Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chuse Ethnomusicology 2017

Uploaded by

MonyesmaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chuse Ethnomusicology 2017

Uploaded by

MonyesmaCopyright:

Available Formats

Review

Reviewed Work(s): Fado Resounding: Affective Politics and Urban Life by Lila Ellen

Gray

Review by: Loren Chuse

Source: Ethnomusicology , Vol. 61, No. 2 (Summer 2017), pp. 333-336

Published by: University of Illinois Press on behalf of Society for Ethnomusicology

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/ethnomusicology.61.2.0333

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

University of Illinois Press and Society for Ethnomusicology are collaborating with JSTOR to

digitize, preserve and extend access to Ethnomusicology

This content downloaded from

107.15.64.252 on Tue, 05 Sep 2023 19:31:35 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Vol. 61, No. 2 Ethnomusicology Summer 2017

Book Reviews

Fado Resounding: Affective Politics and Urban Life. Lila Ellen Gray. 2013.

Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 328 pp., photographs, figures, musical

transcriptions, references. Cloth, $89.95; paper, $24.95.

Lila Ellen Gray’s engaging and vivid study of fado performance fills a void

in the scholarly work on Portuguese fado. Few English-language ethnographic

studies of fado have been done, so her recent work stands out as an especially

valuable and important contribution to the literature. It is further distinguished

by the depth of its analysis of the historical and social contexts of fado perfor-

mance. Based on her 2005 doctoral dissertation at Duke University, Gray’s work

is an anthropologically based study of the social life of the sung poetic genre of

fado. Gray’s ideas are presented in an immediate style that is rich in personal

vignettes and ethnographic data. Her work foregrounds knowledge embedded

and transmitted in the performing body and in musical sound, knowledge that

engages habits of memory along with improvisation. Fado Resounding will be

of interest to scholars across disciplines and musical genres, as it relates sound,

listening, and vocality to social life; aesthetic forms and genre to affect; music

to language; and performance to politics, memory, history, and a sense of place.

Gray did her field research among fado singers, instrumentalists, and cul-

tural brokers in the city of Lisbon from 2001 to 2003, spanning diverse and

overlapping sites and social worlds from professional fado performance venues

to small amateur bars, recording studios, museums, and archives. The author

portrays senses of place and history through investigating the affective labors

of musical forms and the intertwining of musical genre and emotion, keeping

in view Portugal’s position on Europe’s farthest southwestern border.

The author’s work is premised on a dynamic mode of genre and offers

social analysis through the prism of musical genre. Citing the work of Mikhail

Bakhtin (1986), Gray argues for genre as sociohistorically contingent and against

a notion of genre as formally fixed. She further asserts the power of genre in

rendering communicative and affective the implicit narratives that shape an

© 2017 by the Society for Ethnomusicology

This content downloaded from

107.15.64.252 on Tue, 05 Sep 2023 19:31:35 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

334 Ethnomusicology, Winter 2017

individual’s sense of self and place in the world. Fado style and talk engage with

a re-presentation of genre that is hybrid, gendered, and raced.

Gray takes the charged polemic about fado’s origins as one point of departure

for theorizing relationships between musical ideas and the shaping of ideas about

history, belonging, and locality. She posits an “anthropology of the senses” and

asks how musical experience might accumulate history in ways different from

other expressive forms, and she examines the relationship between sound, listen-

ing, and vocality to social life and a sense of belonging and place (4–6). Query-

ing how we make emotional sense of sound, the author presents a framework

of fado sound as shaped both socially and physiologically in her discussion of

musical significations that are at once as sensuous and embodied as they are felt

and heard. She draws on approaches to musical signification in sociolinguistic

anthropology that argue for music and language as coconstitutive domains of

meaning (Feld and Fox 1994).

