Professional Documents

Culture Documents

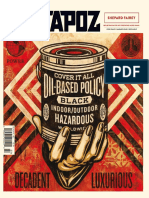

Ensayo Obey Sobre Las Pegatinas

Uploaded by

Azahara SánchezOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ensayo Obey Sobre Las Pegatinas

Uploaded by

Azahara SánchezCopyright:

Available Formats

ESSAYS

STICKER ART

Essasy stiker art

https://obeygiant.com/essays/sticker-art/

18 de abril 2023

Stickers rule. When I pause to think about it, stickers

have changed my life. It is hard to believe that paper

and vinyl with adhesive backing can do so much.

Repetition works, and stickers are a perfect medium to

demonstrate this principle. As long as stickers are being

put up faster than they weather or are cleaned, they are

accumulating. For cities, it is a constant maintenance

battle. Simple fact is, it’s a lot easier to put stickers up

than to clean them off. People also seem unable to resist

the urge to stick them on their belongings, car, stereo,

skateboard, guitar, and the list goes on. What’s on

stickers doesn’t even have to be that cool, they still

manage to make their way into every nook and cranny

on the planet.

What’s the deal with stickers anyway? This article is

supposed to be about stickers in the context of graffiti

(more clearly defined as “aerosol art”), but the

relevance of stickers extends far beyond just the graff

world. Literally defined, by Webster’s, Graffiti means an

inscription or drawing, message or slogan, made on

some public surface. Under this broad definition,

almost all stickers seen in public could be considered

graffiti.

I’m not sure whether this article is supposed to be a

more academic discussion, but I’m providing my

history with stickers because it is very relevant to my

point of view. My introduction to stickers as graffiti was

not through the aerosol art graffiti scene. I grew up in

South Carolina where graffiti was non-existent with the

exception of the usual “Darnell loves Shanice” or “Go

Bobcats.” I did however; start to notice skateboard and

punk rock stickers here and there as soon as I took

interest in these two things at the beginning of 1984.

Since my friends were into punk and skateboarding as

passing fads, only momentarily distracting them from

their paths as respectable preps, I found sticker

sightings an encouraging sign that there were more

dedicated proponents of punk and skate culture lurking

somewhere in the city. Stickers were evidence that I

wasn’t living in a total void. I wanted stickers as badges

of my culture. At first I would just buy skate stickers

and put them on my stuff. I couldn’t even figure out

how to get punk stickers, so I learned how to draw all

the band logos. Then my mom bought a copier for the

business she ran out of our house. It was on, now I

could copy graphics from the skate mags and my album

covers onto Crack n Peel and make my own stickers.

Pretty soon everything I owned was covered with them.

At the same time I was making paper-cut stencils of

skate and band logos for spray paint and silkscreen

application. These activities continued through high

school, less as a way to make art than as a way to avoid

actually having to pay for stickers and t shirts, many of

which were not available in S. C. anyway. Besides, my

parents had expressed their dislike of anything skate or

punk related and would provide no financial support for

additions to my wardrobe in these categories.

*Interesting side note: At this time, I still had not had

real contact with “wild style” graffiti, with the exception

of attending an art summer program with David Ellis,

a.k.a. SKWERM, who would go on to start the

acclaimed Barn Stormers graffiti project. At art camp,

SKWERM was obsessed with tagging on everything,

and showing off flicks of NYC and graff he’d done on

barns. I didn’t understand his passion for graff or NYC

and made fun of him by signing my name on his

message board with a bunch of arrows coming off it. He

soon explained to me that I was a “toy” and needed to

“step off”. I was amused by his behavior at the time, but

would get it later. In 1988 I moved to Providence, RI to

attend the Rhode Island School of Design. I

immediately linked up with all the punks and skaters.

