Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Integrating Semi-Structured Somatic Practices and Contemporary Dance Technique Training

Uploaded by

Nehir CantasOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Integrating Semi-Structured Somatic Practices and Contemporary Dance Technique Training

Uploaded by

Nehir CantasCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Dance and Somatic Practices Volume 1 Number 2 © 2009 Intellect Ltd

Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/jdsp.1.2.237_1

Integrating semi-structured somatic

practices and contemporary dance

technique training

Rebecca Weber University of Central Lancashire

Abstract Keywords

Previous research has examined the effects of more structured somatic practices, somatic movement

sometimes referred to as ‘codified’ or ‘structural integrity techniques’, on contem- dance education

porary dance education, yet few researchers have addressed the effects of open- or semi-structured

semi-structured somatic frameworks. This article is presented in two parts: the framework

first part examines previous research as a ground from which to develop a method contemporary dance

to deliver and study the effects of less codified somatic frameworks within a contem- somatics

porary dance technique; the second part presents a short piece of practical research teaching practices

which developed from this basis. The research, conducted within a first-year col- technique

lege dance programme, consisted of a series of somatically informed contempo-

rary dance technique classes. Results of the study included students’ displaying

enhanced bodily connection, creativity, confidence and critical understanding of

tenets underlying somatic work, as well as some implications for dance technique.

It also addresses some of the issues arising from introducing semi-structured

frameworks within a contemporary technique class.

Previous research

The field of somatics, while still a relatively new and not-yet-mainstream

field, has experienced a growing momentum and more widespread recogni-

tion since its inception over 40 years ago. Many scholars have documented

the burgeoning interest in somatics within academic curricula and specifi-

cally with regards to its application within dance education programmes

(Myers 1980; Berardi 2007; Eddy 2009). Academic literature has focused

on why somatic modalities should be included in education programmes

(Kleinman 1990; Linden 1994; Fortin 1995; Eddy 2007) and dance pro-

grammes (Batson 1990; Green, 1999; Arnold 2005; Batson 2007; Batson

& Schwartz 2007; Debenham and Debenham 2008; Batson 2009; Fortin,

Viera and Tremblay 2009) and how to introduce somatic concepts to dance

technique classes (Fortin and Siedentop 1995; Bauer 1999; Brodie and

Lobel 2004; Long 2002; Fortin, Long and Lord 2002; Eddy 2006;

Enghauser 2007). Both mainstream culture (Orbach 2009) and dance cul-

ture call for an end to the Cartesian split through return to embodiment

and valuation of subjective experience, and somatics is a field that seeks to

repair the body/mind dualism through bodily awareness.

The term ‘somatic’ was first coined to describe the living body as expe-

rienced within from the first-person perspective. It is derived from the

JDSP 1 (2) pp. 237–254 © Intellect Ltd 2009 237

JDSP_1.2_art_Weber_237-254.indd 237 5/11/10 6:11:11 PM

1. See Eddy (2009) for Greek somatikos which means ‘of the body’ and was first introduced by

a brief but compre-

hensive overview of

Thomas Hanna (1970) to describe the mind/body integration that values this

the history and subjective experience and enhances embodied consciousness through the

development of the integration of perception and action: this pedagogy is at the core of all

field of somatics as

a whole to date.

the somatic modalities practised under the umbrella term ‘somatics’ today.

Hanna (1970) contended that movement originating from the unique, sub-

2. ISMETA grew out

of the previously

jective standpoint was empowering to the individual, as opposed to the scien-

founded International tifically valued, objective, third-person perspective, which was dichotomous

Movement Therapy and potentially disempowering.

Association to

include more focus

Somatics as a field continues to rely on and value subjective experience

on educators and as primary and focuses on how the body adapts to the continual flow of

a broader base of information gathered through interoceptive, proprioceptive and kinaes-

somatic pedagogies.

thetic sensing. As the field of somatics grew,1 somatic movement education

developed in the 1960s. A need for professional regulation and integrity

among practitioners and educators was recognized and the International

Somatic Movement Education and Therapy Association (ISMETA) was

formed2 to ‘promote a high level of standards and professionalism in the

field of somatic movement education and therapy through advocacy and

maintaining a registry of professional practitioners’ (ISMETA 2009).

As the field has grown and become more systematized through organi-

zations such as ISMETA, it has also gained popularity within academia,

becoming accepted study within somatic psychology, physical education

and dance education programmes internationally (Eddy 2009; Long 2002;

ISMETA 2009). Though all the many different somatic practices have dif-

ferent approaches, techniques and foci, many researchers highlight the

aspects which are common to all and which unite somatics as a field; for

instance, Rebecca Enghauser identifies the ‘most basic common denomi-

nator of these practices [as] the importance of the first-person, experiential

approach which emphasizes awareness of sensation’ (Enghauser 2007).

Other researchers propose the following as potential commonalities shared

across varying strands of practice:

• Sensitivity (both of our own inner landscapes and to the external environ-

ment), My Experienced Body/The Public Body (and inherent implications

of body image and personality development), and Political Implications

(Johnson 1986)

• Breath, sensing, connectivity and initiation (Brodie and Lobel 2004)

• Deep awareness, imagery and use of rest phases (Berardi 2007)

• Spatial-perceptual, kinaesthetic, breath, eco-somatic and creative body-

listening techniques (Enghauser 2007)

• Novel learning context, sensory attunement and augmented rest

(Batson 2009: 16)

Reviewing this list of attributes within different somatic practices, it seems

that these principles would readily apply to dance education as well, as

another physical, movement-based pedagogy. Indeed, as Martha Eddy

(2006) notes, many somatic practices have been developed by practition-

ers with dance backgrounds and contain a ‘dancer’s logic’ and languag-

ing, so the transition is easily facilitated. As Warwick Long notes, ‘One

way somatic education links with dance education is through learning to

238 Rebecca Weber

JDSP_1.2_art_Weber_237-254.indd 238 5/11/10 6:11:12 PM

direct attention to movement on an incrementally fine level. In the field of 3. With the notable

exception of Susan

somatic education this process of learning movement is termed sensory Bauer (1999), who

motor awareness’ (Fortin, Long and Lord 2002: 166). However, the focus touched briefly on

on how to teach dancers to direct their attention varies in somatics from Authentic Movement

after covering

traditional dance education, both in practical approach as well as in philo- the more codified

sophical and political underpinnings. The focus in somatics on valuing strands of Body-Mind

subjective experience re-positions authority on individual dancers through Centering, Ideokinesis

and Bartenieff

the variation in teaching techniques: Fundamentals.

4. For further clarifica-

Dance culture has modeled various external authorities (teachers’ cues, mir-

tion, semi-structured

rors, movement initiation) as validating and defining the principles of suc- frameworks can be

cess. While many dance practices, particularly those of the classic western thought of as a way

of working within

forms of ballet and modern dance techniques, embrace visual modeling to

the open framework

elucidate and communicate shape and ideal body patterning, somatics tends of self-discovery, but

more readily to embrace the use of verbal, haptic, kinesthetic, and proprio- with a specific ana-

tomical focus in mind

ceptive experience in defining form.

(Williamson 2010b).

(Batson and Schwartz 2007: 48)

Much of the focus on incorporating somatic principles into dance tech-

nique classes has been done by researchers who have been extensively

trained in various techniques and bring those techniques into the class-

room and their teaching ethos. Although many dance teachers actually

bring some aspects of somatics into the classroom, albeit without acknowl-

edging or perhaps even realizing they are doing so (Enghauser 2007), it

seems to be the consensus among researchers in the field of dance and

somatics that, although the practice is not yet ubiquitous, technique

classes can readily incorporate some of the more structured somatic

modalities (Bauer 1999; Brodie and Lobel 2004; Batson and Schwartz

2007), such as Ideokinesis (Batson 2007) and Body-Mind Centering

(Bauer 1999; Eddy 2006). However, few researchers3 have focused on the

incorporation of somatic practices that are categorized as ‘open framework

of self-discovery’ or ‘semi-structured framework’ modalities (Williamson

2009d, 2010a, 2010b). To clarify, the practices that are identified as

‘open framework of self-discovery’ and ‘semi-structured framework’ mod-

els are those that rely on more autonomy in movement response lying

with the client or student. As Williamson differentiates:

Open frameworks of self-discovery are not underpinned by explorations into spe-

cific anatomical ideas, but rather utilize an extremely open structure facilitated

through somatically-orientated language and are largely based on trusting the

sensual experience of the body – sensing into personal and unique movement

requirements and following pleasing movement desires (indulging in movement

sensual pathways, qualities and rhythms which feel enlivening or wholly satis-

fying). […] Semi-structured frameworks are more directed, aiming to offer expe-

riential insight into a particular anatomical or physiological idea.

