Professional Documents

Culture Documents

B Tiger Hunter - Inspired by True Events - Gregory Tinsley

Uploaded by

Nakul Raibahadur0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

52 views324 pagesOriginal Title

B Tiger Hunter_ Inspired by True Events - Gregory Tinsley

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

52 views324 pagesB Tiger Hunter - Inspired by True Events - Gregory Tinsley

Uploaded by

Nakul RaibahadurCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 324

Royal Bengal tigers ruled nearly 500,000 square miles of

India in 1600, the year Queen Elizabeth chartered the

British East India Company.

Throughout the next 300 years tigers slaughtered the

people of India at an estimated rate of eight fatalities per

day and claimed approximately 15 million domestic

animals.

Be on your guard; stand firm in the faith;

be men of courage; be strong.

1 Corinthians 16:13

For Terri, Sara, Megan and Brooks

In memory of Bob and Madolyn Tinsley

Mr. and Mrs. George B. Dyer

O. Wayne Lee

Special Author’s Edition

TIGER

HUNTER

Confirmed Killed & Missing: 761

Consecutive Days of Operation: 4,467

Area: 500 square miles, remote upland jungle

Human Populace Paralyzed by Horror: 107,326

Assailants: man-eating megafauna (2)

Ultimate Salvation: Jim Corbett

Inspired by True Events

Gregory E. Tinsley

Copyright © MMXIV by Greg Tinsley

All rights reserved

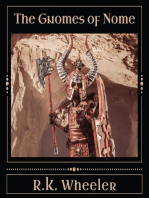

The painting for the cover of this book was commissioned

by Jacobus Verkade of the Netherlands as part of a wildly

successful collector-card marketing campaign for his

family’s cookie company. Koningstijger No. 34 from

Verkade’s Album was first published in 1939, the same

year in which the story TIGER HUNTER is set.

Mohini’s Pleasures and the

Dance of the Sudarshana Chakra

Those passengers of the royal howdahs who are not doped

half asleep by the early start and the smooth motion of

colossal animals are mostly daydreaming of sensual

promiscuities:

The Rajah, for instance, is rapturously considering the

curvatures of the most provocative of his wives; while the

introspections of the Rajah’s principal business associate,

the party’s second gun, involve karma-sutra-like hijinks

with his own mistress among the pressed cotton sheets of

a five-star rendezvous in Delhi. At the creaking rear of the

swaying tower, the howdah’s teenage gun bearer,

snuggled warm as a bedstone against the cold mountain

air of northeastern India, is fighting a losing battle to keep

open his eyes.

Doranda, the Maharajah’s chief of security, fifty yards to

the left of the Rajah on an outsized Sumatran elephant, is

struck suddenly by a phantom draft of the perfume of the

Rajah’s fourth wife, who is undoubtedly soaking in a

warm bath at the palace. The Rajah’s most outgoing

spouse, on the deck behind Doranda, is recovering her

appetites. Six, as she is often referred to by the stable

boys, is intermittently imagining what she would do to a

dish of peeled fruit and the bodyguards.

The Rajah’s senior prince, accompanied by another armed

defender and the family priest, uncomfortably rides the

elephant

1

that represents the most forward starboard wing of the

trundling grey wall.

Even under the arousals of elephantry and tigers the

majority of these key-man adventurers are experiencing

the hunter’s power paradox: Men bound of wildernesses

and hunting camps are often tortured with suggestive

thoughts of women. Conversely, when men are

socializing in more sexually accommodating settings they

invariably discuss only hunting.

Darya, the most experienced mahout in northeast India,

the driver of the wisest and largest African savanna

elephant in the Rajah’s fleet, a pachyderm named Go

Ankus, is not technically in the howdah. Darya is seated

on the prickly nap of the lead gaja, his knees tucked right

behind the great bull’s leathery earflaps. There, Darya

may periodically incentivize the beast by rapping or

pricking the sacred monster’s cranium with an antique

elephant goad known regionally as the ankusha.

Given to more than thirty years of daily devotion and

discipline, Darya and Go Ankus are a battery at the height

of professional accomplishment. They are also the only

two beings of the royal hunting procession who are

completely in the moment.

Darya and Ankus are leading a delegation of sportsmen

who had previously completed an on-time sunrise

departure in a varnished retinue of gold-trimmed, horse-

drawn carriages from the Rajah’s luxurious spike camp at

the Sarak Road; overtaking the listless spear point of fifty

elephants held for them in a side canyon of the Bilaspur

River. Their target is a specific tiger, a gradually more

belligerent young-adult male who had begun stealing

chickens in the early fall of 1936, but whose weekly

intake of domestic product lately includes goat, donkey,

cattle and a successful shopkeeper’s attraction of trick

monkeys. Worse, the super carnivore’s once discreet

nature is now quite diurnal and menacing.

The tiger needed hunting, if not killing, and the Raja was

obliged and extremely capable of bringing it an active

campaign.

Uneventfully, they’ve pushed this parcel of pristine

upland for more than one hour and they are still well

away from

the tiger baits. So it is a multiplying surprise when the

beast

2

that comes through the dense understory, ascending the

craggy trunk of Ankus to overrun the Rajah’s ornate

howdah, is not a tiger but a very big leopard.

The tall, dewy grasses sizzle slightly rather than rustle as

the cat rushes through the low brush and up Go Ankus’s

leaden expression, a derisive shadow of smoke that leaves

the head of Darya jangling betwixt his shoulders.

Painted brightly with Darya’s gore, the speckled thresh-

ing machine takes on a hyper motion, unleashing its war

cry just above the huddled Rajah, alighting in a shattering

percussion of growls and shrieks to disintegrate the left

wrist and shoulder of the Raja’s business associate, who

implodes rearward with the cat attempting to swallow his

face.

The emphatic howl of bloody murder is joined by every

man and animal in this pitched jungle, and overtopping

the voice and hue of these horrors is the splitting tantara

of the gaja Go Ankus, who outrageously dances

backwards upon his hindlimbs before pirouetting to

frantically trample everything in the grass that somewhat

resembles a leopard – the business associate, the gun

bearer and his beloved Darya.

The wealthy prince is a practiced marksman. Due to the

likeliness of a deflected bullet, however, he misses the

orange brushstroke of cat as it screeches outwards to the

unarmed line of hulkaras behind them. His luck improves

with Go Ankus, who he has known since childhood. The

out-of-control destroyer is in crazed pursuit of the leopard

when the crack of the heir’s solid brings a plume of dust

off the elephant’s temple and plants him, spilling the

Rajah and his .577-caliber pistol headfirst down the

slipface of his fallen mount.

By miracle the gun bearer and the Rajah find themselves

unscathed. The sudden deaths of Darya and Go Ankus –

which within the week will be distilled to columns of type

and published by every news organization in England and

India – brings the sobbing prince to his knees.

But the real foible in the reporting is that the

businessman’s most grotesque wound will be lost to the

exaggerated

myth of the attack, untold except by those who first move

to him

as he temporarily shuffles through the superheated

battlefield.

3

Dangling from its ocular nerve, the man’s dislodged left

eye hangs like a bell striker at the center of his punctured

cheek, soon blacking him out and ending the futile search

for his missing spectacles – and his feral eyeball.

After much discussion, the royal surgeon puts his

unproven skills for ophthalmology on display, returning

the poor man’s itinerant organ to its orbit and stabilizing

the mutilation with lengths of the prince’s turban.

Mopping his sweat-sheen face with unbloodied

shirtsleeves, the medical authority speaks with sincere

amazement about how quickly these things happen.

He compares the violence to a blow by Vishuakarma’s

ultimate weapon, the sudarshana chakra, a mythological

discus ringed with opposing bands of spinning razor teeth.

The top man from the line of beaters, a barefooted

greybeard widely respected for his clarity and woodcraft,

overhears the surgeon’s last remark as he enters the

presence of the kings, catching his breath and hitching up

his tatty khadi trousers.

