Professional Documents

Culture Documents

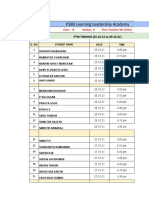

Upper-Intermediate Structure Mid-Term Test

Upper-Intermediate Structure Mid-Term Test

Uploaded by

Moch. NaufalOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Upper-Intermediate Structure Mid-Term Test

Upper-Intermediate Structure Mid-Term Test

Uploaded by

Moch. NaufalCopyright:

Available Formats

In late 1992, Quentin Tarantino left Amsterdam, where he had spent three months, off

and on, in a one-room apartment with no phone or fax, writing the script that would

become Pulp Fiction, about a community of criminals on the fringe of Los Angeles.

Written in a dozen school notebooks, which the 30-year-old Tarantino took on the plane

to Los Angeles, the screenplay was a mess—hundreds of pages of indecipherable

handwriting. “It was about going over it one last time and then giving it to the typist,

Linda Chen, who was a really good friend of mine,” Tarantino tells me. “She really

helped me.”

When Tarantino met Chen, she was working as a typist and unofficial script consultant

for Robert Towne, the venerable screenwriter of, most notably, Chinatown. “Quentin

was fascinated by the way I worked with Towne and his team,” she says, explaining that

she “basically lived” at Towne’s condominium, typing, researching, and offering

feedback in the preparation of his movie The Two Jakes. “He would ask the guys for

advice, and if they were vague or disparate, he would say, ‘What did the Chink think?’ ”

she recalls. “Quentin found this dynamic of genius writer and secret weapon amusing.

“It began with calls where he was just reading pages to me,” she continues. Then came

more urgent calls, asking her to join him for midnight dinners. Chen always had to pick

him up, since he couldn’t drive as a result of unpaid parking tickets. She knew Tarantino

was a “mad genius.” He has said that his first drafts look like “the diaries of a madman,”

but Chen says they’re even worse. “His handwriting is atrocious. He’s a functional

illiterate. I was averaging about 9,000 grammatical errors per page. After I would

correct them, he would try to put back the errors, because he liked them.”

The producer, Lawrence Bender, and TriStar Pictures, which had invested $900,000 to

develop the project, were pressing Tarantino to deliver the script, which was late. Chen,

who was dog-sitting for a screenwriter in his Beverly Hills home, invited Tarantino to

move in. He arrived “with only the clothes on his back,” she says, and he crashed on the

couch. Chen worked without pay on the condition that Tarantino would rabbit-sit

Honey Bunny, her pet, when she went on location. (Tarantino refused, and the rabbit

later died; Tarantino named the character in Pulp Fiction played by Amanda Plummer

in homage to it.)

His screenplay of 159 pages was completed in May 1993. “On the cover, Quentin had me

type ‘MAY 1993 LAST DRAFT,’ which was his way of signaling that there would be no

further notes or revisions at the studio’s behest,” says Chen.

“Did you ever feel like you were working on a modern cinematic masterpiece?,” I ask.

“Not at all,” she replies. However, she did go on to be the unit photographer on the film.

When Pulp Fiction thundered into theaters a year later, Stanley Crouch in the Los

Angeles Times called it “a high point in a low age.” Time declared, “It hits you like a shot

of adrenaline straight to the heart.” In Entertainment Weekly, Owen Gleiberman said it

was “nothing less than the reinvention of mainstream American cinema.”

Made for $8.5 million, it earned $214 million worldwide, making it the top-grossing

independent film at the time. Roger Ebert called it “the most influential” movie of the

1990s, “so well-written in a scruffy, fanzine way that you want to rub noses in it—the

noses of those zombie writers who take ‘screenwriting’ classes that teach them the

formulas for ‘hit films.’ ”

Pulp Fiction resuscitated the career of John Travolta, made stars of Samuel L. Jackson

and Uma Thurman, gave Bruce Willis new muscle at the box office, and turned Harvey

and Bob Weinstein, of Miramax, into giants of independent cinema. Harvey calls it “the

first independent movie that broke all the rules. It set a new dial on the movie clock.”

