Professional Documents

Culture Documents

BACK TO BACK: The Veto Record of Presidents Truman and Eisenhower

Uploaded by

AJHSSR JournalCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

BACK TO BACK: The Veto Record of Presidents Truman and Eisenhower

Uploaded by

AJHSSR JournalCopyright:

Available Formats

American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research (AJHSSR) 2023

American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research (AJHSSR)

e-ISSN : 2378-703X

Volume-07, Issue-10, pp-141-145

www.ajhssr.com

Research Paper Open Access

BACK TO BACK: The Veto Record of Presidents Truman and

Eisenhower

Samuel B. Hoff

George Washington Distinguished Professor Emeritus Dept. of History, Political Science, and Philosophy

Delaware State University

I. INTRODUCTION

There are a number of ways for the president to persuade Congress to support his position on policies. But

when cooperation gives way to conflict, the veto is often invoked. Veto authority of the chief executive has been

referred to as “the most important of powers connecting the national executive with the legislature” [1] and one

of the “unique American contributions to the theory and practice of government.” [2] How is it that successive

U.S. presidents of different backgrounds, political parties, and legislative approaches ended up with similar

records in vetoing bills they opposed? This research endeavors to address that question. The paper examines the

presidencies of Harry S Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower and how the aforementioned distinctions nonetheless

led to parallels in veto behavior. The study assesses the number and type of vetoes issued by Truman and

Eisenhower and compares their respective records to other presidents over American history. It also evaluates

why President Eisenhower had more success than President Truman in sustaining vetoes.

II. BACKGROUND

Harry S Truman was born in Missouri in May 1884. His family had a Scots-Irish and English heritage. He

resided in Missouri for the majority of his life. He was the oldest of three children, with a younger brother and

sister. After high school, he had an interest in attending the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, but his poor

eyesight prevented his appointment. He did not attend college. During World War I, he earned the rank of major

and was known for his organizational prowess. After the war, he held a series of posts, including a farmer, store

owner, clerk, and timekeeper. Later, he entered politics, working his way up from a county executive to U.S.

senator from his home state. A Democrat, he was tapped by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to serve as vice

president in 1944. The FDR-Truman team defeated the Republican team of Thomas Dewey and John Bricker,

garnering 56 percent of the popular vote and winning 36 of 48 states. When FDR passed less than three months

into his fourth term as president, Truman succeeded to the top office. As Truman took office, he had to learn on

the job at a time when the nation was grieving FDR’s passing and World War II was still taking place. [3]

Dwight David Eisenhower was born in Texas in October 1890. His family had a Swiss-German heritage. He

was the third of six brothers. His family moved to Abilene, Kansas when Ike was just two years old and he

attended high school there. Following high school, Ike earned an appointment to West Point, graduating there in

1915 with a commission as a second lieutenant. During World War I, he served as commander of a tank training

school in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, achieving the rank of lieutenant colonel. He continued his military career by

serving as a senior military aide and chief of staff to General Douglas MacArthur. After America entered World

War II, he held posts as chief of staff to the Third Army, commanding general to U.S. forces in Europe, and

supreme commander of all Allied forces in Europe. After U.S. victory in World War II, he served as chief of staff

of the U.S. Army and supreme commander of North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) forces in Europe, with

a two-year stint as president of Columbia University in between the latter two positions.

While he was recruited by both major parties to run for U.S. president in 1952, he ran as a Republican. Ike and

vice presidential candidate Richard Nixon defeated the Democrat ticket of Adlai Stevenson and Estes Kefauver,

earning 57 percent of the popular vote and winning 41 of 48 states. As he took office in January 1953, Ike had to

confront the Cold War with the Soviet Union and find a way to end the Korean War. [4]

AJHSSR Journal P a g e | 141

American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research (AJHSSR) 2023

III. LEGISLATIVE APPROACH

At the outset of his tenure as America’s 33rd president, Harry Truman encountered a party system in which

“many legislators felt that Congress had given up too much of its power to the executive branch, and many

Southern Democrats felt that the New Deal had unleashed forces that endangered their values.” [5] Hence,

President Truman could not automatically count on legislative support for his initiatives, even from his own party.

Still, having served a decade in the Senate, “he knew every personality in the Senate and many in the House. He

did not overestimate their resolve or underestimate their frailty.” [6] Several features of the Truman

administration’s approach to Congress are apparent. First, while he eschewed meddling in the internal affairs of

Congress, Truman chose decisive leadership rather than mediation to accomplish his legislative goals. [7] Second,

President Truman “used the telephone a great deal to untangle knots on Capitol Hill.” [8] Third, he chose not to

punish Southern Democrats who voted against his domestic proposals, a tactic that made progress more

challenging due to the latter faction retaining key leadership posts. [9]

President Eisenhower fought to uphold three principles throughout his inclusion in the legislative process;

these included federal restraint, cooperation between the public and private sectors, and fiscal responsibility. [10]

Among the political strategies he employed were hidden-hand leadership, instrumental use of language, avoiding

direct personal criticism of others, getting others to act based on his assessment of them, selective delegation, and

building public support for initiatives. Though Ike adapted to situations involving Congress, his political

philosophy remained constant over his time in office. [11] That is, he steered a moderate, pragmatic course,

emphasizing bipartisanship in foreign policy matters. [12]

IV. VETO STRATEGY

President Truman regarded the veto as “one of the most important aspects of his authority,” [13] and claimed

to have given veto messages “more of his attention than any other White House pronouncements.” [14]

A specific veto strategy for the Truman administration was formulated by political operatives James H. Rowe, Jr.

and Tommy Corcoran in December 1946. The memorandum suggested that President Truman make an effort

toward bipartisanship in the wake of the Republican takeover of Congress in the 1946 midterm election. But it

also recommended increased veto utilization should Republican policies hurt traditional Democrat constituencies.

