Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Magallón-Neri 2016 Smartphones

Uploaded by

uricomasCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Magallón-Neri 2016 Smartphones

Uploaded by

uricomasCopyright:

Available Formats

WJ P World Journal of

Psychiatry

Submit a Manuscript: http://www.wjgnet.com/esps/ World J Psychiatr 2016 September 22; 6(3): 303-310

Help Desk: http://www.wjgnet.com/esps/helpdesk.aspx ISSN 2220-3206 (online)

DOI: 10.5498/wjp.v6.i3.303 © 2016 Baishideng Publishing Group Inc. All rights reserved.

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Basic Study

Ecological Momentary Assessment with smartphones for

measuring mental health problems in adolescents

Ernesto Magallón-Neri, Teresa Kirchner-Nebot, Maria Forns-Santacana, Caterina Calderón, Irina Planellas

Ernesto Magallón-Neri, Teresa Kirchner-Nebot, Maria Forns- work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on

Santacana, Institute of Research in Brain, Cognition and Behavior different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and

(IR3c), 08036 Barcelona, Spain the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/

licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Ernesto Magallón-Neri, Teresa Kirchner-Nebot, Maria Forns-

Santacana, Caterina Calderón, Research Group on Measure Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Invariance and Analysis of Change (GEIMAC), 08036 Barcelona,

Spain Correspondence to: Ernesto Magallón-Neri, PhD, Professor,

Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychobiology, Personality,

Ernesto Magallón-Neri, Teresa Kirchner-Nebot, Maria Forns- Assessment and Psychological Treatment Section, University of

Santacana, Caterina Calderón, Irina Planellas, Department of Barcelona, Pg. Vall d Hebron, 171, 08036 Barcelona,

Clinical Psychology and Psychobiology, Personality, Assessment Spain. emagallonneri@ub.edu

and Psychological Treatment Section, University of Barcelona, Telephone: +34-93-3125096

08036 Barcelona, Spain Fax: +34-93-4021362

Author contributions: Magallón-Neri E designed and coordinated Received: June 18, 2016

the research, acquired the data, wrote the paper, analyzed and Peer-review started: June 29, 2016

interpreted the data; Kirchner-Nebot T and Forns-Santacana M First decision: August 5, 2016

designed and coordinated the research, revised made critical Revised: August 11, 2016

revisions of the paper and acquired the data; Calderón C and Accepted: August 27, 2016

Planellas I acquired the data. Article in press: August 29, 2016

Published online: September 22, 2016

Supported by Spain’s Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness,

No. PSI 2013-46392-P; and the Agency for the Management of

University and Research Grants from the Government of Catalonia,

No. 2014SGR1139.

Abstract

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed AIM

and approved by the University of Barcelona Institutional Review To analyze the viability of Ecological Momentary Assessment

Board Number: 00003099.

(EMA) for measuring the mental states associated with

Institutional animal care and use committee statement: All

psychopathological problems in adolescents.

procedures involving animals were reviewed and approved by the

Bioethics Committee. METHODS

In a sample of 110 adolescents, a sociodemographic data

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare that they survey and an EMA Smartphone application over a one-

have no conflict of interest. week period (five times each day), was developed to explore

symptom profiles, everyday problems, coping strategies, and

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available. the contexts in which the events take place.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was

selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external RESULTS

reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative The positive response was 68.6%. Over 2250 prompts

Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, about mental states were recorded. In 53% of situations

which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this the smartphone was answered at home, 25.5% of cases

WJP|www.wjgnet.com 303 September 22, 2016|Volume 6|Issue 3|

Magallón-Neri E et al . Ecological Momentary Assessment in adolescent mental health

they were with their parents or with peers (20.3%). (EMA). This methodology allows the recording of the

Associations were found with attention, affective and expression of mental microprocesses and their fluc

anxiety problems (P < 0.001) in the participants who took tuations in several situational contexts as they happen .

[7]

longer to respond to the EMA app. Anxious and depressive Its applicability has been demonstrated in a variety of

states were highly interrelated (rho = 0.51, P < 0.001), populations in studies of general health .

[8]

as well as oppositional defiant problems and conduct Specifically, in adolescent samples, EMA has been

problems (rho = 0.56, P < 0.001). Only in 6.2% of the [9]

used to assess or predict health needs , mental status

[10]

situations the subjects perceived they had problems, [11] [12]

emotional instability , drug use , stress associated

mainly associated with inter-relational aspects with [13]

with traumatic events , and anxiety problems .

[14]

family, peers, boyfriends or girlfriends (31.2%). We also [7]

In fact EMA has been used for decades , but reports

found moderate-high reliability on scales of satisfaction of its use in the field of mental health are relatively

level on the context, on positive emotionality, and on the

recent. At present there is no evidence of its use in ado

discomfort index associated with mental health problems.

lescent community populations to measure broad areas

of psychopathological symptoms (sadness, anxiety,

CONCLUSION

somatic, thought, behavioral and attentional problems) in

EMA methodology using smartphones is a useful tool for

understanding adolescents’ daily dynamics. It achieved real time in their natural setting, focusing on the coping

moderate-high reliability and accurately identified psycho strategies used and their relation to their situational and

pathological manifestations experienced by community personal contexts.

adolescents in their natural context. The aim of this study is to explore the viability of

EMA for measuring the mental states associated with

Key words: Ecological Momentary Assessment; Mental psychopathological problems in adolescents, taking into

health problems; Smartphone; Coping; Adolescents account the situational context and the coping strategies

they apply.

© The Author(s) 2016. Published by Baishideng Publishing

Group Inc. All rights reserved.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Core tip: Adolescence is a stage of life characterized Participants

by a great many changes. If they are not coped with The sample was constituted initially by 110 adolescents

effectively, these changes may trigger mental health from the province of Barcelona, of whom 101 successfully

problems. Among the range of methodologies used completed the EMA study. Following the recommendations

to assess the impact of daily problems, Ecological of previous researchers regarding the quality of infor

Momentary Assessment allows the recording of mental mation

[6,15]

, only subjects who completed at least 12 of the

microprocesses and fluctuations as they happen. We found 35 possible recordings (roughly 33%) were considered.

anxious and depressive states were highly interrelated,

as well as oppositional defiant problems and conduct

problems in daily life. This methodology based on mobile Instruments

technology using smartphones is a useful tool with high Sociodemographic data: A survey sheet was created

viability for measuring psychopathological mental states in ad hoc to gather basic data on age, gender, school year,

adolescents in their natural context. citizenship, family and employment status.

