Professional Documents

Culture Documents

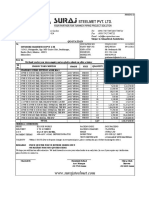

SJ BDJ 2010 398

SJ BDJ 2010 398

Uploaded by

Cristina Rojas RojasOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

SJ BDJ 2010 398

SJ BDJ 2010 398

Uploaded by

Cristina Rojas RojasCopyright:

Available Formats

Resin composite contours IN BRIEF

• Illustrates a highly aesthetic posterior

composite technique.

PRACTICE

H. Sidelsky1 • The technique achieves tight contacts

with correct contour.

• The technique utilises a minimally

VERIFIABLE CPD PAPER invasive approach.

When placing posterior composite resin restorations, clinicians often struggle to achieve good contacts. Frequently con-

tacts that are successful are only confined to the occlusal aspect of the proximal wall. A clinical technique is discussed

which achieves the correct contour as well as tight contacts. The technique is also minimally invasive and highly aesthetic.

INTRODUCTION thereby reproducing the shape of the band. In another in vitro study they examined

In conjunction with bonding agents, tooth Following cavity preparation the band the overhangs that were created when

coloured restorations have replaced amal- was replaced and the wedge inserted to using different matrix band systems.10 They

gam as the material of choice for many re-establish the original contour. concluded that circumferential matrices or

practitioners, for posterior restorations. El Badrawy et al.5 evaluated proximal sectional flexible matrices resulted in the

One dental school has changed from teach- contacts of posterior resin composite resto- least marginal overhang when combined

ing dental amalgams to teaching resin rations with four placement techniques and with a Contact Matrix separation ring or

composites exclusively.1 found that ceramic inserts resulted in the a Composi-Tight Gold ring, but no made

Resin composites have the obvious highest proportion of acceptable contacts. reference to contour.

advantage of aesthetics, which also makes In this study the tightness of the contacts The same investigators found that sec-

them the preferred selection for patients, were assessed subjectively by the examin- tional matrices produced better contacts

and through bonding they are able to ers. No opinion was posited on contour. than circumferential bands in vivo but

reinforce undermined cusps, protecting Francci et al.6 illustrated a novel tech- found that proximal contacts cannot be

them from fracture to a greater extent nique for using packable composite resins relied upon to remain stable over time.11,12

than amalgam.2 in Class II restorations to achieve contour This review of the literature in this area

Due to its better mechanical properties and contact. They suggested forming the confirms that research has concentrated

resin composite is used rather than glass marginal ridge first and then removing the around the tightness of the contacts with

ionomer on occlusal surfaces. band. No description was postulated on reduced concern surrounding the contour

A literature review was conducted by how this achieves the objective of good of the final restoration.

typing into Medline ‘resin composite fill- contour or contact. The aim of this article is to describe a

ings’ and the words ‘contact and contour.’ Loomans et al.7 have carried out many clinical technique which can be used in

Peumans et al.3 found that condensable in vitro studies. When looking at the influ- small to medium sized cavities to produce

resin composites do not achieve better con- ence of composite resin consistency and a good contact and contour.

tacts than conventional resin composites. placement technique on proximal contact

Gonzalez Lopez et al.4 used an individual- tightness, on class II restorations, they DESCRIPTION OF TECHNIQUE

ised wedge modified with resin to achieve found that the use of a separation ring In order to assess the extent of the lesion it

an adequate contact point. They placed had a greater influence than the resin com- is essential to take a bitewing radiograph.

a band preoperatively and injected resin posite on contact tightness. Rubber dam is placed following local

composite around a preplaced wedge. The In comparing proximal contact tightness anaesthesia.

resin composite was cured and withdrawn of class II resin composites they found that The next step is to cut a small piece of

the use of sectional matrices combined with matrix band. This should be large enough

separation rings provided tighter contacts to extend beyond the buccal and lingual

1

2 Devonshire Place, London, W1G 6HJ

than circumferential systems.8 The same interstitial areas.

Correspondence to: Dr Harris Sidelsky authors also looked at proximal contour, The Siqveland matrix band (Dental

Email: harris@harrissidelsky.com

but only on its effect on marginal ridge Directory), more commonly used for amal-

Refereed Paper fracture, and found that the contoured gam placement, is not as thin as other

Accepted 22 February 2010

DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.398

matrix achieved a stronger marginal ridge products but has the advantage of being

© British Dental Journal 2010; 208: 395–401 than the straight matrix.9 able to be placed between the two teeth

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 208 NO. 9 MAY 8 2010 395

© 2010 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved.