(Williamson 2010a: 6–7)4

Working within either of these frameworks, practitioners rely on the

autonomy of clients/students to realign and re-pattern through somatic

awareness of what feels pleasurable or ‘good’. As strands of practice, they

Integrating semi-structured somatic … 239

JDSP_1.2_art_Weber_237-254.indd 239 5/11/10 6:11:12 PM

5. In codified tech- are differentiated from the more ‘codified’ somatic modalities (to borrow

niques, less autonomy

in movement

phrasing from Enghauser 2007: 34), sometimes referred to as ‘structural

response lies with integrity techniques’ (Williamson 2010b),5 which have been presented in

the student than previous research.

in semi-structured

techniques, but more

Previous work in the field has illustrated that these more codified tech-

so than in structural niques ‘create dancers who can move easily in many different styles’ and

integrity techniques; ‘strengthen technical capacity, expand expressiveness, and reduce inci-

these typically come

from some pattern

dents of injury’; however, it remains to be seen whether some of the same

of work, but stu- results may be expected when working within more open somatic frame-

dents still have some works (Berardi 2007: 23; Eddy 2009: 21). As a dancer, educator and

autonomy in shaping

those exercises – an

practitioner working within the semi-structured or open framework

example might be strands of practice, I am interested in the integration of these particular

Continuum. Strands somatic movement dance techniques within the greater dance education

of practice referred

to as ‘structural

field. How can dance educators incorporate the addition of less codified

integrity techniques’ somatic techniques? How does the incorporation of semi-structured

are highly codified, somatic work within their contemporary technique classes affect dancers

and usually based

on an external idea

of varying levels of experience? Using the previous research with other

of anatomy (but still somatic techniques as a well-established ground for forming my research,

maintaining a focus I sought to undertake a short piece of action research that could begin to

on the felt sensation

of that anatomy) and

address these questions. The research, conducted within a first-year college

have set exercises to dance programme, introduced semi-structured somatic explorations within

develop correct ana- the context of a contemporary dance technique class and examined the

tomical alignment; an

example of this type of

results through students’ responses to a series of open discussions, journal

work might be Body- entries and questionnaires.

Mind Centering or Because of the growing popularity of incorporating somatics into dance

Alexander Technique.

education programmes, it is important to research thoroughly the links

between these two disciplines and confirm as many connections between

somatics and dance education as possible – and to establish varying meth-

ods of incorporating somatics into traditional dance training so that they

may be adapted to instructor experience, student body, course content or loca-

tion and/or practitioner and educator availability accordingly. Continuing

research which links somatic pedagogies to dance education is paramount

because, as Enghauser (2007: 33) deftly points out, ‘The structure of a

traditional dance class does not currently offer sufficient opportunities for

students to develop a sensitized relationship with their body.’ Additionally,

characteristics shared by all somatic pedagogies – such as the balance

between rest and activity, which has shown ‘to be more beneficial to

acquisition and retention of motor skills, and to decreased rates of injury,

than continuous (“massed”) practice’ found in typical dance training –

can be incorporated into dance technique classes regardless of whether

the practice in which educators are experienced is codified or open (Batson

and Schwartz 2007: 47).

Conducting research such as this, in a similar vein as prior published

studies provides validation of those findings by replication of data and

findings. Furthermore, research regarding the intersection between dance

education and somatic movement dance education is needed to reinforce

the importance to the dance community of the embodied consciousness

somatics engenders so that these resources may become more readily

available within higher education dance programmes. Too often, dancers

are stuck within learned (mimicked) movement patterns which are

240 Rebecca Weber

JDSP_1.2_art_Weber_237-254.indd 240 5/13/10 11:15:55 AM

unnatural, detrimental to their bodies or inefficient and have no way of

altering these set patterns. Body therapies, whether codified or open, offer

methods for dancers to become more aware, more embodied and provide

avenues for positive change towards well-being in movement. As Glenna

Batson highlights, the repetition in traditional dance classes without the

addition of somatic inquiry does not allow for positive, integrated change:

An integrated change must evolve from sensing the body in a new, more

efficient way. The body therapies help us distinguish the old, dysfunctional

movement habit from the new, through a new sensory experience. Repeated

new experiences also inhibit the old pattern, clarify and reinforce the new

pattern, and create an integrated change.

(Batson 1990: 30)

The importance of continued research on how dance intersects with vari-

ous fields, including somatics (Minton 2000), is evident. With regards to

the relation between dance and somatics, it is particularly important to

relate to the greater dance community how to disseminate various somatic

practices within the context of the dance technique class if dance as a field

is to advance and welcome somatics as an integral aspect of dance educa-

tion. As Fortin, Long and Lord (2002: 176) contend, ‘if any type of

research is to impact upon the lived experience of dance teachers, it will

most likely be personal accounts of other teachers’. Another goal within

my research was to investigate not only the effect of incorporating another

strand of somatic practice, but also how to incorporate it into a contempo-

rary technique class – with the goal of being able to convey that informa-

tion for other teachers interested in incorporating these ideas into their

classes; as such, this piece of research was done with a twofold aim: both

to enhance my personal teaching practice and to relay that information to

interested educators, offering what has been referred to in dance educa-

tion academia as ‘both local and public knowledge’ (Cochran-Smith and

Lyttle 1993, as cited in Fortin, Long and Lord 2002: 176).

Action research

Methodology

Part 1: Paradigm, sample and methods

Sharing a post-positivist frame of study with Jill Green (1999), this quali-

tative research was conducted as a post-positivist, naturalistic study within

a paradigm of hermeneutics and phenomenology as a framework for offer-

ing the subjective observations of the researcher. My work is an example

of action research – conducted by practitioners in the field and seeking to

bring about change, a form of reflective practice-as-research – as I was

working both as an educator (guest lecturer) and researcher in a simulta-

neous ‘double hermeneutic’ spiral whereby the work being done was both

shaped by myself (as educator/researcher) and by the students I was

teaching (Trimingham 2002).

The research was conducted as part of the Performing Arts (Dance)

National Diploma programme at Warrington Collegiate, on which I served

as a guest lecturer during the first half-term for the Year 1 students, who

comprised my research sampling. Eight students were enrolled in the class,

Integrating semi-structured somatic … 241

JDSP_1.2_art_Weber_237-254.indd 241 5/11/10 6:11:12 PM

6. The 37-year-old seven of whom regularly attended the sessions and who comprise the

female was an outlier

in the sample; other

research sampling – a ‘small sample characteristic of qualitative research

participants ranged studies […] from which to begin to generate theory regarding dance in

from 16 to 19 years higher education’ (Green 1999: 83). The sample group consisted of five

of age.

females and two males, ranging in age from 16 to 376 whose backgrounds

7. Again, here the in formal dance training ranged from no prior training to thirteen years of

37-year-old female

was an outlier, as she

classes. Styles studied previously (and concurrently) by students included

had some exposure ballet, tap, jazz, contemporary, African, salsa, street/urban dance, and

to Five Rhythms and belly dancing. Students varied in body type, racial background and techni-

Eurythmy/Steiner

work.

cal ability. All but one of the participants had no prior experience with

any of the somatic disciplines.7 Both myself as guest lecturer and their

8. As such, students regular technique lecturer were present in all six sessions, which were

also signed consent

and disclaimer forms given during their regularly scheduled contemporary technique classes.

regarding the use The sessions were presented to students as a module on somatics and stu-

of touch, release of dents were aware that they were participating in a research study.8

information, con-

fidentiality within I implemented methodical triangulation through multiple data sources

and outside of the and collection methods, which included video and audio recording of ses-

group, and video/ sions, transcription of group discussion (open interview) feedback and par-

image release forms

that conformed to ticipant observation by both myself and the usual course tutor. Reliability

ISMETA and UCLan of findings were cross-checked between multiple data sources. Validity

standards. Students was supported by these methods, as well as thick description, reflexivity,

were required to

participate in the the search for disconfirming evidence and peer debriefing – methods that

module as a part of are well established within the qualitative research paradigm (Gilchrist

their course, but were and Williams 1999; Cooper, Brandon and Lindberg 1997).

given the option to

decline participation Potential drawbacks complicating the data collected include the fol-

in the research; how- lowing: my own experience and research in application of somatics to

ever, each student dance education coloured my understanding of information received;

volunteered and con-

sented to the use of additionally, I was serving both as a researcher and as a teacher, so par-

their work within the ticipant observation was limited during teaching demonstration periods;

research context. furthermore, students were instructed that the journals, some observation

9. The assessment of and written interview responses were to be part of their course assessment,9

these journal, discus- and this may have coloured their response. However, it is my opinion as

sion and response

questions was based researcher, which is validated by peer debriefing and small-scale informal

on participation and member checks (whereby I fed back information to get confirmation that I

effort rather than had understood responses correctly during group discussions with stu-

the ‘correctness’ of

responses – another dents), that the responses received were reliable.

aspect that strength-

ens the validity of Part 2: Class structure

the data received.

