Professional Documents

Culture Documents

AASHTO Guide For Design of Pavement Structures - 1993

AASHTO Guide For Design of Pavement Structures - 1993

Uploaded by

MAULIK RAVAL0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views593 pagesOriginal Title

AASHTO Guide for Design of Pavement Structures - 1993

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views593 pagesAASHTO Guide For Design of Pavement Structures - 1993

AASHTO Guide For Design of Pavement Structures - 1993

Uploaded by

MAULIK RAVALCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 593

A Beret FOR

Cortney |

Pavement -

, SU

PUBLISHED BY THE

/MERICAN ASSOCIATION OF STATE HIGHWAY AND TRANSPORTATION OFFICIALS

Ferchatel La.) CPi!

AASHTO, Guide for

Design of Pavement Structures

1993

Published by the

American Association of State Highway

and Transportation Off

444 N. Capitol Street, N.W., Suite 249

Washington, D.C. 20001

© Copyright, 1986, 1993 by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation

Officials. AU Rights Reserved. Printed in the United States of America. This book, or parts

thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without written permission of the publishers

HIGHWAY SUBCOMMITTEE ON DESIGN

Chairman: Byron C. Blaschke, Texas

Vice Chairman: Kenneth C. Afferion, New Jersey

Secretary: Thomas Willett, FHWA.

Alabama, Don Arkle, Ray D. Bass, J.P. Caraway

Alaska, Rodney R. Platzke, Timothy Mitchell, Boyd

Brownfield

Arizona, Robert P. Mickelson, Dallis B. Saxton,

Joha L. Louis

‘Arkansas, Bob’Waliers, Paul DeBusk

California, Walter P. Smith

Colorado, James E. Sicbels

Connecticut, Earle R. Munroe, Bradley J. Smith,

James F. Byrnes, Jr

Delaware, Michael A. Angelo, Chao H. Hu

D.C,, Charles F. Williams, Sanford H. Vi

Florida, Bill Deyo, Ray Reissemer

Georgia, Walker Scott, Hoyt J. Lively, Roland Hinners

Hawali, Kenneth W.G. Wong, Albert Yamaguchi

Idaho, Richard Sorensen, Jeff R. Miles

Mlinols, Ken Lazar, Dennis Pescitelli

Indiana, Gregory L. Henneke

Towa, George F. Sisson, Donald L. Bast, Dave Little

Kansas, Bert Stratmann, James Brewer,

Richard G. Adams

Kentucky, Charles'S. Raymer, John Sacksteder,

Steve Williams

Louisiana, Charles M. Higgins, William Hickey,

Nick Kalivado

Maine, Charles Smith, Walter Henrickson

Maryland, Steve Drumm, Robert D. Douglass

Massachusetts, Sherman Eidelman,

Frederick J. Nobelty, Jr

Michigan, Charles J. Arnold

Minnesota, Roger M. Hill

Mississippi, Irving Harris, Wendel T, Ruff,

‘Glenn Calloway

issouri, Frank Carroll, Bob Sfreddo

Montana, David S. Johnson, Ronald E. Williams,

Cat's. Pel

Nebraska, Gerald Graver, Marvin J. Vol,

Eldon D. Poppe

Nevada, Michael W. McFall, Steve R. Oxoby

New Hampshire, Gilbert S. Rogers

New Jersey, Kenneth Afferton, Walter W. Caddell,

Charles A. Goessel

New Mexico, Joseph Pacheco, Charles V.P. Trujillo

New York, J. Robert Lambert, Philip J. Clark,

Robert A. Dennison

North Carolina, D.R. (Don) Morton, G.T. (Tom)

Rearin, 1.7. Peacock, Jr

North Dakota, David K.O. Leer, Ken Birst

‘Ohio, Donald K. Huhman, George L.. Butzer

‘Oklahoma, Bruce B. Taylor, Richard B. Hankins,

CC. Wayne Philliber

Oregon, Tom Lulay, Wayne F. Cobine

Pennsylvania, Fred W. Bowser, John J. Faiella, Jr.,

~Dean Schreiber

Puerto Rico, Jose E. Hernandez, Maria M. Casse,

Eugenio Davila

Rhode Island, J. Michael Bennett

South Carolina, Robert L. White, William M. DuBose

South Dakota, Lawrence L. Weiss, Larry Engbrecht,

Monte Schneider

‘Tennessee, Paul Morrison, Clellon Loveall,

Jerry D. Hughes

‘Texas, Frank D. Holzmann, William A. Lancaster,

Mark Marek

U.S. DOT, Robert Bates (FAA), Thomas O. Willett

(FHWA)

Utah, Dyke LeFevre, PK. Mohanty, Heber Viam

Vermont, Robert M. Murphy, Donald H. Lathrop,

John L. Armstrong

Virginia, E.C. Cochran, Jr., R.B. Atherton, K.P, Phillips

‘Washington, E.R. (Skip) Burch

‘West Virginia, Norman Roush, Randolph Epperly

Wisconsin, Joseph W. Dresser, Robert Pfeiffer

‘Wyoming, Donald A. Carlson

AFFILIATE MEMBERS

Alberta, P.F. (Peter) Tajenar

Hong Kong, S.K. Kwei

Manitoba, A. Boychuk

Mariana Islands, Nick C. Sablan

New Brunswick, C. Herbert Page

Newfoundland, Terry McCarthy

Northwest Territories, Peter Vician

Nova Scotia, Donald W. Macintosh

‘Ontario, Gerry MeMillan

‘Saskatchewan, Ray Gerbrandt

ASSOCIATE MEMBERS—STATE

‘Mass. Metro. Dist. Comm., E. Leo Lydon

N.J. Turnpike Authority, Arthur A. Linfante, J.