Fado developed in Lisbon in the early 1880s as a sung poetic gesture voiced

from the city’s socioeconomic margins with original narratives linked to prostitu-

tion, criminality, and colonial expansion. Later embraced by the upper classes,

fado rose to the status of national symbol and played a role during the Estado

Novo, the Salazar dictatorship in power from 1924 to 1976, in sanitized versions

developed through censorship and professionalization. Themes that emerge

in Gray’s examination of this trajectory have parallels in a number of popular

contemporary genres.

Saudade, the evoking of memory and history, is one of fado’s most pervasive

tropes. Gray analyzes how saudade is achieved through vocal and instrumental

stylings, as well as through choice of lyrics, which are of primary importance in

fado. Gray chose to focus on performance practice in amateur venues, which

offered abundant opportunity to observe performers and audiences whose ways

of listening shape the learning of style and meaning. One neighborhood venue,

O Jaime, provides a place of dense sociality centered on music making and listen-

ing, a place that functions implicitly as a “school for performance,” according to

Gray (30). She describes in detail the performances, the singers, the audience’s

reactions and participation, and the physical and emotional space of the Sat-

urday afternoon fado sessions. Vocal qualities associated with shifts in register,

dynamics heightened by use of rubato, and extended melismatic ornamentation

all signal moments of heightened emotion, as does the affectively charged use

of silence. Fadistas (fado singers) also express emotion with downward glis-

sandi and with lyrics that speak of tears. These tears index, according to Gray,

both a private emotional and an aesthetic experience and a moment of shared

sociability.

How fado is learned and the discourse that surrounds learning, what Gray

calls “the pedagogies of the soulful in sound,” are central to her arguments about

This content downloaded from

107.15.64.252 on Tue, 05 Sep 2023 19:31:35 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Book Reviews 335

saudade and about the social construction of genre. She describes in detail her

own experience of singing lessons, a process that involved learning lyrics, styl-

ings, and arrangements from recordings. She also notes the intergenerational

participation, the encouragement of children to imitate the affect, and the pos-

tures and vocal stylings of adults. One of the primary tropes she encountered

in her research was a nostalgia for the past, the idea especially among older

singers that older fado was more “soulful.” The majority of fadistas she encoun-

tered expressed antagonism toward the recently created institutions focused on

teaching and learning fado. One frequent trope is that one does not learn to be

a fadista; rather, one is born a fadista, it is in the blood. Yet in contrast to this

prevailing trope, Gray stresses the extent to which emerging fadistas, herself

included, are encouraged to learn from recordings. The discourse on ways of

learning and responses to the institutionalism of learning echoes a number of

genres, such as flamenco and rebetiko, in which highly charged discourses sur-

rounding issues of authenticity and “purity” are frequent.

Turning to gender politics associated with this genre, Gray notes how men

and women move differently through fado worlds. These routes tend to dictate

the boundaries of possibility in terms of how one performs and is received. She

situates her analysis within constructs of deeply gendered forms of knowledge

and ideologies of gendered affect that characterize fado. In contrast to male

musicians who frame fado as the instrumentalists, theorists, and poets of the

genre, female fadistas are rendered symbolically as suffering, tearful, and sacri-

ficial while conversely as overly sexualized in tropes of the femme fatale. Gray’s

insights, drawing on Lauren Berlant’s (2008) examination of sentimentality asso-

ciated with the female, will be of broad interest to scholars on music and gender.

Gray’s chapter on the life and work of a famous fado diva, the late Amalia

Rodrigues, emphasizes the extraordinary power of the voice of a celebrity for

shaping not only the genre but also public feeling. Gray analyzes the poet-

ics of public biography and fan discourse in her discussion of the enormous

importance of Amalia to the shaping of fado as genre. She examines the dia-

lectics between the genre of celebrity and fado as genre and goes on to theorize

more generally about audiences and the commercial mediation of genre and

of singing musical superstars. Gray outlines Rodrigues’s role in standardizing

the commercial forms of fado and becoming the “voice of the national patri-

mony” (183). Rodrigues, who is described as having a “throat of silver,” became

a larger-than-life iconic representation of fado and of Portugal both nationally

and internationally.