EMA

Magallón-Neri E, Kirchner-Nebot T, Forns-Santacana M, Calderón C, Each participant received a smartphone with an Android-

Planellas I. Ecological Momentary Assessment with smartphones based EMA application already installed. This application

for measuring mental health problems in adolescents. World J was programmed to give a series of alarms associated

Psychiatr 2016; 6(3): 303-310 Available from: URL: http://www. with the task of answering mini-questionnaires at five

wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v6/i3/303.htm DOI: http://dx.doi. semi-random moments over the course of the day

org/10.5498/wjp.v6.i3.303 between 9 am and 9 pm for a complete week. The mini-

questionnaires comprised 21 items (five with multiple

choice answers, two with yes/no answers, 14 to be

rated on a 5-point Likert scale) which participants were

required to answer within three minutes of hearing the

INTRODUCTION first alarm. If the user did not start to answer within this

Adolescence is a stage of life characterized by a great period of time the application stopped the smartphone

many changes which, if not addressed effectively, alarm and blocked the unit.

[1-5]

may trigger problems of mental health . There is a Users could not delay their answers beyond five

substantial body of literature assessing the possible minutes after their last interaction with the application, or

impact of individual everyday problems on the develop take longer than ten minutes to answer the entire mini-

[6]

ment of mental health disorders . questionnaire, in order to ensure that the information

One of the formats used to assess the impact of was instantaneous and not retrospective. If users were

everyday problems is Ecological Momentary Assessment unable to answer within these time limits the application

WJP|www.wjgnet.com 304 September 22, 2016|Volume 6|Issue 3|

Magallón-Neri E et al . Ecological Momentary Assessment in adolescent mental health

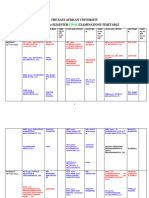

Figure 1 Example of questions asked within Ecological Momentary

Assessment app in this study.

At the moment I am... At the moment do you At the moment do you

have any trouble? feel anxious?

1. At home

2. At school

3. In the park 1 2 3 4 5

4. Shopping Yes

Not al all

5. On the street

6. Somewhere else No

A lot

blocked the smartphone and they were told to wait and that they should answer as often as possible. They

until the next random alarm; this reply attempt was were also asked as well to sign a commitment to take

considered empty. good care of the smartphone and received an information

These mini-questionnaires comprised questions sheet explaining how the smartphone functioned and

regarding situational context and broad areas associated how to answer and containing contact data in case of any

with psychopathological problems such as behavior technical problem during the experiment.

problems, anxiety, sadness, lack of concentration, and

so on. It also covered everyday problems and how to Statistical analysis

2

cope with them. Figure 1 shows an example of the The χ test was used to calculate differences between

questions asked. proportions in frequencies, the t-student test to calculate

The application stored the data collected for a week differences of means between two groups, ANOVA for

(7 d). Once the evaluation period finished, the data comparisons between several subgroups with Bonferroni

were downloaded by the research team. As a result, a correction, and Spearman correlations to calculate

maximum of 35 moments of semi-random evaluation associations between variables.

were obtained from each subject. Figure 2 displays the

EMA cycle used in this study.

RESULTS

Procedure Socio-demographic data

Several social service centers and schools in the metro The sample comprised 101 adolescents (age M = 14.68

politan Barcelona area and its surroundings were ± 1.64; 61% women). Sixty percent were Spanish

contacted. Two centers agreed to participate after a full natives and 40% were foreigners (28% were Latin

explanation of the project and its logistic implications Americans). Regarding family structure, between 67%

with regard to the distribution and application of EMA and 71% of participants’ parents were married and

methodology with smartphones. After obtaining the between 21% and 23% separated or divorced. As for

centers’ approval, 30-min information sessions were parents’ employment, 77% of fathers were employed

arranged for students from eighth to eleventh grade. In and 70% of mothers.

these sessions, students received explanations of their

role in the study and the implications of their participation. EMA answer rates

Informed consent forms were then distributed among the In all, 68.6% of questionnaires were completed, while

participants for authorization, either by the participants in 31.4% data were missing: Ignored alarms accounted

themselves or by their parents and/or tutors. All the for 23.9% of the missing data (due to a lack of time to

procedure and assessment protocols had been pre answer or not paying attention), rejected answer attempts

viously authorized by the research ethical committee for 4.5%, and incomplete records not quantified in the

of the University, and complied with the guidelines of analysis for 3.0%. The difference between the types of

2

the Declaration of Helsinki and legislation regarding answer was significant (χ = 3712.60; P < 0.001). The

confidential data protection. mean time taken to answer the questionnaires was 80.6

After obtaining written consent, meetings were s ± 56.5 s. These data suggest a mean answer time of

arranged for explaining the instruments and the workings between one and three minutes.

of the smartphone devices and EMA app functioning. On

receiving the smartphone, participants were assigned an Contextual variables

individual alphanumeric code to protect their identity in Variables about the context (Where, who with, and

case of loss or theft of the device. They were informed what were they doing?). In 53% of situations the smart

that they would have the phone for a whole week and phone was answered at home, followed by 24.3% at

that it would ring five times a day at semi-random times, school and 15.5% outside in the street. There were

WJP|www.wjgnet.com 305 September 22, 2016|Volume 6|Issue 3|

Magallón-Neri E et al . Ecological Momentary Assessment in adolescent mental health

How does EMA technology work?