Port Auth. of NY & NJ, Harry Schmer!

ASSOCIATE MEMBERS—FEDERAL

Bureau of Indian Affairs—Division of

‘Transportation, Kimo Natewa

ULS. Department of Agriculture—Forest Service,

‘Tom Pettigrew

JOINT TASK FORCE ON PAVEMENTS

Region 1

Coitnecteat

New York

Pennsylvan

fort Authority of NY & NI

FHWA

Region 2

Arkansas

Florida

Louisiana

North Carolina

+ Region 3 1

Minois

Towa

California

Oregon

Texas

Utah

‘Washington .

‘Wyoming. i

Representing

‘Transportation Research Board

Standing Committee on Planning

‘Subcommittee on Construction

‘Subcommittee on Maintenance

‘Subcommittee on Materials

Standing Committee on Aviation

‘Members

Charles Dougan

‘Wes Yang

Dennis Morian

Harry Schmert

Louis M. Papet (Secretary)

Robert L. Walters (Vice Chairman)

William N. Lofroos. a

1B, Esnard, Jr.

Ken Creech

John Bbets

George Sisson

Frank L. Carrol!

Aric Morse

Bob Doty

Ira J, Huddleston

Jarnes L. Brown (Chairman)

Les Jester

Newt Jackson

Representatives

‘Tom Hearne

Brain McWaters

Danny Davidson

Wade Betenson

Don Carlson

Daniel W. Dearsaugh, Jr., Senior Program Officer

Fred Van Kirk, West Virginia

Dean M, Testa, Kansas

Robert W. Moseley, Mississippi

Larry Epley, Kentucky

Robert Bates,

Craig Smith, South Dakota

FAA; Roger H. Barcus, Ilinois;

2 aw

SPECIAL NOTICE

‘The Guide for Design of Pavement Structures, when it was published in 1986, was pub-

lished as two volumes. Volume 1 was written as a basic design guide and provided all of the

information required to understand and apply the “Guide” to pavement design. Volume 2 was

a series of appendices prepared to provide documentation or further explanations for informa-

tion contained in Volume 1. Volume 2 is not required for design.

This 1993 edition of the “Guide” contains only one Volume. This Volume replaces the

1986 “*Guide” Volume 1 and serves the same purpose. The major changes included in the

1993 “Guide” are changes to the overlay design procedure and the accompanying appendices

L, M, and N. There are other minor changes and some of an editorial nature throughout the

new Volume 1

‘Volume 2 of the 1986 “Guide” is still applicable to most sections of Volume 1 of the 1993

juide” and is available through AASHTO, 444 N. Capitol Street, N.W., Suite 249, Wash-

ington, D.C. 20001; 202-624-5800. Request book code “GDPS3-V2.” A copy of the Table of

‘Contents from Volume 2 of the 1986 “Guide” follows.

VOLUME 2 APPENDICES

‘AA. Guidelines for the Design of Highway Internal Drainage Systems

BB. —_ Position Paper on Pavement Management

CC. _ Remaining Life Considerations in Overlay Design

DD. _Development of Coefficients for Treatment of Drainage

EE. Development of Reliability

FR _ Relationship Between Resiliemt Modulus and Soil Support

GG, _ Relationships Between Resilient Modulus and Layer Coefficients

HH. Development of Effective Roadbed Soil Moduli

0 Survey of Current Levels of Reliability

wu, Development of Design Nomographs

KK. Determination of J-Factor for Undowelled Pavements

LL. _ Development of Models for Effects of Subbase and Loss of Support

MM. Extension of Equivalency Factor Tables

NN. Recommendations for the Selection of an AASHTO Overlay

Method Using NDT Within the AASHTO Performance

Model Framework

00. Pavement Recycling Fundamentals

PP. Development of NDT Structural Capacity Relationships

PREFACE

_ When construction, maintenance, and rehabilita-

tion costs are considered, the single most costly ele-

‘ment of our nation’s highway system is the pavement

structuré, In an effort to reduce this cost, the state

highway and transportation departments and the Fed-

‘eral Government have sponsored & continuous pro-

gram of research on pavements. One output of that

research effort was the Interim Guide for the Design of

Pavement Structures published in 1972 and revised in

1981. It was based largely upon the findings at the

‘AASHO Road Test.

Because this is such an important topic, the Joint

‘Task Force on Pavements—composed of members

from the Subcommittee on Design, one member each

from the Materials, Construction, and Maiuitenance

Subcommittees, and one from the Planning Commit

tee of AASHTO—was assigned the task of rewriting

the Interim Guide incorporating new developments

and specifically addressing pavement rehabilitation.

Because many states were found to be using at least

portions of the Interim Guide and because no other

generally accepted procedures could be identified, i

was decided that this Guide would retain the basic

algorithms developed from the AASHO Road Test as

used in the Interim Guide. Because the Road Test was

very limited in scope, i.e. a few materials, one sub-

grade, non-mixed traffic, one environment, etc., the

original Interim Guide contained many additional

models to expand the framework so designers could

consider uther conditions. The new Guide has been

further expanded with the following 14 major new

considerations

(2) Reliability

(2) Resilient Modulus for Soil Support

(@) Resilient Modulus for Flexible Pavement

Layer Coefficients

@) Drainage

(5) Improved Environment Considerations

(6) Tied Concrete Shoulders or Widened Lanes

(7) Subbase Erosion for Rigid Pavements

(8) Life Cycle Cost Considerations

(9) Rehabilitation

(10) Pavement Management

(11) Extension of Load Equivalency Values

(12) Improved Traffic Data

(13) Design of Pavements for Low

Volume Roads

(14) State of te Knowledge on Mechanistic-

Empirical Design Concepts

‘The Task Force recognizes that a considerable body

of information exists to design pavements utilizing

so-called mechanistic models. It further believes that

significant improvements in pavement design will

‘occur as these mechanistic models are calibrated to

in-service performance, and are incorporated in

‘everyday design usage. Part IV of this document sum-

marizes the mechanistic/empirical status.

