Professional Documents

Culture Documents

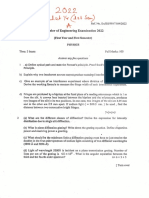

14optical Transmission at Oblique Incidence Through A

Uploaded by

adamhong0109Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

14optical Transmission at Oblique Incidence Through A

Uploaded by

adamhong0109Copyright:

Available Formats

Optical transmission at oblique incidence through a

periodic array of sub-wavelength slits in a metallic host

Yong Xie, Armis R. Zakharian, Jerome V. Moloney, and Masud Mansuripur

College of Optical Sciences, The University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721

xie@email.arizona.edu

Abstract. Using the Bloch modes of a periodic, semi-infinite array of slits

in a metallic host, we study the transmission of obliquely incident plane-

waves through sub-wavelength slits. Matching the tangential E- and H-

fields at the entrance facet of the periodic structure yields the complex

amplitudes of the various Bloch modes, which exist and propagate within

the slit array independently of each other. The computational scheme is

robust, convergence is rapid, and a good match at the boundaries is obtained

in every case. The regions examined in some detail include the vicinity of

the Wood anomaly (where new diffraction orders appear/disappear on the

horizon), the neighborhood of a point where surface plasmon polaritons

(SPPs) are excited, and an ordinary situation in which the incidence angle is

far from the angles that invoke Wood’s anomaly or cause the excitation of

SPPs. Field distributions and energy flow diagrams in and around the slits

reveal the existence of transmission minima (and reflection maxima) at

incidence angles associated with the excitation of SPPs.

©2006 Optical Society of America

OCIS codes: (050.1220) Apertures; (050.1960) Diffraction theory; (240.5420) Polaritons;

(240.6680) Surface plasmons; (260.3910) Optics of metals; (310.2790) Guided waves.

References and links

1. Y. Xie, A. R. Zakharian, J. V. Moloney, and M. Mansuripur, "Transmission of light through periodic arrays of

sub-wavelength slits in metallic hosts," Opt. Express 14, 6400-6413 (2006).

2. R. W. Wood, “On a remarkable case of uneven distribution of light in a diffraction grating spectrum,” Proc.

Phys. Soc. London 18, 269-275 (1902).

3. R. W. Wood, “Anomalous diffraction gratings,” Phys. Rev. 48, 928-937 (1935).

4. Lord Rayleigh, “On the dynamic theory of gratings”, Proc. R. Soc. A 79, 399-416 (1907).

5. J. A. Porto, F. J. García-Vidal, and J. B. Pendry, “Transmission resonance on metallic gratings with very narrow

slits,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 02845(4) (1999).

6. Q. Cao and Ph. Lalanne, “Negative role of surface plasmons in the transmission of metallic gratings with very

narrow slits,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 057403(4) (2002).

7. Y. Xie, A. R. Zakharian, J. V. Moloney, and M. Mansuripur, “Transmission of light through a periodic array of

slits in a thick metallic film,” Opt. Express 13, 4485 (2005).

8. H. Raether, Surface Plasmons on smooth and rough surfaces and on gratings, (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1986).

9. J. D. Jackson, Classical Electrodynamics, 3rd edition (Wiley, New York, 1999) Chap. 8.

10. P. Edward, Handbook of optical constants of solids, 1st edition (Academic Press, 1997).

11. M. G. Moharam, E. B. Grann, D. A. Pommet, and T. K. Gaylord, “Formulation for stable and efficient imple-

mentation of the rigorous coupled-wave analysis of binary gratings,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 12, 1068-76 (1995).

12. Ph. Lalanne and G. M. Morris, “Highly improved convergence of the coupled-wave method for TM

polarization,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 13, 779-784 (1996).

1. Introduction

This paper is a follow-up to our previous publication [1], where we employed the Bloch

modes of a slit array in a semi-infinite metallic host to investigate the transmission of a

normally incident plane-wave through sub-wavelength slits. Toward the end of that paper, we

briefly discussed the case of oblique incidence at small angles (i.e., close to normal

incidence), thus demonstrating the utility of the Bloch mode analysis for interpreting the

results of experiments involving oblique-incidence on metallic gratings, such as those

#74253 - $15.00 USD Received 22 August 2006; accepted 22 September 2006

(C) 2006 OSA 30 October 2006 / Vol. 14, No. 22 / OPTICS EXPRESS 10220

conducted by R. W. Wood early in the 20th century [2, 3]. In the present paper we expand

upon the earlier analysis and explore the transmission properties of a metallic slit array having

a fixed period and a fixed slit width under plane-wave illumination at angles of incidence

ranging from 0˚ to 90˚.

The setup for our calculations is shown in Fig. 1. Because the system is invariant along

the x-axis, its optical behavior can be studied separately for the two cases of transverse

electric (TE) polarization (involving the field components Ex, Hy, Hz) and transverse magnetic

(TM) polarization (involving Hx, Ey, Ez). As in the previous paper, the focus of attention will

be the case of TM polarization, as illumination with TE-polarized light does not excite any

guided modes within subwavelength slits.

x

y

w p

Fig. 1. A TM-polarized plane-wave (Hx, Ey, Ez) is incident from the air on a semi-infinite slit

array at the angle θ. The plane of incidence is yz, the vacuum wavelength of the light is

λo = 1.0 μm, and the slits are in a silver host having εm = − 48.8 + 2.99i. Throughout this paper,

the period of the structure is fixed at p = 1.2 μm, and the slit apertures, filled with air, are

assumed to have a width w = 0.1μm (i.e., one-tenth of one wavelength). The bottom of the

array is placed at z = ∞ to eliminate the influence of the light returning from the bottom facet

on reflected and transmitted light at the top (entrance) facet of the array.

