Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Insights Into Housing Affordability For Rural Low Income Families

Uploaded by

Deodorant de araujo jeronimoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Insights Into Housing Affordability For Rural Low Income Families

Uploaded by

Deodorant de araujo jeronimoCopyright:

Available Formats

Housing and Society

ISSN: 0888-2746 (Print) 2376-0923 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rhas20

Insights into Housing Affordability for Rural Low-

Income Families

Jessica N. Kropczynski & Patricia H. Dyk

To cite this article: Jessica N. Kropczynski & Patricia H. Dyk (2012) Insights into Housing

Affordability for Rural Low-Income Families, Housing and Society, 39:2, 125-148, DOI:

10.1080/08882746.2012.11430603

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/08882746.2012.11430603

Published online: 09 Jun 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 132

View related articles

Citing articles: 3 View citing articles

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rhas20

Kropczynski, Dyk 125

INSIGHTS INTO HOUSING AFFORDABILITY FOR

RURAL LOW-INCOME FAMILIES

Jessica N. Kropczynski, Patricia H. Oyk

Abstract

Many nonprofits and government entities model the standard for housing

affordability set by the United States Department of Housing and Urban

Development (HUD, which states that housing costs in excess of3096 ofgross

household income are unaffordable. Families require a minimum level ofbasic

consumption after housing costs are made which must then be purchased with

the remaining 7096 oftheir gross income. Hence, an increasing number ofstudies

have examined how these competing needs factor into the government equation

for housing affordability using national datasets. '!his study uses data from the

Rural Families Speak project, a multi-state research project focused on rural,

low-income families with children. '!he percent of income families spent on

housing is compared to their ability to fo!fill basic needs to answer the question:

Do low-income rural families that are not housing cost burdened perceive

themselves to be able to meet more basic needs than families that are housing cost

burdened according to the government standard? By incorporating measures of

perceived fo!fillment of basic needs, the understanding of affordability can be

broadened to include the challenging circumstances ofrural areas.

Keyword.: affordability, rural hOUSing, low-income.

Introduction

This study contributes to the literature on the government standard

of housing affordability as it applies to rural U.S. families by answering the

question: Do rural families with affordable housing by the government's

standard perceive themselves to be able to meet their basic needs? In a time of

Jessica N. Kropczynski (corresponding author) is a doctoral candidate in sociology, in the Department of Sociology,

University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY. Patricia H. Dyk is the Director of the Center for Leadership Development,

in the Department of Community & Leadership Development and Department of Sociology, University of Kentucky,

Lexington, KY.

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, Volume 39, Issue 2, Pages 125-148.

Copyright © 2012 Housing Education and Research Association

All rights of reproduction in any form reserved. ISSN: 0888-2746.

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

126· Housing Affordability for Rural Low-Income Families

economic crisis, advocates for low-income families point to standards of living

which include varying basic needs while simultaneously trying to keep up with

policies that provide aid for those needs. The U.S. Department of Housing and

Urban Development (HUD) uses a common standard of affordability which

has been adopted by many government and non-profit organizations. HUD

has developed the Housing Affordability Data System (HAOS) which uses

a government standard of affordability, stating that housing is affordable if

a household is spending no more than 30% of its gross income on housing

costs (Vandenbroucke, 2007). Due to differences of geographic affordability ·

and community structure based on region, this study investigates housing

affordability within the context of the rural U.S. family.

While housing affordability is a topic familiar to researchers, the

government standard of affordability is a topic less frequently questioned.

Within the policy domain, the standard of housing affordability has only been

changed a small number of times and rarely reflects research of the time. A

historical perspective of the infrequent changes to the government standard of

housing affordability is included in the literature review. This research also builds

on previous work which questions the capacity to measure housing affordability

through standardized measurement tools by examining rural families' ability to

meet their basic needs with and without housing assistance and comparing it

to the cost burden status of the household. We begin by exploring a number of

affordability indices, describe how the most widely used definition of housing

affordability was adopted, provide an overview of theoretical applications for

housing needs, and describe challenges rural families face while making ends

meet. We then use data from the Rural Families Speak project to illustrate

difficulties in measuring rural household affordability. Finally, we delineate our

conclusions and the policy implications of this research.

Affordability Indices

A recent review of housing indices by Jewkes and Delgadillo (2010)

reported 12 housing affordability indices for both renters and homeowners, but

narrowed their review to the three most used: the HUD affordability index

for homeowners and renters, the National Low Income Housing Coalition

Affordability Index for renters, and the National Association of Realtors

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

Kropczynski, Dyk • 127.

Affordability Index for homeowners. The first two are grounded in the same

rule of thumb based on the 30% ratio of gross income spent on housing. The

National Low Income Housing Coalition (2006) indicates having used a

number of measures of housing affordability, but admits that while measures

vary, they are all grounded in a "rule of thumb" that if a household spends more

than a specified percentage of its income on housing it is unaffordable.The 30%

rule of thumb remains to be the most widely specified percent of income used

by practitioners, non-profit organizations, lenders, counseling agencies, city

council members, and legislators (Jewkes & Delgadillo, 2010; Pelletiere, 2008)

and is even described as a "public policy lexicon" (Schwartz & Wilson, 2006,

p. 2). The National Association of Home Builders has developed a Housing

Opportunity Index based on median income of metropolitan statistical areas

(Torluccio & Dorakh, 2011). Due to the fact that median incomes tend to be

higher in metropolitan areas and a variety of housing options are more available,

this measure is limited in its ability to be generalizable to rural areas.

In addition to measures that are currently in practice, it is important to

note that researchers have proposed a number of new measures based on estimates

of commonly used data, many of which emphasize what a family can afford after

housing payments. Stone's shelter poverty concept (1993) considered a family to

be shelter poor if it pays too much on housing to afford the minimum adequate

level of non-household consumption. Combs, Combs and Ziebarth (1995)

used a similar measure they refer to as "housing burden" based on the poverty

threshold and concluded that if a household spends more than 30% ofits income

on housing, and less than 700Al of the poverty budget is remaining, it is in need

of housing assistance. Responding to Stone (1993), Kutty (2005) adjusted shelter

poverty bearing similarity to "housing burden," to show that near-poor renters

often fall into housing-induced poverty after paying for housing and limits their

ability to purchase basic needs. Stone (2006) later recommended an approach

that would take into consideration household size and geographic location while

recognizing that non-housing expenditures are limited by how much is left after

paying for housing. Broader recommendations for changes include Jewkes and

Delgadillo (2010) who stated that housing practitioners would benefit by utilizing

an adapted residual income approach that considers household size, geographic

location, transportation, and non-housing related expenses.

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

128· Housing Affordability for Rural Low-Income Families

Since the HUD standard is still the most widely used of these standards,

our analysis places particular emphasis on the 30% cost burden status while

evaluating the number of needs met and other proposed measures. The next

section describes the history of the 30% standard and how it came to be the

public policy lexicon that it is today.

Origins ofthe HUD SlIIndard

Over time, thresholds of the housing cost-to-income ratio have been set

at 25%, 30%, 40%, and 50%. The following is a non-comprehensive description

of the series of transitions that have shaped this rule of thumb. The standard

of affordability has undergone many iterations dating back to the 1800s. These

percent of income measures have been criticized for not being research based

(Mimura, 2008), however these measures would be better described as based

on out-of-date research that has been augmented to meet policy needs. Ernst

Engel conducted the first housing affordability study by statistically analyzing

housing cost data in England in the 1860s and concluded that no matter their

income, families spend roughly the same percentage of income on housing

(Pelletiere, 2008). Engel's research showed that families spent roughly 14%

of income on utilities and rent across three family categories: those receiving

public assistance, those struggling but do not receive assistance, and those who

were "comfortable."