In order to provide state-of-the-art approaches

without lengthy research, values and concepts are

shown that have limited support in research or experi-

ence. Each user should consider this to be a reference

document and carefully evaluate his or her need of

each concept and what initial values to use. To most

effectively use the Guide it is suggested that the user

adopt a process similar to the following:

(1) Conduct a sensitivity study to determine which

inputs have a significant effect on pavement

design answers for its range of conditions.

@) For those inpuis that are insignificant or inap-

propriate, no additional effort is required.

() For those that are significant and the state bas

sufficient data or methods to estimate design

values with adequate accuracy, no additional

effort is required.

(4) Finally, for those sensitive inputs for which the

state has no data of methodology to develop the

inputs, research will be necessary. Because of

the complexity of pavement design and the

large expansion of this Guide, itis anticipated

that some additional research will be cost-

effective for each and every user agency in or-

der to optimally utilize the Guide.

One significant event, the pavement performance

research effort being undertaken in the Strategic High-

vil

‘way Reseatch Program (SHRP), should aid greatly in

improving this dBédment.

‘The Tusk Force’ believes that pavement design is

gradually, but steadily transitioning from an art to a

science. However, when one considers the nebulous

nature of such difficult, but important inputs to design

considerations such as traffic forecasting, weather

forecasting, construction control, maintenance prac-

tices, etc.; successful pavement design will always de-

pend largely upon the good judgment of the designer.

Finally, the national trend toward developing and

implementing pavement management systems, PMS,

appears to the Task Force to be extremely important in

developing the good judgment needed by pavement

designers as well as providing many other elements

needed for good design, i.e. information to support

adequate funding and fund allocation.

The AASHTO Joint Task Force on Pavements

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

One of the major objectives of the AASHO Road

‘Test was to provide information that could be used to

develop pavement design criteria and pavement design

procedures. Accordingly, following completion of the

Road Test, the AASHO Design Committee (currently

the AASHTO Design Committee), through its Sub-

‘committee on Pavement Design Practices, developed

and circulated in 1961 the “AASHO Interim Guide for

the Design of Rigid and Flexible Pavements.” The

Guide was based on the results of the AASHO Road

‘Test supplemented by existing design procedures and,

in the case of rigid pavements, available theory.

‘After the Guide had been used for several years,

the AASHTO Design Committee prepared and

AASHTO published the “AASHTO Interim Guide for

Design of Pavement Structures—1972." Revisions

were made in 1981 to Chapter Ifl of the Guide relative

to design criteria for Portland Cement Concrete pave~

ments. Evaluation of the Guide by the AASHTO De-

sign Committee in 1983 led to the conclusion that

some revisions and additions were required. Repre-

sentations from government, industry, consultants,

and academia led to the conclusion that the Guide

should be strengthened to incorporate information de~

veloped since 1972 and that a new section on rehabili- ”

tation should be added. Itis also pertinent to note that,

based on responses to a questionnaire sent to the

Slates, there was an indication that the Guide was

serving its main objectives and no serious problems

‘were indicated. In other words, the States were geuer-

ally satisfied with the Guide but acknowledged that

some improvements could be made.

Based on the overall evaluation of input from user

agencies and the status of research, it was determined

by the AASHTO Joint Task Force on Pavements that

the revisions to the Guide would retain the AASHO

Road Test performance prediction equations, as modi-

fied for use in the 1972 Guide, as the basic model to

be used for pavement design. This determination also

established the present serviceability index (PSI) as

the performance variable upon which design would be

based.

‘The majc. changes which have been included in the

revised Guive include the following consideration

Reliability. The procedure for design of both

rigid and flexible pavements provides a com-

‘mon method for incorporating a reliability fuc-

tor into the design based on a shift in the

design traffic.

Soil support value. AASHTO test method

T 274 (resilient modulus of roadbed soils) is

recommended as the definitive test for charac-

terizing soil support. The soil property is rec-

‘ommended for use with both flexible and rigid

pavement desis

Layer coefficients (flexible pavements). The

resilient modulus test has been recommended

‘as the procedure to be used in assigning layer

coefficients to both stabilized and unstabilized

material.

(NOTE: Guidelines for relating resilient

‘modulus to soil support value and layer coeffi-

cients are provided in the Guide; however, user

agencies are encouraged to obtain equipment

and to train personnel in order to measure the

resilient modulus directly.)

Drainage. Provision has been made in the

Guide to provide guidance in the design of sub-

surface drainage systems and for modifying

the design equations to take advantage of im-

provements in performance to good drainage.

Environment. Improvements in the Guide have

been made in order to adjust designs as a func-

tion of environment, e.g., frost heave, swelling

soils, and thaw-weakening. Major emphasis is

fiven to thaw-weakening and the effect that

seasonal variations have on performance.

Tied shoulders and widened lanes (rigid pave-

‘ments). A procedure is provided for the design

of rigid pavements with tied shoulders or wid-

ened outside lanes.

Subbase erosion. A method for adjusting the

Gesign equations to represent possible soil ero-

sion under rigid pavements is provided.

Life-cycle costs. Information has been added

relative to economic analysis and economic

comparisons of alternate designs based on life-

10.

u

cycle costs, Present worth and/or equivalent

‘uniform annual cost evaluations during a spec-

ified analysis period are recommended for

making economic analyses.

Rehabilitation. A major addition to the Guide

is the inclusion of a section on rehabilitation,

Information is provided for rehabilitation with

or without overlays.

