Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2015 227413 Sanskrit-In

2015 227413 Sanskrit-In

Uploaded by

Yuri Sagala0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

47 views477 pagesOriginal Title

2015.227413.Sanskrit-In

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

47 views477 pages2015 227413 Sanskrit-In

2015 227413 Sanskrit-In

Uploaded by

Yuri SagalaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 477

SANSKRIT IN INDO!

by

Dr. J, Gonda

Professor of Sanskrit and Indonesian Linguistics,

Terecht (Holland)

International Academy of Indian Culture ij

‘Nagpur (India)

41952

SARASVATI VIHARA SERIES

EDITED BY

RAGHU VIRA, w.4,, vr... p. oie. em pin,

Director, International Academy of

Indian Culture, Nagpur

TN COLLABORATION WITH

OUHER SCHOLARS

Volume 28

SANSKRIT IN INDONESI

Published by

‘Dr. Lokesb Chanda

Secretary

The International Academy of Indian Culture

Negpur

Printed by

W. D. Ojba

Manager, Arya Bharati Mndronalaye, Negpur

CONTENTS

Preface, 2 ee

Abbraviations, 66 6 6 ee ee ee

I, Introductory. i

1. On the IN. Languages in Genova. / ee

2. On Lorowords in the IN. Languages in General... 6. 2 1 ee

3. Tho Ancient Connections between India und Indonesia... 2 6 se

IL. Tho Spread of Sanekrit over Indonesia. _

1. How aid Sanskrit Reach Indonesia, © 2 ee

2 Indian Alphabets in Indonesia. - 2 ee ee

8, Tadian Elements in the Minor Languages of Indonesia. 2 2. 2

(i) The Réle of Malay and Javanoro, 6 6 6 ee ee

(i) The Languages of Celeboe, 6 ee ee ee ee

(ii) The Islands Hast of Bali; ee ee

Gv) Bi

(w) Philippine Languages. 6. 0 ee ee

(vi) Languages of Sumatra : Gayo and Achebnese.

(vii) Languages of Sumatra: Batak. 6. ee

(Wii) Nis,

(ix)

4. General Review of e Number of Widespread Wordy, 2. 6 2

5. Borrowing by Way of Dravidian Lan;

6. Borrowing by Two Ways, 6. ee ee ee

7. The Infiltcation of Sauskrit througl the Medium of Learning and

Written Tests. ©. See ee

TEL. Sanskrit Loan-words from the Point of View of the History of Civilization.