No, says the lithe boss of the hulkaras: Vishuakarma, the

architect of the gods, is not directly responsible for this

tragedy.

The tracks of murderer, the sage confirms, are those of the

Thak Leopard.

4

4

Camp Golden Mahseer

Corbett is studying his numb feet atop a flat of raw

marble, the complicated hymn of the surrounding river

coursing through him. He coughs up a good bit of sticky

water and closes his bulging eyes to gradually recover his

balance point, which he finds beneath the river’s verse

and chorus in the imagined peel of a subduction outro that

folds a thousand-mile husk of sea floor right into the

billowy vault of heaven.

He eventually levels himself and strums his toes in

celebration of not being drowned by the river. He resets

his spirit, carefully inspecting the demarcation of the

closest of the canyon’s rims. Himavat, he unexpectedly

remembers, is the most ancient overlord here. Himavat

the god who once authorized a deity to ride the wife of

another man to a faraway cave in the cliffs – following the

woman’s metamorphosis into a flying tigress – on the

pretense of consummating a treaty with the tiger demons.

That the devotees of such bedazzlements would construct

and operate a monastery along that precipice always

seems quite clever to Corbett, the good work of shrewd

religious geniuses.

Enjoying the sensation of the granite pillar warming the

pads of his bare feet, he laments the likelihood of never

experiencing the Tiger’s Lair for himself, or for that

matter, the magic square on the doorway of the temple at

Khajuraho.

5

What Jim Corbett has known since he was fourteen is that

his feet are tougher than any wild elephant’s four – and

enormously more useful. But he’d not devoted himself to

attentively maintaining them until the fall of 1889, when

his mentor, the great outlaw hunter and woods-wise

philosopher, Kunwar Singh, had first eulogized the

seminal importance of keeping them clean and airy.

Number one for Kunwar: the repeated use of stockings

and shoes was possibly mankind’s greatest mistake. The

boundless tracker was genuinely distrustful of shoes and

terrified of socks. Herders, loggers, mahommedan

cartmen – wastrels and paupers – whoever should wander

upon the friendly campfires of Kunwar’s bivouacs in the

forbidding jungle nightscape – all learned that socks were

another word for septicemia.

Unmoved by rivulets of molten fat tracing below the front

of his threadbare shirt, Kunwar preferred to lecture on

podiatry while chewing sizzling meats plucked straight

from greenwood spits. Feet were discussed by Kunwar at

every meal. The most impassioned of these sermons

always ended by establishing footwear as part of an evil

conspiracy to neutralize man’s natural advantages as a

stalking hunter.

Before Kunwar lost the gleaming edge of his animal

instincts to a surprising opium addiction, coupled with the

foregone infirmaries of too much exposure, he had been

the preeminent pendant of wildland hunting lore above

the primitive farming community of Mussooree – up

where the sacred Ganges River comes coalesced from the

permanent ice fields and the vertical redoubts that defend

the undisputed end of the world.

In those days at these locations the teenaged Corbett was

his prodigy, a keen and generous listener with the leonine

feet and the superb ankles of a world-class mountain

runner, appendages that now in the receding winter of

1939 remain one of the greatest sources of his pride.

Magnificent accomplishments of skin and bone that once

again have Colonel

Edward James “Jim” Corbett at a well-defended position

6

reserved for immortal boys smashed on the mythical elixir

amrita.

He drifts back from his recollections of Himavat and

Kunwar to behold more scenery from atop the granite

upheaval at the center of the great Indian River

Rāmgangā: a pellucidity of gritty roils compelled by the

collaboration of extreme forces – monsoons, typhoons,

shrieking whiteouts and high-altitude glaciers.

In his fingers balances the stiffest 10-foot salmon rod so

far produced by the famous House of Hardy, England.

The threaded bamboo switch is paired with a Palakona

Perfect large-arbor reel spiraled with a fly line made of

Indian linen, Asian silks and Scottish horsehair. It is the

treated line that represents the most important technical

frontier of deep-water fly fishing, allowing new-and-

improved access to the perpetual half-light sovereignties

where loveless eremites eat their young.

Cinched at the point of the tippet is the finest example of

fish hooks wrought by the renowned E. Von Hoff. It is a

steel 1/0 decorated with the gay plumages from nearly

one dozen different birds – jungle cock, Indian crow,

golden pheasant, kingfisher, European jay, blue chatter,

rifle bird, mallard and Kashmiri pintail and silver teal.

The fly is the work of art of a British craftsman who treats

his primary fetish with all-night binges at his tier’s bench

in an ambiguous studio brownstone squeezed among the

more powerful industries and financial institutions of

London.

The pre-paid purchase order metered in Bombay, India

had informed the elite fly dresser that the dozen

streamers, together with a new Hardy angling set, would

be presentations from the employees of the Mokameh

Ghat in Bengal to Jim Corbett on the occasion of his

retirement. The letter went on to say that all of these

special things were soon used by Corbett on the

impressive golden mahseer, the most powerful freshwater

fish in the world.

With this as close as the epicurean fly dresser would come

to the greatest of hunters, or to the cel-

ebrated carp known both as the Salmon of India and the

7

river tiger, the armchair entomologist whip finished the

flies obsequiously to the height of his dexterities. At no

charge, he’d added a “lucky thirteenth” to the ticket

together with the blessing of his most orthodox client, a

snow-capped Westminster cleric and dry-fly purest from

Victoria Street.

Multiple worlds away from the natural light drawn off by

the soot-streaked panes of the fly dresser’s bedroom

office the crystalline River Rāmgangā brightly slices her

pristine and perfumed canyon like some gigantic

automaton of liquid light, like the divine onslaught of an

eternal water saw programmed to sculpt a Hindu khillut, a

gift, by the immemorial attendant of persistency.

She is a god, this river, and all across her brow radiates

the nova of bougainvilleau, catkins, maidenhair ferns,

golden dewdrops and amaltas, wild almonds, lilies,

joanesia, aquamarine strobilanthes – and minor

subspecies and one-of-a-kind hybrids as yet unlabeled by

science. He estimates the fresh smell of it all when

blended with the new breath of the river as quite beyond

propitious. And all men who agree that the sub-tropical

highland to be the rarest environment on earth would

conclude with Corbett that the far-flung Rāmgangā

complex is the exclamation point.

Corbett determines that the word fantastical may best

represent this halcyon day in the river canyon to readers

of the first book he is soon to finish. It will be that much

more accessible than metaphorical references to Palatine

Hill or the Pantheon, none of which are his style.

Rāmgangā canyon is presently the whole scope of

magnificence, he reasons; a hinterland cathedral unscored

by discovery. So before he turns completely to the

business of catching the biggest fish in her he loses

himself for a few more moments in admiration of the

gilded mosaic of this numinous creation: the dancing

scrolls of light in her graphite-colored waters, the

amethyst bellies of stacking clouds fluffing noiselessly

beneath the high, cool sun.

He fills himself with the novel of her energy and her

grandeur before turning to locate Mrs. Jean Ibbotson

waist-

8

deep in the Rāmgangā. She is several hundred yards in the

river below, the gold spoon at the point of her fishing line

twinkling in the space above the excited drain of a glass-

slick pool.

Beyond her the increasing mirage conspires with distance

to partially cloak Corbett’s view of the encampment that

he is fishing from with Thomas and Jeanie Ibbotson. He

searches the river unsuccessfully up and downstream

from camp for Thomas before refining his search for him

at their lodgings, the oblique of the canvas awning

wavering in the sprouting heat way past the middle

distance and Jean; an outpost opened by a prickly

labyrinth of risky game trails for its final nine miles from

the increasing rusts of civilization; a forgotten X on

incomplete charts since the fifth century; the blazing

sandbar now separated from the time when a doomed

contingent of infantry-protected mahouts of the Pala

Empire watered a column of war elephants driven mad

from thirst.

