Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Evaluating The Quality of Community Care For Atten

Uploaded by

aviones123Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Evaluating The Quality of Community Care For Atten

Uploaded by

aviones123Copyright:

Available Formats

EDITORIAL

Evaluating the Quality of Community Care

for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Mark Olfson, M.D., M.P.H.

R

ational reform of the mental health system Neither setting appeared to offer an acceptable

resembles good clinical care in that it starts level of care.

with a careful assessment and an accurate The reasons for the low level of stimulant

diagnosis. Although it has been known for many treatment, which was especially evident in spe-

years that the treatment of attention-deficit/hy- cialty mental health clinics, remain unclear. As

peractivity disorder (ADHD) is often shallow the authors suggest, it is possible that non-

and uneven, the portrait of community care that medically trained mental health professionals may

emerges from the study by Zima et al.1 in this determine that most children with ADHD do not

issue of the Journal is considerably more detailed warrant a medication evaluation. Inadequate

and stark than previous assessments. In an ele- clinical assessments, knowledge deficits concern-

gant set of longitudinal analyses drawn from ing the safety and efficacy of stimulants for

Medicaid service and pharmacy claims data, ADHD, pressures to meet administrative case-

parent interviews, and school records, the inves- load expectations, and concerns over parent re-

tigators characterize the mental health care and sponses to a referral for medication evaluation

clinical course of children with ADHD in a may further impede appropriate referrals. A

managed-care Medicaid program. The results scarcity of child and adolescent psychiatrists,

reveal a failure to allocate specialty services to especially in settings that serve Medicaid popu-

those in greatest clinical need, widespread defi- lations, may also constrain referrals for medica-

ciencies in pharmacologic treatment, high rates tion management.2

of treatment disengagement, and unacceptably Parent preferences may also contribute to low

poor clinical and academic outcomes. Perhaps rates of stimulant treatment. Most Americans are

the only bright spot in this otherwise unrelent- not well informed about ADHD and its treat-

ingly bleak report is the remarkably favorable ment. Although a majority support a combina-

parent perceptions of treatment. Even here, it tion of counseling and medication, many more

might be argued that favorable parent views of support counseling alone than medication

treatment could slow consumer-driven efforts alone.3 More specifically, parents of children di-

to push for sorely needed mental health care agnosed with ADHD are often initially hesitant

reform to improve the quality of care. to have their child started on stimulants4 and

The new report offers a window into funda- usually report that the diagnosis and treatment

mental differences between the nature of ADHD stigmatizes and socially isolates their child.5 In the

care provided in primary care and specialty African-

mental health care within a large Medicaid managed- American community, there appears to be partic-

care program. Although all children in specialty ularly high levels of skepticism and mistrust

mental health clinics received at least some about psychotropic medications for child mental

psychosocial treatment and only a minority health problems.6 Clinicians should be taught to

filled stimulant prescriptions, children treated approach this delicate and important topic in a

in primary care were far more likely to receive flexible and open-minded manner that commu-

stimulants than psychosocial treatment. Even nicates to parents and their children that their

in primary care, however, the rate and persis- doubts and concerns are heard and respected.

tence of stimulant treatment fell far below The physician who recommends starting stimu-

national monitoring and treatment standards. lants for ADHD should recognize that his or her

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CHILD & ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY

VOLUME 49 NUMBER 12 DECEMBER 2010 www.jaacap.org 1183

OLFSON

views will likely be weighed against prevailing and tensions over professional roles may impede

cultural norms and the influence of friends, the flow of more severely ill children into spe-

teachers, and the popular media. cialty care. Despite widespread agreement that

In children who received stimulants, Zima et pediatricians should play a key role in identify-

al.1 found that medication trials were often quite ing ADHD, pediatricians and child and adoles-

brief. Although it is not possible to determine the cent psychiatrists hold sharply different views

intended duration of treatment, it is likely that regarding referral and treatment. Although child

stimulant treatment nonadherence was common. and adolescent psychiatrists tend to believe pe-

Widespread early treatment termination under- diatricians should refer rather than treat children

scores the central importance of developing clin- with ADHD, most pediatricians view themselves

ical strategies to enhance treatment continuity. as capable of treating ADHD.10 A shared under-