PRACTICE

without distortion – this is crucial to the

success of the technique. A pair of Spencer

Wells grips the corner and the band is

forced between the two teeth. On the rare

occasion where the contact is too tight a

wedge can first be placed to separate the

two teeth (Fig. 1). After the band is in place

an anatomically shaped wedge (Cardoza

Dental) is placed between the teeth (Fig. 2).

This has the effect of ensuring there is no

gap between the band and the tooth cer-

vically and at the same time it forces the

adjacent tooth slightly further away from Fig. 1 An anatomical wedge can be used to Fig. 4b Saggital view of the access hole

facilitate band placement

the prepared tooth. It also holds the band

in a firm position.

The end of the wedge is shortened by

breaking off the edge to allow us to place a

Palodent clamp (Optident UK). If the wedge

is inserted at its original length, it might jut

out and prevent the clamp from engaging.

The Palodent clamp is then placed taking

care to engage the teeth (Fig. 3). Placement

of the band as the first step is crucial to

the technique as it allows the band to form

around the contour of the existing intact

approximal wall. Following the cavity

preparation the shape of the band is pre-

served due to its stiffness and the firmness Fig. 2 The matrix band and anatomical Fig. 5a The access hole can be round

wedge are placed

of the contact is further facilitated by the

Palodent clamp.

Figures 4a and 4b show the initial occlu-

sal access cavity. This is placed approxi-

mately 1 mm away for the edge of the

marginal ridge into the fossa. The bur

usually plunges into the lesion and with

magnification one can assess the amount

of caries. Figures 5a and 5b show a very

common presentation of an approximal

wall view of the shape of many interstitial

carious cavities. If the cavity is shaped like

Figure 5b then the bur is moved bucco-

lingualy enlarging the access hole as

necessary to allow further visualisation. Fig. 3 The palodent clamp is placed Fig. 5b The access hole can be rectangular

This facilitates removal of the caries. At

the same time one should try and do this

by preserving the maximum amount of

tooth substance (Fig. 6). If the access cav-

ity resembles the illustration in Figure 5a

then a more limited widening is required.

The caries is removed with a stainless

steel round number 2 or 4 bur. The cavity

is then washed and dried. At this stage

gross caries removal has taken place but

obviously it can be difficult to see the

entire extent of the lesion interstitially. In

the past this has often been the failure of

the ‘tunnel’ preparation. The next step is to Fig. 4a A small access whole is drilled Fig. 6 The access hole is widened

396 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 208 NO. 9 MAY 8 2010

© 2010 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved.

PRACTICE

use a tapered diamond bur (Heraeus Kulzer

bur no 171-016C, Dental Directory) and

carefully remove only the marginal ridge

area above the interstitial cavity. Figure 7

illustrates the ensuing cavity shape.

If the interstitial cavity is circular

(Fig. 5a), then only the marginal ridge above

this cavity is removed. One can often thin

the ridge and then the final removal takes

Fig. 10 The tooth prior to restoration place by breaking the undermined piece.

This will create a cavity shape, illustrated

in Figure 8. If the interstitial cavity is rec-

Fig. 7 The marginal ridge above the cavity is tangular shaped (Fig. 5b), then the cavity

carefully thinned and then broken

is extended by joining the marginal ridge

to the outer point of the rectangle on the

proximal wall. Figures 9a and 9b show how

the cavity may look before and after this

step. This effectively creates a cantilever of

the marginal ridge. Every effort is made to

preserve as much of the marginal ridge as

Fig. 11 Radiograph of distal caries in tooth 45 possible. Where it is extremely thin then

that section of the ridge may be removed

but in most cases this is not the case as the

caries has not penetrated to this area.

It will now be possible to see and

remove all the caries in the cavity using

magnification. Obviously this would only

Fig. 8 Typical appearance of prepared cavity include peripheral caries and infected car-

shape for when original cavity is round

ies but not ‘affected caries’ over the pulp.

As long as the demineralisation process

has not created complete destruction of

tooth form one can often remineralise the

affected dentine.13,14

Fig. 12 The occlusal access cavity is prepared The tooth is then washed well and etched

for ten seconds with orthophosphoric acid.

(Orthophosphoric acid Bisco etch 37%,

Optident UK) which is then washed off and

the tooth is dried. The final appearance

of the dentine is crucial and should not

be too wet or dry. With this in mind it is

usual to gross dry and then useful to use a

paper point to carefully remove the excess

Fig. 9a Appearance prior to modification water. The final appearance of the dentine

should resemble ‘a thumb nail which has

been licked’ (author’s observation).

Fig. 13 The cavity is broadened to gain A resin modified glass ionomer such as

access to caries

Vitrebond, (now known as Vitrebond Plus)

(Espe Dental), is then carefully placed with

a suitable applicator over the exposed den-

tine and set with the curing light.

The whole cavity is then coated with

a bonding agent. Optibond Solo Plus

(KerrHawe UK) is used in case there are any

areas of dentine not adequately covered.