Stencils and stickers were business as usual, but with

the addition of some more personalized alterations of

the graphics I would rip-off. Providence had a

tremendous art and music scene compared to what I

was used to, and stickers were everywhere. There were

tons of band stickers, political cause stickers (mostly

college activists), and most interesting to me, a few art

stickers and “hello my name is” tag stickers. A lot of the

art stickers beckoned the question “to ponder the

sticker as a means of expression and communication for

an individual, instead of just representing a band,

company, or movement. For years I had defined myself

through associations with things that represented skate

and punk culture. This path to forming an identity

appealed in high school, but did little to alleviate the

existential problem of anonymity once I had left high

school and entered into an art school environment full

of “alternative” people just like me. I liked the idea of

having my own sticker, but couldn’t think of something

clever enough to be worth executing. I looked at it

almost as seriously as getting a tattoo. I paid very close

attention to stickers and I would try to figure out who

and what was behind any sticker that I saw. I even

started photographing flyers, stickers, and other forms

of graffiti. During a museum trip to New York that

freshman year of college, I saw graffiti in risky places

that gave me new respect for the dedication of the

writers. Stickers and tags coated every surface in New

York City. I left the city inspired, but I was somehow

convinced graffiti was something you had to be born

into, like a Black or Hispanic mafia, and a pale cracker

like me could never be accepted in that culture. I did

however, think that I could make stickers and

accomplish some of the same things.

That summer I was working at a skate shop called The

Watershed. The boss liked my homemade t-shirts and

asked me to design some stickers and tees for the store.

I was amazed; people actually liked my crude “Team

Shed” designs more than the stuff my boss had made

professionally. This provided some artistic validation,

but I was still looking for my own thing. Everything fell

into place somehow when my friend Eric asked me to

teach him how to make paper cut stencils. I stumbled

upon a funny picture of Andre the Giant, and I told Eric

that Team Shed was “played” and he should make a

stencil of Andre so we could be Andre’s “posse”. He

tried to cut the image with an x-acto knife, but aborted

the mission in frustration. I finished the job and wrote,

“Andre the Giant has a Posse” on one side with his

height and weight, 7’4″, 520 lbs., on the other side. The

first Giant sticker was born, with many more to come.

The Andre stickers started as a joke, but I became

obsessed with sticking them everywhere both as a way

to be mischievous and also put something out in the

world anonymously but that I could call my own. Just

as I had been made curious by many of the many

stickers I’d seen, I now had my own sticker to taunt

and/or stimulate the public. The sticker takeover of

Providence only took that summer. The next fall the

local indie paper printed a picture of the sticker offering

a reward to the person who could reveal its source and

meaning. The sticker campaign had worked so quickly

locally, that I decided to strike out for Boston and New

York, both within driving distance. The ball had begun

to roll but the amazing thing is that I almost lacked the

self-confidence to try to put something of my own out

there. I didn’t even think I could make an impact in

Providence and it is somewhat of a fluke that the Giant

sticker stimulated me to try. However, once the first

domino fell, I was addicted and had my sights set on

world domination through stickers.

It amazed me just how liberating and easy stickering

was. At first I would just run off a few hundred stickers

a week at a copy center, using their sticker material.

Then I figured out that I could get sticker material at an

office supply store for half the price. Paper stickers were

good for indoor use, a nightmare to remove, but

weathered too quickly outdoors. I was taking some

screen-printing classes, so I decided to look into making

vinyl stickers. I bought vinyl ink and vinyl from a screen

print supply wholeseller in Boston. The vinyl ink was ill

toxic, but by printing them myself, the vinyl stickers

worked out to be way cheaper than the paper ones. I

also liked the confusion factor with having a low-fi

image printed on the more professional vinyl material.

Every sheet of stickers I printed felt like I was making

the world a little smaller, I mean, all those stickers were

gonna end up somewhere. The only thing that sucked

was cutting the sheets into individual stickers. At first I

used scissors, but then I gave in and bought a paper

cutter and would just watch a movie and cut stickers.

This process of production continued from ’89 to ’96,

yielding over a million hand printed and cut stickers.

