Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Assimilation of The Sámi Its Unforeseen Effects On The Majority Populations of Scandinavia

Uploaded by

FRAGAOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Assimilation of The Sámi Its Unforeseen Effects On The Majority Populations of Scandinavia

Uploaded by

FRAGACopyright:

Available Formats

Assimilation of the Sámi: Its Unforeseen Effects on the Majority Populations of

Scandinavia

Author(s): John Weinstock

Source: Scandinavian Studies , Vol. 85, No. 4 (Winter 2013), pp. 411-430

Published by: University of Illinois Press on behalf of the Society for the Advancement

of Scandinavian Study

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/scanstud.85.4.0411

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/scanstud.85.4.0411?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Society for the Advancement of Scandinavian Study and University of Illinois Press are

collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Scandinavian Studies

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Assimilation of the Sámi:

Its Unforeseen Effects

on the Majority Populations

of Scandinavia

John Weinstock

University of Texas

T

he Sámi have been subject to relentless assimilation efforts for

centuries.1 Assimilation took different forms, overt and covert,

depending on which nation-state the Sámi happened to inhabit.

What were the results of the ruling authorities’ attempts to get the

Sámi to meld into the majority populations? There are perhaps 80,000

Sámi in the four nations where they live today; some scholars suggest

that up to ten times that number were assimilated. Many studies have

illustrated the effects on the Sámi, but few have shown how assimila-

tion impacted Finns, Norwegians, and Swedes. I demonstrate first

that assimilation has been going on much longer than mid-nineteenth

century to about 1980, during which the main effort focused on Sámi

children in transitional areas where they dwelt among others. They

were forced to attend boarding schools where they were not allowed

to speak their mother tongue, thus threatening not only their language

but their culture. Then I investigate what became of those assimilated

and what sort of relationship there was/is to non-Sámi. Here the

answers are in many ways surprising. For example, intermarriage was

quite common, and this led to admixture (mixing of ancestral, previ-

ously relatively isolated populations) in ensuing generations. Today’s

Scandinavians may not be aware of how much Sámi DNA they carry.

1. Sámi is normally spelled Saami in Sweden, and in Norway with or without the

accent, Sámi and Sami. The endonym, or what the people call themselves, is Sámi. The

exonym Lapp dates back to Viking times and became a derogatory term in later years.

See Hansen and Olsen (2007, 47–51).

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

412 Scandinavian Studies

Recently I showed that today’s Sámi population in Scandinavia is

genetically heterogeneous; the genetic profile of Sámi in Troms, for

example, is significantly different from the genetic profile of Sámi in

eastern Finland (Weinstock 2010, 31–45). Though there were migra-

tions into the area after the Last Glacial Maximum, they came from

many directions, along different routes and at various times and rates

depending on where the glaciers disappeared earliest, ecological fac-

tors, and the nature of the flora and fauna. The goal of the present

effort is to broaden the focus, to consider in more detail population

and genetic data for all of the Nordic countries and how assimilation

affected the current majority peoples, Finns, Norwegians, and Swedes.

Phylogeography2 has evolved rapidly in recent years with analyses

based on genome-wide sequencing and allowing new interpretations

previously impossible with classical population genetics.

In nature, humans have generally been gregarious: when members

of one group meet strangers, they communicate; trade; borrow words,

ideas, or technologies from one another; and they frequently marry

outside their ethnic group and often exchange genes. Such cultural

contacts can be seen, for example, in the Venus figurines widespread

over Central and Eastern Europe after 30,000 years ago (Hoffecker

2005, 87). Social networks were much larger than one might imagine.

One should keep in mind when dealing with today’s Nordic peoples

that they are defined primarily on the basis of ethnicity, especially their

mother tongue. In the case of the Sámi, this leads to problems, since

most of the available Sámi genetic data were sampled from those who

“consider” themselves to be Sámi.3 Not included are the many “Sámi”

who were assimilated by the nation-states in the nineteenth century

and first half of the twentieth century, or even earlier, and who left

their Sámi ethnicity behind—but not their genes—when they moved

away to metropolitan areas such as Helsinki, Oslo, or Stockholm: do

the genetic analyses of the majority populations take this into account,

and, if so, what role does this factor play in the results?

2. The study of the historical processes that may be responsible for the contemporary

geographic distributions of individuals.

3. The Sámediggi (Norwegian Sámi parliament) has the following definition for

the approximately 80,000 Sámi in Sápmi: “Everyone who declares that they consider

themselves to be Sámi, and who either has Sámi as his or her home language, or has

or has had a parent, grandparent, or great-grandparent with Sámi as his or her home

language, or who is a child of someone who is or has been registered in the Sámi census,

has the right to be enrolled in the Sámi census in the municipality of residence.” See

http://www.galdu.org/govat/doc/eng_sami.pdf.

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Assimilation of the Sámi 413

Paleolithic Settlement in Eurasia

and the Last Glacial Maximum

Did modern humans move westward from Central Asia to Europe

during the Paleolithic? One might think that humans arrived in Europe

before northern Eurasia due to the latter’s sparse human habitation,

and its colder and drier climate; surprisingly, that does not seem to be

particularly accurate. Modern humans settled relatively rapidly in many

areas of Eurasia: new radiocarbon curves in the range of 25,000–50,000

BP4 suggest a much speedier dispersal of human populations than origi-

nally thought (Mellars 2006, 933). Between 45,000 and 24,000 years

ago, they reached 71° north latitude, or further north than Europe’s

highest point, Nordkapp.

The post-glacial colonization of Scandinavia began early, from any

direction where the Fennoscandian peninsula was accessible: from

the west, the Ahrensburg cultures, Hensbacka on the west coast of

Sweden, then Fosna on the southwest coast of Norway, and finally

Komsa along the northwest coast of Norway; from the east, the Post-

Swiderian tradition of northeast Russia. The archaeologists Tuija

Rankama and Jarmo Kankaanpää speak about an Early Mesolithic,

non-hostile interface zone in eastern Finnmark and northern Finnish

Lapland between the western (Komsa) and eastern traditions by c.

10,000 BP (Rankama and Kankaanpää 2011, 183, 205–7). What were

the humans arriving in Scandinavia like, and when and from whence

did they come? In fact, the genetic analyses of the Sámi, though based

on very recent samples, suggest that admixture from the mixing of

ancestral, previously relatively isolated populations followed by range

expansion or migration has been the norm for many millennia. To cite

but one example of contact between Sámi, or rather Sámi forebears,

and others, Pekka Sammallahti discusses the history of Finno-Ugric

loanwords from Proto-Indo-European (PIE): it begins c. 5,000 BCE

when Sámi and Samoyed share around 100 stems, a number of which

were borrowed from PIE (Sammallahti 1998, 118). Implicit in this

extensive contact between language groups is the intermarriage and

admixture that occurred.

And when did farming come to Fennoscandia? Conventional

wisdom would have agriculture coming to the south coast of Finland

4. All prehistoric dates in this paper are approximate and given in 14C BP (Before

Present).

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

414 Scandinavian Studies

and south Sweden around 5,300 BP, mainly via cultural diffusion:

“When farming arrived in the north along with Indo-European lan-

guages the peoples remained largely the same, adopting Germanic,

Baltic or Slavic languages, or they kept their Finno-Ugric tongues”

(Weinstock 2010, 34–35). Pontus Skoglund et al. found the DNA

from 5,000-year-old bones of three hunter-gatherers to be signifi-

cantly different from the DNA in comparably aged remains of one

farmer, hence suggesting demic diffusion.5 A closer examination of

the genetic data can shed some light on these and other issues, but

first a closer look at assimilation.

Assimilation

No one denies the existence of long-term, indefatigable efforts to

assimilate the Sámi—and the Kvens6 of Norway—into the mainstream

cultures of Scandinavia. When did assimilation occur, and what was its

impact on the Sámi and, for that matter, on Norwegians, Swedes, and

Finns? During the nineteenth century, nationalism was the prevalent

ideology; Norway and Sweden focused on state building. Henry Minde

gives 1850–1980 for Norwegianization (fornorsking), the government-

sponsored program in Norway to turn the Sámi and Kvens into reliable

Norwegian citizens (Minde 2003, 6). A multifaceted series of actions

were implemented to deprive the Sámi of their language and culture,

most importantly, boarding schools for Sámi children, subsidizing

colonization (settlers) in Sámi territory in the north, and restricting

property ownership to those who mastered the Norwegian language

and had a Norwegian name (many Norwegian Sámi today have two

names). This effort was aimed especially at those living in transitional

or mixed areas such as the sea/coastal Sámi, areas where there were

also many Norwegians.