Utopia, Corbett says to himself, while wondering why

Thomas is not fishing. He has the notion that Thomas

may be regrouping at camp, perhaps after breaking his rod

on a mahseer. Or maybe Ibbs is carefully out of Jean’s

sight stoking his pipe in the lee of one of boulders above

the treacherous plunge pool they’ve named The Keeper?

Corbett completes a second and more thorough search for

Thomas, again noting Jean, before disengaging from the

Ibbotsons and the idyllic conditions to focus on the meat-

and-knives tactic of sight fishing. Still-hunting fish would

be a more accurate description of the exercise: peeking

discretely over the brink of the rock but only in the

diffused light beneath the shifting clouds; sneaking on

slow and low to the cover of the boulder’s edge to new

positions where he may see fish before they become wise

to him.

He is not surprised to find himself underestimating the

advance of time by more than half. The centrality of time

is lost in fishing and this is fishing at its greatest intensity

– almost two hours pass with only a few small fish

sinking into the depths beneath his fly. Many blind casts

are weightlessly stripped

back through deep holes. The subsequent beating he

receives from the undulating glare and the physical strain

of staring

9

through the refracted depths has gone well beyond tedium

before he confirms the first forked caudle fins of big fish,

a smoky trident of mahseers suspending just above the

murkiest depths of the riverbed.

Their size sends involuntarily jitters through the upper

half of his body, besetting him with the cold flesh of a

plucked goose, reviving him with a heart shot of

adrenaline.

Displaying the patience and the discreet fluidity of owls

he observes them for a long, long while. That they can

suspend in that current with so little of their geometric

bodies in motion is recognized and prized as a

pronounced secret within the greater mystery. When the

largest of them rolls slightly, flaring the

great rubbery lips of its inferior mouth, slightly cracking

the armor plates of its massive gills, feeding, Corbett

finally exhales to a cycle of deep, rhythmic breathing

aimed at shaking him from the rushing fear of failure. He

thinks that he can smell them in the next breath he takes.

He begins pretending that they are small fish, fooling

himself with the idea that he isn’t there for the catching of

fish but for the fishing – the grand adventure of it with

best friends, the fullness of a final few campfires in this

ancient coliseum where the prehistoric grandsires of these

fish existed before the invention of hammerstones. When

these deceits no longer satiate him, crawling there across

the marble pedestal to a better position above the river’s

apex predators, he diverts to how fine it is to own the like-

new Willesden tropical gun case from Lyon & Lyon,

replacing the worn-out original that had been parcel to his

Express. He thinks of food with iced drinks and “birds”

and tennis and the upcoming presentation of his fly...

eventually dismissing these mental rues as weak-minded

dilutions to what should be the complete joy of angling.

What comes next to thought is the spider killing the fly.

Of how the precision bomb of poison, silk and physicality

had infiltrated the mayhem of the flies to leave them one

less.

What about the dynamics of that spider’s game-hauling

return to the unspeakable terms of its nest?! Bloody well

amazing, he thinks.

Tom, his much older brother, gone himself now for

10

years and years, had prized the spider epic, which had

been

spun from the ruins of the reception of their father’s

memorial. The sad tributes for a beloved postman, taken

too young everyone said, drifting dolefully in the

westering sun, infusing all those recollections of Corbett’s

boyhood in India with the evening pall of great loss and

lives forever altered.

Before she abruptly disappeared for a fortnight to grieve

alone his mother had considered her youngest son’s

version of the spider-and-the-fly to be nothing less than a

heavenly idiom sent specifically from his father.

He is now much older than his mother was when she

buried her husband; silhouetted on the rock above the fish

like a sprinter set to starting blocks, the hook pinched in

his fingers just beyond the polished rings of the reel seat.

What there is of free line not held by his left hand lies in

coils atop his forward foot, and the sun comes blazingly

from behind the scudding clouds like it never will again to

ignite the ghostly bronze and silver-skin reflections from

these three remarkably outsized mahseers.

The middle fish is a relic – five, maybe six-feet long, and

perhaps more than one-hundred pounds. The smaller

leviathans to either side are blasphemous minions by

comparison, bookend sixty pounders, the second and third

largest mahseers he’s ever seen in the wild.

Again and again in the prevailing water he swims a fly

blessed by a Catholic bishop inches over them until he is

convinced that the fish are blind apparitions. To sink it to

their level, to wisp it across their noses, he easies on

across the rock and lays the line out farther upstream.

Eventually, on his fifth attempt, he hisses “don’t” as the

point of the hook bounces lightly off the unblinking eye

of the closest fish, faintly stirring the creature. He strips in

several feet of line and water hauls while skulking a bit

farther upstream, shaking a beautiful aerial mend to the

line as his very next loop straightens above the race.

He does not allow himself to lose sight of the fly from the

time he sees it raindrop among the bubbled surface seam

of the Rāmgangā until it vanishes, he thinks, into the

closed mouth of the middle mahseer. The evanescence of

the fly, the reaction of the line bellying from the face of

the fish to his heart, is twin

to the fountainhead of self-realization ascending deep

meditation.

11

Corbett delivers a twisting strip-strike upstream, a

scissoring action with both line and rod and the rotation of

his hips that astonishes him with the fusion of a dead-

solid hook set.

Unmoved, the fish – a huge animal made almost entirely

of dense muscle and elastic bone – feigns mild surprise by

erecting every set of spine rays on its body, dramatically

doubling its mass. Its escorts delicately tap their pectorals

and plane away like swooping serpent eagles as Corbett

officially rouses the colossus with another snapping strip-

strike that threatens the connective tensions at every

terminus of his tackle.

This time the fish feels the nip of the hook all the way

into its cold guts: In chromium flashsight as though the

mighty Rāmgangā is ripped open then closed by the

wicked edge of a kukri, the mahseer bolts upstream,

positioning anxiously just above Corbett, who is

frantically piling slack line at his feet to hold some

amount of pressure. All in setup to the instantaneously

forthcoming actions exclusive to big-game fly fishing,

reptilian fascinations quite unknown to more casual

anglers:

The fish torpedoes upstream with the velocity, the

mindless determination, of a shoulder-fired harpoon!

My God, he says to himself. My God, he shouts.

This first run is an event visually calculated in the

byproducts of power: the bulging shockwave pushing

across the river’s surface and the insane reaction of the

twenty-five feet of loosely coiled line that dances up

around Corbett like a severed bundle of electrified wires.

The size and the blinding speed of the fish; the writhing

spectacle of shooting line sucking out through the guides;

the stored energy multiplied in the overloaded rod; and

the whine of the reel are incomprehensible split-second

dimensions of a warped new reality.

Together with the facts that his left palm and thumb are

quite actually burned raw and streaming blood, that he has

run out to the end of the island rock – worse, he notes, the

juggernaut will soon expose the backing’s arbor knot at

the spool. His option is tightening down to something

beyond dangerous pressures and with that the river tiger

crashes distantly into the air, a spinning girder of golden

shrapnel that’s been

12

blown right out of river’s bedrock!

The searing jump is ruthless, defining... and the behemoth

descends beneath the foamy keloid on the otherwise

tranquil water like a depth charge and explodes, thrashing

its head as awfully as it had first lashed its tail; the rod

bucking spectacularly down into the cork handle; the

split-cane bow and the inexorable gauge of the Rāmgangā

bringing the berserko back downstream.

Excellent lengths of line are recaptured to the reel in

anticipation of what surprises Corbett as the plebian tactic

of much younger and weaker fish: the slicing, sawing line

twice crossing to the canyon’s vertical wall and fully back

to starboard, the fish quixotically fighting the river and

the rod before flatly recognizing the fatal flaw in that.

And the next running aerial by the furious golden weapon,

now not thirty yards off the promontory, is a detonation

that introduces the idea that this engagement is the

mistake of an indifferent universe. The fish hangs dancing

in a sun-drenched hydrostatic halo and the explosive

smack as it reenters the river is felt in Corbett’s

back teeth. He gasps as the Expected One’s real violence

comes jolted loose by the blow, bearing witness to the

release of some primordial aptitude for motion that

outstrips by treble the swiftness of the great river’s

mightiest flood.