A short time later in 1875, the Labor Statistics Commissioner in

Massachusetts, Carrol Wright, translated portions of Engel's work into his own

research. Primarily, Wright focused on the statement that the ratio of gross

income spent on housing "is approximately the same, whatever the income" and

went on to disprove this statement showing that families with smaller budgets

spend nearly 26% of income on housing while those with larger budgets tended

to spend 15% of their budget on housing. Several studies through the turn of

the century found similar results concluding that few families paid more than

25% of their income on housing and most spent considerably less (Feins &

Lane 1981; Stigler, 1954). An empirical consensus emerged around this time

in the early 1900s that it was the norm for working class households to spend

roughly "a week's wages for a month's rent" (Feins & Lane, 1981, p. 9). While

the 25% rule of thumb grew in citation, Engel's Law that households of ranging

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

Kropczynski, Dyk • 129

incomes spend the same ratio of income on housing was not widely accepted

(Stigler, 1954). The 25% rule of thumb was underwritten into the nation's

housing policy during the creation of the Federal Housing Administration as a

way to assess need.

While many articles indicate the laws that changed the percent of

income threshold from 25% (Hulchanski, 1995; Kutty, 2005; O'Dell, Smith,

& White, 2004), few elaborate on the historical context. Pelletiere (2008) and

Mark Shroder, the HUD Associate Deputy Assistant Secretary for Research

Evaluation and Monitoring, have provided the following context for establishing

this turn of the century research into practice. Pelletiere (2008) describes

the birth of federal low income housing policy in 1937 to have determined

housing need using the 25% rule of thumb. Later, operating and maintenance

costs rose over the next 30 years, and some tenants were paying as much as

80% of their income on housing. According to Mark Shroder (M. Shroder,

personal communication, January 28, 2008), when public housing was first

developed in the United States around the time of the Great Depression, each

local public housing authority (PHA) was responsible for raising the funds to

pay building maintenance. Over time, PHAs began raising rent to maintain

habitability, leaving tenants financially burdened and struggling to afford low-

income housing. To prevent further rent increases for tenants living in public

housing, in 1968, rent was limited to not more than 25% of a tenant's income

and mandated that the federal government would cover costs above that level.

Originally intended as a cost ceiling, this law was soon treated as a standard

rate by nearly all PHAs due to difficulties obtaining federal supplementation.

In 1981, the Reagan administration persuaded Congress to raise the rate from

25% to 30% in order to reduce the federal contribution. This legislation was

also designed to ensure that housing assistance would be better targeted toward

those most in need. Middle-class Americans at that time were falsely thought

to spend well under 30% of their income on housing. In 1983, the Housing and

Urban-Rural Recovery Act added consideration of those experiencing housing

costs that were over 50% of income and made the 30% rule applicable to all

current rental housing assistance programs.

Today, a contrived application of Engel's Law exists wherein families

with monthly housing payments (whether it be for rent or mortgage, including

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

130· Housing Affordability for Rural Low-Income Families

utilities) totaling more than 30% of their monthly pre-tax income are considered

housing cost burdened and those totaling more than 50% are considered severely

cost burdened. This standard is not without utility, as it provides a framework

for housing discussion. The Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard

University (JCHS, 2005) indicated that as of 2003 nearly 70% of low wage

workers, elderly and disabled households and others in the bottom quartile were

cost burdened. Their most recent report (JCHS, 2012) further specified that

between 2007 and 2010, the number of severely cost burdened households in

the United States rose by 2.3 million, bringing the total to 10.7 million. In 1995,

Hulchanski published a review of uses of the 30% rule that indicated both cause

for alarm and utility of the standard. These uses included: comparative analysis

by researchers, eligibility standards for assistance, assessing need for additional

affordable housing, ability to pay for mortgage, and eligibility for mortgages

(Hulchanski, 1995). Hulchanski ultimately concluded that this ratio of income

spent on housing has many utilities, but using it as the definition for housing

affordability is not one of them. According to Eggers and Moumen (2008), an

ever-growing crisis has developed due to the fact that national housing costs

are reportedly increasing at three times the rate of national wages. According to

the Consumer Price Index produced by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS),

this exponential increase in housing costs was a 30% increase above that of all

other items between 1985 and 2005 (Eggers & Moumen, 2008).

Along the same logic as Stone (1993,2006) and Kutty (2005), given

that 30% ofincome is to be spent on housing, it follows that a family should be

able to purchase all other basic needs with the remaining 70% of income. The

Consumer Expenditure Survey of 2010 (U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau

of Labor Statistics, 2012), reveals that the average consumer residing in an

urban area in the United States spends 12.7% of their income on food, 34.4%

on housing, 7.6% on utilities, fuels and public services, 16% on transportation,

and 6.6% on health care. According to the same survey, the average consumer

residing in a rural area in the United States spends 14% of their income on food,

29% on housing, 9% on utilities, fuels and public services, 19% on transportation,

and 8% on health care. In both urban and rural areas, as housing costs rise,

families are paying an increasing proportion of their budget on housing, leaving

a smaller cut of their budget for food and other basic needs.

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

Kropczynski, Dyk • 131

HUD issued the report, Trends in Housing Costs: 1985-2005 and the

30-Percent-oJ-Income Standard, which uses data from the American Housing

Survey (AHS) to assess the current validity of the 30% standard (Eggers &

Moumen, 2008). The study examined the amount of consumption of non-

housing goods in 1985 and 2005, if households spent the 30% of gross income

on housing both years (Eggers & Moumen, 2008). The authors found that

regardless of income class, if households allocated 30% of their income to

housing, households would be able to consume more non-housing goods and

services in 2005 than in 1985 (Eggers & Moumen, 2008). A second measure

of validity was employed by utilizing the Bureau of Labor Statistics "family

budgets" as well as including basic needs and other general expenses in 1981,

updating the budget to 2005 dollars and comparing this with the income left

over after housing costs are paid. This alternative method found that families in

lower income brackets had substantially less money available for non-housing

essentials (Eggers & Moumen, 2008). This further emphasizes the need to

examine the relationship between housing cost and a family's ability to meet

other basic needs.

There are many costs competing for significant proportions of

household income. For example, increasing transportation costs were described

by the Brookings Institution (2007) to as 3% of the median household's annual

earnings in 2006. A number of economic studies from HUD (1996) have

addressed factors that affect the acquisition of housing as well as how the state

of the housing market influences overall affordability (Olsen, 1969; Varady &

Lipman, 1994). Few studies have explored how this standard is applied to rural

families that often face increased costs to meet these basic needs, which then

also increases their financial burden (Brookings Institution, 2007; Keen, 2008;

Medicare in rural areas, 2000; USDA, 2006)

TheoreticalApplications

One of the most prominent theoretical human need-based arguments

is Maslow's hierarchy of needs, as first proposed in a paper titled A Theory of

Human Motivation (Maslow, 1943). Although Maslow's hierarchy has become

outmoded over time and new theories have emerged, some organizations,

including UNICEF, have adapted Maslow's model to develop tools for

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

132· Housing Affordability for Rural Low-Income Families

measuring poverty. UNICEF (1995) includes housing in its seven basic

physiological needs. In the United States, determining whether or not a family

is meeting their physiological needs are identified by dollar figures such as

income or consumption, but international nonprofits are employing an Unmet

Basic Needs (UBN) approach that focuses not only on food items, but also on

subsistence items (Ngwane, Yadavalli & Steffens, 2002). "Human poverty thus

looks at more than lack of income. Since income is not the sum total of human

lives, the lack of it cannot be the sum total of human deprivation" (United

Nations Development Programme, 1998, p. 25).

In working definitions of basic needs by aid organizations, shelter is

internationally recognized as a basic need (UNICEF, 1995; United Nations

Development Programme, 1998). Although it is not directly listed in Maslow's

initial work, scholars have since built upon this original work to include shelter

as one of these basic needs (Brodsky, 1977; Hartnett, 2004; Murphy, 1978).