When I moved to California, I decided I needed to keep

the brain cells I had left, so I stopped printing with vinyl

ink and started sending my stickers out to a printer.

As my production methods improved, so did my

distribution. I began sending stickers to several

enthusiastic friends who had caught sticker fever.

As my production methods improved, so did my

distribution. I began sending stickers to several

enthusiastic friends who had caught sticker fever. Some

writers only want their stickers to track their actual

footsteps. For example, I printed some stickers for Phil

Frost and he got mad at me for putting them up for

him. Phil got a call from Twist reporting that he’d seen

some Frost stickers in San Francisco and asked if he’d

been there. Phil figured I’d put them up and told me he

only wanted his stickers on the street as a document of

where he’d traveled. I just wanted my stickers to go as

far and wide as possible, so I would supply stickers to

my friends who lived all over the country. I also began

to run cheap classified ads in Slap skateboard magazine

and the punk zine Flipside. The ads just had my images

and said, “Send a self-addressed stamped envelope for

stickers and the lowdown.” I was building a great

grassroots network of people who wanted stickers. The

only problem was that I was losing money on all of the

stickers and ads. The stickers were always intended as

an art project, and part of the charm was that there was

nothing for sale, but I had to make some money back to

keep producing. My solution was to ask for a mandatory

donation of five cents per sticker (a price I basically

maintain for black and white stickers to this day) and to

produce some t-shirts to sell. That’s how my humble

sticker and t shirt business got started. Almost every art

and financial opportunity in my life has stemmed from

my stickers and their poster and stencil relatives.

So, there’s more to my specific experience with stickers

than that, but I’ve also developed a general overview of

the sticker scene and made friends along the way who

have opinions about stickers. Because I’m not an O.G.

graff guy, I had to get the lowdown on stickers in graff

prior to my introduction to the scene in 1989. Who

better an authority to call than Zephyr, one of the

pioneers of wild style graffiti and the man behind the

“Wild Style” movie logo letters. According to Zephyr, no

one in New York bombed stickers back in the day

because piecing and tagging were so much easier then.

Plus, the focus was more on the huge pieces on the

outsides of trains. Zeph says the first stickers that

started popping up a lot were commercially offset

printed stickers that said “Why not?” He says, “The

stickers were annoying but effective. The guy would put

them up all over the runners of the trains. Ask Lee or

any of the writers from that era They’ll remember, Why

not? Even if writers were irritated at first by sticker

guys jocking their spots, eventually stickers became

part of the writer’s arsenal. Zephyr credits Revs and

Cost with really demonstrating the power of the sticker

(and paste-up) mediums in New York, and I would

agree with him. Revs and Cost had mass-produced

stickers and Xeroxed flyers on almost every crosswalk

box in the city between 1991 and 1995. Their level of

coverage was unprecedented, and their irritation to the

city changed clean-up policies, insuring that such

domination could never be achieved again. Revs and

Cost approached promoting themselves through

stickers seemingly less as typical graffiti than as a

brand. They used bold, readable, no-frills type. The

technique may not have been that stylish, but it was

very effective, earning Revs and Cost the distinction of

being two of the only writers whose names were well

known outside of the graffiti community. My approach

definitely takes cues from Revs and Cost, as well as the

worlds of advertising and propaganda. I learned from

Revs and Cost that simplicity and ubiquity can cut

through all the visual noise and urban clutter. I

attempted to take things one step further by using

consistent color stories and icons on multiple sticker

designs to allow people to experience a lot of repetition

mixed with a little diversity to keep things intriguing.

HERE IS WHAT A

FEW OTHER

RELATIVE

AUTHORITIES HAVE

TO SAY ABOUT

STICKERS:

Dalek – Graffiti writer, known for his space

monkeys

#1 Stickers are a great way to meet people.

#2 I like stickers because they are fun to slap all over

the place.

#3 It is a great way to get your imagery out all over the

world.

#4 People love stickers.