Section 2 describes the propagation constants and field profiles of the various

electromagnetic modes of a semi-infinite slit array in a metallic host. For any given angle of

incidence θ , the modes satisfy the corresponding Bloch condition [1], and are therefore

referred to as Bloch modes. Matching the tangential components of the E- and H-fields at the

entrance facet of the array is discussed in Section 3, where we demonstrate the convergence of

the Bloch mode series for three representative angles of incidence. The three skew angles

selected for discussion represent the cases of ordinary behavior (i.e., incidence angles that are

sufficiently far from anomalous angles), Wood’s anomaly, observed when a new diffraction

order appears/disappears on the horizon [4], and the excitation of surface plasmon polaritons

(SPPs) at the entrance facet of the array [5-7]. In Section 4 we analyze the behavior of a slit

array throughout the entire range of skew angles (θ = 0 : 90˚), and examine the

aforementioned three types of behavior for specific incidence angles. The anomalous angles

revealed by the Bloch mode analysis will be shown to satisfy simple formulas involving the

incident light’s wavelength, the period of the array, and the SPP’s characteristic refractive

index. Also presented and discussed in Section 4 are the field profiles in and around the slits.

As in the previous paper [1], we use Raether’s definition of the SPP [8], a localized

electromagnetic wave confined to the vicinity of a dielectric-metal interface, consisting of a

single evanescent plane-wave on the dielectric side of the interface, and a single

#74253 - $15.00 USD Received 22 August 2006; accepted 22 September 2006

(C) 2006 OSA 30 October 2006 / Vol. 14, No. 22 / OPTICS EXPRESS 10221

inhomogeneous plane-wave [9] on the metallic side. At λo = 1.0 μm, at the interface between

silver (dielectric constant εm = − 48.8 + 2.99i; see Ref. [10]) and free-space (εd = 1.0), the real

part of the effective refractive index of the SPP, nspp =√εmεd /(εm + εd), is ~ 1.01.

2. Propagation constants and Bloch mode profiles

With reference to Fig. 1, we express the E- and H-fields inside the slits – which are either

empty or filled with a transparent material of dielectric constant εs – and also the fields in the

metallic regions between adjacent slits as superpositions of two (generally inhomogeneous)

plane-waves bouncing back and forth between the vertical walls. The H-field transmitted

below the surface at z = 0 is thus written

⎧ w w

⎪exp(ik0σ zn z ){h1ns exp[ik0σ nys ( y + w / 2)] + h2ns exp[ −ik0σ ys

n

( y − w / 2)]}, − < y<

⎪ 2 2

n

H xT ( y, z ) =⎨ (1)

⎪exp(ik σ n z ){h n exp[ik σ n ( y − w / 2 + p)] + h n exp[−ik σ n ( y + w / 2)]}, − p ≤ y ≤ − w

w

⎪

⎩

0 z 1m 0 ym 2m 0 ym

2 2

Here n is the mode index (1, 2, 3, …), ko=2π/λo is the vacuum wave-number, σ zn is the nth

mode’s propagation constant along the z-axis, the subscript s denotes the slit region, and the

subscript m denotes the metallic host medium (i.e., cladding for the slit waveguides). Inside

the slits (σ ysn) 2 + (σ zn) 2 = εs, where εs is the relative permittivity of the filling material, while

in the metal (σ ymn) 2 + (σ zn) 2 = ε m, where ε m is the relative permittivity of the host material.

Maxwell’s equations relate the E-field to the H-field, and, subsequently, the continuity of the

tangential components of E and H at the (vertical) slit walls, in conjunction with the Bloch

condition for a given incidence angle θ, enable one to determine the unknown parameters of

each and every Bloch mode [1].

Compared to the case of normal incidence discussed in Ref. [1], for a given period p,

oblique incidence involves twice as many Bloch modes within a given region of the complex

plane in which the propagation constant σ zn resides. The reason is that normal incidence

invokes only the even modes of the array, whereas oblique incidence breaks the left-right

symmetry, thus admitting additional modes. (The designations even and odd are relative to an

axis of symmetry of the array, say, the x-axis passing through the center of a slit). As a matter

of fact, anti-symmetric modes are also found in the case of normal incidence, but their

coefficients turn out to be zero when the boundary conditions at the entrance facet are

matched.

We searched for the propagation constants σ zn in a rectangular region of the complex

plane. The region was sampled with a small grid size, fine enough to guarantee that no roots

of the characteristic equation were missed [1]. We scanned the grid for local minima, and

searched for the roots in the vicinity of each such minimum. For the slit array of Fig. 1 at

θ = 30°, Fig. 2 shows the complex-plane location of some of the roots, σ z, as well as the

corresponding σ ys and σ ym. The modes are numbered according to the strength of the

imaginary part of σ z, which means that the lower-order modes propagate deeper into the slits.