Students were aware The structure of the classes I taught ranged from strictly somatics to a

that they could shifting balance between somatics and technique exercises, through a

withdraw from the melding of the two, to a session devoted completely to technique. The

research but still

participate in class focus on the somatic sessions was on accessing various fluid systems of the

activities, without body, and the inherent movement qualities within those systems, as rec-

worrying about the ognized and outlined within the somatics community (Hartley 1995;

affect on their grades

in the course. Williamson 2009; Tufnell 2008; Abrams 2008).10 Classes began with a

period of sensing within the body, to exercise kinaesthetic awareness and

10. The importance of

the fluid nature of a because, as Batson (1990: 28) notes, ‘sensing (and paying attention to

mover’s body is also our sensing) is not merely one component that precedes motor output but

emphasized in Emilie is, in fact, essential to organizing our nervous system, our thinking, and

Conrad’s Life on Land;

thus our movement outcome’. Thus, classes always began with a restful,

242 Rebecca Weber

JDSP_1.2_art_Weber_237-254.indd 242 5/11/10 6:11:12 PM

meditative sensing period of self-care – to balance the levels of rest and however, the fluid

nature is presented

activity, to awaken kinaesthetic, proprioceptive and interoceptive aware- on a more holistic

ness, and to tune into sensing as a method of restructuring movement level and less broken

outcomes. Semi-structured Connections to the Living Body movement down into catego-

ries of types of fluid

explorations drew on Continuum, Body-Mind Centering and Authentic and their associated

Movement for inspiration.11 Classes took the following format: movement styles/

patterning (Conrad

2007).

• Class 1: Intro to somatics – Students were introduced via a brief lecture

and handout on somatics as a field and the primary tenets within the 11. It is important

to note here the

Connections to the Living Body framework in which I am trained. difference between

Students then entered into a period of semi-structured somatic explora- inspiration and

tion set up as a community session to introduce them to somatic prac- appropriation; the

exercises were

tices. The focus was on balancing rest and activity; establishing a sense of developed with

non-judgement; kinaesthetic, interoceptive and proprioceptive sensations; general ideas in

and methods of learning (improvisation) and harvesting bodily knowl- mind as a basis

for informing

edge (writing/drawing, conversing in dyads and group discussion). practice – never

• Class 2: Fluid systems: cerebrospinal (CSF) – This class was mainly were specific tech-

comprised of periods of somatic awareness and sensing explorations, niques, exercises or

structures used, nor

wherein students were introduced to the concept of fluid systems, and, were the exercises

focusing on CSF, were invited to explore the associated movement presented

qualities, namely the heaven/earth connection, gentle movement from to students as

belonging to another

the centre outwards (initiation from spinal flow), timeless flow, suspen- body of work. For

sion in time and space, meditative stillness and rest – in other words, further clarification

the ‘lightness, balanced suspension in space, sensitivity, and timeless on this as a

framework in

flow that are characteristic of the “mind” or awareness of the CSF’ which to practise,

(Hartley 1995: 283). Students were also introduced to the aspect of consider the

touch work to bring and guide awareness with partners in the somatic following: ‘As

noted by Elin Lobel

explorations. and Julie Brodie,

• Class 3: Fluid systems: synovial – This class grew from somatic move- there is a distinction

ment explorations to include improvisations and a few more short tech- between somatic

techniques and key

nique exercises with a focus on moving from the synovial fluid system. principles which

Qualities associated with synovial fluid included a loose, arrhythmic, orientate practice

jiggling; releasing the rigidity of bones and muscular tension; light, (2006: 70). These

authors use Don

carefree flow and laughter; and the softening or gliding (support and Hanlon-Johnson’s

cushioning) quality found in the lubrication of the joints and shock distinction between

absorption (Williamson 2009d; Hartley 1995). actual techniques

and general guid-

• Class 4: Fluid systems: lymph – This class began with somatic move- ing principles which

ment explorations and improvisations with a focus on moving from philosophically shape

the lymph fluid system to include several more technique exercises. somatic techniques.

For example,

Qualities associated with lymph fluid emphasized moving at a slower, “principles are

sustained rate with clarity of direction and clear bodily and personal fundamental sources

presence (Williamson 2009d). Qualities of precision, directness, inci- of discovery that

enable the inspired

siveness, and personal empowerment were emphasized (Hartley 1995). person continually

• Class 5: Fluid systems: blood – This class focused on movement explora- to invent creative

tions and combinations after a brief active awareness exercise. Somatic strategies for

working with others,

movement, improvisations and combinations focused on the contrac- where as techniques

tion and release, movement and stillness, rest and activity, and puls- are specific methods

ing action associated with blood (Williamson 2009d; Hartley 1995). arising from such

principles.” (Johnson)’

Students were encouraged to explore the variation in quality from (Williamson

arterial (outward from heart, energized, weighted, pushing action; (2010a: 7).

Integrating semi-structured somatic … 243

JDSP_1.2_art_Weber_237-254.indd 243 5/11/10 6:11:13 PM

12. For a more thorough spontaneous interaction with environment/each other) to veinous

description of each

phase, including

(returning to centre, slower, long rhythms, rising and falling momen-

details important to tum, self-nurturing) flows (Williamson 2009d; Hartley 1995) as well

the structuring of as the differentiation between heart beat (active, pulsing, pumping)

my sessions (such as

subjective experience

and blood beat (stillness, suspension, moments of rest – drawing from

in warm-up, etc.), see a brief pause within a cell between arterial and veinous flows) (Tufnell

Eddy (2006). 2008; Hartley 1995).

• Class 6: Contemporary technique – Students were given a contemporary

technique class directed at allowing them to autonomously integrate

principles from the previous sessions on fluid systems, and to find rest-

ful periods in class, consider initiation points and fluid qualities within

given exercises. Many of the exercises given during previous sessions

were utilized to provide a point of reference for students and allow them

to concentrate less on the combination and more on the movement

quality – according to Lord, ‘the dance sequence […] once memorized

became a context for offering students opportunities to take ownership

of learning and to acquire movement execution procedures’ (Fortin,

Long and Lord 2002: 163). Students were then given one longer fin-

ishing combination and asked explicitly to dance the movement with

a focus on each fluid system in turn to discover through their inner

sensing how the movement felt and changed.

Classes were structured so that the focus shifted gradually throughout

the module from somatics to technique – i.e. the first and last classes

were dedicated to a singular focus (somatics and technique, respectively),

and the classes in-between had a sliding scale of both foci to gradually

transition from one to the other. For the classes incorporating both

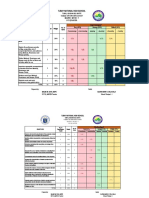

somatics and contemporary technique, I used the model put forth by

Martha Eddy (2006, Figure 1), and structured the time dedicated to each

phase accordingly with where the class fell on the progression through

the sessions.12

Martha Eddy’s body-mind dancing’s six phases

Phase I Information about anatomy, kinesiology and physiology

Phase II Warm-up

Phase III Floor exercises (includes partner work for kinaesthetic and tactile learning aides)

Phase IV Centre floor and across the floor full-out moving

Further synthesis of anatomical information into dance (long dance sequence, solo or

Phase V

group improvisation structure)

Cool-down and stretch-out inclusive of non-verbal and verbal sharing about the experi-

Phase VI

ence that day with time for questions and comments

Figure 1.

