Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Too Many Friends - Social Integration, Network Cohesion and Adolescent Depressive Symptoms - Falci & McNeely (2009)

Uploaded by

Eduardo Aguirre DávilaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Too Many Friends - Social Integration, Network Cohesion and Adolescent Depressive Symptoms - Falci & McNeely (2009)

Uploaded by

Eduardo Aguirre DávilaCopyright:

Available Formats

Too Many Friends: Social Integration, Network Cohesion and Adolescent Depressive Symptoms

Author(s): Christina Falci and Clea McNeely

Source: Social Forces, Vol. 87, No. 4 (Jun., 2009), pp. 2031-2061

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40345007 .

Accessed: 15/06/2014 16:21

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social Forces.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NetworkCohesion

Too ManyFriends:Social Integration,

and AdolescentDepressiveSymptoms

ofNebraska-Lincoln

ChristinaFalci, University

Clea McNeely,University ofTennessee-Knoxville

Using a nationally representativesample of adolescents,we

examine associations among social integration (network

size), networkcohesion (alter-density),perceptionsof social

relationships(e.g., social support) and adolescent depressive

symptoms.Wefind that adolescentswith eithertoo large or

too small a networkhave higherlevelsofdepressivesymptoms.

Amonggirls,however,theilleffects ofover-integrationonlyoccur

at low levelsof networkcohesion.For boys,in contrast,the ill

effectsof over-integration onlyoccur at highlevelsof network

cohesion.Largesocial networkstendnotto compromise positive

perceptionsoffriend support or belonging; whereas, small

networksare associatedwithlowperceptionsoffriendsupport

and belonging. Hence,perceptions mediate

ofsocial relationships

theill effects

of under-integration, but not on

over-integration,

depressivesymptoms.

Roughly30 percentof adolescents reportmoderateto severe depressive

symptoms(Rushton,Forcierand Schectman2002). The earlyoccurrence

of depressionin adolescence sets a foundation forrecurrentand severe

depressiveepisodes laterin life(Belsherand Costello1988; Kovacs et al.

1984). Depressioninadolescence is also an urgenthealthconcern.Depres-

sivesymptomsarethestrongestpredictor ofsuicidalideationwhich,inturn,

predictssuicideattempts(Kandel,Raveisand Davies 1991). Suicideis the

fourthleadingcause of deathamong 10-14yearolds inthe UnitedStates

and the thirdleadingcause of death among 15-24year olds (Anderson

2001). This researchexploreshow the networkstructure and perception

ofadolescentfriendships influencedepressivesymptomsinadolescence.

Several decades of research make a clear link between social

relationshipsand depressive symptoms in adolescence. This is not

surprising and managingpeerrelationships

giventhatcultivating is a central

developmentaltaskofadolescence, requiring muchtimeand energy.The

vast majority of researchon peer relationshipsfocuses on perceptions

Theauthors funding

acknowledge

gratefully fromtheWilliamT. GrantFoundation. We

wouldalsoliketoexpress to

thanks JimMoody his

sharing

forgraciously SAS for

Programs

AnalyzingNetworks toChristina

usersmanualDirectcorrespondence Falci,University

of

Nebraska-Lincoln, 711OldfatherHall,

ofSociology,

Department NE 68588-0324.

Lincoln,

E-mail:cfalci2@unl.edu.

of NorthCarolinaPress

© The University Social Forces 87(4): 203 1-62.June 2009

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2032 • SocialForces87(4)

ofthose relationships. Adolescentswho perceivehighlevelsof affection

and acceptance frompeers reportfewerdepressive symptoms(Beam

et al. 2002; Formoso,Gonzales and Aiken2000; Furmanand Buhrmester

1992). Relativelyfew studies investigatehow the structureof social

networks- the patternof ties between membersof a social network-

relateto depressivesymptomsamong adolescents (forexceptionssee

Hansell1985; Ueno 2005). The focusofsocial networkanalysisis theties

between individualsratherthan individuals'experiencesor perceptions

of relationships (Wassermanand Faust 1994). An advantageof network

structureanalysisis the abilityto go beyondindividualperceptions:this

researchdoes notrelysolelyon self-reports fromadolescents.

The choice to relysolely on adolescent self-reportis oftendue to

methodologicalchallenges: reportsfromadolescents' friendsare costly

to collectand seldom existinsecondarydatasets. However,studiesthat

relyonlyon self-report of friendships,especially as theyare linkedto

mentalhealth,sufferfromtwo significant limitations.First,self-reported

perceptions, how

including many friendsone has and how supportivethose

friendships are, may be influenced by currentor previousexperiencesof

depressed mood (Turner and Turner1999). Second, and morebroadly,by

relying on adolescents' self-report oftheirfriendship experienceswe fail

to understand theinfluencesofthestructural propertiesoftheirfriendship

network. Structural network characteristicscannotbe accuratelymeasured

fromthe perceptionsofa singlememberofthe network(Wellman1988).

Inthisarticle,social network theoryand methodsare appliedto investigate

the influenceof networkstructureon adolescent depressivesymptoms,

focusingon two dimensionsof networkstructure, social integration

and

networkcohesion.

Social integration is the aspect of networkstructure thathas received

the moststudy.Broadlydefined,itis the degree to whichan individual is

connectedto otherindividualsin a network.Social integration has three

dimensions:the numberofsocial ties,thetypeoftie(e.g., close friendvs.

acquaintance)and thefrequency ofcontact(House, Umbersonand Landis

1988). Ofthese three dimensions,the numberofsocial ties,orthe size of

an adolescent's friendship network,has receivedthe most empiricalat-

tentioninresearchon adolescents (Ennettet al. 2006; Ueno 2005). Social

integration is hypothesizedto have a curvilinear relationshipwithdepres-

sive symptomssuch thathavingeithertoo fewfriends(under-integration)

ortoo many(over-integration) is harmfulto mentalhealth(Durkheim1951;

Pescosolido and Levy2002). Althoughempiricalresearchsupportsthe

claimthatadolescents withtoo few friendship ties are more likelyto ex-

perience depressive symptoms(Brendgan, Vitaro and Bukowski2000;

Ueno 2005),the possibility thathavingtoo manyfriendsmightbe linkedto

depressivesymptomsinadolescents has notbeen adequatelyexplored.1

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and DepressiveSymptoms• 2033

NetworkStructure

The possibilitythat propertiesof social networkstructurefunction

multiplicatively ratherthan additivelyhas seldom been explored for

adolescent networks (for an exception see Haynie 2001). Previous

research on adolescents typicallyhas treateddifferent dimensionsof

networkstructureas theoretically independentconstructs(Ennettet al.

2006; Ueno 2005). This researchtests whetherthe association between

social integrationand depressivesymptomsvaries as a functionof the

cohesiveness of the friendship network.Networkcohesion refersto the

degree of interconnections within a social network.Withina network

of friendshipties, network cohesion assesses the extentto which an

adolescent's friendsare friendswithone another.This research also

explores how the association between the two dimensionsof network

structure- social integration and networkcohesion - affectdepressive

symptoms differently for boys and girls. Previous research has not

assessed gendervariationinthe association between networkstructure

and depressivesymptoms.Yet,social networkresearchinorganizational

settingssuggests the effectof networkstructureon workeroutcomes

differsby gender(Burt1998; Ibarra1997). Similarpatternsmightoccur

when investigating the networkstructureof adolescent friendshipson

depressivesymptoms.

In additionto makingthree new contributionsto research on how

adolescent friendshipnetworksaffectmental health - testing for a

curvilinearrelationshipbetween social integrationand depressive

symptoms,testingwhethernetworkcohesion modifiesthatassociation

and testingforgenderdifferences - thisarticleextendsand verifiesthe

findings ofUeno's (2005) foundational researchlinkingsmallnetworksize

to depressive symptoms.Like Ueno, the argumentthatthe presence

of a single close friendis more important to an individual'swell-being

thanthe numberof friends investigated(Baumeisterand Leary1995).

is

Ueno foundthata singleclose friendis not sufficient to protectagainst

depressivesymptoms. The current research extends thislineofinquiryby

taking into account reciprocity. Ueno (2005) also foundthat the influence

of under-integration on depressivesymptomsis mediatedby perceived

belonging.The current researchexploresan additionalmediator, perceived

support from friends,and also tests whether adolescents' perceptions of

and

belonging support can mediate the effects of as

over-integration, well

as under-integration,on depressivesymptoms.

and DepressiveSymptoms

Under-integration

Adolescentswhoare under-integrated (i.e.,theyhaveveryfewornofriends)

are at greaterriskfordepressivesymptoms(Brendgenet al. 2000; Ueno

2005). Adolescents seek social connectionwithpeers (Baumeisterand

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2034 • SocialForces87(4)

Leary1995; Chu2005). Iftheirefforts theyare morelikely

go unfulfilled, to

experience exclusionand loneliness,and to developdepressivesymptoms

(Rosenbergand Cullough1981). Because thesefindings holdforbothboys

and girls,we do notexpecttheeffectofunder-integration to varybygender.