“It must be hard to believe that Mr. Tarantino, a mostly self-taught, mostly untested

talent who spent his formative years working in a video store, has come up with a work

of such depth, wit and blazing originality that it places him in the front ranks of

American filmmakers,” wrote Janet Maslin in The New York Times. “You don’t merely

enter a theater to see Pulp Fiction: you go down a rabbit hole.” Jon Ronson, critic

for The Independent, in England, proclaimed, “Not since the advent of Citizen Kane …

has one man appeared from relative obscurity to redefine the art of movie-making.”

“I Watch Movies”

You might also like

- The Craft of Scene Writing: Beat by Beat to a Better ScriptFrom EverandThe Craft of Scene Writing: Beat by Beat to a Better ScriptRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Fade in The Writing of Star Trek InsurrectionDocument271 pagesFade in The Writing of Star Trek InsurrectionreoloxNo ratings yet

- Pulp AestheticsDocument59 pagesPulp AestheticsArturo SerranoNo ratings yet

- My Best Friend’s Birthday: The Making of a Quentin Tarantino FilmFrom EverandMy Best Friend’s Birthday: The Making of a Quentin Tarantino FilmNo ratings yet

- If You Like Quentin Tarantino...: Here Are Over 200 Films, TV Shows and Other Oddities That You Will LoveFrom EverandIf You Like Quentin Tarantino...: Here Are Over 200 Films, TV Shows and Other Oddities That You Will LoveNo ratings yet

- All About All About Eve: The Complete Behind-the-Scenes Story of the Bitchiest Film Ever Made!From EverandAll About All About Eve: The Complete Behind-the-Scenes Story of the Bitchiest Film Ever Made!Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (40)

- The First Deadly SinDocument3 pagesThe First Deadly Sinbhargav470No ratings yet

- Hans-Jürgen Syberberg, The Film Director As Critical ThinkerDocument273 pagesHans-Jürgen Syberberg, The Film Director As Critical Thinkervictorychimp100% (2)

- Cinema TarantinoDocument29 pagesCinema TarantinoSambit Kumar PradhanNo ratings yet

- Fiction: Cinema Tarantino: The Making of PulpDocument18 pagesFiction: Cinema Tarantino: The Making of PulpThiago Franzen AydosNo ratings yet

- FLM 1023 Research EssayDocument5 pagesFLM 1023 Research Essayapi-220353482No ratings yet

- The Auteur TheoryDocument8 pagesThe Auteur Theoryapi-258949253No ratings yet

- The Film That Changed My Life: 30 Directors on Their Epiphanies in the DarkFrom EverandThe Film That Changed My Life: 30 Directors on Their Epiphanies in the DarkNo ratings yet

- Quentin TarantinoDocument5 pagesQuentin Tarantinoapi-689727246No ratings yet

- Francis Ford CoppolaDocument24 pagesFrancis Ford CoppolaEmil WhiteNo ratings yet

- The Keys To My HeartDocument6 pagesThe Keys To My HeartPaul Thomas EvansNo ratings yet

- All the Best Lines: An Informal History of the Movies in Quotes, Notes and AnecdotesFrom EverandAll the Best Lines: An Informal History of the Movies in Quotes, Notes and AnecdotesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Tim AND MonichDocument8 pagesTim AND MonichMilesh ShelimNo ratings yet

- The Nice and Accurate Good Omens TV CompanionFrom EverandThe Nice and Accurate Good Omens TV CompanionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (28)

- The CharactersDocument2 pagesThe CharactersmiosmNo ratings yet

- Mr. Huston/ Mr. North: Life, Death, and Making John Huston's Last FilmFrom EverandMr. Huston/ Mr. North: Life, Death, and Making John Huston's Last FilmNo ratings yet

- Uma ThurmanDocument8 pagesUma ThurmanZelen BorNo ratings yet

- The Screenplay As Literature: A Case Study of Harold PinterDocument14 pagesThe Screenplay As Literature: A Case Study of Harold PinterMęawy MįlkshãkeNo ratings yet