1. Goda, Mythological and Legendary Higares, and Hinds Denominations. .

2. Doath aud the Life Heresiter.. 2 2 ee

3, Religion and Mysticiem in Goneval. ©. 2 ee ee

4, Bites, Geremonies and Law. oe

pene re

OB

6. Medicine. 0 ee ee

6. Arehitecture. ee

7 Namorals and Ohronologys ss eel

8. Some Al

9 Botanical Names. 6 6 0 ee ee ee

JO. Names of Persons. 6 ee ee

LL. Geographical Names ee ee ee

mobTerms. - ee ee

32

83

33

38

46

aL

52

ar

100

180

146

165

167

189

196

199

202

205

212

216

TV. Ontwrard Appesrsnes of the Borrowed Words,

1. Phonetic History of the Senskrit Hloment in IN. Languages. . . . . 299

@) Avaptysis or Svarabhalti, 6. eee 888

(i) Dissimiiationn Se 288

(iii) Spovteneous Negalization eto. 2. 6. ee ee wy 288

(iv) Other Consonaxtal Bpentbesis <6 ee. 886

() BaphonioTocertion. ©. oe ee ORF

(wi) Baplology. 6 see eee ee ee ey 28T

(ii) Metathatin ee. O87

(iit) Treatment of Vowel. 6. ee eS 889

(ix) The Vowel of the Penult.. 6 ee. a

{x} Tho Vowel of the Antepenult, 2 6 ee ee ee 243

{ai) Moro Inelieatal Vooalie Change. 6... Ome

(aii) Some Groupa Consisting of Conzonant and Vowel... . . . 945

Gil) Aspieates and 888

(xiv) Contraction, .°- . ee Ly Se ee ek 248

{xx) Trentment of Other Consonants. . 6... 288

Gl) Oust ee ee BBL

Gvii) Teestmont of Ivitial Nesals. ©... ae

(ii) Altermsting Nosals se eS 88

(xix) Diseyltebism ond Aphacresin ©. 253

(sx) “Brothetie’ Vowelb 2 ee 257

Gri Sysco ee ate

(xsil) More Sporadic Ohange, 6 2 ee ong

(xxii) Venison as to the Form of the Words... . , . |)! ggg

QMorpbolosy. oe eee eee

3) Seaskrit Stems as Ropreseated in Indonesia. coo tne

Gi) Sansbtit Flestion io Indonesia, se i

3. Matua! Influenes of Words. 2... om

() Secondary Bases in -i in Indonesia. — : Soo ms

Blending ©. ee ee ee

(ii) Motomiysiss. 2 tt 28h

liv) Popular Etymology and Adeptetion.- 2. | |) SS

(wv) Retrograde Derivation... 2... . Titi Be

(wi) Duplisetion oe 8

4 Morphology ye sooo

| @ate i 8

t fi) Compomds

1 Gi) Hybrid Aggrogutins. «2 2 2. 800

i 5, Differentiation and the Development of Homonyme, . |. | SOP

i (0 Diferontistion, ts me

0 6°45 . 818

. {iv)

(i) Homonyins, © ee ee ee BLD

6. Various Etymological Problema. . . . . . e+e ee es BOL

. Ohange of Meaning,

1, General Remarks. © 2) ee ee ee ee 888

2 Semantic Change and Historical Hvolotion, . ©... . . s+ - 380

8. Narrowing and Widening of Meening. . . . . 1... . - - + 887

4, Mobaphors and Other Semantic Ohanges. . . 2. 1 1 1 1 + + 849

5, Tabu, Buphemism ete. 2 1 Ne es BBE

6. Matual Influeneo of Words from the Point of View of Semantics. . . 870

7. Complications and Problems... . . 6 ee ee ee BIT

8. Special Semantic Changes in the Languages of Literature and Courtesy. 383

VI, The Reaction of the IN. Languages to the Influence of Sanskrit.

1 The Structure of Words and Sentences. . - . . .. 2... . 886

9. Loan-Translations, . - ee ee ee ee AON

3.The Reception of Sanskrit-Loans into the Standard Language and

Special Vocabularies, ©. 2 6 ee 408

4, Sanskrit-Loans and Modern Times. - 2... 2... 1... 48

APPENDICES

1, Sanekr

‘Loans in Indonesia, Indian Sanskrity and Sanskrit Lexicography. 498

2, Sanskrit in the West by Way of Indonesia. . 2. 2. 1... AB

INDICES

A Senshi, ee a8

2, Middle and New Indo-Aryan Languages... . 2. 2... 469

3. Indonesian Languages... . 2...

Addenda et Corrigenda, . . .

ee ee LAB

(x)

:

1

FOREWORD

“Sanskrit in Indonesia” will speak for itself. It isan

exhaustive study—amazing in these days—done with great ability,

knowledge, care and love. It is fascinating reading, for Indonesians

in particular, the origins and the relations to it of these words,

the bearers of so many ideas, and to imagine the great impact of

one culture upon another, of one language upon the other.

Language is created, exists and is developing to serve the

people, the nation, the society in general. It is a product of

history, of many epochs. The inclusion of so many words of

Sanskrit origin in many Indonesian languages, is the product of the

cra of great development in India in the first centuries A.D. The

languages in the archipelago have taken a certain shape, they have

been enriched by these Sanskrit words, developed and refined,

Since then, Indonesia has been through’ periods of decline and

progress. ‘The languages have served so many cultures, Buddhist

onginally and later on Hindu, but also Muslim, the ‘period of

internal,strife and of foreign domination and now are serving a new

era in Indonesia. A great many of these numerous words will

certainly continue in the process of growth and development of the

hving languages of Indonesia, and certainly will play a very

important role in the further development of Javanese and of the

Bahasa Indonesia, the national language.

So, Sanskrit still forms, and will continue to form a great

hnk between many living languages of this part in Asia, particularly

of the peoples in India and Indonesia.

It is for this reason that Professor Raghu Vira insisted that

being the Representative of Indonesia to India, I should have the

honour of writing this foreword.

With me, a great many, both in India and Indonesia will

be grateful to the author of this book and to the International

Academy of Indian Culture for publishing it. It will stimulate

thought for further studies among linguists in Asia and also create

more interest among others for closer cultsral ties. It is one of

those rare examples that will, substantially and by itself, create

better understanding and goodwill between two nations.

SoEDARSONO:

(Ambassador for the Republic

of Indonesia in India )

New Delhi 11th December 1952

PREFACE

This book is primarily intended to meet the requirements of all

those scholars and other readers who take an interest in the many

aspects of the linguistic and cultural relations between India and

Indonesia, The author, not aiming at anything like completeness, has

given a prominent place to more important topics and established facts

and has focussed the ‘attention not so much on etymological possibilities

and speculations as on the main problems connected with the spread

of Sanskrit in the Indonesian archipelago.