We also do notexpectthe effectof under-integration to varyby network

cohesion.Bydefinition,sociallyisolatedadolescentscannothavecohesive

networks.It is necessaryto have a minimum of two friendsto knowthe

extentto whichone's friendsare friendswithone another.Even among

adolescentswithmorethantwo friends, smallnetworks,

butrelatively we

do notexpectthe effectof networksize to varybynetworkcohesion.

75OneFriend

Enough?

Some arguethata singleclose friend

can providesufficient

intimacy,support

and companionshipforan adolescent'swell-being(Baumeisterand Leary

1995). We hypothesizethatsmall networksize contributes to depressed

mood even when an adolescent has a reciprocatedclose friendship.

we do notexpectone close friend

Essentially, to meetallofan adolescent's

needs forsocial connection.A singlefrienddoes notgiveaccess to social

channels,bothofwhichhelpa studentfitinat school

statusor information

(Crosnoeand McNeelyin press; Walker,Wassermanand Wellman1993).

Thereis previousempiricalsupportforthishypothesis(Ueno 2005).

MeditationofUnder-Integration

byPerceptions and Support

ofBelonging

fromFriends

We examineperceptionsof belongingand supportfromfriendsas two

mediatingmechanismsby whichunder-integration mightlead to higher

levels of depressivesymptomsamong adolescents (House et al. 1988;

Ueno 2005). Perceivedbelongingat school is the sense of being a part

of the social fabricat school, of fitting

in. Not havingfriendsto sit with

in the lunchroom or to pass notes to in class can underminefeelings

of belonging.Seeminglyinnocuous moments,such as passing time or

choosingteams fora class project,become laden withthe potentialfor

feelingsof rejectionand isolation.Thus,adolescentswithfewfriendsare

less likely

to feelthattheybelongat school. Perceivedsupportfromfriends

is theextenttowhichadolescentsbelievethattheirfriends careaboutthem.

Adolescentswithfewfriendsmightperceiveless supportthanadolescents

withmorefriends.In lightofthese predictions, we expectthatperceived

belongingand friendsupportwillmediatethe relationship betweensmall

network size and depressivesymptomsinadolescence. Previousresearch

has demonstrated thatsupportfromfriendsand a sense of belongingare

inverselyrelatedwithdepressive symptoms(Laible,Carlo and Farraelli

2000; McNeelyand Falci2004). Furthermore, usingthe same Add Health

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and DepressiveSymptoms• 2035

NetworkStructure

data set, Ueno (2005) foundthat a sense of belongingmediated the

betweennetworksize and adolescentdepressivesymptoms

relationship

when networksize was modeled as a linearrelationship.

Supportfrom

friendshas notbeen exploredpreviouslyas a mediator.

and DepressiveSymptoms

Over-Integration

Over-integration is oftentheorized to resultingreatermentalhealthproblems

(Pescosolidoand Levy2002). Durkheim (1951) arguedthatover-integration

could lead to altruisticsuicide,wherea persontakes hisown life"because

itis hisduty."(Durkheim1951:219) Inthisinstance,an individual sacrifices

himself forhiscommunity (e.g.,a soldier jumping on a livegrenadeto save

fellowsoldiersoran elderlypersoninpoorhealthendinghislifeso as notto

burdenlovedones). Our researchinvestigatesdepressivesymptoms,not

suicide,buttheidea ofdutyorobligationis partly whyover-integration may

lead to higherlevelsofdepressivesymptoms.The roleoffriendship entails

a set of behavioralexpectations,such as providing comfortor assistance

and spendingtimetogether.As the numberof friendsan individualhas

increases,the timeand energycosts of maintaining themalso increases

and mayoutweighthe benefitsof having (Eder 1985; Eder,Evans

friends

and Parker1995). Havingobligationsto manyfriendsmayleave a person

feelingwornout.Too manyfriendscould resultin rolestrainbecause the

demandson the adolescentto fulfill the roleoffriendship are greaterthan

his or herabilityto enact the role(Pearlin1983). Role strain,in turn,can

lead to poorself-assessmentof one's success inenactingthe friendship

role.Bothrolestrainand negativeroleperformance evaluationsare likely

to

to lead depressivesymptoms(Thoits 1991 ).

Does theEffect

ofOver-Integration Cohesionand Gender?

VarybyNetwork

Previousresearch has focused on the independenteffectsof distinct

networkcharacteristics; however,the negativeeffectof havingtoo many

friendsmaydepend on levelsofnetworkcohesion.Networkcohesioncan

be representedas a continuum fromlowto highcohesion.Atone extreme,

an adolescent mighthave a completelyfragmentedlocal networkwhere

noneoftheadolescent's friendsare friendswithone another.Attheother

extreme,an adolescent could have a closed network,where all of the

adolescent's friendsnominateeach otheras a friend.Adolescentstend

to fallsomewhere in the middleof these two extremes,butthe former

extremeis morecommonthanthe latter(see appendixA).

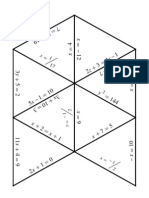

One can understandthe importof the cohesiveness of network

structureintuitivelyby lookingat friendshipstructurevisually.Figure1

shows two largefriendship networksof equal size (15 actors),butwith

varyinglevels of network cohesion. The networkin Panel A has low

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2036 • SocialForces87(4)

withVaryingLevelsofAlter-Density

Figure1. AlterNetworks

PanelA PanelB

= 15%

Alter-density = 50%

Alter-density

Large Network

Fragmented Cohesive

Large Network

networkcohesion; referred to as a largefragmented network.Few ofthe

friendswithinthisadolescent's friendship networkare friendswitheach

other.Of all the possible ties among alters(i.e.,the adolescent's friends),

just 15 percentare actualfriendship ties. The networkinPanelB has high

network cohesion; referred to as a largecohesivenetwork.Inthisnetwork,

an adolescent's friendsalso tend to be friendswithone another.Fifty

percentofthe possibleties betweentheadolescent's friendsare present.

Experienceswithpeerrelationships maydramatically betweenthese

differ

two networkstructuresleadingto differences indepressivesymptoms.

Specifically, adolescents who have large fragmentednetworksmay

reporthigherlevelsofdepressivesymptomsthanadolescents withlarge

cohesive networks.Large fragmentednetworksshould exacerbatethe

role strainof numerousfriendships.Because an adolescent's friends

do not know one anotherin a fragmentednetwork- at least not very

well - any givenfriendwill be unaware of the various demands other

friendsmightplace on the adolescent. Consequently,the social costs

and obligationsof havingnumerousfriendswillbe greaterinfragmented

networksand the adolescent may experience greater role strain.In

contrast,when largenetworksare cohesive,the cohesion mightprovide

some protectionfromthe potentialcosts of manyfriendships.Large

cohesive networksshould be betterable to share and coordinatesocial

supportto a networkmember,therebypreventing the overburdeningof

any one networkmember.Furthermore, knowingthatotherfriendsare

supporting a friendinneed might alleviate feelinginadequateabout one's

own role performance. Thus, large cohesive networksmightbufferthe

negativeeffectsof over-integration on depressivesymptoms.

Theremay,however,be gendervariationinthe patternshypothesized

above. Similarnetworkstructures,such as a large cohesive friendship

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and DepressiveSymptoms• 2037

NetworkStructure

networks,can have different effectson healthoutcomes ifthe natureof

social interactionsoccurring within those similarnetworkconfigurations

differ 2004). Patternsofsocial interaction

(Friedkin withinan adolescent's

friendship network to varybytheadolescent's genderforseveral

are likely

reasons. First,adolescent boys face greaterpressure to conformto

masculinerolesthangirlsdo forfeminineroles(Zucker, Wilson-Smith and

Stern1995; Fagot1985) and a failureto conformto normsof masculinity

can result in ridiculefromfriends(Messerschmidt 2000; Chu 2005).

Second, adolescentboys'social interactions tendto revolvearoundsocial

activities,whereas adolescent girlsare more likelyto reportengaging

in mutuallysupportiveinteractions withfriends(Nada-Raja,McGee and

Stanton1992; Frydenberg and Lewis1993).Third,girlsare morelikely than

to

boys privilege the needs of others over their own needs (Rosenfield,

Lennon and White 2005). Clearly,adolescent boys and girlstend to

approachor experiencepeer friendships ina differentmanner.