Overall, Fado Resounding provides an evocative and detailed ethnographic

portrait of a contemporary musical genre as it exists within its socially and his-

torically constructed context. It is a fascinating study, well grounded in gender

and performance theory, that makes a valuable contribution to the field.

This content downloaded from

107.15.64.252 on Tue, 05 Sep 2023 19:31:35 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

336 Ethnomusicology, Winter 2017

References

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. 1986. “The Problem of Speech Genres.” In Speech, Genre and Other Late Essays,

edited by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist, 60–102. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Berlant, Lauren. 2008. The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American

Culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Feld, Steven, and Aaron A. Fox. 1994. “Music and Language.” Annual Review of Anthropology

23:25–53.

Loren Chuse Independent Scholar

Hip Hop Ukraine: Music, Race, and African Migration. Adriana N. Helbig.

2014. Ethnomusicology Multimedia Series. Bloomington: Indiana Uni-

versity Press. xix, 233 pp., photographs, notes, bibliography, index, guide

to online media examples. Cloth, $70.00; paper, $28.00; e-book, $21.99.

In Hip Hop Ukraine, Adriana Helbig argues that local uses of hip hop enable

changing perceptions of the continuous migration of students from the Afri-

can continent. While she focuses on Ukraine and, by extension, postsocialist

Eastern Europe, Helbig offers a conceptualization of practitioners’ emotional,

philosophical, and musical connections to US hip hop useful to scholars wher-

ever sweeping economic change is lived through race and racialization. Over

the book’s final three chapters, in particular, she shows that both African and

non-African Ukrainian practitioners make analogies between various kinds of

difference, using the indelible linking of hip hop with otherness as a framework

for their own negotiations of racial, ethnic, linguistic, and economic conflict.

For those who recognize their own homes in US hip hop videos’ tropes of

inner-city poverty, neglect, and decay, racialized images and the sounds that

accompany them become a way to simultaneously draw attention to rising eco-

nomic inequality and to assert one’s cultural capital, regardless of income (123).

In order to do the latter, Ukrainian hip hop artists and listeners encode their

interpretations of African American hip hop onto African bodies: “At hip hop

dance parties . . . , a person of African heritage—almost always male—is typi-

cally invited to dance on stage. . . . His dancing validates the skills of the DJ but

concurrently places the black body on display” (134). Helbig’s (2005) dissertation,

on a leading Roma rights NGO in Ukraine and the pervasive depiction of Roma

as naturally talented musicians, positions her well to discuss self-essentializing

strategies deployed by marginalized individuals and groups. In the book’s most

nuanced and compelling analyses, African musicians use the racializations within

which they are inscribed to argue for their own acceptance as “new Ukrainians,”

even as their very ability to integrate is widely questioned (155).

This content downloaded from

107.15.64.252 on Tue, 05 Sep 2023 19:31:35 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Contact Languages and MusicFrom EverandContact Languages and MusicAndrea HollingtonNo ratings yet

- Women's Songs from West AfricaFrom EverandWomen's Songs from West AfricaThomas A. HaleNo ratings yet

- Musical Semiotics As A ToolDocument33 pagesMusical Semiotics As A ToolAngel LemusNo ratings yet

- Stance: Ideas about Emotion, Style, and Meaning for the Study of Expressive CultureFrom EverandStance: Ideas about Emotion, Style, and Meaning for the Study of Expressive CultureRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- OralitateDocument18 pagesOralitateBlanaru Tofanel Oana CristinaNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument23 pagesPDFerbariumNo ratings yet

- Music's Role in Language Revitalization-Some Questions From Recent LiteratureDocument10 pagesMusic's Role in Language Revitalization-Some Questions From Recent LiteratureFabiana LeiteNo ratings yet

