Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Five Things Investors Have Learned This Year

Uploaded by

Gloria GloriaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Five Things Investors Have Learned This Year

Uploaded by

Gloria GloriaCopyright:

Available Formats

archive.

today Saved from search

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/08/01/five-things-investors-have-learned-this-year 2 Aug 2023 07:39:51 UTC

no other snapshots from this url

webpage capture

All snapshots from host www.economist.com

Webpage Screenshot share download .zip report bug or abuse Buy me a coffee

Menu Weekly edition The world in brief Search Log in

Finance and economics | Discovery channels

Five things investors have learned

this year

The economy and asset prices have proved more resilient than feared

1

Io%

2.

3.

5.

image: rose wong

Aug 1st 2023 Share

S tockmarkets, the economist Paul Samuelson once quipped, have predicted nine

out of the last !ve recessions. Today they stand accused of crying wolf yet again.

Pessimism seized trading "oors around the world in 2022, as asset prices plunged,

consumers howled and recessions seemed all but inevitable. Yet so far Germany is the

only big economy to have actually experienced one—and a mild one at that. In a

growing number of countries, it is now easier to imagine a “soft landing”, in which

central bankers succeed in quelling in"ation without quashing growth. Markets,

accordingly, have spent months in party mode. Taking the summer lull as a chance to

re"ect on the year so far, here are some of the things investors have learned.

The Fed was serious…

Interest-rate expectations began the year in an odd place. The Federal Reserve had

spent the previous nine months tightening its monetary policy at the quickest pace

since the 1980s. And yet investors remained stubbornly unconvinced of the central

bank’s hawkishness. At the start of 2023, market prices implied that rates would peak

below 5% in the !rst half of the year, then the Fed would start cutting. The central

bank’s o#cials, in contrast, thought rates would !nish the year above 5% and that cuts

would not follow until 2024.

The o#cials eventually prevailed. By continuing to raise rates even during a miniature

banking crisis (see below), the Fed at last convinced investors it was serious about

curbing in"ation. The market now expects the Fed’s benchmark rate to !nish the year

at 5.4%, only marginally below the central bankers’ own median projection. That is a

big win for a central bank whose earlier, "at-footed reaction to rising prices had

damaged its credibility.

…yet borrowers are mostly weathering the storm

During the cheap-money years, the prospect of sharply higher borrowing costs

sometimes seemed like the abominable snowman: terrifying but hard to believe in.

The snowman’s arrival has thus been a double surprise. Higher interest rates have

proved all-too-real but not-so-scary.

Since the start of 2022, the average interest rate on an index of the riskiest (or “junk”)

debt owed by American !rms has risen from 4.4% to 8.1%. Few, though, have gone

broke. The default rate for high-yield borrowers has risen over the past 12 months, but

only to around 3%. That is much lower than in previous times of stress. After the

global !nancial crisis of 2007-09, for instance, the default rate rose above 14%.

This might just mean that the worst is yet to come. Many !rms are still running down

cash bu$ers built up during the pandemic and relying on dirt-cheap debt !xed before

rates started rising. Yet there is reason for hope. Interest-coverage ratios for junk

borrowers, which compare pro!ts to interest costs, are close to their healthiest level in

20 years. Rising rates might make life more di#cult for borrowers, but they have not

yet made it dangerous.

Not every bank failure means a return to 2008

In the panic-stricken weeks that followed the implosion of Silicon Valley Bank, a mid-

tier American lender, on March 10th, events started to feel horribly familiar. The

collapse was followed by runs on other regional banks (Signature Bank and First

Republic Bank also buckled) and, seemingly, by global contagion. Credit Suisse, a 167-

year-old Swiss investment bank, was forced into a shotgun marriage with its long-time

rival, ubs. At one point it looked as if Deutsche Bank, a German lender, was also

teetering.

Mercifully a full-blown !nancial crisis was averted. Since First Republic’s failure on

May 1st, no more banks have fallen. Stockmarkets shrugged o$ the damage within a

matter of weeks, although the kbw index of American banking shares is still down by

about 20% since the start of March. Fears of a long-lasting credit crunch have not come

true.