This is cured for 20 seconds. The resin

Fig. 14a The section of matrix band is placed composite is then built up to restore

Fig. 9b Modified cavity and wedged into position the cavity.

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 208 NO. 9 MAY 8 2010 397

© 2010 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved.

PRACTICE

CASE PRESENTATION

All procedures are carried out under rub-

ber dam. Figure 10 shows the tooth before

restorative care. Figure 11 shows the radi-

ograph of the tooth with caries distal in

tooth 45. A small access hole is created

in the occlusal surface until the bur pene-

trates into the caries (Fig. 12). The cavity is Fig. 14b The anatomical wedge is reduced

in size

enlarged according to the clinical findings

with every attempt made to keep the size

minimally. If the caries extends towards the Fig. 19 The caries is removed

mesial then the cavity is enlarged some-

what in that direction. Figure 13 shows the

cavity which has in this case been extended

more buccolingually. Magnification is used

to see the extent of the lesion throughout

the procedure.

A section of a Siqveland molar matrix

band is passed through the contacts. This

can be done before even placing the access

hole. It is easier to place it by holding Fig. 15 The palodent clamp engages the two Fig. 20 Common completed cavity shape

teeth when initial lesion is rectangular

it with a pair of Spencer Wells Artery

Forceps. Note that the band should not

be too wide and should be cut to width

so that it just goes out beyond the outer

limit of the tooth in the buccal and lin-

gual direction (Figs 14a and 14b). An

anatomical wedge is placed after it has

been reduced in size. The largest wedge

possible is used. The reason for reducing

the size is to allow the placement of the Fig. 21 Common occlusal view of completed

cavity

Palodent clamp. If it were to protrude this

would not allow for the placement of the Fig. 16 The tooth is thinned above the initial

cavity

clamp in the most effective way. Figure 15

illustrates the Palodent clamp in situ. It

is important that the clamp engages the

tooth being prepared and the adjacent

tooth on the buccal and the lingual side.

The band is then checked to make sure

there has been no distortion which in this

case is rare because of the sequence car-

ried out and described. The next step is to

carefully thin the marginal ridge above Fig. 22 The tooth is etched

the interstitial cavity. The thinned out

section can then be broken off by using Fig. 17 The thinned wall can be broken with

a PK Thomas 3 instrument

a PK Thomas 3 instrument (PK Thomas

number 3 wax instrument – www.hu-

friedy.de) (Figs 16 and 17). It will now be

possible to see clearly into the cavity and

once this visual access has been gained the

next step is to remove all the caries. This

is accomplished by using a number two,

three or four round tungsten carbide bur

in a slow handpiece. If the original cavity

was of the rectangular shape (Fig. 5b) then

a small excavator can be used to scoop Fig. 18 Visual access has been gained with

minimal damage to the wall Fig. 23 Vitrabond is applied over the dentine

out the caries. One may have to modify

398 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 208 NO. 9 MAY 8 2010

© 2010 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved.

PRACTICE

Once the cavity has been rendered

‘infected caries free’ (one often leaves

‘affected’ caries on the axial wall) the next

step is to restore the tooth.13,14

The tooth is etched (Fig. 22). The etch

is removed by copious washing and the

excess water removed leaving the dentine

moist but not wet. Vitrebond, now known

as Vitrebond Plus, is applied to the exposed

dentine and cured (Fig. 23). The whole cav-

Fig. 28 The completed restoration is ity is then covered with a bonding agent,

aesthetically successful

Optibond Solo Plus, and this is then dried

and cured (Fig. 24). The marginal ridge is

then built up using generic enamel (Enamel

Fig. 24 Bonding agent coats the cavity plus, Optident UK) (Fig. 25). The rest of the

cavity is then incrementally built up tak-

ing into account the ‘C’ factor by placing

and curing a small piece of resin at a time

(Fig. 26).15 This ensures the relief of polym-

erisation stress by permitting the shrink-

age of composite resin into the open space

Fig. 29 The rubber dam is removed and the adjacent to the placed increment. The ‘C’

occlusion checked

factor can be formulated by dividing the

bonded surfaces by the unbonded surfaces

and therefore smaller increments ensure

that this score is low. As well as reducing

sensitivity it also allows the placement of

the anatomy and colour. Figure 27 shows

how one uses the PK Thomas number

Fig. 25 The marginal ridge is built three instrument (HuFriedy) to develop the

final anatomy.

Figure 28 shows the final restoration

Fig. 30 Post-operative radiograph before the rubber dam being removed

and Figure 29 shows the occlusion being

checked following removal of the rubber

dam. Figure 30 is a bitewing radiograph

taken at a routine follow up examina-

tion two years after the initial restoration

was completed.