244 Rebecca Weber

JDSP_1.2_art_Weber_237-254.indd 244 5/11/10 6:11:13 PM

The reasons for structuring the module thus are manifold. First, because the 13. Drawing heavily on

phenomenology and

group included inexperienced dancers (both in somatics and in dance train- phenomenological

ing in general), it was important to introduce the concept of inner sensing existentialism –

and somatic pedagogical concepts gradually – the students needed one entire placing value on

subjective experience

class dedicated to understanding the important philosophical13 and political14 and internal knowl-

underpinnings to serve as a basis from which to work.15 Additionally, the edge. For a good

focus on fluid systems was purposefully selected, as I felt it was an area of overview of this basis

in dance education,

somatics that is easy to access, understand, and connect with on a physical please see Fraleigh

and psychological level for inexperienced students just beginning to cultivate (1979).

internal awareness – as Mary Abrams writes, ‘Fluidity heightens movements 14. Themes such as

in our organism that increase communication with our internal and external non-judgement

environments’ (Abrams 2007). Research findings also extensively highlight (of self and others)

and reclaiming the

the benefits of a fluid focus for dancers and movers in creating change; meth- body, reconnect-

ods of change such as this are clearly necessary if one intends to grow ones’ ing the body and

(or ones’ students’) dance practice: Linda Hartley (1995: 268–70) notes, mind, etc. are cen-

tral to Connections

to the Living Body

The body fluids are the systems through which communication with, and (Williamson 2009a,

transformation of, both inner and outer environments takes place. […] The 2009b) work in

which I am versed,

fluids concern the balance of rest and activity, self-nurturing, nurturing of oth-

and to the field of

ers, play, laughter, the setting of boundaries and limits in self-defense, active somatics as a whole.

and receptive communication, rhythm, movement, and meditative stillness.

15. Although the themes

[…] Our aim in working directly with the fluids is to bring each one in turn up were presented to

into conscious expression so that all of their qualities are available; and most students as important

importantly, to work with the easy transitioning from one to another, for it is central concepts, they

were neither empha-

in the ability to make transitions that many of us become blocked … sized as philosophical

nor political due to

In addition to the deliberate choice of investigating fluid systems, students many of the students’

ages, education

were also encouraged to explore movement and sensing with eyes closed, level and maturity

as it ‘facilitates deep sensing experience’ particularly during Phases I, II, level; also the terms

VI and sometimes III; this is a primary tenet within my Connections to ‘philosophical’ and

‘political’ were not

the Living Body training, developed from Authentic Movement and also used because of the

encouraged in many somatic practices – and these lessons – as it engen- risk of polarization

ders embodiment with an internal focus (Stromsted and Haze 2006: 58). with such a brief tast-

ing in the overview of

Students ‘work[ed] with eyes closed in order to expand [their] experience the work.

of listening to the deeper levels of kinesthetic reality’ (Lowell 2006: 52).

16. Some of these meth-

Students also ‘turned on’ their kinaesthetic awareness during Phases I, odologies included

II and III through various techniques designed to connect them to the directing students’

qualities of the intended fluid. Methods used included those outlined by attention to their

sensation of move-

Hartley to access fluid systems, including ‘first studying the anatomy and ment and shaping

physiology of the system, understanding the directions and rhythms of the procedural knowl-

flow, its functions, and the qualities of movement which these suggest’, edge through tactile

feedback, repetition,

and ‘visualizing and sensing, […] a combination of active imagination, exploring changes in

touch, movement, and focused breathing’ and also through a ‘more active, feel of moving from

feeling approach by moving with the qualities, rhythms, and dynamics different initiations,

highlighting different

associated with the specific fluids or dancing to music that will stimulate ways to achieve a

such qualities’ (Hartley 1995: 271–72). task, describing move-

ment somatically and

using ‘verbal, visual

Teaching goals and sensory cues

The goals I hoped to reach as I developed my teaching practice drew to assist learners to

from my somatic practice, educational background and previous research construct meaning

Integrating semi-structured somatic … 245

JDSP_1.2_art_Weber_237-254.indd 245 5/11/10 6:11:13 PM

from their past and findings. By offering tools for students to become more attuned to their

present kinaesthetic

experience’ (Fortin,

inner sensations and reconnect with an embodiment which bridges the

Long and Lord 2002: mind/body dualism, I hoped to reach several other goals. My teaching

169–70); thinking of goals were to balance the mind and body, rest and activity, and thinking

whole movement and

imagining a move-

and doing (Halprin 2003; Batson 2009; Batson and Schwartz 2007;

ment goal (Batson Berardi 2007). Through exploring movement through various fluid sys-

1990); kinaesthetic tems, I offered tools for ‘accessing multi-system support to balance the

listening (Enghauser

2007) and learn-

muscular system and [for] relieving it from overdrive’ and by using imagery

ing (Eddy 2006); (ideokinetic facilitation) in describing movement improvisations or combi-

and communication nations, I wanted to ‘facilitate efficiency in pedestrian and in dance move-

strategies (use of met-

aphor, visualization

ment’ (Batson and Schwartz 2007). I encouraged students to ‘[shift] the

and active participa- focus from product (skill acquisition) to process (what is actually happen-

tion) (Fortin 1995). ing in the body)’ to facilitate an embodied consciousness and the integra-

17. Qualitative data tion of perception and action in class (Brodie and Lobel 2004: 80). During

analysis procedures the process, I found myself naturally including some of the same teaching

followed those set

out by Miles and

methods as instructors versed in ‘codified’ somatic modalities had demon-

Huberman (1994: strated in earlier research16 (particularly Batson 1990; Fortin, Long and

9) – a series of Lord 2002; Long 2002; Eddy 2006; and Enghauser 2007; but also Brodie

‘analytic practices’

which included the

and Lobel 2004; Batson 2007; and Batson and Schwartz 2007).

following: coding

data; reflecting on Results

data; sorting data;

identifying patterns in

Several themes emerged through the process of data analysis.17 Recurrent

data; moving towards themes that occurred in verbal and written feedback as well as in observa-

generalizations; and tion included connection within/to the body, confidence, enjoyment and

developing theories/

conceptualizing.

relaxation, creativity, implications for the development of dance technique

skills and the development of critical understanding. These themes were

documented within most of the sample population. For this section, I

would like to address some of these findings through excerpts provided

from student feedback. Feedback presented within this article as comments

were gathered from a mix of questionnaires, journal responses and verbal

responses given in open discussion sections of the classes. All quotations

presented here were from a range of responses from each of the seven stu-

dents and are presented anonymously, as was agreed upon in release

forms the students signed prior to participation in the research; this ena-

bled them to respond freely and without worrying about the repercussions

of identification.

Bodily connection – Students were observed demonstrating clear develop-

ment of embodied practice and declared in verbal and written responses

that they felt connected to their own bodies. Their understanding of the

movement qualities associated with each fluid system was fully demon-

strated within their movement explorations and was confirmed through

the students’ corresponding journal writing and response to open-ended

interview questions asking them to name the movement qualities they

associated with each fluid system – i.e. each student’s identified quality

was displayed physically as well as verbally and/or in writing; further-

more, these qualities reflected a general understanding of the qualities of

fluid identified by somatics scholars such as Linda Hartley (1995).

Examples included ‘a combination [of] jiggly-wiggly & smooth movement’

for synovial fluid and ‘precise and clear’ for lymph (questionnaire),

246 Rebecca Weber

JDSP_1.2_art_Weber_237-254.indd 246 5/24/10 9:30:12 AM

‘rhythmic contraction of vessel walls…rhythmical and continuous’ with

lymph fluid (questionnaire), ‘earthy dancing with strong heart pulsation’

with blood (journal).

Additionally, students developed an awareness of connections within

and throughout the body beyond the fluid movement qualities, as evi-

denced in writing responses: students expressed feeling ‘connected within’

(questionnaire) and ‘inside myself’ (questionnaire). One student noted, ‘…

every move I make are [sic] all connected to every body part such as [how]

a ripple starts from the head and goes through the whole body’ (journal),

and in group discussion, ‘it’s helped me quite a bit to understand how the

body moves and how it works’; another student echoed this reflection in a

group discussion, ‘I could feel and see the difference, as well as doing it …

not only was I putting more into it, but I could feel the different parts of

the body moving.’