Lars Elenius points out that in Sweden the focus was rather on

segregation (2002, 105). During much of the nineteenth century,

a paternalistic attitude toward the “Sámi” prevailed in the Swedish

Riksdag: Sámi were slowly dying out, allegedly because they were at

a lower stage of evolution and could not successfully compete with

5. See Skoglund et al. (2012) who argue in favor of migration of farmers into Fen-

noscandia.

6. Finnish settlers in Northern Norway and their descendants. Originally from the

Gulf of Bothnia coming as agriculturalists to Troms and Finnmark mainly from the

eighteenth century on.

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Assimilation of the Sámi 415

Swedish farmers. According to Lennart Lundmark, the Riksdag felt

its duty was to delay the demise of reindeer herding (2002, 31, 40).

By the end of the century, “lapp skal vara lapp” (Sámi shall be Sámi)

became governmental policy, meaning that Sámi reindeer herders

were to be isolated from the majority population (Lundmark 2002,

63–75). An odlingsgräns (cultivation boundary) had been proposed at

the beginning of the nineteenth century with reindeer herders north of

the boundary, farmers south (Lundmark 2006, 135–61). After years of

discussions, this boundary was implemented in 1890; it also included

hunting and fishing rights for the Sámi. But the flow of farmers settling

north of the cultivation boundary continued unabated, and settlers/

farmers felt free to hunt and fish on land reserved for the Sámi. Other

bizarre proposals were enacted: reindeer herders were not allowed

to supplement their herding income through a mixed economy with

small-scale agriculture, fishing, or the like; they were not to live in

“ordinary” houses but in traditional turf huts or tents. Oddly, those

Sámi not involved in herding lost their ethnic identity: by law, they

were now Swedes!

These Norwegian and Swedish policies were deliberate; though

created through different means and with different ends in mind, they

served to assimilate Sámi into their respective nations and cultures.

But was there no assimilation before the nineteenth century? In her

MA thesis, Bente Persen argues that the roots of Norwegianization

lay in the missionary period of the eighteenth century, with the

(Lutheran) Church and the Sámi mission collaborating to eradicate

the Sámi pre-Christian worldview (Persen 2008). Placards issued

by the Swedish Crown in the late seventeenth century encouraged

agricultural settlement on Sámi lands. As Veli-Pekka Lehtola points

out, many Sámi became colonists on their own tax lands and were

even considered to be “Finns”; their new farms were registered with

Finnish names, which then became the surnames of their descendants

(Lehtola 2004, 31–2). The Strömstad treaty of 1751, setting the border

between Norway and Sweden, forced the Sámi to choose between

Norwegian and Swedish citizenship. As early as the fourteenth century,

the Birkarls (Finnish merchants) received royal franchises for trading

and collecting taxes from the Sámi. The above examples are but a few

of many that suggest an unintentional, often clandestine assimilation

of the Sámi underway for many centuries.

Over the long haul, the harsh measures of the nineteenth and

twentieth centuries were successful. Racism and social Darwinism

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

416 Scandinavian Studies

tainted much of what occurred. For example, Johan Evert Rosberg

measured a group of Sámi in Finnish Lapland in 1910. He claimed he

could distinguish between nomadic and coastal Sámi, with the former

being the racially purest group: “[T]hey are still original Mongolian

Lapps,” and by implication, inferior (Rosberg 1910). Boarding schools

(Nor. internat, Swed. nomadskolor) were particularly effective in the

assimilation effort. Sámi children were taken from their parents and

put in schools where they were not allowed to speak their mother

tongue (Lehtola 2004, 44–6; Lundmark 2006, 76–94). The Sámi

language in Norway was strongest in the so-called core areas such as

Kautokeino and Karasjok in mid-nineteenth century. Here there were

fewer Norwegians percentage-wise than in transitional areas; these core

areas were best able to resist Norwegianization until the Second World

War. However, a new difficulty cropped up for Sámi language toward the

end of World War II. Many Sámi in transitional communities in Norway

and Finland were evacuated to the south. While there—sometimes for

more than a year—they tended to speak Norwegian or Finnish and

continued to do so when they returned home (Trosterud 2008, 97).

So, many coastal Sámi simply disappeared from the census records; a

good example of this is Kvænangen in Norway, where according to

Ivar Bjørklund, the proportion of Sámi went from 44 percent to zero

between 1930–50 (Minde 2003, 24).

The pressure to assimilate was substantial. In his article on the coastal

Sámi and their problems with the Norwegian fisheries, Einar Eythórsson

illustrates the dilemma they faced. The Norwegian majority considered

the fjord fishermen a pariah caste and ignored their interests because

the coastal Sámi were unable to communicate their collective identity

(Eythórsson 2003, 157). “Being Sámi was not [considered] to be a

legitimate basis for interaction” (Nilsen 2003, 168). If they chose to

assimilate, they could escape the pariah role, but this would eliminate

any possibility of engaging the majority and reacting collectively to

the exercise of power against them. To make inroads against domina-

tion, they had to break the taboo of coastal Sámi identity, but this was

emotionally painful for them. Although the Norwegians have granted

the Sámi a voice in the fisheries arena over the past decade, little has

been achieved.

In the face of the relentless assimilation pressure, many Sámi were

marginalized; they capitulated, moved away from Sápmi, and aban-

doned their ethnic identity. It is difficult to estimate how many Sámi

became assimilated, in part because the few studies carried out have

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Assimilation of the Sámi 417

been limited to local areas. And, as Minde points out, it was individu-

als who were assimilated, individual Sámi who felt fear and shame and

were not eager to talk about their experiences. In 1978, Vilhelm Aubert

Båkt’e published his comprehensive analysis of the Sámi in Northern

Norway, Den samiske befolkning i Nord-Norge. The data came from a

supplementary survey to the 1970 census. He writes: “Sámi who live in

Southern Norway or in cities in Troms and Nordland, fall outside the

scope of the census.” He continues: “Vi har få opplysninger fra andre

kilder som sier noe om deres antall og sammensetning for øvrig. Et

forsøk på å kartlegge samer i Oslo kunne tyde på at Oslo er en av de

større samekommunene i landet” (Båkt’e 1978, 17) [For that matter,

we have little information from other sources saying anything about

their number and composition. An attempt to map the Sámi in Oslo

might indicate that Oslo is one of the larger Sámi communities in the

country]. In other words, there is almost no information about Sámi

who have left traditional Sámi areas and become assimilated in the

south. A similar situation prevailed in Sweden and Finland.

Lars Ivar Hansen and Bjørnar Olsen write: “[F]angstbefolkningen i

nordre Fennoskandia [velger] å adoptere samisk etnisitet, fordi dette er

økonomisk fordelaktig” (Hansen and Olsen 2007, 34) [(T)he trapper

population in northern Fennoscandia (chooses) to adopt Sámi ethnicity,

because this is economically advantageous], and a bit later: “det [gir]

mening å snakke om samisk etnisitet . . . fra slutten av siste årtusen

f.Kr. . . . [når vi kan] for første gang dokumentere at fangstsamfun-

nene i det indre, nordre og østlige Fennoskandia var involvert i mer

omfattende eksterne transaksjoner” (Hansen and Olsen 2007, 41) [it

(makes) sense to speak about Sámi ethnicity . . . from the end of the

last millennium BC . . . (when we can) for the first time document that

the trapper communities in inner, northern and eastern Fennoscandia

were involved in more extensive external transactions]. These social

and economic transactions were buttressed by marriage alliances and

kinship ties. How might this be demonstrated? Until relatively recently

there has been very little statistical data on this issue. According to

Båk’te’s 1970 census analysis, mixed marriages make up approximately

20 percent of all marriages in Sámi core areas but 80 percent of all

marriages in the rest of Northern Norway (Båk’te 1978, Tables 12–13).

If there were so many mixed marriages in Northern Norway, how many

were there in the south where so many Sámi had become assimilated?

Trond Trosterud discusses the effects of mixed marriages on the sur-

vival of Sámi language (2008, 101). Marriage between Sámi-speaking

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Af on Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

418 Scandinavian Studies

and Norwegian-speaking partners often led to a loss of Sámi language.