Parent and child knowledge and beliefs about the standing of the respective roles of each profes-

need for ongoing stimulant treatment likely sional group might provide a stronger founda-

play key roles in treatment acceptance. Con- tion for improved communication, collaboration,

certed efforts to implement guideline-based and patient allocation between primary and spe-

medication algorithms for ADHD have demon- cialty care.

strated some success. In one implementation of Few children in the study by Zima and col-

a medication algorithm for ADHD within pub- leagues1 received primary care and specialty

lic community mental health centers, psychia- mental health treatment. Colocation of primary

trists were successful in implementing major care physicians and mental health professionals

aspects of the algorithm and decreasing polyp- within the same building may increase profes-

harmacy, although some parents declined stim- sional interaction and opportunities for coman-

ulant dose titration once they observed im- agement. Improving access to specialty mental

provement in their child’s behavior with an health services within pediatric primary care,

initial stimulant dose.7 however, may require relatively complex system

In recent years, substantial progress has been level restructuring and identification of funding

made in developing the evidence base for behav- streams to support shared care.

ioral parent training, behavior contingency man- The report by Zima and colleagues1 adds

agement, and behavioral peer interventions for renewed urgency to the call for reform of

child and adolescent ADHD.8 A limitation of the Medicaid-financed community care of children with

study by Zima et al.1 is their inability to specify ADHD. Closer clinical monitoring with more

the content of psychosocial treatments received frequent follow-up contact may be needed to

by the children in their study. Regrettably, increase continuity of care. Improvements are

most social work and clinical psychology train- also needed in medication management, espe-

ing programs do not require training in any cially in specialty mental health clinics. Greater

evidence-based psychotherapies9 and efforts to dis- attention should also be devoted to assessment

seminate behavioral interventions for ADHD are and referral procedures to ensure that children

inchoate. Without a strong foundation in the with the most complex clinical needs receive

clinical skills necessary to deliver evidence- specialty care. Sustained progress in each of these

based interventions, initiatives to improve the key areas will likely require interventions at the

quality of psychosocial treatment for ADHD patient, parent, clinician, and system levels.

are likely to falter and the option of an evidence- The next few years will bring substantial change

based alternative to medications will remain un- to Medicaid-financed mental health services. After

common. enactment of the Patient Protection and Affordable

The clinical severity of children treated in Care Act of 2010, Medicaid benefits will be ex-

primary care clinics in the study by Zima and tended to large numbers of previously uninsured

colleagues1 closely resembled those seen in spe- individuals. During this transitional period, al-

cialty mental health clinics. A more efficient ready strained community services and resources

allocation would redistribute more severely ill will be further stretched. In this challenging envi-

children to specialty settings. Several factors in- ronment, it will be critically important to maintain

cluding a dearth of locally available specialized focus on the quality of care provided to children

services, stigmatization of specialty mental and adolescents in the Medicaid program who

health care, inadequate coordination of referrals, have ADHD. &

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CHILD & ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY

1184 www.jaacap.org VOLUME 49 NUMBER 12 DECEMBER 2010

EDITORIAL

Accepted September 1, 2010. Correspondence to Mark Olfson, M.D., M.P.H., New York State

Psychiatric Institute/Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians

Dr. Olfson is with the New York State Psychiatric Institute and the

and Surgeons of Columbia University, 1051 Riverside Drive, New

College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University.

York, NY 10032; e-mail: mo49@columbia.edu

Work on this editorial was supported by award U18-HS016097 from

the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Center for Education

and Research on Mental Health Therapeutics). 0890-8567/$36.00/©2010 American Academy of Child and

Adolescent Psychiatry

Disclosure: Dr. Olfson has received research grants to Columbia

University from Eli Lilly and Company and Bristol-Myers Squibb. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.09.005

REFERENCES

1. Zima BT, Bussing R, Lingqu T, et al. Quality of care for childhood American and Hispanic parent attitudes. Med Care. 2007;45:

attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a managed care Medicaid 1076-1082.

program. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:1225-1237. 7. Pliszka SR, Lopez M, Crismon ML, et al. Feasibility study of the

2. Kim WJ. Child and adolescent psychiatry workforce: a critical Children’s Medication Algorithm Project (CMAP) algorithm for

shortage and national challenge. Acad Psychiatry. 2003;27:277-282. the treatment of ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

3. McLeod JD, Fettes DL, Jensen PS, et al. Public knowledge, beliefs, 2003;42:279-287.

and treatment preferences concerning attention-deficit hyperac- 8. Weissman MM, Verdili H, Gameroff MJ, et al. National survey of

tivity disorder. Psych Serv. 2007;58:626-631. psychotherapy training in psychiatry, psychology, and social

4. dosRies S, Butz A, Lipkin PH, et al. Attitudes about stimulant work. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:925-934.

medication for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among 9. Pelham WE, Fabiano GA. Evidence-based psychosocial treatment

African American families in an inner city community. J Behav for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an update. J Clin

Health Serv Res. 2006;33:423-443. Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37:185-214.

