Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Myth of Big, Bad Gluten - The New York Times

Uploaded by

Jorge RissoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Myth of Big, Bad Gluten - The New York Times

Uploaded by

Jorge RissoCopyright:

Available Formats

The Myth of Big, Bad Gluten - The New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/opinion/sunday/the-myth-of-big-ba...

http://nyti.ms/1LP2lY5

SundayReview | OPINION

The Myth of Big, Bad Gluten

By MOISES VELASQUEZ-MANOFF JULY 4, 2015

AS many as one in three Americans tries to avoid gluten, a protein found in wheat,

barley and rye. Gluten-free menus, gluten-free labels and gluten-free guests at

summer dinners have proliferated.

Some of the anti-glutenists argue that we haven’t eaten wheat for long enough to

adapt to it as a species. Agriculture began just 12,000 years ago, not enough time for

our bodies, which evolved over millions of years, primarily in Africa, to adjust.

According to this theory, we’re intrinsically hunter-gatherers, not bread-eaters. If

exposed to gluten, some of us will develop celiac disease or gluten intolerance, or

we’ll simply feel lousy.

Most of these assertions, however, are contradicted by significant evidence, and

distract us from our actual problem: an immune system that has become overly

sensitive.

Wheat was first domesticated in southeastern Anatolia perhaps 11,000 years

ago. (An archaeological site in Israel, called Ohalo II, indicates that people have

eaten wild grains, like barley and wheat, for much longer — about 23,000 years.)

Is this enough time to adapt? To answer that question, consider how some

populations have adapted to milk consumption. We can digest lactose, a sugar in

milk, as infants, but many stop producing the enzyme that breaks it down — called

lactase — in adulthood. For these “lactose intolerant” people, drinking milk can

cause bloating and diarrhea. To cope, milk-drinking populations have evolved a trait

called “lactase persistence”: the lactase gene stays active into adulthood, allowing

1 de 5 07/07/2015 01:50 p.m.

The Myth of Big, Bad Gluten - The New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/opinion/sunday/the-myth-of-big-ba...

them to digest milk.

Milk-producing animals were first domesticated about the same time as wheat

in the Middle East. As the custom of dairying spread, so did lactase persistence.

What surprises scientists today, though, is just how recently, and how completely,

that trait has spread in some populations. Few Scandinavian hunter-gatherers living

5,400 years ago had lactase persistence genes, for example. Today, most

Scandinavians do.

Here’s the lesson: Adaptation to a new food stuff can occur quickly — in a few

millenniums in this case. So if it happened with milk, why not with wheat?

“If eating wheat was so bad for us, it’s hard to imagine that populations that ate

it would have tolerated it for 10,000 years,” Sarah A. Tishkoff, a geneticist at the

University of Pennsylvania who studies lactase persistence, told me.

For Dr. Bana Jabri, director of research at the University of Chicago Celiac

Disease Center, it’s the genetics of celiac disease that contradict the argument that

wheat is intrinsically toxic.

Active celiac disease can cause severe health problems, from stunting and

osteoporosis to miscarriage. It strikes a relatively small number of people — just

around 1 percent of the population. Yet given the significant costs to fitness, you’d

anticipate that the genes associated with celiac would be gradually removed from the

gene pool of those eating wheat.

A few years ago, Dr. Jabri and the population geneticist Luis B. Barreiro tested

that assumption and discovered precisely the opposite. Not only were celiac-

associated genes abundant in the Middle Eastern populations whose ancestors first

domesticated wheat; some celiac-linked variants showed evidence of having spread

in recent millenniums.

People who had them, in other words, had some advantage compared with those

who didn’t.

Dr. Barreiro, who’s at the University of Montreal, has observed this pattern in

many genes associated with autoimmune disorders. They’ve become more common

2 de 5 07/07/2015 01:50 p.m.

The Myth of Big, Bad Gluten - The New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/opinion/sunday/the-myth-of-big-ba...

in recent millenniums, not less. As population density increased with farming, and

as settled living and animal domestication intensified exposure to pathogens, these

genes, which amp up aspects of the immune response, helped people survive, he

thinks.

In essence, humanity’s growing filth selected for genes that increase the risk of

autoimmune disease, because those genes helped defend against deadly pathogens.

Our own pestilence has shaped our genome.