[15] It has been observed that Truman’s tag for the ensuing legislative session—the “do nothing Congress,” could

have emanated from the aforementioned memorandum. [16] Clearly, the Bureau of the Budget played a crucial

role in veto actions by the Truman White House, having regained its responsibility for reviewing department and

agency recommendations for pending legislation after World War II. [17]

Sherman Adams, President Eisenhower’s chief of staff and close confidant in the White House, contends that

Ike had to rely on coalitions to get his programs through Congress after the Democrat sweep in the 1954 midterm

election. [18] The primary method by which Ike kept the most objectionable legislation from 1955 on from

becoming law was through veto use. [19] If not practicing a conscious veto strategy, the Eisenhower team at

least put in place procedures which facilitated the veto process. First, the Eisenhower administration established

the Office of Congressional Liaison to cultivate links with Congress. [20] Second, the Eisenhower White House

continued the procedure of having the Bureau of the Budget evaluate legislation and provide recommendations

about passage. Third, President Eisenhower included his cabinet in discussions about the value of legislation

more than any contemporary executive. [21] Finally, when discussing bills with Republican leaders in Congress,

Ike always asked about the likelihood of override should a veto be invoked. [22]

V. VETO USE

Presidential vetoes have been examined in various ways over different periods of American history. However,

one notable element in all such studies is the similarity between Presidents Truman and Eisenhower in number of

vetoes issued. For instance, if all types of vetoes are combined and measured in terms of frequency of use since

the outset of U.S. constitutional government through the Donald Trump presidency, Truman and Eisenhower rank

third an fourth, with 250 and 181 vetoes released, respectively. Only Presidents Franklin Roosevelt with 635 total

vetoes and Grover Cleveland with 584 outpaced Presidents Truman and Eisenhower in this regard. [23]

Vetoes can be subdivided by purpose of bill. A public bill pertains to general affairs and impacts a great

number of people, whereas a private bill usually pertains to an individual or defined limited group. In a study of

public bill vetoes from 1889 to 1989, Hoff finds that that Presidents Truman and Eisenhower rank second and

fifth, respectively, in annual number of such vetoes. If only second-term presidents are included, Truman and

Eisenhower rank second and third, respectively, in public bill veto issuance, with only FDR releasing more of this

type of veto. [24] These rankings are the same if the time frame is expanded through 2020. In analyzing influences

on frequency of annual public bill vetoes from 1889-1989, Hoff discovers that later year in office, later term in

office, high unemployment, number of public laws passed, and being a succession president all significantly

increase such vetoes, whereas majority partisan support reduces veto frequency overall. [25] Applying the latter

findings to Presidents Truman and Eisenhower, all of previous variables help explain annual public bill veto

AJHSSR Journal P a g e | 142

American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research (AJHSSR) 2023

behavior during their tenure, although President Truman actually vetoed more total public bills during unified

than divided party government. [26]

Most private bill vetoes by American presidents were released over the century from 1869 to 1969. Hoff’s

study of private bill veto frequency over that period revealed that Presidents Truman and Eisenhower rank third

and fourth, respectively, in total private bill vetoes, with only Presidents Cleveland and Franklin Roosevelt issuing

more. Hoff discovers that over the aforementioned century, variables like being involved in a military conflict,

election year, number of public bill vetoes, and number of private laws significantly increase likelihood of private

bill vetoes, whereas military background, term in office, business failure rate, extensive change in cabinet

personnel, and party control significantly reduce likelihood of such vetoes. [27]

Pocket vetoes are permitted under the Constitution when the president has less than ten days left in the

legislative session to consider the merits of legislation. Rather than signing, ignoring, or outrightly vetoing a bill,

chief executives can simply wait until after Congress adjourns to take action. Under such circumstances, the veto

cannot be overridden, although it can be reintroduced at the outset of a new legislative session. If all pocket vetoes

are counted over American constitutional history, Franklin Roosevelt and Grover Cleveland rank first and second

in total use, followed by Presidents Eisenhower and Truman in third and fourth place, respectively. In a study of

catalysts of pocket vetoes from 1889 to 1989, Hoff shows that later year in a term, number of public laws, and

high level of unemployment all significantly increase frequency of such vetoes annually. [28]

Overall, the large number of vetoes issued by Presidents Truman and Eisenhower can be traced to both

proximate and long-term factors. For one, both presidents followed FDR’s administration, which saw the most

vetoes issued in American history, 635 in all. Second, both Truman and Eisenhower encountered periods where

they faced an opposition party-controlled Congress. Third, private bills still went through the traditional route to

passage, making them subject to veto; that procedure changed in ensuing decades. Finally, Presidents Truman

and Eisenhower served before the time when chief executives employed tactics which mimicked the veto—such

as bill signing statements—and therefore subsequently lessened reliance on formal powers.

VI. VETO OVERRIDES

Veto overrides occur when two-thirds of both chambers of Congress vote to oppose a veto while repeating

earlier endorsement for a bill or joint resolution.

From 1789 up to 2021, encompassing the forty-five presidencies from George Washington through Donald

Trump, presidential overrides have only transpired on 112 of 1518 regular vetoes, or just 7.4 percent. [29] That

the president is seemingly dominant in protecting vetoes from override masks trends which are apparent if both

parts of the override process are examined. In his study of influences on veto overrides over the century time from

1889 to 1989, Hoff discovers that while presidents enjoy an 80 percent success rate in having their vetoes sustained

by the first chamber to vote on override, the percentage is nearly reversed when the second chamber’s action is

considered. Indeed, there is a 70 percent likelihood of veto override if the second chamber votes to do so. [30]

As opposed to the several similarities between Presidents Truman and Eisenhower pertaining to veto use,

statistics and circumstances pertaining to veto overrides for the two chief executives diverge. For example,

Dwight Eisenhower vetoed a total of 73 bills by regular means, of which just two, or 2.7 percent, were overridden.