One-hundred yards in eight seconds – river aided – he

will proclaim that night during drinks at fireside, or

farther in seven seconds, before he stops running, trotting

and walking apprehensively behind the fish to find it

sulking and despising him from behind a submerged

boulder beyond a narrowed torrent.

The mahseer can feel him, then possibly see him in

opaque profile, and that brings the beast of the Rāmgangā

on up to devastate, to greyhound athwart the surface, to

beat everything at once that had ever been set against it –

the heaviest cross-currents and the crackling long rod

ready-set to pop.

True champions finish with combinations. This fish

sounds among the bobbing arms of a floating tree, a

preacher

trapped upright in a large whirlpool, and follows with

another breathtaking leap. And the line bighting the

petrified

13

wood must have somehow abetted in somersaulting the

freed immensity, because until that instant a complete

backflip had never seemed possible.

The imperial predator looks the fisherman dead in the eye

as Corbett falls back against these things with the rod

straightened and empty in his hands. Desperately he

moves to snatch some final sign of the fish in the empty

river. But there is nothing except the prototype line

skittering atop neutral snowmelt the color of iron.

He swings up the tattered droplet of feathers and grabs it,

surprised to find that the Von Hoff has been straightened.

This hard fact brings some solace. Excruciating defeat is

always tempered in instances of extreme tackle failure.

He finds that catching his breath is easier than mahseers,

stroking the clean palm of his non-bleeding hand across

his moustache. Out over the sound of crushing water he

speaks evenly to the fugitive:

You are a miserable dynamo, he says. A conceivably

unbreakable World Record.

Did you not know I would only hold you in the light?

Rest and admire you and let you go? Yes, of course. But

you’ve survived to become selfish and vain. Lice

wiggling around in your horrible gills that are older than

me. Surrounded by bug-eyed sycophants; turtles soon

eating your fins to pieces and you too demented to notice,

or care.

He sighs and studies the place where several layers of

skin were barked off by the stubby handle of the reversing

reel. He bites the hook from the line, moving the frayed

artificial to his trouser pocket. He turns all of the line up

through the guides, whispering the recitation of the old

fisherman’s adage to the only person present, plus a father

he can dimly remember and his dead brother, Tom:

The big ones always get away.

The vague one-note acoustic of Jean’s soft voice soon

draws his attention downstream. She has a fish, he thinks,

five-hundred yards in the river below. Quickly he wades

into the frothy water, flushing away in the tailfan of the

rock podium, working his supreme steerage to the

direction of Mrs. Ibbotson.

14

Have you the fish or does the fish have you?!

The judges have the fish ahead, I think, Jean hollers. Will

you please – Oh, my!

The six-foot bamboo casting stick long strokes

frighteningly in a series of vicious concussions with the

weight and the speed to break an arm, forcing Jean to step

unsteadily into deeper current towards the fish.

Hurry along, Jim, and help me land him?!

Corbett comes prancing to his feet across the head of the

holding water. He circles along the sandbar and wades

quickly up behind her to offer his critical assessments.

The fish is pummeling Jean. He asks: How do you know

it is not a she fish?

Because he has balls! They were pendulous when he tail-

walked out of the pool!

Well, Jeanette Ibbotson, he laughs. How deliciously

profane! I suppose big fish will completely change a

person!

No, Jim, they expose the things that were there all along.

They lay it – Oh, no!

Jean stumbles, bowing towards the boring fish to keep the

banging crescent from snapping off just above the level-

wind reel, she thinks, and her left hand comes away from

the rod. Corbett fishes her up wet from the head down. He

holds her by the shoulders until she’s reset her feet on the

slick bottom, the line now carving fast to the surface.

Don’t horse him, Jean! You’re horsing him!

Does it really appear that I’m horsing him?! Are we

talking about the same thing, Jim?! He’s killing me!

Keep the rod low with pressure when he...

Wrapped in crystal jetsam, the fish explodes big and crazy

like a random solar flare, slamming its way back into the

river.

Did you see them, Jim?!

I could not see them because his giant flaccid prick was in

the way!

Do not lose him, Jean! You’ll regret losing him for the

rest of your life!

Now Jean cannot stop laughing. Had the fish broken

15

the line or beat the brakes off the drag and spooled the

reel or thrown the spoon or had Corbett botched the

landing, there was no misery that the fish might provide

that she would not have laughed away.

But the fish eventually loses heart and Jean is soon

coaxing the temporarily subdued animal to the warmer

shallows below her, where Corbett seizes it with two

hands firmly above its tail. He wrestles it briefly before

dragging the thirty-five-pound golden mahseer

triumphantly to Jean kneeling with her eyes and mouth

competing in awe.

They sit in the Rāmgangā with the exhausted, missile-

shaped fish between them.

I suppose the camera is in camp? Corbett asks.

Yes, on the table at camp. I left it purposely, you know, to

improve the odds of catching a fish like this.

That’s the play, of course. Well, he says, let’s hold your

rod against him for a mark. We’ll know how much we

must lie when people ask for a weight. Some fishermen,

not many, will be happy that you caught such a fish and

they will give us permission to exaggerate his size.

Jean raises herself and Corbett lifts the fish to fix its

length and depth against the impromptu ruler. The

magnificent diamond patterns of the mahseer, largest and

most vivid right atop the lateral lines, are rapidly fading

and minnow fry, appearing as see-through clouds of

flagellum, gather to peck at the fish’s slime. Jean reclines

to a sitting position as Corbett re-immerses the

resuscitating animal. He holds the dorsal spine ray aloft

and whistles at the splendor and the size of it before

shifting to study the fish’s pupil.

Aren’t his barbels fun?! Look at them, Jean – like fleshy

moustaches. And just have a look at these scales! There’s

nothing to match. I would say he’s forty-five inches long

and close enough to forty pounds. What a corkingly

bloody, completely outrageous, monster! Quite

astonishing, Jean! Damn fine show and congratulations!

She moves up to her knees and runs her hand lightly

along the platinum effervescences of the mahseer’s skull,

16

turning her head to get right in the fish’s face, winking at

it.

Let’s let him go right here and see how long it takes.

With that the fish swims lethargically out of Corbett’s

hands, out just past them before laying a righteous,

twelve-foot gouge through the shallows on its way to

ultimately reclaim its feeding lane. The fish’s escape re-

soaks the onlookers. As they swipe the water from their

faces Jean notices Corbett’s bleeding thumb.

Propitious, he cheers.

What is that?!

Oh, dear. It’s nothing, really. A flesh wound. My reel

became quite angry and bit me.

Jean takes Corbett’s non-bleeding hand and they come out

of the water with their arms amiably, comfortably locked

in support.

I crave a cigarette. Any chance?

I thought you were quitting, Jim? I should not encourage

your vices.

Had I quit I would start again just to have one now. The

respites of fishing lend themselves to the pleasures of

smoking leisurely. I am not one to give up on their

enjoyments, their need to control me, while conditions are

so favorable. I am smoking heavily in anticipation of soon

giving them up forever.

When?

This could be my very last cigarette, Jean, or probably

not. Better, perhaps, I will continue to enjoy their

completely foul company through our final campfire here.

You know, smoke the last one down to my fingertips,

flicking it into the driftwood coals.

You know, done.

They have just finished second ones before returning the

hail of Thomas “Ibby” Ibbotson, the Provincial

Commissioner of the Kumaon District, who is enjoying

the genteel life abroad from the utilitarian comfort of one

of his three Goojerat chairs, cooling in the speckled shade

beneath a square of canvas sail lashed among a copes of

grandiose centennial oaks. Ibby reduces the volume of his

wind-up RCA gramophone and the sound of Benny

Goodman’s exotic clarinet in Get Happy is

17

exchanged for the more natural reverberations of the

canyon land. He shouts:

Well?!

They work out of the sandbar to the fieldstone center of

the camp before replying.