The benefits of having these genes (survival) may have outweighed their costs

(autoimmune disease). So it is with the sickle cell trait: Having one copy protects

against cerebral malaria, another plague of settled living; having two leads to

congenital anemia.

But there’s another possibility: Maybe these genes don’t always cause quite as

much autoimmune disease.

Perhaps the best support for this idea comes from a place called Karelia. It’s

bisected by the Finno-Russian border. Celiac-associated genes are similarly

prevalent on both sides of the border; both populations eat similar amounts of

wheat. But celiac disease is almost five times as common on the Finnish side

compared with the Russian. The same holds for other immune-mediated diseases,

including Type 1 diabetes, allergies and asthma. All occur more frequently in Finland

than in Russia.

WHAT’S the difference? The Russian side is poorer; fecal-oral infections are

more common. Russian Karelia, some Finns say, resembles Finland 50 years ago.

Evidently, in that environment, these disease-associated genes don’t carry the same

liability.

Are the gluten haters correct that modern wheat varietals contain more gluten

than past cultivars, making them more toxic? Unlikely, according to recent analysis

by Donald D. Kasarda, a scientist with the United States Department of Agriculture.

He analyzed records of protein content in wheat harvests going back nearly a

century. It hasn’t changed.

3 de 5 07/07/2015 01:50 p.m.

The Myth of Big, Bad Gluten - The New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/opinion/sunday/the-myth-of-big-ba...

Do we eat more wheat these days? Wheat consumption has, in fact, increased

since the 1970s, according to the U.S.D.A. But that followed an earlier decline. In the

late 19th century, Americans consumed nearly twice as much wheat per capita as we

do today.

We don’t really know the prevalence of celiac disease back then, of course. But

analysis of serum stored since the mid-20th century suggests that the disease was

roughly one-fourth as prevalent just 60 years ago. And at that point, Americans ate

about as much wheat as we do now.

Overlooked in all this gluten-blaming is the following: Our default response to

gluten, says Dr. Jabri, is to treat it as the harmless protein it is — to not respond.

So the real mystery of celiac disease is what breaks that tolerance, and whatever

that agent is, why has it become more common in recent decades?

An important clue comes from the fact that other disorders of immune

dysfunction have also increased. We’re more sensitive to pollens (hay fever), our own

microbes (inflammatory bowel disease) and our own tissues (multiple sclerosis).

Perhaps the sugary, greasy Western diet — increasingly recognized as

pro-inflammatory — is partly responsible. Maybe shifts in our intestinal microbial

communities, driven by antibiotics and hygiene, have contributed. Whatever the

eventual answer, just-so stories about what we evolved eating, and what that means,

blind us to this bigger, and really much more worrisome, problem: The modern

immune system appears to have gone on the fritz.

Maybe we should stop asking what’s wrong with wheat, and begin asking what’s

wrong with us.

Moises Velasquez-Manoff is a science writer and the author of “An Epidemic of

Absence.”

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook and Twitter, and sign up for

the Opinion Today newsletter.

A version of this op-ed appears in print on July 5, 2015, on page SR6 of the New York edition with the

headline: The Myth of Big, Bad Gluten.

4 de 5 07/07/2015 01:50 p.m.

The Myth of Big, Bad Gluten - The New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/opinion/sunday/the-myth-of-big-ba...

© 2015 The New York Times Company

5 de 5 07/07/2015 01:50 p.m.

You might also like

- Missing Microbes: How the Overuse of Antibiotics Is Fueling Our Modern PlaguesFrom EverandMissing Microbes: How the Overuse of Antibiotics Is Fueling Our Modern PlaguesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Food, Genes, and Culture: Eating Right for Your OriginsFrom EverandFood, Genes, and Culture: Eating Right for Your OriginsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Wheat Syndromes: How Wheat, Gluten and ATI Cause Inflammation, IBS and Autoimmune DiseasesFrom EverandWheat Syndromes: How Wheat, Gluten and ATI Cause Inflammation, IBS and Autoimmune DiseasesNo ratings yet

- Five myths about gluten debunkedDocument4 pagesFive myths about gluten debunkedLauren LehmkuhlNo ratings yet

- 1 - Why We Get The World Wrong: Most People Today Wouldn'T Classify Milk As A HealthDocument16 pages1 - Why We Get The World Wrong: Most People Today Wouldn'T Classify Milk As A HealthMarlen MirandaNo ratings yet