Except for the first mode – the sole guided mode in the present example – all other modes

have a large imaginary component in their σ z, thus residing mainly at the entrance facet of the

slit array. Most of these higher-order modes, however, have a negligible loss along the y-axis

(see the values of σ ym in Fig. 2); consequently, they propagate parallel to the upper surface of

the slit array, helping to establish the continuity of the tangential E- and H-fields at this facet.

Profiles of the first twelve modes of the slit array of Fig. 1 at θ = 30˚ are shown in Fig. 3.

Here the Hx profiles appear on the left-hand side, while those of Ey appear on the right. In each

case, the field’s magnitude and phase profiles are shown in the top and bottom frames,

respectively. The mode number in each frame ranges from 1 to 12, top to bottom, as shown.

Some modes are symmetric-like (e.g., modes 6, 8), while others are anti-symmetric-like (e.g.,

modes 5, 7). The phase profile of the incident plane-wave is preserved through the Bloch

#74253 - $15.00 USD Received 22 August 2006; accepted 22 September 2006

(C) 2006 OSA 30 October 2006 / Vol. 14, No. 22 / OPTICS EXPRESS 10222

condition embedded in the structure of each and every Bloch mode, thus guaranteeing, for

instance, that the 0th-order beam that exits the slit array will propagate in the same direction as

the incident beam.

Fig. 2. Propagation constants of modes numbered 3 to 40 for the slit array depicted in Fig. 1 at

θ = 30°; the arrows indicate the direction of increasing mode number. For each mode, the

propagation constant along the z-axis, σ z, is the same in the slit and in the metallic cladding.

Along the y-axis, the propagation constants in the slit are ±σys, while those in the metallic

region are ±σym; see Eq. (1). Parameters of the first two modes (not shown because they are off

the charts) are: σz(1) = 1.2119 + 0.0066i, σys(1) = 0.0116 − 0.6847i, σym(1) = 0.2219 + 7.0941i and

σz(2) = 0.0002 + 4.8308i, σ ys(2) = 4.9332 − 0.0002i, σ ym(2) = 0.3126 + 5.0567i.

Fig. 3. Profiles of the first twelve modes of the slit array depicted in Fig. 1 at θ = 30˚; left: Hx,

right: Ey. In each case, the field’s magnitude is shown at the top and the corresponding phase

profile at the bottom. For display purposes each profile is individually normalized.

#74253 - $15.00 USD Received 22 August 2006; accepted 22 September 2006

(C) 2006 OSA 30 October 2006 / Vol. 14, No. 22 / OPTICS EXPRESS 10223

From the phase plots of Fig. 3, the first mode is seen to be symmetric; this may also be

inferred from the computed amplitudes of the corresponding plane-waves that reside within

the slits, namely, h1s(1) = h2 s(1); see Eq. (1). The second mode in Fig. 3 is anti-symmetric; again

this may be inferred from the computed amplitudes of the mode’s constituent plane-waves,

namely, h1s(2) = − h2s(2). The first two modes in this example are essentially the same for all

angles of incidence θ, the reason being that their large absorption coefficients along y in the

metallic region – see Im [σ ym(1, 2)] in caption to Fig. 2 – prevent the modal fields of adjacent

slits from interacting with each other. As for the higher-order modes, although the magnitudes

tend to be similar for different values of θ , the modal phase profiles have a certain well-

defined dependence on the incidence angle.

3. Matching the boundary conditions at the entrance facet of the slit array

For the system depicted in Fig. 1 with λo = 1.0 μm, θ = 30°, p = 1.2 μm, w = 0.1 μm, silver

host, we computed the coupling coefficients by matching the tangential fields, Ey and Hx, at

the entrance facet using a total of N = 120 modes in each space (i.e., 120 modes in the

free space of incidence and 120 modes in the slit array). Our method of minimizing the

mismatch at the entrance facet is described in Ref. [1]. The matched field magnitudes on both

sides of the z = 0 interface are plotted in Fig. 4. The match is excellent, and the difference

between the incident optical power and the combined reflectance and transmittance of the

array, R + T, was found to be less than 0.1%. The sharp peaks of the Ey-field at the slit edges,

y = ± 0.05 μm, represent a significant accumulation of electrical charge at these sharp corners.

− 0.6 − 0.4 − 0.2 0.2 0.4 0.6

Fig. 4. Profiles of Hx and Ey magnitudes across a full period of the slit array in silver host

(λo = 1.0μm, θ = 30˚, p = 1.2 μm, w = 0.1 μm). A total of N = 120 modes (in each space) was

used to reduce the mismatch between the tangential E and H fields at the interface.