5. dosReis S, Barksdale Cl, Sherman A, Maloney K, Charach A. 10. Henegan A, Garner AS, Storfer-Isser A, Kortepeter K, Stein REK,

Stigmatizing experiences of parents of children with a new Horwitz SM. Pediatricians’ role in providing mental health care

diagnosis of ADHD. Psych Serv. 2010;61:811-816. for children and adolescents: do pediatricians and child and

6. Brown JD, Wissow LS, Zachary C, Cook BL. Receiving advice adolescent psychiatrists agree? J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29:262-

about child mental health from a primary care provider: African 269.

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CHILD & ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY

VOLUME 49 NUMBER 12 DECEMBER 2010 www.jaacap.org 1185

You might also like

- The ADHD Handbook for Schools: Effective Strategies for Identifying and Teaching Students with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity DisorderFrom EverandThe ADHD Handbook for Schools: Effective Strategies for Identifying and Teaching Students with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity DisorderRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Therapist's Guide to Pediatric Affect and Behavior RegulationFrom EverandTherapist's Guide to Pediatric Affect and Behavior RegulationNo ratings yet

- Adhd DissertationDocument6 pagesAdhd DissertationBuyLiteratureReviewPaperSingapore100% (1)

- Currentstatusof Cognitivebehavioral Therapyforadult Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity DisorderDocument13 pagesCurrentstatusof Cognitivebehavioral Therapyforadult Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disordershofa nur rahmannisaNo ratings yet

- Current Status of ADHD in The United StatesDocument3 pagesCurrent Status of ADHD in The United StatesIan Mizzel A. DulfinaNo ratings yet

- The Efficacy, Safety, and Practicality of Treatments For Adolescents With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)Document26 pagesThe Efficacy, Safety, and Practicality of Treatments For Adolescents With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)Daniela GuedesNo ratings yet

- Psychoeducation PsychpsisDocument12 pagesPsychoeducation PsychpsisRoxanaNo ratings yet

- Treatment Planning AdhdDocument12 pagesTreatment Planning AdhdLuja2009No ratings yet

- Algoritmo TX Multimodal TDAH Latin SM 2009Document14 pagesAlgoritmo TX Multimodal TDAH Latin SM 2009azul0609No ratings yet

- Adhd and Ritalin PaperDocument18 pagesAdhd and Ritalin Paperapi-258330934No ratings yet

- American Academy of Pediatrics: Disorders, Fourth Edition Criteria 3) The Assessment ofDocument13 pagesAmerican Academy of Pediatrics: Disorders, Fourth Edition Criteria 3) The Assessment ofMatNo ratings yet

- ADHD: Is Objective Diagnosis Possible?: (Review)Document10 pagesADHD: Is Objective Diagnosis Possible?: (Review)Io SalmonsNo ratings yet

- ADHD Factsheet CliniciansDocument3 pagesADHD Factsheet CliniciansLeanneRaffaele GNo ratings yet

- Antshel2015 PDFDocument19 pagesAntshel2015 PDFCristinaNo ratings yet

- Psychopharmacology and Preschoolers A Critical ReviewDocument19 pagesPsychopharmacology and Preschoolers A Critical ReviewOctavio GarciaNo ratings yet

- Adhd Term Paper TopicsDocument8 pagesAdhd Term Paper TopicsWriteMyPaperApaFormatUK100% (1)

- Updated ADHD Guideline Addresses Evaluation, Diagnosis, Treatment From Ages 4-18Document2 pagesUpdated ADHD Guideline Addresses Evaluation, Diagnosis, Treatment From Ages 4-18CristinaNo ratings yet

- First Draft of A CommentaryDocument4 pagesFirst Draft of A CommentaryPablo VaNo ratings yet