While humans have lived in many versions of shelter from caves to castles as

a form of basic safety, in the United States, the societal standard has been set

that if a person is not able to obtain adequate housing that provides a mailing

address and other traditional features, that person will find it very difficult to

incorporate themselves into neighborhoods and employment communities

that provide human capital. This can be considered a type of social hierarchy

wherein employers often require applicants to be able to provide certain attire

and reliable transportation in addition to an address and phone number (U.S.

Department of Housing and Urban Development, n.d.).

As housing reaches unaffordable prices, housing payments may

monopolize a family's budget and interfere with the acquisition of other basic

needs. Housing is sometimes referred to as a 'fixed cost' because a family cannot

go without housing one month and gain it back the next as easily as other items

that require payments. Families often consider food to be the most flexible

expense in their budget because more options are available, such as focusing

on lower quality food items that can be purchased in greater volumes, reducing

the number of meals, utilizing food banks or 'doing without.' As housing costs

consume larger portions of their budgets, these and other strategies are used

by low-income families searching for new methods of fulfilling needs for food,

medicine, and child care.

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

Kropczynski, Oyk • 133

Affordahle Housing and Challenges for Rural Families

Analysis of rural poverty introduces notable attributes with regard to

housing including both the circumstances that exaggerate their situation as

well as the measures taken by families to keep them afloat. Rural places have

traditionally been agricultural communities, and as the nation transitioned

to a manufacturing based economy, employment became increasingly scarce

for agricultural workers. Fortunately, many were able to maintain a degree of

subsistence living and other informal means of reducing expenses and earning

wages (McGranahan, 2003).

Presently, as modem technology reaches these communities, some

informal means of expense reduction are becoming more difficult to maintain

since modem amenities (such as updated appliances) have become an ever

increasing high-cost standard. A study by the Brookings Institution (2007) that

evaluated the high cost of poverty in the United States showed that many poor

families were digging economic holes that were simply unavoidable. When

struggling to make ends meet, many families turned to paycheck advance

facilities with higher interest rates than the credit card companies that will

not approve them as customers. Rural areas do have higher expense trends

compared to urban areas in including: Medicare costs (Medicare in rural areas,

2000), higher gas prices without the availability of public transportation (Keen,

2008), and higher energy costs (USDA, 2006).

Moreover, families in rural areas may experience difficulties locating

housing that fits their affordability range (Cook, Crull, Fletcher, Hinnant-

Bernard, & Peterson, 2002). The Housing Assistance Council (HAC, 2005)

found that gentrification and decreasing housing affordability were growing

trends in rural communities due to changing community structures. As new

commuter residents move into rural communities from expanding metropolitan

areas, property taxes rise. Employment for many non-commuters becomes

limited to low paying service jobs created by new residents, exhibiting a

structural bias toward middle-class home-owners (HAC, 2005). To contribute

to literature on the differences of affordability and community structure based

on region, this study aims to investigate low-income housing within the context

of the rural U.S. family.

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

134 • Housing Affordability for Rural Low-Income Families

Research Question

Based on the eXIstmg literature on the government standard of

affordability and a desire to expand this research to the ability for rural low-

income families to fu1£11 basic needs, this study asks: Do low-income rural

families. that are not housing cost burdened perceive themselves to be able to

meet more basic needs (such as food, clothing, medical, dental, prescription,

credit card payments, personal care and other expenses) than families that are

housing cost burdened? Furthermore, using this comparison, we hypothesize

that: The government housing affordability standard is not a reliable indicator

of families' perceived ability to meet basic needs. Testing for a relationship

between groups is done quantitatively by comparing the percentage of gross

income spent on housing with the ability to meet the needs of food, clothing,

medical care, dental care, medicines, credit card payments, and personal care

items. Q!talitative data accompanies the quantitative analysis to add depth to

the understanding of needs affordability for rural families.

Methods

This study employs secondary data analysis of rural families using

information collected by the Rural Families Speak project, specifically utilizing

the wave one data of the longitudinal multi-state project collected between

1999 and 2001 (for further detail, see http://www.csrees.usda.gov/nealfamily/

srilfamily_sri_ruralfam.html). These data were gathered in response to 1996

Welfare Reform legislation that did not take into consideration the conditions

of rural areas. The goal of the Rural Families Speak project is to track well-

being, functioning, and family circumstances of rural, low-income families with

children over time in the context of this reform. Data in this study have been

collected from 414 rural families residing in: California, Indiana, Kentucky,

Louisiana, Massachusetts, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, New

Hampshire, New York, Ohio, Oregon and West Virginia. Twenty-seven rural

counties within these states are included: rurality in this study was determined

using the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) urban influence code of

this areal. The study consists of mothers aged 18 and older with at least one

child 12 years old or younger recruited by fliers and community agencies and

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

Kropczynski, Dyk • 135

then screened for eligibility by phone or in-person screening interviews. To

be considered low-income, participants were currendy eligible for, or receiving

Food Stamps, or Women Infants and Children (WIC) Program transfers at

the time of the first interview screening (Bauer, 2005). It is currendy one of the

widest-reaching datasets of rural families in the United States of its kind.

Data were collected through three in-person interviews using a mixed

qualitative and quantitative protocol to identify common forces affecting

people in various rural communities. Mothers were surveyed about the status

of their household through an in-depth series of questions about their daily

lives and the lives of their families. Mothers were determined to be most useful

to answering questions based on the daily lives of multiple family members and

therefore, for the purposes oflarge data gathering, only mothers were considered

eligible participants. The resulting dataset contains information about many .

aspects of family life including monthly housing costs and monthly income.

For this analysis, these variables were isolated to produce the ratio of gross

income spent on housing. All data were collected consistendy with a common

protocol. After data collection, this study divided the data based on housing

cost burden status. As with many long interviews through several waves of data,

participants were given the option to pass on any particular question. Because

answers were not always provided, the total N for some variables were uneven

in this analysis. Families with insufficient information to calculate the ratio

of gross income spent on housing were excluded; the remaining sub-sample

consisted of 263 families. The sub-sample was similar in demographics to the

original sample.

The research question was analyzed through an ordered logistic

regression, frequency tables of perceived needs met, and further characterized

through statements in qualitative interviews. Table 1 shows the demographics

of the mothers in the sample used in the analysis.

The percent of income spent on housing was calculated by taking the

family's housing costs and dividing by their total income. If the percent of

total income spent on housing was equal to or less than 30%, the family was

considered not housing cost burdened. If the percent of total income spent

on housing was greater than 30%, the family was considered to be housing

cost burdened. Although housing assistance is designed to alleviate cost burden

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

136· Housing Affordability for Rural Low-Income Families

status, participants were on various assistance programs and 33% of the cost

burdened families in the sample identified themselves as receiving housing

assistance at the time of their interview (see Table 2).

Table 1. Sub-Sample Demographics of Mothers (N = 263)

Range Mean Percent

Age (years) 18 to 57 29

Number of children 1 to 10 2.3

Annual gross household income 115,522

Monthly housing costs .254

Housing cost burdened 40%

Received housing assistance 21%

White! Non-Hispanic 65%

Hispanic 22%

African American 9%

Native American 1%

Asian 0%

Table 2. Crosswise Comparison of Presence of Housing Assistance

with Cost Burdened Status

Not cost burdened Cost burdened Total

No housing assistance 149 (76%) 45(67%) 194

Received housing assistance 47 (24%) 22 (33%) 69

Total 86 (100%) 67 (100%) 263

The perceived ability to make ends meet was evaluated through by

following survey question:

In the past year, has there been a time when you had a hard time mailing

ends meet or payingfor necessities' What did you have trouble paying/or'

Food' Clothing' Healtheare' Credit payments' Personal care or non-jood

items'

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

Kropczynski, Dyk • 137

The ratio of gross income spent on housing was compared to the yes/no

responses of families' ability to pay for necessities (food, clothing, medical

care, dental care, medicines, credit payments, personal care items and other).