These potentialgenderdifferences inpatternsofsocial interactionswith

friendsmaylead to genderdifferences intheeffectofnetwork structureon

depressivesymptoms.Specifically, highlevelsofsocial cohesion may not

be as beneficialforadolescentboys comparedto adolescentgirls.Highly

cohesivenetworkswillbe able to exertmorepressureon boysto conform

to groupmasculinity normsthan less cohesive networks(Friedkin 1984;

Haynie2001; Eder and Enke 1991). In orderto avoid ridiculefromnon-

conformity, an adolescentboywillact ina mannerconsistentwithnorms,

evenifthose normsdo notrepresent himpersonally (Chu2005). Inauthentic

self-presentations to

are likely lead to poor mental healthoutcomes(Gecas

1986). Since adolescentboyswithhighly cohesive networksmaybe more

inclinedto have inauthentic self-presentations thanboys in less cohesive

networks, theymay also be more likelyto have higherlevelsofdepressive

symptoms.As a result,highlevelsof social cohesion maynotbuffer the

effectofover-integration on depressivesymptomsforboys.

Second, largefragmented networkswillbe particularly detrimental for

adolescentgirls.Adolescentgirlsare likely to have higherlevelsofidentity

salienceto theroleoffriendship thanboys.Adolescentgirlsreporta higher

numberof peer-relatedstressorsthan boys (Green 1988), and previous

researchon adultsfindsthatbothwomen and men reportreceivingmore

supportfromfriendships withwomenthanfriendships withmen(House et.

al. 1988).Whenroleidentities, such as friendships, have highsalience,the

illeffectsofrolestrainrelatedtotheroleshouldbe exacerbated(Marcussen,

Ritter and Safron2004; Thoits1991). Peer-related stressorsappearto have

a strongerinfluenceon girls'mental health than boys' (Joynerand Urdy

2000; Marcotte,Alainand Gosselin1999). Forgirls,then,largefragmented

networksare likely to be especiallybad. Insum,highly cohesivenetworks

willbuffer thenegativeeffectsofover-integration on depressivesymptoms

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2038 • SocialForces87(4)

forgirlsbutnotboys,and highlyfragmented networkswillexacerbatethe

negative effects

of for

over-integration girlsrelative

to boys.

MediationofOver-Integration

bySocialSupportand SocialBelonging

Previousresearchconsistentlydocuments two linearrelationships:(1.

as networksize increases,so do adolescents' perceptionsof belonging

and support (Haines, Beggs and Hurlbert2002; Walkeret al. 1993);

and (2. as perceptionsof belongingand supportincrease, depressive

symptomsdecrease (Laibleet al. 2000; McNeelyand Falci2004). Ifthis

is the case, then perceptionsof belongingand supportcannotmediate

the hypothesizedassociation between over-integration and depressive

symptoms.Perceptionsof belongingand supportcan onlymediatethe

illeffectsof over-integration

ifover-integration

leads to lower levels of

belonging and support.Although predictpositivelinearrelationships

we

betweennetworksize and perceptionsof belongingand support,we test

the competinghypothesisthatover-integration compromisesperceived

peer supportand the sense of belonging.

TheCurrentStudy

Our researchassesses forthe firsttime the possibilityof a curvilinear

relationshipbetween social integrationand depressive symptomsin

adolescence. Both under-integrated and over-integrated adolescents

are hypothesizedto reporthigherlevels of depressive symptomsthan

adolescents withaverage-sized social networks.However,the effect

of over-integration

on depressive symptomswillvaryas a functionof

both networkcohesion and gender. For girls,large networkswill not

compromisewell-beingiftheyare cohesive. Forboys,however,network

cohesion willnotprotectagainstthe negativeeffectsof over-integration.

Finally,perceptionsof friendsupportand belongingwill mediate the

association between under-integrationand depressive symptoms,but

notthe association between over-integration

and depressivesymptoms.

Higherlevelsofdepressivesymptomsamongover-integrated adolescents

probablyresultfromhigherlevelsofrolestrain,althoughitis notpossible

to testthispotentialmechanismwiththe data used inthisstudy.

Methods

Sample

AddHealthis a stratified

sampleof132 juniorand seniorhighschools inthe

UnitedSates (Udry2003). An in-schoolsurveywas administeredin 1994.

All social networkmeasures are created fromfriendshipsnominations

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and DepressiveSymptoms• 2039

NetworkStructure

collectedinthe in-schoolquestionnaire.Allstudentspresenton the day

of the surveywere asked to listup to ten friends,fiveof each gender.

Studentscould nominatefriendsin or outside of theirschool (of course,

networkmeasurescan onlybe constructedwhenthesenderand receiver

attendedthesame school).Schools providea good approximation ofpeer

social networksin adolescence, because the majority of friendship ties

in adolescence occur withinschool. Withinthis study,68 percent all of

friendship nominationswere sent to a friendat school. Forthisanalysis,

we excluded27 ofthe 132 schools forthefollowing reasons: administrator

refusal to collect network data =

(n 8), data processingerrors(n = 1),

all studentsat the school were enrolledin special education(n=2) and

responserateswere less than70 percent,creatingexcessive missingdata

inthefriendship nominations. We selected thecutoffof70 percentbased

on the recommendation from recentresearchon non-responsein social

networks(Kossinets2006).

Approximately one yearafterthe in-schoolsurvey, an in-homeinterview

was conducted witha nationallyrepresentativesub-sample of 20,747

studentswhowereon theschool rostersorhad been interviewed inschool.

Atthatsame time,a surveywas givento a parent,inmostcases themother.

Allnon-network measuresinthisstudyare drawnfromthein-homesurveys

of the adolescent and parent.The analyticsample forthis researchis

restricted to adolescentswho completedboththe in-homeand in-school

questionnaire. Numerousadolescentsdid notfilloutboththein-homeand

in-schoolsurvey,because adolescents who did notfillout the in-school

surveyweretargetedforthein-homesurvey(n = 5,391). Adolescentswho

attendeda schoolexcludedfromthisstudy,as describedabove (n =1 ,267),

and who were noton school rostersbecause theydid not receivea pre-

assigned ID number(n = 437) are dropped.A pre-assignedID numberis

necessaryforcreatingnetworklinkagesamong actorswithinthe school

friendship network. Furthermore, nomination

a friendship sentto a student

withouta pre-assignedID numberor receivedfroma studentwithouta

pre-assignedID is a missingfriendshipnomination.Adolescents who

had personalnetworksinwhichmorethan30 percentof theirfriendship

nominations were missingare also dropped(n = 1,257).

The sample is restrictedto white,black and Latinoadolescents who

did not reporthavinga same-sex romanticattraction.Excluding1,605

racial minority students increased the likelihoodthat most studentsin

the sample would attendschools withotherstudentsof the same race.

Because adolescent friendship networksare highlysegregated by race

(Moody 2001a), a lack of racialrepresentation withinone's school may

affectthe size and densityof an adolescent's friendship networkwithin

school and possiblymodifythe effectsof networkstructure. Itis beyond

the scope of this researchto investigatethese unique circumstances.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2040 • SocialForces87(4)

Adolescentswho self-identified as havinga same-sex romanticattraction

=

(n 665) are also excluded because we did notwantto conflatetheclose

friendnetworkvariableswitha romanticrelationship. cases were

Finally,

=

lost because theydid not have a validsamplingweight(n 759) or had

missingdata fromthe in-homequestionnaire(n = 269). The finalsize of

the analyticsample is 9,097.

AlthoughAdd Healthhas a good demographicrepresentation of ado-

lescentsinthe UnitedStates,the totalnumberof friendship nominations

among actors in a school is underreported withinthis data set. The distri-

butionof friendship nominationsis truncatedbecause adolescentswere

onlyable to nominatefivesame-genderfriends.Friendship ties occurmore

- -

oftenwithin ratherthanacross gender(Moody2001b). Forthe sample

used in thisstudy,69 percentof girlsused all fivefemalefriendnomina-

tionsand 56 percentof boys used all fivemale friendnominations. These

percentagesincludeschooland non-schoolfriend nominations. Importantly,

nominating friendsoutsideofschool precludedadolescentsfromnominat-

ingfriends withinschool. Because thenumberoffriendship nominations is

underreported, the estimated size of an adolescents' local network willbe

lowerthanthetruepopulationmean (Kossinets2006). Since ourmeasure

ofnetwork size is truncated we expectourfindings on theinfluence ofover-

on

integration depressivesymptoms to be lower bound estimates. In other

words, due to data limitations our will

findings represent a conservative

estimateoftheeffectofover-integration on depressivesymptoms.

Measures

Depressivesymptomsare measuredwitha 15-itemmodifiedCES-D scale.

Consistentwithpreviousresearch,we excluded the fouritems within

the interpersonalsymptomssub-scale of the CES-D (e.g., questions

about feelinglonely)because theyare closelyrelatedto the independent

variablesin this study.The modifiedversionof the CES-D has a range

between1 and 45 withgood reliability

as measuredbyCronbach'salpha(a

= .82). Perceivedbelongingis a three-itemscale developed byBollenand

Hoyle(1990). Studentswere asked how muchtheyagreed or disagreed

withthe followingstatements:you feel likeyou are a partofyourschool,

youare happyto be at yourschool and youfeelclose to people at school.