DISCUSSION

Fig. 31 The contact pro instrument attempts Every practitioner is clinically aware of the

to create contour and contact

problem of establishing a good contact and

contour in direct resin composites. These

Fig. 26 The cavity is filled incrementally the shape of the cavity to gain access to resin composites provide very little inter-

the caries. Again every attempt is made nal force to counter the force applied by

not to remove more marginal ridge than the matrix band, unlike amalgams which

is necessary and this is crucial in main- possess a high force to resist deformation.

taining contour. Magnification is essential This has generated a plethora of tech-

and the whole cavity must be explored. niques and equipment to help overcome

Figures 18 and 19 show the cavity pre- this difficulty.

pared and one can see most of the mar- The tunnel technique attempts to pre-

ginal ridge is still intact. Figures 20 and 21 serve the marginal ridge and axial shape

show an extracted tooth to enable one to in using a minimal invasive approach.16

visualise what the end result often looks Its outstanding aesthetics have made it a

Fig. 27 The final shape is created using a PK like - this view not being possible in our popular approach but considerable doubts

Thomas 3 instrument

case presentation. have emerged in the literature concerning

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 208 NO. 9 MAY 8 2010 399

© 2010 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved.

PRACTICE

its success.17-20.These have centred around missing. Rather the floss is tight at the

recurrent caries at the approximal site and ridge areas then breaks through into space

post placement fracturing marginal ridges. below. This is not so easy to describe but

The slot prep was compared and found to well known to all practitioners who place

be a more reliable alternative.20 resin composite resin restorations and feel

When an amalgam is placed the matrix the difference in contact from that which

band is removed before the material set- is often achieved with a cast laboratory

ting and the restoration springs back and restoration, where contact and contour can

establishes a good contact. Unfortunately be built on a model.

resin composite is set before the band In an attempt to solve this difficult

removal and often leaves a gap between clinical situation a plethora of different

the new restoration and the adjacent bands such as the V ring (Contactpro CEJ

tooth. To overcome this difficulty one Dental, www.cejdental.com), the Palodent

can ‘prewedge’ and separate the two matrix, and the compositight (tight silver

teeth. Following placement of the restora- plus Garrison dental solutions www.gar-

tion the teeth spring back together clos- risondental.com) have entered the dental

ing the space when the band and wedge world. These have been supported but hard

are removed. Alternatively at the time of clinical evidence is lacking.21,22

placement one can apply pressure against Some of these are successful but the

the band to force it against the adjacent clinical consistency is often absent. It is

tooth. This has given birth to instruments often difficult to insert the matrix bands

such as the ‘Contactpro’ (V Ring sectional without altering its shape and frequently

matrix, Triodent) (Fig. 31). burnishing is required to contact the adja-

Many of these techniques at best often cent tooth.

establish a good contact at the marginal This is especially true when the prepa-

ridge area but the approximal wall which ration is minimal. Another scenario is Figs 32a-b Saggital and coronal view of

premolar from Wheeler’s textbook

has been built up often lacks contour. when there has been excessive loss of

Figures 32a and 32b are diagrams from tooth in the mesial or distal areas. This

Wheeler’s textbook of dental anatomy.23 often neutralises the effect of the Palodent

In Figure 32a one can see from the sagit- clamps and similar products as they rely

tal view that from the cervical ridge the on engaging the approximal areas to cre-

tooth curves outwards one millimetre to ate separation.

the contact area and then returns along The ideal situation would be to replace

another curve backwards another 1 mm. the original contour of the tooth. While

Figure 32b illustrates the same curve when the technique described in this article has

viewed from the coronal plane. These are not yet been backed up with any clinical

arcs and not straight lines. The more tooth research its approach and clinical result

substance that is lost cervically the greater experienced by the author support its use.

the problem of restoring the curve of the The principal logic behind the technique is

contour is accentuated. When matrix bands to replicate the contour of the tooth before

are placed and the restoration built up it is beginning cavity preparation. This is done

not uncommon to get a result illustrated by first using a thicker matrix rather than

in Figure 33. When you have a deep cav- the thin variety as this is less likely to

ity the natural tooth tapers and therefore distort following preparation. All efforts

accentuates the curve that is required to are then directed to a minimal invasive

be restored. It is very difficult to seal the technique to preserve this contour. The

matrix band against the floor with a wedge existing contour of the tooth is preserved

and expect the band to then emerge from and the small void created is filled in with

the floor to the marginal ridge with a good resin composite which bonds together the

contour. The red line in Figure 33 shows two sides as well as supporting the remain- Figs 33a-b The red line indicates a

a very common end result with a straight ing wall internally. When post-operative common end product which lacks contour

rather than curved interstitial wall. We see radiographs are taken at follow up routine

after a lot of prewedging contact is often examinations they consistently reveal a

established at the marginal ridge area but satisfactory contour and this is consist- wall contour is largely preserved through

the wall lacks contour. When the floss is ently confirmed clinically with ‘the snap’ this approach. Although previous studies

passed through the contact after placement contact when floss is passed through. This have confirmed that with the tunnel prepa-

the ‘click or snap sound and feel’ is often is facilitated by the fact that the original ration marginal ridge fracture is a common

400 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 208 NO. 9 MAY 8 2010

© 2010 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved.