The housing cost variable included utility costs and actual dollar amounts

paid for housing (after any subsidies or assistance has been applied). Total

income included the following: self and partner wages, tips, commissions and

overtime, Social Security Disability, social security retirement! pensions, SSI

(Supplemental Security Income), TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy

Families), unemployment compensation, worker's disability compensation,

Veteran's benefits, child or spousal support, foster child assistance, children's

wages, food stamps, regular gifts from family/friends, educational loans/grants

and other miscellaneous income.

The percent of gross income spent on housing allowed us to categorize

each participant. On average, there was no significant difference in the ability

to meet basic needs between families that were cost burdened and families

that were not cost burdened based on a t-test. The ratio itself was compared to

each of the perceived needs met through an ordered logistic regression. In an

effort to obtain further descriptive information about these rural low-income

families, statements about their individual situations were highlighted from the

qualitative portion of the interviews and the descriptive statistics were used to

further differentiate individual need variables. Aggregates of all need variables

were used to compare the total number of perceived needs met to the cost

burdened status as well to help identify ranges of needs met. The cost burdened

status took into account whether families received housing assistance; further

examination of the ability to meet needs was done by not only categorizing

families by cost burdened status, but also whether or not the family received

housing assistance.

Results

In-depth interviews provided both qualitative and quantitative

information. Mothers gave accounts of their families' struggles to meet basic

needs. Even with various forms of financial assistance, many cost burdened

families were still not able to meet basic needs. These cost burdened families

did not report high standards of economic success; most stated relatively simple

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

138· Housing Affordability for Rural Low-Income Families

definitions of the term necessities: "My kids' clothes, our food ifwe need extra food,

and shampoos, and things like that." When interviewed, these cost burdened

families did not describe eillborate or frivolous spending habits. This indicates

that their perception of needs was not one of excess, but a desire to purchase basic

items. When asked "If you got 20 dollars tomorrow, what would you do with it?"

one mother responded, "Buy something I needed. Like soap or something."

A comparison of the group of cost burdened households to the group

of not cost burdened households is shown in Table 3. The cost burdened group

had larger monthly housing costs and lower monthly incomes than those of

the group not cost burdened. This is what directly contributed to the greatly

differing averages of gross income spent on housing. For this analysis, it is

important to start with the understanding that these two groups are different

in their income and housing costs.

Table 3. Weighted Means of the Continuous Variables

Cost burden status

Not cost burdened Cost burdened

Variables (n =63) (n =200)

Monthly housing cost (in dollars) 215.22 436.35

(13.914) (22.566)

Monthly household income (in dollars) 1495.92 959.74

(58.155) (67.303)

Percent of income spent on housing 0.137 0.556

(0.006) (0.470)

Note: Numbers in parentheses are standard errors of the means

The ratio of income spent on housing, is a continuous variable, but it

can also be examined as a dichotomous variable (as shown in Tables 4 and 5),

wherein ratios greater than or equal to 30% are categorized as cost burdened and

ratios less than 30% are categorized as not cost burdened. A regression analysis

was used to examine this ratio ofincome as a continuous dependent variable. The

results showed no relationship between the ratio ofincome spent on housing and

the ability to meet overall basic needs. There was also no relationship between

ratio ofincome spent on housing and any other demographic variables. Previous

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

Kropczynski, Dyk • 139

research indicated that from a policy standpoint, "it is important to understand

which households cannot pay for non-housing needs after they pay for housing

because they are likely to be in a more precarious position than those that have

high cost burdens but can still pay for minimal non-housing consumption"

(Kutty, 2005, p. 116). Further examination of the ability of these families to

meet needs was done by comparing the same perceived needs with whether the

family received housing assistance (Table 4). Again, there was little disparity

between the families that received housing assistance and those that did not.

This suggests that assistance given to families with the intention of making

housing affordable and increasing the ability to meet needs did not necessarily

lead to a difference in the perceived ability to meet needs. The absence of any

significant variance between the two groups' perceptions of met needs calls into

question the effectiveness of the level of assistance these families were given,

since recipients perceived themselves to be no better off in terms of basic needs

than non-recipients. This analysis suggests that the many organizations using

some variation of the government standard of affordability when calculating

housing assistance allowances may need to reconsider this equation if wishing

to have a greater impact on rural recipients' overall economic well-being.

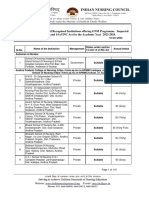

Table 4. Count of Perceived Needs Met by Cost Burdened Status and

Housing Assistance

Not-cost No housing Received housing

burdened Cost burdened assistance assistance

(n 151)

D (n =104) (n ~ 205) (n . 50)

Needs met n % n % N % n %

0 33 21 17 16 47 30 3 6

1 29 19 14 13 30 14 13 26

2 24 16 14 13 28 13 10 20

3 13 8 25 24 29 14 9 18

4 18 12 11 10 23 11 6 12

5 13 8 11 10 18 9 6 12

6 11 7 8 7 18 9 1 2

7 5 3 1 1 5 2 1 2

8 5 3 3 3 7 3 1 2

Mean number

of needs met 2.3 3.4 4.1 2.9

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

140· Housing Affordability for Rural Low-Income Families

Yet another way that families were similar was in not only the number

of needs met, but in the perceived ability to meet each individual need (Table

5). The largest discrepancy between the two groups was in their ability to meet

medical care needs, which was a difference of 7%, with cost burdened families

perceiving an improved ability to meet this need. This discrepancy may be due

to increased eligibility for medical assistance for low-income families; another

explanation is that this was a need that cost burdened families leveraged as a

payment priority among other needs. The second largest discrepancy between

these two groups was the non-cost burdened families' perceived ability to meet

clothing needs; it was five percentage points higher than their cost burdened

counterparts. Clothing needs were perceived to be met more than any of the

other needs discussed, as many families were able to utilize second-hand clothes

from child to child or find clothing donation centers in their area. Still, only

55% of non-cost burdened families and 50% of cost burdened families perceived

themselves to be able to meet this need, indicating that, overall, these low-

income rural families perceived themselves capable of meeting very few needs.

Table 5. Categories of Perceived Needs Met by Cost Burdened Status

and Housing Assistance

Needs perceived to be met (percentage)

Medical Dental Credit Personal

Food Clothing care care Medicine card care Other

Non-cost

burdened 43% 55% 26% 25% 33% 35% 30% 37%

Cost

burdened 41% 50% 33% 25% 31% 36% 34% 37%

No housing

assistance 42% 45% 31% 28% 33% 31% 30% 32%

Received housing

assistance 35% 48% 22% 22% 29% 38% 33% 41%

When comparing each of the individual needs once more but separating

families by receivership of housing assistance, more variation occurred among

families than in any of the above comparisons (Table 5). Interestingly, the

perceived ability to meet the needs of food, medical care, dental care and

medicines were all higher among families not receiving housing assistance.

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

Kropczynski, Dyk • 141

Clothing, credit card payments, personal care and other needs were perceived

to be met more often by families receiving housing assistance. These differences

could be, in part, due to the nature of the need categories. Food and medical

needs are generally items of higher priority than those of clothing {which,

as discussed, may be slighdy more accessible}, credit card, personal care and

other needs, which may sometimes be overlooked in times of severe difficulty.

This particular sample did not corroborate Kutty's {2006} claim that housing-

induced poverty (which is based on the ability to afford a basket of non-housing

goods) is less likely if receiving housing assistance.

