Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Changing The Name Needs Wide Consultation

Changing The Name Needs Wide Consultation

Uploaded by

jagadeesh dataramOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Changing The Name Needs Wide Consultation

Changing The Name Needs Wide Consultation

Uploaded by

jagadeesh dataramCopyright:

Available Formats

Volume XXX Number 124

NEW DELHI | FRIDAY, 8 SEPTEMBER 2023

Bharat’s tryst with destiny

Changing the name needs wide consultation

T

he use of “Bharat” in an English-language invitation from President

Droupadi Murmu to heads of State and governments, as well as chief

ministers, for an official banquet ahead of the G20 summit has sparked

unnecessary controversy over the name of the country. The Opposition

believes that the government’s choice of the Hindi word for the country, rather

than following convention, is a way of undermining the 26-party alliance that

goes by the name INDIA (the acronym stands for Indian National Developmental

Inclusive Alliance). Whatever the motive, the abrupt departure from standard

practice calls for an explanation from the government, especially because there

has been no official announcement or notification to this effect. The timing also

raises several questions. So far, there has been no issue over the country’s “inter-

national” and “indigenous” names, which are derived from constitutional provi-

sions. The first sub-clause of the first article of the English (and original) version

of the Constitution states, “India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States”.

In 1987, the 58th amendment to the Constitution empowered the President

to have the Hindi version of the Constitution published. The concomitant first

article gives primacy to the word Bharat — “Bharat that is India…”. The Hindi

version did not create controversy simply because Indians accepted that India

would be the term used internationally and in government publications in English,

which remains a language of official communication in India, while Bharat would

be used in Hindi publications. Most ordinary Indians have had no difficulty

absorbing this interchangeable usage, singing praises to “Bharat” in the national

anthem and rooting for “India” at international sporting events.

In over seven decades since Independence, there is no doubt that the term

“India” has shaped the country’s global identity, which must count for something

for a government that is keen to project power on the global stage. Indeed, the

G20 presidency is widely regarded as a platform to fulfil this ambition. It is possible

that the current government is keen to give the country a more indigenous identity

than the name India, which is a variation of a collective term used, first by the

Greeks, and later by West Asian traders, to refer to the sub-continental landmass

east of the Indus river. This is not a novel aspiration; several countries have

changed names to slough off colonial pasts — Sri Lanka (Ceylon), Zimbabwe

(Rhodesia), Malawi (Nyasaland), Burkina Faso (Upper Volta) and so on. Equally,

several countries have local names that differ from their international names —

Deutschland (Germany), Eire (Ireland), Misr (Egypt) and Zhongguo (China).

Similarly, variations of the term Bharat are used in several local languages

across the country. At the same time, there are also hundreds of communities

and minorities for whom the term Bharat may not have the same cultural reso-

nance. On the contrary, it may have exclusionary connotations. Retaining the

India-Bharat duality conveys a pleasing sense of ambiguity. Officially excluding

one of the names of the country, therefore, calls for wide consultation in an

intensely multicultural country such as Bharat/India. Finally, there is the question

of necessity. A name change is just that. Calling India only Bharat will not address

the many critical issues that the country faces and surely demand more govern-

mental concern and attention than the wording of a presidential invitation.

You might also like

- For A United India - Speeches of Sardar Patel 1947-1950 - NodrmDocument24 pagesFor A United India - Speeches of Sardar Patel 1947-1950 - NodrmRakesh Kumar100% (1)

- BAJA (2017) Virtual Round Results!!Document9 pagesBAJA (2017) Virtual Round Results!!Anonymous XsQJE44No ratings yet

- Brief History of State Bank of IndiaDocument3 pagesBrief History of State Bank of IndiaNikhil Sonawane67% (6)

- Pakistan Studies History Revision Notes O Level PDFDocument67 pagesPakistan Studies History Revision Notes O Level PDFAakash Malik87% (15)

- India, That Is Bharat: The Ongoing Debate: Why in News?Document3 pagesIndia, That Is Bharat: The Ongoing Debate: Why in News?hpmainpcNo ratings yet

- India VsDocument2 pagesIndia VsAbhishek SharmaNo ratings yet

- BHARATDocument2 pagesBHARATshubhamkenresearchNo ratings yet

- One Country, Many Names - What The Architects of Our Nation Said About India, That Is, Bharat' in Constituent AssemblyDocument9 pagesOne Country, Many Names - What The Architects of Our Nation Said About India, That Is, Bharat' in Constituent AssemblyShubhendu MishraNo ratings yet

