratings yet

- Massey Furguson Mf4707, Mf4708, Mf5709, Mf5710, Mf6710, Mf6711, Mf6712, Mf6713 - Manual de Partes - Pag-86Document86 pagesMassey Furguson Mf4707, Mf4708, Mf5709, Mf5710, Mf6710, Mf6711, Mf6712, Mf6713 - Manual de Partes - Pag-86Manuales De Maquinaria Jersoncat100% (3)

- English Morphology ExercisesDocument14 pagesEnglish Morphology ExercisesStef Gabriela100% (1)

- AdjectivesDocument16 pagesAdjectivestheoNo ratings yet

- Topic 14 The Quality, Degree and ComparisonDocument41 pagesTopic 14 The Quality, Degree and Comparisonmaria C nuñezNo ratings yet

- Heliαseries Parts List-65Document2 pagesHeliαseries Parts List-65MatheusNo ratings yet

- Bp344 Comments On BP 344 Irr Amendments Complete Part 2 July10 2013Document28 pagesBp344 Comments On BP 344 Irr Amendments Complete Part 2 July10 2013ShanaynayNo ratings yet

- Lecture 12adjectivesDocument12 pagesLecture 12adjectivesAlex CireşNo ratings yet

- THEME 14: The Expression of Quality, Degree and ComparisonDocument17 pagesTHEME 14: The Expression of Quality, Degree and ComparisonminimunhozNo ratings yet

- Limba Engleza ContemporanaDocument20 pagesLimba Engleza ContemporanaGal12No ratings yet

- Lecture 5Document6 pagesLecture 5安思吉No ratings yet

- Parts of Speech-Chapter2Document31 pagesParts of Speech-Chapter2نبيل العساليNo ratings yet

- Unit 14 Ta Ündem Formacio ÜnDocument11 pagesUnit 14 Ta Ündem Formacio Ünsergio ruizherguedasNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations: Words: y Ly Er Est More MostDocument1 pageChapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations: Words: y Ly Er Est More MostAlex MurrayNo ratings yet

- Common Transitional Words and PhrasesDocument5 pagesCommon Transitional Words and PhrasesArianne Kate BorromeoNo ratings yet

- Tema 5 SemanticaDocument5 pagesTema 5 SemanticaMaria Garcia GuardaNo ratings yet

- სტრუქტურა ფინალურიDocument13 pagesსტრუქტურა ფინალურიMaria AlvanjyanNo ratings yet

- AdjectivesDocument6 pagesAdjectivesahmadmuhammadamasNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Grammar NotesDocument9 pagesTheoretical Grammar NoteslenaaalifeNo ratings yet

- Parts of SpeechDocument8 pagesParts of SpeechPilar AuserónNo ratings yet

- Adjectives Lec2019Document5 pagesAdjectives Lec2019Aku-Jalmari syrjäNo ratings yet

- Seminar 4Document13 pagesSeminar 4Михаил РешетниковNo ratings yet

- Chapter V The AdjectiveDocument5 pagesChapter V The AdjectivenidisharmaNo ratings yet

- Class Ing CDocument8 pagesClass Ing CDarl Ath ArNo ratings yet

- Principles of Classification of WordsDocument26 pagesPrinciples of Classification of WordsJohn AngolluanNo ratings yet

- 2.3 Adjectives and The Adjective Phrase: Pretty)Document7 pages2.3 Adjectives and The Adjective Phrase: Pretty)smile1891No ratings yet

- 2018 Sem 4 1 READER AdjectiveDocument8 pages2018 Sem 4 1 READER AdjectiveDmitry KalnovNo ratings yet

- Adjectives Determinatives and NumeralsDocument12 pagesAdjectives Determinatives and Numeralsioana lovinNo ratings yet

- Question 1 Language and Speech, Levels of LanguageDocument7 pagesQuestion 1 Language and Speech, Levels of LanguageElina AraqelyanNo ratings yet

- English Adjective Notes PDFDocument13 pagesEnglish Adjective Notes PDFchitalu LumpaNo ratings yet

