Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Abstract

Abstract

Uploaded by

Manuel Mesquita0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views2 pages1) Editing music found only in manuscript form is difficult, particularly regarding ornaments which composers had varying intentions about including.

2) Bach wrote out many ornaments himself as he did not trust others to embellish his pieces properly.

3) Overly abundant ornamentation became fashionable in the late 18th century but Bach's own manuscripts were sparsely ornamented, suggesting later additions are questionable.

4) Fermatas were generally not intended to be ornamented but to designate longer note duration. Limited variation was acceptable but large numbers of ornaments went against early commentators' views.

Original Description:

Original Title

2. Abstract

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document1) Editing music found only in manuscript form is difficult, particularly regarding ornaments which composers had varying intentions about including.

2) Bach wrote out many ornaments himself as he did not trust others to embellish his pieces properly.

3) Overly abundant ornamentation became fashionable in the late 18th century but Bach's own manuscripts were sparsely ornamented, suggesting later additions are questionable.

4) Fermatas were generally not intended to be ornamented but to designate longer note duration. Limited variation was acceptable but large numbers of ornaments went against early commentators' views.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views2 pagesAbstract

Abstract

Uploaded by

Manuel Mesquita1) Editing music found only in manuscript form is difficult, particularly regarding ornaments which composers had varying intentions about including.

2) Bach wrote out many ornaments himself as he did not trust others to embellish his pieces properly.

3) Overly abundant ornamentation became fashionable in the late 18th century but Bach's own manuscripts were sparsely ornamented, suggesting later additions are questionable.

4) Fermatas were generally not intended to be ornamented but to designate longer note duration. Limited variation was acceptable but large numbers of ornaments went against early commentators' views.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

Editorial Decisions For Ornaments In Bach’s Works

An abstract on Beverly Jerold’s article

Preparing an edition of music found only in manuscript form is a difficult

process. Regarding ornaments, for example, most of us believe that performers are

expected to add embellishments to a composition. But while some composers wanted

it, others, in fact, did not. Perspectives like Johann Adolf Scheibe’s show us that the

player is not at liberty to alter pieces already embellished by the composer. However,

that liberty applies when the piece is meant for the soloist to show his skill and

invention. It is, therefore, important to know how to distinguish one from the other, in

order to know when and when not to embellish. A similar opinion was also left

written by J.S. Bach’s contemporary, Johann Matheson.

The author continues, saying that Bach wrote a large quantity of embellishment in

standard note values, once he, as other major composers, didn’t trust others to

embellish his pieces.

It is also true that a fashion for excessive over decoration spread through much of

Europe, in the second half of the eighteenth century. A good example of this practice

is the Trio in D minor (BWV 583), for which we know the existence of three

manuscripts. Two of them were probably written around 1800, and have abundant

embellishment; the third and earliest one contains many fewer ornaments, which puts

it in agreement with the most reliable manuscripts for other Bach works. The author

further states that “Bach’s autograph manuscripts are generally lightly, but adequately

supplied with ornament symbols. When an exception occurs, it is probable that the

ornaments are later accretions.” The opinion of many eighteenth-century

commentators is that adding too much ornaments only weakens and obscures their

beauty” (of the melodic lines), “making the ornaments the focus of attention.”

Also in variants of the Passacaglia (BWV 582) and the Canzona (BWV 588) we

can find “immoderate ornaments”; 48 bars in the Passacaglia and the whole piece in

the Canzona. Through studying the manuscripts, it is believed that such ornaments

might have been added later, although we find ourselves in the speculative field.

Dietrich Kilian, for instance, referring to this Passacaglia, observes that “the

authenticity of these ornaments therefore appears questionable.” However, the author

states that “the most reliable manuscripts for the Passacaglia show no trace of

overloaded embellishment.”

Regarding fermatas and whether they should or should not be embellished, Jerold

comes to the conclusion that even after Bach’s death, during the galant period, “most

fermatas were not intended to be embellished, but simply served to designate where a

note should be held longer than usual.”