Oh, it was just cracking, darling! Truly it was. But I must

have water and a change from these terrible fishing

clothes before I begin honing my version of the

experience. It took only about ten minutes to catch the

fish, but it will require an hour to establish the first verbal

draft of the story.

Ibby is quick to finish pouring them initial refreshments,

hanging a towel around Jean’s shoulders and kissing her

on the cheek.

Wonderful, darling! Wonderful! Congratulations! Was it

a good one?!

Oh my, yes! The best ever!

Well, I can’t wait to hear all about it. The shower can is

brimming. Why not hop in and out and join us back here

for an early one? I’ve such bad news about the abrupt

ending to our holiday here.

Oh, Thomas!

It can’t be helped, I’m afraid. But you run on to the bath

and I’ll wait on you so we might discuss it all just once.

Then we’ll be done with that. We mustn’t let it spoil our

last night here. Meantime, Jim can regale me with one of

his fishing stories, which are always dramatic and full of

mendacities and half-truths. I’ll have you a proper drink at

the ready.

He continues:

Madho and the staff are preparing an early dinner, so that

we might fish in the evening cool before relaxing with

desserts around the campfire. In keeping with our early

departure, I’ve pushed the menu forward. We’re having

grilled mahseer, roast lamb, green salads, Madho’s

famous Dutch-oven bread and the most titillating

Bordeaux. Tonight we feast.

May we use up all of the butter on the Dutch-oven bread?

Why yes, dear, of course. Madho’s bread is merely a

vehicle for the last of the butter.

18

Ibby snatches a second kiss as Jean makes for the canvas

water closet.

Your dressing gown is on the nail. Darling, you must

remember to shake it out before you put it on.

Jean gives her husband “the look.” Ibby smiles at her and

moves to find Corbett missing from the caprock patio. He

calls to Corbett’s partitioned section of their sleeping

quarters.

What’ll it be, Sahib, the usual?

Please double it, Ibbs. I was booked here through

Tuesday, you know, pre-paid for an all-inclusive. I’m just

informed by management that the band has been

cancelled and that they are packing up the bar. Make-

goods are impossible. So, chum, it sounds to me like we’d

better start drinking, if we were going to drink.

Yes, well, you may stay and fish. I’ll send Madho and a

crew back in a few weeks to pull the camp after you’ve –

maybe – caught one fish on your fly rod. Jean may also

want to stay. I feel just terrible about leaving early, but

I’m afraid something quite serious has come up.

I did catch a fish with it today, Ibbs.

Ibby notes a strange shape several hundred yards in the

rocks way up on the canyon wall opposing camp. He

moves back to his chair, takes the powerful German

binocular from the table and begins trying to find and

identify the object, now temporarily distracted from

Corbett’s fishing report.

I say, Ibbs, I did catch a fish with it.

There are distinctions, Jim, between moving fish and

landing fish. I would already know if you’d actually

caught a fish with your new fly tackle, because you would

not have gone inside the tent without some bravado. You

would not be inside the tent. You would be shout-boasting

from atop the tent.

See here, Ibbs, that’s where you are very wrong, again.

Those terms are interchangeable to the fly rodder, the

sportsman. When fishing with flies, once the tippet comes

into the top guide the fish is considered caught. Angling

has its own higher set of rubrics, its own canon, beginning

with the very first of its grand distinctions, the word itself:

angling. The use of level-wind reels is not angling. The

word angling was

19

created specifically for fly-fishing by the American

philosopher and poet, H.D. Thoreau. Fishmongers using

level-wind reels, spears, gill nets and weirs have no

Thoreau and they probably never will.

Ibby’s eyes are intermittently in and over the binocular,

struggling to find the general location of the unidentified

object on the distant mountainside. Ibby whistles and says

evenly:

In record time, man, haven’t you become just the most

affected of all the fly-fishing pettifogs.

Noting Ibby’s scrutiny with the bino, Corbett comes on

barefooted from the tent and takes a seat next to Ibby,

who stands the optic on the campaign table. He downs his

ice water and swaps the position of it with the gin and

tonic Ibby has readied for him. They are quietly reloading

for more banter as Jean returns along the stone walk to the

native patio. Ibby settles her in and the men reclaim their

seats. Ibby hoists his glass and Jean and Corbett follow

his lead.

To safe travels, bold adventure and all the people we love.

They nod and drink, returning their glasses to the linen

tabletop. The rustling breeze of the banner day comes

down canyon mingling with the subtleties of the polishing

of cutlery from the cook tent.

Okay, everyone, here’s the brief:

Pierre La Fayette, Pete – the PH you’ve both met on

numerous occasions – and his pair of French-national

clients, missed check-out a few days ago. Jack Evans was

conveniently up that way at one of our stations and the

office diverted him to Pete’s camp. What he found is a

bloody mystery. We know this because J.E. dispatched a

dak runner from Nahan, who was relayed by a second

runner, arriving camp after you’d both left this morning

for fishing.

According to J.E., the client’s bedroom has been used as

slaughterhouse. There were eleven souls in Pete’s camp.

Presently, no one has been accounted for. So, I’m meeting

Jack and a few of our boys from Naini up there at noon

tomorrow.

Pierre La Fayette: scoundrel: Le Gharial, says Corbett.

And how will you, Ibbs, ever find your way from here to

there

20

by noon tomorrow? You’ll be riding unfamiliar country

for hours in the dark. I’m sure you could not find your

way to the Garuppu Road in two days.

I was hoping you’d accompany.

Without expression, Corbett takes up the binocular from

the table. The blood has drained from Jean’s rosy

complexion. Ibby is smiling nervously and fidgeting with

his wedding ring and his wristwatch.

What?! Pete would come looking for you.

No, he would not. He would get arse-slapping drunk.

He’d tell everyone within ear-shot in his slurred, silky

French accent that he’d been out looking for me on his

own. But you know as well as I that Pete, I’m sorry, The

French Crocodile, hunts only tigers, wealthy clients and

women. He doesn’t hunt lost campers. That won’t work,

Ibbs. Try something else.

I thought you liked Pete?!

Who doesn’t like Pete? That’s not the point, Ibby. Even

the cuckolds and the cheated boyfriends like Pete.

Corbett readjusts away from Ibby and begins casually

applying the binocular to the river cliffs that earlier had

interested his best friend.

Jim, you simply must go, Jean injects. There are others

involved besides La Fayette. If you would please do this

with Thomas, I’ll repair to Kaladungi and help Maggie

with the packing. I’ll take some of our help with me.

Corbett looks at Jean and Ibby, then back to Jean,

who is clearly distraught. He sighs melodramatically and

slumps back in the Goojerat. He again brings the

binocular to the piece of Shangri-La that Ibby had been

scrutinizing; resetting the balance of focus to his eyes,

wheeling the diopter until the image crystalizes. He holds

the instrument stock still, using only his eyes to search

among the wonderfully vivid field of view.

Very quickly, very luckily, he catches a flicker of

movement in his lower periphery and slightly re-centers

the tubes. It is the right ear of a young sambar bull in the

shadow of an over-achieving tree – a bodhi growing right

out of what appears to be pure rock, the bedded sambar

beneath it.

He returns the field glasses to the table, casting back and

forth at the Ibbotsons before sticking on Ibby.

21

So, Ibbs, tell us: Were you asked to name the very finest

fly fisherman in India, possibly the world, whose name

would you give?

Ibby casts back and forth at Corbett and Jean, the tension

lifted from his expression.

Well, before I divulge my surprising answer to that there

is something you both must hear.

A smiling Ibby siphons his gin and tonic and is quickly

away from the Goojerat – a purloined design first

discovered by the British military in an overrun French

outpost on the Indian frontier – to his gramophone, which

he charges with the hand crank. He replaces the vinyl disc

resplendent in the Big-Band sound of Goodman with

another record, maximizes the volume and, as the needle

cues, he addresses his campmates:

It’s not the Skillet Lickers. It’s much, much bigger than

that. The recording originated ten thousand miles away

from here in a place called Oklahoma City, delivered to

me the day before we left Naini. These boys are the new

stars of the category.