When looking at the cost burdened status in comparison to the number

of aggregated perceived needs met that were described in Table 4, the majority of

all families, both cost burdened {n = 104} and non-cost burdened {n =151}, met

between zero and four of the basic needs in question. Very few families met all

eight of the needs. There was litde difference between the two groups in terms of

their ability to meet basic needs based on cost burden status. In a t-test, families

that were not housing cost burdened did not meet significandy more needs

{M = 2.88, SD = 4.71} than those families that were housing cost burdened

{M = 2.56, SD = 3.77}, 1(95} = 1.07, P = .285. This indicates that these

particular low-income families living in rural areas felt no less 'burdened'despite

their technically non-cost burdened status. For these families, the government

standard does lime to measure true affordability. Further, an ordered logistic

regression did not indicate any statistically significant correlations between cost

burdened status and the ability to meet basic needs. One might expect families

with relatively higher income and lower monthly housing costs {as indicated

in Table 3} to have a statistically significant ability to meet more needs than

their counterparts with higher housing costs and lower incomes, however, an

ordered logistic regression and I-test showed no relationship between the

variables. Counts with simple percentages were found to be the best way to

further describe nuances to these variables.

Conclusions

The families in this study that were not housing cost burdened were

not more likely to perceive the ability to meet more needs than the families

that were housing cost burdened; thus, our hypothesis is in line with the results.

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

142 • Housing Affordability for Rural Low-Income Families

This study supports the concept that the government standard of housing

affordability is inadequate and that the definition of affordability needs to be

reconstructed to include the ability to meet the basic needs of families. This

is consistent with the findings published in the aforementioned HUD study

(Eggers & Moumen, 2008), stating that after spending 30% of income on

housing, the remaining 70% of these families' income does not appear to be

enough to meet basic needs. However, when comparing income alone to the

cost of needs in this study, some families would not be able to meet basic needs

even if they had no housing costs at all. It should also be noted that, even if70%

of their income was sufficient to meet other basic needs, 30% of a low-income

budget is sometimes still not enough to cover housing costs and in most cases .

would not be likely to secure safe, habitable housing. In a similar study, Mimura

(2008) found that poverty status may be a better explanation of economic

hardships than housing cost burden, which supports the idea of income-range

based policies rather than percent of income. As Maslow suggests, because

these families are not able to meet the basic need of housing, the families are

not able to move up the hierarchy to meet other needs that they expressed

interest in achieving such as stable employment, owning their own home, or

completing their education.

A number of alternative measures have been proposed (e.g., Combs,

Combs, & Ziebarth, 1995; Jewkes & Delgadillo, 2010; Kutty, 2005; Stone,

1993; Stone 2006), however, reforms to make the standard more precise and

based on explicit norms of affordability have never gained momentum. The

rule of thumb arose out of a series of transitions prompted by controversy

surrounding the amount families would pay for rent in federally assisted

housing rather than current research-based methods of household finances

(Mimura, 2008). The scientific basis for the current affordability standards

are empirical studies from family budgets from the late 19th and early 20th

centuries. There have been obvious household changes to family budgets since

the percent of income standard was set. In their much-cited article, Linneman

and Megbolugbe (1992) point to transitions through the years that have driven

up the cost of housing. A doubling of median family incomes in the 1950s and

1960s drove up the quality of U.S. homes, followed by availability of consumer

credit and changing tastes for housing amenities (Linneman & Megbolugbe,

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

Kropczynski, Oyk • 143

1992). Prices of utilities have also increased dramatically over the last century

and as these costs have increased, home builders have placed emphasis on

building materials to increase energy efficiency at increased housing costs.

To ground this standard in scientific research, competing percentages

of household spending will need to be taken into consideration on a regular

basis which would force the standard to be in constant flux. Another problem

in measurements is the growing availability of consumer and housing related

credit, particularly to lower income consumers and the subsequent growing

debt levels among U.S. households. Linneman and Megbolugbe (1992) were

ahead of their time when they pointed to an affordability paradox wherein "the

prospect of future price appreciation increases the investment attractiveness of

purchasing a home even as it reduces affordability" (p. 374). Other countries

have adapted measurements to include basic needs, for example the Australian

Government's National Housing Strategy defines affordability as "the notion

of reasonable housing costs in relation to income; that is, housing costs that

leave households with sufficient income to meet other basic needs such as food,

clothing, transport, medical care and education" (Berry & Hall, 2001, p. 50).

Housing need is commonly treated as having three components of

which housing affordability is only one (O'Dell, Smith, & White, 2004). Only

housing affordability was truly addressed in this analysis, however, this is not to

minimize the importance of the other two housing needs: housing condition

and overcrowding. The American Housing Survey gives some consideration to

a housing quality index; however, it does not cover all areas and is more useful

to large metropolitan areas. Future studies should consider datasets that contain

information on the breadth of housing needs for a more robust analysis of the

special conditions of rural areas which typically have a different housing makeup

from their urban counterparts. Many rural areas do not have the economic

development structure to continue producing new homes or rental homes. This

lack of new development causes many homes to go into disrepair. With these

structurally different types of housing problems, many low-income families in

rural areas are not seeking the same types of government-assisted housing.

Currently, similar debates are being held regarding other forms of

assistance, with politicians discussing policies that will designate affordability

of various needs as a percentage of income. In order for these debates to be truly

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

144· Housing Affordability for Rural Low-Income Families

comprehensive, policy makers must critically assess to which populations these

percent-of-income policies are meaningful before continuing in this direction.

Low-income housing advocates look for actual dollar amounts, rather than

a ratio, to associate with housing, arguing that "[t]he insistence upon setting

rent as a percentage of income is a curious, brilliant illumination of what one

might call Congress' middle-class bias. Rent-income ratios are meaningful for

the middle-class but not for the poor, who often cannot afford to spend any

portion of their income on rent" (Roisman, 1971, p. 692). As this study shows,

current percent-of-income housing standards do not appear to be adequate

measures of affordability for these rural low-income families, indicating that

similar basic need standards may be equally insufficient for such families.

The government standard of affordability is an example of the

intrinsic interest in cross-national and urban scales that much of the literature

on inequality has been situated (Lobao, Hooks, & Tickamyer, 2007). These

authors note that while demography and rural sociology traditionally consider

the context of space, most other disciplines are lacking the appropriate

background to frame such questions. They are concerned that inequalities of

space and place have been left in a different field than studies of inequalities.

This is an important point to make not only to researchers in these fields but

to the policy makers and national organizations that serve rural communities.

With a focus on public sociology, some grantors have incorporated the need

to translate research into more public forms such as policy briefs or pamphlets

that can be distributed to community organizations. It is understandable that

as Lobao et al. (2007) has pointed out, there is litde adequate research being

produced in this area, therefore it becomes increasingly important to increase

the accessibility of this information.

Ultimately, the ways that rural low-income families make ends meet

may be significandy different than those incorporated into a ratio of income

spent on housing. When looking at percentages alone, there is a counter-

intuitive relationship between the ability to meet needs and housing cost

burden status. This is an indication that rural communities do not statistically

fit the same equations of affordability that are used to govern federal funding.

Further research is recommended in this area to prescribe policies specifically

targeting rural poverty. A limitation of this study was depending on a dataset

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

Kropczynski, Oyk • 145

that did not exclusively target the topic of housing or perceived needs met.

Primary data from survey, in-depth interview, or focus group questions specific

to the hypothesis that cost burden status does not aid in the perceived ability to

meet needs may help explain these results in future studies.

Another limitation of this study is the subjective determination of the

ability to meet needs. A study with less subjectivity might use an estimated dollar

amount necessary to meet each of these needs per family member in order to

determine if the ability to meet these needs is allowable by the household budget.

