Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hake GirlsCrisis 1987

Uploaded by

X1ndyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hake GirlsCrisis 1987

Uploaded by

X1ndyCopyright:

Available Formats

Girls and Crisis - The Other Side of Diversion

Author(s): Sabine Hake

Source: New German Critique , Winter, 1987, No. 40, Special Issue on Weimar Film

Theory (Winter, 1987), pp. 147-164

Published by: Duke University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/488136

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Duke University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

New German Critique

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Girls and Crisis - The Other Side of Diversion

by Sabine Hake

"The audience of the cinema is the classless audience." I

This essay will examine a group of early texts by Siegfried Kracauer

that pertain to the cinema and the pleasures it invites. Situating film in

relation to other phenomena of modern life, these texts map out a

landscape of desire and its modes of production. In doing so, they

could contribute to a conceptualization of a "history of pleasure," as

Thomas Elsaesser has suggested for the study of Weimar cinema in a

recent essay.2 "Kult der Zerstreuung" (Cult of Diversion), "Die

kleinen Ladenmadchen gehen ins Kino" (The Little Shopgirls Go to

the Movies) and "Das Ornament der Masse" (The Mass Ornament)

are central texts which are not only long overdue for critical evaluation

of Kracauer's writings in the United States - they also invite an exam-

ination of the structuring of desire that is highly relevant today.

Kracauer's central category in this enterprise is the concept of diver-

sion by which the cinema is thrown into a nexus of discourses that is

torn between modern regression and radical change. As a handy at-

tribute, the term Zerstreuung (diversion)3 acquired fashionable status in

the 1920s, recurring on the pages of the bourgeois press, and elegantly

combining disdain for the new medium and its uncultivated adher-

ents with an obsessive fascination. Kracauer was one of the first to pay

serious attention to the mechanisms of diversion which he closely

1. Carlo Mierendorff, "Hitte ich das Kino," in Anton Kaes (ed.), Kino-Debatte

(Tiibingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag, 1978), p. 139.

2. Thomas Elsaesser, "Film History and Visual Pleasure: Weimar History," in

Patricia Mellencamp and Philip Rosen (eds.), Cinema Histories, Cinema Practices (Los

Angeles: American Film Institute, 1984), p. 51.

3. For this text I will translate Zerstreuung as "diversion" rather than as "distraction,"

since the latter, in my opinion, represses the ambivalences preserved in "diversion."

Through the process of translation, the word's original complex field of connotations

becomes fragmented, a political tendency thereby being disguised; a tendency that, af-

ter all, is fully restored when set against its conceptual opposite, namely concentration,

composure, knowledge.

147

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

148 Girls and Crisis

linked to the development of the modern city, the economic changes

towards a society and culture of white-collar workers and the destruc-

tion of traditional class structure. He revealed the word's negative

connotation that derived from humanistic education and from overly

sharp distinctions between high and low culture. He was also one of

the first critics to approach popular culture as deserving of close scru-

tiny and to employ a theory of diversion reflecting the inherent

ambivalences of the studied subject itself. In an analysis of changed

relations between audience and popular culture, Kracauer's concept

of diversion not only qualifies as a tool of social theory, but as a neces-

sary category for progressive media theory. He asserts: "But the cine-

ma has more urgent tasks to take care of than to court the artsy-craftsy.

Its true purpose - of an aesthetic nature only when attuned to its so-

cial aspects - will be fulfilled only when it stops flirting with the

theater, anxiously attempting to restore a bygone culture. On the con-

trary, it needs to liberate representation from all alien elements and to

aim radically at a diversion that exposes the decline instead of disguis-

ing it."4

Crucial for a critical reading of Kracauer's texts on cinema are his

references to a specifically female audience. The cynicism of "The Lit-

tle Shopgirls Go to the Movies" reveals not only the sexism underlying

the concept of diversion, but illuminates it from a different perspec-

tive. The negative attribution of diversion to the feminine helps ex-

plain the concept's hidden ambivalences and obvious grey areas as an

evasion of the urgent issues behind it - most of all the social and po-

litical emancipation of women and the identification of the feminine

as a threat to the bourgeoisie. Instead of concentrating on the particu-

lar relation between image and individual spectator (as many contem-

porary theories do), Kracauer's concept of diversion has to be seen in

reference to a social body and socially conceived modes of entertain-

ment, held together in their shifting impact and oscillating qualities.

In the light of postmodern thinking, diversion cannot be dismissed as

an individual's private economy of drives or as omnipotent manipula-

tion, but needs to be reappropriated as a surface phenomenon that

usually escapes the critic's eye. Thus, with the undercurrent of

phenomenological thinking, it may prove helpful in establishing a so-

cial history of the cinema and the popular arts in general, a history that

also insists on differentiating between European and American cine-

ma as well as their positions within the culture industry. The

4. Siegfried Kracauer, "Kult der Zerstreuung," in Das Ornament der Masse (Frankfurt/

Main: Suhrkamp, 1977), p. 317. All following translations are my own, unless indicated

otherwise.

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sabine Hake 149

formative years of German cinema were, after all, not only character-

ized by battles against the traditional representational art forms, but

also by a specific obligation to prove its cultural respectability. The ne-

cessity of proving moral alibis informed the specific qualities of th

German cinema (e.g. the lack of comedies) and a discourse on cinema

as it will be examined in Kracauer's scattered texts on diversion.

"It is always said of Georg Luktcs that his best stuff isn't in English.

Kracauer's best stuff isn't in English either."5 What Pauline Kael in-

tended as scathing remarks on Kracauer's Theory of Film, ironically -

within the larger context of Kracauer's writings - becomes true when

one has the chance to read his early texts, namely those published as

reviews and serials for the liberal Frankfurter Zeitung. It is a reading ex-

perience full of surprises. The reception of Kracauer's writings in Ger-

many and the United States differs immensely. For American readers,

Kracauer emerges as a film theorist with his arrival in the United States

as a refugee and with his ambition to write in English only.6 With the

exception of two essays - one being "Bloch zu Ehren" - he never

again published in his native tongue, a decision that distinguished

him from the majority of the exile community. Possibly influenced by

his cultural displacement, the American Kracauer appears speculative

and often ponderous.7 His writings in English evidence a growing dis-

tance from the subject of his studies; they also take a more metaphysi-

cal direction. While From Caligari to Hitler conveys the need for a mate-

rialist analysis (including an excellent, unfortunately often ignored

methodological part) and is fueled by the knowledge of existing alter-

natives, the later Theory of Film is limited by a very narrow concep-

tualization of realism in film. On the other hand, there is the German

misconception of Kracauer as the eminence grise of film sociology. Ger-

man readers had to wait until 1979 for the publication of the complete

study of Weimar cinema, preceded only by a badly mutilated edition

(published by Rowohlt in 1958); initially the work was one-dimen-

sionally linked to a specific breed of politicized film criticism

5. Pauline Kael, "Is There a Cure for Film Criticism?" in I Lost It at the Movies (Bos-

ton: Little & Brown, 1965), p. 269.