Conversely, President Truman experienced overrides on 12 of his 180 regular vetoes, or 6.7 percent. Further,

President Truman is dubiously tied with President Gerald Ford for second place in veto overrides suffered with

12, trailing only the 15 overrides against President Andrew Johnson’s regular vetoes. [31]

In a study of veto overrides from 1940 through 1980, Hoff adopts a systemic model to assess probability of

second-house override. The results show that while first chamber veto override percentage, frequency of

appearances before a joint session of Congress, and involvement in a major military conflict significantly increase

probability of final override, positive partisan support and number of executive agreements have a major impact

in reducing likelihood of override. Interestingly, the systemic model perfectly predicts veto override actions for

President Eisenhower, while correctly predicting second-chamber veto override decisions in 68.8 percent of

instances for President Truman. [32]

Of the eleven public bill vetoes and one private bill veto overridden by Congress during the Truman

administration, none elicited more controversy than that dealing with the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947. The act was

designed to outlaw closed union shops, empowering the attorney general to secure an injunction against strikes

which affected national health and safety while also barring unions from contributing to political campaigns.

President Truman vetoed the aforementioned bill on June 20, 1947, but the veto was overridden the same day by

a 331-83 vote in the House of Representatives and a 68-35 vote in the U.S. Senate. The stunning reversal was the

first veto override faced by the Truman White House. However, a little more than four years later, President

Truman exacted revenge by signing a bill reversing several components of the Taft-Hartley Act. [33]

The two successful overrides against President Eisenhower’s vetoes transpired during his final two years in

office. One of the public bills which was vetoed dealt with appropriations for various departments and agencies,

while the second sought adjustment of compensation for federal employees.

AJHSSR Journal P a g e | 143

American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research (AJHSSR) 2023

Although there was general consensus among President Eisenhower’s staff to veto the compensation bill, records

indicate that there was disagreement on whether to veto the appropriation legislation. In both instances of override,

the House and Senate acted the same day and just one day after the veto was issued. [34]

VII. CONCLUSION: SIMILAR ACHIEVEMENTS AND LEGACY

Presidents Truman and Eisenhower enjoyed similar accomplishments in the domestic area. For Truman, the

Fair Deal demonstrated his commitment to reducing unemployment, raising the minimum wage, expanding public

housing, and protecting workers and veterans. Too, President Eisenhower supported expanding social security

benefits and an increase in the minimum wage. While President Truman favored new public works programs,

President Eisenhower backed legislation creating the interstate highway system and the St. Lawrence Seaway.

Even if to a different degree, both chief executives helped to advance civil rights. In the foreign policy realm,

both presidents ended a hot war and managed the Cold War with the Soviet Union. [35]

Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower were friends before 1952. They parted over a series of

misunderstandings, which were later forgiven. That is a good thing, because just as the successive chief executives

demonstrated similar veto behavior, so they are regarded in terms of presidential performance and popularity. In

2017 and 2021 surveys of historians by Sienna College, Eisenhower and Truman ranked fifth and sixth

respectively among all chief executives in U.S. history up to Joe Biden. [36] Back to back, in more ways than one.

Table 1: Rankings of Presidents in Veto Use

A. Ranked Total Number of All Vetoes, 1789-2021

1. FDR=635

2. Cleveland=584

3. Truman=250

4. Eisenhower=181

5. Grant=93

B. Ranked Total Public Bill Vetoes, 1889-2021

1. FDR=105

2. Truman=55

3. Ford=46

4. Reagan=37

5. Eisenhower=35

C. Ranked Total Public Bill Vetoes by Second-Term Presidents,

1889-2021

1. FDR=84

2. Truman=26

3. Eisenhower=22

4. Reagan=20

5. Wilson/Clinton=19

D. Ranked Total Private Bill Vetoes, 1869-1969

1. Cleveland=295

2. FDR=187

3. Truman=84

4. Eisenhower=27

5. Grant=25

E. Ranked Total Pocket Vetoes by Presidents, 1789-2021

1. FDR=263

2. Cleveland=238

3. Eisenhower=108

4. Truman=70

5. Grant=48

AJHSSR Journal P a g e | 144

American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research (AJHSSR) 2023

NOTES

[1] Edward C. Mason. 1890. The Veto Power, 1789-1889. New York, NY:

Russell and Russell, p. 1.

[2] John L.B. Higgins. 1952. Presidential Vetoes, 1889-1929. Washington, DC: Georgetown University

(dissertation).

[3] William DeGregorio. 2005. The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents. Norwalk, CT: The Eason Press; David C.

Whitney and Robin Vaughn Whitney. 2005. The American Presidents. New York: Reader’s Digest

Association.

[4] Ibid.

[5] William E. Pemberton. 1989. Harry S. Truman: Fair Dealer and Cold Warrior. Boston, MA: Twayne

Publishers, p. 62.

[6] Robert H. Ferrell. 1994. Harry S. Truman: A Life. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, p. 184.

[7] Pemberton, 1989.

[8] Robert J. Donovan. 1977. Conflict and Crisis: The Presidency of Harry S Truman, 1945-1948. New York,

NY: W.W. Norton and Company, p. 271.

[9] Donald R. McCoy. 1984. The Presidency of Harry S. Truman. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

[10] Chester J. Pach and Elmo Richardson. 1991. The Presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower. Lawrence, KS:

University Press of Kansas.

[11] Blanche Wiesen Cook 1984. The Declassified Eisenhower. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

[12] David Broder. 1972. The Party’s Over: The Failure of American Politics. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

[13] Herman Finer. 1960. The Presidency. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press

[14] Robert J. Spitzer. 1988. The Presidential Veto: Touchstone of the American Presidency. Albany, NY: State

University of New York Press.