Next, we examine the convergence of the Bloch mode series expansion. With reference to

Fig. 5(a), the magnitudes of the first five modes of the slit array, C1, C2, … C5, were computed

using values of N ranging from 2 to 120, N being the total number of modes included in the

calculations. For the first five modes, we have plotted (versus N ) the difference between the

intermediate values of each coefficient (computed with N < 120) and the final, steady-state

value (obtained with N = 120). Shown in Fig. 5(a) are plots of the mode-magnitude error,

|ΔCn |, versus the number N of modes used to match the boundary conditions. It is seen that,

with increasing N, the mode coefficients rapidly converge to their steady-state values. In

general, we found N ~ 50 to be sufficient for obtaining the coupling coefficients with less than

0.1% error. (This is roughly twice the number of modes needed in the case of normal

incidence [1], where only “even modes” are excited, while odd modes are ignored at the

outset.)

Figure 5(b) shows the magnitudes of the first 20 modes of the slit array (computed with

N = 120) for three cases of interest, labeled as Ordinary, Wood, and SPP. The “Ordinary” case

#74253 - $15.00 USD Received 22 August 2006; accepted 22 September 2006

(C) 2006 OSA 30 October 2006 / Vol. 14, No. 22 / OPTICS EXPRESS 10224

(blue symbols) corresponds to θ = 30˚, representing a typical situation that is free from

anomalies (more about anomalies in Section 4). In the case of the Wood anomaly at θ = 9.6˚

(green), convergence behavior is not too different from that of the Ordinary case. In the case

of SPP resonance at θ = 10.2˚ (red), the first mode, which is the guided mode of the slit, is

fairly weak, modes 3, 4 and 5 have relatively large amplitudes, and the high-order modes

(beyond n = 5) are weak again. As was the case at normal incidence [1], the SPP excitation

tends to suppress the guided mode as well as all high-order modes of the slit array. A fraction

of the incident light is then strongly absorbed within the skin-depth of the metallic host at the

entrance facet, while the remaining light returns (in the form of specularly reflected or

diffracted plane-waves) to the incidence space.

Fig. 5. (a) Convergence of the coefficients of the first five modes of the slit array to their final

values, displayed as function of the number of modes, N, used to minimize the mismatch across

the z = 0 interface in the case of θ = 30°. (b) Magnitudes of the first 20 modes (obtained with a

total of N = 120 modes used to reduce the mismatch) for three different angles of incidence:

(blue) θ = 30°, an ordinary case; (green) θ = 9.6°, Wood’s anomaly; (red) θ = 10.2°, SPP

excitation. In all cases the host material is silver, λo = 1.0 μm, p = 1.2 μm, and w = 0.1 μm.

4. Wood’s anomaly and SPP excitation at oblique incidence

Using an expansion of the transmitted fields into the Bloch mode series, we computed, for

angles of incidence θ ranging from 0˚ to 89˚, the reflectance R , guided mode’s transmittance

T1 (i.e., fraction of the incident Poynting vector component Sz entering the slits), and total

transmittance T (including losses at the entrance facet); the results are shown in Fig. 6. For

each value of θ , a total of N = 120 modes (in each space) were included in the calculations;

this number did not have to be adjusted as θ rose from small to large, and the quality of the

match at the entrance facet was high for all incidence angles.

The values of R, T, and T1 in Fig. 6 were computed in the xy-plane at the entrance facet of

the slit array by integrating the Poynting vector component Sz ( y, z = 0) over one period p of

the array for the following cases:

i) incident plane-wave at z = 0− (used for normalization purposes);

ii) superposition of all reflected modes in the incidence space at z = 0− (used to compute R);

iii) superposition of all the Bloch modes of the slit array at z = 0+ (used to compute T );

iv) guided mode entering the slits, namely, the first Bloch mode of the array at z = 0+.

In Fig. 6, the difference between the green curve (total transmittance T ) and the red curve

(guided mode’s transmittance T1) is the fraction of the optical power absorbed within the skin-

depth at the entrance facet. The two sharp dips in T and T1 (coinciding with the spikes in R ) at

θ = 10.2° and θ = 41° correspond to SPP anomalies. The small, highly localized peaks in T

and T1 adjacent to SPP anomalies (coinciding with the tiny dips in R ) are manifestations of

the Wood anomaly at θ = 9.6° and θ = 41.8°. Transmissivity reaches a maximum of T ~ 60%

at θ = 82.5˚, before diminishing at the grazing incidence, θ → 90°, where R approaches unity.

#74253 - $15.00 USD Received 22 August 2006; accepted 22 September 2006

(C) 2006 OSA 30 October 2006 / Vol. 14, No. 22 / OPTICS EXPRESS 10225

Fig. 6. Reflectivity R (blue), total transmissivity T (red), and transmission efficiency T1 of the

guided mode (green), versus the incidence angle θ for the semi-infinite slit array depicted in

Fig. 1 (silver host, p = 1.2 μm, w = 0.1 μm, λ o = 1.0 μm).

The anomalous incidence angles may be readily estimated from simple formulas [1, 4].

At Wood’s anomaly, the Bragg condition should indicate the appearance, on the horizon, of a

new diffraction order m. The SPP anomaly occurs when a diffracted order m acquires the SPP

wavelength of λ o / Re[nspp], where nspp =√εmεd /(εm + εd). Thus θ Wood, θ spp may be found from:

sin (θ Wood) + m (λo/p) = ±1, (2a)

sin (θ spp) + m (λo/p) = ± Re [nspp]. (2b)

For p = 1.2μm, λ o = 1.0μm, m = 1, Re [nspp] = 1.01, we find θ Wood = 9.6°, θ spp = 10.2°; these

correspond to the first set of anomalies in Fig. 6. The second set, θ Wood = 41.8°, θ spp = 41.0°,

corresponds to m = −2. Carrying out the Bloch mode calculations in steps of Δθ = 0.1°, we

found close agreement with these predicted anomalous angles.