Yet this happy outcome was far from costless. America’s bank failures were stemmed

by a vast, improvised bail-out package from the Fed. One implication is that even mid-

sized lenders are now deemed “too big to fail”. This could encourage such banks to

indulge in reckless risk-taking, under the assumption that the central bank will patch

them up if it goes wrong. The forced takeover of Credit Suisse (on which ubs

shareholders were not given a vote) bypassed a painstakingly drawn-up “resolution”

plan detailing how regulators are supposed to deal with a failing bank. O#cials swear

by such rules in peacetime, then forswear them in a crisis. One of the oldest problems

in !nance still lacks a widely accepted solution.

Stock investors are betting big on big tech—again

Last year was a humbling time for investors in America’s tech giants. These !rms

began 2022 looking positively unassailable: just !ve !rms (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple,

Microsoft and Tesla) made up nearly a quarter of the value of the s&p 500 index. But

rising interest rates hobbled them. Over the course of the year the same !ve !rms fell

in value by 38%, while the rest of the index dropped by just 15%.

Now the behemoths are back. Joined by two others, Meta and Nvidia, the “magni!cent

seven” dominated America’s stockmarket returns in the !rst half of this year. Their

share prices soared so much that, by July, they accounted for more than 60% of the

value of the nasdaq 100 index, prompting Nasdaq to scale back their weights to

prevent the index from becoming top-heavy. This big tech boom re"ects investors’

enormous enthusiasm for arti!cial intelligence, and their more recent conviction that

the biggest !rms are best placed to capitalise on it.

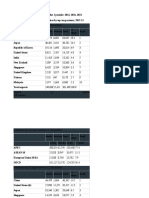

An inverted yield curve does not spell immediate doom

The stockmarket rally means that it is now

bond investors who !nd themselves

predicting a recession that has yet to arrive.

Yields on long-dated bonds typically

exceed those on short-dated ones,

compensating longer-term lenders for the

greater risks they face. But since last

October, the yield curve has been

“inverted”: short-term rates have been

above long-term ones (see chart). This is

!nancial markets’ surest signal of

impending recession. The thinking is

roughly as follows. If short-term rates are

high, it is presumably because the Fed has

tightened monetary policy to slow the

economy and curb in"ation. And if long-

term rates are low, it suggests the Fed will

eventually succeed, inducing a recession

that will require it to cut interest rates in

the more distant future.

This inversion (measured by the di$erence

between ten-year and three-month Treasury yields) had only happened eight times

previously in the past 50 years. Each occasion was followed by recession. Sure enough,

when the latest inversion started in October, the s&p 500 reached a new low for the

year.

Since then, however, both the economy and the stockmarket have seemingly de!ed

gravity. That hardly makes it time to relax: something else may yet break before

in"ation has fallen enough for the Fed to start cutting rates. But there is also a growing

possibility that a seemingly foolproof indicator has mis!red. In a year of surprises,

that would be the best one of all. 7

Share Reuse this content

SUBSCRIBER ONLY | MONEY TALKS

Expert analysis of the biggest stories in economics

and markets

Delivered to your inbox every week

example@email.com Sign up

More from Finance and economics

De"ation is curbing China’s

economic rise

The world’s second-biggest economy will

become a more distant second this year

Soaring temperatures and food

prices threaten violent unrest

The Bank of Japan jolts global Expect a long, hot, uncomfortable summer

markets

How much longer can o#cials resist interest-rate

rises?

Subscribe Keep updated

Published since September 1843 to take

Group subscriptions part in “a severe contest between

Reuse our content intelligence, which presses forward, and an

The Trust Project

unworthy, timid ignorance obstructing our

progress.”

Help and contact us

The Economist The Economist Group

About The Economist Group Economist Events Which MBA?

Advertise Economist Intelligence Working Here Executive Jobs

Press centre Economist Impact Economist Education Executive Education

Courses Navigator

Terms of Use Privacy Cookie Policy Manage Cookies Accessibility Copyright © The Economist Newspaper

Limited 2023. All rights reserved.