A limited degree of variation in the placement and number of ornaments was

permissible. However, large numbers of ornaments were not acceptable anymore,

many early commentators say. Johann Georg Sulzer states the following: “It is not

enough to know how to make ornaments in the most graceful and convincing manner,

the main factor is their judicious placement. They should not tickle the ear or show

the skill of the singer/player, but raise the level of feeling. Foolish players apply them

everywhere, thereby inspiring only boredom.”

NBA published two versions of Bach’s Sinfonia no. 5, one with no ornamentation,

except for a trill, and other heavily ornamented, added a later date to the autograph of

the Inventions and Sinfonias. These ornamental additions have always been assumed

by modern editions to be from Bach himself, which is highly unlikely, once this small

notes, trills and turns are completely atypical elements of his practice.

Concerning Bach’s organ works, there are no original autographed documents,

only manuscripts whose later owners may have added their own ornaments. In the

Toccata in F Major (BWV 540), for example, NBA’s edition included a large number

of ornaments and a “good half of them are found only in the later, more questionable

manuscripts, and are not essencial to good performance.” In the author’s opinion, “it

would be helpful to bracket all the ornaments found only in the later manuscripts and

add an explanatory footnote. (...) early sources recommend very sparing use of

ornaments.”

It was usual that composers varied their ornamentation: a repetition/variant

measure with a short trill might replace a mordent, for example. It used to be a matter

of substitution instead of addition.

Beverly Jerold concludes, explaining that “modern editions in general are

inclined to include a substantial amount of ornamentation not found in the original

manuscript or edition, but in either other manuscripts or annotations to various copies

of the edition, (...) thus, ending up with many more ornaments than any other source.

(...) With works by composers like Bach, we might want to recall Scheibe’s words to

the virtuosos; the most praiseworthy quality, he says, is being “content with what the

composer has written”.”

You might also like

- Alenkor Cuerpo Base MiniDocument7 pagesAlenkor Cuerpo Base MiniLupita Cruz88% (8)

- Analysis BWV 1034Document34 pagesAnalysis BWV 1034Cristian Álvarez100% (4)

- Bach-Sitkovetsky - Goldberg Variations, BookletDocument17 pagesBach-Sitkovetsky - Goldberg Variations, BookletEloy Arósio0% (2)

- Peter Williams The Organ Music of J S Bach PDFDocument636 pagesPeter Williams The Organ Music of J S Bach PDFGeovany Cid Bonilla100% (14)

- Fence Post Cactus Pattern: DecreaseDocument6 pagesFence Post Cactus Pattern: DecreaseJuliaNo ratings yet

- Sonajero GrinchDocument12 pagesSonajero GrinchKaritoJimenez100% (10)

- Details Trims Forecast A W 22 23Document19 pagesDetails Trims Forecast A W 22 23paula venancioNo ratings yet

- Counterpoint, Texture and Rhythmic AspectsDocument3 pagesCounterpoint, Texture and Rhythmic AspectsRachel LauNo ratings yet

- J.S. Bach's Sonatas For Violin and Cembalo and The Development of The Duo Sonata, by G. OyenardDocument18 pagesJ.S. Bach's Sonatas For Violin and Cembalo and The Development of The Duo Sonata, by G. OyenardNatsuko OshimaNo ratings yet

- 1975 Kochevitsky Performing Bach's Keyboard Music-Embellishments-Parts V VIDocument17 pages1975 Kochevitsky Performing Bach's Keyboard Music-Embellishments-Parts V VIBruno Andrade de BrittoNo ratings yet

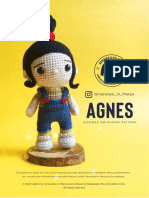

- Agnes Am I Guru Mi PatternDocument7 pagesAgnes Am I Guru Mi PatternEunice100% (8)

- Anne Leahy - BWV 998 A Trinitariam Statement or Faith PDFDocument19 pagesAnne Leahy - BWV 998 A Trinitariam Statement or Faith PDFgiovannigaianiNo ratings yet