- Summary & Study Guide - The Longevity Paradox: How to Die Young at a Ripe Old AgeFrom EverandSummary & Study Guide - The Longevity Paradox: How to Die Young at a Ripe Old AgeNo ratings yet

- The Everyday Wheat-Free and Gluten-Free Cookbook: Recipes for Coeliacs & Wheat IntolerantsFrom EverandThe Everyday Wheat-Free and Gluten-Free Cookbook: Recipes for Coeliacs & Wheat IntolerantsNo ratings yet

- Glyphosate, the Real Culprit Behind Gluten SensitivityFrom EverandGlyphosate, the Real Culprit Behind Gluten SensitivityNo ratings yet

- How to Prevent Food Poisoning: A Practical Guide to Safe Cooking, Eating, and Food HandlingFrom EverandHow to Prevent Food Poisoning: A Practical Guide to Safe Cooking, Eating, and Food HandlingNo ratings yet

- Wheat Belly: Lose the Wheat, Lose the Weight, and Find your Path Back to Health | SummaryFrom EverandWheat Belly: Lose the Wheat, Lose the Weight, and Find your Path Back to Health | SummaryNo ratings yet

- Dr Josh Axe’s Eat Dirt: Why Leaky Gut May Be The Root Cause of Your Health Problems and 5 Surprising Steps to Cure It | SummaryFrom EverandDr Josh Axe’s Eat Dirt: Why Leaky Gut May Be The Root Cause of Your Health Problems and 5 Surprising Steps to Cure It | SummaryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- The Battle for Our Lives: Our Immune System's War Against the Microbes That Aim to Invade UsFrom EverandThe Battle for Our Lives: Our Immune System's War Against the Microbes That Aim to Invade UsNo ratings yet

- Persuasive Essay RCLDocument7 pagesPersuasive Essay RCLapi-317141974No ratings yet

- Consumer's Guide to Probiotics: How Nature's Friendly Bacteria Can Restore Your Body to Super HealthFrom EverandConsumer's Guide to Probiotics: How Nature's Friendly Bacteria Can Restore Your Body to Super HealthNo ratings yet

- Honey Sapiens: Human Cognition and Sugars - the Ugly, the Bad and the GoodFrom EverandHoney Sapiens: Human Cognition and Sugars - the Ugly, the Bad and the GoodNo ratings yet

- Celiac Disease: Real Life Nutrition Strategies to Improve Symptoms and Heal Your GutFrom EverandCeliac Disease: Real Life Nutrition Strategies to Improve Symptoms and Heal Your GutNo ratings yet

- The Gluten Cure: Scientifically Proven Natural Solutions to Celiac Disease and Gluten SensitivitiesFrom EverandThe Gluten Cure: Scientifically Proven Natural Solutions to Celiac Disease and Gluten SensitivitiesNo ratings yet

- Decolonizing the Diet: Nutrition, Immunity, and the Warning from Early AmericaFrom EverandDecolonizing the Diet: Nutrition, Immunity, and the Warning from Early AmericaNo ratings yet

- Healthier Without Wheat: A New Understanding of Wheat Allergies, Celiac Disease, and Non-Celiac Gluten IntoleranceFrom EverandHealthier Without Wheat: A New Understanding of Wheat Allergies, Celiac Disease, and Non-Celiac Gluten IntoleranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (7)

- The Microbiome Solution: a radical new way to heal your body from the inside outFrom EverandThe Microbiome Solution: a radical new way to heal your body from the inside outRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Probiotics - BiocytonicsDocument9 pagesProbiotics - BiocytonicsecioaraujoNo ratings yet

- The Dark Side of WheatDocument77 pagesThe Dark Side of WheatSayer JiNo ratings yet

- Information About CancersDocument8 pagesInformation About CancersBogdan NeguleasaNo ratings yet

- A Joosr Guide to... How Not To Die by Michael Greger with Gene Stone: Discover the Foods Scientifically Proven to Prevent and Reverse DiseaseFrom EverandA Joosr Guide to... How Not To Die by Michael Greger with Gene Stone: Discover the Foods Scientifically Proven to Prevent and Reverse DiseaseNo ratings yet