- Quentin Tarantino and The Poetry Between The Lines: IntroDocument46 pagesQuentin Tarantino and The Poetry Between The Lines: IntroSergio AntibioticeNo ratings yet

- Chatting With Sam HendersonDocument4 pagesChatting With Sam HendersonEdward Carey100% (1)

- Waiting To Exhale Premiere Dec 1995 SouthgateDocument3 pagesWaiting To Exhale Premiere Dec 1995 SouthgateMartha SouthgateNo ratings yet

- Who Done It: Rosemarie KeenanDocument4 pagesWho Done It: Rosemarie KeenanVirat PalNo ratings yet

- Eval EvalDocument24 pagesEval Evalapi-632031444No ratings yet

- My Life as a Mankiewicz: An Insider's Journey Through HollywoodFrom EverandMy Life as a Mankiewicz: An Insider's Journey Through HollywoodNo ratings yet

- Method Writing - TarantinoDocument17 pagesMethod Writing - TarantinoAlokRanjan100% (2)

- Background On Guys DollsDocument3 pagesBackground On Guys Dollsapi-463162159100% (1)

- Fade inDocument270 pagesFade inPeter BirdsallNo ratings yet

- Sepinwall On Mad Men and Breaking Bad: An eShort from the Updated Revolution Was TelevisedFrom EverandSepinwall On Mad Men and Breaking Bad: An eShort from the Updated Revolution Was TelevisedRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- John Milius PDFDocument16 pagesJohn Milius PDFkdefreitas704No ratings yet

- Quentin Tarantino: The Inglourious: Basterds InterviewDocument8 pagesQuentin Tarantino: The Inglourious: Basterds Interviewapi-16771535No ratings yet

- Tom HanksDocument10 pagesTom HankseeqdNo ratings yet

- Harold Pinter: The Art of Theater 3Document27 pagesHarold Pinter: The Art of Theater 3Branko VranešNo ratings yet

- The Artist Production NotesDocument49 pagesThe Artist Production NotesRanadeep BhattacharyyaNo ratings yet

- The Cinema of Cruelty: From Buñuel to HitchcockFrom EverandThe Cinema of Cruelty: From Buñuel to HitchcockRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Dracula Meets Jack the Ripper and Other Revisionist HistoriesFrom EverandDracula Meets Jack the Ripper and Other Revisionist HistoriesNo ratings yet

- Frank Millers StilDocument2 pagesFrank Millers Stiljuergi56No ratings yet

- The Horror Guys Guide to The Horror Films of Vincent Price: HorrorGuys.com Guides, #5From EverandThe Horror Guys Guide to The Horror Films of Vincent Price: HorrorGuys.com Guides, #5No ratings yet

- Tell Them It's a Dream Sequence: And Other Smart Advice from Top FilmmakersFrom EverandTell Them It's a Dream Sequence: And Other Smart Advice from Top FilmmakersNo ratings yet

- David Hare (The Hours The Reader, and More)Document9 pagesDavid Hare (The Hours The Reader, and More)William J LeeNo ratings yet

- Paris Review - Billy Wilder, The Art of Screenwriting No. 1Document15 pagesParis Review - Billy Wilder, The Art of Screenwriting No. 1Bogdan Theodor OlteanuNo ratings yet

- Three Days of The CondorDocument5 pagesThree Days of The CondorbillNo ratings yet

- Imitation Woody: A Guide To Allenesque Movies Made by Other PeopleDocument43 pagesImitation Woody: A Guide To Allenesque Movies Made by Other PeopleAntonieta HernandezNo ratings yet

- Excerpt From 'Mad Men Carousel' by Matt Zoller SeitzDocument10 pagesExcerpt From 'Mad Men Carousel' by Matt Zoller SeitzAbrams BooksNo ratings yet

- LGHOR Volume 5 Issue 1 Pages 167-184Document18 pagesLGHOR Volume 5 Issue 1 Pages 167-184Moch. NaufalNo ratings yet

- Final-Test Business Writing (Muhammad Agus Pamungkas)Document5 pagesFinal-Test Business Writing (Muhammad Agus Pamungkas)Moch. NaufalNo ratings yet