Response categoriesrangedfrom1, representing "stronglydisagree"to

5, representing"stronglyagree."A confirmatoryfactormodelfitsthedata

well in this sample (McNeely2005). The perceivedbelongingmeasure

rangesbetween 1 and 13 and has good reliabilityfora three-item

scale (a

= .78). Perceivedfriendsupportis measured bya singlequestionasking

the adolescent to indicatehow muchtheythinktheirfriendscare about

them.The response choices rangedfrom1 "notat all"to 5 "verymuch."

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and DepressiveSymptoms• 2041

NetworkStructure

All social networkmeasures are derivedfroman adolescent's local

network, definedas one focalactor(ego) and the actor's directcontacts

(alters). nominatedfriendswho do notattendthe same school haveto

All

be excludedfromthe local network so the networkrepresentsfriendships

within theschool only.Social integration is operationalized bynetwork size.

Networksize is a count of the numberof alterswho make or receivea

friendship nomination fromthefocaladolescent plustheadolescenthim-or

herself. Altersare countedonlyonce, regardlessofwhetherthefriendship

nomination is reciprocated. Wassermanand Faust(1994) callthismeasure

degree, defined as the union of alterswho send and/orreceivea school

friendship nomination to or fromego, plus ego. We use the termnetwork

size because it is more intuitive. Theoretically, networksize can range

from1, indicating thatthe adolescent has neithersent norreceivedany

friendship nominations, to thetotalnumberofstudentsintherespondent's

school minusone. Inpractice,networksize is limitedbythefactthateach

adolescentis onlyallowedto nominatefivefriendsofeach gender.

Network cohesionis operationalized byalter-density, whichassesses the

extentto whichthealters a in local network are friends withone another. It

is calculatedby dividing the actual numberof friendship ties betweenan

adolescent'salters(i.e.,friends) by the total number of possible ties,exclud-

ing in both the denominator and numerator ties with the focal adolescent.

Thealtermatrix was symmetrized, prior to calculating alter-density,to correct

forthe potentially missingnominations due to the rightcensoringoffriend-

ship nominations (Kossinets 2006). We use alter-density as opposed to ego-

densitybecause we do not want to conflate the extent to whicha respon-

dent'sfriendsknowone anotherwiththe respondents'leveloffriendship

reciprocity (i.e.,the extentto whicha friendnominatedbythe respondent

also nominatesthe respondentas a friend). Itis impossibleto calculatethe

alter-density ofa localfriendship network that does nothaveat leasttwo al-

ters.Adolescentswith1 ornoaltersintheirschoolnetwork areassignedthe

valueofzeroforalter-density. Alter-density rangesfrom0, indicating noneof

thefocaladolescent'sfriends arefriends witheach other, to 1, indicatingthat

allofthefocaladolescent's friends are friends with each other.

The measure of a reciprocatedclose friendshipis developed to test

whetherhavinga single close friendis sufficient to preventelevated

depressivesymptomsamong adolescents with few friends. Althoughwe

do nothave data on the closeness of each nominated friendship, we can

takeadvantageoftheorderoffriendship reporting, genderofthefriendship

and whetherthe friendship is reciprocatedto ensurethata modicumof

closeness is presentwithinthe friendship. Respondentswere asked to

nominatetheirclosest male and femalefriendfirst.The firstnomination

could be a romanticrelationshipor a best friend.To avoid confusion

withromanticrelationships, we focus on same-genderfriendshipsand

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2042 . SocialForces87(4)

excludeadolescents who reporta same-sex romanticattraction fromthe

analyticsample. For thisanalysis, an adolescent has a reciprocatedclose

friendship ifthe first friendthey listofthe same gender attends theirsame

school and reciprocatesthe friendship by nominating the adolescent as

a friend.Unreciprocated close friendship indicatesthatthefirstsame-sex

friendnominatedby the adolescent attendsthe same school but does

not reciprocatethe friendshipnomination.Non-schoolclose friendship

indicatesthe firstsame-sex nominatedfrienddid not attendthe same

school. Itis impossibleto determineifthe non-schoolfriendreciprocated.

The omittedreferencecategoryforthese close friendship variablesis the

adolescents who reportedno close friendofthe same gender.

Two additionalfriendship networkmeasures are includedas controls.

First,the numberof nominations made to friendswho do notattendthe

school.On average,adolescentsnominated twofriends who didnotattend

hisorherschool.Withthis control measure, thecoefficientfornetwork size

can be interpreted as the independenteffectof a student'snetworksize

at school. In multivariate analyses,thisvariableis mean-centered because

itinteracts withgender.Second, the numberof missingschool friendship

nominations (i.e.,friendship nominations sentto or receivedfromstudents

whowerenotontheschoolrosterand hencedidnothavea pre-assigned ID).

Morethan80 percentoftheadolescentsinthesampleneither nominatenor

receivenominations fromstudentswithoutID numbers,and an additional

15 percentare missingjustone school friendship nomination.

The following sociodemographic characteristics are included in

multivariate modelsas potentialconfoundersbecause theyare associated

withmentalhealthoutcomes and networkstructure(Eccles et al. 1993;

Moody2001a; Gifford-Smith and Brownell2003): gender,gradeinschool,

race/ethnicity, household income, school size, residentialmobilityand

lengthoftimeincurrentschool. Table 1 reportstheweighteddescriptive

statisticsforthese variables. Household income is based on parental

reportof income on the parentsurvey.Missingvalues forthisvariable

were replacedwiththesample mean(n = 2,072,23 percentofthesample)

and householdincomeis logged inall multivariate analyses. School size

indicates the numberof students attendingthe respondent's school.

Residentialmobility indicatesthenumberofyearstheadolescenthas lived

at hisor hercurrentresidence.Lengthoftimeincurrentschool indicates

the numberofyearstheadolescenthas attendedhisorhercurrent school.

Analytic

Strategy

The social networkmeasureswere createdusingPROC IMLproceduresin

SAS 9.1. OLS regressionmodelstesthypothesesregarding thecurvilinear

relationshipbetween social integrationand depressive symptoms.All

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and DepressiveSymptoms• 2043

NetworkStructure

analyses are run in SAS 9.1 and adjusted forAdd Health's complex

samplingdesign (Chantala2006). Specifically, all analyses are weighted

to adjust forover-samples and nonresponse,and the standarderrors

are adjusted to take intoaccount the stratified samplingplan and the

clustering of students within schools.

The jointtest of curvilinearrelationshipsand interactioneffectsfor

degree, alter-density and gender requiredtestinga four-way interaction.

Inclusionof multipleinteractionterms poses the potentialproblemof

multicollinearity. Several approaches explore potentialmulticollinearity

problems.First, network size is transformed to Z-scoresand alter-density

is mean-centered(Jaccard, Wan and Turrisi1990). The VIFs forthe

interaction termsin the four-way model ranged2-5, whichare highbut

below the acceptable thresholdof 10 (Hairet al. 2006). Second, because

of the presence of multicollinearity, the stabilityof the beta coefficients

is assessed by runningthe four-wayinteractionmodel on randomly

selected sets of halfof the analyticsample (Echambadiand Hess 2007).

These subset analyses replicatedourresults.Third,onlyinteraction terms

in an

thatexplainedadditionalvariance the model,using F-test, kept are

(Kromrey and Foster-Johnson 1998). Finally,additionalanalyses stratified

bygender and levels ofalter-density verifiedthe resultsoftheinteractions.

Applying ordinary least squares regression a skewed dependentvari-

to

able raisestheconcernofpossiblespuriousinteraction terms(Osgood,Fink-

en and McMorris 2002; Haynieand Osgood 2005). Forthisreason,theCESD

is transformed usingIRTmethods(thegradedresponsemodel; Samejima

1969) in Mplus.Then,all analyseswere duplicatedusingthe transformed

CESD (i.e., factorscores fromthe Mplus confirmatory factoranalysis)in

a Tobitregressionmodelwiththe IVE-wareSAS moduleto adjustforthe

complexsurveydesign(Raghunathan, Solenbergerand Van Hoewyk2002).

in

The resultsdid notdiffer significance or effectsize. Forsimplicity and in-

the resultsfromthe OLS regressionare presented.Finally,

terpretability, to

investigate the possibility thatunexplained variation inindividualoutcomes

might be due to unspecified differencesbetween schools random effects

models were estimatedin Stata 9 using the xtreg command. Again,the

resultsdid notdiffer in anysubstantiveway fromthe resultsobtainedus-

ingtheSAS surveyreg procedures.To do an additionalcheckofschoolsize

(range = 26 to more than 3,000 students),analyseswere runon a sample

witha minimum schoolsize of500 students,and theresultsdidnotchange.