6. In a letter to Hermann Hesse, Kracauer confesses: "I have written the book [From

Caligari to Hitler] in English. To conquer this language as a writer is a real passion for me,

and every inch of conquered territory means a lot to me." Siegfried Kracauer, Von

Caligari bis Hitler (Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp, 1979), appendix, p. 607.

7. Peter Harcourt evokes the image of somebody buried in a library, as quoted by

Dudley Andrew, The Major Film Theories (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976), p.

107. Even German critic Frieda Grafe remarked in an review: "One should not blame

Kracauer. He, too, is a victim of books." Frieda Grafe, "Doktor Caligari versus Doktor

Kracauer," in Filmkritik 5/1970, p. 244.

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

150 Girls and Crisis

emerging in the 1960s. According to Adorno, otherwise one of his

most caustic critics, Kracauer was one of the first to set the foundations

for such a tradition in German film criticism. Thus his name became

associated with the conceptualization of film history as a body of re-

current motifs, a conceptualization inspired by sociology and the ba-

sic assumptions of Critical Theory. However, this reference to

Kracauer's effect on contemporary followers strangely enough did not

stem from his own writings in the 1920's, but from his becoming a

phantom (indeed a later personification of Caligari) for a guilt-ridden

post-war generation looking for answers to the tragedy.

In 1921, after ten years of working as an architect in Hanover,

Osnabruck, Frankfurt and Munich, Kracauer, now in his thirties,

joined the Frankfurter Zeitung. He soon became acquainted with

Benjamin, Bloch and Adorno and it was on Bloch's advice that he de-

veloped a stronger interest in social theories. After having published

Soziologie als Wissenschaft (Sociology as a Science, 1922), he became cul-

tural editor of the Berlin branch of the Frankfurter Zeitung. Until 1933

and his emigration to Paris, he produced numerous reviews as well as

longer and more structured pieces of analysis - the essay became his

favorite medium. Therefore, despite its obvious impact, this side of

Kracauer remains to be discovered. Benjamin, not without reason,

described him a a "rag-and-bone-man, early - at the dawn of the rev-

olution."8 A reading of his essays indeed reveals this junkyard

atmosphere as well as the passion for the accidental find.

From a diametrically opposed point of view, Ilja Ehrenburg simi-

larly designates diversion as the most predominant characteristic of

cinema. Elaborated in Traumfabrik (Dream Factory, 1931), his notions of

cinema's manipulative powers may seem crude today, but they are,

particularly for the cinematic literary style, a good introduction into

the multilayered meanings of diversion and its range of inter-

pretations. Ehrenburg imagines a working-class couple leaving the

cinema: "Quick. The show is over. We'll miss the bus. Tomorrow

morning we have to get up early. Tomorrow like today, today like yes-

terday. Nancy Caroll is far away. No lingerie. Mend socks. You said

papa Zukor? Don't know him. I work for Smith & Co. Go home quick!

Quick! Night, moist, blue night. Smells different in each town, but is

full of tears and fear everywhere. Following the day, anticipating the

day. You can still jump into the river. In the Thames. Or the Seine. Or

the Hudson. Or the Spree. You can still open the gas. There is still time

8. Walter Benjamin, "Politisierung der Intelligenz," in Siegfried Kracauer, Die

Angestellten (Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp, 1971), p. 123.

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sabine Hake 151

to sleep. Sleep. Just sleep. ... Vast hordes burst out of thousands of

movie theaters. They run and seep away in narrow, black fissures. This

old fat German holds his breath. What if the Flying Dutchman ap-

pears to him tonight? No police will protect him! His heart stops. The

American cleans his foggy glasses. The member of the komsomol

turns her head in suspicion: snow and crows everywhere, a horse sigh-

ing under the snow - what will be tomorrow? The Japanese giggles

hysterically. It has started. The earth trembles. ... They have left. They

have spread, with devastated senses and half dead. They feel being fol-

lowed. Somebody still throws splotches of light onto the wall. Some-

body sings in front of the window, in the chimney, in the faucet: 'Har-

ry, I'll always be yours.' Then these dreams will take the shape of the

cruel morning, the one of screws and types. Screw! Become a

Rockefeller! Type on the machine! Novarro will fall in love with you.

Your boss will fall in love with you. Will take you. Will infect you.

You'll lie down like Miss Elsie. Escorted to paradise by police. Angels

and worms. Type faster: 'In response to your... your... your...' This is

the big magic box that reigns the world. This is a great invention and

this is wasteland, cruel, fascinating monotony. This is film!"9

Ehrenburg's case study of movie attendance reads like the classic

example of Kracauer's "Cult of Diversion." He assembles the ele-

ments of late capitalist society - the factory and the handsome movie

hero, the typing pool and the swimming pool - as they surface from

the stream of consciousness of a typical genderless (i.e.,

interchangeably gendered) petty bourgeois subject: manipulation

reigns. Though completed in Paris, Ehrenburg's Dream Factory posits

Berlin as the prototype of the faceless modern metropolis. Berlin, ex-

plored one year earlier by Kracauer in an expedition that he called

more adventurous than entering theJungles of Africa, became subject

of his sociological study Die Angestellten (The Employees, 1929) on the

taylorization of the entertainment industry: "Berlin today is the

prominent place of a culture of employees, that means of a culture

made by employees for employees and considered by most employ-

ees as culture."'0 Kracauer's concept, as Ehrenburg's, proceeds from

a social space, the modern city. Berlin and Paris were, possibly, the

European cities where cinema established itself not only as a new me-

dium, but as the ultimate cultural experience. The cinema, consid-

ered in its totality, integrating economic, political and cultural aspects

in a radical interdependency never experienced before, became the

9. Ilja Ehrenburg, Die Traumfabrik (Berlin: Malik, 1931), p. 302ff.

10. Kracauer, Die Angestellten, p.15.

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

152 Girls and Crisis

primary mirror of modern lifestyles in the mid-1920s. At the time of

Kracauer's writings, this most eclectic of all representational tech-

niques had established a place in the urban landscapes that could only

be compared to the cathedral. It was installed as a melting pot for an

alienated but fashionable city audience, a refuge from disturbing ex-

periences and a sensory training ground, in short: the locus, where

modern man was exercised in the appropriation and appreciation of

modernity.

It is this experience that radically enters the organization of the text

in Ehrenburg's finale. He creates an inferno of slogans, crude sensa-

tions, random identification and tranferences - the mimicry of an

evening at the movies that is closer to a nightmare. A Freudian uni-

verse indeed, in which the montage of propagandistic headlines in-

trudes; these are inserted as the voice of the savant (Ehrenburg him-

self), who raises his index finger in crude agitation and pseudo- Marx-

ist exorcism. The variety and intensity of sounds are remarkable, the

noise that a silent film is capable of originating in the spectator's head.

Sympathetically reviewing Ehrenburg's Dream Factory as a profound

description of the cinema, Kracauer departs from the former's evident

disapproval of mass culture by calling the book "an apocalyptic paint-

ing of the capitalist world."''" In linking diversion to the experience of

city life, Kracauer, for his part, offers a vision of the functioning of ide-

ology, that can help rediscover lost paths of sensibility. His essays are

crucial for an understanding of the tremendous impact that cinema

had in constructing the uniform, seemingly classless subject of con-

sumer society. These texts also render possible a rediscovery of the

city's power (again as place of the structural transformation of society,

but this time leading to the demolition of the bourgeois subject) and

of the promises and pleasures provided by film's flashing images.