- Soul Talk, Song Language: Conversations with Joy HarjoFrom EverandSoul Talk, Song Language: Conversations with Joy HarjoRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Musical Semiotics As A Tool For The Social Study of MusicDocument33 pagesMusical Semiotics As A Tool For The Social Study of MusicTyler CoffmanNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Zen and the Art of Poetry: Jane Hirshfield and Joy HarjoFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Zen and the Art of Poetry: Jane Hirshfield and Joy HarjoNo ratings yet

- Ingrid MonsonDocument36 pagesIngrid MonsonBruno AndradeNo ratings yet

- Adriana Fernandes - Forro The Constitution of A Genre in PerformanceDocument20 pagesAdriana Fernandes - Forro The Constitution of A Genre in PerformanceDinis ZanottoNo ratings yet

- Music Gender Education by Lucy Green Cambridge CamDocument5 pagesMusic Gender Education by Lucy Green Cambridge CamYan SampaioNo ratings yet

- 04-2 4 PDFDocument14 pages04-2 4 PDFBella FransischaNo ratings yet

- More Than Men in Drag - Gender, Sexuality, and TheDocument109 pagesMore Than Men in Drag - Gender, Sexuality, and ThePhelipe MoraesNo ratings yet

- A Critique of Current Research On Music and GenderDocument10 pagesA Critique of Current Research On Music and GenderFatou SourangNo ratings yet

- Oakes 2013 TheOneWhoListens MeaningTimeMomentarySubjectivityMusicDocument30 pagesOakes 2013 TheOneWhoListens MeaningTimeMomentarySubjectivityMusicJesus MauryNo ratings yet

- Widdes - Music Meaning and CultureDocument8 pagesWiddes - Music Meaning and CultureUserMotMooNo ratings yet

- The Processes and Results of Musical Culture Contact: A Discussion of Terminology and ConceptsDocument24 pagesThe Processes and Results of Musical Culture Contact: A Discussion of Terminology and ConceptsErickinson BezerraNo ratings yet

- Introduction On Difference Representati PDFDocument30 pagesIntroduction On Difference Representati PDFBharath Ranganathan0% (1)

- (Final) CAS 280 - CHARACTERIZING HIGAONON ETHNOMUSICDocument14 pages(Final) CAS 280 - CHARACTERIZING HIGAONON ETHNOMUSICJane Limsan PaglinawanNo ratings yet

- Linguistics As An Approach For MusicologyDocument7 pagesLinguistics As An Approach For Musicologymelitenes100% (1)

- Durrant & Hemonides 1998 - What Makes People Sing TogetherDocument11 pagesDurrant & Hemonides 1998 - What Makes People Sing TogetherLucas TossNo ratings yet

- University of Illinois Press Society For EthnomusicologyDocument24 pagesUniversity of Illinois Press Society For EthnomusicologyPaula MartinsNo ratings yet

- Stylisticanalysysi of Fela KutiDocument18 pagesStylisticanalysysi of Fela KutiXucuru Do Vento100% (1)

- 10 1 1 463 6298 PDFDocument17 pages10 1 1 463 6298 PDFIago VilanovaNo ratings yet

- Stobart Música BoliviaDocument29 pagesStobart Música BoliviaEsteban González SeguelNo ratings yet

- Thesis Defense - HIGAONON CHANTS AND MUSICDocument16 pagesThesis Defense - HIGAONON CHANTS AND MUSICJane Limsan Paglinawan100% (1)

- The Feminist Critique of Language ApproachDocument1 pageThe Feminist Critique of Language ApproachIstiaque Hossain LabeebNo ratings yet

- The "Finite" Art of Improvisation: Pedagogy and Power in Jazz EducationDocument15 pagesThe "Finite" Art of Improvisation: Pedagogy and Power in Jazz EducationRicardo LaudaresNo ratings yet