Pavement management. Background informa-

tion is provided regarding pavement manage-

ment and the role of the Guide in the overall

‘scheme of pavement management.

Load equivalency values. Load equivalency

valies have been extended to include heavier

loads, more axles, and terminal serviceability

levels of up to 3.0.

13,

4

Traffic. Extensive information concerning

methods for calculating equivalent single axle

Toads and specific problems related to obtain-

ing reliable estimates of traffic loading are

provided.

Low-volume roads. A special category for

design of pavements subjected to a relative

small number of heavy loads is provided in the

design section

‘Mechanistic-Empiricul design procedure. The

state of the knowledge concerning mechanis-

-empirical design concepts is provided in

the Guide. While these procedures have not, as,

yet, been incorporated into the Guides, exten-

Bive information is provided as 10 how sych

methods could be used in the future when

enough documentation can be provided,

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Preface... eee vii

Executive Summary .... an : ix

PART I PAVEMENT DESIGN AND MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES

Chapter 1 Introduction and Background.......+.. 13

1.1 Scope of the, Guide 13

1.2 Design Considerations... . 1s

1.3 Pavement Performance. 17

14 Traffic... 110

1.4.1 Evaluation of Traffic 110

1.4.2 Limitations... 12

1.4.3 Special Case: 13

1.5 Roadbed Soil... 113

16 Materials of Construction . HS

1.6.1 Flexible Pavements . 16

1.6.2 Rigid Pavements . 121

1.6.3 Shoulder: ¥2

1.7 Environment . 12

1.8 Drainage 127

1.8.1. General Design Considerations . #28

"2. Design of Pavement Subsurface Drainage. 1:28

1.8.3 Incorporation of Drainage Into Guide 128

1.9 Shoulder Design 129

Chapter 2 Design Related Project Level Pavement Management. . 131

2.1 Relationship of Design to Pavement Management 131

22 The Guide as Structural Subsystem for a Sute Project-Level PMS . 134

2.3. Pavement Type Selection..........- eateets 139

2.4 Network Level Pavement Management... .. 1:39

Chapter 3 Economic Evaluation of Alternative Pavement Design Strategies... I-41

3.1 Introduction, . 41

3.2 Life-Cycle Costs 141

3.3 Basic Concepts. : MI

34 Definitions Related to Economic Analysis. 142

3.4.1 Transport Improvement Costs 142

3.4.2 User Benefits....... 142

3.5. Factors Involved in Pavement Cost and Benefits 144

3.6 Intl Capital Costs Qavestment Cost) 144

3.6.1 Maintenance Coat . 144

eae?)

Contents—Continued

3.6.3 Salvage or Residual Value. . 145

3.6.4 User Cost... : ciieieteseteeesreree TAS

3.6.5. Traffic Delay Cost to User. 146

3.6.6 Identification of Pavement Benefit 1.46

3.6.7 Analysis Period .......0..00.00cceclcseereessereererseesees 146

3.7. Methods of Economic Evaluation 147

3.8 Discussion of Interest Rates, Inflation Factors and Discount Rates ......... 1-47

3:8. Discounting andthe Opportonty Con of Capital... -------voos TT

3.8.2 Inflation ........ cotettetceeeigeeees 4B

39 : - cece 149

3.9.1 Equivalent Uniform Annual Cost Method. : 149

3.9.2 Present Worth Method : 149

3.9.3 Summary oo... eececenee veceee eens coe ESI

Chapter 4 Reliability 183

4.1 Definitions 153

4.1.1 General Definition of Reliability 153

4.1.2. Definition of Design Pavement Section. 153

4.1.3 Definition of Pavement Condition, Accumulated Axle Loads, and

Pavement Performance Variables feo 154

4.2 Variance Components and Reliability Design Factor 156

4.2.1 Components of Pavement Design-Performance Variability .......... 1-36

4.2.2 Probability Distribution of Basie Deviations ...... 137

4.2.3 Formal Definition of Reliability Level and Reliab

Design Factor. 160

43 Criteria for Selection of Overall Standard De 162

4.4 Criteria for Selection of Reliability Level ......0.0.0000+ ; 162

45 Reliability and Stage Construction Alternatives REREEINID pea

Chapter § Summary. see 168

References for Part I. . . 1-57

PART IL PAVEMENT DESIGN PROCEDURES FOR

NEW CONSTRUCTION OR RECONSTRUCTION

Chapter 1 Introduction 13

LL Background....... 0.0.0. ee tenes ceeeeee m3

1.2 Scope : 13

13° Limitations .............. 4

1.4 Organizat 14

Chapter 2 Design Requirements. . Us

2.1 Design Variables coerce WS

2.1.1 Time Constraints . a see . seeee nS

16

een : 19

Environmental Effects... u-10

2.2 Performance Criteria. 10

221 Servicesbility 0.0.0.0. 2. Heo

2.2.2 Allowable Rutting ........ 2 M12

Ageregate Loss wi

Contents—Continued

2.3. Material Properties for Structural Design .

2.3.1 Effective Roadbed Soil Resilient Modulus .

2.3.2 Effective Modulus of Subgrade Reaction

2.3.3. Pavement Layer Materials Characterization

2.3.4 PCC Modulus of Rupture.......

213.5 Layer Coefficient

2.4 Pavements Structural Characteristics .

2.4.1 Drainage:

2.4.2 Load Transfer ....

2.4.3 Loss of Support...

2.5 — Reinforcement Variables

2.5.1 Jointed Reinforced Concrete Pavements .

2.5.2 Continuously Reinforced Concrete Pavements

Chapter 3. Highway Pavement Structural Design .