Written by such prominent authors as BalIzs, Arnheim, Ehrenburg,

Brecht and Benjamin, they possibly also call to mind the participation

of the cinema in a utopian concept of mass culture: a connection that

relies more on the cinema's specific modes of perception than on the

film's aesthetic form.

If Kracauer's diverse contributions to an analytical, but still appre-

ciative understanding of modern culture needs to be located in a grid

constructed of political loyalities and the views of intellectual peers, it

is Walter Benjamin, who - not just in favoring the essay as the only

possible form of writing - is closest to the Kracauer of the 1920s and

1930s. Like Kracauer, Benjamin examines the phenomenon of diver-

11. Kracauer, Von Caligari bis Hitler, appendix, p. 531.

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sabine Hake 153

sion in the light of the relation between cinema and modern city. Th

concept of diversion was utilized by both authors in reflecting on Par

as the capital of the 19th century: by Kracauer in Orpheus in Paris: Offe

bach and the Paris of His Time (1937) and by Benjamin both in "Paris

Capital of the Nineteenth Century" and "Some Motifs in Baud

laire." Benjamin used the word 'shock' to describe both the worke

experience at the machine and that of the pedestrian in the crowd, as

he/she strolls the boulevards, visits loud bars and conforms to traffic

rules. The effects of 'shock' are also typical in film which flourish

precisely on the city's atmosphere and dangers. Benjamin writes

"Thus technology has subjected the human sensorium to a compl

kind of training. There came a day when a new and urgent stimuli wa

met by film. In a film, perception in the form of shocks was esta

lished as a formal principle. That which determines the rhythm o

production on a conveyer belt is the basis of the rhythm of reception

in the film."'2

Benjamin's Paris of the shopping arcades, boulevard society, iro

constructions and world exhibitions is - although approached from

another side - also captured in Kracauer's reconstruction ofJacqu

Offenbach's biography. Kracauer makes Offenbach's career a meta

phor for a specific society that moved him and was moved by him

society that is identified as the predecessor of modernity. Analyzi

the origins and decline of the operetta, he applied the same herm

neutic techniques that he had introduced in his analysis of the a

sumed correlation between shopgirls and film culture. Written in the

1930s, between the flight from Germany and his ultimate exile in th

United States, Orpheus in Paris is Kracauer's attempt to return to the

historical source of surface phenomena. This study argues that the au

dience actually pre-existed the technological emergence of cinem

The significant mood of Parisian society was not only traceable in the

figure of the flaneur, but in various other phenomena as we

flirtatiousness, gossip, window shopping, lithography, magazine

And boredom as the complementary side to diversion already pr

pared the Parisian society for the hilariously exaggerated parody

bourgeois society that lay at the core of Offenbach's best operett

Kracauer's description of that historical period and the examinati

of the social and cultural functions of the operetta thus amounts to t

status of a model as it was first conceptualized in his early texts on cin

ema.13

12. Walter Benjamin, "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,"

Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken, 1969), p. 17

13. Not surprisingly, Adorno excoriated the harmony of subject and method

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

154 Girls and Crisis

Walter Benjamin later elaborated the genesis of diversion in his of-

ten quoted essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical

Reproduction" (1934) by opposing the traditional object of art and

the new mass media. Reception in a state of distraction, which is in-

creasingly noticeable in all fields of art and is symptomatic of pro-

found changes in apperception, finds in film its true means of exer-

cise."'4The changed relation between art and the masses was intro-

duced by a qualitative changes in mechanical reproduction: film and

photography became the prototypes for the intrusion of the apparatus

into reality. The images are fragmented, just as life itself: "Thus for

contemporary man the representation of reality by the film is

incomparably more significant than that of the painter, since it offers,

precisely because of the thorough-going permeation of reality with

mechanical equipment, an aspect of reality which is free of all equip-

ment. And that is what one is entitled to ask from a work of art.''5" We

find in Benjamin, as in Kracauer, this motif of radicalization. Both see

the social importance of film as that of a medium for whose audience

the critical and receptive aspects coincide, thus its importance as a lo-

cus of collectivity.

Set against the style of his contemporaries, Kracauer's early essays

on film rely on a challenging set of aesthetic categories operating

around the central idea of production and consumption. The claim of

film criticism to liberate itself from the status of the industry's promo-

tion tool and to become a genuine genre of cultural criticism was first

stated in Kurt Pinthus' polemic "Quo vadis Kino?" (1913). But this

approach remained isolated until the late 1920s and the emergence of

materialist analyses (Ehrenburg, Balazs, Arnheim, Kracauer), while a

guild of highly eloquent theater critics (Kerr, Ihering, Polgar) was still

setting the tone. The majority of feature writers were and remained

men of literature and the theater, the omnipotentjudges of good taste,

installed by a waning class of Bildungsbiirger. Even in refusing to perpet-

uate the hackneyed dichotomy between film and theater, topic of in-

numerable discussions, most writers usually evaded the problem of

revealing a politically relevant standpoint by granting each medium

its specific qualities, but implying the superiority of the theater.

Karsten Witte, Kracauer's German editor, describes Kracauer's

method of criticism as 'production criticism', one that is sharply set

Orpheus in Paris, calling Kracauer's lightness a deceptive device for justifying his evident

pleasure in painting the picture of a frivolous society. See Theodor W. Adorno, in

Zeitschrfi fur Sozialforschung, Vol. 6, No. 3, p. 697.

14. Benjamin, p. 240.

15. Ibid., p. 234.

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sabine Hake 155

against a criticism based on taste. Starting from the assumption tha

the cinema represents the most advanced sector of the consciousness

industry, Kracauer reads any work, be it an art object or a commodity,

within its historical and aesthetic context. He defines the task of a film

critic as similar to the work of a surgeon (cf. Benjamin's comparison

between the camera's intrusion into reality and the surgical act). With-

in such a logic, the superficial products of entertainment are the pre-

ferred objects, since their meaning lies so close to the surface: "The

task of the effective film critic lies in analyzing those social intentions,

hidden in average film, and in pulling them out into the daylight

which they often eschew."'16 It is in his essays on Berlin that Kracauer

consistently applies his concept of diversion. It soon becomes a cen-

tral category in his writings, in the evaluation of the single film as well

as in a more sociologically oriented description of its audience. In re-

lation to the multiple connections the term creates, the crucial tex

"Kult der Zerstreuung" (Cult of Diversion, 1926) is surprisingly short.

A specific atmosphere defines life in Berlin in those days, "that one

day all of this will explode into pieces."" From this experience of the

city's destructive, but at the same time unifying quality, a direct road

leads to the sacred palaces of entertainment multiplying on the boule-

vards and to other replicas of Parisian splendor. The point of depar-

ture is the analysis of the emergence of a new type of movie theater

(Lichtspieltheater) that is not worth being called cinema (Kino), since it

surrrenders its inherent possibilities and betrays its new audience.

