Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Gandhi and Punjab

Uploaded by

AvaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Gandhi and Punjab

Uploaded by

AvaCopyright:

Available Formats

GANDHI AND PUNJAB

Author(s): RAJMOHAN GANDHI

Source: India International Centre Quarterly , SUMMER 2012, Vol. 39, No. 1 (SUMMER

2012), pp. 30-42

Published by: India International Centre

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41804017

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

India International Centre is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

India International Centre Quarterly

This content downloaded from

103.68.37.134 on Wed, 03 May 2023 14:38:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

RAJMOHAN GANDHI

Punjab

that pre- in andandthethat

Punjab Punjabs Punjabs thepre-

1947 titleIndian

the Indian1947

land,states land,article

ofofthisHaryana

comprising comprising

and states of stands today'

Himachal. today's

Fors Haryana for Pakistani Pakistani

the and Punjab Himachal.and

and that Indian

Indian was, For

decades now, that Punjab of old has ceased to exist as a political

entity Even before 1947, of course, Punjab was hardly uniform.

Its many parts differed from one another in soil, temperature,

population density, religion, caste, sect and other ways.

What was and is common to much of old Punjab and most

of its inhabitants, whether in India or Pakistan, is the Punjabi

language, which seems to have existed for a thousand years or

more. Punjab's long story includes Sufis and Sikh Gurus; Khatri

and Arora writers and officials; Akbar (who spent many years in

Lahore), Jahangir (buried in Lahore), Aurangzeb (who built Lahore's

Badshahi Mosque) and Dara Shukoh (still loved in Lahore); Banda

Bahadur; Bulleh Shah and Waris Shah; Nadir Shah and Ahmad Shah

Abdali; Ranjit Singh; brutal wars between the British and the Sikh

kingdom; the British conquest; 1857; the Lawrence brothers and the

canal colonies; Sir Ganga Ram, Iqbal, Faiz Ahmed Faiz; and a good

deal more.

At ground level, Punjab saw both accommodation and strife.

The tradition of Guru Nanak and Baba Farid continued to foster

peace. Compassion was practiced. Two Pashtun horse-dealers saved

Guru Gobind Singh's life.

Yet over time there were bitter conflicts, and also a clash

between purity of birth and purity of belief. If elites on one side

anxiously avoided 'polluting' contacts, elites on the other side kept

their distance from 'impure' beliefs. Though common people put

30

This content downloaded from

103.68.37.134 on Wed, 03 May 2023 14:38:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

GANDHI & PUNJAB : RAJMOHAN GANDHI

this clash to one side and carried on with th

men used the communal divide to climb.

Also, Punjab was absorbing a 'weapon culture'. Successive

events in the 18th and 19th centuries fostered it: Banda Bahadur's

fierce raids to avenge the killing of Guru Gobind Singh's minor

sons; the subsequent hunting down of Sikhs by governors in

Lahore like Zakariya Khan and Mir Mannu; the rise of armed

Sikh bands; Ranjit Singh's large and successful army; the so-called

Anglo-Sikh wars; and, finally, Britain's success in turning Punjab

into a garrison state.

The British recruited Jat and other Sikhs, Jat, Rajput and other

Muslims, and Jat, Dogra and other Hindus in such numbers that

Punjabis made up half of the Empire's Indian soldiers. The prestige

of weapons soared in Punjab.

♦♦♦

Hindsight asks why Punjab's partition, if it had to come, was

arranged with greater planning and without bloodshed. There alw

was something like a natural demarcation between western

eastern Punjab. In the 1880s, Denzil Ibbetson, British civil ser

and enumerator of Punjab's castes and tribes, wrote that cultural

demographic changes appeared 'with some suddenness about

meridian of Lahore, where the great rivers enter the fertile zone

the arid grazing grounds of the West give place to the arable

of the East' (Ibbetson, 1974: 11).

Western Punjab contained, in comparison with central o

eastern portions, a higher Muslim percentage, a lower popul

density and fewer towns. Including princely states, all of Punjab

a population in 1941 of 34.3 million. Of this total, 53.2 per cent w

estimated to be Muslims, 29.1 per cent Hindus, and 14.9 per

Sikhs. However, Hindus and Sikhs, taken together, outnumb

Muslims in the Jalandhar and Ambala divisions of British Pu

i.e., in today's Indian states of Punjab, Haryana and Himachal.

For more than 30 years, Gandhi's aim, and the desire of

great majority of Indians, was India's independence as a united na

It was in October 1939 - right after the start of World War II - t

Gandhi first commented on the idea of a separate Muslim-ma

nation. A Muslim school-teacher from Punjab had asked Gand

accept separation.