- The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Music and Culture: Participant ObservationDocument5 pagesThe SAGE International Encyclopedia of Music and Culture: Participant ObservationTheus LineusNo ratings yet

- Research Project Final DraftDocument17 pagesResearch Project Final Draftapi-662034787No ratings yet

- Assessment 3 EssayDocument4 pagesAssessment 3 EssayDominic ErbacherNo ratings yet

- METODO 1 Strugaru Stefan-Ionut en-SPDocument7 pagesMETODO 1 Strugaru Stefan-Ionut en-SPIonuț StrugaruNo ratings yet

- De Carvalho y Segato-Sistemas Abertos e Territórios Fechados, para Uma Nova Comprensao Das Interfaces Entre Música e Identidades SociaisDocument23 pagesDe Carvalho y Segato-Sistemas Abertos e Territórios Fechados, para Uma Nova Comprensao Das Interfaces Entre Música e Identidades SociaisMateo Armando MeloNo ratings yet

- "The "Finite" Art of Impr... Tiques en Improvisation"Document12 pages"The "Finite" Art of Impr... Tiques en Improvisation"Rui LeiteNo ratings yet

- Why Suya Sing A Musical Anthropology of PDFDocument3 pagesWhy Suya Sing A Musical Anthropology of PDFAndréNo ratings yet

- Living Genres in Late Modernity: American Music of the Long 1970sFrom EverandLiving Genres in Late Modernity: American Music of the Long 1970sNo ratings yet

- Radicalism and Music: An Introduction to the Music Cultures of al-Qa’ida, Racist Skinheads, Christian-Affiliated Radicals, and Eco-Animal Rights MilitantsFrom EverandRadicalism and Music: An Introduction to the Music Cultures of al-Qa’ida, Racist Skinheads, Christian-Affiliated Radicals, and Eco-Animal Rights MilitantsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (1)

- Ventriloquism EssayDocument3 pagesVentriloquism EssayTobyStanfordNo ratings yet

- Critical Review of Two Musical EthnographiesDocument6 pagesCritical Review of Two Musical EthnographiesCallum JonesNo ratings yet

- Introductory Notes To The Semiotics of Music: This Document (1999) Is Out of Date. MUSIC'S MEANINGS' (2012)Document49 pagesIntroductory Notes To The Semiotics of Music: This Document (1999) Is Out of Date. MUSIC'S MEANINGS' (2012)diogoalmeidarib1561100% (1)

- Metodo #1Document7 pagesMetodo #1Ionuț StrugaruNo ratings yet

- 01 Gerhard Kubik-Analogies and Differences in African-American Musical Cultures Across The Hemisphere (1998)Document28 pages01 Gerhard Kubik-Analogies and Differences in African-American Musical Cultures Across The Hemisphere (1998)CamilaNo ratings yet

- Araujo ViolenceDocument28 pagesAraujo ViolencerachelreadingNo ratings yet

- Socsci 08 00305 PDFDocument21 pagesSocsci 08 00305 PDFMarissa PascualNo ratings yet

- MOEHN, Frederick. Music, Mixing and Modernity in Rio de JaneiroDocument39 pagesMOEHN, Frederick. Music, Mixing and Modernity in Rio de JaneiroHéctor BravoNo ratings yet

- Semiotics of MusicDocument47 pagesSemiotics of MusicJuan David Bermúdez100% (1)

- Native HermeneuticsDocument33 pagesNative HermeneuticsFRAGANo ratings yet

- Faces of Tradition in Chinese Performing ArtsFrom EverandFaces of Tradition in Chinese Performing ArtsLevi S. GibbsNo ratings yet

- Aspects of Bulgarian Musical ThoughtDocument25 pagesAspects of Bulgarian Musical ThoughtAndrés CortésNo ratings yet