Those new places are designed by the same architects who build film

sets on the periphery of the city, at the UFA studios in Neu-

Babelsburg (e.g. Professor Poelzig, responsible for the clay orgy o

"The Golem" and the luxurious cinema "Kapitol-Palast"). While the

older theaters (Kientopp) are driven out to the suburban neighbor-

hoods with a more proletarian clientele, the modern film spectacle or-

ganizes itself and its audience. Kracauer relates two crucial develop-

ments: the socio-cultural sphere of the metropolis that is forming the

homogenous mass of isolated individuals, thus precipitating the de-

cline of bourgeois culture, and a new social group, the army of em-

ployees that is stating a legimitate demand for forms of entertainment

appropriate to and reflecting its living conditions. In The Employees

Kracauer very clearly defines the ideological dilemma of this new

class: "The majority of the employees differs from the worker's prole-

tariat in being intellectually homeless. For the time being they are un-

16. Kracauer, Kino, ed. Karsten Witte (Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp, 1974), p. 10.

17. Kracauer, "Kult der Zerstreuung," in Das Ornament der Masse, p. 315.

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

156 Girls and Crisis

able to join the comrades, and the house of bourgeois concepts and

feelings, which they had occupied, has collapsed, because, due to eco-

nomic developments, it has lost its foundations. They presently live

without a theory to turn to and without a goal to pose their questions.

Thus they live in fear to look up and ask questions till the end."'

Therefore the employees go to the movies, making the cinema, and

popular diversion in general, their refuge. In The Employees, originally

conceived as a newspaper series on the loves and lives of office-work-

ers, Kracauer implies an interchangeability between the spheres of

work and entertainment by calling the places of pleasure 'barracks of

pleasure' (Plisirkasernen) and equating the company (Betrieb) with the

entertainment industry (Vergniigungsbetrieb), both functioning accord-

ing to the same laws of consumption and exploitation. Kracauer

openly greets this decline of high culture - at least in its function as a

dominating model - and hopes for its substitution by an industrialized

mass-culture, whose audience "from the bank director down to the

sales assistant, from the diva to the typist are of one mind."'9 Thus the

possiblity of breaking up petrified social conditions is palpable and of-

fers, as well, the chance to terminate repressive anachronisms. Kracauer

reviles as philistines those who accuse the audience of diversion. Only in

following the urge towards extreme diversion may the audience come

close to the truth. Only in petpetuating the workday's empty tensions

through the superficiality of entertainment are they able to save the hon-

esty of their existence. Consciousness of one's own reality through the

purity of surfaces - this precisely is Kracauer's concept of diversion.

In "The Mass Ornament," diversion is developed from a reflection

on the Tiller-Girls, a popular dancing troop. Kracauer describes his ana-

lytical concept: "An analysis of the simple surface manifestations of an

epoch can contribute more to determining its place in the historical pro-

cess than judgments of the epoch about itself."20 From the assembly

line, the same aesthetic principle of serialization is at work. This notion

of the surface as the place of least petrifications and therefore the most

accessible to analysis, is in Kracauer's later texts extended to include

non-aesthetic phenomena. Mediated, integrated and read within a his-

torical process, the marginal phenomena become the places where new

revolutionary movements first appear. They thus define the pre-revolu-

tionary epochs in status nascendi.

"Out of the cinema crawled a shimmering, revue-type produc-

18. Kracauer, Die Angestellten, p. 23.

19. Kracauer, "Kult der Zerstreuung," p. 313.

20. Kracauer, "The Mass Ornament," in New German Critique 5 Spring 1975, p. 67.

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sabine Hake 157

tion..."21 Diversion is not possible without a frame for its production.

Here Kracauer takes his cues from architecture, in which a specific form

of pleasure is inscribed. The cinema, as an architectural space for stag-

ing a socio-cultural scenario, became more than a mere show-case. Re-

fining its appearance, it developed into the dominating factor for the

films it demanded and exhibited. Originally the place of crude specta-

cle, the cinema in the 1920s returned to that realm of respectability tha

it had apparently attempted to supersede. For Kracauer, and in the con

text of his disgust for all forms of rapprochement between theater an

film, the beautified movie-palaces consequently can be seen as work

against the cinema's utopian destination. This retrogressive process

takes place through the production of cinema as the "Gesamtkunstwerk

der Effekte" and facilitates its recuperation by dominant ideology. In its

aesthetic style the modern type of cinema for the masses tends towards

the cultivated splendor of surfaces. Good taste reigns, the sacred rever

berates and transfigures the production's unified look. The other strate-

gy of appropriation, aside from the architectural frame, lies in the pro-

gramming practices modelled after American forms of exhibition. Thu

the film becomes part of a sequence of various effects: of light, orchestr

music, live-number girls and impresarios. As part of a totality of effects

film - for Kracauer an a priori progressive medium through its proximi

ty to reality - is domesticated; and with it all hopes for a proletarian an

avant-garde culture are destroyed. From the glass of champagne, th

symphonic sound of real violins to the glamorous evening-gowns an

the entrance of celebrities, this concept of cinema creates a fictitious uni

ty against the background of the dispersed and fragmented life of the

city.22

For Kracauer, the inveterate movie-goer is alienated from the

phenomenological world and seeks reunification with the world of ob-

jects in the darkness of the cinema. There is indeed a logical connection

between "Cult of Diversion" and the misinterpreted realism of Theory of

Film and it can be located in the latter's subtitle "The Redemption of

Physical Reality," since it explains the desire of an imaginary spectator:

"He misses 'life'. And he is attracted to cinema because it gives him the

illusion of vicariously partaking of life in its fullness."23 Both aspects of

21. Kracauer, "Kult der Zerstreuung," p. 314.

22. Kracauer, for instance, argues that the two-dimensionality of the screen and the

three-dimensionality of all other spectacles exclude each other: "The film demands out

of itself, that the world mirrored by it shall be the only one. Every three-dimension effect

should be eliminated; otherwise film fails as an illusion." in "Kult der Zerstreuung," p.

316.

23. Kracauer, Theory of Film (New York: Oxford University Press, 1960), p. 167.

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

158 Girls and Crisis

diversion, regression and escapism, point toward woman, not just as a

metaphor, but as a visible new audience. Particularly in discussing the

emerging film culture in the 1920s, critics, including Kracauer, conde-

scendingly speak of women as the example of a lack of good taste, thus

reserving the progressive potential of diversion for man and the revolu-

tionary cause. Indeed, the utopian reading of mass culture and its spe-

cific modes of production, distribution and consumption, the central

hope in many media concepts of the 1920s (cf. Brecht's radio theory)

relies on a masculine brand of diversion. The cinema is mysteriously the

only medium that openly elicits the fear of the feminine. Thus, to speak

of diversion and to attribute it to a new and disquieting audience of

women is nothing less than an operation of displacement. However re-

pressed, fractured, deformed or disguised, the audience of the 1920s is

imagined by most critics as a female one (of women and/or of an audi-

ence made female by its forms of perception).24 This maneuver of dis-

placement corresponds to actual social change. It is indeed the city

where women break out of the traditional system of families, of course

only to integrate themselves into the army of cheap industrial labor and

to form the immediately devaluated profession of secretaries. "Girls

und Krise" (Girls and Crisis), this is how Kracauer apostrophizes the

connection between the popularity of girls' dancing troops, girls' fash-

ion and girlishness. The role of the girl was the price woman had to pay

for her demysticifation (caused by her participation in the work pro-

cess). It is possibly best described in the formal similarity of the convey-

er-belt and choreography: "... and when they [the dancers] did the same

over and over again, without ever interrupting their line, one was able to

envision an endless chain of cars gliding out of the factory halls into the

world."25 And commenting on contemporary genres, Kracauer once

implied that the popularity of the false-identity-plot among female

employees was due to their own lack of identity.