[15] Charles Cameron. 2000. Veto Bargaining: Presidents and the Politics of Negative Power. New York, NY:

Cambridge University Press.

[16] David McCollough. 1992. Truman. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

[17] Richard A. Watson. 1993. Presidential Vetoes and Public Policy. Laurence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

[18] Sherman Adams. 1961. Firsthand Report. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

[19] Michael K. Birkner. 2013. “More to Induce Than Demand: Eisenhower and Congress,” Congress and the

Presidency, 40, p. 165-194.

[20] Robert E. DiClerico. 1990. The American President. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

[21] Michael Foley and John E. Owens. 1996. Congress and the Presidency in a Separated System. New York,

NY: St. Martin’s Press.

[22] Watson, 1993.

[23] “Presidential Vetoes.” 2022. Washington, DC: U.S. House of Representatives: History, Art, and Archives.

[24] Samuel B. Hoff. 1991. “Saying No: Presidential Support and the Veto Process, 1889-1989,” American Politics

Quarterly, 19:3, July, p. 310-323.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Samuel B. Hoff. 2001. “Presidential Vetoes Amid Party Majorities,” National Social Science Journal, 17:1, p.

1-20.

[27] Samuel B. Hoff, 2003. “None for One: Examining Influences on Private Bill Vetoes,” New England Journal of

Political Science, 1:1, p. 1-33.

[28] Samuel B. Hoff. 1994. “The Presidential Pocket Veto: Its Use and Legality,” Journal of Policy History, 6:2, p.

188-208.

[29] “Presidential Vetoes,” 2002.

[30] Samuel B. Hoff. 1992. “Presidential Support and Veto Overrides, 1889-1988,” Midsouth Political Science

Journal, 13: Summer, p. 173-189.

[31] “Presidential Vetoes,” 2002.

[32] Samuel B. Hoff. 2019. “Factors Which Influence Congress’s Decision to Override a Presidential Veto: A Study

of the Veto Process,” International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies, 6:6, p. 24-34.

[33] Samuel B. Hoff. 2007. “Fair Deal or No Deal: The Veto Record of President Harry Truman,” Lincoln Journal

of Social and Political Thought, 5:1, p. 38-66.

[34] Samuel B. Hoff. 2016. “Ike No Like: The Eisenhower Presidency and the Veto Power, 1953-1961,” National

Social Science Journal, 46: 2, p. 25-35.

[35] Hoff, 2007; Hoff, 2016.

[36] “American Presidents: Greatest and Worst.” 2022. scri.sienna.edu, June 22.

AJHSSR Journal P a g e | 145

You might also like

- Democrats and Progressives: The 1948 Presidential Election as a Test of Postwar LiberalismFrom EverandDemocrats and Progressives: The 1948 Presidential Election as a Test of Postwar LiberalismNo ratings yet

- History RP RisDocument7 pagesHistory RP RisGopal MishraNo ratings yet

- The Presidential Difference: Leadership Style from FDR to Barack Obama - Third EditionFrom EverandThe Presidential Difference: Leadership Style from FDR to Barack Obama - Third EditionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Two-Presidencies Thesis Holds ThatDocument6 pagesTwo-Presidencies Thesis Holds Thatkristaclarkbillings100% (2)

- Whistle Stop: How 31,000 Miles of Train Travel, 352 Speeches, and a Little Midwest Gumption Saved the Presidency of Harry TrumanFrom EverandWhistle Stop: How 31,000 Miles of Train Travel, 352 Speeches, and a Little Midwest Gumption Saved the Presidency of Harry TrumanRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (21)

- Military Classics Seminar Review of SamuDocument9 pagesMilitary Classics Seminar Review of SamuFaseeh Ud dinNo ratings yet

- The Greatest American Presidents: Including a Short Course on All the Presidents and Political PartiesFrom EverandThe Greatest American Presidents: Including a Short Course on All the Presidents and Political PartiesNo ratings yet

- Great PresidentsDocument216 pagesGreat Presidentsdarius100% (1)

- A Safe Haven: Harry S. Truman and the Founding of IsraelFrom EverandA Safe Haven: Harry S. Truman and the Founding of IsraelRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Harry S Truman Research PaperDocument4 pagesHarry S Truman Research Papernlaxlvulg100% (1)

- President Trump and American Soft Power Anand KoleDocument8 pagesPresident Trump and American Soft Power Anand KoleAnand KoleNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13Document2 pagesChapter 13Paul JonesNo ratings yet

- Political Conspiracies in America: A ReaderFrom EverandPolitical Conspiracies in America: A ReaderRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Liberals and The Communist Control Act of 1954Document17 pagesLiberals and The Communist Control Act of 1954Ari El VoyagerNo ratings yet

- Partisan Balance: Why Political Parties Don't Kill the U.S. Constitutional SystemFrom EverandPartisan Balance: Why Political Parties Don't Kill the U.S. Constitutional SystemNo ratings yet

- The Modern Presidency and Civil Rights Rhetoric On Race From Roosevelt To Nixon by Garth E. PauleyDocument269 pagesThe Modern Presidency and Civil Rights Rhetoric On Race From Roosevelt To Nixon by Garth E. PauleykennyspunkaNo ratings yet

- PSC 274 - Constraints on Presidential Foreign PolicyDocument8 pagesPSC 274 - Constraints on Presidential Foreign PolicyJason BrownNo ratings yet

- Recarving Rushmore: Ranking the Presidents on Peace, Prosperity, and LibertyFrom EverandRecarving Rushmore: Ranking the Presidents on Peace, Prosperity, and LibertyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- How Politicians Exploit Fear to Gain PowerDocument10 pagesHow Politicians Exploit Fear to Gain PowerSaffiNo ratings yet

