Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kumar 2012

Uploaded by

iggy hadidOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kumar 2012

Uploaded by

iggy hadidCopyright:

Available Formats

International Business Review 21 (2012) 1190–1191

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

International Business Review

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ibusrev

Book review

R. Kumar, V. Worm, International Negotiation in China and India: A Comparison of the Emerging Business Giants,

2011189 pp., ISBN: 978-0-230-24594-5

The authors Rajesh Kumar and Verner Worm are well known scholars in cross-cultural negotiation research. Their new

book provides a valuable reference to understanding the negotiation styles of two of the world’s major economies: India and

China. Though there is abundance of literature on national negotiation styles, the authors push the literature forward by

linking institutional environment of a country to its unique negotiation dynamics. The book addresses cross-cultural

negotiation issues that are of utmost significance in today’s increasingly complex business environments, more so as both

India and China are on their way to become economic powerhouses. Goldman Sach suggests that India could be the world’s

third largest economy by 2035 (next only to USA and China) with China taking the lead by becoming world’s largest economy

by 2041 (Wilson & Purushothaman, 2003).

Even though India and China differ a lot in terms of their political environment and cultural traditions, their comparison

has lately become an area of interest (Das, 2006); the present book furthers this approach. While Kumar has continued with

his earlier work Doing Business in India (Kumar & Sethi, 2005), Worm’s subtle understanding of the Chinese culture, markedly

shown in his earlier works (e.g., Worm, 1997), gets reflected in the present book. Akin the nature of elephant, the Indian

economy has grown at a gentler pace, contrastingly different from its northern neighbour China which, like a dragon, has

‘‘grabbed the benefits of globalization (FDI, exports, education and skills) without singeing it with its fiery breath’’(Virmani,

2006, p. 298). Are these economic giants very different in nature; or are they joined by a thread of unity? Kumar and Worm

attempt to answer these questions by analysing the historical linkages between the two countries and decoding how they

differ.

The book is divided into ten chapters that deal with different topics. The authors ground their work in institutional

framework choosing its three pillars (i.e., regulatory, normative, and cognitive) to explain how negotiation practices across

the two nations are related as well as separated. The first chapter (Chapter 1) underlines the relevance of institutional

perspective to understanding cultural and negotiating practices of a nation. Spelling out their intention to ‘‘develop a

comprehensive framework for understanding cross-cultural negotiations’’ (p. 3); the authors identify the key elements of

institutional theory besides highlighting their implications. In the next chapter (Chapter 2) readers are presented a brief

history of the two nations: the trial to understand cross-cultural negotiations through the lens of historical enquiry is a

welcome addition that few scholars try despite the merit associated with such historical probes (Fang, 1999; Fang, Fridh, &

Schultzberg, 2004). The authors emphasize that while religious thoughts and colonial experiences have shaped Indian

negotiating behaviour (pp. 26–27), understanding China’s 4000 years of continuous history and its current focus on reducing

income differences (p. 33) is important to comprehend the Chinese approach to negotiations.

Discussing institutional environment of India (Chapter 3) the authors underline the importance of bureaucracy, the

structure of the Indian judicial system, and the nature of the Indian political class. The issue of corruption is discussed with

reference to the close nexus between bureaucrats, industrialists and the politicians. Dealing with Chinese institutional

environment (Chapter 4), the authors note that being a single party governed country, it is easier to ward off the liability of

gratifying multiple stakeholders. Moreover, as hierarchy is highly valued in the party system and a decision taken at top level

is respected without much inquiry, the Chinese bureaucracy is less risk-averse. The subsequent chapters deal with the

requisite negotiation behaviour in the Indian (Chapter 5) and the Chinese context (Chapter 6). Next, the authors provide case

studies designed to emphasize the institutional environment of India (Chapter 7) and China (Chapter 8). The institutional

environment of India is portrayed through the help of cases dealing with large organizations like Enron, Union Carbide, and

the WTO. The WTO case is common to both nations and would help readers do a comparative analysis of political climate’s

effect on institutional environments of the two countries. The other two cases in the Chinese institutional environment are

that of Rio-Tinto and Google. Barring the WTO case, all the four cases discussed are of those business agreements that were

marked with initial or terminal failures; for instance while Enron was a global failure (McLean & Elkind, 2003), Union Carbide

contributed to one of the world’s deadliest industrial disaster in history (Lapierre & Moro, 2002). While these cases would

help readers get a fine understanding of how not to negotiate in the two countries, inclusion of case studies where the

0969-5931/$ – see front matter

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2012.09.001

Book review / International Business Review 21 (2012) 1190–1191 1191

business agreements were smoother or where the government played a nominal role could have added to a diverse reading.