Mental health research group

Smartphone android

Control

Server data storage

center

Results summary

User interface

internal functions

Participant patient external services

Local data storage Internet

Parents/educators

Figure 2 Assessment cycle used in this study with Ecological Momentary Assessment methodology.

significant differences between these three response symptoms: Affective (79%), anxious (78.2%), somatic

2

contexts (χ = 1072.38; df = 2; P < 0.001). On a (84.3%), inattentive (81%), oppositional (93.7%),

1-5 point Likert scale, in 69% of cases the situational aggressive (95%), obsessive-compulsive (82.6%) or

context was assessed as pleasant (a score of 4) or very traumatic (93.6%). All these situational problems were

pleasant (a score of 5). Only in 11.2% of the situations significantly absent (P < 0.001). Regarding the intensity

was the context unpleasant or very unpleasant (scores of problems according to gender, girls presented more

of 1 or 2). affective (t = -9.077; P < 0.001), anxious (t = -4.808;

Regarding the people being with the adolescents at P < 0.001), somatic (t = -6.603; P < 0.001) and post-

the time of assessments, in 25.5% of cases they were traumatic symptoms (t = -4.040; P < 0.001) than boys.

with their parents, in 20.3% with peers and in 19.1% Boys presented slightly more inattentive-hyperactive

alone. There were significant differences between these problems (t = 2.046; P = 0.041), but there were no

2

three groups (χ = 25.28; df = 2; P < 0.001). The significant differences in other disruptive behaviors

company was regarded as pleasant or very pleasant in or obsessive-compulsive problems in daily life. All

77.9% of situations and unpleasant or very unpleasant eight items constituting the general discomfort index

in only 7.1%. associated with momentary mental health problems

The three activities that participants were most obtained a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.76.

frequently engaged in at the time of answering the EMA It was also observed that subjects who presented

questionnaires were school tasks or activities (26.7%), strong situational problems of inattention, sadness or

talking to somebody (19.7%), and watching TV or the anxiety, they also took longer to respond (120 s ± 78

computer (16.8%). There were significant differences s for inattention; 111 s ± 57 s for sadness; and 122 s

2

between these three activities (χ = 58.11; df = 2; P ± 79 s for anxiety) than subjects who did not present

< 0.001). The adolescents regarded the activities they these problems (75 s ± 52 s in absence of inattention,

were engaged in when they answered the smartphone 76 ± 53 s in absence of sadness and 75 s ± 53 s in

as pleasant or very pleasant in 64% of cases and absence of anxiety). The difference was significant (F =

2

as unpleasant or very unpleasant in only 8.9% (χ 37.15; df = 4; P < 0.001 for inattention; F = 28.31; df

= 113.49; df = 3; P < 0.001). The momentary level = 4; P < 0.001 for sadness; and F = 31.33; df = 4; P <

of satisfaction associated with the context (physical, 0.001 for anxiety). Bonferroni’s post-hoc results showed

relational and activity-related) composed by three that significant differences appeared essentially between

items, obtained a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75. subjects who did not have these problems and subjects

who had them with a certain degree of intensity.

Momentary emotional status and behaviors With regard to situations associated with positive

In a collection of around 2250 responses obtained emotionality, in particular to feeling happy or loved,

from the participants during the week, it was found subjects reported being happy or very happy (64.2%

that in most of situations, these people reported the of cases) and feeling loved or loved very much (66% of

absence of problems associated with the following cases). There were significant differences in comparison

WJP|www.wjgnet.com 306 September 22, 2016|Volume 6|Issue 3|

Magallón-Neri E et al . Ecological Momentary Assessment in adolescent mental health

Table 1 Mental health symptomatology areas measured by Ecological Momentary Assessment in boys and girls

Variables 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Affective problems -- 0.38 0.26 0.33 0.15 0.11 0.2 0.32

Anxiety problems 0.57 -- 0.23 0.35 0.18 0.14 0.27 0.18

Somatic problems 0.22 0.23 -- 0.14 0.12 0.09 0.20 0.10

Hyperactivity-Inattention problems 0.39 0.38 0.18 -- 0.22 0.21 0.34 0.28

Oppositional-defiant problems 0.27 0.30 0.19 0.29 -- 0.58 0.29 0.31

Conduct Behavior problems 0.27 0.31 0.20 0.27 0.56 -- 0.16 0.30

Obsessive compulsive problems 0.25 0.34 0.22 0.31 0.31 0.32 -- 0.31

Posttraumatic stress problems 0.34 0.36 0.19 0.34 0.47 0.46 0.39 --

Above the diagonal, boys’ results, below the diagonal, girls’ results. All the results are significant (P < 0.001). In bold-face, the correlations with high-

moderate index.

2

with unhappy situations (χ = 978.15; df = 4; P < of strategy, but in 28% they felt very satisfied. There

2

0.001) or situations in which one does not feel loved (χ were differences in the appreciation of the application

2

= 1101.58; df = 4; P < 0.001). The intensity of positive of coping strategies (χ = 35.92; df = 4; P < 0.001), in

emotionality of these two items obtained a Cronbach’s that case the majority believed them to be effective.

alpha of 0.81 in this study.

Anxious and depressive states were interrelated

in the whole sample (rho = 0.51; P < 0.001), and DISCUSSION

oppositional/defiant problems were associated with The most relevant result in this study is the finding

conduct problems (rho = 0.56; P < 0.001). Table 1 that in most situations in daily life (between 78% and

displays the relationship between problems associated 93%) adolescents do not present problems that trigger

with mental health symptoms by gender. Specifically, mental health symptoms. When these problems appear,

girls presented strong relationships between anxiety they tend to be closely related to states of sadness

and affective problems, oppositional/defiant problems or anxiety. Similarly, oppositional defiant behaviors

and conduct problems, posttraumatic stress problems were associated with conduct problems, a finding that

and disruptive behaviors, while in boys the only strong corroborates the syndromic daily patterns associated

relationship observed was between oppositional/defiant with the two broad areas of symptoms (internalizing/

problems and conduct problems. externalizing) regularly found in the field of child and

[16-18]

teenager psychopathology . It was also observed

Everyday problems and coping strategies that the positive response rate of the EMA app (68.6%),

Only in 6.2% of the situations in which they were asked and the time taken (about 1-2 min) reflect an accurate

to answer the mini-questionnaire with the smartphone measurement of associated context, the broad areas

did the subjects perceive they had a problem. The most of clinical symptomatology and coping strategies in

common problems, in order of frequency, were those real time. We also found moderate-high reliability on

associated with inter-relational aspects with family, scales of satisfaction level on the context, on positive

peers, boyfriends or girlfriends (31.2%), followed by emotionality, and on the discomfort index associated

schoolwork or worrying about exams (29.1%), and with mental health problems. These results show that

arguments or behavior problems (9.9%). Significant EMA methodology based on mobile technology offers

differences were found between these three types of high viability for measuring mental health states in

2

everyday problems in adolescents (χ = 14.80; df = 2; adolescents.