Fig. 7. Field magnitudes (Hx, Ey, Dz ) and Poynting vector S in the yz cross-sectional plane of

the array of Fig. 1 (silver host, p = 1.2 μm, w = 0.1 μm, λ o = 1.0 μm) for three different cases.

Top row: ordinary behavior at θ = 30°; middle row: Wood’s anomaly at θ = 9.6°; bottom row:

SPP anomaly at θ = 10.2°. The color in the Poynting vector diagrams (right-hand column)

encodes the magnitude of S, while the arrows indicate the direction of flow of energy.

#74253 - $15.00 USD Received 22 August 2006; accepted 22 September 2006

(C) 2006 OSA 30 October 2006 / Vol. 14, No. 22 / OPTICS EXPRESS 10226

The field profiles of Fig. 7 show in detail how the slit array modifies the field

distributions in the incidence space near the slits. A non-zero Poynting vector component Sy

(parallel to the surface) is, of course, expected at skew incidence. In the ordinary case (θ = 30˚)

shown in the top row of Fig. 7, the fields do not differ all that much from those at normal

incidence [1], but the charge accumulation at the slit’s left edge (evident in the |Ey| plot) and

the one-sided flow of energy into the slit are noteworthy. At the Wood anomaly (θ = 9.6˚,

middle row), the incident fields are seen to be coupled into the guided mode of the slit, there

is charge accumulation on the left edge, and the energy flow behavior is fairly complex. In the

case of the SPP anomaly at θ = 10.2˚ (bottom row), the incident optical power strikes the

metallic surface on the left side of the slit, bounces back, and lands again on the metal on the

right-hand side. The incident power flux thus misses the slits altogether, resulting in negligible

transmission through the array. Note the left-right symmetry of the surface charge and surface

current profiles on the top metallic surface in the case of SPP excitation [surface current

density along y = Hx(y, z = 0−); surface charge density ≈ Dz(y, z = 0−)].

Fig. 8. Profiles of |Hx |, |Ey |, |Dz | and the Poynting vector S in the yz cross-sectional plane of the

array of Fig. 1 at θ = 82.5˚ (silver host, p = 1.2 μm, w = 0.1 μm, λ o = 1.0 μm). In the Poynting

vector plot the color encodes | S |, while the arrows show the direction of flow of energy.

Shown in Fig. 8 are the field profiles at θ = 82.5°, the point in Fig. 6 where R reaches a

minimum (and T a maximum). As in the “ordinary” case of θ = 30° discussed in conjunction

with Fig. 7, a hot spot of accumulated charge appears on the slit’s left edge, but no strong

tendency is observed on the part of the Poynting vector S to turn around and head for the slits.

The peaking of T and T1 around θ = 82.5° is thus a consequence of the reduced incident Sz at

large skew angles rather than an enhancement of the transmitted Sz.

5. Concluding remarks

The Bloch mode expansion of the optical field in a metallic slit array is a viable calculation

scheme, which is readily applicable to the case of incidence at arbitrary skew angles. Each

Bloch mode, being a natural mode of the structure, propagates within the array independently

of all the other modes. The strength of each mode is determined at the entrance facet by

matching the incident E and H fields to the collective profile of the reflected and transmitted

fields. One advantage of the Bloch mode method over the traditional Rigorous Coupled Wave

Analysis (RCWA) [11, 12] is its rapid convergence, although restriction to one-dimensional

structures is a serious drawback. In this paper we employed the Bloch mode scheme to show

that the excitation of surface plasmon polaritons at the entrance facet of a semi-infinite slit

array leads to a substantial reduction in the strength of the guided mode through the slits. This

behavior is quite distinct from that of the Wood anomaly, where the transition of a diffracted

order from just below to just above the horizon produces a tiny peak in the plot of T versus θ,

but does not diminish the strength of the guided mode through the slits.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Moysey Brio, John Weiner, Krishna Gundy, Philippe Lalanne, and

Hongbo Li for many helpful discussions. JVM acknowledges support from the Alexander von

Humboldt Foundation. This work has been supported by the AFOSR contracts F49620-03-1-

0194, FA9550-04-1-0213, FA9550-04-1-0355 awarded by the Joint Technology Office.