Chapter 9 recapitulates the learning from the preceding chapters: it contains important lessons put-in in a highly sumptuous

manner. The concluding Chapter 10 discusses the limitations of the book.

A shortcoming of the book is that the authors have discussed the institutional environment at country level without

taking heed of intra-national differences. India and China are vast countries with many regional and sub-regional variations.

Given these differences, a question emerges: is any generalization about the Indian and the Chinese negotiation styles

possible? Question can also be raised about generalization of individual negotiation styles. Cross-cultural negotiations are

full of pitfalls; and as Fang (1999) argues, cross-cultural negotiation processes are often marked by fluidity and inherent

paradoxes that can only be understood in their situational context. The generalization or the stereotypical portrayal of

negotiating behaviour could well have its roots in the etic approach with which scholars often analyse negotiating situations:

much concerned with literal understanding of explicit situations, we fail to decode their contextual meaning (Li, Leung, Chen,

& Luo, 2012; Tsui, 2006). Such an etic approach to understanding cultural characterises leads to identification of the Indian

negotiator as being too idealistic (p. 141) or the Chinese negotiator as being highly pragmatic (p. 144), while in reality, their

conduct could be shaped by contextual factors. Though the Yin Yang thinking which emphasizes the coexistence of

seemingly contradictory negotiation behaviour finds a mention in the book, we believe that a fuller discussion of the Yin

Yang perspective (e.g., Fang, 2012) and its effect on the negotiating style and environment of the two multicultural nations

would have been worthwhile. Another area of the book that could be further improved is the structure: quite often it appears

that one is reading two different books that are merged into one. Nonetheless, these are not fatal flaws but ones which we

hope the reader should be aware of.

Despite the shortcomings, the book makes a very interesting contribution to the study of negotiation studies. The book

would be a worthwhile read for researchers, academics, students, and managers alike, and would help them tame the two

giants, the Elephant and the Dragon, with better negotiation counterstrategies.

References

Das, D. K. (2006). China and India: A tale of two economies. Abingdon, Oxon/New York: Routledge.

Fang, T. (1999). Chinese business negotiating style. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Fang, T. (2012). Yin Yang: A new perspective on culture. Management and Organization Review, 8(1), 25–50.

Fang, T., Fridh, C., & Schultzberg, S. (2004). Why did the Telia–Telenor merger fail? International Business Review, 13(5), 573–594.

Kumar, R., & Sethi, A. K. (2005). Doing business in India: A guide for western managers (1st ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lapierre, D., & Moro, J. (2002). Five past midnight in Bhopal. New York, NY: Warner Books.

Li, P. P., Leung, K., Chen, C. C., & Luo, J.-D. (2012). Indigenous research on Chinese management: What and how. Management and Organization Review, 8(1), 7–24.

McLean, B., & Elkind, P. (2003). The smartest guys in the room: The amazing rise and scandalous fall of Enron. New York: Portfolio.

Tsui, A. S. (2006). Contextualization in Chinese management research. Management and Organization Review, 2(1), 1–13.

Virmani, A. (2006). Propelling India from socialist stagnation to global power. New Delhi: Academic Foundation.

Wilson, D., & Purushothaman, R. (2003). Dreaming with BRICs: The path to 2050 (Global Economics Paper No. 99): Goldman Sachs.

Worm, V. (1997). Vikings and mandarins: Sino-Scandinavian business cooperation in cross-cultural settings. Copenhagen: Handelshøjskolens forlag.

Kunal Kamal Kumar*

Indian Institute of Management (IIM) Indore, India

Therese Carlström

Carolina Karlsson

Stockholm University, Sweden

*Corresponding reviewer

E-mail addresses: kumarkunalkamal@gmail.com (K.K. Kumar)

therese.carlstrom@hotmail.se (T. Carlström)

carolina-ani@hotmail.com (C. Karlsson)

You might also like

- Competition in World Politics: Knowledge, Strategies and InstitutionsFrom EverandCompetition in World Politics: Knowledge, Strategies and InstitutionsDaniela RussNo ratings yet

- Book Reviews: Competition, Competitive Advantage and Clusters: The Ideas of Michael PorterDocument8 pagesBook Reviews: Competition, Competitive Advantage and Clusters: The Ideas of Michael PorterPetarRadovicNo ratings yet

- Negotiation: The Chinese Style: Tony FangDocument11 pagesNegotiation: The Chinese Style: Tony FangnigerboyNo ratings yet

- Fang 2006 Negotiation The Chinese StyleDocument11 pagesFang 2006 Negotiation The Chinese StylechogomezNo ratings yet