P = 0.001). Among the contextual variables, we stress that during

The most frequently used kind of coping strategy the week-long EMA, the adolescents were regularly at

when a problem appeared was seeking relaxing home when answering the smartphone application. This

diversions (21.5%), followed by trying to see the result should be borne in mind, due to the contextual

positive side of the situation (20.1%) and then seeking relation of family dynamics in the promotion and deve

help from peers (16%). The least used strategies lopment of symptomatology or solutions to everyday

were looking for help in the family (6.3%) and seeking problems.

spiritual support (1.4%). Significant differences were For their part, the results regarding satisfaction in the

2

found in the types of coping (χ = 38.23; df = 7; P < immediate context show that in most cases adolescents

0.001). feel satisfied with the surrounding environment (in this

Regarding their satisfaction with their coping str case their home). Moreover, in relation to variables of

ategies, on more than a third of occasions (35%) interpersonal contact, it is interesting that the people

adolescents felt neither happy nor unhappy with the with whom they have the most contact are their parents,

strategy chosen to face a specific problem. In 11.2% followed by their colleagues or peers: This finding may

of cases the subjects were discontent with their choice challenge the concept of adolescence as a stage in which

WJP|www.wjgnet.com 307 September 22, 2016|Volume 6|Issue 3|

Magallón-Neri E et al . Ecological Momentary Assessment in adolescent mental health

[4,5]

subjects prefer to be with their peers or alone . other hand, it is important to promote a high parental

Nevertheless, this does not mean that they prefer self-efficacy, which would be highly related to ecological

to be with their parents, because the adolescents variables and parenting competence, in such a way

can share a great deal of time together. Perhaps this that environmental conditions and ecological contexts

result reflects the fact that our adolescents regularly may influence and undermine parent’s confidence and

[22]

answered the application at home (53%), where they parenting competence .

are more likely to record direct contact with their This study has a number of limitations that may

parents. However, this shows us that the parents may affect the interpretation of the results. The first is the

play a significant role in their children’s development sample size. The application of the EMA methodology for

of functional patterns of psychological adaptation via seven consecutive days raises a series of logistical issues

this continuous contact during the adolescent stage, as that complicate the recruitment and maintenance of

[19]

stated previously by other authors . In adolescent- participants. Compared with the pencil-paper assessment

parent relationships related to parenting styles, it is at a specific moment, EMA offers a considerable number

highlighted the importance of authoritative homes of benefits (assessment in real time, decrease in memory

(where parents are both demanding and responsive) bias, contextual association) and drawbacks (time-

[5]

with more psychosocial and academic competence , limited evaluation, sampling, loss of important events

[7]

that prevent some potential risk situations such as and overload) as noted by Shiffman et al 2008, van Os

[3] [20] [23]

a problematic drug use , internalizing/externalizing et al 2014, and Stone 2007. All these points should

[4] [1]

symptoms or victimization problems . be taken into account when applying EMA. In fact, the

When studying daily patterns it is important to bear sample size in this study is within the range of most other

[12-14,24] [9-11,25]

in mind that the context and the people with whom we studies in clinical or community adolescent

are in contact have a strong effect on the activities we populations.

perform. Being in tune with the evolutive stage and Another issue to be considered is the type of po

the main function to be developed by adolescents at pulation studied. As our data are from a community

these ages. The adolescents reported that when they sample, they cannot be directly extrapolated to the

were had to answer the questionnaire, in more than a clinical population or to a specific subgroup with

quarter of the cases they were doing school homework, psychiatric disorders. Nevertheless, one should bear

followed by talking and leisure activities (TV-PC). Here in mind that the clinical population is a particular and

the level of pleasure was influenced considerably by acute subgroup of the community population. This

[4]

their interaction with the place and the people present . study may represent a first step in the advancement

Being the homework an activity regularly imposed, they of knowledge of daily patterns associated with mental

reflect their perception of not being completely satisfied health problems in adolescence and the assessment of

with this activity development, not necessarily meaning contextual variables and coping strategies. Third, as this

extreme dissatisfaction level, in this contextual activity. assessment study was carried out over a week, it would

In relation to emotional states, momentary sym be interesting to compare these results with those from

ptomatology was broadly absent in the different areas wider populations with specific psychiatric disorders, over

studied (affective, anxious, somatic, inattentive, oppo different time periods, and with a longitudinal design.

sitionist, aggressive behavior, obsessive-compulsive Despite these limitations, this is, to our knowledge, the

problems, and trauma situations). first study in adolescents to apply the smartphone-based

In general, the low results for impairment obtained EMA methodology to measure the triad of contextual

reflect the type of population studied (i.e., a community variables, symptoms associated with mental health

population). Higher reports of impairment would be problems and coping strategies.

likely if the assessment had been applied in a clinical EMA methodology using smartphones is a useful

[6,20]

sample . The intensity of impairments may also tool for assessing daily dynamics. It provides a suffi

depend on the level of clinical assistance received (out ciently accurate measure of the psychopathological

patient, day hospital or inpatient). These hypotheses manifestations experienced by community adolescents

should be verified in further studies of clinical samples in their natural context. In the study of momentary

of adolescents with psychiatric disorders. states associated with mental health symptomatology

The perception of everyday problems and the use of over a one-week period, we found that in most cases

coping strategies is an interesting result. Only rarely did adolescents do not present emotional alterations or

the adolescents record the presence of problems in the problems in their daily life. Girls were slightly more

assessment, the most frequent being inter-relational affected in their momentary emotional status and

and academic performance problems. This reflects the behaviors in daily life than boys. And among the situ

main worries of adolescents at this development stage, ations in which a conflict is generated - on the one

characterized by openness to new experiences in the hand, anxious-depressed states, and on the other

[5]

field of social relations and an increase in academic the oppositional-aggressive behavior are closely inter-

pressure prior to entry to university or to a vocational related. Our results show that the family and home

training center. Similar results has been obtained by context could be crucial for the potential development of

[21]

other others using traditional methodology . On the training interactions, both positive and negative, in the

WJP|www.wjgnet.com 308 September 22, 2016|Volume 6|Issue 3|

Magallón-Neri E et al . Ecological Momentary Assessment in adolescent mental health

mental health field, and they also stress the importance 5 Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescent development. Annu Rev

of individuals’ coping resources in relation with their Psychol 2001; 52: 83-110 [PMID: 11148300 DOI: 10.1146/annurev.

psych.52.1.83]

formative, relational, and physical context.