- How America Escapes Its Conspiracy-Theory Crisis - The New YorkerDocument13 pagesHow America Escapes Its Conspiracy-Theory Crisis - The New YorkerrustycarmelinaNo ratings yet

- Unmasking the Administrative State: The Crisis of American Politics in the Twenty-First CenturyFrom EverandUnmasking the Administrative State: The Crisis of American Politics in the Twenty-First CenturyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- How Ideology Played A Role in The Iraq WarDocument12 pagesHow Ideology Played A Role in The Iraq WarFaiza Ikram100% (1)

- United States v. Nixon Research PaperDocument5 pagesUnited States v. Nixon Research Paperegzt87qn100% (1)

- Constitutional Conservatism: Liberty, Self-Government, and Political ModerationFrom EverandConstitutional Conservatism: Liberty, Self-Government, and Political ModerationNo ratings yet

- Curcio Interview ArticleDocument2 pagesCurcio Interview Articleapi-720373742No ratings yet

- The Trump Survival Guide: Everything You Need to Know About Living Through What You Hoped Would Never HappenFrom EverandThe Trump Survival Guide: Everything You Need to Know About Living Through What You Hoped Would Never HappenRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (20)

- Why It Matters: Why Do People Join Political Parties? Why Does America Have A Two-Party System?Document20 pagesWhy It Matters: Why Do People Join Political Parties? Why Does America Have A Two-Party System?Rsvz AikiNo ratings yet

- Challengers to Duopoly: Why Third Parties Matter in American Two-Party PoliticsFrom EverandChallengers to Duopoly: Why Third Parties Matter in American Two-Party PoliticsNo ratings yet

- First Attempt at Presidential ImpeachmentDocument13 pagesFirst Attempt at Presidential ImpeachmentBenjamin BrownNo ratings yet

- Guardians of Liberty: Freedom of the Press and the Nature of NewsFrom EverandGuardians of Liberty: Freedom of the Press and the Nature of NewsNo ratings yet

- Let's AnalyzeDocument2 pagesLet's AnalyzeVirgelyn Mikay Sardoma-Cumatcat MonesNo ratings yet

- Impeaching the President: Past, Present, and FutureFrom EverandImpeaching the President: Past, Present, and FutureRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (2)

- Truman'S Anti Communism: A Climate of FearDocument2 pagesTruman'S Anti Communism: A Climate of FearLydia SmithNo ratings yet

- The American Presidency From 1933 To 1961Document12 pagesThe American Presidency From 1933 To 1961Roosevelt AkumeNo ratings yet

- A Divided Union The USA, 1945-70 Electronic TextbookDocument35 pagesA Divided Union The USA, 1945-70 Electronic TextbookJack LinsteadNo ratings yet

- The American Government, Inc., A Work of Fiction and Political SatireFrom EverandThe American Government, Inc., A Work of Fiction and Political SatireNo ratings yet

- Bad For Democracy How The Presidency Undermines The Power of The PeopleDocument272 pagesBad For Democracy How The Presidency Undermines The Power of The PeoplePaulNo ratings yet

- The Southern Manifesto: Massive Resistance and the Fight to Preserve SegregationFrom EverandThe Southern Manifesto: Massive Resistance and the Fight to Preserve SegregationNo ratings yet

- RTE AffDocument118 pagesRTE AffsaminNo ratings yet

- Populism and Globalization The Return of Nationalism and The Global Liberal OrderDocument533 pagesPopulism and Globalization The Return of Nationalism and The Global Liberal OrderYannick van der HeijdenNo ratings yet

- LibermanDocument10 pagesLibermanChiara D'AloiaNo ratings yet

- President Truman and The Origin of Cold WarDocument10 pagesPresident Truman and The Origin of Cold WarSatyam MalakarNo ratings yet

- Schulman_MadeByHistoryDocument3 pagesSchulman_MadeByHistoryREDEASTWOODNo ratings yet

- Implementing Public PolicyDocument200 pagesImplementing Public PolicyTotok Sgj100% (1)

- The Red ScareDocument11 pagesThe Red ScareNick TipswordNo ratings yet

- Summary 3 - The Origins of Massive RetaliationDocument2 pagesSummary 3 - The Origins of Massive RetaliationIntan NabilaNo ratings yet

- Civil Rights Historiography 2008 s2Document31 pagesCivil Rights Historiography 2008 s2kennyspunkaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 The Vice President and The First LadyDocument8 pagesLesson 2 The Vice President and The First LadyEsther EnriquezNo ratings yet

- ExcerptDocument10 pagesExcerptIrfan KhuhroNo ratings yet

- Mccarthy Era Term PaperDocument8 pagesMccarthy Era Term Paperafdtyfnid100% (1)

- (Joya) Taub 2016 - The Rise of American AuthoritarianismDocument36 pages(Joya) Taub 2016 - The Rise of American AuthoritarianismAlex AguilarNo ratings yet

- US Democracy Promotion: The Clinton and Bush AdministrationsDocument25 pagesUS Democracy Promotion: The Clinton and Bush AdministrationsmemoNo ratings yet

- How to Reverse Failed PoliciesDocument12 pagesHow to Reverse Failed PoliciesarielNo ratings yet

