Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Safety Guidelines For Performing Risk Assessments

Uploaded by

Faisal NadoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Safety Guidelines For Performing Risk Assessments

Uploaded by

Faisal NadoCopyright:

Available Formats

Safety Guidelines for Performing Risk Assessments

Prepared by the ASM-TSS Safety Guidelines Committee

Key Document Author: Lysa Russo, SUNY Stony Brook

TSS Safety Guidelines Committee Members:

Richard Neiser, Co-Chair Sandia National Laboratories

Lysa Russo, Co-Chair SUNY at Stony Brook

Rick Bajan Walbar Specialty Processing

Daryl Crawmer Thermal Spray Technologies

Klaus Dobler St. Louis Metallizing Company

Doug Gifford Praxair Surface Technologies

Donna Post Guillen Idaho National Engineering and

Environmental Laboratories

Peter Heinrich Linde AG

Terry Lester Metallisation, Ltd.

Larry Pollard Progressive Technologies

Gregory Wuest Sulzer Metco (US) Inc.

Safety Guidelines for Performing Risk Assessments

Final Draft 7/6/2010 Page1 of 11

This is a working document under consideration by an ASM International Thermal Spray Society’s

Committee on Safety. It is available solely to obtain comments from interested parties, and may not be

relied upon or utilized for any other purpose. Working documents may change substantially in future

versions.

DISCLAIMER:

This document represents a collective effort involving a substantial number of volunteer

specialists. Great care has been taken in the compilation and production of this document, but it

should be made clear that NO WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, WITHOUT

LIMITATION, WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR

PURPOSE, ARE GIVEN IN CONNECTION WITH THIS DOCUMENT. Although this information is

believed to be accurate by ASM International®, ASM cannot guarantee that favorable results will

be obtained from the use of this document alone. This document is intended for use by persons

having technical skill, at their sole discretion and risk. It is suggested that you consult your own

network of professionals. Since the conditions of product or material use are outside of ASM’s

control, ASM assumes no liability or obligation in connection with any use of this information. No

claim of any kind, whether as to products or information in this document, and whether or not

based on negligence, shall be greater in amount than the purchase price of this product or

publication in respect of which damages are claimed. THE REMEDY HEREBY PROVIDED

SHALL BE THE EXCLUSIVE AND SOLE REMEDY OF BUYER, AND IN NO EVENT SHALL

EITHER PARTY BE LIABLE FOR SPECIAL, INDIRECT OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES

WHETHER OR NOT CAUSED BY OR RESULTING FROM THE NEGLIGENCE OF SUCH

PARTY. As with any material, evaluation of the material under end use conditions prior to

specification is essential. Therefore, specific testing under actual conditions is recommended.

Nothing contained in this document shall be construed as a grant of any right of manufacture,

sale, use, or reproduction, in connection with any method, process, apparatus, product,

composition, or system, whether or not covered by letters patent, copyright, or trademark, and

nothing contained in this document shall be construed as a defense against any alleged

infringement of letters patent, copyright, or trademark, or as a defense against liability for such

infringement.

Comments, criticisms, and suggestions are invited, and should be forwarded to the Thermal

Spray Society of ASM International®.

1. SCOPE

1.1 Introduction to the approach and concept of a Risk Assessment.

1.2 Steps that can be taken to improve workplace safety.

1.3 Examples of thermal spray hazards

2. REFERENCED DOCUMENTS

Where standards and other documents are referenced in this publication, they

refer to the latest edition.

Publication Pub. Edition Available from:

TSSEA Code of Practice for the Safe Mr. Ivor Hoff:

Operation of Thermal Spraying Thermal.Sprayers@btinternet.com

Equipment

Thermal Spraying: Practice, Theory American Welding Society

and Application (Chapter 11) 550 N.W. LeJeune Road

Miami, Florida 331326

www.aws.org

Recommended Safe Practices for Reprint No. American Welding Society

Thermal Spraying 2, 1983 550 N.W. LeJeune Road

Final Draft 7/6/2010 Page2 of 11

This is a working document under consideration by an ASM International Thermal Spray Society’s

Committee on Safety. It is available solely to obtain comments from interested parties, and may not be

relied upon or utilized for any other purpose. Working documents may change substantially in future

versions.

Miami, Florida 331326

www.aws.org

A guide to the Health and Safety at (UK) 1974, L1, ISBN 0 7176 044441 1

Work etc. Act

Free Risk Radar software download www.spmn.com/products_software.html

3. TERMINOLOGY

3.1. Definitions

3.1.1. Risk Assessment – The steps involved in identifying, documenting and putting in

place the necessary controls to minimize or eliminate the potential risk of an

activity.