Modern Slavery Statement Sitemap California: Do Not Sell My Personal Information

You might also like

- FinTech Rising: Navigating the maze of US & EU regulationsFrom EverandFinTech Rising: Navigating the maze of US & EU regulationsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Great Recession: The burst of the property bubble and the excesses of speculationFrom EverandThe Great Recession: The burst of the property bubble and the excesses of speculationNo ratings yet

- Interest Rate Risk Article Jul 09Document3 pagesInterest Rate Risk Article Jul 09rpowell64No ratings yet

- Liquidity Spigot 1684333089Document27 pagesLiquidity Spigot 1684333089Alexei LeonNo ratings yet

- Impact of Covid-19 and Government Response On Capital MarketsDocument8 pagesImpact of Covid-19 and Government Response On Capital Marketsahsan habibNo ratings yet

- Inside Job documentary summary and key questionsDocument6 pagesInside Job documentary summary and key questionsJill SanghrajkaNo ratings yet

- Finance Key IssuesDocument9 pagesFinance Key IssuesDaniel Rueda RamírezNo ratings yet

- Markets Think Interest Rates Could Stay High For A Decade or MoreDocument15 pagesMarkets Think Interest Rates Could Stay High For A Decade or MoreAdrian IlieNo ratings yet

- Case BackgroundDocument7 pagesCase Backgroundabhilash191No ratings yet

- Anul III Trad Business English Part III 15 Noiembrie 2014Document6 pagesAnul III Trad Business English Part III 15 Noiembrie 2014Ana-Maria Dumitroiu0% (1)

- Compass Financial - Lincoln Anderson Commentary - Bad Banking - July 22, 2008Document6 pagesCompass Financial - Lincoln Anderson Commentary - Bad Banking - July 22, 2008compassfinancialNo ratings yet

- The Highspeed PDFDocument1 pageThe Highspeed PDFracavalNo ratings yet

- Causes of the Financial CrisisDocument2 pagesCauses of the Financial CrisisJoaquim MorenoNo ratings yet

- ProjectDocument7 pagesProjectmalik waseemNo ratings yet

- Big Freeze IIDocument5 pagesBig Freeze IIKalyan Teja NimushakaviNo ratings yet

- Risk Management Failures During The Financial Crisis: November 2011Document27 pagesRisk Management Failures During The Financial Crisis: November 2011Khushi ShahNo ratings yet

- How Destruction Happened?: FICO Score S of Below 620. Because TheseDocument5 pagesHow Destruction Happened?: FICO Score S of Below 620. Because ThesePramod KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Leveraged: The New Economics of Debt and Financial FragilityFrom EverandLeveraged: The New Economics of Debt and Financial FragilityMoritz SchularickNo ratings yet

- SubprimeDocument7 pagesSubprimeapi-3770300No ratings yet

- Why Coming Decades May Bring More Frequent Recessions and Be Good For Investors - MarketWatchDocument4 pagesWhy Coming Decades May Bring More Frequent Recessions and Be Good For Investors - MarketWatchtimNo ratings yet

- Financial Shock: by Mark Zandi, FT Press, 2009Document6 pagesFinancial Shock: by Mark Zandi, FT Press, 2009amitprakash1985No ratings yet

- Crisis FinancieraDocument4 pagesCrisis Financierahawk91No ratings yet

- Michael Burry and Mark BaumDocument13 pagesMichael Burry and Mark BaumMario Nakhleh0% (1)

- Notes On Basel IIIDocument11 pagesNotes On Basel IIIprat05No ratings yet

- Applied Philosophy-Tighten Until Something BreaksDocument13 pagesApplied Philosophy-Tighten Until Something BreaksRahul SNo ratings yet

- Financial Meltdown - Crisis of Governance?Document6 pagesFinancial Meltdown - Crisis of Governance?Atif RehmanNo ratings yet

- Financial Crises: Past, Present and Future: James J. Angel, PHD, Cfa Georgetown University Mcdonough School of BusinessDocument39 pagesFinancial Crises: Past, Present and Future: James J. Angel, PHD, Cfa Georgetown University Mcdonough School of BusinessnitikanNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id1332784Document30 pagesSSRN Id1332784farnamstreetNo ratings yet

- Q2 2020 Letter BaupostDocument16 pagesQ2 2020 Letter BaupostLseeyouNo ratings yet

- 03 Noyer Financial TurbulenceDocument3 pages03 Noyer Financial Turbulencenash666No ratings yet