Alternately, it might include observation offamilies' consumption of needs to gain

understand of contributions by welfare, nonprofit organizations, and information

networks in addition to direct spending ofincome on meeting basic needs. These

study designs would still be limited by the subjectivity of the researcher, but

would allow for some measurement consistency across cases. These studies

might be amiss to disregard the perception of the participant themselves and

their ability to meet basic needs. While this study is limited by the participants'

perceptions, there is also a great deal to learn from these perceptions.

Endnotes

1 Urban Influence Codes are a 12-part county classification scheme that

distinguishes metropolitan counties by size and nonmetropolitan counties by

proximity to metro and micro areas. More information can be found on the U.S.

Department of Agriculture Website: http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-productsl

urban-inHuence-codes.aspx

References

Bauer, ]. W. (2005). Rural families speak: Project description. St. Paul, MN:

University of Minnesota. Retrieved November 2007 from http://fsos.

cehd.umn.edulprojects/rfslprojectdescr.html

Becker,]., Stolberg, S. G., & Labaton, S. (2008, December 21). The reckoning:

White House philosophy stoked mortgage bonfire. '!he New York Times.

Retrieved on October 24, 2010, from http://www.nytimes.

coml2008/12/21Ibusiness/21admin.html?_r=2&pagewanted=all

Berry, M., & Hall,]. (2001). Policy optionsfor stimulatingprivate sector investment

in affordable housing across Australia: Stage 1 report, outlining the needfor

action. Sydney: Affordable Housing National Research Consortium.

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

146 • Housing Affordability for Rural Low-Income Families

Retrieved from www.consortium.asn.au

Brodsky, S. L. (1977). Go away, I'm looking for the truth: Research utilization

. in corrections. Criminaljustice and Behavior, 4(1),3-10.

Brookings Institution. (2007).1he highprice ofbeingpoorin Kentucky. Washington,

DC: Author. Retrieved July 2007 from http://www.kyyouth.org/

PublicationslHighPriceKY. pdf

Combs, E. R., Combs, B. A., & Ziebarth, A. C. (1995). Housing affordability:

A comparison of measures. Consumer Interests Annual, 41, 188-194.

Cook, C. C., Crull, S. R., Fletcher, C. N., Hinnant-Bernard, T., & Peterson J.

(2002). Meeting family housing needs: Experiences in the midst of

welfare reform. Journal ofFamily and Economic Issues, 23(3),285-316.

Eggers, F. J., & Moumen, F. (2008). Trends in housing costs: 1985-2005 and the

30-percent-oJ-income standard. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and

Research. Retrieved from http://www.huduser.org/publications/pdfl

Trends_hs~costs_85-2005.pdf

Feins, J. D., & Lane, T. S. (1981). How much for housing? Cambridge: Abt

Books.

Hartnett, M. T. (2004). Health coping strategies in homeless women at an

interfaith ministry of hospitality. Dissertation Abstracts International,

65(3-B),1247.

Hulchanski,}. D. (1995).1he concept of housing affordability: Six contemporary

uses of the housing expenditure-to-income ratio. Housing Studies, 10(4),

471-491.

Housing Assistance Council (HAC). (2005). 1heypavedparadise... Gentrification

in rural communities. Washington, DC: Author.

Jewkes, M. D., & Delgadillo, L. M. (2010). Weaknesses of housing affordability

indices used by practitioners. Journal of Financial Counseling and

Planning, 21(1),43-52.

Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University (JCHS). (2005). 1he

state ofthe nation~ housing 2005. Retrieved April 2008 fromhttp://www.

jchs.harvard.edu/publications/markets/son2005/son2005_housing_

challenges.pdf

Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University (JCHS). (2012). 1he

state ofthe nation~ housing 2012. Retrieved September 2012 from http://

www.jchs.harvard.edulsites/jchs.harvard.edulfileslson2012_bw.pdf

Keen, J. (2008, July 2). High gas prices threaten to shut down rural towns.

USA Today.

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

Kropczynski, Dyk • 147

Kutty, N. (2005). A new measure of housing affordability: Estimates and

analytical results. Housing Policy Debate, 16( 1), 113-142.

Linneman, P. D., & Megbolugbe, 1. F. (1992). Housing affordability: Myth or

reality? Urban Studies, 29(3/4),369-392.

Lobao, L. M., Hooks, G., & Tickamyer, A. R. (2007). 1he sociology of spatial

inequality. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50,

370-396.

McGranahan, D. A. (2003). How people make a living in rural America.

In D. Brown & L. Swanson (Eds.), Challenges for Rural America

in the Twenty-First Century (pp.135-165). University Park, PA: Penn

State Press.

Medicare in rural areas: Hearings before the House Committee on Small

Business, 106th Congo (2000, June 14) (testimony of Kathy Buto, U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services) .. Retrieved March 2009

from http://www.hhs.gov/asVtestify/tO00614c.html

Mimura, Y. (2008). Housing cost burden, poverty status, and economic hardship

among low-income families. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 29,

152-165.

Murphy, H. B. (1978).1he meaning of symptom-cheek-list scores in mental

health surveys: A testing of multiple hypotheses. Social Science &

Medicine, 12(2-A), 67-75.

National Low Income Housing Coalition. (2006). Out ofReach 2006. Retrieved

August 2007 from http://www.nlihc.org/oor/oor2006/?CFID=216157

62&CFTOKEN=77369492

Ngwane, A. K., Yadavalli, V. S. S., & Steffens, F. E. (2002). Poverty:

Deprivations in terms of basic needs. Development Southern Africa,

19(4),545-560.

O'Dell, W., Smith, M. T., & White, D. (2004). Weaknesses in current measures

of housing needs. Housing and Society, 31(1), 29-40.

Olsen, E. O. (1969). A competitive theory of the housing market.1heAmerican

Economic Review, 59(4),612-622.

Pelletiere, D. (2008). Getting to the heart of housing's fundamental question: How

much can a family afford? Washington, DC: National Low Income

Housing Coalition. Retrieved September 2012 from http://nlihc.org/

library/otherlperiodidhousing-fundamental..,question.

Roisman, F. W. (1971).1he right to public housing. 1he George Washington Law

Review, 39, 691-733.

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

148· Housing Affordability for Rural Low-Income Families

Schwartz, M., &Wilson, E. (2006). Who can ajford to live in a home? A look at

data from the 2006 American Community Survey. U.S. Census Bureau.

Retrieved January 2012 from https://www.census.govlhheslwww/

housing/special-topicslfiles/who-can-afford.pdf

Stigler, G.]. (1954). The early history of empirical studies of consumer behavior.

'!he Journal ofPolitical Economy, 62(2),95-113.

Stone, M. E. (1993). Shelter poverty: New ideas on housing ajfordalJility.

Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Stone, M. E. (2006). What is housing affordability? The case for the residual

income approach. Housing Policy Debate, 17(1), 151-183.

Torluccio, G., & Dorakh, A. (2011). Housing affordability and methodological

principles: An application. International ResearchJournal ofFinance and

Economics, 79,64-78.

UNICEF. (1995). '!he state ofthe world~ children. New York: Oxford University

Press Oxford.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (1998). Human

development report. New York: Oxford University Press.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). (2006) Agriculture and rural

communities are resilient to high energy costs. Retrieved March 2009 from

http://www.ers.usda.gov/AmberWavesiApril06lFeatures/Energy.htm

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Office of Policy

Development and Research. (1996, August). U.S. housing market

conditions. Washington, DC: Author.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Office of Policy

Development and Research. (n.d.). Solutions at work: Understanding

homelessness. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved February 2009 from

http://www.huduser.org/periodicalslfieldworks/1202/fworks4.html

U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2012). Consumer

expenditures in 2010: Lingering tjfects of the great recession. Retrieved

September 2012 from http://www.bls.gov/cexlcsxannlO.pdf

Vandenbroucke, D. A. (2007). Housing affordahility data system. Washington,

DC: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of

Policy Development and Research. Retrieved August 20, 2008, from

http://www.huduser.orglDatasetslhadslHADS_doc.pdf

Varady,D.P.,&Lipman,B.J. (1994). What are renters really like? Results from

a national survey, Housing Policy Debate, 5(4),491-531.