- Beyond The CanonDocument232 pagesBeyond The CanonMonyesmaNo ratings yet

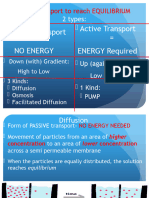

- Cell TransportsDocument22 pagesCell TransportsMonyesmaNo ratings yet

- Wingell Herzog Chapters 1&2Document32 pagesWingell Herzog Chapters 1&2MonyesmaNo ratings yet

- Rogers Bottge Haefeli IntroDocument5 pagesRogers Bottge Haefeli IntroMonyesmaNo ratings yet

- Wingell Chapter 1Document5 pagesWingell Chapter 1MonyesmaNo ratings yet

- 2003 Convention Basic Texts - 2022 version-ENDocument190 pages2003 Convention Basic Texts - 2022 version-ENMonyesmaNo ratings yet

- 33 Best Tips To Be More Happy - Happiness Can Be Learned!Document19 pages33 Best Tips To Be More Happy - Happiness Can Be Learned!MonyesmaNo ratings yet

- IPA Handbook ReviewDocument1 pageIPA Handbook ReviewMonyesmaNo ratings yet

- LOUGHRAN PedagogyMakingSense 2013Document25 pagesLOUGHRAN PedagogyMakingSense 2013MonyesmaNo ratings yet

- Intro To Operatic RulesDocument22 pagesIntro To Operatic RulesMonyesmaNo ratings yet

- A History of Singing - UnlockedDocument360 pagesA History of Singing - UnlockedMonyesmaNo ratings yet

- CasteloBranco InSearchLost 1988Document36 pagesCasteloBranco InSearchLost 1988MonyesmaNo ratings yet

- Portuguese AmericanDocument2 pagesPortuguese AmericanMonyesmaNo ratings yet

- Sperry-VocalVersatilityBel-2014 ESTRUCTURA+++Document6 pagesSperry-VocalVersatilityBel-2014 ESTRUCTURA+++MonyesmaNo ratings yet

- Cruz SuspendedVoiceAmlia 2013Document21 pagesCruz SuspendedVoiceAmlia 2013MonyesmaNo ratings yet

- Fado Historiograhy - Old Myths and New FrontiersDocument18 pagesFado Historiograhy - Old Myths and New FrontiersMonyesmaNo ratings yet

- Liederabend - The Soul of The LiliesDocument2 pagesLiederabend - The Soul of The LiliesMonyesmaNo ratings yet

- COLVIN FadoHistriaduma 2016Document21 pagesCOLVIN FadoHistriaduma 2016MonyesmaNo ratings yet

- 1 La Estructura Narrativa ClásicaDocument4 pages1 La Estructura Narrativa ClásicaMonyesmaNo ratings yet

- Midlife Crisis - Signs, Causes, and Coping TipsDocument13 pagesMidlife Crisis - Signs, Causes, and Coping TipsMonyesmaNo ratings yet

- Dolce Amor - CavalliDocument4 pagesDolce Amor - CavalliMonyesmaNo ratings yet

- Harry Potter: and The Philosopher's StoneDocument34 pagesHarry Potter: and The Philosopher's StoneJewel EspirituNo ratings yet

- A Saga in Stone Srimate Srivan Satakopa Sri Vedanta Desika Yatindra Mahadesikaya NamaDocument4 pagesA Saga in Stone Srimate Srivan Satakopa Sri Vedanta Desika Yatindra Mahadesikaya NamaPaulo FernandesNo ratings yet

- Greek Mythology CharactersDocument5 pagesGreek Mythology CharactersJhe VictorioNo ratings yet

- Homer pp.3-18Document17 pagesHomer pp.3-18Bobojon AbdulloevNo ratings yet

- 1 21stCL-Q1-W5 With CoverDocument23 pages1 21stCL-Q1-W5 With CoverVictoria De Los SantosNo ratings yet

- Mahabharata PDFDocument720 pagesMahabharata PDFSuchismita Sen69% (16)