These ethnically mixed, child-producing relationships have left traces

in the genetic profiles of many contemporary Scandinavians.

Scandinavian Phylogeographic

Data I: mtDNA

The frequency distribution of mtDNA (maternal) haplogroups7 in

Fennoscandia and Europe as a whole is laid out in Table 1.8 (Super)

haplogroup U consists of the subclades9 U1-U8; U originated in

Western Asia from haplogroup R in the form of a common female

ancestor. Haplogroup U5 and its subclades U5a and U5b, though found

throughout Europe, have their highest concentrations in the far north,

in Estonians, Finns, and Sámi. U5b1b, including U5b1b1, the so-called

“Sámi motif,” is very old and goes back to the Franco-Cantabrian

glacial refuge where it spread after the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM)

to Eastern Europe and then to the north and west to Fennoscandia.10

Martin Richards et al. give an age range for U in the Early Upper

Paleolithic at c. 50,000 BP. For Scandinavia as a whole, they suggest

that 79.3 percent of the migration events are Paleolithic, 11.7 percent

Neolithic, and 7.4 percent Bronze Age/recent (Richards et al. 2000,

1266, 1268). Haplogroup K is descended from the U8 subclade and

goes back approximately 12,000 years.

H is easily the largest haplogroup in Europe, as evident in Table 1,

though much less frequent among the Sámi.11 Subclades H1 and H3 as

well as sister haplogroup V took refuge during the LGM in the Franco-

Cantabrian area, while other subclades of H went to the Ukrainian

and Italian refuges after the LGM carriers of H1 headed north from

the Iberian refuge and crossed the North Sea—at this time a narrow

body of water—to southwestern Sweden and southern Norway in

7. A haplogroup is a group of haplotypes that share a common ancestor.

8. For the complete phylogenetic mtDNA tree, see http://www.phylotree.org.

9. A clade may be thought of as a branch on the “tree of life.”

10. During the LGM, the extreme cold forced humans (and most flora and fauna) to

retreat to warmer areas, glacial refuges. In Europe these were the Franco-Cantabrian

between France and Spain, northern Italy, Balkan Peninsula, and the Ukrainian near

the Black Sea. See Tambets et al. (2004, 677).

11. Superhaplogroup HV and its descendants H and V originated in Western Eurasia

some 30,000 years ago when one branch of HV ancestors moved north across the

Caucasus and then north and west. Richards et al. (2000) give an age range for HV,

the parent of V, of Middle Upper Paleolithic.

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Assimilation of the Sámi 419

Table 1. Contemporary mtDNA Data for the Nordic Countries

Country\

Haplogroup U5 K H V T Z

Finland

Finland1 27.5 6.5 40 4.5 (HV0) 6 1.56

Finland2 27.9 2.5 40.1 5.1 2.5 2.5

Central Finland3

Northern Ostrobothnia 34 3 34 6 8

Kainuu 36 2 37 9 1

Country\Haplogroup U K H V T Z

Northern Savo 17 4 53 4 1

Central Ostrobothnia 25 3 39 3 0

Southern Finland1

Häme 16.7 13.3 43.3 6.7 (HV0) 6.7

Karjala 43.3 3.3 30 3.3 (HV0) 3.3

Pohjanmaa 33.3 6.7 40 6.7 (HV0) 3.3

Satakunta 23.3 0 46.7 10 (HV0) 6.7

Savo 26.7 3.3 43.3 0 6.7

Varsinais-Suomi 13.3 13.3 33.3 3.3 (HV0) 10

Karelia 2

26.9 1.6 46.7 5.5 3.8 .4

Norway4 16 29 4 9 .66

Sápmi--Norway5 56.8 0 4.7 33.1 .4 0

Norway6 57.6 4.7 33.1 .4 0

Finland 5

40.6 0 2.9 37.7 0 7.2

Finland6 43.5 0 2.9 37.7 0 7.2

N. Sweden5 35.5 0 2.6 58.6 .7 .7

S. Sweden5 18.8 9.4 34.8 18.1 2.2 4.3

S. Swed. Traditional5

23.9 4.3 15.2 37 2.2 10.9

S. Swed. Non-traditional5 16.3 12 44.6 8.7 2.2 1.1

Sweden6 26.5 3.1 68.4 0 1.0

Sweden2 21 7.5 45.6 1.3 10.1 .3

Sweden 7

17.9 5.9 41.2 2.8 7.8 .46

Norrland7 25.8 4.5 39.2 2.6 5.2 .4*

Svealand7 18.3 5.6 39.3 2.2 7.5 1.1*

Götaland7 14.2 6.7 39.6 3.4 9.1 .9*

Continental Europe5 2.6 9.3 46.9 4.4 10.8 0

Notes: Empty cell = no data for this haplogroup. * = C in 7; CZ (C, Z); in 2 C = .3, Z = .3,

hence, C in 7 might be in part Z. Sources: 1Hedman et al. 2007; 2Lappalainen et al. 2008;

3Meinilä et al. 2001; 4Passarino et al. 2002; 5Ingman and Gyllensten 2007; 6Tambets et al. 2004;

7Lappalainen et al. 2009; Meinilä et al. (2001) point out that much of what had been assigned to

macrohaplogroup M and haplogroup V belonged to haplogroup Z.

the early Mesolithic (see Glørstad et al. 2012; and Spinney 2012). V

descendants seem to have followed a similar path as U5b1b, moving

to Eastern Europe and then northwest to Fennoscandia (Tambets et

al. 2004, 676). Richards et al. estimate the age of H at approximately

16,500 (2000, 1266). Eva-Liis Loogväli et al. provide coalescence

ages for haplogroup H subclusters ranging from 23,800 to 6,000 BP

(2004, 2014). Haplogroup T, which appeared about 10,000 BP, is

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

420 Scandinavian Studies

common in eastern and northern Europe. It is also found in the Indus

Valley and the Arabian Peninsula, and may be tied to the Neolithic

expansion of farmers.

Haplogroup Z stems from Central Asia between the Caspian Sea

and Lake Baikal. It has its highest frequency in Russia and among

some Sámi groups. The Sámi Z lineage shares a common ancestor

with groups in Finland and the Volga-Ural area of Russia and must

be quite recent (2,700 BP) because it differs from Northeast Asian Z

representatives (Ingman and Gyllensten 2007, 115, 119). In a forth-

coming paper (Weinstock), I argue that Z was brought to southern

Finland by Pre-/Proto-Sámi groups at the onset of the Iron Age who

then moved throughout inland Fennoscandia assimilating the Palaeo-

European hunting bands already there.

Clio Der Sarkissian et al., analyzing ancient mtDNA (aDNA) from

c. 7,500 BP and 3,500 BP, recently found high frequencies of U (incl.

U5a) in the earlier, Mesolithic samples but more C, D, and Z in the

later Early Metal Age individuals. Hence, there must have been post-

Mesolithic migrations as well as genetic influx from central/eastern

Siberia (Der Sarkissian et al. 2013, 1, 11).

What can be gleaned from the mtDNA table (Table 1)? First of all,

haplogroup U, which includes the so-called Sámi motif U5b1b1, displays

significant variation both within the majority populations of Scandinavia

as well as within the various Sámi groups—see Map 1 for the Sámi varia-

tion. There is a cline or geographical gradient running north to south

with the highest U in the north: among majority Swedes, the frequency

is 25.7 percent in Norrbotten, falling to 14.8 percent in Götaland; the

frequency goes from 57.6 percent for Norwegian Sámi to 18.8 percent

for Southern Swedish Sámi nontraditional (do not herd reindeer). Finns

and Karelians have a frequency of roughly 27 percent. The Norwegian

U frequency is 16 percent. Comparing this to the Continental European

U frequency of 2.6 percent, a substantial amount of admixture—mixing

or mingling blood—can be seen among all the Scandinavian popula-

tions. How is this to be explained? Maria Meinila et al. conclude: “The

high frequency of certain mtDNA haplotypes considered to be Saami

specific in the Finnish population suggests a genetic admixture, which

appears to be more pronounced in northern Finland” (Meinila 2001,

160). Max Ingman and Ulf Gyllensten attribute admixture among

southern Swedish Sámi to their stratification on the basis of occupation

(2007, 117). The extent of the admixture in the majority populations

adumbrates assimilation as discussed above. The most suitable outcome

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Assimilation of the Sámi 421

for many Sámi was internal migration to majority areas. Often this

led to intermarriage and the subsequent exchange of genes. Genetic

studies of the majority Scandinavian populations do not often discuss

this issue. For example, Giuseppe Passarino et al. collected their DNA

from seventy-four young men drafted into the Norwegian army. They

do not go into details about their sample in the extensive discussion of

their results (Passarino et al. 2002, 522–6, 528). But there are hints in

the literature: Tuuli Lappalainen et al. mention the special relationship

between Norrland and Northern Finland as well as Finnish immigrants

in Eastern Sweden (2009, 62, 71). In Norrland approximately 10 percent

of the population is made up of Sámi (Lappalainen et al. 2009, 62).