- The Investment Trusts Handbook 2024: Investing essentials, expert insights and powerful trends and dataFrom EverandThe Investment Trusts Handbook 2024: Investing essentials, expert insights and powerful trends and dataRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- DiamondDocument15 pagesDiamondMaxim FilippovNo ratings yet

- The Perfect StormDocument3 pagesThe Perfect StormWolfSnapNo ratings yet

- Q2 Full Report 2020 PDFDocument24 pagesQ2 Full Report 2020 PDFhamefNo ratings yet

- Performing Credit Quarterly 3q2022Document22 pagesPerforming Credit Quarterly 3q2022Kaida TeyNo ratings yet

- The Big Short Case StudyDocument5 pagesThe Big Short Case StudyMaricar RoqueNo ratings yet

- Financial Crisis of 2007Document6 pagesFinancial Crisis of 2007absolutelyarpitaNo ratings yet

- Financial Markets Final SubmissionDocument10 pagesFinancial Markets Final Submissionabhishek kumarNo ratings yet

- Sub Prime Crisis....Document18 pagesSub Prime Crisis....vidha_s23No ratings yet

- Altman (2020)Document28 pagesAltman (2020)Juan PerezNo ratings yet

- The Credit Crisis ExplainedDocument4 pagesThe Credit Crisis ExplainedIPINGlobal100% (1)

- FI - M Lecture 7-Why Do Financial Crises Occur - PartialDocument37 pagesFI - M Lecture 7-Why Do Financial Crises Occur - PartialMoazzam ShahNo ratings yet

- Cerberus LetterDocument5 pagesCerberus Letterakiva80100% (1)

- IFR Magazine - April 11, 2020 PDFDocument102 pagesIFR Magazine - April 11, 2020 PDFChristian Del BarcoNo ratings yet

- The 2008 Financial CrisisDocument14 pagesThe 2008 Financial Crisisann3cha100% (1)

- The Future of BankingDocument6 pagesThe Future of BankingSaket ChitlangiaNo ratings yet

- 2008 Global Economic Crisi1Document8 pages2008 Global Economic Crisi1Carlos Rodriguez TebarNo ratings yet

- Putting The Air Back inDocument4 pagesPutting The Air Back inannaijoelNo ratings yet

- Sub Prime CrisisDocument7 pagesSub Prime CrisisbistamasterNo ratings yet

- 01 07 08 NYC JMC UpdateDocument10 pages01 07 08 NYC JMC Updateapi-27426110No ratings yet

- Recession Obsession: Five Key Ideas To Navigate A Well-Telegraphed DownturnDocument23 pagesRecession Obsession: Five Key Ideas To Navigate A Well-Telegraphed Downturnjyi16934673No ratings yet

- SVB Crisis and ImpactDocument1 pageSVB Crisis and Impactharshad jainNo ratings yet

- Derivatives (Fin402) : Assignment: EssayDocument5 pagesDerivatives (Fin402) : Assignment: EssayNga Thị NguyễnNo ratings yet

- The Economist (Intelligence Unit) - Finance Outlook 2023Document8 pagesThe Economist (Intelligence Unit) - Finance Outlook 2023Dainanta Yudhisthira RadiadaNo ratings yet

- EIU Finance in 2023 1Document7 pagesEIU Finance in 2023 1Harish KumarNo ratings yet

- The Absolute Return Letter 0709Document8 pagesThe Absolute Return Letter 0709tatsrus1No ratings yet

- Financial Crisis Enforcing Global Banking Reforms: A. GuptaDocument9 pagesFinancial Crisis Enforcing Global Banking Reforms: A. Guptaann2020No ratings yet

- SMB Grade 5 2018Document2 pagesSMB Grade 5 2018Miles SilabaNo ratings yet

- Cheiron PricelistDocument4 pagesCheiron Pricelistimcoolmailme2No ratings yet

- CV Nata TERBARUDocument6 pagesCV Nata TERBARUArif L Khafidhi100% (1)

- Council Tax 2019-20 GuideDocument2 pagesCouncil Tax 2019-20 GuideSteven HamiltonNo ratings yet

- CementDocument4 pagesCementafsan21100% (1)

- Relationship Between Residential Status and Incidence of TaxDocument5 pagesRelationship Between Residential Status and Incidence of Taxsuyash dugarNo ratings yet