6 Palmier-Claus JE, Myin-Germeys I, Barkus E, Bentley L,

Udachina A, Delespaul PA, Lewis SW, Dunn G. Experience

sampling research in individuals with mental illness: reflections

COMMENTS

COMMENTS and guidance. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2011; 123: 12-20 [PMID:

20712828 DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01596.x]

Background

7 Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary asse

Adolescence is a stage of life characterized by a great many changes which,

ssment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2008; 4: 1-32 [PMID: 18509902

if not addressed effectively, may trigger problems of mental health. There is

DOI: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415]

a substantial body of literature assessing the possible impact of individual

8 Runyan JD, Steinke EG. Virtues, ecological momentary asse

everyday problems on the development of mental health disorders.

ssment/intervention and smartphone technology. Front Psychol

2015; 6: 481 [PMID: 25999869 DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00481]

Research frontiers 9 Schnall R, Okoniewski A, Tiase V, Low A, Rodriguez M, Kaplan

Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) is a methodology allows to assess S. Using text messaging to assess adolescents’ health information

the impact of everyday problems in several situational contexts as they happen. needs: an ecological momentary assessment. J Med Internet Res

Its applicability has been demonstrated in a variety of populations in studies of 2013; 15: e54 [PMID: 23467200 DOI: 10.2196/jmir.2395]

general health. 10 Garcia C, Hardeman RR, Kwon G, Lando-King E, Zhang L,

Genis T, Brady SS, Kinder E. Teenagers and texting: use of a youth

ecological momentary assessment system in trajectory health

Innovations and breakthroughs

research with latina adolescents. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2014; 2: e3

This study may represent a first step in the advancement of knowledge of

[PMID: 25098355 DOI: 10.2196/mhealth.2576]

daily patterns associated with mental health problems in adolescence and the

11 Aldinger M, Stopsack M, Ulrich I, Appel K, Reinelt E, Wolff S,

assessment of contextual variables and coping strategies. The results show

Grabe HJ, Lang S, Barnow S. Neuroticism developmental courses-

that EMA methodology based on mobile technology offers high viability for

-implications for depression, anxiety and everyday emotional

measuring mental health states in adolescents.

experience; a prospective study from adolescence to young adulthood.

BMC Psychiatry 2014; 14: 210 [PMID: 25207861 DOI: 10.1186/

Applications s12888-014-0210-2]

EMA methodology using smartphones is a useful tool for assessing daily 12 Comulada WS, Lightfoot M, Swendeman D, Grella C, Wu N.

dynamics. It provides a sufficiently accurate measure of the psychopathological Compliance to Cell Phone-Based EMA Among Latino Youth in

manifestations experienced by community adolescents in their natural context. Outpatient Treatment. J Ethn Subst Abuse 2015; 14: 232-250 [PMID:

26114764 DOI: 10.1080/15332640.2014.986354]

13 Walsh K, Basu A, Monk C. The Role of Sexual Abuse and

Terminology

Dysfunctional Attitudes in Perceived Stress and Negative Mood

EMA is a methodology that allows the recording of the expression of mental

in Pregnant Adolescents: An Ecological Momentary Assessment

microprocesses and their fluctuations in several situational contexts as they

Study. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2015; 28: 327-332 [PMID:

happen. Compared with the pencil-paper assessment at a specific moment,

26130137 DOI: 10.1016/j.jpag.2014.09.012]

EMA offers a considerable number of benefits (assessment in real time,

14 Walz LC, Nauta MH, Aan Het Rot M. Experience sampling and

decrease in memory bias, contextual association) and also drawbacks (time-

limited evaluation, sampling, loss of important events and overload). ecological momentary assessment for studying the daily lives of patients

with anxiety disorders: a systematic review. J Anxiety Disord 2014; 28:

925-937 [PMID: 25445083 DOI: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.09.022]

Peer-review 15 Cordier R, Brown N, Chen YW, Wilkes-Gillan S, Falkmer T.

The authors have reported their findings based on EMA with Smartphones for Piloting the use of experience sampling method to investigate the

measuring mental health problems in adolescents. The study was well taken everyday social experiences of children with Asperger syndrome/

and the results indicate that such an evaluation is helpful to assess whether high functioning autism. Dev Neurorehabil 2016; 19: 103-110

using smartphones is a useful tool for assessing daily dynamics or sufficiently [PMID: 24840290 DOI: 10.3109/17518423.2014.915244]

accurate measure of the psychopathological manifestations experienced by 16 Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age

community adolescents. Forms & Profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research

Center for Children, Youth, & Families, 2001

17 Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Multicultural supplement of the

REFERENCES manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington:

1 Forns M, Kirchner T, Gómez,-Maqueo EL, Landgrave P, Soler L, University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, &

Calderón C, Magallón-Neri E. The ability of multi-type maltreatment Families, 2007

and poly-victimization approaches to reflect psychopathological 18 Ivanova MY, Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA, Dumenci L, Almqvist

impairment of victimization in Spanish community adolescents. J F, Bilenberg N, Bird H, Broberg AG, Dobrean A, Döpfner M,

Child Adolesc Behav 2015; 3: 187 [DOI: 10.4172/2375-4494.100018 Erol N, Forns M, Hannesdottir H, Kanbayashi Y, Lambert MC,

7] Leung P, Minaei A, Mulatu MS, Novik T, Oh KJ, Roussos A,

2 Kirchner T, Forns M, Amador JA, Muñoz D. Stability and consistency Sawyer M, Simsek Z, Steinhausen HC, Weintraub S, Winkler

of coping in adolescence: A longitudinal study. Psicothema 2010; 22: Metzke C, Wolanczyk T, Zilber N, Zukauskiene R, Verhulst FC.