- Negotiation The Chinese StyleDocument38 pagesNegotiation The Chinese Stylealex metal100% (1)

- International Relations Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesInternational Relations Literature Reviewc5rc7ppr100% (1)

- Individual Responses To Competing Institutional Log 2021 International BusinDocument14 pagesIndividual Responses To Competing Institutional Log 2021 International BusinNur Alia ElkaNo ratings yet

- Palgrave Macmillan Journals Journal of International Business StudiesDocument20 pagesPalgrave Macmillan Journals Journal of International Business StudiesCarlos SeguraNo ratings yet

- ECON 871 - Advanced International EconomicsDocument11 pagesECON 871 - Advanced International EconomicsTanmoy Pal ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Multinational Enterprises and Economic Nationalism: A Strategic Analysis of CultureDocument48 pagesMultinational Enterprises and Economic Nationalism: A Strategic Analysis of CultureBenedict E. DeDominicisNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0019850110001732 MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S0019850110001732 MainanastasyalouisNo ratings yet

- What Is International Management? A Critical Analysis Stream 3: Critical Perspectives On International BusinessDocument14 pagesWhat Is International Management? A Critical Analysis Stream 3: Critical Perspectives On International Businessmaheshnegi07No ratings yet

- Book Reviews: Ing Contemporary Social Change. London: Zed Books, 2006. 243 PPDocument20 pagesBook Reviews: Ing Contemporary Social Change. London: Zed Books, 2006. 243 PPMayank AgarwalNo ratings yet

- 2 Zien Guo FINAL 30052019Document27 pages2 Zien Guo FINAL 30052019jessamine.jizhinanNo ratings yet

- Sir. Kashir Asghar Tanveer Abbas: Assignment #1Document5 pagesSir. Kashir Asghar Tanveer Abbas: Assignment #1ztgaffNo ratings yet

- John Dunning - Multinational Enterprises and The Global EconomyDocument4 pagesJohn Dunning - Multinational Enterprises and The Global Economyminae4466No ratings yet

- Comparative and CrossDocument7 pagesComparative and CrossRavikumar0972No ratings yet

- Gindis2020 JOIE SymposiumCorporations EditorialDocument19 pagesGindis2020 JOIE SymposiumCorporations EditorialSaint ChristarNo ratings yet

- Oka Kusimba 2008Document58 pagesOka Kusimba 2008Carlos González LeónNo ratings yet

- 04 기획2Document30 pages04 기획2Biyas DattaNo ratings yet

- Discourse in Late Modernity - Rethinking Critical DiscourseDocument19 pagesDiscourse in Late Modernity - Rethinking Critical Discoursewaldenia.educacaoNo ratings yet

- The Becoming of Sarah Raymundo's The Symptom Called MarketisationDocument8 pagesThe Becoming of Sarah Raymundo's The Symptom Called MarketisationCharlotte HernandezNo ratings yet

- The NeighbourhoodDocument5 pagesThe NeighbourhoodDaniela Paz Piña BenítezNo ratings yet

- Brett, J.M., y Okumura, T. (1998) - Inter and Intracultural Negotiation US and Japanese Negotiators. Academy of Management Journal, 41 (5), 495-510.Document18 pagesBrett, J.M., y Okumura, T. (1998) - Inter and Intracultural Negotiation US and Japanese Negotiators. Academy of Management Journal, 41 (5), 495-510.pirrotpeNo ratings yet

- Grupo 02 - Collaboration 01Document16 pagesGrupo 02 - Collaboration 01Densel CastillónNo ratings yet

- Porter's Diamond ModelDocument26 pagesPorter's Diamond ModelMansi Srivastava0% (2)

- Kyosei - An Example of Cultural Keyword: Argumentatively Exploited in Corporate Reporting DiscourseDocument21 pagesKyosei - An Example of Cultural Keyword: Argumentatively Exploited in Corporate Reporting Discoursefausto CalderonNo ratings yet

- When Is A Publishing Business Truly Global'? An Analysis of A Routledge Case Study With Reference To Ohmae's Theory of GlobalizationDocument22 pagesWhen Is A Publishing Business Truly Global'? An Analysis of A Routledge Case Study With Reference To Ohmae's Theory of Globalizationjordon lauNo ratings yet

- How India Sees The World: Kautilya To The 21st Century,: by Shyam Saran, New Delhi: Juggernaut, 2017, Pp. 312, Rs 599Document6 pagesHow India Sees The World: Kautilya To The 21st Century,: by Shyam Saran, New Delhi: Juggernaut, 2017, Pp. 312, Rs 599Haseeb UddinNo ratings yet

