Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pramipexole Vs Levodopa As Initial Treatment For Parkinson Disea 2004

Uploaded by

Dian GbligOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pramipexole Vs Levodopa As Initial Treatment For Parkinson Disea 2004

Uploaded by

Dian GbligCopyright:

Available Formats

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION

Pramipexole vs Levodopa as Initial Treatment

for Parkinson Disease

A 4-Year Randomized Controlled Trial

The Parkinson Study Group*

Background: The best way to initiate dopaminergic Results: Initial pramipexole treatment resulted in a sig-

therapy for early Parkinson disease remains unclear. nificant reduction in the risk of developing dyskinesias

(24.5% vs 54%; hazard ratio, 0.37; 95% confidence in-

Objective: To compare initial treatment with pramipex- terval [CI], 0.25-0.56; P⬍.001) and wearing off (47% vs

ole vs levodopa in early Parkinson disease, followed by le- 62.7%; hazard ratio, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.49-0.63; P=.02). Ini-

vodopa supplementation, with respect to the develop- tial levodopa treatment resulted in a significant reduc-

ment of dopaminergic motor complications, other adverse tion in the risk of freezing (25.3% vs 37.1%; hazard ra-

events, and functional and quality-of-life outcomes. tio, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.11-2.59; P =.01). By 48 months, the

occurrence of disabling dyskinesias was uncommon

Design: Multicenter, parallel-group, double-blind, ran- and did not significantly differ between the 2 groups.

domized controlled trial. The mean improvement in the total Unified Parkinson’s

Disease Rating Scale score from baseline to 48 months

Setting: Academic movement disorders clinics at 22 sites was greater in the levodopa group than in the prami-

in the United States and Canada. pexole group (2 ± 15.4 points vs –3.2 ± 17.3 points,

P = .003). Somnolence (36% vs 21%, P = .005) and

Patients: Patients with early Parkinson disease (N=301) edema (42% vs 15%, P⬍.001) were more common in

who required dopaminergic therapy to treat emerging dis- pramipexole-treated subjects than in levodopa-treated

ability, enrolled between October 1996 and August 1997 subjects. Mean changes in quality-of-life scores did not

and observed until August 2001. differ between the groups.

Intervention: Subjects were randomly assigned to re- Conclusions: Initial treatment with pramipexole re-

ceive 0.5 mg of pramipexole 3 times per day with le- sulted in lower incidences of dyskinesias and wearing off

vodopa placebo (n = 151) or 25/100 mg of carbidopa/ compared with initial treatment with levodopa. Initial

levodopa 3 times per day with pramipexole placebo treatment with levodopa resulted in lower incidences of

(n=150). Dosage was escalated during the first 10 weeks freezing, somnolence, and edema and provided for bet-

for patients with ongoing disability. Thereafter, investi- ter symptomatic control, as measured by the Unified Par-

gators were permitted to add open-label levodopa or other kinson’s Disease Rating Scale, compared with initial treat-

antiparkinsonian medications to treat ongoing or emerg- ment with pramipexole. Both options resulted in similar

ing disability. quality of life. Levodopa and pramipexole both appear

to be reasonable options as initial dopaminergic therapy

Main Outcome Measures: Time to the first occur- for Parkinson disease, but they are associated with dif-

rence of dopaminergic complications: wearing off, dys- ferent efficacy and adverse-effect profiles.

kinesias, on-off fluctuations, and freezing; changes in the

Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale and quality-of-

life scales; and adverse events. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1044-1053

I

The Writing Group members for N 1996, THE PARKINSON STUDY risk of the development of wearing off, dys-

the Parkinson Study Group who Group initiated a multicenter ran- kinesias, or on-off motor fluctuations com-

had complete access to the raw domized clinical trial compar- pared with levodopa (28% vs 51%). How-

data needed for this report and ing initial treatment of early Par- ever, initial treatment with levodopa

who bear authorship kinson disease with pramipexole,

responsibility for this report are a nonergot dopaminergic agonist,1 with ini- CME available at

given in the “Author

Contributions” on page 1051.

tial treatment of early Parkinson disease www.archneurol.com

A complete list of the affiliations with levodopa. A report detailing the meth-

for the Writing Group appears ods and results of the first 2 years of this resulted in an early, and sustained, supe-

along with a complete list of the clinical trial has been previously pub- rior improvement in the Unified Parkin-

members of the Parkinson Study lished.2,3 After 2 years, initial pramipex- son’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) total

Group on page 1052. ole resulted in the significantly reduced score compared with pramipexole (9.2 vs

(REPRINTED) ARCH NEUROL / VOL 61, JULY 2004 WWW.ARCHNEUROL.COM

1044

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a Rice University User on 05/20/2015

4.5 points at 23.5 months). The clinical trial was ex- tion code was restricted to 2 programmers, 1 at the Parkinson

tended to a minimum of 4 years to compare initial treat- Study Group Biostatistical Center and 1 at the Pharmacia Cor-

ment with pramipexole with initial treatment with le- poration.

vodopa, with respect to the development and severity of Study subjects, steering committee members, site inves-

dopaminergic complications, other adverse events, func- tigators and coordinators, and project and data management

staff were blinded to treatment assignment. After the baseline

tional outcomes, and quality of life. visit, subjects were evaluated at 4 weeks, 10 weeks, and every

We recently published the effects of initiating prami- 3 months until the last enrolled subject completed a 48-

pexole vs levodopa in early Parkinson disease on a subset month visit in August 2001. Between June 2001 and August

of the clinical trial cohort with respect to imaging of stria- 2001, treatment assignments were disclosed to the subjects, and

tal dopamine transporter density, a marker of the dopa- neither subjects nor investigators were asked to guess the sub-

minergic neuron terminal, during the course of 4 years.4 jects’ original treatment assignments.

Using single-photon emission computed tomography and

iodine I 123–labeled 2 -carboxymethoxy-3 -(4- STUDY INTERVENTION

iodophenyl) tropane (-CIT), we found that the percent

loss in striatal123I–-CIT uptake from baseline was re- Study Drugs and 10-Week Dosage Escalation Phase

duced by approximately 40% at 22 months (P=.004), 34

Subjects were randomly assigned to the intervention groups at

months (P=.009), and 46 months (P=.01) in the group ini- the baseline visit; they entered a 10-week dosage escalation pe-

tially treated with pramipexole, as compared with the group riod. Pramipexole was taken 3 times per day as 0.25-mg, 0.5-

initially treated with levodopa. These results demonstrate mg, or 1-mg tablets or matching placebo tablets, which were iden-

a reduction in the loss of striatal dopamine transporter tical in appearance, taste, and smell. Carbidopa/levodopa was taken

density in the pramipexole group compared with the le- as 12.5/50-mg or 25/100-mg capsules or matching placebo cap-

vodopa group. Here we present the entirety of the 4-year sules. Treatment assignments included active drug for one treat-

data to extend our 2-year clinical observations and ment and placebo for the other. All subjects were escalated ini-

to complement our recently published 4-year imaging tially to a daily dosage of 1.5 mg of pramipexole or 75/300 mg of

observations. carbidopa/levodopa (level 1 dosage). Subjects requiring addi-

tional therapy could escalate to 3 mg of pramipexole or 112.5/

450 mg of carbidopa/levodopa (level 2 dosage), or 4.5 mg of pra-

METHODS mipexole or 150/600 mg of carbidopa/levodopa (level 3 dosage).

Therefore, all patients entered the follow-up phase (week 11) of

ORGANIZATION the trial on dosage level 1, 2, or 3.

This multicenter study was organized by the Parkinson Study Follow-up Phase and Allowable Treatment Options

Group in conjunction with the sponsor, Pharmacia Corpora-

tion, Peapack, NJ (formerly Pharmacia & Upjohn Inc, Kalama- The follow-up phase of the trial consisted of 2 calendar peri-

zoo, Mich). Eligible subjects were enrolled between October ods. Through February 2000, subjects were maintained on study

1996 and August 1997 at 22 sites in the United States (17) and drug at the dosage level achieved in the escalation phase, and

Canada (5), and were observed through August 2001, when subjects with emerging disability were prescribed open-label

the last subject enrolled completed a minimum of 4 years of carbidopa/levodopa as needed.6 Sustained-release carbidopa/

follow-up. The study was reviewed and approved by the insti- levodopa preparations and other antiparkinsonian medica-

tutional review board at each of the participating sites. Sub- tions could not be added or altered. From February 2000 to

jects gave written consent to participate in the 2-year clinical August 2001, subjects had expanded treatment options avail-

trial and again provided consent to participate in the extended able, in addition to adding open-label levodopa. If subjects de-

follow-up for at least an additional 2 years. An independent safety veloped wearing off, dyskinesias, or on-off fluctuations (the pri-

monitoring committee was responsible for unblinded moni- mary outcome variable), they were permitted to (1) increase

toring of patient safety data. There were no prespecified for- or decrease study drug dosages by 1 or 2 levels, (2) add sustained-

mal guidelines for the safety monitoring committee to recom- release carbidopa/levodopa, (3) alter or add amantadine, anti-

mend modification or termination of the trial. cholinergic medications, or selegiline, or (4) add a catechol-

0-methyltransferase inhibitor after all other treatment options

RECRUITMENT, RANDOMIZATION, had been used.