31

This content downloaded from

103.68.37.134 on Wed, 03 May 2023 14:38:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

lie QUARTERLY

By 1939 there was a climate for discus

but also some Hindus, had said that Indi

constituted two nations. One of the firs

Lajpat Rai. Writing in December 1924 in

Lahore in 1881), he said:

Under my scheme the Muslims will have four

Pathan Province or the North-West Frontie

(3) Sindh; and (4) Eastern Bengal.... It mean

India into a Muslim India and a non-Muslim India.

Despite advocating separation, Lajpat Rai envisaged a centre of

some kind. Thirteen years after Lajpat Rai's proposal, YD. Savarkar,

presiding at the 1937 session of the Hindu Mahasabha in

Ahmedabad, also said that India contained 'two nations in the main:

the Hindus and the Muslims'.

Gandhi's response to the Punjabi school-teacher was published

in his journal, Harijan (28 October 1939):

Why is India not one nation? Was it not one during, say, the Moghul

period? Is India composed of two nations? If it is, why only two? Are

not Christians a third, Parsis a fourth? Are the Muslims of China a

nation separate from the other Chinese? Are the Muslims of England

a different nation from the other English?

How are the Muslims of the Punjab different from the Hindus and the

Sikhs? Are they not all Punjabis, drinking the same water, breathing

the same air and deriving sustenance from the same soil? What is there

to prevent them from following their respective religious practices?

What is to happen to the handful of Muslims living in the numerous

villages where the population is predominantly Hindu, and

conversely to the Hindus where, as in the Frontier Province or Sind,

they are a handful?

The way suggested by the correspondent is the way of strife. Live

and let live or mutual forbearance and toleration is the law of

life. That is the lesson I have learnt from the Koran, the Bible, the

Zend-Avesta and the Gita.

32

This content downloaded from

103.68.37.134 on Wed, 03 May 2023 14:38:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

GANDHI & PUNJAB : RAJMOHAN GANDHI

Punjabis had first heard of Gandhi in 190

old and living in South Africa. Addressin

Indian National Congress, Gopal Krishna

follows about Gandhi:

It is one of the privileges of my life that I know Mr. Gandhi personally

and I can tell you that a purer, nobler, a braver and a more exalted

spirit has never moved on this earth. . . [He] is a man among men, a

hero among heroes, a patriot among patriots, and we may well say

that in him Indian humanity at the present time has really reached

its high watermark (Karve and Ambedkar, 1966: 420).

That year, 1909, when Lahorites first heard of Gandhi, was also the

year of the Indian Councils (or Minto-Morley) Act, which provided,

among other things, for a 30-member Punjab Legislative Council.

This Council was to comprise officials, nominated non-officials,

and a handful of elected members, chosen by property-owning and

educated Punjabis voting in separate electorates.

Though the Indian Councils Act of 1909 represented a modest

political advance, it damaged Hindu-Muslim trust in Punjab, with

Hindu-owned and Muslim-owned newspapers attacking the other

community and its journals.

At its founding in 1906, the Muslim League had asked for

separate electorates for Muslims, a request granted by an Empire

looking for ways to solidify Indian divisions. The Empire also agreed

with the League that in any councils created in India, Muslims would

have 'weightage' - a share larger than the population ratio.

In 1916 came the consequential Congress-League Pact, put

together in Lucknow by Tilak and Annie Besant from the Congress and

by Jinnah from the Muslim League side. Under the Pact, the Congress

and the League agreed to work jointly for 'early self-government' on

the basis of direct elections, separate electorates for Muslims and

Sikhs, and 'weightage' for religious minorities in provincial and central

councils. This meant weightage for Muslims in provinces like UP and

Bihar, for Hindus in Bengal, and for Hindus and Sikhs in Punjab.

In the years that followed, the Lucknow Pact was criticised on

both sides. Hindus said that Tilak and the INC should have never

agreed to separate electorates for Muslims and Sikhs. Muslim leaders

in Punjab said that weightage gave political leverage to a Hindu-Sikh

33

This content downloaded from

103.68.37.134 on Wed, 03 May 2023 14:38:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

lie QUARTERLY

minority which already enjoyed educ

advantages. In 1911-12, Punjab's Muslims, c

cent of the province, made up 24 per cent of

and 24 per cent also in the province's scho

Baisakhi Day, 13 April 1919, changed e

it seemed. Mingling in the mud of Jallian

Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims sealed what co

long pact. For weeks prior to the massacre

and Hindus, inspired by Gandhi's call for

the Rowlatt Act (which curbed free expres

solidarity. In discussion among themselv

that 'opposition to the Rowlatt Act and ad

practically universal' in Punjab (Jalal, 2000

Dissatisfied with the Hunter Commissi

into the massacre, the INC decided on a p

Congress committee comprising Gandhi,

M.R. Jayakar and Abbas Tyabji. Shouldering

Gandhi spent three months in differe

interviewed numerous witnesses. In the e

the committee's report.