3.1.2. Frequency Rating – A measure of how often a particular activity with a potential

risk is performed.

3.1.3. Severity Rating – A measure of the potential for injury of a particular activity.

3.2. Keywords-- Risk Assessment, Safety, Frequency Rating, Severity Rating, Engineering

Controls, Administrative Controls, Confined Spaces, Hazard

4. RISK ASSESSMENTS

Every activity that is carried out on a daily basis, from driving a car to work or flying on

an airplane, poses a certain level of risk. It is the assessment of the risk (acceptable or

unacceptable) and then putting in place a plan of action to control the unacceptably high

risk, that can ultimately provide for a safer work environment.

The purpose of performing a risk assessment, or RA, is to make the workers and their

management aware of the hazards in the work environment. With this knowledge, each

risk can be identified in a methodical manner and a plan put in place to mitigate the

hazard. More time and effort should be spent mitigating hazards that pose the highest

risk, although no hazard should go unaddressed.

So, how does one perform a risk assessment? The information contained within this

document provides a logical approach that can be taken to minimize risk and maximize

safety. More formal descriptions of Risk Assessments are available and should also be

consulted. The purpose of this document is to introduce the concept in enough detail

that thermal spray practitioners can use it to improve safety in their work places.

Risk Assessments need to be customized to the specific workplace and to the actual

work being performed. Therefore, no two Assessments will be the same.

There are basically four steps to improving operational safety by using a risk

assessment. These are described in the sections below. Two case studies are given as

examples to illustrate the concepts involved. Please note that the specific ratings that

are used in this document are not as important as the methodology and approach that

has been taken.

Final Draft 7/6/2010 Page3 of 11

This is a working document under consideration by an ASM International Thermal Spray Society’s

Committee on Safety. It is available solely to obtain comments from interested parties, and may not be

relied upon or utilized for any other purpose. Working documents may change substantially in future

versions.

4.1 Identifying the Risks for Each Activity

The initial step of a RA is to carefully think about the various risks that are associated

with each activity and to document the hazards posed by these risks. The level of

hazard may be minimal or quite high, but anything that poses a real risk should be

identified and written down. Trivial risks, or risks that are always present (such as

walking into a wall or falling out of a chair) need not be addressed since they will only

dilute the effectiveness of the RA.

When identifying risks, a systematic, methodical approach is always required so that all

risks will be identified. This task can be quite complex and is sometimes overlooked.

Risk Assessments are recommended for use during the design stage for a new spray

facility. In this way, safety can be incorporated up front and costly upgrades and

modifications can be avoided. RA’s are also useful for examining the safety of existing

spray facilities. Flowcharting a process or operation can help in identifying risks

associated with certain actions. RA’s should be reviewed for completeness on a regular

basis. Significant changes in personnel, operating procedures or equipment should

trigger a review. At a minimum, annual reviews are recommended.

Some typical examples of activities performed in the thermal spray industry would be arc

spraying, combustion spraying, plasma spraying, handling of gas cylinders, the use of

cranes during lifting of parts to be sprayed, chemical cleaning, grit blasting, working in

confined spaces, handling hazardous materials, working with robotic equipment, etc.

4.2 Rating the Risk, (R)

In order for a RA to be practical and useful, the identified risks listed in step one need

to be rated. This will help to determine the most serious risks - those that need to be

given priority of action. A Risk Assessment number ( R ) is calculated by multiplying the

Frequency Rating ( F ), how often this risk is likely to occur, by the Severity Rating (S),

when the risk occurs, how severe is it :

R = F x S.

The following guidelines may be used in the frequency and severity rating:

Frequency Rating (F):

1 = Highly unlikely occurrence

2 = Remotely possible occurrence

3 = An occassional occurrence

4 = A fairly frequent occurrence

5 = A frequent and regular occurrence

6 = Almost certain that the event will occur

Severity Rating (S):

1 = Negligible injuries (i.e. scratches, hole in the wall, no downtime)

2 = Minor injuries (i.e. cuts and bruises, 1-2 days of downtime)

Final Draft 7/6/2010 Page4 of 11

This is a working document under consideration by an ASM International Thermal Spray Society’s

Committee on Safety. It is available solely to obtain comments from interested parties, and may not be

relied upon or utilized for any other purpose. Working documents may change substantially in future

versions.