AND ENROLLMENT

OUTCOME VARIABLES

Details about eligibility criteria and randomization and enroll-

ment procedures have been reported.2 Eligible subjects had id- The primary outcome variable was prespecified as the time from

iopathic Parkinson disease for fewer than 7 years and required randomization until the first occurrence of any of 3 specified

dopaminergic antiparkinsonian therapy at the time of enroll- dopaminergic complications: wearing off, dyskinesias, or on-

ment. Patients who had taken levodopa or a dopaminergic ago- off fluctuations, as defined in a prior report.3 One designated

nist in the 2 months prior to enrollment were excluded. Sub- and blinded investigator at each site made the judgment at each

jects were required to be in Hoehn and Yahr stage I, II, or III.5 visit as to the occurrence of a dopaminergic complication. Sub-

Eligible patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to pramipex- jects who developed a dopaminergic complication continued

ole or levodopa, in combination with carbidopa, using a com- to be observed for the duration of the trial.

puter-generated randomization plan that included stratifica- Secondary outcome variables included changes in scores

tion by investigator and blocking. When a patient was judged on the UPDRS,7 the Parkinson’s Disease Quality-of-Life scale

eligible and consented to be enrolled, a telephone call was made (PDQUALIF),8 the EuroQol Visual Analog Scale (VAS),9 as well

to the Parkinson Study Group Coordination Center (Roches- as the need for supplemental levodopa. The UPDRS is a stan-

ter, NY), which provided a unique subject identification num- dardized, reliable, and valid instrument for assessing the se-

ber from the randomization module. Access to the randomiza- verity of the clinical features of Parkinson disease.10 The Eu-

(REPRINTED) ARCH NEUROL / VOL 61, JULY 2004 WWW.ARCHNEUROL.COM

1045

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a Rice University User on 05/20/2015

score included in the model. A 95% confidence interval was

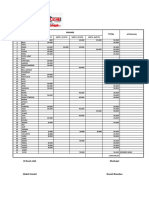

Assessed for Eligibility (n = 376) computed for the difference between the adjusted treatment

group means. Changes in UPDRS scores between baseline and

Enrollment Excluded (n = 75) the other visits were analyzed similarly. These analyses were

Not Eligible (n = 52)

Refused to Participate (n = 23) also used to examine score changes in the quality-of-life mea-

sures. The interactions between treatment and enrolling inves-

Randomization (n = 301) tigator were tested by including the appropriate interaction terms

in the model, but no such interactions were found. Two-tailed

Allocation

Allocated to Pramipexole (n = 151) Allocated to Levodopa (n = 150) Fisher exact tests were used to compare proportions of sub-

Received Pramipexole (n = 151) Received Levodopa (n = 150)

jects experiencing adverse events between the 2 treatment

Lost to Follow-up (n = 1) Lost to Follow-up (n = 1)

groups.

Discontinued Pramipexole Discontinued Levodopa For the analyses of the UPDRS scores, if a subject was miss-

Therapy (n = 67) Therapy (n = 49) ing a response at a particular visit, missing data were imputed

Somnolence (n = 11) Somnolence (n = 1)

Edema (n = 5) Edema (n = 0) using a multiple imputation algorithm similar to that de-

Somnolence and Edema (n = 1) Worsening PD Symptoms (n = 8) scribed by Little and Yau.13 For subjects with complete data up

Follow-up

Worsening PD Symptoms (n = 8) Nausea/Vomiting (n = 6)

Nausea/Vomiting (n = 4) Hallucination/Confusion (n = 4)

to a particular visit, a multiple regression model was fit that

Hallucination/Confusion (n = 4) Dyskinesias (n = 3) included the UPDRS score at that visit as the dependent vari-

Dyskinesias (n = 0) Lost Interest (n = 8) able and UPDRS scores at previous visits, treatment group, and

Lost Interest (n = 10) Other Symptoms

Other Symptoms and Comorbidities (n = 12) site as independent variables. Separate models were similarly

and Comorbidities (n = 16) Did Not Enter Extension (n = 7) constructed for each visit. Using these regression models, a miss-

Did Not Enter Extension (n = 8)

ing value for a subject at a particular visit was imputed as a draw

from the predictive distribution given the UPDRS scores at pre-

Analysis

Analyzed (n = 151) Analyzed (n = 150)

Excluded From Analysis (n = 0) Excluded From Analysis (n = 0) vious visits (some possibly imputed), treatment group, and site

of the subject.13 This was done sequentially starting with the

week 4 visit and ending with the month 48 visit. This process

Figure 1. Patient flow. PD indicates Parkinson disease.

was repeated 10 times, resulting in 10 complete analysis data

sets. The analyses of covariance were performed separately for

roQol VAS is a thermometer-type scale with 100 tick marks on each of the 10 complete analysis data sets, and the results were

which the subject rates his or her current health state on a scale combined into 1 multiple imputation inference (estimated treat-

from 0 to 100, with 0 corresponding to the worst imaginable ment effect and associated confidence interval and P value), as

health and 100 corresponding to the best imaginable health. described by Little and Yau.13 Analyses of quality-of-life out-

We used 2 questions (questions 32 and 33) from part IV of the comes were performed in a similar fashion. For the total UPDRS

UPDRS to assess the duration and disability of dyskinesias. Mea- score, missing values were imputed in 1104 (19%) of the 5719

sures of safety included incidence of adverse events. In a post person-visits in the trial, the vast majority of which were be-

hoc analysis, for those patients with somnolence or edema, we cause of subject withdrawal.

used the adverse event start and stop dates to estimate the time We performed additional exploratory analyses to deter-

spent in the trial either with somnolence or edema. In addi- mine if the risk of developing dopaminergic complications was

tion, we report on the severity of all somnolence and edema related to the degree of total UPDRS improvement during the

events as judged by the site investigator and coordinator. first 13 weeks of the trial. For this analysis, we used Cox pro-

The presence of dopaminergic events was assessed every portional hazards regression models for time to wearing off and

3 months until month 58 (4 years and 10 months). Parts I-III time to dyskinesias that included treatment group and 13-

of the UPDRS were assessed every 3 months until month 48. week change from baseline in the total UPDRS score as inde-

The quality-of-life measures were obtained every 6 months un- pendent variables and enrolling investigator as a stratification

til month 48. Part IV of the UPDRS was obtained only at months factor.

42, 45, and 48.

RESULTS

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

PATIENT FLOW

The primary statistical analyses were performed according to

the intention-to-treat principle.11 All statistical tests were 2-tailed Of the 376 patients who were identified as potential par-

and performed using a significance level of 5%. The analysis

of the primary outcome variable used the Cox proportional haz-

ticipants, 52 were found to be ineligible and 23 declined

ards regression model, with treatment group as the factor of for no specific reason (Figure 1). The remaining 301

interest and enrolling investigator as a stratification factor. The patients were randomized in the study. Sixty-eight (45%)

hazard ratio comparing the 2 treatment groups and the asso- of the 151 subjects in the pramipexole group withdrew

ciated 95% confidence interval were determined from this model. prior to the planned final follow-up visit, compared with

The assumption of proportionality of hazards was examined 50 (33%) of the 150 subjects in the levodopa group. In

with the use of time-dependent covariates.12 Separate analyses the pramipexole group, 11 withdrew because of somno-

of the time from baseline to the first occurrence of each indi- lence, 5 because of edema, and 1 because of both. In the

vidual dopaminergic complication, including freezing and the levodopa group, 1 withdrew because of somnolence and

need for supplemental levodopa, were performed. The cumu- none because of edema. Other reasons for study with-

lative probabilities of reaching the primary end point and other

end points were estimated using Kaplan-Meier survival curves.

drawal were similar between the 2 groups. There were 5

Mean changes in the total UPDRS score, as well as the men- deaths, 3 in the levodopa-treated group and 2 in the pra-

tal, motor, and activities of daily living (ADL) UPDRS scores, mipexole-treated group, all judged not to be related to

between randomization and 48 months were compared among the study drug. Two subjects, 1 in each treatment group,

the treatment groups using analysis of covariance, with treat- were lost to follow-up; both occurred after the month 48

ment group, enrolling investigator, and the baseline total UPDRS visit.