Those three months of travel and liste

Gandhi with Punjab, which he was visitin

Everywhere, in addition to collecting evi

khaddar and the charkha and found m

responsive. He also sought funds for a Ja

said Gandhi, to engender 'ill-will or hosti

symbol of the people's grief' and a reminder

death, of the innocent' ( Collected Works,

up after Gandhi declared that he would, if n

in Ahmedabad to finance the memorial.

This declaration was a factor in the dec

Punjabi, Pyarelal Nayar, to join Gandhi. E

his Punjab tour, Pyarelal thought that G

assurance of strength' and 'an access to s

power which could find a way even through

wall' (Pyarelal, 1991: 5-7).

♦♦♦

But would he win Punjab, the Empire's sword arm, to non- vi

34

This content downloaded from

103.68.37.134 on Wed, 03 May 2023 14:38:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

GANDHI & PUNJAB : RAJMOHAN GANDHI

struggle and to Hindu-Muslim-Sikh unity? G

did not speak Punjabi. Most importantly, in

teammates of the kind he had found in some

In Gujarat, among many others, he h

In Bihar he had Rajendra Prasad. In th

C. Rajagopalachari. In UP he had Jawaharla

Lala Laj pat Rai, the Punjab lion, was

Gandhi. While the two had much in comm

partial. They differed on the possibility o

political front and of a united free India.

the Empire's lathis, the lion of Punjab died a

That year, 1928, he had come closer to G

him and with Motilal Nehru and Jawaharl

sake of Hindu-Muslim unity, joint elector

India, Punjab's Muslim majority should be fr

minority weightage.

In publicly taking this position, Laj pat R

Hindu and Sikh leaders in Punjab, who we

weightage in the legislature. Laj pat Ra

minority weightage, Muslims, thanks to the

dominant in Punjab. If Punjab's Hindus a

forego weightage, they would, he said, se

de facto Hindu rule in Hindu-majority porti

the centre Qa'a', 2000: 308-309).

But the proposal of giving up someth

national prize fell on unresponsive ears.

leaders did not want to lose weightage.

♦♦♦

A few years before Lala Laj pat Rai's death, Punjab saw the

emergence and equally sudden collapse of the Hindu-Muslim

front that Gandhi had helped create between 1919 and 1922.

Jallianwalla had fired all Indians for Swaraj, and England

France's treatment of a defeated Turkey and the placing of I

holy places under European control had angered India's Muslim

1920 and 1921, the INC and the Muslim League stood as one i

audacious campaign for Non-violent Non-cooperation that Ga

launched in 1920.

Across India, thousands tossed away jobs and careers and

35

This content downloaded from

103.68.37.134 on Wed, 03 May 2023 14:38:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

lie QUARTERLY

embraced prison. In the words of Ayesha

intensely sceptical of Gandhi, there were

of Hindu-Muslim goodwill'. Gandhi

extraordinary alliance' (Jalal , 2000: 237). A

hands, including many Hindu, Muslim and

An important piece in the story of th

successful, non-violent, and historic Akali m

was strongly and intimately connected to No

During this period, in addition to L

remarkable Punjabis - Hindus, Muslirris

platform with Gandhi, some briefly, oth

the rest of their lives: Swami Shraddhana

Mahatma Munshi Ram, stood with Gandh

poet Iqbal, and Sir Fazli Husain, founder of

for a few days (ibid.: 210); Maulana Zafar

and writer and influential editor, for man

educated Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlew, hailing f

of Kashmiris settled in Amritsar and Lahore

though often he differed strongly with Gand

Sardul Singh Caveeshar (who served

President in 1933) was another associat

leaders were close to Gandhi until the late 1920s. Abdullah Bukhari

of Amritsar, the fiery and at times indiscreet orator - as passionate

for universal Islam as he was for Indian independence - was for

years on the same side as Gandhi and with the INC, as was Dr. Satya

Pal, whose arrest along with that of Dr. Kitchlew and of Gandhi had

sparked off the Jallianwalla unrest.

Yet none of these personalities quite became a teammate with

Gandhi the way, say, Patel, Prasad, Rajaji, Jawaharlal Nehru, Maulana

Azad, Kripalani, Jayaprakash Narayan and Rammanohar Lohia had or

would become, not to mention Badshah Khan, who was in a class by

himself. And those who did become Gandhi's inseparable teammates

in Punjab for the rest of their lives - talented and productive

individuals like Pyarelal Nayar and his sister Sushila, and Bibi Amtus

Salaam of Rajpura - did not acquire influence across Punjab the way,

for example, the Nehrus, Patel, Prasad, Badshah Khan and Rajaji had

done in their parts of India or beyond. There was Gulzarilal Nanda,

yes, but he made Gujarat rather than Punjab his karmabhoomi.