#5 I like to collect stickers. They are like toys…or

trading cards.

#6 It’s like getting up.

#7 They look good in bathroom stalls.

#8 They are easier to carry about than a can of flat

black.

#9 I just want to be like Shepard Fairey.

#10 Beats wheat pasting.

#11 They are great for taping up boxes.

#12 Can be used to get the lint off of my black shirts.

Giant One – Graffiti writer and tattoo artist

“I see stickers as one of the many mediums I can use to

get up. The main reason I’ve always liked them is the

fact that I can put them up during the day without

much hassle. They’re also nice because they’re generally

small and quick to apply. I certainly don’t think it’s

important for writers to make stickers, but it can be a

fun medium. Twist made great stickers. Bob Licky

stickers are legendary. Shygirl put up a lot of nice

stickers in SF. Geso used to make big stickers out of a

few smaller ones, which I always thought was a great

idea. I put a few hundred stickers in Japan last week.

BNE was running Tokyo with his stickers. I saw lots of

Andre the Giant stickers too, as expected”.

Roger Gastman – Graffiti writer and

publisher of While You Were Sleeping magazine.

From a graffiti writers stand point. “Stickers are just

another tool in a graffiti writer’s arsenal. Another

medium that works on all most any surface. My sticker

captures the eye of the average person that might not

notice your tags and throw-ups.” from a marketing

stand point “Branding is the most important thing for a

company. It doesn’t matter if the company is a start up

or has been around for 100 years. Logo and name

recognition is invaluable. Stickers create a very

inexpensive and easy way to get that done.”

Dave Kinsey – Artist and graphic designer,

partner in BLKMRKT DESIGN.

“I like stickers because they leave a mark that can affect

a persons mood, cause thought, and inspire a reaction. I

like that my stickers become part of the movement of

the street, absorbed by the population.”

CONCLUSION

Having talked to several people, the general consensus

was that stickers are cheap, effective, and easier and

less risky to put up than tags, throw-ups, etc… However,

opinions differ drastically as to what sticker techniques

are “keepin’ it real”. Some people feel that just like

racking paint, stickers should be stolen. Whether it’s

taking priority mail stickers from the post office, labels

from FedEx or the airlines, or lifting “Hello my name is”

joints from office supply stores, stickers can be acquired

with the only cost being a potential shoplifting record. I

prefer to take my risks installing the actual art, but for

some people shoplifting is just part of the art of getting

over. A lot of graff purists also feel that every sticker

needs to be hand drawn and that printing stickers is

cheating. People like Twist and Zephyr have printed

their own variations of the “Hello my name is” sticker;

Twist’s being an oversized version, Zephyr’s saying, “o

hell my name is”, but they still hand tagged each

sticker. Other people merely use the “Hello my name is”

template as a stylistic nod to graffiti iconography. Jest,

for example, produces a “Who the fuck is jest” screen-

printed sticker which uses old English text where the

tag would normally go. Jest has put his time in, and

doesn’t have to prove his hand style by tagging every

sticker. Some people, like Giant One, just consider

making individual stickers an art form. Giant says,

“Even when I’m just tagging on stickers, I take the time

to make it tight. If I fuck up a tag I throw it in the trash.

Everything I put up on the street should maintain that

level of technical quality, from stickers to wild styles.”

The game with graff is balancing getting up like mad,

with a flavorful delivery. It could be argued that even if

hand made stickers have the flavor, it’s too time

consuming to make enough of them to really crush it.

Some dedicated individuals have proven this incorrect.

Twist always had San Francisco and any other city he

spent more than a couple days in, on handmade sticker

lockdown, not to mention tags and pieces. Pez, a bike

messenger, has crushed every city he’s lived in with tag

stickers. Serch One, Cult crew LA , has a unique method

of using spray paint and stencils with hand tagged

accents on his stickers. His stickers are more up in

every part of Los Angeles than anyone else, graffiti or

commercial. I met him once and asked him how he did

it. He said, “I take the bus.”