(REPRINTED) ARCH NEUROL / VOL 61, JULY 2004 WWW.ARCHNEUROL.COM

1046

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a Rice University User on 05/20/2015

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics

Completed Trial Withdrew From Trial

Pramipexole Levodopa Pramipexole Levodopa

Variable (n = 83) (n = 100) (n = 68) (n = 50)

Age, y 61.1 (9.6) 60.8 (9.8) 62.1 (10.8) 61.0 (11.9)

No. (%) of male patients 50 (60.2) 68 (68.0) 46 (67.7) 31 (62.0)

No. (%) of white patients 79 (95.2) 96 (96.0) 65 (95.6) 47 (94.0)

Years since diagnosis 1.4 (1.3) 1.8 (1.7) 1.6 (1.6) 1.8 (1.7)

No. (%) of patients with prior levodopa use 20 (24.1) 15 (15.0) 20 (29.4) 15 (30.0)

No. (%) of patients with baseline eldepryl use 14 (16.9) 21 (21.0) 16 (23.5) 13 (26.0)

No. (%) of patients with baseline amantadine use 12 (14.5) 15 (15.0) 9 (13.2) 8 (16.0)

No. (%) of patients with baseline anticholinergic use 5 (6.0) 6 (6.0) 3 (4.4) 1 (2.0)

Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale score

Total 31.6 (12.4) 29.3 (12.2) 33.7 (13.0) 34.7 (13.5)

Mental 1.1 (1.2) 0.7 (1.0) 1.5 (1.4) 1.2 (1.2)

Activities of daily living 8.7 (4.1) 7.8 (3.8) 9.5 (4.0) 9.2 (4.2)

Motor 21.9 (8.9) 20.8 (9.4) 22.7 (9.5) 24.3 (9.8)

No. (%) of patients in Hoehn and Yahr Stage

1.0 12 (14.5) 18 (18.0) 8 (11.8) 5 (10.0)

1.5 11 (13.3) 16 (16.0) 12 (17.7) 4 (8.0)

2.0 43 (51.8) 58 (58.0) 35 (51.5) 26 (52.0)

2.5 16 (19.3) 7 (7.0) 9 (13.2) 9 (18.0)

3.0 1 (1.2) 1 (1.0) 4 (5.9) 6 (12.0)

Quality-of-life scales

Parkinson’s Disease Quality-of-Life Scale 28.2 (9.9) 24.5 (10.4) 30.6 (13.6) 31.0 (12.2)

EuroQol visual analog scale 76.3 (14.3) 79.2 (11.5) 73.6 (17.1) 74.4 (12.4)

*Values are expressed as mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated. The scale ranges are as follows for the Parkinson’s Disease Quality-of-Life Scale, 0 to 100

(lower scores reflect better quality of life); and EuroQol visual analog scale, 0 to 100 (higher scores reflect better quality of life).

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS pramipexole for wearing-off (hazard ratio, 0.68; 95% CI,

0.49-0.93; P =.02) and dyskinesias (hazard ratio, 0.37;

The 2 treatment groups were similar at baseline with re- 95% CI, 0.25-0.56; P ⬍ .001) but not for on-off fluctua-

gard to demographic and clinical variables, except for tions (hazard ratio, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.26-1.59; P =.34). In

lower quality-of-life scores in the pramipexole group.2 contrast, an increased risk of freezing was observed in

Table 1 shows that the baseline UPDRS and quality-of- the pramipexole group compared with the levodopa group

life scores of subjects who completed the planned fol- (hazard ratio, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.11-2.59; P=.01). In the pra-

low-up were better than the baseline scores of subjects mipexole group, the majority of the dopaminergic com-

who prematurely withdrew. plications occurred after initiating open-label levodopa

treatment, whereas in the levodopa group, the majority

STUDY DRUG USE AND of complications occurred prior to initiating open-label

CONCOMITANT MEDICATIONS levodopa treatment. Of the 10 subjects in the pramipex-

ole group who developed dyskinesias before starting open-

Table 2 shows dosage-level changes and baseline and label levodopa treatment, 7 had no history of prior le-

trial-emergent use of medications during the trial. One vodopa exposure.

hundred nine subjects (72%) in the pramipexole group The development of dopaminergic complications by

required open-label levodopa compared with 89 (59%) treatment group was not significantly influenced by age

in the levodopa group (hazard ratio, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.22- (ⱕ60, ⬎60 years), sex, years since onset of Parkinson

2.21; P=.001). The mean total daily levodopa dosage in disease (⬍2, ⱖ2 years), dosage level, or baseline UPDRS

the pramipexole subjects was 434 ± 498 mg/d (supple- score (ⱕ30, ⬎30 units). Pramipexole tended to be par-

mental only) compared with 702±461 mg/d (experimen- ticularly effective in reducing the risk of developing dys-

tal: 427±112 mg plus supplemental: 274±442 mg) in the kinesias in subjects with baseline Hoehn and Yahr scores

levodopa group. Subjects allocated to pramipexole took of less than 2 compared with subjects with baseline Hoehn

an average of 2.78 ± 1.1 mg/d by the end of the trial. and Yahr scores of 2 or higher (hazard ratio, 0.15 vs 0.46;

P=.06).

DOPAMINERGIC END POINTS

SEVERITY OF DYSKINESIAS

Table 3 and Figure 2 show that 52% of subjects as-

signed to pramipexole treatment reached the primary end At the month 48 visit, 12 (13%) of 91 subjects in the pra-

point of developing dyskinesias, wearing off, or on-off mipexole group indicated the presence of dyskinesias,

fluctuations compared with 74% of the levodopa group and 4 of the 12 indicated that the dyskinesias were mildly

(hazard ratio, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.35-0.66; P⬍.001). A re- disabling. In the levodopa group, 32 (32%) of 101 sub-

duced risk was observed for those subjects assigned to jects indicated the presence of dyskinesias; 6 indicated

(REPRINTED) ARCH NEUROL / VOL 61, JULY 2004 WWW.ARCHNEUROL.COM

1047

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a Rice University User on 05/20/2015

Table 2. Drug Use During Trial Table 3. Treatment Effects on Dopaminergic End Points*

Pramipexole Levodopa Pramipexole, Levodopa,

(n = 151) (n = 150) No. (%) No. (%) P

End Points (n = 151) (n = 150) HR (95% CI) Value

Dosage level changes

Up 1 level 14 14 First dopaminergic 78 (51.7) 111 (74.0) 0.48 (0.35-0.66) ⬍.001

Up 2 levels 2 5 complication†

Down 1 level 6 2 Wearing off 71 (47.0) 94 (62.7) 0.68 (0.49-0.93) .02

Down 2 levels 2 0 Dyskinesias 37 (24.5) 81 (54.0) 0.37 (0.25-0.56) ⬍.001

Open-label levodopa On-off fluctuations 10 (6.6) 12 (8.0) 0.64 (0.26-1.59) .34

Baseline use 0 0 Freezing 56 (37.1) 38 (25.3) 1.70 (1.11-2.59) .01

Trial-emergent use 109 89 Off-period dystonia 53 (35.1) 69 (46.0) 0.73 (0.51-1.06) .10

Eldepryl

Baseline use 30 34 Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Trial-emergent use 21 22 *All analyses are stratified by the enrolling investigator. The hazard ratio is

Amantadine the ratio of the risk of reaching the end point per unit of time for patients

Baseline use 21 23 assigned to initially receive pramipexole treatment, to the corresponding risk for

patients assigned to initially receive levodopa treatment.

Trial-emergent use 11 21

†Defined as the first occurrence of wearing off, dyskinesia, or on-off

Anticholinergics fluctuations.

Baseline use 8 7

Trial-emergent use 4 7

Catechol-O-methyl transferase inhibitors

Baseline use 0 0 of somnolence, 8 described their somnolence as “sud-

Trial-emergent use 3 4 den” or “unexpected,” and 5 said these episodes oc-

Antidepressants curred while driving. The 1 subject in the levodopa group

Baseline use 6 6 who withdrew because of somnolence was described as

Trial-emergent use 46 45 having “increased daytime drowsiness.”

Anxiolytics

Baseline use 2 3

For subjects randomized to pramipexole who ex-

Trial-emergent use 18 22 perienced 1 or more episodes of edema, a mean±SD of

Antipsychotics 46.1%±37.4% of their total days spent in the trial were

Baseline use 0 0 spent with edema, compared with a mean of

Trial-emergent use 7 2 30.6%±31.7% for subjects in the levodopa group. Of the

total 125 edema events recorded in subjects random-

ized to the pramipexole group, 49 (35%) were judged to

be of moderate or severe intensity compared with 11

that the dyskinesias were mildly disabling, and 1 indi- (23%) of the total 41 edema events in the levodopa group.

cated that the dyskinesias were moderately disabling. The There were 7 serious adverse events relating to driv-

remainder of both groups indicated no disability from their ing. Two events occurred in 2 subjects randomized to le-

dyskinesias: 8 in the pramipexole group and 25 in the vodopa, and 5 events occurred in 4 subjects random-

levodopa group. Similar patterns of dyskinesia fre- ized to pramipexole. Of the 2 events in the levodopa group,

quency and disability were seen at the month 42 and 1 subject described “falling asleep at the wheel.” Of the

month 45 visits. 5 events in the pramipexole group, 3 events in 2 sub-

jects were described as “falling asleep” or “sudden onset

OTHER ADVERSE EVENTS of sleep” while driving.