And with that introduction, “I’m a Ding Dong Daddy

from Dumas” performed by Bob Wills and the Texas

Playboys comes up to fill the quiet canyon.

Ibby lets the song soar past its signature hook before

twirling Jean up from her Goojerat, announcing

euphorically over the music:

The sophistication of great jazz piano mixed with steel

guitar, unbelievable fiddlin’. It just pops, doesn’t it!?

Sugar moon!

The Ibbotsons are immediately gyrating like instructors of

western swing across the crown of the sunken boulder.

The small, beaming wait staff hurries around the canvas

salon from the cook tent to watch. Corbett is soon moved

from clapping his hand on his bouncing leg to a bit of jig

dancing. Ibby spins Jean into Corbett’s arms, yahooing,

and, in turn, Corbett and Jean set forth riotously

‘round the edge of the marbled dance floor. Ibby hollers

at them over this completely new level of rhythm and

rhyme:

What about it big-cat daddies?! How about that!

22

23

22

Le Chasse, Unlimited

They had saddled wet horses in a steady rain and two

hours later all that they are is soaked through with dirty

runoff and everything else is muddy and slick. Below

them in the washed-out distance the recently sparkling

River Rāmgangā has become a brindled ditch. The storm

presents all of its overbearing incantations and nothing of

those previously delicious days in Camp Mahseer,

perfections alive with bright birdsong and tasting of

sunshine, can be easily remembered.

Corbett and his steaming horse have almost led them out

of the flooding canyon when the high, winsome trail quits

against a barricade of vertical rock. He twists in the saddle

and waits for Ibby and the mare to come pulling into his

eyereach through the pelting rain. His voice is strident, so

as to be heard over both the distance and the inundation:

Hold what you have, Ibbs. This game trail just quits on

these boulders.

Corbett situates the reins, tentatively dismounting uphill.

He crouches athletically on the treacherous upslope above

the horse and begins the slippery work of turning the

animal up and around on the ribbon of trail. He does this

by crabbing backwards, one hand on the greasy hillside,

one hand tight to the reins. The horse can only be

convinced to go at it with a tap to its rump and the wall-

eyed creature scrambles and comes on through the

terrifying reverse turn with free reins, loping sixty yards

to stop where Ibby stands his mount.

23

Corbett slops to them in the downpour, pressing between

the mountain and his quivering animal to take-up the limp

headstall.

Well, Jimmy, that was quite the display of horsemanship.

For a confirmed hiker and general loather of horseflesh,

bloody well done!

You are least funny when you are masquerading as a

floating rat. Consider the possibilities of losing hold of

your horse in this. Do something right for a change,

Governor.

As Ibby turns his horse, the edge of the trail sloughs

cruelly with the speed of a trapdoor from beneath the

animal, taking the splayed steed backwards downslope

with Ibby sledding along in tow. That could be it for the

horse and, maybe, Ibby, Corbett observes.

Let go, Thomas! Spread out!

At the very edge of a seasonal waterfall the horse

unpredictably rises and wildly, briefly, runs in place to

recapture the vertical ground. Ibby skids right in there at

the horse’s legs, grabbing among the mare’s chopping

blows to catch a wet stirrup, which by the grace of God he

holds. He regains his feet, wraps his hand in the horse’s

tail and struggles mightily to keep pace as the lunging

beast climbs back to the trail. They are soon arranging

themselves below Corbett and his horse.

What were you thinking of?!

Stopping, of course.

They leave the canyon through a widening nullah

defended by an orderly forest of plantation pines that goes

up into the unbroken for two miles; altogether pleasant

riding within a new country if not for the solid rain. They

cross through a tall-grass meadow on a plateau in

slackening rain where a large, loose, post-rut collection of

spotted chital deer believe the riders to be peaceful

centaurs before striking a path winding among a

deciduous belt; ghosting ever upwards and into a cold fog

and the hardest deluge yet: rain that makes them laugh

and shake their heads and say that they are underwater.

Corbett calculates they’ve come nine miles, maybe more,

with twice that to go. And by the time they’ve cut off the

next third they are in freezing rain on an escarpment that

intermit-

24

tently exposes the eight-thousand-foot crown of Cheena,

twenty miles east of their right shoulders. They ride on

single file into a land experiencing a warmer snowfall,

passing among the grounds of an ancient temple jumbled

by earthquakes and all but erased by stone robbers;

skirting the worm-wood foundation and rusted capstans of

a burning Ghat perched above the abyss of a vertigo-

inducing gorge; and then through a mile-long canebrake

where, deep within, they stand the horses so that a

lethargic king cobra might abandon the trail with dignity.

What is it?

Hamadryad... stretched atop a fallen limb all the way

across our front. I don’t remember ever seeing one in the

snow.

Big one?

Unusually.

I wish I could get around your fat horse’s arse to see it

myself, Jim – in the snow.

Lower your voice, Thomas. It may be eighteen-feet long.

Slightly louder, using the most ornately polished tone

within his classical repertoire, Ibby replies:

In this context, old boy, I propose that any snow cobras

we may encounter are possibly only Homeric allegories of

your imagination, foreboding elements...

No, Thomas. It’s not.

Corbett carefully tightens the reins, upping the pressure of

the bit in the horse’s lips. The mare steps backwards,

crowding its rump into the face of Ibby’s horse, as

Corbett withdraws the American-made semiauto from the

shoulder holster beneath his coat. He pulls the reins across

the horse’s neck, slightly quartering the animal in the

unyielding trail, craning over his shoulder to find Ibby

smiling very merrily.

Fuck on with that Latin-style dialogue, old chap. This is a

bloody serious goddamn snake.

The horse pops the reins loose from Corbett’s grasp to

better watch the snake, now coiling dangerously along the

top of the wood – Corbett feels the animal catch hold of

its breath and quiver. To the surprised horse this king

cobra registers as having the dimensions of a telegraph

pole.

And that quick the open-mouthed serpent is whipping

25

into the men and their horses with its head three-feet

above a goat trail that spontaneously appears to be

fissuring.

Corbett notes the heavy strike as likely killing one

of them.

From his back in the dirty snow, he is aware that the

snake remains fastened to the spin-bucking horse. The

unbuttoned animal, jackknifing in and out of the cane, is

so powerful and wild that he never again sees the snake.

In fact, the raving horse seems quite capable of having

eaten the monster; finally crashing onto its back from

height, its subtly vibrating legs locked straight up for a

long moment in the excited calm.

The frothing horse then convulses electrically and rolls

slowly upon its side – greatly inhaling and exhaling just

once before galloping a dying circle in the sludge.

Golly, says Ibby flatly from down the desolate trace.

Corbett begins the search for his pistol in the area where

he’d been thrown. They hunt carefully all around, back

and forth on the greasy trail, well up into both walls of

cane, before eventually arranging themselves, without

having located the gun, at the dead mare.

Maybe it’s under Jean’s horse?

Corbett steps in and hunkers at the animal,

sympathetically patting it, resting his hand on its warm

rump. He is about to speak to Ibby, or maybe the horse,

when the splendid charger rolls up wondrously to stand

blinking at each of the apoplectic riders.

I thought she was stone dead, says Ibby. I’d been

wondering how you were going to break the news to Jean.

There’s the pistol.

Moving very softly, Corbett swipes away a level cupful of

poisonous yellow goo from between the bottom edge of

the saddle pad and the horse’s quivering shoulder. Then

he moves forward to soothingly stroke his hand along the

jaw line of the beautiful mare; finding and hesitating in

her fantastic eyes, whispering:

Welcome back.

He takes the gun from Ibby and moves a few paces

through the sucking mire to clean and disarm it safely

behind

26

and away from the revenant steed. He drops the magazine

into a coat pocket, picks the gritty gum away from the

striker, lightly lowers the hammer and spins the round

from the chamber into the cupped fingers of the same

hand that worked the slide. He admires the gleam of the

dry bullet, letting it sift in with the magazine and says:

My grandmother always told me that bad luck comes in

threes.