The art of stickers isn’t just about what is on them, but

also how they are integrated into the environment. The

most common placement is poles and crosswalk boxes

at eye level. These are also the fastest places to be

cleaned. Climbing a couple feet higher really weeds out

the city workers and vigilante citizens who aren’t

dedicated to their jobs. Slightly bigger stickers are great

for these high spots. Necessity is the mother of

invention, right? I got so sick of my stickers being

peeled that I looked into the kind of vinyl that the

government uses for registration stickers so they can’t

be stolen off of license plates. The stuff is called

destructible vinyl and flakes off in teeny pieces when

you try to peel it. It costs about twice as much but is

very worth it in some cleaner cities. People have come

up with other great ideas like the tags on the adhesive

side of the sticker stuck on the inside of newspaper

boxes facing out. Making stickers that are camouflaged

keeps them running too. In New York, locksmiths put

small contact info stickers in all the doorways. ESPO

made some of his own that blend right in, to most of the

public, but stand out to writers. I have made take offs

subverting the typical “You are under surveillance”

stickers. They look so official; they usually stay up, even

in conspicuous places. I also made fake California

Department of Weights and Measures stickers like the

ones that go on all the gas pumps. They only change

them once a year. The possibilities with sticker

placement are endless.

The fact is, if you want to make stickers but aren’t, then

you’re just lazy. Hand drawn stickers are time

consuming but free. Photocopied stickers can be made

in small quantities, I used to get my fix just making a

couple bucks worth at a time. Offset printed stickers on

a roll with standardized shapes are super cheap if you

do a bunch of them. Screen printed stickers have

expensive set-up costs, but if you split up a sheet with

friends and make only square or rectangular shapes

that don’t have to be die cut, you can bring the cost

down per person, especially when you run volume. Ask

the printers about volume price-breaks. In my opinion,

stickers are the most effective promotional tool possible

for the price. Don’t sleep on ‘em.

Shepard Fairey

May 2003

Published in Graphotism Magazine

You might also like

- Affiti Magazine Issue 18 Liquidfile PreviewDocument6 pagesAffiti Magazine Issue 18 Liquidfile PreviewBinho FerreiraNo ratings yet

- The Chalk Art Handbook: How to Create Masterpieces on Driveways and Sidewalks and in PlaygroundsFrom EverandThe Chalk Art Handbook: How to Create Masterpieces on Driveways and Sidewalks and in PlaygroundsNo ratings yet

- Art of Yarn Bombing: No Pattern RequiredFrom EverandArt of Yarn Bombing: No Pattern RequiredRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Crochet Creatures of Myth and Legend: 19 Designs Easy Cute Critters to Legendary BeastsFrom EverandCrochet Creatures of Myth and Legend: 19 Designs Easy Cute Critters to Legendary BeastsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- GOLD Graffiti Magazine, No. 4Document31 pagesGOLD Graffiti Magazine, No. 4Flavian Take100% (4)

- The Art of Defiance: Graffiti, Politics and the Reimagined City in PhiladelphiaFrom EverandThe Art of Defiance: Graffiti, Politics and the Reimagined City in PhiladelphiaNo ratings yet

- Are You The Parent of A TaggerDocument9 pagesAre You The Parent of A TaggerSophie O'hareNo ratings yet

- Fry's Ties: The Life and Times of a Tie CollectionFrom EverandFry's Ties: The Life and Times of a Tie CollectionRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Duct Tape: 101 Adventurous Ideas for Art, Jewelry, Flowers, Wallets, and MoreFrom EverandDuct Tape: 101 Adventurous Ideas for Art, Jewelry, Flowers, Wallets, and MoreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- GraffitiDocument30 pagesGraffitiAhammed AslamNo ratings yet

- And if You Gaze Into the Garbage Pail, the Garbage Pail Also Gazes Into You: The Library of Disposable Art, #6From EverandAnd if You Gaze Into the Garbage Pail, the Garbage Pail Also Gazes Into You: The Library of Disposable Art, #6No ratings yet