Table 4 shows that significantly more patients in the UNIFIED PARKINSON’S DISEASE RATING SCALE

pramipexole group experienced edema (P⬍.001), som-

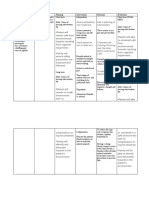

nolence (P = .005), and cellulitis (P = .01). Urinary fre- The mean improvements in total, motor, and activities

quency (P=.01) and hernia (P = .002) were more com- of daily living UPDRS scores from baseline to 48 months

mon in the levodopa group. Somnolence most commonly were greater in the levodopa group than in the prami-

developed during the escalation phase in the pramipex- pexole group (Table 5). In each treatment group, the

ole group as compared with edema and cellulitis, which initial improvements achieved in UPDRS scores slowly

tended to occur later in the trial. decayed across time, with an approximate decay rate of

For subjects randomized to pramipexole who ex- 3 total UPDRS units per year, although the difference be-

perienced 1 or more episodes of somnolence, a mean±SD tween the groups remained relatively constant (Figure 3).

of 46.4%±36.2% of their total days in the trial were spent The mean improvement in the mental UPDRS score from

somnolent compared with a mean of 17.5% ± 32.9% for baseline was greater at each study visit in the pramipex-

subjects in the levodopa group. Of the total 103 somno- ole group compared with the levodopa group but did not

lence events recorded in those randomized to the pra- reach statistical significance (Figure 3, Table 5).

mipexole group, 39 (38%) were judged by the site in- The 13-week change from baseline in total UPDRS

vestigator or coordinator to be of moderate or severe score was significantly associated with time to dyskine-

intensity compared with 12 (22%) of the total 48 som- sias (hazard ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.95-1; P=.05) but not

nolence events in the levodopa group. Of the 12 sub- significantly associated with time to wearing off (hazard

jects in the pramipexole group who withdrew because ratio, 1; 95% CI, 0.98-1.03; P =.82). After adjusting for

(REPRINTED) ARCH NEUROL / VOL 61, JULY 2004 WWW.ARCHNEUROL.COM

1048

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a Rice University User on 05/20/2015

First Dopaminergic Complication Dyskinesias

1.0

0.9 Levodopa

0.8 Pramipexole

Probability of End Point

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

Wearing Off Freezing

1.0

0.9

0.8

Probability of End Point

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

0 6 12 18 24 30 36 42 48 54 0 6 12 18 24 30 36 42 48 54

Months From Randomization Months From Randomization

Figure 2. Cumulative probability of reaching the first dopaminergic complication (A) and the individual complications wearing off (B), dyskinesias (C), and freezing

(D) by treatment assignment. First dopaminergic complication is defined as the first occurrence of wearing off, dyskinesias, or on-off fluctuations.

short-term UPDRS improvement, the treatment group Our dyskinesia severity data differ from those of a

hazard ratio for time to dyskinesia remained similar prior study comparing the severity of dyskinesias after 5

to that reported in Table 3 (hazard ratio, 0.39; 95% CI, years of treatment among subjects initially treated with

0.26-0.6; P⬍.001). ropinirole vs levodopa.14 The ropinirole study reported

the incidence of “disabling” dyskinesias as measured by

QUALITY-OF-LIFE OUTCOMES a response of mildly, moderately, severely, or com-

pletely disabling on question 33 of the UPDRS at any

The total scores on the PDQUALIF and the EuroQol VAS time during the month 60 trial: 14 (7.8%) of 179

improved in both groups by approximately 2 units dur- patients in the ropinirole group and 20 (22.4%) of 89

ing the first 6 months and then worsened across time at patients in the levodopa group. We report the point

a decay rate of approximately 1 unit per year. At 48 prevalence of disabling dyskinesias at month 48: 4

months, the mean change scores were not significantly (4.4%) of 91 patients in the pramipexole group and 7

different between the treatment groups for either the (6.9%) of 101 patients in the levodopa group at the

PDQUALIF or the EuroQol VAS. Analyses of the 7 month 48 visit. These trial differences occurred despite

PDQUALIF subscales revealed no significant treatment similar mean amounts ± SD of total levodopa in the

group differences. levodopa groups at the end of both studies: 753 ± 398

mg/d in the ropinirole trial vs 702±461 mg/d in the pra-

COMMENT mipexole trial. The lower frequency of disabling dyski-

nesias in our trial compared with that in the ropinirole

Our findings show that after 4 years of treatment, 74% trial may be partly explained if early-onset dyskinesias

of subjects assigned to initial levodopa experienced a do- were transient and successfully treated with medication

paminergic motor complication (wearing off, dyskine- adjustments.

sia, or on-off fluctuations) compared with 52% of sub- The observation that the development of freezing

jects assigned to initial pramipexole. The treatment was more common in the pramipexole group than in the

differential was most striking for dyskinesias (54% of sub- levodopa group has been previously reported for other

jects in the levodopa group vs 25% of subjects in the pra- dopamine agonists.14 In the ropinirole trial, 57 (32%) of

mipexole group) and wearing off (63% vs 47%, 178 subjects in the ropinirole group and 22 (25%) of 88

respectively). The differences in the risks of developing subjects in the levodopa group reported an increase in

dyskinesias and wearing off persisted even after we con- freezing when walking. More research is needed on the

trolled for early symptomatic changes in UPDRS, which relative value that patients place on early motor compli-

suggests that these complications are mediated via mecha- cations, on the impact of early motor complications on

nisms other than the magnitude of early UPDRS im- short-term patient function, and on their ability to pre-

provement. dict long-term disability.

(REPRINTED) ARCH NEUROL / VOL 61, JULY 2004 WWW.ARCHNEUROL.COM

1049

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a Rice University User on 05/20/2015

Table 4. Adverse Events by Treatment Group and Study Table 5. Mean Changes From Baseline to Month 48 in

Phase Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Scores (UPDRS)*

No. (%) Pramipexole Levodopa Treatment Effect† P

Scale Score (n = 151) (n = 150) (95% CI) Value

Pramipexole Levodopa P

(n = 151) (n = 150) Value Total UPDRS −3.2 (17.3) 2.0 (15.4) −5.9 (−9.6, −2.1) .003

Motor −1.3 (13.3) 3.4 (12.3) −4.9 (−7.8, −1.9) .001

Edema* 64 (42.4) 22 (14.7) ⬍.001 ADL −1.7 (5.4) −0.5 (4.7) −1.4 (−2.5, −0.2) .02

Escalation 11 3 Mental −0.3 (1.6) −0.8 (1.6) 0.3 (−0.1, 0.7) .10

Week 11 through month 23.5 39 13

Month 23.5 through month 48+ 14 6

Abbreviation: ADL, activities of daily living.

Peripheral edema 34 (22.5) 9 (6.0) ⬍.001 *Values are mean (SD). Negative values indicated worsening and positive

Escalation 7 2 values indicated improvement.

Week 11 through month 23.5 17 4 †Treatment effect is the difference in mean change between the groups

Month 23.5 through month 48+ 10 3 (pramipexole, levodopa), adjusted for investigator effects and the baseline

Somnolence 56 (36.4) 32 (21.3) .005 value of the outcome variable in an analysis of covariance model. All

Escalation 35 13 analyses are based on multiple imputation for missing values.

Week 11 through month 23.5 13 13

Month 23.5 through month 48+ 7 6

Hallucination 22 (14.6) 12 (8.0) .10

of the 7 patients who developed cellulitis in the prami-

Escalation 10 2 pexole group also had a history of edema.

Week 11 through month 23.5 4 3 The levodopa group continued to have less impair-

Month 23.5 through month 48+ 8 7 ment and disability, as measured by the UPDRS, than did

Cellulitis 7 (4.6) 0 (0.0) .01 the pramipexole group, and the group differences ob-

Escalation 0 served in the motor and activities of daily living compo-

Week 11 through month 23.5 3

Month 23.5 through month 48+ 4

nents remained relatively uniform throughout the 4 years,

Urinary frequency 5 (3.3) 16 (10.7) .01 with a parallel decay in UPDRS scores across time. It re-

Escalation 1 5 mains unclear why the UPDRS scores of subjects assigned

Week 11 through month 23.5 3 5 to pramipexole never caught up despite the options of open-

Month 23.5 through month 48+ 1 6 label levodopa and other antiparkinsonian therapies. A po-

Hernia 1 (0.7) 12 (8.0) .002 tential explanation is that the initial UPDRS response was

Escalation 0 1

deemed satisfactory by patients and physicians and was used

Week 11 through month 23.5 0 2

Month 23.5 through month 48+ 1 9 as a benchmark to gauge further therapy.2 Alternatively,

the presence of a dopamine agonist may somehow attenu-

*Edema includes peripheral edema, localized edema, generalized edema, ate the dopaminergic potency of levodopa possibly by com-

facial edema, tongue edema, periorbital edema, and lymphedema. petitive inhibition or down-regulation of postsynaptic ni-

grostriatal dopamine receptors.

Those subjects randomized to pramipexole tended The mean group difference in the UPDRS activities

to experience somnolence earlier, more frequently, and of daily living scores found in this study was similar to

more severely, as evidenced by the higher discontinua- that published in a prior report in which it was con-

tion rates and the greater time spent somnolent during cluded that there was no significant difference between

the trial. The precise factors that predict somnolence, ir- the groups initially treated with ropinirole vs le-

resistible daytime sleepiness, and driving risk are not com- vodopa.14 In the ropinirole study, there was no imputa-

pletely known, but this study suggests that pramipexole- tion of missing values, as there was in our study, and the

treated subjects had a higher risk for somnolence than resulting smaller sample sizes may have contributed to

levodopa-treated subjects. This contrasts with a recent the reported lack of statistically significant group differ-

prospective evaluation of a large number of patients with ences. In long-term clinical trials, the strategy of includ-

Parkinson disease that found no relationship between day- ing all randomized subjects in an intent-to-treat analy-

time sleepiness and falling asleep at the wheel and any sis is accepted to be generally superior to the strategy of

specific antiparkinsonian drug or class of drugs.15 Pa- performing the analyses based only on subjects who com-

tients who do experience generalized drowsiness and fall- plete the trial. This is particularly true for the present trial,

ing asleep during periods of inactivity, regardless of their in which the withdrawal rate by 48 months was close to

antiparkinsonian medications, should be instructed not 40% and the rates differed somewhat between the 2 treat-

to drive or to partake in activities during which falling ment arms. Assuming that the strategy for imputing miss-

asleep would present a danger. ing data is reasonable, bias should be reduced through