- Wheat Belly - Summarized for Busy People: Lose the Wheat, Lose the Weight, and Find Your Path Back to HealthFrom EverandWheat Belly - Summarized for Busy People: Lose the Wheat, Lose the Weight, and Find Your Path Back to HealthNo ratings yet

- The OMAD Diet: Intermittent Fasting with One Meal a Day to Burn Fat and Lose WeightFrom EverandThe OMAD Diet: Intermittent Fasting with One Meal a Day to Burn Fat and Lose WeightNo ratings yet

- Great American Diseases: Their Effects on the course of North American HistoryFrom EverandGreat American Diseases: Their Effects on the course of North American HistoryNo ratings yet

- Fighting the Virus: How to Boost Your Immune Response and Fight Viruses and Bacteria Naturally: Essential Spices and Herbs, #14From EverandFighting the Virus: How to Boost Your Immune Response and Fight Viruses and Bacteria Naturally: Essential Spices and Herbs, #14No ratings yet

- For Fork’s Sake: A Quick Guide to Healing Yourself and the Planet Through a Plant-Based DietFrom EverandFor Fork’s Sake: A Quick Guide to Healing Yourself and the Planet Through a Plant-Based DietNo ratings yet

- Good Clean Food: Shopping Smart to Avoid GMOs, rBGH, and Products That May Cause Cancer and Other DiseasesFrom EverandGood Clean Food: Shopping Smart to Avoid GMOs, rBGH, and Products That May Cause Cancer and Other DiseasesNo ratings yet

- Gluten Sensitivity, Coeliac Disease and Brain HealthDocument87 pagesGluten Sensitivity, Coeliac Disease and Brain HealthAmy Ruskoski HendersonNo ratings yet

- Feed Your Genes Right: Eat to Turn Off Disease-Causing Genes and Slow Down AgingFrom EverandFeed Your Genes Right: Eat to Turn Off Disease-Causing Genes and Slow Down AgingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Most Important 60 Days of Your Pregnancy: Prevent Your Child from Developing Diabetes and Obesity Later in LifeFrom EverandThe Most Important 60 Days of Your Pregnancy: Prevent Your Child from Developing Diabetes and Obesity Later in LifeNo ratings yet

- David Perlmutter’s Grain Brain: The Surprising Truth about Wheat, Carbs, and Sugar--Your Brain's Silent Killers SummaryFrom EverandDavid Perlmutter’s Grain Brain: The Surprising Truth about Wheat, Carbs, and Sugar--Your Brain's Silent Killers SummaryRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (6)

- By Kerri Rivera, Kimberly Mcdaniel and Daniel Bender: Healing The Symptoms Known As Autism Second EditionDocument24 pagesBy Kerri Rivera, Kimberly Mcdaniel and Daniel Bender: Healing The Symptoms Known As Autism Second EditionMarilen De Leon EbradaNo ratings yet

- The Paleolithic Diet Its Relative Effectiveness For Overall NutritionFrom EverandThe Paleolithic Diet Its Relative Effectiveness For Overall NutritionNo ratings yet

- Secrets of A Long and Healthy Life Reside in Your Gut Microbiome - New ScientistDocument8 pagesSecrets of A Long and Healthy Life Reside in Your Gut Microbiome - New Scientistchau chiNo ratings yet

- Wheat Belly by Dr. William DavisDocument9 pagesWheat Belly by Dr. William DavissimasNo ratings yet

- PaleoDocument6 pagesPaleoKhorhoiNo ratings yet

- Read U3Document18 pagesRead U3Việt HàNo ratings yet

- 22Q11 DELETION SYNDROMEDocument6 pages22Q11 DELETION SYNDROMELouie Anne Cardines AnguloNo ratings yet

- 86 Research Papers Supporting The Vaccine Autism LinkDocument69 pages86 Research Papers Supporting The Vaccine Autism LinkDanielPerez100% (1)

- Pediatric Fever of Unknown Origin Pediatrics in Reviw 2015Document14 pagesPediatric Fever of Unknown Origin Pediatrics in Reviw 2015AMENDBENo ratings yet

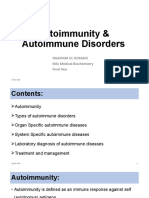

- Unit 3 Part 1 Introduction To Autoimmune DisordersDocument14 pagesUnit 3 Part 1 Introduction To Autoimmune DisordersReman AlingasaNo ratings yet