382-388 [PMID: 20667264] The generalizability of the Youth Self-Report syndrome structure

3 Magallón-Neri E, Díaz R, Forns M, Goti J, Castro-Fornieles J. in 23 societies. J Consult Clin Psychol 2007; 75: 729-738 [PMID:

Personality psychopathology, drug use and psychological symptoms 17907855 DOI: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.729]

in adolescents with substance use disorders and community 19 Jessor R, Van Den Bos J, Vanderryn J, Costa JM, Turbin MS.

controls. PeerJ 2015; 3: e992 [PMID: 26082873 DOI: 10.7717/ Protective factors in Adolescent Problem Behavior: Moderator

peerj.992] Effects and Developmental Change. Dev Psychol 1995; 31: 923-933

4 Smetana JG, Campione-Barr N, Metzger A. Adolescent develo [DOI: 10.1037/0012-1649.31.6.923]

pment in interpersonal and societal contexts. Annu Rev Psychol 20 van Os J, Lataster T, Delespaul P, Wichers M, Myin-Germeys I.

2006; 57: 255-284 [PMID: 16318596 DOI: 10.1146/annurev. Evidence that a psychopathology interactome has diagnostic value,

psych.57.102904.190124] predicting clinical needs: an experience sampling study. PLoS

WJP|www.wjgnet.com 309 September 22, 2016|Volume 6|Issue 3|

Magallón-Neri E et al . Ecological Momentary Assessment in adolescent mental health

One 2014; 9: e86652 [PMID: 24466189 DOI: 10.1371/journal. research. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007

pone.0086652] 24 Khor AS, Gray KM, Reid SC, Melvin GA. Feasibility and validity

21 Forns M, Amador JA, Kirchner T, Martorell B, Zanini D, Muro P. of ecological momentary assessment in adolescents with high-

Sistema de codificación y análisis diferencial de los problemas de functioning autism and Asperger’s disorder. J Adolesc 2014; 37:

los adolescentes. Psicothema 2004; 16: 646-653 37-46 [PMID: 24331303 DOI: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.10.005]

22 Jones TL, Prinz RJ. Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in 25 Roberts ME, Bidwell LC, Colby SM, Gwaltney CJ. With others or

parent and child adjustment: a review. Clin Psychol Rev 2005; 25: alone? Adolescent individual differences in the context of smoking

341-363 [PMID: 15792853 DOI: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.004] lapses. Health Psychol 2015; 34: 1066-1075 [PMID: 25664557

23 Stone A. The science of real-time data capture: self-reports in health DOI: 10.1037/hea0000211]

P- Reviewer: Krishnan T, Nechifor G S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A

E- Editor: Lu YJ

WJP|www.wjgnet.com 310 September 22, 2016|Volume 6|Issue 3|

Published by Baishideng Publishing Group Inc

8226 Regency Drive, Pleasanton, CA 94588, USA

Telephone: +1-925-223-8242

Fax: +1-925-223-8243

E-mail: bpgoffice@wjgnet.com

Help Desk: http://www.wjgnet.com/esps/helpdesk.aspx

http://www.wjgnet.com

© 2016 Baishideng Publishing Group Inc. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- 2019 - Conners 3 ADHD SymptomsDocument18 pages2019 - Conners 3 ADHD Symptomsblanca_dhNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Sensory Processing and Executive Functions Un ChildhoodDocument12 pagesAssessment of Sensory Processing and Executive Functions Un ChildhoodMariMartinPedroNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Smart Phone Addiction, Sleep Quality and Associated Behaviour Problems in AdolescentsDocument5 pagesPrevalence of Smart Phone Addiction, Sleep Quality and Associated Behaviour Problems in AdolescentsRupika DhurjatiNo ratings yet

- Developing a Product Team ChecklistDocument5 pagesDeveloping a Product Team ChecklistMohammad AmirNo ratings yet

- 2 PBDocument19 pages2 PBAna CastañedaNo ratings yet

- 2021 - Investigacion - Publicaciones - Detectaweb DistressDocument14 pages2021 - Investigacion - Publicaciones - Detectaweb DistressJose Antonio Piqueras RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Bautista Et Al. 2023 Padres Niños CáncerDocument13 pagesBautista Et Al. 2023 Padres Niños CáncerDiazAlejoPhierinaNo ratings yet

- Jensen Et Al 2019 Young Adolescents Digital Technology Use and Mental Health Symptoms Little Evidence of LongitudinalDocument18 pagesJensen Et Al 2019 Young Adolescents Digital Technology Use and Mental Health Symptoms Little Evidence of LongitudinalBhakteshNo ratings yet

- Sciencedirect: Behavior Therapy XX (XXXX) XXXDocument13 pagesSciencedirect: Behavior Therapy XX (XXXX) XXXSilvia BautistaNo ratings yet

- Fernandez 2022 Smartphone Famliy ConnectionsDocument7 pagesFernandez 2022 Smartphone Famliy ConnectionsBrayan PomaNo ratings yet

- An In-Depth Analysis of Machine Learning Approaches To Predict DepressionDocument12 pagesAn In-Depth Analysis of Machine Learning Approaches To Predict DepressionDilshan SonnadaraNo ratings yet

- Thompson Et Al. (2021) - Internet-Based Acceptance and Commitment TherapyDocument16 pagesThompson Et Al. (2021) - Internet-Based Acceptance and Commitment TherapyDaniel Garvi de Castro100% (1)

- Magallón-Neri 2018 Victimization AdolescentsDocument9 pagesMagallón-Neri 2018 Victimization AdolescentsuricomasNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 3Document19 pagesJurnal 3Belajar KedokteranNo ratings yet

- Gaming Disorder 2Document15 pagesGaming Disorder 2nita kartikanNo ratings yet

- Fpsyg 12 616426Document7 pagesFpsyg 12 616426Fabrizio ForlaniNo ratings yet

- MEMO: An Mhealth Intervention To Prevent The Onset of Depression in Adolescents: A Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesMEMO: An Mhealth Intervention To Prevent The Onset of Depression in Adolescents: A Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled TrialSzeberényi AdriánNo ratings yet

- A Longitudinal Study of The Effects of ProblematicDocument10 pagesA Longitudinal Study of The Effects of ProblematicJana AlvesNo ratings yet

- Garca-Escaleraetal 2017 StudyprotocolUP-ADocument19 pagesGarca-Escaleraetal 2017 StudyprotocolUP-Aracm89No ratings yet

- 1851 Mychailyszyn 2017Document11 pages1851 Mychailyszyn 2017GanellNo ratings yet

- 10 3389@fpsyg 2018 00787Document15 pages10 3389@fpsyg 2018 00787Tony StarkNo ratings yet