Gandhi and Punjab needed a Muslim-Hindu-Sikh team that

36

This content downloaded from

103.68.37.134 on Wed, 03 May 2023 14:38:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

GANDHI & PUNJAB : RAJMOHAN GANDHI

would stay together no matter what and

such a team, Gandhi was helpless in Punja

m

To return to 1919-22: the apparent m

good to last. Turkey let India's Musli

khilafat for which India's Muslims sa

A crowd of non-cooperators in Chaur

Gandhi down by killing trapped police

and non-Muslims tried to outsmart one

community to resign from the Raj's off

pocketing every opening themselves.

Emerging in 1924 from a two-yea

found Hindu-Muslim relations in a

Punjab news sheets from both sides w

and reviling the religion of the opponen

of violence coming'.

After Non-cooperation, several M

company with Gandhi and the INC, i

brothers, as did a few Hindu stalwarts

However, "Muslim leaders like Ajm

Ansari, Abul Kalam Azad, Badshah Kh

who were enlisted in 1919-22, remaine

However, Kitchlew was the only Punjabi

The years from 1929 to 1931 saw the

Young Bhagat Singh's fearless defian

Lahore and his being hanged along with

many people. Yet Bhagat Singh too la

team that would stay together, come wh

Neither the Hindustan Republican

Jawan Sabha nor the Kirti-Kisan Par

Bhagat Singh was associated - could at

its fold. Moreover, sharp dissension, at

weakened the revolutionaries.

Then there was the Unionist Party, founded in the 1920s and

drawing its strength from beneficiaries in the canal colonies, and from

the Land Alienation law in Punjab, which the British had enacted in

37

This content downloaded from

103.68.37.134 on Wed, 03 May 2023 14:38:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

lie QUARTERLY

1900 in support of farmers threatened by

reflected the interests of numerous pro-E

Hindu landholders, but it could not appeal

to the landless, or to urban workers or trade

Bringing together, for the sake of Hindu

the anti-Empire Congress and the pro-Em

impossible goal in the 1920s and the 1930s

Much later, however, in early 1946, w

Punjab legislature held on a limited franchise

75 out of Punjab's 86 Muslim seats, the Un

Congress, with 51, and the Akalis and other

able to form a coalition ministry after att

Unionist or a League-Akali coalition failed.

Khizr Hyat Tiwana, the Premier in thi

Sikh coalition, was reviled by angry Mus

Khizr Singh'. After a year's civil disobedience

the Khizr ministry was brought down in Ma

Earlier, in November 1939 and again i

had made approaches to the then Punja

the Unionist Party, Sikandar Hyat Khan. T

on Sikandar and the moves failed, yet Gan

Partition by wooing the Unionists, wh

autonomous Punjab, is noteworthy.

♦♦♦

Between these two overtures from Gandhi to Sikandar, the L

had met in Lahore and asked for 'separate and sovereign Mu

states, comprising geographically contiguous units... in which

Muslims are numerically in a majority, as in the north-wester

eastern zones of India' (Merriam, 1980: 67). A delegate at Lah

asked whether the imprecise wording would not justify partition

Punjab and Bengal. Liaqat Ali Khan, the League's general secre

gave this answer:

If we say Punjab that would mean that the boundary of our state

would be Gurgaon, whereas we want to include in our proposed

dominion Delhi and Aligarh, which are centres of our culture....

Rest assured that we will [not] give away any part of Punjab (quoted

in Nairn, 1979: 186).

38

This content downloaded from

103.68.37.134 on Wed, 03 May 2023 14:38:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

GANDHI & PUNJAB : RAJMOHAN GANDHI

In November 1945, an unexpected candle

Punjab. Three Punjabis, one a Sikh, the s

third a Hindu, were together charged in the

trial of the IN As Dhillon, Shah Nawaz an

image of Punjabi and Indian unity. Sadly

only a short life. Before long, former IN

divided themselves into Muslims, Sikhs a

engaged in bitter communal disputes.

In the following year, 1946, three Brit

spent three months in India. Jinnah told

would not be satisfied with anythin

made up of 'all six provinces (all of Pu

Baluchistan, all of Bengal and Assam) and

(Moon, 1973: 246). The Congress, on the o

opposition even to a 'small' Pakistan if it wa

preceded independence, and if the NWFP,

recently defeated the League, was compelled

In response, the Cabinet Mission produ

tier plan of provinces, groups and a unio

architect, Cripps, later admitted was 'pur

interpretations of the proposal were prese

the League, and a game was played by all s

Selected provinces may join a large Mu

the Congress was told. Such provinces sh

League was told. Gandhi hated the ambigu

do not know how uneasy I feel,' Gandhi wro

'Something is wrong' ( Pyarelal, 1956: 204

to the Working Committee. Yet Gandhi

Patel, Nehru, Azad, Rajagopalachari and Pr

the game and enter the interim government

of August 1946 was an unwise, if also und

what he saw as Congress' success in the les

In August, Calcutta witnessed great

Noakhali, in November Bihar. The mixture of cleverness and

suspicion had brewed poison.