- Adhd Clin Fin To PostDocument4 pagesAdhd Clin Fin To PostSamkazNo ratings yet

- ADHD For AdultsDocument11 pagesADHD For AdultsManuel Pastene100% (2)

- Case Summary Module 7 NUR520Document3 pagesCase Summary Module 7 NUR52078xh8x8b69No ratings yet

- Mental Health Competencies ForDocument18 pagesMental Health Competencies ForVeronica Romero MouthonNo ratings yet

- Functional Consequences of Attention-De Ficit Hyperactivity Disorder On Children and Their FamiliesDocument15 pagesFunctional Consequences of Attention-De Ficit Hyperactivity Disorder On Children and Their FamiliesAlba VilaNo ratings yet

- Adhd PDFDocument10 pagesAdhd PDFKambaliNo ratings yet

- ADHD Estimulantes y Sus Efectos en La Talla en NiñosDocument2 pagesADHD Estimulantes y Sus Efectos en La Talla en NiñosferegodocNo ratings yet

- Barriers To Care: Hambatan StrukturalDocument5 pagesBarriers To Care: Hambatan StrukturalPuspa MaharaniNo ratings yet

- Psycho EducationDocument14 pagesPsycho EducationMaha LakshmiNo ratings yet

- AdhdDocument16 pagesAdhdCristina Badenas de CoaNo ratings yet

- Psychological Care of The FamiDocument16 pagesPsychological Care of The FamiZafar Imam KhanNo ratings yet

- American Academy of Pediatrics: Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) CriteriaDocument12 pagesAmerican Academy of Pediatrics: Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) CriteriaChichi Lubaton-SacroNo ratings yet

- Pauta Atencion Comunidad 2 N&ADocument29 pagesPauta Atencion Comunidad 2 N&APedro Y. LuyoNo ratings yet

- Post Partum DepressionDocument17 pagesPost Partum Depressionrisda aulia putriNo ratings yet

- TDAH AdolescentesDocument9 pagesTDAH AdolescentesKarla AbadoNo ratings yet

- Problem Research Paper Joshuarutledge10102020Document9 pagesProblem Research Paper Joshuarutledge10102020api-581236671No ratings yet

- AdhdDocument16 pagesAdhdMeanne Atienza-ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Assessment ChildadolDocument30 pagesAssessment ChildadolTanvi ManjrekarNo ratings yet

- A Different Approach To Rising Rates of ADHD DiagnosisDocument1 pageA Different Approach To Rising Rates of ADHD DiagnosisPaul AsturbiarisNo ratings yet

- Addressing Early Childhood Emotional and Behavioral ProblemsDocument13 pagesAddressing Early Childhood Emotional and Behavioral ProblemsAriNo ratings yet

- The Chronic Care Model and ADD-ADHDDocument6 pagesThe Chronic Care Model and ADD-ADHDRyan BNo ratings yet

- Rahul Shaik Kamala Kumari.P Syed Ahmed Basha: BackgroundDocument6 pagesRahul Shaik Kamala Kumari.P Syed Ahmed Basha: BackgroundMutiarahmiNo ratings yet

- UBH Outpatient Treatment Oppositional Defiant Disorder PDFDocument15 pagesUBH Outpatient Treatment Oppositional Defiant Disorder PDFBrian Harris100% (1)

- Introduction To Psychosocial Issues: A. Cheder, PH.DDocument6 pagesIntroduction To Psychosocial Issues: A. Cheder, PH.DErma NurmawatiNo ratings yet

- Case Report: Communication Strategies For Empowering and Protecting ChildrenDocument9 pagesCase Report: Communication Strategies For Empowering and Protecting ChildrennabilahNo ratings yet

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy For ADHD in Adolescents Clinical ConsiderationsDocument11 pagesCognitive-Behavioral Therapy For ADHD in Adolescents Clinical Considerationsdmsds100% (1)

- Goodman D2010 The Black Bookof ADHDDocument19 pagesGoodman D2010 The Black Bookof ADHDRadja Er GaniNo ratings yet

- ADHD: Clinical Practice Guideline For The Diagnosis, Evaluation, and TreatmentDocument18 pagesADHD: Clinical Practice Guideline For The Diagnosis, Evaluation, and TreatmentBen CulpepperNo ratings yet

- Medication Adherence Is A Partnership Medication Compliance Is NotDocument9 pagesMedication Adherence Is A Partnership Medication Compliance Is Notthedevilsoul981No ratings yet