Addressing language shift from Sámi to Norwegian, Trosterud writes:

“[T]he number of mixed marriages for the different areas gives rise to

a 17% language shift in the inner core area, a 47% shift in the outer core

area, and 75% language shift elsewhere” (2008, 101). In other words,

language shift occurs mostly in families where one parent speaks Sámi

and the other Norwegian, especially where the mother is Norwegian.

Assuming a population of approximately 1.5 million in Norrland, 10

percent would be Sámi or approximately 150,000. Multiplying this by

the 47 percent of Trosterud’s language shift percentages would suggest

there are about 70,000 mixed marriages in Norrland alone. Lappalainen

et al. do discuss (internal) migration: “The Swedish population has . . .

been shaped by internal migration from remote regions to large cities”;

they add: “[T]he biggest cities harbored clear traces of immigration from

all over the world” (2009, 62). When sampling majority populations of

the countries where the Sámi reside, it would seem essential to consider

their recent and earlier socio-political history.

Haplogoup K distribution is clinal in Finland and Sweden, with

smaller frequencies to the north, though the sample size is possibly

not statistically significant for Finns. Haplogroup H, the most common

mtDNA haplogroup in Europe at an average frequency of 46.9 percent,

is, as expected, much lower among Sámi except for Southern Swedish

nontraditional Sámi. The frequency of H among Norwegians is rather

low at 29 percent; whether this is due to sample size or admixture

cannot be determined from the available data. Haplogroup V, on the

contrary, has a high frequency among Sámi groups except for Southern

Swedish nontraditional Sámi and shows clinal behavior, highest in the

north and lowest in the south. V among the Sámi is primarily due to

expansion from the Franco-Cantabrian glacial refuge through central/

eastern Europe (Tambets et al. 2004, 676).

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

422 Scandinavian Studies

Map 1. Sámi mtDNA. (Norga = Norway; Ruoŧŧa = Sweden; Suopma = Finland; Guoládat

= Kola peninsula of Russia; Gárjil = Karelia in Russia).

T has its highest frequencies in Southern Scandinavia where farming

first arrived. Though T is present during the Paleolithic, it arrived in

Eurasia from the southeast beginning 10,000 BP and is mainly thought

of as a Neolithic agro/pastoralism expansion. Haplogroup Z originated

in Siberia and spread from there in several directions. The spread west-

ward was originally thought to have come to a halt around the Ural

Mountains, but Ingman and Gyllensten found substantial frequencies

of Z among the Finnish Sámi and Southern Swedish traditional Sámi,

suggesting that some Sámi lineages shared a common ancestor with

lineages from the Volga-Ural region as recently as 2,700 years ago

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Assimilation of the Sámi 423

(2007, 115, 119).12 Yet, the distribution of Z throughout Scandinavia

seems to have implications beyond its presence in the Sámi. Although

the percentages of Z in the majority populations are quite small, rang-

ing from .3–.4 percent for Sweden to 2.5 percent for Finland, this

compares to no Z whatsoever in Germany, Poland, the Balkans, and

all of Western Europe (Lappalainen et al. 2008; Tambets et al. 2004).

Hence, the Finns, Norwegians, and Swedes likely acquired Z through

assimilation of the Sámi and subsequent admixture. Looking at the

numbers, a very crude estimate of the number of Swedes carrying Z

mtDNA is 275,000, which is at least an order of magnitude greater

than the number of Sámi in Sweden.

Scandinavian Phylogeographic

Data II: Y-Chromosome

The frequency distribution of Y-chromosome haplogroups in Fen-

noscandia and Europe as a whole is laid out in Table 2.13 The main

haplogroups represented are I1, N1c (the old N3) and R1. Haplogroup I1

is common in Europe and has its highest frequency in Scandinavia and

the Balkans. It originated at the beginning of the LGM some 22,000

BP, probably when some groups went to the Ukrainian refuge near the

Black Sea and others to the refuge in the Balkans. Michael Hammer and

Stephen Zegura give an age of mutation for I at 5,950±2,450 (2002,

314). Siiri Rootsi et al. have times since divergence of 15.9±5.2 for I1a,

10.7±4.8 for I1b* and 14.6±3.8 for I1c (2004, 135). When the ice began

to melt, those carrying the I haplogroup expanded to the northwest

in the form of three subclades I1a (most common in Scandinavia), I1b

(common in the Balkans and Eastern Europe), and I1c (which has its

highest frequency in Germany at approximately 11 percent). “[C]lade

I is widespread in Europe and mostly absent elsewhere.”14

Haplogroup N first appeared in Southeast Asia 15,000–20,000 BP,

and today it is “mainly found in Northern Eurasia but is absent or

only marginally present in other regions of the globe.”15 The subclade

12. See Weinstock, “At the Frontier: Sámi Linguistics Gets a Boost from Outside”

(forthcoming), for a discussion of a possible connection between Haplogroup Z1a and

the Proto-Sámi language.

13. For the latest phylogenetic Y-chromosome tree, see http://www.isogg.org/tree.

14. Karafet et al. (2008, 834), under Clade I. The approximate dates for I and R are

given in Table 1 in Karafet et al. (2008).

15. Karafet et al. (2008), under Clade N.

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

424 Scandinavian Studies

Table 2. Contemporary Y-chromosomal Data for the Nordic Countries

Country\Haplogroup I1 N1c R1a R1b

Finland1 28.9 63.2 7.9

Eastern Finland3 19.7 70.9 5.9 2.6

Western Finland3 41.3 41.3 8.7 5.2

Österbotten4 20 65 7.5 2.5

Karelia3 17.5 53 25 .8

Norway1 40.3 6.9 23.6 27.8

Country\Haplogroup I N1c R1a R1b

Norway5 37.3 3.8 26.3 31.3

North Norway5 34.7 10.6 27.1 26.8

Middle Norway5 39.7 trace 31.5 27.1

South Norway5 42.1 trace 13.2 44.7

Sápmi--Sámi1 25.9 47.2 11 3.9

Finnish Sámi1 40.6 55.1 2.9 1.4

Kola Sámi1 17.4 39.1 21.7 8.7

Swedish Sámi1 31.4 37.1 20 5.7

Swedish Sámi4 31.6 44.7 15.8 7.9

Sweden3 37.5 14.4 24.4 13.1

Sweden1 48.2 2.8 18.4 22

Sweden2 45 5.9 15.7 20

Sweden4 37.5 9.5 11.8 23.6

Norrland2 48.8 6.5 13 16.3

Västerbotten4 41.4 19.5 12.5 15

Svealand2 41.4 7.9 13.2 19.8

Gotland4 50 10 12.5 15

Götaland2 47.5 3.6 14.2 21.6

Notes: Empty cell = no data for this haplogroup. Sources: 1Tambets et al. 2004; 2Lappalainen

et al. 2009; 3Lappalainen et al. 2008; 4Karlsson et al. 2006; 5Dupuy et al. 2006; Dupuy et al.

have P*(xR1a) and BR(xDE, J, N3, P) as two of the four major Y-chromosomal haplogroups in

Norway. The former is mainly R1b and the latter mainly I1b. The figures for Continental Europe

are a very crude estimate that does not take population size into consideration.

N1c1 is especially frequent among Finns and Lithuanians. It is likely

that the carriers of maternal haplogroup Z also carried N1c1 when

they arrived in southern Finland (cf. above under Z). Rootsi et al.

give a convergent time estimate for N (with data combined from the

old designations N1–N3) of 19.4±4.8 (evolutionary time) and 5.8±1.4

(pedigree-based time) (see Rootsi et al. 2004, 135).16 Haplogroup R

dates back to just after the onset of the last ice age at 26,800 BP. The

subclade R1a is most common in the Eurasian steppe and may have

emanated from the Ukrainian refuge. Subclade R1b expanded from

16. Pedigree-based rates are about ten times faster than coalescent/evolutionary rates.

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Assimilation of the Sámi 425

the Franco-Cantabrian refuge after the LGM and is very common

in Western Europe, among other areas. The coalescent time for R is

16,300±4,430, according to Hammer and Zegura (2002, 314).