- Bach's Prelude, Fugue and Allegro For Lute (BWV 998) : A Trinitarian Statement of Faith? A LDocument19 pagesBach's Prelude, Fugue and Allegro For Lute (BWV 998) : A Trinitarian Statement of Faith? A LFlorian007No ratings yet

- Heinrich Nikolaus Gerber'sDocument22 pagesHeinrich Nikolaus Gerber'sPerez Zarate Gabriel MarianoNo ratings yet

- The secrets of the hidden canons in J.S. Bach's masterpiecesFrom EverandThe secrets of the hidden canons in J.S. Bach's masterpiecesNo ratings yet

- Leslie D Paul (1953)Document9 pagesLeslie D Paul (1953)Dimitris ChrisanthakopoulosNo ratings yet

- Bach As TranscriberDocument9 pagesBach As TranscriberAlzbeta_Filipova100% (1)

- Anne Leahy Bach ArticleDocument19 pagesAnne Leahy Bach ArticleLewis DunsmoreNo ratings yet

- Flute and BachDocument36 pagesFlute and BachMeyah IntiNo ratings yet

- The Baroque German Violin BowDocument61 pagesThe Baroque German Violin BowRoyke JR100% (1)

- Fabian TowardsaPerfHistory UNSWorksDocument29 pagesFabian TowardsaPerfHistory UNSWorksPaulo NogueiraNo ratings yet

- Marshall A Reconsideration of Their Authenticity AndChronology 1979Document37 pagesMarshall A Reconsideration of Their Authenticity AndChronology 1979ipromesisposi100% (1)

- FL 0321 Oleskiewicz Bach Partita BWV1013Document36 pagesFL 0321 Oleskiewicz Bach Partita BWV1013Orlin ZlatarskiNo ratings yet

- Motets HofmannDocument25 pagesMotets HofmannChristopher AspaasNo ratings yet

- Hom-Kuhnle - Rediscovered Manuscript of J. S. BachDocument22 pagesHom-Kuhnle - Rediscovered Manuscript of J. S. Bachverba3No ratings yet

- Sonatas and Partitas For Solo ViolinDocument15 pagesSonatas and Partitas For Solo ViolinRodrigo0% (1)

- Bach - 6a.embellishments IDocument5 pagesBach - 6a.embellishments IPailo76No ratings yet

- BWV 998 TrinityDocument19 pagesBWV 998 TrinityRobbie ChanNo ratings yet

- BACH - Concierto Italiano PDFDocument22 pagesBACH - Concierto Italiano PDFspinalzoNo ratings yet

- "Bach Interpretation: Articulation Marks in Primary Sources of J. S. Bach." by John ButtDocument6 pages"Bach Interpretation: Articulation Marks in Primary Sources of J. S. Bach." by John ButtPink Josephine100% (1)

- Partita in A Minor For Solo Flute (Bach)Document3 pagesPartita in A Minor For Solo Flute (Bach)Eugenios Anastasiadis50% (2)

- 01 AlvezDocument14 pages01 AlvezJan ČurdaNo ratings yet

- A Measured Approach To J.S.bachDocument10 pagesA Measured Approach To J.S.bachevaNo ratings yet

- Bach Goldberg Variations PaperDocument3 pagesBach Goldberg Variations Paperll77ll44ll33No ratings yet

- BWV1007 1012 RefDocument15 pagesBWV1007 1012 RefjojojoleeleeleeNo ratings yet

- Music History EssayDocument5 pagesMusic History EssayJoshua HarrisNo ratings yet

- J.S. Bach's Sonatas and Partitas For Violin Solo: 24 - American String Teacher - May 2011Document5 pagesJ.S. Bach's Sonatas and Partitas For Violin Solo: 24 - American String Teacher - May 2011nanoNo ratings yet