Results

Network Statistics

Descriptive

Table 1 reportsweighteddescriptivestatistics.On average,adolescents

nominatedor receivednominationsfromalmost eightfriendsin school

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2044 • SocialForces87(4)

and nominatedabouttwofriendsoutsideofschool.The largestfriendship

networkconsisted of 34 adolescents. The average alter-density is 21

percent. In other 20

words, roughly percent of an adolescent's friends

nominateone anotheras friends.Althoughthe maximumreaches 100

percentforalter-density, few adolescents - just 2 percentof the sample

- reach this level of alter-density.

Althoughalter-density is fairly

skewed,

thereis good variationin networksize across all levels of alter-density

(see AppendixA). The vast majority ofthe sample, 88 percent,identified

at least one same-sex friend.Forty-ninepercentofthose who nominated

a same-sex friend(45 percentof the fullsample) had thatfriendship

reciprocated(i.e., thatstudentalso nominatedthe focal adolescent as a

friend).The remainingadolescents eithermade a nomination thatcould

not be reciprocateddue to the studymethodology(e.g., the studentdid

notattendtheschool) orwas notreciprocated forsome otherreason(e.g.,

the alterdid notperceivethe focaladolescentto be a friend).

NetworkStructure

and DepressiveSymptoms

A primaryhypothesisof this studyis that havingtoo few or too many

friendsis associated withgreaterdepressivesymptoms.The multivariate

modelstestingthishypothesisare presentedinTable2. Allmodelscontrol

forthe numberof friendswho do not attendthe school, the number

of friendsmissingfromthe network,and the followingdemographic

characteristics:grade, gender, race, household income, school size,

numberofyearsat current schooland numberofyearsat current residence.

As expected,Model 1 revealsa curvilinear relationshipbetween network

size and depressive symptoms;adolescents withverysmall and very

largenetworksreportslightly higherlevelsof depressivesymptoms.The

squared termfornetworksize is statistically significantand contributes

additionalvariation(F = 20.03, p < .001). As networksize increases,

depressivesymptomsdecline untilnetworksize reaches approximately

12 friends.Beyond 12 friends,the directionof the association reverses,

and depressivesymptomsincreasealongwithnetworksize. Adolescents

witha networkof 24 friendsexperience,on average,the same level of

depressivesymptomsas adolescents withno friends.

Allmodels inTable 2 also show an intriguing associationbetweenthe

numberof non-schoolfriendsand depressivesymptoms,whichwe veri-

fied in analyses stratifiedby gender.For boys, there is no association

betweenthe numberof nominatedfriendswho do notattendthe school

and depressivesymptoms(b= -.042,ns). Forgirls,the numberoffriends

nominatedoutside the school is positivelyassociated withdepressive

symptoms(Model 1: -.042 + .223 = .181, p < .05). Since we do not

know any characteristicsof these friendsoutside of school, which

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and DepressiveSymptoms• 2045

NetworkStructure

Table 1: WeightedDescriptiveStatistics

St.d. Min Max

Mean/Proportion

Depressive Symptoms 9.61 6.10 1 43

Friendship Network Structure

Networksize3 8.93 4.42 1 34

Alter-density .21 0 1

Reciprocatedschool closefriend .45 0 1

Unreciprocatedschool close

friend .18 0 1

Non-school closefriend .24 0 1

Noclosefriend .12 0 1

Network Control Variables

#Non-school friends 2.14 2.21 0 10

#Missingschool friendnomination .25 .57 0 5

SocialPerception

Perceivedbelonging 9.49 2.55 1 13

Perceivedfriendsupport 4.28 .77 1 5

Demographic Characteristics

Female .52 0 1

Grade 9.35 1.62 6 12

White .75 0 1

Black .17 0 1

Latino .07 0 1

Household income (in$1,000s) 48.12 49.03 1 1000

Missingonhousehold income .20 0 1

Schoolsize 878.14 780.15 26 3334

#ofyears atcurrentschool 2.84 1.61 1 6

#ofyears atcurrent residence 6J54 5.71 0 19

Notes:Standarddeviationsareonlyreportedfornon-dummy variables.

aThecountfornetwork sizeincludesthefocaladolescent.

N = 9097

could include romanticrelationships,it is hard to speculate on why

havingfriendsoutside of school would compromisethe mentalhealth

of adolescent girls.

Models 2 and 3 test the hypothesisthatsmall networksize contrib-

utes to depressed mood even withthe presence of one close same-sex

friend.Model 2 shows the importanceof havinga close same-sex friend.

Comparedto those who do not have a same-sex close friend,havinga

reciprocatedor non-reciprocatedsame-sex close friendinschool is asso-

ciatedwithlowerdepressivesymptomscomparedto adolescentswithout

a same-sex close friend(-.880,p < .01 and -.829, p < .01, respectively).

Havinga same-sex close friendwho does notattendone's school is also

associated withlowerdepressive symptomscompared to adolescents

withouta same-sex close friend(-.660,p < .05). The consistentpatternof

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2046 • SocialForces87(4)

2J

2U

2 io

5fe§SSSSSSS5oS

i"

• *

i" i" r i* i i i i

I

ja

"a>

e ^-^^f^^^CM^-vOO ^^t^- ^^CM ^-.'«- ^-.CD ^^O) ^^LO ^-^CO ^-^OO ^-

^T-cNio^cN^^^c\jir>co^coirjr^ocz>cocDiqo>cocq

§ ©OO C5OC5OO

£

2

SE .q t- ^co in" oo f^c3^ o"o Pco ^cp r^

c ^> o o "

o o cz>

CO J2 i" i" i" i"

~^

CO "55

&- •Co** -»-

Q

O

&

2

I OJ

t5

^

o

i"

o

i"

o

i"

1o .* .* *

o

U CO CVj CO CO CO CO

I iS S

% o

CD

o

1 t^i>^

« u cn oco

"^ -r-; t-|

in

O

o

"3

.3

I

■S -2 o

t

CO "O CO >

3 * *c

"-it

S .3 .3 © 8

I

3 3 3

« I SI

£s co too"ov. co</>co

I ii'llii

to

3 ^

Q. N

'CO

^-^-v^-vf"^

N

'CO

N

'CO

N

'CO

^S

16

O

"CO

5

Q.-?i

-^

g

.^

g

<D

&

g

<D

&

M

<D

&

M

<D

&

M

CD

= § i § § s-s v'Sii'Si

1

O^^-^^O t_ C m m o CD <D

-C<D <D <D CD CD C O ±^ ±^ ±^ ±^ ±f

U-ZZZZD^IDZ<<<<<

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and DepressiveSymptoms• 2047

NetworkStructure

CO

2

g .■

8 g 5 i

5= • I u

* -•- t* -3

o

S 00s ?P5oo)co?oS)£ g

^ CO OOx-f-OT-pCNJLOO ^

5 g '

5 52 * "§

1* 1 Ctf

in .-^f- ^r- -$- ^o> p> g u

t- CO ▼- UO r^"1 +-•

O O• O t- g ej

i" 1' a <u

I £3

cn f^^i o^ cFo5 r^ o to g oj

-«- o <+-.

<+h

^

o co in

O CD O t- *t3 O

O h^CNJ O^CNI CO*CO f^-r- LO ^ 'n

OOCMt-t-t-CO^-COO <U 5

8a

5 8 5 ¥? f g

i ^ 38

^coSc^ScoSf^^fe <^S

OOCMt~Ot-OOt-COO ^£ (D

ON <L> O

o >%73

* ?SSv

I IIIs

1 ic m*

s| {I

CO -g & C iiil ^ ai *

I U i i §11°

1 51 i 1

I

Kl IIK

f 11 I 1 18251^

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2048 • SocialForces87(4)

associationacross the close friendship variablesindicatesthathavinga

close same-sex friendis protective, regardlessofwhetherthe friendship

is reciprocatedor whetherthe friendattendsthe same school. Model 3

shows thatalthoughhavinga close friendprotectsagainst depressive

symptoms,it does not attenuatethe association between networksize

and depressivesymptoms.Thus,the effectsof havinga friendand net-

worksize appear to be additive.One friendis protective,but each addi-

tionalfriendis incrementally better,up to roughly11 friends.

Model 4 shows the additiveeffectsof networksize and alter-density

on depressive symptoms.The influenceof alter-density on depressive

symptoms varies = <

by gender(b -1.968, p .05). Amonggirls,having

a higherproportion of friendswho are also friendswithone anotheris

associated withlowerlevelsofdepressivesymptoms.Alter-density does

not have a significant effecton depressivesymptomsamong boys (b =

.363, ns). The finalmodel in Table 2 investigateswhetherthe negative

effectofover-integration is exacerbatedamongadolescentsinfragmented

friendship networks (i.e.,networks withlowalter-density),and ifthiseffect

is strongeramong girls.This hypothesisimpliesa four-wayinteraction

between alter-density, the quadratictermfornetworksize and gender.