What patterns can be observed? In the case of I, there appears to

be a cline running northeast to southwest with the highest values

generally to the southwest: Western Finland with a frequency of 40

percent, Gotland 45 percent, and South Norway 42.1 percent, though

Norrland in Sweden is an exception, perhaps due to ethnic association

with Northern Finland (Lappalainen et al. 2009, 62). The figures for

the Western Finnish Sámi and Swedish Sámi are c omparable to those

Map 2. Sámi Y chromosomes. (Norga = Norway; Ruoŧŧa = Sweden; Suopma = Finland;

Guoládat = Kola peninsula of Russia; Gárjil = Karelia in Russia).

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

426 Scandinavian Studies

for the majority populations, whereas Eastern Sámi in Kola and the

Karelians are significantly lower. Croats, Germans, and Hungarians

also have relatively high levels of I. Map 2 displays Sámi Y chromo-

somal variation.

Haplogroup N seems to have arisen in Northern China/Mongolia,

from where it spread into Siberia and the Baltic. Its descendant N1c

is widespread in the Baltic region and was brought by small groups

of males speaking an early Uralic language. Lappalainen et al. speak

of “migration waves to the Baltic Sea region” (2008, 337). There is a

clear distinction between the Eastern Finns and the Sámi versus those

living further to the west, with the former having high values of N1c.

Österbotten in Western Finland, though, has a very high frequency

too; this could be related to contacts with Norrland as above. North

Norway has a higher value than most other majority groups, with the

exception of Finland, and this may be due to admixture with the Sámi.

Three areas of Sweden show fairly high values with an east-west cline,

3.6 percent for Götaland to the south and 7.9 percent for Svealand,

just north of Götaland, and Gotland off the east coast of Sweden

with 10 percent. Surprisingly, perhaps, the figure for Norrland is only

6.5 percent whereas Västerbotten has 19 percent. Lappalainen et al.

suggest historical ties to Finland where N1c is very common (2008,

70). Berit Myhre Dupuy et al. mention that the Y-chromosome N3

(N1c) in Norway “is observed at 4% in the overall population and

at 11% in the northern region corresponding to 150,000 and 50,000

inhabitants, respectively (2005, 6). These numbers exceed the total

number of Saami inhabitants.” Dupuy et al. continue: “There is thus

a considerable pool of Saami and/or Finnish [Kven] Y-chromosomes

in the Norwegian population and particularly in the north” (2005, 6,

8). Four percent of Norway’s population of approximately 5 million

would be 190,000, the number of Norwegians carrying N1c. The R1a

frequency is lowest among the Finns and the Sámi, though the Kola

Sámi and the Swedish Sámi have values comparable to most of the

majority population in Sweden. R1a is highest in Middle and North

Norway with South Norway similar to most of Sweden, but there

are insufficient data to come to any firm conclusions. R1b has a much

higher frequency in Southern Norway than in Sweden; this might

indicate some admixture between the Swedes and Sámi of Sweden.

A few scholars have rightly urged caution interpreting genetic data.

After all, most DNA samples come from living humans, and yet con-

clusions are drawn about what happened thousands of years ago. The

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Assimilation of the Sámi 427

Sámi as well as the other Nordic populations are quite small and were

relatively isolated; this can lead to genetic drift17 skewing the results.

The studies cited in this paper take pains to deal with this issue. Another

factor working in favor of the genetic analyses is that ancient DNA

is now being successfully retrieved and analyzed (cf. Skoglund et al.

2012, as one example).

Conclusions

Geographical heterogeneity among the Sámi is readily apparent

in the mtDNA and Y-chromosomal data in the tables above; such

heterogeneity is also to be found among the majority populations in

Scandinavia. Compare with Maps 1 and 2. Discussing the Norwegian

population, Dupuy et al. observe that the “[h]eterogeneity in major

founder groups, geographical isolation, severe epidemics, historical

trading links and population movements may have . . . contributed to

the observed regional differences in distribution of haplotypes within

two of the major haplogroups” (2006, 1). Ingman and Gyllensten

(2007, 117) present one of the best examples to date of admixture,

namely the Southern Swedish Sámi nontraditional who are much

more “Swedish” than Sámi. This heterogeneity surely had much to

do with the harsh, official Norwegian assimilation policy, the Swedish

segregation policy that led to many Swedish Sámi being assimilated,

and comparable policies in Finland. But human groups have oftentimes

been in contact with one another, and this has inevitably resulted in

genetic admixture, for which Scandinavia provides plenty of evidence.

Works Cited

Bjørklund, Ivar. 1985. Fjordfolket i Kvænangen. Oslo, Norway: Universitetsforlaget.

Båk’te, Vilhelm Aubert. 1978. Den samiske befolkning i Nord-Norge. Artikler Fra Statistisk

Sentralbyrå Nr. 107.

Der Sarkissian, Clio, Oleg Balanovsky, Guido Brandt, Valery Khartanovich, Alexandra

Buzhilova, Sergey Koshel, Valery Zaporozhchenko, Detlef Gronenborn, Vyacheslav

Moiseyev, Eugen Kolpakov, Vladimir Shumkin, Kurt W. Alt, Elena Balanovska, Alan

Cooper, and Wolfgang Haak, the Genographic Consortium. 2013. “Ancient DNA

17. Chance is an important factor determining which individuals leave behind more

descendants; it is not necessarily the “fittest” that are most successful in producing

offspring. This is genetic drift; and the smaller the population, the more likely that drift

is to occur. Genetic drift may cause gene variants to disappear completely and thereby

reduce genetic variation.

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

428 Scandinavian Studies

Reveals Prehistoric Gene-Flow from Siberia in the Complex Human Population

History of North East Europe.” PLOS Genetics 9 (2): 1–17.

Dupuy, Berit Myhre, Margurethe Stenersen, Tim T. Lu, and Bjørnar Olaisen. 2006.

“Geographical Heterogeneity of Y-chromosomal Lineages in Norway.” Forensic

Science International 164 (1): 10–9.

Elenius, Lars. 2002. “A Place in the Memory of Nation. Minority Policy towards the

Finnish Speakers in Sweden and Norway.” Acta Borealia 19 (2): 103–23.

Eythórsson, Einar. 2003. “The Coastal Sami: A ‘Pariah Caste’ of the Norwegian Fisheries?

A Reflection on Ethnicity and Power in Norwegian Resource Management.” In

Indigenous Peoples: Resource Management and Global Rights, edited by Svein Jentoft,

Henry Minde, and Ragnar Nilsen, section 9. Delft: The Netherlands: Eburon.

Glørstad, Håkon, Frode Kvalø, Jostein Gundersen, Sverre Planke, Amer Hafeez, Øyvind

Hammer, and Jan Inge Faleide. 2012. Things to Do in Doggerland When You Are

Wet. Oslo, Norway: Universitetet i Oslo, Museum of Cultural History.

Hammer, Michael F., and Stephen L. Zegura. 2002. “The Human Y Chromosome

Haplogroup Tree: Nomenclature and Phylogeography of Its Major Divisions.”

Annual Review of Anthropology 32: 303–21.

Hansen, Lars Ivar, and Bjørnar Olsen. 2007. Samenes historie: Fram til 1750. Oslo,

Norway: Cappelen Akademisk Forlag.

Hedman, M., A. Brandstätter, V. Pimenoff, P. Sistonen, J. U. Palo, W. Parson, and

A. Sajantila. 2007. “Finnish Mitochondrial DNA HVS-I and HVS-II Population

Data.” Forensic Science International 172 (2–3): 171–8.

Hoffecker, John F. 2005. A Prehistory of the North. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers

University Press.

Ingman, Max, and Ulf Gyllensten. 2007. “A Recent Genetic Link between Sámi and

the Volga-Ural Region of Russia.” European Journal of Human Genetics 15: 115–20.