Still sliding about in the gullet of the smothering cane, the

wet snow reverting to its more standard currency, they

strike the Garuppu Road, a trail not much wider than what

they’d been fighting.

The slushy mud is cut in with human tracks and the spoor

of many kinds and sizes of deer, plus one outsized male

leopard and a female tiger and her twin 200-pound cubs.

They shadow these fellow travelers northeast for a full

hour until the marks of the wild animals melt into the

jungle at either side of the road.

The weary men arrive just before noon at the isolated patti

of Nahan, where from the saddle they expeditiously take

up hot teas that have been graciously provided by the

disfigured Tahsildar and his fetching young wife.

The one-eyed Tahsildar has no information concerning

the happenings at Camp La Fayette. He does, however,

know exactly where the Frenchman’s compound is

located and he impresses himself greatly in explaining the

route to Corbett

and Ibby with his mix of broken English and dramatic

hand gesturing. Not counting them, he has recently

directed a total of four English soldiers astride exceptional

horses to those tents during the past three days, he says.

He further explains that his brother’s youngest son had

been the daring and swift carrier who had delivered the

first and longest leg of the recent dispatch concerning

these matters to the vacationing Commissioner Ibbotson

thereon the River Rāmgangā.

The men nod and thank him and hand the empty cups

back down to the Tahsildar’s wife, who retreats quickly

from the downpour to her husband’s side beneath the

overhang of the tiled veranda. He accepts their thanks and

27

thanks them, in turn, and invites the riders back under

more optimistic conditions.

The next two hours are the most tortuous of all, enough of

the sort of aching, misery-induced subterfuge to enliven

even the ghastly trappings of Pierre La Fayette’s joyless,

water-damaged camp. Two men quick-step from the main

tent to the clutch of ginger trees and enter the fretwork of

wire-and-wood that serves as a kedad, inaudibly shooing

Ibby and Corbett away from the processes of unsaddling

their exhausted steeds.

The roofs of the outlying tents are low-slung catchments

of rainwater and each of the five primarily cloth structures

are individually fortified with blackthorn security fencing.

The site wafts of rendered bear fat and bacteria. Corbett

and Ibby shed their drenched outerwear beneath the

canvas-covered wooden landing of the main lodge.

It’s just warm enough to prevent freezing fog, says

Corbett.

Like Christmas Eve in Hell, Ibby declares.

Slightly harder light escapes from the angular space of the

unfurling tent door and Captain Jack Evans Coogan is

standing backlit in that rush of warmth with a pair of

robust robes spun from bleached Egyptian cotton.

Take it all off and wrap yourselves in these, gentlemen.

Dink drew short straw for laundry detail, so he’ll handle it

right where you drop it once he’s back up from the corral.

There is water, wine, an unopened bottle of Blood Hound,

clobber and sour, warm baths and dry bedding. We expect

the dancing girls to arrive in just a jiffy.

Coogan hands the robes to the nudes and backs into the

German-made, high-ceiling custom salon with the flap

held exaggeratingly wide.

Please, gentlemen, come in, enjoy the fire.

Thanks, Jack. I knew all along you would make a proper

soldier.

Ibby and Corbett have donned the iron-dried extra

clothing from their saddlebags, eaten and are sipping at

the popskull called Blood Hound before Ibby makes

mention of what might be known about this ghost-camp

assignment

28

they’ve ridden to Hell and back to attend, this missing-

person fantasy where they are preparing to spend the

night.

Jack Evans begins his official report:

I’m afraid, Commissioner, regrettably, there’s really not

much news. Dreadful, worsening weather, really, since I

arrived,

and so we’ve concentrated our efforts inside the tents.

Nevertheless, it was quick, I believe – we’ve established

that some of the servants came away from a table of food.

But at this point in the investigation, I’m only guessing

when I say that others stayed on here for a day or two

before the whole place was abandoned.

You see, gentlemen, a second smaller number of people,

likely La Fayette and his clients, seem to have left a capon

slow roasting in the oven by the look of things, possibly

the day after the staff vanished, continues Coogan. Maybe

around the time that someone seems to have been brutally

murdered on the bed in the client’s tent. We’ve taken a

forensics approach in there and I would stake my

reputation on the fact that someone’s throat was severed

before the body was dragged off into the jungle.

Interestingly, there was one footprint in the blood: a

woman’s bare foot, I’m sure.

Have you conducted any sort of serious search for that

victim and the woman?

No, Commissioner. Not yet. You know, with all the riding

in and out to contact the office, the weather, the work of

an active crime scene. No, I judged the victim’s wound to

be quite catastrophic and there is no sign of the woman, or

anyone, at this camp, so I’ve concentrated on other tasks.

I understand, Jack, but we’ve ten, eleven people bloody

missing nighon four goddamn days with enough idle

firepower standing in that gun rack to defeat a hoard of

mounted Turks. Is this some sort of goddamned

massacre?! How is it that so many people step off the

world together?!

Is there no gin and tonic in this camp? Corbett injects.

Yes. Right. How in God’s good name can perplexities be

solved, cases closed, without the clarity of the second

gin? What’s more, how can one conduct a proper shikari

without

29

that in the evenings, by the fires?

All these things – lost clients, a feral staff, not one last

drop of gin? I’ll tell you what boys: it’s just that degree of

slipshod that can get La Fayette’s PH license revoked.

I suppose it was the end of the season for Pierre La

Fayette, says Coogan. Maybe it was the end of

everything.

I did notice a bottle of gin in your saddlebags, sir, blurts

Corporal Timothy “Dink” Lewis.

Shahbash! Good old Madho. Now there’s a seasoned

valet, cries Ibby.

Corbett and Ibby snap-to, smiling broadly at one another

as Dink hurriedly begins procuring the product and a pair

of clean tumblers. In double time, he cracks watery ice

chunks in his hand with a serving spoon and dumps the

glistening contents into a small pan together with an ice

pick, setting all before the two senior investigators.

Speaking of guns, Captain Jack, I see the three rifles and

the shotguns there in the rack that Pete was known to

have in camp, plus one extra. Concerning this excursion,

is that all the arms your office has travel permits for?

That’s a great question, Colonel Corbett. The answer is

no. The primary rifle of client Monsieur Laurent Acelet

has not been discovered in camp. Yes, I’m quite sure we

are at least missing Acelet’s fieldpiece.

The grand dining hall and cigar room of La Fayette’s

luxury encampment balances atop a heavily timbered

mountain ridge resplendent in wild Bengal tigers and

leopards. It is a spacious tent elegantly appointed from the

campaign furniture

showrooms of Allahabad. There is a twenty-six-candle

chandelier above the cloth-covered banquet table to be

enjoyed from six well-cushioned Chippendale high backs.

The serving tables along the side walls hold a larger

number and wider array of candles than any Hindi lamp

shop in Calcutta, offering whatever amount of posh,

indirect lighting that might be preferred by the prosperous

customers of Pierre “Le Gharial” La Fayette.

The missing professional’s complete arsenal is racked in a

teak stand-up in one corner. The sterling silver table

setting is conspicuous. Nothing suggests theft or looting.

30

Nightfall has won again as Jack Evans provides the loose

discoveries from the bloody bedroom. He produces the

items on a towel to the main table, carefully arranging the

collection beneath the jetting glare of the gas lantern slung

from the chandelier. The men quickly gather over the

items, except for Corbett, who is taken aback by the sight

of the wavering antennae and the broad head of a very

large insect in the chandelier. The creature notes Corbett’s

attention, discreetly withdrawing from sight in the fixture.

There are rings, necklaces, bracelets of pure gold, silver

and platinum, an emerald brooch, a diamond-encrusted

Swiss wristwatch, diamond hatpins, a mother-of-pearl

hair comb sculpted in the form of a running leopard with

a ruby eye; .375 cartridges, a lightly funded woman’s

wallet, an empty coin purse made possibly from the

scrotum of a Cape buffalo bull, two French passports,

prescriptive medicines, a small-shouldered dark brown

bottle filled with processed coca and a crystal dildo,

which preoccupies the men.