#74253 - $15.00 USD Received 22 August 2006; accepted 22 September 2006

(C) 2006 OSA 30 October 2006 / Vol. 14, No. 22 / OPTICS EXPRESS 10227

You might also like

- Surface Plasmon Polaritons On Metallic Surfaces: A. R. Zakharian, J. V. Moloney, and M. MansuripurDocument15 pagesSurface Plasmon Polaritons On Metallic Surfaces: A. R. Zakharian, J. V. Moloney, and M. Mansuripuranon_489850512No ratings yet

- Optik 73Document5 pagesOptik 73z.umul9031No ratings yet

- Wave Propagation in Step-Index Fibers: Attiq AhmadDocument42 pagesWave Propagation in Step-Index Fibers: Attiq AhmadZain ShabbirNo ratings yet

- CorrugatedDocument11 pagesCorrugatedmagsinaNo ratings yet

- Hollow Metallic and Dielectric Wave-Guides For Long Distance Optical Transmission and LasersDocument28 pagesHollow Metallic and Dielectric Wave-Guides For Long Distance Optical Transmission and LasersClaudia Lopez ZubietaNo ratings yet

- Iora IcorDocument5 pagesIora IcorteguhNo ratings yet

- Calculation of The Changes in The Absorption and Refractive Index For Intersubband Optical Transitions in A Quantum BoxDocument8 pagesCalculation of The Changes in The Absorption and Refractive Index For Intersubband Optical Transitions in A Quantum BoxWilliam RodriguezNo ratings yet

- An Analytic Solution To The Scattering Fields of Shaped Beam by A Moving Conducting Infinite Cylinder With Dielectric CoatingDocument5 pagesAn Analytic Solution To The Scattering Fields of Shaped Beam by A Moving Conducting Infinite Cylinder With Dielectric CoatingDyra KesumaNo ratings yet

- Advances in Structure Research by Diffraction Methods: Fortschritte der Strukturforschung mit BeugungsmethodenFrom EverandAdvances in Structure Research by Diffraction Methods: Fortschritte der Strukturforschung mit BeugungsmethodenR. BrillNo ratings yet

- 09 06061601 KMP TroschyoDocument14 pages09 06061601 KMP TroschyoSandip MaityNo ratings yet

- ArticleDocument13 pagesArticlerashidshahzadawanNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Propagation Characteristics Along An A PDFDocument14 pagesAnalysis of Propagation Characteristics Along An A PDFTasmiah TunazzinaNo ratings yet

- Waves in Media: Ashcroft and Mermin, Solid State Physics (Saunders College, 1976, Page 553)Document42 pagesWaves in Media: Ashcroft and Mermin, Solid State Physics (Saunders College, 1976, Page 553)Amina lbrahimNo ratings yet

- Polar EigenstatesDocument11 pagesPolar EigenstatesPeter MuysNo ratings yet

- Plane Sh-Wave Response From Elastic Slab Interposed Between Two Different Self-Reinforced Elastic SolidsDocument15 pagesPlane Sh-Wave Response From Elastic Slab Interposed Between Two Different Self-Reinforced Elastic SolidsAditya KaushikNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Modes in Optics and PhotonicsDocument6 pagesThe Concept of Modes in Optics and PhotonicsDanny AdonisNo ratings yet

- Optical Fiber Communication: An OverviewDocument32 pagesOptical Fiber Communication: An OverviewRajesh ShindeNo ratings yet

- Optik 3Document6 pagesOptik 3z.umul9031No ratings yet

- Optical TweezersDocument22 pagesOptical TweezersconcebaysNo ratings yet

- Electron-Phonon Interaction: 2.1 Phonons and Lattice DynamicsDocument14 pagesElectron-Phonon Interaction: 2.1 Phonons and Lattice DynamicsYeong Gyu KimNo ratings yet

- Casimir Effect 0506226Document10 pagesCasimir Effect 0506226Ramesh ManiNo ratings yet

- Plasmon-Polaritons and Their Use in Optical Sub-Wavelength. Event of Copper and SilverDocument7 pagesPlasmon-Polaritons and Their Use in Optical Sub-Wavelength. Event of Copper and SilverIJRAPNo ratings yet

- A Detailed Analysis of Annihilation Absorption in ?-Ray Astronomy TDocument14 pagesA Detailed Analysis of Annihilation Absorption in ?-Ray Astronomy TKamonashis HalderNo ratings yet

- Atomic Structure 10feb07Document27 pagesAtomic Structure 10feb07Fredrick MutungaNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Sheet-I Fermat's Principle and Electromagnetic WavesDocument1 pageTutorial Sheet-I Fermat's Principle and Electromagnetic Wavespriyanka choudharyNo ratings yet

- Optical Fibers: Structures, Waveguiding & FabricationDocument54 pagesOptical Fibers: Structures, Waveguiding & FabricationKhyati ZalawadiaNo ratings yet

- Optical Fibers: Structures, Waveguiding & FabricationDocument49 pagesOptical Fibers: Structures, Waveguiding & FabricationMonika SinghNo ratings yet

- Faraday Rotation Measurement Using A Lock-In Amplifier: AbstractDocument25 pagesFaraday Rotation Measurement Using A Lock-In Amplifier: AbstractFabio LimaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document28 pagesChapter 3Dean HazinehNo ratings yet

- New Compact and Wide-Band High-Impedance Surface: TheoryDocument4 pagesNew Compact and Wide-Band High-Impedance Surface: TheoryDebapratim DharaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2 - Wave Eqs (2850)Document57 pagesLecture 2 - Wave Eqs (2850)Inam ur RehmanNo ratings yet

- TEXZON Baylor Corum16Document11 pagesTEXZON Baylor Corum16Andrés Polochè ArangoNo ratings yet