- Romancing The Stone: History-Writing and RhetoricDocument16 pagesRomancing The Stone: History-Writing and RhetoricDavid HotstoneNo ratings yet

- 4zeta PDPR2.0Document72 pages4zeta PDPR2.0Mohammad FalakhuddinNo ratings yet

- 2020 Biography Writing Syllabus - UpdatedDocument9 pages2020 Biography Writing Syllabus - UpdatedSharon FanNo ratings yet

- Obw A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthurs CourtDocument8 pagesObw A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthurs CourtrasimahuseynliNo ratings yet

- STYLISTICS AND DISCOURSE ANALYSIS Module 2&3Document20 pagesSTYLISTICS AND DISCOURSE ANALYSIS Module 2&3Niño Jubilee E. DaleonNo ratings yet

- Great Expectations A Manifestation of Gothicism and RomanticismDocument6 pagesGreat Expectations A Manifestation of Gothicism and RomanticismEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of Sharon Olds' The PromiseDocument5 pagesA Critical Analysis of Sharon Olds' The PromisePrevoditeljski studijNo ratings yet

- Open WWW Thebellacademy Com Uploads 2 6 5-6-26569366 the-boy-In-The-striped-pajamas PDFDocument112 pagesOpen WWW Thebellacademy Com Uploads 2 6 5-6-26569366 the-boy-In-The-striped-pajamas PDFpyasNo ratings yet

- Therockcreekreview 2022Document83 pagesTherockcreekreview 2022api-657902882No ratings yet

- Overview of Myths in EnglandDocument2 pagesOverview of Myths in EnglandcrrissttiNo ratings yet

- Strange Connection of "Gandharva with Soma and Suryaa (सूर्या) "Document18 pagesStrange Connection of "Gandharva with Soma and Suryaa (सूर्या) "VR PatilNo ratings yet

- Duke University PressDocument16 pagesDuke University PressedilvanmoraesNo ratings yet

- Literacy Narrative Draft OutlineDocument3 pagesLiteracy Narrative Draft Outlineapi-240194692No ratings yet

- Creative Writing Course OutlineDocument2 pagesCreative Writing Course OutlineMarie Joy GarmingNo ratings yet

- Machi No Dorufin - BassDocument2 pagesMachi No Dorufin - BassRobin SveginNo ratings yet

- POWERSYSTEMANALYSISDocument16 pagesPOWERSYSTEMANALYSISGmadhusudhan MadhuNo ratings yet

- Noli Me Tangere and El FilibusterismoDocument9 pagesNoli Me Tangere and El FilibusterismoMariter PidoNo ratings yet

- Πότνια Αὔως, The Greek Dawn-Goddess and Her Antecedent - Peter JacksonDocument9 pagesΠότνια Αὔως, The Greek Dawn-Goddess and Her Antecedent - Peter JacksonLeombruno BlueNo ratings yet

- Charlotte Bronte-Jane EyreDocument7 pagesCharlotte Bronte-Jane EyreYen Nhi Le DuongNo ratings yet

- An Overview of American Literature PDFDocument11 pagesAn Overview of American Literature PDFShreya NayakNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Map: English 7 Philippine Literature During The JapaneseDocument2 pagesCurriculum Map: English 7 Philippine Literature During The JapaneseJeff LacasandileNo ratings yet

- Uncle Gordon EnglishDocument11 pagesUncle Gordon EnglishJohn Viondi MendozaNo ratings yet

- Allyson Booth (Auth.) - Reading The Waste Land From The Bottom Up-Palgrave Macmillan US (2015)Document256 pagesAllyson Booth (Auth.) - Reading The Waste Land From The Bottom Up-Palgrave Macmillan US (2015)Makai Péter KristófNo ratings yet

- R& J Renaissance Lit UbD Unit Template DRAFTDocument3 pagesR& J Renaissance Lit UbD Unit Template DRAFTmragostino10536No ratings yet