3 = Major Injuries (i.e. concussion, broken bone(s), loss of limb or eye, major structural

damage, 3 or more days of downtime)

4 = Possible/Probable death or total loss of building

Example: An activity where accidents are recognized as a fairly frequent occurrence

has a Frequency Rating of 4. When the past records of these accidents are reviewed, it

is determined that these injuries have been minor, so a Severity Rating of 2 is given.

Therefore the Risk Rating ( R) is calculated as (Frequency x Severity) 4 x 2 = 8.

When performing the Risk Rating, it is important to note what the initial assumptions may

have been. Meaning, unskilled labor performing a skilled task would carry a higher risk

than skilled labor performing the same task. Other assumptions may be that equipment

is calibrated and working properly (i.e. has not been tampered with or modified),

operators have received proper training, etc.

4.3 Putting in Place the Actions Required to Minimize Risk

Once all of the risks have been identified and prioritized for each activity, it is now

important to identify the steps that are necessary to minimize or control each risk. It is

the implementation of these steps that ultimately improves safety.

Risk mitigation can be accomplished by several different means. Employee awareness

and training play a key role in mitigating work place hazards. Engineering controls that

prevent unsafe conditions from occurring are also important. An example of an

engineering control is the micro-switch that prevents the operation of a microwave oven

when the door is opened. The other major risk mitigation tool is Administrative Control.

These controls include such items as operational checklists, training, safe operating

procedures, maintenance schedules, and so on. A judicious combination of engineering

and administrative controls can often significantly reduce the risk of a potentially

hazardous task without being too expensive to implement or too complex to work with on

a daily basis. Ultimately, however, the successful reduction of risk relies on the

willingness of management and employees to initiate and maintain safe working

practices. Without the “buy-in” of operators, engineering staff and management, the

safety improvements possible through engineering and administrative controls can be

rendered useless.

It is highly recommended that all levels of employees participate in the risk assessment.

Identification of a risk is greatly dependent upon the perspective of the person

performing the task. What one person sees as a high level risk, another may see as

being only a moderate risk. Many organizations have a “stop work” policy that enables

any worker at any level to authorize a “stop work” if unsafe working conditions exist.

Operations cannot be resumed until the hazard is corrected.

4.4 Review and Update the Risk Assessment on Regular Basis

Because change is inevitable and these changes may affect the validity of the

actions/control measures that were put into place, it is very important that the Risk

Assessment be reviewed and updated on a regular basis. The review process is also a

Final Draft 7/6/2010 Page5 of 11

This is a working document under consideration by an ASM International Thermal Spray Society’s

Committee on Safety. It is available solely to obtain comments from interested parties, and may not be

relied upon or utilized for any other purpose. Working documents may change substantially in future

versions.

helpful tool in determining how useful/practical a given control measure has been in

minimizing the associated risk. Sometimes what seemed like a good idea at the time

proves to be too costly or difficult to manage.

There is no set rule as to how often this needs to be done, but rather is left up to the

discretion of the responsible party (company’s Health and Safety Officer, manager in

charge, etc). A good rule of thumb would be to review RA documents annually or

whenever a significant change (i.e. new equipment installation, new employee hire)

occurs.

In summary, an effective Risk Assessment should:

• Be systematic and logical in approach first looking at all of the activities / tasks that

are necessary to accomplish a given task and then looking at the risks for each

activity.

• Ensure that all relevant risks hazards have been addressed and identified.

• Focus on real risks and not obscure the RA with trivial risks or excess information.

• Prioritize the control measures / actions dealing with the highest, most significant

risks first.

• Identify what assumptions were made (skilled or unskilled labor, calibration of

equipment, etc.).

• Be regularly reviewed and updated / revised as necessary.

• Be signed off by the Manager responsible for the spray shop.

Final Draft 7/6/2010 Page6 of 11

This is a working document under consideration by an ASM International Thermal Spray Society’s

Committee on Safety. It is available solely to obtain comments from interested parties, and may not be

relied upon or utilized for any other purpose. Working documents may change substantially in future

versions.

Appendix I: Some Typical Thermal Spray Risks to Consider

When Performing a Risk Assessment

1. Explosion and suffocation/asphyxiation hazards from Compressed and

Combustible Gases, which may be at high pressures.

2. Old, worn or cracked cables and hoses can cause gas leaks or electrical shocks.

3. UV/ infrared from plasma/arc torches can cause burns to face/skin/eyes.

4. High sound levels from equipment can cause hearing damage.

5. High voltage and high currents/improper grounding connections can cause

electrical shocks that can be lethal.

6. Hot-sprayed parts or particles can cause burns and fires if directed at

combustible materials (i.e. paper, rags, clothing, etc).