- Jandieris - Temporal Power Spectrum of Scattered Electromagnetic Waves in The Equatorial Terrestrial IonosphereDocument12 pagesJandieris - Temporal Power Spectrum of Scattered Electromagnetic Waves in The Equatorial Terrestrial IonosphereOleg KharshiladzeNo ratings yet

- Call For PaperDocument9 pagesCall For PaperIJRAPNo ratings yet

- Forced Vibrations of A Cantilever Beam: European Journal of Physics September 2012Document11 pagesForced Vibrations of A Cantilever Beam: European Journal of Physics September 2012anandhu s kumarNo ratings yet

- Cavity Writeup ExpDocument7 pagesCavity Writeup ExpKr PrajapatNo ratings yet

- Free Vibration Analysis of Beams by Using A Third-Order Shear Deformation TheoryDocument13 pagesFree Vibration Analysis of Beams by Using A Third-Order Shear Deformation TheoryalokjietNo ratings yet

- Yao-Xiong Huang: of ofDocument7 pagesYao-Xiong Huang: of ofAnubhav LalNo ratings yet

- Gravitational Waves in Open de Sitter SpaceDocument17 pagesGravitational Waves in Open de Sitter SpaceKaustubhNo ratings yet

- Physics 511: Electrodynamics Problem Set #6 Due Friday March 23Document5 pagesPhysics 511: Electrodynamics Problem Set #6 Due Friday March 23Sergio VillaNo ratings yet

- Paper 3Document7 pagesPaper 3naveenbabu19No ratings yet

- Spectral Finite Elements For Vibratingrods and Beams With Random Field PropertiesDocument19 pagesSpectral Finite Elements For Vibratingrods and Beams With Random Field PropertiesMallesh NenkatNo ratings yet

- FALLSEM2021-22 ECE3010 TH VL2021220101865 Reference Material I 02-Aug-2021 Introduction FinalDocument19 pagesFALLSEM2021-22 ECE3010 TH VL2021220101865 Reference Material I 02-Aug-2021 Introduction FinalanchitNo ratings yet

- 2000 Vibration Analysis of Wire and Frequency ResponseDocument13 pages2000 Vibration Analysis of Wire and Frequency ResponseUnggul Teguh PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- Electromagnetic Vector PotentialDocument4 pagesElectromagnetic Vector PotentialAsraf AliNo ratings yet

- Optical Fibers: Structures, Optical Fibers: Structures, Waveguiding & FabricationDocument99 pagesOptical Fibers: Structures, Optical Fibers: Structures, Waveguiding & FabricationNung NingNo ratings yet

- PPCF 372627 P 15Document16 pagesPPCF 372627 P 15Alexei VasilievNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Solid State Physics PDFDocument28 pagesIntroduction To Solid State Physics PDFm4_prashanthNo ratings yet

- Index Slip.: ", - e S S " C MS., 20Document37 pagesIndex Slip.: ", - e S S " C MS., 20bezukhovNo ratings yet

- EMII2013 Chap 10 P1 PDFDocument49 pagesEMII2013 Chap 10 P1 PDFFabian ZambranoNo ratings yet

- Mock Test 1-3Document11 pagesMock Test 1-3Puneeth ANo ratings yet

- Scanning Tunneling Microscope: How Does It Work?Document19 pagesScanning Tunneling Microscope: How Does It Work?Arnau Ll-veraNo ratings yet

- Bio SavarDocument10 pagesBio SavarDang Phuc HungNo ratings yet

- Electrical Boundary Conditions: Is A Unit Vector Normal To The Interface From Region 2 To Region1Document10 pagesElectrical Boundary Conditions: Is A Unit Vector Normal To The Interface From Region 2 To Region1HFdzAlNo ratings yet

- Witten 1Document37 pagesWitten 1CGFernandez2014No ratings yet

- AP621-Lect01-Basic Electron OpticsDocument92 pagesAP621-Lect01-Basic Electron OpticsHassanNo ratings yet

- Generation and Analyses of Guided Waves in Planar StructuresDocument6 pagesGeneration and Analyses of Guided Waves in Planar StructuresIjan DangolNo ratings yet

- Review of Plane Waves, Transmission Lines and Waveguides: by Professor David JennDocument91 pagesReview of Plane Waves, Transmission Lines and Waveguides: by Professor David JennscrleeNo ratings yet

- R b (both ρDocument9 pagesR b (both ρCyrus JiaNo ratings yet

- Surface Plasmon Resonance in A Thin Metal Film: 1 BackgroundDocument10 pagesSurface Plasmon Resonance in A Thin Metal Film: 1 BackgroundPoonam Pratap KadamNo ratings yet

- Li - Wei - 2016 - Reflection and Transmission Through A Microstructured Slab Sandwiched by TwoDocument17 pagesLi - Wei - 2016 - Reflection and Transmission Through A Microstructured Slab Sandwiched by Twoadamhong0109No ratings yet

- L13 Arrays1Document21 pagesL13 Arrays1sakshiNo ratings yet

- Antennaarray ConceptnapplicatinDocument55 pagesAntennaarray ConceptnapplicatinMuhammad AbdullahNo ratings yet