- Critical Discourse AnalysisDocument19 pagesCritical Discourse AnalysisMurtuza MuftiNo ratings yet

- International Business Environment Article List - FinalversionDocument6 pagesInternational Business Environment Article List - FinalversiontesfaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Regional IntegrationDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On Regional Integrationc5m07hh9100% (1)

- Accounting For Meaning: On 22 of David Foster Wallace's The Pale KingDocument11 pagesAccounting For Meaning: On 22 of David Foster Wallace's The Pale KingÁlex CadavidNo ratings yet

- 64 - M.A. in PoliticsDocument2 pages64 - M.A. in PoliticsЅамаяNo ratings yet

- Censorship in South Asia Cultural RegulaDocument10 pagesCensorship in South Asia Cultural RegulaNAVNEET PRATAVNo ratings yet

- Dwi Yudistira Suhendra (A Critical Discourse Analysis of Three Speeches of King Abdullah II)Document16 pagesDwi Yudistira Suhendra (A Critical Discourse Analysis of Three Speeches of King Abdullah II)DWI YUDISTIRA SUHENDRANo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Ims6365.501 06f Taught by Habte Woldu (Wolduh)Document11 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Ims6365.501 06f Taught by Habte Woldu (Wolduh)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- Fang 2006 Negotiation The Chinese StyleDocument12 pagesFang 2006 Negotiation The Chinese StyleNgocQuyen123No ratings yet

- Fang China NegotiatingDocument11 pagesFang China NegotiatingdmsdsNo ratings yet

- Essay On Qualities of A Good LeaderDocument7 pagesEssay On Qualities of A Good Leadereikmujnbf100% (2)

- Critical Discourse Analysis. Mirzaee HamidiDocument11 pagesCritical Discourse Analysis. Mirzaee HamidiAsma KhanNo ratings yet

- 5 Noorian and BiriaDocument16 pages5 Noorian and BiriaSawsan AlsaaidiNo ratings yet

- Accounting For Meaning The Pale KingDocument11 pagesAccounting For Meaning The Pale KingÁlex CadavidNo ratings yet

- Chương 1-2-3Document55 pagesChương 1-2-3Nhi Trương Trần BảoNo ratings yet

- 90 Paper2 With Cover Page v2Document25 pages90 Paper2 With Cover Page v2Chika JessicaNo ratings yet

- 2.2 Mats Forsgren Theories of The Multinational Firm pg.1-30 PDFDocument30 pages2.2 Mats Forsgren Theories of The Multinational Firm pg.1-30 PDFRicardoAndresBalcazarGiraldo100% (1)

- Critical Discourse Analysis: Jaffer SheyholislamiDocument15 pagesCritical Discourse Analysis: Jaffer SheyholislamiivanbuljanNo ratings yet

- The Emergence of A Knowledge-Based View of Clusters and Its Implications For Cluster GovernanceDocument16 pagesThe Emergence of A Knowledge-Based View of Clusters and Its Implications For Cluster GovernanceHasan AnwarNo ratings yet

- Book Review: of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. Random House, New YorkDocument9 pagesBook Review: of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. Random House, New Yorkesila dilik fanNo ratings yet

- Essays On Social IssuesDocument9 pagesEssays On Social Issuesafibkyielxfbab100% (2)

- JLTR, 22Document7 pagesJLTR, 22Nicole HernandezNo ratings yet

- Sem 12 Economics - of - Hybrids JITE 2004Document32 pagesSem 12 Economics - of - Hybrids JITE 2004Edna PossebonNo ratings yet

- Framework For Sustainable Security (New Delhi, Manohar and Colombo: RegionalDocument3 pagesFramework For Sustainable Security (New Delhi, Manohar and Colombo: RegionalSatriaCoolNo ratings yet

- India The Rise of Asian GiantDocument4 pagesIndia The Rise of Asian Giantabose06No ratings yet

- Søderberg - Narrative Interviewing and Narrative AnalysisDocument20 pagesSøderberg - Narrative Interviewing and Narrative AnalysisCătălin C. KádárNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document23 pagesChapter 2JERE-ANN MANAMBAYNo ratings yet

- The Price of Prestige: Conspicuous Consumption in International RelationsFrom EverandThe Price of Prestige: Conspicuous Consumption in International RelationsNo ratings yet

- Document Raj: Writing and Scribes in Early Colonial South IndiaFrom EverandDocument Raj: Writing and Scribes in Early Colonial South IndiaNo ratings yet

- An Introduction to U.S. Collective Bargaining and Labor RelationsFrom EverandAn Introduction to U.S. Collective Bargaining and Labor RelationsNo ratings yet