- THE INFLUENCE OF COMPETENCE ON THE PERFORMANCE OF ALUMNI GRADUATES IN 2020 AND 2021 MAJORING IN MANAGEMENT, FACULTY OF ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS, MATARAM UNIVERSITYDocument6 pagesTHE INFLUENCE OF COMPETENCE ON THE PERFORMANCE OF ALUMNI GRADUATES IN 2020 AND 2021 MAJORING IN MANAGEMENT, FACULTY OF ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS, MATARAM UNIVERSITYAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Online Social Shopping Motivation: A Preliminary StudyDocument11 pagesOnline Social Shopping Motivation: A Preliminary StudyAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Mga Kagamitang Pampagtuturong Ginagamit sa mga Asignaturang FilipinoDocument10 pagesMga Kagamitang Pampagtuturong Ginagamit sa mga Asignaturang FilipinoAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- What Is This “Home Sweet Home”: A Course-Based Qualitative Exploration of the Meaning of Home for Child and Youth Care StudentsDocument6 pagesWhat Is This “Home Sweet Home”: A Course-Based Qualitative Exploration of the Meaning of Home for Child and Youth Care StudentsAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Intentional Child and Youth Care Life-Space Practice: A Qualitative Course-Based InquiryDocument6 pagesIntentional Child and Youth Care Life-Space Practice: A Qualitative Course-Based InquiryAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- SEXUAL ACTS COMMITTED BY CHILDRENDocument7 pagesSEXUAL ACTS COMMITTED BY CHILDRENAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- MGA SALIK NA NAKAAAPEKTO SA ANTAS NG PAGUNAWA SA PAGBASA NG MGA MAG-AARAL SA JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOLDocument11 pagesMGA SALIK NA NAKAAAPEKTO SA ANTAS NG PAGUNAWA SA PAGBASA NG MGA MAG-AARAL SA JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOLAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Paglilinang ng mga Kasanayan at Pamamaraan ng Pagtuturo ng Wikang FilipinoDocument12 pagesPaglilinang ng mga Kasanayan at Pamamaraan ng Pagtuturo ng Wikang FilipinoAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Impact Of Educational Resources on Students' Academic Performance in Economics: A Study of Some Senior Secondary Schools in Lagos State Educational District OneDocument26 pagesImpact Of Educational Resources on Students' Academic Performance in Economics: A Study of Some Senior Secondary Schools in Lagos State Educational District OneAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- IMPACT OF FISCAL POLICY AND MONETARY POLICY ON THE ECONOMIC GROWTH OF NIGERIA (1980 – 2016)Document22 pagesIMPACT OF FISCAL POLICY AND MONETARY POLICY ON THE ECONOMIC GROWTH OF NIGERIA (1980 – 2016)AJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Teaching and Learning: Ang Pananaw ng mga PreService Teachers ng Western Mindanao State University sa Pagiging Epektibo ng Paggamit ng ICT sa Pagtuturo at Pagkatuto ng WikaDocument10 pages21st Century Teaching and Learning: Ang Pananaw ng mga PreService Teachers ng Western Mindanao State University sa Pagiging Epektibo ng Paggamit ng ICT sa Pagtuturo at Pagkatuto ng WikaAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Mga Batayan sa Pagpili ng Asignaturang Medyor ng mga Magaaral ng Batsilyer ng Sekundaryang Edukasyon sa Pampamahalaang Unibersidad ng Kanlurang MindanaoDocument14 pagesMga Batayan sa Pagpili ng Asignaturang Medyor ng mga Magaaral ng Batsilyer ng Sekundaryang Edukasyon sa Pampamahalaang Unibersidad ng Kanlurang MindanaoAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- NORTH LAMPUNG REGIONAL POLICE'S EFFORTS TO ERADICATE COCKFIGHTINGDocument3 pagesNORTH LAMPUNG REGIONAL POLICE'S EFFORTS TO ERADICATE COCKFIGHTINGAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- COMPARATIVESTUDYBETWENTHERMAL ENGINE PROPULSION AND HYBRID PROPULSIONDocument11 pagesCOMPARATIVESTUDYBETWENTHERMAL ENGINE PROPULSION AND HYBRID PROPULSIONAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Pagkabalisa sa Pagsasalita Gamit ang Wikang Filipino ng mga mag-aaral sa Piling Paaralan sa Zamboanga PeninsulaDocument9 pagesPagkabalisa sa Pagsasalita Gamit ang Wikang Filipino ng mga mag-aaral sa Piling Paaralan sa Zamboanga PeninsulaAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Financial Conditions on Taxpayer Compliance with Tax Socialization and Tax Awareness as Moderating VariablesDocument7 pagesThe Influence of Financial Conditions on Taxpayer Compliance with Tax Socialization and Tax Awareness as Moderating VariablesAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Study of Concept Berhala Island Cultural Festival As The First of Culture Festival in Indonesia's Outer IslandsDocument8 pagesStudy of Concept Berhala Island Cultural Festival As The First of Culture Festival in Indonesia's Outer IslandsAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Vietnamese EFL students’ perception and preferences for teachers’ written feedbackDocument7 pagesVietnamese EFL students’ perception and preferences for teachers’ written feedbackAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Halal Product Quality, Service Quality, and Religiosity On El Marom Store Customer Satisfaction and LoyaltyDocument9 pagesThe Influence of Halal Product Quality, Service Quality, and Religiosity On El Marom Store Customer Satisfaction and LoyaltyAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Kakayahan NG Mga Pre-Service Teachers Sa Pagtuturo NG Asignaturang FilipinoDocument9 pagesKakayahan NG Mga Pre-Service Teachers Sa Pagtuturo NG Asignaturang FilipinoAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- “Mga Salik na Nakaaapekto sa Pagkatuto ng Mag-aaral sa Asignaturang Filipino”Document12 pages“Mga Salik na Nakaaapekto sa Pagkatuto ng Mag-aaral sa Asignaturang Filipino”AJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Social Media Marketing and Strategy Analysis of CasetifyDocument8 pagesSocial Media Marketing and Strategy Analysis of CasetifyAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Parental Involvement in The Implementation of Modular Distance Learning Approach Among Identified School in Botolan District, Division of ZambalesDocument15 pagesParental Involvement in The Implementation of Modular Distance Learning Approach Among Identified School in Botolan District, Division of ZambalesAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Innovation Behavior and Organizational Commitment Mediate The Effect of Job Happiness On Employee Performance at The Faculty of Medicine University of MataramDocument10 pagesInnovation Behavior and Organizational Commitment Mediate The Effect of Job Happiness On Employee Performance at The Faculty of Medicine University of MataramAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- The Problem of Literary Translation With Particular Attention To The Case of The Sicilian Writer Andrea Camilleri Translated Into SpanishDocument14 pagesThe Problem of Literary Translation With Particular Attention To The Case of The Sicilian Writer Andrea Camilleri Translated Into SpanishAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Mga Estratehiyang Pinakaginagamit Sa Pagsulat Sa Filipino NG Mga Mag-Aaral NG Batsilyer NG Sekundaryang Edukasyon Sa Pampamahalaang Pamantasan NG Kanlurang MindanaoDocument13 pagesMga Estratehiyang Pinakaginagamit Sa Pagsulat Sa Filipino NG Mga Mag-Aaral NG Batsilyer NG Sekundaryang Edukasyon Sa Pampamahalaang Pamantasan NG Kanlurang MindanaoAJHSSR Journal100% (1)