A neat, thick stack of month-old magazines and

newspapers from London, New York and Paris sits at the

end of the table and Corbett picks out the Times, tearing

away the Front Page. He is handing it over to whichever

enlisted man is about to need it as Ibby says:

Jack Evans, Dink, one of you men, please, what say we

take the unusual device out of play here and store it in the

woman’s valise.

Careful, we may only speculate as to exactly where that’s

been. We might need you to dust it for prints, Corbett

says with a wink.

Dink wraps the erotic tool in the broadsheet and removes

it to the client’s baggage at the corner of the canvas

chamber. Corbett then rolls the rest of the front section of

the Times tight as billy club, pulls his chair to the edge of

the table and stands in its seat. Blocking the intense

lantern light with his left hand, he draws a fine bead with

his weapon and deftly, instinctively, smacks the insect

twenty feet into the side of the tent. He returns with the

bug alive on the end of the ice pick, the handle reversed

into a soft candle, setting all near the

31

towel with the jewels, so the display can be easily ogled

by the now awestruck men in La Fayette’s camp.

It is an Asian giant hornet, Vespa mandarinia, says private

first-class E.H. Thompson, who until that moment had

never been known to speak Latin.

The yak killer.

In unison at least three of the men exclaim: Good God!

Yellow-and-brown banded, the hirsute body of the

horrible insect is slightly more than two full inches in

length. It showcases an orange head with stunning

compound eyes and, altogether, the saw-toothed

mandibles and face of the wee monster are the width of

the nail of a man’s pinky. It has a three-inch wingspan,

hence its seldom-used Chinese moniker, the giant sparrow

bee, and it briefly buzzes those darkly transparent wings

out on the end of the ice pick, so that those men who do

not recoil from their movements will feel the amazing

draft of them in the stale tent.

The bloody gold chain lying broken there on the towel

with the woman’s charms is La Fayette’s, Corbett says,

not looking away from the super hornet. I know, because

the only time I ever saw him not wearing it was after he

lost it to Tiny Robinson in an all-night card game at the

officer’s club in Naini. Tiny sold it back to The Croc the

next day for thrice what he had in it.

Ah, so, Ibby says, briefly feigning the inflection of an

oriental detective. What do we make of that, gentlemen?!

How does a necklace belonging to Pete wind up shattered

in a pool of blood in...

The boudoir of Mademoiselle Constantine Acelet, says

Captain Jack Evans.

Yes, Jack. Thank you.

Well, Pete was a determined gambler, Corbett announces.

Maybe the mademoiselle won it from him in a friendly

game of dominatrix?

Scrutinizing the weakly animated Asian hornet, some

might say from a reckless distance, Private R.E.

Buchanan, who until that precise second had been mute

and expressionless throughout the entire evening,

explodes with laughter.

32

He has absolutely no control of himself and when he rises

from the doubling over effects of his runaway delight to

find Commissioner Ibbotson’s cold glare the yak killer

rattles off the tip of the ice pick, sticking itself to the left

lens of Buchanan’s eyeglasses like it had been shot onto

his face through the compressions of a blowgun. His

scream has too much falsetto, and as he madly rips off the

vermin-decorated spectacles there is a concurrent attempt

at a complete back flip, which he fails miserably to rotate,

landing neck-crusher style on the top of his head.

And for a good while thereafter the tears of weary and

anxious men spill at the hysterics of such instant karma

inside the cryptic confines of La Fayette’s unnerving

lodge. Corbett catches his breath first:

You’ll have to excuse the Commissioner, gentlemen. I

think he was teasing us about not knowing that the

delivery mechanism for Pete’s necklace was Pete himself.

The Commissioner did suffer a life-or-death equestrian

event this morning in a cold rain, weathers which

persisted for a full day of hard riding.

What’s the plan? Ibby questions, his eyes drifting among

the soldiers.

I suggest leaving three men here in the morning to begin

systematically packing this camp. You and I,

Commissioner, might plink about up north. Corporal Dink

located a terrific map in La Fayette’s quarters that we

believe details the locations of his tiger baits. The primary

site, I think, is about one mile straight north on the main

trail, the Kiwar Crest, at the convergence of a wonderful

set of ridges.

There are two bait sites farther south, Colonel.

Considerably more walking but the slope is comparatively

gradual.

I expect reinforcement to us by noon tomorrow, Coogan

concludes.

CORBETT WAKES in the night to an environment so

darkened that he questions if his eyes are open, whether

he’s gone deaf and blind. Maybe this is an event of

parasomnia and he is not truly awake at all. He lies there

33

wondering. Incredibly not one of the men is snoring or

even breathing heavily.

He turns into the blank wall of the ringing silence and is

almost back asleep when he hears the tigers: two, at least,

and initially the most vocal is so close that he perceives it

softly grunting with each spongy step.

A second tiger, farther out, woofs once as loudly as a big

dog and with that they take up a constant series of breezy

ahoos and velvety, guttural moans and birdy purrs,

pushing on passed the campsite to the south like ecliptic

destroyers dead-drifting through black curtains of smoke;

obviously, loosely, traveling together and communicating

across the lightless space with the erudite whisperings of

a monocyclic language gleaned in the moonless nights of

the Pleistocene. Far away from him in the distance, long

after the carry of their gentlest murmurings is beyond his

hearing, one of the tigers sneezes.

To himself, he says: God bless you, Shere Khan.

He fluffs up what he has for a pillow, brings his holstered

sidearm fully on into the cot and lights a cigarette.

BOTH FIELD PATROLS have timed themselves to return

together from opposite directions at exactly noon, where

they find nothing of the camp packed or even dismantled,

owing to the gruesome discovery of the three bodies.

The dead are young teenaged males who, it is

summarized, were the detail organized to excavate a new

latrine several hundred feet east of the old one. Two of the

dead coolies have been liberally powered with lime and

hastily shrouded in feed sacks and placed across rough-

hewn sawhorses behind the servant’s quarters, the only

non-temporary structure at this end of La Fayette’s

seventy-five-mile hunting concession. The other boy had

been killed outright and left at the dig.

Come see this, Dink says.

At the corporal’s direction, Captain Jack Evans Coogan

holds the binocular on the dead boy who’d been killed

clawing his way out of the hole. Coogan is steadily

maintaining the field of view when a thumb-size hornet

bombs in behind the

cadaver, which he is concluding his assessment of as two

more

34

hornets the size of hummingbirds streak from the pit.

Except for these unexpected and remorseless brushstrokes

of inexpressible horror, the patchy sunshine of the cool

spring day is a spectacular example of the best of the

Himalayan foothills. Jack Evans blanches as he hands the

binocular back to the corporal.

They examine the bloated, blackened faces of the other

boys behind the small wooden bunkhouse before all of the

morning’s reports are given in the cavernous chill of the

grand salon. There are plates of salamis, cheeses, olives

and crackers, for which Jack Evans and Dink have no

appetite.

The northern team has drawn nothing from its search of

the primary bait site or the country betwixt. Corbett is

explaining the circular travel route of the tigress and her

grown cubs, the ones he’d heard in the night, and showing

the men the small ivory buttons from a woman’s blouse

he’d found in the mud beneath the machan of the once

active bait site to the south, when a rider ties off his well-

lathered mount at the kedad and comes saluting his way

right up to the main table.

All present stand and shake the hand of Lieutenant G.B.

Toms, whose grandfather had regulated frontier India

quite capably in much more dangerous times, before the

Fusiliers became the Royal Rifles, before technology

mercifully made smoothbore muzzleloaders obsolete in

tiger country.

Toms downs the glass of water handed him. Pleasantries

are exchanged before he produces a folded page from the

breast pocket of his jacket and begins abridging a

translated dictum from La Fayette’s personal manservant,