- Consumer Centered Mental Health EducationDocument6 pagesConsumer Centered Mental Health EducationfinazkyaloNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Community Mental HealthDocument35 pagesPediatric Community Mental HealthShirleyNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Substance AbuseDocument9 pagesLiterature Review Substance Abuseaflshxeid100% (1)

- Adhd Update Research ProtocolDocument31 pagesAdhd Update Research ProtocolChristoph HockNo ratings yet

- Dia Care 2001 Delamater 1286 92Document7 pagesDia Care 2001 Delamater 1286 92Yousef KhalifaNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Counselling To Increase The Family of Soul Patients About Drug ComplianceDocument4 pagesEffectiveness of Counselling To Increase The Family of Soul Patients About Drug ComplianceMarlisa LionoNo ratings yet

- Adhd Criteria ChildDocument24 pagesAdhd Criteria Childhardyanti_syamNo ratings yet

- Final Evidence TableDocument21 pagesFinal Evidence Tableapi-293253519No ratings yet

- Clinical Assessment and Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in AdultsDocument15 pagesClinical Assessment and Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults733No ratings yet

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) : YesterdayDocument2 pagesAttention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) : YesterdayseamusoneNo ratings yet

- Behavior TherapyDocument35 pagesBehavior Therapynikos kasiktsisNo ratings yet

- Adhd PsychoeducationDocument4 pagesAdhd Psychoeducationapi-487140745100% (1)

- Attentiondeficithyperactivity Disorder in Adults Update On Clinical Presentation and Care NeuropsychiatryDocument20 pagesAttentiondeficithyperactivity Disorder in Adults Update On Clinical Presentation and Care NeuropsychiatryG Orange100% (1)

- La Otra Cara Del Amor Mitos, Paradojas y Problemas.Document6 pagesLa Otra Cara Del Amor Mitos, Paradojas y Problemas.Lu PsicoNo ratings yet

- Trauma PTSD Developing BrainDocument16 pagesTrauma PTSD Developing Brainaviones123No ratings yet

- Duffy2020 Article Pre-pubertalBipolarDisorderOriDocument10 pagesDuffy2020 Article Pre-pubertalBipolarDisorderOriMarius CosmaNo ratings yet

- 2 Mapas Sensoriales 18pDocument30 pages2 Mapas Sensoriales 18paviones123No ratings yet

- Controversies Concerning The Diagnosis and Treatment of Bipolar Disorder in ChildrenDocument14 pagesControversies Concerning The Diagnosis and Treatment of Bipolar Disorder in Childrenaviones123No ratings yet

- Turecki Suicide and Suicidal BehaviorDocument25 pagesTurecki Suicide and Suicidal Behavioraviones123No ratings yet

- Stahl S Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical ApplicationsDocument6 pagesStahl S Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Applicationsaviones123No ratings yet

- Self-Criticism and Self-Esteem in Early Adolescence: Do They Predict Depression?Document18 pagesSelf-Criticism and Self-Esteem in Early Adolescence: Do They Predict Depression?aviones123No ratings yet

- Read MeDocument3 pagesRead MeWilliams Antonio Pantoja LacesNo ratings yet

- Autism in U19s Quick GuideDocument4 pagesAutism in U19s Quick Guideaviones123No ratings yet

- Anderson - Embodied Cognition, A Field GuideDocument40 pagesAnderson - Embodied Cognition, A Field GuidelukeprogNo ratings yet

- Guia - TEA PDFDocument44 pagesGuia - TEA PDFsaraNo ratings yet

- Capi Tulo Abuso SexualDocument1 pageCapi Tulo Abuso Sexualaviones123No ratings yet

- News & Views: Can Imaging Extend The Thrombolytic Time Window After Stroke?Document2 pagesNews & Views: Can Imaging Extend The Thrombolytic Time Window After Stroke?aviones123No ratings yet

- News & Views: Can Imaging Extend The Thrombolytic Time Window After Stroke?Document2 pagesNews & Views: Can Imaging Extend The Thrombolytic Time Window After Stroke?aviones123No ratings yet

- POM - MODULE 6 (Ktuassist - In)Document20 pagesPOM - MODULE 6 (Ktuassist - In)sree_guruNo ratings yet

- The ART of Doing The Best Even When Surrounded by MediocracyDocument2 pagesThe ART of Doing The Best Even When Surrounded by MediocracyTanvi SNo ratings yet