A year later, in October 1947 - after India was free, partitioned

and more poisoned - a Gandhi who had been publicly expressing

his distress received a letter from a friend urging him not to lose

heart. This is what Gandhi replied:

39

This content downloaded from

103.68.37.134 on Wed, 03 May 2023 14:38:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

lie QUARTERLY

I am not vain enough to think that the divin

fulfilled through me. It is as likely as not th

will be used to carry it out. ... May it not be t

courageous, more farseeing is wanted for the

Here Gandhi selects farsightedness as one

seems to suggest that he should have for

felt that, foreseeing its poisonous fallout, h

the game of deception that all three sides

the British - played during the stay in Indi

In March 1947, Gandhi was in Noakh

bring solace and courage to victims an

to perpetrators, when, following Kh

remarks from Master Tara Singh, lar

Hindus occurred in Rawalpindi and

killings, and responding also to press

Sikhs, the Congress Working Committee

on 8 March 1947.

The train to Partition was gathering speed. Gandhi's response is

well known. On 1 April, he proposed to Mountbatten, to Nehru, Patel,

Azad and other Congress leaders that a Jinnah-led central government

be installed with the INC's agreement and support. This, Gandhi

thought, could remedy polarisation in Punjab, avert an explosion, and

preserve the unity of Punjab and Bengal, and of India as a whole.

A key component of Gandhi's Jinnah proposal was that the

growing number of Punjab's private militias - Muslim, Hindu and

Sikh - should be disbanded.

How Mountbatten, supported by his staff, which included

the skilful VP. Menon, worked to scuttle this plan, and how, after

opposition from Nehru, Patel and company, Gandhi felt compelled

to drop it, is a well-recorded story that need not be related here.

Was Gandhi's plan, which was never put to Jinnah, a chance

for peace and unity in the Punjab and India of 1947? Calling it a

Solomon-like solution, one of Jinnah's biographers, Stanley Wolpert,

would speculate that the League leader would have accepted it, but

who can say for sure?

♦♦♦

40

This content downloaded from

103.68.37.134 on Wed, 03 May 2023 14:38:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

GANDHI & PUNJAB : RAJMOHAN GANDHI

At the end of July 1947, Gandhi took a trai

to Kashmir. The journey to Kashmir and bac

in Amritsar, Lahore, Rawalpindi, Wah, and t

in Hasan Abdal. On the eve of this trip, he s

[W]e should fast and pray on 15 August. I m

intend to mourn. But it is a matter of grief

and no clothes. Human beings kill huma

people cannot leave their houses for fear th

(96: 174-75).

This trip in July-August 1947 was his last physical contact with

central and western Punjab. In November and December 1947, he

twice visited Panipat in an unsuccessful bid to persuade its Muslims

not to migrate to Pakistan. This is what he told them:

If. . . you want to go of your own will, no one can stop you. But you

will never hear Gandhi utter the words that you should leave India.

Gandhi can only tell you that you should stay, for India is your

home. And if your brethren should kill you, you should bravely

meet death. ... But today, having heard you and seen you, my heart

weeps. Do as God guides you (97: 443-44).

On Independence Day, Gandhi was in Calcutta. News of Punjab's

violence made him want to go there, but Nehru and Patel advised

him not to. He would not be able to do anything in Punjab, said

Patel. On 30 August Gandhi wrote to Nehru,

Left to myself I would probably rush to the Punjab and if necessary

break myself in the attempt to stop the warring elements from

committing suicide (96: 304).

But fresh killings in Calcutta caused him to stay there and launch

a fast against the violence. The fast worked, and peace returned

to Calcutta.

On 7 September, Gandhi boarded a train for Delhi en route to

the Punjab. But he found Delhi to be a city of the dead and stopped

in the capital, reckoning that Delhi would 'decide the whole country's

destiny', that 'a fire here would burn all of Hindustan' (89: 23 7, 465).

41

This content downloaded from

103.68.37.134 on Wed, 03 May 2023 14:38:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

lie QUARTERLY

From 9 September 1947 until his assas

1948, he was in Delhi, not having gone t

time with Punjabi refugees.

West Punjab was on Gandhi's itinerar

March 1948. Among those he expected to

Mian Iftikharuddin, the League leader wh

Congress figure in Lahore, and his wife Ism

Had Gandhi found himself in either E

August or September 1947, the months whe

occurred, could he have prevented the b

Gokhale had said in Lahore in 1909, Gan

In 1921, after a visit to Punjab by Gan

triumphantly recorded, in so many word

did not think Gandhi was 'a superman' Q

It is to be doubted, moreover, wheth

could have swallowed all the poison let l

and September 1947, or put all that poison

* Adapted from the inaugural B.R. Nanda Memorial L

the IIC on 21 December 2011.