We found the frequency of pramipexole-associated preservation of the randomized groups, and power is in-

edema to be higher than that previously reported.16 The creased by retaining all subjects in the analysis. To avoid

mechanism of dopamine agonist–induced edema is un- artificially increasing power through data imputation, we

known, but it is reversible with cessation of therapy or used multiple imputation to account for the uncertainty

reduction in dosage. Prior studies have shown that pra- associated with the imputation.13

mipexole-induced edema can affect function, and 6 pa- We did not find significant differences in the quality-

tients assigned to pramipexole in this study withdrew early of-life scores between the 2 treatment groups during the

because of edema. More research is needed on the long- 4 years of follow-up. Treatment group differences in the

term impact of edema, particularly given the fact that 6 occurrence of dopaminergic complications and UPDRS

(REPRINTED) ARCH NEUROL / VOL 61, JULY 2004 WWW.ARCHNEUROL.COM

1050

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a Rice University User on 05/20/2015

Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale Total Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale Motor

4

Mean Change From Baseline 2

0

–2

–4

–6

–8

–10

Levodopa

–12

Pramipexole

–14

–16

Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale Activities of Daily Living Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale Mental

4

2

Mean Change From Baseline

0

–2

–4

–6

–8

–10

–12

–14

–16

0 6 12 18 24 30 36 42 48 0 6 12 18 24 30 36 42 48

Months From Randomization Months From Randomization

Figure 3. Mean (SE) total (parts I+II+III), motor, activities of daily living, and mental Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale scores during the course of the

trial by treatment assignment.

scores did not translate into mean group differences in In conclusion, during the 4 years of the study, ini-

either the disease-specific health status measure tial treatment with pramipexole resulted in lower inci-

(PDQUALIF) or the generic-based preference measure dences of dyskinesias and wearing off and in less rela-

(EuroQol VAS). We hypothesize that these measures were tive reduction in striatal 123I–-CIT uptake compared with

unable to differentiate between the mean group cumu- initial levodopa. On the other hand, initial treatment with

lative health effects for these treatment options, or the levodopa resulted in lower incidences of freezing, som-

quality-of-life differences between the 2 options were in- nolence, and edema, and provided for better symptom-

consequential. atic control, as measured by the UPDRS, compared with

In a subset of this cohort (n=82), patients treated with initial treatment with pramipexole. Both resulted in simi-

pramipexole demonstrated a 40% lower rate of loss of stria- lar changes in quality of life. Pramipexole and levodopa

tal 123I–-CIT uptake, a marker of the dopamine trans- are associated with different efficacy and adverse-effect

porter receptor, than those patients initially treated with profiles. These differences are insufficient to identify a

levodopa during a month 46 evaluation period.4 It is not preferred strategy; hence, both pramipexole and le-

yet known, however, if the reduction in the rate of dopa- vodopa appear to be reasonable options as initial dopa-

mine transporter loss as measured by striatal 123I– -CIT minergic therapy in Parkinson disease. Long-term fol-

uptake reflects better neuronal survivability or merely dif- low-up is needed to determine if either treatment strategy

ferential regulation of dopamine transporter receptors. No is superior to the other in terms of patient impairment,

data have yet established a clinical advantage paralleling disability, or quality of life.

the biomarker advantage of pramipexole.

This study has several limitations. First, the conclu- Accepted for publication March 1, 2004.

sions to be drawn are limited to comparing the treatment Author contributions: Study concept and design

strategies of initial pramipexole followed by open-label le- (Drs Holloway, Shoulson, Fahn, Kieburtz, Lang, Marek,

vodopa vs initial levodopa followed by open-label le- McDermott, Seibyl, Weiner, and Musch; and Ms Kamp);

vodopa. We did not study the option of initial levodopa acquisition of data (Drs Holloway, Welsh, Shinaman,

followed by a dopamine agonist, which may have miti- Pahwa, Barclay, Hubble, Lewitt, Miyasaki, Suchower-

gated the differences in dopaminergic events between the sky, Stacy, Russell, Ford, Hammerstad, Riley, Standaert,

2 treatment arms as well as the difference in UPDRS scores. Wooten, Factor, Jankovic, Atassi, Kurlan, Panisset,

Second, we do not report on the relative cost-effectiveness Rajput, Rodnitzky, Shults, Petzinger, Waters, Pfeiffer,

of pramipexole compared with that of levodopa, which is Biglan, and Borchert; and Mss Montgomery, Suther-

an important consideration given that pramipexole is sub- land, Weeks, DeAngelis, Sime, Wood, Pantella, Harri-

stantially more costly than levodopa.17 This will be the sub- gan, Fussell, Dillon, Alexander-Brown, Rainey, Tennis,

ject of a future report. Rost-Ruffner, Brown, Evans, Berry, Hall, Shirley, Dob-

(REPRINTED) ARCH NEUROL / VOL 61, JULY 2004 WWW.ARCHNEUROL.COM

1051

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a Rice University User on 05/20/2015

Parkinson Study Group

Steering Committee

University of Rochester, Rochester, NY: Robert G. Holloway, MD, MPH (medical director), Ira Shoulson, MD (principal in-

vestigator), Karl Kieburtz, MD, MPH, Michael McDermott, PhD (chief biostatistician), Aileen Shinaman, JD (PSG Executive

Director, ex-officio), Cornelia Kamp, MBA, CCRC (project coordinator, ex-officio); Columbia University, New York, NY: Stan-

ley Fahn, MD (coprincipal investigator); Toronto Western Hospital, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario: Anthony

Lang, MD; The Institute for Neurodegenerative Disorders, New Haven, Conn: Kenneth Marek, MD (principal investigator for

-CIT), John Seibyl, MD (coprincipal investigator for -CIT); University of Maryland, Baltimore: William Weiner, MD; Uni-

versity of Southern California, Los Angeles: Mickie Welsh, RN, DNS (ex-officio).

Participating Investigators and Coordinators

University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS: Rajesh Pahwa, MD, Amy Montgomery, RN; Ottawa Civic Hospital, Ot-

tawa, Ontario: Lynn Barclay, MD, Laura Sutherland, RN; Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio: Jean Hubble, MD, Carolyn

Weeks, MT,; Clinical Neuroscience Center, Southfield, Mich: Peter LeWitt, MD, Maryan DeAngelis, RN; Toronto Western Hos-

pital, University Health Network, Toronto: Janis Miyasaki, MD, Elspeth Sime, RN; University of Calgary Medical Clinic, Cal-

gary, Alberta: Oksana Suchowersky, MD, Susan Wood, RN, Carol Pantella, RN; Barrow Neurological Institute, Phoenix, Ariz:

Mark Stacy, MD, Mary Harrigan, RN, MN; The Institute for Neurodegenerative Disorders, New Haven: David S. Russell, MD,

PhD, Barbara Fussell, RN; Columbia University, New York: Blair Ford, MD, Sandra Dillon, RN; Oregon Health Sciences Uni-

versity, Portland: John Hammerstad, MD, Barbara Alexander-Brown, RN; University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleveland, Ohio:

David Riley, MD, Pamela Rainey, RN; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston: David Standaert, MD, Marsha Tennis, RN; Uni-

versity of Virginia Health Sciences Center, Charlottesville: Frederick Wooten, MD, Elke Rost-Ruffner, RN; Albany Medical Col-

lege, Albany, NY: Stewart Factor, DO, Diane Brown, RN, Sharon Evans, LPN; Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex: Joseph

Jankovic, MD, Farah Atassi, MPH; University of Rochester, Rochester: Roger Kurlan, MD, Debra Berry MSN; McGill Centre

for Studies in Aging, Douglas Hospital, Verdun, Quebec: Michel Panisset, MD, Jean Hall, RN; Saskatoon District Health

Board, Royal University Hospital, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: Ali Rajput, MD, Theresa Shirley, RN; University of Iowa Hospitals,

Iowa City: Robert Rodnitzky, MD, Judith Dobson, RN; University of California, San Diego, Alzheimer’s Research Center,

La Jolla, Calif: Cliff Shults, MD, Deborah Fontaine, RNC; University of Southern California, Los Angeles: Giselle Petzinger,

MD, Cheryl Waters, MD, Mickie Welsh, RN, DNSc; University of Tennessee-Memphis, Memphis: Ronald Pfeiffer, MD, Brenda

Pfeiffer, RN, BSN.

Biostatistics and Clinical Trials Coordination Center Staff

University of Rochester, Rochester: Kevin Biglan, MD, Alicia Brocht, BA, Susan Bennett, AAS, Susan Daigneault, Karen Hodge-

man, CCRA, Carolynn O’Connell, Tori Ross, MA, Arthur Watts, BS. Pfizer (formerly of Pharmacia) Corporation, Peapack, NJ:

Bruno Musch, MD, Karen Richard, MS; BI (formerly of Pharmacia) Corporation: Leona Borchert, MD, MS.

son, Fontaine, Pfeiffer, Brocht, Bennett, Daigneault, DeAngelis, Sime, Harrigan, Fussell, Dillon, Alexander-

Hodgeman, O’Connell, Ross, and Richard); analysis Brown, Rainey, Tennis, Rost-Ruffner, Brown, Evans,

and interpretation of data (Drs Holloway, Fahn, Lang, Berry, Hall, Shirley, Dobson, Fontaine, Pfeiffer,

Marek, McDermott, Seibyl, Weiner, and Musch; Ms Brocht, Bennett, Daigneault, Hodgeman, O’Connell,

Kamp; and Mr Watts); drafting of the manuscript (Drs and Ross); study supervision (Drs Holloway, Shoulson,

Holloway and McDermott); critical revision of the Fahn, Kieburtz, Lang, Marek, McDermott, Seibyl,

manuscript for important intellectual content (Drs Weiner, Ford, Musch, and Borchert; and Mss Kamp,

Shoulson, Fahn, Kieburtz, Lang, Marek, McDermott, Wood, Pantella, and Richard).