PRACTICE

failing, this has not yet occurred on any With special thanks: illustrations: Medee Art, marginal overhangs in class II composite resin

www.medeeart.co.uk; dental photography: restorations. J Dent 2009; 37: 712-717.

of the hundreds of restorations placed by Ute Fritsche. 11. Loomans B A, Opdam N J, Roeters F J, Bronkhorst

the author, who hopes to publish these in E M, Plasschaert A J. The long-term effect of a

1. Roeters F J, Opdam N J, Loomans B A. The amal- composite resin restoration on proximal contact

vivo findings in the future. In addition the gam-free dental school. J Dent 2004; 32: 371-377. tightness. J Dent 2007; 35: 104-108. .

repair to a fractured marginal ridge is a 2. Soares P V, Santos-Filho P C, Martins L R, Soares 12. Loomans B A, Opdam N J, Roeters F J, Bronkhorst

J S. Influence of restorative technique on the E M et al. A randomized clinical trial on proximal

quick, inexpensive and simple procedure. biomechanical behaviour of endodontically treated contacts of posterior resin composites. J Dent 2006;

The worst failing with the tunnel technique maxillary premolars. Part 1: fracture resistance and 34: 292-297.

fracture mode. J Prosthet Dent 2008; 99: 30-37. 13. Mount G J. An atlas of glass ionomer cements. A

was secondary caries and this is certainly 3. Peumans M, Van Meerbeek B, Asscherickx K, Simon clinical guide, 3rd ed. Chapter 2 pp 44-49. London:

overcome by virtue of the excellent vision S et al. Do condensable composites help to achieve Martin Dunitz, 1990.

better proximal contacts? Dent Mater 2001; 14. Massler M. Changing concepts in the treatment of

into the cavity described in this article 17: 533-541. carious lesions. Br Dent J 1967; 123: 547-548.

which is often not possible in the tun- 4. González-López S, Bolaños-Carmona M V, Navajas- 15. Feilzer A J, De Gee A J, Davidson C L. Setting stress

Rodríguez de Mondelo J M. Individualized wedge. in resin composite in relation to configuration of

nel technique. Failure in the latter often Oper Dent 2006; 31: 390-393. the restoration. J Dent Res 1987; 66: 1636-1639.

occurs due to lack of the filling material 5. El-Badrawy W A, Leung B W, El-Mowafy O, Rubo 16. Hasselrot L. Tunnel restorations. A 3½ year follow

J H, Rubo M H. Evaluation of proximal contacts up study of class I and class II tunnel restorations

penetrating into the original interstitial of posterior resin composite restorations with 4 in permanent and primary teeth. Swed Dent J 1993;

access hole. placement techniques. J Can Dent Assoc 2003; 17: 173-182.

69: 162-167. 17. Jones S E. The theory and practice of internal

It is recommended that the technique be 6. Francci C, Loguercio A D, Reis A, Carrilho M R. A ‘tunnel’ restorations: a review of the literature and

subjected to further in vitro and in vivo novel filling technique for packable composite resin observations on clinical performance over eight

in Class II restorations. J Esthet Restor Dent 2003; years in practice. Prim Dent Care 1999; 3: 93-100.

research but until that time practitioners 14: 149-157. 18. Strand G V, Tveit A B, Gjerdet N I, Eide G E. Marginal

may wish to see whether they find this 7. Loomans B A, Opdam N J, Roeters J F, Bronkhorst ridge strength of teeth with tunnel preparations.

E M, Plasschaert A J. Influence of resin composite Int Dent J 1995; 45: 117-123.

technique a success. resin consistency and placement technique on 19. Wilkie R, Lidums A, Smales D. Class II glass ionomer

proximal contact tightness of Class II restorations. cermet tunnel, resin sandwich and amalgam resto-

J Adhes Dent 2006; 8: 305-310. rations over 2 years. Am J Dent 1993; 40: 181-184.