- 16optical Broadband Angular SelectivityDocument4 pages16optical Broadband Angular Selectivityadamhong0109No ratings yet

- 2014-Reconfigurable Reflectarrays and Array Lenses For Dynamic Antenna Beam Control A ReviewDocument16 pages2014-Reconfigurable Reflectarrays and Array Lenses For Dynamic Antenna Beam Control A Reviewadamhong0109No ratings yet

- 2017-Intelligent Metasurface Layer For Direct Antenna Amplitude Modulation SchemeDocument13 pages2017-Intelligent Metasurface Layer For Direct Antenna Amplitude Modulation Schemeadamhong0109No ratings yet

- Classical - Electrodynamics - John - David - Jac - 3rd Edition - OCR PDFDocument834 pagesClassical - Electrodynamics - John - David - Jac - 3rd Edition - OCR PDFDaniela Tellez75% (4)

- Dual Degree Sylabus Chemistry - 200916Document87 pagesDual Degree Sylabus Chemistry - 200916hp pavilionNo ratings yet

- File 1 - 65Document4 pagesFile 1 - 65Chuah Chong Yang100% (1)

- Diffraction Physics 1Document109 pagesDiffraction Physics 1Sudarshan GopalNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 Solutions PDFDocument5 pagesAssignment 1 Solutions PDFshum kennethNo ratings yet

- Seismic EventsDocument37 pagesSeismic EventsAndres Loja100% (1)

- Physics Activity FileDocument10 pagesPhysics Activity FileOjashviji SahuNo ratings yet

- Long and Short Question and Answers OpticsDocument9 pagesLong and Short Question and Answers Opticskrishna gargNo ratings yet

- 12 Optics AssignmentDocument4 pages12 Optics AssignmentKeerthi SruthiNo ratings yet

- 11 Class Short Questions NotesDocument28 pages11 Class Short Questions NotesR.S.H84% (168)

- S.6 Physics Revision Questions - 2020Document83 pagesS.6 Physics Revision Questions - 2020Kizito JohnNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts of Mechanics, Optics and Its Applications, Ele and Qualitative Understanding of Concepts of Quantum Physics and Statistical MechanicsDocument2 pagesBasic Concepts of Mechanics, Optics and Its Applications, Ele and Qualitative Understanding of Concepts of Quantum Physics and Statistical Mechanicsankur singhNo ratings yet

- 9 - Determination of Grating ConstantDocument8 pages9 - Determination of Grating ConstantCharmaine ColetaNo ratings yet

- Physics Notes PDFDocument138 pagesPhysics Notes PDFVishak Mendon100% (1)

- Elements of X Ray Diffraction by B D Cullity PDFDocument2 pagesElements of X Ray Diffraction by B D Cullity PDFKumar Bd40% (5)

- Green Synthesis of Calcium Oxide Nanoparticles Using Murraya Koenigii Leaf (Curry Leaves) Extract For Photo-Degradation of Methyl Red and Methyl BlueDocument6 pagesGreen Synthesis of Calcium Oxide Nanoparticles Using Murraya Koenigii Leaf (Curry Leaves) Extract For Photo-Degradation of Methyl Red and Methyl BlueInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Tobias Salger Et Al - Directed Transport of Atoms in A Hamiltonian Quantum RatchetDocument4 pagesTobias Salger Et Al - Directed Transport of Atoms in A Hamiltonian Quantum RatchetYidel4313No ratings yet

- Screenshot 2022-08-24 at 4.02.25 PMDocument92 pagesScreenshot 2022-08-24 at 4.02.25 PMchituNo ratings yet

- Simple Harmonic Motion and Waves: Sunshine Series Physics Class 10Document48 pagesSimple Harmonic Motion and Waves: Sunshine Series Physics Class 10Hassan Ali Bhutta100% (1)

- L9 - (JLD 3.0) - Wave Optics - 27th October.Document56 pagesL9 - (JLD 3.0) - Wave Optics - 27th October.PpNo ratings yet

- 14.1 Wave ExercisesDocument8 pages14.1 Wave ExercisesHaha XiNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: Physics 9702/12Document24 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: Physics 9702/12Pham Thanh MinhNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: Physics 9702/12Document20 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: Physics 9702/12Trần Sỹ Minh TiếnNo ratings yet

- Course Structure - BSMS PDFDocument51 pagesCourse Structure - BSMS PDFPraveen RajaNo ratings yet

- Practice Exam 5 SolutionDocument13 pagesPractice Exam 5 SolutionNick YuNo ratings yet

- OE5170 Notes 08Document3 pagesOE5170 Notes 08dhruvbhagtaniNo ratings yet

- Wave Optics: IntroductionDocument15 pagesWave Optics: IntroductionChandra sekharNo ratings yet

- Distance Learning Programme: Pre-Medical: Leader Test Series / Joint Package CourseDocument48 pagesDistance Learning Programme: Pre-Medical: Leader Test Series / Joint Package Courseunacademy neetNo ratings yet

- 1st-1st Sem-2022qDocument24 pages1st-1st Sem-2022qAnshuman BanikNo ratings yet

- Electron Diffraction TubeDocument4 pagesElectron Diffraction TubeIch Habe KopfschmerzenNo ratings yet