Seibyl, Weiner, Welsh, Shinaman, Pahwa, Barclay, This study was supported primarily by the Pharma-

Hubble, Lewitt, Miyasaki, Suchowersky, Stacy, Rus- cia Corporation (Peapack, NJ) and Boehringer Ingelheim

sell, Ford, Hammerstad, Riley, Standaert, Wooten, Pharma (Ingelheim, Germany). Support was also provided

Factor, Jankovic, Atassi, Kurlan, Panisset, Rajput, by The National Parkinson Foundation Center of Excel-

Rodnitzky, Shults, Petzinger, Waters, Pfeiffer, Biglan, lence (Chicago, Ill) to the Parkinson Study Group, and by

Musch, and Borchert; Mss Kamp, Montgomery, the National Institutes of Health for Clinical Research Cen-

Sutherland, Weeks, DeAngelis, Sime, Wood, Pantella, ter (Bethesda, Md) grants RR00044 and RR01066 at the Uni-

Harrigan, Fussell, Dillon, Alexander-Brown, Rainey, versity of Rochester (Rochester, NY) and the Massachu-

Tennis, Rost-Ruffner, Brown, Evans, Berry, Hall, Shir- setts General Hospital (Boston, Mass), respectively.

ley, Dobson, Fontaine, Pfeiffer, Brocht, Bennett, In keeping with the Parkinson Study Group conflict of

Daigneault, Hodgeman, O’Connell, Ross, and Richard; interest guidelines, none of the investigators has any personal

and Mr Watts); statistical expertise (Dr McDermott and financial relationship with the sponsor. All compensation re-

Mr Watts); obtained funding (Dr Holloway); adminis- ceived by investigators for trial-related services was paid

trative, technical, and material support (Drs Welsh, through a contract between the University of Rochester and

Shinaman, Pahwa, Barclay, Hubble, Lewitt, Miyasaki, the sponsor that was established before the trial began.

Suchowersky, Stacy, Russell, Ford, Riley, Standaert, We thank the patients and their families who partici-

Wooten, Factor, Jankovic, Atassi, Kurlan, Panisset, pated in this study. We acknowledge the Parkinson Study

Rajput, Rodnitzky, Shults, Petzinger, Waters, Pfeiffer, Group safety monitoring committee: W. Jackson Hall, PhD,

and Biglan; and Mss Montgomery, Sutherland, Weeks, Pierre Tariot, MD (chair), University of Rochester, Roch-

(REPRINTED) ARCH NEUROL / VOL 61, JULY 2004 WWW.ARCHNEUROL.COM

1052

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a Rice University User on 05/20/2015

ester, NY; Carl M. Leventhal, MD, Rockville, Md; Stephen 6. Parkinson Study Group. DATATOP: a multicenter controlled clinical trial in early

Parkinson’s disease. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:1052-1060.

Reich, MD, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md; Kirk 7. Lang AE, Fahn S. Assessment of Parkinson’s disease. In: Munsat TL, ed. Quan-

Taylor, MD, Christopher Wohlberg, MD, PhD, T. Kevin Mur- tification of Neurologic Deficit. Boston, Mass: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1989:

phy, PhD, Ponni Subbiah, MD, Pfizer (formerly of Phar- 285-309.

macia) Corporation, Peapack, NJ; and Giora Davidai, MD, 8. Welsh M, McDermott MP, Holloway RG, et al. Development and testing of the

BI (formerly of Pharmacia) Corporation, Ridgefield, Conn. Parkinson’s Disease Quality of Life Scale: the PDQUALIF. Mov Disord. 2003;18:

637-645.

Correspondence: Robert G. Holloway, MD, MPH, De- 9. EuroQol Group. EuroQol: a new facility for the measurement of health-related

partment of Neurology, University of Rochester, 1351 Mt quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;12:199-208.

Hope Ave, Suite 220, Rochester, NY 14620 (robert.hollo- 10. Richards M, Marder K, Cote L, Mayeux R. Interrater reliability of the Unified

way @ctcc.rochester.edu). Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale motor examination. Mov Disord. 1994;9:89-

91.

11. Lee YJ, Ellenberg JH, Hirtz DG, Nelson KB. Analysis of clinical trials by treat-

REFERENCES ment actually received: is it really an option? Stat Med. 1991;10:1595-1605.

12. Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. New

York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1980.

1. Piercey MF, Camacho-Ochoa M, Smith MW. Functional roles for dopamine- 13. Little R, Yau L. Intent-to-treat analysis for longitudinal studies with drop-outs.

receptor subtypes. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1995;18(suppl):S34-S42. Biometrics. 1996;52:1324-1333.

2. Parkinson Study Group. Pramipexole vs levodopa as initial treatment for Par- 14. Rascol O, Brooks DJ, Korczyn AD, De Deyn P, Clarke CE, Lang AE. A five-year study

kinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;284:1931-1938. of the incidence of dyskinesia in patients with early Parkinson’s disease who were

3. Parkinson Study Group. A randomized controlled trial comparing pramipexole treated with ropinirole or levodopa. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1484-1491.

with levodopa in early Parkinson’s disease: design and methods of the CALM-PD 15. Hobson DE, Lang AE, Martin WR, Razmy A, Rivest J, Fleming J. Excessive day-

Study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2000;23:34-44. time sleepiness and sudden-onset sleep in Parkinson disease: a survey by the

4. Marek KL, The Parkinson Study Group. Dopamine transporter brain imaging to Canadian Movement Disorders Group. JAMA. 2002;287:455-463.

assess the effects of pramipexole vs levodopa on Parkinson disease progres- 16. Tan EK, Ondo W. Clinical characteristics of pramipexole-induced peripheral edema.

sion. JAMA. 2002;287:1653-1661. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:729-732.

5. Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurol- 17. Medical Economics Company. Drug Topics Red Book. Montvale, NJ: Medical Eco-

ogy. 1967;17:427-442. nomics Co; 2001.

(REPRINTED) ARCH NEUROL / VOL 61, JULY 2004 WWW.ARCHNEUROL.COM

1053

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a Rice University User on 05/20/2015

9. Davis KL, Mohs RC, Marin D, et al. Cholinergic markers in elderly patients with 17. Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC. Mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 1999;

early signs of Alzheimer’s disease. JAMA. 1999;281:1401-1406. 56:303-308.

10. Beelke M, Sannita WG. Cholinergic function and dysfunction in the visual system. 18. Albert M, Smith LA, Steer PA, Taylor JO, Evans DA, Funkenstein HH. Use of brief

Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2002;24:113-117. cognitive tests to identify individuals in the community with clinically diagnosed

11. Tiraboschi P, Hansen LA, Alford M, Masliah E, Thal LJ, Corey-Bloom J. The de- Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Neurosci. 1991;57:167-178.

cline in synapses and cholinergic activity is asynchronous in Alzheimer’s disease. 19. Devanand DP, Folz M, Gorlyn M, Moeller JR, Stern Y. Questionable dementia:

Neurology. 2000;55:1278-1283. clinical course and predictors of outcome. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:321-328.

12. DeKosky ST, Ikonomovic MD, Styren S, et al. Upregulation of choline acetyl- 20. Morris JC, Storandt M, Miller JP, et al. Mild cognitive impairment represents early-

transferase activity in hippocampus and frontal cortex of elderly subjects with stage Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:397-405.

mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:145-155. 21. Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological staging of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neu-

13. Mufson EJ, Ikonomovic MD, Styren SD, et al. Preservation of brain nerve growth ropathol (Berl). 1991;82:239-259.

factor in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol. 2003; 22. National Institute on Aging and Reagan Institute Working Group on Diagnosis

60:1143-1148. Criteria for the Neuropathological Assessment of Alzheimer’s disease.

14. Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, et al. Natural history of mild cognitive im- Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of AD. Neurobiol

pairment in older persons. Neurology. 2002;59:198-205. Aging. 1997;18:S1-S3.

15. Wilson RS, Beckett LA, Barnes LL, et al. Individual differences in rates of change 23. DeKosky ST, Scheff SW, Markesbery WR. Laminar organization of cholinergic

in cognitive abilities of older persons. Psychol Aging. 2002;17:179-193. circuits in human frontal cortex in Alzheimer’s disease and aging. Neurology.

16. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical 1985;35:1425-1431.

diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of Health and Human Services Task Force 24. Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer’s disease. Am

on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939-944. J Psychiatry. 1984;141:1356-1364.

Correction

Error in Figure. In Figure 3 of the article titled “Prami-

pexole vs Levodopa as Initial Treatment for Parkinson

Disease: A 4-Year Randomized Controlled Trial,” pub-

lished in the July issue of the ARCHIVES (2004;61:1044-

1053), the lines indicating mean change in Unified Par-

kinson’s Disease Rating Scale activities of daily living

scores during pramipexole and levodopa treatments

should be reversed. The top line should indicate prami-

pexole, and the bottom line should indicate levodopa.