- CD011144 AbstractDocument4 pagesCD011144 AbstractOktavia Pratiwi 1721303402No ratings yet

- J Osma, Laura Martínez-García, Óscar Peris - Baquero, María Vicenta Navarro - Haro, Alberto González - Pérez, Carlos Suso - RiberaDocument9 pagesJ Osma, Laura Martínez-García, Óscar Peris - Baquero, María Vicenta Navarro - Haro, Alberto González - Pérez, Carlos Suso - RiberaCarlos Suso RiberaNo ratings yet

- HHS Public AccessDocument21 pagesHHS Public AccessNerea F GNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2352853222000323 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S2352853222000323 MaindanielwongtsNo ratings yet

- Original ArticlesDocument7 pagesOriginal ArticlesĐan TâmNo ratings yet

- Fnsys 15 828685Document8 pagesFnsys 15 828685Jon SNo ratings yet

- Activation Vs Experiential Avoidance As A Transdia PDFDocument12 pagesActivation Vs Experiential Avoidance As A Transdia PDFpsicologia ejartNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Intervention for Social Challenges in Children and AdolescentsDocument12 pagesBehavioral Intervention for Social Challenges in Children and AdolescentslidiaNo ratings yet

- Comparative Efficacy and Acceptability of Bibliotherapy For Depression and Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents A Meta Analysis ofDocument14 pagesComparative Efficacy and Acceptability of Bibliotherapy For Depression and Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents A Meta Analysis ofThresia TuaselaNo ratings yet

- Predictors of Adherence Among Community Users of A Cognitive Behavior Therapy WebsiteDocument10 pagesPredictors of Adherence Among Community Users of A Cognitive Behavior Therapy WebsiteMagda MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Research Open AccessDocument10 pagesResearch Open AccessAreson SanuNo ratings yet

- Mental health of older adults after natural disastersDocument10 pagesMental health of older adults after natural disastersmsoto20052576No ratings yet

- Executive Processes and Emotional and Behavioural Problems in Youths Under Protective MeasuresDocument9 pagesExecutive Processes and Emotional and Behavioural Problems in Youths Under Protective MeasuresNerea F GNo ratings yet

- JPHR 2021 2404Document4 pagesJPHR 2021 2404Maria UlfaNo ratings yet

- stamped_fd35c536-8e1a-4e62-8cc9-5cf676b6ebdfDocument13 pagesstamped_fd35c536-8e1a-4e62-8cc9-5cf676b6ebdfjessicatleiteNo ratings yet

- Coping With Stress in AdolescentsDocument9 pagesCoping With Stress in AdolescentsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Anak Jalanan 3Document7 pagesAnak Jalanan 3Erik MoodutoNo ratings yet

- Osodi Mental Health AdolescentesDocument16 pagesOsodi Mental Health Adolescentespaulacastell1No ratings yet

- Predicting Mental Health Using Machine LearningDocument8 pagesPredicting Mental Health Using Machine LearningRuthuja B PNo ratings yet

- Anxiety Symptoms in Adolescents at RiskDocument5 pagesAnxiety Symptoms in Adolescents at RiskifclarinNo ratings yet

- Impact of Adolescents Self Diagnosis of AnxietyDocument6 pagesImpact of Adolescents Self Diagnosis of AnxietyRenebel ClementeNo ratings yet

- Sand PlayDocument12 pagesSand PlayareviamdNo ratings yet

- DNB 29 2 207 13 LiDocument7 pagesDNB 29 2 207 13 LiMousumi MridhaNo ratings yet

- Tu 2003Document7 pagesTu 2003Stephany BoninNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument9 pagesContent ServerBiancaPopescuNo ratings yet

- Artigo 1Document15 pagesArtigo 1Marina PradoNo ratings yet

- 2017 - Meta-Analysis of Family-Based Selective Prevention Programs For Drug Consumption in AdolescenceDocument8 pages2017 - Meta-Analysis of Family-Based Selective Prevention Programs For Drug Consumption in AdolescenceÂngela MarreiroNo ratings yet

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Reducing Pediatric Cancer DistressDocument13 pagesCognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Reducing Pediatric Cancer DistressfitranoenoeNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Depression and Its Associated Factors Among Caregivers of Patients With SchizophreniaDocument7 pagesPrevalence of Depression and Its Associated Factors Among Caregivers of Patients With SchizophreniaFemin PrasadNo ratings yet

- Risk and Protective Factors and Processes For Behavioral SleepDocument19 pagesRisk and Protective Factors and Processes For Behavioral SleepJust a GirlNo ratings yet

- Decoding Rumination A Machine Learning Approach To A Tra - 2020 - Journal of PsDocument7 pagesDecoding Rumination A Machine Learning Approach To A Tra - 2020 - Journal of PsMichael WondemuNo ratings yet

- 2014 (Pupil Dilation)Document21 pages2014 (Pupil Dilation)Chop SueyNo ratings yet

- UC San Diego Previously Published WorksDocument12 pagesUC San Diego Previously Published WorkszahoNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Div MiliterDocument21 pagesJurnal Div MiliterAnonymous yzma2fFLjUNo ratings yet

- 2017 - SPRINGER - Emhealth Towards Emotion Health Through Depression Prediction and Intelligent Health Recommender SystemDocument11 pages2017 - SPRINGER - Emhealth Towards Emotion Health Through Depression Prediction and Intelligent Health Recommender SystemPriya KumariNo ratings yet

- DisasterDocument15 pagesDisasteradrianaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of A Psychological Intervention For Patients With Chronic Pain in Primary CareDocument12 pagesEvaluation of A Psychological Intervention For Patients With Chronic Pain in Primary CareYudith LouisaNo ratings yet

- Stark1996 - EstratégiasDocument25 pagesStark1996 - EstratégiasChana FernandesNo ratings yet

- Depression in Mexican Medical Students A Path Model AnalysisDocument7 pagesDepression in Mexican Medical Students A Path Model AnalysisVíctor Adrián Gómez AlcocerNo ratings yet

- Dimensional PsychopathologyFrom EverandDimensional PsychopathologyMassimo BiondiNo ratings yet

- Targum 2011Document5 pagesTargum 2011uricomasNo ratings yet

- 2022 RyanDeci SDT EncyclopediaDocument7 pages2022 RyanDeci SDT EncyclopediauricomasNo ratings yet