7. Chronic exposure to powder and spray process dust, fumes and mists can cause

severe respiratory ailments.

8. Slippery floors from powder/water spills.

9. Mechanical pinch hazards from robots, turntables, automatic doors, etc.

10. Fire and explosions from fine metal powders and dust.

11. Handling Components: Manually or by crane, lifting or fork lift truck.

12. Risks associated with spraying of hazardous or toxic materials.

Final Draft 7/6/2010 Page7 of 11

This is a working document under consideration by an ASM International Thermal Spray Society’s

Committee on Safety. It is available solely to obtain comments from interested parties, and may not be

relied upon or utilized for any other purpose. Working documents may change substantially in future

versions.

Appendix II: Typical Engineering Control Procedures that can be used

In the Thermal Spray Process

1. Interlocks that: prevent walking into a spray booth that has robotic

manipulation, allow exhaust systems to vent rooms in cases of gas leaks, etc.

2. Warning lights and audible sounds (sirens)s

3. Lockout/tag out stations.

4. Required use of respirators and other personal protection equipment (PPE).

5. Use of gas leak detectors and oxygen sensors.

6. Properly designed sound attenuation spray booths.

7. Properly designed ventilation and filtration equipment.

8. Proper assessment of, and compliance with all local, state and federal

codes/norms/standards/regulations.

9. Selection of properly designed thermal spray equipment.

10. Properly designed part fixtures and tooling.

11. Maintaining and updating operator personnel records confirming safety and

training approvals.

12. Properly reviewing Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS).

Final Draft 7/6/2010 Page8 of 11

This is a working document under consideration by an ASM International Thermal Spray Society’s

Committee on Safety. It is available solely to obtain comments from interested parties, and may not be

relied upon or utilized for any other purpose. Working documents may change substantially in future

versions.

Appendix III: Typical Administrative Control Procedures

that can be used in the Thermal Spray Process

1. Written start-up and shutdown checklists.

2. Written and read standard operating procedures (SOPs).

3. Personnel safety training including respiratory/hearing training.

4. Equipment Maintenance/Calibration Schedules.

5. Scheduled thermal spray process and operation training.

6. Accident/incident procedures (reporting, investigation, corrective action, etc.).

7. Fire extinguisher training.

8. First-aid training, e.g., certified CPR training (required in some states).

Final Draft 7/6/2010 Page9 of 11

This is a working document under consideration by an ASM International Thermal Spray Society’s

Committee on Safety. It is available solely to obtain comments from interested parties, and may not be

relied upon or utilized for any other purpose. Working documents may change substantially in future

versions.

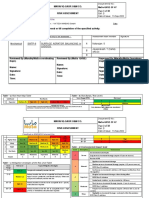

Case Study #1: Risk Assessment of Working in a Confined Space

Step 1: Define Risks of Activity.

In the case of working in a confined space, the specific risks could be: limited access

into and out of the booth, fumes, asphyxiation from gases, oxygen

enrichment/deficiency, an explosive or combustible atmosphere, excessive noise or

heat, etc.

Step 2: Rate the Risk (R).

Based upon the frequency (F) and severity (S) of each risk identified in Step 1, a table

can be made up which would weight the risk (R) and identify the hazards.

Activity: Working in a Confined Space

No HAZARD RISK F S R

1 Access / Exit Difficulty in entering / exiting 2 3 6

2 Fumes Inhalation causing illness 2 3 6

3 Asphyxiation (Oxygen Becoming unconscious / death 3 4 12

Depletion)

4 Oxygen Enrichment Fire and/or explosion 2 4 8

5 Explosive atmosphere Fire, explosion, death 3 4 12

6 Noise Hearing Damage 2 3 6

7 Heat Heat exhaustion 3 3 9

Step 3: Actions to Put in Place to Minimize/Reduce Risk:

For the activity of working in a confined space, the following steps would need to be put

into place to minimize the risk:

No Action / Control Measure

1 Test for explosive as well as breathable atmosphere (install gas detection system

which is interlocked with gas and exhaust system; keep space well ventilated

with clean and breathable air)

2 Install fire extinguishing equipment and alarms

3 Wear forced air breathing apparatus to minimize risk of oxygen depletion

4 All exits must be clear from blockage and identifiable even in the event of a power

loss

5 Hearing protection must be worn when necessary

6 Employees must undergo training for gas handling / hearing protection / fire

safety/respiratory protection

7 Use of a “buddy system” ensuring that someone else is always present

Step 4: Regularly Review and Update Process Risks and Actions to ensure that

assessment is still valid and being implemented appropriately.