(REPRINTED) ARCH NEUROL / VOL 62, MAR 2005 WWW.ARCHNEUROL.COM

430

©2005 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a Rice University User on 05/20/2015

You might also like

- Nejmoa 2202867Document12 pagesNejmoa 2202867Duke ChungNo ratings yet

- Update On The Use of Pramipexole in The Treatment of Parkinson's DiseaseDocument16 pagesUpdate On The Use of Pramipexole in The Treatment of Parkinson's DiseaseDiego Marcelo Aragon CaqueoNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Medication Withholding in Patients With Parkinson's DiseaseDocument10 pagesPerioperative Medication Withholding in Patients With Parkinson's DiseaseMarli VitorinoNo ratings yet

- Tohen 2003Document9 pagesTohen 2003Francisco VillalonNo ratings yet

- OiutDocument11 pagesOiutPrasetiyo WilliamNo ratings yet

- NuitDocument12 pagesNuitPrasetiyo WilliamNo ratings yet

- MkioutDocument12 pagesMkioutPrasetiyo WilliamNo ratings yet

- MiutoDocument12 pagesMiutoPrasetiyo WilliamNo ratings yet

- NjiutDocument12 pagesNjiutPrasetiyo WilliamNo ratings yet

- MoiuDocument12 pagesMoiuPrasetiyo WilliamNo ratings yet

- Koiu MMDocument12 pagesKoiu MMPrasetiyo WilliamNo ratings yet

- Clozapine Alone Versus Clozapine and Risperidone With Refractory SchizophreniaDocument11 pagesClozapine Alone Versus Clozapine and Risperidone With Refractory SchizophreniawardahNo ratings yet

- Olanzapine For Schizophrenia Refractory To Typical and Atypical Antipsychotics: An Open-Label, Prospective TrialDocument6 pagesOlanzapine For Schizophrenia Refractory To Typical and Atypical Antipsychotics: An Open-Label, Prospective TrialLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Gerd 3Document6 pagesJurnal Gerd 3sega maulanaNo ratings yet

- Drug Therapy For Parkinson's DiseaseDocument9 pagesDrug Therapy For Parkinson's DiseaseDireccion Medica EJENo ratings yet

- Complicatii LevodopaDocument5 pagesComplicatii LevodopaCarmen CiursaşNo ratings yet

- 2006-Long-Term Use of Oxcarbazepine Oral Suspension in Childhood Epilepsy - Open-Label Study PDFDocument6 pages2006-Long-Term Use of Oxcarbazepine Oral Suspension in Childhood Epilepsy - Open-Label Study PDFAnonymous bEwTSXJ1gNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Efficacy and Safety of Patient Taking Pregabalin and Desvenlafaxine in Neuropathic PainDocument5 pagesComparison of Efficacy and Safety of Patient Taking Pregabalin and Desvenlafaxine in Neuropathic PainInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Adult Patients DiagnoseDocument14 pagesPatient Reported Outcome Measures in Adult Patients DiagnoseAhmed NuruNo ratings yet

- Abstract - NaKATPase e ParkinsonDocument1 pageAbstract - NaKATPase e Parkinsongeorgia santosNo ratings yet

- Comment: Lancet Neurol 2020Document2 pagesComment: Lancet Neurol 2020dhea nadhiaNo ratings yet

- A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Citalopram in Adolescents With Major Depressive Disorder - Von Knorring 2006Document5 pagesA Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Citalopram in Adolescents With Major Depressive Disorder - Von Knorring 2006Julio JuarezNo ratings yet

- 415 2018 Article 8886Document2 pages415 2018 Article 8886lathifatulNo ratings yet

- Ajp 156 5 702Document8 pagesAjp 156 5 7029 PsychologyNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument16 pagesDaftar PustakaDestrie CindyNo ratings yet

- Nej Mo A 2020214Document14 pagesNej Mo A 2020214Yed HeeNo ratings yet

- Baulac 2016Document12 pagesBaulac 2016Neuro - Clínica de NeurologíaNo ratings yet

- Szeged I 2017Document9 pagesSzeged I 2017rifkadefrianiNo ratings yet

- PR 2021 PlosOne Publ-Online Jan20 1-14Document14 pagesPR 2021 PlosOne Publ-Online Jan20 1-14aditya galih wicaksonoNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Perampanel in Young ChildrenDocument5 pagesEfficacy of Perampanel in Young ChildrenFlavia Angelina SatopohNo ratings yet

- Appi Ajp 2015 15060788Document5 pagesAppi Ajp 2015 15060788marc_2377No ratings yet

- Muscarinic Cholinergic Receptor Agonist and Peripheral Antagonist For Schizophrenia (2021)Document10 pagesMuscarinic Cholinergic Receptor Agonist and Peripheral Antagonist For Schizophrenia (2021)ShadeLRKNo ratings yet

- Clozapine and Haloperidol in ModeratelyDocument8 pagesClozapine and Haloperidol in Moderatelyrinaldiapt08No ratings yet

- dst50234 PDFDocument7 pagesdst50234 PDFtaniaNo ratings yet

- Guideline Watch: Practice Guideline For The Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder, 2Nd EditionDocument9 pagesGuideline Watch: Practice Guideline For The Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder, 2Nd Editionrocsa11No ratings yet

- Guideline Watch: Practice Guideline For The Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder, 2Nd EditionDocument9 pagesGuideline Watch: Practice Guideline For The Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder, 2Nd EditionstefensamuelNo ratings yet

- Dexlansoprazole: A Proton Pump Inhibitor With A Dual Delayed-Release SystemDocument19 pagesDexlansoprazole: A Proton Pump Inhibitor With A Dual Delayed-Release SystemPham TrucNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Parkinson OniDocument5 pagesJurnal Parkinson OniMuhammad Agung SwasonoNo ratings yet

- Safety and Effectiveness of Lurasidone in Adolescents With Schizophrenia: Results of A 2-Year, Open-Label Extension StudyDocument11 pagesSafety and Effectiveness of Lurasidone in Adolescents With Schizophrenia: Results of A 2-Year, Open-Label Extension StudyNaiana PaulaNo ratings yet

- JOURNALDocument10 pagesJOURNALTin NatividadNo ratings yet

- Perampanel in 12 Patients With Unverricht-Lundborg Disease: Full-Length Original ResearchDocument5 pagesPerampanel in 12 Patients With Unverricht-Lundborg Disease: Full-Length Original ResearchFlorian LamblinNo ratings yet

- Infants: Analysis of Systemic Effects and Neonatal Clinical Outcomes Dopamine Versus Epinephrine For Cardiovascular Support in Low Birth WeightDocument12 pagesInfants: Analysis of Systemic Effects and Neonatal Clinical Outcomes Dopamine Versus Epinephrine For Cardiovascular Support in Low Birth WeightJuan Antonio Herrera LealNo ratings yet

- Dopamine Vs EpinephrineDocument11 pagesDopamine Vs EpinephrineAyiek WicaksonoNo ratings yet

- Journal ReadingDocument6 pagesJournal ReadingInka Nadya TriayeshaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Duloxetine On Pain Function and Quality of Life Among Patients With Chemotherapy-Induced Painful Peripheral NeuropathyDocument9 pagesEffect of Duloxetine On Pain Function and Quality of Life Among Patients With Chemotherapy-Induced Painful Peripheral NeuropathypokNo ratings yet

- Ketamine Augmentation Rapidly Improves Depression Scores in Inpatients With Treatment-Resistant Bipolar DepressionDocument6 pagesKetamine Augmentation Rapidly Improves Depression Scores in Inpatients With Treatment-Resistant Bipolar DepressionNfaleNo ratings yet

- Fluoxetine and Clonasapam IonDocument13 pagesFluoxetine and Clonasapam IonPaul Alfred KappNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Ibuprofen Versus Aspirin and Paracetamol On Efficacy and Comfort in Children With FeverDocument5 pagesEvaluation of Ibuprofen Versus Aspirin and Paracetamol On Efficacy and Comfort in Children With FeverlilingNo ratings yet

- PruritusDocument11 pagesPruritusRidho ForesNo ratings yet

- Effect of benfotiamine and pregabalin on carpal tunnel syndromeDocument6 pagesEffect of benfotiamine and pregabalin on carpal tunnel syndromeHomer SimpsonNo ratings yet

- 2604 6180 RMN 22 5 180Document4 pages2604 6180 RMN 22 5 180Sergio Andres Salas CoronelNo ratings yet

- Ixazomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone PDFDocument14 pagesIxazomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone PDFJLNo ratings yet

- CHORLettersandResponsePrincipalPaper VOLAVKA AmJPsych2003Document5 pagesCHORLettersandResponsePrincipalPaper VOLAVKA AmJPsych2003Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- Five Year Follow Up of Bilateral Stimulation of The Subthalamic Nucleus in Advanced Parkinson's DiseaseDocument10 pagesFive Year Follow Up of Bilateral Stimulation of The Subthalamic Nucleus in Advanced Parkinson's DiseaseRicardo GarciaNo ratings yet

- Journal Neuropediatri PDFDocument8 pagesJournal Neuropediatri PDFHalimah PramudiyantiNo ratings yet

- Refractory Epi ManagementDocument4 pagesRefractory Epi Managementjonniwal sanusiNo ratings yet

- Farmacológico AutismoDocument9 pagesFarmacológico AutismoArmando GalvanNo ratings yet

- 2004 Linazasoro Farmacos No Utiles PDDocument12 pages2004 Linazasoro Farmacos No Utiles PDLucasUdovinNo ratings yet

- Levetiracetam in Refractory Pediatric EpilepsyDocument11 pagesLevetiracetam in Refractory Pediatric EpilepsyAdlinaNo ratings yet