- Verbs II Multi-Word Lexical Verbs 1 Multi-Word Verbs: Structure and MeaningDocument12 pagesVerbs II Multi-Word Lexical Verbs 1 Multi-Word Verbs: Structure and MeaningAdelina-Gabriela AgrigoroaeiNo ratings yet

- Window + Shopping - Window + Shop + Ing Immediate Constituents: Shopping, Shop, WindowDocument2 pagesWindow + Shopping - Window + Shop + Ing Immediate Constituents: Shopping, Shop, WindowMarkoNo ratings yet

- Theme 4 AdjectivesDocument4 pagesTheme 4 AdjectivesАліна БурлаковаNo ratings yet

- Question #20Document12 pagesQuestion #20Елена ХалимоноваNo ratings yet

- Adjectives Graduation WorkDocument16 pagesAdjectives Graduation WorkDušan MarkovićNo ratings yet

- 'Semantic Categories of AdjectivesDocument6 pages'Semantic Categories of AdjectivesSavu Cristi GabrielNo ratings yet

- The AdjectiveDocument16 pagesThe AdjectiveBaton 4No ratings yet

- Outline Body I - Meaning of Adjectives II - Kinds of AdjectivesDocument9 pagesOutline Body I - Meaning of Adjectives II - Kinds of AdjectivesJoelmar MondonedoNo ratings yet

- 5 6156440666508362565Document26 pages5 6156440666508362565Akash HalderNo ratings yet

- WordsDocument7 pagesWordsAleynaNo ratings yet

- Descriptive AdjectivesDocument11 pagesDescriptive AdjectivesitxtryNo ratings yet

- Major Phrase TypesNoteDocument11 pagesMajor Phrase TypesNotedaalee1997No ratings yet

- The English VerbDocument87 pagesThe English VerbAna-Maria Alexandru100% (2)

- LEC - Noun Phrase, An I, Sem. 1 IDDocument40 pagesLEC - Noun Phrase, An I, Sem. 1 IDlucy_ana1308No ratings yet

- 0 Adjectives KobrinaDocument8 pages0 Adjectives KobrinaВлада ГуменюкNo ratings yet

- Abrão Inácio PintoDocument13 pagesAbrão Inácio PintoSaide IussufoNo ratings yet

- ADJETIVESDocument7 pagesADJETIVESDI APCNo ratings yet

- Basic Tenses Perfect TensesDocument5 pagesBasic Tenses Perfect TensesrheadistarNo ratings yet

- Paradigmatic Relations Among Lexical UnitsDocument7 pagesParadigmatic Relations Among Lexical UnitsbracketsNo ratings yet

- Ref Chap4 CADocument5 pagesRef Chap4 CATuyền LêNo ratings yet

- Function Word Classes: English Majors and Minors, Year II, Autumn 2009-2010Document13 pagesFunction Word Classes: English Majors and Minors, Year II, Autumn 2009-2010Adelina-Gabriela AgrigoroaeiNo ratings yet

- Word Classes in EnglishDocument6 pagesWord Classes in EnglishgibusabuNo ratings yet

- Grammatical Categories & Word ClassesDocument45 pagesGrammatical Categories & Word Classesaila unnie100% (1)

- 4.1 What Are Word Classes Every Day DefinitionsDocument7 pages4.1 What Are Word Classes Every Day DefinitionsAhmed YahiaNo ratings yet

- Noun Phrase (I)Document7 pagesNoun Phrase (I)Alina RNo ratings yet

- Seminar 5, 6,7,8Document28 pagesSeminar 5, 6,7,8Євгеній БондаренкоNo ratings yet

- Adverbs KobrinaDocument6 pagesAdverbs KobrinaВлада ГуменюкNo ratings yet

- The Strange Behaviour of Modal Verbs: 94 CommentsDocument4 pagesThe Strange Behaviour of Modal Verbs: 94 CommentsSabir HussainNo ratings yet

- Seminar6 NazhestkinaDocument13 pagesSeminar6 NazhestkinaЕлена ПолещукNo ratings yet

- Reading - Bridging Digital Divide 3Document4 pagesReading - Bridging Digital Divide 3Елена ПолещукNo ratings yet

- seminar5 Полещук Елена БЛГ-20Document12 pagesseminar5 Полещук Елена БЛГ-20Елена ПолещукNo ratings yet