- IRA 15th Conference 21.-24.9.2008Document57 pagesIRA 15th Conference 21.-24.9.2008shellyrahmaniaNo ratings yet

- 2022 VaccineInjuryTreatmentGuide 4-29-22 FINALDocument26 pages2022 VaccineInjuryTreatmentGuide 4-29-22 FINALYonathan Rojas100% (1)

- 10 Early Signs of LupusDocument3 pages10 Early Signs of LupusJessica RomeroNo ratings yet

- Autoimmunity and DisordersDocument54 pagesAutoimmunity and DisordersInjamam ul hossainNo ratings yet

- Case Report Bipolar Disorder As Comorbidity With Sjögren 'S Syndrome: What Can We Do?Document3 pagesCase Report Bipolar Disorder As Comorbidity With Sjögren 'S Syndrome: What Can We Do?denisaNo ratings yet

- Medical Hypotheses AutismDocument5 pagesMedical Hypotheses AutismOlahdata SpssNo ratings yet

- Mechanisms of Autoimmunity: - Recent ConceptDocument4 pagesMechanisms of Autoimmunity: - Recent ConceptAdhimas Rilo PambudiNo ratings yet

- Spielman Stress and CopingDocument12 pagesSpielman Stress and Coping5676758457No ratings yet

- McqsDocument21 pagesMcqsOsama Bakheet100% (2)

- Case Study 7 8 and 9Document32 pagesCase Study 7 8 and 9Lyca Ledesma JamonNo ratings yet

- Biomedical Research To Improve The Lives of People With Down SyndromeDocument13 pagesBiomedical Research To Improve The Lives of People With Down SyndromeGlobalDownSyndromeNo ratings yet

- Chronic HepatitisDocument19 pagesChronic Hepatitisnathan asfahaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 16 Specific Host Defense MechanismsDocument6 pagesChapter 16 Specific Host Defense MechanismsClark Llamera100% (2)

- How An Anti-Inflammatory Diet Can Help Tame An Autoimmune ConditionDocument6 pagesHow An Anti-Inflammatory Diet Can Help Tame An Autoimmune ConditionsimplyredwhiteandblueNo ratings yet

- Dr. Jean Dodds Responding Exp. Report (Plaintiff)Document24 pagesDr. Jean Dodds Responding Exp. Report (Plaintiff)Osiris-KhentamentiuNo ratings yet

- LP2 MAJOR EXAM 4 Files Merged 2 Files MergedDocument285 pagesLP2 MAJOR EXAM 4 Files Merged 2 Files MergedBianca ArceNo ratings yet

- NataliaRose EmotionalEatingSOSPart1Document21 pagesNataliaRose EmotionalEatingSOSPart1Anu100% (1)

- Readers Digest Asia 08.09 2023-WorldDocument116 pagesReaders Digest Asia 08.09 2023-WorldHuong Zhi SanNo ratings yet

- Prof Djoko - Autoimmune Kidney Disease v2 ENGDocument35 pagesProf Djoko - Autoimmune Kidney Disease v2 ENGlaboratorium spektrumNo ratings yet

- Human Inborn Errors of Immunity: An Expanding Universe: ReviewDocument17 pagesHuman Inborn Errors of Immunity: An Expanding Universe: ReviewCony GSNo ratings yet

- Case Study For Multiple SclerosisDocument4 pagesCase Study For Multiple SclerosisGabbii CincoNo ratings yet

- Ausarbeitung Immunologie A Korrigierte Fassung WS2019Document185 pagesAusarbeitung Immunologie A Korrigierte Fassung WS2019Adrienn MarkeszNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Diagnosis of Hypersensitivity and AutoimmunityDocument41 pagesLaboratory Diagnosis of Hypersensitivity and AutoimmunityDenish Calmax AngolNo ratings yet

- SFA Therapeutics Overview 2 1 2022 OverviewDocument35 pagesSFA Therapeutics Overview 2 1 2022 OverviewIra SpectorNo ratings yet

- Unconventional Medicine Bonus ChapterDocument63 pagesUnconventional Medicine Bonus ChapterDiana-Andreea AnghelNo ratings yet

- Vitamin D in The Treatment of Oral Lichen Planus: A Pilot Clinical StudyDocument6 pagesVitamin D in The Treatment of Oral Lichen Planus: A Pilot Clinical StudyDr.Doyel RoyNo ratings yet