Final Draft 7/6/2010 Page10 of 11

This is a working document under consideration by an ASM International Thermal Spray Society’s

Committee on Safety. It is available solely to obtain comments from interested parties, and may not be

relied upon or utilized for any other purpose. Working documents may change substantially in future

versions.

Case Study #2: Spraying a Bridge with Zn-Al Arc Sprayed Wire

Step 1: Define Risks of Activity.

In the case of performing this on-site arc spray job, some of the risks would be:

shock/electrocution from the spray wires, falling off scaffolding, breathing spray fumes.

Step 2: Rate the Risk (R).

Based upon the frequency (F) and severity (S) of each risk identified in Step 1, a table

can be made up which would weigh the risk (R) and identify the hazards.

Activity: Working in a Confined Space.

No HAZARD RISK F S R

1 Touching Wires Electric shock/Electrocution 2 3 6

2 Entanglement in Falling off scaffolding/death 3 4 12

Processes

wires/cables

3 Fumes Inhalation causing illness 2 3 6

Step 3: Actions to Put in Place to Minimize/Reduce Risk:

For the above activity, the following steps would need to be put into place to minimize

the risk:

No Action / Control Measure

1 Limit distance of exposed feed wires in set-up and provide protective barrier so

that wires can not be touched

2 Personnel must wear protective harness equipment to prevent falls.

3 Wear appropriate and approved respirators to minimize inhalation of zinc and

aluminum fumes. Note: Personnel must be “fit-tested” by a qualified industrial

hygienist before the use of a respirator.

4 Comply with all local, state and federal codes relating to this type of “construction”

related work as well as obtain all necessary permits.

Step 4: Regularly Review and Update Process Risks and Actions to ensure that

assessment is still valid and being implemented appropriately.

Final Draft 7/6/2010 Page11 of 11

This is a working document under consideration by an ASM International Thermal Spray Society’s

Committee on Safety. It is available solely to obtain comments from interested parties, and may not be

relied upon or utilized for any other purpose. Working documents may change substantially in future

versions.

You might also like

- Safety and Security Review for the Process Industries: Application of HAZOP, PHA, What-IF and SVA ReviewsFrom EverandSafety and Security Review for the Process Industries: Application of HAZOP, PHA, What-IF and SVA ReviewsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Security Controls Evaluation, Testing, and Assessment HandbookFrom EverandSecurity Controls Evaluation, Testing, and Assessment HandbookNo ratings yet

- Risk Management Techniques HAZOP and HAZ PDFDocument4 pagesRisk Management Techniques HAZOP and HAZ PDFJohn KurongNo ratings yet

- Oil Gas Offshore Safety Case (Risk Assessment) : August 2016Document44 pagesOil Gas Offshore Safety Case (Risk Assessment) : August 2016Andi SuntoroNo ratings yet

- Safety in Process Plant Design – Training Record SheetDocument21 pagesSafety in Process Plant Design – Training Record SheetSteve JobNo ratings yet

- ISA-TR84.00.03-2012 Mech Integrity SISDocument152 pagesISA-TR84.00.03-2012 Mech Integrity SISpetrawanNo ratings yet

- Ansi Asse Z590.2Document10 pagesAnsi Asse Z590.2Abdelhakim ChaouchNo ratings yet

- ISA-TR91.00.02-2003: Criticality Classification Guideline For InstrumentationDocument30 pagesISA-TR91.00.02-2003: Criticality Classification Guideline For Instrumentationselvaraj_mNo ratings yet

- 501 - 6.2.1.31 Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (HIRA) ProcedureDocument11 pages501 - 6.2.1.31 Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (HIRA) ProcedureJIGNESH SUTARIYANo ratings yet

- ISA-TR52.00.01-2006 Recommended Environments For Standards LaboratoriesDocument37 pagesISA-TR52.00.01-2006 Recommended Environments For Standards LaboratoriesALEJANDRO IPATZINo ratings yet

- Formal Safety Assessment in Maritime Industry - Explanation To IMO GuidelinesDocument17 pagesFormal Safety Assessment in Maritime Industry - Explanation To IMO Guidelinesadelinejoa20No ratings yet

- Ansi-Isa-Tr12.13.03 (2005)Document20 pagesAnsi-Isa-Tr12.13.03 (2005)nidevleNo ratings yet

- 19 - Attachment File 19 Hazard Analaysis and Risk AssesmentDocument10 pages19 - Attachment File 19 Hazard Analaysis and Risk AssesmentSana IdreesNo ratings yet