- Email Mobile Database of Purchase Procurment Heads Sample 1Document10 pagesEmail Mobile Database of Purchase Procurment Heads Sample 1narpat kumarNo ratings yet

- Team 5: Nikhil Nag Pavithra Ramashesh Athri Rana Debnath Shalini H. SDocument26 pagesTeam 5: Nikhil Nag Pavithra Ramashesh Athri Rana Debnath Shalini H. Snikhil nagNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 3Document66 pagesChapter - 3Ram KumarNo ratings yet

- Block-1 Definition, Nature, Ethics and Scope of Public RelationsDocument85 pagesBlock-1 Definition, Nature, Ethics and Scope of Public Relationspradhumn singhNo ratings yet

- Impact & Influence of Ukraine & Russia War On TourismDocument3 pagesImpact & Influence of Ukraine & Russia War On TourismInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- PWC Payments Handbook 2023Document34 pagesPWC Payments Handbook 2023Koshur KottNo ratings yet

- CEEW CEF InvestmentTrends2021Document46 pagesCEEW CEF InvestmentTrends2021Kumar VaibhavNo ratings yet

- Passage Two: 5. Remove Your Card From The Slot. The Drawer Will Open With Receipt and Your CashDocument2 pagesPassage Two: 5. Remove Your Card From The Slot. The Drawer Will Open With Receipt and Your CashHusnul HotimaahNo ratings yet

- Export and Import Questions and AnswersDocument7 pagesExport and Import Questions and AnswersHassan IsseNo ratings yet

- John Keells Holdings PLC AR 2021 22 CSEDocument332 pagesJohn Keells Holdings PLC AR 2021 22 CSEDINESH INDURUWAGENo ratings yet

- RBI Keeps Key Policy Rates On HoldDocument15 pagesRBI Keeps Key Policy Rates On HoldNDTVNo ratings yet

- New Venture Creation Entrepreneurship For The 21st Century 10th Edition Spinelli Test BankDocument15 pagesNew Venture Creation Entrepreneurship For The 21st Century 10th Edition Spinelli Test Banknathanmelanie53f18f100% (27)

- Textile Exchange Preferred Fiber and Materials Market Report 2021Document118 pagesTextile Exchange Preferred Fiber and Materials Market Report 2021TARKAOUI OussamaNo ratings yet

- SJ Salomon International - Lagarde Predicts Recovery For Europe Late 2021Document2 pagesSJ Salomon International - Lagarde Predicts Recovery For Europe Late 2021PR.comNo ratings yet

- Crypto Signal Date Target To Buy 1st Target 2nd Target Price Done (Date) Price Trading Flat FormDocument10 pagesCrypto Signal Date Target To Buy 1st Target 2nd Target Price Done (Date) Price Trading Flat FormDinuka ChathurangaNo ratings yet

- Dhaka Stock ExchangeDocument39 pagesDhaka Stock ExchangeProtap Roy50% (2)

- Acctg122 - Chapter 1Document25 pagesAcctg122 - Chapter 1Ice James Pachano0% (1)

- Australia v1.3Document81 pagesAustralia v1.3Hà Kiều OanhNo ratings yet

- Knox Local Food SurveyDocument3 pagesKnox Local Food SurveyMadhu BalaNo ratings yet

- Month Pay TS Incr. DA HRA CCA Total CPS Tsgli GIS PT Ewf SWF I.T Net Total Sl. No. AHR ADocument3 pagesMonth Pay TS Incr. DA HRA CCA Total CPS Tsgli GIS PT Ewf SWF I.T Net Total Sl. No. AHR AMahendar ErramNo ratings yet

- Overview of The Money Supply Process: Changes in The Required Reserve Ratio, RRDocument10 pagesOverview of The Money Supply Process: Changes in The Required Reserve Ratio, RRmaria ritaNo ratings yet

- Utility Bill Template 02Document5 pagesUtility Bill Template 02dzh4422No ratings yet

- Gibbons Stamp Monthly Mess With LinkgsDocument4 pagesGibbons Stamp Monthly Mess With LinkgsbNo ratings yet

- FerraroDocument38 pagesFerrarodaniela soto gNo ratings yet