- Definition of Managerial EconomicsDocument1 pageDefinition of Managerial Economicsmukul1234No ratings yet

- Study On The Dynamics of Shifting Cultivation Areas in East Garo HillsDocument9 pagesStudy On The Dynamics of Shifting Cultivation Areas in East Garo Hillssiljrang mcfaddenNo ratings yet

- PERRUCI Millennials and Globalization 2012 PDFDocument6 pagesPERRUCI Millennials and Globalization 2012 PDFgomiuxNo ratings yet

- Paper 3 of JAIIB Is Legal and Regulatory Aspects of BankingDocument3 pagesPaper 3 of JAIIB Is Legal and Regulatory Aspects of BankingDhiraj PatreNo ratings yet

- IpolDocument3 pagesIpolamelNo ratings yet

- Jason White Resume 2019 v2Document1 pageJason White Resume 2019 v2api-355115412No ratings yet

- Porter 5 Force FinalDocument35 pagesPorter 5 Force FinalAbinash BiswalNo ratings yet

- 1 Priciples of Engineering EconomyDocument32 pages1 Priciples of Engineering EconomyMaricar AlgabreNo ratings yet

- From Resistance To Renewal: A 12 Step Program For The California Economy by Manuel Pastor and Chris BennerDocument118 pagesFrom Resistance To Renewal: A 12 Step Program For The California Economy by Manuel Pastor and Chris BennerProgram for Environmental And Regional Equity / Center for the Study of Immigrant IntegrationNo ratings yet

- Tax AssignmentDocument5 pagesTax AssignmentdevNo ratings yet

- Invitation To Bid: Dvertisement ArticularsDocument2 pagesInvitation To Bid: Dvertisement ArticularsBDO3 3J SolutionsNo ratings yet

- Worldwide Service Network: Middle EastDocument3 pagesWorldwide Service Network: Middle EastRavi ShankarNo ratings yet

- Paris Climate Agreement SummaryDocument3 pagesParis Climate Agreement SummaryDorian Grey100% (1)

- TAC0002 Bank Statements SelfEmployed ReportDocument78 pagesTAC0002 Bank Statements SelfEmployed ReportViren GalaNo ratings yet

- Accounting EquationDocument2 pagesAccounting Equationmeenagoyal9956No ratings yet

- Export Invoice: Item Description: Qty: UOM: Curr Unit PriceDocument4 pagesExport Invoice: Item Description: Qty: UOM: Curr Unit PriceAdam GreenNo ratings yet

- EV Infrastructure Solutions DEA-524Document8 pagesEV Infrastructure Solutions DEA-524tommyctechNo ratings yet

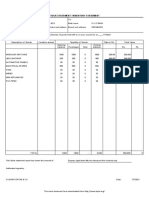

- Stock Statement Format For Bank LoanDocument1 pageStock Statement Format For Bank Loanpsycho Neha40% (5)

- Kanlaon Vs NLRCDocument3 pagesKanlaon Vs NLRCJade Belen Zaragoza0% (2)

- Doku - Pub - Insight-Intermediate-Sbpdf (Dragged)Document7 pagesDoku - Pub - Insight-Intermediate-Sbpdf (Dragged)henry johnsonNo ratings yet

- Steeple AnalysisDocument2 pagesSteeple AnalysisSamrahNo ratings yet

- List of Turkish CompaniesDocument5 pagesList of Turkish CompaniesMary GarciaNo ratings yet

- Firth, Raymond (Ed.) (1964) Capital, Savings and Credit in Peasant Societies (Só o Índice!)Document2 pagesFirth, Raymond (Ed.) (1964) Capital, Savings and Credit in Peasant Societies (Só o Índice!)Felipe SilvaNo ratings yet

- Bloomberg Country CodesDocument3 pagesBloomberg Country CodesPaulo RobillotiNo ratings yet

- Buyer Questionnaire: General QuestionsDocument3 pagesBuyer Questionnaire: General Questionsshweta meshramNo ratings yet

- Bank Guarantee BrochureDocument46 pagesBank Guarantee BrochureVictoria Adhitya0% (1)

- Cola Wars PresentationDocument13 pagesCola Wars PresentationkvnikhilreddyNo ratings yet

- Iran Letter JCPOA Compliance 090617Document1 pageIran Letter JCPOA Compliance 090617The Iran ProjectNo ratings yet

- Downtown Design ExhibitorsDocument21 pagesDowntown Design ExhibitorsIan DañgananNo ratings yet

- Eco-Fashion, Sustainability, and Social Responsibility: Survey ReportDocument16 pagesEco-Fashion, Sustainability, and Social Responsibility: Survey ReportNovemberlady09No ratings yet