- Bach - 3.articulationDocument6 pagesBach - 3.articulationPailo76No ratings yet

- The Toccatas: Mahan EsfahaniDocument20 pagesThe Toccatas: Mahan EsfahaniPaul DeleuzeNo ratings yet

- Brandenburg Lecture For ISB 2007. Peter McCarthyDocument14 pagesBrandenburg Lecture For ISB 2007. Peter McCarthyEvangelosNo ratings yet

- My Turn - Bowing Bach's Suites (AST)Document3 pagesMy Turn - Bowing Bach's Suites (AST)Jeffrey SolowNo ratings yet

- Klavierwerke I & Ii: Henry Purcell (1659 - 1695)Document38 pagesKlavierwerke I & Ii: Henry Purcell (1659 - 1695)MUSTAFA ABBAS ALINo ratings yet

- Bach Interpretation Articulation Marks in Primary Sources of J.Document6 pagesBach Interpretation Articulation Marks in Primary Sources of J.Clément CHERENCQNo ratings yet

- IMPORTANTDocument3 pagesIMPORTANTAndres RiverosNo ratings yet

- C P E Bach Resources - Autobiography-EnglishDocument12 pagesC P E Bach Resources - Autobiography-EnglishJuozas RimasNo ratings yet

- CPEBach BookletDocument32 pagesCPEBach BookletMiguel100% (1)

- Senior Recital: A Performance of Works by Bach, Beethoven, and BartokDocument14 pagesSenior Recital: A Performance of Works by Bach, Beethoven, and BartokElia RackovskyNo ratings yet

- C.P.E. Bach and The Early Sonata FormDocument22 pagesC.P.E. Bach and The Early Sonata Formwei wu100% (1)

- Performing Bach's Cello SuitesDocument2 pagesPerforming Bach's Cello SuitesJeffrey Solow100% (4)

- Music - Johnathan GodfreyDocument9 pagesMusic - Johnathan GodfreyalmamigranteNo ratings yet

- Johann Sebastian Bach Research PaperDocument7 pagesJohann Sebastian Bach Research Paperikrndjvnd100% (1)

- Yoyo Zhou: Bach Institute, Vol. 12, No. 2 (1981) : 11-19Document3 pagesYoyo Zhou: Bach Institute, Vol. 12, No. 2 (1981) : 11-19Yoyo ZNo ratings yet

- J.S. Bach: The Well Tempered Clavier Remarks On Some of ItDocument33 pagesJ.S. Bach: The Well Tempered Clavier Remarks On Some of ItUno de MadridNo ratings yet

- 6 PartitasDocument4 pages6 Partitassathian3No ratings yet

- Essential Bach Choir - CH 1: IntroductionDocument6 pagesEssential Bach Choir - CH 1: IntroductionAaron100% (1)

- Bach Preludes Chopin's EtudesDocument18 pagesBach Preludes Chopin's EtudesLandini Carlo Alessandro100% (4)

- The Tardy Recognition of J.S. Bachs Sonatas and Partitas For VioDocument7 pagesThe Tardy Recognition of J.S. Bachs Sonatas and Partitas For VioRodrigo PozoNo ratings yet

- Bach Art of Fugue Prog NotesDocument3 pagesBach Art of Fugue Prog NotesSteve KatongoNo ratings yet

- Reviewed Work(s) Bach, Handel, Scarlatti Tercentenary Essays by Peter WilliamsDocument4 pagesReviewed Work(s) Bach, Handel, Scarlatti Tercentenary Essays by Peter WilliamsJavier Vizcarra PintoNo ratings yet

- The Influence of The Unaccompanied Bach Suites PDFDocument9 pagesThe Influence of The Unaccompanied Bach Suites PDFricard.genovaNo ratings yet

- The Baroque ConcertoDocument9 pagesThe Baroque ConcertoNicholasNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Johann Sebastian BachDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Johann Sebastian Bachyqxvxpwhf100% (1)