The publication of this work has been made possible by the

activity and generosity of the International Academy of Indian Culture,

Nagpur. The author therefore readily takes the opportunity of expres-

ing his deep obligation to the Academy's director, Prof. Dr. Raghu

Vira for his keen interest in the subject of the book and for his

willingness to publish it in the Sarasvati Vihara Series. If this work

will help in some measure to realise the noble aims and ideals which

the Nagpur Academy has in view, the author’s labour will be amply

repaid.

A special debt of gratitude is also due to the Academy's zealous

secretary, Dr. Lokesh Chandra, who has been indefatigable in correc-

ting the proofs and in drawing the author's attention to Tacunas in the

press-copy. He, moreover, suggested adding many words and meaninge

to those already entered and was unremitting in the care with which he

checked the author’s statements in connection with Hindi and other

Indian words, .

The index which has been added to the volume will be found

incomplete. We did not, indeed, try to make it exhaustive, but sugges-

tiye only of the Sanskrit elements discussed.

J. Genda

(vii)

ABBREVIATIONS

A. LANGUAGES

Ardhamigadby Mac. Macassar (Colebex)

Arabic Mad. Madoress

Balinese Mah. Mabdristri

Bare’s (Golebes) Mal. Maly

Batak (Sumatra) Mar. Maright

‘Benga}y MIA. Middle Indo-Aryan

Buginese (Catebes) Mix. Minangkabau

Boglish NIA. New Indo-Aryan

Frenoh OSay. —Ola-Tavanese

Gujarati Pat.

Hindustiai, Hind Sour.

Indo-Huropesn Singh. _Singhalese

Indonesian Sp. Spanish

Italian Sund. Sundanere (Java)

Javanese Tog. Tagalog (Philippines)

Kero-Batak Tom Tamil

Latin TBat. —Toba-Batek

Ybaon

B. BOOKS AND PERIODICATS

(The Ola-Javanose) Adiparwa, edited by H. H. Juynbott, The

Fague 1906.

(Tho Old-Javanese poom) Bhomakawya, edited by RB, Priederich,

‘VEG. EXIV, Batavia 1859,

Bijaragen tot do Taal-, Land- en Volkeukunde van Nederlandech-

Indié, vol,1-104, and Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkuade,

vol. 105— edited by the Koninklijt Inetitaut, The Hague 1853—,

(The O1d-Javanose) Brabmipdaparins, edited by J. Gonda, Ban.

dang 1932,

Bulletin of the School of Oriental (nd African) Studies, London.

(The Ol4-Javanese poom) Bhirata-Yuddha, edited by J.@. H.

Gunning, The Hague 1903,

Harvard Journal of Asintie Studiee, Cambridge Mass.

H. Yaleand A.C, Buell, Hobson-J sbaon, new 0d. by W. Crooke.

Fournsl of ths Acnerican tal Society, New Haven Conn.

Journal of the Royal Asiatio Society of Great Britain and Ireland,

Londor.

Drie booken: H. H. Jayoholl, Drie boeken van heb Oudjavaansohe

Wal. or Woordenlij

‘Mahabharata, Leyden 1898,

H. H, Jaynboll, Oudjsvaauach-Nederlandsche

‘Woordeniijst, Leyden 1928

HN. van der Touk, Kawi-Balinoosoh-Nederlandech Woordeu-

book, & vol., Batavia 1897-1919,

4H, Kern, Vorapreida Geschriften, 15 vol, The Hague 1919-1999,

(ix)

‘bh. The Mahabharata.

MED. A Msay-Enetish Di

ua Is Soeidts de Linguine?

onary, 2 vol. Matilene. Grecee 1952.

fo de Paris, Paris.

pire: de

i We Mosier Wiliame, A Sausiti-Hnglich Dictionary, new edition,

Os'ord 1899.

fold Tuvanave pen) NGgerarbigames ofited hy A Kern, ¥.G- vit

and. VITL

The Old-Tavanete Raviiyays, edited by H. Kern.

Petrograd Distionery, je. O. Bohilingk wad He Both, Sanskrit.

sWarterhveh, 7 rol. Porregrad 1855-1875.

Th, Pigevtl, Javaona-Nederlands Hand woordenbovk, Groningen

1988.

Piachsl, GPS. B.

schel, Grorormtix der Prakrit- Sprachen, Strassbues 1900.

Raw. Ban dyens, Tho O'd-Javano:e Bim. was edited by H. Korn, The

Flogue 1900.

BY. Ragveda-cemmbité.

we. ‘Tijdccbrits vee heb Betaviane Gensotschp, ie. Tijdschrift voor

Jodishe Teal, Land. en Volkonkonte, edited by the Batavians

Gensotschan voor Kunsten oa Wetensshappen, Batavia Jakarta.

yan der Tank, KEW. : s€8 KBW.