The four-wayinteractionexplains additionalvariance in the model (F =

7.53, p < .01). To ease interpretation, Figure2 visuallydisplaysthe results

fromModel 5. The dashed lines show the predictedvalues forgirlsand

the solid linesshow the predictedvalues forboys.The linesmarkedwith

a diamondsymbol♦ representadolescents withfragmentednetworks

(~ 10% alterdensity;the25thpercentile foralter-density)

and theunmarked

lines representadolescents withmore cohesive network(-30% alter-

densitythe 75thpercentileforalter-density). The totalheightofthe graph

representstwo-thirds of a standarddeviationfordepressivesymptoms.

Foradolescentgirls,largenetwork size inconjunctionwitha fragmented

social networkis associated with the highest levels of depressive

symptoms(dashed markedline). In contrast,high networkcohesion

protects girls in large networksfromdepressive symptoms(dashed

unmarkedline).Largenetworksize is notassociated withelevatedlevels

of depressive symptomsforgirlswhose friendsare friendswitheach

other.Foradolescent girls,thereis no such thingas too manyfriendsin

a cohesive network, at least intermsof predicting depressivesymptoms.

Amonggirls who have 12 friends,thereis about a one-fifth of standard

deviationdifferencein depressive symptomsbetween girlswho are in

fragmented networksand those incohesivenetworks. These higherlevels

of depressivesymptomsoccur among roughly20 percentof adolescent

girlsin the sample who have networkswith 12 or more friends.It is

important to keep in mindthatdue to data limitations we underestimate

the true size of adolescent friendshipnetworks.Furthermore, in this

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and DepressiveSymptoms• 2049

NetworkStructure

acrossValuesof

Figure2. PredictedValueofDepressiveSymptoms

Alter-Densityand Network Size byGender

12.5

115__ +.-

-♦■•♦

1q. ..::-.;•. =L-^___

1Q5

3) **• „ s

^^ ^ *

* *

m% 9.5 ^ m^^T

0> ^^^^

^^^^^^^"^^ ^ b ww||f

jgj , . , , , , , , , , ,

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21

Network

Size

" ♦ Females: networks- - Females: networks

cohesive

fragmented

networks - Males:cohesive

m^mMales:fragmented networks

sample, the average size of a network is almost nine friends,which is

where the divergence in depressive symptoms across values of alter-

density begins (see Figure2).

The story is quite differentfor boys, represented by the solid lines in

Figure 2. For adolescent boys, large network size in conjunction with a

fragmentedsocial networkis associated withthelowest levels ofdepressive

symptoms (solid marked line). This opposing trend compared to girls is

clearlyvisible in Figure 2; compare the dashed marked line to the solid

marked line. As networksize increases, boys with fragmented networks

and girls with cohesive networks experience declines in depressive

symptoms.Among boys withcohesive networks(solid unmarkedline),the

association between networksize and depressive symptoms is curvilinear.

Havingtoo few or too manyfriendsis associated withelevated depressive

symptoms. Adolescent boys in cohesive networkswith roughly10 friends

reportthe lowest levels of depressive symptoms. The differencebetween

adolescent boys with no friends and boys with 10 friends is about two-

fifthsof a standard deviation fordepressive symptoms.

In sum, over-integrationis associated with higherlevels of depressive

symptoms among girlswith fragmented networks and among boys with

cohesive networks. In contrast, adolescent girls with large cohesive

networks and boys with large fragmented networks tend to have the

lowest levels of depressive symptoms. These findings,however, should

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2050 • SocialForces87(4)

be interpretedwitha modicumof cautionbecause Model 5 shows signs

The standarderrorsforalter-density

of multicollinearity. and networksize

4

between models and 5 increase, and the VIF scores range2-5 forthe

termsinModel 5. The randomly

interaction selected subset analysesand

analyses stratifiedby gender and levels of alter-densitydo confirmthe

resultsof Model 5.

Do Social Belongingand PeerSupportMediatetheEffects

of

Under-Integration?

Thefinalhypothesisis thatsocial belongingand friend supportmediatethe

relationship between havingfew friendsand depressivesymptoms.For

thisto be true,belongingand supportneed to be relatedto bothnetwork

size and depressivesymptoms.Table 3 demonstratesthe relationship of

social belonging and friend support to network size. The relationshipwas

expectedto be linear;however, as showninTable3, non-linear associations

are present.Including the squared termfornetworksize in models 1 and

2 explainsadditionalvariationin bothperceivedbelonging(Model 1, F =

29.47,p < .001) and perceivedfriend support(Model2, F = 25.90,p < .001).

The nonlinear associationstaketheformofa diminishing returns effect.As

networksize increases,levels of perceivedbelongingand friendsupport

also increase,but onlyto a certainpoint.For perceivedbelonging,the

curveflattensout once the numberoffriendsan adolescent has exceeds

approximately 18 friends.Forperceivedfriendsupport,the slope of the

curveflattensout once the numberoffriendsan adolescent has exceeds

approximately 13 friends.Importantly, havinga large networkdoes not

appear to compromiseperceivedbelongingand friendsupport; rather,

aftera certainpointthereis no added benefitto havingan additionalfriend.

The second requisitefora mediatoris an associationwiththe depen-

dentvariable.Model 1 inTable4 shows thatbothsocial belongingand peer

supportare negatively relatedto depressivesymptoms.Adolescentswith

higherlevelsof perceivedbelongingand supportreportfewerdepressive

symptoms.The remaining models inTable4 test the hypothesisthatper-

ceivedbelonging supportmediatetheassociationbetweenhavingfew

and

friends and depressivesymptoms.As statedpreviously, these variablesare

expectedto mediatetheilleffectsofhavingfewfriends, butnottheilleffects

oftoo manyfriends. Model2 shows thatthecurvilinear associationbetween

network size and depressivesymptomsdisappearswhenperceivedbelong-

ingand supportareincludedinthemodel.Thesquaredtermfornetwork size

does notexplainadditional variationinModel2 (F = 2.16, ns).Model3 drops

thesquaredtermto reveala significant linearassociationbetweennetwork

size and depressivesymptoms, controllingforperceivedbelongingand sup-

oort.The associationis smallbutpositive(b = .187, p < .05); adolescents

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and DepressiveSymptoms• 2051

NetworkStructure

Table 3: Unstandardizedand Standardized OLS RegressionCoefficientsof

Perceptionsof Social Relationshipson NetworkStructure

Perceived Perceived

BelongingFriend Support

Model1 Model2

Network

Friendship Structure b beta b beta

size

Network .100***.14 .492*** .20

(.02) (.06)

size*network

Network size -.025**-.07 -.091***-.07

(.01) (.02)

school

Reciprocated closefriend3 .002 .00 .086 .02

(.04) (.15)

school

Unreciprocated -.060 -.03 .210

closefriend3 .03

(.05) (.15)

closefriend3

Non-school -.040 -.02 -.010 .00

(.04) (.15)

Alter-density .163** .05 .289 .03

(.06) (.19)

Control

Network Variables

friends

#Non-school .025** .07 -.022 -.02

(.01) (.03)

female

friends*

#Non-school -.016 -.03 -.070t -.04

(.01) (.04)

nomination.005 .00 .006

friend

school

#Missing .00

(.02) (.07)

Female .229***.15 -.163t -.03

(.02) (.10)

Intercept 3.820 9.980

R-squared .OK .057

Notes:Standarderrorsarein parenthesesall analysesareadjustedforcomplex

samplingdesignand each model controlsforgrade,race,householdincome,school

size,#ofyearsatcurrentschooland # ofyearsatcurrent residence(N = 9097).

aTheomittedreferencecategoryis nothavinga schoolclosefriend

fp<.10 *p<.10 **p<.05 ***p<.01

withlargernetworksreportmoredepressivesymptoms.As expected,per-

ceivedbelongingand supportmediatethe illeffectsofsmallfriendship net-

worksbutnotlargeones, inwhich depressivesymptoms remain elevated.

The higherlevels of depressive symptomsamong adolescents with

manyfriendscannot be explainedby the extentto whichtheyperceive

belongingat school or perceivesupportfromtheirfriends.Furthermore,

in Model 4 of Table 4, the four-wayinteractionstillexplains additional

inthe model,overand above theeffectofbelongingand support

variation

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2052 • SocialForces87(4)

(F = 8.64, p < .01). The differential

effectsof over-integration

across

gender and levelsof network cohesion do notdisappearuponcontrolling

forperceivedbelongingat school orperceivedsupport.Adolescentgirlsin

largefragmented networksreporthigherlevels of depressivesymptoms

compared to girlswithlarge cohesive networks,whereas adolescent

boyswithlargecohesive networksreportthe highestlevelsofdepressive

symptomscomparedto boys withlargefragmented networks.

ws ^ oincoincocococ^CNj

I

C0 *gC\|f- OC5OC5OOOOO

" " "

'* '" •" ■" •" ■" «"

^. _Q

5o icm.^m{

I

^-^ cn .-^o ^^t- ^^o ^-^o ^-^cn ^-^oo ^-^^- ^^cm ^~

Sffl(pqr-r; CI>^^OC\JC\JCNT-;^rCNJ'^C\JTtCOph-:Cpa

I -

I

S*O ur>^-vco^^r^-^-^ oo ^-^Xn ^-.o ^^i-^ ^^^- --

Q

l*-0^?"^ "§. ^ R^ ^s ^« ^fe g

(A

I £ ^> * *

O O CO ^O) ^-^ O /-sN ^-^ CO ,->O) ^-^h^ ^- ^O .- »t- ^~

8. 1 ^-"coot-v- t-ii-ocz) TtcN^cNj'^coinLqcq^

If

I! 1 I !

i!