SUMMARY 8. Loomans B A, Opdam N J, Roeters F J, Bronkhorst 20. Ratledge D K, Kidd E A, Treasure E T. The tunnel

A minimal invasive, highly aesthetic, clini- E M, Burgersdijk R C. Comparison of proximal con- restoration. Br Dent J 2002; 193: 501-506.

tacts of Class II resin resin composite restorations 21. Strydom C. Handling protocol of posterior resin

cal technique has been presented which in vitro. Oper Dent 2006; 31: 688-693. composites - part 3: matrix systems. SADJ 2006;

9. Loomans B A, Roeters F J, Opdam N J, Kuijs R H. 61: 18, 20-21.

facilitates visualisation of the caries, The effect of proximal contour on marginal ridge 22. Yong W, Zhang R Q. A clinical study of Palodent

allows for its removal and preserves the fracture of class II composite resin restorations. posterior teeth matrix systems. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi

J Dent 2008; 36: 828-832. Xue Za Zhi 2009; 27: 44-48. .

contour of the tooth while establishing 10. Loomans B A, Opdam N J, Roeter F J, Bronkhorst 23. Ash M. Wheeler’s atlas of tooth form, 5th ed. pp

good contact. E M, Huysmans M C. Restoration techniques and 67-68. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co, 1984.

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 208 NO. 9 MAY 8 2010 401

© 2010 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- Lightning Protection of Transmission Lines: Optimal ShieldingDocument9 pagesLightning Protection of Transmission Lines: Optimal ShieldingmaheshwareshwarNo ratings yet

- Manual Omnia Ecici9cicf BfasdipogdpnDocument48 pagesManual Omnia Ecici9cicf BfasdipogdpnGermanoNo ratings yet

- X-Ray Diffraction Topography: International Series in the Science of the Solid StateFrom EverandX-Ray Diffraction Topography: International Series in the Science of the Solid StateNo ratings yet

- Clinical Success in Resin Bonded Bridges PDFDocument7 pagesClinical Success in Resin Bonded Bridges PDFNajeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- Occlusal Splints: Dr. Saloni Dalal, Dr. Omkar Shetty, Dr. Gaurang MistryDocument6 pagesOcclusal Splints: Dr. Saloni Dalal, Dr. Omkar Shetty, Dr. Gaurang MistryNajeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- A Teaching Essay on Residual Stresses and EigenstrainsFrom EverandA Teaching Essay on Residual Stresses and EigenstrainsNo ratings yet

- Plasma Etching Processes for CMOS Devices RealizationFrom EverandPlasma Etching Processes for CMOS Devices RealizationNicolas PossemeNo ratings yet

- All Ceramic Inlays and Onlays For Posterior TeethDocument11 pagesAll Ceramic Inlays and Onlays For Posterior TeethNajeeb Ullah100% (1)

- Adhesive Restoration of Endodontically Treated TeethFrom EverandAdhesive Restoration of Endodontically Treated TeethRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Elastic, Plastic and Yield Design of Reinforced StructuresFrom EverandElastic, Plastic and Yield Design of Reinforced StructuresNo ratings yet

- Cleaning and CorrosionDocument79 pagesCleaning and CorrosionJuly TadeNo ratings yet

- Reservoir Characterization of Tight Gas Sandstones: Exploration and DevelopmentFrom EverandReservoir Characterization of Tight Gas Sandstones: Exploration and DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Treatment Planning Single Maxillary Anterior Implants for DentistsFrom EverandTreatment Planning Single Maxillary Anterior Implants for DentistsNo ratings yet

- Current Therapy in EndodonticsFrom EverandCurrent Therapy in EndodonticsPriyanka JainNo ratings yet

- Fixed Prosthodontics in Dental PracticeFrom EverandFixed Prosthodontics in Dental PracticeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Interceptive Orthodontics: A Practical Guide to Occlusal ManagementFrom EverandInterceptive Orthodontics: A Practical Guide to Occlusal ManagementNo ratings yet

- Short ImplantsFrom EverandShort ImplantsBoyd J. TomasettiNo ratings yet

- Optimal Design of Flexural Systems: Beams, Grillages, Slabs, Plates and ShellsFrom EverandOptimal Design of Flexural Systems: Beams, Grillages, Slabs, Plates and ShellsNo ratings yet

- Granular Materials at Meso-scale: Towards a Change of Scale ApproachFrom EverandGranular Materials at Meso-scale: Towards a Change of Scale ApproachNo ratings yet

- Esthetic Oral Rehabilitation with Veneers: A Guide to Treatment Preparation and Clinical ConceptsFrom EverandEsthetic Oral Rehabilitation with Veneers: A Guide to Treatment Preparation and Clinical ConceptsRichard D. TrushkowskyNo ratings yet

- Contact Lens Design Tables: Tables for the Determination of Surface Radii of Curvature of Hard Contact Lenses to Give a Required Axial Edge LiftFrom EverandContact Lens Design Tables: Tables for the Determination of Surface Radii of Curvature of Hard Contact Lenses to Give a Required Axial Edge LiftNo ratings yet