- Isa-12.01.01. Def. Electr. Areas ClasificadasDocument82 pagesIsa-12.01.01. Def. Electr. Areas ClasificadasArthurQuirozNo ratings yet

- Assessment and Risk Management of Potential Hazards by Failure Modes and Effect Analysis (FMEA) Method in Yazd Steel ComplexDocument11 pagesAssessment and Risk Management of Potential Hazards by Failure Modes and Effect Analysis (FMEA) Method in Yazd Steel ComplexDaniel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Automobile IndustryDocument8 pagesAutomobile IndustryArul PrasaadNo ratings yet

- The Steelworker Perspective on Behavioral Safety ProgramsDocument6 pagesThe Steelworker Perspective on Behavioral Safety Programswilfergue9745No ratings yet

- SHM - Practical 12 - Risk Assessment MethodsDocument8 pagesSHM - Practical 12 - Risk Assessment MethodsBhaliya AadityaNo ratings yet

- A Study On Occupational Hazards in Die Casting IndustriesDocument8 pagesA Study On Occupational Hazards in Die Casting IndustriesManik LakshmanNo ratings yet

- Campus incident guidelinesDocument14 pagesCampus incident guidelinesNestor MatusNo ratings yet

- Merican Ational Tandard: ANSI/ASSE Z590.2-2003Document10 pagesMerican Ational Tandard: ANSI/ASSE Z590.2-2003ravi00098No ratings yet

- ansi_assp_iso_31073_2022_previewDocument10 pagesansi_assp_iso_31073_2022_previewSavvas GiassasNo ratings yet

- Guidance On Hazard IdentificationDocument20 pagesGuidance On Hazard Identificationmath62210No ratings yet

- 2003 Dam Safety Risk Assessment White PaperDocument47 pages2003 Dam Safety Risk Assessment White PaperamirNo ratings yet

- Elements of PSM Terry Hardy.51145540Document12 pagesElements of PSM Terry Hardy.51145540Syed Mujtaba Ali Bukhari100% (1)

- Final Test of System Safety - Julian Hanggara AdigunaDocument6 pagesFinal Test of System Safety - Julian Hanggara AdigunaThe Minh NguyenNo ratings yet

- RA 20mar2022 vAHDocument8 pagesRA 20mar2022 vAHAbdellatef HossamNo ratings yet

- Hazard Analysis and Risk Assessment (HARA) Report For New ProductDocument11 pagesHazard Analysis and Risk Assessment (HARA) Report For New ProductIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- MME30001 Minor Activity OHS With Suggested Answers PDFDocument5 pagesMME30001 Minor Activity OHS With Suggested Answers PDFMosesNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 HvpeDocument12 pagesUnit 4 HvpeRamNo ratings yet

- Preview - ANSI+ISA+62443 4 2 2018Document17 pagesPreview - ANSI+ISA+62443 4 2 2018이창선No ratings yet

- Process Safety: Blind Spots and Red Ags: March 2011Document7 pagesProcess Safety: Blind Spots and Red Ags: March 2011mohammad basukiNo ratings yet

- Security Technologies For Production ControlDocument82 pagesSecurity Technologies For Production ControlJason MullinsNo ratings yet

- Safety Related QuestionsDocument5 pagesSafety Related QuestionsShivaniNo ratings yet

- Process Safety Management CH-523 Prof.: Zahoor@neduet - Edu.pkDocument70 pagesProcess Safety Management CH-523 Prof.: Zahoor@neduet - Edu.pkNaik LarkaNo ratings yet

- Ansi+asse+z359 2-2017Document68 pagesAnsi+asse+z359 2-2017Paulo PGNo ratings yet

- 15 A V O S H C: TH Nnual Irginia Ccupational Afety AND Ealth OnferenceDocument6 pages15 A V O S H C: TH Nnual Irginia Ccupational Afety AND Ealth Onferenceapi-25975704No ratings yet

- American National Standard: ANSI/ASSE Z359.0-2012 Definitions and Nomenclature Used For Fall Protection and Fall ArrestDocument40 pagesAmerican National Standard: ANSI/ASSE Z359.0-2012 Definitions and Nomenclature Used For Fall Protection and Fall ArrestChandrasekhar SonarNo ratings yet

- What is a risk assessmentDocument18 pagesWhat is a risk assessmentKhizar HayatNo ratings yet

- GUIDE TO CONDUCTING WORKPLACE SAFETY WALK-AROUNDSDocument2 pagesGUIDE TO CONDUCTING WORKPLACE SAFETY WALK-AROUNDSZulkarnaenUchihaNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Process SafetyDocument8 pagesThesis On Process Safetykimstephenswashington100% (2)