- Implementation of SEM Partial Least Square in Analyzing The UTAUT ModelDocument10 pagesImplementation of SEM Partial Least Square in Analyzing The UTAUT ModelAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Exploring Innovative Pedagogies: A Collaborative Study of Master'sstudents at Universitat Jaume IDocument8 pagesExploring Innovative Pedagogies: A Collaborative Study of Master'sstudents at Universitat Jaume IAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Ipsas Adoption and Financial Reporting Quality in Public Sector of The South Western Nigeria: Assessment of The Mediating Role of Contingency FactorsDocument15 pagesIpsas Adoption and Financial Reporting Quality in Public Sector of The South Western Nigeria: Assessment of The Mediating Role of Contingency FactorsAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Sustainability Reporting Perusahaan Penerima Awardsdi IndonesiaDocument7 pagesSustainability Reporting Perusahaan Penerima Awardsdi IndonesiaAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- CasesDocument92 pagesCasesLeonardo EgcatanNo ratings yet

- Third Division June 6, 2018 G.R. No. 234499 RUDY L. RACPAN, Petitioner SHARON BARROGA-HAIGH, Respondent Decision Velasco, JR., J.: Nature of The CaseDocument9 pagesThird Division June 6, 2018 G.R. No. 234499 RUDY L. RACPAN, Petitioner SHARON BARROGA-HAIGH, Respondent Decision Velasco, JR., J.: Nature of The CaseRemy BedañaNo ratings yet

- Mariano V COMELEC 1995Document4 pagesMariano V COMELEC 1995Yanny YuneNo ratings yet

- Index: Judicial Activism 3 Judicial Restraint 6Document52 pagesIndex: Judicial Activism 3 Judicial Restraint 6T100% (1)

- FEDERICO YLARDE and ADELAIDA DORONIODocument2 pagesFEDERICO YLARDE and ADELAIDA DORONIOphgmbNo ratings yet

- The FIR in Pakistan, Under CRPCDocument6 pagesThe FIR in Pakistan, Under CRPCAizaz AlamNo ratings yet

- Property Surveying Classification of Property SurveyingDocument2 pagesProperty Surveying Classification of Property SurveyingFrancisco TimNo ratings yet

- Stelor Productions v. Silvers, Et Al - Document No. 28Document49 pagesStelor Productions v. Silvers, Et Al - Document No. 28Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Auction Sale of Unserviceable and Disposable Government PropertiesDocument2 pagesAuction Sale of Unserviceable and Disposable Government PropertiesJean RayNo ratings yet

- Tañada vs. Tuvera ruling on publicationDocument27 pagesTañada vs. Tuvera ruling on publicationcarl fuerzasNo ratings yet

- Code of Ethics For Professional Accountants in The PhilippinesDocument7 pagesCode of Ethics For Professional Accountants in The Philippineshope4me100% (2)

- F002 Admin. PRCDocument24 pagesF002 Admin. PRCLeolaida AragonNo ratings yet

- 802 TenantsAffidavit DeclarationDocument8 pages802 TenantsAffidavit DeclarationGhadahNo ratings yet

- 03 GR 169958Document3 pages03 GR 169958Mabelle ArellanoNo ratings yet

- A Study On Impact of GST On RetailersDocument9 pagesA Study On Impact of GST On RetailersKrishna Nandhini VijiNo ratings yet

- DGST R TRANSPORT V YuDocument1 pageDGST R TRANSPORT V YuJan-Lawrence OlacoNo ratings yet

- Stop ForeclosureDocument42 pagesStop ForeclosureJeff Wilner100% (3)

- Karnataka State Law University Syllabus-3year LLBDocument44 pagesKarnataka State Law University Syllabus-3year LLBswathipalaniswamy100% (9)

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument3 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Conditional Deed of Sale With SPADocument3 pagesConditional Deed of Sale With SPABang Bang Costanilla Villamor100% (1)

- Petitioners Vs Vs Respondents Augusto P. Jimenez, Jr. Fred Henry V. MarallagDocument5 pagesPetitioners Vs Vs Respondents Augusto P. Jimenez, Jr. Fred Henry V. MarallagPoPo MillanNo ratings yet

- Rti and Role of MediaDocument8 pagesRti and Role of MediaaakankshaNo ratings yet

- GR No. 93666 - Court upholds DOLE's authority to revoke alien employment permitDocument4 pagesGR No. 93666 - Court upholds DOLE's authority to revoke alien employment permitRicky James Laggui Suyu100% (1)

- KIO Demands Federal Union Before Surrendering WeaponsDocument2 pagesKIO Demands Federal Union Before Surrendering WeaponsPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Gallardo vs. Soliman - Case DigestDocument8 pagesHeirs of Gallardo vs. Soliman - Case DigestDeb BieNo ratings yet