Creativity – Students expressed feeling a greater sense of creativity within

their movement vocabulary, both in verbal and written communication;

furthermore, the changing of old movement patterns and creation of new

ones were observed during movement explorations – one student stated

explicitly ‘i [sic] can feel myself doing more things’ (questionnaire) and

one referred to ‘how you can recreate a technique’ (questionnaire). The

sense that embodied consciousness led to greater freedom and range of

movement, movement styles and movement qualities was explicit in

nearly all student feedback; often the creative flow was attributed to a

deeper connection with lived body experiences and emotions and was con-

nected with a sense of personalized movement or personal connection.

Responses included:

• ‘I can move cathartically, dancing out my feelings, dancing through

my feelings, using my dance to explore my feelings & reach new lev-

els of insight. […] My body can curve & roll, bend & sway, leap &

lunge, revealing the different aspects, moods, & phases of my life. […]

I will take away a sense of “me” & who I am in my body’ (journal

responses).

• One student reported discovering ways of ‘being inside myself and my

own movement’ (emphasis mine), and stated, ‘I feel like I learnt [sic]

about myself and my style when I dance’ (questionnaire).

Additionally, the increase in creative responses was noted by the students’

instructor in other classes, as she emphasized, ‘it affects their creative

work as well; I know for a fact they’re thinking more about it rather than

just “doing”. They’re connecting to the movement, and there’s a purpose

to it’ (Nelson 2009).

Confidence – An unexpected result was how incorporating somaticization

in the technique class affected students’ levels of confidence. That the stu-

dents’ confidence levels were boosted was reiterated many times in open

discussion groups, and was reflected in their written responses to ques-

tionnaires and their journal entries. Additionally, the skyrocketing of con-

fidence levels was a major part of observational feedback from the students’

Integrating semi-structured somatic … 247

JDSP_1.2_art_Weber_237-254.indd 247 5/11/10 6:11:13 PM

primary instructor, who insisted that the benefit spilled over into other

coursework and classes (Nelson 2009). Both she and the students attrib-

uted the rise in confidence level (where attribution was attempted) to the

sense of non-judgement that underlies somatic work:

• ‘Hitting this sense of non-judgement where they first come in, I’ve noticed

that their sense of confidence has really grown. Simple things, like [two

students previously] found it hard to move because they felt like they

were being judged, but […] I think it’s great when it comes in that early,

when the students are getting to know each other’ (Nelson 2009).

• One student noted, ‘… it’s helped… me confidence-wise, that sense of

release and not being judged and all. it’s quite intimidating in the room,

when it’s all dark and we’re doing choreography – but when we’re

in the somatics lessons and you’ve got a witness and you’re moving

unconsciously and not worrying about how it looks, you can make new

movement […] and play with it without feeling like you look like an

idiot’ (discussion).

Critical understanding of underlying tenets – The fact that students read-

ily attributed the boost in confidence to the non-judgemental nature of

somatic work illustrates how the underlying principles have begun to take

root in the dancers’ consciousness. ‘It’s clarified their interpretive skills; it’s

made them more aware,’ reflected Nelson. Though the philosophical and

political tenets underlying the somatic work were not emphasized or made

explicit, several students displayed a subtle understanding of these princi-

ples. Some excerpts which highlight these implicit understandings follow:

• ‘[the somatic explorations] made me actually think more about what I

was doing and how it affected the group’ (questionnaire).

• In discussions and in journaling, a student reiterated a new-found

importance of non-judgement to her dancing and her dance training

both within and outside of the college setting.

• After touching on her original discomfort at being watched, a student

echoed the importance of non-judgement in transforming her practice

as she responded, ‘I think [through the somatics] I started to be more

positive and have more appreciation in the sessions’ (questionnaire).

The students’ subtle understanding of the political underpinnings of valuing

personal experience and non-judgement (of self and others) allowed the

group as a whole to find more connection, greater support and a sense of

community within one another. This was reflected in my own and their

instructor’s observation, as well as within the students’ writing. One stu-

dent responded in their journal to the initial session, saying, ‘I liked it

because we bonded with each other.’ Instructor reflections confirmed this

sense: ‘The somatics exercises are great for getting to build a sense of

community. The touch aspect really builds a lot of confidence and intimacy

within the group – it breaks down boundaries’ (Nelson 2009).

Technical implications – In addition to the above, some data suggested

that the students’ somatic experiences had implications for their technique

248 Rebecca Weber

JDSP_1.2_art_Weber_237-254.indd 248 5/24/10 9:29:55 AM

training and performance skills. Because the dancers were not highly 18. Here, the students’

negative responses

experienced to begin with, it was difficult to discern a great level of to research question-

technical advancement within the short period of time of module delivery; naires would seem to

however, student responses point towards technical development. It is further support the

validity of the results;

possible that the advancement was apparent to students perceptually or meaning students

conceptually before it could be demonstrated physically. Further research responded honestly –

will be needed to confirm the advances – they are merely one additional even when their

answers would seem

hypothesis that arose from the data set available. Students reported sens- to be in contradiction

ing advancements within their own dance practice: to the researcher’s

goals – rather than

attempting to provide

• ‘It affected my movements and they’ve become clearer’ (questionnaire, a ‘correct’ or ‘desired’

in response to whether somatic explorations affected movement in dance answer.

technique exercises or classes).

• ‘[Somatics] made me see how actions can have different qualities

and […] different ways of interpreting a movement and how you can

execute them [sic]’ (questionnaire).

• ‘I’ve learned how to breath [sic] while dancing’ (discussion).

• ‘[In a typical technique class, students] don’t get time to focus on

the dynamics and the quality, and it’s all about rushing around and

getting to the next level, but that’s what defines and communicates

movement, those small details. I think [somatic training] is important

because it helps them to focus, and at that moment of getting more

connected, you get more out of them. And you’ve got to slow down [to

body temporality] to get connected’ (Nelson 2009).

Outliers

It is important to address outliers in any qualitative research, and some

responses were inconsistent with other findings. There were only a couple

of outlying responses indicating that students did not find benefit from the

inclusion of somatic practices in their contemporary technique classes.18

These two responses (given to the same question) were contradicted by

the same students’ other responses (in discussions, journal entries and on

the questionnaire) as well as through the observations of myself as

researcher and their dance technique teacher, and thus it can be assumed

that the problem lay in a misunderstanding (validity) of the wording of

that particular question, and not in the findings of the study as a whole –

i.e. students misinterpreted the meaning of the question asked, rather than

that they did not find the somatic explorations beneficial to their personal

dance practice.

Other implications within teaching practice

Concerns arose in many of the students’ responses, particularly during

and after the first few sessions, that a feeling of discomfort or dis-ease with

the work was evident. Students reported that in response to the initial

introduction to the work, they ‘felt stupid’, ‘felt uneasy’, and that their

‘body felt strange’ (journal); that ‘at first I didn’t understand’ (question-

naire); and ‘at first I thought the workshops were strange and didn’t really

know what to expect’ (questionnaire). However, these concerns were

reported to be relieved throughout the process, as students became more

familiar with their own bodies and with the semi-structured somatic

Integrating semi-structured somatic … 249

JDSP_1.2_art_Weber_237-254.indd 249 5/11/10 6:11:14 PM

19. Here, I feel it would practices. One student aptly summarizes the group’s transition as she

be helpful to outline

the tools that I found

reflected in a questionnaire and the following journal writings about the

especially useful in shift from discomfort to comfort:

supporting students

who were navigating

‘Initially the sessions felt artificial because I wasn’t relaxed, partly due to

this foreign territory.