- Zygomatic Implants: Optimization and InnovationFrom EverandZygomatic Implants: Optimization and InnovationJames ChowNo ratings yet

- Orthodontically Driven Corticotomy: Tissue Engineering to Enhance Orthodontic and Multidisciplinary TreatmentFrom EverandOrthodontically Driven Corticotomy: Tissue Engineering to Enhance Orthodontic and Multidisciplinary TreatmentFederico BrugnamiNo ratings yet

- Constitutive Modeling of Soils and RocksFrom EverandConstitutive Modeling of Soils and RocksPierre-Yves HicherRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Science of Superhydrophobicity: Enhancing Outdoor Electrical InsulatorsFrom EverandThe Science of Superhydrophobicity: Enhancing Outdoor Electrical InsulatorsNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study of Mechanical Properties of Zinc Acrylate Epoxy nanocomposites Reinforced by AL2O3 and Cloisite®30B and Their Mixture: Tensile Strength and Fracture Toughness: A Comparative Study of Mechanical Properties of Zinc Acrylate Epoxy nanocomposites Reinforced by AL2O3 and Cloisite®30B and Their Mixture: Tensile Strength and Fracture ToughnessFrom EverandA Comparative Study of Mechanical Properties of Zinc Acrylate Epoxy nanocomposites Reinforced by AL2O3 and Cloisite®30B and Their Mixture: Tensile Strength and Fracture Toughness: A Comparative Study of Mechanical Properties of Zinc Acrylate Epoxy nanocomposites Reinforced by AL2O3 and Cloisite®30B and Their Mixture: Tensile Strength and Fracture ToughnessNo ratings yet

- The Fatigue Strength of Transverse Fillet Welded Joints: A Study of the Influence of Joint GeometryFrom EverandThe Fatigue Strength of Transverse Fillet Welded Joints: A Study of the Influence of Joint GeometryNo ratings yet

- Minimally Invasive Periodontal Therapy: Clinical Techniques and Visualization TechnologyFrom EverandMinimally Invasive Periodontal Therapy: Clinical Techniques and Visualization TechnologyNo ratings yet

- BridgesDocument3 pagesBridgesNajeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- 3-Dent Update 2014 41 657-657Document2 pages3-Dent Update 2014 41 657-657Najeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- Occlusal MagicDocument1 pageOcclusal MagicNajeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For A Minimum Acceptable Protocol For The Construction of Complete DenturesDocument9 pagesGuidelines For A Minimum Acceptable Protocol For The Construction of Complete DenturesNajeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- Abutment Selection in Fixed Partial Denture - A Review: Drug Invention Today January 2018Document6 pagesAbutment Selection in Fixed Partial Denture - A Review: Drug Invention Today January 2018Najeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- Acetel ResinDocument4 pagesAcetel ResinNajeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- Functional Crown Lengthening Surgical PlanningDocument5 pagesFunctional Crown Lengthening Surgical PlanningNajeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- Different Pontic Design For Porcelain Fused To Metal Fixed Dental Prosthesis: Contemporary Guidelines and Practice by General Dental PractitionersDocument5 pagesDifferent Pontic Design For Porcelain Fused To Metal Fixed Dental Prosthesis: Contemporary Guidelines and Practice by General Dental PractitionersNajeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- The 100 Most Cited Articles in Prosthodontic Journals: A Bibliometric Analysis of Articles Published Between 1951 and 2019Document7 pagesThe 100 Most Cited Articles in Prosthodontic Journals: A Bibliometric Analysis of Articles Published Between 1951 and 2019Najeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- Denture Stomatitis and DMDocument6 pagesDenture Stomatitis and DMNajeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- Newapproachestopain Management: Orrett E. OgleDocument10 pagesNewapproachestopain Management: Orrett E. OgleNajeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- Vertical Movement of Cheek Teeth During BitingDocument10 pagesVertical Movement of Cheek Teeth During BitingNajeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- Interventions To Reduce Stigma Related To Mental Illnesses in Educational Institutes: A Systematic ReviewDocument17 pagesInterventions To Reduce Stigma Related To Mental Illnesses in Educational Institutes: A Systematic ReviewNajeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- Aug Ust 4 September 2020: Fcps-Ii Examination ONDocument2 pagesAug Ust 4 September 2020: Fcps-Ii Examination ONNajeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- Pakistan766 PDFDocument3 pagesPakistan766 PDFNajeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- Vincent Trapozzano, New Portrichey, Fla.,And Gordon Winter, PhiladelphiaDocument7 pagesVincent Trapozzano, New Portrichey, Fla.,And Gordon Winter, PhiladelphiaNajeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- Adverse Effects of Removable Partial Dentures On Periodontal Status and Oral Health of Partially Edentulous PatientsDocument7 pagesAdverse Effects of Removable Partial Dentures On Periodontal Status and Oral Health of Partially Edentulous PatientsNajeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- THE Influence of Partial Denture Design ON DistributionDocument18 pagesTHE Influence of Partial Denture Design ON DistributionNajeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- Abstracts - Zementiert Vs - Zementiert U. Geschraubte Mesostruktur 102010Document10 pagesAbstracts - Zementiert Vs - Zementiert U. Geschraubte Mesostruktur 102010Najeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- PIIS0022391304004056Document1 pagePIIS0022391304004056Najeeb UllahNo ratings yet