VEG. ‘Vorhandelirgen ven bet Betaviass Gonootvehap van Kunstes en

Weteo- chanpaa, Batavin

VEL Vorhandetingen van heb Kontablijk Institunt voor Tasl-, Land-

en Vi onde, Batzvia-Jakarta.

Witlinsons MED : see MED.

Wir. Wi dpparven : The Old-Javanoss text weseditedby H.H. Juynboll,

‘The Hague 1912; pert of ik also by A. A. Fokker, The Hegue

3988,

2DMG. Zoitschsift der destachen morgenléndisohen Goze sebaft,

Laipsic.

C. GuND

coll.

or. :

a? jn the same mesning

if. in fine compoaitl, i.e. ab the end of s compound

xa. Widung : the kidungs are @ oles of ancient Javanese poems dealing

with bistorieal, legendary and otber themes, and writton in a less

igh and artificial style than the kivya poama (kakawins)

we. rama, 4.2, the Javanoes voosbulary of courtesy

wri. crams ingeil, i.e. the limited Javanese vocabulary used in eddrens-

ing, ot speaking of, highly pluce yersonk

ib, literary (style)

mod. modern

ne ngoko, he. the Javanese azote’ i

ae neste LetbeTeran ‘voonbulary of familiarity and inforwal

ree. regional

sx)

GENERAL REMARKS:

In instancing Indonesian words thoir orthography has been brought into

harmony with the usual method of transeribing Sanskri

modern orthography of the main languages bi

of Old Javanese books etc. are, however, wril

cares the

» in general, been sdopted. Titles

toa in the Sanskrit wa:

In Moder-Javaneee » final @ is pronounced as the a in Hog!. water, A

written ain s penult precoding such an a likewise represonts that aonods when one

consonant, # consonsnt proceded by ity homorgenie nasal, or sis follow. Thus both

vowels ate pronotinced as the 6 in water ii

i mata, tampa, gaiiea.

(zi)

LINGUISTIC MAP OF INDONESIA

Legenda

D_ Indonesian languages

I PHILIPPINE GROUP

1 Formosan 2 Batan 3 Tagalog 4 Moko 5 Tico! 6 Bisaya 7 Ibunag

# Igorot 9 Magindenao 10 Tingyan 1 Dadayay 12 Sulu 18 Palau

14 Sangire-e aud Talaud 14s Bantik Lb Beatenan 15 Bolaang.Mongon-

dow Lf Tambutn Tonsen Tondano sub-group 17 Tontemboun Tonsawang

-geoup (14-17 usually called axb-Philippine languages)

PMATRA GROUP

1 Achebnove 2 Gayo 2 Batak idioms (a Karo b Toba 0 Simalungun @

Mandailing and Angkola) 4 Minangkabau 4° Labu 5 Malay (e Riau Malay

b Jakarta Malay ¢ Kuba @ Moluecan Matay) 6 eo-called Middle-Malay

7 Rejang SLampong 9 Simalar 10 Nias 11 Mentawsy 12 Enggano

13 Lontiong 14 aud 15 other Samatran dialects

Hi JAVA GROUP * 1Sundaneso 2 Javanese 4 Madurese

TV BORN SROUP (so-called Dayak or Dyak languages)

Klemantan languages 2 Iban lanyunges 8 Ob-Danum languages 4 Kenja

group 3 Marni group 6 Milano

BAJO or language of the sea nomads

\LINESE AND LANGUAGES WITCH ARB NEARLY RELATED TO 1T

1 Balinese 2 Saeak 4 Sumbawa

VE GORONTS1.0 GROUP

1.Balanga 2Kaidipan 3 Gorontalo 4 Beool

VIL TOMINE LANGUAGES

VET TORAIA TANGUAGES

Kaiti QKulawi 3 Pipikoro 4 Napa 5 Bada ete. 6 Leboni 7 Bare’e

5 Wobw

IX LOINANG GROUP [Xa BANGGAT IDIOMS.