The cinema as a place of escapism becomes, in its most derogatory re-

lation to the female tearduct, the receptacle of all the aborted dreams of

female socialization. At the same time, as being one of the first public

places for a genuine female audience (perhaps a vulgarized salon of the

industrial age) the cinema, in its formative years, also embraced a utopi-

an potential: to be the place for the feminine and a place for women.26

24. Cf. Curt Morek, Sittengeschichte des Kinos or Rudolf Harms, Philosophie des Films

25. Kracauer, "Girls und Krise," in Frankfurter Allgemeing 27.5.1931.

26. In order to embrace the ambivalent aspects of woman's presence in the cinema,

Judith Mayne chooses to characterize woman as the alienated spectator in the Brechtian

sense of the exile as ultimate dialectician. cf.Judith Mayne, "The Woman at the Keyhole:

Women's Cinema and Feminist Criticism, in New German Ciique 24/25 Fall/Winter, 1981/2, p. 40.

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sabine Hake 159

With these ramifications in mind, the term Zerstreuung could well be

understood as the simultaneous repression of the feminine and its re-

turn. Kracauer and his remarks must be seen in this context. The at-

tempts of apparent complicity with modem forms of pleasure, no mat-

ter how alluring and revealing they are, need always to be measured

against the individual's self-interest, in the case of Kracauer that of an in-

tellectual whose position is questioned by the phenomena he is so eager

to study. In all his essays Kracauer evaded the impact of an audience of

women by pushing it aside through an act of disqualification, as "little

shopgirls." Thus he managed to save his cherished ideal of diversion

and intensification for the purer realms of theory. Inconsistencies in the

analysis of the culture of employees were reduced to the problem of

women's deficits.

Read as an isolated text, "The Little Shopgirls Go to the Movies"

sounds like the melancholic remarks of a cultivated bourgeois who at-

tributed the embarassing level of film production to the emergence of a

huge, specifically female audience. Kracauer's misogynist tendencies

are immediately perceivable in little stylistic ploys that unmask this out-

cry against pulp and kitsch. The series about the little shopgirls starts out

with a perfectly acceptable observation: "Society is much too powerful

to allow films other than the agreeable one. Film has to reflect society,

whether it wants it or not."27 In order to illustrate this, Kracauer reaches

down into the world of maids and shopgirls, who love, choose their

wardrobe and commit suicide. "Film story and life story usually corre-

spond to each other because typists model themselves after the exam-

ples from the screen; perhaps the most hypocritical examples are stolen

from life."28 Kracauer then defines film as society's daydream that re-

veals its secret mechanisms, the sillier and less realistic its plots are. With

the premise of defining a limited number of typical motifs, an approach

recurrent in From Caligari to Hitler, he narrates eight typical plots and the

predictable female response. Each part starts with a caption that vaguely

recalls a genre - "Nation in Arms," a war film, "The Modem Harun al

Rashid," a sentimental love story - then he gives a synopsis, barely dis-

guised in its cynicism, and concludes each time with a final judgment,

repeated in an almost identical sentence structure. (Examples of the

girls' reactions to the war film: "The little shopgirls have a hard time re-

sisting the glamor of marches and uniforms;"29 and to the love story: "If

27. Kracauer, "Die kleinen Ladenmadchen gehen ins Kino," in Das Ornament der

Masse, p. 299.

28. Ibid., p. 280.

29. Ibid., p. 287.

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

160 Girls and Crisis

the little shopgirls are approached by a strange gentleman this night,

they probably think he is one of the famous millionaires."30)

To evaluate Kracauer's equation between cinema's downfall and fe-

male taste traditionally limited to pre-aesthetic areas like diary, corre-

spondence, arts and crafts, it might be useful to turn to one of the first

sociological studies on the cinema. Already in 1914, the sociologist

Emilie Altenloh conceived a questionnaire to collect data on the class-,

age-, and gender-specific factors of movie attendance. She was the first

writer to describe the historical emergence of women as a new audience.

Although the cinema had become respectable by the time of Kracauer's

writings, his complaints are already anticipated in Altenloh's observa-

tions which are interspersed with equally sexist cliches of women as be-

ing more emotional and less intellectual. Altenloh's Soziologie des Kinos

(Sociology of Cinema) proceeds from a similar notion of diversion as the

central agency, subsuming all aspects of taste and social behavior. She

argues that both the cinema and its audience are the typical products of

a period in which bourgeois ideals of concentration and contemplation

are no longer valid as adequate gestures of aesthetic appreciation. Bore-

dom reigns, and the resulting restlessness has to be quieted with strong

stimulants: "Something has to be there to satisfy these different needs,

the desire to be distracted, to recover from the daily demands on mod-

em people, to relieve boredom and the hunger for sensation, and if the

cinema had not been invented, something else would have been in-

vented in its place."3' Altenloh also refers to other forms of popular en-

tertainment, thus discussing the cinema in the proximity of circus,

vaudeville, cafe-life rather than in opposition to the theater. Aside from

class distinctions, Altenloh's questionnnaire allows her to establish in-

trinsic correspondence between women and the specific qualities of cin-

ematic pleasure that are not always void of depreciation of her own sex:

"The female sex, of which is said that it perceives impressions purely

and emotionally in its wholeness, must be particularly prone to cine-

matic representation. Compared with that, it seems to be almost diffi-

cult for intellectual people to reenact in detail those unconnected se-

quels of events."32 The cinema, according to this early study, appeals to

people that drift along, motivated by impulses of the moment. These

people are: children and adolescents, social outsiders, in growing num-

bers employees, and finally, across all ages and classes, women. Al-

though Altenloh still focuses on the proletarian woman and her need to

30. Ibid., p. 291.

31. Emilie Altenloh, Zur Soziologie des Kinos (Jena: Diederichs, 1914), p. 93.

32. Ibid., p. 91.

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sabine Hake 161

escape from the harsh reality, she already conceptualizes the new type of

woman that is defined as a full-time consumer, integrating, unlike men

across class boundaries, the cinematic experience into a general form of

consumption. After a morning of shopping on the new boulevards with

their display windows and outdoor cafes (epitomized by streets like

Kurfiirstendamm), she attends the afternoon matinees of the shimmer-

ing movie palaces Kracauer refers to in "Cult of Diversion." There the

cinema also becomes advisor and trendsetter for the world of fashion,

manners and home design. This affluent version of the cinematic expe-

rience, embodied by the upper middle class woman but aspired to by

everyone in modern commodity society, provides the setting for a sen-

sual economy which Kracauer criticizes in his analysis of the picture pal-

aces' spatial and ritual designs.