W ^+^

I* **-^ T-I ■

I

- '*"

N) O

H 3

« o

"2 ~

£ 111

, « *=

3

"S S 1 5 -8 i §

cf | | 11 | i 1I

3 2

2 «

1

|l I is § § § i 1 | & h

2

"*1

a«

O l_ C_ Q> ^ -^ ^ -^ O 2_ CI (D <D

OQ> O'iZCD CD d> CD CD C o 4=« ■»=«

COO- Q- U_Z Z Z Z 0£ 3 Z < <

H o

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and DepressiveSymptoms• 2053

NetworkStructure

Discussionand Conclusion

This articlereexaminedthe association between social integration and

mentalhealth.The association between social integration on depressive

symptomsis curvilinear. Consistentwithmuchpreviousresearch,under-

integration (i.e., havingtoo few friends)is associated withhigherlevels

ofdepressivesymptoms(Brendgenet al. 2000; Ueno 2005). Furthermore,

under-integration is associated with elevated depressive symptoms,

r- t- "^- CD O CO "*- OO

• i-

.-.•-.• §> o

OOOO O O O r« *+-•

* '55 ^

oo oo^oo co^ud oTco ^ oPcooTSinoPSS bo §

r **j* \ - ^ ' - ^ --i - ^ ' ^-^ " - '" i" - ^

csi - -'o i 2

CM

g,^O

§ S 5 £; \l

* p| Uk

t- ^^IjD ^-^CO ^-v<3 .- sS O> CJ p.

8 S 5 ^ ^ L

<=?t "? "^ f^ -5 i»

N

I

N

l\ h

<U U ^

v

•c75 a5 ^ 2 O,

-ill - i^ .aJ

§

rCD •<D *<D »25 -i -I -s 8 2?q

CD 52c: 0><+H/,t'HV

.n .n .n .n E o jh ^ g g

s

1 1 1

CDCDCDCDOCDCD-s:

5 >"S "S i gosgo *-• t^ »- •

I I I I "I! | •§ -i ^ § « -S« 1 o

i <i <i <£ Z*II

<

I% i* iT1 llllijv

^Qi^^S^^ (^4 Cd ^ « ■»-

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2054 • SocialForces87(4)

regardlessof the presence of a close friend.Adolescentsneed multiple

friendships to meettheirrelationship needs (Crosnoeand Needham2004;

Crosnoe and McNeely2008). Havingone close friendis not enough to

wardofftheilleffectsofunder-integration. As predicted,under-integration

is equallybad forboysand girls.Thisfinding is consistentwithqualitative

evidencethatadolescent boys desireclose relationswithpeers as much

as girlsdesireclose relations(Chu 2005).

This is the firststudyto our knowledgeto test the hypothesisthat

over-integration increasesdepressivesymptomsand to provideempirical

evidenceinsupportofthe theoreticalclaimthathavingtoo manyfriends

maycompromisementalhealth.Over-integration to lead to higher

is likely

levelsofdepressivesymptoms,due to higherlevelsofrolestrainplacedon

adolescents attempting to meetthe obligationsofnumerousfriends.Itis,

however,important to contextualizeover-integration because itseffectson

depressivesymptomsvaryas a function ofgenderand networkcohesion.

Amongadolescents girls,over-integration is associated withhigherlevels

of depressivesymptomsonlywhen networksare fragmented(i.e., few

ofan adolescent's friendsare friendswitheach other).Incontrast,highly

cohesive networksprotectagainst developing depressive symptoms

among girlsin over-integrated networks.Among girls,social networks

can be largeas long as the adolescent's friendstend to be friendswith

one another.For boys, over-integration is associated withan increase

in depressivesymptomswhen networkcohesion is high.In contrastto

adolescentgirls,adolescentboysinlargefragmented networksreportthe

lowest levels of depressivesymptoms.Forboys, low levels of network

cohesion protectagainstthe potentialilleffectsof over-integration.

These findingshave importantimplications.First,researcherstradi-

tionallyfocus on studyingadolescents withfew social ties. However,we

cannotassume thatteenswitha lotoffriends, and who maybe quitesocial,

are not experiencingdepressivesymptoms.Second, adolescents experi-

ence social networksholistically. Breakingdown each particular network

characteristics intoa set of additive,independentvariablesmaynotaccu-

ratelycapturetheinfluence ofnetwork characteristics on adolescenthealth.

Theoreticallygroundedhypothesesabout how a constellationof network

characteristics jointlyinfluenceadolescent healthwillhelp advance our

understanding inthisnascentlineof research.Third,the gatheringoffull

ranknetwork datawillalso be important foradvancingthisfieldofresearch.

Withinthisresearch,itwas the social ties of an adolescent's friends(net-

workcohesion)thatprovidedthe most insightintothe curvilinear associa-

tionbetweennetworksize and depressivesymptomsinadolescence.

Can perceptionsof belongingand supportfromfriendsmediatethe

effectsof under-and over-integration on depressive symptoms?The

answeris yes and no. The perceptionofbelongingand supportexplained

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and DepressiveSymptoms• 2055

NetworkStructure

one end ofthesocial integration continuum, butnottheother.Adolescents

withfew or no friends(i.e., under-integrated) reportedlower levels of

perceivedsupportand belonging; and these perceptionsmediatedthe

associationbetweenunder-integration and depressivesymptoms.Forthe

mostpart,havingmanyfriends (i.e.,over-integration) does notcompromise

of

positiveperceptions support and belonging. As a result,perceptionsof

social relationships did not mediatethe illeffectsof over-integration on

depressivesymptoms.

Thefindings fromthisresearchshouldbe consideredwithin thelimitations

ofthe research. First,the measure of network size is truncated due to the

10 friendnominationlimit;thereby,underestimating both the size and

cohesiveness of an adolescent's network, especiallyamong adolescents

withlargernetworks.Despite thisunderestimation, a curvilinear effectof

networksize on depressivesymptoms is found. Second, the complexity

of the statisticalmodels,in particular the four-way interaction, raises the

of

possibility multicollinearityproblems. For these reasons, the findings from

thisresearchshould be consideredpreliminary untilfutureresearchcan

replicatethese results.The modelswithtwo-wayinteraction termsappear

notto sufferfrommulticollinearity; therefore, we are confidentthatthe

associationbetweennetworksize and depressivesymptomsis curvilinear

and thatnetworkcohesion providesmore protectionagainstdepressive

symptomsforgirlsthan boys. Finally, networkstructureis assumed to

be causallylinkedto perceptionsof social relationships and depressive

Itis

symptoms. possible thatdepressed adolescents are inclined to socially

isolatethemselves from or be isolated by other students at school (Link

et al. 1989). Withregardto over-integration, however, it is less likelythat

depressedadolescentswillselectthemselvesintoover-integrated networks.

Inspiteofthese limitations, thisresearchadds to the limitednumberof

studies on the association between social networkstructure and mental

healthbyproviding empiricalevidenceforthe oftentheorized effectsof ill

over-integration on depressivesymptoms(Durkheim1951; Pescosolido

and Levy 2002). Furthermore, the importantanceof investigatinga

constellationof networkcharacteristics,such as interactionsbetween

social integration and networkcohesion,is shown.We also demonstrate

thata similarconstellationsofnetworkcharacteristics can be experienced

in dramatically differentways by boys and girlsand, as a result,foster

different developmentaloutcomes.

Notes

1. Ueno (2005) did graph mean differencesin depressive symptomsacross

networksize and founda lineartrend.Althoughour studyuses the same

data as Ueno (2005), our measureof networksize differsand we engage in

illeffectsofover-integration.

a morerigorousempiricaltest ofthe potentially

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2056 • SocialForces87(4)

Ueno (2005) measured networksize withthe numberof sent-friendship

nominations. This measure reliessolelyon self-reportsand is capped at 10

possible nominations. Respondents inAdd Healthwere allowed to nominate

fivefriendsof each genderfora maximumof 10 friends.Our measure of

networksize draws on information fromboth the numberof friendship

nominations madeand thenumberreceivedfromotherstudentsintheschool.