- PP vs. Rolando BagsicDocument13 pagesPP vs. Rolando Bagsicchristian villamanteNo ratings yet

- Democracy in Africa A Literature Review: December 2019Document55 pagesDemocracy in Africa A Literature Review: December 2019kpodee thankgodNo ratings yet

- Constitution JeopardyDocument46 pagesConstitution JeopardyAlexandria HarrisNo ratings yet

- Cyber LawDocument40 pagesCyber LawNikki PrakashNo ratings yet

- Candidate ID formDocument2 pagesCandidate ID formdeliailona555No ratings yet

- Game Change: Obama and the Clintons, McCain and Palin, and the Race of a LifetimeFrom EverandGame Change: Obama and the Clintons, McCain and Palin, and the Race of a LifetimeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (572)

- The Russia Hoax: The Illicit Scheme to Clear Hillary Clinton and Frame Donald TrumpFrom EverandThe Russia Hoax: The Illicit Scheme to Clear Hillary Clinton and Frame Donald TrumpRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (11)

- Nine Black Robes: Inside the Supreme Court's Drive to the Right and Its Historic ConsequencesFrom EverandNine Black Robes: Inside the Supreme Court's Drive to the Right and Its Historic ConsequencesNo ratings yet

- The Smear: How Shady Political Operatives and Fake News Control What You See, What You Think, and How You VoteFrom EverandThe Smear: How Shady Political Operatives and Fake News Control What You See, What You Think, and How You VoteRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (16)

- The Courage to Be Free: Florida's Blueprint for America's RevivalFrom EverandThe Courage to Be Free: Florida's Blueprint for America's RevivalNo ratings yet

- Thomas Jefferson: Author of AmericaFrom EverandThomas Jefferson: Author of AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (107)

- Commander In Chief: FDR's Battle with Churchill, 1943From EverandCommander In Chief: FDR's Battle with Churchill, 1943Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (16)

- Socialism 101: From the Bolsheviks and Karl Marx to Universal Healthcare and the Democratic Socialists, Everything You Need to Know about SocialismFrom EverandSocialism 101: From the Bolsheviks and Karl Marx to Universal Healthcare and the Democratic Socialists, Everything You Need to Know about SocialismRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (42)

- Modern Warriors: Real Stories from Real HeroesFrom EverandModern Warriors: Real Stories from Real HeroesRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Shadow War: Inside Russia's and China's Secret Operations to Defeat AmericaFrom EverandThe Shadow War: Inside Russia's and China's Secret Operations to Defeat AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- Witch Hunt: The Story of the Greatest Mass Delusion in American Political HistoryFrom EverandWitch Hunt: The Story of the Greatest Mass Delusion in American Political HistoryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Stonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonFrom EverandStonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (21)

- Crimes and Cover-ups in American Politics: 1776-1963From EverandCrimes and Cover-ups in American Politics: 1776-1963Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (26)

- The Red and the Blue: The 1990s and the Birth of Political TribalismFrom EverandThe Red and the Blue: The 1990s and the Birth of Political TribalismRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (29)

- A Short History of the United States: From the Arrival of Native American Tribes to the Obama PresidencyFrom EverandA Short History of the United States: From the Arrival of Native American Tribes to the Obama PresidencyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (19)

- Blood Money: Why the Powerful Turn a Blind Eye While China Kills AmericansFrom EverandBlood Money: Why the Powerful Turn a Blind Eye While China Kills AmericansRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- The Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H.W. BushFrom EverandThe Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H.W. BushRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- An Ordinary Man: The Surprising Life and Historic Presidency of Gerald R. FordFrom EverandAn Ordinary Man: The Surprising Life and Historic Presidency of Gerald R. FordRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- The Great Gasbag: An A–Z Study Guide to Surviving Trump WorldFrom EverandThe Great Gasbag: An A–Z Study Guide to Surviving Trump WorldRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (9)

- 1960: LBJ vs. JFK vs. Nixon--The Epic Campaign That Forged Three PresidenciesFrom Everand1960: LBJ vs. JFK vs. Nixon--The Epic Campaign That Forged Three PresidenciesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (50)

- Power Grab: The Liberal Scheme to Undermine Trump, the GOP, and Our RepublicFrom EverandPower Grab: The Liberal Scheme to Undermine Trump, the GOP, and Our RepublicNo ratings yet

- Confidence Men: Wall Street, Washington, and the Education of a PresidentFrom EverandConfidence Men: Wall Street, Washington, and the Education of a PresidentRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (52)

- The Magnificent Medills: The McCormick-Patterson Dynasty: America's Royal Family of Journalism During a Century of Turbulent SplendorFrom EverandThe Magnificent Medills: The McCormick-Patterson Dynasty: America's Royal Family of Journalism During a Century of Turbulent SplendorNo ratings yet

- Camelot's Court: Inside the Kennedy White HouseFrom EverandCamelot's Court: Inside the Kennedy White HouseRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Reading the Constitution: Why I Chose Pragmatism, not TextualismFrom EverandReading the Constitution: Why I Chose Pragmatism, not TextualismNo ratings yet

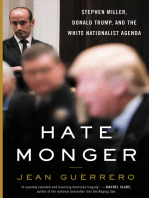

- Hatemonger: Stephen Miller, Donald Trump, and the White Nationalist AgendaFrom EverandHatemonger: Stephen Miller, Donald Trump, and the White Nationalist AgendaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- The Deep State: How an Army of Bureaucrats Protected Barack Obama and Is Working to Destroy the Trump AgendaFrom EverandThe Deep State: How an Army of Bureaucrats Protected Barack Obama and Is Working to Destroy the Trump AgendaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- The Last Republicans: Inside the Extraordinary Relationship Between George H.W. Bush and George W. BushFrom EverandThe Last Republicans: Inside the Extraordinary Relationship Between George H.W. Bush and George W. BushRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)