XS BUNGKU-DAKE GROUP

XML LANGUAGES OF SOUTH CEIRBES

I Mooassar 2 Buginese 8 Lawn idions 4 Sa’dan

Santh G

T other idioms of

NIT TANGUAGES O8 HU! MUN\.BUTON (BUTUNG) GROUP

XML BIMA-SUaMBA GROUP

1 Bima 2 Manggarai (Wlores) 8 Nyad’s (lores) 4 and 5 dialects uf Sumba,

6 Hawn

DBON-LIMOR GROUP

2 Solorese (language of Solor) 5 Timorese (language of Timor)

7 Rotinose (language of Roti) 10 Kisar il Leti 13 Taninbar 18 and

19 Ceram languages 21 Panta 3, 4 ete. other languages

XY SERA LANGUAGE

XVE SOUT UALMABERA MOMS A

I South Halmahera idioms 9 Nnfor

Austro-Asiatic languages

Non-Indonesian languages of North Halmahera

Papua languages

Melanesian languages

wD RELATED TANGUAG

aQtna

CHAPTER [

SECTION 1

ON THE INDONESIAN LANGUAGHS IN GENERAL

As is woll known, the IN. tongues may be said to form a linguistic family

of their own, or to belong to she much more extended group of the Austronesian

languages, which has oven bean combined with other groups into the Austne

family. So it would bo impossible to deal with the subject’ proper of this book

before giving a cursory survey of tho most important characteristics of the IN-

languages and showing at whic! ~ the structara of Sanskr:t

which is an Indoeuropean language.

According to the adherents of a method of classifying languages which has

long enjoyed popularity and, at first right, caems to’ afford a good basis for

distinguishing them by saliont features, IN, usad to be considered as agglutinative,

while TH. as inflectional or syathstic. Languages of the aggtutinative type

were held to be marked by agglutination into x single word of various elements

each with @ fixed connotation ond each, while preserving its individuality,

meckanicslly added to the complex constituting a word. The synthetic or inflec-

tional class was, on the other hand, regarded as distinguished from the ageluti-

native type in that the elements composing words have now become soamalgamated

with oach other that, apart from an historical enslysis, they-can no longer bo

separated from the complox as a whole, used as a word.

‘This scheme of classification has, however, proved inappropriate. Ib

leads, for ono thing, to grave misunderstendings to aay that-in agglutinative

languages individual elements are, es a rule, mecbanicaily added to or separated

from the complex constituting a word, and devices supposed to be typical of them

may also o¢our in languages belonging to other classes, and vice versa. Historical

stages or supposed historical stages are, morsover, apt tobe substituted for the

contemporaneous or actual tages of the language.

We shall, therefore, refrain from using the terminology adopted by those

who favoured such systems of chatactorizing languages, aud, for practical reasons,

confine ourselves to presenting, in a comparative way, a general view of IN

languagea as they were and are daring the period in which they. have been in-

fluenced by Sansbrit.'

‘Whoress ia the If, domsin linguistio aflinities ara often veiled by the infu-

ence of intornal factors as well asevonts of economio, religious, and political nature

which have been operative in producing many such divergensies as exist, for exam-

ple, between Hindi and English, between Sanskrit and South African Dutobs or

between Latin and modern Persian, one of the salient feabures in the IN. family,

the territory of which consists almost exclusively of islaads, is, in general and

leaving aside more or less particalar ensea, the homogeneity of their structure and

the comparatively high degree of re:emblenca they have to each other. There exist,

of course, many conspicuous points of difference between Tagalog (Philippines) and

Gayo (Sumatra), betweoa Baréo (Celebes) and Old-Javaness, but various traits of

their grammar, thei phonetics, morphology and syutax, outstanding charactoristios

of which ave essentially of the same pature.

points they differ £

2 SANSRRYZ TN TNDONBSIA

The vowel ssatems of IN. laoguages exhibit s high degree of andormity,

Sonsiis possesses, tho diphthongs ineluded but not the vowols affected by a nasal,

33 dilfereas vowels. in IN. languages, however» the samber of vowel phonomes is,

in general, esitod. alshoagh there is, of coarse, from the purely phonetical point of

“hee, much roow for nondistinetive variation of eacb Daowemes ‘Tagalog possessé

phocologisally spesking no ze0re thaa a very simple three-vowel systeu ; a high

Front vowal (2 & low indifferent vowrel (a), and a high back vowel (x). Thoro is,

Lowerensa vowel, of frequent IN. oveurtancs whiab isleokingin Sanstci , but though

variously prououneed, fairly rexembles the Hindi a # or the ® (written o) ia Engl.

Grave the? (writkan 6) fo Engl. the dog. In Sanekrit many pairs of words are diatin-

gnishad by the quantity of oe of their vowels : dina- feat ‘day’: dina- WA

‘gud, weal't sula- QW sou’: sia GX ‘chariotecr’. Ia Javanose, Malay snd

ther languages of tho Archipelago which borrowed many Sanskeié words such

Spposites are uakrowo, as thero is, as a rule, no phonologioal gradation of

qnantity.? IN. Iongoages and Sazskrid are in g with each otter in that

Ahpbihougs play o limited pact, Sansteris hes only af and au, in IN. af au us

fare those whieh are most commonly met with, but they only eppear exceptionally

in oyllablos other ter Ue fiaal, aud some Inaguages have modified, monophtbone

‘gued or reduced them to one of their componente.