- Unit 1Document42 pagesUnit 1Anushka MishraNo ratings yet

- Week 10 Civilizations and Its Discontents Brian Singer SOCI3692 Monisha SathivelDocument5 pagesWeek 10 Civilizations and Its Discontents Brian Singer SOCI3692 Monisha SathivelCorina-Mihaela MorosanNo ratings yet

- Perceiving Emotions Is About Being Aware of and Sensitive To Others' Emotions. in Other Words, It'sDocument9 pagesPerceiving Emotions Is About Being Aware of and Sensitive To Others' Emotions. in Other Words, It'srasha mostafaNo ratings yet

- 2nd Paper For ldr601Document5 pages2nd Paper For ldr601api-491563365No ratings yet

- Female Serial Killer Research PaperDocument7 pagesFemale Serial Killer Research Papervstxevplg100% (1)

- So561 Introduction To SociologyDocument3 pagesSo561 Introduction To SociologyAnish KumarNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Strategies in Sport PsychologyDocument23 pagesCognitive Strategies in Sport PsychologyGuille monsterNo ratings yet

- What Is SuicideDocument10 pagesWhat Is SuicideKwenzie FortalezaNo ratings yet

- The Social SelfDocument7 pagesThe Social SelfPatricia Ann PlatonNo ratings yet

- Management, Leadership, Supervision and AdministrationDocument5 pagesManagement, Leadership, Supervision and AdministrationWasim Rajput Rana100% (3)

- 5 Performance AssessmentsDocument10 pages5 Performance AssessmentsShaNe BesaresNo ratings yet

- Implementing Project-Based Learning Challenges and SolutionsDocument4 pagesImplementing Project-Based Learning Challenges and SolutionsConsultor Académico BooksNo ratings yet

- The Misbehaviour of BehaviouristsDocument28 pagesThe Misbehaviour of Behaviouristsrmmlopez@ig.com.br100% (1)

- Brief Interventions Radical Change Appendix 0Document13 pagesBrief Interventions Radical Change Appendix 0Filipe BoilerNo ratings yet

- Stress QuestionnaireDocument4 pagesStress QuestionnaireStephen Olusanmi AkintayoNo ratings yet

- Personal Philosophy of Nursing-Nurs 401Document7 pagesPersonal Philosophy of Nursing-Nurs 401api-369824515No ratings yet

- Communication Visual Body Language Kinesics Proxemics Paralanguage Haptics Chronemics Oculesics Voice Quality Prosodic Rhythm Intonation StressDocument1 pageCommunication Visual Body Language Kinesics Proxemics Paralanguage Haptics Chronemics Oculesics Voice Quality Prosodic Rhythm Intonation StresssheilaNo ratings yet

- Aeronautical Decision MakingDocument22 pagesAeronautical Decision Makingsaban2139100% (2)

- Sexual DysfunctionsDocument2 pagesSexual DysfunctionsEunice CuñadaNo ratings yet

- Confilct Management Chapter5Document31 pagesConfilct Management Chapter5botchNo ratings yet

- JOURNAL REVIEW (ISSUES SHAPING THE FUTUREp AND ETHICS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL TESTINGDocument8 pagesJOURNAL REVIEW (ISSUES SHAPING THE FUTUREp AND ETHICS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL TESTINGRaymart HumbasNo ratings yet

- MakaleleDocument10 pagesMakaleleyengeç adamNo ratings yet

- Fs 1 Learning PlanDocument4 pagesFs 1 Learning Planged rocamoraNo ratings yet

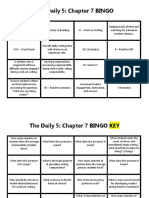

- The Daily 5 Chapter 7 BingoDocument2 pagesThe Daily 5 Chapter 7 Bingoapi-396925527No ratings yet

- Eaclipt Cpe 2019Document9 pagesEaclipt Cpe 2019inas zahraNo ratings yet

- Sex God Method - 2nd EditionDocument285 pagesSex God Method - 2nd Editionone85% (13)

- Chapter 10 Offences Relating To Sex, PedophileDocument12 pagesChapter 10 Offences Relating To Sex, PedophileKripa Kafley100% (1)

- Rrl-PsychDocument5 pagesRrl-PsychMavis VermillionNo ratings yet