These were as follows: feeling self-conscious about being watched during the sessions. I also felt as

providing a good though I had to make certain movements because it was expected of me. […]

framework or context

The exercises also were disorienting and made me feel a bit dizzy, I think this

of understanding the

somatic work prior was due to having my eyes closed for such a long time.

to practical work; However, as I started to understand the different aspects of somatics and

entering into the

we looked at the different fluid systems, it started to make more sense and I

somatic work very

gradually within the could see and feel the links between the dance, the music and my body.’

context of a lesson or

curriculum; offering

extensive examples –

This excerpt reflects how practices of embodiment and kinaesthetic

i.e. physically awareness can be very foreign and ‘disorienting’ to those who are not

demonstrating my used to them, particularly less technically experienced dancers. As movers

experience with the

exercises presented

gain more experience and kinaesthetic awareness through the somatic

to students, verbally practices, they take more responsibility and enjoyment in the re-pattern-

encouraging students ing of their own movement. As Nelson (2009) notes,

to follow and respect

their own movement

impulses, both during ‘For us [as more experienced movers], it’s quite a simple sort of process,

the work and after- but for them those simple processes can be terrifying. I really picked up on

wards in discussion,

how they really thought about what they were doing. What I found was

and acknowledging

that there is a how it made them focus more internally rather than externally – less on

transition period – what it looks like, if it’s pretty, it should be like this […] it really made them

i.e. helping students

look at movement in a different way than just glamorous or show-based

to not feel ‘alone’ in

the difficult or dancing.’

dis-comfortable

transition period.

In this, she echoes Don Hanlon-Johnson’s perspective on bodily authority,

in which he maintains that people have been systematically alienated from

their own personal autonomy and have become dependent on experts,

stating that ‘the fundamental shift from alienation to authenticity is

deceptively simple: it requires diverting our awareness from the opinions of

those outside us toward our own perceptions and feelings’ (Johnson 1983:

154). It is important to note that this recovery is deceptively simple, and to

allow for a gradual enough process – both within the construct of each

individual lesson (gently entering into body temporality) and within the

curriculum development (creating modules long enough to engage in this

recovery gradually over several classes in a long period). This is particu-

larly important when working with the less codified strands of somatic

work, as in the open or semi-structured frameworks, where more auton-

omy lies with the students; these teachers need to be especially aware of

the support that students – particularly those inexperienced with somatics

or dance in general – require in structuring workshops and introducing the

somatic work.19 Ideally, teachers implementing any sort of somatics into

their dance technique education will plan ways of navigating this difficult

transitional period, and explicitly address these insecurities and unfamiliar-

ity to students more clearly at the onset of the module. Additionally, enough

time is necessary to allow the seeds of political and philosophical underpin-

nings, as well as the small development of technique-based implications, to

250 Rebecca Weber

JDSP_1.2_art_Weber_237-254.indd 250 5/11/10 6:11:14 PM

root and take place to fully inform students’ dancing. This will allow them 20. For evidence and

discussion of this, see

the autonomy to apply these principles beyond the confines of the particu- examples, such as

lar class or module that explicitly incorporates somatic awareness. the ‘myth of the ideal

body’ (Green 1999)

and inherent power

Conclusion structures/lack of

It is apparent from prior research in this field that including somatic prac- autonomy, in Green

tices within the context of a dance technique class allows students more (1999) and Johnson

(1986).

tools from which to build a healthy, embodied practice. Within the context

of this study, semi-structured somatic pedagogy appears to mirror structur-

al-integrity technique modalities in application within the technique class

setting and to address many similar areas in dance training and education.

Dancers who were exposed to the semi-structured framework replicated

many of the traits exhibited by previous research into the intersection

between somatics and dance training: students became more aware and

embodied; felt empowered and enjoyed a greater sense of well-being

throughout their dancing; appreciated tools for movement initiation; exhib-

ited new variety in movement quality and patterns; and discovered greater

creativity and autonomy within their dance practice. Inclusion of somatics

engenders a greater sense of critical understanding, allowing dancers to

call into question and subvert traditional, harmful patterns of movement as

well as behaviour.20 These qualities are all manifested, not only in the stu-

dents’ responses during this research, but should be present in any work

which combines somatic work and dance technique in the ethos and

underpinnings guiding the teaching of dance technique classes – it is truly

a co-creative act between teacher and pupils that fosters the embodied con-

sciousness which allows these benefits to emerge. As Sylvie Fortin notes,

the rejection of external control of the body and a set movement aesthetic are

tenets that have contributed to the coming of modern dance. These tenets

continue to shape the development of new dance. A similar stance has never

really found its counterpart in the realm of dance teaching

(Fortin 1995: 12–13)

– perhaps somatics, whether as ‘codified’ or ‘open’ frameworks, can

provide one answer to move the field of dance education forward.

References

Abrams, M. (2007), ‘Continuum Movement: Fluid New Meanings for Health

& Life’, available from http://www.ismeta.org/downloads.html. Accessed

18 March 2010.

—— (2008), Practice observation in teaching practice with MA students,

University of Central Lancashire, 14–17 November.

Arnold, P. (2005), ‘Somaesthetics, Education, and the Art of Dance’, Journal of

Aesthetic Education, 39: 1, pp. 48–56.

Batson, G. (1990), ‘Dancing Fully, Safely, and Expressively: The Role of the Body

Therapies in Dance Training’, Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance,

61: 9, pp. 28–31.

—— (2007), ‘Revisiting Overuse Injuries in Dance in View of Motor Learning and

Somatic Models of Distributed Practice’, Journal of Dance Medicine and Science,

11: 3, pp. 70–75.

Integrating semi-structured somatic … 251

JDSP_1.2_art_Weber_237-254.indd 251 5/11/10 6:11:14 PM

—— (2009), ‘Somatic Studies and Dance’, International Association for

Dance Medicine and Science Resource Paper, available from http://

www.iadms.org/displaycommon.cfm?an=1&subarticlenbr=248. Accessed

18 March 2010.

Batson, G. and Schwartz, R. (2007), ‘Revisiting the Value of Somatic Education in

Dance Training Through an Inquiry into Practice Schedules’, Journal of Dance

Education, 7: 2, pp. 47–56.

Bauer, S. (1999), ‘Somatic Movement Education: A Body-Mind Approach

to Movement Education for Adolescents’, Somatics, Spring/Summer,

pp. 38–43.

Berardi, G. (2007), ‘Mind Matters: Somatics is a Growing Trend in Dance Training’,

Dance Magazine, May, pp. 22–24.

Brodie, J. and Lobel, E. (2004), ‘Integrating Fundamental Principles Underlying

Somatic Practices into the Dance Technique Class’, Journal of Dance Education,

4: 3, pp. 80–87.

Brown, J. (2005), ‘Evaluating surveys of transparent governance’, in UNDESA

(United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs), 6th Global Forum on

Reinventing Government: Towards Participatory and Transparent Governance, Seoul,

Republic of Korea, 24–27 May, United Nations: New York.

Conrad, E. (2007), Life on Land: The Story of Continuum, Berkeley, CA: North

Atlantic Books.

Cooper, J., Brandon, P. and Lindberg, M. (1997), ‘Using Peer Debriefing in the

Final Stage of Evaluation with Implications for Qualitative Research: Three

Impressionist Tales’, paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American

Educational Research Association, 24–28 March, Chicago, Illinois.

Debenham, P. and Debenham, K. (2008), ‘Experiencing the Sacred in Dance

Education: Wonder, Compassion, Wisdom, and Wholeness in the Classroom’,

Journal of Dance Education, 8: 2, pp. 44–55.

Eddy, M (2006), ‘The Practical Application of Body-Mind Centering® (BMC) in

Dance Pedagogy’, Journal of Dance Education, 6: 3, pp. 86–91.

—— (2007), ‘A Balanced Brain Equals a Balanced Person: Somatic Education’,

SPINS Newszine, 3: 1, pp. 7–8.

—— (2009), ‘A Brief History of Somatic Practices and Dance: Historical

Development of the Field of Somatic Education and its Relationship to Dance’,

Journal of Dance and Somatic Practices, 1: 1, pp. 5–27.

Enghauser, R. (2007), ‘Developing Listening Bodies in the Dance Technique

Class’, Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance, 78: 6, pp. 33–54.

Fortin, S. (1995), ‘Toward a New Generation: Somatic Dance Education in

Academia’, Impulse: The International Journal for Dance Science, Medicine, and

Education, 3, pp. 253–62.

Fortin, S., Long, W. and Lord, M. (2002), ‘Three Voices: Researching How Somatic

Education Informs Contemporary Dance Technique Classes’, Research in Dance

Education, 3: 2, pp. 155–80.