A reading of Altenloh's observations and interviews, however, could

clarify some of the problems that accompany the implications of the

term Zerstreuung, in particular in relation to its 'Doppelgdnger,' namely

boredom. Whereas Altenloh's critical assessment of the movie theater's

attraction centers around a diversion that is desired but not achieved,

the empirical part is filled with confession of boredom as the actual

main motive for movie attendance. The working-class women ("They

go to the movies out of boredom, not out of real interest ..."33) seek es-

cape from reality, whereas the female employees seek strong stimulants

to fight a perennial boredom that is typical of their profession. Married

couples primarily go to the movies on the woman's initiative, who wants

to escape the dullness of her home. The social groups that are the least

attracted to the cinema are, according to Altenloh's study, those work-

ing in pre-industrial professions (farmers, workmen) or with strong

group affiliation (church, party). Despite the initial conceptualization of

cinema as a medium granting diversion, the actual result of Altenloh's

study points, on the contrary, to its permanent denial. In its place, bore-

dom becomes the main impulse to return to the movie theater despite

better knowledge. This is of particular importance in opposition to

Kracauer, who struggles in his essay on boredom to preserve the term's

aristocratic notions. Heide Schluipmann took up this line of thought in a

critical reading of Kracauer's early writings, thus also returning to

Altenloh's implications and showing them in a different light. She ar-

gues "The relation between film and the end of bourgeois culture is not

so much captured in the term Zerstreuung, in which, after all, capitalism

protects itself from its loss of metaphysical elevation. It is much more

captured in what are interruptions of the production process: in a

33. Ibid., p. 78.

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

162 Girls and Crisis

boredom that protests against the organization, as leisure in waiting."''34

In this context, the attempt to promote diversion as a radical concept

forfeits its progressive impact, as hoped for by Kracauer with changing

implications in his later writings. The countermovement can already be

traced in the earliest essays and leads, finally, to the didactic dismissal of

diversion. Already in a little remark in "Langeweile" (Boredom)

Kracauer advocated, along similar theoretical lines, radical boredom as

a means of self-assurance, conceived as the remedy against the cultural

crisis and as a luxury for those who still can afford it. On the one hand,

there is the motif of intensification, while on the other hand, one can de-

tect an undercurrent of aristocratic ennui and hostility towards the ba-

nality of film, radio and advertisement. Kracauer belittles the distrac-

tions of the city, which serve only to soothe its distressed inhabitants. In

this antithetical side of argumentation, Kracauer accuses all modern

media of inducing a social amnesia and reducing existence to a perma-

nent flow of shallow sensations. He complains: "One forgets oneself in

staring" and the cinema is almost accorded the powers of a vampire:

"The dark hole revives itself with the pretense of a life that belongs to no-

body and consumes everybody.""3 In opposition to this tendency,

Kracauer sets a scenario of happiness that may be regained through pro-

fessionally practiced boredom, the diversion of kings. A new paradise:

"Boredom becomes the only activity that is proper, because it remains

the sole guarantee for being in possession of an existence."36 Frieda

Grafe, in another context, suspects a similar hidden conservativism in

Kracauer's interpretation of the ornament: "But the subtext of his criti-

cism implies that he, even in the cinema, insists on the individual's old

traditional place in the center. Decorative, ornamental for him means

empty, without depth, a surface pretending plentitude."37 What is only

suggested in "Boredom" appears more often, when his writings tend

more and more to degenerate into moralistic judgments of taste. The

progressively formulated concept of diversion now turns against itself.

Kracauer begins to despise entertainment films, dismissing them pre-

cisely for their value as entertainment. In a review of a musical comedy,

for instance, he protests the expenditure of the means of production

and establishes an aesthetic and socially valiant norm of input and out-

put: "It [diversion] does not demand to be treated carefully, but wants to

express its superficiality through its style as well... "38 Discussing the

34. Heide Schltipmann, "Kinosucht" in Frauen und Film 33 October 82, p. 50.

35. Kracauer, "Langeweile," in Das Ornament der Masse, p. 322.

36. Ibid., p. 324.

37. Frieda Grafe, "Fiir Fritz Lang," in Fritz Lang (Miinchen: Hanser, 1976), p. 37.

38. Kracauer, Von Caligari bis Hitler, appendix, p. 502.

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sabine Hake 163

general film production of 1931, Kracauer criticizes the waste of ide

and capital for the production of dream images and escapist fanta

which only distract from the historically objective political pressure

Confronted with the political reaction, Kracauer returns to tradition

standards : differentiation into the serious and the light, between hi

and low culture, again diversion versus contemplation. "Over is t

time ofjazz, the girlie-show, the high-life in hotel lobbies; all that is ov

The entire culture of diversion created systematically by the film ind

try was only possible as long as the masses could be intoxicated.""39

In "Film von heute" (Film of Today) Kracauer presents his new

categories. The entertainment film, unmasked as a means of stultific

tion, is defined as an agency for distracting the audience from the pol

cal and social reality. In this regard, it performs the same ideolog

tasks as the propaganda film which, after all, does not conceal its mo

tives. Kracauer argues now: "Diversion is pleasant and possibly useful

but it turns into a leitmotif and represses all true instruction, it sacrif

its good intentions. By cheering up the somber soul, it only obfuscat

and the relaxation, provided for the audience, leads, at the same time,

blindness."40

The concept of diversion, as it appears and changes throughout

Kracauer's writings, explains many loose ends and a certain inconsistency

that is typical for his argumentative style in general. It can be interpreted as

the writer's own heterogeneous and often contradictory commitments. In

his renunciation of diversion he takes, after all, also a more political po-

sition, criticizing not the streamlined styling of the new films but their

lack of substance as the dominating characteristic of production.

Kracauer's scattered remarks on diversion and its connection to a fe-

male audience remain ambivalent, not brought to a close. Obviously,

the change in the political climate is, although here not explicitly men-

tioned, an influence. There is a moment of utopia, most present in

"Cult of Diversion," before conservative concepts gain the upper hand.

A reading of Kracauer's contributions also has to take into account its

complex references to Weimar Germany. Thus diversion oscillates be-

tween a progressive demystification and a regressive incantation of the

threatening aspects of decline and, thus, is always in danger of being

dominated by idealistic concepts of law versus order, immersion versus

distraction. Kracauer's belief in a radicalization through diversion ig-

nores precisely the regressive aspects; in so doing he also represses the

sensual side of the cinema (as preserved in the term scopophilia). Again,

39. Ibid., p. 518.

40. Ibid., p. 532.

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

164 Girls and Crisis

the position of the feminine proves to be fatal; not only to the prospects

of the theory itself, but to the possibility of changing society. Since their

integration into the economy of capitalist rationality had not yet been

perfected, women, in Kracauer's conception, simply appear more stu-

pid. These are the ruins of a distorted emotionality left behind by the

strategies of self-assertion in bourgeois society. Thus the tale of the little

shopgirls closes with a truly happy ending: "Love is stronger than mon-

ey, when money needs to buy sympathies. The little shopgirls were

scared. Now they sigh with relief."41 Such is the emotionality attributed

to women that, in fact, unveils the unredeemed promise of a society

based on human relations.