- Shad Ford Paper RevDocument39 pagesShad Ford Paper RevMoch. NaufalNo ratings yet

- Strategies For The Listening Part A QuestionsDocument7 pagesStrategies For The Listening Part A QuestionsMoch. NaufalNo ratings yet

- IT RETURNS (It: Chapter 2)Document32 pagesIT RETURNS (It: Chapter 2)Moch. NaufalNo ratings yet

- Much Ado About NothingDocument10 pagesMuch Ado About Nothingmegea75No ratings yet

- KMC Batch Coordinator's ListDocument4 pagesKMC Batch Coordinator's Listpriya selvaraj100% (1)

- Dela Cruz, Heart Marie M - Film Analysis - The Grand Budapest HotelDocument7 pagesDela Cruz, Heart Marie M - Film Analysis - The Grand Budapest HotelHeart Marie Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Film ReviewDocument2 pagesFilm ReviewIlija ĐorđevićNo ratings yet

- Recuitment (Keonics) KannadaDocument567 pagesRecuitment (Keonics) KannadaShekharNo ratings yet

- Emaar Emerald Estate A-DDocument54 pagesEmaar Emerald Estate A-DVikas Vasisht33% (3)

- Robertrodriguezresume 3-2012 As RevDocument2 pagesRobertrodriguezresume 3-2012 As Revapi-123223435No ratings yet

- Mythological Wanted List 2009Document5 pagesMythological Wanted List 2009godofpathosNo ratings yet

- Class Xi D PTM ScheduleDocument4 pagesClass Xi D PTM ScheduleAdore MeghnaNo ratings yet

- Dundee Theater - WikipediaDocument5 pagesDundee Theater - WikipediabNo ratings yet

- Cinema & SocietyDocument5 pagesCinema & SocietyTareq AhmedNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument21 pagesNew Microsoft Office Word Documentgud2seeu100% (3)

- 500 AllDocument13 pages500 Alldharamveersinghsolanki244No ratings yet

- Remembering Charles WolcottDocument1 pageRemembering Charles WolcottKDK FactoryNo ratings yet

- MPAA BVSDocument2 pagesMPAA BVSGotham City Informer100% (2)

- Cause List 08.06.2023Document4 pagesCause List 08.06.2023Prakash VenkataramaniNo ratings yet

- Comm 130 Chapter 7 - Movies The Beauty of MoviesDocument11 pagesComm 130 Chapter 7 - Movies The Beauty of MoviesTori DeatherageNo ratings yet

- 21346MT (T) List PDFDocument1,381 pages21346MT (T) List PDFSakti SwainNo ratings yet

- Tarun Geotechnical LabDocument8 pagesTarun Geotechnical LabNehaSharmaNo ratings yet

- PH.D Environment and Natural ResourcesDocument5 pagesPH.D Environment and Natural Resourcessachin rawatNo ratings yet

- Final List of Volunteers and Resource Persons ForDocument68 pagesFinal List of Volunteers and Resource Persons ForWipro Foundation KARNo ratings yet

- Tntet 2013 Paper I Districtwise Provisional Mark List With 5% Relaxation in Qualifying MarksDocument27 pagesTntet 2013 Paper I Districtwise Provisional Mark List With 5% Relaxation in Qualifying MarksrajrudrapaaNo ratings yet

- Snehal MakoteDocument20 pagesSnehal MakoteRiya GupteNo ratings yet

- Roll No. Name Category: Waiting ListDocument5 pagesRoll No. Name Category: Waiting ListOmkesh PanchalNo ratings yet

- ShayariDocument14 pagesShayariPreksha SethNo ratings yet

- The Movie BookDocument354 pagesThe Movie Booklephuongvnu100% (21)

- Facts About Amit KumarDocument1 pageFacts About Amit Kumarsritesh0No ratings yet

- Jo Tum Na Ho - YouTubeDocument10 pagesJo Tum Na Ho - YouTubeJeet PatilNo ratings yet

- 23 Home EntDocument24 pages23 Home EntAlakchchendra SinghNo ratings yet