3.1 Flexible Pavement Design .....-

BALL Determine Required Structural Number -

3.1.2 Stage Construction .

3.1.3 Roadbed Swelling and Frost Heave

3.1.4 Selection of Layer Thickness .

3.1.5 Layered Design Analysis

3.2. Rigid Pavement Design

3.2.1 Develop Effective Modulus of Subgrade Reaction...

3.2.2 Determine Required Slab Thickness . :

3.2.3 Stage Construction

3.2.4 Roadbed Swelling and Frost Heave .

3.3. Rigid Pavement Joint Design. ..

3.3.1 Joint Types

3.3.2 Joint Geometry .....

3.3.3 Joint Sealant Dimensions

3.4 Rigid Pavement Reinforcement Design ...

3.4.1 Jointed Reinforced Concrete Pavements

3.4.2 Continuously Reinforced Concrete Pavements

‘Transverse Reinforcement. . :

3.5 Prestressed Concrete Pavement.

3.5.1 Subbase ... :

3.5.2 Slab Length ....

3.5.3. Magnitude of Prestress .

3.5.4 Tendon Spacing . .

3.5.5 Fatigue ..

3.5.6. PCP Structural Design

11-69

1-69

11-69

v.69

- 177

. 1-77

I-81

1-81

Chapter 4 Low-Volume Road Design .......+

4.1 Design Chart Procedures...

4.1.1. Flexible and Rigid Pavements

4.1.2 Aggregate-Surfaced Roads

4.2 Design Catalog.......

4.2.1. Flexible Pavement Design Catalog.

4.2.2 Rigid Pavement Design Catalog.

42.3 Aggregate-Surfaced Road Design Catalog

References for Part Il.....

xii

Contents—Continued

PART III PAVEMENT DESIGN PROCEDURES FOR

REHABILITATION OF EXISTING PAVEMENTS

Chapter 1 Introduction

1:1 Background.

1.2 Scope.......2.

1.3 Assumptions/Limitations : we :

1.4 Organization

mL

m7

m7

Chapter 2 Rehabilitation Concepts ..

2.1 Background...-2...226.+

2.2 Rehabilitation Factors.

co IL

2A Major Categories... cceeeecesceseeseetees cece HE

2.2.2 Recycling Concepts. m7

2.2.3 Construction Considerations. m7

2.2.4 Summary of Major Rehabilitation Factors UL

2.3. Selection of Alternative Rehabilitation Methods tecteeseees U8

Overview ; M18

Problem Definition... = eens nL-9

Potential Problem Solutions me I M2

Selection of Preferred Solution ..........cccccccccceseeeeseees MEAS

Summary ‘i : 11-16

Chapter 3. Guides for Field Data Collection ......sssesceseeeseesceeseees IAD

BL Overview oo eeeeceee eee ceeteteteeeereee oe M9

3.2. The Fundamental Analysis Unit... m9

3.2.1 General Backgrourid span eroneaien oeeeemeese Oe T119)

3.2.2 Methods of Unit Delineation .-. m1 19

3.3. Drainage Survey for Rehabilitation. 21

tion.

3.3.1 Role of Drainage in Rehabil met

3.3.2 Assessing Need for Drainage Evaluation ........... M25

3.33, Pavement History, Topography, and Geometry... - m5

3.3.4 Properties of Materials .. 1-25

3.3.5. Climatic Zones 1-26

3.3.6 Summary - 0128

3.4 Condition (Distress) Survey. so E28

3.4.1 General Background .... : 1-28

3.4.2 Minimum Information Needs. - = 1-28

3.4.3 Utilization of Information... 2 HE28

3.5 NDT Deflection Measurement = 1-30

3.8.1 Overview ..... : 111-30

3.5.2 Uses of NDT Deflection Results 11-32

3.5.3 Evaluating the Effective Structural Capacity . severe IIEDS

3.8.4 Joint Load Transfer Analysis 1-38

3.8.8 Use in Slab-Void Detection ........ mas

3.6 Field Sampling and Testing Programs . ms

3.6.1 Test Types mas

3.6.2 Major Parameters... m-45

3.6.3. Necessity for Destructive Testing ........s.s.s. ceeeeees MEAD

3.6.4 Selecting the Required Number of Tests Ceeseteeeses HRAD

Contents—Continued

Chapter 4 Rehabilitation Methods Other Than Overlay

cere TILS9

4.1 Evaluation of Pavement Condition

4.1.1 Surface Distress.

4.1.2. Structural Condition

4.1.3 Functional Condition .

4.2. Development of Feasible Alternati

4.3. Major Nonoverlay Methods.

43.1 Full-Depth Repair... -/e+er01

4.3.2. Partial-Depth Pavement Repair. 1-64

43.3 Joint and Crack Sealing ..... 11-65

4.3.4 Subscaling of Concrete Pavements. 111-66

433 Diamond Grinding of Concrete Surfaces and Cold Milling of

Asphalt Surfaces ...--..-+ n-67

Subdrainage Design. . 11-68

Pressure Relief Joints 111-69

Restoration of Joint Load Transfer 111-70

4.3.9 Surface Treatments . ~ eT

43.10 Prédiction of Life of Rehabilitation Techniques Without Overlay... 111-73

Chapter 5 Rehabilitation Methods With Overlays . seeeseetesee ILTD

5A

5.2

53

54

Overlay Type Feasibility .

Important Considerations in Overlay Design.

5.2.1 Pre-overlay Repair

5.2.2 Reflection Crack Control

3. Traffic Loadings ...

‘4. Subdrainage .

‘5 Rotting in AC Pavements -

6

7

Recycling the Existing Pavement -

‘Structural versus Functional Overlays.

111. Existing PCC Slab Durability

12 PCC Overlay Joints...

.2.13 PCC Overlay Reinforcement .