- Ni Ketut Somoyani1 JSH V9N1Document6 pagesNi Ketut Somoyani1 JSH V9N1Dian GbligNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2405650218300315 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S2405650218300315 MainDian GbligNo ratings yet

- Binding of Clozapine To The GABA-B Receptor Clinical and StructuralDocument10 pagesBinding of Clozapine To The GABA-B Receptor Clinical and StructuralDian GbligNo ratings yet

- CINP2024 2nd Preliminary AnnouncementDocument2 pagesCINP2024 2nd Preliminary AnnouncementDian GbligNo ratings yet

- A Rational Use of Clozapine Based On Adverse Drug Reactions, Pharmacokinetics, and Clinical PharmacopsychologyDocument15 pagesA Rational Use of Clozapine Based On Adverse Drug Reactions, Pharmacokinetics, and Clinical PharmacopsychologyDian GbligNo ratings yet

- Clonazepam AJPDocument4 pagesClonazepam AJPDian GbligNo ratings yet

- Kennedy 2018 Oi 180182Document10 pagesKennedy 2018 Oi 180182Dian GbligNo ratings yet

- Topiramate For Pediatric Migraine PreventionDocument3 pagesTopiramate For Pediatric Migraine PreventionDian GbligNo ratings yet

- A Guideline and Checklist For Initiating and Managing Clozapine Treatment in Patients With Treatment-Resistant SchizophreniaDocument21 pagesA Guideline and Checklist For Initiating and Managing Clozapine Treatment in Patients With Treatment-Resistant SchizophreniaDian GbligNo ratings yet

- Patrizia Mecocci, Anna Bladstro M and Karina StenderDocument7 pagesPatrizia Mecocci, Anna Bladstro M and Karina StenderDian GbligNo ratings yet

- Topiramate For Seizures in Preterm Infants and The Development of Necrotizing EnterocolitisDocument7 pagesTopiramate For Seizures in Preterm Infants and The Development of Necrotizing EnterocolitisDian GbligNo ratings yet

- LeviDocument11 pagesLeviYulian 53No ratings yet

- Member Masuk 260222Document1 pageMember Masuk 260222Dian GbligNo ratings yet

- Kennedy 2018 Oi 180182Document10 pagesKennedy 2018 Oi 180182Dian GbligNo ratings yet

- CD003154 AbstractDocument4 pagesCD003154 AbstractDian GbligNo ratings yet

- Memantine Improves Cognition and Reduces AnxietyDocument7 pagesMemantine Improves Cognition and Reduces AnxietyDian GbligNo ratings yet

- Efficacy and Safety of Memantine in Patients With Mild To Moderate Vascular DementiaDocument7 pagesEfficacy and Safety of Memantine in Patients With Mild To Moderate Vascular DementiaDian GbligNo ratings yet

- Iuchi 2014Document6 pagesIuchi 2014Dian GbligNo ratings yet

- DBS Masterclass Series - 30 April 2022Document1 pageDBS Masterclass Series - 30 April 2022Dian GbligNo ratings yet

- Lee 2013Document7 pagesLee 2013Dian GbligNo ratings yet

- Citicoline A Superior Form of CholineDocument8 pagesCiticoline A Superior Form of CholineDian GbligNo ratings yet

- Levetiracetam in The Treatment of Childhood EpilepsyDocument14 pagesLevetiracetam in The Treatment of Childhood EpilepsyDian GbligNo ratings yet

- Psychiatrist Goes Labuan BajoDocument2 pagesPsychiatrist Goes Labuan BajoDian GbligNo ratings yet

- Astaxanthin, COVID 19 and Immune Response - Focus On Oxidative Stress, Apoptosis and AutophagyDocument3 pagesAstaxanthin, COVID 19 and Immune Response - Focus On Oxidative Stress, Apoptosis and AutophagyDian GbligNo ratings yet

- Efficacy and Safety of Levetiracetam in Pediatric EpilepsyDocument4 pagesEfficacy and Safety of Levetiracetam in Pediatric EpilepsyDian ArdiansyahNo ratings yet

- Levetiracetam Monotherapy For The Treatment of Infants With EpilepsyDocument5 pagesLevetiracetam Monotherapy For The Treatment of Infants With EpilepsyDian GbligNo ratings yet

- Levetiracetam For Pediatric Prophylactic TreatmentDocument9 pagesLevetiracetam For Pediatric Prophylactic TreatmentDian GbligNo ratings yet

- Levetiracetam in Childhood EpilepsyDocument10 pagesLevetiracetam in Childhood EpilepsyDian GbligNo ratings yet

- Electronic Ticket Receipt: ItineraryDocument2 pagesElectronic Ticket Receipt: ItineraryDian GbligNo ratings yet

- Always Looking Up - The Adventures of An Incurable Optimist - Michael J. Fox-VinyDocument75 pagesAlways Looking Up - The Adventures of An Incurable Optimist - Michael J. Fox-VinyFatima RafiqueNo ratings yet

- NCM 104 Midterm Exams - 1Document21 pagesNCM 104 Midterm Exams - 1Bing58No ratings yet

- Towards New Therapies For Parkinson's DiseaseDocument408 pagesTowards New Therapies For Parkinson's DiseaseAlexandra BalanNo ratings yet

- Long Case Parkinson's DiseaseDocument4 pagesLong Case Parkinson's DiseaseNadia SalwaniNo ratings yet

- Part 1: Terminology, Medications, Lab Tests, Procedures, and Physiology ReviewDocument8 pagesPart 1: Terminology, Medications, Lab Tests, Procedures, and Physiology Reviewapi-496082089No ratings yet

- Postgraduate Prospectus 2011Document244 pagesPostgraduate Prospectus 2011dreathen33No ratings yet

- Pharmacology NeurologicDocument30 pagesPharmacology Neurologicamasoud96 amasoud96No ratings yet

- Extrapyramidal System DisordersDocument41 pagesExtrapyramidal System DisordersAyshe SlocumNo ratings yet

- Parkinson's Disease: Pathophysiology, Signs, TreatmentDocument28 pagesParkinson's Disease: Pathophysiology, Signs, TreatmentJan Michael CorpuzNo ratings yet

- M S N 3Document23 pagesM S N 3Muhammad YusufNo ratings yet

- Assessment, diagnosis, planning, intervention, and evaluation for Parkinson's patientDocument2 pagesAssessment, diagnosis, planning, intervention, and evaluation for Parkinson's patientBenjie DimayacyacNo ratings yet

- Parkinson's DiseaseDocument38 pagesParkinson's DiseaseSofie Dee100% (8)

- Neurology Clerkship UWORLD Guide to Brain Tumors, Strokes & HydrocephalusDocument50 pagesNeurology Clerkship UWORLD Guide to Brain Tumors, Strokes & HydrocephalusHaadi AliNo ratings yet

- Michael J. Fox: Get To Know The Amazing Story BehindDocument5 pagesMichael J. Fox: Get To Know The Amazing Story BehindTRIXIA MAY ELEVADONo ratings yet

- Health - Neurological ImpairmentDocument10 pagesHealth - Neurological ImpairmentMojaro SonNo ratings yet

- Ayurvedic Treatment for Parkinson's DiseaseDocument6 pagesAyurvedic Treatment for Parkinson's DiseaseRPNNo ratings yet

- Dekinet Tablets: Use in PregnancyDocument3 pagesDekinet Tablets: Use in Pregnancyddandan_2No ratings yet

- Movement Disorders - 2022 - Lange - Nomenclature of Genetic Movement Disorders Recommendations of The InternationalDocument38 pagesMovement Disorders - 2022 - Lange - Nomenclature of Genetic Movement Disorders Recommendations of The InternationalAgnes IacobNo ratings yet

- GeriatricsDocument108 pagesGeriatricsQasim AwanNo ratings yet

- Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale: PSSM DPD DPDDocument8 pagesUnified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale: PSSM DPD DPDSebastián GallegosNo ratings yet

- NeurologyDocument46 pagesNeurologyNisini ImanyaNo ratings yet

- Facilitation Technique Sports and ExerciseDocument4 pagesFacilitation Technique Sports and Exerciseapi-339418889No ratings yet

- Jurnal PD 3Document25 pagesJurnal PD 3Jay MNo ratings yet

- Parkinsonism (巴金森氏症) and other movement disordersDocument29 pagesParkinsonism (巴金森氏症) and other movement disordersShing Ming TangNo ratings yet

- Common Diseases in ElderlyDocument14 pagesCommon Diseases in ElderlyNanang Ilham SetyajiNo ratings yet

- Keus Et Al-2007-Movement Disorders PDFDocument10 pagesKeus Et Al-2007-Movement Disorders PDFMaría José Becerra100% (1)

- Norman 2005 Research in Clinical Reasoning Past History and Current TrendsDocument3 pagesNorman 2005 Research in Clinical Reasoning Past History and Current Trendsapi-264671444No ratings yet

- Geriatrics For StudentsDocument88 pagesGeriatrics For StudentsRv DeanNo ratings yet

- Topic 3: American Parkinson's Disease Association CenterDocument2 pagesTopic 3: American Parkinson's Disease Association CenterNurul FatehahNo ratings yet

- Adderall Risks - Much More Than You Wanted To Know - Slate Star CodexDocument21 pagesAdderall Risks - Much More Than You Wanted To Know - Slate Star CodexPatrick LumambaNo ratings yet