- In Touch 2012Document4 pagesIn Touch 2012Juan CarlosNo ratings yet

- Stirlin-1: Lite, Economy & CompactDocument2 pagesStirlin-1: Lite, Economy & CompactWattomaticNo ratings yet

- FWDDocument9 pagesFWDederengNo ratings yet

- Catalogo Emir Joyas Campana 04 - 2024 Hasta Agotar Stock de Catalogos VCQDocument117 pagesCatalogo Emir Joyas Campana 04 - 2024 Hasta Agotar Stock de Catalogos VCQAnnabelle PonceNo ratings yet

- Engenharia PDFDocument11 pagesEngenharia PDFGleison CrispinNo ratings yet

- Relatório Poste A Poste Materiais e Mão de Obra NDS 436557Document5 pagesRelatório Poste A Poste Materiais e Mão de Obra NDS 436557Guilherme A. Morello CagniniNo ratings yet

- Cisco ISE Configuration For SwitchesDocument12 pagesCisco ISE Configuration For SwitchesYahiaKhoujaNo ratings yet

- 1. About Electricians Guide to Conduit Bending Third Edition-PDFDocument186 pages1. About Electricians Guide to Conduit Bending Third Edition-PDFGaudencio BoniceliNo ratings yet

- Din 13-7Document6 pagesDin 13-7kocho79No ratings yet

- BDD VentasDocument28 pagesBDD VentasEduardo ZambranoNo ratings yet

- Brochure de Estudiantes - 2Document32 pagesBrochure de Estudiantes - 2Eduardo ayala IbarraNo ratings yet

- Funciones Del Fluido de Perforación Parte IIDocument10 pagesFunciones Del Fluido de Perforación Parte IIAntonio Subero RuizNo ratings yet

- Polímeros SintéticosDocument12 pagesPolímeros SintéticosEverton VascoutoNo ratings yet

- Electroducto y Buzones LIMADocument2 pagesElectroducto y Buzones LIMAfranksexNo ratings yet

- GY-80 IMU With 3axis Gyro, 3 Axis Accel, 3 Axis Compass & BarometerDocument4 pagesGY-80 IMU With 3axis Gyro, 3 Axis Accel, 3 Axis Compass & BarometerLakshmi AkhilaNo ratings yet

- TR FLEX® Joint Ductile Iron PipeDocument27 pagesTR FLEX® Joint Ductile Iron PipeSopheareak ChhanNo ratings yet

- Guía de Trabajos Prácticos 2020 - TrigonometríaDocument7 pagesGuía de Trabajos Prácticos 2020 - TrigonometríaMilagros OlivieriNo ratings yet

- What Causes Engine Blow-By?: 6 AnswersDocument4 pagesWhat Causes Engine Blow-By?: 6 AnswersAmir Bambang YudhoyonoNo ratings yet

- Amplificador 2x10wDocument78 pagesAmplificador 2x10wHenry Jose Larez RojasNo ratings yet

- Proyecto de Elaboracion de Botellas de Plastico - Procesos III 20509Document40 pagesProyecto de Elaboracion de Botellas de Plastico - Procesos III 20509Esther Cayetano Ramos100% (1)

- Electrical Network Transfer Function PDFDocument14 pagesElectrical Network Transfer Function PDFbalvez nickmarNo ratings yet

- Lista 1em RecDocument2 pagesLista 1em RecMarcelo CardinaliNo ratings yet

- SSQ 2122 205Document1 pageSSQ 2122 205Prathamesh OmtechNo ratings yet

- Is The Make-Buy Decision Process A Core Competence?Document31 pagesIs The Make-Buy Decision Process A Core Competence?Omar AmeenNo ratings yet

- Hard Coating of Tool-Report PDFDocument43 pagesHard Coating of Tool-Report PDFRam TejaNo ratings yet

- Informe de EnzimasDocument6 pagesInforme de EnzimasMily MqrNo ratings yet

- High Voltage Engineering: Qassim UniversityDocument7 pagesHigh Voltage Engineering: Qassim Universityمحمد فرجNo ratings yet