- Near-Miss A Tool For Integrated Safety Health EnviDocument18 pagesNear-Miss A Tool For Integrated Safety Health EnviAgung SanjayaNo ratings yet

- ISA-TR84.00.02-2002 - Part 1Document108 pagesISA-TR84.00.02-2002 - Part 1ЮрийПонNo ratings yet

- Hazard Analysis: Using The Hazard Identification ChecklistDocument3 pagesHazard Analysis: Using The Hazard Identification ChecklistRamkrishna PatelNo ratings yet

- Accident Incident Reporting and Investigation SiDocument2 pagesAccident Incident Reporting and Investigation SiJohn Jonel CasupananNo ratings yet

- Accident / Incident Reporting and Investigation: Environmental Health & SafetyDocument2 pagesAccident / Incident Reporting and Investigation: Environmental Health & SafetyRoyal BimhahNo ratings yet

- Csit 88610Document10 pagesCsit 88610daily needsbatamNo ratings yet

- Hazards, risks, fire classes, PSM elementsDocument4 pagesHazards, risks, fire classes, PSM elementsSadia MujeebNo ratings yet

- Construction & Maintenance Inspection Checklist - General: 1.1 Principles of A Workplace InspectionDocument50 pagesConstruction & Maintenance Inspection Checklist - General: 1.1 Principles of A Workplace InspectionSajeewa LakmalNo ratings yet

- SSPC Guide 3 - Paint Safety PDFDocument19 pagesSSPC Guide 3 - Paint Safety PDFAlexander SaulNo ratings yet

- Integrating ElectronicDocument90 pagesIntegrating ElectronicJason MullinsNo ratings yet

- What Is A Facility Siting StudyDocument10 pagesWhat Is A Facility Siting StudyAjay TulpuleNo ratings yet

- XBRA 3103 OSH Risk Management Assignment Jan 2020 V1Document16 pagesXBRA 3103 OSH Risk Management Assignment Jan 2020 V1Amran Sharif100% (4)

- Guidelines for Defining Process Safety Competency RequirementsFrom EverandGuidelines for Defining Process Safety Competency RequirementsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Term Paper On SafetyDocument7 pagesTerm Paper On Safetyafmzzaadfjygyf100% (1)

- BSC SafetyDocument10 pagesBSC SafetyEmad ElshaerNo ratings yet

- ANSI/ASSP Z590.2-2003 (R2012) : Criteria For Establishing The Scope and Functions of The Professional Safety PositionDocument20 pagesANSI/ASSP Z590.2-2003 (R2012) : Criteria For Establishing The Scope and Functions of The Professional Safety PositionBayu PutraNo ratings yet

- Chemical Plant Hazard Evaluation GuideDocument48 pagesChemical Plant Hazard Evaluation Guideanpuselvi125100% (1)

- Is 106Document35 pagesIs 106yoyoamit9051846812No ratings yet

- Accident InvestigationsDocument21 pagesAccident InvestigationsChandan KumarNo ratings yet

- RA Templates - Painting&blasting PDFDocument27 pagesRA Templates - Painting&blasting PDFrajendharNo ratings yet

- Parts Catalog: 2010/4 (Apr.) PublishedDocument77 pagesParts Catalog: 2010/4 (Apr.) PublishedRodolfo WongNo ratings yet

- Abbrasive BlastingDocument4 pagesAbbrasive Blastingصدام ابڑوNo ratings yet

- Driving at Work ActivitiesDocument7 pagesDriving at Work Activitiesrahul kavirajNo ratings yet

- Application Note 206 - Guide To Atmospheric Testing in Confined Spaces - 04 06 PDFDocument4 pagesApplication Note 206 - Guide To Atmospheric Testing in Confined Spaces - 04 06 PDFNiel Brian VillarazoNo ratings yet

- Basic Electrical Fundamentals TrainingDocument2 pagesBasic Electrical Fundamentals TrainingFaisal NadoNo ratings yet

- Industrial Hydraulic Safety HazardsDocument22 pagesIndustrial Hydraulic Safety Hazardsdefian ar100% (1)

- Safer Work Stairs and StepsDocument4 pagesSafer Work Stairs and StepsFaisal NadoNo ratings yet

- OhsasDocument209 pagesOhsasRizky AlamsyahNo ratings yet

- IHRDC Instructional Program 2015Document30 pagesIHRDC Instructional Program 2015aziznawawiNo ratings yet