HOUSING AND SOCIETY, 39(2), 2012

You might also like

- 9 Tactics of Lifelong GeniusDocument4 pages9 Tactics of Lifelong GeniusApurv MehtaNo ratings yet

- Housing Policy in The USDocument37 pagesHousing Policy in The USAesha Upadhyay0% (1)

- Daemon Prince Character Sheet: P D D DDocument2 pagesDaemon Prince Character Sheet: P D D Dshamshir7307858No ratings yet

- Hekhalot Literature in EnglishDocument34 pagesHekhalot Literature in EnglishAíla Pinheiro de Andrade0% (1)

- Exploring Tiny Homes As An Affordable Housing StraDocument22 pagesExploring Tiny Homes As An Affordable Housing StraKalyani sonekarNo ratings yet

- How Affordable Is HUD Affordable Housing - Reportv4Document52 pagesHow Affordable Is HUD Affordable Housing - Reportv4BrandonFormbyNo ratings yet

- SAnet CD 9811017409 PDFDocument357 pagesSAnet CD 9811017409 PDFoeamaoesahaNo ratings yet

- Osamu Dazai: Genius, But No Saint - The Japan TimesDocument3 pagesOsamu Dazai: Genius, But No Saint - The Japan TimesBenito TenebrosusNo ratings yet

- Taking Stock of Housing in Your CommunityDocument24 pagesTaking Stock of Housing in Your CommunityHousing Assistance CouncilNo ratings yet

- University of Calgary School of Public Policy - Affordability of Housing Kneebone WilkinsDocument19 pagesUniversity of Calgary School of Public Policy - Affordability of Housing Kneebone WilkinsRBeaudryCCLENo ratings yet

- Literature Review Affordable HousingDocument7 pagesLiterature Review Affordable Housinge9xy1xsv100% (1)

- The_Affordable_Housing_Stress_among_MiddDocument9 pagesThe_Affordable_Housing_Stress_among_Midd2021005036No ratings yet

- Housing AffordabilityDocument8 pagesHousing AffordabilityBoss VasNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Public HousingDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Public Housingfvjebmpk100% (1)

- Through The Roof Full: What Communities Can Do About The High Cost of Rental Housing in AmericaDocument56 pagesThrough The Roof Full: What Communities Can Do About The High Cost of Rental Housing in AmericaDoubleDayNo ratings yet

- Housing Investment SpilloversDocument46 pagesHousing Investment Spilloversmlks2011No ratings yet

- A Study On Public Housing and Housing Voucher Program in The USDocument14 pagesA Study On Public Housing and Housing Voucher Program in The USNurul Syttadilla EdamiNo ratings yet

- Housing and "Nance in Developing Countries: Invisible Issues On Research and Policy AgendasDocument25 pagesHousing and "Nance in Developing Countries: Invisible Issues On Research and Policy AgendasMai A. SultanNo ratings yet

- Hoover Institution 2018 Summer Policy Boot Camp Director's AwardDocument28 pagesHoover Institution 2018 Summer Policy Boot Camp Director's AwardHoover InstitutionNo ratings yet

- Housing Inequality Causes and SolutionsDocument5 pagesHousing Inequality Causes and SolutionsFredrickNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Residents' View On Affordability of Public Housing in Awka and Onitsha, NigeriaDocument19 pagesEvaluation of Residents' View On Affordability of Public Housing in Awka and Onitsha, NigeriaAnysonNo ratings yet

- Report of The 2008 Housing First Task ForceDocument36 pagesReport of The 2008 Housing First Task Forcewebmaster@drugpolicy.orgNo ratings yet

- Origins and Evolution of the Housing Expenditure-to-Income RatioDocument71 pagesOrigins and Evolution of the Housing Expenditure-to-Income RatioJann Penny II ClavecillaNo ratings yet

- The Cardinal DirectionDocument72 pagesThe Cardinal DirectionmiriamsrosenauNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Demand and Supply Factors On The Affordability of HDocument8 pagesThe Effect of Demand and Supply Factors On The Affordability of HMekonnen TamiratNo ratings yet

- 08 Comparing Local Instead of National Housing RegimesDocument12 pages08 Comparing Local Instead of National Housing RegimesAthirahNo ratings yet

- HPD 0604 WallaceDocument30 pagesHPD 0604 Wallacelitzyouk8381No ratings yet

- Rental Housing: An International Comparison: Working Paper, September 2016Document52 pagesRental Housing: An International Comparison: Working Paper, September 2016Rainfine IrrigationNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Housing Supply in Sekondi-TakoradiDocument81 pagesFactors Affecting Housing Supply in Sekondi-TakoradiGamor Wonie SharonNo ratings yet

- Housing Policy at a Crossroads: The Why, How, and Who of Assistance ProgramsFrom EverandHousing Policy at a Crossroads: The Why, How, and Who of Assistance ProgramsNo ratings yet

- Anthony Downs - Growth Management and Affordable Housing - Do They Conflict - (James A. Johnson Metro) (2004)Document304 pagesAnthony Downs - Growth Management and Affordable Housing - Do They Conflict - (James A. Johnson Metro) (2004)ManuelEfYiNo ratings yet

- Effects From LivingDocument37 pagesEffects From LivingAndiSumarniNo ratings yet

- HomelessnessDocument6 pagesHomelessnessgreatwriters001No ratings yet

- Overview of The Housing Affordability ProblemDocument7 pagesOverview of The Housing Affordability ProblemreasonorgNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Affordable Housing in IndiaDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Affordable Housing in Indiaxfdacdbkf100% (1)

- Housing First But Not Only, and Certainly Not ForeverDocument10 pagesHousing First But Not Only, and Certainly Not ForeverHoover InstitutionNo ratings yet

- Hop Wane Ed PaperDocument2 pagesHop Wane Ed PaperhousingworksNo ratings yet

- Monetary Policy, Housing Rents, and Inflation Dynamics: International Finance Discussion PapersDocument26 pagesMonetary Policy, Housing Rents, and Inflation Dynamics: International Finance Discussion PapersChandan SinghNo ratings yet

- Housing Finance PDFDocument5 pagesHousing Finance PDFAlisha SharmaNo ratings yet

- Homeward DC Report FY 2021 2025Document61 pagesHomeward DC Report FY 2021 2025MariaNo ratings yet

- Affordable Housing 2019Document25 pagesAffordable Housing 2019The Livingston County NewsNo ratings yet

- Low Income ThesisDocument4 pagesLow Income ThesisJames Heller100% (2)

- The Effects of Housing Cost Burden and Housing TenureDocument10 pagesThe Effects of Housing Cost Burden and Housing Tenurebülent öngörenNo ratings yet

- Affordable Housing in Urban Areas: The Need, Measures and InterventionsDocument17 pagesAffordable Housing in Urban Areas: The Need, Measures and Interventionspallavi kapoorNo ratings yet

- Urban Planning and Homelessness ArticleDocument23 pagesUrban Planning and Homelessness Articleapi-235378519No ratings yet

- Rent Imputation For Welfare MeasurementDocument18 pagesRent Imputation For Welfare MeasurementCorne05No ratings yet

- Making The Case For Affordable HousingDocument15 pagesMaking The Case For Affordable Housinglitzyouk8381No ratings yet

- Artistic and Gay Populations Increase Housing ValuesDocument34 pagesArtistic and Gay Populations Increase Housing ValuesDragana KosticaNo ratings yet