5.2.14 PCC Overlay Bonding/Separation Layers... :

15 Overlay Design Reliability Level and Overall Standard Deviation... 19-82

5.2.16 Pavement Widening . —

5.2.17 Potential Errors and Possible Adjustments wo Thickness

Design Procedure . beveessteenees

5.2.18 Example Designs and Document

Pavement Evaluation for Overlay Design. ..

5.3.1 Design of Overlay Along Project. .

5.3.2 Functional Evaluation of Existing Pavemen

5.3.3 Structural Evaluation of Existing Pavement

5.3.4 Determination of Design Mg -...-.

‘AC Overlay of AC Pavement...

5.4.1 Feasibility.......

5.4.2 Pre-overlay Repair.

5.4.3 Reflection Crack Control .

5.4.4 Subdrainage cee

Thickness Design

35

5.6

53.7

5.8

5.9

5.10

Contents—Continued

5.4.6 Surface Milling .....0..0.000 a UL-105

5.4.7 Shoulders veeeeeeee see M105

5.4.8 Widening ae feces E106

‘AC Overlay of Fractured PCC Slab Pavement foeegeeeeees HE106

5.5.1 Feasibility... ve 1-107

5.5.2 Pre-overlay Repair : 1-108

5.5.3. Reflection Crack Control ... + IH-108

5.5.4 Subdrainag> .. - HL-108

5.5.5. Thickness Design cece co ceee eee cees M108

5.5.6 Shoulders : Ueut

5.5.7 Wi veceteeeeteseees MEU

[AC Overlay of JPCP, JRCP, and CRCP..... 2 MEU

5.6.1 Feasibility. . ceteeetetetenes - HES

5.6.2 Pre-overlay Repair m3

5.6.3 : vosceseeevees MELA

5.6.4 Subdrainage . eee Us

5.6.5 Thickness Design Mes

5.6.6 Shoulders.......... 1-125

5.6.7 Widening M125

AC Overlay of ACI ~ M125,

5.7.1 Feasibility, : ceveeteseeeeee MEI2S

5.7.2 Pre-overlay Repair. 1-127

5.7.3 Reflection Crack Control WL-127

5.7.4 Subdrainage : feceecstesteesseseeseeeee HIEI28

5.7.5 Thickness Design 01-128

5.7.6 Surface Milling. n135

5.7.7 Shoulders s peeenerereeree HL135

5.7.8 Widening .... voce eee M36

Bonded Concrete Overlay of JPCP, JRCP, and CRCP «2. 2..ccevevesee 11136

5.8.1 Feasibility, 1-136

Pre-overlay Repait........c00ec00 050 , W137

Reflection Crack Control 237

Subdrainage .. veiteceeeeeess UF?

Thickness Designo... ..00..ccseceeee os 5 m1-137

Shoulders... BES SDO SES SEG Hao Hex ESOCOSHEOAE 1-143

Joints 1-143

Bonvling Procedures and Material .............-sceeseseeeseee m-145

Widening . M145

Unbonded JPCP, JRCP, or CRCP Overy of JPCP, RCP, CRCP,

or ACIPCC coteeeueeeeeteecttaeeies Wr-145

5.9.1 Feasibility. ‘ 2 4S

5.9.2 Pre-overlay Repair... 145,

5.9.3 Reflection Crack Control . W-145

5.9.4 Subdrainage ....... ee Si iotukesese DTD 14s:

5.9.5 Thickness Design { mut meas

5.9.6 Shoulders .. M-ASL

5.9.7 Joints MLS

Reinforcement 11-153

Separation Interlayers 11-153

5.9.10 Widening ee m1-153

JPCP, IRCP, and CRCP Overlay of AC Pavement 11-153

5.10.1 Feas ; eb 1-153

Contents—Continued

5.10.2 Pre-overlay Repait.....0.00.0000eeeseeeeessees cee HEI53

5.10.3 ‘Crack Control... vieveeeeesseseeseeeees HEI5S3

5.10.4 coe Mm1-154

$.10.5 Thickness Design - pee teeecrerees MEISE

5.10.6 Shoulders : 11-155

5.10.7, Joints M1155

5.10.8 Reinforcement TL-155

5.10.10 Widening « 1-155

cnc 50 ee teres TLIS7,

References for Chapter 5.

PART IV MECHANISTIC-EMPIRICAL DESIGN PROCEDURES

1.1 Introduction ceveyessees eee . V3

1.2 Benefits = Dicstteceeseee IW

113. Framework for Development and Application ene a Iv-4

1.4 Implementation. Gre pcopsccececcecnoeo9 wa

1.4.1 Défign Considerations . : Dicceereeeee IVB

1.4.2 Input Data . —_ 7 boreesoo0cc V8

1.4.3 Equipment Acquisition cee en : v9

1144 Computer Hardware and Software veces oe v9

1.4.5 Training Personnel : Bec asppaEADSOEGICO v9

1.4.6 Field Testing and Calibration : foteeseeeseeses EVO

1.4.7 Testing es ~ IV-10

1.5 Summary IV-10

References for Part IV ....- eS seveceseeeseeenee EVEL

APPENDICES

‘A. Glossary of Terms .... eel

B. Pavement Type Selection Guidelines . cee a BI

CC. Alternate Methods of Design for Pavement Structures... a ca

D. Conversion of Mixed Trafic to Equivalent Single Axle Loads for

Pavement Design ....-.+++ Di

B, _Poslion Paper on Shoulder Design pa eeenatteemen ees TE!