Karafet, Tatiana, Fernando L. Mendez, Monica B. Meilerman, Peter A. Underhill,

Stephen L. Zegura, and Michael F. Hammer. 2008. “New Binary Polymorphisms

Reshape and Increase Resolution of the Human Y Chromosomal Haplogroup

Tree.” Genome Research 18 (5): 830–8.

Karlsson, A. O., T. Wallerström, A. Götherström, and G. Holmlund. 2006. “Y-chro-

mosome Diversity in Sweden: A Long-time Perspective.” European Journal of

Human Genetics 14 (8): 963–70.

Lappalainen, T., V. Laitinen, E. Salmela, P. Andersen, K. Huoponen, M.-L. Savontaus,

and P. Lahermo. 2008. “Migration Waves to the Baltic Sea Region.” Annals of

Human Genetics 72: 337–48.

———. 2009. “Population Structure in Contemporary Sweden: A Y-chromosomal and

Mitrochondrial DNA Analysis.” Annals of Human Genetics 73: 61–73.

Lehtola, Veli-Pekka. 2004. The Sámi People: Traditions in Transition (2nd ed.). Aanaar-

Inari, Finland: Kustannus-Puntsi.

Loogväli, E.-L., U. Roostalu, B. A. Malyarchuk, M. V. Derenko, T. Kivisild, E. Metspalu,

K. Tambets, M. Reidla, H. V. Tolk, J. Parik, E. Pennarun, S. Laos, A. Lunkina,

M. Golubenko, L. Barac, M. Pericic, O. P. Balanovsky, V. Gusar, E. K. Khus-

nutdinova, V. Stepanov, V. Puzyrev, P. Rudan, E. V. Balanovska, E. Grechanina,

C. Richard, J. P. Moisan, A. Chaventré, N. P. Anagnou, K. I. Pappa, E. N. Micha-

lodimitrakis, M. Claustres, M. Gölge, I. Mikerezi, E. Usanga, and R. Villems.

2004. “Disuniting Uniformity: A Pied Cladistic Canvas of mtDNA Haplogroup

H in Eurasia.” Molecular Biology and Evolution 21 (11): 2012–21.

Lundmark, Lennart. 2002. “Lappen är ombytlig, ostadig och obekväm”: Svenska statens

samepolitik i rasismens tidevarv. Umeå, Sweden: Norrlands Universitetsförlag.

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Assimilation of the Sámi 429

———. 2006. Samernas skatteland i norr- och västerbotten under 300 år. Serien III Rätts-

historiska Skrifter, Åttonde Bandet. Stockholm, Sweden: Institutet för rättshistorisk

forskning grundat av Gustav och Carin Olin.

Meinilä, M., S. Finnilä, and K. Majamaa. 2001. “Evidence for mtDNA Admixture

between the Finns and the Saami.” Human Heredity 52 (3): 160–70.

Mellars, Paul. 2006. “A New Radiocarbon Revolution and the Dispersal of Modern

Humans in Eurasia.” Nature 439: 931–5.

Minde, Henry. 2003. “Assimilation of the Sámi: Implementation and Consequences.”

Acta Borealia 20 (2): 121–46.

Nilsen, Ragnar. 2003. “From Norwegianization to Coastal Sámi Uprising.” In Indigenous

Peoples: Resource Management and Global Rights, edited by Svein Jentoft, Henry

Minde, and Ragnar Nilsen, section 9. Delft, The Netherlands: Eburon.

Passarino, Giuseppe, Gianpiero L. Cavalleri, Alice A Lin, Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza,

Anne-Lise Børresen-Dale, and Peter A Underhill. 2002. “Different Genetic Com-

ponents in the Norwegian Population Revealed by the Analysis of mtDNA and Y

Chromosome Polymorphisms.” European Journal of Human Genetics 10 (9): 521–9.

Persen, Bente. 2008. “The Norwegianization of the Samis Was Religiously Motivated,”

reported by Lorenz Khazaleh. University of Oslo. Newsletter. https://www.uio.no/

english/research/interfaculty-research-areas/culcom/news/2008/persen.html.

Rankama, Tuija, and Jarmo Kankaanpää. 2011. “First Evidence of Eastern Preboreal

Pioneers in Arctic Finland and Norway.” Quartär 58: 183–206.

Richards, Martin, Vincent Macaulay, Eileen Hickey, Emilce Vega, Bryan Sykes, Valentina

Guida, Chiara Rengo, Daniele Sellitto, Fulvio Cruciani, Toomas Kivisild, Richard

Villems, Mark Thomas, Serge Rychkov, Oksana Rychkov, Yuri Rychkov, Mukad-

des Gölge, Dimitar Dimitrov, Emmeline Hill, Dan Bradley, Valentino Romano,

Francesco Calì, Giuseppe Vona, Andrew Demaine, Surinder Papiha, Costas Tri-

antaphyllidis, Gheorghe Stefanescu, Jiři Hatina, Michele Belledi, Anna Di Rienzo,

Ariella Oppenheim, Søren Nørby, Nadia Al-Zaheri, Silvana Santachiara-Benerecetti,

Rosaria Scozzari, Antonio Torroni, and Hans-Jürgen Bandelt. 2000. “Tracing

European Founder Lineages in the Near Eastern mtDNA Pool.” American Journal

of Human Genetics 67 (5): 1251–76.

Rootsi, Siiri, Chiara Magri, Toomas Kivisild, Giorgia Benuzzi, Hela Help, Marina Ber-

misheva, Ildus Kutuev, Lovorka Barać, Marijana Peričić, Oleg Balanovsky, Andrey

Pshenichnov, Daniel Dion, Monica Grobei, Lev A. Zhivotovsky, Vincenza Battaglia,

Alessandro Achilli, Nadia Al-Zahery, Jüri Parik, Roy King, Cengiz Cinnioğlu, Elsa

Khusnutdinova, Pavao Rudan, Elena Balanovska, Wolfgang Scheffrahn, Maya Sim-

onescu, Antonio Brehm, Rita Goncalves, Alexandra Rosa, Jean-Paul Moisan, Andre

Chaventre, Vladimir Ferak, Sandor Füredi, Peter J. Oefner, Peidong Shen, Lars

Beckman, Ilia Mikerezi, Rifet Terzić, Dragan Primorac, Anne Cambon-Thomsen,

Astrida Krumina, Antonio Torroni, Peter A. Underhill, A. Silvana Santachiara-

Benerecetti, Richard Villems, and Ornella Semino. 2004. “Phylogeography of

Y-Chromosome Haplogroup I Reveals Distinct Domains of Prehistoric Gene Flow

in Europe.” American Journal of Human Genetics 75 (1): 128–37.

———. 2007. “A Counter-clockwise Northern Route of the Y-chromosome Haplogroup

N from Southeast Asia towards Europe.” European Journal of Human Genetics

15: 204–11.

Rosberg, Johan Evert. 1910. Anteckningar om lapperna i Finland. Övertryck ur Geo-

grafiska Föreningens Tidskrift, hft. 102.

Sablin, Mikhail V., and Gennady A. Khlopachev. 2002. “The Earliest Ice Age Dogs:

Evidence from Eliseevichi I.” Current Anthropology 43 (5): 795–9.

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

430 Scandinavian Studies

Sammallahti, Pekka. 1998. The Saami Languages: An Introduction. Kárášjohka, Norway:

Davvi Girji OS.

Skoglund, Pontus, Helena Malmström, Maanasa Raghavan, Jan Storå, Per Hall, Eske

Willerslev, M. Thomas P. Gilbert, Anders Götherström, and Mattias Jakobsson.

2012. “Origins and Genetic Legacy of Neolithic Farmers and Hunter-Gatherers

in Europe.” Science 336 (6080): 466–9.

Spinney, Laura. 2012. “A World beneath the Sea.” National Geographic 222 (6): 132–43.

Tambets, K., S. Rootsi, T. Kivisild, H. Help, P. Serk, E. L. Loogväli, H. V. Tolk,

M. Reidla, E. Metspalu, L. Pliss, O. Balanovsky, A. Pshenichnov, E. Balanov

ska, M. Gubina, S. Zhadanov, L. Osipova, L. Damba, M. Voevoda, I. Kutuev,

M. Bermisheva, E. Khusnutdinova, V. Gusar, E. Grechanina, J. Parik, E. Pen-

narun, C. Richard, A. Chaventre, J. P. Moisan, L. Barác, M. Pericić, P. Rudan,

R. Terzić, I. Mikerezi, A. Krumina, V. Baumanis, S. Koziel, O. Rickards, G. F. De

Stefano, N. Anagnou, K. I. Pappa, E. Michalodimitrakis, V. Ferák, S. Füredi,

R. Komel, L. Beckman, and R. Villems. 2004. “The Western and Eastern Roots

of the Saami: The Story of Genetic ‘Outliers’ Told by Mitochondrial DNA and

Y Chromosomes.” American Journal of Human Genetics 74 (4): 661–82.