With postmodernism as the theory of ubiquituous detachment,

Kracauer's elaborations on diversion could help in establishing a histo-

ry of cinema rather than film, since the cinema resuscitates our aware-

ness of persisting social needs. The spectator in the cinema is not alone.

41. Kracauer, "Die Kleinen Ladenmdidchen... ," p. 294.

THE INSURGENT SOCIOLOGIST

The Insurgent Sociologist publishes a wide range of

articles and reviews on social, political, and economic

themes - an indispensible tool for anyone interested in the

development of radical social science.

Recent articles on:

Theories of Ideology

Marxism in American Sociology

Women in Post-Revolutionary Cuba

Socialist-Feminist Theory

Black Labor Migration

Interlocking Ownership

Subscriptions: Regular rate $15/year; Sustaining rate

$25/year; Students and unemployed $10/year; Institutions

$25/year. Send orders to The Insurgent Sociologist, c/o

Department of Sociology, University of Oregon, Eugene,

Oregon 97403, USA.

This content downloaded from

194.254.129.28 on Fri, 04 Aug 2023 07:04:42 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Hanks 1947Document3 pagesHanks 1947Nicolás GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Kracauer's Thought-Provoking Essay "The Mass OrnamentDocument9 pagesIntroduction to Kracauer's Thought-Provoking Essay "The Mass OrnamentkafrinNo ratings yet

- The Use and Abuse of Cinema: German Legacies from the Weimar Era to the PresentFrom EverandThe Use and Abuse of Cinema: German Legacies from the Weimar Era to the PresentNo ratings yet

- Avant-Garde Film: Forms, Themes, and PassionsFrom EverandAvant-Garde Film: Forms, Themes, and PassionsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Imaging the Scenes of War: Aesthetic Crossovers in American Visual CultureFrom EverandImaging the Scenes of War: Aesthetic Crossovers in American Visual CultureNo ratings yet

- The Shining Author(s) : Fredric Jameson Source: Social Text, Autumn, 1981, No. 4 (Autumn, 1981), Pp. 114-125 Published By: Duke University PressDocument13 pagesThe Shining Author(s) : Fredric Jameson Source: Social Text, Autumn, 1981, No. 4 (Autumn, 1981), Pp. 114-125 Published By: Duke University PressJACKSON LOWNo ratings yet

- Balme 13098Document18 pagesBalme 13098Patricio BarahonaNo ratings yet

- The Cinematic Sublime: Negative Pleasures, Structuring AbsencesFrom EverandThe Cinematic Sublime: Negative Pleasures, Structuring AbsencesNathan CarrollNo ratings yet

- Comics and Language: Reimagining Critical Discourse on the FormFrom EverandComics and Language: Reimagining Critical Discourse on the FormRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (6)

- Neo-Mythologism Apollo and The Muses On The ScreenDocument42 pagesNeo-Mythologism Apollo and The Muses On The ScreenvolodeaTisNo ratings yet

- Hansen Blue FlowerDocument47 pagesHansen Blue FlowerPedro Pérez DíazNo ratings yet

- The Intertwining of Memory and History in Alexander KlugeDocument21 pagesThe Intertwining of Memory and History in Alexander KlugeAmresh SinhaNo ratings yet

- Weimar Controversies: Explorations in Popular Culture with Siegfried KracauerFrom EverandWeimar Controversies: Explorations in Popular Culture with Siegfried KracauerNo ratings yet

- Anselm Kiefer - The Terror of History, The Temptation of Myth: HuyssenDocument22 pagesAnselm Kiefer - The Terror of History, The Temptation of Myth: HuyssenjgswanNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Genre Christine GledhillDocument24 pagesRethinking Genre Christine GledhillPaula_LobNo ratings yet

- Louise Milne The Broom of The System, Tramway, Glasgow, 2008Document7 pagesLouise Milne The Broom of The System, Tramway, Glasgow, 2008Louise MilneNo ratings yet

- Provided by Hochschulschriftenserver - Universität Frankfurt Am MainDocument18 pagesProvided by Hochschulschriftenserver - Universität Frankfurt Am MaintralalakNo ratings yet

- Kracauer, Siegfried - The Mass Ornament (Pg237 - 269)Document415 pagesKracauer, Siegfried - The Mass Ornament (Pg237 - 269)Thiago Brandão Peres100% (6)

- JURNAL JSTOR - Candelaria 1983 Social Equity in Film CriticismDocument8 pagesJURNAL JSTOR - Candelaria 1983 Social Equity in Film CriticismTaufik Hidayatullah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Miriam Hansen's Introduction Kracauer's "Theory of Film"Document20 pagesMiriam Hansen's Introduction Kracauer's "Theory of Film"dbluherNo ratings yet

- The Enduring Relevance of Genre in Art According to Thomas CrowDocument28 pagesThe Enduring Relevance of Genre in Art According to Thomas CrowinsulsusNo ratings yet

- La Jetee in Historical Time Torture Visu PDFDocument22 pagesLa Jetee in Historical Time Torture Visu PDFMónica ZumayaNo ratings yet

- "Ut Pictura Theoria": Abstract Painting and The Repression of Language - W. J. T. MitchellDocument25 pages"Ut Pictura Theoria": Abstract Painting and The Repression of Language - W. J. T. MitchellEric M GurevitchNo ratings yet

- Ideology as Dystopia: An Interpretation of Blade RunnerDocument15 pagesIdeology as Dystopia: An Interpretation of Blade RunnerIleana DiotimaNo ratings yet

- Anselm Kiefer's Art Explores the Terror of History and Temptation of MythDocument22 pagesAnselm Kiefer's Art Explores the Terror of History and Temptation of Mythchnnnna100% (1)

- Women at The Keyhole - MayneDocument18 pagesWomen at The Keyhole - MayneRebecca EllisNo ratings yet

- Mists of Regret: Culture and Sensibility in Classic French FilmFrom EverandMists of Regret: Culture and Sensibility in Classic French FilmRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Toscano Reviews Ranciere On TarrDocument4 pagesToscano Reviews Ranciere On Tarrtomkazas4003No ratings yet

- University of California Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Film QuarterlyDocument3 pagesUniversity of California Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Film QuarterlytaninaarucaNo ratings yet

- Duke University Press New German CritiqueDocument15 pagesDuke University Press New German CritiqueMelissa Faria SantosNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 193.225.246.20 On Wed, 10 Nov 2021 17:38:40 UTCDocument25 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 193.225.246.20 On Wed, 10 Nov 2021 17:38:40 UTCbagyula boglárkaNo ratings yet

- Consuming Distractions in Prix de Beaute PDFDocument28 pagesConsuming Distractions in Prix de Beaute PDFliebe2772No ratings yet

- The Archive Without MuseumsDocument24 pagesThe Archive Without MuseumsIsabela PinheiroNo ratings yet

- Documentary Across Platforms: Reverse Engineering Media, Place, and PoliticsFrom EverandDocumentary Across Platforms: Reverse Engineering Media, Place, and PoliticsNo ratings yet

- The wounds of nations: Horror cinema, historical trauma and national identityFrom EverandThe wounds of nations: Horror cinema, historical trauma and national identityNo ratings yet