- The Dance of Death Exhibited in Elegant Engravings on Wood with a Dissertation on the Several Representations of that Subject but More Particularly on Those Ascribed to Macaber and Hans HolbeinFrom EverandThe Dance of Death Exhibited in Elegant Engravings on Wood with a Dissertation on the Several Representations of that Subject but More Particularly on Those Ascribed to Macaber and Hans HolbeinNo ratings yet

- States and Handicrafts PPTDocument54 pagesStates and Handicrafts PPTRica Ella DomingoNo ratings yet

- Patito AmigurumiDocument7 pagesPatito AmigurumiElisa Camargo100% (3)

- EP16755Document9 pagesEP16755Petya Kirilova Maneva100% (1)

- Mama's Garden: FabricsDocument4 pagesMama's Garden: FabricsCreek LiteracyNo ratings yet

- EN Flower Valley Shawl by Joanna GrzelakDocument20 pagesEN Flower Valley Shawl by Joanna GrzelaklunajakovNo ratings yet

- Railway Top. Tunisian Crochet Pattern - ByKaterinaDocument1 pageRailway Top. Tunisian Crochet Pattern - ByKaterinaArantza PinedoNo ratings yet

- "Pinch" The Crab Pillow Buddy: Pattern by Accessorize This DesignsDocument7 pages"Pinch" The Crab Pillow Buddy: Pattern by Accessorize This DesignsSimone AbreuNo ratings yet

- Jacket For dollsENGDocument5 pagesJacket For dollsENGSophia Rubio100% (3)

- Introduction To Creative Crafts ReviewerDocument4 pagesIntroduction To Creative Crafts ReviewerNcle NaborNo ratings yet

- Arts7 Q2 Mod1 ArtsAndCraftsMirrorsOfTheRegionsIdentity V5Document36 pagesArts7 Q2 Mod1 ArtsAndCraftsMirrorsOfTheRegionsIdentity V5Jamie FernandezNo ratings yet

- Qdoc - Tips Amigurumi-CatDocument7 pagesQdoc - Tips Amigurumi-CatMilena Moura100% (1)

- Heidi The HedgehogDocument7 pagesHeidi The Hedgehogvaytiare.lopez1100% (3)

- Types of Sewing NeedlesDocument21 pagesTypes of Sewing Needlesaanchal jainNo ratings yet

- Sora Esmas - Cart of ReliquariesDocument8 pagesSora Esmas - Cart of ReliquariesJames BashNo ratings yet

- English Birds Rachel CrochêDocument14 pagesEnglish Birds Rachel CrochêLaura Rodriguez100% (1)

- 215s-11 Ortega-Style Backpack: Suggested YarnDocument3 pages215s-11 Ortega-Style Backpack: Suggested YarnClaudiaPilarPatiñoCortesNo ratings yet

- Examination in TLE 7Document4 pagesExamination in TLE 7HARLEY L. TANNo ratings yet

- Palace of The Silver Princess-16-18Document3 pagesPalace of The Silver Princess-16-18Leonardo GuimaraesNo ratings yet

- Bubbles and Bongo, Sienna The Kitten - ENDocument9 pagesBubbles and Bongo, Sienna The Kitten - ENaline leite100% (1)

- Wednesday VestDocument2 pagesWednesday VestlaurennoexisteNo ratings yet

- Girafe CrochetDocument10 pagesGirafe Crochetnannae2103100% (2)

- CRAFTING CULTURE Likos, Mamandiang and WoodcarvingDocument2 pagesCRAFTING CULTURE Likos, Mamandiang and WoodcarvingJAMIL ASUMNo ratings yet

- Pad Harshita Kartik PPT Assignment 1Document23 pagesPad Harshita Kartik PPT Assignment 1kaarthikayaNo ratings yet

- Gabrella Vanny - The Necklace SummaryDocument2 pagesGabrella Vanny - The Necklace SummaryGabrella Vanny IshiyamaNo ratings yet

- Blossom: @letcrocheDocument6 pagesBlossom: @letcrocheAlexandra ReszlerNo ratings yet