- wp19 30Document57 pageswp19 30José AntonioNo ratings yet

- The Housing LifelineDocument23 pagesThe Housing LifelineCore Research100% (1)

- Unit-1/ Introduction To Housing and Housing Issues - Indian Context /10 HoursDocument32 pagesUnit-1/ Introduction To Housing and Housing Issues - Indian Context /10 HoursPriyankaNo ratings yet

- Importance of HousingDocument3 pagesImportance of HousingpriscamthobwaNo ratings yet

- 3 - 3 - Pritika Hingorani - Paper - T3 (Revised) PDFDocument29 pages3 - 3 - Pritika Hingorani - Paper - T3 (Revised) PDFnithyaNo ratings yet

- Housing Affordability Literature Review and Affordable Housing Program AuditDocument7 pagesHousing Affordability Literature Review and Affordable Housing Program Auditc5p0cd99No ratings yet

- Moving To Opportunity: An Experiment in Social and Geographic MobilityDocument12 pagesMoving To Opportunity: An Experiment in Social and Geographic MobilityfadligmailNo ratings yet

- 16 Ok Ok Kumar & Bauer - Lean Thinking and Six Sigma in Public Housing Autorities - 2010Document18 pages16 Ok Ok Kumar & Bauer - Lean Thinking and Six Sigma in Public Housing Autorities - 2010Oscar Ivan Londoño GalvizNo ratings yet

- Consumption - and Productivity-Adjusted Dependency Ratio With Household Structure Heterogeneity in ChinaDocument36 pagesConsumption - and Productivity-Adjusted Dependency Ratio With Household Structure Heterogeneity in ChinaMuhammad Usama AslamNo ratings yet

- Revisiting Low Income Housing-A Review of Policies and Perspectives-Pritika HDocument35 pagesRevisiting Low Income Housing-A Review of Policies and Perspectives-Pritika HIshitaKapoorNo ratings yet

- Housing Finance: Understanding Homes, Loans, and AffordabilityDocument54 pagesHousing Finance: Understanding Homes, Loans, and AffordabilitySuresh KoppuNo ratings yet

- Sample Literature Review On HomelessnessDocument4 pagesSample Literature Review On Homelessnessnynodok1pup3100% (1)

- Research Papers On Affordable HousingDocument8 pagesResearch Papers On Affordable Housingsuz1sezibys2100% (1)

- Measuring Housing Affordability for Seniors in Hong KongDocument19 pagesMeasuring Housing Affordability for Seniors in Hong KongMohit PatilNo ratings yet

- Arcilla 2019 AffordabilityofSocializedHousinginthePhilippinesPolicyBriefDocument13 pagesArcilla 2019 AffordabilityofSocializedHousinginthePhilippinesPolicyBriefRobert PaanoNo ratings yet

- Nrpa Agency Performance ReviewDocument32 pagesNrpa Agency Performance ReviewDeodorant de araujo jeronimoNo ratings yet

- Survey DesignDocument44 pagesSurvey DesignDeodorant de araujo jeronimoNo ratings yet

- FKD 5 (40) 2021 Na Druk-178-183Document6 pagesFKD 5 (40) 2021 Na Druk-178-183Deodorant de araujo jeronimoNo ratings yet

- TR - IF - Week 11-14Document38 pagesTR - IF - Week 11-14Deodorant de araujo jeronimoNo ratings yet

- Thesis Draft Chapters 1 To 3Document61 pagesThesis Draft Chapters 1 To 3Deodorant de araujo jeronimoNo ratings yet

- An Analysis The Economic Benefits of ImplementingDocument11 pagesAn Analysis The Economic Benefits of ImplementingDeodorant de araujo jeronimoNo ratings yet

- II-3-Article1 Cipriani BallabeniDocument10 pagesII-3-Article1 Cipriani BallabeniDeodorant de araujo jeronimoNo ratings yet

- Sida34551en Urban Development PlanningDocument2 pagesSida34551en Urban Development PlanningDeodorant de araujo jeronimoNo ratings yet

- Li Umd 0117E 17685Document162 pagesLi Umd 0117E 17685Deodorant de araujo jeronimoNo ratings yet

- Carbohydrates ReviewerDocument2 pagesCarbohydrates ReviewerJazer AvellanozaNo ratings yet

- VOCABULARY 5 TOWNS AND BUILDINGS Part BDocument4 pagesVOCABULARY 5 TOWNS AND BUILDINGS Part BELENANo ratings yet

- Soymilk MenDocument7 pagesSoymilk Mentonious95No ratings yet

- Post Graduate Medical (Government Quota) Course Session:2021 - 2022 List of Candidates Allotted On - 04.03.2022 (Round 2)Document104 pagesPost Graduate Medical (Government Quota) Course Session:2021 - 2022 List of Candidates Allotted On - 04.03.2022 (Round 2)Aravind RaviNo ratings yet

- Scheme Samsung NT p29Document71 pagesScheme Samsung NT p29Ricardo Avidano100% (1)

- WBCSC Information Sheet For Interview Advt - 1 - 2015 - UpdatedDocument1 pageWBCSC Information Sheet For Interview Advt - 1 - 2015 - UpdatedArindam GhoshNo ratings yet

- Wps PrenhallDocument1 pageWps PrenhallsjchobheNo ratings yet

- Shadow On The Mountain Reading GuideDocument2 pagesShadow On The Mountain Reading GuideAbrams BooksNo ratings yet

- Maintenance and Service GuideDocument185 pagesMaintenance and Service GuidenstomarNo ratings yet

- LEARNING OBJECTIVESpart2Document4 pagesLEARNING OBJECTIVESpart2sere marcNo ratings yet

- GNM 10102023Document118 pagesGNM 10102023mohammedfz19999No ratings yet

- AYUDA Multi-Words VerbsDocument6 pagesAYUDA Multi-Words VerbsGabriel RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Common Customer Gateway Product SheetDocument2 pagesCommon Customer Gateway Product SheetNYSE TechnologiesNo ratings yet

- Lasallian Core ValuesDocument1 pageLasallian Core ValuesLindaRidzuanNo ratings yet

- Emergency Management of Stroke PDFDocument7 pagesEmergency Management of Stroke PDFAnonymous jgiYfzNo ratings yet

- Election Summary Report November 3, 2020 - General Election Wayne County, Michigan Unofficial ResultsDocument77 pagesElection Summary Report November 3, 2020 - General Election Wayne County, Michigan Unofficial ResultsStephen BoyleNo ratings yet

- Rouge No DengonDocument2 pagesRouge No DengonNaylimar D Alvarez CNo ratings yet

- Gerunds and Infinitives 8897Document3 pagesGerunds and Infinitives 8897aura lucy estupiñan gutierrezNo ratings yet

- Srimad Bhagavatam 2nd CantoDocument25 pagesSrimad Bhagavatam 2nd CantoDeepak K OONo ratings yet

- Methodology of Academic Writing (MOAW) LessonsDocument17 pagesMethodology of Academic Writing (MOAW) LessonsMiro MiroNo ratings yet

- The Small Trees High Productivity Initiative: Principles and Practice in High Density Orchard DesignDocument1 pageThe Small Trees High Productivity Initiative: Principles and Practice in High Density Orchard DesignPutchong SaraNo ratings yet

- Cns 1,2,3 CeDocument21 pagesCns 1,2,3 Cejay0% (1)

- Quiz ManaSciDocument15 pagesQuiz ManaSciRocio Isabel LuzuriagaNo ratings yet

- Poultry Fool & FinalDocument42 pagesPoultry Fool & Finalaashikjayswal8No ratings yet

- Beautiful Fighting Girl - Book ReviewDocument3 pagesBeautiful Fighting Girl - Book ReviewCharisse Mae Berco - MaribongNo ratings yet