- The Risk of Developing Major DDocument12 pagesThe Risk of Developing Major DValerie Walker LagosNo ratings yet

- The Psychological Report A Review of Cur PDFDocument9 pagesThe Psychological Report A Review of Cur PDFBrooke EdelmanNo ratings yet

- 1 Risk Factors For Depression An Autobiographical ReviewDocument31 pages1 Risk Factors For Depression An Autobiographical ReviewАлексейNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Major Depression During Midlife Among A Community Sample of Women With and Without Prior Major Depression Are They The Same or DifferentDocument12 pagesRisk Factors For Major Depression During Midlife Among A Community Sample of Women With and Without Prior Major Depression Are They The Same or DifferenturicomasNo ratings yet

- Goodyer 2001Document7 pagesGoodyer 2001uricomasNo ratings yet

- Review: Major Depressive Disorder in Dsm-5: Implications For Clinical Practice and Research of Changes From Dsm-IvDocument13 pagesReview: Major Depressive Disorder in Dsm-5: Implications For Clinical Practice and Research of Changes From Dsm-IvCarlos GardelNo ratings yet

- Featured Reading 4Document23 pagesFeatured Reading 4ericaNo ratings yet

- NICEDocument233 pagesNICEuricomasNo ratings yet

- RichardsonDocument19 pagesRichardsonuricomasNo ratings yet

- D5 CarlsonDocument5 pagesD5 CarlsonuricomasNo ratings yet

- R1 LundbyDocument7 pagesR1 LundbyuricomasNo ratings yet

- Tesi Depressió 2Document144 pagesTesi Depressió 2uricomasNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With 1-Year Outcome ofDocument8 pagesFactors Associated With 1-Year Outcome ofuricomasNo ratings yet

- F3 Father Absence and Adolescent Depression andDocument15 pagesF3 Father Absence and Adolescent Depression anduricomasNo ratings yet

- Course Outline For The Online Class On Experimetl PsychDocument2 pagesCourse Outline For The Online Class On Experimetl PsychRix MarieNo ratings yet

- AI Sentiment AnalysisDocument22 pagesAI Sentiment AnalysisShailesh BhattaraiNo ratings yet

- Philosophy Homework #5Document4 pagesPhilosophy Homework #5uchiha kingNo ratings yet

- Social Anthropology EssayDocument4 pagesSocial Anthropology Essaymeghann.vanniekerkNo ratings yet

- Format For Research Paper (Immersion)Document4 pagesFormat For Research Paper (Immersion)Dayanara LabardaNo ratings yet

- Family: Different TheoriesDocument17 pagesFamily: Different TheoriesMark IganaNo ratings yet

- Estimasi Mortalitas Dengan MORTPAK 4.3Document20 pagesEstimasi Mortalitas Dengan MORTPAK 4.3Rani Aprilia PutriNo ratings yet

- Introduction To ARENA SimulationDocument25 pagesIntroduction To ARENA SimulationSam yousefNo ratings yet

- Module 2 Variables and DataDocument5 pagesModule 2 Variables and DataMyles DaroyNo ratings yet

- Examinations Final Time Table May-Aug 2022Document14 pagesExaminations Final Time Table May-Aug 2022Clinton otienoNo ratings yet

- Bibliography BooksDocument3 pagesBibliography Booksrmconvidhya sri2015No ratings yet

- Module 4 - Community Health AssessmentDocument8 pagesModule 4 - Community Health AssessmentSteffiNo ratings yet

- Political Awareness Among Faculty in Pakistani UniversitiesDocument17 pagesPolitical Awareness Among Faculty in Pakistani UniversitiesRentaCarNo ratings yet

- Psych AssDocument2 pagesPsych AssBagi RacelisNo ratings yet

- Applicationof Systems Theoryin EducationDocument5 pagesApplicationof Systems Theoryin Educationmary cristine veñegasNo ratings yet

- IPDP - 2022-2023 - With AccomplishmentDocument2 pagesIPDP - 2022-2023 - With Accomplishmentguinzadannhs bauko1No ratings yet

- Basic of Visual CommunicationDocument24 pagesBasic of Visual Communicationnurdayana khaliliNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology (2 Edition) : by Ranjit KumarDocument26 pagesResearch Methodology (2 Edition) : by Ranjit KumarTanvir Islam100% (1)

- Conflict and Conflict Management GuideDocument39 pagesConflict and Conflict Management GuideDaniel BalubalNo ratings yet

- Name of The Student Sap Id Course: Abhishek Kumar Gupta 500082899 Ape Gas StreamDocument10 pagesName of The Student Sap Id Course: Abhishek Kumar Gupta 500082899 Ape Gas StreamAbhishek GuptaNo ratings yet

- Building Social Literacy Skills in EducationDocument11 pagesBuilding Social Literacy Skills in EducationKim ArdaisNo ratings yet

- 4j Self Test 7 GrammarDocument3 pages4j Self Test 7 Grammarazam alfikri100% (1)

- SMKS IT Marinah Al-Hidayah Student ReportDocument19 pagesSMKS IT Marinah Al-Hidayah Student ReportSiti AisyahNo ratings yet

- Exploring Representations of Physically Disabled Women in Theory and Literature. WRIGHT, Diane J.Document164 pagesExploring Representations of Physically Disabled Women in Theory and Literature. WRIGHT, Diane J.author.avengingangelNo ratings yet

- Course Structure Ma - PsychologyDocument5 pagesCourse Structure Ma - PsychologyA PNo ratings yet

- How Culture Impacts Brand Perceptions Across NationsDocument12 pagesHow Culture Impacts Brand Perceptions Across NationsFlorencia IgnarioNo ratings yet

- Identifying Piaget's StagesDocument2 pagesIdentifying Piaget's StagesStephanie AltenhofNo ratings yet

- Six Essential Chapters in A Science AssignmentDocument3 pagesSix Essential Chapters in A Science AssignmentLarry kimNo ratings yet

- Vol 3 No 1 (2021) : EDULINK (Education and Linguistics Knowledge) JournalDocument15 pagesVol 3 No 1 (2021) : EDULINK (Education and Linguistics Knowledge) JournalRestu Suci UtamiNo ratings yet