- Film Theory RevisedDocument21 pagesFilm Theory RevisedAyoub Ait MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Film Theory RevisedDocument21 pagesFilm Theory RevisedAyoub Ait MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Elsaesser - Film Studies in Search of The ObjectDocument6 pagesElsaesser - Film Studies in Search of The ObjectEmil ZatopekNo ratings yet

- Does Film History Need A Crisis?Document6 pagesDoes Film History Need A Crisis?Dimitrios LatsisNo ratings yet

- The Intertwining of History and Memory I PDFDocument21 pagesThe Intertwining of History and Memory I PDFJorge CanoNo ratings yet

- Douglas Crimp, "On The Museum's Ruins"Document18 pagesDouglas Crimp, "On The Museum's Ruins"AnneFilNo ratings yet

- History, Textuality, Nation: Kracauer, Burch and Some Problems in The Study of National CinemasDocument13 pagesHistory, Textuality, Nation: Kracauer, Burch and Some Problems in The Study of National CinemasAnabel LeeNo ratings yet

- The Essay Film From Montaigne After MarkerDocument244 pagesThe Essay Film From Montaigne After Markeryu100% (1)

- Transcinema: The Purpose, Uniqueness, and Future of Cinema: January 2013Document10 pagesTranscinema: The Purpose, Uniqueness, and Future of Cinema: January 2013ganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

- Hutcheon1988Postmodern PDFDocument18 pagesHutcheon1988Postmodern PDFgiorgiaquaNo ratings yet

- 7 Medovi Many Meanings of BlaculaDocument22 pages7 Medovi Many Meanings of BlaculaScarlett O'HaraNo ratings yet

- The Cinematic Novel Tracking A ConceptDocument12 pagesThe Cinematic Novel Tracking A ConceptBilal B'oNo ratings yet

- The Primitive Unconscious of Modern ArtDocument27 pagesThe Primitive Unconscious of Modern ArtvolodeaTisNo ratings yet

- Foster, H, The Primitive Unconscious of Modern ArtDocument27 pagesFoster, H, The Primitive Unconscious of Modern ArtNadia BassinoNo ratings yet

- GillickDocument14 pagesGillickmiquelNo ratings yet

- Shot on Location: Postwar American Cinema and the Exploration of Real PlaceFrom EverandShot on Location: Postwar American Cinema and the Exploration of Real PlaceNo ratings yet

- Replacing ATA5567/T5557/ TK5551 With ATA5577 Application NoteDocument5 pagesReplacing ATA5567/T5557/ TK5551 With ATA5577 Application NoteM0n3No ratings yet

- STK6712BMK4: Unipolar Fixed-Current Chopper-Type 4-Phase Stepping Motor DriverDocument11 pagesSTK6712BMK4: Unipolar Fixed-Current Chopper-Type 4-Phase Stepping Motor DriverGerardo WarmerdamNo ratings yet

- Citroen c3Document3 pagesCitroen c3yoNo ratings yet

- Corn Tastes Better On The Honor System - Robin Wall KimmererDocument53 pagesCorn Tastes Better On The Honor System - Robin Wall Kimmerertristram59100% (1)

- Brand Project-Swapnil WaichaleDocument31 pagesBrand Project-Swapnil WaichaleSwapnil WaichaleNo ratings yet

- Troubleshooting GuideDocument88 pagesTroubleshooting GuideFrancisco Diaz56% (9)

- Purifying Water: Study of MethodsDocument21 pagesPurifying Water: Study of MethodsRohit Thirupasur100% (2)

- I See Fire ChordsDocument4 pagesI See Fire ChordsIm In TroubleNo ratings yet

- Copper Alloy UNS C23000: Sponsored LinksDocument2 pagesCopper Alloy UNS C23000: Sponsored LinksvinayNo ratings yet

- Trắc nghiệm phần thì trong tiếng anh tổng hợp with keysDocument3 pagesTrắc nghiệm phần thì trong tiếng anh tổng hợp with keysMs ArmyNo ratings yet

- LNG Vessels and Their Bunkering - North America: Sean BondDocument18 pagesLNG Vessels and Their Bunkering - North America: Sean BondMaximNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 11-Oct-2022Document5 pagesAdobe Scan 11-Oct-2022onkarkumarsolankiNo ratings yet

- Math10 Q2 Mod24 WritingtheEquationofaCircleandDeterminingtheCenterandRadiusofaCircle V3-1Document19 pagesMath10 Q2 Mod24 WritingtheEquationofaCircleandDeterminingtheCenterandRadiusofaCircle V3-1Bridget SaladagaNo ratings yet

- PH103 Section U Recap NotesDocument54 pagesPH103 Section U Recap NotesLuka MegurineNo ratings yet

- Aero 12ADocument2 pagesAero 12AIrwin XavierNo ratings yet

- Mobile C Arm PortfolioDocument6 pagesMobile C Arm PortfolioAri ReviantoNo ratings yet

- PublicLifeUrbanJustice Gehl 2016-1Document119 pagesPublicLifeUrbanJustice Gehl 2016-1bronsteijnNo ratings yet

- Pelton WheelDocument5 pagesPelton WheelMuhammedShafiNo ratings yet

- Hand Taps - Button Dies - Die Nuts - Screw Extractors - Holders - SetsDocument26 pagesHand Taps - Button Dies - Die Nuts - Screw Extractors - Holders - SetsQC RegianNo ratings yet

- How To Do Chromatography With Candy and Coffee FiltersDocument4 pagesHow To Do Chromatography With Candy and Coffee FiltersSuharti HartiNo ratings yet

- Audi 6 3l w12 Fsi EngineDocument4 pagesAudi 6 3l w12 Fsi EngineMarlon100% (54)

- Topics On Operator InequalitiesDocument29 pagesTopics On Operator Inequalitiesfrigyik100% (1)

- Coraline: by Neil GaimanDocument5 pagesCoraline: by Neil Gaimanfeliz juevesNo ratings yet

- Parts List - KTZ411-63Document4 pagesParts List - KTZ411-63Mahmoud ElboraeNo ratings yet

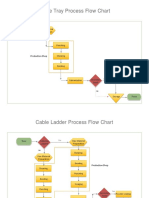

- Process Flow ChartDocument4 pagesProcess Flow Chartchacko chiramalNo ratings yet

- Galeo Wa430-6 PDFDocument1,612 pagesGaleo Wa430-6 PDFWalter100% (1)

- Quick Manual v2.3: Advanced LTE Terminal With Flexible Inputs ConfigurationDocument16 pagesQuick Manual v2.3: Advanced LTE Terminal With Flexible Inputs ConfigurationanditowillyNo ratings yet

- Monorail HC Overhead Track Scale: Technical ManualDocument30 pagesMonorail HC Overhead Track Scale: Technical ManualRicardo Vazquez SalinasNo ratings yet

- LG Rotary Compressor GuideDocument32 pagesLG Rotary Compressor Guideวรศิษฐ์ อ๋อง33% (3)

- Cobra 4 Far DynacordDocument4 pagesCobra 4 Far DynacordDaniel SfichiNo ratings yet