REFERENCES

Ibbetsen, Denzil. 1974. Panjab Castes. Lahore: 1882; reprint by Mubarak Ali. Lahore.

Jalal, Ayesha. 2000. Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam

since 1850. London: Routledge.

Karve and Ambedkar (ed.). 1966. Speeches and Writings of G. K. Gokhale. Bombay:

Asia. Volume 2.

Merriam, A.H. 1980. Gandhi vs.Jinnah. Calcutta: Minerva.

Moon, Penderei (ed.). 1973. Wavell : A Viceroy's Journal. London: Oxford University

Press.

Nairn, C. M. (ed.). 1979. Iqbal, Jinnah and Pakistan. Syracuse: Syracuse University

Page, David. 1982. Prelude to Partition: The Indian Muslims and the Imperial System of

Control , 1920-1932. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Pyarelal. 1956. Mahatma Gandhi: The Last Phase, Volume 1. Ahmedabad: Navjivan.

Pyarelal. 1991. In Gandhiji's Mirror. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

♦♦

42

This content downloaded from

103.68.37.134 on Wed, 03 May 2023 14:38:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Haryana Gazeeter Vol1 and Chapter 1 PDFDocument246 pagesHaryana Gazeeter Vol1 and Chapter 1 PDFThermo MadanNo ratings yet

- University Institute of Legal Studies, ChandigarhDocument15 pagesUniversity Institute of Legal Studies, ChandigarhmanikaNo ratings yet

- Humanity Amidst Insanity: Stories of compassion and hope duringFrom EverandHumanity Amidst Insanity: Stories of compassion and hope duringNo ratings yet

- The People and The Land of SindhDocument32 pagesThe People and The Land of SindhSani Panhwar100% (8)

- Sindh Pdfbooksfree - PKDocument32 pagesSindh Pdfbooksfree - PKShafique Ahmed PitafiNo ratings yet

- Early Maratha-Sikh Relations - Dr. Ganda SinghDocument7 pagesEarly Maratha-Sikh Relations - Dr. Ganda SinghDr Kuldip Singh DhillonNo ratings yet

- Methodology and communities studied in Delhi NCR and AligarhDocument8 pagesMethodology and communities studied in Delhi NCR and AligarhAnubhav JangraNo ratings yet

- Punjab, IndiaDocument23 pagesPunjab, IndiaEktaThakurNo ratings yet

- History, Haryana History, History of HaryanaDocument1 pageHistory, Haryana History, History of HaryanaSatyam ShuklaNo ratings yet

- (Ishtiaq Ahmed) Radcliffe Award & PunjabDocument6 pages(Ishtiaq Ahmed) Radcliffe Award & PunjabKhalil ShadNo ratings yet

- Operation Bluestar 1984Document25 pagesOperation Bluestar 1984Harpreet Singh100% (1)

- Gandhi - Collected Works Vol 20Document487 pagesGandhi - Collected Works Vol 20Nrusimha ( नृसिंह )100% (4)

- Div Train To PakDocument29 pagesDiv Train To PakShubham PandeyNo ratings yet

- Haryana: ST THDocument28 pagesHaryana: ST THHardeep SlariaNo ratings yet

- Early Gandhi Movements in IndiaDocument10 pagesEarly Gandhi Movements in IndiaShreya BansalNo ratings yet

- Three Strange Men: The Lives of Gandhi, Beethoven and CervantesFrom EverandThree Strange Men: The Lives of Gandhi, Beethoven and CervantesNo ratings yet

- Gandhi - The Father of Indian IndependenceDocument3 pagesGandhi - The Father of Indian IndependenceAnmol SenNo ratings yet

- The Mahatma Gandhi and South AfricaDocument19 pagesThe Mahatma Gandhi and South AfricaBishnu KumarNo ratings yet

- Punjabi Religion: Introduction To The ReligionDocument20 pagesPunjabi Religion: Introduction To The ReligionankitashettyNo ratings yet

- Punjab - A History From Aurangzeb To MountbattenDocument755 pagesPunjab - A History From Aurangzeb To MountbattenArjun Lachimalla100% (2)

- Monu Chauhan Sikhism HistoryDocument29 pagesMonu Chauhan Sikhism Historymayankjaggi095875No ratings yet

- GK HryDocument25 pagesGK HryedvikasadNo ratings yet

- Babu History BanjaraDocument17 pagesBabu History BanjaraRahul JadhavNo ratings yet