- GOLD Graffiti Magazine, No.3Document25 pagesGOLD Graffiti Magazine, No.3Flavian Take100% (1)

- Summer 2008 / Pdfmag #2Document66 pagesSummer 2008 / Pdfmag #2dubiluj100% (2)

- What It Is, Materials To Use and Starter Tips For The Urban Sketcher On The GoDocument21 pagesWhat It Is, Materials To Use and Starter Tips For The Urban Sketcher On The GoParnassus Parnassus73% (11)

- The Art of Urban Sketching - Drawing On Locatio CompressedDocument324 pagesThe Art of Urban Sketching - Drawing On Locatio Compressedquest50% (2)

- With My Hands: Poems About Making ThingsFrom EverandWith My Hands: Poems About Making ThingsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Art Quilt Maps: Capture a Sense of Place with Fiber Collage—A Visual GuideFrom EverandArt Quilt Maps: Capture a Sense of Place with Fiber Collage—A Visual GuideRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Creative Cosplay: Selecting & Sewing Costumes Way Beyond BasicFrom EverandCreative Cosplay: Selecting & Sewing Costumes Way Beyond BasicRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Simple NewsletterDocument4 pagesSimple Newsletterapi-351281474No ratings yet

- Centurion Collective Brand OutlineDocument26 pagesCenturion Collective Brand OutlineCenturion CollectiveNo ratings yet

- 2023 Invisible Thoughts by Chris RawlinsDocument30 pages2023 Invisible Thoughts by Chris RawlinsJuan K Merlos67% (3)

- The True History of Airwalk: Interview With Sinisa EgeljaDocument8 pagesThe True History of Airwalk: Interview With Sinisa EgeljaJose IrulaNo ratings yet

- The Complete Book of Silk Screen Printing ProductionFrom EverandThe Complete Book of Silk Screen Printing ProductionRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- A Master's Guide to Building a Bamboo Fly Rod: The Essential and Classic Principles and MethodsFrom EverandA Master's Guide to Building a Bamboo Fly Rod: The Essential and Classic Principles and MethodsNo ratings yet

- The Big Book of Realistic Drawing Secrets - Easy Techniques For Drawing People, Animals and More (PDFDrive)Document306 pagesThe Big Book of Realistic Drawing Secrets - Easy Techniques For Drawing People, Animals and More (PDFDrive)Win certo100% (1)

- A PLACE TO SEE AND BE SEEN: MY SHOP ON MADISON AVE AND ITS STORIESFrom EverandA PLACE TO SEE AND BE SEEN: MY SHOP ON MADISON AVE AND ITS STORIESNo ratings yet

- The Underwater Museum: The Submerged Sculptures of Jason deCaires TaylorFrom EverandThe Underwater Museum: The Submerged Sculptures of Jason deCaires TaylorNo ratings yet

- Street Art & The Splasher: Assimilation and Resistance in Advanced CapitalismDocument51 pagesStreet Art & The Splasher: Assimilation and Resistance in Advanced CapitalismJames CockroftNo ratings yet

- Shepard Fair EyDocument31 pagesShepard Fair EyIngrid MaschekNo ratings yet

- Intro To Modern & Contemporary Art Course 1 Class 7 & 8Document2 pagesIntro To Modern & Contemporary Art Course 1 Class 7 & 8JasonKartezNo ratings yet

- FinaladprojectDocument16 pagesFinaladprojectapi-252238540No ratings yet

- Fairey v. AP ComplaintDocument31 pagesFairey v. AP ComplaintBen Sheffner100% (1)

- Juxtapoz Art & Culture Magazine - July 2014 USADocument132 pagesJuxtapoz Art & Culture Magazine - July 2014 USAFelipe100% (2)

- Graffiti - Is It ArtDocument5 pagesGraffiti - Is It Artapi-496239023No ratings yet