F. List of Test Procedures ...... fn FI

G. Treatment of Roadbed Swelling and/or Frost Heave in Design. .....-..... GU

H. Flexible Pavement Design Example ..... een HI

1. Rigid Pavement Design Example .. fetes OW

J. Analysis Unit Delineation by Cumulative Differences... a u

K. Typical Pavement Distress Type-Severity Descriptions ........-..--.005. Ki

L. Documentation of Design Procedures - LI

M. An Examination of the AASHTO Remaining Life Factor ML

N. Overlay Design Examples oe : NI

PART I

PAVEMENT DESIGN AND

MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES

CHAPTER 1

1.1 SCOPE OF THE GUIDE

‘This Guide for the Design of Pavement Structures

provides a comprehensive set of procedures which can

be used for the desiga and rehabilitation of pavements,

both rigid (portland cement concrete surface) and

flexible (asphalt concrete surface) and aggregale wu

faced for low-volume roads. The Guide has been de-

veloped to provide recommendations regarding the

Aetermination of the pavedien structure as showa in

Figure 1-1. These recommendations will include the

determination of total thickness ofthe pavement struc:

ture as well as the thickness of the Individual struc-

tural componems, The procedures for design provide

for the determination of alrnate siructures using &

vatlely of materials and construction procedures

‘A glossary of terms, as used in this Guide, is pro

vided in Appendix A. ILis recognized that some ofthe

terms used herein may differ from those used in your

focal practice; however, itis necessary 10 estublish

standard terminology in order to facilitate preparation

af the Gude for nationwide use, Insofar as ls posible,

‘AASHTO definitions have been used herein.

Tt should be remembered that te toll set of con-

siderations requted to assure reliable performance of

a pavement siructure will include many fictors other

than’ the determination of layer thicknesses of the

structural components Por example, material require

tents, construction requirements, and quality control

Will signiticanl itluence te ability ofthe pavernent

Structure to perform according o design expectations

Ta other words, “pavement design” involves more

than choosing thicknesses. Inforrution concerning

material and construction requirements wil be briefly

described in this Guide; however, « good pavement

designer must be familiar with relevant publications of

AASHTO and ASTM, as well as the local agencies,

ie. slate agencies or countes, for whom the design is

being prepared. It is extremely important thi the

designer prepare special provisions to the standard

specifications when circumstances indicate Uh non

Standard conditions exist fora specific projet. Exam-

ples of such a condition could invulve a roadbed soit

Which is known to be expunsive or nonstandard mate-

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

rials which are to be stabilized for use in the pavement

tructure or prepared roadbed.

Part I of this Guide has been prepared as general

background material to assist the user in the proper

interpretation of the design procedures and to provide

‘an understanding of the concepts used in the develop-

ment of the Guide. Detailed information related di-

rectly to a number of design considerations, e.g.,

reliability, drainage, life-cycle costs, traffic, and pave-

‘ment type selection, will be found in the Appendices.

References used in the preparation of the Guide can be

found following each of the four major Parts

Part I, Chapter 3 of the Guide provides information

concerning economic evaluation of alternate pavement

design strategies. It should not be concluded that the

selection of a pavement design should be based on

economics alone. There are a number of consider-

ations involved iu the final design selection. Appendix

B of the Guide on pavement type selection provides an

extensive list of guidelines which should be used in

comparing alternate design strategies.

Part Il of this Guide provides a detailed method for

the design of new pavements or for reconstruction of

existing pavements on the existing alignment with new

or recycled materials.

Past III of this Guide provides alternative methods

for pavement rehabilitation with or without the addi-

tion of an overlay. The methodology used in this part

of the Guide represents the state of the knowledge

regarding the deterioration of pavement structure

before and after an overlay has been applied. It is

recognized that there are alternate methods for the

determination of overlay requirements; a number of

these methods are cited in Appendix C. The method

included in Part III is somewhat more basic in concept

than other existing methods and has the capability for

broader application to different types of overlays,

e.g., flexible on rigid, flexible on flexible, rigid on

rigid, and rigid on flexible type pavements. The

method is also compatible with the performance and

‘design concepts used in Part II. In this way, consider

ation of such factors as drainage, reliability, and

traffic is the same for both new and rehabilitated

(overlayed) pavement structures.

1

Design of Pavement Structures

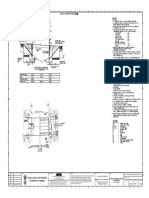

" aanionung maureaey 2qP>Ld 40 prBpy 40} wonDag yeovdA] “TT aunBpy

sia uBss9g jemonas,

3407S LAD Li

aagavoe -1z 3401S HOLIO 01

Bbeuiep eaepnsans 10) AvMavoH - 02 AVIS INIWBAVE 6

‘Worsnord gum vORD@s Jo SerGUIEXe YR0INGES - 6! agynoo s0vsuns “8

FET amnbig 00S "BON S3NVT T3AVEL > 8! asunoo 3Sve-L

3401S HIOINOHS © Lt asvaans 3

BUNLONLS INBWIAVS 9: ONIDVSENS UZCTNOHS ° Ss

WOS Q380VOU - Si caBavOY ORUVEsuE HO TWINALYIN G3L9373S °F

3OVEOENS - i Blof

3401S NMOHD ° £1 aNnows TwNIDIEO - Z

39v8 YICTNOWS Zi 3401S Tid

vonsag wewaneg ping

QZ VP,

Introduction and Background

Stute of the art procedures for rehabilitation of

pavement structures without overlay, including drain-

age and the use of recycled material, are emphasized

in Part Ill. These techniques represent an alternative

to overlays which can reduce long-term costs and sat-

isfy design constraints associated with specific design

situations.