- The Madras Anti Hindi AgitationDocument19 pagesThe Madras Anti Hindi Agitationjin moriNo ratings yet

- India That Is Bharat Contemporary or AncientDocument12 pagesIndia That Is Bharat Contemporary or AncientAyush VermaNo ratings yet

- South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal: India, That Is Bharat ': One Country, Two NamesDocument18 pagesSouth Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal: India, That Is Bharat ': One Country, Two NamesRavi GargNo ratings yet

- Priya Mishra - Language of India - Controversy Xid-3466648 1 IET9CBZ0PCDocument25 pagesPriya Mishra - Language of India - Controversy Xid-3466648 1 IET9CBZ0PCMayank SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Language Policy and ConstitutionDocument5 pagesLanguage Policy and ConstitutionSatyanayan RudrashettyNo ratings yet

- 11JLL1Document18 pages11JLL1haniyyah.ahmad01No ratings yet

- Priya Mishra - Language of India - Controversy Xid-3466648 1 iET9CBZ0PCDocument25 pagesPriya Mishra - Language of India - Controversy Xid-3466648 1 iET9CBZ0PCMayank SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Cooperative Federalism in IndiaDocument17 pagesCooperative Federalism in IndiaPUNYASHLOK PANDANo ratings yet

- Politics of Hindis Status Latest 1Document73 pagesPolitics of Hindis Status Latest 1harsh24971No ratings yet

- From Meluha To Hindustan, The Many Names of India and Bharat - Research News, The Indian ExpressDocument9 pagesFrom Meluha To Hindustan, The Many Names of India and Bharat - Research News, The Indian Expresslemon1975No ratings yet

- DP 272 T C James EnglishDocument48 pagesDP 272 T C James EnglishAtul TadviNo ratings yet

- Roshan Kishore: How A Bihari Lost His Mother Tongue To HindiDocument6 pagesRoshan Kishore: How A Bihari Lost His Mother Tongue To HindiSunidhi SinghNo ratings yet

- India Stand On GazaDocument5 pagesIndia Stand On GazaRaj MadhvanNo ratings yet

- A Tale of Two CommunalismsDocument1 pageA Tale of Two CommunalismsMundarinti Devendra BabuNo ratings yet

- India Vs Bharat by Devdutt PattanaikDocument2 pagesIndia Vs Bharat by Devdutt Pattanaikpaulrulez3157No ratings yet

- 2nd ExtrasDocument24 pages2nd ExtrasNivedha SundharalingamNo ratings yet

- India Today 25 Sept 2023Document88 pagesIndia Today 25 Sept 2023DALJEET SINGHNo ratings yet

- Real Face of Art-370 of Constitution of IndiaDocument106 pagesReal Face of Art-370 of Constitution of IndiaDaya Sagar100% (1)

- Insights Daily Current Events, 12 March 2016Document5 pagesInsights Daily Current Events, 12 March 2016Prateek BayalNo ratings yet

- Than Hindi The National Language Misinformation or Disinformation 250110Document8 pagesThan Hindi The National Language Misinformation or Disinformation 250110Firoz KhanNo ratings yet

- One Country One Language Against The Idea of Federalism By: Aayush Akar and Hitesh GangwaniDocument20 pagesOne Country One Language Against The Idea of Federalism By: Aayush Akar and Hitesh GangwaniLatest Laws TeamNo ratings yet

- Hindi: Hindī or Mānak HindīDocument4 pagesHindi: Hindī or Mānak HindīAmina SrkNo ratings yet

- Relevance With Constituional Law Domain/ ConstituionalismDocument2 pagesRelevance With Constituional Law Domain/ ConstituionalismSrishti AgrawalNo ratings yet

- A Many-Cornered Thing: The Role of Heritage in Indian Nation-BuildingDocument27 pagesA Many-Cornered Thing: The Role of Heritage in Indian Nation-BuildingUjjwal SharmaNo ratings yet

- How A Bihari Lost His Mother Tongue To Hindi: Roshan KishoreDocument7 pagesHow A Bihari Lost His Mother Tongue To Hindi: Roshan KishoreSunidhi SinghNo ratings yet