‘Ths consonant systam of an IN. language is, generally speaking» rather

simple Si-has irate series askh %, ch @ oto, aro lacking except for a very

interesting ease like, the Maduzose gh, ib, di, dh, bb (no corresponding Mh ote.).

Whereas Javanese, lize Suaskris, Praxrits, and modern Isdian languages, possessos

acerie: of socalled retrofiessa side by sido wicn the dentals (thus Jav. ¢

produced by raising the tip of the tongue or curling it beck and apsard beside

tformed by the tongs approximating the tips of the teeth). Metay and other

Ianguages have only one series. Ia general apirants other than s are absent:

Sanskrit likewise has n0 spirants, threo voiceless sibilants j W, ¢@ands a

exeepted, In many of these idioms the gloital stop (9) is,howover, a regular

element.

‘Thug, the sounds of the Javanese language might be srrenged according to

the following eshomo :*

Vows: a eiowé

Consonants: p bm

tdadn lw

td@ sh

cf R Fy

kg ts

g (alottal stop)

__ The ascent iy, a2 vale, uot strongly marked and often difioult to deter.

mine, But the acsentnstion of individual languages may be considerably

varied. Tho nature of the ‘prosodic features’ ia general —L prafer this term to

‘aystom of accentuation’, beoauso, to mention only this, quantity often plays an

important part in the phenomena meant by ‘acoonbuation’ in the grammars—is

often, moreover, still insufficiently known, Yet, it is clear that we often have

to take into account the dominant aocont of the breath.group, by which the

‘prosodic foatotes of its components may be profoundly modified. Another point

of moment is that stress, tone, quantity may very often be entirely disregarded

SANSKRIT IN INDONESIA 3

from the phonological point of view.

Passing on to the form of words we must first romark that one of the most

oatatanding charactoristics of the Archipelago consists in their tendency to a dis-

syllabie structure, About 96 per cont of the ‘word-bases’ which are supposed to

have existed already in Original IN. are dissyllabic*, and in modorn Javanese

over 85 per cant of them have two syllables. The same language, like most of

the cognate idioms®, prefers a regular alternation of con-oaznts and vowels to

Groups of phonemes of either class. Initia! consonant clusters (which ere freaueat

1m Sanskrit): ksa T, yea % tra A nya Sh stra ¥F, and finel groups of the

same kind (which are rare) are, as a rile, not admitted; a group of three

and many groups of two consonants are avoided in the middle of @ word

Gn Sanskrit such clusters as pf CA pn H, my % ot =H, ty Re ndr AH ote.

aie far from beleg uncommon). Like Sanskrit, Javanese unquestionably refrains

irom two vowels following each other in the same word. Javanose and other IN.

languages prefer a consonantal beginning of a word to a yooalict in Malay the

proportion is about 10:1, in Sanskrit about 44: 1. Finals are, likewise, pre-

ierably consonants; in Sanskrit, where consonants occurring as nels are limited,

vowels ate, comparatively speaking, frequent in that position. Thus, words

lige the Malay burwi ‘bird’, quai ‘mountain’, mulut ‘mouth’, bébun ‘enclosed

garden’, rumak “bouse’, Javaneso sugih ‘rich’, tipis ‘thin’, waras ‘recovered’

belong, as to their outward form, to the most common type. But the type Mal.

mata ‘eyo’, Jav. kali ‘river’ is far from being infrequent.

As regards the dissyllabic word-form, is must, however, be added that in

practice many words of three or four syllables ara found, beesuse two types of

word-formation, which are tho most ontstending, vis. derivation by means of

affixes, and the formation by means of tnsystematic insertion—both of whick

devices will be deals with later—result in longer worda: Jav. babad an ‘clear-

ang’ beside baad ‘to clear forosta’ and fi.time: ‘found, met with’ beside tému

‘poeeting’ axe instaness of the former process, Gayo (Sumatra) timpapak beside

tapak ‘palm (of the head)’ acase of the latter, And as to clusters, some ara

admitted: in Javanese, for instance, pl, pr, gr, i, ete. are, espeaially at the

beginning of the word, frequently founds but never at the end. In the intonor

of the dissyllabic IN. word-base tho group coolusive and preceding homorganie

nasal is very often met with, the combinations of 7 ov I with an occlusive aro

no’ searce ot only oceasionelly found. Ia modern Javaness, word-bases of the

type represented by simbah ‘the Indonesian abjali’, tombi ‘medicine’, tanda ‘signs

mark’, buikar ‘unpacked’, number over 2300, end worde with medial clusters

like mpl, kr some hundreds, The IN. ‘internal’ neeels and liquids are, however,

generally speaking, ofien rather debile: there are many variants of doublets

(Mal. maikis: matis ‘to defy’) ond some native alpbabess systematically omit

writing the internal nasal before an occlusive or use distinct lottere to indicate

mp ete., in which the occlusive element is often weak or lieble to change.