‘As an adjunct to pavement rehabilitation it is im-

portant to first determine what is wrong with the exist-

ing pavement structure. Details of the method for

interpretation of the information are contained in Part

IIL. A procedure for measuring or evaluating the con-

dition of a pavement is given in Appendix K and

Reference 1. It is beyond the scope of this Guide to

discuss further the merits of different methods and

‘equipment which can be used to evaluate the condition

of a pavement, However, it is considered essential that

‘4 detailed condition survey be made before u set of

plans and specifications are developed for a specific

project. If at all possible, the designer should partici-

pate in the condition survey. In this way, it will be

possible to determine if special treatments or methods

may be appropriate for site conditions, specifically, if

conditions warrant consideration of detailed investig

tions pertinent to the need for added drainage features.

Part IV of this Guide provides a framework for

future developments for the design of pavement struc-

tures using mechanistic design procedures. The bene-

fits associated with the development of these methods

tare discussed; a summary of existing procedures and

framework for development are the major concerns of

that portion of the Guide.

1.2. DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS

The method of design provided in this Guide in-

cludes consideration of the following items:

(1) pavement performance,

@) traffic,

3) roadbed soil,

(4) materials of construction,

(5) environment,

(6) drainage,

(1) reliability,

(8) life-cycle costs, and

(9) shoulder design.

Bach of these factors is discussed in Part I, Parts II,

IL, and IV carry these concepts and procedures for-

ward and incorporate each into a pavement structure

design methodology.

45

It is worth noting again that while the Guide de-

soribes and provides a specific method which can be

used for the determination of alternate design or reha-

bilitation recommendations for. the pavement stru

ture, there area number of considerations which are

left to the user for final determination, e.g., drainage

coefficients, environmental factors, and terminal

serviceability.

‘The Guide by its very nature cannot possibly in-

‘clude all of the site specific conditions that occur

in each region of the United States. It is therefore

necessary for the user to adapt local experience to the

use of the Guide. For example, local materials und

environment can vary over an extremely wide range

within a state and between states,

‘The Guide attempts to provide procedures for eval-

uuating materials and environment; however, in the

case where the Guide is at variance with proven and

documented local experience, the proven experience

should prevail. The designer will need to concentrate

‘on some aspects of design which are not always cov-

ered in detail in the Guide, For example, material

requirements and construction specifications are not

detailed in this Guide and yet they are an important

consideration in the overall design of & pavement

structure. The specifies of joint design and joint spuc-

ing will need careful consideration. The effect of sea~

sonal variations on material properties and careful

evaluation of traffic for the designed project are de-

tails which the designer should investigate thoroughly.

The basic design equations used for flexible and

rigid pavements in this Guide are as follows:

Flexible Pavements

LogioWiy) = Ze X Sy + 9.36 x logy(SN + 1)

i APSI

e042 — 15.

= 0.20 4 ——

1094

40+

040+ ae DP

4+ 2.32 % logig( Ma) — 8.07 (1.2.1)

where

Wis = predicted number of 18-kip equivalent

single axle load applications,

standard normal deviate,

combined standard error of the traffic

prediction and performance prediction,

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5811)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Appendix - B1 - Typical Cross SectionDocument5 pagesAppendix - B1 - Typical Cross SectionMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Tendernotice 2Document98 pagesTendernotice 2MAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Tendernotice 5Document1 pageTendernotice 5MAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Tendernotice 1Document2 pagesTendernotice 1MAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Schedule For Testing of MaterialsDocument7 pagesSchedule For Testing of MaterialsMAULIK RAVAL100% (1)

- Tendernotice 4Document152 pagesTendernotice 4MAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Eprocurement System Government of IndiaDocument2 pagesEprocurement System Government of IndiaMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Indian Port Rail & Ropeway Corporation LTDDocument4 pagesIndian Port Rail & Ropeway Corporation LTDMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- VOL-II-Qualification DocumentDocument27 pagesVOL-II-Qualification DocumentMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Cement ConsuptionDocument12 pagesCement ConsuptionMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Government Eprocurement SystemDocument2 pagesGovernment Eprocurement SystemMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- 10 Testing ScheduleDocument3 pages10 Testing ScheduleMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Project Information Sheet - IPRCLDocument1 pageProject Information Sheet - IPRCLMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Asphalt ConsuptionDocument1 pageAsphalt ConsuptionMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Cover Page Valsad RobDocument11 pagesCover Page Valsad RobMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Appendix - A1 - Index PlanDocument1 pageAppendix - A1 - Index PlanMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- 2.all Specification Valsad RobDocument257 pages2.all Specification Valsad RobMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- 02 Vol II - PART 1 Technical Specs Road WorksDocument185 pages02 Vol II - PART 1 Technical Specs Road WorksMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Office of The Executive Engineer (R&B) Division: ValsadDocument2 pagesOffice of The Executive Engineer (R&B) Division: ValsadMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Pre - Qualification Bid: Government of GujaratDocument49 pagesPre - Qualification Bid: Government of GujaratMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- 1.cover Page - Valsad RobDocument5 pages1.cover Page - Valsad RobMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Section-I Notice Inviting Tender (Nit)Document3 pagesSection-I Notice Inviting Tender (Nit)MAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- 01 Vol I ITB R0 (P3.1 - Genda Circle)Document102 pages01 Vol I ITB R0 (P3.1 - Genda Circle)MAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Tendernotice 1Document1 pageTendernotice 1MAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Specification IndexDocument13 pagesSpecification IndexMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Pre Qualification Bid FORDocument44 pagesPre Qualification Bid FORMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- NIT23Corr 1Document1 pageNIT23Corr 1MAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- DTP Form B2Document54 pagesDTP Form B2MAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- 05 VolII - Preamble To Price BidDocument6 pages05 VolII - Preamble To Price BidMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet

- Appendix B3 GAD Major BridgeDocument6 pagesAppendix B3 GAD Major BridgeMAULIK RAVALNo ratings yet