- Example of A Completed Risk Assessment For A Accommodation (Hotel Herðubreið)Document7 pagesExample of A Completed Risk Assessment For A Accommodation (Hotel Herðubreið)John Rey TogleNo ratings yet

- Method Statement & Risk Assessment Installation of Structured Cabling SystemDocument16 pagesMethod Statement & Risk Assessment Installation of Structured Cabling SystemAbu Muhammed KhwajaNo ratings yet

- Philippines Risk AssessmentDocument179 pagesPhilippines Risk Assessmentallen syNo ratings yet

- Prevention and ProtectionDocument9 pagesPrevention and ProtectionMarlon FordeNo ratings yet

- Management of International Health and SafetyDocument54 pagesManagement of International Health and SafetyTayyab BlaGGunNo ratings yet

- Palm Oil Traceability Protocol: April 2019Document44 pagesPalm Oil Traceability Protocol: April 2019junemrsNo ratings yet

- IRATA Rope Access Training and Qualification Requirements R1Document9 pagesIRATA Rope Access Training and Qualification Requirements R1Trinh Dung100% (1)

- DRAFT - HIRARC REGISTER (45637)Document6 pagesDRAFT - HIRARC REGISTER (45637)Leliance Ann BillNo ratings yet

- Creating and Using a Business Case for IT Projects GuideDocument60 pagesCreating and Using a Business Case for IT Projects GuideOso JimenezNo ratings yet

- Nebosh IGC Q A PDFDocument287 pagesNebosh IGC Q A PDFFarofNo ratings yet

- Risk Based Maintanance PDFDocument9 pagesRisk Based Maintanance PDFRafaelPachecoNo ratings yet

- GTAG 8 - Auditing Application ControlsDocument34 pagesGTAG 8 - Auditing Application ControlsFAZILAHMEDNo ratings yet

- GCU Research and Project Risk Register Template (GOOD1)Document3 pagesGCU Research and Project Risk Register Template (GOOD1)Darren TanNo ratings yet

- Risk Management Framework ChecklistsDocument8 pagesRisk Management Framework ChecklistsJawaid IqbalNo ratings yet

- Chemistry Risk Assessment UV RadiationDocument3 pagesChemistry Risk Assessment UV RadiationWay to WorldNo ratings yet

- 63 Risk Assesments Testing and Pre-Commissioning WorksDocument18 pages63 Risk Assesments Testing and Pre-Commissioning WorksEngr.Syed Amjad100% (3)

- Study Guide - Isaca Certified in Governance of Enterprise It - Includes The Latest Practice Questions and AnswersDocument46 pagesStudy Guide - Isaca Certified in Governance of Enterprise It - Includes The Latest Practice Questions and Answerscipioo7No ratings yet

- Rist Assesment - Surface Aerator Balancing in LagoonDocument28 pagesRist Assesment - Surface Aerator Balancing in LagoonRajaNo ratings yet

- Updated GN4-2012Document18 pagesUpdated GN4-2012akhilNo ratings yet

- UNIT IOG SAMPLE MATERIAL - Hydrocarbon Process Safety PDFDocument7 pagesUNIT IOG SAMPLE MATERIAL - Hydrocarbon Process Safety PDFBakiNo ratings yet

- All Hira 2-1Document156 pagesAll Hira 2-1Mojib. AhmadNo ratings yet

- Sitxwhs 001 Learner Workbook v11 AcotDocument36 pagesSitxwhs 001 Learner Workbook v11 Acotsandeep kesarNo ratings yet

- Hazards Identification and Risk Assessment in Thermal Power Plant IJERTV3IS040583 PDFDocument4 pagesHazards Identification and Risk Assessment in Thermal Power Plant IJERTV3IS040583 PDFKalai Arasan100% (1)

- A Conceptual Framework For Estimation of Initial Emergency Food and Water Resource Requirements in DisastersDocument26 pagesA Conceptual Framework For Estimation of Initial Emergency Food and Water Resource Requirements in DisastersAngelinoRichieS. 20 054No ratings yet

- Welcomes You To ISO 19600:2014 Awareness Training ProgrammeDocument119 pagesWelcomes You To ISO 19600:2014 Awareness Training ProgrammeNada HajriNo ratings yet

- ERM by COSODocument38 pagesERM by COSOitsumidriwaNo ratings yet

- EGPC PSM GL 001 Hazard Identfication HAZID GuidelineDocument56 pagesEGPC PSM GL 001 Hazard Identfication HAZID Guidelinekhaled farag100% (2)