Trosterud, Trond. 2008. “Language Assimilation during the Modernisation Process:

Experiences from Norway and North-West Russia.” Acta Borealia 25 (2): 93–22.

Weinstock, John. 2010. “Thoughts about Saami Prehistory.” In Samar som “den andre”,

samar om “den andre”: Identitet og etnicitet i nordiska kulturmöten, edited by Else

Mundal and Håkan Rydving, 31–45. Sámi dutkan—Samiska studier—Sámi Studies,

6. Umeå, Sweden: Umeå Universitet.

———. (Forthcoming). “At the Frontier: Sámi Linguistics Gets a Boost from Out-

side.” Advances in Nordic Linguistics (tentative). FRIAS ‘Linguae et Litterae’ De

Gruyter Mouton.

Wiik, Kalevi. 2008. “Where Did European Men Come From?” Journal of Genetic

Genealogy 4: 35–85.

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Wed, 26 Apr 2023 02:24:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Viking DissertationDocument7 pagesViking DissertationPayForAPaperUK100% (1)

- Cahpter 1 The AustronesiansDocument17 pagesCahpter 1 The AustronesiansKristine Abby MainarNo ratings yet

- Austronesians PaperDocument13 pagesAustronesians PaperDexter TendidoNo ratings yet

- Geschichte MadagaskarDocument50 pagesGeschichte MadagaskarFibichovaNo ratings yet

- The Origin of The Polynesian Race Author(s) : W. D. Alexander Source: The Journal of Race Development, Oct., 1910, Vol. 1, No. 2 (Oct., 1910), Pp. 221-230Document11 pagesThe Origin of The Polynesian Race Author(s) : W. D. Alexander Source: The Journal of Race Development, Oct., 1910, Vol. 1, No. 2 (Oct., 1910), Pp. 221-230Klaus-BärbelvonMolchhagenNo ratings yet

- Annualreviewpaper 3Document53 pagesAnnualreviewpaper 3X AKL 4 Ahmad alvi AfriantoNo ratings yet

- American Association For The Advancement of Science Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve andDocument4 pagesAmerican Association For The Advancement of Science Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve andmikey_tipswordNo ratings yet

- MSP 120Document16 pagesMSP 120Mohamed EmanNo ratings yet

- Hirschman The Origins and Demise of The Concept of RaceDocument32 pagesHirschman The Origins and Demise of The Concept of RaceAndrea ChavezNo ratings yet

- Finno-Ugric Societies Pre 800 AD (Carpelan) PDFDocument15 pagesFinno-Ugric Societies Pre 800 AD (Carpelan) PDFJenny KangasvuoNo ratings yet

- Ancient DNA Study Sheds Light On Deep Population History of Andes - Genetics, Paleoanthropology - Sci-NewsDocument4 pagesAncient DNA Study Sheds Light On Deep Population History of Andes - Genetics, Paleoanthropology - Sci-NewsdpolsekNo ratings yet

- Colonisation, Migration, and Marginal Areas: A Zooarchaeological ApproachFrom EverandColonisation, Migration, and Marginal Areas: A Zooarchaeological ApproachNo ratings yet

- Austronesian PeoplesDocument14 pagesAustronesian PeoplesFizz CrimlnzNo ratings yet

- Cornell-Notes 4Document3 pagesCornell-Notes 4chinhxaydung3No ratings yet

- The Origins and Demise of The Concept of RaceDocument32 pagesThe Origins and Demise of The Concept of RacesandrababativaNo ratings yet

- Wiley American Anthropological AssociationDocument31 pagesWiley American Anthropological AssociationDanilo Viličić AlarcónNo ratings yet

- Philological Proofs of the Original Unity and Recent Origin of the Human RaceFrom EverandPhilological Proofs of the Original Unity and Recent Origin of the Human RaceNo ratings yet

- Holes in Our Moccasins, Holes in Our Stories: Apachean Origins and the Promontory, Franktown, and Dismal River Archaeological RecordsFrom EverandHoles in Our Moccasins, Holes in Our Stories: Apachean Origins and the Promontory, Franktown, and Dismal River Archaeological RecordsJohn W. IvesNo ratings yet

- History of Scandinavia, From the Early Times of the Northmen and Vikings to the Present DayFrom EverandHistory of Scandinavia, From the Early Times of the Northmen and Vikings to the Present DayNo ratings yet

- The Last Speakers: The Quest to Save the World's Most Endangered LanguagesFrom EverandThe Last Speakers: The Quest to Save the World's Most Endangered LanguagesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- J ctt2jbjx1 8Document17 pagesJ ctt2jbjx1 8Mad KumatNo ratings yet

- Polynesian Origins and MigrationsDocument57 pagesPolynesian Origins and MigrationsSoniaBentancourteNo ratings yet

- Archaeology in Oceania - 2019 - POSTH - Response To Ancient DNA and Its Contribution To Understanding The Human History ofDocument5 pagesArchaeology in Oceania - 2019 - POSTH - Response To Ancient DNA and Its Contribution To Understanding The Human History ofrico neksonNo ratings yet

- Linguistics and Archaeology A Critical V PDFDocument312 pagesLinguistics and Archaeology A Critical V PDFAbdel Guerra LopezNo ratings yet

- ICAZ2023 Abstracts Final V4Document249 pagesICAZ2023 Abstracts Final V4Goran TomacNo ratings yet

- Eastern and Western Europe TribesDocument11 pagesEastern and Western Europe TribesBrian MendozaNo ratings yet

- 11 Hyman - Technology TransferDocument30 pages11 Hyman - Technology TransferJean Paul Orellana MoralesNo ratings yet

- Stable Dietary Isotopes and mtDNA From Woodland Period Southern Ontario People: Results From A Tooth Sampling ProtocolDocument12 pagesStable Dietary Isotopes and mtDNA From Woodland Period Southern Ontario People: Results From A Tooth Sampling ProtocolPaola Rosario SantosNo ratings yet

- HANSON The Making of The Maori PDFDocument14 pagesHANSON The Making of The Maori PDFMiguel Aparicio100% (1)

- Hanson MaoriDocument14 pagesHanson MaoriJulián Antonio Moraga RiquelmeNo ratings yet

- Ancient Mitochondrial DNA From Malaysian Hair Samples - Some Indications of Southeast Asian Population Movements - P.Z.2006Document14 pagesAncient Mitochondrial DNA From Malaysian Hair Samples - Some Indications of Southeast Asian Population Movements - P.Z.2006yazna64No ratings yet

- Comparative Phylogenetic Analyses Uncover The Ancient Roots of Indo-European Folktales - Graça, TehraniDocument11 pagesComparative Phylogenetic Analyses Uncover The Ancient Roots of Indo-European Folktales - Graça, TehraniAlexandre FunciaNo ratings yet

- HANSON - The Making of The MaoriDocument14 pagesHANSON - The Making of The MaoriRodrigo AmaroNo ratings yet

- A Mitochondrial Stratigraphy For Island Southeast Asia - P.Z. 2007Document15 pagesA Mitochondrial Stratigraphy For Island Southeast Asia - P.Z. 2007yazna64No ratings yet

- Australian Aboriginal Geomythology: Eyewitness Accounts of Cosmic Impacts?Document51 pagesAustralian Aboriginal Geomythology: Eyewitness Accounts of Cosmic Impacts?VinceNo ratings yet

- Emplaced MythDocument292 pagesEmplaced MythadrianojowNo ratings yet

- Terrel Sleeping GiantDocument10 pagesTerrel Sleeping GiantNurul Afni Sya'adahNo ratings yet

- Newslei'I'Er: - ISSUE32 (LR32)Document27 pagesNewslei'I'Er: - ISSUE32 (LR32)Allan BomhardNo ratings yet