Fortin, S. and Siedentop, D. (1995), ‘The Interplay of Knowledge and Practice in

Dance Teaching: What We Can Learn from a Non-Traditional Dance Teacher’,

Dance Research Journal, 27: 2, pp. 3–15.

Fortin, S., Vieira, A. and Tremblay, M. (2009), ‘The Experience of Discourses in

Dance and Somatics’, Journal of Dance and Somatic Practices, 1: 1, pp. 47–64.

Fraleigh, S. (1979), Dance and the Lived Body, Pittsburgh, PA: University of

Pittsburgh Press.

252 Rebecca Weber

JDSP_1.2_art_Weber_237-254.indd 252 5/11/10 6:11:14 PM

Gilchrist, V. and Williams, R. (1999), ‘Key Informant Interviews’, in B. Crabtree

and W. Miller (eds), Doing Qualitative Research, 2nd edn., Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage Publications, pp. 71–89.

Green, J. (1999), ‘Somatic Authority and the Myth of the Ideal Body in Dance

Education’, Dance Research Journal, 31: 2, pp. 80–100.

Halprin, A. (2000), Dance as a Healing Art: Returning to Health Through Movement

and Imagery, Mendocino, CA: LifeRhythm Energy Field.

Halprin, D. (2003), The Expressive Body in Life, Art and Therapy: Working with

Movement, Metaphor and Meaning, London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Hanna, T. (1970), Bodies in Revolt: A Primer in Somatic Thinking, New York: Holt

Reinhart.

Hartley, L. (1995), Wisdom of the Body Moving: An Introduction to Body-Mind

Centering, Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

ISMETA (2009), ‘International Somatic Movement Education and Therapy

Association’, http://www.ismeta.org. Accessed 19 March 2010.

Johnson, D. (1983), Body: Recovering our Sensual Wisdom, Boston, MA: Beacon

Press.

Johnson, D. (1986), ‘Principles Versus Techniques: Towards the Unity of the

Somatics Field’, Somatics, 6: 7, pp. 4–8.

Kleinman, S. (1990), ‘Moving Into Awareness’, Somatics, pp. 4–7.

Linden, P. (1994), ‘Somatic Literacy: Bringing Somatic Education Into Physical

Education’, Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance, 65: 7,

pp. 15–21.

Long, W. (2002), ‘Sensing Difference: Student and Teacher Perceptions on the

Integration of the Feldenkrais Method of Somatic Education and Contemporary

Dance Technique’, MPE thesis, Dunedin, New Zealand: University of Otago.

Lowell, D. (2006), ‘Authentic Movement’, in P. Pallaro (ed.), Authentic Movement –

Moving the Body, Moving the Self, Being Moved: A Collection of Essays, Vol. II,

London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, pp. 50–55.

Minton, S. (2000), ‘Research in Dance: Educational and Scientific Perspectives’,

Dance Research Journal, 32: 1, pp. 110–16.

Myers, M. (1980), ‘Body Therapies and the Modern Dancer: Dance Training’s New

Frontier’, Dance Magazine, April, pp. 78–82.

Miles, M. and Huberman, A. (1994), Qualitative Data Analysis, 2nd edn., London:

Sage.

Nelson, R. (2009), Series of personal interviews, 19–21 October.

Orbach, S. (2009), Bodies, London: Profile Books.

Pallero, P. (ed.) (1999), Authentic Movement: Essays by Mary Starks Whitehouse,

Janet Adler and Joan Chodorow, London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Roth, G. (2000), Sweat Your Prayers: Movement as Spiritual Practice, New York:

Tarcher/Penguin.

—— (2009), ‘Five Rhythms Global’, available at http://www.gabrielleroth.com/.

Accessed 19 March 2010.

Stromsted, T. and Haze, N. (2006) , ‘The Road In: Elements of the Study and

Practice of Authentic Movement’, pp. 56–69, in Pallaro, P. (Ed.) (2006).

Authentic movement: Moving the body, moving the self, being moved, a collection of

essays. Levittown, PA Jessical Kingsley Publishers.

Trimingham, M. (2002), ‘A Methodology for Practice as Research’, Studies in

Theatre and Performance, 22: 1. pp. 54–60.

Integrating semi-structured somatic … 253

JDSP_1.2_art_Weber_237-254.indd 253 5/11/10 6:11:14 PM

Tufnell, M (2008), Practice observation in teaching practice with MA students,

University of Central Lancashire, 16 November.

Williamson, A. (2009a), ‘Formative Support and Connection: Somatic Movement

Dance Education in Community and Client Practice’, Journal of Dance and

Somatic Practices, 1: 1, pp. 29–45.

—— (2009b), MA Dance and Somatic Well-Being: Connections to the Living Body,

University of Central Lancashire. pp. 1–8, available at http://www.uclan.

ac.uk/information/courses/files/connections.pdf. Accessed 19 March 2010.

—— (2009c), ‘Ludus Dance: Career Options – Moving, Relaxing, and Reflecting:

Somatic Movement Dance Education’, pp. 1–4, available at http://www.

ludusdance.org/download?id=38. Accessed 19 March 2010.

Wililamson, A. (2009d), Practice observation in teaching practice with MA

students, University of Central Lancashire, 14–17 November.

—— (2010a), ‘Self-Regulation: Play, Pleasure, and Rest’, University of Central

Lancashire, in possession of the author [pending publication].

—— (2010b), Series of personal interviews, 12–31 January.

Suggested citation

Weber, R. (2009), ‘Integrating semi-structured somatic practices and contemporary

dance technique training’, Journal of Dance and Somatic Practices 1: 2, pp. 237–254,

doi: 10.1386/jdsp.1.2.237_1

Contributor details

Rebecca Weber holds a Master’s degree in Dance and Somatic Well-Being:

Connections to the Living Body (UK) from the University of Central Lancashire. She

is an academic and artist who seeks to find the places where dance and somatics

intersect, incorporating them into both her teaching and personal dance practices.

She is currently dancing and developing a somatic movement dance education

practice in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (USA).

E-mail: beccaweber@gmail.com

254 Rebecca Weber

JDSP_1.2_art_Weber_237-254.indd 254 5/24/10 9:29:15 AM

You might also like

- Dance Science: Anatomy, Movement Analysis, and ConditioningFrom EverandDance Science: Anatomy, Movement Analysis, and ConditioningRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Integrating Semi Structured Somatic Practices and Contemporary Dance Technique TrainingDocument19 pagesIntegrating Semi Structured Somatic Practices and Contemporary Dance Technique TrainingYonoh YorohNo ratings yet

- Somatic Studies PDFDocument6 pagesSomatic Studies PDFAna Carolina PetrusNo ratings yet

- PE - LET ReviewerDocument26 pagesPE - LET ReviewerPidot Bryan N.100% (1)

- PE 1 LEt Material With TOS Foundations oDocument26 pagesPE 1 LEt Material With TOS Foundations orickNo ratings yet

- The Evolvement of The Pilates Method and Its Relation To The Somatic Field (Inglés) Autor Leena Rouhiainen PDFDocument13 pagesThe Evolvement of The Pilates Method and Its Relation To The Somatic Field (Inglés) Autor Leena Rouhiainen PDFDenise RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Feldenkrais For DancersDocument12 pagesFeldenkrais For DancersGemma So-HamNo ratings yet

- Embodied Enactive DMT - Por Sabien C. Koch y Diana FischmanDocument16 pagesEmbodied Enactive DMT - Por Sabien C. Koch y Diana Fischmanroselita321No ratings yet

- Shusterman, Richard (2020) Somaesthetics in ContextDocument10 pagesShusterman, Richard (2020) Somaesthetics in ContextchuckNo ratings yet

- Somatic StudiesDocument6 pagesSomatic StudiesÖzlem AlkisNo ratings yet

- Somatic Knowledge The Body As Content and Methodology in Dance EducationDocument6 pagesSomatic Knowledge The Body As Content and Methodology in Dance EducationziyuedingNo ratings yet

- Effect of Dance Motor Therapy On The Cognitive Development of Children PDFDocument19 pagesEffect of Dance Motor Therapy On The Cognitive Development of Children PDFLissette Tapia Zenteno100% (1)

- Rishikesh Seminar Content - SSSOHADocument13 pagesRishikesh Seminar Content - SSSOHARabindra DhitalNo ratings yet