Ourmeasureovercomesthe limitations ofself-reportdata and surpasses the

artificial

ceiling of a network size of 10 friends. We believe incorporating

information fromboth sent and received friendshipnominationsmore

accuratelyassesses thesize ofan adolescent'sfriendship network, especially

largenetworks.Over-integrated adolescents mighthave listedmorefriends

iftheywere giventhe opportunity to do so.

References

Anderson,Robert.2001. "Deaths: Leading Causes for 1999." National Vital

StatisticsReport;Volume49, Number 11. Hyattsville,

MD: NationalCenter

forHealthStatistics.

Baumeister,Roy R, and Mark R. Leary.1995. "The Need to Belong: Desire

for InterpersonalAttachmentsAs a Fundamental Human Motivation."

PsychologicalBulletin117(3):497-529.

Beam, Margaret R., VirginiaGil-Rivas,Ellen Greenbergerand Chuansheng

Chen. 2002. "Adolescent Problem Behaviorand Depressed Mood: Risk

and ProtectionWithinand Across Social Contexts."Journalof Youthand

Adolescence 31(5):343-57.

Belsher,Gayle,and Charles G. Costello. 1988. "Relapse AfterRecoveryFrom

UnipolarDepression:a CriticalReview."PsychologicalBulletin104(1):84-96.

Bollen,KennethA.,and RickH. Hoyle.1990. "PerceivedCohesion:A Conceptual

and EmpiricalExamination."Social Forces 69(2):479-504.

Brendgen,Mara,FrankVitaroand WilliamM. Bukowski.2000. "DeviantFriends

and EarlyAdolescents' Emotionaland BehavioralAdjustment."Journalof

Researchon Adolescence 10(2):173-89.

Burt,Ronald.S. 1998. "The Gender of Social Capital."Rationality

and Society

10(1):5-46.

Chantala, Kim. 2006. Guidelines forAnalyzingAdd Health. Chapel Hill,NC:

CarolinaPopulationCenter.

Chu,JudyY. 2005. "AdolescentBoys' Friendships

and PeerGroupCulture."New

DirectionsforChildand AdolescentDevelopment2005(107):7-22.

Crosnoe,Robert,and Clea McNeely.2008. "PeerRelations,AdolescentBehavior,

and Public Health Research and Practice."Familyand Community Health

31(Supplement1):S71-S80.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and DepressiveSymptoms• 2057

NetworkStructure

Crosnoe, Robert,and Belinda Needham. 2004. "Holism, ContextualVariability,

and

the Study of Friendships in Adolescent Development." Child Development

75(1):264-79.

Durkheim,Emile. 1951. Suicide. Free Press.

Eccles, Jacquelynne S., Carol Midgley,Allan Wigfield,ChristyMiller Buchanan,

David Reuman, Constance Flanagan and Douglas Mac Iver. 1993.

"Development During Adolescence: The Impact of Stage-Environment Fit

on Young Adolescents' Experiences in Schools and in Families." American

Psychologist 48(2):90-1 01 .

Echambadi, Raj, and James D. Hess. 2007. "Mean-Centering Does Not Alleviate

CollinearityProblems in Moderated Multiple Regression Models." Marketing

Science 26(3):438-45.

Eder, Donna. 1985. "The Cycle of Popularity: Interpersonal Relations Among

Female Adolescents." Sociology of Education 58(3): 154-65.

Eder, Donna, and Janet L. Enke. 1991. "The Structureof Gossip: Opportunities

and Constraints on Collective Expression Among Adolescents." American

Sociological Review 56(4):494-508.

Eder, Donna, Catherine C. Evans and Stephen Parker.1995. School Talk: Gender

and Adolescent Culture. Rutgers UniversityPress.

Ennett,Susan T., KarlE. Bauman, Andrea Hussong, Robert Faris,Vangie A. Foshee

and Li Cai. 2006. "The Peer ContextofAdolescent Substance Use: FindingsFrom

Social NetworkAnalysis."Journalof Research on Adolescence 16(2): 159-86.

Fagot, Beverly I. 1985. "Beyond the Reinforcement Principle: Another Step

Toward Understanding Sex Role Development." Developmental Psychology

21 (6): 1097-1 104.

Formoso, Diana, Nancy A. Gonzales and Leona S. Aiken. 2000. "FamilyConflict

and Children's Internalizing& Externalizing Behavior: Protective Factors."

American Journalof CommunityPsychology 28(2): 175-99.

Friedkin,Noah E. 2004. "Social Cohesion." Annual Review ofSociology 30 A09-25.

. 1984. "Structural Cohesion and Equivalence Explanations of Social

Homogeneity." Sociological Methods and Research 12(3):235-61 .

Frydenberg,Erica, and Lewis Ramon. 1993. "Boys Play Sport and GirlsTurnto

Others: Age, Gender and EthnicityAs Determinants of Coping." Journal of

Adolescence 16(3):253-66.

Furman,Wyndol,and Duane Buhrmester. 1992. "Ageand Sex DifferencesinPerceptions

of Networksof Personal Relationships."ChildDevelopment 63(1):103-15.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2058 • SocialForces87(4)

Gecas, Victor. 1986. "The Motivational Significance of Self-Concept for

Socialization Theory." Pp. 131-56. Advances in Group Processes: Theoryand

Research, Volume 3. E.J. Lawler,editor.JAI Press.

MaryE., and Celia A. Brownell.2003. "Childhood Peer Relationships:

Gifford-Smith,

Social Acceptance, Friendships, and Peer Networks." Journal of School

Psychology 41(4):235-84.

Greene, A.L. 1988. "Early Adolescents' Perceptions of Stress." The Journal of

EarlyAdolescence 8(4):391-403.

Haines, Valerie A., John J. Beggs and Jeanne S. Hurlbert.2002. "Exploringthe

StructuralContextsofthe Support Processes: Social Networks,Social Statuses,

Social Support, and Psychological Distress." Pp. 269-92. Social Networksand

Health. JudithA. Levyand Bernice A. Pescosolido, editors. JAIPress.

Hair,Joseph R, Ronald L. Tatham, Rolph Anderson and William C. Black. 2006.

MultivariateData Analysis. Prentice Hall.

Hansell, Stephen. 1985. "Adolescent FriendshipNetworksand Distress in School."

Social Forces 63(3):698-71 5.

Haynie, Dana L. 2001. "Delinquent Peers Revisited: Does Network Structure

Matter?"American Journal of Sociology 106(4): 101 3-57.

Haynie, Dana L, and D.W. Osgood. 2005. "Reconsidering Peers and Delinquency:

How Do Peers Matter?" Social Forces 84(2): 1 109-30.

House, James S., Debra Umberson and Karl R. Landis. 1988. "Structures and

Processes of Social Support." Annual Review of Sociology 14:293-318.

Ibarra,H. 1997. "Paving an AlternativeRoute: Gender Differences in Managerial

Networks." Social Psychology Quarterly60(1 ):91 -102.

Jaccard, James, Choi K. Wan and Robert Turrisi. 1990. "The Detection and

of InteractionEffectsBetween Continuous Variables in Multiple

Interpretation

Regression." MultivariateBehavioral Research 25(4):467-78.

Joyner,Kara, and J. Richard Udry.2000. "You Don't BringMe Anythingbut Down:

Adolescent Romance and Depression." Journalof Health and Social Behavior

41(4):369-91.

Kandel, Denise, Victoria Raveis and Mark Davies. 1991. "Suicidal Ideation in

Adolescence: Depression and, Substance Use and Other Risk Factors."

Journalof Youthand Adolescence 20(2):289-309.

Kossinets, Gueorgi. 2006. "Effects of Missing Data in Social Networks." Social

A/e/wwte28(3):247-68.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 16:21:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and DepressiveSymptoms• 2059

NetworkStructure

Kovacs, Maria,TerryFeinberg,MaryAnnCrouse-Novak,Stana Paulauskas and

1984. "DepressiveDisordersinChildhood:A Longitudinal

RichardFinkelstein.

ProspectiveStudy of Characteristicsand Recovery."Archivesof General

Psychiatry41(3):219-39.

Kromrey,JeffreyD., and LynnFoster-Johnson.1998. "Mean Centeringin

Moderated MultipleRegression: Much Ado About Nothing."Educational

and PsychologicalMeasurement58(1):42-67.

Laible,DeborahJ.,GustavoCarloand Marcela Raffaelli.2000. "The Differential

Relationsof and

Parent PeerAttachment to AdolescentAdjustment."Journal

of Youthand Adolescence 29(1):45-59.

PE. Shroutand B.P Dohrenwend.1989.

Link,BruceG., FT.Cullen,E.L. Struening,

"A ModifiedLabelingTheoryApproachto Mental Disorders: an Empirical

Assessment."AmericanSociologicalReview 54(3):400-23.

Marcotte, Diane, Michel Alain and Marie-Josee Gosselin. 1999. "Gender