A fow words must be said about the analysis of words. Monosyllabie ‘roots’,

as @ rule consisting of consonant, vowel, consonant, and usually represented by

the second syllable of the word-base, often cour unchanged—or changed in accor

dance wit more or less definite principles or phonetic laws—through many serios

of words with similar meaning. Thece words or roots repeatedly reour in many

4 SANSRRIT IN INDONESIA

Innguases, ‘Thos, the Malay, Tagalog ete, nipis ‘thin, tenaous! contains the same

‘root pis (to which we nsoribe the general meaning of thinness or sm Hoes) as the

Malay and Old-Javanese tipis ‘thin, delicate’, the OJav. tapis ‘small’ in ma-napis

ce in size’, and so on. These IN. roots must not be regarded as rexewbling

in which the coasonents are held together in different forma by

Is varying in acoordance with the ides which it is desired to

express: in Hebrew, ganad ‘he bas stolen’, ganib ‘stolen’, gondb ‘stealing’, Nor

must the Indoouropean Ablaut be considered a parallel either: this inherited

systematic vows! gradation, which arose under accontual and other conditions of

the parent speech which were widely divergent from conditions in Original Indo-

nosian, has come to perform: important grammatical and semantic functions: Skt.

dena. 2 ‘gol: daiye- 2a ‘divine’; namyate TIA ‘to be bent or bowed passive

beside nomati aafX “to band’: naimyate WFAA passive beside the causative ‘to cause

to bow or sink’. Bat the IN. phenomenon of so-called reot-vatiation does not, as

a rule, convey togular differences ot variations of meaning; ouly a tendeney to

sound-symbolism and other more or less unsystematie devices can be observed,

Although there are xoots that can serra as word-bases, and in coveral

eases, bases may be formed from the doubled or reduplicated root (OTav. laliak ‘to

peel’, Mal. kikir ‘file’), although, moreover, the proses of developing an initial

sound before the root (the so-called prothesis) is ropeatedly instrumental in for:n-

ing dissyllabio ‘bases’, the mos common method of fashioning word-bases eon-

sists fm the indissoluble union of a formative element (which in much the Jargost

puuiber of cases copies the first place) with the root. ‘Thus, ia Maley daln

‘eivoling round a central point’, gilit ‘rolling’, guliis ‘rolling slong’ we di

Hinguish a root lis and the preformative elemonts Ba-, gi-, gu Sanskrit words, on

the other band, are in grost part analysable into roots (eg. man-), suffixes of

derivation (e.g. wus.), and endings of inflection (e.g. -e}: manase; prefixes axe,

moreover, frequently added to words formed in this way: part. lgienort

In IN. lenguages so-called primitive or unsystematic processes of word-

formation bave, like other ‘primitive dovices’, a very wide ecope, Like all men

mhore epecoh is produced to s degree worth mentioning under tha influence of

‘affective’ or ‘smotive’ tendencies (for ingtance, children, the leas oultivated groups

tnd classes of our own sosioty, etotional individuals euch as poots ot young girl.)

members of swall eommanitiee, where the counteracting and rogularising factors

OF school, written Titeratare scientific thought, ee. are almost entirely missing are,

fomporabively speaking, easly diable to eertain devieos of word-formation. Uneya,

fematio intertion of an arbitrary snd often, from the standpoint of those who try

to dofine the objective sonse of words, meaningless element (the so-called ‘Streck-

formen’ device, to uss the German term) is extremely frequent: Malay sérampak

side by side with sampak ‘rubbish’; Gayo Vomparak : tapak ‘palm of the hand’

Jarintions upon familiar o: newly leatat words are lizewise ofton to be met erish

Mal. téabikar: timberek ‘potsherd’; Gayo lambak ; lambut ‘precious’, and an ineli-

zation to twist words into rimes is not only in modern Indian, but alee jn Indo.

nesian languages far from being suppressed: beside Malay tali ‘rope, cord’ we

find tal-timali ‘cordage’, beside sayur ‘green {00d : sayur-mayur “eeible ‘vege

fables ofall Kinds’ ef. Nepali luge suga ‘olothing and necessaries’; pelval sottal

petrol and labricants’. Cases of sound-eymbolism are frequent®. Ix a highly

Gereloped literary language like Sanekrit, which was already early. an instrument

‘to

the Semitic root,

characteristic row

SANSKRIT IN DNDONESLA

of expressing profound thought these devices had a very limited scope. The IN

word is, to wind up with and speaking quite generally, toa higher degree subject

to a tendency to variability than the Sanskrit word.”