- Seminar3 NazhestkinaDocument11 pagesSeminar3 NazhestkinaЕлена ПолещукNo ratings yet

- Compact Body & Reasonable Price Chain Sachet Folding & CasingDocument2 pagesCompact Body & Reasonable Price Chain Sachet Folding & CasingMyat MinNo ratings yet

- BCDocument5 pagesBCjitendraNo ratings yet

- Fiat Lanac Chain TB - VKML - 82000 - en - 0915Document3 pagesFiat Lanac Chain TB - VKML - 82000 - en - 0915Aleksandar ZivkovicNo ratings yet

- GZ150 18 (2017-7 Edition)Document73 pagesGZ150 18 (2017-7 Edition)Rigoberto PerezNo ratings yet

- Final Thesis - Paculanang Iris ChyianneDocument83 pagesFinal Thesis - Paculanang Iris ChyianneChy Gomez100% (1)

- Keywords: Driver Seat, Comfort, Safety, Health, AdjustmentsDocument5 pagesKeywords: Driver Seat, Comfort, Safety, Health, AdjustmentsCarwell AbatayoNo ratings yet

- Highway EngineeringDocument50 pagesHighway Engineeringarpit_089No ratings yet

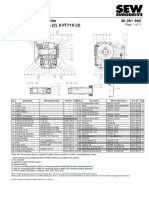

- SEW KAF77 Parts ListDocument2 pagesSEW KAF77 Parts ListAndrés Tuesca Clase de inglesNo ratings yet

- JDT NFRDocument288 pagesJDT NFRKandarp PandyaNo ratings yet

- Piaggio X9 Evolution 250 Service ManualDocument3 pagesPiaggio X9 Evolution 250 Service ManualGeorge Difool0% (1)

- KIT DE CLUTCH NAMCCO Mayo 2021Document14 pagesKIT DE CLUTCH NAMCCO Mayo 2021Aaron MartinezNo ratings yet

- JGL 45Document160 pagesJGL 45Ulises QuezadaNo ratings yet

- VR - 867 - STU - 02597 Preston To CBD Cycling Corridor Map TZ V4 - WEBDocument1 pageVR - 867 - STU - 02597 Preston To CBD Cycling Corridor Map TZ V4 - WEBJohn SmithNo ratings yet

- Autocar UK - 09 June 2021Document132 pagesAutocar UK - 09 June 2021Gavril BogdanNo ratings yet

- How To Change Glow Plugs On MERCEDES-BENZ C-Class Saloon (W202) - Replacement GuideDocument10 pagesHow To Change Glow Plugs On MERCEDES-BENZ C-Class Saloon (W202) - Replacement Guidebr213No ratings yet

- FILE - 20220108 - 123424 - (Cô Vũ Mai Phương) Mục tiêu 8-9-10 - Bộ 500 câu hỏi từ vựng hay và khó (Buổi 3)Document2 pagesFILE - 20220108 - 123424 - (Cô Vũ Mai Phương) Mục tiêu 8-9-10 - Bộ 500 câu hỏi từ vựng hay và khó (Buổi 3)Hà Anh LêNo ratings yet

- Mumbai MetroDocument3 pagesMumbai MetroNila VeerapathiranNo ratings yet

- Dca 400 Ssi DatasheetDocument4 pagesDca 400 Ssi DatasheetLevi ColsaNo ratings yet

- 4 20 Rear Axle Case and SHDocument3 pages4 20 Rear Axle Case and SHshupry yhantoNo ratings yet

- European Road Mobility During The Marshall Plan YearsDocument19 pagesEuropean Road Mobility During The Marshall Plan YearsMd. Abu TaherNo ratings yet

- Accd - Model Exam QuestionDocument2 pagesAccd - Model Exam QuestionJeyakumar VenugopalNo ratings yet

- C100-F Installation ManualDocument55 pagesC100-F Installation ManualpvfcqrtqcrNo ratings yet

- DSR 2017-18-1Document218 pagesDSR 2017-18-1Ved ChithoreNo ratings yet

- ZX210LC 5G Ka En160Document5 pagesZX210LC 5G Ka En160Mameds MefNo ratings yet