- Biomechanics &kinesiology B.P.ed. NotesDocument38 pagesBiomechanics &kinesiology B.P.ed. NotesRATHNAM DOPPALAPUDI82% (22)

- Biomechanics Kinesiology B P Ed Notes 1Document38 pagesBiomechanics Kinesiology B P Ed Notes 1Govind GovindNo ratings yet

- The Evolvement of The Pilates Method in The Somatic FieldDocument13 pagesThe Evolvement of The Pilates Method in The Somatic Fieldhappygolucky90No ratings yet

- A Phenomenological Inquiry: Pleasantness in Bodily ExperienceDocument9 pagesA Phenomenological Inquiry: Pleasantness in Bodily ExperienceklenNo ratings yet

- Dance Science and The Dance Technique Class PDFDocument11 pagesDance Science and The Dance Technique Class PDFbhargavi gopalanNo ratings yet

- Please Scroll Down For ArticleDocument20 pagesPlease Scroll Down For ArticleGervasius AdamNo ratings yet

- Dance Expertise Embodied CognitionDocument21 pagesDance Expertise Embodied CognitionIrene Alcubilla TroughtonNo ratings yet

- History and Philosophy of Movement EducationDocument6 pagesHistory and Philosophy of Movement EducationJewel Marie BayateNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Essentials of Human Anatomy Physiology 10th Edition by MariebDocument11 pagesSolution Manual For Essentials of Human Anatomy Physiology 10th Edition by MariebCecelia Sams100% (33)

- Anda 2022 Artigo Final Anais EnglishDocument17 pagesAnda 2022 Artigo Final Anais EnglishKiran GorkiNo ratings yet

- History of Movement EducationDocument4 pagesHistory of Movement EducationMark FernandezNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Physical Literacy (Whitehead, 2001)Document13 pagesThe Concept of Physical Literacy (Whitehead, 2001)Alberto I. Cruz FloresNo ratings yet

- UNIT 1: Introduction To DanceDocument7 pagesUNIT 1: Introduction To DanceLeticia SibayanNo ratings yet

- Neurocognitive DanceDocument12 pagesNeurocognitive DanceKristina KljucaricNo ratings yet

- The Art and Science of Somatics Theory HDocument113 pagesThe Art and Science of Somatics Theory HAna Carolina Petrus0% (1)

- Jacobsen 2010 Journal of AnatomyDocument8 pagesJacobsen 2010 Journal of AnatomyjuanjoteNo ratings yet

- Physical Literacy From Philosophy To Practice (Pot Et Al., 2018)Document6 pagesPhysical Literacy From Philosophy To Practice (Pot Et Al., 2018)Alberto I. Cruz FloresNo ratings yet

- The Motor Coordination Reasoning in Acting DancerDocument9 pagesThe Motor Coordination Reasoning in Acting DancertauneantonioNo ratings yet

- Art 36 406 2022-1.es - enDocument11 pagesArt 36 406 2022-1.es - enKarla PeñaNo ratings yet

- Vol9 Art4 Gomes-Cochet-Guyon DanceDocument23 pagesVol9 Art4 Gomes-Cochet-Guyon DanceNorma GomesNo ratings yet

- The Past, Present, and Future Of.2Document7 pagesThe Past, Present, and Future Of.2Jimena JimenezNo ratings yet

- ADTA Final Document BIO Plus PAPER DEVIKA MEHTADocument10 pagesADTA Final Document BIO Plus PAPER DEVIKA MEHTAsynchrony indiaNo ratings yet

- TEMA 5. Estrategias para La Promoción Efectiva de Actividad FísicaDocument8 pagesTEMA 5. Estrategias para La Promoción Efectiva de Actividad Físicaluis marti gomezNo ratings yet

- AnatomyDocument105 pagesAnatomyGaray, Mark Niño D.100% (1)

- Aesthetic Experience Explained by The Affect-SpaceDocument20 pagesAesthetic Experience Explained by The Affect-SpaceSupawan Ao-thongthipNo ratings yet

- Choi2017 The Effects of Floor-Seated ExerciseDocument6 pagesChoi2017 The Effects of Floor-Seated ExerciseFaizul HasanNo ratings yet

- Access-To-Somatics Martha EddyDocument11 pagesAccess-To-Somatics Martha EddyVALERIA BORRERO GONZALEZNo ratings yet

- Neuroanatomical Aspects of The Body Awareness: Journal of Morphological Sciences January 2011Document5 pagesNeuroanatomical Aspects of The Body Awareness: Journal of Morphological Sciences January 2011labsoneducationNo ratings yet

- Effects of Dance Training and EducationDocument38 pagesEffects of Dance Training and EducationMarian ChiraziNo ratings yet

- The Nature, Concepts and Objectives of PhysicalDocument51 pagesThe Nature, Concepts and Objectives of PhysicalRyann Claude SionosaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Pole Dance On Mental Wellbeing and The Sexual Self-Concept-A Pilot Randomized-Controlled TrialDocument7 pagesEffects of Pole Dance On Mental Wellbeing and The Sexual Self-Concept-A Pilot Randomized-Controlled Trialnoemi.hegedus11No ratings yet

- The Development of Bodily - Kinesthetic Intelligence Through Creative Dance For Preschool StudentsDocument10 pagesThe Development of Bodily - Kinesthetic Intelligence Through Creative Dance For Preschool StudentsChí Huỳnh MinhNo ratings yet

- Mindfulness For Singers The Effects of A Targeted Mindfulness Course On Learning Vocal Technique PDFDocument23 pagesMindfulness For Singers The Effects of A Targeted Mindfulness Course On Learning Vocal Technique PDFMatt WilkeyNo ratings yet

- Physical Literacy For TheDocument11 pagesPhysical Literacy For TheMatheus FreireNo ratings yet

- 2021 - 1st Sem - INTRODUCTION TO ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY TRANSDocument7 pages2021 - 1st Sem - INTRODUCTION TO ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY TRANSMaria Emmaculada ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- Part I - Knowledge Update: Theories and Principles of Physical EducationDocument20 pagesPart I - Knowledge Update: Theories and Principles of Physical EducationEarshad Shinichi IIINo ratings yet

- (English Version) Workshop - Caio Zenero Pinheiro - 26th IIBA International ConferenceDocument9 pages(English Version) Workshop - Caio Zenero Pinheiro - 26th IIBA International Conferencecaio pinheiroNo ratings yet

- PhysicalLiteracy OctJOPERDDocument4 pagesPhysicalLiteracy OctJOPERDkhaled mohamedNo ratings yet

- The Kinesthetic SystemDocument8 pagesThe Kinesthetic SystemCANDELA SALGADO IVANICHNo ratings yet

- Aplicabilidade Da Dança Terapêutica para Recuperação Funcional de Portadores de Distúrbios Percepto-MotoresDocument8 pagesAplicabilidade Da Dança Terapêutica para Recuperação Funcional de Portadores de Distúrbios Percepto-MotoresAngelaNo ratings yet

- Ontological Coaching SIELERDocument20 pagesOntological Coaching SIELERAdrian Raynor100% (1)

- 2013 - Kettensthoth - Six Months of Dance InterventionDocument16 pages2013 - Kettensthoth - Six Months of Dance InterventionElisabet Rodriguez BiesNo ratings yet

- Fabio - Long-Term Meditation Cognitive Processes and MindfulnessDocument14 pagesFabio - Long-Term Meditation Cognitive Processes and MindfulnessFernandoNo ratings yet

- Teorija, Terapija I Istrazivanje Senzorne IntegracijeDocument10 pagesTeorija, Terapija I Istrazivanje Senzorne IntegracijeJohn SmithNo ratings yet

- Section 1. Chapter 1 & 2Document47 pagesSection 1. Chapter 1 & 2Abril Acenas83% (6)

- Body Memory - Current State of Research: 1. Thankstoprojectgrant01Ub0390Aofthebmbf (GermanfederalministryofeducationDocument6 pagesBody Memory - Current State of Research: 1. Thankstoprojectgrant01Ub0390Aofthebmbf (GermanfederalministryofeducationtornadointempestivoNo ratings yet

- Tpeh Output 1Document3 pagesTpeh Output 1Shaira Colleen Merano VillamorNo ratings yet