- Linguistics and Literature Review (LLR) : Yasir Abbas BaigDocument14 pagesLinguistics and Literature Review (LLR) : Yasir Abbas BaigUMT JournalsNo ratings yet

- Hindi, HinglishHead To HeadDocument8 pagesHindi, HinglishHead To HeadAbhishek Gautam100% (1)

- Language PolicyDocument40 pagesLanguage PolicyVishal AnandNo ratings yet

- Srirupa Roy - The National FlagDocument34 pagesSrirupa Roy - The National FlagShilpa JosephNo ratings yet

- Unit 4Document10 pagesUnit 4vishu.kumar2602No ratings yet

- The Effectiveness Establushing Hindi As A National LanguageDocument9 pagesThe Effectiveness Establushing Hindi As A National Languagejin moriNo ratings yet

- After Independence: A New and Divided NationDocument3 pagesAfter Independence: A New and Divided NationSumedha ThakurNo ratings yet

- South Asian EnglishesDocument12 pagesSouth Asian Englishesnayanachakrabarti.teachingNo ratings yet

- The Shanti Niketan: Webinar On Origin/ History of Hindi Language Date: 09/09/2021Document9 pagesThe Shanti Niketan: Webinar On Origin/ History of Hindi Language Date: 09/09/2021Aunkul PrajapatNo ratings yet

- Hindu Nationalism in Action The Bharatiya Janata Party and Indian PoliticsDocument8 pagesHindu Nationalism in Action The Bharatiya Janata Party and Indian PoliticsprateekvNo ratings yet

- Etymology: Main ArticleDocument1 pageEtymology: Main ArticleVPA 3No ratings yet

- The Persistance of Hindustani - Alok Rai PDFDocument10 pagesThe Persistance of Hindustani - Alok Rai PDFAshutoshNo ratings yet

- IJCRT2102205Document9 pagesIJCRT2102205Mohammad sazidNo ratings yet

- Secular ConstitutionDocument19 pagesSecular ConstitutionSandeep ShankarNo ratings yet

- SSC Project Class 10Document4 pagesSSC Project Class 10Mukul RajputNo ratings yet

- Agarwala, Nehru and Language ProblemDocument25 pagesAgarwala, Nehru and Language ProblemSuchintan DasNo ratings yet

- Federalism and Regionalism: Harihar BhattacharyaDocument29 pagesFederalism and Regionalism: Harihar BhattacharyaAshashwatmeNo ratings yet

- Editorial Analysis November CompilationDocument157 pagesEditorial Analysis November CompilationAdil Khan PathanNo ratings yet

- Dalit - WikipediaDocument33 pagesDalit - WikipediaAsis Kumar DasNo ratings yet

- 14 - India S DiasporaDocument4 pages14 - India S DiasporaRamreejhan ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Assembly DebatesDocument4 pagesConstitutional Assembly DebatesmNo ratings yet

- BHUTANDocument6 pagesBHUTANSakshi raniNo ratings yet

- IJMRD Article On Bangladeshi DaisporaDocument8 pagesIJMRD Article On Bangladeshi DaisporaSowmit JoydipNo ratings yet

- Summary of Sajal NagDocument4 pagesSummary of Sajal NagunnaynNo ratings yet

- 14-09 Language Policy OIA-NIA - HWWDocument67 pages14-09 Language Policy OIA-NIA - HWWrabiaqibaNo ratings yet

- Eternal Call of The Ganga PDFDocument14 pagesEternal Call of The Ganga PDFshiv161No ratings yet

- Language Conflict in IndiaDocument2 pagesLanguage Conflict in IndiaSaba Zameer BhatkarNo ratings yet

- 285918872-Indian-Identity Tharoor-Critical-Summary4567333Document2 pages285918872-Indian-Identity Tharoor-Critical-Summary4567333Vanlalruata Pautu100% (2)

- IE and IFS Module-A Unit-1 - An Overview of Indian EconomyDocument13 pagesIE and IFS Module-A Unit-1 - An Overview of Indian Economydhanushtrack3No ratings yet

- Course Outline, Bangladesh Stuides and CultureDocument4 pagesCourse Outline, Bangladesh Stuides and Cultureafif bin mustakimNo ratings yet