- Pak resolutionDocument3 pagesPak resolutionasifkhaan0071No ratings yet

- A Historico-Political Retrospection of Deeds of Single Eyed MahatmaFrom EverandA Historico-Political Retrospection of Deeds of Single Eyed MahatmaNo ratings yet

- Sindh 1947 and BeyondDocument18 pagesSindh 1947 and BeyondunknownNo ratings yet

- CasteDocument36 pagesCasteshivamshukla3737No ratings yet

- History of Naushahro FerozeDocument8 pagesHistory of Naushahro FerozeSaadat Ali RizviNo ratings yet

- A Diary of The Partition Days 1947 - Dr. Ganda SinghDocument77 pagesA Diary of The Partition Days 1947 - Dr. Ganda SinghSikhDigitalLibraryNo ratings yet

- Punjab RegionDocument14 pagesPunjab RegionSaket SharmaNo ratings yet

- Punjab: A Brief Overview of India's Northern StateDocument29 pagesPunjab: A Brief Overview of India's Northern StateKunal Mali100% (1)

- Lecture - No 2. Religioun of The WorldDocument10 pagesLecture - No 2. Religioun of The WorldMadina AbbasNo ratings yet

- Gandhi Bio - Tepfer (EDocFind - Com)Document20 pagesGandhi Bio - Tepfer (EDocFind - Com)Naveen KumarNo ratings yet

- A Life with Wildlife: From Princely India to the PresentFrom EverandA Life with Wildlife: From Princely India to the PresentRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Bihar WikipediaDocument24 pagesBihar Wikipediamarch20poojaNo ratings yet

- Master Tara Singhand Partition of Punjab 1947Document6 pagesMaster Tara Singhand Partition of Punjab 1947Dr Kuldip Singh DhillonNo ratings yet

- Refugees of The PartitionDocument9 pagesRefugees of The PartitionYashodhan NighoskarNo ratings yet

- THE NOWHERE PEOPLE: The Story of The Struggle of Post-1965 Pakistani Refugees in RajasthanDocument5 pagesTHE NOWHERE PEOPLE: The Story of The Struggle of Post-1965 Pakistani Refugees in RajasthanwalliullahbukhariNo ratings yet

- Harichand Thakur and the Origins of the Matuya ReligionDocument30 pagesHarichand Thakur and the Origins of the Matuya ReligionParthiva SinhaNo ratings yet

- Dr. B.R. Ambedkar Open University explores India's unity and diversityDocument39 pagesDr. B.R. Ambedkar Open University explores India's unity and diversityshu_sNo ratings yet

- Pakistan's Sindh Province: Overview of History, Population, and RegionalismDocument18 pagesPakistan's Sindh Province: Overview of History, Population, and Regionalismej ejazNo ratings yet

- PunjabDocument5 pagesPunjabdhamalkomaltNo ratings yet

- Hindu Rashtra Darshan PDFDocument157 pagesHindu Rashtra Darshan PDFSankalp100% (2)

- Hindustanis Beyond HindDocument4 pagesHindustanis Beyond HindAsifZaman1987No ratings yet

- AN INTRODUCTION TO INDIAN LITERATUREDocument42 pagesAN INTRODUCTION TO INDIAN LITERATUREReyna Jhane OralizaNo ratings yet

- Business Community: Chapter-VDocument17 pagesBusiness Community: Chapter-VArjun NandaNo ratings yet

- Pak StudiesDocument26 pagesPak StudiesHassan KhanNo ratings yet

- Building The Idea of India1Document35 pagesBuilding The Idea of India1faisalnamahNo ratings yet

- Corrupt Inept Rudderless Politicians: Impediments to India’S Forward MarchFrom EverandCorrupt Inept Rudderless Politicians: Impediments to India’S Forward MarchRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- The ancient wisdom of Brahmin traditionsDocument30 pagesThe ancient wisdom of Brahmin traditionsArun KumarNo ratings yet

- The Frontier Gandhi: My Life and Struggle: The Autobiography of Abdul Ghaffar KhanFrom EverandThe Frontier Gandhi: My Life and Struggle: The Autobiography of Abdul Ghaffar KhanRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Sikh and The Partition of The PunjabDocument9 pagesSikh and The Partition of The PunjabShahrina JavedNo ratings yet

- Hindu Rashtra Darshan by Veer Vinayak Damodar SavarkarDocument130 pagesHindu Rashtra Darshan by Veer Vinayak Damodar SavarkarArya Veer100% (3)

- History of BrahminsDocument58 pagesHistory of BrahminsAntonio JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaDocument30 pagesDamodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaRahaMan ShaikNo ratings yet

- Lahore ResolutionDocument8 pagesLahore ResolutionWassaf ShaikhNo ratings yet

- A Becoming A Future-Hub of MalwaDocument27 pagesA Becoming A Future-Hub of Malwaamarjitdhillon15No ratings yet