- Maori, Pakeha and Kiwi: Peoples, Cultures and Sequence in New Zealand ArchaeologyDocument15 pagesMaori, Pakeha and Kiwi: Peoples, Cultures and Sequence in New Zealand ArchaeologyKiran Karki100% (1)

- The Impact of Diasporas Markers of IdentityDocument8 pagesThe Impact of Diasporas Markers of IdentityNesreen YusufNo ratings yet

- Table of Contents:: DNA Tribes Digest November 1, 2011Document14 pagesTable of Contents:: DNA Tribes Digest November 1, 2011komooryNo ratings yet

- Archaeology Genetics and Language in TheDocument23 pagesArchaeology Genetics and Language in TheRenan Falcheti PeixotoNo ratings yet

- Comparative Phylogenetic Analyses Uncover The Ancient Roots of Indo-European FolktalesDocument11 pagesComparative Phylogenetic Analyses Uncover The Ancient Roots of Indo-European Folktalesliber mutusNo ratings yet

- Gould - Grimm's Greatest TaleDocument4 pagesGould - Grimm's Greatest TaleAllan BomhardNo ratings yet

- A35. 1992. SEAsian Linguistic Traditions in The PhilippinesDocument13 pagesA35. 1992. SEAsian Linguistic Traditions in The PhilippineskarielynkawNo ratings yet

- 3.1.2 - Indigenous Relationships - StudentDocument15 pages3.1.2 - Indigenous Relationships - StudentMatthew Pringle100% (2)

- The Making of The Maori - Culture Invention and Its LogicDocument14 pagesThe Making of The Maori - Culture Invention and Its LogicCarola LalalaNo ratings yet

- Wiesner 1983 Style and Social Information in Kalahari San Projectile PointsDocument25 pagesWiesner 1983 Style and Social Information in Kalahari San Projectile PointsJa AsiNo ratings yet

- Kiswahili People Language Literature and Lingua FRDocument21 pagesKiswahili People Language Literature and Lingua FRelsiciidNo ratings yet

- Sami EssayDocument5 pagesSami EssayEthan JefferyNo ratings yet

- Skoglund y Reich2016Document9 pagesSkoglund y Reich2016Aelita MoreiraNo ratings yet

- The Deep Time Memory of The Gaulish LangDocument9 pagesThe Deep Time Memory of The Gaulish LangРафаил ГаспарянNo ratings yet

- PIIS0002929707604030Document30 pagesPIIS0002929707604030youservezeropurpose113No ratings yet

- F O I M N: Oreigners and Utside Nfluences in Edieval OrwayDocument131 pagesF O I M N: Oreigners and Utside Nfluences in Edieval OrwayAlessandroNo ratings yet

- Muller LDancinggoldenstoolsDocument27 pagesMuller LDancinggoldenstoolsudehgideon975No ratings yet

- Arctic Triumph: Northern Innovation and PersistenceFrom EverandArctic Triumph: Northern Innovation and PersistenceNikolas SellheimNo ratings yet

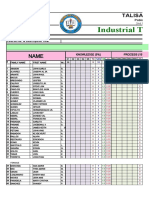

- Industrial Technology Program: Talisay City CollegeDocument22 pagesIndustrial Technology Program: Talisay City CollegeAlther DabonNo ratings yet

- 2019 Haplogroup MDocument37 pages2019 Haplogroup MKlaus MarklNo ratings yet

- National Geographic DNA Testing ResultsDocument5 pagesNational Geographic DNA Testing ResultsAnonymous 4KhR0D8GNo ratings yet

- Hitung Rab Kantor Ledok, Kawengan, Nglobo 27072020Document79 pagesHitung Rab Kantor Ledok, Kawengan, Nglobo 27072020Gie Kancut SurosentikoNo ratings yet

- Genetic Study of IndiansDocument4 pagesGenetic Study of IndiansAbhishek P Benjamin100% (1)

- Origins & History of Haplogroup H (MtDNA)Document10 pagesOrigins & History of Haplogroup H (MtDNA)floragevaraNo ratings yet

- Armatura Gornje ZoneDocument13 pagesArmatura Gornje ZoneNoveljaNo ratings yet

- Haplogroup R1a As The Proto Indo Europeans and The Legendary Aryans As Witnessed by The DNA of Their Current Descendants A.KlyosovDocument13 pagesHaplogroup R1a As The Proto Indo Europeans and The Legendary Aryans As Witnessed by The DNA of Their Current Descendants A.KlyosovSanja Jankovic100% (1)

- Nba Co - Po - Pso Al - Maintenance EngineeringDocument32 pagesNba Co - Po - Pso Al - Maintenance EngineeringSaravana Kumar MNo ratings yet

- OLEGARIO CLAN (Family Tree)Document18 pagesOLEGARIO CLAN (Family Tree)Iñigo Javier Demata Olegario100% (1)

- Ericsson RNC3810 Cards (MoShell)Document4 pagesEricsson RNC3810 Cards (MoShell)Jose MadridNo ratings yet

- Did African Slaves Bring The Y-Chromosomes R1 Clades To The Americas?Document10 pagesDid African Slaves Bring The Y-Chromosomes R1 Clades To The Americas?Ademário HotepNo ratings yet

- 2019 Haplogroup HDocument182 pages2019 Haplogroup HKlaus MarklNo ratings yet

- Origins & History of Haplogroup I2 (Y-DNA)Document7 pagesOrigins & History of Haplogroup I2 (Y-DNA)floragevaraNo ratings yet

- I2Document20 pagesI2Farid AmirzaiNo ratings yet

- X1-3 X2-3 X3-3 X4-3 X5-3 X6-3 X7-3 X8-3 X9-3: X10-1 X10-2 X10-4 X10-5 X10-6 X10-7 X10-8 X10-9 X10-10 1Document5 pagesX1-3 X2-3 X3-3 X4-3 X5-3 X6-3 X7-3 X8-3 X9-3: X10-1 X10-2 X10-4 X10-5 X10-6 X10-7 X10-8 X10-9 X10-10 1Edgar Tejeda VieraNo ratings yet

- Mitochondrial DNA Rare in E Europe and N Asia PDFDocument12 pagesMitochondrial DNA Rare in E Europe and N Asia PDFAlexander HagenNo ratings yet

- Perfilado Inteior LADO A - Fresa 4mm - IzqinferiorDocument11 pagesPerfilado Inteior LADO A - Fresa 4mm - IzqinferiorHuachalinNo ratings yet

- The Origin of The Pashtuns PathansDocument4 pagesThe Origin of The Pashtuns PathansTuri AhmedNo ratings yet

- 2016 - Analysis of Y-Chromosome STRs in Chile Confirms An Extensive Introgression of European Male Lineages in Urban PopulationsDocument5 pages2016 - Analysis of Y-Chromosome STRs in Chile Confirms An Extensive Introgression of European Male Lineages in Urban PopulationsDaniela TroncosoNo ratings yet

- The African Origin of R1 DNADocument4 pagesThe African Origin of R1 DNAjjNo ratings yet

- FamilyTreeDNA - Hashem & Y-DNA Cousins (FGC8712 & L862 Geography)Document22 pagesFamilyTreeDNA - Hashem & Y-DNA Cousins (FGC8712 & L862 Geography)عبدالله الدهمشيNo ratings yet

- Georgia Teacher SalaryDocument1 pageGeorgia Teacher SalaryRangerBrianNo ratings yet

- Aay6826 Antonio SMDocument117 pagesAay6826 Antonio SMRichard BlandiniNo ratings yet

- Analiza Haplo Grupa Bosnjaka I Dr.Document12 pagesAnaliza Haplo Grupa Bosnjaka I Dr.damirzeNo ratings yet

- 2019 Haplogroup QDocument304 pages2019 Haplogroup QKlaus MarklNo ratings yet

- Same Scale Showing Pay Increases Year One and TwoDocument18 pagesSame Scale Showing Pay Increases Year One and TwoWalter E Headley FopNo ratings yet

- Vilar-Iaca2013 TgsDocument28 pagesVilar-Iaca2013 Tgsapi-285072870No ratings yet

- Phylogenetic Relations and Geographic Distribution of I-L38 (Aka I2b2)Document16 pagesPhylogenetic Relations and Geographic Distribution of I-L38 (Aka I2b2)pcanongesNo ratings yet

- Backup Data Peningkatan Drainase Lr. GerisaDocument12 pagesBackup Data Peningkatan Drainase Lr. GerisaHermanto RidwanNo ratings yet