- Ministry of Road Transport and Highways Office of Minister For Road Transport Highways and ShippingDocument16 pagesMinistry of Road Transport and Highways Office of Minister For Road Transport Highways and Shippingmargarita BelleNo ratings yet

- UPSC Civil Services Examination: Modern Indian History Topic: Cripps MissionDocument3 pagesUPSC Civil Services Examination: Modern Indian History Topic: Cripps MissionSaurabh YadavNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument293 pagesUntitledStu D HD hgNo ratings yet

- CUET Certificate PDFDocument8 pagesCUET Certificate PDFBrijesh DwivediNo ratings yet

- India's First War of Independence 1857Document5 pagesIndia's First War of Independence 1857Sadam GillalNo ratings yet

- Foreign Direct Investment in Retail: February 23, 2004Document42 pagesForeign Direct Investment in Retail: February 23, 2004Himanshu DwivediNo ratings yet

- Class NotesDocument13 pagesClass NotesChandrika AthipatlaNo ratings yet

- 2013 Naxal Attack in Darbha Valley - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument7 pages2013 Naxal Attack in Darbha Valley - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediapatnamrajasekharNo ratings yet

- Dance Forms in India: By: Divij Arora, Class: VII-ADocument13 pagesDance Forms in India: By: Divij Arora, Class: VII-Aarun guptaNo ratings yet

- Communalism, Caste and ReservationsDocument9 pagesCommunalism, Caste and ReservationsGeetanshi AgarwalNo ratings yet

- From (Chaitanya Chauhan (Chaitanyachauhan91@gmail - Com) ) - ID (549) - History 2Document14 pagesFrom (Chaitanya Chauhan (Chaitanyachauhan91@gmail - Com) ) - ID (549) - History 2Mukesh TomarNo ratings yet

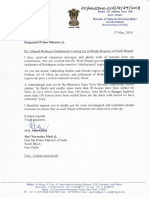

- Letter by Ahluwalia To The Prime MinisterDocument5 pagesLetter by Ahluwalia To The Prime MinisterSwarajyaNo ratings yet

- Andhra Elected Councilors List, 2014Document144 pagesAndhra Elected Councilors List, 2014raghuNo ratings yet

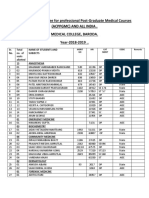

- Admission Committee For Professional Post-Graduate Medical Courses (Acppgmc) and All India - Medical College, Baroda. Year-2018-2019 .Document5 pagesAdmission Committee For Professional Post-Graduate Medical Courses (Acppgmc) and All India - Medical College, Baroda. Year-2018-2019 .Abhishek JoshiNo ratings yet

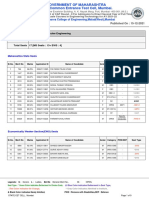

- Merit List of DiplomaDocument9 pagesMerit List of DiplomaOMKAR PAREKHNo ratings yet

- Is 5533 1969 PDFDocument14 pagesIs 5533 1969 PDFEvie McKenzie100% (1)

- Indian Newspaper and Magazine Industry Porter's 5 Forces Existing CompetitionDocument6 pagesIndian Newspaper and Magazine Industry Porter's 5 Forces Existing CompetitionMayank UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Tilottama Mukherjee-Markets in 18th C Bengal Economy PDFDocument35 pagesTilottama Mukherjee-Markets in 18th C Bengal Economy PDFShreejita BasakNo ratings yet

- Mca Provisional Merit 2022Document751 pagesMca Provisional Merit 2022Pranav PasteNo ratings yet

- Jadui PitaraDocument6 pagesJadui PitaraShubham TiwariNo ratings yet

- Class 9 Resource Book NewDocument40 pagesClass 9 Resource Book NewSajjad FaisalNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument24 pagesIntroductionTariq KhanNo ratings yet

- Following Is A List of Some Formal Schools of Delhi:: S No School Branch Address Telephone No. WebsiteDocument4 pagesFollowing Is A List of Some Formal Schools of Delhi:: S No School Branch Address Telephone No. WebsiterashidnyouNo ratings yet

- Final DRDNB Seats For SS Counselling 2021Document152 pagesFinal DRDNB Seats For SS Counselling 2021Pavan KumarNo ratings yet

- Allot 2011 Other MediDocument69 pagesAllot 2011 Other Medippskhan5748No ratings yet