Turning now to a very suocinet discussion of word-formation we must first

remark that such well-known methods of creating words es abbreviation, metaon-

lysis, retrograde derivation, popular etymology, eto., eto. are not less in use in these

Isngaages than in other linguistic families. ‘Thus Malay rek ‘match’ comes from

korsk api ‘match’ (korék ‘s pin or come object like that for pricking ete.’, api ‘lixe’),

modern Javanere farép-an ‘front veranda’ from farap T Jeavo, of couree, out of consideration

a number of Javanose terms bave been | the writings of fantasts and dilettantes.

added) in Raghu Vire, Our Basie Voca- | Seo, e.g. my remarks in TBG. LXXX

bnlary (Labore 1949), p. 185!f. (1940), p. 183ff. & propos of the opinions

2 G, A.J. Hazon, GajoschNederlandseh of C.N, Maxwell, who holds that 20

Woordenbock, (Batavia, Djaketza,1907); | language is older than Malay, Sanskrit

‘M Joustra, Karo-Bataksch Woordenboek | being very young, bocause it is a literary

(Leyden 1907), language. Malay hae, he seye, spread all

8 Joustra,o ,whilssnotising the origin | over the world, in support whereof the

(Mal. Skt’.) of Kirna ‘because, by, for | words Mal. kamapots and Engl. court are

the sake of' (

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- David Gale - The Theory of Linear Economic Models-University of Chicago Press (1989)Document352 pagesDavid Gale - The Theory of Linear Economic Models-University of Chicago Press (1989)Yuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Roger Crowley - 1453 - The Holy War For Constantinople and The Clash of Islam and The West-Hachette Books (2005)Document337 pagesRoger Crowley - 1453 - The Holy War For Constantinople and The Clash of Islam and The West-Hachette Books (2005)Yuri Sagala100% (2)

- A Grammar of Toba-BatakDocument170 pagesA Grammar of Toba-BatakYuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- 2020 Louvain StudiesDocument21 pages2020 Louvain StudiesYuri SagalaNo ratings yet

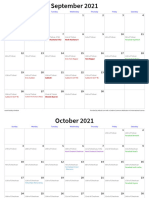

- Hebcal 5782hDocument13 pagesHebcal 5782hYuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- EN Images of God in Toba Batak StorytellingDocument33 pagesEN Images of God in Toba Batak StorytellingYuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- Vergouwen 1964Document479 pagesVergouwen 1964Yuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- Ps 12Document1 pagePs 12Yuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- Is There A Batak HistoryDocument18 pagesIs There A Batak HistoryYuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- 10152140961606675Document138 pages10152140961606675Yuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- Ps 2Document1 pagePs 2Yuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- Ps 10Document1 pagePs 10Yuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- Ps 13Document1 pagePs 13Yuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- Ps 7Document1 pagePs 7Yuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- Ps 1Document1 pagePs 1Yuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- Ps 6Document1 pagePs 6Yuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- Linear and Multilinear AlgebraDocument28 pagesLinear and Multilinear AlgebraYuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- Sierpi Nski Gasket Graphs and Some of Their PropertiesDocument14 pagesSierpi Nski Gasket Graphs and Some of Their PropertiesYuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- An Alternative Approach To Elliptical Motion: Mustafa OzdemirDocument26 pagesAn Alternative Approach To Elliptical Motion: Mustafa OzdemirYuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- Intrinsic Volumes of Polyhedral Cones: A Combinatorial PerspectiveDocument39 pagesIntrinsic Volumes of Polyhedral Cones: A Combinatorial PerspectiveYuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- (9789004170261 - A History of Christianity in Indonesia) Chapter Thirteen. The Sharp Contrasts of SumatraDocument112 pages(9789004170261 - A History of Christianity in Indonesia) Chapter Thirteen. The Sharp Contrasts of SumatraYuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- Apostolic FathersDocument175 pagesApostolic FathersYuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- Graph ColoringDocument11 pagesGraph ColoringYuri SagalaNo ratings yet

- Graph LabelingDocument3 pagesGraph LabelingYuri Sagala100% (1)

- Resistance Scaling and The Number of Spanning Trees in Self-Similar LatticesDocument18 pagesResistance Scaling and The Number of Spanning Trees in Self-Similar LatticesYuri SagalaNo ratings yet