- Memories of Rajbanshi QueenDocument11 pagesMemories of Rajbanshi Queenमान तुम्साNo ratings yet

- HEC Degree Attestation Procedure and Application FormDocument43 pagesHEC Degree Attestation Procedure and Application FormMuhammad Tufail Chaudhry71% (7)

- Cashpoints July November PDFDocument908 pagesCashpoints July November PDFAbdul RafayNo ratings yet

- List of Approved Institutions by Hashoo Foundation Scholarship Program 2017 (Higher Studies)Document2 pagesList of Approved Institutions by Hashoo Foundation Scholarship Program 2017 (Higher Studies)Falak NazNo ratings yet

- The Samadhi of Ranjit Singh in LahoreDocument32 pagesThe Samadhi of Ranjit Singh in LahoreIshfaq Naveed GillNo ratings yet

- Details of Akhuwat Loan CentersDocument30 pagesDetails of Akhuwat Loan CentersAbcNo ratings yet

- Textile IndustryDocument9 pagesTextile IndustryMuhammad Irfan HameedNo ratings yet

- List of Voters-Corporate Members '2018 Final Voter' ListDocument223 pagesList of Voters-Corporate Members '2018 Final Voter' Listsaqlain a100% (2)

- AR-423 Legislation and Conservation Sites in PakistanDocument18 pagesAR-423 Legislation and Conservation Sites in PakistanAtique MughalNo ratings yet

- Food Directory of Lahore 2023Document14 pagesFood Directory of Lahore 2023Sajawal ManzoorNo ratings yet

- Brand ManagementDocument40 pagesBrand Managementحسيب مرتضي100% (773)

- Federal Ombudsman Secretariat: List of Focal Persons/Grievance/Liaison Officers of Federal Govt. DepttsDocument22 pagesFederal Ombudsman Secretariat: List of Focal Persons/Grievance/Liaison Officers of Federal Govt. DepttsSajila RoyNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Footwear Manufacturers Association Members ListDocument13 pagesPakistan Footwear Manufacturers Association Members ListHafiz Waqas86% (7)

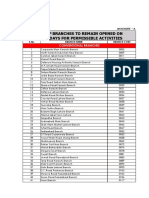

- List of Branches To Remain Opened On Saturdays For Permissible ActivitiesDocument2 pagesList of Branches To Remain Opened On Saturdays For Permissible Activitiesrai shahzebNo ratings yet

- List of AKBL Branches Designated For Same Day Clearing PDFDocument13 pagesList of AKBL Branches Designated For Same Day Clearing PDFANJUM NAWAZ KHAN BALOCHNo ratings yet

- DirectoryDocument117 pagesDirectorySaad Raza Khan100% (1)

- Abdur Rahman ChughtaiDocument1 pageAbdur Rahman ChughtaiÂýëšhãÛšmãñNo ratings yet

- 00 - Contents Everyday Science MCQsDocument5 pages00 - Contents Everyday Science MCQsmimtiazshahid100% (1)

- BSG & Business Group & Regional HeadsDocument6 pagesBSG & Business Group & Regional HeadsmussadaqmakyNo ratings yet

- List of Valid Licensed Importers: Sr. No. Name and AddressDocument4 pagesList of Valid Licensed Importers: Sr. No. Name and AddressAsimNo ratings yet

- List of Mobilink CC CentersDocument1 pageList of Mobilink CC Centersammadsiddique2008No ratings yet

- All-Social Studies-Grade-5Document44 pagesAll-Social Studies-Grade-5sarahada100% (1)

- List of Addl - District and Sessions JudgeDocument32 pagesList of Addl - District and Sessions JudgeCourt Sdk0% (1)

- Regional Offices in Punjab: Name Designation Contact Address Email AddressDocument5 pagesRegional Offices in Punjab: Name Designation Contact Address Email AddressMunir Khan0% (1)

- Final Signature List PUNJABDocument12 pagesFinal Signature List PUNJABPTI Official100% (3)

- A Short Biography of Syed Muhammad LatifDocument3 pagesA Short Biography of Syed Muhammad LatifAizad Sayid100% (1)

- Newspaper Index: A Monthly Publication of Newspaper's ArticlesDocument28 pagesNewspaper Index: A Monthly Publication of Newspaper's ArticlesMalick Sajid Ali IlladiiNo ratings yet

- Gul Ahmed Summer Essential V1 2016Document115 pagesGul Ahmed Summer Essential V1 2016AzizAhmedNo ratings yet

- Top Universities in Pakistan - 2021 Pakistani University RankingDocument8 pagesTop Universities in Pakistan - 2021 Pakistani University RankingMuhammad Iqbal Khan ChandioNo ratings yet

- Expo Exhi 2008Document72 pagesExpo Exhi 2008Engr Umar Iqbal100% (1)